Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Ross Stretton

photo Jim McFarlane

Ross Stretton

What can a national ballet company be? It hardly seems fruitful to argue whether one should exist, one does and is not likely to be disbanded barring a violent revolution in culture and government. So, given that a lion’s share of resources for dance is poured into a national ballet company, it is very good news that ours is being directed by Ross Stretton.

In fact, after our conversation in July, I am convinced that the Australian Ballet could be on the verge of becoming something great. Ross Stretton strikes me as a sort of a Clark Kent of kinetic intelligence. It remains to be seen whether he will evolve into a dance super hero, but his mild manners are working just fine at the moment for gently introducing some pretty radical ideas, methods and works.

Stretton is serious and thoughtful on the subjects of great choreographers, great dancers and great dance. And he has specific plans for creating them, as well as for opening up the AB’s resources to dance as a whole and cutting down on the cross-aesthetic bashing which seems to be the basic mode of discourse in dance in Australia.

With the aim of creating great things, the AB seems to be developing a special relationship with Twyla Tharp. Stretton has just sent six dancers over to New York to workshop a piece with her and to soak up her intelligence and input. One has to wonder here about the possibilities which might have been exploited in this relationship had the new Kennett Dance Company come under the aegis of the Australian Ballet. The dance community seems relieved that the company went to an artist rather than an administrator, but Stretton is both and his interest in running such an enterprise represents radical new thinking about the Australian Ballet in the wider context of dance in Australia.

Ross Stretton’s aesthetics and ideas were shaped by his kinetic experiences with choreographers like Twyla Tharp whom he worked with closely as dancer and administrator in New York and continues to work closely with now. He says about Tharp and about Glen Tetley, the other seminal influence he cites, that they share the quality of intelligence. “Great choreographers”, Stretton insists, “are intelligent choreographers”. Intelligence manifests itself in their ability to “explain the final result” before a work is finished. “Clear understanding of what he was doing” comes first in Stretton’s description of what it was about Glen Tetley which affected him so strongly. This was followed by “the power and intelligence behind him” and “a skill for choreography, not just thoughts he put out in the studio, but an understanding of where it was going and an ability to articulate it”. This is both a physical and verbal ability to articulate; Stretton says it was what Tetley or Tharp or a handful of others did as well as what they said which impacted on him.

Ross Stretton danced in the American Ballet Theatre in the 1980s when Baryshnikov was running the company and expanding its reach and repertory to take in works by Mark Morris, Twyla Tharp and others. This was radical at the time, but is now being taken up by ballet companies around the world. However, when Stretton and Baryshnikov were doing it, they were not picking up works from a menu, they were having them created on their bodies. Stretton, in fact, bristles a bit when I bring up the subject of the shopping list company which gets one ‘greatest hit’ from each of today’s biggest dance hit-makers. He’s obviously been accused of taking this approach, and it’s not what he has in mind at all. He recognises that dancers will grow most from their direct contact with choreographers, not from having works set on them by assistants (and the same goes for audiences). “My love is for creating new work. I want works made on my dancers, by Australians and by internationals”.

So Stretton’s New York experience is about to have a big impact on Australian ballet. But it is not a one-way street. Stretton believes that being Australian made a difference in his meteoric rise to a position of artistic influence at the American Ballet Theatre. He made an “instant transition from dancer to administrator” there, when Jane Herrman (then General Manager) asked him to run her artistic department after Baryshnikov left.

What was it she saw in him, to elevate him so rapidly? “Someone who understood the choreographic process and as a dancer had helped choreographers create their work. Someone who knew all of the dancers but didn’t have any grudges, vendettas, axes to grind or personal problems with people.” (I note a plethora of descriptive words breaking forth from a usually understated use of language. There must have been a lot of opportunities to develop this vocabulary at ABT.) Jane Herrman invested in Stretton “somewhat with an element of trust”, but, he says “she saw I knew and believed in dance”.

And, Stretton says, being Australian was part of it. It “helped him keep a distance on the backbiting” for one thing. But he also knows that Australian dancers are good. “They are adaptable, eager to please, talented, and non-threatening. No-one ever thought of me as someone who might do what I did—move from dancer to administrator, no-one was ever threatened by me”. So, the mild-mannered Clark Kent makes his first strike as Executive Apollo, bringing to the job the full force of a seasoned dancer’s creative ability to make the choreographic process flow and help choreographers realise their vision.

Ross Stretton believes that this is a most important ability in his new job, and thinks he got it from working with great artists. At ABT he had “the greatest” coming through his office—designers, choreographers, composers. He misses that and wants to create it here, “to create those collaborations of the greatest”.

His relationship to these artists and their creations is active. He understands that choreographers need help. “They can’t always just come up with the goods. They need understanding and someone to turn to, not just to be put in a studio and left to flounder—they may have a block, or may need to talk through their work. As a producer I may not know that unless I am working with them on developing the project”.

He says that development is about more than just giving choreographers space and dancers. “Choreographers are always on the output”. He is hosting a workshop right now to give them input. “A week of talking and listening about how concepts of dance can be combined with elements of design and lights. A think tank.”

Stretton believes design is one of the big things that is changing in ballet—“Scenery and costumes have changed, space can be carved out by light, there is more room to dance onstage”. This workshop which is focussed absolutely on process, not product, will be a week of discussion, moderated by Dr Michelle Potter, between three choreographers, three lighting designers and three set/costume designers.

Ross Stretton sees it as part of his job to reap the “seeds that have been planted to make great Australian choreographers. They need input, not just space, but guidance from people who understand how to choreograph. Someone to cut the earth from under them and make them understand the form.”

Lest I whip him into the nearest phone booth before he’s ready to unmask Clark Kent as a radical force, he is quick to add, “I want newness, but I’m not getting rid of the past”. He will keep up a relationship with the traditional classical repertory. For one thing, it is part of his job to keep the company afloat. But for another thing, he really believes in the “classics” (which are actually mostly “romantics”—ie Swan Lake, Giselle etc) for their expressive possibilities. As he said in his Green Mill keynote address, “Sometimes in the middle of a performance I would be overwhelmed by a total sense of identification with the character I was dancing—my dance and the dance became one. It always left me completely stunned, in awe of the power of dance”.

Great dance, he says, “is from the body”, it’s what he’s drawn by, what he loves. “It is when 14 dancers go to another place—it’s what happened last night in In The Upper Room—14 dancers were transported onstage by what they were doing, giving them such pleasure. The dancers’ pleasure is what the audience feels—twice as much. The audience’s pleasure in dance lies in that excitement, that purity, which can be in any kind of work.”

Ross Stretton is motivated and informed by his kinetic experience, his notion of intelligence springs from that source, as does his administrative instinct. In putting together a program he says he “is guided by music” almost, I think, in the way that a dancer’s performance in a ballet would be. And he thinks that it is fair enough for a dancer’s art to move a choreographer. He believes that the choreographic process works best “when a choreographer finds in a dancer a muse, rather than trying to impose their personal dance on a dancer. If a move is well co-ordinated a good choreographer goes with it, draws it out and develops it”. In other words, the best in a dancer will bring out the best in a choreographer.

And Ross Stretton is dancing well now, in his role as Executive Apollo. His co-ordination of a program by Twyla Tharp, Stephen Baynes, and Stephen Page (choreographing Rite of Spring at Stretton’s suggestion, using Bangarra and AB dancers) is an activitist piece of lateral thinking about history and contemporaneity, culture and dance. It could, if it reaches its promise, also be an outstanding example of Apollonian intelligence in dance.

