Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Love is a 4 letter Word

Teenybopper films, Bring It On aside, got a well-deserved hiding from Phillip Brophy in RealTime 41, but TV for not-quite-adults has never been better. Look at it. The Simpsons, Malcolm in the Middle, Daria, Love is a Four Letter Word, 24 Hrs versus the supposedly grown-up options of Temptation Island, Flat Chat, Millionaire Couples, Just Shoot Me!. OK, that’s a biased list (and there’s some crossover there) but perhaps it’s why those approaching their 30s claw onto their teens, revelling in scooters, streetwear at the office, I-wanna-be-a-filmmaker-writer-web-designer-dreams and moshing in Big Day Out sweatshops (or maybe it’s our inheritance from 50-something parents desperately hanging onto their 20s).

I weep when I think of a wasted youth watching The Brady Bunch every afternoon (I wrote that before realising it’s still on); The Wonder Years was a revelation! Now, look at Malcolm in the Middle: a teenage son undergoes S+M rituals at a military academy, a central character talks directly to camera and invites us into his skewed world, parents are so consumed by each other they forget about the kids, and revel in it. No moral to the story (really). No sitting in bed in demure nightgown and striped pyjamas communicating. Witty, shocking, out-there comedy on prime time Channel 9. A recent episode had an over-protected boy escape with Malcolm’s help into the night to play at Timezone, lose his wheelchair, get dragged along on cardboard, elevated into a shopping trolley, crash violently and eject, only to land on the concrete and scream “I can’t feel my legs!” The Simpsons has revolutionised the small screen (and my pop) world.

The ABC has been plugging away with teen drama for years. Heartbreak High was always miles ahead of Darren Starr’s receding-hairlined 90210, and now there’s Head Start, running smoothly after Top of the Pops—Ricky Martin is not made of cardboard!—and before the addictive chorus line of Popstars on Channel 7. Now there’s niche marketing. Top of the Pops proves that most acts in the Top 20 can’t sing or dance. Bring back Recovery! It seemed to hit on the right formula—Saturday morning, live performance (a rare outlet for Aussie bands to play on TV), deliberately chaotic delivery, a talented anti-host in Dylan—and then it disappeared to be replaced by repeats of Monkey and more Top 20; it’s almost like ABC programmers punish themselves for getting it right. But anyway, I’ve gone off track (you know, my generation’s poor attention span).

Head Start is, like Popstars, based on competition and market forces. Various youngsters are bankrolled to start a business. According to their mentor (who sits, like Charlie from Charlie’s Angels, behind a desk where he never seems to do anything) they are answerable to their sponsor (the bank) who has the power to suspend projects. They must learn to interact with their peers to succeed (hopefully Jonathan Shier watches this). The girls are picture perfect. The country boy wears an Akubra. The participants learn how to market their wares and bodies, bargain, make deals, and achieve the “potential of sponsorship and advertising on a global scale.” It’s the perfect show for the current political environment, teaching teens to be individuals while kowtowing at the altar of economic rationalism.

When it comes to drama, sometimes documentary can do it better than fiction. PS, I Love You, which screened recently on ABC, got into the head of 14 year old Mae, living away from home for a year in rural Victoria. It’s a revealing portrait of the intelligence, energy and conflicts of girls in their mid teens, with the added baggage of negotiating cross-cultural issues. As her Cambodian friend Pam says, “I’m sorta stuck between…not sure whether to follow my culture or whether to follow what I want to be and who I am.” The digital camera becomes the tool/weapon of daughter and mother (the director), as Mae and her friends are more comfortable talking to camera than their mothers: “If I tell her too much she’ll maybe hold it against me.” It’s a contradictory world with false allegiances and regular betrayals, where what holds families together/splits them apart is what remains unsaid. Fathers are noticeably absent and the film’s most memorable, uncomfortable scene comes when Mae’s father returns (she hasn’t seen him since he abandoned the family when she was 3) and he can’t even look at her, chatting up her younger brother and inviting him to sit beside him, taking on a stern authoritative role inappropriately, too soon (and too late). In a family counselling session, she asks him for a guarantee that he will send her a letter “in the next 2 years or something.” He won’t commit, even when she asks, “is there anything that you are sure about…that you can do?” Lisa Wang’s direction, interestingly, reveals the controlling hand of a protective mother. Her voiceovers often state what we can already gauge from the footage and seem intrusive, especially as we know she’s not (physically) present. In a scene where Mae lets her (considerable) guard down and talks about death, that indefinable fear that haunts us all, her mother’s prodding reveals that she no longer understands the complexity of what her daughter is trying to say. With panic in her voice, Mae says: “I don’t think people have enough time to do nothing in life.”

Love is a Four Letter Word is full of existential angst too and grows on you like fungus. Albee (Kate Beahan) and Angus (Peter Fenton) are today’s de Beauvoir and Sartre. If Jean-Paul was around, he’d own a pub and bash in pokies with his steel capped boots; and Simone would quit publishing because of its clash with her high ideals of being a Writer. And yes, they’ve come to an “arrangement” (they can have other lovers and be cool about it) which has always worked fine, as it always does, except that Angus’ dad’s wife is pregnant with his (yes, Angus’) baby and Albee doesn’t know. But would she care? It’s a rare expression that passes over her strangely masked face. Her sister Larissa (Leeanna Walsman) has all the spunk. LIAFLW has a cumulative impact. The concept/characters get more perverse, a new band in each episode—Preshrunk, Jackie Orszaczky, Machine Gun Fellatio—brings a varied mood (like in The Young Ones: who can forget Madness) and the writing and cinematography, after a ploddy start, spiral further into surrealism, camera swinging like a sinking ship. Angus gets most of the introspective focus, constructing alternate narratives, jump cuts thrashing him about. It’s interesting how Fenton plays against his own charisma in this role (and in Praise). As singer/musician (solo and in Crow), I’ve seen him devastate swirling crowds of panting girls but, on screen, he becomes almost sexless, a pawn in other characters’ games. It’s a good move. Paul Bannister (Paul Barry), the best-friend-third-wheel from hell says, “I did not lie. I told my own version of the truth which in a postmodern world is a valid statement of fact.” Hallelujah! Hopefully, the series’ off kilter dynamics, contrasting moods and playful style and pacing will get a second run.

24.00 Hrs, an initiative of Queensland’s Pacific Film and Television Commission, is currently screening as part of Eat Carpet. It’s an imaginative series of documentaries where inexperienced filmmakers head off with just a camera to meet a stranger, to capture 24 hours in their lives. Sly pairing makes the initially awkward relationship between filmmaker and subject as interesting as what’s filmed. Steven seems to want to escape the limitations of being behind the camera when he meets Colin, an Aboriginal rapper and artist in Cairns—cool NY hat shading his eyes—who says, “my name’s gone beyond Australia, I wish I could have gone with it.” Conflict between his white father and Aboriginal mother means he has poetic insight into an often painful inheritance. Rebecca introduces us to Hannabella (dwarfed by an art installation) reading Mexican poetry at Brisbane’s Metro Arts, an eccentric bowerbird in hat and beads and plaits who never stops moving or talking, but is trying for “less is more so I can really experience something.” Doug’s boss won’t let the camera behind the butchershop counter but “Nige” sneaks there anyway. Doug is a gorgeous, 20 year old “man’s man” who would have made it on Popstars. He sings Lean on Me to the customers buying snags, makes a mean Eggs Benedict, and pretty much seduces Nigel, constantly teasing the guy behind the camera who can’t answer back (“tables will turn when the editing takes place”, his girlfriend says revealingly). Bronwyn struggles at first with Yangdzom, a Buddhist nun who is also a legal secretary in a Brisbane high rise. She is intensely private, used to a life of (mainly) stillness, so Bronwyn ends up putting the camera down (to establish a relationship first) and, later, lingers lovingly on the details of ritual: putting on robes, praying and prostrating, building mandalas. Sam visits Mackay for the first time to check out Danyell who works at Red Rooster and (like Yangdzom) wants to be a mechanic. She’s uncomfortable in the limelight (“this is going to be the most boring 24 hours of your life”) until well oiled at a nightclub where she lets loose. As, apparently, does Sam who admits to the night being the best of his life, with “complete strangers.”

24.00 Hrs reveals a curious gender divide. The films made by women about women are intimate portraits, in close on faces, carefully framed, not afraid to question. Those by men about men hang back in wide shot, afraid of crossing that invisible line (we never get a good look at Colin’s face). It’s a bummer that 24.00 Hrs screens late on Saturday nights (and is not even listed in The Guide). It will be missed by almost everyone, relegated, like many aspects of youth culture, to the margins. Why not repeat it in prime time, SBS? And what about a second series where the roles are reversed, giving those filmed a chance to train their cameras on the filmmakers…it gives a whole new slant to Australian Story.

