Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Ironically, in a festival exploring the permutations of distance, 1998’s Next Wave Festival demonstrated the promiscuous intermingling of artforms and the dissolution of traditional barriers between them. With a program comprising more than 100 separate events, Next Wave abandoned discrete artform streams in favour of a recognition of the increasingly hybrid and cross-disciplinary nature of contemporary art practice.

Next Wave’s art and technology program has consistently provided one of the highlights of the festival, generating high levels of publicity and pulling punters eager to take advantage of the opportunity to actually see new media art for themselves. Though tempting it would be a mistake to see this year’s refusal to replay the artworld apartheid scenario as a symptom of the increasing acceptance of new media into the mainstream contemporary arts world. Most galleries pay the barest of lip service to supporting this and other many new artforms. Perhaps now that most art schools have glossy new multi/new media courses which are already pumping out the graduates, these galleries will be forced to rethink their attitudes and begin to present technologically demanding works as a consistent part of their normal programming.

More pragmatically, the integration meant that one tended to stumble over projects incorporating new media. Equally, given the geographical dispersion of Next Wave events with many in rural Victoria as well as in diverse parts of Melbourne and suburbs, the car-less viewer certainly felt the tyranny of Australian distances. Most of the actual projects, though, concentrated on psychological and emotional distance, producing a strangely melancholic and nostalgic undercurrent as they explored human yearning for closeness and understanding and the impossibility of achieving it.

Company In Space’s futuristic installation I@here, You@there (email order bride) at Gallery 101, all shiny stainless steel and glass surfaces, assorted techno-gadgetry and lonely reminders of the natural world, was pressed into dual service for a 3-up performance in which there was plenty of technology-mediated looking but minimal contact as the participants remained trapped reflections of each other in a masturbatory pas de deux. I@here, You@there (email order bride) contained moments of great poignancy and beauty but was flawed by the logic of the installation layout which at times transformed the performers into product demonstrators showing off the features of one gadget after another. (See also, “I@Here, You@There”, RealTime 25, page 14)

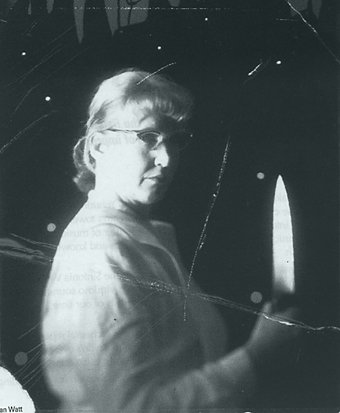

In his elegant minimalist installation self remembering—home in the vaults at Old Treasury (one of the most beautiful and challenging indoor installation spaces in Melbourne) James Verdon exposed his ‘self’ and the audience in a series of mnemonic loci of sexy surveillance gear, soft-focus video and multilayered digital images dispersed within the chilly shadows of bluestone vaults originally intended to protect the monetary assets (and secrets) of a young colonial administration. Exploring questions of subjectivity and surveillance, the work generated a sexual subtext of voyeurism and exhibitionism as viewers spied on each other, swapping gossip—secure in the knowledge that the gossiped about were safely ensconced in another cell—and puzzled out the narrative clues of a self, rendered partial and out of focus by the passage of time and the vagaries of memory. Memory, the private construction of the self through self-surveillance and re-presentation of the past became equated with the social and economic forces, deploying an ever greater range of surreptitious monitoring technologies, which enforce appropriate public self-presentation—identity as a product of context.

@ curated by Kate Shaw was a welcome revisiting of the terrain of video art—which was, as you will remember, going to be the next big thing in the early 80s, but withered through lack of exhibition and critical support. @ firmly positioned video art as a subset of visual art—none of that annoying investment of time of which Robyn McKenzie so vociferously complained at the Binary Code Conference was inconsiderately demanded by interactive media therefore preventing it from being considered an artform. Nosirree. @’s works (by David Noonan, Meri Blazevski and Leslie Eastman) paid out fast, evoking the alienation endemic to a fast-moving society fragmented by physical and social mobility at the very moment that physical space is being collapsed by global telecommunications. All movement (whether it was Noonan’s re-visiting of the roadmovie, Blazevski’s elegiac elevator loop or Eastman’s movement of light from across the world via video-conferencing to illuminate the corners of 200 Gertrude Street), but no destination. It seems all roads, URL or virtual, lead nowhere—but the scenery is very pretty and reason enough to start the journey.

Map 1, Garth Paine’s most recent investigation of immersive interactivity, eschewed the more common privileging of the visual in favour of encouraging the audience to construct their own cartographies of aural space. Activating the installation’s responses by their movement through it, Map 1 immersed the audience in a rich sonic field which encouraged communication as individuals collaborated to map the area and then ‘play’ it like an instrument. Rather than represent distance symbolically, Paine’s work both activates and collapses space—breaking down the polite ‘look but don’t touch’ of most art work by only springing into full existence when physically triggered by a corporeal presence traversing its parameters, and by encouraging and rewarding communication between the participants. As such, Paine’s work foregoes involvement in continuing assessments of the capacity of technologies to perpetuate existing and create new regimes of social control. Instead it offers an optimistic technophiliac vision of a more humane technology which will allow new insights into our world and new ways to express them.

I@here, You@there (email order bride), Company in Space, Gallery 101, May 1 – 28; Map 1, artist Gary Paine, SPAN Galleries Melbourne, May 5 – 23; self remembering – home, artist James Verdon, Gold Vaults, Old Treasury Melbourne, May 1 – 31; @, curated by Kate Shaw, artists Meri Blazevski, Leslie Eastman, David Noonan, 200 Gertrude St Fitzroy, May 8 – 30

RealTime issue #26 Aug-Sept 1998 pg. 6-7

© Shiralee Saul; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

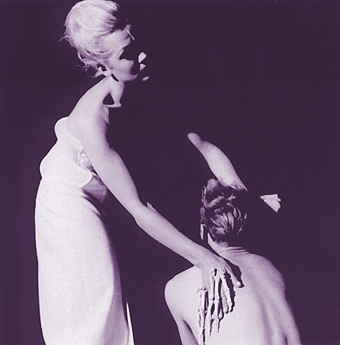

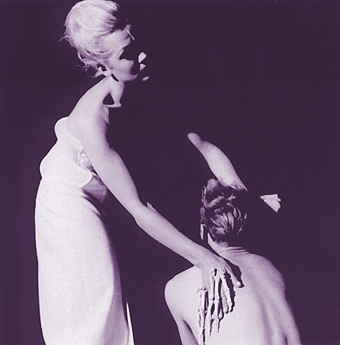

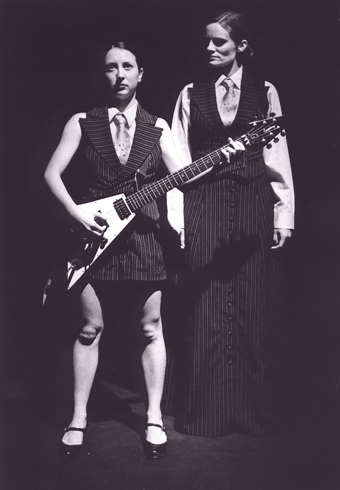

Kate Denborough and Gerard Van Dyck in Contamination

Although Melbourne’s Next Wave festival is for emerging artists, not all its performers are all that young or, for that matter, emerging. Contamination was a case in point. Produced by Kage Theatre (Kate Denborough and Gerard Van Dyck), elements of this piece had sophistication and polish. Firstly, the design of the space: the theme was white. White costumes, white walls, white light—the lighting beautifully enacted by Ben Cobham whose work I admire. This time, he erected a wall of white plastic road barriers stage left, and gave them a warm, cream glow. Secondly, in a flash of surreal inspiration, Denborough and Van Dyck had their fathers appear in a back room, dressed in cream lounge suits, play chess, read the papers, and offer the odd comment over the length of the piece. Thirdly, the opening: three performers (Denborough, Van Dyck and Shona Erskine, all highly competent) enter and hang themselves upside down from three meat hooks, twisting and twining with a refined beauty. A hard act to follow but follow it they did, with a series of short pieces consisting of dance, talk, and comedy.

Some of the pieces were lovely, some funny, some not. There was some fine material in the movement. Denborough and Van Dyck are obviously very comfortable with each other and all three performed some entrancing sections. At times, Erskine looked a bit excluded from the action of the piece. Her presence was not as luminous as it usually is, and I think this was because the choreography was largely composed by the Kage duo. I’m not sure whether her contribution was fully thought through. Although she performed a strong solo towards the end of the piece, she was also latterly relegated to the side of the space. Also, the comedy skits were largely between the other two who obviously have the theatre skills and enjoy bouncing off each other.

