Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Josephine Wilson and Linda Carroli’s latest collaboration cipher (ensemble.va.com.au/cipher) is a work in progress sharing similar themes with their award winning hyperfiction water *always writes in *plural, and starts from the traditional, “the book is open.” A kaleidoscope of scenes and settings—pages from a book, shelves, a comfortable armchair, a computer screen—place you from the start and demand a response: are you alone? You have new mail, and are suddenly manipulated, part of the detective work, controlled by the text. Older modes of communication—love letters—take on new forms. Electronic casanovas. We search, via M, for love and red blooded passion through “the spaces created by the interplay of writing and the surfaces of the world.”

The masses are skittled, and huddle in tiny groups in isolated bunkers, tuning their VCR’s and pressing their mute button.

Television and its impact on our history and vice versa—see the walls coming down, see communities obliterated—is filtered via satellite and modem. You either wear red or you don’t. It doesn’t suit me but I go for “jealous red lipstick.” Sexy communist cartoons. A landscape of interior decorating—delicate hands folding paper, Tarot cards featuring the fool, beads to peer through—where I become Alice in Wonderland. We are looking for answers and head off to Amerika where “bodies are redundant”, treated like “junk.”

I find a new word, one that fits me well—steganography: the art and science of communicating in a way which hides the existence of the communication. Messages hidden within messages. Penetrating space. M is learning to write. She is hunting for C. She loves and fears the alphabet as it begins to shape her. This is not the story of O (although her sleazy French teacher wishes it was). Chaos or control? The choice is yours.

Xander Mellish’s integration of short stories and cartoons (www.xmel.com) began 6 years ago in New York as a series of posters plastered around the city, with the beginnings of a short story and a phone number inviting readers to find out the ending. After speaking to callers and spying on readers, Xander jumped online. With strong black and white graphics alongside a collection of satirical stories based on New York obsessions and conventions, the site is funny and sharp. It could be even better with a sense of connection between image and text, a reworking so that the graphics become more than just illustrative.

In “The Big Money” Mellish uses her knack for picking out others’ insecurities, and twisting them, to good effect:

Billy Dose was wondering if the baseball cap he was wearing to hide his hair loss was, in fact, making his hair fall out faster. He was also worrying that it made him look dimwitted, like the type of man who might actually care about baseball…“How are the Yankees doing this year?” she asked. “The Yankees?” “Your cap,” she said.

The central character, Veda Bierce, a hungry and homeless woman who gatecrashes the same party, moves on to Hollywood…well actually California…where she becomes an actor with regular court appearances, specialising in “on-the-job accidents, all unprovable soft-tissue injuries.” Other site highlights include “Matchmaking Creeps” where an ex-flight attendant uses software programs to wreak havoc on former lovers, reaching almost American Psycho proportions; and “Joel Faure, The Melancholy Male Model”, which takes self-obsession to new depths, tracing the vacuous thoughts of a solipsistic cartoon hunk, a series of vignettes proving that “beautiful people have terrible love lives”: Joel on the catwalk in Paris dreams of the violinist he can never have; Joel searches for enlightenment and gets centred: The Buddha turned to page 168 of that month’s Vogue, which had me next to a Lamborghini. You exalt in your apartness, he said.

Karen Hudes’ exquisite graphic narrative Dot Cum (www.dot-cum.com – expired) features intersections with a number of digital artists—Susan Hudes, Ethan Cornell, Anu Schwartz, Miguel Heredia, Kartini Tanoto, Kat Kinsman—with an engaging opener: Unlike the human kinds we know, synthetic personalities may take eons to decompose. So we sniff out traces of Dot, who works in Cyberdello, where she records visitors’ profiles. Sleeping in halfway stations, she becomes adrift and isolated, in a floating world where faces disintegrate and worlds collide; a graveyard for avatars. There’s Musk, trapped between the walls, “his link back to cloud-covered terra firma had snapped in silent hands.” The virtual imaginations of writer/artists run riot to produce elegant combinations—Japanese prints, Gothic, sci-fi, corrupt cities, scratched surfaces, black and white ink drawings, organic, sprouting photography, erotic delicate objects—and dreamlike spaces where every click is a treat. Dot thrives and mutates, into a new sphere—the cyberafterlife, “perhaps made of paper.” But there are hints of closer worlds: You have an outside here, don’t you? Of course, dear, where else would everyone smoke.

RealTime issue #35 Feb-March 2000 pg. 23

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

In an industry where newer, faster and more powerful are usually synonymous with quality it is surprising to find a mini-boom in software that is slower, graphically inferior and borderline obsolete. This is because computers and computer software have always been considered functional objects. They did things. Performed tasks. And when a newer version of a program came along which performed the same task faster or more efficiently, the old version was straight into the bin.

Even games were victims of this staged obsolescence. The buying public want the new games. The new games looked and sounded better therefore they were better therefore you may as well throw out that copy of Mario Brothers because here comes Super Mario Brothers. Historically, graphics have always been able to sell a game. Gameplay is more difficult. Consumers have often found it difficult to see past a dated surface to the game inside.

But things are changing. A recent boom in emulation has (in a physical sense) made old software accessible to more people than ever before and (in a theoretical sense) given us yet another example of the slow maturation of entertainment software. Put simply, emulation allows owners of high end PCs to run software designed for foreign formats. That means old Nintendo games, old Atari 2600 games, old Amiga games, and a slew of different arcade boards. And we’re not talking the half-baked arcade conversions ported to PCs in years past, we’re talking perfect arcade/system replicas. Consider it a gaming renaissance.

Software that you thought had died with systems you owned in the 80s can be resurrected on your brand new Pentium or i-Mac. Games that are no longer for sale and no longer available at any price, games that your mother threw out, games that rotted in your closet, games that died in the sun, all of them can be played afresh. And this is what lies at the heart of emulation: preservation. There is also no money involved. Emulators are (for the main) freeware, designed by enthusiasts for enthusiasts. In other words emulators appeal to those who appreciate the subtle art of gameplay regardless of its age. People who understand that newer isn’t always better, faster isn’t always more enjoyable, and that there are few things as enjoyable in life as bouncing a tiny green bubble-blowing dragon around a 16 colour, single screen maze in Taito’s 1986 classic Bubble Bobble.

At ground level people are taking games seriously. This is not an argument foisted on people by academics or cultural observers. In fact, most cultural observers couldn’t care less about games, the ubiquitous and only passably entertaining Tomb Raider series and Douglas Coupland aside. This is a grass roots revival which is showing us that games are no longer the disposable tissues of the entertainment world.

Legally, emulators exist in a grey area. The programs themselves are perfectly legal so long as certain reverse engineering techniques are avoided. This has been true since Atari lost its suit against Colecovision in the early 80s for marketing the ‘Atari 2600 expansion kit’ which allowed users to play Atari 2600 games on their Colecovision. However the situation regarding games is a little hazier. If you own the actual game you are allowed to own the copy of the game on your PC. If you don’t, you can’t. A fact which of course hasn’t stopped anybody or escaped the notice of the copyright holders. But that isn’t the issue here. Morally, most emulators occupy the high ground. They emulate systems which are no longer available for sale, often by companies which went belly up over a decade ago. They allow people to play games they could not buy at any price.

Why is this important? To those who have never had an interest in games, well, probably it isn’t. But to those of us who grew up in front of their trusty Amiga 500, it means a hell of a lot. A chance to relive classic gaming moments and a chance to realise that games are a powerful and different medium.

