Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Romeo et Juliette

photo Laurent Philippe

Romeo et Juliette

We are not just here, we are before, and after.

We are not just now, we are once and future time.

Touch me on the skin, backwards, touch only in the now, and I will shrink with you into the smaller time I so crave to be out of. Touch me

small, and I will gripe, I will

harbour and wallow, call me

small, and I will tell you something’s

wrong. Call me

large, into the fullest of extension, and I will

dance with you over that tightrope that casts itself into the ocean, and love you for being a

small part of the largeness‚ calling.

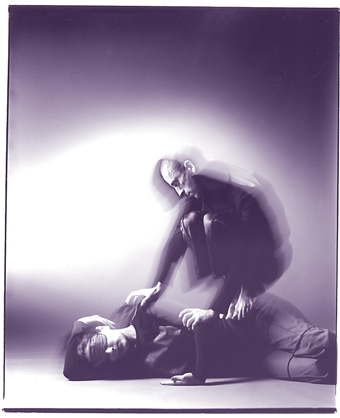

Remind me I am small. Preljocaj’s beautiful bodies, glossy linen boys, nipple-silk girls, leathered Capulet thugs with biceps from a Darlinghurst gym. They push and shove like starlets do: with a makeup lady’s grimace, fakely, thinly, we’ve seen this before. Oh, not that touch. Please, not that touch. This Bad Boy of Ballet, Il epate les bourgeois, non? Melbourne’s monsieurs et desmoiselles fail to clap at peak moments, and I think it’s not their fault. Tho’ Juliet is vulnerably stunning, Romeo thrusts his body over her like a street-scum rapist in a play by Edward Bond. Those so-close-to-erectile tissues that we are meant to think sex. We are meant to think, stylish grunge. Not only do this ballet’s moves and turns repeat themselves on old corps de ballet gridlines, but the borrowings are thick (and therefore thin). This is bonking ballet, Aaron Spelling does Bernstein with Miami Vice thrown in. Two weeks later on ABC TV, I see Michael Bogdanov’s London housing estate cast (Shakespeare on the Estate) render Lady Macbeth churning with ambition to escape her ruins, Caliban sipping beer, charting the loss of his hopes, his island dreams, a black Juliet accepting the clumsy whiteboy’s proposal in the pub and her dad going apeshit at her in their crowded flat. Outside, he prunes the rose bush as if it was her life. The fierceness of their disappointments and wiry loves. Preljocaj’s touch has no love—in fact, no hate. Capulet = Montague. The “let’s walk” dance during Prokofiev’s strident masked ball segment becomes an Easter hat parade. Shakespeare is larger than this because we are larger (and not the other way round).

Oh, there is a nice, a beautiful swing, where Juliet leaps into Romeo’s twirling arms. They go so fast, so fast, that their turning smashes the air, the smell of roses breaks, it’s a long time before they slow. This captures the once and future time that happens in that awesome moment of love before family clips your edges and you break down. The heavens may smile with lovers, but the earth’s crust shrinks when a cliché assaults you. Did I actually hate this show? Perhaps. Perhaps that night, this life, I can’t bear to be smalled down.

This is to the point, to talk of consummation, the feared-or-revered instance of being subsumed. But consummation, perhaps, reawakens the accompaniment always about your skin. (When one hand claps, the other silent fingers also drum.)

When you sing, in tune, more than one voice sings in you. When you growl (as Caliban does on his rocky shores), the landscape also growls. There is not just a clarinet, not just a saxophone: even in a solo work, a single note (as when Rosman played Formosa’s Domino, in Elision’s second concert), there is an ensemble playing.

And in All About (Manca’s 1996 trio dedicated to Mark Rothko), there is not one piccolo, one clarinet, one violin, not these only, or the relationships between each (this is visible, obvious), but each has its own otherness: its about-to-be and what-has-been; its being-in- and out-of-time. A note, a song, slips in from all time (if the note is true). These dimensions are held within a weaving, adjusting tensions, teasing at edges like insects in a web. The tangible geometry of it. This is why I can’t agree with someone in the audience (Elision, A Matter of Breath), complaining Elision should be playing Perezzani’s joke to us. He wants histrionics, a little, light show. I don’t think that’s the point: the joke is in the music, the colour is already in the sound. (Remember Synergy in Matsuri Mark II in Sydney, where sophisticated slides of the earth’s globe turning killed the magnanimous, multitudinous, at times more delicate associations of the sound.) Rather, the matter with the Breath concert to me lies elsewhere.

Each piece is progressively less focused on the amassing of statements than on lipping the edges (skin to wood/brass/string; thought to breath) from where sound comes. But such focus perhaps needs more physical intimacy than the Iwaki Auditorium allows. Elision’s previous installation works in derelict buildings, old churches, railway yards (Lim/de Clario’s Bar-do’i-thos-grol; Barrett/Crow’s Opening of the Mouth) stretched our receptors to sound—mid-night, pre-dawn, brick kiln, underground, making us listen blind, listen tired. Although Breath’s pieces asked me to receive small timbres, textures, virtuosities (inherent in even the largest works I’ve heard Elision play), the podium feels more and more aloof, the lights keep bowing in and out as if the musicians are actors awkwardly teasing us with bows.

It is not my problem with Sunday’s Into The Volcano at all. From the opening note, solo and ensemble work have consistent hold. The young guest composer Giorgio Netti’s note all’Empedocle is a modestly magnificent piece by a composer whose knowing marks him as much older. Again and again the ear is led back into a work of quietly astonishing structure, tracking instruments that move through each other as the eye and hand takes in a piece of crystal. Meticulous yet liberating: somehow, suddenly, you are placed half-way down the volcano. Within the complexity lies an intimacy of inclusion. Shape has a pulse, and span-in-time. At one point, Elizabeth Drake and I find our hands conducting in synch, as if we share an arm. These players, strangers, are as close as my breathing allows.

Liza Lim’s The Heart’s Ear stretches and flattens the tuning of notes in a way that slices historical time: windows of different tenses slide in and out over the length of a bar. A sure touch in instrumental combinations, valves pumping and speeding, mellifluous strings with rasping winds. And then, 4 chambers pulse. How is this achieved? A 6 year old in the audience is on the edge of her seat, conducting, eyes agleam. This concert understands something of the geometry of our listening, being.

I am touched, because touching meets my ear. I can listen (like Keats to the thrush) with full-throated ease. Perhaps this respect is all I ask for the effort of my listening.

Ballet Preljocaj, Romeo et Juliette, State Theatre, October 3; A Matter of Breath, soloists of Elision Ensemble, Iwaki Auditorium, ABC, Southbank, October 31; Elision Ensemble, Into The Volcano, conductor Sandro Gorli, Iwaki Auditorium, November 1

RealTime issue #28 Dec-Jan 1998 pg. 6

© Zsuzsanna Soboslay; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Romeo et Juliette

photo Laurent Philippe

Romeo et Juliette

Why is it that so many dance works in this year’s Melbourne Festival concerned themselves with limits? Streb played with the limits of a body in space, Nederlands Dans Theater III stretched the age limit of the dancing body, Ballet Preljocaj represented the limits of the totalitarian state, Chunky Move toyed with the limits of a physical body, and Company in Space explored the limits of the flesh/video interface. There is no intrinsic merit to be found in exploring a limit for its own sake. Try bashing your head against a brick wall (QED). No, the exploration of limits must offer something more, some insights regarding its approach.

