Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Nicola Loder, Untitled

Orbital was an ambitious exhibition of time-based media installations, simultaneously held in Melbourne and London. It featured 5 new media artworks by Australian artists Nicola Loader, Megan Jones, Nigel Helyer, Margie Medlin, Brook Andrew and Raymond Peer.

The first thing that struck me as I walked into the CCP gallery space (Gallery 1) was Nigel Helyer’s Ariel, a luminous lime-green and lemon interactive sound sculpture installation described in the catalogue as “a sensor based ecosystem of mutant jellyfish-like radio objects which respond to the physical presence of a human interface.” In the catalogue Helyer reflects on his work as “a sonic-mapping of voices lost in the ether, of song long settled in the dust.” Fugitive sounds, with all of their associated resonance, vibrated and echoed in this labyrinthine soundscape.

Voices speaking to each other were affecting in different ways in Nicola Loder’s monitor-based digital video installation. A wall of monitors simultaneously screened 5 sets of strangers interacting with each other in a neutral photographic studio space. This mise-en-scene of blank white background focused further attention on the people and their conversations. Each monitor had its own set of earphones which enabled a semi-voyeuristic listening-in to encounters which were variously polemical, topical, intimate, sometimes even indifferent. Positioned as an acousmetre, I had memories of Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window, in its invitation to multiple intrusiveness.

Megan Jones’ Sites of Interception, on the other hand, was clearly a work whose purpose was both educational and political. This multimedia installation invites viewers to look at satellite imagery of the Murray Darling Basin in the Sunraysia region of Victoria, to explore Quicktime VR 360-degree panoramic environments of the region. Megan’s CD-ROM was created in consultation with the Salinity Management Consortium as a SunRISE 21 Artist in Industry project and explores the sustainability of the Sunraysia region in the 21st century. The pathways through these topographical images, however, often transcended their informational function. There was at times a poetic feeling of place in the images of vastness and proximity, in the comparisons of the parched and the lush landscapes.

In the second gallery space there were 2 installations, one on each side of the room, a space enveloped in images, flickering constantly. On one side Margie Medlin’s monitor-based digital media installation, Estate, focused on the nexus between dance, film and digital media. A kinetic dancer traverses a montage of digital images of Australian and Asian cities. A dance of the figural, in the unlikely milieu of an ever-expanding urban vista.

On the other side was BIYT/me/I (BODILY INSTINCT YEARNING TECHNOLOGY/multiplying emptiness/Identity), a digital video projection-based installation directed by Brook Andrew and choreographed by Raymond Peer. The intention of this installation was to give Wiradjuri (Aboriginal) and Assyrian perspectives of an Australian landscape. A multiple madness of images is navigated through 3 Australian identities. These figures are an Aboriginal surveyor re-mapping a city landscape, an Assyrian business man locked in a twilight zone of a train station trying to scale the capitalist terrain, and a displaced German woman living out of a trolley filled with both European and Australian objects. These narratives intersect and parallel one another, creating a complex cityscape tableau.

Orbital’s accomplishments were highlighted in the different conceptions and visions of Australia represented: from the sonic echoes of the past to the hesitant meetings of strangers; from the vast and sparsely inhabited landscape to the bustling city streets and metropolises. The invitation of this exhibition was to reflect on the many ways that we have, and continue to, imagine ourselves in the many places that we live.

Orbital: visions of a future Australian landscape, curator Keely Macarow, Experimenta Media Arts, an associated event of the Australia Council’s HeadsUp Australia 100 festival, London, Lux Gallery, London, July 2-9; Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne, July 6-29.

RealTime issue #39 Oct-Nov 2000 pg. 31

© Anna Dzenis; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

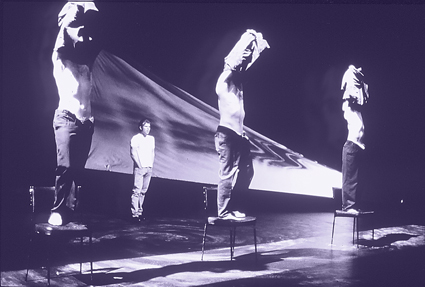

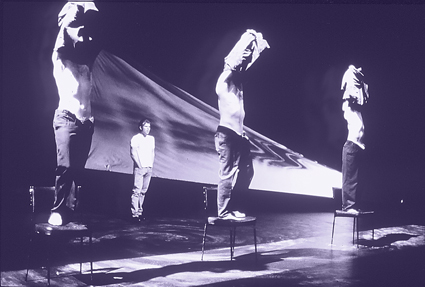

David Tyndall, Sarah-Jane Howard, Luke Smiles, Chunky Move, Hydra

photo Jeff Busby

David Tyndall, Sarah-Jane Howard, Luke Smiles, Chunky Move, Hydra

According to anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss, mythology is the means by which society expresses the mysteries of existence. These enigmas are not apparent to the naked eye. Rather, they lie beneath the surface of the stories we tell ourselves, locked in deadly embrace. If Levi-Strauss is right, then Chunky Move’s Hydra is a work of mythic proportions. The name and its surrounding publicity suggest a mythical inspiration for the work, but it is also possible to interpret Hydra in the narrower sense suggested by Levi-Strauss—as standing for the irreducible conflicts that underlie human existence.

Hydra opens with twining figures who seethe through the shallows. These sexual creatures seem not of this world. Their wetsuit flesh suggests that they hail from the depths, whether of mind or matter we do not know. Their natural habitat is below, underneath the surface. Contrast these beings with what appear to be humans whose dress is urbane and whose movement tells a different tale. These mortals lurch through space, throwing themselves from situation to situation. They are not in control. They expend energy but life speaks through them, they do not speak it. Almost somnambulist, their lexicon of movement reminds me of B-grade zombie films.

The set of Hydra connects and separates the two levels of reality represented by each type of being. It consists of a shallow pool of water, covered by a removable wooden floor. As the work progresses we see land become water become land again, through a series of deformations and reformations. When the land level is lifted, the structure looks like the inside of Moby Dick—a large wooden ribcage.

The water creatures are pitted against the humans. There is no love lost between them. Yet, the humans must interact with the water. They fall into it, fall out of it, they lie across its boundaries. Although none of the beings in this landscape exhibit anything as explicit as consciousness, each will destroy the other if occasion allows. Some wonderful duets and trios occur betwixt and between these creatures.

Whatever Hydra is about, and not knowing is a strength of the piece, it is clear that it represents conflict. For Levi-Strauss, the inability to resolve the fundamental contradictions of human existence is the lifeblood of myth. Myth covers over that inability, somehow pretending a resolution; through what we might call narrative closure. At the end of Hydra, the wooden floor is reassembled. An uneasy peace reigns but not all is resolved.

The last section of Hydra involves a live performance by Michael Kieran Harvey on piano and Miwako Abe on violin. Repeated waves of musical consciousness lap the action, lulling us into stillness. The otherworldly temporality of the music breaks any sense that the end of the work is an earthly one. Rather, there is an ineluctable movement towards a truce, one which leaves everyone drained. The sense is meditative.

What then are we left with? Hydra can be seen as a battle between oppositional forces, perhaps where man=culture and woman=nature (not again). But it is richer than that. Firstly, the mortals’ movements are complex; they are definitely skilful yet they manifest a human fallibility. Choreographer Gideon Obarzanek leaves the world of displayed virtuosity for something else here. Secondly, there are several fine kinaesthetic interchanges, duets and trios, which need not be reduced to a single storyline. I like the abstraction that washes over Hydra. It’s thoughtful. If it is about the conflicts of myth, these dwell way beneath consciousness. It is not for us to plumb the depths of each and every mystery.