What were old games? Think of them as genre fiction. They were fun. People enjoyed them and happily spent money on them. Some of them had great depth and intelligence. Most of them didn’t. But they allowed game companies to grow fat enough to put together the millions of dollars that modern games require. Think of them as analogous with the populist origins of other artforms.

For home game systems, it all really started in the 80s. Earlier systems had done well but it was the original Nintendo (NES) which boomed and found a place beneath 90% of American family TVs. Many more systems followed, but it was the PlayStation which was the spiritual follow up to the NES in 1995, again selling in ridiculous numbers but this time bringing a level of sophistication most people hadn’t realised was possible.

What has this created? A culture of game players.

The major emulation sites have all topped 20 million hits and growing. There is a massive and varied audience who not only enjoyed playing games in their youth, but who are waiting for the next step. There will be a time soon when players demand more from their software—the signs are already there—and game companies are forced to begin looking at what they are communicating and how they’re doing it. Whether they use this to make a play for ‘art’ status will make interesting viewing.

But while you’re waiting, join the classic gaming fraternity in a celebration of the old and pixilated by checking out these sites for pure gaming history: start at the source, the Multiple Arcade Machine Emulator (MAME) site at www.mame.net then check out Retrogames at www.retrogames.com or the good folk at the site formerly known as Dave’s Classics at www.vintage gaming.com. They should have links to all the files and instructions you need.

RealTime issue #35 Feb-March 2000 pg. 22

© Alex Hutchinson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

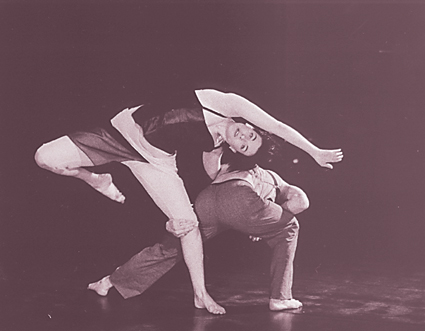

Belinda Cooper, Michael O’Donoghue, In the Heart of the Eye

photo Rachel Roberts

Belinda Cooper, Michael O’Donoghue, In the Heart of the Eye

Dance Lumiere 99 was a very different affair to the Dance Lumiere I curated in 98. Moved to a cinema venue—Cinemedia—and spread over 3 days with 5 themed sessions, curator Tracie Mitchell and her team created a stylish dance screen event as part of the Dancehouse Bodyworks season. With a weekend-long film program as part of Perth’s Dancers Are Space Eaters in 1999, an Adelaide dance film screening in November last year, and One Extra Company’s dance screen event scheduled for May this year, substantial attention is turning towards this interdisciplinary form.

Mitchell’s opening night double bill of Revolver, a short British film featuring a very young Liam Neeson, and Milos Forman’s 1979 musical Hair featuring the choreography of Twyla Tharp, was a bold move, but an interesting one that illustrated filmmaker Lawrence Johnstone’s keynote address. Johnstone gave a neat history of dance and film stressing the significance of the musical which too often gets shrugged off like an embarrassing relative. Placing Revolver, a windswept, magical, ‘rondo’ style tale of car problems, a wandering bride and lust beside a highway, against a 70s musical about the 60s that’s as densely worked as a paisley shirt, demonstrated Lawrence’s comments on the diversity of the form. Hair was hysterical—it was great to see it for the first time on film and it warmed up a crowd that appeared to return for other programmes throughout the weekend.

Mitchell chose some very safe, beautiful international work which was a smart move for the festival’s big leap from the $5-a-seat-in-the-studio model, screening works by Laura Taler, Pascal Magnin, Philippe Decouflé and de Keersmaeker; all award-winning dance filmmakers. All have created distinct oeuvres within the form; Taler’s cheeky sentimentalism, Magnin’s cinematic romances, Decouflé’s homages to early cinema, Rosas’ epic masterpieces (De Keersmaeker’s film shown here, Rosa, was directed by Peter Greenaway).

The Australian programme was more of a mixture of low budget, experimental work, well-crafted explorations which had some funding, and glossy packages that had a lot of experience and support behind them. It included work by Christos Linou, Cordelia Beresford, Michelle Heaven, Clair Dyson, Justine Spicer, Morag Brownlie (NZ) and Mitchell herself. Linou’s Fiddle Di Die which I first saw as part of his stage work of the same name is a staccato Super 8 film, the highlight being a series of jumps filmed to create a jerky levitation. Heaven’s collaboration with Jessica Wallace is an interesting first exploration of the film medium for this exquisite performer and the care taken with the resources at hand result in a curious and delicate film. Beresford’s Restoration with choreography and performance by Narelle Benjamin is an amazing graduation short and a good investigation of that awkward place where narrative moves into dance. It’s the type of dance-film performance that has given an international leg-up for companies such as DV8 and La La La Human Steps.

A real thrill was seeing Margie Medlin and Sandra Parker’s collaboration for Danceworks, In the Heart of the Eye. Seen in the same weekend as Dance Lumiere, this work seemed like an exciting jump sideways with its beautifully incorporated film and live work—a rare and remarkable success story. The elegance of the choreography—all fine lines, sharp angles and a lot of beauty—never became cold which I attribute to the ‘dance-cam’ work that placed the audience in the dancer’s head. As the film image on the back wall of screens traces a passage through a classic interior—all wood panelling and stained glass—a dancer in front on the stage marks out the movements that have created the moving image. As she turns abruptly a quick pan occurs. As she swings to and fro in position, in a movement echo, the camera oscillates from side to side. In the Heart of the Eye takes us into a bizarre space between our observations of the dance on stage and the visual experience of the dancer on screen—a heart with no sole (so to speak). Like a strange voyeuristic kinaesthetics, the space or gap at the heart of the relation gives the work a haunted aspect that I found oddly disarming, allowing me to be taken in.

Some black and white footage of the dancers is repeated on the screens like a round (there is usually more than one projection happening at once), the movements falling after each other like ghost-dancers. Other shots were achingly gorgeous, like the falling snow which seemed to freeze/burn into the cinematic image.

Dance Lumiere, curator Tracie Mitchell, Cinemedia at Treasury Theatre, Melbourne, November 18 – 20; In the Heart of the Eye, choreography Sandra Parker, filmmaker/lighting Margie Medlin; Athenaeum II, Melbourne, November 19 – 28, 1999

RealTime issue #35 Feb-March 2000 pg. 33

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Rosalind Crisp has spoken at length about studio-based practice; a collective of artists based around a studio, aligned with the particular type of dance practice which that studio represents. With this Stella b. series, along with the studio showings I have seen over the past 3 years at her Omeo Studios in Newtown, Crisp has achieved exactly this—a distinctive, productive centre of activity that comprises an important part of the rather dislocated dance activity in Sydney.

I saw Stella b. in the second and last weeks of the month-long development. The piece shown, which culminated in a reworking for Artspace in January (The View from Here), consists of a series of repetitions performed solo by dancer Gabrielle Adamik at the front corner of the performance space with duos, trios and quartets by Crisp and the other dancers (Nalina Wait, Lizzie Thomson and Katy Macdonald) unfolding on a plane behind her. The set of column supports running down the performance space of the studio, cutting the space by two thirds, becomes a margin for play with entrances and exits marked by the passage through this architectural feature.

Adamik’s repetitions perform a function similar to James McAllister’s performance in this same space in Six Variations on a Lie; a kind of bass note marking the progression of the work. The gentle, moderate and measured movements characterised by a swinging rhythm and a delicacy of touch, slowly revolve so that each movement is seen from several angles…like a turn-of-the-century study of human motion, but the ‘model’ here occupies a place between going through the motion and being immersed in it with ease.