Malcolm in the Middle, Channel 9, Tuesdays, 7.30pm; Love is a Four Letter Word, ABC, Tuesdays, 9.30pm; The Big Picture documentary series, ABC, Thursdays, 9.30pm; 24.00 Hrs, Eat Carpet, Saturdays, 11pm; Head Start, ABC, Sundays, 6.10pm

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 15

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

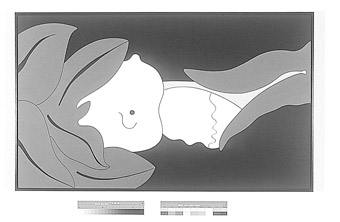

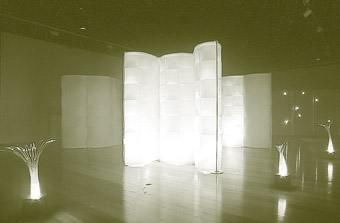

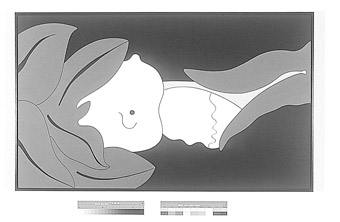

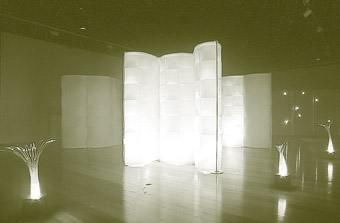

Madeleine Challender, detail of Light Forms 2001, mixed media

‘pling

Madeleine Challender, detail of Light Forms 2001, mixed media

Perspex, red fluid, abstract shapes floating in space, spinning in time, light silently cast on the wall, refractions intersecting. The eye perceives a cloud of dust, the head of a snake, in strange deep space, eternally shifting, chasing its own tail. Red contours, like flames, the first stirrings of the universe. Silence. The gentle plucking of Japanese koto begins.

Madeleine Challender is a universal light worker. Light Forms, her latest exhibition of 2 thematically-charged installations and photographs appeared recently at the Canberra Contemporary Art Space. While CCAS’s Furneaux Street Gallery in Manuka regularly hosts up-and-coming artists like Challender, it was Galerie Gauche in Paris that housed her first exhibition with light, Thought Strings.

Paris, she explains, was the turning point for her art, where the decision was made to explore the medium of light. While on exchange at L’ecole Superieur des Beaux Arts from the Canberra School of Art, Challender worked under the tutelage of French installation artist Annette Messager. While in Paris, Challender exhibited her last paintings in Vancouver and turned to her new direction with passion.

Light is all around us. The parallels Challender draws as she observes light have led her to pose questions about nature, the universe and the mind, while exploring theories of interconnectedness through the processes of systems. The first of the 2 installations in the exhibition, Heart Gravity, was designed to be a dynamic system. “I was trying to make rather than represent a system. To take these fundamental elements and incorporate them to create an active working system,” she says.

Like the transition from the fundamental building blocks of Heart Gravity to the more complicated title piece of the show, Light Forms, systems can start simply and grow. Light Forms takes up half the small gallery space standing about 6 feet high and 6 feet wide.

System Element 1: The Space

Five curved perspex pieces are suspended from the ceiling. The plastic was about the size of A3 paper until the heat gun was taken to it. Each was moulded over an anatomically shaped heart. These are the fragments of space in Heart Gravity.

System Element 2: The Form

The red ink inside the perspex forms uniquely shaped pools, variations on one consistent liquid form. Red is a dominant colour in Challender’s work. It represents the heart that inhabits the space.

System Element 3: Movement and Time

The perspex shapes spin on mirror ball motors. Movement involves time. In Light Forms this movement is contained in boxes made of opaque perspex, textured glass and paper.

System Element 4: The Light

The light activates the red liquid and perspex shapes, and creates refracted images on the walls. In Light Forms, fibre optics are used to reconstruct the bending of light through the universe, and produce the effect of starlight flares through the hazed surfaces of the cubes into which they lead.

System Element 5: Dimension

At this point Heart Gravity’s simplicity, in which the perspex pieces are merely arranged at different heights, diverges from the 3-dimensional complexity of Light Forms.

Light Forms is a structure of sixteen 30cm cubes. A single box sits at the lowest height from which a clump of fibre optics springs and leads up to the ceiling. Two boxes at the second-lowest point sprout 2 clumps of fibre optics. And so it goes…doubling up to 8 clumps protruding from the top-most boxes. The idea of exponential growth.

A large mirror is placed under the work creating an illusion of depth, as though there is yet another dimension beneath the floor. The most active movement and refractions are only revealed by looking into the mirror.

System Element 6: Perception

People’s perceptions of the work are necessary to make the system complete. “It’s activating thought for people, stimulating them to form ideas and images in their minds,” says Challender. She believes that art must be accessible and open enough to allow interpretation: “I think that is a key element to life—everyone has their own individual experience.”

Madeleine CHallender hopes to remount Light Forms in Sydney later this year.

Light Forms was made possible through a grant from Arts ACT; Canberra Contemporary Art Space, February 16-25

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 36

© Naomi Black; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Visy Theatre at the Powerhouse in Brisbane is the best venue I’ve been to for small gig concert music. It’s small, 200 people max, it’s not cramped, the aircon works. You can park the car easily, meet some friends, have a drink, look at the river, catch some sounds, interval, have a drink, chat with friends, look at the river, go back in, listen up, home in 20 minutes. I’ve been twice this year. Early Feb it was The Necks, a jazz trio (piano, bass, drums) very much out of the Sydney tradition and, later, Topology played the first of their 4 concerts at the Powerhouse this year.

The Necks are tasteful, skilful, no surprises, recommended by the friend I went with. They come on stage fairly serious with a bit of contemplative silence. Not the full reverent ju-ju, but we get the gist. This is serious music, one piece an hour long. Take care; are you good enough to listen? The set starts pretty slow. The bass player plays a 3-note figure for a while, then a while longer. The pianist also plays a simple figure that has somehow escaped my mind. A bit like a bar from an old Keith Jarrett piece (circa Köln Concert). And this guy can really play that bar. The time goes by, the seasons change, Iceland grows larger. Suddenly the bass player plays another note. He doesn’t do that again for a while. The drummer meanwhile is playing some tasteful repetitions of his own.

You might have picked up that I thought The Necks a little on the dull side. Sort of. In some ways the concert was good. The playing was excellent. The sound was clear. And the last few minutes where they really rocked was some of the best jazz I’ve heard. Loud. Aggressive. Chunky piano slabs, hard rubber bass, cymbals of death. Improv is great for exuberance and surprise. For subtle and considered, I’d just as soon the composer considered the subtlety for longer than one hour on the trot improvisation.

A week later, Topology play the well and truly considered. They’re a quintet out of the classical tradition. Violin, viola, double bass, sax, keyboard, and some multi-instrumental bits and pieces. Topology present a down home face to the audience. There’s some gentle ribbing between them; the frontman is personable without the toothpaste. The set is well selected with consistent themes and enough variety. An oldie by Messiaen, a Glass piece, Gavin Bryars, Lois Vierk, premiered works by Greenbaum and Gibson, and Vivs Bum Dance by John Rodgers. Topology has played this before. Reminds me a bit of the band Oregon in parts, but there are lots of other reasonably overt reminders. Not self-conscious cornball though, just the world we listen in. Rodgers is in the audience and takes a bow when his piece is finished. I bet that doesn’t happen too often for Australian composers, multiple performances and a bit of good cheer.

The performance of the 6th movement of Messian’s Quatour pour la fin du temps is a gem, solid playing and a great arrangement. The Greenbaum and Gibson were also good. I hope they don’t disappear after a single performance. Bryars’ Last Days is another good piece, though the playing was a little loose at times. The encore piece, Bernard Hoey’s reworking of a rock anthem by Queen, was in the Kronos meets Jimi style—a bit of throwaway fun. Leave ‘em smiling. (Maybe it was more than that. It’s a worry reviewing something on first listening, and I would be more than happy to hear most of this concert again.)

Not surprisingly, some pieces worked for me more than others. I don’t much like Glass’s A brief history of time—the tape of Stephen Hawking speaking is a bit forced (same old same old with Reich’s Different Trains). The live guitar tone in Vierk’s piece for 5 electric guitars was via a jack in the back of the keyboard, and not a dedicated guitar amp. A bit thin. The other 4 guitars came via a pre-record. Tough to do 5 guitars with only a single guitarist. (Must buy Seth Josel’s version—and there’s an advantage of hearing new pieces. I wasn’t totally happy about the Vierk performance so I went looking for another and found the guitarist Seth Josel. New CDs=new composers, and off go the search strings again.)

