Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

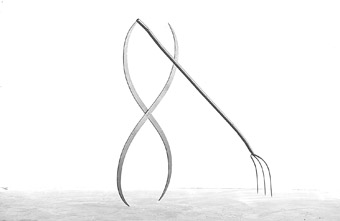

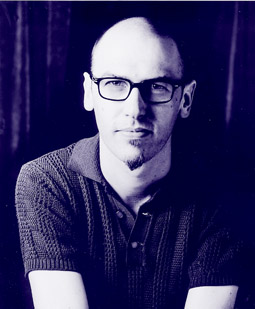

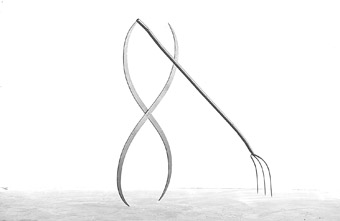

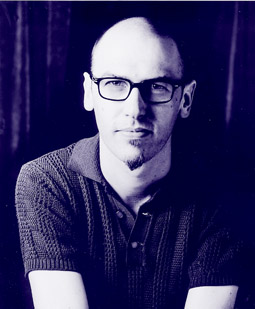

Neil Roberts, Things in the State of Belonging

collection, the artist, photo the artist

Neil Roberts, Things in the State of Belonging

If you soften your eyes, relax, let go of hard-edged purposes and intentions, you can look at objects differently—their textures, timbres, rhythms, how they have sat or walked in the world; not just their alliances and fights with each other; but also their gentler kinships, potentials, hopes to evolve.

There are forms of art which rely on the agon—a testing of object versus object, a gladiatorial match. And there are others which remember both the salt-taste of memory and the hopeful recombinant geometries underlying form. Although Neil Roberts’ work is largely sourced from objects-in-the-working-world (workgloves, cables, funnels, pizza trays), the weight of their uses becomes only a molecular part of their inherent qualities—and the cries for recombination that their edges yearn for.

Roberts in the studio: patient, peripherally scanning, hearing the cry of the object to mate differently, create a new creature, shift DNA.

So, when Roberts welds together a hoe and large caliper so that they lean into each other, strength resting in their paired fulcrum, teeth just touching the floor, they are both objects of labour (memory of sweat), and a black-bodied dance crossing air and time. Mantis and mantis coming to mate. Sweat and soil become proportional in a larger matrix which, like love, kisses into another space.

Take some umbrella frames—6 vacant hats, pincered pinnacles, girders for a seagull’s nest, perhaps; have them crouch atop 24 spidery long tubes of glass, messengers from the ground. Exquisite insects, aliens hovering; we stumble into a delicate world.

A long vein of old trowels hang along a wall, rusting diamonds embossed and flecked with fossils, millipede whorls, stones, glass fragments, a wallpaper rose, coiled wire like Rapunzel’s hair beginning to unfold. This series utters a quiet archaeology—echo of a building-site, childish trespass amongst grandfather’s toil, perhaps; but its thisness is stronger than sentimental memory: a tramline of tools, small meetings, shape within shape, what can a diamond hold. This is amplified by a roll-call of some 40 chalice-shaped petrol funnels along the parallel wall, their angular double-cupping echoing the negative space between those blades.

This sump-oiled Arthurian feast starts a reverb which connects to other objects in the room, most of which comment with soft inflection on men’s work/masculinity. The figures implicitly related to these objects are heroes, less so for their brawn or the violence of their strength, than the delicacy of the motion within their muscles, as the eye traces the necessary line of movement to a goal, and the arm and body fulfil their trajectories.

Roberts talks of “parallel universes…existing outside our perception, spending a blink of their existence in our known world.” This applies to actions both within and between people and objects, as well as to inherent qualities. At times, a nascent activity states itself (O2 drawn on a rusting tool). At others, the lines of energy between 2 boxers, or the swing of a punching-bag, becomes a drawing translated into leaded glass. Half Ether, Half Dew Mixed with Sweat wraps a carapace of Tiffany glass over a leather punching bag: fragile strength, harsh virility yoked in an embrace. “Go on, hit me,” they both seem to say. And how they might have moved, been moved, is also part of the piece: in its making, molten glass “flows slow”, as does the mind of the boxer punching sweet. Traditional church glass’s function was to “make visible the energy of God”; Half Ether’s leather, glass and lead literally hold each other’s lines of inspiration and flight. Their differences do not so much play out as dis/splay a new animal being formed.

Other works wrap wire, mesh or chain around cable, insulated wire, or bottles crushed by a goliath (a bikies’ night in). Baudelaire’s Rope (based on a short story about the rope used by a suicide which becomes an object of collectors’ desire) ponders how strangely a fetish-object is kept alive, the rope perhaps providing a link of relatedness that was missing in the suicide’s life; in this strange way, the suicide is held, perhaps for the first time. There is both astute social observation and a challenge to judgmentalism in this leaded posie whose cut lengths are only half-displayed. As with the head-banded cables of For Those Who Suffer Uncertainty there is a kind of sanctuary, a continuity of substance in the metallic embrace of something which has, or wants to, die, bequeathed to a livingness in the meeting of these wires.

Perhaps poignancy hits most in the blacksmithing aprons suspended from another wall: tired at day’s end, hung upside-down, the leather is patched with a splayed football opening like a flower. The aprons bare both gut and heart, hope and loss, an exquisite questing emanating from beneath the protective skins of work and toil.

The Collected Works of Neil Roberts, part of Metis 2001: Wasted, curated by Merryn Gates, Canberra School of Art Gallery, May 5-June 10

With thanks to Barbara Campbell for a transcript of Neil’s talk given for Artforum, Canberra School of Art, June 6.

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 39

© Zsuzsanna Soboslay; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

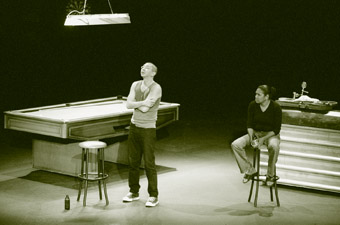

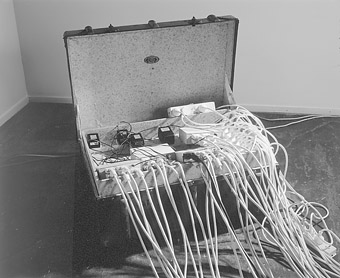

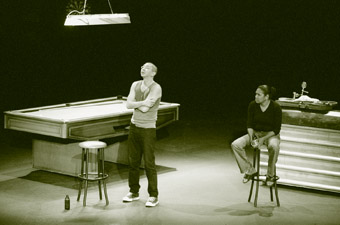

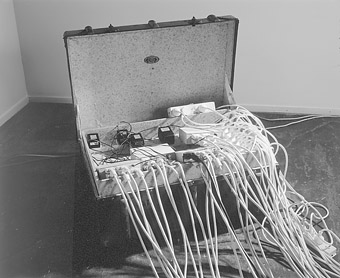

Hung Le, Ningali Lawford, Black & Tran

photo Jon Green

Hung Le, Ningali Lawford, Black & Tran

Deckchair Theatre’s recent touring production Black & Tran transports us, theatrically speaking, to a pub in Carlton (Melbourne) while transforming the performance space into a cabaret venue with its own bar—an invitation to settle down, relax and get into the swing of things. It worked for me and I hate pubs, particularly the ones evoked in this production. It’s the old fashioned kind that comes with a telly for watching sport, a pool table and a dartboard—the true blue, Aussie bloke kind of pub. I don’t drink beer, hate watching sport on TV, can’t play pool or darts and loathe the aggro and punch-ups that I associate with the beer guzzling, poofter bashing, sexist and racist stupidities of the dinki-di Aussie. Well that’s the way it was when I was growing up.

In general, I don’t like stand-up comedy either and for many of the reasons cited above, so I should have hated this combination of pub culture and stand-up, but I didn’t. I can’t tell you whether or not pubs have changed but in Black & Tran, you get the impression that these old fashioned bars are now a positive haven—given the tidal wave of gentrification that has swept over most cities—for those who don’t want to participate in the white majority middle class culture of wine bars and brasseries. In this pub, instead of a big white bloke with a red-neck and a gut wearing a singlet and stubbies with his crack hanging out, there—glued to the cricket on telly—is a lanky, bespectacled Vietnamese man. When his nemesis arrives, far from a head-kicking skinhead, she’s a cheerful Aboriginal woman who swings into the bar with a friendly, “Hey Tokyo, ya wanna game a’ stick?”