RealTime issue #20 Aug-Sept 1997 pg. 39

© Karen Pearlman; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Leigh Warren and Dancers in Shimmer

photo Grant Nowell

Leigh Warren and Dancers in Shimmer

Quiver, the new program from Leigh Warren and Dancers is continuing evidence of the company’s invention and excellence. With last year’s return season of Klinghoffer and now, the unveiling of two contrasting works, Shimmer and Swerve, Leigh Warren’s signatures are becomingly increasingly apparent. His work is disciplined, elegant and has the added intensity which music performed live can bring. With Klinghoffer, he borrowed ethereal choruses from John Adams’ opera, performed on stage by a score of Corinthian Singers. For Shimmer he has used the sparkling playing of the Australian String Quartet and in Swerve, the frenetic rhythms of cabaret favourites Pablo Percusso.

Under the scrutiny of Robert Hughes, film-maker Ken Burns and others, the Shaker movement has received renewed attention for its minimalist ingenuity, its diligence and apparently serene other-worldliness. No longer intact—unsurprisingly after ten generations of planned celibacy—the most enduring legacies of the once-thriving and financially successful Shaker communities are their quilts and collectable chairs. And, of course, their eloquent witness to the radiance of belief.

Composer Graham Koehne’s String Quartet No.2 “Shaker Dances”, celebrating the pastoral virtues of this gentle, quietist sect, provides the score for Shimmer. The performers, dancers and musicians, assemble silently on stage, their backs to their audience in frozen tableau. Then, successively, the members of the Australian String Quartet separate from the group, take up their seats downstage prompt-side and begin tuning up. Scraps of tunes can be heard, including a few bars of what sounds like Simple Gifts, the religious folk tune used as central motif in Aaron Copland’s Appalachan Spring. The cello joins, then the others, as the six dancers begin their demurely exquisite movement.

Leigh Warren’s splendidly assured choreography uses the dancers in pairs and gendered threes. There are echoes of square dance tropes as they form parallel lines and dance in profile, moving enticingly close but retaining modest distance. Top lit by Geoff Cobham the dancers move under vertical spots that seem at any time to raise them in some sort of beam-me-up rapture. The effect—enveloped in the warm, vibrant playing of the quartet—is fluid and unaccountably affecting.

Central to the success are Mary Moore’s costumes—silky, iron grey frock smocks with yellow-gold linings which button to the navel and then flow across and away from the body with notably erotic ambiguity. Powerfully dramatising the tensions of religious ecstacy, the costumes carry both male and female signification, puritan concealment and then—unbuttoned over the dancers’ flesh-toned body stockings—unexpected sexual abandon.

The movement parallels these dualities. The dancers, in diagonal formation, work in repetitive hoeing and chopping movements, or, hands prayerfully clasped, rotate their elbows in undulating rhythm. Elsewhere, when they raise their arms full stretch, roll along the floor leg over leg, or dance in balletic pairs, they achieve a contrasting sensuality—enhanced by Cobham’s buttery lighting, the throaty repetitions of cellist Janis Laurs and Elinor Lea’s fluttery pizzicato.

Shimmer is a fine work and must rank among Warren’s most accomplished. Carefully conceived, intelligently designed and beautifully performed with solos from Kim Hales-McCarthur and duets from Csaba Buday and Rachel Jenson, it uses Koehne’s appealing composition to good effect. This production is beautifully framed from the opening fugue to the final restatement of the musical theme, and then the curtain image of dancers and musicians gathered midstage as top spots fade to a beckoning side light. Shimmer exploits the conflicts of introspection and worldliness, of piety and a kind of pleasure, which may be secret but never guilty.

By contrast Swerve is a metal-rattling, taiko drumming display of athleticism and grunge style. From behind the curtain we hear the sounds of heavy spinning chrome plates wobbling into silence. Then as the curtain lifts we see Ben Green, Josh Green and Greg Andresen, aka Pablo Percusso, strapping on a variety of hubcaps from Kingswood to Nissan Bluebird and tapdogging up a storm.

The dancers, in skateboard baggies, black vinyl hot pants, leather and leopard skin, enter browsing newspapers as they nonchalantly stack themselves on one another. As the band take up drum kits at the back of the stage the dancers begin to slap each other with the papers setting up repetitions and syncopations. It is reminiscent of Stomp, Luke Cresswell’s kitchen cupboard of found-sound, but Swerve has plenty of its own zing as well.

Lit low from the side of the stage and then washed in heavy scarlets and torquoise, the dancers meld with the rhythms. An angular, exuberant solo from Delia Silvan is followed by a trio of rapping garbage bins then another burst from Rachel Jenson and some breakdance variants from Peter Sheedy and John Leathart.

The “auto”-erotic motifs continue from hubcabs to tyres to traffic as Pablo Percusso take up drumming stations in tilted-back car seats while the dancers let rip in a blaze of foot and sidelights.

Swerve moves into high gear for the fourth section, Head On, with thunderous drumming, spliced-in highway screeching and choreography ready to crash through to Cronenberg.

Leigh Warren and Dancers have compiled a program both meditative and high octane. For many the sustained energy of Swerve is the high point. However, for all its technique, it is more fizz than substance. But those Shakers doing their shimmer…? Well, that’s a road much less travelled.

Quiver Leigh Warren and Dancers, Norwood Town Hall, Adelaide, June 20-28

RealTime issue #20 Aug-Sept 1997 pg. 40

© Murray Bramwell; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Co-operative Multimedia Centres (CMCs) emerged into the atmosphere at about the same time as the Cfcs were destroying it. The atmosphere surrounding the newly identified ‘clever country’ at the time contained the heady technology of ‘new media’ and all things digital—interactive multimedia, the internet and the world wide web. Australia, in the view of the Labor government, had been at the end of the communication line for long enough and needed to be aboard the band-wagon that would deliver global proximity, as well as a new employee hungry industry.

The intervention that Keating and Canberra wanted to make was announced in Creative Nation, that policy document which spoke in October 1994 of “being distinctly Australian” in the face of the “assault from homogenised international mass culture”. After the inevitable wrangling, the six Centres that had been proposed were open by mid-1996. What impact have they had? What has been the quality of the services provided? What plans do they have to survive a non-interventionist, market-place government?

The mission for the Centres was to “offer education, training and professional services, access to state-of-the-art equipment and facilities, access to leading-edge research and development, and assistance with the handling of issues such as intellectual property and product testing and evaluation”. To greater or lesser degree each of the locations have and are delivering in each of these areas, but with differing degrees of emphasis—“complementarity” was the word used by Professor Guy Petherbridge, CEO for Starlit CMC and spokesperson for the Association of CMCs, to describe how the strengths of each enterprise are shared between all. It seems that it is early days for such an ideal to become evident, like many of the projects listed by each CMC.

Web sites are an obvious point of contact with the Cooperatives, some of which are non-profit, and the QANTM site (www.qantm.com.au) explains in the clearest way their business model summarised as the “brokerage of skills and related services for the interactive multimedia industry”.

QANTM is now operational in Darwin and Brisbane with 20 staff employed in four areas: Youthworks has trained over 200 young people in basic internet skills. Indigenet has developed approximately 15 major projects and with the leadership of Chris ‘Bandirra’ Lee will achieve placing digital networks parallel to traditional ones. Eventually, some access to Indigenous culture will be given to the wider global community. Australian Silicon Studio Training Centre (ASSTC) has received over 200 scholarship applications for 3D animation scholarships and the first 10 students have completed. QANTM Edge has five major development projects in the multimedia arena, all staffed by local contractors or individuals. CEO Olaf Moon admits that “research and development is a minor part of our activities, apart from research into five copyright projects”. Queensland government sponsorship is for two years and the Federal Governments will continue for a total of three. “At the end of this time, we expect to be self sufficient”.