There are 3 more concerts by Topology at the Powerhouse this year. I’ll be there.

The Necks & Topology, Brisbane Powerhouse, February 10 and 17.

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 38

© Greg Hooper; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

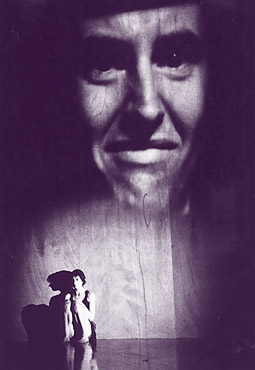

Tex Perkins

photo Kristyna Higgins

Tex Perkins

Laid back and veiled. Maybe that’s what all this talk of ‘alt country’ and ‘post rock’ means. The obscure championing of Smog, Will Oldham, Papa M, Cat Power…all distinct artists in their own right, yet all sharing a sense of something else happening behind the sounds they approach, a feeling that insinuation and shadows and mood are far from done with in modern music.

Of course some of the acts that fall into these warped genres can be very explicit and aggressive, usually post rockers like Mogwai and Yo La Tango rather than the alt country types who sound as if they are holed up on some drug fucked, go-slow verandah. But there’s a bridge there, over troubled waters, between these worlds, I’m sure of it. Maybe the Dirty Three could tell us more about that.

Whatever the nametags and marketing stereotypes, these artists mark a new retreat from the commercial machine and so-called ‘indie rock’, the relentless retail of grunge/punk rebellion and the intensification of music into niche-marketed packages. They’ve gone into hiding, dived into atmospheres and mystery, looking for soul again.

The thought of a hi-tech, low-fi millennium blues pops into my head, a kinda ‘roots of rootlessness’ music, propagated through the convergence of a mushrooming internet underground, home studio technology and artists happy to blow off their own willful creativity. An aural community is taking shape around them: people who can accept things a little slower or stranger, who want to get to know music instead of receiving it dead ahead.

You might identify this feeling as exploratory, introspective, submerged: adjectives that express the emotional backlash of a new (and sometimes old) underground to what’s going on up there on the surface of pop life and a newly minted ‘alternative’ mainstream.

Tex Perkins’ Dark Horses CD fits well into this quiet, secretive talk of music from the margins. I’m certainly not expecting a Sydney Festival Bar Crowd to respond to the low-paced songs live. Just picture the place: girls in tight skirts drinking blue cocktails; boys with designer beers hunting for sex; the DJ flogging this season’s love drug, Cuban music, that no one really gives a fuck about.

So when Perkins and his group open up with She Speaks A Different Language it’s as if the whole bar has sloooooowed down. Fine as this ballad is, a more stated, medievally aggressive song like Splendid Lie tames the restless second song in for a while.

The Dark Horses themselves are a super-talented group: Charlie Owen on keyboards, guitar and some bright banjo picking that blazes away then dies; Joel Silbersher, a post-rock god in his own right, maybe an even bigger star in the cottage industries of cyberspace, playing a bass almost as tall as he is along with a splash of psychedelic guitar; Murray Paterson, red hair and firm acoustic work that details the songs with Spanish emotion; Jim White on drums, with those percussive rolls and holding back touches of not-hitting-just-yet drama; and finally Perkins himself on acoustic guitar as well.

Maybe it’s the Neil Diamond in Perkins that makes him hold onto the acoustic guitar and make the most of his swivel seat for the evening. But he seems walled in by the instrument, a superfluous strummer in a band already overweight with 3 exceptionally capable lead/rhythm players. You just want to see him move more, twist those extravagant hands into a lyric and back out into space.

As a band of multi-instrumentalists, the musicians continue to unbalance each other just when you have what you want from each of them. To see Charlie Owen strap on an electric guitar is a moment of rapturous yet short-lived kinetic excitement, while Joel Silbersher’s guitar work is so fine and shaded and trippy and…gone.

Strung together in a set, there’s also a feeling that the mood is way too blue, and that Perkins really should listen to the best bits of Hot August Night, or at least a little more James Brown and Captain Beefheart than he has lately. And yet a moody number like Ice in the Sun repeats and broadens so much of what has come before taking you to another place. It’s slow ecstasy, and it makes my complaints seem churlish, my gripes minor on a very fine night of music.

With demands to “bring me champagne”, Perkins camps it up, Frank Thring style, enjoying himself and amusing the crowd. I used to hate that about him in ages past, how he couldn’t commit to an emotion without mocking it; but now it seems more like a nervousness or shyness as he slides out from a song into the world again.

Tonight’s set would suit a smoky, intimate pub, maybe even a theatre better. Not a weekend meat market dazzled by the glitter of the disco ball. But to Perkins and the Dark Horses tribute, the audience here make an impassioned demand for an encore. By which time the singer and band have hit a note of raw, forward movement, coming out into us rather than making us draw into them. It’s a belated dynamic too often lacking in this moody, weary array of songs tonight.

Maybe all that is missing are 2 or 3 tunes which bring a bit of light and speed to Perkins’ songwriting palate. Or a few more of those instrumental touches, like Owen on banjo or Silbersher with his funky wah wah ripples from outer space. A few more bright notes to colour his backwoods/inner city morality tales and send us off into the night knocked out, rather than just pleased and half loaded.

Tex Perkins and the Dark Horses, Sydney Festival Bar, January 1. Dark Horses CD, Grudge Records/Universal Music. An edited version of this review appeared in Drum Media, Feb 20, 2001

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 38

© Mark Mordue; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

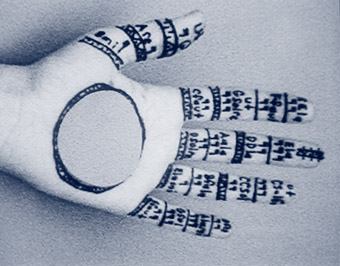

This is called ‘grace’, it only happens for a few minutes at a time.

A swallow is a bird, a harbinger of summer. “The sky is full of swallows, the sound of wings.” Swallow is also a term for an opening or cavity in a limestone formation.

Linda Marie Walker is an accomplished poet critic, novelist, a visual artist and a lecturer in interior design. Mike Ladd is a writer, sound artist and producer. They collaborated in making Lessons of the Swallows for radio.

Listening to Lessons of the Swallows is like looking at distant figures in a landscape, while hearing their voices next to your ear, and then realising that one of the figures is yourself.

The work was inspired by Walker’s sighting of swallows in Valencia, on holiday in Spain. Her impressions are like memories that last beyond the trip. The form is minimal, impressionistic, a “melancholy lightness.” It is about the impossibility of communicating an idea or who you are, and a lingering sense of incompleteness. At every moment you’re the product of thought and feeling and environment.

Swallows are symbols. The birds’ agility stands for human thought and mutable feeling, their social habits for desired human interaction. All speech is metaphor—it represents indirectly, unlike light entering the eye or sound entering the ear.

Lessons of the Swallows is adapted from Walker’s larger work The Last Child, written for theatre or radio production. The whole work includes a novella and visual imagery intended as a musical score. Ladd interspersed Walker’s script with her minidisc recordings made in Valencia, his recordings of the text being read, and musical and other fragments. Included are snippets of conversation between the artists about swallows and their mythology.

Ladd’s production has an ethereal, haunting intimacy. The restrained emotion in the readers’ voices, the close microphoning and measured delivery, emphasise rather than conceal the enormous affective power of the script. The avian swallow—here fleetingly, now gone—triggers the sense of loss and loneliness and the search for meaning.

There are street noises, distant voices, gulping sounds and the gasp of held breath, a nib scraping on paper, water flowing in a cave, and the swallows’ twittering song. Fragments of Jordi Savall’s viola da gamba thread through, either in the background or foreground. The shifting between male and female readers, and to other sounds, simulates the shifting of the mind between thinking and listening, between subjective and objective. The female voice carries the emotional weight, the male voice conveys facts.

The swallow’s mystery is a metaphor for the mysteries of life. The fables of the swallows are romantic expressions of human drama. Swallows are survivors. The geological swallow represents the descent into the abyss. To swallow and be swallowed.

This is a melancholy soliloquy. Walker and Ladd muse on the question: “what would you say to the last child?”, the impossibility of telling someone what they need to know. Their soundscape is evocative, powerful and intensely beautiful.