While Ningali Lawford takes some convincing that Hung Le, whose Australian accent is so broad you could thwack it with a cricket bat, is in fact Vietnamese-Australian and not Japanese, Hung Le himself has a bit to do in coming to terms with an Aboriginal Australian. As they trade tall tales and true and tell lots of totally tragic jokes about eating dogs and snakes in sometimes hysterically visceral detail, the audience cacks itself in recognition of all those racial slurs and cliches. Perhaps surprisingly, this first generation migrant and original Australian have a lot in common. Neither of them spoke English until their late primary years. Neither of them is seen to be a ‘real’ Australian and, of course, they share a loathing of Pauline Hanson and those of her ilk. Hanson—referred to throughout as the “Oxley-moron”—is the target of merciless satire.

Despite the trading of racial stereotypes and cultural misconceptions, this is an amiable piss-take rather than a savage satire. And unlike a lot of stand-up, its message is inclusive rather than exclusive, its thrust mildly educational and its concerns humanitarian. In this infectious and light-hearted production there are serious issues raised but, in the end, this show suggests that one solution to the problems of injustice, prejudice and intolerance, at least at street level, is to be found in humour and a willingness to engage with the regulars at your local pub.

So maybe it’s time for me to throw off my ingrained prejudices and head on down to the local for a game of stick. My pool playing would surely test the limits of anyone’s tolerance!

–

Black & Tran, director Jean Pierre Mignon, created by & starring Ningali Lawford, Hung Le, Deckchair Theatre, Victoria Hall, Fremantle, May 15-23, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, May 24-26

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 30

© Sarah Miller; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

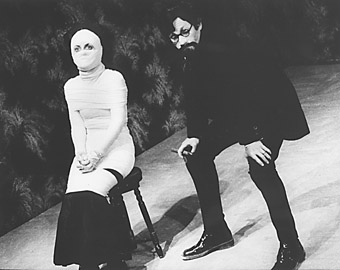

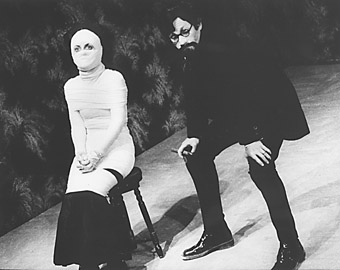

Brian Fuata, Museum of Fetishized Identities

photo Heidrun Löhr

Brian Fuata, Museum of Fetishized Identities

I was raised on a steady diet of Chekhovs performed in the manner and dialect of langorous English tea parties. It was a relief then to encounter the Benedict Andrews-Beatrix Christian version towards the end of its Sydney Theatre Company season (Drama Theatre, Sydney Opera House, opened May 11), angular, impassioned, unpredictable—a good test of a production for a play we know only too well. It remains curiously faithful for all its lateral moves, disk-spinning, occasional (if sometimes just too out of whack) contemporary references and magically eccentric, full-bodied and frightening performances—not without the requisite moments of reflection and interiority the playwright demands. “Hyper-real” is how the collaborators describe the characters, and I think they’re right. It’s the astonishing range of emotion and its moments of sharp visible embodiment that fuelled me. This contemporary playing doesn’t feed everyone in the audience. The familiar made strange got a bit too much for some: Irina’s insistent “To Moscow, to Moscow, to Moscow…” at the end of Act II was quietly met with “To Mosman, to Mosman…” by one disgruntled patron. But the performance manner is now, it is the future. But whose? Why is Masha singing Joni Mitchell’s paean to Woodstock—she can’t get it out of her head. It’s awkward, it jars, but it says that the dreams of 1968 have failed utterly. Act III looks uncomfortably like Bosnia. I’d just read Michel Houellebecq’s manic-depressive novel Atomised, so I was edgy about any more baby-boomer bashing (we get enough of that in the Sydney Morning Herald) and the denunciation of 400 years of less than humane humanism. So I went home in a spin, fuelled by the playing, emptied by an Andrews-Christian vision grimmer than any Chekhov I’d supped with before.

Guillermo Gomez Pena’s The Museum of Fetisihised Identities (Performance Space, July 5-14) was one of the most remarkable experiences of recent years, pulling my disparate atoms into fractal coherence across the 3 hour performance. The San Francisco-based Mexican artist and his cohort Yuan Ybarra collaborated with Australian artists for 5 weeks to create a set of living, recycled, sometimes mutating tableaux that transform an increasing number of the audience across the season into performers. As RealTime’s Kirsten Krauth put it: “It’s hard to maintain a passion for theatre-with-boundaries after experiencing The Museum of Fetishised Identities. A venue done up like a rave with performances fluid and revolving and great thumping music, where you can rove with a drink in one hand and a machine gun in the other is pretty hard to beat”. This tightly choreographed production moves from museum (a collection of bizarre cultural types, partly constructed from the performers’ lives) to ritual, culminating in the crucifixion of Ybarra with ‘Chicano’ scrawled across his chest (how does, Gomez Pena repeatedly asks, a Mexican become a Chicano).

Despite the cross, the skeleton that hangs above, the density of colour and sound and the specificity of Gomez’s own images (punch drunk Third World boxer, beggar dwarf, sculptor of terror tableaux using the audience) the whole feels less Mexican than aberrantly and creatively global ie not corporate. The Australian collaborators produce images that evoke constellated local subcultures (feminist lesbian warrior dj), public transgressions (a naked woman climbs into a perspex display box and smears it with breast milk), cultural caricature (someone in a kangaroo mask in a flailing dance with a cricket bat), foreign experience (the ritual of an Indian street beggar turned into an appalling fashion parade using the audience). Valerie Berry, Barbara Clare, Brian Fuata, Victoria Spence, Caitlin Newton-Broad, Rolando Ramos, Claudia Chidiac and Agatha Gothe-Snape perform with commitment and precision, some revealing surprising, new dimensions when deprived of their usual means of expression. Digital artist Jorge Cantellano (satirical, animated images of branded synthetic humans) and video installation artist Vahid Vahed (dark imagery of political torment across the last century) complete the picture—an exhilarating expression of difference in the age of globalism that sometimes stops you in your tracks. A bit like partying your way through the Apocalypse.

Urban Theatre Project’s Asylum (director Claudia Chidiac; May 31-June 9), in a disused shop in a western Sydney suburb was not at all celebratory. Its more familiar assemblage of monologue tales of the refugee encased in a fragile narrative nonetheless had power and poignancy because of the great strength of some mature performers and the immediacy of the political situation in Australia’s atrocious handling of refugees. We entered the performance area as refugees, hassled by officials we couldn’t understand and we watched the performance through wire as projected images (Denis Beaubois) and unfamiliar sound worlds (Rik Rue) disoriented us, as we tried, pertinently, to read the writing on the walls that these inmates patiently worked at. In the end a refugee is forced to go home, presumably to death. As heavy as the hand is that hits you with this, the truth is as horribly light as Kundera’s: it’s hard to walk from the space, to drive home in one piece.

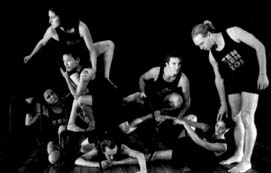

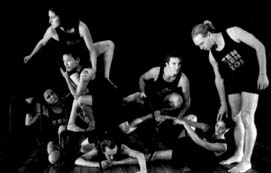

Critical Mass Theatre’s HAZCHEM (May 18-June 17) is bewildering and mysteriously affecting. A pre-show guided tour through the Wollongong City Gallery doesn’t prepare you for the council chamber balcony view through a mist of a yellow car atop a mound of sea-rounded rocks, a body flung across the car roof. It’s an image of beauty and of horror, the end of a story we’ll never know. What we witness seems to be some kind of aftermath in which perhaps a family is pulled apart, atomised. But HAZCHEM refuses such guessing and goes the way of reverie as headlines of crime and corruption and crashes and vast oceans wave across the chamber walls. A work siren sounds, grabbing everyone’s attention. So does rock’n’roll and the footy. There’s a brief sentimental evocation of a 60s holiday in the car, a trip to the Kiama blowhole. We’re sliding back. Trite memories and short-lived suspicions about pollution jostle, a comic but touching courtship is expressed in local terms (“you’re my smelter’), a slow death is mused over, and a running panic grabs thesel individuals (pulling them out of their cages, off their bikes, out of their preoccupations), until they unite atop the mayoral bench, yelling, punching the air, powerless. There’s been a car crash, a city has crashed, something has been lost. Deborah Leiser’s precise, visually intense direction yields focussed performances from a mostly experienced cast (Janys Hays, Bruce Keller, Jeff Stein, Bel Macedone, Ian McGregor) who know how to stretch time and contract space as well as how to act as the work switches between the imagistic demands of contemporary performance and fragmentary sketches of the everyday. I missed the significance of many of the local references and I wasn’t certain how HAZCHEM added up, so I wasn’t always at one with it and its sometimes cut and paste structure, but it’s a striking and worrying work. I hope Critical Mass Theatre (made up of artists with an association with the city) and its gallery partner persist in building contemporary performance in Wollongong.