There were some genuinely funny moments, such as the intervention of Van Dyck’s mobile phone, the appearance of the two older men, preparations for some Afro-Funk groove, and a Meatloaf impersonation to the repetitions of a drum machine (the music was skilfully created and managed by Garth Skinner). Other cameos were not to my taste, dependent as they were upon our laughing at ungainly representations of suburban, working class people.

Contamination was a rich work, with vivid moments and kinetic finesse. Structurally, I don’t know what the whole piece was ‘about’ but I’m not sure that matters. Within the hour or so of performance, there were many interactions and actions which demanded a committed attention, and offered aesthetic pleasures. If anything, I would have preferred to see some of its shorter moments developed into longer considerations.

Damien Hinds, Viviana Sacchero, Helen Grogan, Fiona McGrath, Elise Peart, Emma Fitzsimons and Zoe Scoglio in Distance, Be Your Best

Whereas Contamination was not a work of emerging but emerged practitioners, Distance, Be Your Best was jam-packed with young artists with a horizon of future work. A collaboration between Danceworks (director Sandra Parker) and Stompin Youth Dance Company (director Jerril Rechter), Distance brought together two groups of young people from the two sides of the Bass Strait. Indeed, the slowly modulated video shown on the back wall had its dancers tread both beaches of this rough and stormy expanse.

The work began with the two groups of dancers at opposite ends of a very big concrete hall. Slowly, slowly, they worked towards each other, in time, weaving, threading, assimilating and finally, separating. Clothed in silver, red and grey, these vibrant movers performed for well over an hour. Their movements simple, dancerly and well-executed, they looked comfortable in themselves and with each other.

One of the themes was isolation, both urban and semi-rural. The choreography was such that a rich texture of singular but linked movement was established and maintained, conveying a sense of autonomy (many bodies working independently). Towards the latter half of the piece, a series of duets transpired…washing in and out like the sea. Up the back, two women danced solos (or was it a duet?) in front of video projections. And predictably, the two groups finally regained their distinct identities. If this was a work about isolation and distance (certainly its conditions of production bespeak geographic separation), then its participants did not look the worse for it. There is something refreshing about seeing a lot of young people perform with integrity and vigour. Perhaps it has to do with the constructive effects of a collaborative project—one that ultimately defeats the alienation and isolation that formed the initiating theme of the piece.

Contamination, Kage Physical Theatre, Karyn Lovegrove Gallery, May 22 – 31; Distance, Be Your Best, Danceworks and Stompin Youth Dance Company, VCA School of Art, The Unallocated Space, May 2

RealTime issue #26 Aug-Sept 1998 pg. 8

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Dear Reader,

Please note: I have just re-read the finished letter and decided to use the convention of underlining words to suggest hypertextual links. Rather than reading the line beneath the word as an authoritarian marker of emphasis, as if words were bound to the page like black flies on white flypaper, the reader is encouraged to interact imaginatively with the potentialities of the text (do a little cerebral hypertextual flea-hopping (See “Notes on Mutopia”). This is just a suggestion.

“It is deathly still in the room—the one sound is the pen scratching across the paper—for I love to think by writing, given that the machine that could imprint our thoughts into some material without their being spoken or written has yet to be invented. In front of me is an inkwell in which I can drown the sorrows of my black heart, a pair of scissors to accustom me to the idea of slitting my throat, manuscripts with which I can wipe myself, and a chamber pot.”

Nietzsche, Fragment of 1862

(quoted from Kittler by Tabbi, in Modern Fiction Studies, Vol 43, number 3, Fall 1997)

On The Letters K and Q

Sometimes there is a queue in our house to use the computer. I like this image of a bold Q forming, like a shallow pool, outside the room with the computer, with me standing anxiously by. I am aware that two persons maketh not a queue. I am also aware that the use of the possessive ‘our’ is misplaced, since we do not, at the time of writing, own our own home, although we would like to. At the time of writing we do not even own our own computers (plural). Please note that interest in and enthusiasm for the net are no guarantee of computer access and/or ownership (singular). The fact that we want to own our own computers—one each, mine and yours, or else it’s over, and I’m taking the car— leads to my first conclusion: here, in what used to be called the Domestic Sphere but which now, surely, after it has had innumerable holes punched in it by penetrations of market, media, man, ought to be renamed the Domestic Sieve; here at least we are still in the Kingdom of the first person possessive pronoun, no matter what the PDH (Partie Democratique Hypertexte) tell us.

But I digress.

Re: The Uses of the Q. I’m sorry. I apologise. I have exaggerated both the intensity with which we want to use the computer, and the associated protocol. We do not queue, as such. I went a little overboard, because in order to parade the badge of (partial/situated) knowledge, to lay claim to some right to write, I felt I must cite extreme feelings for the computer, that I must gesture towards addiction (see Ann Weinstone, “Welcome to the Pharmacy: Addiction, Transcendence and Virtual Reality”, diacritics, fall 1997). Of course, the Q also introduces a hint of domestic conflict into the picture— even, dare I say it—romantic/situational comedy. One man, one woman, one computer, one mouse, one cat…another story. I confess to playing the junkie card, mobilising the (to some) all too familiar scenario of the transcendental rush, the nightly habit of queuing in a dark corner, waiting to make a connection, scratching, itching to log on and get out of it. Intensity sells stories.

Outside the study, gazing into the glassy pool of the letter Q, I catch a glimpse of myself. At least it looks like me, and in this day and age that is enough. I sink into the curly embrace of the Q, wrap myself around myself, and take up my pen—a thin, black, felt-tipped pen. Most people, as they move inexorably towards middle age, develop a preference for one writing implement over another. They exercise their choice. Optimum Scriptive Technologies. Sitting there, alone, I write—Each adjective that qualifies this pen of mine—thin, black, etc—makes me think, My pen and me, we’re special. We are singular types with something singular to say. Just for fun I sign my name, over and over, reducing my irreducibility and singularity to pure iteration(!). And then I wake up and realise it is all nostalgia, that it is not me in the pool at all, and cross out what I have written. Unlike the screen and its blinking little cursor, the trace of what I have just un-wrote remains on the page. Interesting. Bored by waiting in the queue, I pick up an interview with Paul Auster. He has just sold some manuscripts to a Library. A man who specialises in mediating between Libraries seeking manuscripts and writers who might want to sell them, comes to visit Paul every day for several weeks, putting the drafts in order, checking that the words that have been crossed out can still be read, so that the future readers can see quite clearly where the writer has been even though he chose not to stay there. What a job, I think, not sure if I would want it or not. (“Excuse me Paul, is that a ‘t’ or a ‘b’ I’m seeing here? Is that ‘hat’ or ‘had’?”)

What happens to the idea of the manuscript now? Should we be worried, I ask a representative of the PDH? Ought we all to be saving and printing our drafts as we go, just in case that little man from the Library should one day call? Is this a paradigm shift? Is this the future? Is there money to be made in places we nearly went?

My emails are re-routed. The server is down. Or something like that.

Some say it all started with the typewriter. I believe the Heideggerians began this fingerpointing, but I am not sure. It was the typewriter that directed written language away from the body, the hand, away from the ME! ME! to the reproducible discretion of the SHE/HE, left to tap away peripatetically under artificial light, like neurotic battery hens. Around this time, some say, writing became a terrifying prospect. Kafka felt it, (and hence the letter K). Nietzsche felt it before him. Eventually all the big guys got it bad.

(I realised the other day that I wanted to buy a typewriter. ‘Why?’ was the incredulous response. Who ever thought we’d get nostalgic about typewriters? Remember the old IBM Golfball? The speedy Kthunk. Sigh.)

At last it is my turn. I sit down and study the illuminated square in front of me, thinking about all those monks who worked on the first letters of manuscripts. I think about solitude. About writing. About reading. Turning back the pages, I think about the time that it used to be just me, my book and my (moving left to right from age 7 to the present) banana, cold milk, chocolate, coffee, cigarette, chocolate, tea, chocolate, and finally, herbal tea. I have renounced the lot. But have I renounced the intimate relation of the body with reading, writing, and thinking? Am I finally, once and for all, a severed head? (Of course, all this giving up and renunciation are merely a rhetorical ploy, the flip side of my addiction-simulation above). My mother is worried. My eyes, RSI, radons, microns, veiled dangers emanating from behind the screen. Don’t worry, I tell her, reaching for a raw carrot. It gives me something to do with my hands. I hold the little mouse tight. I click. It is a voyage of sorts.

