Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

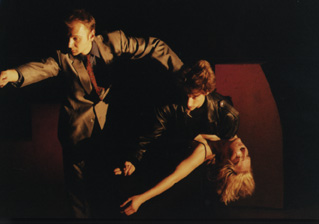

The tango is a powerful, popular form of dance and music from Argentina that has long crossed the high-low art divide, achieving an entirely new level of cultural intensity and global reach in the 90s. Progressive jazz producer Kip Hanrahan played a key role, recording Astor Piazolla and ensemble on the Nonesuch label in the 80s with a rare vivdness and depth of sound, capturing the composer’s rich theatricality. The likes of Daniel Barenboim and Gidon Kremer contributed CDs from the classical end of the spectrum in recent years and Piazolla’s orchestral works and opera have enjoyed a quieter if still significant posthumous profile. Sally Potter’s soggy, mid-life crisis movie about the tango added further to the form’s popularity.

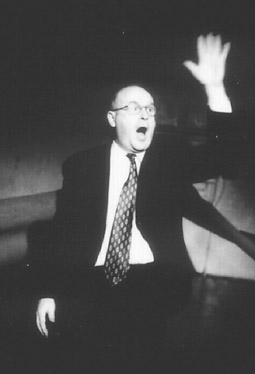

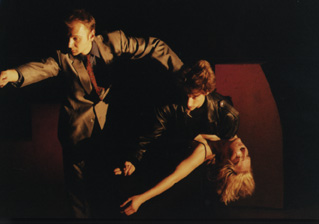

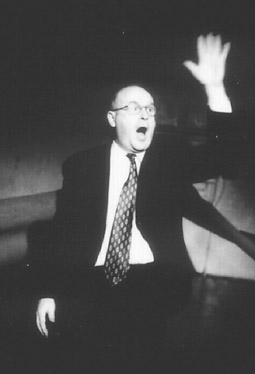

To take on the tango is a brave move and in the hands of Rock’n’Roll Circus and director Yaron Lifschitz, the tango, outside the Piazolla soundtrack, is disappeared–a curious piece of magic. The tango becomes mood, the tango as imaginary rather than real. Look, no dancing.

The globalisation of the tango means that like many a World Music, the form has been uprooted and de-cultured. We’re used to this phenomenon and we’re more often than not forgiving. But Tango, by using the very name, sets up expectations that for some us cannot be met. For others, like the rapturous audience I was part of, it was not an issue.

Put all that aside, which is not easy, and Tango is a pretty good show. Though there are a few other things that I’d like to get out of the way first. After more than 20 years of physical theatre in Australia, here is a company that can’t decide whether it is performing a coherent drama or stringing together routines that require show-bizzy bows. Some of the routines have such a theatrical intensity that it seems a sin to applaud, but the performers are asking for it, so… Others are so mundanely a show of skill that they read like fill. Some are too ambitious–the pre-climax chair-tower scaling is so un-confident that real fear creeps into the audience. The lessons are always the same: know where you’re going, don’t do repertoire for its own sake, do what you can do best and integrate it.

Still, I more than like Tango. The performers look good, they can act, they exude a mix of innocence and brooding intensity that is engaging and when Liftschitz fuses these with sudden spectacular flight and intense physical contact, Tango is gripping.

Tango works, but only moment by moment and not as a coherent vision. The Edward Hopper bar-room narrative it promises peters out leaving the female member of the erstwhile triangle right out of the picture–in fact at the top of a very high pile of chairs. The ending, with Dylan’s “I Shall be Released” is only forgiveable because it is sublimely sung (no tango inflections)–but its fit in the scheme of things seems unmotivated. The set similarly mixes muted Hopper with brightly coloured mats, cancelling out the requisite atmosphere. With so much going for it, Tango could have been helped by taking on a writer, and dancing the tango–it seems the right place for it, its potential for physical display enormous.