QANTM is one of two Queensland CMCs. Starlit (www.starlit.com.au – expired) focuses on the tooling needs of educationalists and trainers, and instructional design, utilising the accumulated national experience of ‘distance learning’. In a bid to challenge the US heavies of on-line courses, the new academic year will see Swinburne University launch 56 courses, Griffith Uni just behind, all distilled from Australia’s unique pedagogical expertise.

“Western Australia is now poised to become a Mecca for digital artists throughout the Asia Pacific”. The team at Imago in Perth (www.imago.com.au – expired) identify their work with the art and cultural sector as their main achievement. One project with the Film and Television Institute established during July is DAS (The Imago/FTI Digital Arts Studio), a facility specifically designed to allow access for screen culture artists to modern digital production facilities. With financial and technical support from Arts WA, the Australian Film Commission and the Australia Council, the production facilities include interactive multimedia, digital sound, 3D modelling and animation, digital video and web authoring. The essential and primary purpose of DAS is to provide a facility where artists can access computer equipment for experimentation, production and training, and become a hub for critical arts activity.

CEO Mike Grant observes that “at this early stage there has not been a lot of cross-over between the technological researchers and artists”. Another facility, the Imago Sun Research Centre, is also open and equipped with high-end workstations. “A number of leading local artists are already designing projects to work on utilising the resources and expertise of the centre”, says Grant. Imago also works with PICA in the implementation of a bi-annual funding program which provides small amounts of money to artists for research and development. In addition Imago covers programs addressing education and training, industry development, content development, and research coordination.

Ngapartji (www.ngapartji.com.au – expired) launched onto coffee saturated Rundle Street, Adelaide in August 1996 with a state of the art multimedia centre containing studios, seminar and exhibition spaces, and a spectacular pavement cafe—up to a 1000 people every week have a hands-on experience with interactive multimedia, predominantly on-line. Training is either informal from trusty cafe staff or from high level trainers.

Carolyn Guerin, Ngapardji’s manager of applied research explains that the centre assists with “a range of on-line activities with real life elements such as the Virtual Writers in Residence Pilot Project (funded with the Australia Council), and Ngapartji Interactivity and Narrative Research Group (“Rosebud”) which, besides holding monthly seminars, has a web site with papers consolidating the group’s work and, soon, a research database. We have also sponsored and promoted the work of artists including Linda Marie Walker—exposure to new work is key to the centre. With so many mainstream industry people participating in activities at the centre, exposure to art-based work is inspiring and often commented on—the last Australian Multimedia Enterprises board meeting was held here during Jon Mccormack’s Turbulence exhibition. Most of the board members were blown away by it—you could see their minds ticking over like mad”.

Ngapartji Nodes will bring other Adelaide organisations on-line—Tandanya Aboriginal Centre is the first—self-managing the kind of computers available in the Ngapartji cafe. Nodes is about on-line activity and has included virtual community components—interactive communications capabilities rather than your usual brochure ware.

In Sydney, Access Australia (www.cmcaccess.com.au – expired) and its unwieldy consortium including Telstra, NSW Department of School Education, NSW TAFE Commission and five metropolitan and regional universities, have just appointed its third CEO in two years, Rim Keris, who comes from a hardware marketing and business background. He will need to bring substance to a program which includes Propagate, a key national project allied with the European Commission, on multimedia copyright.

At the other end of the financial scale also in Sydney, MetroTV (www.home. aone.net.au/metro/-expired now Metro Screen http://metroscreen.org.au/ Eds.) launched Stage One of a New Media Laboratory in November 1996 then last month received State Government funding to set up Stage Two—this includes ten high-end Apple Macintosh 9600 computers on an ethernet network with high speed internet access. Since January, in conjunction with other screen culture organisations, a range of digital courses have been run at Metro.

In Melbourne, it is the screen culture sector again setting the pace in giving access to digital media facilities. With financial backing from the state-run Multimedia Victoria, Open Channel (www.openchannel.org.au) will augment its digital video editing facilities with four 3D animation suites and a dozen high-end PowerMacs.

In the smart end of town, eMerge (www.emerge.edu.au – expired) is about to pilot a project with cultural institutions and individual artists to establish a Virtual Cultural Centre, “a complete experience rather than a collection, going live in 1998”, according to CEO Terese van Maanen—surely an opportunity for vibrant links with Melbourne talent? On the web, the iSite resource directory for the national industry will list personnel and clients. A range of other projects will address pedagogical and curriculum concerns at all three educational levels. Links with San Francisco and the ‘Malaysian corridor’ are also advanced.

Many, including Colin Mercer at the Griffith Key Centre for Cultural and Media Policy, wonder about the marginalisation that the more creative communities are being forced into by the majority CMCs pursuing industry and training objectives. “Interactive multimedia offers a chance to break down a whole series of barriers between genres, disciplines and artforms. Convergence of mind-sets, not just technologies, is the issue,” according to Mercer, “with the ability to think laterally and more creatively”.

Professor Petherbridge feels that it is the industry support area rather than the cultural area that will continue subsidy to the nascent multimedia industry, “because it provides a message to industry and the public at large that this is a very important part of public policy…that if we slip in the next year, we’ve really slipped”.

RealTime issue #20 Aug-Sept 1997 pg. 26

© Mike Leggett; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

“What a strange, demented feeling it gives me when I realize I have spent whole days before this inkstone, with nothing better to do, jotting down at random whatever nonsensical thoughts have entered my head.”

Yoshida Kenko c1330

While no-one can claim immunity from nonsensical thoughts—some can be charming and witty, like those of the Buddhist monk Kenko—others are merely stupid. One would be hard pressed to find a better example of wilful stupidity than our government’s recent announcement of “principles for a national approach to regulate the content of online services such as the internet”.

A joint press release from the Minister for Communications and the Arts, Senator Richard Alston, and Attorney-General, Daryl Williams, proposes a “framework [that] balances the need to address community concerns in relation to content with the need to ensure that regulation does not inhibit industry growth and potential”. This ludicrous proposal, which can only have been dreamed up by people who have never had any contact with the internet, envisages that the online service provider (ISP) industry will “develop codes of practice in relation to online content, in consultation with the Australian Broadcasting Authority (ABA)”.

As a result, anyone unhappy about online content must first complain to the relevant ISP; the ABA then has the authority to investigate unresolved complaints. Conceptually, it is similar to the way in which film, television, radio broadcasts and computer games are currently regulated. A distressed viewer might call a television station to complain about nudity or language in a movie. If they do not receive a satisfactory response (whatever that might mean) from the television station, they can then complain to the ABA which conducts an “inquiry” and, if it finds the material was inappropriate, tells the broadcaster not to do it again. Prosecutions are exceedingly rare.

The system works tolerably well because there is tangible evidence of any “offending material” in the form of reels of film or videotape, audiotapes of radio broadcasts, and floppy disk or CD-ROM games and, because potentially objectionable content has already been filtered out by the censorship system. In the case of the internet, this process can already be effectively mimicked by filtering and parental control software such as CYBERsitter, SurfWatch, Net Nanny, Rated-PG, X-Stop, Cyber Snoop, and Cyber Patrol—just a few of the alternatives which render internet regulation unnecessary, as long as parents are prepared to accept responsibility for limiting their children’s access to the net.