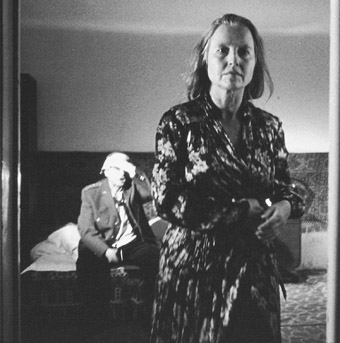

Bel Brown, Marianne Hender, Claire Burrow, 100 Confessions

photo Heidrun Löhr

Bel Brown, Marianne Hender, Claire Burrow, 100 Confessions

David Williams’ 100 Confessions in PACT Youth Theatre’s Forked Tongues (PACT Theatre, May 16-27) featuring 3 emerging directors (Williams, Cindy Rodriguez, Briony Dunn), is a chaotic party cum game cum social experiment that requires improvisational skills and timing that are mostly beyond its players. Even so, recurrent gags, playing with labels, dodgy confessions, shifting allegiances, outrageous scenarios, some strong indiosyncratic performances and seriously escalating tension yield a surprising level of coherence. Rodriguez’ Picasso’s Blood is the most assured work on the bill. As with Melbourne writer-director Jenny Kemp’s play with gesture, group movement, iconic text and obsessive behaviour, Rodriguez creates a dream world where characters split and multiply and the relationship between a Bluebeard Picasso and Dora Maar goes to pieces. Knife play, a blood obsession, a pair of limping marionette legs, and sound waves of ocean, soprano and vocalise female chorus recur with nightmarish intensity, evoking a labyrinth of love.

Verity Laughton’s Burning (Griffin Theatre Company, June 15-July 14) unfolds like a staged novel, explaining its way forward, labouring its cluster of secrets and the predictable revelations of a well-worn theatrical model. For a ghost story it lacks the dynamic of stillness and alarm that yield eeriness and fright and a hoped for epiphany. Laughton is at her best when poetic. In Burning the dialogue is for the most part too earthed, the scenario uncomfortably middlebrow, the naturalistic to-ing and fro-ing too busy. Yet the writer is onto something that white Australians need to engage with, their relationship with the land (even if it is someone else’s) built up over 200 years. Cloudstreet awkwardly explores some of this terrain (though not with Burning’s explicit Celtic focus) and Miriam Dixson (The Imaginary Australian, UNSW Press,1999) and Jennifer Rutherford (The Gauche Intruder, Melbourne University Press, 2000), among others, provide rich insights. I wanted Burning to work some magic on me, to answer, however poetically, however intuitively, a big question, but I couldn’t see past its mechanics (some of which, like the ramped, enclosing wall of photocopies were in fact magical). I left as I had come, incomplete. Atomised.

Kate Champion’s About Face (The Studio, Sydney Opera House, June 5 -16, see Erin Brannigan’s review) may have suffered from an overly episodic structure and a bits’n’pieces soundtrack, but its account of a personality attempting to reintegrate itself was powerfully conveyed by the interplay of the performer live before us and on 2 screens. A horizontal screen above revealed a slow motion, suicidal fall; a large vertical screen behind a door yielded an encounter with multiplying selves. On the screen above a survelliance camera caught Champion at the door of her apartment—trying to gain access to herself. Brigid Kitchen’s film and Sydney Bouhaniche’s lighting gave About Face increasing cohesion. In scale and focus they struck the perfect balance between live and virtual bodies.

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 32

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

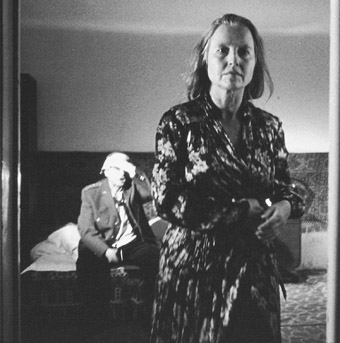

Audience detainees, Wild Knights

photo Heidrun Löhr

Audience detainees, Wild Knights

We’re driving out to the edges of Sydney. It’s cold and still. I’m going to see a performance in a remand prison for young men at Cobham Juvenile Justice Centre. The piece is called Wild Knights. The steady drive toward St Marys has me feeling like the event has started already, there’s that twist in the guts, a transaction is looming between me and…a Wild Knight, a young prisoner.

I know I will be a fleeting visitor to this veiled place, a nervous stranger who will leave, free. These young men have been consigned to the remand centre because they may have done something serious. They got caught and are awaiting sentencing. I am imagining these Wild Knights, compelled by the promise of a face to place alongside the cliches and stories of criminal youth, trouble, the violence in our lives and imaginations. I don’t yet know that my curiosity will not be indulged. It sure is cold. I dig deeper into my coat pockets.

Wild Knights is a performance event about ‘encounter’—with institutions, with myths, between human beings behind bars, those who are their jailers, family and strangers. It’s not a representation of prison life but plays with the palpable space between other and self, with real implications.

Wild Knights is a collaboration between Cobham Juvenile Justice Centre, High Street Youth Health Service and erth Visual Theatre, directed by Alicia Talbot. In a 2-hour show, devised by 10 young men (whose names are not revealed) with a host of professional artists and collaborators, the audience is sent on a privileged journey—to look at and momentarily experience a calculated initiation into this environment.

We are offered roles as “Detainees’, “Official Visitors” and “VIP Guests”, and taken on different paths through the complex and silent world of the juvenile justice system. While we encounter the mechanisms of discipline, evidenced clearly in the rituals of entry, we are privy to the defiance, incursions and exuberant gestures of the inmates and workers who populate the physical space of this prison.

Each audience member is asked to hand in their personal items at check in. Our phones, jackets and other items are sealed in a holding bag and we’re given an identity for the duration of the performance. I am a ‘detainee’ and loaded on a docking bus with tinted windows and plenty of locked chambers. All detainees are asked to don white suits for the initiation of a model prisoner.

A lot of the pleasure and dis-ease in this 2 and a half hour performance came from observing the reactions of audience to the protocols and impact of the place. At one point we were herded into individual cells, while a performance was conducted outside for “official guests and VIPs.” We gathered at one point to listen to a range of beautiful original songs, from rap to acoustic, in one of the many courtyards. A group of Wild Knights conducted a mysterious meeting; a mock court was held with corrupt officials and manic lawyers dancing around the defendant. Performers loomed overhead on harnesses, flying from the corridors through the space. A rhinoceros was admitted to a seedy nightclub while young men were savagely excluded. Others were presented with cups for bravery and imagination in a Hollywood-styled red carpet procession. Finally, in the glare and spectacle of fireworks, the Wild Knights ran across a dark field at a great distance from the audience.

Alicia Talbot, director and performer, talked to me about the making of Wild Knights, taking me through the minefield of making performance within a highly coded and patrolled institution. This short extract from her description of the project offers insight into a powerful collaboration between people in an extraordinary environment.

“When did art and the penal system come face to face? All the time. Constantly.

“Say, for instance, if anyone had said in January that in 6 months time I would have a group of young men, some of whom have been held 10 months without trial, wearing satin capes, in leotards and tuxedos and wearing latex masks of their own creation, walking on stilts, flying in harnesses and standing in front of fireworks, people would have said no…

“I believe that people are partially what you make them. From the very beginning I worked with the participants as a band of astounding young men, like the X-Men or Neo in Matrix. Society’s mutants are on the loose but if they go to this special school, and use their talents in a special way, they actually become the saviours of the world. Neo’s code and moral honour is something that he understands and fights for.

“I look for the opposite of what we expect. In a place like prison you may find a band of holy men. Does anyone who drives along the highway realise that a 14-year-old boy is in his underwear in a holding cell for 6 hours?

“That these men survive the system and are still alive makes them heroes and that does not make me blind to their faults. In fact, residing in all heroic figures there is hubris, leading to nemesis.

“When we were having a party after the show and a young man said to me “So, what is it like to be working with criminals?” I looked around at the workers, artists and young men and said, “Oh my lord, are there criminals here?” I don’t know how I would have worked from that starting point. I like to think of them as outlaws.

“My challenge to those young men is—how can you be an outlaw and still go home at night? How can you fight for what you believe in and still go home at night?”

Wild Knights, presented by High Street Youth Health Service and Cobham Juvenile Justice Centre; directed & co-devised by Alicia Talbot with 10 young men from the Cobham Juvenile Justice Centre and erth Visual Theatre (Scott Wright, Margie Breen, Cathrine Couper, Sebastian Dickins, Phil Downing, Sharon Kerr, Adam Kealy, Adam Kronenberg, Morgan Lewis, Johnathon Krane). Co-ordinator of Programs and Staff Development Carolyn Delaney; art teacher Keira Minter; music produced by Phil Downing; lighting Neil Simpson & Clytie Smith; video Finton Mahony & Clare Britton.