Rock’n’Roll Circus, Tango, director Yaron Liftschitz, designer Ralph Myers, lighting Jason Organ, performers Ben Palumbo, Lauri Kilfoyle, Andrew Bright, Davey Sampford; Brisbane Powerhouse, Aug 29-Sept 9

RealTime issue #45 Oct-Nov 2001 pg. web

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

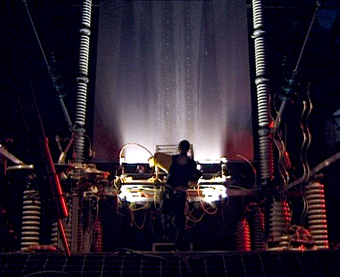

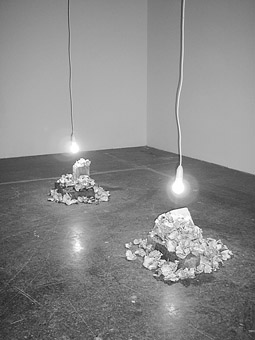

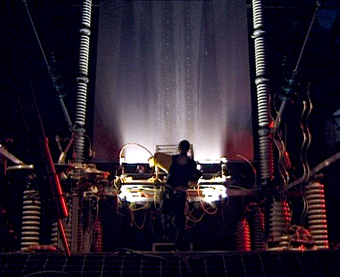

Barry Schwartz & The Arterial Group, ELEKTROSONIC INTERFERENCE

courtesy the artists

Barry Schwartz & The Arterial Group, ELEKTROSONIC INTERFERENCE

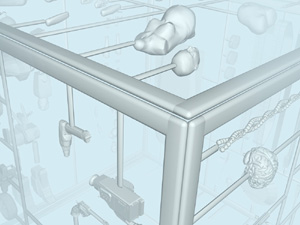

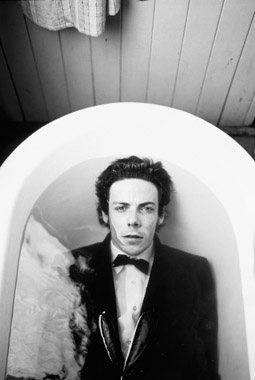

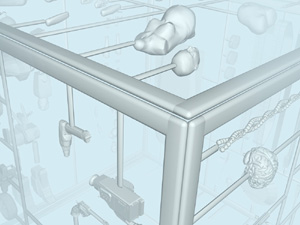

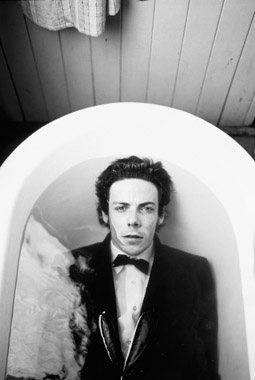

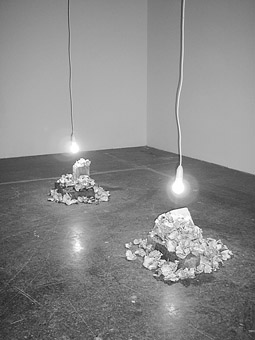

The huge, wide walls of the Brisbane Powerhouse Turbine Hall wrap around us, flooded with images moving slowly, vertically, the effect is vertiginous. In the centre of the hall digital images play on a large screen above a collection of bright metal sculptures standing just above water. A projection on another wall picks up artists and technicians as they move purposefully about the space. A choir appears on various levels delivering text in song, chatter, chirp and mutter. The recorded voice of an elderly one-time Powerhouse worker, Max Ham, intones the fun of working life (including his workers’ skiffle group, The 5 Kilowatts) and the horrors of a building then awash with asbestos and machines that chopped off fingers and limbs. A long row of artists and technicians sit at a bank of computers, lighting and sound desks. Centre stage is the American Barry Schwartz (electro-mechanical structures, RT#44) and, constellating about him, the Belgian Bastiaan Maris (chemo-acoustic installations), the Brisbane artists Andrew Kettle (sound) and Keith Armstrong (visual production) and others in their coveralls.