Behind this, the groupings progress slowly along the floor, burst into the space with bold walks and swinging turns or hesitate with minute foot manipulations at the threshold of the space. Set against the steadiness of Adamik, the variations in energy and intention on this other plane are very satisfying, breaking the moderation just when it is required.

The intensity, detail, stillness and assuredness are all still here from Crisp’s solo work, as are the trademark elastic-ricocheting joints which a friend put her finger on. But with this group work, the edgy immediacy has been replaced with something much more ordered. The unpredictability is still there—perfectly-timed bolts with 4 dancers changing instantaneously from stop to go, or one dancer following a large, reaching gesture with a toe flick—and this is a real achievement. But the group work has obviously necessitated a huge shift—aesthetically and tonally—and it’s a very different experience to the solo Crisp we’ve come to know. The young dancers Crisp is working with have brought a lightness, clarity and ease to the work. It’s a new aesthetic chord in the work that signals a change for Crisp.

Importantly, Ion Pearce’s live sound work seemed to progress in tandem with the performance, being very different on the 2 occasions I attended the showings. The spaces in the score and diversity of sounds—electronic bleeps, percussive elements, music recordings—had an unpredictable quality that perfectly matched the performance.

Rosalind Crisp has been awarded a two-year Fellowship by the Dance Fund of the Australia Council and is one of the choreographer-dancers selected for the New Moves (New Territories) dance workshop at the Telstra Adelaide Festival 2000.

–

RealTime issue #35 Feb-March 2000 pg. 32

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Immersing myself in Philip Brophy’s Sound Punch releases before I went out to Chunky Move’s Live Acts#4 has done something to my brain. I miss the first act…s’okay, I’ve seen it before.Two women rise, feet skywards, from Kate Denborough’s decapitating boxes, restlessly fidgeting with clothing—an inverted, Dali-esque can-can.

In the heady atmosphere of the club, things are getting fuzzy. Video projection warns of impending lift-off before Frances d’Ath’s Pirn morphs on stage. The characteristic Melbourne/Chunky Move fleshy machines are here. D’Ath gives this a computerised clicking—head turns pre-empt torsos and shoulders (“head boppin’, ass droppin’”—Ice Cube). Memories of Live Acts #1-3 leak through. Arms between partner’s legs, leading to interlocking twists, recall Shelley Lasica’s Restricted Situation from LA #1. Twister for intellectuals. All the works have this quality. On this small stage, multiple bodies occupy mutual space. Voiteck’s sharp, gritty techno fuzz clears the air for the performers, placing them in a clean yet distorted machine.

Elvis (Shirley Billings) is in the house, but not looking too good. Viva Las Vegas is low on “viva”, despite ‘Hunka-hunka’ being flanked by the Chunky Move fly-girls. Dead-pan cabaret. I miss Martine Corompt’s anime pet installation and John Meade’s smoking, muppet volcano from earlier LAs. Tonight dark oils hide in the shadows. So much for art. Back to the band!

The design of Byron Perry’s operating theatre drama—Hayflick Limit—recalls Reanimator, but the movement and sound (Aphex Twin’s Nannou) has an almost Renaissance, clockwork feel. The realtime projection of alternative views has cleaned up since Pirn (does this make the earlier, pleasingly viral static ‘not part of the show’?). Two women manipulate a man to the whoops of the crowd. A smirk hides under Fiona Cameron’s lips all night.

Cross-fertilisation between Lucy Guerin and Chunky Move has highlighted the anatomising quality of both, while bringing Guerin towards Gideon Obarzanek’s panto-drama. With Gift, Guerin takes this elsewhere: poppy abstraction, accessible dreams of dancers licked to death like lollipops, or playing with others’ limbs like Christmas treats. Brophy’s masterer—Franc Tetaz—opens up the gorgeous, flowing comedy of the piece with some swinging, French funk (“head boppin’, ass droppin’”).

Then there’s Obarzanek’s Disco.Very and its mish-mash of disco phrases. Where Ransom’s score pounds one 70s classic into another, even using Hendrix riffs to segue between sources, Obarzanek’s choreography is a more subtle melding. I close my stoner eyes and let the turntables dance. Then the dancers double-take and misfire. We see choreographic effort. Even so, Ransom leaves them for dead.

After the packed concentration of the first half, the room becomes a vortical lacuna of movement and sound. Perry’s surgical bed becomes a console table with steady boppin’ DJs behind it. I recall earlier LAs where Obarzanek and Phillip Adams danced spastically to crunchy noise (why is so much techno un-funky?). Professional dancers look weird on the dance floor. Production folk are the real party animals—techie Ruth Bauer is there, bouncing in clogs. Is she performing? Am I?

–

Live Acts #4 Chunky Move, Revolver Night Club, Melbourne, December 16 – 17

RealTime issue #35 Feb-March 2000 pg. 32

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Is there a psycho-kinetic space between the blow and the caress, or is the touch of flesh on flesh always a sadomasochistic enactment of power which both stimulates and contains desire and unpleasure? Melbourne has become the dance performance site for the painful sublime, populated by anatomic, deconstructed bodies from Lucy Guerin, Phillip Adams, Brett Daffy and Gideon Obarzanek. Bodyworks presented a suitably eclectic selection, but the most compelling was that which aroused such Artaudian and Foucauldian ideals.

Russell Dumas is stylistically and geographically removed from these approaches. His work is characterised by a gentle yet controlled ascension of everyday movement into the rigours of formal dance. It represents an aestheticisation of the commonplace, not a Dadaesque challenge to such terms. Nevertheless the depth of his execution and that of Collin Sneesby in Post Larret 99 paradoxically gives them an unmannered ease which problematises their status as ‘performers.’ The embrace however reveals the underlying violence of Dumas’ choreography. Dumas guides and positions his companion, shaping and modifying the latter’s gestures. Despite Dumas’ sensual, soft touch, there is an inherent cruelty in this friendly meeting of flesh. Dumas moves his subject, curtailing Sneesby’s freedom. The aesthetics of ballet is reinscribed through the embrace.

Brett Daffy’s lonely body is not subjected to the literal imposition of another’s power. This is a body that embraces itself in a violent concatenation of disparate body-parts. It is “meat”, smashed against itself under the gaze of the audience. In Human meat processing works, the spectators act as wall-flowers at a nightclub, probing the body visually in a search for sexual arousal. It is not only the observer who enacts this harsh embrace of flesh by the eye though. Like the denizens of the nightclub, Daffy has internalised this gaze; he scrutinises himself. Violent self-regulation is physicalised in a painful, contorted touching of the self which rips apart and meshes together the fragments which meet. Even alone, the sensual violence of the (self-) embrace remains.

Gekidan Kaitaisha’s Into the Century of Degeneration begins with an unmotivated woman, wandering into 3 men who at her touch lift her by the waist, shake her, and drop her. They seize her as though life depended on it. She struggles to escape while one holds her back—protecting her from herself? Each embrace mingles affection, self-hatred, and loathing of the other. One in a dog collar with eyes heavy with unspeakable sadness manipulates his subject as though trying to save her, hoping to agitate her out of her benumbed reverie. A bully-boy with eyes that bore through walls thrashes her about as though wreaking his havoc on the world. The third reacts instinctively, his sensations dulled but his reactions angry. For all 3, the embrace inflicts pain with a loving cruelty, using an aggressive physicality for salvation and damnation, containment and liberation. The uneven pacing of the embrace, its slow, subtle arousal and whip-lashes of fearsome energy, reveals the anger and love that underlies the meeting of flesh. The body and my jaded eyes emerge scarred yet reinvigorated.