Lessons of the Swallows, Linda Marie Walker & Mike Ladd, The Listening Room, ABC Classic FM, February 19

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 40

© Chris Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

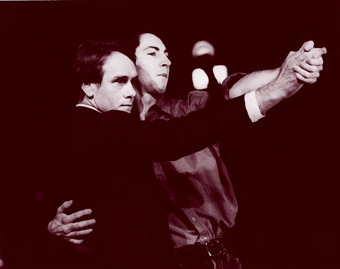

John Britton & Hilary Elliott, Time and Tide

Asimov says that the most exciting phrase to hear in science is not “Eureka!” (I found it!) but “That’s funny…” Perhaps it is also the way with creativity where exploration, experimentation and mistakes evolve into new forms of expression. Funny things can happen in the spaces left by departures from convention. La Mama’s season of Explorations offers an umbrella for the presentation of works which are allowed such departures.

Synchronised Drowning was first presented at the 1999 Festival of Contemporary Arts in Canberra. This incarnation is a polished piece, tightly directed by Emma Newman with humour and whimsy in a space evocative of swimming pools, with change room cubicles, that peculiar light on pool water and starting blocks. The fears and delights of swimming are explored—fear of the water and the people in it, fear of going under, the pleasure of endorphins and the etiquette of the public pool. Instead of narrative, the work shifts through a series of people and their stories of interactions at the pool, children caught in a rip, sinking in a crowded motel pool. There is a touch of the all-Aussie Olympics, a race beautifully recreated with media commentary built into the dash for gold. Some of the physical work captures the liquidity of water in the human body—a breaking wave of arms and hands, a body floating. Elsewhere, the repeated use of counting and the human breath as a focus—holding breath or breathing to a rhythm—gives the work a meditative quality. Although the performers hint at intensity—“Water is so emotional”—this piece is generally slick and easy. Near the end, a long hug, people washing and getting wet, is less comfortable but hinted at the possibilities of departing further from convention.

Time and Tide (John Britton and Hilary Elliott) tells a Seachange story of Paul and Judy, leaving the familiar world of city work to pursue a dream. They move to an island to broadcast from a tin-shack radio station (Radio Atlantis) but never know if anyone is listening. Nobody phones. Their dream is gradually eroded by the rising tide, of isolation and (perhaps) the death of their child. There are ‘time warps’ in the plot where things may or may not have happened. Increasingly, Judy’s broadcasts are personal calls for contact and connection to the world. Paul maintains his desire to change the world, desperate to be noticed. Throughout this piece, dialogue routinely gives way to a form of movement as emotional expression. This physicalisation of subtext is intense, athletic and disciplined but not often surprising. It tends to happen between text, in lumps rather than blending with it. John Fenelon’s original live music, a significant part of the performance, is screened from the audience.

Clean As You Go is a wild, exciting piece which messes with everything. The audience are given protective gowns or gloves upon entry into a space dirtied with broken glass and soil. A sign invites us to sit anywhere or move around as the cleaning begins. Good humour is established between a slightly uncomfortable audience and performers who offer water, flowers to smell, newspaper to sit on. Performers turn lights—not ‘lighting’—on and off as required. Justin Leonard’s compelling and dreamlike text pieces are presented in darkness. The performance is interrupted by the traditional La Mama raffle, 20 minutes in. Clean As You Go is loosely scripted, partly improvised, allowing direct contact with the audience. These young performers had clear intentions and were never lost in this mess of their own making. Music/sound/noise, provided by Adam Simmons’ saxophone, works in with the improvisation. The musician is introduced into the space and has to speak about cleaning as well. His awkwardness in speaking again challenges convention: dancers don’t sing, actors can’t dance. His words turn easily back into sounds, a music that drives the performance towards a frenzied cleaning in which the audience are respectfully but forcefully swept out the door. The sounds of scrubbing, banging, swishing water and feverish saxophone continue from behind the closed door.

Why is there a sense in many of these (and other) works that exploration somehow veers towards themes of the personal and domestic, body-based or quirky? What might happen if such work attempted social or political themes? Perhaps a confusion stemming from (misunderstood) postmodern influences is that a departure from dominant or familiar forms, especially rationality and logic, leaves no politics in a broader sense, no way of speaking beyond the personal.

The ongoing significance of La Mama in Melbourne is that it offers a space, an infrastructure and finances which allow risk. This busy season of Explorations reflects audience interest in and support for such work.

A Season of Explorations, La Mama, Melbourne, Feb 21 – March 25

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 26

© Mary-Ann Robinson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

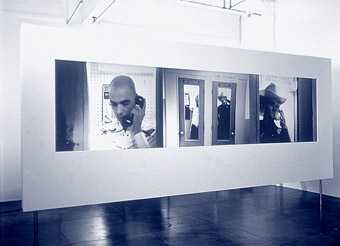

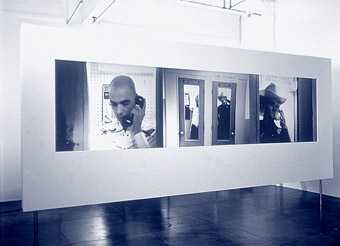

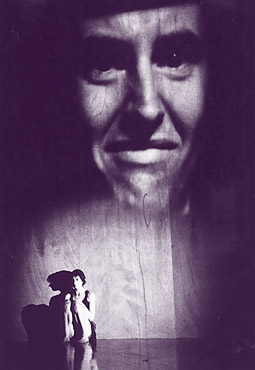

Isaac Julien, The Long Road to Mazatlàn

It seems that barely a week goes by without an attack on Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art. In late February it was Premier Bob Carr’s turn. His complaints about the museum’s international standing and poor quality of its collection and exhibitions drew an instant, wounded response from its outspoken director Liz Ann Macgregor. She need have done no more than point Carr towards the MCA’s current exhibition The Film Art of Isaac Julien.

This display of film, video-installations, photographs and prints, with its suggestions for new narrative possibilities and ambiguous imagery, bestowed mental traces that uncannily haunted me for days, compelling me to revisit the (free) exhibition. Ghostly memories aren’t easily tracked down, so I had to go yet again. Each time the startling yet dreamlike, strong yet gentle, carnival of Julien’s film art told me something new.

Britain’s pre-eminent Black filmmaker, Julien’s prescient feature Young Soul Rebels (1991) and feature documentary Looking for Langston (1989) anticipated art movements. Young Soul Rebels surely positioned him as one of the provocative band of so-called ‘Young British Artists’, and yet he’s never been included in this group. Langston, with its retrieval of the Harlem poet’s homosexuality and stylistic treatment of history, heralds the homo pomo of New Queer Cinema at least 3 years before it was invented.

Julien is difficult to label perhaps because labelling is, in part, what his art explores. He burrs the boundaries between cinema, painting, video, photography and performance, and rejects stereotypes in a process of metamorphosis by which they re-emerge as icons. He moves confidently between past and present, inviting us to feel repair rather than loss; he achieves this most memorably by casting himself in Langston as the dead poet in his coffin.

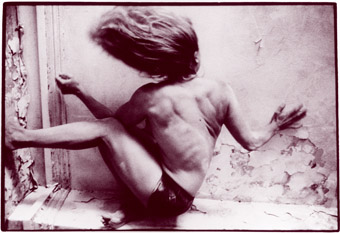

This beautifully photographed documentary, which pushes to the limits the definition of the genre, is shown in full on a large screen at the start of the exhibition, setting the tone and touching the right auratic nerve with which to view Julien’s more recent video installation work. His film trilogy, The Attendant (1993), Trussed (1996) and Three (The Conservator’s Dream) (1996-1999), here transferred to DVD, all display extraordinary, powerful images drawn from a sincere engagement with post-colonial, gender, queer and other political and social discourses. The work is assuredly intellectual and, at the same time, provides easily recognizable images that hover between the outright provocative and, without a hint of false sentimentality, the aesthetically romantic.

Giving a lecture to launch the exhibition, Julien expressed admiration for the way in which the MCA had designed the space to display his work. And small wonder. Placed alongside his photos and prints, his videos glow on screens small and large, single and composite, without any sense of competing with each other. The open-endedness of his video installations, as they play on loops, provides a mood of repetition and compulsion that affects, entirely pleasurably, how we view the still images. They, in turn, allow us to see his moving images as a series of stills while the narratives move backwards and forwards from scene to scene, and between screens.

It is impossible to resist a sense of physical interaction with Julien’s work. Feelings of erotic pleasure and loss in Trussed, for example, are enhanced by its projection on 2 screens showing identical, but flipped, images that are set in a corner at right angles. This offers ambivalent resonances of a butterfly struggling to free itself from a Rorschach test. The stunning 3-screen DVD installation The Long Road to Matazatlan delivers frissons of recognition as the fragmented images of a story of unrequited love between 2 cowboys appear stuck in a bizarre salad of Andy Warhol, Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, road movie and western.