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 33

© Caitlin Newton-Broad; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

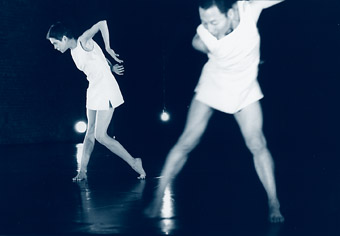

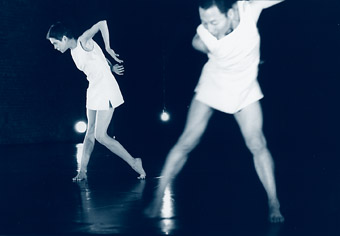

Lisa O’Neill, Vanessa Tomlinson, Double Vision

photo Maree Cunnington

Lisa O’Neill, Vanessa Tomlinson, Double Vision

An image of the soles of Lisa O’Neill’s feet has stayed with me for some time after seeing Double Vision. Their wrinkled, abstruse folds seemed to convey an interaction between the interior secretive world and something made far more explicit, a dynamic that framed the more complex cross artform elements in this work. The manner in which those feet, seemingly possessed, drove the splayed torso of O’Neill across the stage confirmed the marionette-like status and powerlessness of that childlike figure. The feet moved in the direction of a little heart shaped red pincushion, a gift referred to in Maryanne Lynch’s text as given by one ill-fated mother to an ill-fated daughter. The child moves to re-embrace the mother. A memory revolving around the nostalgic symbols of pathos, love and loss surges hopefully towards some kind of reconciliation.

Double Vision, a performance-installation driven by writer-director Lynch, involved singer Christine Johnson, composer John Rodgers, percussionist Vanessa Tomlinson, dancer Lisa O’Neill, sound designer Brett Cheney, designer Selene Cochrane and lighting designer Matt Scott. The performance and creative development was funded and resourced principally through the Queensland Performing Arts Trust. Normally associated with mainstream productions such as the Edinburgh Military Tattoo, this kind of commitment from QPAT to contemporary Australian work merits high praise.

The stated intention of the work is “an exploration of motherhood—as viewed by daughters and lived by mothers.” Lynch is fascinated with iconic crime and, in this instance, Double Vision utilises 2 texts drawn from mothers whose lives are marked by the murder and misfortunes of their children and the subsequent judgements of society: Mary Murphy of the Gatton murders incident and Bilynda Murphy of Moe in Victoria.

I have often seen performance installations or cross artform projects which dissolve readily into a set of perceptions: ‘oh, the musician is moving an object again or playing at being a visual artist.’ Thankfully that was not the case here. The dense and complex structure, as the title suggests, allowed the audience to shift their focus between multiple events, in and out of the visual details of any one moment or the physical interiority of any one sound. I appreciated the ambition.

Two crinoline-like structures dominated the stage. One seemingly eviscerated and ribbed provided a birdcage littered with various percussion instruments and 3 gutted pianos, symbols of female domesticity, of soirees to entertain friends and family, the mark of bourgeois education and learning. They seemed and sounded rotten. Tomlinson acted upon their destroyed innards as a graveyard caretaker might to an old wooden coffin.

At the other end, Christine Johnson was immobilised upon a covered crinoline that thrust her upwards towards the lighting grid. The head of Johnson, like the feet of O’Neill, seemed divorced from the rest of her body. But her voice readily enveloped the audience and in one section the tearing agonised refrain of a mother seeking her lost child hammered out. The folds of the crinoline seemed as if the child could have hidden there and emerged at any moment. This was not to be. Mary Murphy is quoted in the text: “The pain is piercing me until I could die.” These were the moments that attempted to pierce the audience, to give some intimation of what that pain could be.

Recorded voices of women and children told their stories. A long necklace of jewelled lights snaked out behind one of the crinolines. A balloon was performed upon. A lot of small details, the symbolic minutiae of torn lives, emerged when I appreciated this work in hindsight. The strength of Double Vision lay in a cohesive integrity that refused to signal every moment to the audience or tell them what to think.

This is a group of artists that I would like to see together again in a future collaboration.

Double Vision, writer/director Maryanne Lynch and collaborators, Merivale St Studios, Brisbane, July 10-14

Lisa O’Neill is also appearing in l’attitude at the Brisbane Powerhouse

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 33

© Daryl Buckley; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

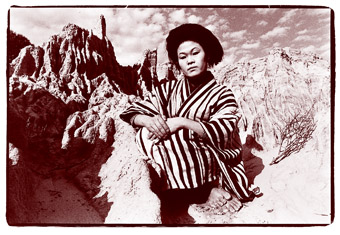

Lisa O’Neill, Caroline Dunphy, Rodin’s Kiss

photo Rowena Mollica

Lisa O’Neill, Caroline Dunphy, Rodin’s Kiss

The Brisbane Powerhouse’s push to develop a live arts community locally, nationally and internationally is reflected in the breadth of programming on offer in 2001. The Queensland Sacred Music Festival, a public artworks program focusing on the still-growing venue and Transmission, a community and arts development program, have all boosted attendances by creating new audiences. All this work and more takes influence from both Australian and international contexts. It seems a healthy community is growing which is absorbing and reinvesting these experiences to alter the cultural ecology of Brisbane.

The millennium year saw an inaugural program of work from Queensland-based independent contemporary dance, performance and installation artists, bracketed in a season titled l’attitude 27.5° (the name refers to the geographical location of Brisbane, distinctive if somewhat French/exotique/nothing else). The 2000 programme hosted a triple bill evening of work by Brisbane choreographers and a site specific hybrid work, Bonemap, from Cairns-based artists. The success of this season encouraged the Powerhouse to build overseas links with Glasgow’s New Moves Festival which not surprisingly has picked up Lisa O’Neill’s FUGU SAN for their next season.

Now established as an annual event, l’attitude 27.5° in 2001 is marked by a variety of collaborations. As assistant directors for the Frank Austral Asian Performance Ensemble, Caroline Dunphy and O’Neill are teaming to create a new hybrid work, Rodin’s Kiss. Both are contemporary performers drawing their experience from Suzuki Actor Training alongside a more traditional western-based dance and drama training.

The collaborations are not just local. In 1992, Vanessa Mafé and artist Jondi Keane formed a group in Geneva with Markus Siegenthaler and have continued to make work across continents—both Mafé and Keane are now Brisbane based. Durchblick/(Entre)voir Land(e)scape began its life during a 3 week workshop between Mafé and Siegenthaler in Switzerland in early 2000 and together with Brisbane lighting designer Jason Organ, French dancer/choreographer Marc Berthon and French composer Dominique Barthassat, the group has collaborated to develop this work which will have performances in Geneva, Zurich and Neuchatel after its Brisbane premiere. The excitement for these artists as they meet across space and continents lies in sharing past experiences, the reconfirmation of self and the exploration of new territories. For Mafé, problems only occur when an artist remains static, locked in zero growth.

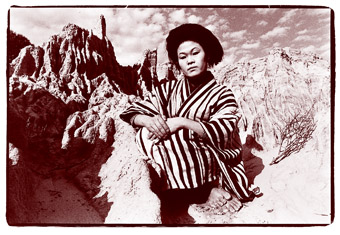

Anna Huber, Lin Yuan Shang, L’autre et moi

photo Cibille

Anna Huber, Lin Yuan Shang, L’autre et moi

A similar cross-cultural collaboration drives L’autre et moi which explores the differing cultural socialisations as experienced by 2 choreographers, the Taiwanese-Chinese Lin Yuan Shang and the Swiss, Anna Huber. Closer to home, a foyer installation reveals the collaboration between Australia and England that was La Bouche, a mixed media group operating in Europe and the UK during the 80s. Many of the artists involved now live in Brisbane and this is a retrospective look at their ground-breaking work.

IGNEOUS, a Lismore-based multimedia movement theatre group, will be company-in-residence for 6 weeks at the Powerhouse leading classes and developing performances. Co-artistic directors Suzon Fuks and James Cunningham will be joined by South Indian Kalaripayatt master, Vinildas Gurukkal, who they started collaborating with during a recent Asialink residency.

At a national level, other attractions include SPRUNG with choreovideography by Cazerine Barry from Melbourne and the playfully clever Andrew Morrish, with his improvised Relentlessly On creating late night l’attitudes!

Post-show forums are becoming increasingly popular with Brisbane audiences as artists unpack their works for those new to contemporary practices. With the new media potential of the 21st century, new forms and disciplines need fresh eyes to appreciate the poetics of such works. Seasons such as lâattitude 27.5° provide rich and varied approaches to creative processes.

