Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

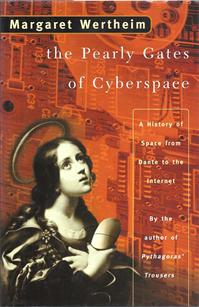

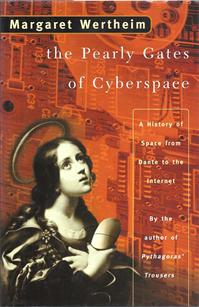

Cyberspace is the ostensible topic of this book. It is really a kind of Cook’s tour of space as it has been conceived and visualised through the ages, from the soul-space of Christian theology to the hyperspace of multi-dimensional physics. It is important to keep any discussion of cyberspace within a historical framework and Wertheim has done an admirable job in providing an extended cultural history into which cyberspace can be situated. Her argument is a fairly simple one and, as the title of her book suggests, it measures cyberspace against a quasi-Christian view of space as being transcendent, immaterial and other. “Cyberspace is not a religious construct per se”, Wertheim suggests, but “one way of understanding this new digital domain is as an attempt to realise a technological substitute for the Christian space of Heaven.” There is nothing particularly innovative about this suggestion, as cyberspace has been theorised elsewhere as a “spiritualist space” (Michael Benedikt’s “Heavenly City”, William Gibson’s Vodou pantheon in Count Zero). What perhaps is new is the sociological spin Wertheim puts on the emergence of cyberspace at the end of the 20th century: “Around the world, from Iran to Japan, religious fervour is on the rise.” But Heaven is something to be put off for later, so I will return to this issue directly.

Cyberspace is the ostensible topic of this book. It is really a kind of Cook’s tour of space as it has been conceived and visualised through the ages, from the soul-space of Christian theology to the hyperspace of multi-dimensional physics. It is important to keep any discussion of cyberspace within a historical framework and Wertheim has done an admirable job in providing an extended cultural history into which cyberspace can be situated. Her argument is a fairly simple one and, as the title of her book suggests, it measures cyberspace against a quasi-Christian view of space as being transcendent, immaterial and other. “Cyberspace is not a religious construct per se”, Wertheim suggests, but “one way of understanding this new digital domain is as an attempt to realise a technological substitute for the Christian space of Heaven.” There is nothing particularly innovative about this suggestion, as cyberspace has been theorised elsewhere as a “spiritualist space” (Michael Benedikt’s “Heavenly City”, William Gibson’s Vodou pantheon in Count Zero). What perhaps is new is the sociological spin Wertheim puts on the emergence of cyberspace at the end of the 20th century: “Around the world, from Iran to Japan, religious fervour is on the rise.” But Heaven is something to be put off for later, so I will return to this issue directly.

How has the West configured space? This is the question that shapes Wertheim’s discussion and the book is structured around a series of discrete moments in the history of space. It is a very linear, tidy history, beginning with the theocratic world-view, as articulated by Dante and Giotto, which, via the Copernican revolution, Newtonian mechanics and Einsteinian relativity, incorporates the outer reaches of contemporary cosmology. As earthbound physicists such as Stephen Hawking contemplate the infra-thin spaces of quarks and virtual particles, they once again turn our attention to the sphere of abstraction that exists beyond the physical world-view that has dominated consciousness since the Enlightenment. Wertheim’s contention is that with cyberspace we have returned to a realm not dissimilar to the Medieval conception of “Soul Space.” Consistent with the transcendent motivation of this space of spirit, Wertheim refers to “cyber-immortality and cyber-resurrection.” Enter the “cyber-soul.”

There is a certain kind of logic in Wertheim’s account of a re-emergence of a conception of space that dominated an earlier age. However I have a number of problems with her anachronistic misuse of cybercultural terminology. For instance, Dante does not represent himself in The Divine Comedy as a persona but as a “virtual Dante”; the Arena Chapel in Padua is a “hyper-linked virtual reality, complete with an interweaving cast of characters, multiple story lines, and branching options” (the italics, which are telling, are not mine); Medieval thinker and theologian Roger Bacon was “the first champion of virtual reality.” To be fair, such throwaway lines detract from what are otherwise interesting discussions of the ways in which the techniques of representation yielded to the pressures of verisimilitude and the desire to create in the Medieval viewer/worshipper a more vicarious sense of presence, of actually being in the scene or space being described. This is in itself a fascinating issue, for as writers such as Stephen Holtzman and Brenda Laurel have suggested, VR concepts such as immersion have a respectable ancestry and their logic has hardly changed. This doesn’t give us licence, though, to return to the Middle Ages armed with cyber labels for our predecessors and certainly not with such abandon (The Divine Comedy “is a genuine medieval MUD”). Giotto was without question a pioneer in the “technology of visual representation.” He was not, though, our first hypertext author. We can perhaps claim that there was something hypertextual in the way the narrative is presented in the Arena Chapel, but we have to evaluate this against the rigid, hierarchical manner in which the Medieval mind read the world. Wertheim is sensitive to this, but fails to account for it adequately. She also fails to note that just because we have hypertext it doesn’t follow that it represents an episteme or way of seeing that residents of the late 20th century all share. Most visitors to the Arena Chapel today would more than likely read its narrative as a causal sequence of events. More to the point, they would presume that there was one.

The other major problem I have with Wertheim’s argument is the contention that cyberspace is “ex nihilo”, a “new space that simply did not exist before.” Contrary to Wertheim’s surfeit of space, I simply don’t have the space to take issue with this position. However as a statement it points to a worrying element of contradiction in her argumentation. In the same chapter we are informed that with cyberspace “there is an important historical parallel with the spatial dualism of the Middle Ages” (we are also informed that television culture is a parallel space or consensual hallucination and that Springfield, the hometown of the Simpsons, is a “virtual world”). In a book that attempts to synthesise such parallels and account for cyberspace as a return to a Medieval type of space, it is odd to read in the penultimate statement of the book that “Like Copernicus, we are privileged to witness the dawning of a new kind of space.”

The book is very distracting in this respect and it testifies to an unresolved tension within Wertheim’s assessment of cyberspace. While she is sensible and articulate in her delineation of space as it has been figured throughout history, she is still caught up with the novelty not of cyberspace, but of cyberspeak. There is not enough analysis of what type of abstraction cyberspace involves and how we actually relate to it spiritually or any other way. Too many of the familiar themes of cybercultural discourse are simply recapitulated, such as the possibilities for identity and gender shifting in MUDs, the liberatory potential for “cybernautic man and woman”, of avatars and interactive space and the hackneyed whimsy of downloading the mind into dataspace—et in arcadia ego. Any force that is generated by Wertheim’s main theme is lost as a result of the book’s straying off into the already said. How is data-space like the Christian concept of Heaven? This is an interesting question, but beyond the tropes of cyber-dualism and cyber-transcendentalism; nothing original in the way of a convincing answer is forthcoming.

The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace is consistent with much cyber-utopian criticism in its evaluation of cyberspace as a positive, therapeutic phenomenon: “There is a sense in which I believe it could contribute to our understanding of how to build better communities.” Well, I suppose we are still waiting to see if this will be the case or not.

In the meantime, how do we account for the fact of this new space? In response to this question, Wertheim advances her least convincing argument. Unsupported by any research and reliant entirely on speculation, Wertheim suggests that at a time of global religious enthusiasm “the timing for something like cyberspace could hardly be better. It was perhaps inevitable that the appearance of a new immaterial space would precipitate a flood of techno-spiritual dreaming.” As sociology The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace just doesn’t cut it. Despite the reservations I have with the book, it is nonetheless a useful study of the contemporary fascination with space and the historical legacy of Christianity, the history of ideas and the visual arts.

Margaret Wertheim, The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace, A History of Space from Dante to the Internet, Doubleday, 1999, ISBN 0 86824 744 8, 336 pp.