Julien explained his interest in exploring the physical relationship between audiences and film by suggesting that he aimed to “bring back some of the early experience of making films. It’s more like early cinema, when spectators came and went at their own leisure, that open-endedness you don’t find when in a typical single-screen viewing situation. Repetition produces another way of viewing you wouldn’t otherwise get.”

Given its current troubles, it was a bold decision of the MCA to show Julien’s film art, since one of his recurring images is that of the museum as a repressive bastion of white authority. Can it be read as an indication of the MCA’s willingness to reflect upon its own role in helping us (re)define our relationship with screen culture? If so, things look good for the cinematheque which, many of us devoutly hope, the MCA will deliver in the not so distant future.

The Film Art of Isaac Julien, curator Amada Cruz, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, until April 22; Out Takes, a presentation by Isaac Julien, Mardi Gras Film Festival 2001: A Queer Odyssey, Palace Academy Twin, February 15

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 14

© Jane Mills; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

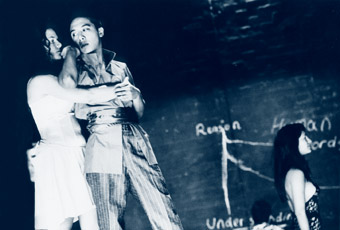

Lisa O’Neill, Leah Shelton, Liquid Gold, Brisbane Powerhouse

photo Sonja de Sterke

Lisa O’Neill, Leah Shelton, Liquid Gold, Brisbane Powerhouse

Liquid Gold took place simultaneously in Brisbane/Australia, Sheffield/England, and live on the internet. By inviting the body to dance with incorporeal tools, transmute collective extended the landscape of interaction to new technologies of pleasure, emotion, and passion “within places of eccentricity and madness” (as introduced in prior works, Transit Lounge 1&2; see RT 32 p29). Lisa O’Neill, as adventurer and strong woman ‘Ling Change’, was filmed live on video as she travelled through the Brisbane Powerhouse (an industrial site converted into an arts complex). Avoiding a hierarchy between actual and virtual objects, or privileging computer over physical body, this performance examined questions of how ‘we’ conceptualise experience, examine self and others, generate and perceive beauty.

The word is cyberdelic: follow the yellow brick road to the yellow submarine, observe the antics on Gilligan’s Island through the Captain’s ‘looking glass’ (kaleidoscopic, says Alice). Editing the work from segmented perceptions (attention divided between 3 screens and the live performance), am ‘I’, as audience receptor/inheritor of a white pop art aesthetic—simultaneously being re-edited, rewritten as an intermezzo—in this country? O’Neill’s performative ‘look’ for Ling is pinched, hard-bitten, farouche. It comes to me that as an audience I am mirroring Ling’s predicament, irreconciled.

Liquid Gold, Brisbane Powerhouse

photo Sonja de Sterke

Liquid Gold, Brisbane Powerhouse

Ling is seen ‘in later life’ amid “strange new worlds where a number of chance encounters with objects from her past revive both nasty and particularly irrational ghosts.” Ling should know better, but old habits re-emerge as she is shadowed once again by spectres of material and fluid desire in the rotund shape of the Fiscalite who tries again and again to tempt her with ‘liquid gold’—bottled up in cans of Core. This Ubu-like nomenclature summons up both the seductions of material wealth and sinister connotations of the waste products of nuclear energy. Liquid Gold is ‘actually’ waste product honey contained within a brightly coloured can of ‘drink’ (coke/core), and it is said that solid ‘fools’ gold can be distilled from the lumpy bits at the bottom. Is Ling’s ‘straining’ for meaning a fool’s errand? Ling does indeed “fail again” (Beckett). But does she ‘fail again better’?

Ling’s emancipation is conceived through the self-realisation of others, in a dialectic between individual and collective. The rhizomic pattern of shattered glass between worlds refracts a collective “Impossibly Beautiful Strawberry Cloudlands” as an action of “the people, united.” This fulfills conditions for Guattari’s proposal for an “ecosophy”, an “ecology of the virtual”, having as its goal “not only preserving endangered species of cultural life, but also of engendering new conditions for creation and for the development of unheard-of, unimaginable formations of subjectivity.” Liquid Gold restores the most often suppressed aspect of avant-garde activity, namely self conscious ‘collective’ identity.

This was an important breakthrough work for transmute and for the future of collective new works.

Liquid Gold, transmute collective, instigator, artistic director & digital video production Keith Armstrong, choreographer & performer Lisa O’Neill, performer Leah Shelton, musician Guy Webster, interface designer Gavin Sade, director of photography David Granato, writer Hugh Watson, designer Deni Stoner, network specialist Gavin Winter, Media Directors Site Gallery, Sheffield, Kelli Dipple and Matt; Brisbane Powerhouse, Site Gallery (Sheffield England) & live online, liqdgold, March 9

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 27

© Douglas Leonard; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Tony Leung & Maggie Cheung, In the Mood for Love

Tony Leung Chiu Wai is one of the most sought after actors in Asia, having made by his estimate 60 films, among them John Woo’s classics Bullet In The Head and Hardboiled, Hou Hsiao Hsien’s City Of Sadness and Flowers Of Shanghai and Tran Anh Hung’s Cyclo. In July he will begin shooting alongside Maggie Cheung and Zhang Ziyi (of Crouching Tiger fame) in Zhang Yimou’s new film and foray into the Chinese swordplay genre. He is on his first ever visit to Sydney and Melbourne to promote his new film In The Mood For Love, in which he plays an understated role opposite Maggie Cheung as they discover that their mutual spouses are having an affair. At a public appearance in Sydney’s Chinatown he was mobbed by enthusiastic fans. He has arrived in Australia without entourage or interpreter, and has a gentle and unassuming manner.

Wong Kar Wai has said that the time in which In The Mood For Love is set holds a lot of memories for him. What memories does it hold for you?

I was born in Hong Kong in 1962 so I still have some memories of that time. The situation was the same for me (the shared apartment of In The Mood For Love). We needed to share everything with others, I mean the apartment and our privacy too. So I was shocked on the first day I went on the set. It was almost the same as when I was a kid. I think the relationship between people, between neighbours was very close at that time. People seem to be more isolated now.

Tell me about how you got into acting?

It was by coincidence. I wasn’t satisfied with what I was doing at the time…I was a salesman of home appliances and I couldn’t see my future even if I worked hard. Suddenly one day I saw something on TV, they were looking for new talents, so I got into the training class and I found that it was very interesting. Somehow I found a way to express myself in front of others without being shy. Mainly because of my background I’m very good at hiding my emotions and I keep everything inside. So after I get into training class I find a way to express myself, I can cry, I can scream, I can do everything. I enjoy the process and I love acting because it’s a kind of therapy for myself, a way in which I can express my own emotions. But I don’t do it for fame or money, so I don’t really care about it; fame means nothing to me.

You’re happy about winning best actor award at Cannes for your role in In the Mood For Love?

Yes. I was also nominated in 1997 for Happy Together…(I was at Cannes and) at the last moment they asked if I was still there so everybody thought I’d get the prize. There were only 2 left in the final, that is me and Sean Penn, but finally I lost it. I was quite upset at the time. We don’t do movies for any prize, but once you know that you have a chance you want it too. So I thought, it doesn’t really matter I’ll come back again. So I went 3 times in 4 years and the last time I got it, so I think maybe last year was lucky.

Tony Leung & Maggie Cheung, In the Mood for Love

With In the Mood For Love, there are some publicity shots with Maggie Cheung which suggest it might have been a very different film. Were you surprised when you saw the final cut?

Of course, every time I was surprised, every time he (Wong Kar Wai) will surprise me. No-one knows what the story is about before the premiere, so every time when I see the movie I feel very frustrated. I was always looking for the missing parts: “Where is the love scene? Where is the scene I have with Maggie?”

You’ve worked with Wong Kar Wai through his directing career. What’s he like to work with?

He is very good at telling stories and he is very talented, very casual, very cool and always wears sunglasses. I don’t know what’s going on behind those sunglasses. He is the first director who can get rid of my Method acting because the way he makes movies without a script; everytime it’s like making an adventurous journey, you know we don’t know anything, what will happen next, so it’s quite challenging. It’s another way of making movies especially for an experienced actor who has a lot of knowledge about acting and some stereotyped expression. So working with him is something different.

What’s the hardest thing that he’s made you do?

I think the hardest thing is making Happy Together. At first when he approached me he asked me to play a gay role in the movie and I said, “I don’t think I can do that”, and ends up he gave me a fake script and flew me to Buenos Aires. After I settled there for one and a half months he said “I think (if) you play a gay guy it would be more interesting.” I said, “What?” But what can I do, everybody was there and everything was ready (pause) and I find out that I’m playing a gay guy. But I finally did it.