I think that Streb’s performance aspires to greater limits than it goes anywhere near achieving. In a circus-like stream of acrobatic body slams, wall flings, and mattress thumps, 10 or so lycra-wrapped bodies yelled commands, syncopated near-misses, hurled themselves against surfaces and, in the ultimate drama, dived through a sheet of plate glass. In her company manifesto, Elizabeth Streb writes that “Streb isolates the basic principles of time, space and human movement potential” (program notes). Yet the works themselves very quickly coalesced around self-imposed limitations. The speed of the movement was homogeneous, the tension consistent, beginnings and endings arbitrary. Even though we were “introduced” to each dancer by name, age and weight (racetrack data), it was very hard to differentiate their movement qualities. Little challenge was meted out to our conventional sense of a body in space and time. Two pieces call for recognition: Little Ease (1985) consisted of a coffin sized box, requiring the dancer to occupy its numerous denominations (this was Elizabeth Streb’s signature solo). It reminded me of Nietzsche’s remark about our dancing in chains, the point being that strict limitations can be productive. The other piece, Up (1995), really did live up to the artistic hopes of its creator. Working on a trampoline, members of the company bounced and caught themselves on high ceiling bars, launched themselves from side platforms and returned to the platforms horizontally, bounced onto the ubiquitous floor mats, and ducked and wove through each other. The timing was magnificent and the sense of up definitely and delightfully achieved.

The appeal of Nederlands Dans Theater III was the age factor: all dancers over 40 and, in one case, 62. Their wit, sense of time and precise interactions gave great pleasure. What was less pleasurable was the superficiality of the works. The brilliance of the vignettes in Trompe l’Oeil was tantalising but I refuse to believe that the plethora of sketches was a virtue and not a vice. Compass had a metal ball orbit the stage in a circular motion. Sadly, the movement of the ball was more interesting than the dancing within its circuit. A Way A Lone rescued the night somewhat. A video screen occupied half the stage, re-presenting the live movement but staggered in time and distorted in terms of speed. This work was dedicated “to somebody no longer here.” The question of death inevitably dogs a company of aging dancers. I’m not sure whether the attraction of Nederlands Dans Theater III is that they seem to defy mortality or approach it with grace.

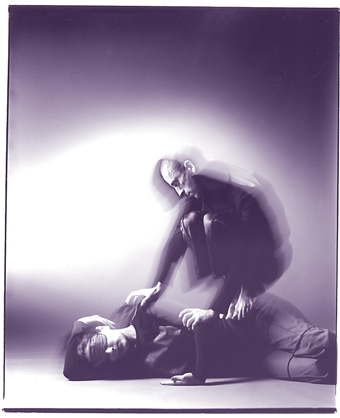

Ballet Preljocaj’s Romeo et Juliette offered much more straightforward limits, the transgression of which threatened disaster, and ultimately produced the famed tragedy of bungled messages and crushed love. Yet however straightforward totalitarian rule may be, its evocation cannot avoid eliciting fear and discomfort. Although not everyone experienced this work as menacing, I found the set, a Dystopian vision from Dune, the not-so secret police, and the concentration camp perimeter with matching German Shepherd, scary. We don’t have to go all that far—to East Timor in fact—to reach a comparable regime of intimidation. Angelin Preljocaj’s imaginary premise was that the social order excised “the freedom to love”, thereby creating a very 20th century setting for this fable of forbidden love and caste war. Not surprisingly, this work has provoked recollections of Nazism, the Balkans, and recently, a remembrance of Pinochet’s terror. Oddly enough, and I don’t really know why, love did not seem too out of place here.

Chunky Move is renowned for its choreographic vigour and full-on dancing. Its typical audience has many more body piercings per square metre than most other social spaces. How appropriate then that Paul Norton’s The Rogue Tool used long metal props to support and limit the boundaries of a body. Gideon Obarzanek’s C.O.R.R.U.P.T.E.D. 2 also availed itself of the limit in terms of a stunning, revolving metal shape rather like a satellite dish gone wrong. I was rather disappointed that more wasn’t made of the spatial impact of its rotation. The dancers mainly ducked under it when it approached, merely to continue their dazzling kinetic play as if nothing had happened. However, I did very much like the short piece, Special Combination, performed repeatedly in a little box-like space in a room not much bigger. A naked body, inscribed by moving projections described lines in space with the surface and volume of her body.

Perhaps Company in Space least merits a discussion in terms of limits. If there is a limit to their work, it is the shifting sands of contemporary video, music and computer technologies. Nor does the company fetishise technology, a project rejected by video artist Bill Viola as doomed to bore. A Trial by Video purported to put on trial a number of axes of domination (racism, sexism, political power). Where better to stage such an evaluation than that Gothic meeting place, the former Melbourne Magistrate’s Court. Not that questions of domination have ever been of concern to our legal system. Most of the members of the court—Speech, Dissent, Case, Diplomacy and Trial—appeared in person. Incommunicado appeared from outside the court, from London in fact, juxtaposed against live-video images of the local dancers. An odd interaction, yet one more touching than the stiffly orchestrated series of corporate handshakes (Diplomacy) we witnessed in the flesh. But this is a work which interrogates and challenges such assumptions concerning the dominance of flesh over film, of presence over absence.

Must a work of artistic significance always extend or transgress limits? Traditional conceptions of the avant-garde might suggest that great art requires the breakdown of barriers. Yet whether one is inside or outside a limit matters less than the substance of the work and its potential to inform.

–

Streb, October 15 – 19; Trompe l’Oeil, Nederlands Dans Theater III, October 23 – 25; Romeo et Juliette, Ballet Preljocaj, October 19 – November 1, all at State Theatre; Fleshmeet, Chunky Move, Malthouse, October 21 – 31;Trial by Video, Company in Space, former Melbourne Magistrates Court, October 22 – 31

RealTime issue #28 Dec-Jan 1998 pg. 5-6

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

In a long rectangular space, 3 white squares are arranged into the shape of a pyramid—one square in front and 2 behind. The shrill hum of cicadas and the squawking of crickets occupies the aural space. One of the white squares is filled with sand and a body is buried underneath, resting in a supine pose, an upside down bucket covering the head and neck. Only the feet and lower arms are visible. As the hiss of insects increases in volume, the foot slowly begins to move. It repeatedly flexes and curls in slow luxurious movements. The foot lifts and the leg emerges from the sand. It curls, writhes and twists like the body of a snake. The foot, the snake’s head, darts from side to side. It moves to strike. The space is transformed into a hostile environment simulating, perhaps, the hot summer’s day that the Beaumont children disappeared.

Did a snake in the grass take the Beaumont children? Or was it a freak wave that carried them far out to sea? An arresting piece of performance in the Brisbane Festival VOLT program, Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? co-written by Maryanne Lynch and Shane Rowlands and directed by Fiona Winning, did not provide easy answers. Rather, it examined the urban myth that has grown up around the disappearance of the 3 children from a popular Adelaide beach in the middle of summer. Written for solo female performer, Rebecca Murray, Baby Jane brings together 2 stories of 2 people living 30 years apart (1966/1996) who are equally obsessed with the children’s disappearance.

At one moment Murray plays a 9 year old girl negotiating the boiling hot beach sand or getting dumped by a huge wave. The next she is transformed into a 39 year old woman in a sheer white dress and red shoes, standing on the porch waving goodbye to family or friends. The girl wonders how many buckets of sea water she can swallow in case her pet dog is taken by a freak wave. She practices her speech to strange men who may want to entice her into a car with boiled lollies. The woman, we discover, lives in the Beaumont house and spends her time scouring the place for traces of the missing children. She toys with height markings etched into a wall in red pen. She finds 3 embroidered hankies in a crack in the wall, each a different pattern indicating the distinct personalities of the owners. Her phone rings but there is no one on the other end. The woman takes this, together with the traces she has uncovered, as a sign that the children are still present. She explains her theory over the phone to the host of a talkback radio show.

The poetry of the text was enhanced by the design of the performance space and by Rodolphe Blois’ soundscape. The final sound-image of a giant wave crashing over the audience, left us with an accretion of images (debris) to pick through and make sense of. In this way, Baby Jane explored the poetics of urban myth making.