Textual islands rise up here and there, archipelagos of quotations, aphorisms, fragments, and we sail from one to the other, trying to connect the dots, to get something sweet to eat, to make love in the shade. That is what I am doing here and now; hopping from island to island, lily-pad to lily-pad, oasis to oasis, enclave to enclave. I am anachronistic, but what counts is, I am quick.

Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, “Notes on Mutopia” (Postmodern Culture 8:1 http://muse.jhu.edu.journals/post [expired]…but only if a university near you subscribes, I believe.)

I read on. “What matters now is not the straightness and purity of connection, but how many things something can be connected to.” Questions linger. Is the ideal world one in which everything is connected? Is this choice? Or the definition of paranoia? Remember the military-industrial-psycho-medico-multinational-corporate-arts-complex? Is this what we want? Is this what we are getting? Why are all the articles I read online from East Coast American Universities?

I keep my mouth shut while the battles are replayed on the listserv. The Prophets of Doom vs the Angels of Rapture. Mea culpa, I say, one hand on the mouse, the other on the cat, I am just a beginner. I feel like a sneak, a voyeur. I recognise in my inordinate fear of exposure the working of power.

I worry that the PDH has weakened their case, fetishised the footstep in the sand, instead of worrying a little bit more about whose boot was on whose foot. And what about this Hypertext Aesthetic? How come hypertext seems to be the realisation of every theoretical dream of poststructuralism, postmodernism, deconstruction, and now even post-colonialism (see Jaishree K. Odin, “The Edge of Difference: Negotiations between the Hypertextual and the Postcolonial”, Modern Fiction Studies Vol. 43, No. 3 Fall 98). How can it be democratic, reader-driven and avant-garde as well? Have I overlooked something?

Outside, the queue is getting longer. The crowd is getting restless. I look forward to your response and could you hurry, please. People are waiting.

Sincerely,

Josephine Wilson

RealTime issue #26 Aug-Sept 1998 pg. 22

© Josephine Wilson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

www.temporalimage.com/beehive

http://www.temporalimage.com/beehive.index.html [expired]

Capital S style and capital C content, full of puns and buzzing with arcHives of fiction and critical theory, beeHive is a recent ezine aiming to “advance hypertext media”. The 2nd issue features Queen Bees and the Hum of the Hive, an analysis of subversive feminist hypertext, and The Red Spider and Razorburn, two short stories lacking bite and edge, about the banality of everyday life with your lover. Fiction this short (under 1200 words) can’t afford to be lifeless; every word has to count. Volume 1 includes Steven Shapiro’s theoretical fiction Doom Patrols, an anticlockwise patience game of wounds, flesh and Kathy Acker. To play you need a java capable browser.

http://www.gangan.com

gangway online mag has poetry, short stories and “experimental prose” from Australia and Austria with a sprinkle of Germany and Scotland. Useful if you’re multilingual, which I’m not, so I probably missed the best bits. I couldn’t find anything that resembled experiment in the latest issue but it may have been hiding in German. I was more attracted to the fiction that I couldn’t read—1 manuskript and Destruktion (followed by greek alpha thingamyjig which I can’t find in my insert symbol menu) sound more gripping than A Little Knowledge… or Requiem. A Lucky Dip. There’s duds—watch out for poems about waves in Bondi ALL IN CAPITAL LETTERS—but it only costs 25 cents and hopefully you’ll draw out Andrew Aitken:

Venus the Harlem tennis-babe smiled

at the interviewer on Sports Sunday.

‘My biggest weapon’s not

my serve, but Dad’s AK 47!’

http://www.ryman-novel.com/

253 or Tube Theatre. An internet novel set on the London underground. 7 carriages, 36 seats = 252 passengers plus one driver, hence the title. Number of words for each passenger = 253. The guy who created this site is either crazy or a Virgo. Every character on the journey is described: outward appearance, inward appearance, what they are doing/thinking. A ptg myself—public transport grrrl—I do this every day in my own imagination anyway. Meet Mr Donald Varda who is re-imagining the ending to An American Werewolf in London or Ms Sabrina Foster who advertises in the personal column as a black woman (she soon regrets it…because she isn’t one). Hypertext is used minimally but to good effect, co-workers linked, stories intertwined, the sense of order works well and sly humour, political barbs and intertextuality mean addiction for pop culture junkies. It’s also an inclusive project, an intermingling of cultures (you wouldn’t want a train carriage of Hansonites but then again…the train does crash in the end). Right behind, there’s another train coming, stalled, full of passengers just waiting for a persona…

RealTime issue #26 Aug-Sept 1998 pg. 21

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The fourth of the Australian Film Commission’s (almost) annual multimedia conferences, mounted in chilly Melbourne, was the cleverly phrased Being Connected—the Studio in the Networked Age, a label that managed to be interpreted through most of the 35 presentations in the assertive, hypothetical or simply descriptive senses.

The focus at the previous AFC conference, Multimedia Languages of Interactivity, had been on teamwork models from quite distinct production environments. The suggestion at Being Connected – the Studio in the Network Age, that producers were hyperlinking the production process was less convincingly projected. With so many more completed products and projects than earlier events to use for show and tell (multifarious websites being invaluable for this purpose), the tendency was to survey outcomes with little opportunity for formal interaction with the presenters, a shortcoming noted at previous events (seeking to amplify the interactive element within multimedia).

The notion of the integrated interactive production team, whilst not so strange to commercial producers, was less evidenced by the practitioners who composed the majority of the audience for this year’s event. Their informality was brought about, of course, by project-based budgets rather than the continuity experienced within the ‘virtual’ facility houses servicing Hollywood from London. Able to access extraordinary resources, it came as no surprise that whilst these companies were able to work in a wide-band virtual studio, the outcome seemed simply to improve their bottom line in relation to where they choose to live and work. Peter Webb’s demo reel of visual effects for Romeo+Juliet hypnotised us with so much digital manipulation and mentioned, almost in passing, the innovative ‘video fax’ ISDN network set-up linking Melbourne and the studio execs in LA.

John and Mark Lycette (‘The Lycette Bros’) described how they had collaborated using the humble email attachment back and forth between Melbourne and Vienna over a matter of hours to devise a prize-winning T-shirt design. Providing JPEG image attachments to ‘faceless’ clients in distant cities is now well practised—whiteboard websites to enable the clients to monitor a project’s progress via the web is standard.

“Technology changes at the speed of habits”, Clement Mok reassured us, as internet telesales boom in the USA. The corporate design guru and information architect suggested that we don’t need metaphors but relationships. “The net should improve the connections between families,” he said via the teleconference link from his Studio Archetype in the USA. (www.clementmok.com)

For the 3% of world-wide families who are able to link there is also Victoria Vesna’s recent investigations into how to build “a virtual community of people with no time”. OPS:MEME (Online Public Spaces: Multidisciplinary Explorations In Multiuser Environments) follows the celebrated Bodies Inc project and likewise delves deeply into online space. “The primary mechanism for facilitating this goal will be the design and implementation of the Information Personae (IPersonae), a combination search engine, personally generated and maintained database of retrievable multimedia links, tool kit for collaboratively manipulating information, and pre-programmed intelligent agent …” The project is in its initial stages anticipating forums such as Being Connected, but, given the kind of patents that may result, raises nonetheless the spectre of the virtual meritocracy.

One Tree, expat Australian Natalie Jeremijenko’s cloned trees for the San Francisco Bay Area, combines, in a meta-project metaphor, symbol and material presence, using a website that will record the life of each real tree, and a CD-ROM that will algorithmically reproduce a tree within a host computer. Here the geographical community and the community of interest are brought together by being connected with nature and into the biological virtual organism.