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 20

© Darren Tofts; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

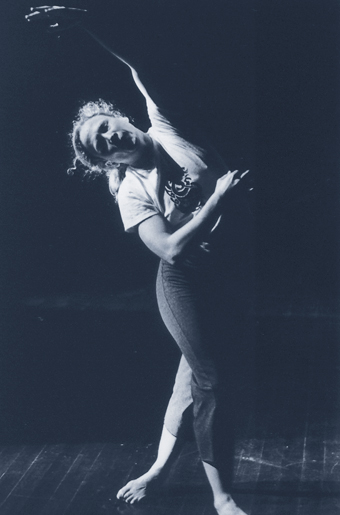

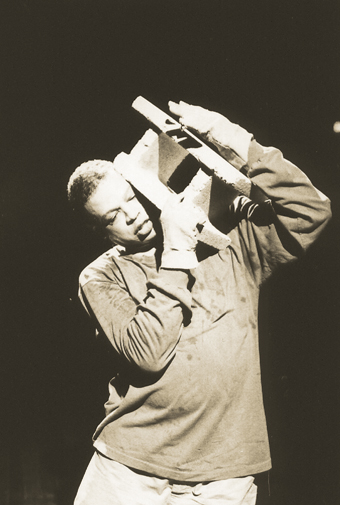

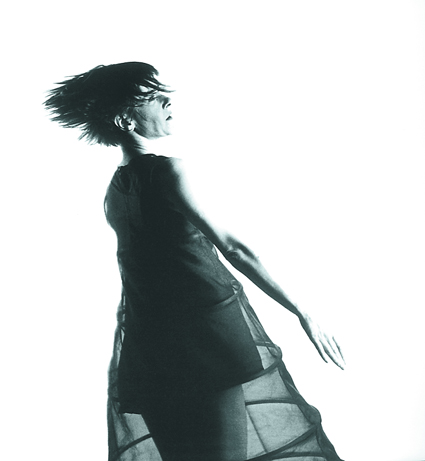

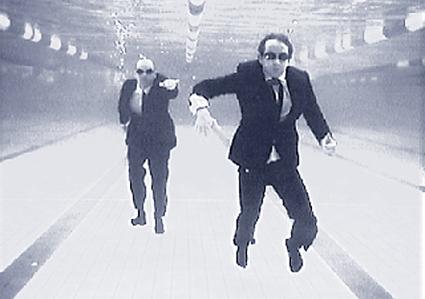

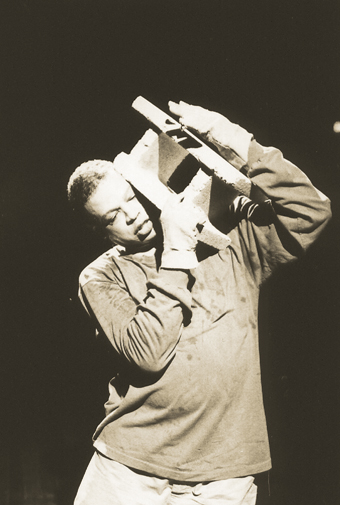

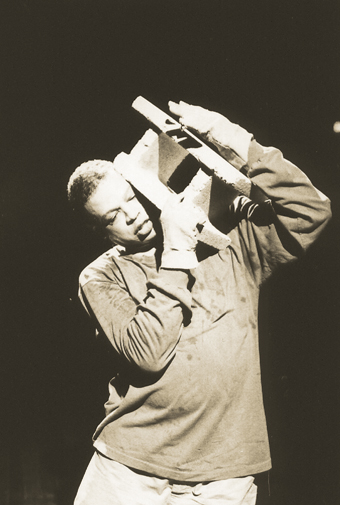

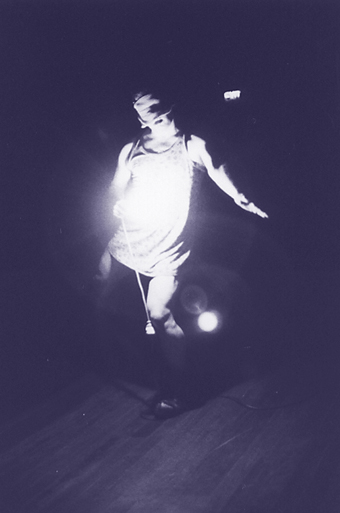

Ishmael Houston-Jones, Without Hope

photo Mark Rodgers

Ishmael Houston-Jones, Without Hope

antistatic 99…on the bone put on substantial flesh (the programs were labelled Femur, Clavicle, Axis, Atlas and, interestingly for the contemporary performance component, Spur) over its 3 weeks with performances, installations, talks and workshops, bringing a welcome intensity and added intelligence to the Sydney dance scene. Guests from the USA and Melbourne added bodies and dance cultures in perspective. As you’ll read, a few observers and participants thought antistatic’s focus somewhat narrow, ‘homogenous’, lacking in ethnic and aesthetic diversity. In the case of Ishmael Houston-Jones’ querying the cultural breadth of the event, he applies the word festival, which in fact might not fit the event model of antistatic with its focus on very particular dance issues, forms and, inherently, independents and their innovations (as opposed to, say, MAP’s deliberate coverall approach in Melbourne in 1998). For all of its probing, essentialist leanings, antistatic nonetheless displayed some remarkable hybrids, artist and reviewer anxiety over text spoken in performance was much less in evidence than a couple of years ago, and collaborations with composers and lighting designers had clearly made considerable progress with greater integration and dynamic counterpointing of roles. antistatic might not have been a festival in the conventional sense, but it certainly was a feast. Appropriately, one of its highlights was an on-the-floor meal and discussion shared by performers and audience on the penultimate evening of an intimate and open dance event.

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 10

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ishmael Houston-Jones, Without Hope

photo Mark Rodgers

Ishmael Houston-Jones, Without Hope

Eleanor Brickhill asked Ishmael Houston-Jones about his impressions of antistatic 99.

I often feel like a member of a band of vagrant minstrels, criss-crossing the worldwide countryside of postmodern dance. We steal into a town, dance for our supper and a place to sleep, and then move on. Because the friendly villages are few and well-known to members of my merry band, we invariably run into each other at semi-regular intervals. I might see David Z in Havana, then David D in Glasgow; I’ll have a dance with Jennifer M in London, and the other Jennifer M in Northern Venezuela; I’ll watch a performance by Lisa in Arnhem, and she’ll watch my dress rehearsal in Sydney. This has been my life for 20 years.

Of course New York is my home. It’s where the answering machine is. It’s where the cheques with a variety of postmarks come. It’s a city that inspires and drains me. It is a city, however, that will never support me, nor the majority of my downtown dance compatriots. Thus roaming from small festival to small festival has become a necessary pleasure for survival. While the road can sap as much energy as being broke and over-stimulated in Manhattan, it does make it possible for me to make my work.

In April 1999 I travelled midway around the world to take part in the second antistatic festival in Sydney. As a safe haven for dancing, this turned out to be a welcoming and genial way station. The production of my performances at The Performance Space was done with exacting professionalism combined with compassionate attention. The programs were well curated. While audience size varied, it was clear that the organisers had done a lot, through receptions, an attractive flyer and other publicity, to bring out the New Dance public in Sydney.

The workshop I taught, “Dancing Text/Texting Dance”, were well run by antistatic. It attracted a near perfect assortment of those interested in sharing my process for the 2 week period. The “dancing paper” presented by Susan Leigh Foster was thought-provoking and added a context for the work that was being presented and taught. The events attracted (curious) reviews in the mainstream press.

As an antistatic participant, I feel the main fault of the festival was its overabundance. During the 3 weeks, there was very little downtime or space for processing. With workshops running 5 days a week for 6 hours a day, and a variety of shows, showings, lectures etc taking place in the evenings and all weekend, I often found myself feeling tired and stretched (or guilty for skipping out on an event). This may have had to do with the fact that this was my first journey to Australia, and I wanted to get a little sight-seeing and night life into my itinerary. Also suffering from this being my virgin voyage Down Under, is my ability to adequately critique the breadth of the local work. The program of which I was a part also featured pieces by fellow New Yorker, Jennifer Monson, and the Melbourne duo, Trotman and Morrish. This program was varied in its scope within the narrow frame of “new dance.” The works evocatively contrasted one another, while they seemed to accidentally provide some complementary subtext for the evening.

The works on the following weekend were a different story. Although Lisa Nelson is from the United States and Ros Crisp is from Sydney, several of my students described the program as a “very Melbourne evening”. While the works varied greatly one from another, they had a disquieting similarity of tone. I found this to be most true with the “the gaze” and how it was used, or not used. Except with Nelson, the only non-Australian on the program, there seemed to be a determined effort to not acknowledge the audience through any overt eye contact. This lent an air of “art school lab experimentation” to several of the pieces. Again, I’m not sure if I’ve seen enough local work to justify even this stereotype, but this inward focus did seem to be a less refined echo of the performance personae of Russell Dumas’ dancers, whom I saw as part of antistatic at The Studio at the Sydney Opera House.

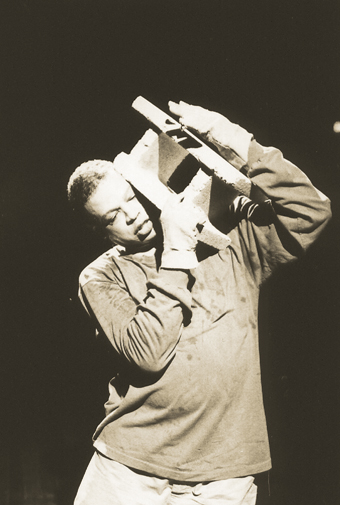

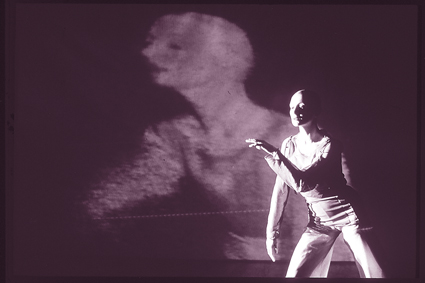

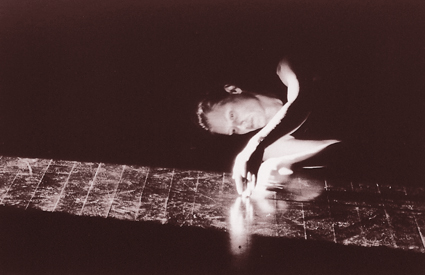

Ishmael Houston-Jones, Rougher

photo Mark Rodgers

Ishmael Houston-Jones, Rougher

What I found different about antistatic, as opposed to, say, The Movable Beast Festival in Chicago, was its lack of both artistic and ethnic diversity. In 1998, at Movable Beast—a small festival of new dance in its second year—I performed 2 of the same pieces I did at antistatic. But while there was an emphasis on “pure movement” pieces, there were also works that veered toward performance art, multimedia spectacle, spoken word, drag, cabaret, and site specific. The latter 2 genres were encouraged by having multiple venues for the festival. While the main performances took place in a traditional black-box theatre, each festival participant was required to also present “something” on a tiny stage in a jazz club between sets, and also to make a site specific work for the Museum of Contemporary Art’s 24 hour Summer Solstice celebration.