You’ve also worked with another of Hong Kong’s greatest directors, John Woo.

When I was working with him on Hardboiled I said, “We shouldn’t do this scene like this, I can’t cry in front of others in this scene.” And he said, “No, I think we should do it.” I said “Okay.” He’s very hard to compromise, he’s very stubborn, but he’s very nice.

Have you been offered any roles that might tempt you to Hollywood?

I have received a lot of offers in the past few years but I think the characters for Asians are very restricted as you can see—gangster or martial arts roles. Actually I never think of establishing my career in the States but I don’t mind if there’s the right character…If the project is interesting and the people are interesting, it doesn’t really matter where you shoot that movie.

You’ve never wanted to leave Hong Kong?

I love Hong Kong. I don’t have a reason to leave. No matter what happened to my place I won’t leave.

In the Mood for Love, director Wong Kar Wai, Dendy Cinemas, screening nationally; see page 14 for Simon Enticknap’s review.

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 13

© Juanita Kwok; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

As postmodern theory has asserted, performance is everywhere you look. But you have to know how to look. It helps if you’ve got a videocamera to note the finer details, or see things that real time viewing would never reveal. Fox has released slomo video shots of rugby league player John Hopoate violently goosing (or “date fingering” as coined by HG Nelson) the opposition in order to “immobilise them”, as one player put it. Viewers are aghast. Parents kick the TV power plug out of the socket or shield the eyes of the innocent. Grown men throw up over TV dinners. Team officials pretend shock. Players line up to come out—“he did it to me…it’s not uncommon…it’s just part of the game…” Well, well. No wonder men and women alike are turning away from league and taking up rugby union in droves. Doubtless the video footage will become a collectors’ item, aided by the media’s insistence on showing the footage over and over like the crash of the Hindenberg. Whatever, Hopoate has given new meaning to that old expression “bum sniffers” as applied to rugby league players ( The Dinkum Dictionary, 1991). What a creative nation.

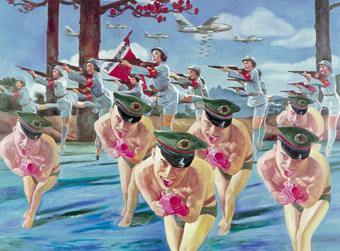

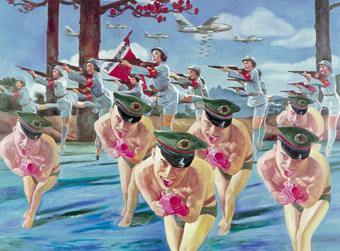

In RealTime 42 cultural matters are only a little more refined as Linda Jaivin and Trevor Hay look into post-Cultural Revolution art and literature—the paintings of Sydney-based Guo Jian and the novels of Anchee Min, who lives in the USA. Exorcising the Cultural Revolution is not only therapeutic, but it can also be commercially satisfying—witness the trade in Cultural Revolution kitsch in China and Singapore, including DVDs of Madam Mao’s model operas and ballets which are central to the images and lives presented by Guo Jian and Anchee Min.

So that RealTime can become more and more a part of your life, take a look at our website between editions. You’ll find breaking stories and selected articles published ahead of the next print edition. We’ve also installed a good search engine, which not only allows you to find articles and artists appearing in RealTime, but also is great for web-surfing in general. Our website has been incredibly busy in recent weeks, prompted partly by interest in the response to the Richard Wherrett speech (See RT#41, page 23) and the Benedict Andrews reply (this edition, page 23) to Louis Nowra that we published online in March.

After 7 years of publishing RealTime we’ve finally decided to run a regular letters page (RTpost, page 10) and a news & commentary page (RTtalk, p11). These are modest responses to the vast amount of talk that goes on around the arts and the importance we place on dialogue with our readers.

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 3

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Pre-Paradise, PACT Youth Theatre

photo Heidrun Löhr

Pre-Paradise, PACT Youth Theatre

March 5, 2001

Dear Editors

In response to Sarah Miller’s article “The Vision Thing” (RealTime 41, page 11) there are just 3 points I’d like to make in relation to her comments on the Australia Council.

My first point is about the Australia Council and “lobbying.” The Council is an arm of Government, being a statutory authority. A simple survey of funding issues at the Federal level over the past 5 years will show quite clearly that Government agencies lobbying Government is the least effective way to generate more funds. How does the Agricultural industry get more funding? Through the lobbying of the Farmers’ Federation. How did the scientists get more money? Through the lobbying of the business community. How has cessation of old growth logging come about in WA? Through lobbying by the green movement and its allies in Perth. And as for petrol prices, thanks go to the community at large!

None of this was achieved through lobbying efforts by a government agency. What the Council needs to do is to complement the lobbying efforts of others by reinforcing them through advocacy to government. Contrary to the implication of Sarah’s comments, we have not been sitting on our hands in this regard. Our role in achieving positive outcomes with the Ralph Legislation, the Moral Rights Legislation, and the Nugent Inquiry is well known to those who worked with us on these projects. But we don’t do it through the press or the other avenues that lobby groups will use.

Secondly, we have looked at how the increased funds were achieved for the major performing arts companies. This was not idle lobbying but an in-depth study of how that part of the sector was faring. The second and third tier companies, and the visual arts organisations, are now the centre of attention, and the Council’s planning process aims to fill out the picture in terms of the major issues for the field. Without such a picture there is nothing to present to government which is any more telling than the competing bids from the welfare, environmental, farming, and education sectors. Without “an expensive waste of time”, as Sarah puts it, we can’t even get to first base in marshalling our arguments.

Thirdly, Sarah accuses the Council of “hubris” in assuming responsibility for determining the future of arts practice. Please read the document, Sarah: it expressly says that this project is not about doing that, but is, instead, about enabling the Council to provide the type of support for the arts sector that the sector deems is most appropriate. You will notice, if you read on, that the leadership issue actually came up in one of the vision days and is not something that the Council itself put forward. I personally have big problems with the notion of a Government agency playing a leadership role—all sounds too totalitarian to me. But let’s see what the rest of the field thinks. After all, this is what the project is all about.

Margaret Seares

Chair, Australia Council

March 21, 2001

Dear Editors

In response to Dr Margaret Seares’ letter, I would like to note the following:

Firstly, I think that a closer reading of what I wrote would indicate that my response to the ‘minutes’ of the New Media Arts Vision Day were rather more ‘wary’ or ‘conditional’ than definitive. In my relatively brief, general remarks regarding the Australia Council, I was careful to note that “if there’s no money to back new ideas and initiatives…then all that vision and planning will become nothing more than an expensive waste of time.” For me and many of my peers, that is the unfortunate, everyday reality.

Secondly, I certainly don’t expect the Australia Council to be fully responsible for advocacy and lobbying. I made a distinction and suggested “a more effective role”, a “complementary” role if you like. Nor do I think the Australia Council has been sitting on its hands although, at times, it’s easy to get the impression that Council sees much of the arts community as the ‘opposition’ rather than as equal participants, perhaps a consequence of the funder/fundee relationship. I feel I must also note the enormous effort put in by students, individual artists, companies and organisations (NAVA in particular) across Australia to achieve more positive outcomes regarding the Ralph Legislation and Moral Rights Legislation and I’d be very sure that in terms of the Nugent Report, the MOF organisations lobbied extensively on their own behalf. I do see the Promoting the Value of the Arts (PVA) project and Vision Days as examples of ‘initiative’ and ‘leadership’, however I also reserve my right of comment.

In writing “The Vision Thing” I did, in fact, talk to a number of Vision Day participants, and I still feel it was important to note some of their concerns. I think I made it quite clear that a definitive response would be premature at this stage. Nevertheless, I strongly believe in the importance of discussion, debate, disagreement, dissent, scepticism, celebration, irony and even the odd bad joke. Only then can some of the interesting and important stuff emerge.

I appreciate Dr Seares’ participation in what I’m sure will be, and should be, ongoing issues for discussion and debate.

Sarah Miller

March 12, 2001

Dear Keith,

Thanks for the profiles of theatre and performance in Sydney in the last 2 issues of RealTime. It’s been a pleasure to read considered, informed and serious responses to work being done in a variety of companies and contexts. Can we please have regular, extended features on work being done in other States and Territories too?

I was fortunate to have the chance to work with Caitlin Newton-Broad and her team of young performers on their production of Pre-Paradise (RT#41). Fassbinder’s play, Pre-Paradise Sorry Now, was in part a response to the Living Theater’s controversial 1968 work, Paradise Now (which was “intended to inaugurate a non-violent anarchist revolution by freeing the individual”, The Oxford Companion to the Theatre) and Pre-Paradise Sorry Now was the original inspiration for the PACT piece.