The AFC-funded ”enables good voice”, and will connect Indigenous people globally around land issues into a documentary form that, under the management of Jo Lane, will ‘live’ for the next two years. Writer and filmmaker Richard Frankland, a man from the Kilkurt Kilgar clan of the Gournditch-Mara nation in western Victoria, spoke eloquently about this opportunity for interaction to occur between all those who see the Land as the focus of our survival rather than our extinction, culturally “in many forms, not one generic form—generalisation is not an option.” (www.whoseland.com)

Hypermedia futures were intriguingly projected by the mercurial Andrew Pam, Technology Vice-President of Xanadu (Australia), the research group assembled by Ted Nelson, one of the definers of online media. As the world wide web begins to stretch at the seams under the incursion of non-standard mark-up and bundled browsers, Project Xanadu—as the ideological conscience of the World Wide Web Consortium—works to encourage standards whilst developing further enhancements and extensions of the phenomena: OSMIC, a versioning tool that will identify original sources; scalability standards to prevent fragmentation across different browsers; replacement of the URL with the URI (Identifier) such that a page can be located regardless of which server it sits on; and transpublishing, transcopyright and micropayments as a means of making media more freely available for minimal cost to the end user. (www.xanadu.com.au)

Hypertext achievements featured strongly. Katherine Phelps gave us a thorough “History of Digitally Based Storytelling”, 1960s to the present. Kathy Mueller, developing her work in interactive drama and game play (“the web will give us the opportunity of making better relationships.”) outlined a theoretical basis for online serials with which she is currently working. (www.glasswings.com.au/)

The more recently completed “…waiting for a stranger” is also the verbal metaphor for Perth writer Josephine Wilson’s “stumble from printed page to screen”, which in collaboration with Brisbane artist and writer Linda Carroli, was an online writing project hosted by ANAT, *water always writes in *plural. (http://va.com.au/ensemble)

Flightpaths: Writing Journeys, a meta-project involving CD-ROM, installation and radio was directed and described by berni m. janssen. Utilising the talents of many other writers who contributed via email from across the country to the process, a CD-ROM anthologised the outcomes.

Flightpaths was one of an impressive group of 13 recently completed CD-ROM projects which were exhibited in the conference foyer. Artists who spoke about their work included Michael Buckley. His The Good Cook integrated words and images as a poetic whole (the production was completed in Dublin town aftr’all), addressing the contemporary urban condition through the (hypermediated) loops and repetitions of the hopelessly insomniac cook. The city and its culture was explored by Sally Pryor in her multi-faceted CD-ROM Postcard from Tunis. Part travel diary and part language coach, Postcard … won the prestigious Gold Medal at the 97 NewMedia InVision Awards, and secured a French distributor.

Troy Innocent’s continuing adventures with artificial life systems delivers Iconica, which combines the multimedia capacity of the CD-ROM with the dynamic interconnectivity of the web, whereby the capacity of the software to evolve its Icons, Forms, Entities, Spaces and Language is extended through interaction with other evolving copies of the system loaded onto other computers also connected to the internet.

Such a metaphor (for the conference as a whole perhaps) produced a rare moment of humour as it became more difficult for the demonstrator to locate one of the ‘beings’ resident within Iconica: “No it’s not there…or there…ah there’s one, no it’s gone…” Observing artificial life, it seems, is to be as elusive and misleading as observing one’s neighbours through the curtains. Quite distinct from the observations made by the keynote speaker Darren Tofts on the issue of memory, the further we immerse ourselves in the networked world, the more technology is able to “remember it for you wholesale”, atrophying the oral tradition of knowing what you can recall. At this stage of the game, “are we ready for the evolutionary loss of the larynx?”

Australian Film Commission Conference, Being Connected: the Studio in the Networked Age, RMIT, Melbourne, July 9 – 11. Conference papers and artists’ and speakers’ URLs will be available for a limited time at: http://beingconnected.afc.gov.au/ [expired]

RealTime issue #26 Aug-Sept 1998 pg. 32

© Mike Leggett; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

What is subjectivity? That’s the issue. How does a physical, biological system like a human being come to have that personal, private but conscious experience of the world which is ultimately available only to oneself and expressible only through the most devious of means. Moreover, what is the self that is conscious of this experience?

These were the questions explored by the 800 or so people from many disciplines in philosophy, the social, biological and physical sciences, as well as computing applications and artificial intelligence, who came together for the Towards a Science of Consciousness III Conference. The range of contributions and possible answers run from complete denial of subjective experience through to the utterly mystical. Important new information about our neuro-biological processes and several new approaches to a quantum physical “mind field” explanation were presented but, ultimately, this edition of the biennial conference brought us no nearer to an explanation of conscious experience.

Great advances have been made in the biology of consciousness, or at least the biology of how we see and recognise objects, how we control our movements, how we interact with others and the emotional underlayer for everything we do. To mention just a few. A very good understanding of seeing, and how we interpret and recognise what we see, has been developed by Christof Koch (Germany/USA), built up from the work of many others. The neuronal processes employed for the detection of colour, edges and movement and the maintenance of object wholeness as we move (scan) our eyes across a scene are becoming well understood. The hierarchical relations of visual-feature-processing neural-assemblies in the cortex leads to concepts of how and where we recognise objects and people, how we separate out the information we need to physically grasp and manipulate an object, and most importantly, whence the visual information that we are conscious of derives.

Al Kazniak (USA) has elucidated much of the neural structures which mediate our emotional experience and the relations our desires and fears etc have to our behaviour. Our understanding of our social behaviour is also being shown to have neural basis. Vittorio Gallese (Italy) and colleagues have discovered in monkeys the visuo-motor “mirror” neurons by which they recognise and respond to the facial expressions of other monkeys. These neurons may serve as the basis for that recognition of the other, which forms the basis of communication and language.

Al Hobson (USA) has shown us a great deal about how dreaming enters our lives, what changes in the chemical modulation of our brains brings about sleep and dreaming and why dreams are so disjointed and bizarre. It’s proposed that dreams are what happens when, with the usual waking sensory input turned off, low-level bodily events and the day’s residuum within our emotional brain become input to the normal visual interpretation mechanisms without any of the regular awake control and discernment applied.

Bernard Baars and James Newman (USA) have mapped a highly suggestive description of the cognitive aspects of consciousness onto an architecture of control and processing assemblies operating between the cortical processing and lower brain attentional mechanisms. The cognitive description has become known as the global workspace. Its anatomical basis is in the inter-relational architecture of the cortex and the sensory relay station called the thalamus.

But all this biological knowledge does not resolve the issue of how it is that we have subjectivity. What is that intimate personal experience of the information flow through one’s brain that ‘I’, a ‘self’, experience? Is the biological process all that is going on, or is there some other thing occurring? This problem seems to arise from the fact that what I experience as first person process is so utterly different from the third person, physical description of the world. For example, what we report to each other about the ineffability of a glorious sunset simply hasn’t got the depth and intensity of the direct experience of that sunset. The green of the leaves may well match a Pantone colour chart but how can I tell you of its intensity when walking through a forest? (The nearest we seem to get is in the transmission of ideas through the range of the arts.)

And this is what is known as the “explanatory gap.” How can we explain the difference between my subjective experience of some phenomenon of the world and the physical explanation of that phenomenon, say in terms of wavelengths of light turning out to be some special colour. This was the major philosophical problem discussed at the conference. What is this explanatory gap? Is it real? And most importantly, if it is, how do we bridge it? This has become what David Chalmers (Australia/USA) describes as the “hard problem” for a science of consciousness. It is what produces some of the most outrageous proposals and makes the whole area so interesting. How do we get from one’s first person experience of something to the third person description of the experience? What gives the experience of a colour or a smell its intrinsic feel, its depth and intensity, its “qualia”? Given the neurobiological explanation of what is happening in my experience of a colour, why do I experience it at all?

Evidently, quantum physicists are having the most fun with these questions. As somebody noted during the conference, for every quantum physicist there is a different interpretation of the quantum physical world. Stuart Hameroff (USA) still holds to the idea that quantum collapse (the manifestation of a consciousness of something) occurs in the skeletal structure of the neural cell, and is still challenged to explain how this could occur in a system operating at biological temperatures. Fred Wolf asserts that there is a field of “mind” throughout the universe, that everything actually occurs within that field and that we simply tap into it for our dose of consciousness. This is the most theologically inclined suggestion and is perhaps the best hope for the mystical and transpersonal psychology types who speak of the ‘spirit’ being primary. But it still remains to ask how it is that any biological ‘I’ might have access to my personal part of this field?

The new quantum physics of information throws a fundamental spanner into the works for all sides of this argument because it introduces the notion of information itself, the differential relations between things, being even more fundamental than the particles discerned through the agency of those relations. This issue, and the detectability of the difference relations, is still being developed as a topic of consideration, though it has deep sources in the work of Kant and Bertrand Russell.