Headlining the festival’s theatre program were a new adaptation by Neil Armfield and Geoffrey Rush of Beaumarchais’ The Marriage of Figaro for the QTC, and an adaptation by Helen Edmundson of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina for the UK’s Shared Experience Theatre. While both productions were outstanding, it was Shared Experience’s physical style of performance that stole the limelight. Edmundson’s text juxtaposed the stories of Anna and Levin. Present on stage for much of the performance, their clipped responses to each other’s questions served to set the scene and create a fluid, fast moving performance. The semi-circular set with a sliding central panel made for a flexible performance space. With the panel fixed in the middle, the performers sometimes played out 2 different scenes simultaneously. In one scene, Anna, centre stage, carried on a dialogue with both Vronsky and Karenin, who entered and exited through separate doors created on either side of the sliding panel. Anna being sandwiched between the 2 men, gave concrete form to her growing distress.

The performance also put many sequences of stylised movement and repetitive gesture to good effect. For instance, in the racing scene Vronsky is placed amongst the race crowd. His mount is played by Anna and as the crowd watches the race we see Vronsky ride Anna into the ground. The train that Anna falls under is a line of chorus actors performing a choreographed dance. At the height of her fever, a chorus actor personifying death covers Anna. She has to struggle with the actor before she can regain her health. Frustrated in love, Levin shovels sand over and over into a suitcase while extolling the virtues of work. Unable to be with the man she loves, Anna repeatedly knocks back vials of morphine signalling her spiralling addiction to the drug.

La Boite’s A Beautiful Life by Michael Futcher and Helen Howard was based on the Iranian embassy riot in Canberra in 1992 and the ensuing court case. In an attempt to speak back to calls for refugees to assimilate into Australian society, the writers interrogate the way in which culture indelibly inscribes the citizen’s body, particularly through imprisonment and torture. They argue that it isn’t possible to simply shrug off one set of cultural inscriptions, values and experiences and to assume another. Given the importance of such a project, the script for A Beautiful Life still needs further refinement. The focus for the performance should have remained, as it began, on the son of adults arrested in the riot. Born in Iran and brought up in Australia, he acts as a point of translation between 2 very different and distinct cultures. His struggle to understand his parents’ and his own position within Australian society would have provided a better treatment of the dramatic idea than the long exposition of the family’s life in Iran or the lawyer’s slow dawning realisation of the links between justice, economics, trade and diplomacy.

A strong tradition of storytelling continues to be nurtured by Brisbane’s Kooemba Jdarra. The company’s festival piece, Black Shorts, presented 3 short plays by new Indigenous playwrights from around Australia. Glen Shea’s Possession (dir. Lafe Charlton), Jadah Milroy’s Jidja (dir. Margaret Harvey) and Ray Kelley’s Beyond the Castle (dir. Lafe Charlton) represented a range of Indigenous experiences and perspectives and, in the diversity of stories told, engaged a broad audience.

Possession is a clever piece of writing that unravels to reveal a particularly shocking incident, which scarred the members of one family. The play explores the impact of incest (father-son) on the lives of 3 siblings, 2 brothers and one sister. It delivers a jolt to the audience’s sensibilities as we are forced to witness the elder brother’s fierce anger, the younger brother’s utter shame and humiliation and their sister’s desperate attempt to hold onto some semblance of a vital, young life in the making. Towards the end of the play, even this possibility is foreclosed as we learn that the characters inhabit the spirit world, having been hung for the murder of their father.

A devastating performance by Margaret Harvey as the sister in Possession was followed by her directorial debut in Jidja, a compact piece of writing, weaving a number of stories into the tapestry of an old, Aboriginal woman’s life. From a chair centre stage in a house bordering the Catholic home she was sent to as a child, an old woman (played by the accomplished Roxanne McDonald) tells her life story directly to the audience as if we are old, intimate friends. She remembers her happy early years, living together with her sister, bought up by their grandmother. She recounts her grandmother’s death, the girls’ placement in a Catholic home, and her life long search for the sister she was separated from when she was adopted out to a white family. In this piece it was the performer’s warmth and friendly intimacy as she related what was a tragic, yet not uncommon story, that I found disarming and extremely upsetting.

Attitude by Expressions Dance Company and Hong Kong City Contemporary Dance Company, Streb by the Elizabeth Streb Company and Arrêtez Arrêtons Arrête by the Mathilde Monnier company were major works included in the festival Dance program. Of the 3, the French production, created for the 1997 Montpellier International dance festival, was the most engaging and exciting. Elizabeth Streb’s choreography lacked the texture that Streb claimed for her work when she said that it investigates “the tension between volition and gravity imposed by structures which are at once physically confining and liberating.” Attitude, choreographed by Maggi Sietsma, explored images and vignettes taken from the different cultural histories of her dancers through a combination of sound (music by Abel Vallis), image (video projections by Randall Wood), and dance. Sietsma used the space creatively, choreographing the dancers on multiple stages. But she was unable in the end to meld her ideas and these different performance media into an integrated dance work or to achieve the audience interaction that the opening scene—a ‘Simon says’ routine—attempted. Integration was one of the main strengths of Arrêtez, Arrêtons, Arrête.

Mathilde Monnier’s choreography for 8 dancers was accompanied by a live monologue written by Christine Angot (an English translation was provided in the program), performed by a comedian. The text addressed the difference between the beauty and balance of dance and the ugly, obsessive discipline of the dancer. Set in the round, the dancers and comedian performed in close proximity to the audience creating a continuous space between performer and spectator. The comedian spoke in an intimate tone and addressed the audience directly. The performers also interacted with the set itself, a simple steel frame held together with suspension cables which made it an extremely flexible structure that moved with their bodies as they pushed or crashed against it. Monnier’s choreography consisted of a series of singular repetitive gestures, which signified individual everyday obsessions. Through this the dancers suddenly found openings into more expansive movements, usually performed in pairs. With the tension between the opposed pairs of light and shadow, text and movement/gesture, space and set, performer/dancer and audience, Monnier and her company created a complex and confronting work that addressed the inner struggle to move through self-imposed confines.

Queensland Theatre Company, Beaumarchais, The Marriage of Figaro, Optus Playhouse, Sept 3 – 19; Shared Experience Theatre, Anna Karenina, Suncorp Theatre, Aug 28-Sept 6; A Beautiful Life, La Boite Theatre, Aug 28-Sept 12; Kooemba Jdarra, Black Shorts, Metro Arts Theatre, Aug 28 – Sept 5; Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, Institute of Modern Art, Sept 1 – 6; Expressions Dance Company and Hong Kong City Contemporary Dance Company, Attitude, Conservatorium Theatre, Aug 28 & 29, Sept 1-5; Streb, Suncorp Theatre, Sept 15-19; Mathilde Monnier company, Arretez Arretons Arrete, Conservatorium Theatre, Sept 11 – 16;

RealTime issue #28 Dec-Jan 1998 pg. 8

© Kerrie Schaefer; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

“You give and give and give, and so take all I have.”

Paul Kelly, Generous Lover

My Father’s Father’s House

http://members.xoom.com/olande/callahan2/index.html [link expired]

My Father’s Father’s House (writer Terry Callahan, designer Jamie Kane) uses frames and simple diagrammatic plans to navigate a couple’s relationship breakdown and the negotiation, renovation, of space and desire. The house on the street. What the neighbours see. The cars that cruise by on Sunday morning. Click on the picket fence to delve deeper into the black and white sketch. What’s going on inside; isolation on a busy road. As we enter the gate, we cross the border between public and private space. A house, made up of squares, built with his father’s father’s hands, a house where his wife crosses boundaries many times.

A couple with no children, resigned bitterness like dust in the air. As we click on hallway, verandah, bathroom, kitchen, bedroom, the house itself becomes a character; occupied, wooden, threatened and old but still more alive than their slowly disintegrating love:

The house breathes, aches, lives. Cracks its joints. The still supple timber adjusts to the shifting balance of my wife and I, the furniture. For all its plumb squareness and dead levels, there is a reassuring give, a making of allowances.

