Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

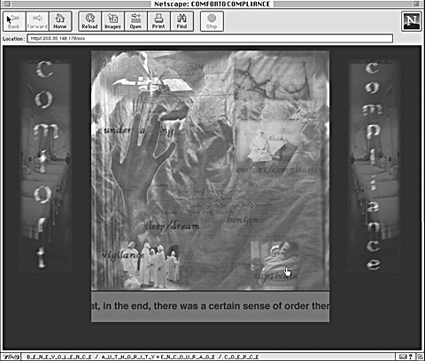

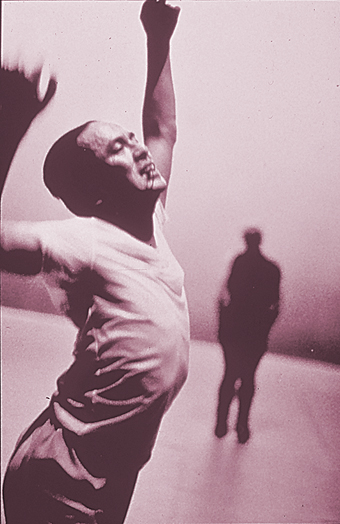

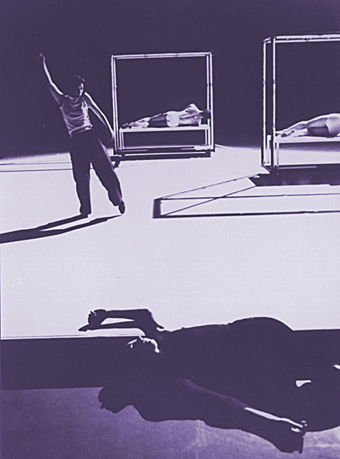

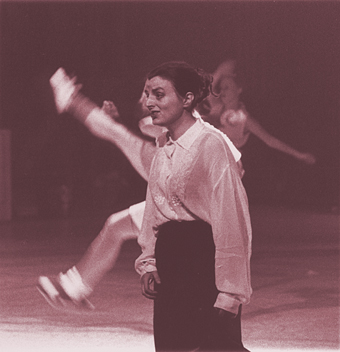

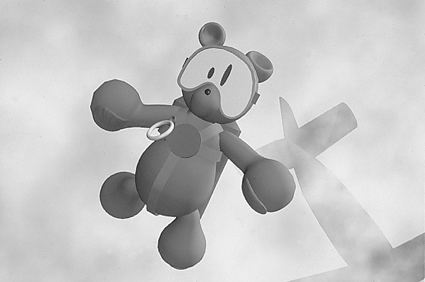

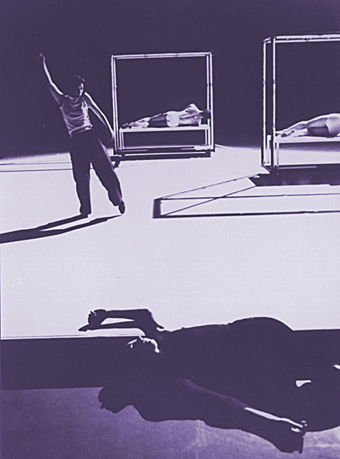

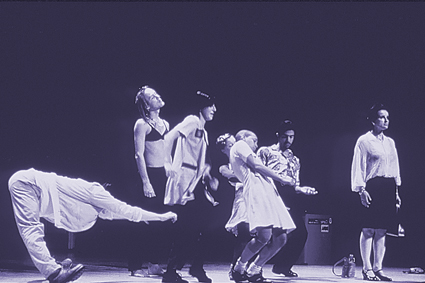

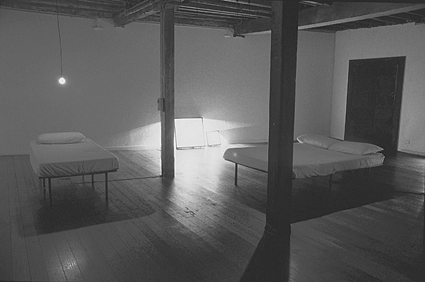

Meryl Tankard’s Australian Dance Theatre, Possessed

Regis Lansac

Meryl Tankard’s Australian Dance Theatre, Possessed

Prelude: The industry

While watching Performing Arts Market performances I was struck by the presence of performance stalwart Katia Molino, seeing her one day performing with Stalker, on another with NYID, both shows requiring considerable physical fitness and dexterity. It was a reminder that there is a broad body of work loosely defined as physical theatre within which various subsidiary forms exist and across which a number of performers participate. Thor Blomfield, one time performer with and now Marketing and Project Coordinator for Legs on the Wall, commented that given “there’s an increasing crossover between companies, for example Legs people working with Stalker”, just how valuable last year’s Body Contact Conference, convened by Rock’n’Roll Circus in Brisbane, was for an area of performance he describes as “encompassing a range of contemporary circus, physical theatre and street theatre groups.”

Blomfield said of participants Circus Oz, Rock’n’Roll Circus, Bizirkus, Club Swing and The Party Line, artists from Darwin, Legs on the Wall, Desoxy, Stalker, some overseas artists and others that “it was an interesting combination that had never come together before. The sense of community in physical theatre has been growing but this conference was the first time we’ve come together formally. It’s timely now to discuss where we all want to go and what we need to do in regard to training, funding and touring. The base for our work was in circus, in the foundation of Circus Oz 25 years ago and that was uniquely Australian though with the influence of Chinese training. Now physical theatre has moved into taking on more European influences and other Asian physical performance traditions.”

Asked why is it important for these groups to talk about the future, Blomfield explains that there are industrial issues to discuss, training proposals (a national circus school), the exchange of information (being informed about overseas work, the rare opportunities to see each other’s work), understanding how companies operate artistically (Desoxy, Stalker, Mike Finch—ex-Circus Monoxide, now director of Circus Oz—spoke about this on a Body Contact panel) and issues like the role of the director, which can be critical for ongoing ensembles working with guest directors. He indicated that there was some preliminary debate about what the proposed training school should do, whether it should provide conventional circus skills or also include, for example, courses in Butoh and various training regimes.

A committee was formed at Body Contact to hold a conference in October 1998 so that these issues could be pursued in more depth, perhaps even to consider whether or not to form an association of companies to promote the standing of physical theatre, which Blomfield describes as being sometimes treated by the broader theatre profession as “the little kid they really don’t know about”. Belvoir Street’s inclusion of Legs on the Wall’s Under the Influence in their 1998 subscription season could be the start of something. Other areas Blomfield would like to see explored include marketing (making the most of marked US interest), physical theatre’s relationship with dance (choreographer Kate Champion has directed Leg’s Under the Influence; one of the Legs’ team was advising Meryl Tankard’s ADT on the use of hand loops for their Adelaide Festival production Possessed) and speech in performance. Physical theatre has proved itself an elastic form, one rich in hybridity and political range as well as being eminently marketable: doubtless for the artists and companies in this area to confer regularly, to see each other’s work, to debate training and artistic issues, to think collectively on industrial and marketing issues, can only enrich their work.

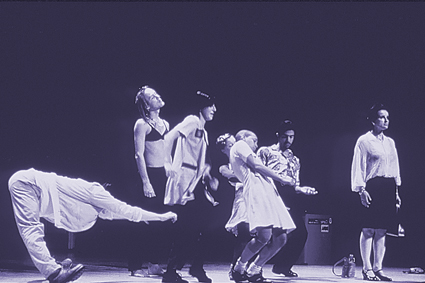

Physical theatre dances

Legs on the Wall, Under the Influence

Adelaide Fringe Festival, February 25

I didn’t know what was cooking, the sausages sizzling at the entrance to the ‘performing area’ situated on the seventh floor of the carpark, or the audience beneath the tin roof in 40 degree heat plus lighting, say 45. Either way it wasn’t a good smell. And yet, Legs were cooking, giving a virtuosic physical performance despite being awash with sweat. They pretty much held their audience though it wasn’t clear how Legs were managing to hold each other. This is a company blessed with a kind of performance ease, physical feats are achieved without ‘drum rolls’ and the acting is laid back and lucid. To ease into this, a prelude of apparently casual exchanges and acrobatic events (and their ‘accidents’) unfolds as the audience enters asking has the show begun—well yes and no (except to say that this particular postmodern gag is a bit overripe and is somewhat scuttled when lights etc finally do mark a start. A pity.)