Transpersonal psychology and the mystical experience have the most to gain from the formulation of the explanatory gap and quantum physical explanation. Here the politics of the research start to become evident. Is the neurobiological work all that is necessary or is there something more that should be funded? For my part I think that the explanatory gap is actually a result of the struggle between theology and mechanistic explanation as clearly shown in the work of the 17th century philosopher Rene Descartes. If he hadn’t needed to show himself to be a being possessed of a soul as well as a ‘mechanical’ body then this subsequent confusion need not have arisen. Experience could have been shown for what it surely is: being inside the body’s processing of the informational product of the world, rather than the dualistic interpretation; namely, there is the physical and there is something else, which we find inexplicable.

Disappointingly, the possibilities inherent in the organised-systems nature of neurobiology and the possibilities of artificial intelligence as available through neural networks were left almost completely uncanvassed. As a result I think that the opportunities for a useful understanding of how a physical body produces consciousness were missed.

The problem boils down to this question: Does consciousness require a field of some sort to exist within? Or is the functioning of the biology enough to produce the qualia and subjective experience that defines consciousness? The quantum physicists and the mysterians all assure us that a “field” of some sort is necessary and those neurobiologists and cognitive psychologists who choose to deal with the notion of the qualia of experience suppose that the functioning of the brain is all that one needs. The purpose of most of the philosophers in the debate is to point up this issue: How do you explain the subjective feel/quality of our first person experience of the world. (Ignoring, for the present, the issue of what exactly the world is anyway?)

Towards a Science of Consciousness III Conference, University of Arizona, Tucson, April 27 – May 2

RealTime issue #26 Aug-Sept 1998 pg. 33

© Stephen Jones; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

It was the kid who showed us how it works.

The project—'exhibition’ is too inertly flat—is launched by Kevin Murray. He gives a long, slow and apposite speech, Murrayisms marching neatly out in squadrons of analytical metaphors that line up and do smart manoeuvres on the conceptual, discursive and cultural fields territorialised by A CONCEIT. He talks (off, through and around the exhibition program) about mapping, about ideas of, and, as space. Inevitably he retells that old Borges story of the one-to-one map, the positivist fantasy of the model meeting its referent in an exact fit.

Meanwhile there’s this kid (oh I don’t know…about nine, Enid Blyton-blond, blue sly-eyed, jerky and restless) standing at the kiosk computer in the centre of the (attentive) audience. Unlike the previous well-behaved gallery-goers who’d clicked halfheartedly (next page please) or left the mouse primly alone, the kid discovers a geometric game hidden in the overlapping spinning spheres onscreen, drag’n’dropping this on that and that on them till an exact fit begins another scenario.

Murray continues to summarise what we’ve already worked out: that the invocation of the literary version of ‘conceit’ as per the Metaphysical Poets (Donne et al)—as a deceptive, ingenious and elaborate fusion of disparate and surprising elements—itself models the way the project moves from map to model to choreography to synaesthesia. And back again, providing either a send-up or escape-clause for the empty sloganeering and abstract-art-y pronouncements.

Meanwhile the kid examines the documents, captions and other orientation figures taped to the gallery floor. He does a bad-busker mime of arm-pumping Ready? Set? Go! and skitters from one floor-marking to the next, inscribing as Timezone vectors the designs Murray is describing as Arthur Murray dance-steps.

Murray gestures at some of the stockpile of mapping devices we’ve already collected on our way through the exhibits: keys, symbols, lists, dot-points, typologies, numberings, pointers, drawings, equations, stylised representations, icons, ant tracks, axes, directional arrows, blueprints, movement vectors, flowchart lines, procedural manuals, tables, calibration marks, schematic charts, constructible (think Chemistry-class to-scale model) movable assemblages, captions, titles, instrument arrays, bricolage whiteboards. This is one project where the thematic metaphor providing a coherent model and cohesive microcosm is, precisely, that of models and microcosms, so the collaboration is more than five artists working with roughly commensurate rubrics. In a nice extrapolation of the working principle, it’s difficult to know who—from John Lycette, Greg O’Connor, Darren Tofts, Christopher Waller and Peter Webb—had done what or worked with which bits…until or unless you sifted through the website afterwards. The launch resonates with an anxiety of provenance and of navigation: should one watch multimedia as slide-show; does that do anything; ought we be touching that; am I stepping on an exhibit?

Meanwhile the kid fiddles with anything that moves and immerses himself in whatever doesn’t, bouncing from one item to another in a Chinese-checkers or string-art geometry until he’s seen the sites, covered the territory and can safely be bored.

A CONCEIT worked on mapping the exhibition time-space in three dimensions. There’s the planar (print program), with its ironising of the comprehensive modular diagram as coded index or algebraic commentary or interpretive key. There’s the sited (gallery installation), with its playful proliferation of topographic ideas, objects, stories, readings, sonics, nodes, connections and breakdowns using computer screen, video, slides, models, mounted displays, documentation and all available surfaces. And then there’s the virtual (onscreen), framed by kiosk or pulled-out down the modem line, with its (false) promise of precisely-articulated 3D working model and its sleights-of-interactivity offering uncontextualised tourist circumnavigations of static excerpts. It was effective work, despite some inflatable baroque vaguenesses (‘songlines’? lite-Todorov ‘morphology of a grammar’? ‘This is a place for the intellectually amplified’?) that may also be called hyperbolic conceits, and a frustrating hesitancy (refusal?) to use the usual convergent places (program, website) to disarticulate diverse modelling practices that are not reducible to each other except via the abstraction, simplification and regularisation of Doing-A-Diagram ™. Which may be the archetypal gallery experience.

The launch simulated all three dimensions at once. Given this, I’d have thought further reflexivity was a natural extension: a working back to gallery praxis (eg what’s a curator, and do they decide on the map’s borders?) and to exhibition constituencies (how are we the users/readers/audience placed and routed and corralled?) via the project.

The 4th dimension, that of interactive working through, was generously modelled by the blond mischievous boy: less official map than quick sketch, less hermeneutic than heuristic. Better, he demonstrated how to play with the work(s).

A CONCEIT, a collaborative mapping in 3 spaces, curator Christopher Waller, artists and authors: John Lycette, Greg O’Connor, Darren Tofts, Christopher Waller, Peter Webb, RMIT Project Space, Melbourne, June 2 – 9

RealTime issue #26 Aug-Sept 1998 pg. 34

© Dean Kiley; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

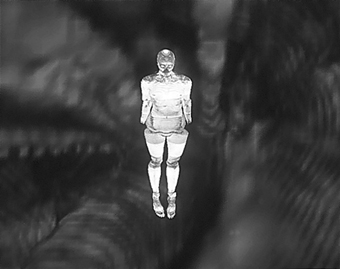

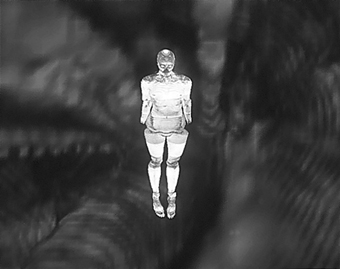

Justine Cooper, Rapt

“What, however, I would ask, are the forces by which the hand or the body was fashioned into its shape? The woodcarver will perhaps say, by the axe or the auger; the physiologist, by air and by earth. Of these two answers the artificer’s is better, but it is nevertheless insufficient.” Aristotle, On the parts of animals

“I wanted to take it somewhere else…create a wandering footnote to the Visible Human Project…and something else again.” Justine Cooper took her own very live body through an MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scanner and came out with the makings for what I could only describe as an un-hinged, immortal body clock.

Turn on the animated section of Rapt and watch it tick over…build, unbuild…and build again. Each time it re-assembles through a different axis and with different body parts; a body bag of bits and bytes, programmed to construct, destruct and reconstruct in unnatural patterns of growth and decay.

Six hundred image files were generated through the scanning software. Cooper went to work on them, outputting living/dead body slices into two formats for presentation. The high-end process consists of a rendering of volume elements into a series of black and white 3D animations.

The second—low-tech—output form for this work consists of a curtain wall of individually sliced film images compiled into what seems at first a static installation. Readings of the work vary with the degrees of transparency and opacity offered by the film material, as well as the viewer’s perspective—side on, front-on etc—on these quietly complex compilations of the total body.

On viewing the animated section, the spectator is ushered from masterful exterior views of this one squirming computer-made body to unanchored fly-throughs of tissue, bone, sinew and strange body cavities. For a moment an eye-ball rush through the white haze of solid bone structure triggers a brief and beautiful association with moisture-bearing storm clouds.