But let’s assume, adopting the position of the fundamentalist Right, that these software safeguards are only partly effective and that “harmful” material slips through. Only a tiny fraction of internet content is stored on local (ie Australian) servers. What can the ABA do about a complaint concerning “offensive” content on a web server in the US, or Italy, or Japan? What kind of response is the offended web surfer likely to get from a foreign content producer or ISP? Incredulity? Derision?

And so much of the content is ephemeral anyway: chat sessions exist only in real time, web sites appear and disappear, e-mail and Usenet news is stored only temporarily on an ISP’s server. Internet content resembles, as much as anything, telephone conversations and facsimile transmissions. In a sense this is the core of the problem: the “regulatory framework” attempts to impose a broadcast metaphor on what are essentially telecommunications carriers. They may as well attempt to control the air Australians breathe or the water we drink.

The whole idea of regulation is so divorced from reality that it is difficult to explain why it is being proposed. Put to one side the government’s duplicity in not admitting that regulation is largely unnecessary; perhaps the legislation is a cynical attempt to appease Senator Brian Harradine, the Lyons Group and other conservative elements in the Liberal party, put forward in the knowledge that it is unworkable and will inevitably fail.

Alternatively, could it be that Australian politicians are profoundly unaware of digital culture and the way it is reshaping our world? That this lack of understanding is not restricted to federal politicians becomes depressingly obvious when you observe in NSW the Carr government’s tubthumping about internet pornography while they shovel computers into state schools and hook them up to the net without making any real provision for teacher training.

Ultimately, it is not this whacky censorship sideshow that is truly dispiriting. It is that at a time when we need to formulate an imaginative and courageous response to the radical social and economic transformation about to be wrought by the internet, our politicians are jockeying for position like amateurs at a provincial racetrack. Which horse do you bet on when the only starters are confusion, dishonesty, cynicism, stupidity and ignorance?

RealTime issue #20 Aug-Sept 1997 pg. 22

© Jonathon Delacour; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Catalogued, packaged and displayed, looking through glass at our history. Corridors of locked cabinets within which are stored a phantasmagoria of human inquiry; screens we dare not touch, through which we can only gaze. Down every corridor of this mighty building, on either side, butterflies of every imaginable colour; shells the size of emus; skulls of men, women and children who knew well the primal dark; skeletons of beasts of unimaginable proportions—all protected within controlled atmospheres where humidity measuring devices murmur quietly amidst the shuffling feet of visitors. A sarcophagus of speculation and intrigue down through which we wander, in awe, in dreams, inside the Museum.

For many of us, this was the kind of museum we grew up with, one where history was untouchable, but presented with a sense of showmanship. The museum was filled with drama: frozen battles, hunts and representations of historical moments stimulated the imagination much like a waxworks museum on steroids. But these are museums of the past. They may one day be on show themselves within a Museum of Museums, but such a place would no doubt be virtual, to be explored, perhaps more interactively, via another display case of sorts, the computer screen.

In Melbourne, we are losing the last remnant of our once magnificent Museum, its Planetarium. A few moments in the Planetarium, seated in one of its cozy chairs and you were transported into the heavens. No VR goggles, no 3D glasses. An early 1960s Japanese-made projector with multiple lenses, a domed ceiling for a screen and reclining seats was all it took. But it’s going, perhaps to be replaced by something akin to the infamous CAVE, a walk-through virtual environment driven by two powerful ONYX computers, a suite of video projectors and an armory of 3D glasses. Sounds great doesn’t it!

Visitors to the launch of the Ars Electronica Centre, Austria’s Museum of the Future, first saw the CAVE in September 1996. Ars Electronica is host not only to the CAVE, but is a screen-based display and interactive environment of research and inquiry. The Museum has grown out of the spectacle into an “intelligent environment”.

Ars Electronica describes itself as a “knowledge machine” with a mission to help visitors attain information “fitness”. A kind of mental gymnasium where science, art and business are seen to be working together in an “interdisciplinary interface between technology, culture and society”. More a museum of concepts, ideas and the commercial development of them. In fact, changing the notion of museum as historical archive to an open laboratory.

Keeping its foot literally in the new media door, Ars Electronica has founded and continues to host international forums from which it draws its conceptual framework. This year, from September 8–13, Ars Electronica mediates its annual festival and symposium. This year’s theme, titled “Fleshfactor: Informationsmaschine Mensche”, is the Mensch, the human being. Festival Directors Gerfried Stocker and Christine Schôpf are creating an investigative environment around their short, but potent, manifesto for Fleshfactor:

In light of the latest findings, developments and achievements in the fields of genetic engineering, neuro-science and networked intelligence, the conceptual complex now under investigation will include the status of the individual in networked artificial systems, the human body as the ultimate original, and the strategies for orientation and inter-relation of the diametric opposites, man and machine, in the reciprocal, necessary processes of adaption and assimilation.

Participants in Fleshfactor will include Donna Haraway, Neal Stephenson, Steve Mann and Stelarc. The net version of the symposium has been active for several months, consolidating the key issues and subject matter that will be explored throughout the duration of the festival.

Each year, in collaboration with the Upper Austrian Studio of Austrian Radio, Ars Electronica invites artists the world over to contribute new works to the Prix Ars Electronica. This year, four out of the 900 entries won a total of $135,000.

Many of us hold Ars Electronica in great esteem. It is a place where innovation, the edge of new media arts, has both a home and centre for research and discourse. That it is, but on the ground, it’s also a business and a very young communicator. It has created expectations of itself through its manifesto, its vision—much of which it is still learning to accommodate, let alone live up to. That said, Ars Electronica is most certainly of the ‘brave new world’. It displays both courage and a commitment to experimentation that we have yet to see in any equivalent institution in Australia. We have Scienceworks and its successful Cyberzone exhibit, but it is a long way from the technology and cultural incubator that is Ars Electronica.

Ars Electronica Centre, http://www.aec.at/

Ars Electronica Festival, http://www.aec.at/fleshfactor/

Prix Ars Electronica, http://prixars.orf.at/ [expired]

RealTime issue #20 Aug-Sept 1997 pg. 27

© Andrew Gaynor; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

e-media, a new gallery space dedicated to the display of computer-based art, kicked off in June with the presentation of Bronwyn Coupe’s interactive CD-ROM The Inside of Houses. A thoughtful and whimsical work, The Inside of Houses offers the user a guided tour through the memories of the author’s family. Each family member was asked to contribute their recollection of the floor-plan of a house inhabited by the family years before. The user is invited to navigate their way through each floor-plan, drawing out hidden sounds and video footage in the process. The vast difference in the floor plans produced by each member—and the sounds and images they invoke—is then used as a device to prompt the user into contemplating the way in which, to use Coupe’s words, “notions of size, distance, direction and connection are influenced by each person’s personal mythology”.

The work cleverly draws attention to both the computer’s status as a memory machine and its ability to archive and cross-reference. It does claim to allow the audience their chance to add to the work with drawings and stories about a place they have lived in, but I wasn’t able to get it to do this. That aside, The Inside of Houses runs well and provides the user with an enjoyable experience.

An initiative of the Centre for Contemporary Photography and Experimenta, e-media is a welcome addition to the electronic art scene. Look out for future programs featuring Sally Pryor’s Postcard from Tunis and Megan Heywood’s I am a Singer.

e-media is open Wednesday to Friday 11-5 and Saturday 2-5 at the Centre for Contemporary Photography, 205 Johnston Street, Fitzroy 3065

RealTime issue #20 Aug-Sept 1997 pg. 28

© Lisa Gye; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

High and low tech, static and dynamic, permanent and transient, eMedia 97 embraced a paradigm of multimedia as the fusion of diverse artistic practices with emphasis on interaction and participation. Conceived by the Queensland Multimedia Arts Centre as a vehicle to allow Queensland artists to develop, realise and distribute multimedia art, the festival’s hybrid of performance, photography, sculpture, internet and rave culture created an arena for vigorous engagement between art, technology and audience.