Physical theatre has always lent itself to the choreographic impulse (doubtless inherited from the lyricism of the circus trapeze artiste), and is certainly evident in Desoxy and The Party Line, but here, under the direction of choreographer Kate Champion, it goes further, not into dance per se, but into a dextrous patterning of moves and holds that provides a magical fluidity for the work, everything from small gestural motifs and work with domestic objects and clothing to large scale sweeps of movement and a coherent dance-theatre totality. It was fascinating to watch the thoroughness and the inventiveness of the movement and I found myself surprised at how much the performers must have had to absorb choreographically when already faced with considerable physical challenges. Legs are not to be underrated. As for the show as theatre, this early version was too discursive, key images (as the broad narrative works itself out) seemed to repeat themselves as long in duration as their original incarnations, one-off numbers looked more than suspiciously like unintegrated individual performer favorites, some scenes wandered too far from the dangerous intimacies central to the work, too many lines fell short of funny and into whimsy, personalities were just a little too abstracted, and the overall shape plateaued early, a not unfamiliar problem for physical theatre with its constant battle to escape the string of tricks. But for all of this it’s very good and by the time Under the Influence reaches its Sydney season hopefully everything that already works—the physical skills, the choreography, the ease of playing, the sensual energy and cheery fatalism—will be sustained by tighter scripting and shaping.

Dance does physical theatre

Possessed

Meryl Tankard Australian Dance Theatre

Ridley Theatre, Adelaide Festival, March 14

Possessed is the next stage of Meryl Tankard’s adventure with dance that leaves the ground, seen first in Furioso but also evident in another way in her choreography for the Australian Opera’s Orfeo. I have a vivid memory clip of her dancers as Furies flinging themselves relentlessly at a giant revolving wall. It looked dangerous. There is some harness work (first explored in Furioso) in Possessed’s central scenes, but the impressive new material that frames the show in the first and last scenes suspends the dancer by wrist, or by both wrist and ankle, using loops. While doubtless placing enormous strain on joints and muscles, there are advantages for fluidity and freedom of movement for the dancer in the air. Of course, it’s not a trapeze and they’re starting from the floor, so there’s not a lot they can do by themselves without help from the ground, the push that leads to swing as their earthed partner determines the direction of the swing and acts as catcher and cradler (and assistant). That said, once airborne, the dancer can amplify their swing and create delicious physical shapes and defiant arcs out over the audience. It looks dangerous as the arcs extend and the dancers swing fast and low over the fence around the big stage. It’s exhilarating because it looks so free, so unencumbered. And these dancers look so at home taking the grace they defeat gravity with on the floor into the air. The opening scene featured male pairs, generating a surprising intimacy, the aerial device allowing them ease at lifting the fellow male body, leaps into space being taken off the body of the ground dancer, returns from space greeted with great care. That aside, the women dancers provided some of the most spectacular and unnerving flights. If Possessed has any meaning, it tells of an obsession with flight and the defeat of gravity. Psychoanalyst Michael Balint called these possessed “philobats”, lovers of flight, and suggested that we all have some of that obsession in us, though we’re mostly happy to let others do it for us, at the circus for example. Not surprisingly then, the audience for Possessed clapped and cheered at every stage of these flights.

Another possessed body appears in the second scene—an obsessive sporting body, its centre of gravity low to the earth, absorbing everything in its almost militaristic path (shades of NYIDs’ monopolistic one-dimensional fit body at the Performing Arts Market), first possessing individuals in separate gender groups and then obliterating even that difference, taking with it every expression of pain and anxiety and the strange shapes that pitifully express them—a clawing fall to the floor or a wipe to the eye. A later comic scene has a group of men parading like women in a beauty contest—high heels and parodic stances (but around me the audience broke into shrill cheers exclaiming, “the Chippendales, the Chippendales!”). A line of women in red dresses challenge the men to do it right and all but one fail and exit, the victor taking his place centre line, locked in the same smile he began with, totally absorbed.

Much else in the evening seemed incidental, making it a show of bits and ultimately a bit of a show, despite the consistently powerful contribution of the Balanescu Quartet. The first, second and the final scenes of Possessed could be assembled into a powerful work instead of the sprawling entertainment it unashamedly is. Some in physical theatre might see Tankard as appropriating their aerial space, and there are times when the showbiz of it all seems to say so, but physical theatre is not all circuses these days and Legs on the Wall have a choreographer-director who’s worked with DV 8. Stalker have come down off their stilts and are working the air in other ways. It’s an intriguing physical moment.

Gravity Feed, The Gravity of the Situation

photo Heidrun Löhr

Gravity Feed, The Gravity of the Situation

Embracing the unbearable

Gravity Feed, The Gravity of the Situation

Bond Store tunnel, The Rocks, Sydney

March 19 – 22

Gravity is upon us, from above and from beneath. It is weighty, it sucks, it pulls, it compels and commands from all sides. We act because we must, bound to this archaic form the cube which contains nothing yet everything. This is the tabernacle of damned creatures, and in its lightness is the source of their constant anxiety. Program note

Part of me wants to read this show literally. I resist. This is performance. We all inch our way in past signs that intimate danger. We are in a high ceilinged tunnel not in a theatre. Men in tired suits, some unshaven, hair straggling or shaved creep and dart about, oblivious to us, gathering lit candles in paper bags, placing them on a high ledge above a tall ladder, or in a cluster on the ground further down the tunnel. Me, I think I’m witness to some tramp ritual, a subterranean fire-worship culture, such is their care for their charge, fire that disintegrates that which is heavy into flame and ash as light as air. A soundtrack rumbles the resonant tunnel into a hymn of unremitting threat and mystery. It doesn’t let go of us. One of the men tugs at a huge metal cube walled with what looks like triple-ply cardboard (light but remarkably tough) and lets it roll down the slope of the tunnel, barely impeding its speed with all of his bodyweight. This is the first of the journeys of the cube, a miraculous device, Prometheus’ boulder to be rolled endlessly up the slope, a self-generating Platonic ideal that grows new walls as soon as old ones fall away (great design and construction), a perfect material to ignite (it takes and then refuses, glowing like a Red Milky Way), a tabernacle for unwilling worshippers whom it sucks to its centre from time to time and then once and for all. I can read The Gravity of the Situation literally, not as a tramp fire cult, of course (but what about those swinging buckets of flame?); it’s what it says it is, its heavy heart upon its sleeve. But lightness is as feared as much as gravity in this inverted Manicheanism. In a delicate and suspenseful moment the men hold the cardboard walls they’ve liberated from the cube vertically above their heads and criss-cross the space fearfully, juggling the surface area of the walls against the air in the tunnel.

The Gravity of the Situation is something more than the beginnings of the great work we’ve all been expecting from Gravity Feed after The House of Skin. What it needs now, now that the scenario is there, the shape is there, the marvellous cube is there, is for all the attention possible to be lavished on the choreography of bodies and space, a distillation of the opening, the establishment of a surer relationship between performers and Rik Rue’s awesome sound composition, and even perhaps opening space in the soundtrack so we, the congregation, can hear the performer bodies groan against the weight of the light and the heavy. In the past, Gravity Feed works have evaporated. Isn’t it time to embrace the unbearable lightness of being?

–

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 33

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Brett Daffy and Kathryn Dunn in Bonehead

Melbourne’s very own contemporary dance company Chunky Move will headbutt its new audience at a preview screening on Saturday May 16 at the CUB Malthouse with their new hour-long dance film Wet commissioned by ABCTV, choreographed and scripted by Mr. Chunky himself, Gideon Obarzanek, and directed by Steven Burstow. A cluey collaboration—Burstow is one of a very few Australian directors interested in exploring the interface between arts live and on TV.

In a city full of fancy footwork, Chunky Move aims to do its bit to shift the boundaries of conventional performance in dance. The company’s move from project-base to three-year funding status will allow it to realise works on a larger scale and to reach a wider audience. Let’s hope that it also buys the company some of the time it needs to seriously develop new work. At the Adelaide Festival, companies like Belgium’s Les Ballet C. de la B. made local mouths water with the relative luxury of their work processes—18 months non-stop for La Tristeza Complice. Nurtured over time, the works are developed further over a number of productions. Robert Lepage (The Seven Streams of the River Ota) says he doesn’t write anything down until the 200th performance!

At this stage, the program is looking decidedly chunky. First up will be a remount of their recent work, Bonehead for performances in Melbourne in May following a tour of the work to South America in April. Gideon Obarzanek sees Bonehead as a work about the body as utilitarian being or object. “At one time,” he says, “the body is able to be an hilarious caricature of a vulnerable victim, while at another, it is seen number-crunching frenetically through virtuosic movement combinations, reducing it to a mechanism of bone, sinew and muscle.”Bonehead features some of Australia’s most skilful dancers: Narelle Benjamin, Brett Daffy, Kathryn Dunn, Byron Perry and Luke Smiles and newcomer, VCA graduate, Fiona Cameron. A tour to Germany in June will be followed by a collaboration with Paul Selwyn Norton (UK/Holland) after which the company goes into intensive development for Hydra, a large scale work combining performance and sculptural installation which moves dance out of the theatre and into the pool. Hydra has been commissioned by the Sydney Festival and will tour Melbourne, Perth, Brisbane and internationally throughout 1999. In June next year, a new triple bill will premiere in Melbourne including a commission for Lucy Guerin.