Cooper remarks, “The movement of the body would be impossible in ‘natural space’ but in this fractured space-time the body spontaneously produces itself—in faithful anatomy—and in contortion. Time appears to dematerialise the body and then reconstitute it, hardly the normal cycle of decay. If entropy gives time a direction, time becomes circular in this case, not linear.”

Some questions, however, remain unanswered: In what other ways could the raw body data be incorporated into objects/events that make art while acknowledging a debt to the technologies and output forms of ‘unlovely’, meaningful medicine? Cooper’s choice of output and process solves much of the mystery.

The combination of projected 3D animation and vertebral curtain of inanimate photograms into a single bifurcated space, mixes pictorial models, reproductive technologies—disturbing the continuity of ‘beautiful outlooks’ upon a digital landscape. While the animation may be viewed with detached mastery, the ice-block of body slice-pics effects a psychological dislocation between whirling ‘auratised’ digital finish and cool, opaque originary data.

In Rapt, Cooper gives medical imaging back to the patient. The advanced science of healing (it gets smarter and smarter—we still die for pathetic reasons) is converted into a ‘plain language’ piece of art. It’s a science show and a side show at the same time.

The work does not stand out in the field of progressive digital art. It draws back, bearing the scars, “the traces of the conceptual determination of the forms proposed by the new [medical] techne” (Jean-François Lyotard, The Inhuman: reflections on time, Stanford University Press, 1991). It also falls into some shadowy space between digital optimism and photographic nostalgia.

Shuffle a stack of X-rays and CAT scans from a personal medical misadventure. Fold them into the time-warp between future professional diagnosis and the lay person’s dumb fascination with celluloid souvenirs of bodily catastrophe. You’ve just entered into the spirit of Rapt.

Justine Cooper, Rapt, installed at Sydney College of the Arts, March; video component screened in D.Art, dLux media arts’ annual showcase of experimental digital film, digital video and computer animation art, 45th Sydney Film Festival, June 5 – 19 and touring nationally, including MAAP, Brisbane.

RealTime issue #26 Aug-Sept 1998 pg. 27

© Colin Hood; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

A series of recent articles in the Higher Education Supplement of The Australian have once again raised the problem of skilling in Communications and Media, and its status in an academic context. Behind the ‘boom’ rhetoric surrounding the growth of Communications and Media in this country, and despite at least 20 years of debate about theory and practice, what we can call ‘the skilling problem’ calls for attention as insistently as ever—especially in the area of digital media.

By way of definition, the skilling problem has to do with instilling competency in students, in particular ‘media’ and ‘communications’ skills, however they may be defined.The definition of skills is a central issue. As a media educator, for example, a key aspect of my job is troubleshooting. This involves working in computer labs with minimal technical assistance, surrounded by students working at different ‘speeds’.

If things are going well, students are undemanding. If the technology is playing up, I can expect numerous calls for help. With tricky problems, ‘help’ involves assuming control of the computer, and rectifying the situation as soon as possible. At this point, the student usually steps back from the machine, or has a break. Recently, however, my assumptions about this scene were challenged when a student commented, “That looks like a really useful skill.” While troubleshooting is part of my own stock of tools as a teacher, crucial to assisting students, I had not considered using these moments to bring troubleshooting into the curriculum.

Anxiety about the skilling problem raises important questions about the definition of skilling, and the links between Communications, other areas of arts practice, and Humanities thinking. Particular modes of skilling can place these links in jeopardy, especially through segmentation of the production process. There is a tendency to think about skilling in Communications as an activity with its own unique set of procedures, concepts and truths, following its own industrial imperative, and with few links to other media or arts contexts. This tendency can in turn feed into an idea of Communications as something that stands detached from other kinds of artistic, technical and theoretical practice.

There are perhaps traces of this phenomenon in the name change of the Sydney Intermedia Network to dLux media/arts. One of the arguments supplied for the change was that developments in communications had given ‘network’ a different meaning (eg a mobile phone network). The assertion of media/arts in the new name can be read as a gesture against a particular image of communications. Similarly, as a Humanities academic it is worrying to watch Communications become detached from the (media) arts, or the Humanities, and connected instead to, say, electronic commerce, or information systems.

Yet, what if one of the causes of this detachment was the skilling problem, and its baggage? What if skilling happened differently? The experience of helping establish a Communications degree at the University of Western Sydney (Hawkesbury) caused me to question the development of Communications, and the parameters laid down for training in that area.

Disciplinarity, transdisciplinarity and ‘non-academic’ disciplines

Rather than succumb to the education-industry dichotomy—the struggle between ‘professional training and critical studies’ that typifies many Communications programs—it is possible to displace these dualities by examining the disciplining effects of institutions (including our own), industry, and the professions. According to this view, ‘the industry’ is a gathering of disciplines, formed in a broader disciplinary field, that should be approached in the spirit of transdisciplinarity. A practical example of this approach relates to what are sometimes known as ‘production subjects’: the problem of how to situate video and multimedia subjects in relation to one another is not simply a problem of connecting two practical areas, but of recognising the disciplinarity of these areas, and of negotiating their passage through the academic domain.

The question of the disciplinary status of traditionally ‘non-academic’ media production subjects is often elided in the university, particularly when coupled to notions of training for industry. It is one thing to construct inter-disciplinarity in the academic domain, but how does inter-disciplinarity apply to a traditionally ‘non-academic’ discipline like video? Production subjects represent an existing and long term disciplinary problem internal to many Communications programs, usually expressed in terms of a chasm between ‘production’ and ‘analysis’ (eg the divide between media production and screen studies).

But clearly what we’ve designated as non-academic disciplines can be rigorous in an academic sense. Production subjects can, in liaison with others, trace a complex interaction between audio-visual literacy, practice, the digital, genre, words and bodies, in a theoretically informed way. Production subjects need not be about setting up video and multimedia as discrete domains, but exploring the in-between of these disciplines. Two subjects I have been involved with are worth mentioning here.

A subject such as Multimedia Communication can become a lens through which the ambitions of multimedia can be examined, as well as a vehicle for questioning different models of communication. A subject like Transdisciplinary Video can take up the problem of disciplinarity by questioning video as an essential entity, and instead seeing it as being marked by and within a range of other disciplines (Broadcasting, Cinema, Sound, the Digital, Painting). Both subjects, along with others, can collaborate in an extended conception of multi-and mixed media communication that disturbs the conventional segregations between different media. This approach would go beyond the usual deterministic exploration of the ‘impact’ of technological change, or ‘digital media’.

I would suggest that accepted categories such as the ‘capital M Media’ are themselves part of the problem. New practices have brought into question the way in which the category ‘Media’ gathers together a field and flattens out a diverse ensemble of practices. Today, we can no longer be certain about what we mean by media even if increased reporting of the media by the media masks this uncertainty to some extent.

Non-linear digital editing provides an example of the ambiguity of media. In the Media 100 digital editing system, media relates to the partitioning of the supplementary hard drives necessary to deal with large video files. (Thus a 17 gigabyte drive is partitioned into 4 x 4 GB media plus one other.) This is very different from conventional understandings of media as a channel, and marks an interpenetration of artistic and technical ideas.

This use of media gives rise to new understandings of the term. Media is referred to as a block, in a broader process of construction. In a different sense, media is seen as a material you work with (or allocate) to achieve an effect.

The tendency to use the plural form ‘media’ to designate a singularity emerges, in my view, out of a digital understanding of forms, where digital files can be articulated in a range of formats for presentation.There is sense in this use of the plural, in that it highlights the way media is being redefined as a multiplicity. But this conception runs at odds to capital M media, with its relation to a homogenising mass. This makes the conventional understanding of media problematic in ways that strike at the core of Media Studies.

Philosophy/conceptual practice

Implicit in the idea that traditionally non-academic disciplines can be accommodated within interdisciplinarity is an affirmation of different forms of conceptual practice—that is, an acknowledgement of diversity on the level of conceptual practice.

What is referred to as ‘transdisciplinarity’ has to do with the interaction and interference between different disciplines and conceptual practices. It is worth elaborating on this idea of conceptual practice in more depth. In Deleuze and Guattari’s What is Philosophy? (Columbia University Press, 1994), philosophy is defined as the creation of concepts. In Deleuze’s Cinema 2 (University of Minnesota Press, 1989), theory is something that is made. It “is itself a practice, just as much as its object”, and so cannot be assumed to be “pre-existent, ready-made in a prefabricated sky.”