Sculpture and photography combined with CD-ROM installation in the 240 Volt group show at Metro Arts, to envelop the viewer in a perpetually evolving mesh of structures, images and sounds. A (seemingly) random sonic loop of grunting, pissing, laughter, coughing and teeth brushing accompanied Mark Parslow and Stuart Kirby’s In the Wolerverine’s Web. Its dissonant tones bled into the space around Nicole Voevodin’s mystery cabinets, Cash Corpus #3, and James Lamar-Peterson’s animal sculptures fabricated from obsolete circuitry. Simultaneously menacing, cute and annoying, the soundscape was, intermittently, peppered with gunfire from Lucy Francis’s wicked reworking of the grassy knoll: Jackie O. Clicking on a screen-sized image of the first lady, the viewer provides a catalyst for the assassination (and Jackie’s pupils ricochet satisfyingly around her eye sockets in tempo with the shots). Gunshots reverberated throughout the gallery, over the delicate seaside ice-cream van chimes that attended Benjamin Elliot’s vacation theme interactive photography. The intricate aural and visual environment fluctuated constantly as viewers navigated sculpture and interacted with installations.

Elaborating on the possibilities of audience participation in a mixed media event, Gigga Bash (Global Overload) produced by Jeremy Hynes of MomEnTum Multimedia, featured the interior of the Hub Cafe covered with 450 metres of alfoil by Cyber Nautilus Performance Group. Members of the audience were wrapped into the environment with alfoil—living sculptures at 16 work stations linked to the internet, searching for visually stimulating material to project to the remaining spectators. Simultaneously, the event was filmed, remixed with audience-generated images from the net, distorted with other footage and extruded back onto a nine screen TV wall which was itself in turn filmed and re-projected, condensing the media into a ultra concentrated compound of film, production, cyberspace and audience collaboration.

Metal framed novajet prints in Close as Life at Secummb Space, the Plastic Energy dance party with visuals by Troy Innocent, music by Ollie Olsen and Cyber-femme Griller Girls exhibition, further expanded the diversity of the festival, providing additional opportunities for engagement and interaction with a variety of technologies and practices. Workshops in multimedia authoring and the internet, lectures from Dorian Dowse on the implications multimedia holds for fine art, Troy Innocent on the possibilities of artificial life and video conferencing from New York with internet artists discussing issues facing web designers in the US and Australia, meant that eMedia avoided becoming a superficial feast of images and sound, achieving instead, a forum for erudite discussion of and energetic experimentation with multimedia.

eMedia97 QMAC; Metro Arts; QUT; Qld Museum; Hub Cafe; Secummb Space; Out!; Quantm; Brisbane May 23-June 6

RealTime issue #20 Aug-Sept 1997 pg. 26

© Caitriona Murtagh; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Nicole Johnston, Michelle Heaven and Luke Smiles in Suite Slip’d

photo Brendan Read

Nicole Johnston, Michelle Heaven and Luke Smiles in Suite Slip’d

The idea behind Green Mill’s 1997 program, Heritage and Heresy, is timely. There’s a feeling in the air; dancers looking back to see their tracks stretching behind them into the distance. Perhaps they seek proof that they’ve really gone somewhere. The subject matter of much recent work, at Green Mill and in Sydney, is indeed lived history, and we’re shown these tracks, paths of complex endeavour, entwining personal and professional experience, a detailed and private history of growing up and settling in, an embodiment of craft.

Sue Healey’s own history starts with ballet. In June, The One Extra Company presented her Suite Slip’d at The Performance Space, but I was happy to have seen it first in rehearsal a week earlier, prior to the addition of costumes and set. There’s something special in the fearlessness and ease of rehearsal, where sequences and physical relationships are still somewhat open-ended, without the fixity that performance requires. In the first trio, the dancers took the behavioural and stylistic elegance of 17th century French court dance, throwing it (and each other) around the spacious bare studio, with a quick, sweet understatement which belied the fast, slippery complicated precision demanded by the choreography. For someone who knows ballet, a slight tilt of the chin, a glancing epaulement, a sudden flutter of hands, all embody a world of meaning, both then and now, within which the dancers’ social and professional lives are played out.

The second half presented a kind of dramatic confrontation: two new dancers, new style, new material. With the addition of set and costumes in performance, I could barely shake the Sharks and the Jets out of my head, as subtle posture became a social currency no less extreme than that of 17th century. Both choreography and dancing in the first section were hard to fault, and while the suggestion of dramatic narrative might have been a persuasive guide, I preferred the more ‘abstract’ interrogation of dancerly ritual which was becoming visible prior to the complications presented by staging for performance.

Trevor Patrick in Leap of Faith

photo Jeff Busby

Trevor Patrick in Leap of Faith

Some works at Green Mill seemed to embody a kind of artistic coming of age. Trevor Patrick’s solo, Continental Drift, was one of these, performed as part of Dancework’s presentation of Leap of Faith. The weight and pathos of this work catches you by stealth. Small words, phrases, gestures accumulate and pack down, like strata in a land mass. He shifts sideways, black-suited, across the stage, backed by burnt orange screens. He bumps up against shadow, unknown experience, until it recedes. His movement is clean, the text simple but pervasive. He speaks of experience, events which just happen, ways of learning to do and to be; progress through life is measured by an accumulation of such events, which by themselves do not provide actual direction. The shape of his life becomes simply doing what he has done, going where he has gone, “dense episodes of experience” packing down into a pathway of sorts. When the other side of the stage is reached, the end of the road, he has cleared that space of shadow, and the ground is firm, marking a place of experience, for us as well, between the sacred and the profane.

–

Suite Slip’ed, by Sue Healey, The One Extra Company, The Performance Space, June–July 1997

Continental Drift, by Trevor Patrick, part of Dancework’s Leap of Faith, Green Mill Festival, June–July 1997

RealTime issue #20 Aug-Sept 1997 pg. 40

© Eleanor Brickhill; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Marrugeku Company, MIMI: a Kunwinjku Creation Story

When the Marrugeku Company presented MIMI: a Kunwinjku Creation Story in Arnhem Land last year, word has it that even the sky held its breath. This remarkable collaboration between Stalker, the Kunwinjku people of western Arnhem Land and a number of Indigenous artists incorporating stilt walking, acrobatics, dance, light, fire, smoke and Indigenous music is one of a number of contemporary performance works in the Festival of the Dreaming, the first of the Olympic Games Arts Festivals, opening September 14.

In Wimmin’s Business, Rachel House performs Nga Pou Wahine by Briar Grace-Smith with musical composition by Himiona Grace; interdisciplinary artist and a leading figure in Native performing arts in Canada, Margo Kane presents Moonlodge; in More Than Feathers and Beads, Native American, Murielle Borst performs a tragi-comic routine about the lives of Native women; Deborah Mailman recreates her powerful monologue The Seven Stages of Grieving; Leah Purcell, who trained as a boxer and a singer, bolts through the harsh culture of country Queensland in Box the Pony based on a real life scenario and written by Scott Rankin; Ningali Lawford is back with her remarkable stand-up performance Ningali and Deborah Cheetham manages to interweave a few operatic arias into White Baptist Abba Fan accompanied by the Short Black Quartet.