Another difference was that all performers taught, and there was a lot less teaching by each person: 2 days apiece for the visitors; one day for the Chicagoans. While this greatly lessened the intensity of the workshop experience, it did allow for the participants to take one another’s classes, and for the students to get a taste of many different approaches to making work. I think something between the antistatic workshop stream in which a student signs up for one teacher for the entire 2 week period, and the Movable Beast’s workshop sampler would be preferable.

A striking difference between the 2 festivals was in their ethnic make-up. This is influenced by my American perspective, but it is not likely that such a festival in the States would ever be as “white” as antistatic was [Yumi Umiamare and Tony Yap were also antistatic participants. Eds.]. There were no international artists involved with Movable Beast, but besides myself, there were African-American, Asian-American and Hispanic artists teaching and performing. Several were gay. The teacher/performers came from 5 states outside Chicago. Like the audiences and artists of new dance, the majority of workshop students were white, but there was some ethnic diversity in most of the classes. While I try not to place an over-arching significance on these statistics—and of course I realise the demographics of the 2 countries are very different—I still feel that some creative outreach to different populations allows a festival to be more richly diverse and less restrictively insular.

antistatic was a very positive experience. It allowed me to present my work through performing, teaching, and discussing it with a new community in a very nurturing environment. It can only get better as a festival by widening its embrace of new dance.

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 14

© Eleanor Brickhill; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

antistatic as a whole event exposed, problematised and critiqued the current and ongoing negotiation within dance between movement and words. This project has become central to new dance practices and is a significant area of investigation which dance is pioneering within the broader context of the performing arts. The relentless necessity to reveal dance—to provide commentary on the display—described by Lisa Nelson and the newer necessity for the community to move from the defensive and assume its role as innovator in this regard, could be traced through the festival from Foster’s experiments combining movement improvisation and empirical discourse, to Monson’s incoherent vocalisations in Keeper, to the very format of this eclectic event.

The last day of antistatic, Atlas, was like a culmination of this apparent, but perhaps implicit theme. A combination of performances (incorporating texts, choreography and or improvisation), presented papers and the less easily defined “performed commentary” by Julie-Anne Long and Virginia Baxter, exposed most lucidly the curators’ task. How can dance remain the primary discipline, its conditions and knowledges the most influential forces, when combined with discourse and all this entails? To slide across types of language, methods and modes of performance provided the curators with one answer.

While Anne Thompson used language and theory (particularly psychoanalysis) to consider a notion of spectatorship (in which she found empathies with contact and ideokinesis) in relation to the work of Pina Bausch, Yvonne Ranier and Robert Wilson, Sally Gardner probed the implications of language itself in relation to government peer assessment documentation to ask Can Practice Survive? Gardner described the Australia Council’s “philanthropic” activity as creating not a shelter from the mainstream marketplace, but a new economy, which deals in reductive terms: “innovative”, “independent”, “creativity”, “pioneering.” She provided an interesting alternative economic option; rather than putting money into publicists, why not just pay the audience directly?

References to Australia’s lack of historical context for terminologies such as those outlined above circled back to a notion of Australia as suffering from a condition of “lack” or “ignorance.” Surely official language cannot represent the actual situation within which work is produced and received in any country. Performance aritist Mike Parr, in challenging the academic approach of Thompson’s paper to Bausch’s work, assumed, I would argue incorrectly, that most audience members had never seen her work live. Russell Dumas, in a later session, revisited this subject of context and Australian audiences by criticising the “guru” status he believed antistatic’s visiting artists to have been granted. The arguments represented here are recurring within the dance community and assume a condition of inadequacy in our audiences and practitioners, which in turn suggests an authority “elsewhere.” Such assumptions stagnate discussion and progress by rendering the majority of participants deficient.

A later discussion grouped together 3 practitioners whose solo works were performed as part of Axis; Eleanor Brickhill, Julie Humphreys and Susie Fraser. Unfortunately I missed Fraser’s piece, Stories From the Interior. [In this work-in-progress, Picking up the Threads, Susie Fraser retraces a dancer’s body changed by childbirth and motherhood. Her recorded voice speaks eloquently from a tape recorder. When asked afterwards why the speech is in the third person, she says “Sometimes it feels like that.” The illumination for her subtle movement comes from a video monitor running home movie footage. Meanwhile stretched across the back wall are the beginnings of her video manipulations into a painstaking choreography on the family from her place within it. Eds.] Brickhill provided the most satisfying combination of spoken word and movement in antistatic, The Cocktail Party. Her analogy of a party was accurate; she tentatively entered the space and presented a dance and a kind of commentary: “What is that…it looks important…why don’t you just say it…I know where that comes from…” A dance about making a dance, in her words. Words revealed movement revealed words in a moving and strikingly personal confrontation of the two. In the discussion Brickhill said she was “trying to write while thinking of dancing.” Fraser said she had tried “writing from movement” but “needed another pair of hands.”

Long and Baxter had the last say in event and left everyone speechless; an attempted closing discussion was aborted after valiant attempts from the Masters of Ceremony, Trotman and Morrish, which were met with a request for alcohol. The irreverent tone and attitude of Long and Baxter was a welcome change from the earnest intentions of the weekend, but their performance was an odd experience seated as I was between Lisa Nelson and Jennifer Monson who were not spared the duo’s humour.

What they dared to do was admit to other preferences within performance, both through their comments and their mode of delivery, which provided a healthy intervention within a relatively homogeneous festival. Not to deny the vast differences in the approaches of say Houston-Jones and Crisp, but antistatic engaged framing notions of dance which created an exclusive environment. Long and Baxter’s piece suggested other ways of dancing and performing which, at the same time, displayed a real engagement with the proceedings. A certain frustration was aired here but always with good humour, such as Long’s comments on the Clavicle program that it all seemed so “Melbourne” and her exposition of exactly what “doing a Dumas” entails. Even Russell Dumas was rendered speechless.

–

Axis: Susie Fraser, Stories from the Interior; Sally Gardner, “Can practice survive”; Julie Humphreys, Involution; Anne Thompson, “Rainer, Wilson and Bausch as markers in a mapping of the border terrain called dance theatre”; Helen Clarke-Lapin with Ion Pearce, Alice Cummins, Rosalind Crisp, Orbit; Eleanor Brickhill, The Cocktail Party; Julie-Anne Long & Virginia Baxter, Rememberings on Dance.

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 13

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The workshop showings were an appropriately informal affair and gave non-workshoppers an insight into the work of the 3 imported practitioners—Nelson, Monson and Ishmael Houston-Jones—who we had seen in performance and had been the focus of much discussion. The showings unfolded for the audience like a game of charades we were invited to view but not participate in; each artist had developed tasks, methods and rules that the viewer could attempt to decipher or merely watch the results of. The similarities and differences became striking.

Nelson was the first up and the ‘video’ commands she had used in her performance, Dance Light Sound, were employed here en masse, dancers either participating in the “stop”, “reverse”, “play”, “replace” commands or waiting and watching. The choice to participate or not became as interesting as the choices about moving, and the role of the ‘commander’ began to slide around the group. The dancers often had to move with their eyes shut becoming instantly tentative, exploring the space around themselves anew. The participants kept to the back of the performance space engrossed in the details of their tasks.

Monson’s group made more of a spectacle of themselves in the exciting way Monson can in her performances. The display of energy and contrasting dynamics were relentless and the participants completely engrossed. It was difficult not to follow Monson here whose self-confessed attraction to the comic had her flitting about the space in pseudo-balletic hysteria. There was an energy-engagement between the dancers and an awareness of the observers that sparkled with possibilities.

Houston-Jones’ group showing was an “almost-performance-piece” made up of a succession of ideas. Music was introduced to the proceedings (Ishmael giggled as he DJ’d behind us) and the dancers moved closer to the audience. Language was also introduced as something more than functional, introducing narrative and emotional registers, and was interrupted through yet another system of spoken commands (“shut-up”). Movements became correspondingly more gestural and scenarios appeared; the group posed for a camera, revolving slowly as they changed positions, drawing out the moment of ‘presentation’; a line-up of apparently expert botanists described their favourite flowers over the top of each other and the line began to sway organically.

–

Atlas: Workshop Showings, The Performance Space, April 10

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 12

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Elements similar to Susan Leigh Foster’s were at work in the set of events comprising Spur in which Tess de Quincey’s Butoh Product #2 – Nerve showed how to stare down a crowded room while text effects splashed around her, courtesy of performance poet Amanda Stewart’s textual montage and projection. In this as in other of Stewart’s works the sounds and images of words are collapsed back on themselves and we have the bare material of language on display. De Quincey worked within a similar paradigm to return the performing body to its being on stage. Standing squarely, facing off the spectators, holding ground until the impulse to move took over…a more powerful performance presence is hard to imagine and even without locomotive movement the pulses of the body’s capacities for movement are in evidence. Jeff Stein and Oren Ambarchi’s Aphikoman re-staged the audience/performer dynamic with a dada style theft of the performative moment. Hidden beneath the seating Stein stole personal objects, then dumped them on the stage forcing the spectators to leave the darkness and claim their property. This was done with great humour and energy which carried the concept along though there wasn’t much else to experience in this piece.