As the installation-performance slowly unfolds over the hour, sparks begin to fly, shooting out of the top of a condensor accompanied by shards of sound. Schwartz activates the sculptures. The stroking of a large metal disk yields eerily primal metallic groans. The artist lowers what looks like a huge, smoking turntable arm onto the same disk unleashing pure, massive cymbal-like tones. The pace of the work accelerates, the tone growing more ominous, the choir heralding something apocalyptic, Ham telling of death by electric shocks, death by asbestosis. Schwartz dons long, protective, insulated yellow sleeves and big gloves, dips them into water and turns to the big screen, now streaming with water. He strikes, igniting the water with balls of electricity that travel up and fade, as others climb higher and higher, each stroke ringing out like chorded bells heralding the end of time. Unlike the workers in the Powerhouse who were electrocuted and resuscitated or died, Schwartz is safe, transforming danger into awesome, if grim beauty.

In a key moment, a wiry tree sculpture (realised exquisitely as well in a digital version onscreen) is picked up, electrified and inverted by Schwartz—“The possibilities for radical enchantment are signified by an inverted wattle tree—resembling the Jewish inverted tree of life—which was part of the ceremonial initiation of young [Indigenous] men and was called kakka, meaning ‘something wonderful’” (program note).

To see a living installation on such a scale and of such ambition as Elektrosonic Interference in Australia is a very rare experience. Limited funds, short development periods, inadequate venues and scarce technical resources usually gravitate against the realisation of artistic visions of this kind. However, Brisbane’s Arterial Group have managed to find the collaborators, the financial support, goodwill and the venue with which to realise a major multimedia creation.

It’s hard to do justice to the scale of the work. There are other resonating layers. The site-specific response to the Powerhouse (built in the 20s to power Brisbane’s tram fleet) also includes the site’s environmental and Indigenous past, primarily found in writer Douglas Leonard’s text, scored by composer Stephen Leek and performed by The Australian Voices, and visually echoed in the projections on the Powerhouse walls, spelling out ‘Terra Nullius’. In antithesis to this oppressive notion, Leonard uses another local Indigenous word, Kore, denoting wonder. The text and composition, Kore, includes a litany of environmental riches:

eastern water dragon/saw-shelled tortoise/swamp snake/broad-palmed rocket frog/clicking froglet/echidna/chocolate bat/fawn-footed melomys/ferny azolla/spikerush grogbit/golden-lined whiting/bull rout/pacific-eyed rainbow fish/freshwater catfish/azure kingfisher/rainbow lorikeet/red-legged pademelon/rufous bettong sugar glider

These are spoken against sung lines: “They are coming back, the weeping bottle-brush, the broad-leafed apple, giant ironwood, white bean, black ti-tree, native holly, axe-handle wood…Kore, Kore, Kore, they are coming back,” and an invocation of Nguril, the Creator of the river, plains and creeks of the region.

Barry Schwartz & The Arterial Group, ELEKTROSONIC INTERFERENCE

courtesy the artists

Barry Schwartz & The Arterial Group, ELEKTROSONIC INTERFERENCE

Leonard has also constructed the sound text drawing on the oral histories of the multicultural Powerhouse workers, revealed in their terse natural poetry, their detached accounts of workplace accidents and management negligence, recollections of the Powerhouse cat, a river overflowing with fish, and pride in The 5 Kilowatts.

The cinematic dimension to the work is enveloping, entailing whole walls and screens, recorded and live projections. It provides a rich theatre of simultaneity, of choosing where to direct one’s gaze as the work unfolds.