In a world of chronic consumption of the new, many of the works refuse the urge for instant gratification. Instead they offer complex collaborations, not only cross-cultural, cross-genre and cross-discipline, but also across time and space.

l’attitude 27.5°, curators Gail Hewton (project manager) & Zane Trow (artistic director), Brisbane Powerhouse Centre for the Live Arts, Brisbane, September 24-October 15

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 34

© Shaaron Boughen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Yumi Umiumare, Sunrise at Midnight

The 3 finalists in the General category at the Dendy Awards this year—Blowfish, Sunrise at Midnight and In Search of Mike—all involve dance practitioners. Neither fiction, nor non-fiction, these films sit somewhere else amongst the traditional categories of cinema, probably most closely affiliated with the historic avant-garde. Dancers or choreographers and filmmakers who have previously worked with dance are the only characteristics these 3 shorts have in common, and each needs to be considered for its very individual approaches to the short film format.

Sunrise at Midnight, featuring Melbourne dance-makers Yumi Umiumare and Tony Yap and directed by Sean O’Brien, is a cinematic study in the most poetic mode. Introduced by Umiumare in voiceover as she makes herself up in traditional Japanese style, the film is based on the story of a troupe of female Japanese performers who travelled around Australia early in the last century, and a woman who lost her way in the desert. Shot in black and white, it recalled the pace and certain attention to texture in the producer Sophie Jackson’s early short, Swing Your Partner, which featured a middle-aged couple in their wedding clothes dancing to a country love-song. While that film focused on the rhythm and progression of the dance, Sunrise at Midnight focuses on the stasis of the characters as much as, or perhaps even more than, their movements. Umiumare and Yap both have Butoh backgrounds, and this aesthetic is ingrained in—almost in the grain of—the film. The peculiar and terrifying darkness of the Australian outback collides with this Asian dance method to literally and effectively illustrate the story which is at its heart; a Japanese woman alone in a landscape that is intensely foreign and cruelly unforgiving.

But this simple reading of the film doesn’t really stick, and it’s the temporal dimension that squeezes more out of the situation depicted. Umiumare has spoken of Butoh as a dance of darkness but more than that, a journey through the darkness toward the light. The Japanese character doesn’t appear to be fighting or struggling with her situation, but absorbing it and experiencing the landscape she finds herself in, almost becoming a part of it through the framing of the camera. The appearance of another figure (Tony Yap) doesn’t break her isolation but oddly fills out the environment.

South Australian choreographer and dancer Tuula Roppola co-directed and stars in a film that can be more simply labelled a dancefilm due to its style and content. Blowfish features a solo performance by Roppola (if you don’t count the rubber blowfish) accompanied by a voiceover describing, in very banal terms, her actions. She works mainly against a wall and is framed quite tightly so that her physical articulations are very much at the centre of the film. The stop-motion creates an affect where the transitions from one position to another are elided and Roppola appears to be moved by an exterior yet invisible force. European filmmaker Pascal Baes had great success on the dancefilm circuit some years ago using this technique in his films Topic II and 46 Bis which featured dancers gliding down the streets and around courtyards in a bizarre and muted ‘dance.’ Baes went on to make ads for the Philip Starck hotels which featured a weary traveller gliding into a hotel foyer, up the stairs and into bed.

Roppola’s film, co-directed by Ian Moorhead, doesn’t really do anything new with this technique, but Roppola’s performance is compelling and her apparent lack of agency evokes a characterisation of sorts—a woman who is merely going through the motions, or, moved by another’s commands.

The winner of this category and the overall winner of the Dendy Awards, Andrew Lancaster’s In Search of Mike rides across a variety of forms or genres from music video to dancefilm, fictionalised documentary to queer screen. Writer/performer Brian Carbee (see interview, RT41 p27) plays himself and his mother—both young and old—in a bravura performance that is the real heart and soul of the film, even though objects, characters and domestic spaces (bedroom, kitchen, loungeroom) have almost equal resonance throughout. This film conjures the temporal shape of its story through its material details: a doll, a cowboy dress-up set, an oxygen tank, a set of false teeth. These objects stand out against an environment that is at once recognisable and then a surreal any-space where the young and older versions of the male lead overlap in a succinct coming-of-age scene. This particular scene features the only dancing per se, and even this is more like a cross between a tantrum and a frenzied nightclub scenario. The skills of Carbee the dancer and choreographer can be found more in his regular actions—dressing, sitting, gesturing while on the phone; there’s a kind of grace and ease there.

And then there’s the language. Lancaster has spoken about his interest in creating films to existing or specifically devised scores, for example his videoclips for Custard, Lino, You am I and Midnight Oil and his soundtrack driven shorts Palace Café and Universal Appliance Company, and has described the appeal of Carbee’s voice and script to his aurally-obsessed tendencies. Carbee’s grainy tone and American accent and his rhythmic writing style combine with a film score by Lancaster’s band Lino, to add another level to the film that is as rich and varied as the visuals. Carbee’s skill in evoking the intriguing character of his mother through her words may be inherited. In the film he says: “My mother doesn’t so much turn a phrase as flip it on its back and fuck the shit out of it.” Combine this kind of talent with Lancaster’s innovative and eclectic approach to short filmmaking and you’ve got yourself a winner.

Dendy Awards, opening day of the Sydney Film Festival, State Theatre, Sydney, June 8.

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 35

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Tess de Quincey, Nerve 9

Nerve 9 is a work by 4 women—solo dancer/choreographer Tess De Quincey, audio visual artist Deborah Petrovich, poet/performer Amanda Stewart and writer Francesca da Rimini—whose contributions have been collected under the banner of De Quincey Co. Nerve 9 comprises 9 movements, each with a title—”Archaic domains”, “Tensile zones”, “Flesh of everyday speech”, “Porous matter”, “Tongue of sacrifice”, “Enigmatic hallucination”, “Black continent”, “Infinity emerging”, “Decentering”—mostly from the writing of Julia Kristeva, around which the artists’ materials have been arranged. The fifth title, “Tongue of sacrifice at the edge of the other”, was provided by Stewart. The work is a tight weave of dance, sound, text, sonic and visual imagery, and although De Quincey’s subtle movement often steals the visual focus, her work is really more of a thread which runs throughout the complex totality. Nerve 9 exists by virtue of all elements together; even the printed program which elucidates the work’s 9 sections is in the form of a visual score.

Nerve 9 is hybrid in essence and pushes the creation of visual, sonic and dance scores out from the far corners of the imagination, creating an intellectual arena within which all the ideas can grow and mingle. It synthesises some quite rarefied elements—Stewart’s shimmering sonic and visual poetry and De Quincey’s enduringly watchable portraits of attenuated human frailty. The different sounds (both text and soundscapes) and movement are entwined, as if De Quincey’s body can be shot through with those textures, human and electronic, structured and hanging on shafts or webs of sound, animated sometimes entirely by those vibrations.

The filmic and visual imagery provides a kind of harder-edged structure for the work, delimiting the 9 sections as they shift and change. It further expresses and clarifies a central theme, that of textual richness and diversity—of language, and the cultures from which it springs; of the flesh, which simultaneously grows into, out of and away from those cultures; and of the environment, seeping in, penetrating, escaping from, deflecting.

De Quincey’s performance has a depth and lucidity that is immensely readable and challenging. Her movement is neither naturalistic nor mimetic but often particularly expressive of human frailty and sensibility. Emotional qualities are strongly captured, but not with an overt sense of drama. Sensibility is expressed through highly and minutely wrought body language. She seems to work with ideas, particularly internalised and embodied, rather than with overt and consciously planned movement. It’s possible to see a physical narrative unfolding through the work—the flowering of a peculiarly acute register of human sensibility, the medium through which a person experiences the world.

As the work opens, a slim needle point of light pours downwards, as if from the darkness of a cave, light seeping out through a pinhole in a membrane, a tiny opening in the blackness, a stain imperceptibly widening, a deep drone. Then there is wind, whispering, bird sounds, the dancer’s body quivering, flinching, almost doll-like. A feeling of animation and coming to life. She opens her eyes with the sounds of water and whispering. Later there is singing, and the sight of a city—electric lights, signs, letters, neon. She is sensing, sentient, responsive, a grain of humanity, light and sound pierce her body. Blocks of light tilt behind her; she walks, looking back from where she’s come. There are people here. She has a wilted staggering gait, hands limp, “a body called flesh.” And then sometimes she seems not so much a person, more a passive idea, some other form of life. Then, on the screen, there are mouths speaking, foreign languages, texture in the sound, the lips sticky with lipstick, the skin, the eyes, all female. What are they speaking about? All those words, behind and in front of her, all those letters, that sound, becoming part of her. And could there be, among all this, a simple act of listening, an act of seeing, or of speaking?