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 40

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

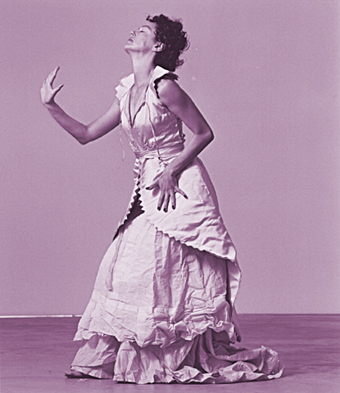

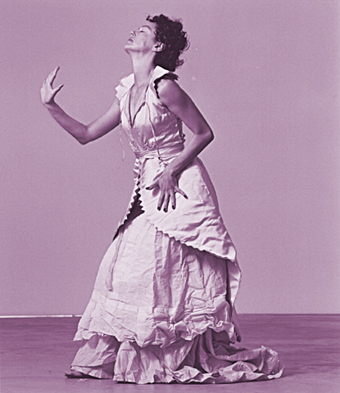

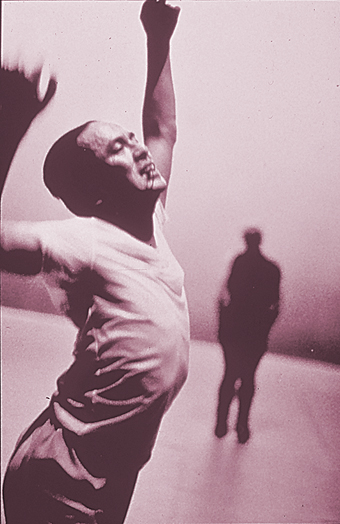

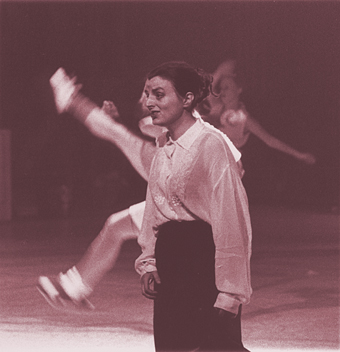

Shelley Lasica, Dress

photo

Shelley Lasica, Dress

In addition to her many solo dance performances in non-theatre venues, Shelley Lasica has developed an extensive repertoire of collaborative works with dancers as well as artists from other fields. In Character X at the 1996 Next Wave Festival she collaborated with architect Roger Wood, composer Paul Schutze and visual artist Kathy Temin. Following her series entitled Behaviour spanning four years and six performance works, a video and a publication, Lasica embarked on a new series of theatre pieces. The first, Live Drama Situation, was shown at the Cleveland Project Space in London last year. The second in the series, Situation Live: The Subject, is a performance about theatrical interaction, loss of memory, coincidence and the subject of space. This time, Shelley Lasica collaborates with dancers Deanne Butterworth and Jo Lloyd, writer Robyn McKenzie (editor of LIKE magazine and visual arts critic for the Herald Sun in Melbourne) and composer Franc Tetaz who works as a composer and sound engineer with artists as diverse as Regurgitator and Michael Keiran Harvey. Situation Live is about what happens in the interaction between spoken, written and movement language.

In Dress, Shelley’s collaborator is fashion designer Martin Grant who created the 10 striking dresses with Julia Morison for the exhibition Material Evidence:100-headless woman at the Adelaide Festival. In Dress we see the way a body behaves and is arranged by the physical habits of clothing. Rather than making a costume for a performance, Martin Grant has designed an outfit that both defines and resists the performance of it. Dress was recently presented at Anna Schwartz Gallery as part of the Melbourne Fashion Festival. RT

Situation Live:The Subject and Dress: a costumed performance will be presented for three nights only at The Performance Space, Sydney, April 15-17 at 8 pm

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 40

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Some dance writers make it a point of honour to avoid personal involvement or knowledge of the dancers or choreographic process prior to seeing a performance, hoping that the work might somehow be less tainted by their own biases, and they will be clear of ‘irrelevant’ distractions, more objective, a state counted as desirable and attainable. Indeed, it would be silly to pretend that having seen a dancer’s work over many years, liking their attitude, understanding the process with an intimate kinaesthetic awareness, a viewer wouldn’t enter a performance with certain expectations, a particular focus and set of assumptions, all of which carry a high intellectual charge.

With this in mind, my understanding of Ros’ work is a long one, having, in this particular project—part of her MA honours thesis at UWS—been invited to document over five weeks the three dancers’ internal thought processes, even to intervene by suggesting what they seemed to me to be doing, and requiring them therefore to respond by explaining in words that very intuitional improvisational modus operandi.

So, with the feeling that any ‘performance’ is just a momentary crystallisation in an ongoing process, I watched this particular manifestation. And in fact, the lights, designed with Iain Court’s delicate touch, and the palpable expectations of the audience induced a feeling of closure, pinning down some of the ideas, and making invisible some of the more vagrant possibilities in the work, threads of ideas I had seen before, too errant to become part of this ‘performance’ pattern.

What I have often seen which distinguishes Ros’s work is that its subject matter tends to be open and layered, inviting contemplation. Each performer can be seen not as a technician parading various accomplishments, but as an individual with a uniquely developed personal language and physical demeanour. The motives for movement are different for each of the performers. Even though my ‘outside eye’ might have relied on its ‘dancerly’ experience, in the absence of a studied choreography, I was drawn more often to what seemed like ordinary, if heightened, behaviour, thoughts and feelings and their physical expression, the ‘non-dancing’ character of each, the parts that can get submerged beneath specific styles.

Julie Humphreys, in her dance Telling Stories to the Sky, has a most distinctive improvisational persona. Perhaps it is not her intention, but her dancing seems to draw from a slightly eccentric emotionality, a whimsical, funny, secret shyness, a state of mind that anyone might remember having been in: not feeling sure, being vulnerable, self-conscious, and aware of your own foolishness, in a place where there is no hiding, and no alternative except to be yourself. It is not about epically beautiful feelings or lines, or ‘aesthetics’, and indeed she is not hidden behind any ‘dancerly’ performer’s shell. What you see is Julie Humphreys being really funny, breathing and laughing, sitting with awkwardly folded legs, running, gesturing, looking sideways, communing with something as if she’s watched, being herself, and reminding us about the soft, secret, silly side of being human, in this particular rather difficult and distracting environment, this public exposure called performance.

Gabby Adamik’s solo, Tidal, seems more straightforward in its dynamics. She works not so much with a muscular strength as with a central physical core to her body, undergoing seizures by waves and currents, pulling her to extremes, and back to calm, being thrown around, but clothed in a more indeterminate flesh which plays little part in these internal ebbing tides. Gabby’s is a short, contained and well-formed idea, a strong and supple solo, with a rich, clear texture, a rising-ebbing symmetry.

Ros Crisp’s duet with Gabby, Audible Air, has a similarly uncluttered structure: the dancers commence, widely spaced and obliquely angled, on either side of the stage, moving around and past each other, to change places. There are meetings in this dance, responses, awareness of each other’s presence, self-containment, listening. It has a cooler, less intensely personal quality. You might see only one dancer at a time, widely separated as they are, depending on which side of the space you sit. I was aware of their changing spatial relationships, creating a deep and acutely angled field. The image of a blurred distant figure behind one which was very near and crisply focused, made a strange photographic image, emotionally more removed than the other pieces.

Ros’s solo rendition of Audible Air, opening the program, also works with a quiet physical listening, not so much concerned with perceiving external sound, but with a slow internal cyclic resonance, waiting for the seep and swell of sensation and attendant imagination through the body cavities, through the breath, along axons, charging synapses, waiting, filling and emptying again from her body’s contours.

On one level there is a clear dancerly beauty in her energy and gesture. Her expression has a practised and refined emotional sensibility about it—unlike Julie’s more unravelled quality—which rests easily on a long and established physical practice. If speed, control, flow and precision are not primarily what she is concerned with, those qualities come to work inevitably and extraordinarily, providing a compelling focus for those who might find unsettling any departures from orthodoxy.

In the program notes, she has quoted Claudel:

Violaine (who is blind): I hear…

Mara: What do you hear?

Violaine: Things existing in me.

–

Omeo Dance Project, Four improvisations directed by Rosalind Crisp: Audible Air, Solo—Rosalind Crisp; Duet—Rosalind Crisp and Gabrielle Adamik; Telling stories to the sky, Julie Humphreys; Tidal, Gabrielle Adamik. Omeo Studios, Newtown, February

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 40

© Eleanor Brickhill; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Wendy Houstoun, British performer and director of dance theatre, is on the move. She returned from teaching in Vienna to perform in a platform of British contemporary dance in Newcastle. She next travelled to the Adelaide Festival, to perform her solo trilogy, Haunted, Daunted and Flaunted. Before that she completed a site-specific commission for the Spitz cabaret club in London and conclude a mentoring project for emerging choreographers at The Place Theatre. Houstoun has been to Australia before, having toured with native Lloyd Newson’s company DV8. She has an affinity with Australians. “People often think I’m Australian”.

Houstoun’s trademark melange of monologue, movement and mood swings, hovers around the fringes of the contemporary dance scene; uncomfortably in the UK, where she is often criticised for subordinating movement to theatricality, more easily in Europe and beyond. In Newcastle she was programmed into the marginal mid-afternoon slot, but still stole the show with the international promoters. Her part time manager has been avalanched by offers for touring. “The Italians didn’t understand a word I was saying”, Houstoun shrugs, “but they still wanted to buy the work”.