–

Bodyworks 99: Post Larret 99, director/performer Russell Dumas, performer Collin Sneesby & various guests; Ward: Human meat processing works, choreographer/performer Brett Daffy; Into the Century of Degeneration, by Gekidan Kaitaisha, director Shinjin Shimizu, Dancehouse, Melbourne, Nov 24 – Dec 7 1999

RealTime issue #35 Feb-March 2000 pg. 32

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lisa O’Neill

Lisa O’Neill leaves her backyard in Brisbane for “the UK’s hottest international contemporary dance festival.” New Moves (New Territories) 2000 in Glasgow is hosting a radical exchange of work with some of Australia’s most exciting contemporary choreographers—Sue Healey and Phillip Adams, Lucy Guerin, Trevor Patrick, Dean Walsh and Lisa herself.

“When I saw these people I was performing with I did a bit of homework and found out that they’re all in the limelight, but they’ll be there with their work and I’ll be there with my slippers, stomping to Nirvana, and I just laughed.”

Nikki Milican, the Festival’s Artistic Director, travelled to Brisbane to see local work and responded to O’Neill’s uniqueness with a request for a 20 minute work to go into the New Moves Australia component of the festival. This is the first time her work has been seen outside Brisbane despite the choreographer having a solid repertoire of 16 works.

“I love what I do so much I’ve never taken the time to promote myself or push my work into anyone’s face. I would not work anywhere else but up here. I can isolate myself and there are no trends to follow.”

O’Neill’s earlier reference to slippers and stomping indicates her close connection to the Suzuki actor-training method which has heavily influenced her development as a contemporary dance choreographer. She has trained 3 days a week for the last 6 years under Jacqui Carroll’s guidance with Frank Productions Austral-Asian Performance Ensemble. O’Neill first came into contact with Carroll in her teens at the Queensland Dance School of Excellence and then at Queensland University of Technology as a student.

“I believe in having a teacher—you always need someone with their eyes on you constantly and Jacqui has…She’s incredibly articulate and she really knows my body—she’s been teaching me since I was 14 years old. That’s a really long relationship. She’s watching me always, suggesting things all the time so I feel safe knowing that someone’s working on me.”

O’Neill is developing a work titled Sweet Yeti for Glasgow which draws on 3 separate solos made for 3 different venues over the last 3 years! “I’ve called the piece Sweet Yeti ‘cause I’ve been working with this Yeti character for a couple of years. I’ve chosen movement material from Yeti in e minor which I did in 1996 at The Cherry Herring, a solo piece from Marble which I did as part of the Brisbane Festival in 1997 and another short solo which I did for The Cherry Herring’s Cityscapes in 1999. All of those works centred around a particular character—myself, my stage persona. Also all of those pieces were actually done in completely different environments and were quite site-specific; Yeti in e minor was created in a cage, Marble was done up against a wall and the Cityscapes piece was in an outdoor environment against a wall of glass. I’ve got these 3 solos done against a wall but they’re very different emotionally and in content because of the environment I was in at the time. So I’ll be developing all those solos up against the one wall for the theatre in Glasgow.”

There is an overt fascination with walls here which O’Neill readily acknowledges. She uses walls in her work as points of departure, support structures, forces of captivity to define spatial qualities, old friends or simply for their visual and architectural stature. It may have something to do with another obsession—her desire for structure both in her work and her working environment.

“I’ve always had a full-on thing about structure. I’ve always structured things. The movement vocab may have been different but I always had a set structure for it to take place in…The Crabroom and The Cherry Herring were a godsend for me. A place to create in. The Crabroom (The Cherry’s predecessor) was where I first started Yeti and I was terrified—I’d never done a solo before but from there I did 3 more and 2 for The Cherry Herring who have always been supportive. I enjoy being in Frank because there is the structure—training every week. I don’t know what I’d do without it. I haven’t done a dance class in 5 years. I’m just training in another way now. Because I have that structure I feel confident independently.”

O’Neill has a busy year ahead. Alongside Glasgow, she has a choreographic commission for L’Attitude 27.5, Brisbane’s new Powerhouse program for independent artists, a collaboration on a laser show, MYRRHA, with Diane Cilento as director, the remounting of Transit Lounge with Keith Armstrong (a multimedia adaptive technology animation set-up), a programme of new work by 3 Frank women, and Frank Production’s own Hamlet in Japan at the Shizuoka International Arts Festival.

“Even though I started out wanting to be a famous Australian dancer in a big company, that never happened and that’s okay. I thought to myself I would do anything to be a really good performer—I would go through anything…do that stomp every day for 10 years so I can stand there on stage and look fucking amazing. That’s what the stomp is for—the stomp is just to find stillness.”

When asked about future directions for her choreographic work, O’Neill replied “I think my work is becoming more simplified. Every piece seems to have less vocab in it. It’s getting more streamlined. But besides choreographing and creating works I’m trying to improve myself as a performer which I do through the Suzuki training. That’s my main objective—to be able to stand in front of an audience one day and not do anything and have it work.”

New Moves (new territories) 2000 will be held in Glasgow, Scotland, March13 – 25 2000. The International Choreographic Laboratory will be held in Adelaide as part of the Telstra Adelaide Festival, February 28 – March 11 2000, and in Glasgow.

RealTime issue #35 Feb-March 2000 pg. 31

© Shaaron Boughen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Tess de Quincey in collaboration with Pamela Lofts

photo Juno Gemes

Tess de Quincey in collaboration with Pamela Lofts

The idea of representation (whether classically defined or ironised in a postmodern sense) is not what the Triple Alice project is about. Certainly, it is an event which is taking place ‘at the centre’—literally so, outside Alice Springs—and which thematically, too, is centred within a set of convergences and overlaps between disciplines, artforms, individuals and languages. In October 1999, it brought together Tess de Quincey’s Body Weather workshop, a group of writers and critics, a large number of painters from Alice Springs, botanists, environmentalists and Indigenous artists together with a program of visiting speakers, politicians, musicians, all of whom were connected with and committed to the day-to-day affairs of the Northern Territory. But even with such a multiform set of activities, criss-crossing over 3 weeks—all roughly related on a theme to do with local place and local environment—there was no intention to set up a representative ‘space’ in which the immediacy of locale could, or should, be embodied. If the experimental practice of the event was definitely locative, Triple Alice’s understanding of locus was not, first off, about the representability of place, nor about its cultural appropriation and exclusiveness.

It’s important to make that distinction. So much work that ‘goes to’ and ‘comes from’ the centre is about representation—about land, about race, about what constitutes a voice or a presence within evolving notions of country. Of course, the first, and highly tentative, attempt to mount Triple Alice links with these ideas. Yet if you were asked to provide some key terms for the event, then a suggestion would be that a series like edge, desert, reticulation and information provides better means for describing the intentions and the outcome of Triple Alice than any discussion of centre and margin could do. In this regard, there was no specific agenda for what could or might have occurred at Hamilton Downs. The aim was to create an information site for participants—sure, a space for interaction. But it was also a means for acquiring knowledge about ground and land-form and the body’s integration with them in the context of a post-industrial analysis of the nature of extremely arid country and the integration of technology with that country.