His wife, an engineer who “can talk stressors and turning movements until [his] head hurts”, demolishes and renovates, threatening his identity and connections with the past:

Handed down by the words of fathers.

Expectation.

Nails in.

A portrait on the wall. Still

Grasping at something intangible.

A child’s bedroom.

Hammering it home.

We gradually move inside the house, into the subconscious, into the world of unrealised dreams. His wife becomes radical. She has layers of plans with pent-up meanings. She becomes eroticised by change, she seduces him, she wants to knock down walls: “Her timing was impeccable. Three o’clock when all my defences are down and her feather fingers on my right buttock. I didn’t hesitate.” Who’s in control now? as he listens to her movements in the house, tracking his lover by creaks and sighs

They wear each other down, sawdusting away intimacy, erecting new traps for entanglement; she wants one room to be a rectangle. She wins arguments by agreeing with him, her needs escalate, he becomes displaced: “But we don’t need it. Not anymore. You sleep with me now, remember?”

Like the house, he can adjust to her rhythm, straining and giving, bathing in the warmth and lingering light of her handiwork. Like the house, he can learn to become exposed.

RealTime issue #28 Dec-Jan 1998 pg. 16

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Place, London

In May 1998 The Place theatre closed for renovations. Thirty years after it opened, this national powerhouse for contemporary dance takes a breather from the headlong growth which has kept it at the forefront of developments in this comparatively young art-form. While the history of The Place traces a rather adhoc, opportunistic growth pattern, it is fair to say that in these harsh times for the independent arts in Britain its role as a beacon for innovation has never been more solid.

Practically every dance artist in the UK has passed through the swing doors of the old school building in Euston. Even those in far-flung corners of Scotland and Wales, loath as they are to recognise the benefits of the capital’s concentration of talent, will have made the trip to catch one of the world-class performers which this unpretentious stage attracts.

An award of £5.081 million from the National Lottery will transform The Place without changing its role or raison d’être. While the battles to raise the necessary £1.7 million in matching funds rage in campaigns of seat-selling and corporate events, the everyday life of the building races along with its usual erratic energies.

As a National Dance Agency, The Place has both a national and regional role. Arts Council funding for the network of NDAs supplements regional funding to encourage diversity and distribution of dance across the country. As the big brother of the newer NDAs and regional dance agencies, The Place tends to pioneer schemes which are then replicated at a regional level.

The Associate Artists scheme is such an example of best practice. Two part-time administrators manage a pool of emerging artists from well-equipped offices at The Place. Providing a liaison, as much moral as practical, these professionals support the inevitable self-management of young, under-funded artists. Office equipment is supplied free of charge and the artists are also able to draw upon the pool of experience located in the management of the resident companies in the building.

While VTol, Second Stride, The Cholmondleys and the Featherstonehaughs may have gone, Random, Bi Ma and Shobana Jeyasingh Dance Company all remain and Richard Alston, artistic director of the School runs his highly successful middle scale company from The Place. Resident artists teach at the school, contribute to special projects and perform in the theatre, generally adding to the sense of The Place as a home for dance artists at every stage of their career.

In the theatre office, director John Ashford heads a team of resourceful managers in the programming of the varied seasons by which The Place stimulates London’s dance audiences. Evolving over time, these initiatives remain fresh through Ashford’s international contacts, which enable him to confidently experiment with his programming. The Turning World, the annual showcase for non-British work, has introduced now familiar names like Vicente Saez, and continues to provoke with cutting-edge artists from across the world. While larger companies such as Les Ballets C de la B perform at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, The Place’s excellent 300 seat theatre provides an intimate setting for artists such as Sacha Waltz.

International artists return to The Place on 2 more occasions in the year. In the autumn Dance Umbrella, London’s largest dance festival programs the Place, alongside Sadler’s Wells, the Southbank Centre and Riverside Studios. Dance Umbrella also features British artists and The Place runs a complementary Dance on Screen festival for work on film during this period. Since 1994, The Place has simultaneously played host to the Digital Dancing festival of dance and technology experimentation, providing a venue for telepresence events such as Susan Kozel’s Angels and Astronauts 1997 performance across remote spaces.

In Re:Orient, The Place programs a week of Asian dance, presenting companies from across the region alongside British artists with Asian roots. This ambitious venture struggles annually to survive, but remains a source of singular pleasures, with productions from artists such as Japanese Kim Itoh selling out year on year.

The Spring Loaded festival, again in partnership with the Southbank Centre, presents the best of new British work at the middle scale. A balance between established companies such as Yolande Snaith Theatredance and lesser known companies such as Bedlam is carefully struck to give a unique snapshot of the current state of the artform in Britain. Every effort is made to include companies from the regions and the event is a highlight for regional promoters who often fill their seasons from Ashford’s selections.

Before Spring Loaded comes Resolution! the forum for new work, which is open to those with no professional experience and encourages experimental, mixed media work as long as movement is a major component. Resolution! operates a box-office split for the 3 companies performing each night and supplies technical and promotional support to the fledgling artists. A real mixed bag, Resolution! is nevertheless renowned for its rollercoaster extremes. Highs and lows. Recently the season has been broadened to include 2 new and complementary strands. Evolution features companies returning from earlier seasons and Aerowaves presents international work of a comparable standard. Mixing the 3 strands into each evening builds audiences by spreading the risk of what is always an intriguing gamble.

Alongside all this performance, The Place supports the creation of new work. Studios are hired to artists and projects such as the annual Choreodrome offer space at a reduced rate as well as mentoring and documentation of the creative process to selected artists through an application process. Workshops run on an ad hoc basis, with recent offers including video production with Elliot Caplan, independent US filmmaker of Cunningham fame.

Dance Services, which manages projects for professionals at The Place, operates a membership system which provides a monthly news magazine, Juice, an enquiry service for funding and performance opportunities, a library of periodicals and reference material, and advice surgeries for artists and administrators alike. In conjunction with Dance Services, the Video Place keeps an archive of work on film and records every performance at The Place as well as offering reduced rate recording services.

The London Contemporary Dance School keeps the cafe smoky and loud as students from all over the world work hard in intensive terms, benefiting from the teaching of Richard Alston and professional guest teachers. LCDS provides a 3 year full-time vocational training in contemporary dance and has nearly 170 students in diploma, degree and postgraduate courses. 4D, the graduate performance group of the school charges students to tour tailor-made work by a range of choreographers, gaining a sort of apprenticeship to the professional life.

Education and Community Projects is a small unit which offers high quality teaching and special projects to schools across London. Operating a database of contacts for the sector, E&CP is a state-of-the-art resource to the community and produces videos, teachers’ packs and support material for dance in the curriculum. Special needs groups are serviced by experts and projects—such as the recent White Out initiative with over 200 boys from London schools–are unprecedented examples of the ambition of the unit. The Evening School offers classes at various entry levels to the general public, regardless of age or experience. Each year, 13,000 individuals attend classes at The Place and 31,000 attended performances in the theatre in 1997. The Young Place offers an early introduction to dance training and the Youth company for 13-18 year olds meets twice weekly to make performance works.

The Place has come a long way since philanthropist Robin Howard bought the old schoolhouse in 1969 and invited Robert Cohan of the Martha Graham Dance Company to set up the London School of Contemporary Dance, from which emerged London Contemporary Dance Theatre. Artists such as Siobhan Davies, Rosemary Butcher and Ian Spink launched their careers to small and excitable audiences at The Place, then and now, the only theatre in England dedicated year-round to the presentation of dance. With the extended studio space, new catering and administrative facilities and enlarged stage, the Place looks set to take the millennium in its stride, slotting back into the changing dance provision of the capital without missing a beat.