Deleuze and Guattari grant philosophy an exclusive right to concept creation. Nevertheless, as Paul Patton argues in an article in the Oxford Literary Review (18:1-2, 1996), this does not mean that it is metaphysically pre-eminent or epistemologically privileged in regards to other activities—Art, Science, Cinema. For example, in relation to the cinema, Deleuze suggests that while the practice of cinema has to do with images and signs, the elaboration and articulation of that practice by filmmakers and critics involves a theoretical work—a conceptual work specific to cinema. While this practice may not be philosophy, it is without question a conceptual practice.

A valuable aspect of Deleuze’s writing on the cinema is the way he defines the significance of this conceptual practice for philosophy. “So there is always a time, a midday-midnight, when we must no longer ask ourselves, ‘what is cinema?’, but ‘what is philosophy?’” Deleuze’s work enables a questioning of philosophy’s ownership of conceptual practice.

As Patton points out, the creation of concepts does not simply mean the creation of novel or new concepts. It also means the creation of untimely concepts, acting against our time, or acting on our time. Transposed into the space of Communications, the notion of conceptual practice allows us to interfere in the way Communications imagines itself as a discipline of ideas. Deleuze and Guattari themselves take up the abuse of “the idea” by “the disciplines of communication.”

More specifically in the media arts, their approach facilitates a questioning of the status of conceptual work in the production of programs and works. Most media handbooks provide an extremely circumscribed account of the role of ideas in the production process. Following a ‘25 words or less’ model, ideas are subjugated to a brief phase in the pre-production stage of a project. “You should be able to write the main concept down in a few sentences, sometimes in just one.” (Mollison, Producing Videos, Allen and Unwin, 1997)

In a context in which a mentality of manufacture has marginalised the concept and ideas—even while bemoaning their absence—the notion of conceptual practice provides tools with which to contest our definitions of production, composition and assembly. In particular, it can help in questioning the usual segmentation of conception and execution typical of manufacture, and now entrenched in our ‘normal’ modes of media skilling.

RealTime issue #26 Aug-Sept 1998 pg. 13

© Steven Maras; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

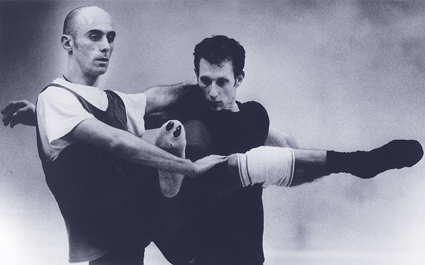

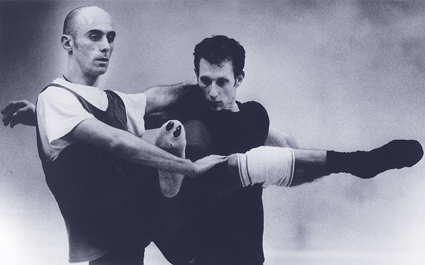

Michael Schumacher and Vitor Garcia in Proxy

To launch his 12 month residency at The Royal Festival Hall with a bang, British choreographer Jonathon Burrows curated an evening of international contemporary dance extravagance. The foyer of the Queen Elizabeth Hall was all a-buzz as what seemed to be London’s entire dance-world twittered and tingled in anticipation of the rare delights of this one-off event. Screens showing videos by Peter Newman hung over the packed auditorium, creating a backdrop of party-night animation and punctuating the pauses with inspiring sky-diving, flame-throwing visuals.

Burrows had worked his connections with the Ballett Frankfurt to bring together choreographers sharing his preoccupations with time, structure and physical detail. A booklet of conversations held with each of his guests illustrated the braininess behind this dance. Best read after the performances, it foregrounded many of the thematic similarities of approach made so richly manifest on stage.

Americans Meg Stuart and Amanda Miller performed their own work, William Forsythe showed a duet made in collaboration with Dana Caspersen of his Ballett Frankfurt, and prodigal son Michael Clark was back with a sneak preview of his new work. Paul Selwyn Norton, going soon to Melbourne to choreograph for Chunky Move, opened the event with a duet for two extraordinary dancers from the Ballett, the expert improviser Michael Schumacher and Vitor Garcia.

Selwyn Norton’s Proxy was the longest work of the night at 20 minutes and as such ignored the less is more dictum. While Selwyn Norton delights in the incredible range of expression of his virtuoso dancers, allowing them quirky and elaborate articulations, he distractingly overwhelms these revelations with an unnecessarily generous embrace of theatricality. Strange props, such as the enigmatic rubber mats which littered the stage, and tomfoolery with a mike-stand cluttered the fascinating exchanges between Garcia and Shumacher. The recorded sound-track (Gavin Bryars’ A Man in a Room Gambling), a fictional radio crash-course for card-sharps, said it all; “Pay attention to the moves”, lilted the seductive Latino announcer, “because they are so simple that they need some audacity in order to be performed.” Shame then that Selwyn Norton didn’t give them more space.

Meg Stuart’s solo, XXX for Arlene Croce and Colleagues, was the palate cleanser required after Proxy. On a bare stage she danced her ironic response to the New Yorker critic’s now famous description of Bill T Jones’ AIDS related work Still Here as “victim art.” Infused with human strength and frailty her contortions were both beautiful and abased. To Gainsbourg’s Je t’aime moi non plus, her scrunched up face, jutty hips and stiff sides were bountifully defiant. Ten minutes and she had said it all. The pause hummed with approval.

And catty expectation, because bad-boy Clark was next on, with a glimpse of his first full stage work for 4 years. Dancing with Kate Coyne to a breathtakingly anarchic score by Mark E Smith of The Fall, Clark was in characteristically provocative form. Blinding his straining audience with 6 full spotlights at 12 o’clock the duet was barely visible. While the bitches later sniped that he was hiding, it was fair to say that Clark certainly wasn’t making his new work easy to see. “Welcome to the home of the vain” intoned Smith in his laconically spiteful drawl, and Clark collapsed again from point to splay in a decadent and downright ugly drop. You’ve got to love him…or loathe him.

Amanda Miller’s Paralimpomena translates literally as “leftovers” and her solo comprised “fragments from earlier group works that I felt didn’t get communicated.” Miller flowed around a dark stage like a spirit, ghostily unmuscular amidst the exertions of the evening. Perhaps that was why her whimsical work seemed so brutally dismissed by Forsythe and Caspersen’s show-stealing duet, The The for Jone San Martin and Christine Burkle.

Expert interpreters of Forsythe’s angry physical intensity, these peculiar twins knotted themselves together across the floor, in a seated version of a tantrum which surged through their bodies producing the most extraordinarily exciting shapes. A recorded voice read out time to remind us that there were intellectual battles raging too. As an extract from the full-length 6 Counterpoints, this duet is a thrilling introduction to a world of intellectual and physical rigour. As the end to an evening of vivid provocations it was a perfectly abrupt and unsatisfactory end.

Kick-starting a year of commissions and collaborations with an adrenalin shot of creativity, this event left the audience even more full of questions and opinions than when they arrived.

As it is—Choreographer’s Choice, curated by Jonathon Burrows at The Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, Paul Selwyn Norton making Proxy for Michael Schumacher and Vitor Garcia, Meg Stuart making a solo, xxx for Arlene Croce and Colleagues, on herself; untitled work by Michael Clark for himself and Kate Coyne; Parlimpomena by Amanda Miller for herself and Seth Tillet; The The by William Forsythe and Dana Caspersen for Jone San Martin and Christine Burkle; video installation by Peter Newman, July 9

RealTime issue #26 Aug-Sept 1998 pg. 45

© Sophie Hansen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

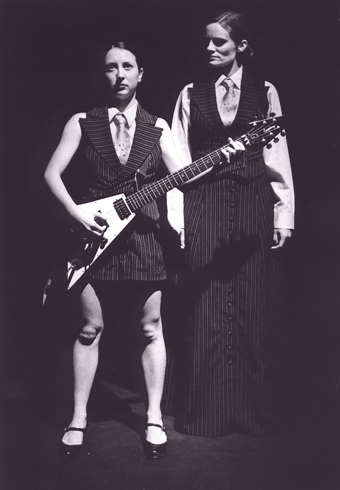

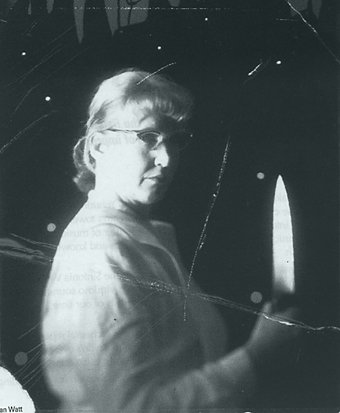

Lisa O’Neill and Christie Johnston in All Tomorrow’s Parties 1 and 2

photo Jodie Ranger

Lisa O’Neill and Christie Johnston in All Tomorrow’s Parties 1 and 2

With very little financial support, each year Lesbian and Gay Pride presents a festival that speaks to the diverse queer communities of Brisbane. With this in mind, Cab/Sav, a season of short works, followed a cabaret format with performances ranging from the highly physical to the intensely vocal. What to some punters seemed surprisingly lacking in “queer content” was a reflection, I suggest, of the evolution and maturation of queer performance in Brisbane resulting from the combined performance histories of such collectives as Pride, Cherry Herring and the now defunct Crab Room.