Working on the Spitz commission when we met, Houstoun was remarkably chipper about her lack of progress: “That excruciating first step can take ages. One minute of dance can take five days to make”. On her own again, Houstoun is nevertheless clear that solo shows such as the trilogy are not the way forward. “Haunted was a way of breaking with Lloyd,” she admits, referring to the many roles she has created for DV8. “We were in a bit of a trap. We always started from devising and patterns would emerge and we’d repeat them and become sort of mutually dependent. It became hard to change or accentuate our ways of working. I would always end up cranking up the energy to get on the edge and become manic.” The links are not broken however, “Lloyd still comes to have a look at what I’m doing. He can see what is under the work”.

Houstoun is not in any hurry to get back onto the treadmill of international touring. “The trick is to keep free. There’s a degree of ordinariness in my work which I want to maintain. It’s to do with the claims you make for what you do. I want to avoid raising too many expectations. I can still change direction pretty easily.”

She’s at a turning point again: “I’m looking for a more internal way of performing now. I want to make smaller, quieter work. All this expressiveness is a bit juvenile”. The trilogy could already be seen as a first step towards this aim. There are traces of the confrontational characters Houstoun created for DV8, however this work allows a range of personae to take the mike. “I don’t see it continuing”, Houstoun says, “The whole idea of a trilogy was a bit of a joke. It just sort of carried on. The next thing should be quite different”.

Should be. Following Adelaide, Houstoun will work with theatre director Neil Bartlett on a series of performances in British cathedrals. “There will be a choir of 100 people, actors, dancers; anything could happen”. As we discuss the relationship between text and movement in her work, we stray into her experiences as movement director for the Royal Shakespeare Company and Manchester’s Royal Exchange Theatre. Houstoun continues to feed off theatre but reaffirms her commitment to dance as “the best way to get at human interaction. Acting is boring in the end. I get tired of the relationships the actors have with each other, with the director, with the text. They’re always talking everything through. Dancers take direction better, they take on shape without needing to know why”. Directors she admires (and she has workshopped with the best of them) are those who, like Deborah Warner, exhibit, “a light touch”. “Deborah has more of a manner than any specific technique. She leaves a lot of room around things. She’s not subscribing to any school of thought”.

There’s no doubt that the actorly dimension in Houstoun’s work will remain. Houstoun loves words and used them as the starting point for the trilogy. “Words often come way before the music. I often have to switch off, suspend thought to make the movement and to put the two together”. The words she wrote for Haunted were stored away long before the idea of the performance emerged. “I looked at the structure of a few plays. I pinched the odd quote. I’m interested in ways of talking to people, not so much what the words mean, but what they suggest. Speech as resonant of something else.”

In Touch, the short dance film Houstoun made with director David Hinton, there are no words. “A lot of the ambiguity goes out of words in film.” The medium still appeals however, “I enjoy the rigour of film, the way it eats ideas”. The pseudo-documentary she made in 1997, with Hinton again, taught her some lessons. “Maybe Diary of a Dancer didn’t work as a dance film. It was too long, gentle, lyrical. Not slick. It’s genuine. It has helped me to get away from some of the hardness too.”

And Houstoun is back to the impetus behind the steady progression of her career. “I need to negotiate ways to keep on making interesting work.” Whilst she cultivates a self-effacing modesty, it’s clear from the patterns of her career that she is always one step ahead of her current project, retaining the most interesting parts and moving on.

“How do you mature with your work?” she asks searchingly. “Credibility and respect are hard to negotiate.” Yet as the enthusiastic response to the trilogy and the offers of innovative collaborations with directors, musicians and choreographers keep on coming, Houstoun appears short of neither.

–

Haunted Daunted and Flaunted, Adelaide Festival, Price Theatre, March 10 – 14

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 38

© Sophie Hansen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

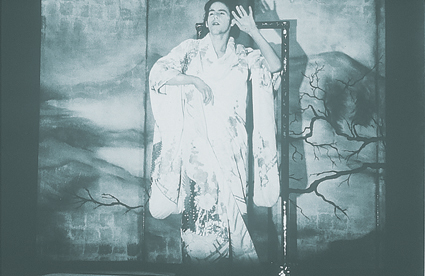

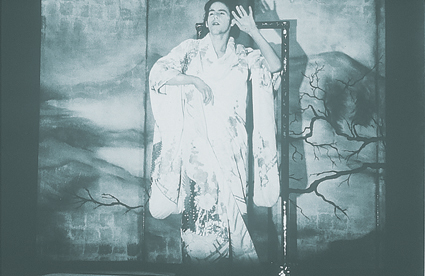

Saburo Teshigawara, I Was Real–Documents

photo Dominik Mentzas

Saburo Teshigawara, I Was Real–Documents

Why do people begin to cough during silences; do they wait for silence. Why do they want to be heard; are they really coughing. No wonder Saburo Teshigawara includes coughing in this work, I Was Real– Documents. It does define a space, small and sudden, where others can’t be. It marks terrain, which is communal, and yet exclusive, like the “sshh” does.

I was a little anxious about seeing this show. I’d seen it in London and loved it. Here it was even better. I was closer for one thing. But, there was something else, something extra that is difficult to describe: perhaps ‘tougher’ hints at it. Something that defied exhaustion, or passed borders, or dissolved desires.

The work is composed of several distinct parts or movements (like music), which flow into one another. These are bracketed by a beginning which is dark and slow, and an ending which is light, brief, and strangely, falsely, idyllic. Teshigawara uses air, air as material, to make space come about for the body, sculpting it with a relentless and often frantic style of dance that is so full of detail and nuance that it saturates the gaze. Looking changes as one understands that ‘air’ cannot be owned, that it, here translated into ‘moving’, is free. Space itself dances; breath is the material of the constant present and the tense and tension of this fact, as force, creates the next moment (or gives it reason to arrive, as ‘thing’, new and surprising). The bodies of the dancers are distinct and alone on the stage. There is only one time when they touch each other, and then it’s as if, in brief closeness, they establish separation by voice, by calling, screaming. In this particular movement or ‘document’, where the voice is amplified, and at once beautiful and painful, it’s clear that every cell of the body holds memory, and as the body pushes its limits, by repetition and commitment to detail—that in some sense is only the extraordinary possibility of every lived second—the idea of air and breath is put into doubt. I mean, the idea of what each is, as space and time, as language, is questioned. These ‘documents’, as they are shown, side by side, are themselves archives, and are, overall, from another larger archive. Each body, in its isolation, in its knowledge of being only itself, carves a world that is complex, abstract, and delicate.

Saburo Teshigawara & KARAS, I Was Real–Documents

photo Dominik Mentzas

Saburo Teshigawara & KARAS, I Was Real–Documents

Teshigawara himself, dressed in white and then black, is compelling; he draws one directly into the dance, to where he is, into his bare fluid aesthetic, into the body he makes for you. Emio Greco is stunning, I hope I don’t have to wait another 12 months to watch him dance again.

Perhaps seeing Documents in the Playhouse, where I was closer to the dancers, made them more ‘real’ and intense. And the experience was overwhelming. I’ve hardly touched the surface of the work, I’ve not mentioned the sound, which is a dimension in its own right, or the costumes, or the projections, or the…

These ‘documents’ pay respect to what it is to be human and to remember and to breathe; and this ‘is’ makes nonsense of wanting to re-define the word ‘sacred’, of wanting to loosen it a little here and tighten it a little there. It too ‘is’.

I Was Real–Documents, Saburo Teshigawara & KARAS; Playhouse, March 11, Adelaide Festival 2000

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 8

© Linda Marie Walker; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

One of the problems of writing about performances is the difficulty of notetaking in the dark. The disruptions it causes to other audience members, its potential to distract the performer, not to mention your own thoughts, are all reasons to avoid it. At the beginning of the festival I bought a pen with a light in it but it’s March 12 and I haven’t used it. Anyway, while you’re writing something down, you risk missing something else. The other difficulty is actually deciphering the notes you make afterwards. It’s like trying to remember dreams. The only words I wrote at the conclusion of Wendy Houstoun’s Haunted Daunted and Flaunted were her final ones. Who knows why I felt the need to write them down. I think endings in the theatre are given way too much importance, like nothing else has happened up to that point. I smiled when Hans Peter Kuhn said in the Forum on Tuesday March 10 that he and Junko Wada worked for a set time on Who’s Afraid of Anything? and when the time ran out, the work was complete. So much for endings.

Anyway the words I thought I scrawled on my program after Wendy Houstoun’s performance were “You can hear the human sound we are sitting here speaking” but looking at the scrawl I found “icnsethehunanoisewersittinghermak” or “I can see the human noise we are sitting here making”. A friend said she thought she heard something about “cities” which just goes to show how imprecise are the twists and turns of memory—more or less the territory that Wendy Houstoun is probing in this remarkable work.