–

Hydra, Chunky Move, choreography Gideon Obarzanek in collaboration with dancers Fiona Cameron, Luke Smiles, Kathryn Dunn, Sarah-Jayne Howard, Michelle Heaven, David Tyndall, Stephanie Lake; musical composition James Gordon-Anderson, Darrin Verhagen; design Bluebottle, National Theatre, Melbourne, August 2-12.

RealTime issue #39 Oct-Nov 2000 pg. 39

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Kate Denborough, Birthday

Although Kate Denborough’s Birthday involves 2 members of the crew’s immediate family, it has a solo ring to it. This is because the feelings of the piece centre around Denborough’s existential self-questioning. Birthdays can do that to you, sometimes creating solitude in the midst of celebration.

The set is small. A little bit of a house comes crashing down. A party is held. The audience are the party, that is, apart from Kate who does everything. She even plays her own party games amidst a choreography of excitement. Funny how sad it all seems. The bigger the gesticulation, the emptier the gesture. Finally, a headpiece is revealed, a sort of silver galaxy with orbiting blue lights. When the headgear is fitted, the piece changes from witty, funky, and sad to surreal. This is the largest danced section of the piece—a mixture of beautifully shaped legs and turns and tottering unknowingness, turned inside out. The walls of this small universe provide anchorage but not direction.

It takes Dad (Michael Denborough) to bring his daughter out of her existential nausea with cake and champagne. Unfortunately, he fades away, his mortality getting the better of him, leaving our hero alone again. The wall momentarily functions as an artificial partner, absorbing the betrayal of loss. But how good can a wall be? Luckily, youth saves the day and dashes across the stage to grab a mouthful of cake. We leave Kate seated by the young musician (Christopher Bolton), having her cake and eating it too. A thoughtful piece that comes from a deep emotional place. Three cheers.

Birthday, choreography Kate Denborough, direction John Bolton, performers Kate Denborough, Michael Denborough, Christopher Bolton, design Ben Cobham, Kristin Green, sound Franc Tetaz; CUB. Malthouse, September 14-16.

RealTime issue #39 Oct-Nov 2000 pg. 38

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Yumi Umiumare, INORI-in-visible

photo Brad Hick

Yumi Umiumare, INORI-in-visible

“I like smashing things,” Margaret Trail confessed in K-ting!. It was a fortnight of ‘smashing’ in Melbourne, from Chunky Move’s exploding set floor in their Hydra (shades of John Carpenter’s The Thing) to Yumi Umiumare’s evocation of the Hanshin earthquake in her Mixed Metaphor piece INORI-in-visible. Artaud’s exclamation that “The sky has gone mad!” was repetitively rendered on stage.

The Mixed Metaphor artists were obsessed with language, or languages—their layering, mutual incompatibility and paradoxical similarity. Dancehouse was filled with projected text, surtitles, interrupted whispers, mangled soundtracks, bodies both literally and metaphorically inscribed in a way affective and yet impossible to fully know. Metaphors of likeness and unlikeness, these are works inhabiting a realm between holistic unity and irreducible multiplicity.

A new space is opened up in the creation of a performance which is like a performance (rather than ‘like nature’); metaphors about metaphors. Susie Fraser for example, offered us the doubled spectacle of watching a mother watching her experience of motherhood, represented by diary entries, medical reports, home video and more. Her confession however left much unsaid. Similarly dancer/choreographer Jodie Farrugia projected a mysterious book above the dancers, containing poses that they appeared preordained to echo. A partial revelation of the inaccessibility of destiny as semi-unconscious accord.

Full revelation was perpetually offered yet denied the audience. Various texts bound these performances together whilst allowing one to glimpse through them towards something else—aporia perhaps. The performances were vertiginous in their very materiality, creating the possibility of a metaphoric conflation and conflagration of the word.

In this respect, Trail’s K-ting! was the most absorbing, and frighteningly funny, work. Scored to a complex deconstruction and montage of pieces torn from some unknowable and apparently absurd conversation or conversations (“Are you really a fireman?” she remarked), the text was constantly interrupted by the sound of smashing crockery and other materials. Each misplaced phoneme shattered the veneer of normality, raising the almost literally hysterical possibility of social opprobrium and embarrassment (“What is…what is it…it is…this really quite unpleasant thing we do?”).

Trail stood largely at ease in the centre of this vortex of mistakes, Freudian slips and alliterated nonsense, pondering and imperfectly miming under the spotlight. She acted as a performer performing someone not performing—not really, not in any overt way. The subject-hood of the scored ‘characters’ she interacted with was provisionally and variously defined by the name they answered to—“I’m super-model Margaret”, “I’m fireman Jeff”. Trail dramatised how all conversation and recognition occurs under the threat of potentially sublime linguistic breakage or meltdown (“k-ting!”).

Lest one seek refuge in the idea of a pre-linguistic body, Trail exemplified the tendency of the performers to dramatise the body as a parallel, coded presence. Her physical performance consisted of a series of abstract yet implicitly communicative gestures: arms raised, hands spread wide and shaken in frustration, or fingers curled delicately as they described the space that bathed and sustained the subject. Though these actions ‘touched’ the recorded vocalisations, they never followed the same logic or pathway—meta-performance perhaps. The poses recurred and frayed, like old phrases becoming increasingly meaningless or overloaded through use. The body struggling against becoming a cliche. Of what? Of itself.

Compared to Trail’s thoughtful, at times ecstatic, implicitly sexual linguistic farce, Yumi Umiumare’s performance was immediately disturbing. Should one laugh? Is it okay to laugh at someone else’s horror? Can an Anglophone laugh when berated in Japanese without appearing insensitive or culturally smug? Aural hieroglyphs from the perspective of the Anglophone, words transformed—transfixed—rendered as ‘pure’ sound or affect by cultural and geographic distance.

Umiumare entertained her audience, but she did not let them off lightly. She was, however, more reluctant than Trail to revel in smashing. The sticks she wielded acted as ambiguous talismans of the quake zone, memory and experience.

The core of the performance was Umiumare ‘re-enacting’, trying to phone her relatives in Hanshin. “Hello?…Hello?…Hello?” Echoing calls degenerating into violent, hysterical shouts, and even a psychic space outside of this. An implosion of space, time and emotion. The venue becomes an abstract, mnemonic theatre in which Umiumare imagines an event she herself was denied. The walls’ “shake” she mimed for us, breaking through language for a moment. Umiumare’s adoption of an almost childlike, tragically playful performance mode suffused the space with an overwhelming sense of presence and absence, of felt pain and the impossibility of its recapture. One moved from Trail’s almost orgiastic celebration of smashing, to Umiumare’s ambivalent attempt to recapture it.

Mixed Metaphor, Separate at Earth, video installation Cazerine Barry; Stories From The Interior…Shedding, writing/direction/performance Susie Fraser, video Lisa Philip-Harbutt, dramaturgy Sue Formby. In Outside, direction/choreography/performance Jodie Farrugia, performer/collaborators Dylan Hodda, Rowan Marchingo, video Dermot Egan. K-ting!, writing/direction/performance/sound Margaret Trail. Operation in the Middle of Things, creation/performance Tim Davey. INORI-in-visible, creation/performance Yumi Umiumare, set Anthony Pelchen, sound Tatsuyoshi Kawabata. Lighting (all works) Nik Pajanti. Dancehouse, Melbourne, July 27-August 6.