–

Nerve 9, De Quincey Co, Tess De Quincey, Amanda Stewart, Deborah Petrovich, Francesca da Rimini, The Performance Space, Sydney, May 27

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 35

© Eleanor Brickhill; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Kate Champion, About Face

photo Heidrun Löhr

Kate Champion, About Face

Sydney audiences have recently seen substantial new programs by 2 experienced practitioners who have returned to Australia after working with the 2 companies most associated with the dance theatre genre: Michael Whaites (Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal) and Kate Champion (Lloyd Newson’s DV8 Physical Theatre).

Dance theatre is an interdisciplinary approach combining movement and dance with theatrical elements such as narrative or drama, characterisation and spoken text. This type of dance is distinguishable from other contemporary approaches such as deconstructed or abstracted ‘pure’ dance (Merce Cunningham, William Forsythe) or more research-based, less theatrically-oriented work (Deborah Hay, Lisa Nelson).

What rises to the top with dance theatre, and is common across the 2 divergent schools represented by Bausch and Newson, is an investment in the potential of gesture to both produce and subvert meaning. Combining dancerly skill with the gestures of everyday to create ambiguity, provide commentary or deconstruct social and cultural norms, is the most common methodology.

In Oysterland, directed by Whaites and performed by Kay Armstrong, Julie-Anne Long and Jan Pinkerton, a dramatic, gestural kind of movement is used to fill out a rambling meditation on the female experience. We’re introduced to these women via the sort of frenzied and loose solo that reveals people’s truest moves and makes an immediate impression. From here on in things are much more carefully articulated, deliberate and pointed. Pinkerton in full ski gear parades the stage, shaking her hands, which rattles the clasps on her ski gloves, chattering like a rat; Long slides along a wall and across the floor in sensual delirium (or is it merely exhaustion). Talk about flabby upper arms, weight problems, menstrual mythology and face creams slips around uneasily and is gone, but the quality of a familiar movement that’s been forced off kilter, like the simple swing of Long’s bob as her head drops pathetically sideways, fills me in and opens things up.

Reading the gestures of Champion’s character in About Face, we find ourselves in a vacuous urban life, drained of any meaningful relations, memories, clues. A treadmill walks her to nowhere, tentative steps check out her apartment and locate the furniture, desperate and repetitious gestures of frustration erupt at the kitchen table, yogic balances, wobbling tip-toes, a choreographed inventory of her physical self…Everything points in one direction and it’s off the map. While these gestures manipulate and transform everyday activities and actions, their messages are clear, creating a definite thematic of lost identity.

Another key element of dance theatre is the workshop process which draws on the experiences of cast members to construct a piece from the ground up, building it around the particularities of the performers’ bodies and lives. Whaites’ Achtung Honey was created with another Australian, Allison Brown, while they were both working in Germany and circles around the theme of displacement. In one section, movements from other works in other places bubble up accompanied by the names of European cities. A game of hide and seek in lederhosen, a melodramatic solo with telephone, and an intimate—perhaps cheekily Romantic—pas de deux all bristled with homecoming joie de vivre.

While the connection between the performers and the theme in Achtung Honey is clear, Champion, as with her previous solo work Face Value, has us speculating about the boundaries between art and life. The physical inventory described above is obviously an account of her body, yet this character is caught in a surreal no-man’s-land. I wonder what kind of exploration led Champion to this work. The thematic choices she makes find their voice in her body, and the 2 things become thoroughly entwined.

The proximity of the performers to the theatrical material, and that material’s close connection with the gestures and postures of everyday life, brings us to a third driving characteristic of dance theatre—an emphasis on social and cultural relevance. Both Oysterland and Face Value trace out intensely feminine spaces, suggesting that these artists have something to say about the contemporary female condition, but the dimensions and nature of the worlds depicted are very different.

There is an odd sense of order in Champion’s world despite the apparent chaos. Isolated, disorientated and stressed as she is, the neat and effective design elements, slick projections and seamless performance frame the characterisation with a sort of comforting control. How is this isolated woman going to operate beyond the parameters of her home and the security of her competent, exploratory movements? How does her state of mind project beyond this surreal domestic enclave? The general thrust of the work is more inward and singular than a general commentary.

In contrast, Oysterland seems at times to be opening up to infinity. Kay Armstrong explores the particularly feminine ploy of dressing-to-please. Jan Pinkerton often retreats into intimate activities at the back of the stage such as eating, bathing or reading. Julie Anne Long sometimes trudges around the stage and leans against its supports as if she is at home. And then there are trolleys and historical texts that open up yet more spaces where the feminine lurks.

Champion and Whaites, Long and Armstrong, as well as other Sydney artists including Brian Carbee (see page 35), Jenny-Newman-Preston, Lisa Ffrench and Dean Walsh, all explore the terrain of dance theatre which has room within its general form for the various approaches they represent.

Kate Champion is currently working with Michael Whaites on Stir, a 5-week 1st Stage Development produced by One Extra involving 3 choreographers (Whaites, Julie-Anne Long & Rosetta Cook), 9 dancers (including Champion, Kay Armstrong, Narelle Benjamin and Linda Ridgeway) and 7 dance students from CPA, QUT and WAAPA.

–

Achtung Honey, choreographer Michael Whaites, collaborator Allison Brown, performers Michael Whaites, Celia Brown; Oysterland, director/ choreographer Michael Whaites, performers Kay Armstrong, Julie-Anne Long, Jan Pinkerton, One Extra, The Seymour Centre, May 23 – June 2; About Face, deviser/ performer Kate Champion, composer Max Lyandvert, filmmaker Brigid Kitchin, The Studio, Sydney Opera House, June 15-16.

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 36

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Pervert

photo Louise Taube

Pervert

People make work for different reasons. What unites these 3 pieces is a strong sense of artistic concern, especially in terms of content. Pervert, by Louise Taube, has been a long time in the making, reflecting Louise’s intent to explore and represent issues of spectatorship, desire and sexual difference. There are 2, perhaps 3 protagonists to this tale. One I shall call misogyny (the man), the other narcissism (the woman), and the third a Jungian anima, archetype of the female.

Through clever use of multiple video cameras, screens and curtains, a great deal of observation occurs on the part of both the characters and the audience. The setting is contemporary grunge, perfectly evoked in the HiFi Bar and Ballroom, which consists of several rooms, bars and a stage of sorts. Several young dancers do party-club impersonations, mirroring the narcissist’s kinaesthetic pleasures. A narrative develops between the man and the woman. Their interaction is always mediated, whether by video, telephone, time or space. In fact, they never really meet. The feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray would be pleased, for she thinks there is a vast difference between man and woman.

In the end, the man is killed off, the woman preferring the company of women to wolves. Although we cannot be too sad about this (he was revolting), there is something unsatisfactory here. For this was not just about a bad man. It was also about the woman’s subjectivity, especially her narcissism which was represented through the pleasures of movement. This bespeaks the need for more outside direction, not merely to direct the traffic of virtual and real images, but also to work through the nuances of the female character.

Simon Ellis’ Full is a delicate piece in comparison. Set in the tiny Glass Street Gallery, North Melbourne, it begins with the sounds of Simon’s grandmother. She speaks with simplicity of her life, nearly over. She tells us of her work, the loss of her husband, the cat she misses. Ellis lies in a glass box, suspended over the onlookers. Naked almost, he is born unto this piece. We hear more about the grandmother as Ellis descends amongst us to dance a life over time. Slides of her are projected onto his white shirt, words spoken by a young voice, displacing the logic of time just enough. The final image ensues from her remark that the dead are outside, wanting in. Ellis places himself against the roof’s skylight. The cold pink of the sky beckons his silhouette. The dead are there, amongst us. Whether we see them depends upon whether or not we look.

Chamber by Shaun Mcleod is a meditation on maleness. Not your standard ocker masculinity but the kind of men you might know and like. And yet, they cover each other’s mouths, cutting off speech. When they are nice, they nestle heads, they echo each other’s movements, creating a kind of harmony. When they are not, they move out of synch, forming an uneasy dance.

Chamber is substantially improvised. The focus of the performers is great. Mcleod sits at the back of the theatre watching these young men play out the echoes of his imaginary reflections. How much was this about masculinity? It is hard to say, in that this was not about stereotypes. So, in a sense, just because it was danced by men, it was about men. How then to move beyond that? Is this a reflection of how things are or a dance into the future of possibility? The ending, which juxtaposed poetry with Jacob Lehrer’s comedic meanderings, seemed to suggest a future. But it was hard to make out. The light was fading. The words were disappearing.