As the research and development progressed, though, we found ourselves more drawn to Fassbinder’s play Blood on a Cat’s Neck (1971). The texts used in the final production included most of Blood on a Cat’s Neck, a piece written by Fassbinder himself as a young teenager (the “Vertex” piece which began the evening) and a short piece written by one of the performers, Michelle Outram. The title Pre-Paradise, however, was retained as Caitlin felt, rightly, that it was very evocative, especially for the young performers with whom she was working, many on the cusp of adulthood.

And you’re quite right in regard to the filmic feel to the production—not only is Caitlin influenced by Fassbinder’s films and visual aesthetics, but this early play contains a number of images, situations and characters which Fassbinder also included in later films.

Best wishes,

Laura Ginters

We’re planning to work our way around the country with a series of overviews of theatre and performance in each state. Richard Murphet will report on a range of opinions from Melbourne in our next edition. Editors.

February 21, 2001

Dear Kirsten Krauth,

I greatly appreciate your review [of Cunnamulla, OnScreen, RealTime 41, page 14]—not only for its praise but for the story you tell.

If only I could reach out and touch more people the way I have to you—then I would be a happy man.

With best wishes,

Dennis O’Rourke

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 10

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Leslie Clark, Australia Ad Lib Project, ABC

How come we’re not talking about….

…the Melbourne Herald Sun’s revelations that Cinemedia industry development manager Julie Marlow had misused her company credit card and that creative director Ross Gibson had funded a project involving his partner? This is the question that the new media community was belatedly asking itself: where was it during the assault on Cinemedia, the Victorian government’s film, screen culture and digital media body? As Premier Steve Bracks and Arts Minister Mary Delahunty took up the ‘scandal’ with indecent haste, there was more than a suspicion that it was a prelude to the dissolution of Cinemedia and the revivification of Film Victoria. This has been something long sought by the film industry lobby as it enviously watched the NSW sector speed ahead over the last 5 years. It accused Cinemedia of being inflexible and was hostile to former Premier Jeff Kennett’s preoccupation with investment in new media. The guilty were proven innocent—a small oversight on the credit card, the grant process had always been transparent—but damage had been done, to reputations and possibly to screen culture (already embattled across the nation) and new media. How will the funds be allocated between Film Victoria and what’s left of Cinemedia? As per the lobby push, the latter will be re-named Screen Culture Victoria. Presumably the very word Cinemedia had too many postmodern connotations of a multiplicity of forms and technlogies. So where will new media fit? At a moment in history when the digitalising of film technology and the emergence of new forms (with popular as well as artistic potentials) are already with us, it’s important not to see new media as a mere sideshow. It requires investment, production facilities and an infrastructure body where it can show its name. Federation Square’s Centre for the Moving Image, a major investment in screen culture and new media, will be looked after by Screen Culture Victoria, but what does that really mean for the development of new media outside of exhibiting it?

Kosky moves in on Vienna

Congratulations to Barrie Kosky. You might not have caught up with the news of March 6 that theatre and opera director Kosky has been appointed Co-Artistic Director (with Airan Berg) of the 300-seater Schauspielhaus Theatre, Vienna, with government funding of $2.5m Australian per year and a 3 year contract. In press reports he says has no intention of cutting ties with Australia with projects still to be realised here. It’s already rumoured that he’ll be taking some of his favorite performers to Vienna for particular shows.

Have you got it?

Throughout this country’s history much of the music heard in theatre, dance-hall, cinema and club was home-made and improvised. The Australia Ad Lib Project wants to find out if such music still thrives within the communities of multicultural Australia. ABC Radio is making a countrywide survey and archive of this wild, weird and vernacular music alternative. A wide selection will be broadcast on The Listening Room, on ABC Classic FM, on Radio National’s Radio Eye and on the web later this year. The archive will also become part of the National Library and The Australian Music Centre collections. Co-ordinator Jon Rose says, “We’re talking about the whole tapestry of non-mainstream music action. We’re calling for extreme or unusual club acts, street musicians with attitude, improvising pipe organists, computer hackers with smart ears, karaoke performers with glass shattering voices, disenfranchised toilet wall poets, building workers with high decibel whistles…Examples already documented include Leslie Clark, the man who can play hundreds of tunes by clicking his fingers at the correct pitches; the disturbing sounds of Toydeath; the spacey telephone wire recordings of Dr Alan Lamb; the legendary Chain Saw Orchestra of Fremantle and Ron West’s Majestic Theatre Organ improvisations for silent movies. Contact Jon Rose or Sherre DeLys, GPO Box 9994 in your capital city. Tel 02 93331308 or ozadlib@abc.net.au

A winner

Congratulations to playwright and RealTime writer Christine Evans whose new short play Mothergun was one of 3 winners at Perishable Theatre’s International Women Playwriting Festival—it means full production, $US500 and publication in a book of the 3 works.

Happy birthday Performing Lines

Congrats also to Performing Lines and to its General Manager Wendy Blacklock for 10 years of hard slog practically singlehandedly touring challenging acts around this difficult country. At the RealTime-Performance space Vision Thing forum, Wendy spoke with great optimism of the future of Australia’s innovative arts. Never before, she said, had she sensed such genuine interest from audiences here and internationally. It makes you think what might be done with more money to promote the vision, not to mention a team of helpers to expand on it. This year Performing Lines will tour over 10 productions to more than 15 cities including William Yang’s Blood Links to America, Europe and throughout Australia; Crying in Public Places’ Skin round Australia; Arena Theatre Company’s Eat Your Young to Sydney, Brisbane and Canberra; Ranters Theatre to the Porto Festival in Portugal and Nigel Jamieson and Paul Grabowsky’s The Theft of Sita to Sydney, New York and London. For more see Performing Line’s brand new website: www.performinglines.org.au

Dance results

We hadn’t caught sight of the Australia Council’s New Media Arts and Theatre funding results before going to print, but the dance results reveal, amongst other things, a commitment to cultural diversity with support for Wu Lin Dance Theatre’s (VIC) Journey of the Northern Tiger; Rakini Devi (WA), a 2 year fellowship which will enable her to work with key collaborators, Rosalind Crisp and Nigel Kellaway; and Hirano (VIC) for LADEN (Little Asia Dance Exchange Network) on a 5 week international tour of contemporary dance performance workshops and forums in partner cities including Melbourne, Hong Kong, Taipei, Tokyo and Seoul. Also evident in the selection is a fair number of cross-artform and multimedia collaborations. The Gilgamesh Project (WA) involves performers and design artists from Australia and India, and musicians from Australia and Indonesia. Lisa O’Neill and Caroline Dunphy (QLD) are developing a movement/text performance piece (Rodin’s Kiss). In the Dark Productions (NSW) will work with 5 Australian performers to develop video material for a project involving UK director Wendy Houstoun. Susan Peacock (WA) will continue development of her dance theatre works Near Enemies and Crossing the Line. And it was good to see Sydney’s One Extra getting some real support for 2 projects involving Michael Whaites (see page 30).

NQ never had it so good

On January 23, Queensland Minister for the Arts Matt Foley made the much anticipated announcement that the joint accommodation submission for a purpose built facility to house both JUTE Theatre Ensemble and Kick Arts Collective had been successful. For a number of years both organisations have separately identified appropriate accommodation in the heart of Cairns CBD as their greatest need. Now, as a result of the $2.7million grant from the Millennium Fund, both can look forward to an exciting period of growth and development. The new facility will include a 200-seat theatre and rehearsal space as well as climate-controlled gallery and exhibition spaces, a digital media laboratory, meeting areas as well as much needed storage and handling areas. Both organisations are now required to prepare feasibility studies which among other things will determine the actual site for the Centre of Contemporary Art (CoCA). This will involve consultation and discussion with the many other arts organisations located around Cairns.

the road to Singapore

And while we’re up north, NQ artists Rebecca Youdell and Russell Milledge (Bonemap) have scored the first combined Asialink visual and performing arts residency. It’s hosted by The Substation Centre for the Arts in Singapore from April to July this year. Another exciting component of the 4 month residency will be the presentation of New Image – New Ways an exhibition of Australian contemporary art in Singapore featuring many of the Cairns region’s finest artists. www.bonemap.com

Rare Murphet

Richard Murphet’s innovative Dolores in the Department Store was first produced in a brief season at the VCA last year. The college is remounting the work, April 6 – 11, so don’t miss it. Performance, design and production is by students from the School of Drama, direction by Leisa Shelton and Richard Murphet.