Changes are afoot due to the national Lottery as venues line up to grab the fast dwindling cash for capital. This Autumn the new Sadler’s Wells opens with a fanfare program of greats, the Laban Centre begins its refurbishments and Greenwich Dance Agency puts in its bid for growth. A new rehearsal venue comes online at The Jerwood Space and Siobhan Davies Dance Company evaluates its lottery-funded feasibility study into the acquisition of a purpose built rehearsal and office space. The Peacock Theatre continues to program commercial dance and The Barbican nurtures its developing relationship with dance with an invitation to Merce Cunningham’s company. As debate rages over the Royal Opera House and the future home of the Royal Ballet, the precariousness of The Place’s ambitious target for matching funds seems pleasantly achievable and quite in context with a tradition of upheaval and innovation.

RealTime issue #28 Dec-Jan 1998 pg. 36

© Sophie Hansen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Michele Barker & Anna Munster, The Love Machine

Honest to God, if I hear the ‘m’ word one more time, I’m going to have a cartographic seizure. Since the early 80s when Fredric Jameson conflated pomo angst with an inability to represent the reconfiguration of spatiality, cultural production has remained in the thrall of the map. The ‘will to cartography’ describes the dominant critical stance informing a broad range of cultural practices, aesthetic commentaries and emergent social sites. One thinks immediately, of course, of all those energetic efforts to map, navigate and chart the spaces of post-corporeal digital existence. Yet it has to be admitted that there are some environments where a spot of mapping comes in handy: bioethics, new reproductive technologies and the Human Genome Project. A preoccupation with the logic of maps reflects our current fascination with borders and boundaries, interface and intersection. What constitutes the inside and outside of the body has become increasingly problematic for cultural commentators, scientists, media theorists and artists. And what might be the consequences of transgressing or mutating these limits was the subject of a recent Experimenta Media Arts event held in Melbourne, Viruses and Mutations.

Curated by Keely Macarow, the event brought together a diverse group of academics, genetic scientists, bioethicists and artists. Produced with the assistance of Cinemedia, Viruses and Mutations was part of the Melbourne Festival Visual Arts Program and consisted of three interrelated projects: a one-day cultural symposium, an exhibition—with works from digital artists and medical industry professionals—and a website. These three elements offered a way to critique and represent the issues that are generated when aesthetics, science and technology clash.

Indeed, a number of the contributors to the exhibition seemed quite keen on collision narratives. One of the most intriguing, albeit disquieting, installations imagined biotechnology as an aircraft crash. Called Cotis Movie (‘Cult of the Inserter Seat’ and ‘Mechanism of Viral Infection Entry’) this digital sound installation, by the international artist collective KIT, used medical scanning apparatus as a metaphor to trace all kinds of worrying links between bodies, technology and virology. Activated by one’s own body—you had to get up on a little stage and sit in a simulated aircraft seat to start the show—Cotis Movie constructed an environment of uncomfortable immersion and somatic pain. I mean this quite literally. The sound sculpture created by the three speakers surrounding the aircraft seat, reverberated in a way almost too painful to bear. A frantic voice screeches “we’re going down”. Seated in front of a screen you read that the Cotis Movie scanner has, apparently, located your vulnerable point in order to implant a virus. A tad apocalyptic? Well, yes. And this is what makes Cotis Movie a troubling encounter. If mapping has captured the cultural imagination, then the millennial discourse of the virus is no slouch either. While tropes of infection and viral transmission are made to stand for a plethora of cultural phenomena or transformations (malfunctions in computer software, popularity of theory in literature departments and so on) those with actual, material bodies infected by viruses continue to suffer. We ought to be a little cautious when the representation of illness appears to articulate a kind of techno-sublime: “the intended outcome of the Cotis Movie is an aircraft crash—which in this case suggests a mutated body—a body fused between technology.”

Theorising the body as a site for technological intervention—as collision, fusion, transgression or intersection—concerns a number of the other works in the exhibition. Justine Cooper’s digital video, Rapt, for example, imaged the artist’s own body to explore the effects of biomedical technology on corporeal understandings of time and space. The Tissue Culture & Art Project (reviewed in the Oct/Nov issue of RealTime) by Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr used living tissue to ‘grow’ a conceit about the relation between process and product—life and artificiality, art and science. The Love Machine, an installation by Michele Barker and Anna Munster, aimed to “represent the hybridity which computer imaging makes possible between technology and flesh.” This exhibit mimed the logic of a photo booth; that is, it simulated a particular kind of photo booth that the artists discovered in Japan and Hong Kong which takes a photograph of a couple and then digitally predicts and delivers a picture of the offspring. For Barker and Munster the structure provided a way to speculate about notions of definitive biological origin, ambiguous identity, authenticity and digital modes of reproduction.

In this regard The Love Machine dealt with what a number of commentators identify as a deeply significant paradigmatical alliance of the second half of this century: genetics and cybernetics. From the 1950s, information theory and cybernetics began to inform the knowledge production and scientific practices of molecular biology. Heredity was to be understood in terms of information, data, sequence and code. So organisms became informational patterns, data transmitting devices, nodes of input and output, modes of retrieval and archival. Fahhhbulously sexy and no wet patch. The disappearing material body, notions of genetic determinism, post-human subjectivity and a realignment of the mind/body dichotomy, can be seen as a function of the relations between genetic research, information theory and cybernetics. These developments have, of course, been well theorised by a range of quite different thinkers such as Donna Haraway, Arthur Kroker (natch) and Jean Baudrillard. What’s interesting about The Love Machine is the way it reinvests the argument with a lesbian polemic, questioning the technological essentialism of the body-as-information trope.

I read a comment that encapsulates a key theme of the one-day symposium. When asked about the ethical implications of genetic engineering, Francis Crick (who, with James Watson, discovered the double helical structure of DNA) is supposed to have remarked something along the lines of ‘social concerns are quite nice but let’s worry about them after we’ve made the scientific discoveries.’ (Or, to borrow that god-awful Kevin Costner line, “if you build it he will come.”) While the conference provided a forum for interdisciplinary rapport between scientists, cultural commentators and artists, there was little movement around or departure from some fairly traditional theoretical positions: those of the ‘Crick school’ and those opposed. One of the most interesting exchanges occurred during question time between feminist lawyer and publisher, Dr Jocelynne Scutt, and Professor Grant Sutherland head of the Department of Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics at Adelaide Women’s and Children’s Hospital. Sutherland felt it was ‘up to the community’ to decide about the applications of new genetic engineering technology while Scutt urged scientists to locate themselves more self-consciously within these techno-scientific discourses.

Along with issues of technological determinism, key areas of debate concerned the ethical, social and political implications of gene patents and the Human Diversity Project, gene therapy, genetically engineered foodstuffs, detection of the so-called gay gene, in-vitro fertilisation, and genetic screening. This last point was discussed by a number of the speakers. Both Bob Phelps (director of the GeneEthics Network) and Dr Udo Schuklenk (Monash University’s Centre for Human Bioethics) spoke passionately and eloquently about the degree to which the ability to predict or detect genetic based disease could witness institutional discrimination across the fields of education, employment, insurance and health care. Universal health care was seen as a crucial issue because those who are identified as ‘at risk’ for certain genetic conditions might be unable to secure private health insurance.

It’s become almost commonplace to characterise our cultural moment as one preoccupied with the signifier over the signified, with the medium over the message, the map over the terrain. Viruses and Mutation sought to be situated somewhere within this pattern of signification. Both the conference and exhibition were very much concerned with exploring the tropes and iconography of biotechnological research, while emphasising the interdependence of the material and the semiotic, metaphor and literal. The exhibition was, after all, held in a conference centre called The Aikenhead.