The plays on offer are similarly broad in scope: Bindenjarreb Pinjarra is about truth and justice the Australian way. Using satire, improvised performance and a strong physicality this work premiered in Perth and is a collaboration between nyoongahs Kelton Pell and Trevor Parfitt and whitefellas Geoff Kelso and Phil Thomson. Meanwhile, Bradley Byquar, Anthony Gordon and Max Cullen perform Ngundalelah godotgai (Waiting for Godot) in the Banjalung language with English surtitles. Julie Janson’s historical odyssey of the Aboriginal bushranger Mary Anne Ward, Black Mary, which premiered at PACT Youth Theatre, is given an epic new production by Angela Chaplin at Belvoir Street Theatre’s vast Carriage Works venue. Noel Tovey blends Elizabethan, Aboriginal and contemporary theatre styles and an all-indigenous cast in A Midsummer Night’s Dream with dreaming designs inspired by the works of Bronwyn Bancroft, computer animation by Julie Martin and musical composition by Sarah de Jong. Unashamedly feelgood is Melbourne Workers Theatre collaboration with Brisbane’s Kooemba Jdarra on Roger Bennett’s Up The Ladder, an affectionate evocation of the 1950s sideshow boxing matches. NIDA students will present Nathanial Storm, a new musical by Anthony Crowley, directed by Adam Cook, musical direction by Ian McDonald.

The street theatre program includes Malu Wildu, a new indigenous music ensemble performing original song based on the Dreaming stories of the Torres Strait and Flinders Ranges. Also on the streets are Tiwi Island Dancers, Janggara Dancers from Dubbo, Koori clowns Oogadee Boogadees, and Kakadoowahs, a new work from four Koori artists produced by Tony Strachan of Chrome.

The festival opens on September 14 with a smoking ceremony staged on the site originally known at Tyubow-Gale (Bennelong Point). featuring large numbers of dancers, singers and 30 didjeridu players directed by Stephen Page.

There’s a strong focus on dance-music works in the festival. For one night only there’s Edge of the Sacred, a collaboration between the Aboriginal and Islander Dance Company choreographed by Raymond Blanco and with Edo de Waart conducting the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in Peter Sculthorpe’s Earth Cry, Kakadu and From Uluru. And on the same evening an all too rare opportunity to hear the haunting opera Black River by Andrew and Julianne Schultz with Maroochy Barambah performing in a semi-staged performance with the Sydney Alpha Ensemble; the performance is conducted by Roland Peelman and directed by John Wregg.

Bangarra Dance Theatre dust off the ochre to explore water worlds in Fish choreographed by Stephen Page with music by David Page. Didjeridu player Matthew Doyle, choreographer Aku Kadogo and percussionist Tony Lewis give modern voice to a Creation story in Wirid-Jiribin: The Lyrebird performed by Matthew Doyle in the Tharawal language.

International guests include the predominantly Maori and Pacific Island all-male contemporary dance company Black Grace who were first seen and much enjoyed at Dance Week at The Performance Space last year. They return with the premiere of Fia Ola. Silamiut, Greenland’s only professional theatre performs Arsarnerit, a dance-theatre work about the northern lights; and also visiting are the ChangMu Dance Company from Korea. There’ll be free performances in First Fleet Park by The Mornington Island Dancers (NT); Doonoch Dancers (NSW south coast); Yawalyu Women of Lajamanu (central desert); Tiromoana (Samoa); Ngati Rangiwewehi (Aetearoa); Naroo (Bwgcolman people, north Queensland) and Papua New Guinea’s Performing Arts Troupe.

Visual arts by Indigenous artists will be showing at all major institutions including an exhibition about Indigenous Australian music and dance at the Powerhouse Museum; the Art Gallery of NSW hosts Ngawarra in which artists from Yuendumu create a low-relief sand painting over five days in contact with their peers by satellite; at the Ivan Dougherty Gallery, twelve artists ask, “What is Aboriginal Art?”; At Boomalli, Rea uses mirrors to engage viewers in her interpretations of the Aboriginal body in Eye/I’mmablakpiece; fourteen indigenous artists ‘live in’ and work together at Casula Powerhouse; multimedia artist Destiny Deacon is in-residence for three weeks at The Performance Space Gallery working with local school children on the installation Inya Dreams (website http//www.culture.com.au/scan/tps). At the Australian Centre for Photography a retrospective of works by the late Kevin Gilbert and photographer Eleanor Williams; at the Hogarth Gallery, Clinton Nain gives three short performances of I Can’t Sleep at Night to accompany his installation Pitched Black:Twenty Five Years celebrating the history of activism among Indigenous peoples.

The Baramada Rock concert hosted by Jimmy Little, David Page and Leah Purcell features Yothu Yindhi, Christine Anu, Kulcha, Aim 4 More, Laura Vinson from Canada, Moana and the Moahhunters from Aotearoa and special guests Dam Native and Southside of Bombay.

The Paperbark literature program brings together indigenous writers Herb Wharton, Anita Heiss, Archie Weller, Romaine Moreton and Alexis Wright with international guests Keri Hulme and Briar Grace-Smith in readings, storytelling and forums at the State Library of NSW.

The Pikchas is a week long festival of films screening at the Dendy Cinema, Martin Place and the Museum of Sydney—“no roped off areas here, mate”. Highlights include Mabo—Life of an Island Man (1997); The Coolbaroo Club (1996), Jedda (1955); the Sand to Celluloid series (1995-96); Backroads (1977) and in the bar, a continuous reel of provocative archival footage. As well as the Australian program there are films from Canada, Aotearoa and Germany. Makem Talk involves local and guest film-makers in discussion and debate.

The considerable appeal of the visual arts and film programs aside, for RealTime fans of contemporary performance, theatre and dance the festival holds special appeal in the productions of MIMI, Fish, The 7 Stages of Grieving, Ningali, Bidenjarreb Pinjarra, Fia Ola, Arsarnnerit, ngundaleh godotgai, Black Mary, Up the Ladder and wimmin’s business.

The Festival of Dreaming is an astonishing celebration of the achievements of contemporary Indigenous artists in theatre, performance, dance, film and the visual arts. Rhoda Roberts’ programming achievement is considerable. That she draws extensively on the achievements of recent years, shows just how much great work is available, some of it already nationally and internationally travelled. The addition of new works and international Indigenous guests, makes The Festival of the Dreaming potentially one of those events that festivals so rarely are these days, a genuine celebration rooted in a coherent yet remarkably diverse Indigenous culture staged with a sense of the present, of achievement and with an optimism especially needed at a dark political moment.

–

The Festival of the Dreaming; Artistic Director, Rhoda Roberts, Sydney, September 14-October 6

RealTime issue #20 Aug-Sept 1997 pg. 31

© RealTime; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Casting an eye over the program for the Australian Youth Dance Festival in Darwin in September-October, it looks like the young artists and community dance workers expected from around Australia will be kept on their toes. Early morning warmups in drumming and capoeira begin at 8am followed by discussions on daily themes (Partnerships, Culture & Dance, Collaboration and Initiation, Dance at the Edge and the big one—The Future), sessions beginning with keynote addresses from some notable speakers, opening out to panel discussions with audience participation.

Those not taking part in the discussion can choose from a variety of workshops—teaching methodologies for Primary and Secondary students; workshops with young professional artists; making dance with members of Ludus Dance Company who are visiting from the UK; or take classes in specific aspects of technique (Pilates, contemporary, ballet, tap, capoeira) and then catch video showings.