New venue hits stride

Imperial Slacks is establishing itself as a regular Sydney venue for out-there performance. A brief description of their “non-house style” for April: a lifesize fullscale yellow horse becomes a rocking toy; an allgirl boy band drags through the city with the top down baby; a bumper to bumper salon of paintings; watch as a 3D animated business man’s head explodes; panorama painting morphs through grid to graffiti cityscape; interact with a portaloo in a way that Duchamp could only hope for. 2/111 Campbell Street Surry Hills. 02-92811150 islacks@projectroom.com; www.projectroom.com/islacks

UTP gets doco-ed

Routledge has recently published Eugene van Erven’s book Community Theatre Global Perspectives which features a case study of Urban Theatre Project’s Trackwork conceived and produced by artists in Sydney’s western suburbs as well as 5 other projects around the world—Peta in the Philippines, Stut Theater in Utrecht, Teatro de la Realidad in LA, Aguamarina in Costa Rica and Kawuonda Women’s Theatre in Kenya. The book is not widely available at Australian bookshops but can be ordered from Amazon and there’s an accompanying video which is even harder to come by.

Arty genitals

Whereas there’ll be stacks of the new volume on genital origami, Puppetry of the Penis, a new book based on a cabaret show (now at the Melbourne Comedy Festival) in which Simon Morley and David Friend manipulate their genitals into various shapes, objects and landmarks. www.puppetryofthepenis.com

Chris Ryan and Rohan Thatcher, version 1.0, The second Last Supper

photo Heidrun Löhr

Chris Ryan and Rohan Thatcher, version 1.0, The second Last Supper

Performance Space at full force

There’s a buzz about a surge of new works at Performance Space over coming months at the very same time that it’s been announced it’s losing its home (see page 12). The April-May program kicks off off-site at Technology Park with Party Line’s steel fracture, a multilayered performance event which unravels the impact of steel on women’s bodies through history. Digital artist Justine Cooper works with steel artist Jam Dickson and the astonishing Party Line performers are directed by Gail Kelly. Text is by Shane Rowlands. Back at the Space, Version 1.0’s The second Last Supper promises “Australian identity, Australian corporate ethics and new Australian cuisine—the seriously playful politics of the personal, the global and the local.” Also in April, Frumpus star in Crazed. In May, Andrew Morrish and Tony Osborne do Relentlessly On. In Tess de Quincey’s Nerve 9 the dancer weaves between the work of 3 of Australia’s finest contemporary artists—provocative poet Amanda Stewart and digital artists Debra Petrovitch and Francesca da Rimini. De Quincey focuses on feminine space which she describes as “an environment where body and textuality coexist.”

Also in May at Performance Space, there’s El Inocente “an incredible and sad tale of innocence and heartlessness” by Nigel Kellaway’s The opera Project. Asked what he’s really on about, Nigel wrote back: “Our task has been to draw attention to the discrete components that make up the performative act, eschewing the illusion of ‘reality’ or (more accurately) ‘totality’ that has been a concern of much of western theatre since the Renaissance. Like the dramaturgy, the music collides many styles and genres as one would find in opera or feature film. It has its genesis in specific Handel operatic arias, but now original music by Richard Vella interacts, complements, ignores or collides with Handel’s music creating a complex musical web. We are simultaneously experiencing a Baroque opera based on Handel’s music and a more contemporary approach to music theatre making. In a certain sense, the music is similar to that found in a road movie. It is neither pastiche nor parody, but is multi-referential—placing the listener into strangely familiar contexts, enabling the work to have multiple layers for interpretation.” And it’ll be wild!

Martin Hibble festschrift

Now, there was a talker. Music broadcaster Martin Hibble was a passionate collector of stage and film music. He regularly raided his vast collection for rare repertoire for ABC Classic FM’s Sunday Bon Bons and other programs. Martin died suddenly late last year and friends and colleagues plan to celebrate the life of this influential and passionate music advocate with a memorial volume. Did you ever meet Martin Hibble? Even if you didn’t, do you have some reminiscence of a particular program he presented, lecture he gave or review he wrote? if so, editors of this memorial volume would be interested to hear from you. Contributions can be emailed to James McCarthy at mccarthy@active-media.com.au or John Baxter on genet@noos.fr

Talking of criticism

Criticism in dance is the focus of the latest Ausdance publication featuring papers by Sarah Miller, Hilary Crampton, Shaaron Boughen and Lee Christofis from a forum held to coincide with the Ausdance Awards in January. The discussion continues on the RealTime website with Keith Gallasch’s contribution to the forum, “Dancing with words: the future of dance reviewing.” Some forms of criticism can be disturbing with artists often feeling work is not adequately accounted for. While praising Company in Space’s previous work in her review in The Age, Hilary Crampton couldn’t connect with their new work, Incarnate. Company in Space’s Hellen Sky wrote to us that, “Basic responses that seemed to be missing, even in terms of a conventional review, were anything about what the show looked or felt like, what the dancers were doing, what the screens were doing, what the images were, what the score was, what the camera shots were, what were the real time effects of the computer vision mixing, what the animations were…the dancers were not just doing tortured gestures, nor were they unaware of the real audience, nor were they restricted by the live camera performer; rather he was moving with them and in fact, therefore very much a live performer, another dancer. To me this is also choreography, the work is not just about a critique of steps, rather the vocabularies of all the elements, visual, design, live, virtual, real space, projection space, sound etc…”

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 11

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Tess de Quincey, Nerve 9, Performance Space, opening May 24

image Russell Emerson

Tess de Quincey, Nerve 9, Performance Space, opening May 24

The loss of the Performance Space in Sydney is imminent. The organisation has to leave its famous home by the end of the year. At The Vision Thing, a RealTime-Performance Space forum (Monday March 26), Nigel Kellaway spoke eloquently about how he cannot separate his work and its evolution from this space he has worked in for so long. When he envisions a show, he sees it in the Performance Space. However, given the impossibly high rental, the move out of the building is inevitable. What we all hope is that the spirit of the place will travel with the organisation. And that governments, state and federal, remain committed to the organisation’s future as it continues its search for a new home.

We spent 10 years ourselves performing in the building and like many can sense performances past and read the walls and ceilings for signs of decades of great work. We will lament its passing, especially at a time when it’s enjoying a surge of activity, but will passionately support its next incarnation as we hope all RealTime readers will. We asked Performance Space Artistic Director, Fiona Winning to explain the situation. Virginia Baxter & Keith Gallasch

After decades of intensive experiment and critical debate at 199 Cleveland Street Redfern, Performance Space is moving on. In the best traditions of experimental work we have no destination yet, but the search for a new and better place continues. (Sixteen potential buildings/sites have been investigated in the last 3 years with a view to relocating.)

The Cleveland Street space has been home to a huge family of artists and an enormous variety of works that have attracted national and international attention and acclaim. Over the years the immense body of work produced here has been critical to the development of hybrid performance, dance and visual cultures in Sydney and Australia. The debate surrounding that work has been fundamental to understanding the evolving languages of performance and the limits of its potentials.

Now we approach another limit. The increased costs of commercial rent, of running and maintaining the 70 year old building as a venue, along with static or decreased funding over the years, has resulted in our need to move out of this building at the end of 2001. For the last five years, the proportion of our annual income spent on running the venue increased—and the percentage invested in the art decreased. Late last year, the Board agreed that it is impossible to continue this trend without serious artistic compromise or economic risk.

The irony is that this is happening in a period of increased demand on the space, when many established and emerging artists are developing good work, when our audiences are on the increase and when there is a terrible shortage of rehearsal and performance space in Sydney.

Katia Molino, Nigel Kellaway, El Inocente, Performance Space, opening May 2

photo Heidrun Löhr

Katia Molino, Nigel Kellaway, El Inocente, Performance Space, opening May 2

This is not to deny there have been significant shifts in the performance environment over recent years. There’s been an exciting increase in site-specific work being made by companies such as Gravity Feed, Urban Theatre Projects, The Party Line, Nerve Shell and freelance artists such as Julie-Anne Long. But while this means they don’t necessarily need our venue to present their work, these artists have often based their operations with us while working offsite.

This increased interest in the use of other spaces, does not diminish the need expressed by many companies and independent artists for a performance space with a critical environment and a profile to premiere their work. These include The opera Project, De Quincey & Co., austraLYSIS, William Yang, Nikki Heywood, Rosalind Crisp and the stella b. ensemble, Morgan Lewis, Andrew Morrish, Trash Vaudeville, Frumpus, and Version 1.0. Companies and independent artists based outside of Sydney also require a space to tour their work from interstate—aphids, Hubcap Productions, Rakini, PVI Collective, Shelley Lasica and Stacey Callaghan; not to mention international artists such as Russell Maliphant (UK) and Jyrki Karttunen (Finland) and others.