Alan Schacher’s spasmic movement piece came with an industrial noise sound track by Rik Rue. This was not a harmonious technoshamanic ritual but a pulverising attack on the body. Schacher’s body duly sought out dark spaces as if to hide from the technoscape which threatened it and emerged into the light only to express its crisis. This was a strong and unsettling piece which again revealed the capacities of body, light, sound to sustain an audience’s interest without the supplementation of excess effects. Yumi Umiumare and Tony Yap provided an antidote to the harshness of the Schacher/Rik Rue collaboration in a lucid and meditative dance in the TPS studio space. Commencing in a chair seated on top of one another the pair slowly extended past the flickering laser beam guarding their resting place and into the audience. Yumi’s laughter caught me by surprise but suggested that the human core in this work was at peace with itself. I noticed something I had missed in their earlier work which is that these 2 can control their movements and lyricise them at the same time in breathtakingly subtle ways.

Stuart Lynch closed the night with the equally breathtaking but totally unsubtle Without Nostalgia, a virtuoso piece staging, among other things, his concern with TBS (Total Body Speed) as the centre of the actions which determine his performance work. The notion comes from his connection (through De Quincey) with Mai Juku in Japan but also reflects the emphasis on speed in contemporary considerations of bodies (Deleuze) and culture (Virilio). It is spectacular to witness an artist engaging at this level with current theoretical debates in media and performance studies. I hope we get to see this piece in another context as it is packed with ideas that only a repeat viewing could adequately process. In a way this piece represents the opposite of Foster as a conceptual interrogation of cultural forms through movement and image rather than through text combining with gesture. Both are hybrid forms with a different emphasis but you wouldn’t want to do without either of them. The praxis of performance, which ever way you receive it, got a real boost from these events.

–

Spur: Tess De Quincey, Butoh Product #2 – ‘Nerve’; Stuart Lynch, Without Nostalgia; Alan Schacher with Rik Rue, Kunstwerk (Trace Elements/Residual Effects – part 3; Jeff Stein with Oren Ambarchi, Aphikoman; Yumi Umiumare & Tony Yap, How could you even begin to understand? Version 2, Antistatic, The Performance Space, April 4

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 11

© Ed Scheer; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

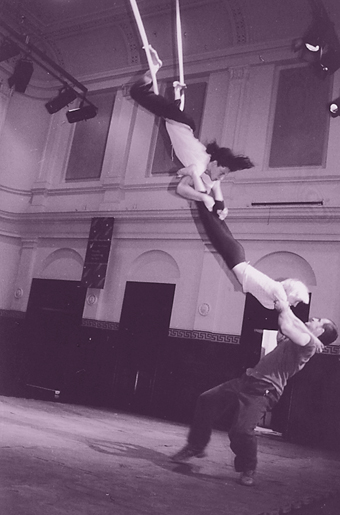

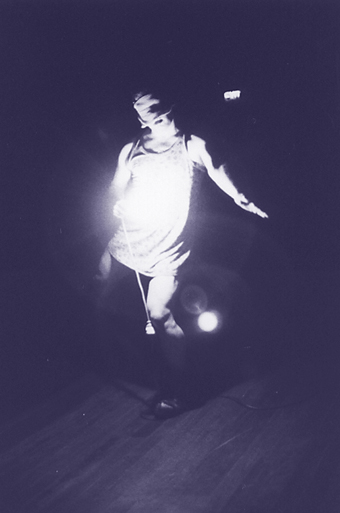

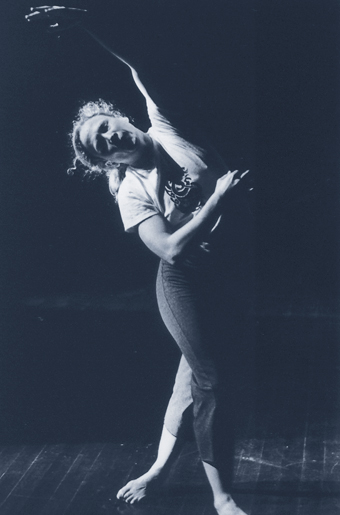

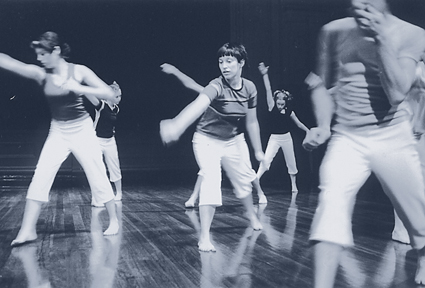

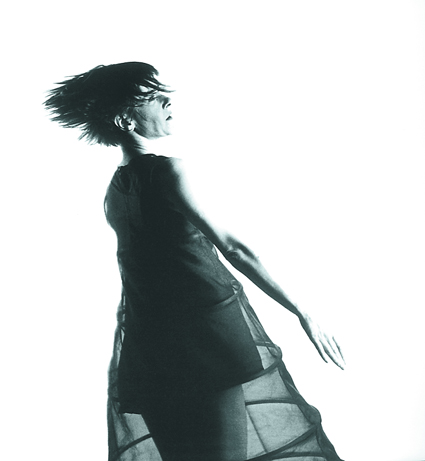

Rosalind Crisp, proximity

photo Mark Rodgers

Rosalind Crisp, proximity

These dancers seem to be moving away from those pleasantly concordant relationships particularly with sound and light design, of simple support and elaboration. In Clavicle, there’s a real hybrid growth in the fusion of those elements with choreographic design, so that new things are being said. Particularly in the first 2 works, original home and morphia series, the collaborations produced a brilliantly intense language of action and imagery.

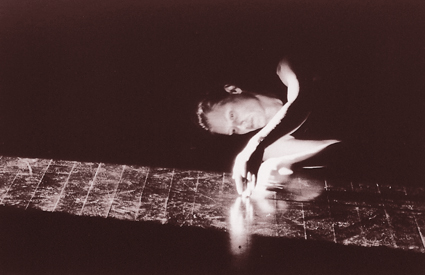

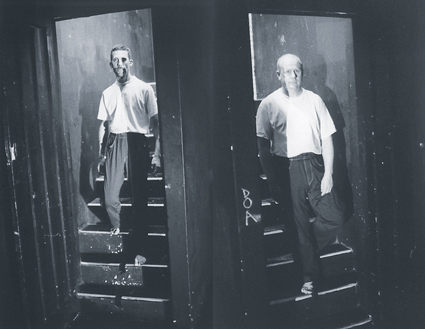

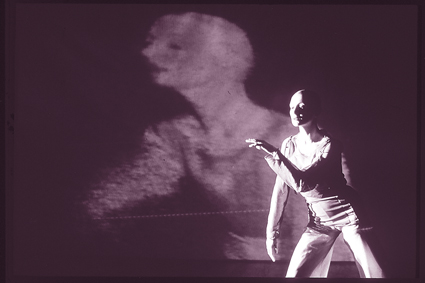

Inexplicably, I found myself describing original home as the South Park of dance, prompted by its oblique cartoonish humour, gangly truncated demeanour, randomised interruptions of gesture and dissipated gravitas. The performers seemed to have composed themselves accidentally in a hail of instruments, objects and events—a rock rolls off-centredly across the floor, small rattling gourds, snare drums, a bowling ball, a piece of rope, cymbal, a small one-stringed instrument, pieces of wood—all exquisite, self-made, found or outlived, dancing included, which spill over the stage with a tightly orchestrated nonchalance, into an endless array of both finely-tuned and careless disturbances of space.

In morphia series, there are sudden contrasts: black-out, yellow flames, black hair and fabric over white glowing skin, concentrated stillness and fast-forward flickering sequences. Ben Cobham uses the light source like a camera, producing grainy, black and white, film-like effects on the small framed stage, revealing Helen Herbertson’s actions with textural variations, sometimes thin and stiff, too fast, not life-like, or else the image appears as if through a window, with small inexplicable, ambiguous gestures, but solid and 3 dimensional. Is she repeatedly washing her hands or warming them by a fire? Sound seemed elemental: a tinkle of bells, rain on a roof, a single light clicks on, tiny bird calls, the click of fingers, once, twice; you might see her eyelash flicker; the soft billowing light of wind-blown flames.

In Lisa Nelson’s Memo to Dodo, it’s the seeing, the visual sensing, the cycling of perception in and out through the eyes that holds your attention. The audience is implicated in her dance, you feel; a strong link, but just what that relationship is, it’s hard to know. She is holding something firmly, placing it just right, sorting things, noticing in the periphery, perpetually catching sight of something in the light; small registers of awareness, working it like breathing. Not insubstantial space, but there’s something solid she’s making from what’s around her. She sends it back in direct and exact parcels of energy.

Another section, a voice playing an old game, telling Nelson to halt, continue, reverse, repeat actions, while still carrying on that breathing in and out of light and shadow as she moves: small deliberations, holding, placing, delicately weighting a stick in hands and arms, making the windings of her body around it sometimes difficult to undo.

Graham Leak & Ros Warby, Original Home

photo Mark Rodgers

Graham Leak & Ros Warby, Original Home

Compared to Nelson, Warby and Herbertson, Rosalind Crisp’s dancing in proximity is fluid, romantic, with a softly restrained dramatic abandon. There’s elegance in her physicality, and an emotional luxuriance more pronounced than in previous performances. Elegance too in Ion Pearce’s rarefied soundscape, dry and windy at first, but in the second section, strident, piercing. Simplicity and measure settle over the work, with a single stream of light falling across the stage onto Crisp’s moving hands as if they are in water. They seem close up, in focus. Later a handspan, 2 arms’ lengths, the reach to feet and floor. Like Nelson, Crisp works with her eyes, encompassing the details of limbs and what they surround: side by side, near and far, measuring the course of her action before she’s been there, and the traces she leaves behind.