RealTime issue #39 Oct-Nov 2000 pg. 38

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Michael Pearce, Flow

Michael Pearce is a well established stage and costume designer for dance and recently won a Green Room Award (his second) for the set and costumes in James Kudelka’s Book of Alleged Dances (Australian Ballet). His latest solo exhibition, Flow, was inspired by an Asialink residency in Hanoi.

A series of drawings were hung on gallery walls, some overflowing onto the floor. They were shaped like Chinese wall hangings but their content was different. Most of the drawings were of body parts; feet, head, face, wrist, arms. Their vivid colours reminded me of the impressionists’ deconstruction of white light into the spectrum but in this case, the subject was a body in movement. Even in stillness, the impressionists’ concern was with the animation that makes a body alive. My favourite piece was a pair of feet, lapping the floor from the wall. In this interpretation, you could feel the history of practice that has formed this particular pair of feet, the uneven weight distribution, the irregularities of its toes.

Pearce used a ghosting technique to suggest a trace, a not-quite presence related to the very palpable flesh of his work. Even the parchment began to look like skin to me. I was reminded a little of this year’s Sydney Biennale exhibitor, Adriana Varejao, but where her flesh is thrust in your face, Michael’s very gently emerges somewhere between you and the work.

Flow, drawing installation by Michael Pearce, The Counihan Gallery, Brunswick, August 17 – September 3.

RealTime issue #39 Oct-Nov 2000 pg. 38

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Triple Bill opened the Brisbane Powerhouse’s inaugural l’attitude 27°5, an annual event of contemporary independent performance intended to showcase risk-taking fusions of dance, music, and installation art alongside forums, workshops and masterclasses. Curated by Zane Trow and Gail Hewton, the intention is to support independent artists and small companies by providing a platform to make new work, assistance to build networks including residencies with visiting overseas artists, and the connections to get their work shown beyond Brisbane. l’attitude 27°5 offers 3 weeks focusing on Australian dance and installation artists beginning with 3 new works by Brisbane choreographers.

Shaaron Boughen’s Bleeding-A-Part is a moody exploration of love, desire, manipulation and obsession, sensuously danced by Fiona Malone with Tim Davey. Three scrim screens providing layering and texture initially veil the duo. She approaches, he rejects…they move to the next screen, each time she adds clothing items—layers—of separation. Susan Hawkins’ deftly crafted soundscape of cello, piano, and spoken text gives body and substance to the whole. More layers—tips for young women from the Vogue beauty book, a manual on preparing rabbit carcasses, love scenes from Cole Porter, the laboratory dissection of a rat, erotic secrets of an imaginary lover—words juxtaposed against movement driven by the feminine point of view. Always the female wooing, the male resisting, rigid, passive. By contrast, his narrative is left unpenetrated. A prop for her to propel herself relentlessly against—towards—hurling her desire at him, recoiling from his touch.

The highlight: a haunting screen projection, dancing with the narcissistic ghost image of herself as her lover, a her-him, before the image dissolves into ‘he’ and therefore turns away from her once more. Artfully realised, Bleeding-A-Part seems resigned in its mild meditation on the ambiguity of a hunger for desire with no messy, juicy bits.

Fugu San. Space made tangible. Sliced. Shifted. Sculpted. Fugu San is not alone but in pas-de-deux with her environment. The first sound from the darkness is a rhythmic knocking beat. A shaft of light slowly reveals the pounding of crimson pink pointe shoes like pistons into the floor. Above, Lisa O’Neill, austere in black, and seemingly still. For 6 minutes the pointe shoe generator rumbles under black skirt, an engine building up a charge, whilst oblivious, the arms, torso, head explore the space they occupy. Behind her, Emma Pursey cuts a dramatic presence as the gothic mistress before a glass cabinet of sound, mixing live from her potions on vinyl.

O’Neill is a vital performer, more than just the pay-off of her disciplined training—Suzuki on top of an orthodox dance background. Absorbed in kinetic ritual we are absorbed in her absorption. She manipulates space and time with mesmerising nuances.

Disappearing down a hazy passage of yellow light. Emerging from another, icy blue. Symmetry informs the work, an architectural geometry in design of body movement and staging that is used to underscore mood. And the hint of a Japanese aesthetic? (The title, I am informed, is a nickname meaning ‘blowfish’ but does not bear directly on the work.)

It’s not just a matter of body control and focus. Highlighting this, the third movement, a variation with grand pliés in first, momentarily loses that unmeasurable quality despite unwavering focus and control. A subtle shift, and I feel the movements are suddenly no longer satisfying her but made for us. Why…to extend the work, fill a quota?

Another exit: hip-rib-shift-elbow-leg heel-flick-land-look-pause….Eyes in her feet, in all her body parts. Querying, questioning, quirky feet. Despite the brief lapse, O’Neill’s Fugu San is powerful, playful. With no agenda, it demands no explanation. One could charge O’Neill with conservative formalism, or banal decorativism, but Fugu San transcends that by the shamanic power of the performer. With a noble reticence to disclose her secret narrative, Fugu San does not invite us, she simply embarks on her mysterious journey, and I want to follow.

The set of Monster loosely suggests a Hammer horror, its gothic doorway, its drapes splattered in lipstick pink blood. A scream in the dark. Now he takes it back. “What, did you think I’d serve you up a monster just like that?…Fuck off!” Monster is a highly personal work for dance and text by Brian Lucas, supported by Brett Collery’s eloquent soundscape, claiming to explore the iconography of Frankenstein’s monster, the politics of the monstrous and the monster within, but weighted towards the relationship break-down that drives it, sparking the inquiry into monsters but never really descending into the deep. These are the monsters of bad faith. There are 10 ways to hit out at the lover who deserted you—stapling his trouser legs, hiding 6 pork chops around the apartment, outing the beloved to his father.

As if writer, performer and choreographer all knew each other, Lucas presents a hybrid performance piece where movement and text arise out of the same impulse; a self critiquing narrative that turns over and over, folding in upon itself whilst winding its way forward through love story, childhood reverie, the father’s story, the lover’s revenge. “One! Two! Three! Four!…such a Control Freak!” Lucas parodies his choreographer, himself. Dad-monster shuffles and swears—“Pigs Arse yer Cunt!”—his fingers wobbling.

The demanding range of performance skills is delivered with assurance, seamlessly moving between dance and dialogue, between multiple strands of narrative: creator/creature, father/son, lover/beloved, choreographer/performer. But skirting the truly monstrous, monsters of domestic pettiness prevail, pivoting on loss of self esteem. For me, only his monstrous father evoked the kind of revulsion and pity that challenged.

Is this self expression made art or an effort to make artistic capital out of a surplus of self? Is this monster a power-freak manipulating us into condoning and approving of his monstrosity? Surely perpetual irony cancels itself out. By setting up and pulling down, Lucas wants to have his cake and eat it too: brave, raw exposé and self-absorbed relationship therapy. Whilst compellingly performed, I feel Lucas relies on a sophisticated complicity from his audience, implicating us in his revenge tactic no. 5: to “analyse his relationship breakdown in a performance piece.” How monstrously decadent!