For a creation of such ambition and textural complexity it’s not surprising that it didn’t always work or please everyone. Opening night appeared to be seriously under-rehearsed. For 20 minutes it looked like it wasn’t working at all, although there was a lot of flurried techy movement about the stage. The choir, even when miked, were often hard to hear above the soundtrack and the talkative audience—but when they were heard in their scored whispering, muttering, coughing and singing, they excelled. Lighting ranged from spectacular to inadequate—Schwartz was seriously underlit at crucial moments. A show that sets up such huge theatrical expectations has to go some way towards meeting them, even if it is an installation with its roots in the anti-theatrics of performance art.

For many who found the first 40 minutes sluggish and unfocused, all was forgiven in the last 20. For others the work was always unwieldy—too many layers, too many collaborators. Some had seen Schwartz perform overseas, describing his work as more complete, more coherent when more or less on his own. One viewer described him as a showman out of context in the preoccupations of his collaborators. Of course, the line between showman and artist is often a thin one in contemporary performance, and certainly Schwartz’s offering in Elektrosonic Interference was not as spectacular as some had hoped. Its beauty was rare and idiosyncratic and the meshing of water, electrical flow and spark and sound was often remarkable. But for the audience the work did require a special patience and attention under sometimes difficult circumstances—awkward production values, tiny program notes, an hour or more of standing, often crowded viewing. Apparently, subsequent performances were more focused and more satisfying.

Elektrosonic Interference needs to be rewarded for more than ambition. Australia can be a punishing place to work, off-the-cuff dismissal is de rigeur, failure to recognise achievement and potential is common, though a little less brutal than it has been. Works on the scale of Arterial’s vision (involving more than 70 artists, technicians, singers, volunteers) remain rare and are usually the province of overseas artists in shows we hear about, but rarely if ever see. The collaboration with Schwartz and Maris offered an opportunity to embark on such a venture. It is to be hoped that the Australian collaborators will carry this unique experience forward into new, equally ambitious projects.

It has been wearying in recent decades to see theatre company casts whittled down, performance ensembles disappear, feature films strangled by small budgets. No wonder Theft of Sita and Cloudstreet have been greeted so passionately—scale is integral to their power. Brisbane’s ELISION ensemble is another company working with installation as performance and across artforms. transmisi was performed in the Tennyson Powerhouse in 1999 for the Asia Pacific Triennial, Opening of the Mouth in the Midland Railway Workshop for the 1997 Perth Festival. IHOS Opera too operate on a rarely seen scale. Big is not always best, but unless Australian artists seek to experiment with scale, and are empowered to do so, we’ll continue to feel that something is missing.

Arterial Group-Barry Schwartz Collaboration, Elektrosonic Interference, director/performance artist Barry Schwartz; sculpture workshop/technical director Bastiaan Maris; concept development Douglas Leonard, Barry Schwartz, Therese Nolan-Brown; Turbine Hall, Brisbane Powerhouse, Sept 6-8

RealTime issue #45 Oct-Nov 2001 pg. 29

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

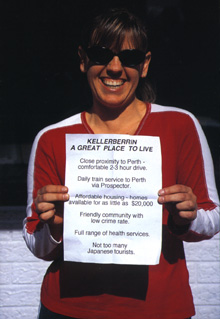

Rockhampton Gardens Symphony

Mitchell Gallery & Studio

Rockhampton Gardens Symphony

In Brisbane

For 10 music-filled days I saw concerts and wrote and edited in the Brisbane Powerhouse, site for much of Lyndon Terracini’s 2001 Queensland Biennial Festival of Music (see interview, RT#43). It was an intense, always enjoyable and often revelatory experience—not only of unique music expertly played, but also of an artistic community celebrating what it loves to do and finding time to spend together. With Assistant Editor Jenny Speed and a team of Brisbane writers, most of them artists, RealTime produced reviews online and distributed print copies in the Powerhouse. Also now on our website are articles on the Biennial’s International Critics’ Symposium. A small selection from our QBFM articles, and excerpts from others, appear on these pages along with a list of all the reviews online.