Experimenta Media Arts, Viruses and Mutations, curator Keely Macarow; exhibition, Aikenhead Conference Centre, St Vincent’s Hospital, Fitzroy, October 19–31; symposium, State Film Theatre, East Melbourne, October 24; website: www.experimenta.org

RealTime issue #28 Dec-Jan 1998 pg. 24

© Esta Milne; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lucy Francis, Virgin with Hard Drive

The inaugural Brisbane-based Multimedia Arts Asia Pacific 98 Festival, directed by Kim Machan, puts Brisbane once more in the regional ’hood. As the locus for the Asia-Pacific Triennial and with a run of cultural and artistic exchange projects and events, Brisbane is emerging as not just a port-of-call, but a site of connectivity. In its first incarnation, MAAP 98 aimed to create the infrastructure and provide scope to accommodate technology-based artworks, exhibitions and projects from the region.

The web provided the necessary ‘links’ which ‘maaped’ the Asia-Pacific in a series of flows: images, sounds, commentary and texts. Further engagements and interactions with online, screened, exhibited and performed work and texts provided us with the hyper- and inter-textual awareness that helps us understand this region as fragmented complexity. The hardrive grinds as it struggles to download sites and plug-ins. Perusing loses that luxuriant, ambling quality. We wait rather than take our time as sites download in random splinters. Hitting a site scripted with Java…” System Error 11—Restart.” Even so, these works are worth the wait.

You have to wonder, if we’re having trouble (albeit on an older Mac) in a city in a country that has consistently prioritised telecommunications, how do you manage in downtown Kendari (given the west’s penchant for ‘dumping’ outdated technology)? Perhaps this will be addressed in future MAAPs whose vision is also to create a nexus between community, artform and the multimedia industries. Perhaps as well, these questions may be contextualised by the Australian Network for Art and Technology as it develops and re-negotiates strategies for its 1999 program focus, Digital Region. Certainly, these (and other) concerns and ideas were discussed by various speakers at the festival’s Think Tank forum.

As these speakers pointed out, electronic media are capable of carrying many messages, in many ways and to many audiences. Clearly, information technology is located differently across cultures inspiring suspicion and wariness in some contexts. However, for most Australian practitioners, this technology is generally perceived as capable of providing the context for new possibilities, exchanges and meanings. It is this capability which locks us into the myth about a box from antiquity which stores hope. For example, Brisbane school children participate in environmental awareness-raising through video and performance, conveying their concern about pollution levels in the air we breathe. Working with George Pinn and Jeremy Hynes, these students give form to SMOG. The open-air presentation of this work, after a number of speeches, formed the opening night event. The festival’s impressive list of sponsors bodes well for new media arts securing support from the corporate sector. Or, does it merely reflect that multimedia industries know the value of audience development as a factor in demand creation and parts of the Asia-Pacific are demand waiting to happen?

Lehan Ramsay & Hiroshi Yasukawa, Resonance (detail), Shoreline exhibition, 1998

So really, you do have to wonder. You have to wonder what kinds of hierarchies are being established or what new colonisations or postcolonialisms are sweeping through the region when a significant proportion of it has been declared ‘developing nation’ (and with that, there is most likely disproportionate representation in the ranks of the ‘information poor’). For all the talk about new media providing a new horizon for democracy, as a transference of hope, it is nevertheless a democracy with steep entry levels. But what has this to do with MAAP 98? Perhaps nothing, perhaps everything. At the core of such political dilemmas is the question, ‘who speaks for whom?’ However, in video works sourced from Malaysia, Japan and Hong Kong those speaking positions and their differentiated voices and contexts are made explicitly clear.

The digital domain seems partly surrounded by a permeable membrane that, while defining its territoriality, underscores the commonality and almost ubiquity of creative endeavour. Despite these flows, the imposition of the rectangular frame around these images and concerns is a continuation of the traditions we love and loathe. In MAAP 98 we are presented with a range of collaborative works—interchanges back and forth—such as Resonance in Shoreline: Particles and Waves http://www.maap.org.au/shoreline [link expired] curated by Beth Jackson. As a virtual gallery, Shoreline presented seven works by nine artists from Australia, Japan, Hong Kong and New Zealand. Utilising the metaphorics of the littoral, these works operate at the limit of the virtual ocean, testing seemingly given notions about art as it moves with the tides of interactivity, information and multimedia.

Equally we are witness to idiosyncratic (almost demagogic) posturing and preening in the Eurocentric tradition with some of the 160 exhibited entries to the National Digital Art Awards organised by and presented at the Institute of Modern Art. Yet counter to this, and within the same show, are spectacular advances in visualisation, and the overall winner, Justine Cooper’s video, Rapt (see RealTime 27, Colin Hood, “Between professional diagnosis and dumb fascination”), using medical imaging technology, takes the human corpus as site and perhaps uses as a currency for the region, corporeality of endeavour. Other place takers were John Tonkin’s web based artworks [http://207.225.33.116 – link eexpired] and Norie Neumark and Maria Miranda’s Shock in the Ear. Despite the significance of this event in terms of promoting new media arts, its scheduling saw it competing with the rugby league grand final, resulting in a city-wide shortage of electronic equipment. While the IMA gathered whatever was available at short notice, there were varying degrees of success in terms of technological reliability; no wide screens and no instant replays.

Not having much luck with machines, we ventured towards less technologically contingent works and environments. At the Brisbane City Council Gallery, an exhibition of photographic and digital images by Robyn Stacey, curated by Frank McBride, provided close and closer scrutiny of flora in a series of optical illusions and manipulations. It is another overture by which we ‘know’ and reveal nature via technological means. A multimedia installation, Virgin with Hard Drive by Lucy Francis at Metro Arts, revealed a story set in the future exploring art, the artefact, conservation and decay.

Culture is notional, flowing across the nations of the region. Taking the fragrance or stink out of the localilty means we are able to enjoy tourism of the highest order. You can stay at home and, server willing, it all comes to you. However, this is not passive; this is not broadcasting. A different mode of engagement is demanded as the work whispers or screams into you ears and eyes; there is no false sense of security when a system or an economy crashes. IT is other: IT is heaps and heaps of others and you are both component and resident of this Tower of Babel, adding your voice to the many as the cacophony catches just long enough to allow a double click to next frame.

Multimedia Arts Asia Pacific Festival 98, Brisbane, September 18–26, online at http://www.maap.com.au

RealTime issue #28 Dec-Jan 1998 pg. 20

© Linda Carroli & John Armstrong; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Murray McKeich, Memory Trade

There is hype and there is cyberhype: what distinguishes the latter from the former is its exponential quality. It is hype about hype itself, and it ramped up so fast in the 80s and 90s that it ended up pointing straight up, like a giddy soundbite version of John Glenn’s space shuttle launch.

Cyberhype, as Darren Tofts writes, was the consensual cliché of the times. Everything was digital, hyper, info, multi, techno, cyber, as if the whole world was about to go through some kind of gestalt-snapping paradigm shift right before our eyes. But as Michel Foucault once reminded us: perhaps we are not really living through revolutionary times. Perhaps this moment is just a coffee break in history—and a decaf coffee break at that.

As challenging as it may seem, this is one way to read Darren Tofts and Murray McKeich’s Memory Trade: A Prehistory of Cyberculture. McKeich’s Photoshop art, in particular, gives a somewhat scary flavour to the notion that the transformative power of technology, to remake who we think we are and can be, has always been part of what it is to be human. Or in other words it is the inhuman in us that makes us human—our capacity to become otherwise makes us always other than ourselves. If this is so, then the hubris of cyberhype gives way to something darker, to technofear. If this is not the first and only great revolution in our being, that we can’t really be sure who or what we are, going in to this next transformation.

Tofts argues that there are silent antecedents for the information revolution. He wants to map a possible history of what came before it. Or rather, a prehistory: “histories record: prehistories invent.” It’s a matter of assembling, out of unlikely elements, a working model for history itself.

Central to Tofts’ prehistory is the concept of cyberspace, which he calls “a tantalising abstraction, the state of incorporeality, of disembodied immersion in a ‘space’ that has no coordinates in actual space.” William Gibson named it ‘cyberspace’, and imagined how it might look 15 minutes into the future. Tofts asks rather about its 2,500 year past.