It’s anticipated that relationships established at the festival may produce some collaborative works and this possibility has been factored into the program with some ‘free’ time allocated after lunch to work together with focus groups or to create pieces with mentors and facilitators. There’s the potential for showing works completed or in progress in the afternoon. Got a minute? Access the internet or attend a workshop with Kristy Shaddock, Clare Dyson and Susan Ditter on how to make a web page. Sponsors QANTM Multimedia have provided hardware and training. If you can’t get to Darwin, daily proceedings will be accessible on the festival website at http://sunsite.anu. edu.au./ausdance.

In the evening, there’s a program of performances including works from Expressions Dance Company (Brisbane), Restless Dance Company (Adelaide), Stompin’ Youth (Launceston), Boys from the Bush (Albury), Corrugated Iron Youth Theatre and Tagira Aboriginal Arts Academy (Darwin).

The program is still coming together but confirmed festival speakers include: arts administrators Michael FitzGerald (Youth Performing Arts Australia—ASSITEJ International), Danielle Cooper and Jerril Rechter (Youth Performing Arts, Australia Council); artistic directors Mark Gordon (The Choreographic Centre), Genevieve Shaw (Outlet Dance and Outrageous Youth Dance Company) and Sally Chance (Restless Dance Company); dancer-teacher-choreographers Christine Donnelly, Michael Hennessy; and dancer-film-maker Tracie Mitchell. Also on the guest list are a number of dance mentors (Cheryl Stock, Maggi Sietsma).

Ludus Dance Company, a leading British dance company for young people will be special guests of the festival (courtesy of the British Council’s newIMAGES program). Based in Lancaster, Ludus tours for 32 weeks a year. The company has a strong reputation for innovative performance and for challenging educational and community programs. Especially interesting for Australian practitioners, is their focus on combinations of cross-cultural dance forms and mixed media (puppets, masks, original music, adventurous costume and stage design).

Much recent youth theatre work in Australia has had strong dance and movement components. It’s not surprising that a discrete area called Youth Dance should emerge. As early as 1994, the Australia Council commissioned a report on the area as part of their review of Youth policy. Merrian Styles from the NT office of Ausdance says, “We’ve organised this event in response to strong demand from our under-25 membership. An advisory panel of young dance practitioners from cities and regions throughout Australia decided that a festival would bring young people together and give us a clearer sense of the directions they want to go”.

Australian Youth Dance Festival, Darwin, September 28-October 3

RealTime issue #20 Aug-Sept 1997 pg. 33

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Zsuzsanna Soboslay and Benjamin Howes, Awakenings

photo Tim Moore

Zsuzsanna Soboslay and Benjamin Howes, Awakenings

Well into rehearsal, I ask the conceiver-performer of Awakenings, Zsuzsanna Soboslay, is it the envisaged work that is emerging? She explains that the structure is becoming more overt, “a good thing, the outward shape, but I’m waiting for the interior to re-emerge, the inflections in the body that the work began with. They’re coming”. This waiting happens to most of us to some degree mid-rehearsal process, but food-poisoning in Istanbul over two months ago on the way to LIFT97 in London, has left her asking “Is this my body?” and querying judgments made in response to it in rehearsal. She seems confident nonetheless that the body, and the vision of the show with it, is there.

I ask designer Tim Moore if the set’s evolution has been subject to transformations. He explains that the set was ready for the first day of rehearsals so that the performers could live with and learn it, especially given that “it has a life of its own, has four or five actions—parts of it slide up and down, it revolves, has at least two levels to work on physically and is both reflective and transparent”. The initial inspiration came from a workshop two years ago at the Centre for Performance Studies at Sydney University and from Frank Wedekind’s Spring Awakening, the German classic of thwarted and brutalised child-innocence which has inspired Zsuzsanna’s Awakenings. This is a set then that is expressionist in impulse, a device of discovery and grim witnessing, a window on a child’s world, “a massive window which is also a door”. “It’s monolithic,” says Moore, “but now I’ve disappeared it a bit, changed the surfaces—you can see it and see into it. Originally it was a staircase on wheels but it’s transformed into a room that can become a cage, a space for the performers to discover things, with room to move”.

Zsuzsanna comments that the set has provided “landscapes, corridors, circles, a sense of window and horizon”, that the capacity of the set to revolve has enhanced the relationship between the performers; the way a door turns helps realise the transformation in one character oscillating between mother and daughter roles, amplifying swings between innocence and knowledge, showing what gets hidden, what disappears.

Complete as the set is in construction and in its life in rehearsal with the performers, it awaits the transformations of light and video projection. The latter, as often, is quite a design challenge, having to find the right surface to project on, where to place the images, and how to make them complementary or counterpoint to the set and the action, not a distraction. This is especially the case, says Zsuzsanna, when the images are about “going inside memory, into the body”. Already the scale of the set and its proximity to the audience will amplify their own recollections of innocence and awe. The video imagery will take them further in and back, but with its own dynamic and in relation to what’s happening live: “A soft-shoe dance on video”, says Zsuzsanna, “doesn’t yearn, but the accompanying song does”. The challenge of the meeting of live and recorded actions and of creating a soft surface to hold projected images clearly preoccupy the thoughts of Awakening’s creators at this stage of the work’s development.

As does the music. “Sound”, Zsuzsanna retorts. “We might have started with Schoenberg, but save a brief quotation, his music is not in the show. We don’t have big slabs of music from the late 19th century, early 20th (Spring Awakening was published in 1892). It’s in our bodies, the music is ours, in our movement. We are aware of sources of sound—the pulse of nursery rhymes, marches, beer hall songs; these melodies can block out other, earlier melodies.”

The sound score for Awakenings is being created by sound artist Rod Berry and is about to enter rehearsal with its own vocabulary for the performers and the set to work and live with. It’s a process in which “movement can evolve into sound, sound into movement”. “Rod will create sounds around the silences. He won’t fill the space. He’ll make the blackboard and different parts of the set speak. Sound helps one travel in time, shifts you historically, for example as a performer transforms from youth to crone; sound can demonstrate time as contiguous—the past and present in one moment.”

This moment, for Zsuzsanna and Tim, is one such combination of past—the inspiration of Wedekind, the seminal workshop of some two years ago, the recent creation of the set—and present—living in the set, working with projected images and sound, the interior of the work re-emerging and, doubtless, transforming. Awakenings is about change: “Change comes from vulnerability. Change comes from desire. Can a culture change when it holds fiercely to its identity and power?”

Awakenings, conceived, written and performed by Zsuzsanna Soboslay, with Benjamin Howes; sound, Rod Berry; images, Peter Oldham, Alan Dorin; set, Tim Moore; lighting, Peter Gossner. The Performance Space, Sydney, August 14-24

RealTime issue #20 Aug-Sept 1997 pg. 38

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

How does one interpret or use a classical dance form to tell a new story, one that is relevant to the Indian Diaspora, rather than a traditional religious tale which may also be of value, but a soft option in the sense that it may not challenge the community dogma and, worse, may fuel prejudice? This is a question asked by many new Indian dancers who are classically trained. Breaks with traditional story-telling techniques have been made by contemporary British-Asian choreographers such as Shobana Jeyasingh using Bharatnatyam and, to a lesser extent, Nahid Siddiqi using Kathak. In eliminating the orthodox costume and make up of Kathakali, but also in her choice of subject matter, Maya Krishna Rao makes a welcome addition to this modernising principle.