Beyond the Powerhouse, the festival made Brisbane appearances at Southbank (a stunning, standing ovation-Turangalila-symphonie), City Hall (Anumadutchi, the Dutch percussion group with African guests ), Customs House (ELISION ensemble’s Spirit Weapons), St Mary’s (a packed out Critical Mass for the homeless and a rivetting Song Company recital) and, again at Southbank, the Stuart Series, an excellent set of twilight concerts working out the new Stuart grand piano (Lisa Moore, Paul Grabowsky and Michael Kieran Harvey brilliantly showcasing the instrument).

Across Queensland

Concerts were staged in Mackay, Townsville and Cooroy, and in Barcaldine, Rockhampton and Logan City workshops and events brought artists and communities together. In Logan City, in Queensland’s Bible belt, Terracini successfully introduced Sydney’s Cafe at the Gate of Salvation (in performance and workshop) and the Indigenous singer Rochelle Watson to an audience of thousands in a 7 hour celebration of song including some wildly received Christian rock’n’roll.

Terracini wanted to hold a festival that people in regional Queensland could feel connected to. He’s particularly proud the way participation worked so well in the remote western town of Barcaldine (home to the Tree of Knowledge, site of the famous 1891 shearer’s strike meetings and birthplace of the Australian Labor Party) where 200 townspeople made and played marimbas. Terracini said, “It’s one of those events where people will say ‘I was there.’ One of the reasons it worked well was because everyone wanted to work together. They came from everywhere in the Barcaldine community. They had a great relationship with Jacinta Foale and Mik Moore. Mik took all the workshops for making the marimbas and Jacinta taught them how to play and wrote a piece called Barcaldee. Now it’s their piece.

“We rehearsed in this huge space, the Workers’ Heritage Centre. I had to mould a huge cast into an ensemble and that happened very quickly in 2 rehearsals. Venáncio Mbande was there from Mozambique and the participants saw the marimbas he’d made and was playing…there was a fantastic bond.

“We closed off the street at 2am, built the stage—the whole thing was a huge logistical exercise. We asked David Thompson, a custodian of the country up there to speak first to welcome us all to country. He’s a descendant of the Aboriginal people who had lived there who were massacred. He’s gone back to live there. He came off stage and burst into tears, an extraordinary moment. Then the Mornington Island song men—freezing, painted up, in their head dresses, doing a terrific job—were singing festival to Queensland. And the sun came up and shone through the branches of the Tree of Knowledge. We’d timed it.

Anumadutchi came on and did the Barcaldine Suite written especially for the festival. The 200 players of the Barcaldine Big Marimba band were seated either side of the stage joining in and 1,500 people in the street were screaming and whistling—a wonderful atmosphere at 7.20 in the morning. And then the Barcaldine Big Marimba played Jacinta’s piece and one by Linsey Pollak, and then they played with Anumadutchi—a fantastic finale. Then we had a barbeque.

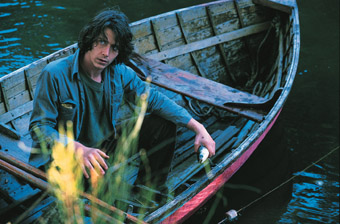

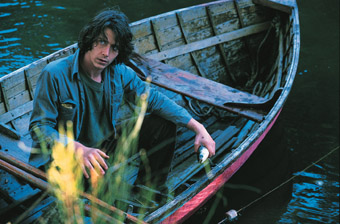

“Then we went on to Rockhampton. The gardens are beautiful. We had a number of stages, again with trees as a theme—a bamboo stage, a banyan stage and a hoop pine stage. Various Rockhampton ensembles played on the smaller stages so people could move through the gardens and hear concerts during the day. Thousands turned out. The Song Company performed on the massive hoop pine stage (we had to be able to get 400 people on it) in a kind of natural amphitheatre. At 4.45 Roland Peelman came on to conduct the premiere of Elena Kats-Chernin’s Rockhampton Gardens Symphony, a half hour choral symphony with the Rockhampton Concert Orchestra, marimba band, the City Brass Band, drum kit, 2 choirs and a tenor soloist from Rockhampton, Christopher Saunders—and a text by Queensland poet Mark Svendsen.