“I am awake in the place where women die.” (Jenny Holzer)

After a festival full of words, my notebook holds a collection of such sentences—impressions, paragraphs scratched over drinks after performances, addresses, snatches of sudden poetry, eavesdroppings, meeting points, restaurants, snippets carried around in my head until I could find a place to write them down, headlines (like the one that appeared the day after the Barbara Hanrahan book was released—“Diary from the Grave” and Friday’s mysterious “Drug Dog in Limbo”. At this stage of the festival there’s an impulse to make connections so today Jenny Holzer and Wendy Houstoun meet on the page.

In note form, Jenny Holzer reads: “Repressed childhood/desire to paint 4th dimension. Art school—attempts reduce daunting reading list distilling books to sentences. Public posters/inflammatory essays/truisms”. (I almost broke my rule and stood up at question time to tell her about Ken Campbell who when he was in Sydney a few years ago performing his show The Furtive Nudist, spent days at the Museum of Contemporary Art writing a list of questions to which Jenny Holzer’s statements might be the answers). “Now installations. Latest work Lustmord—installations of words taking in whole body experience (where the eyes go). Words backwards/forwards/ reflected, juxtaposed with human bones to be picked up and read. ‘Resorted’ to writing, she said, because there are many places it can go but it doesn’t come easily.” Of the many sentences in her presentation I wrote down this one which came from a friend who was assaulted by a policeman: “When someone beats you with a flashlight, you make light shine in all directions”. “Nowadays—romantic inclination—writing text on water—as light—from multiple perspectives.” In Lustmord she writes as the perpetrator, the victim and the observer.

Wendy Houstoun too is all three. Before she enters, a voice from the speakers announces some random violence has been perpetrated on a woman. The voice appeals for witnesses, tells us that an actor will recreate the incident. The work is inspired by the BBC’s Crimewatch. True to life and art after this, my memory of the precise order of events is not sharp. Well, I have sharp memories of incidents. How sharp? Very. Particular movements? No. I’m not a dancer but I’d like to be. Details? I don’t…wait a minute, I remember a sequence where she took us through her dancing life by decades, going way back to the foetal position in 1969. I remember fragments of movements shaking her body. What kind of movements? Well like I said, I’m not a da…but they were unpredictable, unfamiliar, beautiful, no wait, wait, some were memories of other choreographies. I remember there was a Swedish bell dance she had learned which turned out to be incredibly useful, and I agreed with what she danced, sorry, what she said about jazz ballet and the Celtic dance revival. But that makes it sound satirical which is not what I meant to… What do I mean to say? Well the subtlety of… How? Well I remember she said she spent a year moving in two dimensions and how funny she was. But that makes it sound…There was much more. How much? Like I said, all I have is fragments, commentaries on her own body. She let us into her body and showed us her fear. That’s what I said, fear.

Wendy Houstoun is from Manchester, I think. Holzer’s crisp monotone is US mid-West. She is dryly witty, measured and fluid in the flesh. The words she exhibits electronically are short, sharp, sometimes savage. When someone asks her to explain what she means by “Protect Me From What I Want” she laughs and says “I don’t think I can”. Wendy Houstoun’s text is continuous, reminding us just what a physical act speech is. Unlike much dance using the spoken word, here it is not segregated in patches, or voiced-over, or used for interruption or pause. Words are inseparable from her body. She doesn’t enhance them with movement. They are partners. She does little more than speak them as she dances (no mean feat)—speaking of which, how Wendy Houstoun’s bare feet show the shape of a dancing life. And this work could not exist without the words. Without them the wonderful sequence of visual jokes (“Two small movements go into a bar”) would fall flat. The argument from people who don’t like the idea of dancers speaking is that dance has its own meaning and words get in the way. In Wendy Houstoun’s hands, feet and neck, the meanings of both words and movements begin to open up.

On an earlier page of my notebook is one of my first festival experiences, La Tristeza Complice, and as I flip the pages, Les Ballets C. de la B. become the bodies of Jenny Holzer’s “It takes a while before you can step over inert bodies and go ahead with what you were doing”. I wish she had seen those bodies dancing.

Haunted Daunted and Flaunted, Wendy Houstoun, The Price Theatre, March 10; Jenny Holzer; Artists Week Keynote Address, Adelaide Festival Centre, March 11, Adelaide Festival 2000

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 7

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

For a long time I’ve wanted to compose musical scores from bits of text and coloured paper, and stack them on a shelf as a slowly amassing single work, or sentence (called ‘Litter’ perhaps), “as if the logic of fiction is one that pertains to the emotions” (Brenda Ludeman, Visual Arts Program); I’ve wondered what it would sound like, I always wonder what writing sounds like as music, or looks like as dance; and I’d been watching Junko Wada for a while before thinking there was something familiar about her movement, not something I’d seen before, or understood, but something I recognised faintly, or more likely imagined; then it came: she’s writing; it was like watching words come-about, pause, float briefly, and join-up like beads; I didn’t like this thought, I chastised myself for misreading the contorted hands and the calm feet, and the body separated into many parts, all at once; it seemed that each move interrupted itself (like a minor subversion) in its middle so that it was seen, insisted on being seen, and was isolated from what was otherwise fluid; still it persisted, this thought, the horrible ability (want) I have to align various forms to ‘writing’; her body a type of stylus, acute, accurate—each move equivalent to the next—inscribing her dance into me, lightly; the engraving did not occur by harsh cuts, rather by repetitious and concentrated (condensed) strokes; the performance wasn’t about grand vistas, it was some other spatial knowledge: a topology of small dove-tailing details: “(s)he is the worker of a single space, the space of measure and transport” (Claire Robinson, in Folding Architecture).

Junko Wada is not going anywhere (she’s staying put, digging in), there is no journey other than thought (where she was sending me), and this thought is restless and malleable; it is simultaneous thought of here and of that other place so far back there’s no known path; she writes: “back to when I was an amoeba-like single cell”; she’s showing a confined, restricting space, small white empty, to be intricate (to be an architecture folding and unfolding, to be flesh: “Her architecture would be…a local emergence within a saturated landscape” [Claire Robinson]) and endless; that is, the space is strange—in parched geometry there is the naked written and writing body—and this strangeness is left alone by the soundscape of Hans Peter Kuhn; so, therefore, there are two separate works which throughout the performance remain distant (he’s building, she’s building, apart), parallel, creating, for me, yet another space (a third) which belongs to neither, which belongs to the audience (a gift, if you want); the soundscape is as minimal as the dance; and I don’t remember its shapes, instead I remember single sounds, single events–—rain, and to my chagrin the almost too-human ones, his whistling, his voice singing a Marlene Dietrich song, the pouring of the white wine into two glasses, and his footsteps across the floor to where she stood, waiting, and the handing to her of a glass, to toast the idea of ‘ending’ (I liked the music because it did not mark the dance, it did not drive or state, it was comfortable being there, present, and available at will) and this brought me right back, with a thud, to the ‘real’ of human display—to humans performing for humans, in diverse and delicate ways—which chronicles and archives the immeasurable and the unchartable, fleeting fragments (have I told you of the three dresses, red, yellow, blue, of how they worked ‘against’ the body, making its utterance somehow more live, and awkward too?)—and then not so much as ‘noise’ but as ‘objects’ or ‘positions’ in the space where I was, where the watchers were, skirting the dancer’s square, leaving her ‘room’, her work, to her; the third space is a prolonged interval then—where thinking is invited, a thinking between, in this case, movement and sound, or dancing (as it comes from the inside out), and music (as it goes from the outside in); and this making, imagining, of the interval, or plane, by bringing into proximity, but not interweaving, two very considered forms—one that stretches, reaches to the limit, and another that rests, resides with slight tension—collects nowhere else but in oneself (who is saying nothing, while the gathered cells, a universe, are now at the bar taking their first post-show sip, putting themselves in, edging themselves toward, a state of speech [to borrow from Barthes]).

Who’s Afraid Of Anything?, Junko Wada/Hans Peter Kuhn; Space Theatre, March 5, Adelaide Festival 1998

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 6

© Linda Marie Walker; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Needcompany, Le Pouvoir/Snakesong

photo Phile Deprez

Needcompany, Le Pouvoir/Snakesong

Faced, as Jan Lauwers put it in the Festival Forum on design, with the empty screen of the computer, dreaming a starting point, how to enter, how to begin testifying to the disturbance and disruption being caused within me and within the company I keep (strong disagreements abound), faced not simply by any one show but by the sheer monstrous Animal of the Festival itself. Knowing that the moment I enter that first word on the screen I will have made my entrance like a performer onto an empty stage. That breathtaking feeling of actually having to begin the irreversible momentum of the show. Wang Rong-yu, waiting for the rice to begin its unstoppable flow as the eternal wanderers emerge and the red drapes rise. Leda, with the uneasy music enveloping us in the dark, poised to fuck herself with her puppet Zeus, thus beginning the unending human saga of the interplay between eros and death. The American soldier, camera in hand, stepping on to the gravel path outside the Japanese house, about to face the horrors of Hiroshima and with one ejaculation to fertilise a 50 year comi-tragedy of East-West relations. Iyar Wolpe, on the brink of the white cloth stage (screen? page?) of the Bible, opening with those words which are at a soul-point of her race and which seem to speak for so many of the (Judeo-Christian) shows I have seen so far: “My heart is sore pained within me…” It’s there in the names: Burn Sonata, La Tristeza Complice, Snakesong, The Waste Land, Possessed. I appreciated the direct concern in Naomi’s question to Lauwers in the Forum: “Why is your show so painful?” And equally I understood his response (to paraphrase and shorten): “Because the world is a painful place”.