It’s a widespread perception that “community no longer conforms to the classical notion of a group of people living in a fixed location.” But did it ever? The idea that, as I’ve put it before, “we no longer have roots, we have aerials” and that “we no longer have origins we have terminals”, may in a sense have always been true. We can read in books or on websites about mythical, organic communities that existed always in some once-upon-a-time, but the very act of reading about such a world is the mark of our distance from it.

That there was always and already a ‘cyberspace’, without which there is no concept of history, is, as Tofts says, “a dizzying abstraction to grasp.” The trouble is that we humans are so embedded in communication technologies that they seem like second nature to us. Or perhaps they seem, to use a term of mine that Tofts borrows: a third nature. Humans build a physical environment more hospitable to them, and this becomes a second nature. Humans build an information environment more hospitable too, and this becomes a third nature. Only these new worlds don’t just make our old selves more comfortable, they transform what it means to be human.

Murray McKeich, Memory Trade

A characteristic of cyberhype is the idea that the old communication technologies are alienating, but the new ones will restore us to a whole and organic way of life —what Marshall McLuhan called the global village. From Tofts’ point of view, this fantasy starts to look like exactly that. There is no Adamic pre-communicational world to return to. There is no millennial transformation in the offing. Rather, the relationship between culture and communication is a matter of permanent revolution.

Tofts is also sceptical about all of those books that announce the end of the book, and all the cyberhype about hypertext, as if clicking a few buttons on the screen could revolutionise the act of reading or writing. Reading is always hypertextual. This is obvious to anyone who has ever picked up a nonfiction book, scanned the index and the contents page, and then accessed the information in the order of their choice. Only fools with brains addled by an unrelieved diet of novels could ever fall for this nonsense about the book being ‘linear’ and computer based hypertext ‘nonlinear’ or ‘multilinear.’

To dispel some of the cyberhype, Tofts embarks on a prehistory of cyberspace that looks at 3 of its dimensions. He examines the history of writing, the construction of abstract spaces, and the invention of technologies of memory.

Writing is a technology. The way people who use this technology think and feel is just not natural. Tofts acknowledges the hostility of some of the more hide-bound lit-crit crowd to thinking deeply about this, but really writing is just one of a series of technologies that have transformed how humans think and feel, and transformed what it means to be human.

There is something inhuman about writing. The act of externalising sense, making it something cold and hard and apart from a human body, is downright weird. For Tofts, writing is where cyberspace begins. With writing, it is possible to detach human thoughts, feelings, expressions, from the time and place of their creation, and transport them to another time and place.

Even stranger, writing does not just externalise something human into something inhuman. It also does the reverse. Strange gaggles of abstract signs, little squiggles marked on a surface of stone or wood or paper, suddenly speak to us in our heads, addressing us and making us pay heed. How strange this is! A human who may be miles away, or may even have been dead for years, is making meaning inside me. Writing, in short, implicates any reading human in an inhuman world, a world where stones and leaves speak to us in our own language.

One of the reasons what were loosely called ‘poststructuralist’ theories of writing aroused so much misunderstanding is that they were often very much about this strangely inhuman side of the way writing works to make meaning. But this is really not a new concern. Tofts revisits Plato’s Phadrus, one of the first texts in the western canon to express an intimation of technofear, the disquiet caused by the inhuman side of technology. The irony is that while Socrates and his mates appear to discuss things like writing as a matter of conversation between humans, it is through the inhuman form of Plato’s written text that they ‘speak’ to us.

What is this strange space within which the dead and distant can communicate with us? It is cyberspace—and we’re already in it. As Tofts writes: “Literacy involved a series of subliminal acts that invoked a virtual space of shared meanings and understandings, the ambience otherwise known as communication.”

Following Derrida, Tofts argues that anything that can be the object of perception in this internal space is ‘virtual’. “The virtual is the link or bond that unifies our experience of the world and our conceptual understanding of that experience.” I think this is rather too restricted an understanding of the virtual, a reduction of a more sublime phenomenon to a special case. In Deleuze’s understanding, virtuality is a much broader category of radical possibility.

All the same, there is plenty to think about in terms of the radical possibility for otherness in human existence that Tofts assembles in his prehistory. Writing is just one instance of a technology, or group of technologies, that provide for an encoding of information in a more or less permanent and stable form, external to the body, which creates a time and space of sense making beyond the scope of the body, and which in turn invades and transforms the body, making it over into a machine for producing and reproducing communication.

While cyberhype wrongly sees the current crop of technologies as something more than an incremental development, it would also be an error to dismiss the current moment of extension and transformation of cyberspace altogether. Tofts identifies one particular key change: “The shift, within technologies and economies of memory, from the specific location that contains a finite archive of knowledge, to decentred networks of ambient information, requires a new metaphor to facilitate social orientation to the changing role of memory and memory trade within the information economy.” A new metaphor, or perhaps a new practice of thinking, both within and about the communication process.

Tofts stresses that the act of making meaning always takes place somewhere. This, for him, is the significance of Plato’s cave: representation always unfolds within a space. The space he proposes for rethinking the current state of third nature is James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, a text notable for its “ecology of sense” of the media world. Following Beckett, Tofts sees Wake as a writing that is not about something, it is that something.

A great one liner: “the pun is the nanotechnology of literature.” It sums up what it is about Wake that makes it such a radically virtual space. In Joyce’s book as in Murray McKeich’s art, anything and everything can be transformed into anything and everything whatever. Here is that space Burroughs announced, where “everything is permitted and nothing is true.” I think Finnegans Wake is less a metaphor for cyberspace in the 20th century, than a metonymic part of it. It is a richly complex part of a space in which humans find themselves, immersed in the noise of what Joyce called the “bairdboard bombardment” by the “faroscope” of TV.

Tofts is here sufficiently past the now unworkable orthodoxies of structural and poststructural semiotics to show why those theories have now to be surpassed. “To be immersed in information is to be information, not a sender or receiver of it.” The ‘linguistic turn’ posited a separate world of signification, which represented a world of things external to it. Poststructuralism undid the assumptions of such an epistemology from the inside. But it’s time to move on, and one of the joys of Tofts’ prehistory of cyberspace is that it lays some conceptual and historical groundwork for thinking media theory free from the limiting assumptions of poststructural dogmas. But it does so by pursuing poststructuralism to its limit, rather than by retreating from it.

“Any use of technology modifies what it means to be human”, Tofts writes—in full recognition that the technology of writing in which this expression appears is also included within its scope. It’s not enough to write about the technology of writing, or of communication in general, as if from without.

Writing is the key to Tofts’ prehistory of cyberspace. Cyberspace “continues the ancient project that began with the introduction of writing, whereby proximity was no longer a defining characteristic of communication between human beings.” He is aware that architecture and transport also play a role in this transformation of the relation between near and far, living and dead, but I think there is more to be said about this vectoral side of the prehistory of cyberspace. Tofts has more to say about the codes of encryption than the vectors of distribution of the memory trade, and these are I think complementary areas of research in contemporary media theory.

Cyberspace is an ongoing revolution, not one that restores a lost world, but rather one that carries us further and further from ourselves, differentiating the future human from the past human by inhuman means. Cyberspace “threatens to transform human life in ways that, at the moment, are still the province of science fiction.” But, increasingly, also the province of media theory.

What I think distinguishes contemporary media theory from, say, poststructuralism, is a much more critical relation to the means of communication within which theory itself forms and disseminates. As such, Darren Tofts and Murray McKeich have made a valuable contribution to an emergent field. The irony of course is that rather than recycle outdated ideas in fancy computer hypertext, they have come up with an original way of thinking and writing the world in the familiar form of the book.