Triple Bill, Bleeding-A-Part, director/designer Shaaron Boughen, writer Michael Richards, dancers Tim Davey, Fiona Malone; Fugu San, created and performed by Lisa O’Neill; Monster, created and performed by Brian Lucas; l’attitude 27°5, curators Zane Trow, Gail Hewton: Visy Theatre, Brisbane Powerhouse, September 5-17

RealTime issue #39 Oct-Nov 2000 pg. 39

© Indija Mahjoeddin; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Rachel Pybus, Kyra Pybus, Oscillate Youth Dance Collective, Scarabs

According to the program for the 4 free performances given by Oscillate Youth Dance Collective, Hobart is Australia’s only capital city whose university does not offer tuition in the discipline of dance. While there are private teachers and classes, for many dance students Year 12 is where the formal training and experimentation stop.

The consequent lack of resources and opportunities—and of avenues to perform and present “dance as an accessible conceptual medium”—are motives behind the formation of Oscillate (Kyra and Rachel Pybus, Jasmin Rattray, Jessica Rumbold, Tullia Chung-Tilley, Edwina Morris). The group acknowledges the inspiration and support provided by dance teacher Lesley Graham.

The dancers share a background in dance/contemporary movement/choreography studies (Years 11 & 12) at Rosny College and have recent experience in the Hobart Fringe Festival, plus individual work with dance companies Tasdance and Par Avion. Scarabs was danced and choreographed by all Oscillate members and devised in partnership with the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery that has, over the past few years, presented a number of innovative dance works with related exhibitions.

The 30-minute performance features ingenious costuming (inspired by the Museum’s extensive beetle collection), a unique, custom-mixed soundtrack that is more an eclectic mix of sounds and rhythms than music (“stomachy sounds” as one dancer put it at the post-performance forum) and a simple and effective lighting design. The piece worked well as a site-specific dance installation, responding to its intimate gallery space.

The work is deceptively simple, with barefoot performers in costumes suggesting the iridescent winged surface of the scarab beetle. Each dancer enters with her back to the audience. As she turns, she is revealed to be ‘gagged’ by a beetle-shaped mouthpiece, its sexual and violent overtones inescapable, even if perhaps not part of the ensemble’s intentions. The scarab beetle theme and the group’s fascination with the museum’s displays give this essentially abstract dancework a strong coherency.

Initially, subtle movements are made in synch; then the choreography expands with each dancer performing her own variations, while still reacting to and with the rest of the troupe. The collaborative choreography is, just occasionally, derivative, but overall the gestures and sequences are attention-getting—good, athletic contemporary dance. The beetle theme is well maintained, giving the performance an other-worldliness wisely free of movement mimicry.

The standard of dance is high; it is evident that some Oscillate dancers have experience in gymnastics and aerobics. A highlight is one dancer who has virtually mastered the knack of barefoot pointe dancing.

The printed program is a useful extra detail to a very professional work, the catalogue essay expanding on the dancers’ concerns and inspirations. With its genesis in a ‘brainstorming’ creative process and the product of 4 months’ collaborative work, Scarabs is a worthwhile project successfully brought to fruition and clearly much enjoyed by a responsive, standing-room-only audience.

Scarabs, performance installation by emerging choreographers, Oscillate Youth Dance Collective, Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery, July 20 – 23

RealTime issue #39 Oct-Nov 2000 pg. 7

© Di Klaosen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lucy Guerin

photo Ross Bird

Lucy Guerin

The Ends of Things, your new work for the Melbourne Festival has an intriguing title. Where did it come from?

Originally from a composer I worked with, Jad McAdam. It was his idea and it grew out of a sound idea really, to do with creating a score from sounds of finality. Like the end of a record or the tone after someone has hung up on you on the telephone, or when a film reel comes to an end and you hear a clacking noise. There are a lot of different sounds of things running out and ending and television going off the air. So rather than in a huge cataclysmic, catastrophic way it was more like that empty hollow sense of endings.

How have you chosen to work with that idea?

That was difficult because I did a development period on the piece earlier in the year and I thought that I would use all these gestures of finality and I’d set up these situations that had this emotional tone of endings. But it became extremely difficult. I realised that to create a sense of endings without anything going before it was almost impossible for me. Also I found it very, very draining and found myself not really being able to get into the process that much during the development period which was in January. So I let myself wander a bit with it and get off the track a little bit and just try out a few things, but that ended fairly inconclusively. Since then I’ve thought about it a lot and I’ve developed more of an overall structure, which will have more of a beginning, middle and end. And within that structure these little final moments will present themselves. So they’ll set the emotional tone of the piece; but there will be a greater end as well, almost like the end of a narrative.

It sounds like it has the potential to be quite bleak.

Yes, well it does. And that was one of the other things that was worrying me about it, actually. I didn’t really want to make a piece that was completely dark. But having thought about it, I’ve sort of made Trevor Patrick the central character. He has this very dry, interesting sense of humour and he’s sort of like a character. It’s almost like his life. The dancers represent more the workings of his mind or his past or his fears—they are more like his psychological state. So I think it will probably end up being fairly bleak in the final scene but there will be quite a bit of humour before that, slightly black humour, but it won’t all be dirge-y and doom ridden.

Your work is often marked by that mischievous wit and dry humour.

Yes, I think that will be in there, definitely, especially in the first scene where we set him up in his little environment. Yes, but I won’t give too much away.

Is there a narrative thread that runs through this at all or is it predominantly an abstract work?

No, it is actually quite narrative, much more narrative than works I’ve done previously. So I feel like I’m trying to have both worlds in this work. I do have this narrative character who is isolated pretty much for the first two sections of the work. We pick him up at a certain time in his life where he’s become quite withdrawn from the world and he’s obviously a fairly sensitive character who can’t really deal with the pace of things outside of his own room. He’s at a point where his isolation and cutting off from people is just starting to cause his world to disintegrate and he is losing connection with reality. Hence things running out. The Ends of Things ultimately relates to the end of control or reason, so he’s losing it a bit. It is a bit bleak in that way.

It also sounds interesting that you are actually tackling that way of making work.

Yes, it’s quite psychological.

Is that new for you?

I think I’ve always felt when I’ve made works that I was entering a psychological state or getting into a particular zone of psychology. But I haven’t actually defined a character before as specifically as I am this time. Well, I suppose that when I did Robbery Waitress on Bail, I wanted that mood of the suburban teenager and that sort of frustration and hopelessness. But it was more through just an emotional tone. This time I’m being a little more specific with myself about who this person is. So I suppose it’s more like a writer would research their character. And I don’t know what’s going to happen because I haven’t worked this way before and it will be interesting to see if that’s helpful or hindering when it comes to this next rehearsal period and creating the movement.

Is that specificity going to be clearly interpreted by the audience?

Yes, I want it to transfer to the audience, to be quite simple and straightforward, which is something I haven’t really done before. I mean I think I was quite happy for people to enter a more dramatic realm but I wasn’t too fussed if they got exactly what was going on. In fact, it wasn’t necessary for me at all. This time I’m really interested in them knowing what the situation is. I still haven’t quite figured out how I’m going to get people to realise that the other dancers are what’s going on inside his head. Because, I don’t know, maybe you need these really obvious voiceovers or signs coming down or someone coming out and making an announcement. I hope not.

Is this new interest something that’s been prompted by making work in Australia?

It’s partly to do with making work here in Australia because when I made work in New York my main audience were other choreographers and dancers or other people from the art world who really easily accept abstraction and don’t feel threatened by it at all. If they don’t understand it they’re quite happy to make an attempt to engage with it anyway. And that was great except that you do start to work within a bubble in a way that’s not really connected to anybody else. It’s art for artists in a way.