Never was this pain so vivid than when (by chance scheduling) I went, with the wanderers’ song still filling me, to hear the snake’s lament on the destructiveness of power mixed with erotic desire. The very belief system that Songs of the Wanderers, with its final unifying spiral, represented was rent asunder and its loss painfully evident in the disintegrated world of Snakesong. But the need for an aesthetics with which to express this rent and this loss gives rise in the work of both Belgian companies seen here this year to a charged and intense theatricality. It is one which, to use the words of Rudi Laermans in describing Meg Stuart, an artist we saw in the 96 Festival, “inhabits the realm of the uncanny” and is thereby sacred in its own perversely relevant way.

The harmonic completeness of the Taiwanese work, its organic rhythm, with scarcely a step or a move or a shift of tone out of place, the sheer lavish, joyous power of the rice-saturated spectacle, the layers of image and sound are all woven into an impressive, comforting, impermeable texture. It is not a cultural purity that creates the strength and impermeability. The touches of Western modernist expressive dance mixed in with the Eastern ritual journey and the sound track of Georgian folk songs are oddly disjunctive elements. But the artistic force, the accomplishment of the work seemed to me to be one of synthesis. Lin Hwai-min’s previous work Nine Songs is described in the Souvenir Guide as containing “disruptive moment(s)…when the audience is forced to experience a critical estrangement”. I felt no such estrangement in Songs of the Wanderers, from my position in the dress circle watching the map of the journey written into the rice. Here was an example of what Rudi Laermans, in talking from a different angle about the very different work of Meg Stuart, calls an “essential” (stage) image: “these images are so much ‘image’ that they never transform into words…(they) do not affect because of their ‘meaning’ or content, but by their ‘being-an-image’”. And later: “An image cannot be reduced to the metaphorical addition of a number of qualified poses, movements, or gestures. An image always keeps these elements together, and synthesises them into a particular…image”.

The power of a work like Songs of the Wanderers is at times overwhelming, undeniable. But it is for me at one with its limitations. I see it, I hear it, I feel it, I am in awe of it but it remains outside me, choreographed to the point of completion. How do I get in there? Despite Lin’s professed interculturality, this was also a question of cultural difference, of course. Wanderers is at the sacred end of the spectrum. It contains none of the profane late 20th century savvy I witnessed (and recognised) in the Taiwanese work on show at LIFT in London last year. The limitation is not in the work so much as in me—a profane Western voyeur both seduced by and resisting the seduction of Orientalism. I was enormously grateful for the final meditation upon the spiral as time to allow the spell of the work to move through my veins before I re-entered the Adelaide sun to let it sweat out.

Needcompany’s Snakesong/Le Pouvoir demolished all the tenets of artistic form and sensibility upon which Wanderers was based, putting a grenade under the belief in art as a force of synthesis. Snakesong had holes in it open enough to breathe through and deep enough to suicide in. In traditional terms it was undramatic, a-theatrical, inconsistently performed (the acting/performing dualism raised by Keith Gallasch in one of the Festival Forums was here the bloody knife edge upon which the very nature of identity rested), scenographically ‘ugly’, with scant respect for its audience, too loud, too laid back and unresolved thematically. And yet for all this it was liberating, witty, intriguing, confronting, irritating, satisfying, disturbing and with complete respect for its audience’s future.

The image seed from which it evidently grew was that fragment of the Lascaux cave paintings in which a man with a bird’s head and an erect penis lies prone next to the dead body of a bison. What a starting point! There at the birth of Western art is the eroticism of death, the fatality of sex, the paradoxes which have haunted it ever since. Following the opening darkness, the tortuous music and the twisted images of classical myth, the shocking interrogation scene drives hard into these paradoxes with unflaggingly overt histrionics. Did Leda die in sex (the little death) or was her death violent and meaningless. “Did you die (come) together?” The debate powers on and on through double translation. It really matters to them, these investigators, these actors, it is an issue to engage with fully, one important enough to keep chasing through the pain and the boredom, even though they know it is insoluble. It is rare these days to see such raw commitment to an argument on stage. The issue is still crucial enough to make demands on our passions. The myth is still with us, insoluble. We still suffer from it, as the gathering in the contemporary Antwerp scene makes all too clear. The competing egos, the lack of focus, the ache of betrayal, the lack of motive or certain cause, the inability of the characters to work from the heart when the actions needed are so simple and so necessary. The men and the young women are affectless, disengaged, able only to relate through violence and denial. The ‘room’, with its plinths and microphones and objects of a civilisation’s failed history is an empty mix of classical ruins and postmodern kitsch. This is a wasteland of the Millennium. It is little wonder that the extraordinary central woman, whose determination, courage, indomitability and dry dismissive wit is the only whiff of hope in the entire play, ‘dies’ out of it, orders the others off and leaves the mess for us to deal with. Her final wry smile at us is horrifying in its implication.

Needcompany—even the name is a cry for help. “Help me! I’m Belgian!” as the actress in La Tristeza yelled out. ‘Belgian’ in this late 20th century has, through the power of its theatre companies, come to mean ‘human’.

Festival Forum, Design; Songs of the Wanderers, Cloud Gate Dance Company; Le Pouvoir/Snakesong, Needcompany; Adelaide Festival 1998

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 6

© Richard Murphet; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Les Ballets C de la B and Het Musiek Lod, La Tristeza Complice

photo Laurent Phillipe

Les Ballets C de la B and Het Musiek Lod, La Tristeza Complice

My father played a button-accordion, for ‘old-time’ dances. And he was good. He was a sought-after musician, everyone could dance to his music. My mother was a good dancer. My parents took me to these dances, once a month, and taught me all of them. Occasionally at Christmas my father brings out his accordion. And we all sit around the lounge-room and eat and drink. I think my father should be in this festival. I grew up, in the country, with accordion music and dancing. I also grew up with dark nights outside the Mt McIntyre Hall where the cars were parked, where the fights started.

I always wondered what anguish or despair, caused the punches, the smashed bottles, and the violent speech. I wanted to be in the carpark and the hall at the same time. To see both, as if layered. I think I’ve seen this now. The carpark was dangerous, and the dance-hall wasn’t. A thin wooden wall separated them. In La Tristeza Complice (The Shared Sorrow) no wall separates living and dying, just invisible honour. And this dying is not literal, it’s living death. It’s sorrow. And the sharing of sorrow forms tenderness that is so terrible, so resisted and resented, that it barely exists as that. Still, it does. There’s no denying it, thank god. It’s energy that makes each of the ‘characters’ so full of life that they almost burst. It hurts to watch them play it out. Their bodies take a beating, or, they beat their bodies. It’s brutal, and sensual, to watch. There are awful, funny, scenes, yet one can’t laugh, one forbids oneself (somehow), and here lies the tenuous border.

The pacing of the work is careful. It swings from menacing calm to harsh chaos. Neither are deadly, yet each carries death like a precious weight which lifts now and then, leaving the person in a state of even greater loss, as if death holds cells together, is a friend. And this manifests when the winged break-dancer arrives with his small magic carpet, a silly Hermes with a silly message, a trickster whose one prop is a clue, too literal to be trusted—and someone covers it with broken glass for him to dance on. He’ll dance anywhere, be tortured anywhere. Calm and chaos append each other, one beckons the other. There is no rest, even in sleep. The finely tuned roller-skate segment declares the company’s tough poetics; a sustained poetics that keeps ‘faith’ to the bitter end; faith summoned up by one great indignant sentence: “So, who decided all of that”.

The whole work is composed of tiny, fragile, passing events that infect each other, changing the dynamic and dimension of ‘life’. You see a dozen young beings, together but totally alone, and sure of their aloneness. And this is perhaps Platel’s clearest intention: that despite the goings-on of others nearby, or in real contact, the self insists on its utter difference, its own expression; it cradles its own story like a gift. This is powerfully told when the black girl begins to sing her sorrowful song—“if love’s a sweet passion, why does it torment”—and the transvestite crawls all over her, pulls and bites her, drags her this way and that, covers her face, but cannot stop her song.