Darren Tofts and Murray McKeich, Memory Trade: A Prehistory of Cyberculture, 21•C/Interface Books, Sydney, 1998

RealTime issue #28 Dec-Jan 1998 pg. 17-

© Dr McKenzie Wark; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Maria Fernanda Cardoso, The Cardoso Flea Circus

Touring the globe in search of the ingredients for the cultural pie that is the modern city’s festival of arts, balances personal influence with the grind of corporate travel. Our very own Robyn Archer exposed some of the vices in this inexorable progress recently at the Museum of Sydney. In between the streaming succession of meetings, performances and phone calls, she escapes to, well, the local museum. Whether Mexico, Bolivia, Sweden, Austria, Holland or Taiwan, assemblages of humanity’s artefacts can be found that go far beyond being “merely entertainment.” Such institutions and theme parks she felt, “will have their day.”

The spectre of the museum as a sculptural shell into which the musty remnants of earlier ages are placed was in question here. Site-Time-Media-Space were the sectors of ‘the museum context’ explored by a range of speakers assembled by the creative director of CDP Media and prime media designer for the venue itself, Gary Warner, “…to stake a claim for the exploration of poetics and design, the advocacy of play, curiosity and wonder…” The experiences of museum specialists who work with media technologies (and the research of artists who produce content with them) formed the substance of the seminar.

SITE …we enter its walls leaving the everyday behind to enter a microverse of contrived tableaux, of intellectual conceits and the frisson of play between certainty and ambiguity, credulity and propaganda…

Susan Alexis Collins, from the Slade School in London, demonstrated the webspace interventions that she makes into street life, ranging from sound and imagescapes in a tunnel under the Thames, to a moving mouth on the pavement of a city street. Linked to a website (www.street/gallery), internet surfers are invited to select mouth movements and spoken phrases to be delivered to passers-by on the other side of the world/road. The sense that these become intrusions into streetlife (observed and measured by a hidden surveillance camera) exemplified the confrontational, and attenuated her attempt at communication of a most basic kind, a prerequisite for even the most experiential museum.

“Garrulous media installations…” were far from Ian Wedde’s mind when as Concept Curator Humanities for the recently opened Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongerewa, he was part of the large team who sought to “find, win and grow a new audience” for Our Place where the collections were to be utilised as a unified resource. The ‘Disneyfication’ criticisms and the demonstrations around the Condom Madonna (part of the Pax Britannica exhibition that stopped off in Wellington after leaving the MCA in Sydney) were enough to attract the crowds in numbers that far surpassed original estimates.

Facing It is the section of Te Papa that commissioned media art from around the world. In a series of extended apologies to potential Australian contributors whose email had gone unanswered, Wedde outlined the rollercoaster he had ridden for the past years around “the rocks of management.” The curator as heroic figure emerged, as contracts were issued to the lucky few “to extend artists’ practice and placing risk-management at the feet of the institution”. The risks paid off and the work of Lisa Reihana among many others, for modest cost, resulted in a photo-based exhibit using historical and contemporary photographic images made in Samoa. The response? The Samoan community are each day encamped within the exhibit.

SITE …Display Technology is becoming a material that can be used to directly address the environs outside the gallery walls…Digital media systems will be devised to react to vectors such as crowd movement, meteorological conditions or the sound of traffic and so become dynamic, destabilising and revelatory…

The complex issue of resourcing specific media projects emerged. Bricks, concrete and salaries are less of a problem than accessing the technology and project budgets. Wedde advocated “relationship brokerage” as the method by which artists, institution and sponsor could collaborate to produce museum outcomes. The issue of curatorial objectivity and discretion was left to another time.

TIME …rituals of delay can be quite pleasurable, or, at the very least build anticipation and create the conditions for narrative, drama, comedy and insight…

Installation artist Maria Fernanda Cardoso has reintroduced the tradition of the live interactive booth to the museums of Europe and America with The Cardoso Flea Circus. In this ‘side-show’ concept complete with tent and circus mistress Cardoso, nothing is virtual, all is real, including the feeding of the fleas on the proprietor’s arm.

Touching steel, steering a submersible, and feeling the roar of an oil platform through your feet was the tangible introduction to the Oil Museum in Scotland, one of several new museums in Europe described by Stephen Ryan. The Creation of the World exhibit at the Natural History Museum in London was an example, of how—not surprisingly—a big budget and too many hi-tech resources can lead to lack of clarity and excessive maintenance costs. Avoidance of disruption is thus another measure of design success.

MEDIA …the creation of memorable media experiences, the crucible of memory being the experience of difference…

Jon McCormack’s long-term project with The Museum of Artificial Ecologies will become a public museum with a collection ‘comprised only of software’. In tracing toward such a place we were led past the reputable (celebrated) Osmose by the Canadian Char Davies and McCormack’s own artificial life projects, and through the many intrigues and ironies of ‘escaping the container’ of the frame and the glass cabinet found in so many museums and theme parks, and were entreatied to agree that object-based museums obscure asking the questions “Who are we?, “What are we?”

SPACE …cumulative spatial mapping—the gradual understanding of the often complex spatial relationships that grows out of exposure to a variety of orientation inputs, some planned many unplanned—graphical, sensorium, aural…

Matters of the spirit were raised by Paula Dawson for St Brigids Church, Coogee, Sydney. The Shrine of the Sacred Heart was opened a year ago as a three-dimensional space within which holographic images are sited. Developed during a research period spent in part at MIT Media Lab, the copper vapour laser transmission holograph enables the parishioner to place their hands in prayer into the image space that simulates 3 visions associated with the Christ figure. Dawson’s superbly delivered and illustrated presentation allowed for the patent irony of a non-believer becoming the re-inventor and interpreter of spiritual and devotional practice, re-exploring the smoke and mirrors of inclusive performance in the service of belief. A project involving advanced technology, this was the best example in the seminar of the kind of quantum leap that museological circles need to make, to recapture the imagination and the passion of museum audiences in the service of meaning and knowledge.

Site-Time-Media-Space—New Media in Museums , a seminar, convenor, Gary Warner, Museum of Sydney, October 17–18.

RealTime issue #28 Dec-Jan 1998 pg. 21

© Mike Leggett; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Joanna Pollitt, Par Avion

photo James Kerr, courtesy of The Mercury

Joanna Pollitt, Par Avion

Hobart’s new performance group Avanti describes its debut production Par Avion as “a multimedia navigation of three passengers suspended in flight.” It is an ambitious production which attempts to make “big screen video projection and live contemporary dance performance blend together…”

The work explores on screen and on stage the briefly parallel trajectories of 3 people seated together on a flight from Melbourne to Hobart; at the same time it endeavours to fuse video and dance into a unified form of communication and reflection. Franc Raschella has a good eye for composition and montage; at times the beautifully shot video imagery functions to background the subtext of dance and motion, whilst at others it leads the story very clearly. The choreography is driven by a turbulent and spiralling force which maintains the primary characters in a state of either colliding or slip-streaming, thereby demanding a precise and very physical performance which Joanna Pollitt, Michael O’Donoghue and Kylie Tonellato deliver with accomplishment.

In its best moments the production succeeds

in achieving a sensation of intimate intersection between the world represented by the video narrative, and the physical world of the live dancers and audience. Unfortunately there were also times when the video narrative was overly complex, and subsequently the visual disparity between the 2 channels of the performance meant it became difficult to follow. Blending video and dance is a difficult balancing act to maintain, and it is a credit to Avanti that it has the vision and courage to do so.

Avanti, Par Avion, devised, produced and directed by Joanna Pollitt and Franc Raschella; performed by Joanna Pollitt, Michael O’Donoghue and Kylie Tonellato, director of photography Franc Raschella, choreography Joanna Pollitt in collaboration with Michael O’Donoghue and Kylie Tonellato, music composed and performed by Imogen Lidgett, Peacock Theatre, Hobart, Nov 12 – 15

RealTime issue #28 Dec-Jan 1998 pg. 35

© Martin Walch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lisa Ffrench, Territory

photo Heidrun Löhr

Lisa Ffrench, Territory