There has been a lot of talk about making what we do accessible to a wider audience.

Yes, but I think a lot of that has to do with wanting to sell more tickets and create more income, which is not my main interest. I find it quite challenging for myself to actually be clearer about what I mean and not be afraid for people to know what it is. So that you are a bit more exposed, you are a bit more revealed if you actually say it straight out. I think a lot of artists are afraid of that. I think I have been.

–

The Ends of Things, choreographer Lucy Guerin, composer Franc Tetaz, dancers Ros Warby, Trevor Patrick, Brett Daffy, Stephanie Lake; design Dorotka Sapinska, dramaturg Tom Wright; Lucy Guerin Company, Melbourne International Festival, National Theatre, October 20-28.

RealTime issue #39 Oct-Nov 2000 pg. 37

© Shaun McLeod; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Junction Theatre & Leigh Warren Dancers, Piercing the Skin

photo Alex Makeyev

Junction Theatre & Leigh Warren Dancers, Piercing the Skin

English playwright Martin Crimp’s late 80’s satire on Thatcherite conservatism, Play With Repeats, has been reprised in a quietly effective production at the ADT’s Balcony Theatre. In a one-off production, director Chris Drummond guided his strong ensemble through the bleak netherworld of the central character Anthony Steadman (played with naïve fanaticism by Geoff Revell). Steadman inhabits a limbo of desolate urban spaces like some latter day Candide, energised by a kind of intuitive optimism that “everything is possible.”

Steadman is an amiable, unambitious low-tech worker in a hi-fi factory whose blind faith belies the deep cynicism and depressive fear of most of the characters that he comes into contact with: embittered fellow travellers at the bar—Kate (Jacqueline Cook) and Nick (Justin Moore), and Steadman’s harried boss Franky (effectively doubled by Cook). This white-collar subsistence world is stripped of meaning by economic rationalism, where cynicism is the strongest bulwark against despair. Steadman tries to further understand his world by employing the services of Lamine, a shabby, irascible clairvoyant (played with shuffling pomposity by Phil Spruce). But Steadman’s utopian alternative to the post-industrial wasteland he inhabits is revealed to be a nostalgic neo-Victorian conservatism connoted by visions of grand houses and sweeping gardens. His real nature is finally revealed when he tramples the only real possibility for human warmth and companionship held out by Barbara (interpreted with fragile sincerity by Cathy Adamek).

With some great jazz by music director Julian Ferraretto, and effective, functional stage design by Gaelle Mellis, Play with Repeats still has metaphoric resonance today, giving us pause to reflect on what we have lost or gained through the past 10 years of fundamental economic change. Who has benefited from that change and at what cost to community values?

Community and attendant notions of connection and alienation are explored in 2 other recent arts events in Adelaide. Piercing the Skin and Body Art have peeled back epidermis Australis with striking results.

The human body as post-structural icon scarified by the twin forces of identity and power is a popular theme in contemporary arts and culture. “The body is both a playground and a battlefield; the site where the greatest tenderness occurs and the most brutal inequality is acted out,” says Vanessa Baird of the New Internationalist-inspired Piercing The Skin, a performance collage of impressive quality and diversity performed last month by Junction Theatre and Leigh Warren Dancers.

The companies jointly commissioned 5 distinctly different writers (Rodney Hall, Stephen House, Eva Johnson, Verity Laughton and Paul Rees) to interpret Baird’s sentiment. The result was a series of vignettes, each exploring broad connections of time and space, language and subcultures in an eclectic interplay of styles. Eva Johnson’s The Body Born Indigenous 1 & 2 took the form of a piquant ode to identity and sense of place, while Paul Rees chose a monologue for Spare Parts (1&2), a mordant apologia for body-part farming (the ultimate rationalization of the individual?). Verity Laughton created a vivid poetic dialogue for Fox, a forensic whodunit spanning 1000 years. Stephen House’s expressionistic Walk In the Dirt and Rodney Hall’s The Self, a satiric examination of gender and difference, rounded out the conceptual kaleidoscope.

Rather than appearing a stylistic hotpotch, I thought Piercing the Skin achieved a real sense of playful connection—a spirit of co-operation that has spilt over into future joint projects mooted for the 2 companies.

Skin piercing took on a decidedly more permanent connotation in Body Art, an ethnographic survey of body decoration at the Museum of South Australia. Representations of traditional cultural insignia from Pacific nations such as Samoan tatua and Maori ta moto are juxtaposed with voyeuristic images of urban tattooing, piercing and scarification. While I appreciate the death of curatorial narrative, I found the thematic progress of the exhibition rather too open ended, relying on sensation (S&M, fetishism) rather than substantial analysis. Camp irony abounds in some of the contrasts, such as the comparison between tribal men wearing restrictive belts and Kylie Minogue sporting her version. In all, Body Art goes a long way in opening up debate surrounding the psycho-sexual pleasures in adornment and cultural initiation but I was troubled by its celebration of a particular stream of underground counterculture by making superficial comparisons with traditional images and material. I also wondered why cosmetic surgery was included, but not surgical scarring?

Ironically, in a small town like Adelaide, neither Piercing The Skin nor Body Art seemed to know of the other’s existence! Better communication spells more lateral audience crossover, which is always handy when you’re doing good contemporary theatre.

Play With Repeats, writer Martin Crimp, director Chris Drummond, lighting Mark Pennington, music Julian Ferraretto, design consultant Gaelle Mellis, Balcony Theatre.

Piercing The Skin, Junction Theatre Company and Leigh Warren Dancers, directed by Geoff Crowhurst and Leigh Warren; designers Kerru Reied and Dean Hills, music David Hirschfelder and Collage; The Space

Body Art, National Museum and the South Australian Museum, Museum of South Australia, July 15–September 30.

RealTime issue #39 Oct-Nov 2000 pg. 38

© Dickon Oxenburgh; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Stompin Youth, Primed

Stompin Youth’s latest performance embodies the energy of dancers in the process of becoming primed for life. Artistic director Jerril Rechter has situated Primed in the Inveresk Railyards Tool Annex—a large and echoing workshop constructed from galvanised iron. Daylight chinks through gashes in the walls.

Primed is a site-specific performance that requires the audience to move to 4 locations. This would be a manoeuvre of (t)error for any director lacking Rechter’s certainty. Stompin Youth effectively exploit the integrity of each space to perform a dynamically diverse, yet unified sequence of dance.

Site 1—Arcade. The beginning of Darrin Verhagen’s sound score evokes a Tibetan prayer bowl resonating pure sound from its rim. Two skateboarders mirror this effect by circling a huddle of dancers lying on the floor. Four women enter, each with a flashing strobe attached to their belt. Chelsea Billet demonstrates stylised movements which build to a frenetic pitch as the dancers respond to her theme. They grip, release and fall, alternating a kickbox movement with a Zen bow-pull action of the arms. A strobe is dropped and lies displaced, winking at a red ball clamped in mechanical arms that hover menacingly. The dancers acknowledge this threatening presence with alternating gestures of homage, longing and uncertainty. Sixteen dancers maintain the focus and patterns of connection as Jan Hector and David Murray’s lighting spills across dance to unrelenting dynamic and pulsing sound.