The latter two collectives have fostered the continued development of many of the movement-based performers in Cab/Sav. The evening opened with Caroline Dunphy’s flippant flight attendant, complete with flashing semaphore wrist bands. The frivolity of her piece Transonic—a monologue in few words was the exception in an evening of somewhat sombre pieces.

Christina Koch’s Giant’s Hopscotch Party, was an innocently executed dance of death which showed the macabre joy of a giant crushing ‘the little people’ with various Suzuki influenced walks and stomps. Although the piece lost focus towards the end as the movement became smaller and more intimate, it was one of the few performances I have seen where heightened Suzuki movements actually drove the narrative.

A strong physical presence continued with Brian Lucas’ take on war, religion, politics and Patsy Cline in psycho/the/rapist #3—joan of arc. In his simple adjustment of a skirt, Lucas transformed from a hooded, softly spoken, petite Joan of Arc into a towering queen dancing to Patsy Cline. His repetitive use of movement, recorded and spoken text and music created several personae though the connections between them were not always clear. Several images from John Utans and Jason Wollington’s performance remained long after their piece ended, particularly the chalk outline of one of their bodies traced after an intense contact improvisation. Unfortunately, the physical subtleties were often combined with slides of heavy-handed text.

A complete departure from the physical was Shugafix, a selection of songs sung and melodramatically gestured by Lucinda Shaw accompanied beautifully on cello by David Sells. Technical difficulties made the lyrics almost impossible to understand and as the audience were quite adept at reading bodies by this stage of the evening, this still and self-absorbed performance seemed rather incongruous. Mark McInnes, however, managed to successfully traverse my physical expectations of the night in his understated Four Songs. McInnes’ exquisite command of both French (La Vie en Rose) and German (Falling in Love Again), his soft camp introductory patter and his confidence in his own stillness created the intimate cabaret atmosphere promised in the production’s title.

By far the highlight of the evening and the crucial performances that both linked and questioned the separation of the voice from the body was the combination of one of Brisbane’s most talented experimental vocalists (Christine Johnston) with one of our most inspiring physical performers (Lisa O’Neill). In All Tomorrows Parties 1 and 2, Johnston used such diverse musical influences as the humble Hammond organ, Velvet Underground, Bach and the theme from the film Orlando to contrast with O’Neill’s tap-dancing, Suzuki-stomping and sassy dancing. The dead-pan expressions, dry humour and occasional stealing of looks from one another created a sense of two aesthetically similar performers desiring each other’s inherently different forms of expression. Throughout both pieces, we gradually saw each performer attempt the other’s skill, from O’Neill hesitantly joining Johnston on the organ to Johnston’s slow walking exit from the space. The final image of the night gave the impression that the physical and the musical can successfully embrace each other with O’Neill’s sudden possession of the Flying V guitar.

Overall, Cab/Sav may have benefited from a curator or an outside eye. It seemed that the event was drawing on a cabaret format, however, the relatively serious ‘theatre’ atmosphere and absence of alcohol at Metro Arts created an environment where the audience were less able to relax. As a season of short works, Cab/Sav continued local queer performers’ exploration of conceptually mature vocal and physical vignettes which would give its Sydney counterpart, cLUB bENT, a run for its money.

Cab/Sav, Lesbian and Gay Pride Festival, Metro Arts Theatre, June 17 – 20

RealTime issue #26 Aug-Sept 1998 pg. 43

© Stacey Callaghan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

In dance, some people are beginning to talk about studio practice as if it might be different from other kinds of dance practice. And yet it’s self-evident that any dance artist would have a studio practice: that is, something that they do in a studio, some repeated, habitual exercise, or action as opposed to theory, that is part of their performance-making. But there are several ideas about studio practice which need stressing, if only to assist in separating out some kinds of work from others, and to emphasise their differences rather than similarities, if dance practice is not to be imagined as an homogenous enterprise with a uniform, singular focus or ideal.

Picture two idealised scenarios: a studio, permanently occupied by several dance practitioners who are there for several hours a day, most days, often by themselves, or playing and talking with each other, pulling old ideas apart, finding out what still interests them, rejecting some material, expanding other movement ideas, finding new ones, showing them to each other and guests, feeling out each other’s ideas.

Another scenario: an hour long, highly organised practice session following immediately after a specifically designed technique class, fitted tightly into a schedule of other back-to-back rehearsals; dancers move quickly from one choreographer to another, one dance to another. Each work might be allocated 4 or so hours a week rehearsal time, during preparation for public performance. Choreographers in this case need to know almost exactly what they want to happen in that hour; each move is described by referring to the dancers more or less common vocabularies, with small changes, different inflections here and there, a rearrangement of what is already known. Working at this speed could not be managed if each move had to be investigated first.

The first scenario adumbrates a particular notion of research, something physically-based, on-going, and different from academic or theoretical research. Here it refers to careful inquiry and critical investigation of the body, looks into meanings of action and senses of aesthetics alive and developing in a person’s body. The notion of research in the area of company-based or even independent dance, is often applied to those more or less imaginative re-arrangements of off-the-shelf steps. While this might extend known theatrical tradition, it may not necessarily challenge the wider body of dance as an artform distinct from that theatrical tradition.

Dancers in the first scenario seem to be concerned more with developing ways of working, a body of work which is fundamentally related to the actual bodies of those artists who create it, so that its performance can be engaged with on many levels; it is not a finished product, something fixed and closed, which can stand by itself apart from the artists who create it.

The idea here is one about difference: about a person dancing, whose dance is about his or her own body, whether in performance or rehearsal; or a person who is trying to be something or someone different from their ordinary selves in performance, even if they’re simply trying to be a dancer. There seem to be two quite different performers here, and an almost unbridgeable gap between them.

It takes time for students and other dancers to become aware that what they assume to be their own practice is really based on their relationship to someone else’s class technique. For pioneers like Martha Graham, the purpose of technique class was simply to help her dancers better perform her choreography, so it was firstly a choreographic tool, rather than the pseudo-religious dogma it later became. Similarly, with ballet techniques, the kind of presentation of the body and the steps by which this is accomplished form the basis of the 19th and 20th century classics. For dancers to begin to develop their practice past that kind of externally imposed discipline requires effort, insight and a will to investigate the nature of practice itself, something not as easily accomplished within the second scenario.

How might these differences manifest themselves in performance? Decades ago in Australia, theatre and dance practitioners were seeking to expand audience awareness of what theatre practice might encompass. For many years, audiences have been invited to participate in informal studio showings; we have also had performances in the round, and in site-specific, non-theatrical venues, open rehearsals, works in progress, and the like.

But it seems to me that in dance—maybe not so much in theatre—these events often have been thought of, perhaps unconsciously, as mere practice for some other more important main event—the proscenium arch performance, or something that approaches this. And so, without acknowledgment or even realisation, the work performed in these venues has been made with these grand public front-on venues in mind.

Proscenium stages are perforce also about concealment: blocking views of the performers that distract the audience from a required focus, from much of what goes on, or might go on, both on and off stage. What is shown at these events is an entirely public version of social life, a view of cultural mores and myths to which we might safely claim allegiance and derive identity.

On the other hand, in a studio space, performances occur in what can be thought of as a much more private space, inhabited as if by guests rather than an unknown public. Performances here have the aura of intimacy and invitation. This kind of space seeks to remove the one pointed, single focused, frontal view that proscenium arch stages create. By removing the formality of wings, frame and curtain, we are less subject to its frontal perspective, and have the possibility of analysing what was previously hidden. The relationship between what is hidden and what is visible becomes fluid and subject to the audiences’ discrimination. Preparation, awareness, hesitation, concentration, focus, small shifts of weight and intent all become part of the work performed.