Jude Walton’s Seam (silent mix) is full of white and black, a heavy curtain and white screen side by side, and shocking red splashes in the fabric of costumes. It’s full of text (Mallarme’s notes on the poem Les Noces d’Herodiade: Mystere) which I read long after the rest of the work was seen, and an echoing English/French vocal mix; it seems not designed for immediacy. Now I don’t recall the words. I recall how conscious I became of my own breathing as I watch a film of pinned paper seams pull and rip apart as my own ribs expanded, and edges reunited in relieved exhalation. I remember the luminous white foetus-like flesh of dancer Ros Warby, as she manipulated a tiny camera over her body, the image like an ultra-sound of something internal, soft and vulnerable, not quite formed. I remember her red dress against the black curtain, pulled back. I remember the ocean, washing over the screen in increments of flowing tide, rising higher and higher up the wall of the screen. We wait for the seam blending one wave into another, finally with a kind of inevitability, until the screen, and our minds, are somehow complete, the pieces put invisibly together.

–

Clavicle: Ros Warby, Shona Innes, Graeme Leak, original home (returning to it); Helen Herbertson, Ben Cobham, morphia series – Strike 1; Lisa Nelson, Memo to Dodo; Rosalind Crisp, Ion Pearce, proximity, sections 4 and 5; Jude Walton, Ros Warby, Jackie Dunn, Seam (silent mix), Antistatic, The Performance Space, April 1 – 3

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 10

© Eleanor Brickhill; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

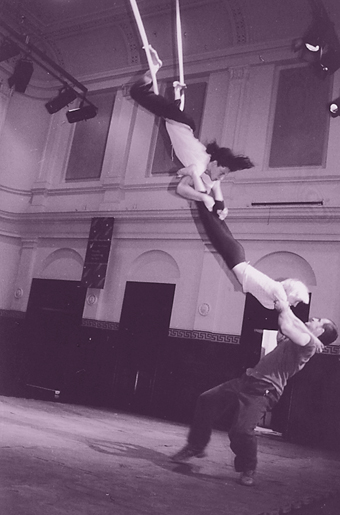

Georgia Carter, Jennifer Newman-Preston in Young woman glass soul

photo Debbie Taylor

Georgia Carter, Jennifer Newman-Preston in Young woman glass soul

Young woman glass soul is a multimedia work conceived by Jennifer Newman-Preston in which dance is the governing thread with puppetry, illusion, images, sound and words as integral elements: images are by Vinn Pitcher; words and storytelling by Victoria Doidge; music by Alexander Nettelbeck with vocal harmonics by Joseph Stanaway; projection by Tim Gruchy, video scripting and direction by Joanne Griffin. Young woman glass soul explores the Cinderella fable for contemporary resonances taking on no less than six versions of the story—the goddess Isis; a Brazilian fable in which a sea serpent plays godmother; a Cinderella variant in the context of a Muslim women’s ritual; the German folk tale of Aschenputtel or Ash Girl; Charles Perrault’s “The Little Glass Slipper”—commissioned by Louis XV—as well as the Walt Disney version. Young woman glass soul opens at Bangarra Theatre July 1.

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 36

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

As part of antistatic, choreographer-dancer Julie-Anne Long and I created Rememberings on Dance, a performed conversation in which we attempted to harness a little of the electricity generated by the event. Looking at the ways memory operates in performance and its reception by audiences, we began by admitting to personal lapses: when Julie-Anne is taken by a particular movement, she has a strong desire to see it again and finds it difficult to see the rest; whereas I retain overall atmosphere and feel but rely on conversation to recall precise moves. We spoke from a table covered with books (about memory and dance), notes, pens and markers. Julie-Anne had a knot around one finger with a large ball of string handy beside here. At one point she rolled up her sleeve to reveal more reminders scribbled in biro.

We began with “Doing a Dumas”, a conversation about Julie-Anne’s recent experience working on Russell Dumas’ Cassandra’s Dance which opened antistatic. I quoted Russell from an interview in Writings on Dance: “(The dancers are) not trying to produce how they’re being seen. The trick is to have the work just out of grasp so that the dancers’ focus is just on doing the task rather than displaying the task or mastery of the task.” In answer to my question about the task, Julie-Anne demonstrated a fragment of the process:

JAL “Well, okay, you might take a move like this (SHE LIFTS WEIGHT ONTO THE RIGHT LEG, LETTING THE LEFT LEG ROTATE BEHIND AND SWING BACK OUT TO THE SIDE). We’ll go over and over it for hours, days to learn where the weight is, how the muscles respond to this particular way of moving. The next day, Russell might come in and teach the move in an entirely different way as if the other had never existed.”

VB So you’re forgetting at the same time as working towards a deep memory of the moves…And is the audience witnessing your remembering?

JAL Once we enter the frame we concentrate fully on executing the task. The audience is peripheral.

Along with memory in performance, the idea of the audience and its acknowledgment in the works presented at antistatic became a focus for our talk. In “Susans”, we concocted a conversation which might have occurred following the performance of Ros Warby’s original home. The conflicting memories of 2 women with almost the same name competed with Dionne Warwick’s of Always Something There to Remind Me.

Susan: I felt I had entered some strange terrain in which time had stopped. The bodies had forgotten themselves. Movement was absolutely ineffectual.

Suze: I remember something unnaturally “natural” in which 3 performers were either totally uncomfortable or too comfortable.

Later I confessed to a theory I’d started hatching as I watched original home. One of the pleasures of events like antistatic is the opportunity to see a lot of work and suggest some connections.

VB When Shona Innes rolled across the floor and landed against the wall and seemed stuck there as though she’d forgotten what happened next I was wondering why dancers would be feeling forgetful about their bodies? Why now?

JAL Oh, I think they’ve been thinking like this for a while—too long I’d say.

VB Thinking what?

JAL How the dancing body feels to the dancer, simple as that.

The ensuing awkward pause in the conversation forced us into the next section, “Something else”, in which the hazy memories of one were prompted by physical clues from the other. The topic—Rosalind Crisp’s work proximity.

VB I took a friend who said to me afterwards—(SHE STOPS AND JULIE-ANNE GESTURES WITH HER EYES) “I’ve never seen a dancer so self-absorbed. She almost didn’t need an audience”…I was shocked. Then she said this didn’t mean she hadn’t enjoyed the work. On the contrary she admired the dancing…it’s strength and lightness.

JAL Why would that shock you?…The audience watches the dancer…(VIRGINIA FEELS HERSELF ALL OVER)…feeling how her dancing body feels to her.

In the same program, Lisa Nelson’s remarkable work Memo to Dodo produced more divergent memories.

JAL I couldn’t work out whether this was Lisa Nelson or a personification of something else. Was she looking at us, was she seeing us as those eyes shifted in and out of focus…

VB This one added some more to my theory. So did Ros Crisp’s “dead hand” as you call it. Lisa Nelson’s body looks like it’s asleep…it’s alert, then barely conscious, forgetful. It moves to instructions from an invisible presence on a crackly recording.

JAL The movement is expert but it has no ulterior purpose.

VB Meaning bounces round the room, just out of grasp.

(Later in the week, Lisa Nelson said of this work “My dances are vision-guided, not eye guided. At first I saw this as a way to flex my visual muscles and to stimulate the imagination in my body. The muscles, the lens—it’s the full orchestration. I just have tremendous sensation there. I always have had, ever since I was kid.”)

Jude Walton’s elegant Seam re-surfaced in slow stabs at memory—screen, film, pen, hand, writing, hysteria, translation, paper, pins, breathing, a body beneath, breathing, a curtain revealing, red, screams red, slip, screen, ocean, endless ending…

Whereas our memories of Helen Herbertson’s Morphia Series—Strike 1 tumbled over each other.

VB That sense of senses deprived. Forced to peer, squint into the dark, into the ghostly glow of the proscenium and…

JAL Love, love, LOVED the fire!

But when we tried to remember precisely—

VB Do you remember what Helen Herbertson was doing? How she was moving?

JAL (ATTEMPTS THE MOVEMENT BUT CAN’T CAPTURE IT). Whatever it was, I know I just loved it.

To elicit a bit more detail from our memories of the Femur program which featured highly memorable works by Ishmael Houston-Jones, Jennifer Monson and the improvising duo Trotman and Morrish we tried Lisa Nelson’s workshop technique in which dancers create complex improvisations triggered by a set of instructions (Enter, Play, Reverse, Repeat, Exit) called from the sidelines. We improvised with a set of sentences, discovering our memories of these works were less conflicting.

JAL They take the space. Demand our attention.

VB Her body is charged, circuits kicking in, synapses snapping. Body at full stretch.

JAL Presentational. Acknowledge the audience. The dancers stood in front of us. I settle when I feel that.

VB She goes about her work, as we watch. Like that song, “Busy doing nothing working the whole day through, trying to find lots of things not to do.” Occasionally she acknowledges us. Just enough. Dean Walsh swears she winked at him.

In the final sequence in the performance, “Butoh Memory”, we substituted objects on the table for memories of the performances in Spur.

JAL Needles in eyes (scissors).

VB Speed contained (a book of matches).

As we lifted each object/memory we placed it in a bag and left the room and the table empty.