Site 2—Bedroom. Long strands of multi-coloured milk-crates dangle from the roof. Once released, the crates become seats for the audience. The area is in darkness and a slowed video sequence by Marcus Khan (from the original video Destination) establishes the elements of flirting, love and lust. Khans’ languid images highlight an evocative interplay of limbs and bodies while handmaidens unroll red and blue quilt covers onto randomly slanted beds. The actions of 4 entwined couples counterpoint dancers who sit or move alone. In a world saturated with commodity images of sex, this uncompromising sequence evokes the permutations of sexuality and corporeal codes. Stompin Youth dance the space of desire with authority and maturity.

Site 3—Scanner. A corner of the workshop is dramatically steeped with white light. Sun seeps through the corrugated walls. Five male dancers revel in their strength and potency, testing their physical limits in vigorous duo and trio combinations. The work of Adam Wheeler and Cheyne Mitchell (in his first performance with the company) is robust and skilful. These dancers self-launch from the walls with ballistic force. The operatic voice emerging from Verhagen’s score, and the tracking light grid accentuate the power of this performance. A feature of this site is the dancers’ use of the corrugated walls and framework to enhance the percussive and choreographic effects. The dancers demonstrate a subtle combination of physicality and vulnerability. They realise something other than strength is needed to survive the whispering static of their own uncertainties.

Site 4—House. This site is the most enigmatic and challenging for a school audience. An empty carriage gradually reveals faces looking out onto dark ground. The train arrives, dancers emerge then re-enter the carriage. Each compartment reveals an upstairs and downstairs level. Hector and Murray’s stunning lighting emphasises split panels that reflect and accentuate different body parts—hips, hands, heads and shoulders. When the lower level passengers exit there is an intriguing optical effect of surreal disembodiment.

Stompin Youth is a young company experienced in choreographic collaboration and working in multi-medial environments. Primed is a sophisticated production that successfully meets the demands of the workshop annex and the transitions across 4 sites. Launceston is fortunate to have a company that so effectively showcases the vitality and excitement of dance in a non-conventional theatre space.

Primed, Stompin Youth Dance Company in association with the Tasmanian Department of Education, artistic director/choreographer Jerril Rechter, choreographers/performers Cassie Anderson, Emma Anglesay, Sheona Anglesey, Claire Barker, Chelsea Billett, Rachelle Blakely, Mark Brazendale, Jo Briginshaw, Sally Anne Charles, Lilly Deeth, Elizabeth Elsby, Eve Flaherty, Sarah Hankey, Lauree Harris, Kylie Jackson, Tanya Lohrey, Kate MacGregor, Kathryn McKenzie, Cheyne Mitchell, Amalia Patourakis, Chris Philpot, Sandy Rapson, Ingrid Reynolds, Cory Spears, Lyndsay Spencer, Natasha Tabart, Nicola Watson, Adam Wheeler and Linda Voumard; composer Darrin Verhagen, designer Simon Terril, dramaturg Vanessa Pigrum, lighting Jen Hector & David Murray, video/documentary Marcus Khan; Inveresk Railyards Tool Annex, Launceston, August 31-September 2.

RealTime issue #39 Oct-Nov 2000 pg. 6

© Sue Moss; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

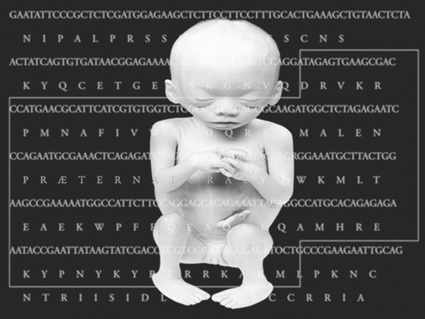

Michele Barker, Præternatural

I’m part of a large organising committee including people like Annemarie Jonson, and John Tonkin. I’m helping out with the exhibition components. I’ve recently finished by PhD which looks at artists using Artificial Life because essentially that’s the theme of this futureScreen.

The right man at the right time in the right place. How is the theme realised?

It’s been taken on in a broad way. Alife is a quite coherent little scientific discipline with its own conferences and papers and journals and there is quite a lot of art that draws directly on the techniques of that scientific culture. On the other hand, the idea of artificial life is much broader than that and embraces all kinds of re-engineerings of life including biotechnology and medical technologies; it also filters into artificial intelligence and robotics. All those things are broader than Alife as a discipline but all of them are involved in futureScreen 00.

How is it staged?

The core event is a forum that spans technoscience, creative practice and cultural thought. So in the last one, which was about avatars, we had technologists who were building software to make avatars and people who were building virtual worlds from the technology, IT and commercial industry point of view. We also had lots of artists who were doing the same sort of thing. Similarly with Alife, we’ve got people who are researchers in the field. We’ve done incredibly well and got Christopher Langton, the guy who basically founded Artificial Life. He’s coming to give a keynote, which is fantastic.

When did he make the discovery?

During the early 80s. Alife defines itself by distinguishing itself from Artificial Intelligence. It came about through a hunch that AI was basically going about things the wrong way by trying to start with intelligence as the object that needed simulating. The basic intuition of Alife is why don’t we start with something simpler and see if we can work out how living systems work. The key approach of Alife is to think that the intelligence will pop up out of the life once the life is put together in the right way.

Over the years we’ve seen life being generated and mutated on computer screens.

It’s an obsession but it’s also quite a well-established tradition in the electronic arts. This is quite a strong thread, which almost parallels the science. I think of it as a generative urge and an urge for automatism, if that’s the right word, for the automatic, for the thing that does its own thing. I guess you can trace it back to kinetic art and systems art in the 60s if not well before that. To me that’s what’s fascinating about this. Artists are taken with it because they’re interested in exactly those aims. So they take up these techniques from the scientific field and start tinkering with them…

It’s so different from the idea of the static, finished artwork.

On the other hand there are things I have problems with about it—things like organicist ideas about the wholeness of the work or the work being some sort of perfect functioning unit or ideas about the “living” work. That’s the whole modernist tradition which all of this stuff is really involved with, I think. But when it works well it sidesteps that.

In what way will it manifest itself in futureScreen?

All kinds of ways. We’ve got some beautiful robotic work. An American artist called Kenneth Rinaldo for many years has been building robotic systems. He calls them a “confluence” between technological and biological systems. They’re robotic arms but the structural material is grapevines with delicate little wire and pulley articulations. The work’s called Autopoiesis and consists of 14 of these arms; we’ve got 8 of them, each about 3 metres long. They hang from the ceiling, sense each other’s location and sort of flock around. They also sense the location of people walking around in the room and they twist and turn and sing to each other, using telephone tones.

Sounds like a major piece.

It’s huge. It’s come fresh from the Kiasma Museum in Helsinki who commissioned it. It’s a piece of straight Alife in the sense that it’s using all of the basic techniques from Artificial Life to do with putting lots of simple units together and watching them interact in order to make something more complex, something emergent happen.

These things are generative—is there a chance element?

With Ken’s work and a lot of the other work it’s a kind of involvement of the environment, the work is sensing itself and sensing changes within itself. It’s really the setting in place of a system that is richly interconnected both with itself and with its environment. So it’s reacting and that is, I suppose, where the impression of life-likeness or autonomy comes from, from the complexity and the patterned nature of those responses.

Autopoiesis is at the Australian Centre for Photography. Also at the ACP is Michele Barker’s new work Praeternatural which is a very luscious, interactive CD-ROM-based work about the engineering of a being, a build-your-baby scenario. There’s also an Australian group called Tissue Culture who make tiny artworks out of bits of living tissue—tiny postage stamp sized bits of scaffolding with actual living stuff growing on it. That should be interesting to see.