La Tristeza Complice, as political performance, respects the self whose screams are reduced to single syllables—no, damn, shit, how, bang—and to brief statements—“I’m Belgian, I’m from Belgium, I’m Belgian”. It’s that simple. The transformed Henry Purcell music (mostly from The Fairy Queen) is played by the ten accordionists from the Conservatoire in Antwerp, the soprano sings, the dancers dance. They all might die, they all might kill. It’s about (if ‘about’ is a fair word) circulating desire (for love and sex). Marguerite Duras wrote of this fierce, sly, worn currency. She also wrote of the gaps within desire and body: “Sometimes they look a hundred years old, as if they’d forgotten how to live, how to play, how to laugh…They weep quietly. They don’t say what it is they’re crying for. Not a word. They say it’s nothing, it’ll pass”. (Summer Rain)

I saw La Tristeza after the opening of the Adelaide Biennial, All this and Heaven too (at the Art Gallery of SA), and before watching the spectacle of Flamma Flamma (at Elder Park). That is, I saw the strong epic black and white texts of Robert MacPherson and the quiet domestic solitude of Anne Ooms’ chairs, lights, and books, and then listened to a Requiem (Nicholas Lens’ Flamma Flamma), and watched the hundreds of children carry their glowing lanterns, and embrace the river-lake, and inbetween witnessed people brutalise and comfort each other. It was like being burned by flames of every intensity, and squeezed to life.

La Tristeza Complice, Les Ballets C de la B and Het Musiek Lod, Playhouse, February 27, Adelaide Festival 1998

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 4

© Linda Marie Walker; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

This is a strange experience; not weird, not wild, but odd. The odd opportunity to see one video several times and to read it differently (or not) each time because its soundtrack changes, each video voiced in a new way. I say voice, because voice, sung and spoken, is pivotal in this performance. Onstage three female singers, sometimes four, synch into spare soundtracks, adding to instrumental and/or vocal lines, or going it on their impressive own. As a music concert it’s mostly great, and gets better as it goes.

Often we don’t ‘hear’ soundtracks (even when moved by them), unless they’re as obtuse as the Titanic’s or packed with favorite tunes, unless we’re soundtrack addicts. In Voice Jam & Videotape image and music are almost in equal partnership. “Almost” because it’s the films in this performance which are repeated, not the musical compositions. Each video enjoys the benefit of two or three accompaniments. Although this is a Contemporary Music Events’ gig, it’s still a matter of music servicing the videos. (CME has produced a show where you sit in a cinema and listen to music without film.) Kosky tries to keep the balance by placing his singers next to the screen. By the last screening, I know what I’m inclined to look at.

Tyrone Landau, Rae Marcellino, Elena Kats-Chernin and Deborah Conway have created compositions that warrant multiple hearings. This could not be said of the viewing of most of the videos. Elena Kats-Chernin’s score for Judy Horacek’s animated The Thinkers, about The Stolen Children, was exemplary, matching this artist’s whimsical style with a musical cartoon language just serious enough to sustain the message. It markedly improved my still limited appreciation of the video, amplifying its moments of magic—especially the images of flight. David Bridie’s score for the same video, including the voice of Paul Keating, while politically pertinent, laboured the point, making the cartoon curiously twee, not up to the weight of the soundtrack. Deborah Conway’s composition for Lawrence Johnston’s Night, a Sydney Opera House reverie built from close ups of roof-shell details (tiles, edges etc.), added an aural density and a sense of the architectural space dealt with—many voices inside the Opera House, spare visual detail on the outside. Conway appeared (discreetly in the dark) adding her own voice to the multitude, the musical quality not dissimilar from that she helped create in the marvellous soundtrack for Peter Greenaway’s Prospero’s Books.

The one video that worked for me and that worked at me with the help of its composers, was Donna Swann’s dis-family-function. I’m usually not fond of narrative short films, but the almost silent movie, family-movie innocence of the work with its blunt edits and nervy close-ups (and none of these over-played), is engaging and I was more than happy to watch it twice. A gathering for a birthday party for an ageing mother starts from several points until the characters converge for a backyard party and the giving of gifts. Landau’s reading is relatively dark, male voice and piano, other male voices added, finally joined by the live voices of the onstage women singers. There’s something faintly disturbing about the score, a kind of restrained (almost Brittenish) poignancy, an inevitable unravelling of feeling and never a literal response. The onscreen image of the mother sinking into herself after the giving of gifts (dog bookends, dog statue, dog pictures, a real new dog—in the presence of her elderly-barely-willing-to-budge old dog) is sad. Rae Marcellino’s score is just as good, but much closer to what I imagine the videomaker might have had in mind. Its opening, rapid lines of “ma ma ma” immediately signals a lighter, everyday mood, and you don’t go looking for the video’s simple seriousness, that just hits you later. But in the choral work, as in the Landau, there’s something oddly holy generated as we watch these strangers—the mother, the dog, the son with his Indian girlfriend, the gay couple, and the young parents with baby, lolling in the sunlight, the near-but-never-to-be drama past.

Voice Jam & Videotape, curated by Barrie Kosky for Contemporary Music Events, Mercury Theatre, Adelaide, March 6 – 8; Salvation Army Temple, Melbourne, March 13 – 15

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 46

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ex Machina, The Seven Streams of the River Ota

One moment you’re immersed in festival fever: running projects, racing to shows and exhibitions, talking about stuff in foyers and forums, grabbing inedible food at disgusting hours of the day and night and still getting to work on time in the mornings. Suddenly, the festival(s) recede, leaving you fishlike, stranded and gasping, over-tired and frumpy in a world full of incessant deadlines and all the things that have been left undone that should have been done last week.

I began the Festival of Perth with the light and fluffy Titanic and the now hotly debated (over two cities and two festivals) The Seven Streams of the River Ota by Robert Lepage’s Ex Machina. Seven Streams was an interesting work. The seven hours of viewing were not arduous. In fact the no doubt necessary pacing/tempo made it very easy to sit through. Without going into descriptive detail (of which much abounds), I found the first three sections visually exciting, witty and incisive. It seemed, nonetheless, a fragile work, easily thrown off its stride. I started to have misgivings in the fourth section or stream, which represented the legal suicide of one of the key characters who has contracted AIDS; misgivings that turned to irritation in the fifth section, dealing with the Holocaust—lots of tricks with mirrors and the familiar images of a displaced population struggling through a non-specific but clearly European winter landscape.

Given the number of works in both the Adelaide and Perth festivals, that have attempted to deal with humanly inspired catastrophe, including exhibitions such as Jenny Holzer’s Lustmord (Bosnia) and Adrian Jones’ Cadaver (the genocide committed against Aboriginal people) at PICA, as well as a range of talks addressing everything from terror and morals in Perth and the sacred and the profane in Adelaide, the questions I am left with have everything to do with the possibility of the appropriate ‘staging’ and/or ‘exhibition’ of grief or despair in the face of overwhelming brutality. Finally it is the considered and subtle collaboration between Adrian Jones (WA) and Marian Pastor Roces (Philippines) which has been the most compelling in terms of a thoughtful self reflexivity in relation to these complex terrains.

In Seven Streams, my initial discomfort turned to dislike in the final three sections. What had previously seemed to be the deft touch of the director carefully avoiding the pitfalls of easy resolution, became simply glib; the politics naive and the visuals clichéd. The relationships articulated across the 20th century between the survivors of the Holocaust and those of Hiroshima seemed contrived and twee and something more (or less) to do with innocent (albeit gauche) America and ravaged Japan—an all too familiar trope.

Being the Festival of the long night, I also spent five hours watching Cloudstreet, presented by Black Swan Theatre in association with Belvoir’s Company B at the Endeavour Boat Shed in Fremantle. A beautiful space with a fabulous cast assembled by Neil Armfield, this was the absolute crowd-stopper of the Festival. Whilst I think it could well do with some judicious editing, particularly in the first and third sections and the little girlie stuff is a bit ham for my taste, this was a work defined by outstanding performances. Having said that, Cloudstreet is a relatively easy show, dealing with the familiar and the happily parochial—designed for an enjoyable night in the theatre. My enjoyment was somewhat hampered by the fact that, seated as I was, towards the back of a very large and steep rake, it was very hard to hear this very verbal piece much of the time.

There’s not much to be said about Germany’s Theatre Titanick. A mildly entertaining bit of fluff which is perhaps more interesting to look at in relation to Stalker’s Blood Vessel in Adelaide. A more embryonic work, Blood Vessel has so much more going for it in terms of a beautiful rig (designed by Andrew Carter), the sound (Paul Charlier) and the substance (Rachael Swain and the company). Whilst Blood Vessel has a long way to go in terms of both its content and its choreography, and the relationship between its strong visuals (physical and filmic) and material base, previous experience suggests that it will be a much more exciting work than Titanic by the time it reaches Perth audiences in 1999.

My pleasure in Uttarpriyadarshi (The Final Beatitude) by the Chorus Repertory Theatre from Imphal (India) came from the fabulous cacophony of image, sound and story telling derived from a rich synthesis between traditional Indian styles in juxtaposition with contemporary techniques. An elephant, richly caparisoned for war, creates a dramatic and fabulous moment surrounded by the shadowy silhouettes suggestive of great armies. Women wail in varying extraordinarily pitched registers or cackle like banshees whilst the fires of Hell burn. Buddhist monks perform something akin to the antics of the Keystone Cops and unlike Lepage’s much cooler Seven Streams, there is no sense of embarrassment or measure.