As always, the conversation continues. Julie-Anne’s memories affect my own recall of antistatic as do other conversations had at and after the event. At the dinner conversation on the penultimate night, Lisa Nelson talked about the dilemma of people being able to look at dance. It’s “so removed”, she said. She thinks dancers need to re-invent, reframe the ritual and share some of the incredible things that happen in a dancer’s body-mind, to show the intelligence at work behind the movements. Dancers need to ask themselves, why do that? Why add another move? And sometimes, “Oh, God, take some away!” The aim should be to make something visible not to support “an illusion of necessity.” She says, “Sometimes it feels like it’s important to someone but it’s hard to say why. And sometimes, let’s face it, it’s hard to watch someone so….committed.”

On the same night, Ishmael Houston-Jones talked about performing his work Without Hope. “It’s changed a lot. Sometimes I find it too emotional to tell about my friend who’s dying. Suddenly one night I find myself talking instead about a picture I’d seen about what elephants do, how they go off by themselves to find a place to die…” Having felt the power of his performance, such a significant change was at first inconceivable. And then it wasn’t.

–

Axis: Julie-Anne Long & Virginia Baxter, Rememberings on Dance, April 11

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 14

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lucy Guerin in 25 Songs on 25 Lines of Words and Art Statement for Seven Voices and Dance

Described by Felber as “a music/theatrical installation for seven voices” this work explores the liminal zones at the edges of sculpture, painting, dance, sound art through a playful reinscription of Ad Reinhardt’s 25 Lines Of Words On Art: Statement of 1958 into a late 20th century hybrid aesthetic combining retro fit design invoking both earlier avant gardes and contemporary cutting edge graphics. The audience enters a Futurist mise en scene of huge swinging steel rods with light bulbs at the end of them and 7 steel tubes suspended from the ceiling each broadcasting one of the voices from Elliott Gyger’s composition. But one of the most effective elements is the video projection of Lucy Guerin’s 3 movement pieces which haunt the space silently, interrogating the audience from the floor beneath their feet.

The opening of the event featured a live performance from Guerin, one of Australia’s most sought after dancers, whose choreography also echoed elements of the Reinhardt text (#16 verticality and horizontality, rectilinearity, parallelism, stasis). The space (not designed for live arts) was absolutely packed which meant that for most of the performance parts of the audience were unsighted. This resulted in a strange theatre of frustration where members of the audience shrugged their shoulders, huffed and puffed, rolled their eyes, unconsciously entering the piece as they unexpectedly reacquired their bodies in the absence of a line of sight. Reinhardt would have loved it…#24 the completest control for the purest spontaneity.

Though all the disparate elements of the work arise from a reading of the Reinhardt text, no attempt has been made to force them into a hokey mimetic relationship. They simply accompany each other and gaze at each other disinterestedly, allowing room for an audience to move, at least in an intellectual sense…The piece is accompanied by a beautifully finished book which features interviews with the artists and reproductions of Felber’s images, stills from Guerin’s dances and the musical scores for the 25 songs with a CD. Credit Suisse (among others) sponsored this piece and you can see where the money went! Thankfully it has been put to good use.

–

25 Songs On 25 Lines Of Words On Art Statement For Seven Voices And Dance, artist Joe Felber, composer Elliott Gyger, dancer/choreographer Lucy Guerin, curator Victoria Lynn, AGNSW, March 28 – May 2. The work will tour other galleries throughout 1999 and 2000.

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 40

© Edward Scheer; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Joyce Hinterding and David Haines, Bruny Island

Joyce Hinterding and David Haines are Sydney-based artists who have been exhibiting internationally for over 10 years. With an eclectic background that includes a diploma in gold- and silversmithing and a trade certificate in electronics, Hinterding is best known for her work with installations utilising electricity, electromagnetics and acoustics and for the manufacture of idiosyncratic aerials which render visible innate atmospheric energy. Haines specialises in combining apparently incompatible elements into works exploring landscape and fiction and presenting a “constructed world of the imagination.” His work includes painting, video installations, soundworks, computer-generated pieces and text-based conceptual work.

Last summer, Haines and Hinterding arrived in Tasmania for a 3-month residency at the lighthouse on South Bruny Island, south of Hobart. Bruny is a small unspoiled bushland island. Accessible only by vehicular ferry, it has a limited permanent population but is a popular holiday destination. Like the entire southern coast of Tasmania, Bruny is often described as being “as far south as you can go—the last stop before Antarctica…” Haines and Hinterding share a passion for the landscape and the environment so the South Bruny Lighthouse was a logical location for their residency, which was commissioned by Contemporary Art Services Tasmania.

The lighthouse site was made available by the Tasmanian government’s Parks and Wildlife Division and the Arts Ministry, providing a series of artists’ Wilderness Residencies throughout the state. As local arts administrator Sean Kelly notes, the scheme is very appropriate—if somewhat overdue—and should permit a variety of artists, from different backgrounds and disciplines, to work within and from a wilderness base. It could also extend the discourse on landscape art in the state and counteract its tendency towards the purely representational.

Joyce Hinterding describes the lighthouse as a place “where sky, sea and land meet in a space of watchfulness, beacons and signalling.” She explains that the aim was to “create an environmentally low-impact work that involves the use of fictive and imagistic elements directed by environmental data to create a meta-world, an interior and contemplative space, affected by the surrounding environment.”

In essence the work uses the sensitivities of the local environment to “activate an interior space of the imagination”, the interior of the lighthouse containing a light and sound work generated, created and affected by the passing of all sorts of weather and technologies.

The installation utilises computers, data projectors, a sound system with mixing desk, wind monitoring and radio scanning equipment, a digital video camera and editing system plus assorted microphones, modems, data and antennae. The work monitors and decodes the automatic picture transmissions from passing polar orbiting satellites, translating the data into a sound event and a triggering mechanism for other elements of the installation. Wind-monitoring equipment on the lighthouse determines the speed of footage shown, so that shots are shorter and sharper when the wind is strong and more meditative when the wind is low.

Sound and video footage taken from the local landscape is composited with 3D generated systems where the natural world collides with synthetic imagery. The work grows and evolves over the time of the “exhibition” as the database of real and 3D footage increases. Haines and Hinterding regard the work as a contemporary slant on the tradition of remote landscape works, existing outside the gallery system. In effect, the whole lighthouse becomes a multi-layered high-tech installation artwork, a sort of shrine to the possibilities of new media.

During their residency, the artists became part of the Bruny community, welcoming numerous visitors to the site and interacting with the Hobart arts fraternity. The project coincided with the 2-week Curators’ School in New Media organised in Hobart by CAST and ANAT (Australian Network for Art and Technology). The 50 participants from all around Australia visited the artists at the lighthouse to observe the work in progress, an experience highly regarded by all involved.

At Hobart’s School of Art the pair participated in the weekly public forum (in which influential and interesting contemporary artists, designers, curators and arts administrators, both Australian and international, discuss their work). These sessions are usually enlightening, but Haines’ and Hinterding’s presentation, in which they spoke about the residency in the context of their earlier works, was certainly one of the highlights in the forum program to date. With their self-deprecating humour and enthusiasm, the artists were able to take a difficult, even obscure, science-based, specialised subject, expound it to an arts-and-humanities audience, and make it accessible, intelligible—even entertaining and amusing. Like the installation itself, this was quite an achievement.

All quotations from the artists’ statements.

New Media Residency and Installation by Joyce Hinterding and David Haines, CAST, Bruny Island, Southern Tasmania, March – April 1999

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 38

© Di Klaosen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Rice

Jenny Weight’s Rice is an assortment of cultural odds and ends—dominoes, spearmint chewing gum wrapper, a portrait in a red checked shirt, calligraphy, television coverage, 4 year-olds and Shockwave animations. “The time has come for action” says a United States president and it’s American imperialism full steam ahead with a voice I do know—Jimi Hendrix—and a journey into archives of memory on war. There’s a sense of displacement. A woman screams in the early morning in a hotel room. She won’t stop.

We’re in North Vietnam now, listening to the static, “In Vietnam/we swallow the future whole./But digested/is different/from dead.” The dominoes start to topple and we become “the supertourists. We stand outside, bigger than our own history.” Vietnamese fighters and quick hopping doves. An endlessness of clicking, cameras, keyboards keys, dirt and heaven. Like a game of patience, surprises are turned up and over, yet framed in circles by distance. Images are ambiguous, nothing appears as it seems, but each link lays a brick, solidifying speculation.

“If you are childless/and you visit Vietnam/it is best to lie…” A cybertourist, too, wants the authentic experience. Rice plays games with our need to know, vomits up images of truth and desire, tampered with, and then punishes us for believing. Its jewels, “the beauty of junk”, the collected past makes, and is resistant to, us. We continue searching for the poem factory in a creaky cyclo.

The Unknown

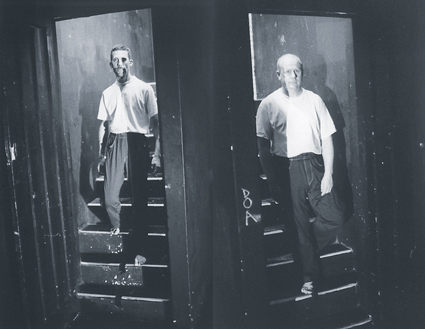

While Rice looks out from Australia, the other competition winner, The Unknown, in typical United States fashion, looks deep within, into the bowels and beyond. We’re all goin’ on a…another road trip folks and we’ll take up where Kerouac and De Lillo left off…to frontier fiction with a special travel itinerary, with 3 academics who can’t change a tyre, on a book tour to flog The Anthology of the Unknown. (Who says that Americans don’t understand irony?). Starting from write-about-what-ya-know (downside: “we are often unaware of the scope and structure of our ignorance”—Thomas Pynchon quoted), The Unknown is a satire on publishing and promotion as well as a tough and funny look at the nature of creating hypertext: “the reader becomes a sort of satellite taking photographs of a huge and varied terrain.”