The terms just mentioned were, in other words, not just arbitrarily poetic. The Triple Alice experiment grows from sustained discussions among a variety of artists and writers, with performer/choreographer Tess de Quincey and her work with Body Weather playing a leading role. The aim, expressed in those discussions, was to imagine an experimental event which would act as a ‘think tank’, a database and a rich and ongoing informatic process. What is an aesthetics, or more accurately a poetics, which responds to locale in Australia? What’s a useful and productive notion of exchange and collaboration in the context of information technologies? What is ‘thinking’ and ‘practice’ at a moment when thought is (to borrow Gregory Ulmer’s terms) conductive and associative and when the “writing of space” is the primary and yet necessarily inconclusive medium for expression? Ulmer’s claim that contemporary legibility is a legibility “beyond representation”—in short, a category of the ontologically unspoken—was a powerful provocation in this first stage.

A Body Weather workshop—a workshop in which the intentionality of body position and movement are read in relation to land form, to earth, to stones, to heat, to wind—was the locus for many of the 50 or so participants. Each workshop was a mini-history of the senses, checked out in meditative and poised relationships not literally related to a dry creekbed or the caterpillar dreaming of the Chewing Ranges visible in the site’s background, but where each participant was conscious of his or her position, autobiographical, intimate, externalised and inward.

The events were photographed and documented as part of a research project conducted through Ian Maxwell at Sydney University’s Centre for Performance Studies. Other writers, artists and photographers intervened in and interacted with the event—photographer Juno Gemes, for example, writer and installation artist Kim Mahood, Alice Springs based artist Pamela Lofts. But there were many other visiting artists who observed or contributed, or simply made new work which criss-crossed with the site and the environment. Some like Ann Mosey or Rod Moss presented and talked about their work. Dorothy Napangardi and Polly Napangardi Watson painted with various members of the group.

Participants were also asked to post statements, texts and journal entries on the Triple Alice website. At the same time, this website was receiving information from writers and artists not at Hamilton Downs but who knew of Triple Alice. It was a first attempt at tracing an interactive history of the senses. There was no ‘theme’ but there was a version, enormously dispersed and many-sided, of a living ‘topo-analysis’ occurring.

As a third element, a small group came together in short seminars focused on current discourses of Australian place. Again there was a wish to keep the edges open in these discussions so that we could include discussion about performance theory, Bachelard’s poetics, the work of intellectual historian Edward Casey, Gregory Ulmer’s work in heuretics and the theorisation of desert, space and sense in J-L Nancy.

The dynamics—and installation of the necessary resource base—for such an event were obviously complex. The location itself, a drive 110 kilometres north-west of Alice, made sure of that. No-one knew if the open-ended terms—edge, desert, reticulation and information—would act as sufficient markers for the trajectory. Would we simply lose our way in the desert, in that place where, according to Jean-Luc Nancy (The Sense of the World, Uni Minnesota Press, 1997) there is “the end of sources, the beginning of the dry excess of sense?” In fact, Triple Alice was immensely information rich and ‘sense’ rich. It seems already to have become productive ground for a series of collaborative and individual projects which are occurring through this year. Triple Alice 2000 will refine the interactive model of ‘sites’ within a site: performance, visual art, writing and the internet. And the collaborative excitement of working with local artists from the centre will continue.

–

Triple Alice, Hamilton Downs, September 20 – October 10 1999.

RealTime issue #35 Feb-March 2000 pg. 8

© Martin Harrison; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

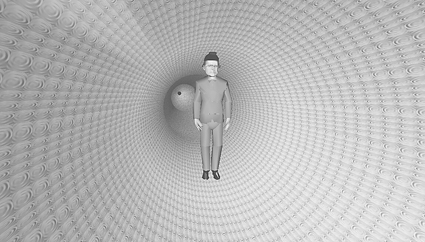

The Men Who Knew Too Much, Virtual Humanoids

dLux media arts’ annual futureScreen event sets out to explore new media hotspots formed at the intersections of art practice, cultural theory and new technologies. 1998’s inaugural event, Immersive Conditions, considered virtual space; last year, AvAtArs | phantom agents took on virtual identity through the figure of the avatar, the placeholder for the self in online virtual environments.

Jeffrey Cook opened proceedings with a paper offering a useful prehistory for the notion of the avatar—a corrective, as Cook noted, to the tendency for new media discourse to naively overestimate its own “newness.” In fact “avatar” is an ancient Sanskrit word—literally meaning “descent”—which referred to the embodiment or manifestation of a god on the earthly plane. As Cook explained, this original usage also suggests a kind of divine multiplicity, a single perfect identity manifest in multiple earthly aspects. However the term’s contemporary meaning, Cook suggested, is also shaped by the more troubled figure of the Golem—in Jewish mythology, an artificial being with a crude clay body brought to life by a heretical cleric. The Golem is thoroughly imperfect, a kludgy construction, a product of fallible technology and human hubris, but it’s magically autonomous—clay with a spark of the divine.

If the avatar is, as Cook suggested, a mixture of god and Golem, at AvAtArs the Golems had the numbers, at least initially. The technology was as fallible as ever, and the online virtual worlds and their avatar inhabitants were weighed down by the kludgy clay of crude 3D geometry and slow net connections. Merryn Neilson and Dave Rasmussen, virtual world designers, were to play host to the remote presence of Bruce Damer, cyberculture’s most prominent avatar evangelist. Neither Damer nor his avatar could be found: we waited, and waited, passing the time zooming through some airy virtual architecture and watching the assembled avatars run through their preset repertoire of kung-fu and ballet moves. Finally Damer appeared in the form of a giant, beaming sphinx-head which spoke in that tinny, choppy stutter of real-time internet audio. “Hello”, it said, “can you hear me?” We switched virtual environments in order to see a webcam image of Damer waving hello once again. These tortuous negotiations with the medium left no time, or energy, for actual “content”—and gave a decidedly underwhelming impression of life as an avatar.

Next Fletcher Andersen, another builder of virtual worlds, introduced his Pollen environment and his avatar persona, Facter Pollen, before giving a clear-headed comparative outline of online environments such as ActiveWorlds and EverQuest. Andersen reported the startling statistic that EverQuest, essentially a giant networked role-playing game, has some 150,000 subscribers who pay $US10 per month in order to keep playing. Welcome to the new economy of online identity. While open about the limitations of these systems and the restrictions which they place on their avatars, Andersen expressed a hope that with technological advances we might soon be able to experience “a true existence within virtual worlds.” Miriam English, another Australian world-builder, anticipated a similar technological progression, culminating in the eventual dominance of virtual worlds over film as a fictional medium.

These presentations represent a “head-on” approach to avatars and virtual worlds; following a conventional VR paradigm, they pursue an ideal of immediacy and immersion which involves pushing against stubborn technological and representational obstacles. Happily, other presenters took on avatars in more tangential and strategic ways. Keynote speaker Adriene Jenik led a performance of a brief excerpt from her Santaman’s Harvest, a chatroom morality play on the evils of genetically-modified food. While it too was fully-laden with technological and representational kludge, some striking and funny theatrical moments filtered through the graphic chat-space which it inhabited. An international ensemble of avatar-actors joined Jenik’s own avatar, the “Prof”, in a loose, haphazard narrative which staked out a performance-space in a cyberspatial public plaza; the finest moments came as an innocent member of the online public stumbled in, blithely looking for someone in her home town to chat to. In the process of striving to maintain a sense of drama, or convey topical content in a normally vacuous virtual space, Jenik’s work develops a keen sense of the social and institutional dynamics which shape those spaces and their avatars.