Pervert, xn, music Mik La Vage, performers included Shona Erskine, Taube & Gred Ulfan, Hi Fi Ballroom and Bar, June 6-13; Full, creator/performer Simon Ellis, music Jacqueline Grenfell, installation & design Elizabeth Boyce, Glass Street Gallery, June 20-30; Chamber, Shaun McLeod, performers Simon Ellis, Martin Kwasner & Jacob Lehrer, video Cormac Lilly & Christina Shepard, music David Corbet, Dancehouse, Melbourne, July 7-9

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 37

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

ADT, Birdbrain

courtesy ADT

ADT, Birdbrain

This is the fourth version of Garry Stewart’s Birdbrain and the second version I’ve seen. It begins with a portable, plastic record player sitting on the empty stage. Kristina Chan sits and plays snatches of the overture to Swan Lake. The record crackles. Stewart’s endeavour is established. This ballet classic will be sifted through contemporary technology and responded to by contemporary bodies.

Tchaikovsky’s music triggers memories of that celebrated ballet of love and deception but there is no time for nostalgia. The overture is intersected by a different music, designed by Jad McAdam and Luke Smiles. This music pumps. The company enters. The dancing in this section is tight, presentational and formal but there’s something electric about these dancers. They are wired for fast, exacting shifts of position, line and spatial orientation. I recognise moves from ballet, Cunningham technique, yoga, acrobatics and breakdancing. But each move is transformed through juxtaposition and the way in which these dancers’ bodies are organised for risk and range. (Stewart loves extreme stretch and moves that require phenomenal strength.) Fiona Malone and Tanja Liedtke appear at one stage in school uniforms. This image is disquieting—ballet as a schoolgirl fantasy, ballerinas as male sexual fantasies. Finally, terms associated with ballet flash at the back of the stage, the video screen framed by panels designed by Gaelle Mellis, each bearing a Renaissance image of a ballet dancer which is barely visible, silver on grey. Ballet history is present but fading. This opening treatise on ballet ends.

Then the real ballet begins. Ideas, images, references to Swan Lake flash past us in the movement, as words printed on T-shirts, as images behind the video screen and in Tim Gruchy’s video footage. The use of language to denote aspects of the original ballet makes the commentary hard-edged. For instance, at one stage a dancer labelled “royal disdain” duets briefly with a dancer labelled “peasant joy.” However, this hard-edged wit plays second fiddle to the dancing. A few of the highlights are: Larissa McGowan’s solo in which she turns herself inside out, shuddering and quivering as she transforms from a swan into a woman; Antony Hamilton’s ‘the story so far’ and ‘dying swan’ dance behind a pulsing, slow zoom in on a photo of one of the famous Odette/Odiles taking a bow (strangely moving); the linked-arm quintet of Queen, evil Rothbart, Prince Siegfried, Odette and Odile, making these characters an entwined entity; the ‘drowning of the lovers’ in which the dancers run in, perform spread-eagled leaps, face to the floor and then roll.

This company is hot. This piece might have started as a tongue-in-cheek critique, as suggested by the title, but the dancing no longer relies on quotation for effect. The virtuosic physical material has a thrilling kinaesthetic and expressive logic that I found riveting.

–

Birdbrain, ADT, conceived/directed by/choreography Garry Stewart, dancers from Thwack and ADT: Anton, Craig Bary, Kristina Chan, Roland Cox, Antony Hamilton, Tanja Liedtke, Lina Limosani, Larissa McGowan, Fiona Malone, Matthew Morris, Craig Procter, The Playhouse, Adelaide, June 29

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 37

© Anne Thompson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

pvi collective, trigger happy: private lives public spaces

Following on closely from 3 weeks of research and development—and new work for PICA’s Putting on an Act and a curated exhibition Tactical Intervention Strategies—I spoke with PVI (Performance, Video and Installation) Collective directors, Kelli McCluskey and Steve Bull, and performers Katherine Neylon, James McCluskey and Chris Williams, about humiliation, discretion, paranoia and behavioural

analysis software.

Your work a watching brief, for Tactical Intervention Strategies at PICA, challenges the gallery visitor not only to perform certain potentially embarrassing tasks in public, but to invite themselves to be watched closely by outdoor surveillance equipment. Did you expect anyone to take the bait?

KM We really didn’t think that people would take the costumes out on the opening night of TIS. We were almost daring the audience to follow through with the instructions, and they did. They have to choose a briefcase, a character, and call a number. They’re given coded instructions for the kinds of gestures they’re expected to perform in the cultural centre outside the gallery, like doing something at the traffic lights or covering their faces.

SB After they’ve received this message they have to look at the dictionary that’s posted near the phone to decipher it. The code steers the telephone conversation away from any potentially loaded ‘key words.’

KM What we try to do is to stretch the boundaries of a given space, then network it back into a performance. For our 3-week research and development at the Blue Room theatre we wanted to focus on surveillance technologies. Our work for TIS specifically came as a response to this report we had found. Do you know that Australia is the second largest distributor of CCTV systems in the world?

That doesn’t surprise me; what’s the first, the US?

KM No it’s actually the UK. They’re incredibly paranoid. The technology that’s available is astounding, like behavioural analysis and facial recognition software.

This leads on from your performance deadspace that referred to telephone monitoring practices.

KM In deadspace we were investigating what constitutes a subversive word, and how language can be misinterpreted. Now we’re looking at gestures and the ways they can be misinterpreted by these cameras, equipped with behavioural analysis software. Something as simple as masking your face with your hands, smoking a fag or scratching yourself fits into surveillance criteria.

KN We discovered that you could avoid being watched by wearing a uniform.

Where did you find the surveillance report?

KM It came out of the UK and basically questioned the successes and failures of CCTV, finding that it hadn’t really been fully investigated. So an independent report came up with some really interesting facts about the people watching CCTV monitors, and how untrained they were. They brought their own prejudices to the interpretation of events, mostly linked to cultural stereotypes. So they would look at young people, or ethnic minorities, or just for the hell of it they’d pick-up on a good-looking woman and follow her around.

Like the Burswood Casino surveillance report.

JM We were also looking at codes used on CB radio and filmic languages.

The extent of your research is broad; what performance outcomes did you expect to achieve through this R&D process?

KM We wanted the guys working on the project with us to perform surveillance tasks on the general public in public places. This is how trigger happy: private lives public spaces was developed. We set-up a workshop space with a scanner and a CB transceiver for walkie-talkies. We could hear them communicate with each other, and we gave them tasks each day to track somebody making certain gestures.

KN We also used our own prejudices, like the CCTV operators, to pick out the people that we would follow.

KM The guys have to try to ‘blend in’ and be discrete which is quite difficult, because the walkie-talkies don’t quite look like mobile phones, so we finally got them some hands-free devices.

SB They walked along speaking a very odd language, and anyone who clued into it gave them strange looks.

KN What we found was that everybody else noticed what we were doing, except for the person we were following.

JM It changes the way that you associate yourself with a space. As a watcher, as soon as you start reporting on people, you become really distanced.

SB It’s interesting how the coded language makes what you’re describing much more loaded. It’s pretty banal, but somebody walking to a bus stop becomes an incredibly over the top performance. So we’ve taken on the idea of Kate, Chris and James blending in in Northbridge, along with the notion that CCTV cameras ignore anyone in uniform. We’re having them dressed up as Santa Claus.

CW Yeah, you just blend in.

So how does the dynamic operate between Kelli and Steve as directors and you Kate, Chris and James as players? Do they give orders that you have to follow? How much personal choice or input do you have?

CW I find the work really satisfying because you’re constantly challenged to do things that you wouldn’t normally choose to do. The first time we started to workshop with Kelli and Steve they made us sing and dance, like “here’s some music, just dance in front of us.” It was humiliating, but you step over that.

SB So Santa Claus isn’t a problem.

JM Because Kelli and Steve work with so many different layers of research, it seemed like we were performing a lot of disassociated tasks which was exhausting, or else talking for hours to extract information from each other. Then, when everything came together with certain elements filtered-out, we would start to hear our own lines coming back at us. Since our first project, we’ve become a lot more involved in their processes, instead of sitting back and being meat-puppets.

CW Also, quite often we’re not aware of everything that’s going on in a performance. I can’t see everything, but Kelly and Steve have the eyes to see.

SB That’s the job.

PVI collective: a watching brief, showing in Tactical Intervention Strategies, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, July 4; trigger happy: private lives public spaces + Putting on an Act, PICA, July 13. PVI are currently in residency at The Performance Space, Sydney, July 30 – August 20

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 38

© Bec Dean; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

John Meade, Propulsion

John Meade’s Propulsion integrates the enigmatic moment of perception by revealing the body as a permeable surface. A video installation of the senses, the first thing to penetrate you is sound. To be precise, it is the sound of a distant piano motif which could be Satie or some other early 20th century romantic—but which is actually a looped series of Glen Gould variations, isolated and slowed down by emerging Melbourne artist, Jophes Flemming. The sound immediately installs us in a certain psychosomatic state—namely, melancholia—prior to the viewing of the video imagery.