Largely text based, the site cleverly uses audio of the ‘writers’ speaking at conferences, debates topics as crucial as that criticism can be as much an artform as literature (okay, so they are laughing hash-hysterically at this point). Hilarious shots of 3 suit-and-tongue-tied men dwarfed by huge public sculptures add to the rich subversive mix. They even criticise one of the trAce/alt-x competition judges Mark Amerika (they meet him at Tennis Home, a Rehab centre for Hollywood starlets and hypertext dropouts). The live readings with audience murmurings and applause which play throughout give the work a sense of movement and wit and, although this territory has been traversed before online, what Americans excel at is BIGness and this mammoth chunk of cyberspace defies, and plays with, expectation and The Dream: “I sat up and stared at an American landscape we had not yet named.”

Rice (Jenny Weight) and The Unknown (William Gillespie, Scott Rettberg, Dirk Stratton, Frank Marquardt) were joint winners of the trAce competition. Jenny Weight lives in Adelaide. She received a new media artist residency at Media Resource Centre to develop Rice.

The trAce/alt-x hypertext competition prize is for 100 pounds. 152 entries were received including many from Australia. Submissions had to be web-based with high quality writing; excellent overall conceptual design and hyperlink structure; and ease of use for the average web surfer.

The above winners can be found on the trAce website http://trace.ntu.ac.uk/ hypertext/ [expired] with further information on the competition. Three sites also gained honourable mentions: *water always writes in *plural by Josephine Wilson & Linda Carroli, (Australia), Kokura by Mary-Kim Arnold (USA) and Michael Atavar’s calendar (UK). The competition will re-open at the end of 1999.

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 16

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Philipa Rothfield & Elizabeth Keen, Pensive

photo Hellen Sky

Philipa Rothfield & Elizabeth Keen, Pensive

The primacy of the body as matter for thought has become a tenet of poststructuralism. Likewise the notion that embodiment is a form of knowing. Philipa Rothfield’s ‘thought experiment’ at Dancehouse was to bodily explore these ideas, by allowing a little ‘Pensive’ reflection to take place in performance. She and dancer Elizabeth Keen began with a right turn logic that marked out a progression of squares on the floor—their soft footfalls diminishing lines to perimeters. Keen speaks of Descartes, who else? For isn’t he the man who caused the problems…He asks “what then am I?” Keen watches. Rothfield is an arm/arc/archipelago. She is more beautiful than Descartes in her shimmering shot fabric, fake fur and leopard spots. She is a lioness while ‘he’ observes and speaks—utterance seems to defy movement.

Soon the 2 find moments of overlap. There is a licking, sliding, pawing—they become a conjoined woman. A Siamese twin with 2 heads, 2 hearts, 2 hands, 2 feet—how does she think? This is a problem for psychology—‘both hands are holding the mouse of the computer’—but would philosophy have them torn apart? The dancers are locked and knotted through and around until their heads appear to rest, one against the other. They are like-in-like with a certain coyness about their private discoveries. Their gaze is direct and beyond reach but not far away. I am struck by an intentionality in their looking which suggests a certain kinesphere—a thought realm that can be held in and around the body. It stays quite constant throughout, the way that thoughts venture forth only so far and then return.

Dancing separately, there begins greater variation—thoughts exist in contradistinction, thinking like no other, thought in a hand held up or thought holding itself in a cupping at the back of the head. The body and mind we are told is a ‘fissure’, a word-sound. Possibly a wound, or possibly something to be filled. Their final duet is a reply to this gap in thought—but it is filled with ugly words that end with -ity or -acy or -ility and -ation. They hook toes and elbows, they investigate ‘incorporation.’

The piece was like a hieroglyphic—sketches of women, eagles and crescents drawn in sandstone and therefore, a little flat, following a single narrative line leading us from proposition to proposition with interludes of wonder in between. I am very fond of Descartes’ thought meditations and although we might be troubled by his conclusion “I think therefore I am”, there is a wonderful delirium in his questioning of self, of God and of reality—in his writing he lets himself go to the limits of thinking through his body. Pensive suggests a more measured contribution to thought and it seems that Rothfield’s work was the preliminary sketch of a meditation that is still to ‘hallucinate’ the dialogue between an I and a body. The conclusion with its postmodern emphasis—an incantatory resolution drawing the binaries of bodies and thought together—arrived too soon, historically and artistically, to shift the influence of Descartes from this self-conscious dance work.

Another approach to the problems of the cogito, the defining of the human subject by the thinking I, is evident in desoxy Theatre’s DNA 98.4% (being human). This major work asks the questions ‘what thinking has made the human species regard itself as above all others?’ or more directly ‘what makes the human genetically different from other animals?’ Their answer is not so pretty, in fact what you watch is disturbing, if also funny peculiar, as Teresa Blake and Dan Whitton become ape, reptile, bird and transhuman. This project has been reworked over 4 years and the complexity of the research shows in the extraordinary bodies of the artists, androgynous but even less than sexual, andromorphic. What they do on the horizontal and vertical planes of movement confounds categories—climbing walls as a body of upper or lower legs or looping over themselves in a spiral of links in the chain between DNA and the exoskeleton. At one point they put on genitalia to distinguish man from woman, with their converse heights presenting a further confusion of sexual roles. They enact a courtship dance—the fundamentals of mating are necessary after all to further the species but the distance between our socialistion of those needs and their function is immense. The more disturbing reality is that it could be dispensed with altogether if the scientists of the human genome project advance their supremacist biological thinking. Suspended in cocoons, desoxy await their dying so that the human DNA can be incubated for future generations. I am confronted by the work to consider evolution, its inexorable hold on science and its relationship to humanness.

There is too much to take in, to absorb in ideas and in looking from desoxy’s sometimes didactic presentation of this material; but I am grateful that they are artists whose living is to make art that asks seriously hard questions. It seemed ironic that this production which played to small audiences was pitted against the Melbourne Comedy Festival—will we really laugh ourselves into oblivion.

For more on 98.4%DNA, see Mary-Ann Robinson, “Double helix of tricks and ideas”, page 32

Pensive, Writer/deviser/performer Philipa Rothfield, performer Elizabeth Keen, designer Like Pither, costume design Heidi Wharton, Dancehouse, April 23 -25; 98.4% DNA (being human), desoxy Theatre, David Williamson Theatre, Swinburne Institute of Technology, Melbourne, April 13 – May 1

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 39

© Rachel Fensham; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

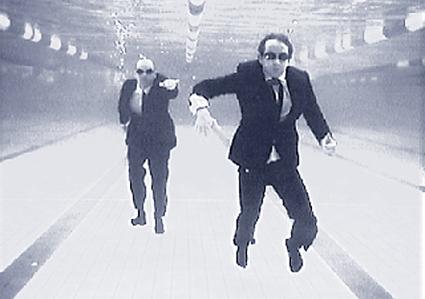

Company in Space, Escape Velociy

photo Jeff Busby

Company in Space, Escape Velociy

Ferocious debate characterised the third international dance and technology conference, IDAT ’99, before it even began. Hosted by Arizona State University in Tempe, this event sought to maintain its status as the foremost international platform for this ever growing field of work—on a tiny budget. So the dance-tech internet mail list blazed for weeks in advance with dramatic vitriol from far-flung artists, angry at the lack of bursaries and fees.

In the event, the international turn-out was impressive, with a strong Australian contingent done proud by Company in Space’s sublime telematic performance in the internet cafe, and the intelligent debate of artists such as Sarah Neville of Heliograph. Whilst there were many Europeans, in particular Brits, who appear to have suddenly woken up to new media in dance, there was naturally a preponderance of Americans and an overdose of academics, so that many of the panels deteriorated into navel gazing. Fortunately the pace of the conference was hot, with 3 events occurring simultaneously at every slot throughout the weekend, so those with an aversion to semiotics were able to busy themselves with workshops and demonstrations.

The potential for creativity offered by pre-existing or artist-invented technologies was clear in the diversity of the performances. The scale of quality was equally well explored. In well-equipped studio and theatre spaces, the presentations ranged from Troika Ranch’s now seminal demonstrations of their patented MidiDancer suit, which alters images and effects in live performance, to the work-in-progress sharings of emerging artists, such as Trajal Harell, dabbling with gadgets in their relation to his mature choreography. There was overwhelming poetry in The Secret Project, a text and movement solo in a Big-Eye environment created by Jools Gilson-Ellis and Richard Povall. The quirky Geishas and Ballerinas of Die Audio Gruppe from Berlin struggled onto a bare stage, to interpret the deafening feedback created by their interaction with Benoit Maubrey’s home-made electro-acoustic suits.