Others offered a more personal perspective on virtual identity. Bondage mistress and sex industry activist Mistress Eve Black (herself presenting through an “avatar” stand-in) made a clear argument for the value of sexual role-play and identity-shifting. Role-play is ubiquitous, she reminded us—to a greater or lesser extent, we take on socially-prescribed identities in everyday life. Black warned that the current wave of censorship, which has attacked the non-prescribed roles of B&D, involves a narrowing of options for identity-formation and sexual expression. Moving back online, local artist Graham Crawford gave a candid guided tour of his own avatar-selves, “fractal personalities” woven into a hypernetwork of lavish animation. Interestingly the web, which can be both private and public, contained and open, seems to offer an ideal medium for these split selves: each subdirectory can house another past life or lover, neatly enclosed but easily navigated and unpacked. As well these selves are mobile and replicable: a portion of Crawford’s site had recently been mirrored on an overseas server, moving beyond the control of its original “host” to become an autonomous part-self.

Dr Jyanni Steffensen presented another case study in labyrinthine identity, discussing Suzanne Treister’s CD-ROM No Other Symptoms: Time Travelling with Rosalind Brodsky (see Joni Taylor’s review, page 22). Here Brodsky, both “virtual subject” and alter ego for Treister, is the central figure in a dense fantasy world which mingles personal and public histories and fictions, rewriting Freud, Lacan and Kristeva. As in Crawford’s work, complex virtual identities are constructed, explored and exploited through interactive forms—the conventional VR “avatar” is nowhere to be seen. That figure has its uses, though, as Simon Hill and Adam Nash showed. The wooden, “salaryman” personas of their performance art troupe The Men Who Knew Too Much are ideally suited to translation into VR—and their work Virtual Humanoids promises to give virtuality the absurdist send-up it so badly needs.

Finally Stelarc, virtually present via prerecorded video, presented the concept for Movatar, an “inverse avatar” that extends his work with corporeal remote-control. As planned, Movatar describes a tight engagement between avatar and physical body: the performer (“the human”) wears a motion-control prosthesis, a pneumatically-actuated exoframe which moves its host’s limbs like a puppet. This prosthesis is controlled by an autonomous virtual entity, the “digital Movatar.” In an elegant circuit, the digital Movatar is fed sound from the motion of its pneumatic “muscles”; it is “startled”, and changes its behaviour in response. The human body is caught in a feedback loop between the disembodied autonomous entity and its physical machinery, possessed by an unstable avatar.

Movatar raises the close coupling of avatar and host, and of reality and virtuality, in a quite confronting way. It recalled an image that Jeffrey Cook had earlier borrowed from Deleuze and Guattari, of the wasp and the orchid co-forming each other, co-evolving in a double spiral of imitation. Our avatars, Cook proposed, might relate to us in the same way: not as simple projections or representations, but as artificial entities which inflect their creators, “both shaped and shaping.” Cook’s notion was borne out by the more interesting work presented at this forum: rather than an idealised virtual presence, this avatar is used knowingly and experimentally in a game of virtual dress-ups with a serious agenda: the transformation of the self.

dLux media arts, futureScreen 99: AvAtArs | phantom agents, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, November 6 – 7, 1999.

RealTime issue #35 Feb-March 2000 pg. 21

© Mitchell Whitelaw; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

[CHAOS]

Since April last year a steady stream of emails with subject headings like ‘censorship’ and ‘refused classification’ have been coming in. On the art and culture list, Recode, there’s debate, resistance and running commentary among its subscriber base of artists, activists and academics about the Broadcasting Services Amendment (Online Services) Bill 1999 which was passed in May and effective from January 1 2000. As it passed through parliament, Minister for Communications, Information Technology and Arts, Senator Richard Alston’s 1998 speech (Hansard, May 28) echoed loud and clear: “I do not think that anyone in this country wants to see an electronic Sodom and Gomorrah. It is unedifying and debasing and we will take action to…ensure that it does not occur” (www.dcita.gov.au – expired).

Among the responses to the legislation is a protest by Sydney-based ISP, Autonomous Organisation (autonomous.org-expired) which hosts a number of artist sites and artworks. Autonomous Organisation has ‘Refused Classification’ and in a statement published on Recode said, “most of the material published here by artists is relatively innocuous, however, we refuse to deny that existing material and future work…will ever be amongst material which could generally be considered R or X or even RC rated on television.”

As in the arts community, there is speculation in other communities. Opponents include the CSIRO, Electronic Frontier Australia, Civil Liberties Groups and Lawyers, Australian Council for Lesbian and Gay Rights and the Eros Foundation, variously labelling the exercise as unwieldy, contradictory, moralistic, unworkable and an infringement of rights. Author of the ACLGR submission to the Select Senate Committee, Paul Canning (www.rainbow.net.au/~canning – expired) anticipates that the legislation will devastate the Australian lesbian and gay online community with filtering and classification provisions inhibiting access to gay and lesbian sites.

[FREEDOM]

In Electronic Frontier Australia’s Senate submission on the Broadcasting Services Amendment (Online Services) Bill 1999, John Howard is quoted as saying that as an effect of his government, Australians feel more comfortable speaking their opinions and sentiments freely. Howard is referring to the tongue-biting scourge of ‘political correctness’ described in McKenzie Wark’s Virtual Republic (Allen and Unwin, 1997) as possibly “more fantasy than fact.” Using this power of exaggerated myth, quixotic conservatives asserted that the community was held to ideological ransom, censored by some imagined authority in the guise of multiculturalism, feminism and ATSIC. Sure, it’s a whole other story, but as EFA points out, such a statement indicates that ‘freedom of expression’ must be a value of the government. Nevertheless, as the bill was introduced into Parliament, it was described as ‘Draconian’ and more rigid than its Singaporean or Malaysian counterparts.

Chair of the Australia Council’s New Media Arts Fund, John Rimmer also sits on the Board of the Australian Broadcasting Authority. He explained that during its passage through Parliament, the bill was vigorously debated: “You shouldn’t assume that the legislation is as ‘Draconian’ as it appeared when first introduced, as a number of amendments have been made.” Accordingly, the provisions of the Act will be clarified by the Internet Industry Association Code of Practice and as the first complaints are processed.

[CODE]

On December 16, the ABA registered 3 codes of practice outlining the obligations of ISPs and ICHs in relation to internet content. Developed by the Internet Industry Association (www.iia.net.au) for implementation with the Act from January 1, the codes are integral to the co-regulatory scheme established through the legislation. They will operate in conjunction with the ABA’s complaints investigation procedures.

The codes outline the rights and responsibilities of clients, ISPs and ICHs including: customer advice and content management; the requirement for parental permission for children’s internet accounts as well as parental supervision of child internet access; complaint procedures; informing producers of legal responsibilities for content; and making provision for the use of approved client and server side filters for overseas content.

According to Canning, filters indiscriminately restrict content and he cites the example of a Melbourne scientist working at St Vincent’s Hospital unable to access a HIV/AIDS website, receiving the message, “access denied: unsuitable content: full nudity, sexual acts/text, gross depictions/text.” This indicates the possibility that art sites with such depictions or texts could also be filtered. He anticipates increased self-censorship among artists as well as reduced accessibility to gay and lesbian artwork due to the imposition of film classifications which he claims are more severe than literature classifications. Rimmer says this is a matter of opinion. “The OFLC interpretations may not in fact be more stringent in the context of artworks. Scenario Urbano (Denis del Favero et al) have managed quite a lot in their video installations.”