Then opening during October at Artspace are 4 other works. Two of my favourite Alife artists, Erwin Driessens and Maria Verstappen, are relatively unknown in the electronic arts world because they come out of the contemporary European gallery scene. We have 2 works of theirs. One is called IMA Traveller, which is a computer-driven video projection piece, very very simple. It looks like you’re diving into a field of multi-coloured clouds and the clouds advance towards you and keep differentiating and you keep diving in and in and in. It’s a kind of zoom that never stops. But it’s made by a little cellular structure. They call it “pixel consciousness”—each of these pixels looks around at its neighbours and then splits into a bunch of other pixels. So it’s like a microbial mat of pixels.

What’s it responding to?

Nothing apart from itself. It looks around in the picture plane. Each pixel looks at its neighbours. The work borrows an idea from Artificial Life called cellular automata, a kind of computational system involving cells which do things based on what their neighbours are doing. The classic is a work called The Game of Life by John Conway. This one is really great because it has cells but the cells actually split. Conventionally, they stay as static units, but these sort of split and push each other out. So it’s a much more dynamic structure. It gives a beautiful result. As a sensual thing, it’s gorgeous. I’m really excited about seeing that on a big projection screen. The other work of theirs, called Breed, uses similar cellular splitting process but in 3 dimensions. The artists are sending out some intricate little polyester resin computer manufactured forms. Their work is interesting because while it’s very beautiful, it involves a kind of blankness, a total removal of artistic volition from a process of morphogenesis.

So, once it’s going, it’s going.

Yes. It’s like the artists are asking how can we remove our aesthetic decision-making and just make varieties of stuff. One of the most complex works in the show is Life Space by a pair of European artists based in Japan, Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau. It’s an artificial ecosystem where the creatures live in a thicket of vegetation and you can interact with them on a video screen. Interestingly, the way that you generate more creatures is by typing text into the system. You can send it an e-mail, which it will interpret —this is the genetic code for a new organism and based on the characters in your e-mail it will generate some new creature. Then other people can log into the site and see what the creatures are doing. You can encourage them to get together and have babies or stop your favourite creature from being eaten by the others. Stuff like that. It’s a play garden.

Do you have to learn a code to do it?

No. All the interaction level is quite fluent, quite intuitive. Also in the exhibition there’s a listening station for a site I’m curating called Autonomous Audio, which is a collection of audio pieces by artists using Artificial Life and other complex generative systems. Everything from conventional Artificial Life techniques of cellular automata and simulated genetics through to more open-ended physical feedback systems and other complex forms. That’s at Artspace and we’re streaming audio on line as well as mpeg downloads. It includes some interesting Australian computer music—academia-based computer musicians in the art music mode—and then some people who are more experimental media hackers but often using similar processes and coming up with stuff that in some cases sounds quite similar to old school computer music. There’s a piece by Oren Ambarchi and Martin Ng who are local improv. merchants—a beautiful piece using feedback systems running through turntables.

Then there’s the forum event—another all star lineup. There’s Langton, as well as Tom Ray, another Alife pioneer who will be doing a remote presentation, and Cynthia Brezeal, who builds “sociable robots” with Rodney Brooks at MIT. We also have Steve Kurtz from the American group Critical Art Ensemble, who makes a strong political critique of biotechnology. There are some interesting AI people. There’s Claude Samut, who was involved in the Robo Soccer Tournament with the winning team of Sony AIBO dogs; Sony’s little artificial pets. There’s also some good local people like Stephen Jones and Jon McCormack, an artist who has been working in this area longer than most people. Oh, and also, we have Don Colgan from the Australian Museum who’s involved in the Thylacene project, hoping to clone or revive the Thylacene from preserved genetic material. That’ll be fascinating.

dLux media arts, futureScreen00, Symposium, Powerhouse Museum, October 27 – 29, Exhibitions: Artspace, October 5-29, ACP (Australian Centre for Photography), October 20 – November 20, (www.dlux.org.au/fs00).

RealTime issue #39 Oct-Nov 2000 pg. 32

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

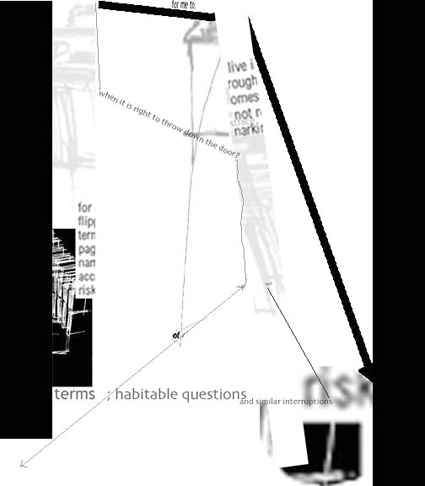

Acts of Language production, in the place of the page project Construction Phase 3

An Australian novelist reports on his UK residency to Incubation, an international conference on writing and the internet organised and hosted by trAce International Online Writing Community at Nottingham Trent University.

* * *

In this presentation I attempted to improvise a hypertext-like performance through a number of (also improvisatory) strategies. These were: 1. sitting among the audience facing forward and without making eye contact; 2. shifting restlessly from seat to seat (8 had been placed in an arc for an earlier panel) at the front of the auditorium; 3. reading to individual audience members and showing the place in the written text by following with my forefinger; 4. sitting on the knees of an audience member; 5. reading to individual audience members; 6. giving copies of my novels to audience members; 7. climbing over chairs stacked precariously at the rear of the auditorium; 8. crawling on hands and knees under the legs of rows of audience members, then springing into the air and shouting “Asparagus”; 9. teaching Israeli folkdancing (specifically, Havu Lanu Yayin Yayin—this involved the entire audience, and necessitated an interlude of about 4 minutes, after which I continued the talk somewhat out of breath); 10. wandering up and down the auditorium’s centre or side aisles; 11. striding along the centre aisle patting audience members on the shoulders in time with the words; 12. informing a baby how my own 2 year old had insisted I go straight to Teletubbies websites and how I’d often have to switch back and forth between my work-in-progress and these children’s sites if I wanted to get work done. These actions are indicated in parentheses where they occurred in the talk, as best as I can remember.

I was interviewed for the trAce Writer-in-Residency via videoconference (1). I sat in a room at the University of NSW and Sue Thomas and 2 other interviewers occupied a similar space at Nottingham Trent, although because of the camera framing, I could only see 2 of them at any time. During this interview, Thomas was quick to incorporate a definition of the word “flesh” widely circulating in this conference. Flesh is no longer a burden for our immortal souls to bear for a mere lifetime, but a guise which we may wear or discard at our discretion, alternating it with the virtual as a phase or layer or link in internet era identity.

I was flesh writer-in-residence at trAce from June to December 1999 (2). I shipped my meat to the UK by aeroplane, taking up space, eating aeroplane food from plastic aeroplane trays, leaving the plastic covers to become an international waste disposal problem, to become landfill in Singapore, Dubai and London where the plane touched down, sucked in fuel, emitted fumes and unloaded consumed and unconsumable international air traveller waste.