I didn’t make it through the entire program of the Lyon Opera Ballet. The first offering, Central Figure by Susan Marshall, took a quite formal dance vocabulary and made it into something simultaneously dull and sentimental. The second, Contrastes by Maguy Marin, relied on parody and caricature and was positively offensive. I was grateful to catch up with Teshigawara’s I Was Real—Documents in Adelaide and in this much more considered and technically meticulous work, get the artificial taste of saccharine out of my mouth.

Les Ballets C. de la B. and Het Muziek Lod, La Tristeza Complice

photo Chris Van der Burght

Les Ballets C. de la B. and Het Muziek Lod, La Tristeza Complice

The absolute highlight of the Festival of Perth was the Belgian (Flemish really) company Les Ballets C. de la B. and Het Muziek Lod with La Tristeza Complice directed by Alain Platel. Interestingly enough, audiences in Adelaide responded with infinitely more enthusiasm than those in Perth. This is a work that took on all my pet theatrical phobias (performers doing ‘mad’ and/or ‘street people’ is a particular hate) and hung ’em out to dry. In this landscape, people unfolded and retreated, hung out and persevered, danced into stillness; inhabited the space against the extraordinary sound of ten piano accordionists performing the Baroque music of the English composer, Henry Purcell. This is a work for experiencing not describing but the relationship between the performers (whether professional or inexperienced) was exceptional and their ability to focus on the vulnerable, the imperfect and the ugly, made it a performance of extraordinary beauty and tension.

Cloudstreet, Black Swan Theatre/Company B Belvoir, The Endeavour Boatshed, director Neil Armfield; Uttarpriyadarshi, Chorus Repertory Theatre Imphal, written and directed by Ratan Thiyam, Winthrop Hall; The Seven Streams of the River Ota, Ex Machina Company, directed by Robert Lepage, Challenge Stadium; Titanic, Theater Titanick, The Esplanade; Central Figure, Lyon Opera Ballet, director Yorgos Loukos, choreographer, Susan Marshall, Contrastes, choreographer, Maguy Marin, His Majesty’s Theatre; La Tristeza Complice, Les Ballet C. de la B., director Alain Platel, music by Het Muziek Lod, Regal Theatre; Cadaver, Adrian Jones, PICA. All events part of the Festival of Perth, February 13 – March 8

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 10

© Sarah Miller; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

A sizeable fold gathered at the very smart (or ‘bourgy’, depending on your perspective) Ngapartji Multimedia Centre in East End Rundle Street for FOLDBACK, the day long forum exploring media, sound and screen cultures, organised for the festival by ANAT (the Australian Network for Art and Technology). Richard Grayson gave a user-friendly welcome invoking the the 10th anniversary of the other summer of love—“the famous event in south-east England, where techno ecstatics transformed the urban psyche of hyper-decay and escalating pan-capitalism into trance and psychedelic experiences” (ANAT newsletter)—stirring our barely repressed British memories of driving minis through Essex out of our gourds, on the lookout for parties we could never find. Paul Brown who says he actually found the party, stirred some of the same nostalgia in his account of the slow emergence of multiple media practice as 30 years on the fringe, citing rampant conservatism behind the form’s status in the artworld as part of a global salon des réfuse. There was some sense in this hankering that “legitimacy” meant legitimacy in the visual arts world which suggested perhaps a narrower engagement with the arts than expected. This was happily contradicted in subsequent sessions that demonstrated the vital relationships between new technologies and writing, sound and performance. A very writing-based day all round.

Cyberwriter Mark Amerika re-traced his steps from underground artworld, performing “acts of voluntary simplicity”, through his swerve into publication with the cult hit The Kafka Chronicles, which hurled him unwittingly into the public sphere and onto the digital overground. While he was busy collapsing the distance between author and reader, his online publication network, AltX (www.altx.com) was attracting the attention of international money marketeers. Like a lot of the international guests at the Adelaide Festival, Mark Amerika seems to be able to pat his head and rub his tummy at the same time. He may have achieved some fame and a little fortune as web publisher, but he’s still addressing the frictions between electronic art and writing. His writing-machine (Grammatron) still grapples with spirituality in the electronic age, asking questions like “Who are I this time?” (www.grammatron.com).

ANAT’s first executive officer, cyber-artist Francesca da Rimini, took some of her own advice (Quick! Question everything) rudely interrupting her own spoken text with others emanating from her cyber pseudonyms gash girl, doll yoko and gender-fuck-me-baby.

In *water always writes in *plural Linda Marie Walker and Teri Hoskin, from the Electronic Writing Research Ensemble, linked up live with Josephine Wilson (WA) and Linda Carroli (QLD) who have all been part of the first joint ANAT/EWRE virtual residency project, writing together online to create a work entitled A woman/stands on a street corner/waiting/for a stranger. Duplicating the act of writing for a live audience was an interesting if slow process, producing some nice accidents of speech: the odd poetry of phonetic translations, the Simple Text voices reproducing typos; suggestive intervals between writing and spoken text. You can read the piece on http://www.va.com.au/ensemble/water

Programming Linda Dement after lunch was a brave move. Still, it was soothing to hear a female voice in the dark still in love with the possibilities of technology for realising her expert if sometimes gruesome images. You would expect a sustained sequence of bloody bandages accompanying a diatribe on censorship to empty a room but here the pleasure of seeing the work of this former fine-art photographer projected on such a scale and in such vivid detail held too much fascination. Me, I spent a lot of time looking at the floor. Afterwards, diatribe met diatribe when a man in the crowd accused Linda Dement of male-bashing, citing “the situation in Bosnia” and then “all of history” as reason enough to censor, presumably, any statements along gender lines.

No wonder the cheery Komninos Zervos with his Underground Cyberpoetry received such a warm response after this error type-1. His CD-ROM was produced while Komninos was ANAT’s artist in residence at Artec (UK) last year. Using performance-poet delivery and adopting an assortment of streetwise London personae, Komninos playfully navigated his word animations. Screen became spin dryer, words tumbling as Komninos moved among us. The performance potential of multimedia works is really only beginning to be explored in Australia. Outside groups like skadada in Perth and Company in Space in Melbourne, we don’t see a lot of performance engagement with the new media. It’s an area that ANAT clearly see as important.

nervous_objects is an eclectic, accidental experiment in internet artistic collaboration. They met at ANAT’s 1997 Summer School in Hobart and have continued to collaborate online, in locations as remote as Perth, Woopen Creek and New York City exploring notions of realtime internet conferencing and manipulation of artistic pursuits in virtual and physical space. In their first project Lingua Elettrica (http://no.va.com.au) at Artpace and created for ISEA 97, they built an interactive website and publicly destroyed it. In a day otherwise free of technological accidents, nervous_objects encountered a few, making it sometimes difficult to decipher their precise intention. Their calm in the face of calamity produced a laid back form of subversion.

The stakes lifted when Stevie Wishart entered. Not an Adelaide Festival accordion in sight but improvising with medieval hurdy gurdy and live electronics she extracted an amazing array of sounds and tones. Real Audio was streamed from Sydney and mixed as it came through. As Stevie played, Jim Denley navigated the new CD-ROM track created with Kate Richards from Stevie’s new CD (Red Iris, Sinfonye, Glossa Nouvelle Vision GCD 920701).

In the energetic Q and A session, Mark Amerika brought up the need for new writing about multiple media, citing the likes of George Landau and Gregory Ulmer as critics who practice what they preach and engage with the work on its own terms. Chair of the New Media Arts Fund, John Rimmer, asked just how much technical difficulties (lags, delays, congestion) are intrinsic to the work and how they might develop given more bandwith. For nervous_objects, if it gets too fast, too polished it’s not interesting anyway. There was some discussion of Garry Bradbury’s score for Burn Sonata using pianola and digital technology. When someone in the audience thanked nervous_objects for sharing their process. Garry begged to differ, accusing them of utopian dreams of machines generating ideas. The nervous_objects said it was something that pushed them and they certainly didn’t expect the machines to generate ideas. Working with content issues was what they were doing. Afterwards all repaired to the Rhino Room for the launch of the excellent new CD by Zónar Recordings, Dis_locations, Incestuous Electronic Remixing, coordinated by Brendan Palmer. RT

FOLDBACK, ANAT, Adelaide Festival, Ngapartji Multimedia Centre, March 8.

An accompanying exhibition, possibly to tour, was exhibited at Ngapartji for the duration of the Adelaide Festival’s Artists Week. http://www.anat.org.au/foldback

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 27

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Sound Mapping, Hobart Wharves

photo Simon Cuthbert

Sound Mapping, Hobart Wharves

Sound Mapping is a participatory work of sound art made specifically for the Sullivan’s Cove district of Hobart in collaboration with the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. Participants wheel four movement-sensitive, sound-producing suitcases around the district to realise a composition which spans space as well as time. The suitcases play “music” in response to the geographical location and movements of participants.