On behalf of Adelaide-based arts ISP, Virtual Artists (va.com.au), artist Jesse Reynolds said that while he was wary of any internet regulation, the codes seemed useful for ISPs. “I think the codes are a positive step away from the complete nightmares of the new legislation. I certainly intend to steadfastly ignore the new legislation until such point as someone forces me to do something, then it will be kick up a stink time. Basically, I’ve got no truck with the legislation whatsoever. If we are forced to shut down servers for our clients, I’ll set up a VA mirror in the States and put the sites there instead.”

[INTENT]

According to John Rimmer, artistic context will be considered should complaints about online artwork be lodged with the ABA. “The classification process takes into account a range of matters and is required to look at literary or artistic merit as well as the intended audience. I personally find it hard to see that this sort of [artistic] activity is likely to be of great concern.”

[PROTECTION]

The Act seeks to restrict children’s access to explicit material by introducing a system for dealing with complaints from the public as well as for removing ‘offending’ content. Subsequently, material which is currently legal and available in other formats will be banned on the web. For Canning, the issue of protecting children is something of a furphy given that laws banning material such as child porn already exist. “I would say that it was a response to a media-induced moral panic about child safety online, a ‘beat-up’ in other words. But Senator Alston ran with that and made the law far harsher by, for example, using the film rather than literature classifications.”

In Bad Girls: the media, sex and feminism in the 90s (Allen and Unwin, 1997), Catharine Lumby argues that children’s interaction with virtual and real communities should be treated the same way. Rather than be excluded, children should receive warnings and be supervised: “adults have to work with children and help them negotiate unfamiliar information, situations and people.”

John Rimmer is particularly concerned about those aspects of the internet he describes as “in your face”, especially the ease with which users can unwittingly access pornography or email users can harass with or forward unsolicited material. Describing the intent of the legislation, he said it provides the community with an opportunity to complain about material they do not want available to children. “Its highest priority is sensible oversight of contexts in which material comes into contact with children. However, in itself, it does not replace the supervision of children while using the internet.”

[FEAR]

When Senator Alston said in an ABC interview that he aims to filter the web to create a “clean universe”, you have to wonder whether pornography is the target or the excuse, especially considering that the legislation was drafted to placate Brian Harradine, thus securing his Senate vote for the GST. There’s clearly a degree of fear and anxiety at play: anxiety about new technologies, fears for children and the risk of exposing them to adult sexuality, ‘moral panic’ about society as a whole. Catharine Lumby sees such fears as “unavoidably bound up with broader anxieties about the potential new media has to change people and traditional social and power structures and values.”

Describing a possible effect of this anxiety, Electronic Writing Research Ensemble Site Editor, Teri Hoskin, is concerned about the reliance that newcomers to digital technology will and do place on corporate entities, such as Ninemsn, to ‘guide’ them through the internet. “Playing on unfounded fears isn’t going to generate an environment of invention and experimentation. What we are increasingly seeing is the one-application-that-does-it-all syndrome, instead of an empowerment that relies on the agency of the user in forming networks and making accidental discoveries along the way. Perhaps (and with hope) this technophobia will die out as the kids of today gain more access to decision-making. They’ve grown up with a keyboard and screen.”

[ART]

The issue for the arts community is any possibility that this legislation will be applied to all internet content. Hoskin is tempering confidence with caution. “I really cannot see [a fuss] happening with art sites unless someone got a bee in their bonnet and wanted a scapegoat or wanted to test the scope of the law. Even though the legislation targets other types of content, I’m not convinced it’s in anyone’s best interests and I am wary of the potential for dangerous, unintended effects.”

The legislations seems to result in a community ‘dragnet’, with content, as distinct from entire websites, receiving Office of Film and Literature Classification ratings and regulation on a complaint basis. The prospect of restrictions on any explicit material including artworks, sexuality and health information looks real enough. Pursuant to the Act, R, RC or X rated content must be removed by order of the ABA. However, R rated content can remain if an Adult Verification Scheme (AVS) is in place. According to Canning, there are problems with the AVS which have resulted in reduced site visits. Search engines do not list sites using them and visitors are duly worried about privacy. Accessing art sites may not evoke the same privacy issues, but the obstacle of finding those sites remains.

While there are some generous considerations for artwork in the ABA’s deliberations, these are not absolute. The ABA determines the nature and context of the work, meaning that the demeanour of an artwork would be interpreted quite differently from pornography. According to John Rimmer, an internet porn site is obviously and inherently different in its character and intention from an artwork, even an artwork that appropriates porn.

Rimmer advised that the ABA applies administrative priorities in its processing of complaints. “The intention of the legislation is to obstruct access to pornographic material. Therefore, the ABA is more likely to address complaints about material of broader and more immediate concern, such as child pornography, than complaints about work produced for a consciously artistic context.”

[HACKED]

The ABA’s website was hacked on December 9, 1999. The following message appeared on its home page: “YOU CANT FUCKING CENSOR ME… if a message wants to get out..it will..leave it up to the au gov to make sure we stay in te dark ages… people only now can get connectivity USA has enjoyed for years…and now one of te greatest resources we gave for free speech and afree learning will be stifled by a vocal minority with no understanding of the underlying technology stand up now..and fight for your rights..if you want to be able to decide for YOURSELF what you can and cant read… i say once again…..LOUD and clear.. the internet is NOT a babysitter.. wou wouldnt let them roam the streets… dont let them roam the world… dont let your bad parenting spoil it for others… go buy a fucking clue.. ——— greetz and respect to the usuals.kat.etc.analognet. and barry heh…and a big FUCK YOU CNUTSUCKING SMEGWHORES to au gov.. clueless fucks… i digress.. adios… Ned R ——- p.s. admin.. dont bother..you wont trace me… and im not coming back here.. my point is made..if i get time one day ill secure it for you…luv and kisses.. Ned R—-pp.s My spelling sucked real bad cos i was high on methyldioxymethamphetamines and crack…”

RealTime issue #35 Feb-March 2000 pg. 20

© Linda Carroli; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Triple Alice 1999, Body Weather Laboratory

Did the event meet your expectations?

I’ve always thought it would be a burning point and it did prove itself as that, the sense of what that land gives off and the kind of energy it seems to produce in people. Financially, the whole thing was carried by the workshop. We had about 45-50 people regularly throughout the 3 weeks. Then we had another crew on top of that of about 14 people and writers, theorists and then local artists who joined us for different periods. The workshop was fabulous. We had a lot of people coming from Europe and some from Japan. There was a good mixture of people from all over Australia, not just the capital cities but really from all over.

What was a working day like?

Breakfast was at 6. We had a cooking team led by a wonderful macrobiotic cook and then we started training at 8, which we changed to 7.30 because it was just getting too hot. Whew! Sun! Boiler! Sweat! Drip! Dust! Within the first half hour the dust level was just massive and we were thick with this heat. Body weather is a literal workout, working up a sweat, working through different areas of the body. There are a lot of aspects to do with co-ordination, plus group body and individual body, timing and that sort of thing. But the actual sense of working outside is always an enormous thing in terms of what it does to focus and perspective. To have to generate the energy to meet that environment, it’s very big.

How do you establish the participants’ relationship with the landscape?

Basically by asking them to use their focus in different ways. Asking, for instance that the head travel and take in different relationships, to gauge what the eye is seeing without necessarily using point focus, to encourage a sense of scanning which is also to do with nomadic vision. Hunter-gatherers scan landscapes.