Isabelle Choiniere from Canada offered a terrifying neon-lit Kali figure in her full evening performance, Communion, which scored high for sound and fury but low for the slightest discernable meaning. Local hero, Seth Riskin, took his Star Wars styled sabres to their logical conclusions in Light Dance, an Oskar Schlemmer styled series of tableaux vivants which traced an instructive attention loss curve, where the decline of audience engagement was predicated on the initial impact made by each newly introduced effect. The more we saw, and the more dazzling it at first appeared, the more quickly we grew bored. Jennifer Predock-Linnell had a crack at the good old partnership of dance and film, with strong imagery provided by Rogulja Wolf, and Sean Curran made a small concession to technology by tripping his virtuoso solo in front of some projections. Ellen Bromberg provided the choreography in a collaboration with Douglas Rosenberg and John D Mitchell, and yet her production suffered for its all too well integrated media and fell somehow, slickly slack. Sarah Rubidge and Gretchen Schiller both created touchingly personal environments with responsive performance installation works, and Johannes Birringer and Stephan Silver opened their interactive spaces to marauding dancers in a workshop context.

Many other excellent performances added to the impression of an energetic and abundant art-form, encompassing a dizzying array of practices. There were few shared starting points to be found in any of the events, and this became even more apparent in the debates, which stirred up some exciting disagreements. A panel of artists took on the provocatively titled, “Content and the Seeming Loss of Spirituality in Technologically Mediated Works.” Presentations demonstrated a grounding in the sensual (Thecla Schiphorst’s enquiries into touch and “skin-consciousness” through interactive installations) and the religious (Stelarc’s shamanistic suspensions.) There was talk of the potential for abstraction contained in digitally mediated realms. The informed exchange inspired as many “back-to-basics” anti-technology comments as it did eulogies for hard-wiring and hypertext. Much was made of the fact that new media work in progress is often forced into the guise of finished product, when really it is only the start of a dialogue. The debate polarised; the artist should just dive on in, only this “hands-on” approach will get results; the artist must always approach technology with an idea in mind; technology can only ever facilitate, never create.

At the round table titled “The Theoretical-Critical-Creative Loop”, British artist Sarah Rubidge nailed her struggle to make work and theorise simultaneously by inventing the phrase “work-in-process.” Rubidge is searching for a new way of thinking about the evolving dynamic of productions such as Passing Phases, her installation which offers a route out of authorial control and into the newly imagined realms of genuine audience interactivity. Something innate to the complexity of the technology and its intervention into the experience of the viewer has taken Rubidge’s choreography out of her hands. Still struggling to escape her analytical roots and wary of the ‘inflatory’ language appended to much theorising about this work, Rubidge presented a tentative and thoughtful approach to her parallel roles as artist, academic and writer.

Another British choreographer, Susan Kozel, dissected her approach to the potentially restrictive technology of motion capture. Strapped up with wires, Kozel explores the margins of the technology, testing it to its point of failure. She spoke lucidly about artists working intimately with technology to counteract the idea of depersonalisation. The radical individualism of her appropriation of the motion capture system (to the extent that the bouncing cubes of the animated figure could be “named” according to who was wearing the sensors) was evidence of the vigour of the relationship between the body and technology which she believed to be at the heart of all the work on show in Arizona. There was no shortage of strong opinion at IDAT, and none of it simplistic. Let me leave the last word with a cynical critic from the fiery final panel. Her double-edged sword summarises the conference experience, by provoking exasperation and exhilaration in equal parts, “The more I see of technology, the more I thirst for live performance.”

IDAT 99, International Dance and Technology Conference, Arizona State University, Tempe, Feb 22 – 29

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 35

© Sophie Hansen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Here is a metanarrative-free text which is seriously intertextual, idiosyncratically fragmented and dangerously challenging notions of authorship. It wouldn’t be stretching the point to make claims for its flavours of bricolage, (re)appropriation and even the ludic. While (sadly) lacking in irony, parody or camp, it is possible to detect an ecstasy of excess, an inferno of intergenericity, a nose for nostalgia, a quire of “quotations”, a ream of repetitions, and a penchant for pastiche.

Here is a metanarrative-free text which is seriously intertextual, idiosyncratically fragmented and dangerously challenging notions of authorship. It wouldn’t be stretching the point to make claims for its flavours of bricolage, (re)appropriation and even the ludic. While (sadly) lacking in irony, parody or camp, it is possible to detect an ecstasy of excess, an inferno of intergenericity, a nose for nostalgia, a quire of “quotations”, a ream of repetitions, and a penchant for pastiche.

A Baudrillardian wetdream? A work by Imants Tillers? The poster for The Truman Show? Nothing so obvious—but you might turn to another article if this one began by revealing the text in question as Get The Picture, the Australian Film Commission’s 5th edition of their biannual “essential data on Australian film, television, video and new media” (AFC, Sydney, 1998). But if statistics, pie charts and line graphs are not your accustomed fare, postmodern or otherwise, don’t be put off. Where else could you discover the media facts and figures to dazzle your friends? Did you know, for instance, that Australian women beat their menfolk by 6 percent in terms of bums on cinema seats? That our consumption of popcorn and cola represents a mighty 17 percent of exhibitors’ income? Or that while Sydney television viewers in 1997 preferred True Lies and Speed to Muriel’s Wedding, in Melbourne they sensibly opted for Muriel and the Crown Casino Opening Ceremony in preference to either Schwarzenegger on a bad day or Keanu Reeves and Sandra Bullock on an even worse one. This may all sound like media trivia to you—but to the industry it’s life and death.

To everyone who cares about the future of screen culture, reliable data about production, distribution, exhibition, audiences, overseas sales, ratings, video rentals and sell-throughs and awards is crucial. Without it, wheels will continue to be reinvented, mistakes remade and, perhaps even more potentially disastrous, successes turned into persistent formulaic codes and conventions.

The AFC and the editors of Get The Picture, Rosemary Curtis and Cathy Gray, should be more than congratulated on this excellent book, they deserve to be hugged. This is a model book of its kind. It proved to this normally chart-allergic cultural analyst that the mantra ‘style equals content’, ritualistically chanted to media students and cultural producers, applies to sets of statistics as much as it does to films, television programs, videos, digital media products, or any other text.

The book provides overviews of each chapter, a beautifully simple cross referencing system, enough historical background to make sense of the present, and clearly designed visual material in the form of charts, graphs and columns (plus the occasional production still) to make browsing an attractive proposition. In addition, the introductory sections are written with verve and style—in particular those by Sandy George, Garry Maddox and Jock Given. In short, the data collected in this book is peerlessly presented, can be effortlessly acquired and understood and provides a comprehensive survey of our screen industry and culture.

So much for the formal characteristics of Get The Picture. But what, as Grace Kelly crucially asked of James Stewart after he had (somewhat tediously to someone wanting to be kissed) adumbrated a series of observable, empirical facts in Rear Window, does it all mean? For without this question there wouldn’t have been a movie—not a movie worth watching. This point is raised by AFC Research Manager, co-editor Rosemary Curtis, in her introduction:

Then there is the issue of what the data means—what it is telling us. This question is not unique to Australia—there are few international standards of performance indicators in this area—but it is vitally important. While the breadth and width of the data collection must be maintained, the new task is to develop methodologies for analysing and contextualising it.

This, of course, is where the fun (or pain) begins. It is perfectly possible to draw complacent conclusions from the array of data about the state of the industry a couple of years ago. Total employment in the media industries had increased since 1986 by 53 percent. The size of the industry in number of business terms had expanded by 70 percent since mid-1994. The number of feature films produced in the 90s was almost double what it was in the 1970s. Screens and admissions have both steadily increased over the past years. On the whole, the data apparently provides cause for celebration.

But we can’t ignore what the data doesn’t (or can’t) reveal. Worrying tendencies or patterns are emerging. There may be more women employed in the screen industries than the average for all industries, but there are also more women earning less and more women working only part-time. Who knows if this is from choice? Feature film production may be almost twice what it was in the 1970s, but it’s down—and decreasing—from the 1980s. Is this the result of increased budgets in an unsuccessful attempt to compete with mainstream blockbusters?

It may be precipitant to celebrate the increase in screens and admissions: in 1995 the number of US screens per million population stood at 106 while we had only 64; Americans visited the cinema an average of 5 times a year while we went merely 3.9 times. Clearly growth in Australia has to be carefully nurtured if the stasis the US is experiencing is to be prevented.

What can be deduced from the fact that between 1993/4 to 1996/7 the number of films classified MA rose from 8 percent to 18 percent? Does this mean excessive classification criteria or more violent movies? What is the significance in the levelling off of video rentals and the increase in sell-through purchases? Might this lead to fewer video classics as some fear?

Nor does data alone shed light on Australian screen tastebuds in terms of both production and consumption. There seems little to celebrate in the reduction in the number of Australian movies in the top 50 from 2 in 1996 (Babe at 2, Shine at 20) to one in 1997 (The Castle at 13). Undeniably, the films themselves leave some screen culture analysts with an unpleasant aftertaste and raise questions about the commissioning and funding process which no amount of data will answer.

As Rosemary Curtis states, the bringing together of an extensive array of information and commentary on Australia’s audiovisual industries—film, video, television and new media (as she quaintly calls what is, by now, a medium fast reaching maturity)—is part of the effort to develop methodologies for analysing and contextualising the data. She is clearly aware, by her use of the plural, that there is no single thought-frame for any industry or government body to adopt. It would be disastrous if we failed to espouse a pluralistic approach to either the production and funding processes or the analysis of our screen culture.

Get The Picture: essential data on Australian film, television, video and new media, 5th edition, Australian Film Commission, Sydney 1998.

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 21

© Jane Mills; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net