In his classic short story, Khol Do, Saadat Hasan Manto deals with the communalism of the partition of India in 1947. Trains travelling between Amritsar and Lahore would depart packed with people hanging onto the sides and sitting on the roofs, but would arrive at their destination with their entire passenger load slaughtered.

As we have witnessed recently in Eastern Europe, history repeats its unimaginable horrors, re-named as ethnic cleansing, as if somehow the mere act of re-naming sanitises the atrocities human beings are capable of. In the re-telling of Khol Do, Rao’s solo performance in a British context is a sublime experience.

An aspect of classical Indian arts is that an artist may present nine rasas (moods or flavours) during the exposition of an improvisation or rehearsed set piece. This range of feeling usually allows an audience to empathise with a work on different levels. Maya Krishna Rao’s opening minimal gestures are executed with the technical precision of a classically trained dancer and, enhanced by Gavin O’Shea’s sound design, evoke the atmosphere of an Indian train journey. Overall though, I felt the emotions expressed in the work were limited. Viewing Khol Do, I felt the pathos of the father separated from his daughter and the desperation of his search, but not his love. The motif running through the performance is the daughter’s expression of fear, Rao’s gestures of fright being expressed to effect in Kathakali abiniyah (visual expression) of mudras (hand gestures) and facial movements, in particular, the eyes. The nritya (pure dance) element here was minimal and I thought could be developed further to convey a feeling of space. Instead of restricting the performance to the confines of the strong red central dais, it would have been liberating to see some of the explosive Kathakali movements outside this sacred space, in perhaps the profane space of the margins around the dais. Rao’s Kathakali nritya, both in footwork and poses, transmits a high level of energy and consequently, is more convincing in delivery and reception than the earlier slower movements.

Maya Krishna Rao is courageous in dealing with the subject of ethnic violence during the formation of Indian and Pakistani national identities. The bloody wound that opened up during Partition never healed and is now being salted by fundamentalist Hindu, Muslim and Sikh factions in the Indian sub-continent and supported by the Indian Diaspora. The religious premise for this sectarianism is again raising its ugly Janus head. In order to hold on to their imaginary homeland in their respective mother countries, Asian communities in Britain are unfortunately now more sharply divided than ever. In this respect, one welcomes any artist who transgresses absolutist ideologies. The general disclaimer that Asian communities in the West make of this type of work, especially if it has been created by migrant Asian artists, is that they are not speaking with an authority which is authentic—“the Asian community is not like this”. They refer to the artists’ “non-Indianness” for hybridising European and Eastern artistic aesthetics. The artist is thought to be tainted by the vagaries of Western political, social and artistic preoccupations. British-Asian artists are described in the Asian community press as having lost their roots in adopting modes of telling their stories or using new forms to re-tell old stories.

Khol Do (The Return), Battersea Arts Centre, June 10

RealTime issue #20 Aug-Sept 1997 pg. 44

© Zahid Dar; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

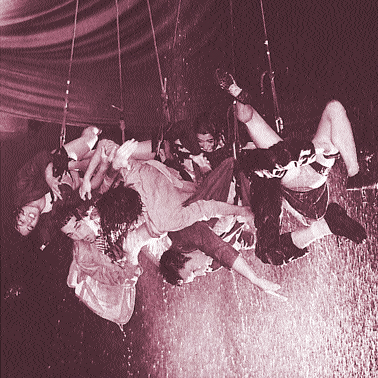

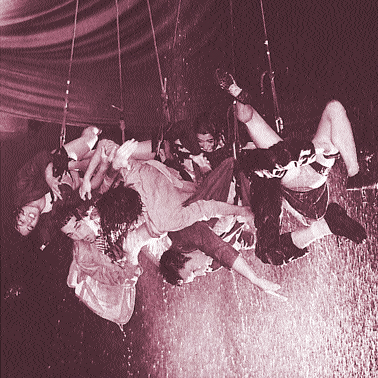

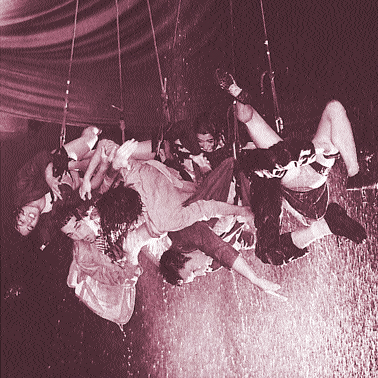

De La Guarda’s Perioda Villa Villa

It’s the first time that I’ve seen any public event involving Argentinians since that drowning war when my sister and her children went in fear. Someone had daubed “Argies live here” in guttural, ugly paint on the side wall of their council flat. It felt good that De La Guarda and I waited until that government was out.

They hung like corpses, drenched and dredged up to the ceiling, or stood on temporary, rigged platforms under pouring water calling, calling, calling. I wept for them.

I saw women and men in civilian clothes (knickers, skirts, ties—subterfuge in mufti, you could shoot them as spies). And a world in whose mores I would like to live—them kissing and hugging strangers in the moment’s trance of eye contact and desire. (The next moment we may have to kill.)

My friend had just made a film on concentration camp survivor, Simon Wiesenthal, when the doors closed on the claustrophobic crush and gas started coming from above. I turned to apologise and couldn’t see her. They didn’t make it easy on us. I wanted to call out, “I don’t want to live here”.

Then the room opened, and there was air, and we were loving the peace with the drowned waking above us and running through showers among us with (it’s in the detail) their socks fallen around their ankles.

Periodo Villa Villa, De La Guarda, Three Mills Island, June 19

RealTime issue #20 Aug-Sept 1997 pg. 46

© Gabriel Gbadamosi; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

De La Guarda’s Perioda Villa Villa

The audience is crammed into a small space whilst the humming through the speakers grows to a drone and then a tune. We are illuminated by the reassuring exit signs; above us a paper ceiling defines the space as cramped, low, capped. Upward gaze; these words look very optimistic here. The vertical is the space for performance. The performance begins with the angelic/devilish sight of backlit sprites casting shadows on the ceiling. Balloons, toys, fluorescent splatter spots fill the paper with joyful play. They are above us, beyond the ceiling, in another world, but we have access to this world. The ceiling is removed. Removed is too passive a word; ripped, dragged, sliced by human missiles, making the world above our heads available to us. Tickertape pours down from the heavens.

After the storm cloud of paper has passed, the performers are precision drivers doing daring manoeuvres except with no cars, no roads and no helmets. WARNING: Do not attempt this at home. Six hundred people, all of us thinking we are as close as we can get, find the space quickly when water gushes from the ceiling. A childlike sense of watching a thunderstorm roll in over the ocean and breaking on the Land; the fear of destructive power, counter-balanced by excitement and relief. The dance and music engulf me. The performers now unleashed from their harnesses hold the audience, hugging, kissing, encouraging us to dance. The energy I want to unleash is being played out in the space above my head. Women running up the wall, this is my Batman fantasy. Drenched and dripping, they pound the rhythms. This is nightclub, rave, concert, theatre, spectacle. I have no head space for theory here. This performance would not be possible where I come from. In Queensland, at our request to burn a few leaves for The 7 Stages of Grieving, the authorities went ape-shit, at one moment threatening to close the show. The laws (internal and external) that govern us would require so much compromise, but here I revel in this moment. There is no danger here, no personal danger that threatens my body. The danger lies in what I will expect from the theatre of tamed lounge chairs and fake velvet curtains. Euphoria.

Periodo Villa Villa, De La Guarda,Three Mills Island Studios, June 18

RealTime issue #20 Aug-Sept 1997 pg. 46

© Wesley Enoch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net