Then we’d move into manipulations, opening out and stretching and aligning the body. You’re in couples working with breath, weight and alignment in a quite fixed series of forms, gradually learning to gauge different parameters of the body and how to change and push border lines. That’s a much softer, quieter thing. So where the workout focuses and pulls in the body and contracts the muscles to a certain degree, this opens out the muscles and the borders. Then a lunch break and a rest in the heat of the middle of the day, to zonk out. But most people didn’t sleep. They slowed down, wrote a lot of notes, did their logs on the bank of computers, because I wanted to look at how the experience could exist on the net through the performers responding to a set of questions.

The afternoon was what I call groundwork which is more to do with basically opening up sensitivity to different speeds, practising how perception is altered working with mimetic relation to trees, grass, stalks, different elements of the rocks.

What do you mean by mimetic here?

Taking the body of the tree into your own body in an empathetic sense, trying to take the imagination of the molecules of that object and transferring that so that one gauges a different sense of being.

Duration becomes very important…

A whole set of durational relationships are established and worked through. One thing I wanted to do which I’ve never done before is to work 20 minutes regularly every day with slow movement, varying between one millimetre all the way up to 10 centimetres per second. I did that every day at about 2pm. I wanted to see what the effect would be.

We also did a lot of blind work and then, finally, the culmination of the workshop was in 2 elements. Firstly I asked people to put together small solos. They chose a particular place and they put together something that had a relationship to what they’d been doing over the 3 weeks. I let that stand as their individual investigation to get a relationship to the land. The other aspect was that I choreographed a series of exercises together, the effect of which was in a sense like a 20 minute performance. I was really happy with this because when I looked at it I thought, “Ah, we’ve caught the weather of the place! I had a really nice feeling about it. It felt absolutely, “ah yes, we got hold of it.”

You had Indigenous people coming by. How did they respond to what you were doing?

It had been planned that we’d have 13 women from Yuendumu who were due to come but there were 2 deaths so there was sorry business and they just couldn’t come at the last minute. I knew this might happen. So it was okay. We had a lot of discussions over the phone and so there’s a movement forward, and they’ve now invited me to go hunting with them. The 2 women who did come out—very interesting artists based in Alice Springs—had a fantastic time. They had their kids out with them. They taught us how to do some dot paintings and we did a communal painting together. It was more to do with talking. We set up social situations with the local artists, they came and visited mainly in the evenings and then they’d do slide showings of their work and we had a lot of poetry readings. We also had people who came as speakers—ethno-botanists, politicians, meteorologists, historians who know that area.

A lot of the local artists came and joined us which was very nice. The workshop was open to them if they wanted to join in. Some did and some stayed longer than others and were more engrossed in it. Then we did some collaborations. Watch this Space, the local artist-run co-operative in Alice Springs, were a major partner. A lot of their artists came up. They brought some of their installation materials and put them out in the land and then I concocted various relationships that the participants could enter into.

So what happens in stage 2?

We’re holding on to the core of the local artists and then inviting interstate artists to come and collaborate. In the main we’re looking at visual artists and particularly artists interested to work with the website. I won’t do a public workshop. I just want to work with a smaller group of people who are doing a higher level of research at a more professional level. And I’d really like to move into another level entirely on the web to see what can happen with Triple Alice in this place and in virtual space.

–

Triple Alice, Hamilton Downs, September 20 – October 10, 1999. www.triplealice.net

RealTime issue #35 Feb-March 2000 pg. 9

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

No Other Symptoms. Time Travelling with Rosalind Brodsky

CD-ROM Suzanne Treister

No Other Symptoms. Time Travelling with Rosalind Brodsky

Rosalind Brodsky could very well be the alter ego of artist Suzanne Treister who bears strange similarities to this time travelling scientist, tracing her European Jewish ancestry while still engaging in a plethora of eccentric occupations and activities.These change from psychoanalytical sessions with deceased therapists to preparing traditional German dishes, to performing in her psychedelic rock band, to developing a range of designer vibrators. The recommended viewing time for this CD-ROM is 3 hours, the amount of time necessary to fully explore and participate in her time travelling tales.

The date is 2058, the year of Brodsky’s death and the setting is the Institute of Militronics and Advanced Time Interventionality, where Brodsky conducted her research and still lingers. The virtual space is more digital collage than animation. Brightly coloured juxtapositions of furniture, wall hangings and retro sci-fi machines. As in a computer game simulation, you travel through the space by a few clicks of the mouse. Like a virtual tour there are characteristics such as a map, a guide and various info areas. Once in Brodsky’s study you can time travel to her home in Bavaria, modelled on Koningssschlos Neuschwanstein, the original home of the “mad” King Ludwig, and more recently to neo-Nazi squatters. There are also options to explore her diary, or go down a level to the clinics where Brodsky regularly received counselling by Freud, Jung, Klein, Lacan and Kristeva. Inside the institute you are informed by the Introscan TV Corporation that a group of armed academics are demonstrating outside, and time travel is the only means of escape. As in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the closet leads on to other destinations, not Narnia, but the very 20th century cultures of the Russian Revolution, the Holocaust and swinging 60s London.

A quicktime movie shows a haunting dual image of the train tracks leading to Auschwitz. A recurring theme is Brodsky’s attempts to rescue her grandparents from World War 2. She is the silver clad futuristic time-traveller, superimposed over black and white footage of war-torn Europe. At other times she is part of a Monty Python-esque collage, posing next to key figures from cult films such as Norman Bates and Mary Poppins. Also in the wardrobe are Brodsky’s attache cases. In order to fund her projects, Brodsky appears to have developed a range of designer vibrators. These range from the architectural variety, such as the Kremlin and the “double sided” London Bridge, to key political figures like Marx and Lenin and pop culture icons Emma Peel and David Bowie. By clicking on the speech bubble, each sex aid literally “speaks” for itself. Sexy science seems to be the name of the game and food is a constant delight on the journey.

Some startling new developments have enabled the Nutragenetica Corporation to begin harvesting chicken legs on human torsos, and Brodsky, like any traditional Jewish hostess, seems right at home with these new condiments. A TV in the bedroom plays snippets from her cooking show, as well as the music videos Brodsky made with her band, Rosalind Brodsky and the Satellites of Lvov. The remake of Lou Reed’s Satellite of Lvov is a trippy track involving sci-fi theremin sounds and Glam rock beats. It regularly comes bleeping through the castle corridors.

Travelling further, you become familiar with the interactive vocabulary of Brodsky’s creation. Big buttons need to be pushed, cursor “R” turns to cursor “B” at select moments, rollovers light up and footstep sounds signify you’ve arrived.

When the final destination is reached— satellite probe (a Christo wrapped Reichstag)—it appears that Brodsky in her old age transformed most of her archival research into a painting game, a virtual kinetic colouring-in book, where multiplying vibrators can be placed over varying backgrounds, such as Mars and Shinjuiku, Tokyo. It gets more bizarre as the final choice on the tour is to return to the Castle music room, and play some more, or get dropped off in the Australian mining town of Coober Pedy!

Despite the idea of transcending time, the work has a set narrative with pre-determined choices and specific geographical locations that lead onto the next stage. At one point, Brodsky describes herself as a “necrophiliac invader of spaces containing the deaths of her ancestors, through the privileged violence of technology.” Using this violence of technology, Treister has enabled us to invade many facets of her anthropological history. And what a ride it is.

Time Travelling with Rosalind Brodsky, Suzanne Treister, Black Dog Publishing Limited, UK.

RealTime issue #35 Feb-March 2000 pg.

© Joni Taylor; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net