My friend McKenzie Wark (3), the writer and (I hope he’ll excuse me for saying this) polemicist for the postmodern, borrows the term “vector” to describe flows of information, especially in relation to the operation of international media. The term implies both direction and mass (4). Anyone taking an international flight can observe the contents of their aerodynamic cylinder, 300 or 400 brain-boxes loaded with prejudices and ambitions with regard to the proper modes for conducting trade, government, travel and conversation, preconceptions and hopes for aesthetics, relationships and money schemes, as the flight arcs over irrelevant places (10), totally aimed at destination.

(8) There has been a lot of reference at this conference to the rhizome as a model for internet story-telling. I don’t know if this theory holds water, but I’d like to suggest as an alternative, the sponge (3). The sponge is a collective of semi-autonomous cells, each of which has its own function yet contributes to the whole. It is possible to separate the cells by sieving. When brought near each other, they are then able to reconstitute the total organism.

I drove up the M1 from London to Nottingham, and I was in residence—or perhaps I should trace it back a little earlier—from the moment I saw the massive cement cooling towers of Nottingham’s coal-power generators (7). Does a narrative place begin with the sighting of its iconic representation, even if one has not yet discovered that the landmark is iconic?

The flesh residency could be mapped along the length of this room: (11) June, July, August, September, October, November, and December. But to do that, I would need to remodel it in the Caesarean manner: I came, I saw, I overcame a number of minor technical difficulties and showed various people and groups in the East Midlands ways in which they might find certain aspects of internet culture and/or content interesting, useful, engaging, engulfing whereas others preferred other modes of research or creative production.

In June, I was overwhelmed with junkmail (3).

Dear Sir:

Having had your name and e-mail address from the Internet, we avail ourselves of the opportunity to write to you and to see if we can extablid (sic) your name and E-mail address from the Internet, we avail ourselves of the opportunity to write to you and to see if we can extablish (sic) business relations with you. We are Haimen Sihai Plant Extracts Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China, specialising in astraglus extracts. We shall be glad to send you quotation and samples on receipt of your specific inquiry.

We await for your early reply with keen interest.

With best regards,

Yours faithfully,

Shirley ffield Sanford.

I was a relative newby, had built only 1 small and simple website, but had a longstanding interest in non-linear narrative, recognised by reviews such as this one of my first novel Tourism: “The back cover blurb calls it a novel, but you might as well call it a gazebo or a stirrup pump” (6).

If you’d asked me in June I would have said (5): I find the internet, in its unrestricted, ungated, chaotic, non-hierarchised, improper, uncatalogued, misspelt, garbage-filled, shit-strewn, amateurly built, poorly argued, jargon-ridden, linguistically overloaded, fanatical, self-important, trivial, pornographic, commercial, hit-driven, disorganised, memory-swallowing, time-stealing, left-branching, paranoid, unfocused, meandering, self-promoting, meta-generic, error-message-prone, window-popping, security-promising, satisfaction-guaranteeing, new-age-philosophising, loss-making, anything-goes, direction-finding, repetitious, unreliable, unbelievable, incredible, sex-life-saving, breast-expanding, money-throwing, pharmaceutical-flogging, comparison-shopping, bad-poetry-propounding, more-is-more-aestheticising, history-revising, spin-doctoring, repetitious, unreliable, neurotically generous and sometimes beautiful incarnations to be a useful resource for the understanding of otherwise difficult-to-imitate institutional languages, and their appropriation in my writing for various media.

I spent a good proportion of my residency travelling around the East Midlands (10)—the counties of Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Northamptonshire and Leicestershire, and the tiny breakaway enclave of Rutland—introducing internet possibilities to writing and other groups such as journalism students, recovering mental health patients, arts workers and librarians.

(9) One difference between online residency and flesh residency was that participants in the former were almost entirely self-selecting. They chose to participate in discussions on the webboard and for the most part chose to contribute to Christy Sheffield Sanford’s My Millennium (www.trace.ntu.ac.uk/writers/sanford/my_millennium/presents.html – expired) or Alan Sondheim’s loveandwar (www.trace.ntu.ac.uk/writers/sondheim – expired) or to my Speedfactory (www.trace.ntu.ac.uk/writers/cohen/speedfactory/speedfactory.htm> projects – expired) (10).

On that TV program-of-record, Sky News, it was reported the other night that although internet connection in Britain has doubled in the last Very Short Time (this story shows up on free-to-air every 6 weeks, every 3 weeks on Sky), some 15 million Britons have no intention of ever going on line and do not regard the internet as either relevant or necessary (5). I worked with many of these people.

While this produced some mutually frustrating interchanges, it also opened up surprising possibilities. One of the projects to which I had been most looking forward was the chance to work with retired and redundant coalminers. The East Midlands was a primordial site for the Industrial Era, the first resistance to it (by Luddites), and the major site of its end, hurried by the anti-union rabidity of the Thatcher government (3).

I was informed that a group of ex-miners wanted to write their history and stories online. Half way through the first session, a journalist rang to inquire how it was that an Australian novelist came to write a book about coalmining in Derbyshire (3). I was surprised by this project to say the least, but at this stage cannot entirely rule it out. The miners had been told I was conducting research for a book, and that it would be very useful for me if some would show up to assist with this (5). This meant that the most helpful miners, and some members of a writers’ group composed largely of ex-miners’ wives, chose to come along, but that none had any interest in the internet. So, in the manner of farce, I’d gone along to make their lives better and they’d shown up to improve mine.

We did manage to find material, 19th century coalmining poetry, coalmining and mining history discussion lists (3). More importantly, people brought out their archives, writing labours of love and 60 year-old catalogues of mining machinery. (Some of this is now online at www.trace.ntu.ac.uk/writers/cohen/front.htm – expired.)

Meantime in that refuge of calm, the internet, various people were teaching me more advanced skills. I’d been trying to make a MOO-based chatterbot say witty remarks, though it had come out more like Peter Handke’s theatre piece Insulting the Audience (3). Later, trAce member Pauline Masurel and I constructed duelling sestina bots (12). (They’re currently in the “trace” room at LinguaMOO www.lingua.utdallas.edu – [expired] and are named balagan and clamjamphrie.)

Christy generously suggested ways of improving my page-building skills, suggestions I abused to the degree that I became notorious for having built one of the ugliest pages in trAce (according to the Arts Council of England’s Dispatches newsletter). Alan invited me to contribute to loveandwar. Instead (using a very simple Markov Chaining program), I remixed an Act from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet with extracts from The CIA World Factbook to produce what may be the ultimate in paranoid and bureaucratic Italian Romance (10).

In November, with Terri-ann White’s assistance, I ran a superfast version of the collaborative e-mail writing exercise Speedfactory, a project devised in its long form by Wark and John Kinsella (5). In its original form, 1 partner e-mailed 300 words to a second, who had 48 hours to e-mail back. These exchanges seemed to sustain about 15 or 20 “rounds”. In the trAce version, participants fired 50 words at each other 20 minutes apart. (The Kinsella/Wark/White/Cohen version will be published by Fremantle Arts Centre Press, hopefully within the next year.)

It’s 7 months since the end of the residency, but I’m still involved with trAce (3), working with poet Mahendra Solanki, journalist Kaylois Henry and UK-based New Perspectives Theatre Company on another of Thomas’s wild and hopefully achievable ideas, the HOME project, which, like me, is investigating various forms of dislocation.

Incubation, international conference on writing and the internet, trAce International Online Writing Community, Nottingham Trent University, UK, July 10-12.

RealTime issue #39 Oct-Nov 2000 pg.

© Bernard Cohen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net