Emerging from the darkened gallery space, 2 large perspex panels suspended from the ceiling emit bright, almost hallucinatory images. They face one another as floating apparitions that we can walk around and immerse ourselves in. Their ever-flowing images present 2 carefully staged, hyperreal scenes. One shows a man on a sparkling motorcycle, superimposed over a moving background of saturated green countryside and blue sky (as well as a mass of electricity and telephone wires). With no helmet or gloves, and with exposed hairy arms, he appears naked, or at least vulnerable. While he stares ahead for the duration of the video loop, our attention is drawn to his organ of sight, exaggerated by makeup or a certain camp tenderness. Occasionally we see a close up of his eyes, in profile. Eventually, a tear forms, and as it rolls off his cheek it unexpectedly transmutes into an ephemeral explosion—a subtle jouissance, rendered as an animated firework-like white spray.

The screen opposite depicts an equally dream-like configuration of time and space, with even less narrative drive. Another man flies through the air, his body outstretched horizontally, desperately struggling to maintain his position by clutching on to 2 handrails. His billowing T-shirt reveals a toned stomach and arms, but essentially these are ordinary, fragile bodies on display—actively passive. The imagery and music combine to produce a theatrical space, a potential bond of socialisation which dramatises the affective relation between the bodies and the viewer. A strange longing results, somehow nostalgic, overflowing the perpetual present of the video imagery.

Meade’s work—his sculptural objects and images—can be understood as meditations on the capacities of our gaze and of our bodies, conceived within the limits of human finitude. Inevitably, his art returns us to the idea and operation of the unconscious—desire, pleasure, repression and drives. Propulsion solicits our identifications in a subjective experience of duration. We are seduced towards a sense of meaning, figured as an excess. The work leaves us both melancholic and affirms a positive intensity, elegantly figuring the body as a source of desire and fear, sadness and joy, agent of the self to itself and to the outside world.

Propulsion, John Meade, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, June 8 – July 15. This exhibition originally appeared at the Art Gallery of NSW.

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 38

© Daniel Palmer; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Chris Drummond

Chris Drummond’s directing credits include Play with Repeats by Martin Crimp, Slum Clearance by Vaclav Havel, and Wreckage by Hilary Bell. In his successful production of Yasmina Reza’s Art for the State Theatre Company of South Australia, and the continuing adaptation with playwright Susan Rogers of Robert Dessaix’s Night Letters, South Australian theatre director Chris Drummond is developing an expansive style that celebrates performance as an individual and collective act of conscience.

What are you drawn to in theatre?

Theatre that seeks to be expansive both within itself and within its audience. As an audience member I want to laugh and cry and scream and be delighted and disturbed, whatever it takes to really feel alive. I want it acknowledged that I am present there, that I have a brain and life experience and a whole lot of other baggage as well.

In work, I am drawn to theatre artists who bring with them an understanding of their craft and an essential lack of ego, a genuine naiveté about how to move forward, unfailing rigorousness, fearlessness and above all, a sense of delight in their own and other’s playfulness.

If art is “the balance between order and chaos” where’s your personal fulcrum? How do you work at achieving that balance?

I try not to define the specific outcomes of my work. I have a sense of where we are going but try to have the courage to allow every possibility to have a genuine chance of taking seed. In any situation I try to find the most realistic boundaries within which we can encourage creative choice as a precursor to ordering the rhythms, images and tempo of a piece. I’m equating ‘order’ with the rational and ‘chaos’ with the intuitive. If we only ‘think up’ images and stories, then we will only be communicating that which we already know, which is very boring. If we leave everything open to intuition then we end up with a meaningless mess. So we need both.

How would you describe your directorial vision and style?

At the moment I’m still interested in trying to work out how best to work with actors. I am in a very particular period of development, beginning to understand how not to control everything and yet still bring focus to the work. It’s a very long, very slow learning curve. I guess my desire is to create theatre that has true vitality. I love working with all the elements of the theatre but to begin and end with me creating fantastic images doesn’t feel enough. I am definitely not interested in being an auteur. I am sure I have certain ‘fingerprints’ in terms of my aesthetic but I try to respond afresh to each project in terms of the text, the cast or the social context.

How is the adaptation of Night Letters going?

It’s going very well! Susan Rogers (playwright) and I have been working on this since early 2000 and we hope to have a full draft by mid 2002, and looking towards a production in 2003 or thereabouts. It’s a huge undertaking. Thank God for Rosalba Clemente and STCSA’s Faulding On Site Theatre Lab. Their belief in this project has given Susan and me the resources and the time which is so necessary if we are to succeed in adapting this book with all the complexity required to realise its full potential.

What are some of the challenges in adapting a work of this nature?

In the first place you have to have a very clear reason about why you’re even doing it. What is the point of transforming a work of art from one medium into another? In the case of an adaptation, the new work has to have its own purpose, both in its own right and in relation to the original entity.

Night Letters talks about a very special quality of experience in which a dying man has burrowed down into the essence of his situation and found meaning for himself in an age where meaning has lost its, well, meaning! I believe it also communicates something very profound about humanity’s relationship to nature and something new about Australia’s identity to the rest of the world.

Adapting Night Letters came about because I wanted to access the meaning in the book experimentally. I wanted to understand it at a gut level. The internal journey towards one’s death is such an individual experience and yet the experience of grief is a collective one. It appeared to me that re-creating Dessaix’s internal journey within the community of the theatre might allow insight into both spheres of experience. Night Letters is also about existing within the moment. The theatrical medium could become a transcendent metaphor for that very theme rather than it simply being realised theatrically.

Practically, there are huge challenges in adapting this work. Night Letters does not have a traditional narrative structure and many of the characters have not been fleshed out in a dramatic sense. The fact that this work is semi-autobiographical presents its own set of unique issues. Robert has utterly floored Susan and me with his fearless generosity and his commitment to allowing us our essential creative freedom. He has made himself available in a vast array of senses and has asked for no control in return. The genuineness of his personal courage and honesty represents the very essence of what makes Night Letters such a unique work.

What would you like to see in new Australian theatre in the future?

Personally I am conscious of my own political apathy. I would love to see more theatre artists working beyond their own creative concerns and finding inspiration in the fabric of our society. Within this I would love to see a fearless pursuit of excellence and a holistic approach to all that is unique about the theatrical medium.

Ultimately, I would love to see those artists who actually have ideas being realistically supported to bring their vision to the fullest fruition.

In September Chris Drummond is heading to Europe for further research on Night Letters before returning to direct graduating students from Adelaide’s Centre for Performing Arts.

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 30

© Dickon Oxenburgh; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Volcano, Maria Miranda & Norie Newmark

A simply lit trunk sits in a corner. It’s reminiscent of something you might find washed up on a beach, or pushed aside by a lava flow. Faded, but still intact, it has a history. It may well have been the thing you grabbed, stuffing it full of clothes as you tore out the door, just before the volcano erupted. Maybe you dropped it, and by a twist of fate, as you were incinerated, it survived, the slow moving lava taking a different path from where it was hastily flung.

The shape of the island is strange, nearly circular—a mountain like a ring in the sea.

While the experience of Volcano has a similar, touching appeal to wandering the ruins of Pompeii in Italy, there’s also something gently humorous about Maria Miranda and Norie Neumark’s new installation piece, on the island of Stromboli, at Sydney’s Artspace.

The debris spilling from the trunk is not the legs of stockings and arms of sweaters, but the substance of the volcano itself, remembered by the trunk and now transformed as memories often are. Through technological aids we are given a trunk’s memory of the volcano…And because the trunk has seen many lives, so the memories are from many different times.

The trunk is lit by a spot of yellow. From it spews a mass of tangled cables, a lava flow of plastic and wiring, which lead to a collection of lava rocks—in the form of computer monitors, out of which spill and shake various images.

‘What!’ I shouted. ‘Are we being taken up in an eruption? Our fate has flung us here among burning lavas, molten rocks, boiling waters, and all kinds of volcanic matter; we are going to be pitched out…vomited, spit out high into the air…in the midst of a towering rush of smoke and flames; and it is the best thing that could happen to us. Shot out of a volcano at last!

Jules Verne, Journey to the Centre of the Earth

Stones are falling around your ears—they sound like rain on a tin roof, in Neumark’s accompanying sound design. At strategic points around the monitors the roar of the flow has come down through time, down through the wires, as a static hiss, in and out of which fade voices—the gabble and chatter of people and bodies before, during, after. They’re speaking in the Stromboli dialect, something like a siren’s call, urging you closer, drawing you through the rubble, to tease out the meanings. It’s a trick—by now they have nothing particular to say, but to cry out their grief and love, inarticulate but still genuine, over time.

It seems that Hephaestus, being displeased one day, had taken the island of Thira in his hand and thrown it some distance, like a stone.

Maria Miranda has manipulated a series of static pictures, playing with the moment when you’re really not sure whether or not the earth has moved, if the trembling you’re feeling is lust or fear.