“At the end 5,000 people were on their feet. You don’t expect this in a garden. There was so much applause they had to play the last movement again and then the applause still went on. The players who were originally bemused by the music were now enamoured of it and they said would like to do more as a change from The Sound of Music. Normally you’d never get a standing ovation for this kind of work, but because it was theirs they were responding to new music, a new work, a world premiere. The town councillors took a risk on it and it paid off. The premiere got on to the front page of the Rockhampton Bulletin which called called it ‘a thriller of a symphony.’

“The contrast with the Federal government’s $200,000 Really Useful Company tour of Grease is disgraceful. If (Minister for the Arts) Richard Alston had seen these concerts…The lack of knowledge about what is happening to art and culture in regional Australia is appalling. If the Really Useful Company had to apply to the Australia Council for funding, they would never have qualified under the Council’s usual conditions.”

Terracini’s Biennial looked a success, even at its half way point when we met to talk. He was excited not only by the positive community response across Queensland, the standing ovations (“a new phenomenon here”), but also because, even though he wasn’t getting to sing, directing the festival “was like doing a show.” Despite the rather grim prospects for new music delineated in the accompanying International Critic’s Symposium, the festival’s audiences suggested a brighter picture. Though, as we all know, a festival can succeed where the year-round programming of new music can fail to engender anything other than small audiences comprising the usual appreciative suspects. Even so, Terracini’s adroit programming managed to satisfy diverse audiences without compromising the quality of the work, and suggests possible ways forward. My greatest pleasure came from being able to experience Messiaen’s Turangalîla-symphonie and new or rarely heard works performed by Lisa Moore, Michael Kieran Harvey, the Australian Art Orchestra, Topology, ELISION ensemble and Orkest de Volharding. Let’s hope that in 2003, the Biennial will return with Terracini again at the helm.

RealTime issue #45 Oct-Nov 2001 pg. 31

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Anumadutchi

photo courtesy QBFM

Anumadutchi

Loops & Topology: Airwaves

Brisbane Powerhouse, July 24

Seventy-five minutes of radio archive history. FM clarity, AM telephone bandwidth. Old timers scraped out of mouldy shellac grooves. Naïve racists on rusty tapes. Databases of dickheads, geniuses, opportunists, and self-promoters. Arranged in reverse chronology. From now to then, from us to them, a salad of history where before White Australia was Belsen, before Clinton was Ghandi, where men had to walk on the Moon before Cathy could run that great 400. But the vocal text isn’t about cheap moralisms. It’s stochastic history not storyboard history.

And over and under the ‘Voice Portraits’ plays the music. A series of episodes and program pieces to reinforce or foil the text. George Bush whingeing about Saddam and damn that’s some funky bass. The Goons bubble up and Max Geldray lives again. Dad and Dave ride on the back of Click Go the Shears. Sometimes the musical quotes were right there on the staves; cut and paste, a straight up arrangement. But most times the references were oblique, witty, laugh out loud nostalgia. Not that the music was all quotes and ironic degree by a long shot.

…At the beginning I think of a happy John Zorn, then associations disappear pretty quickly as I get caught up in the individual personality of the piece. The sound is excellent, right volume, right balance on the instruments. The performers play to a click track, they’ve each got headphones on. I’m not surprised, the music’s often complex, the timing always precise. Strange, abstract rhythms suddenly synch perfectly to all time favourites. ‘Now is the time.’ ‘I have a dream.’ ‘Turn on, tune in and drop out.’

In Airwaves, music effortlessly holds the mirror to the musicality of language. And it is not just that either. Airwaves is a big piece, chockerblock, a must-have for the collection when the CD comes out. Play it entire or dip in and out. Don’t play it in the car while driving. Too distracting.

Greg Hooper

Karaikudi R Mani, Sruthi Laya Ensemble

photo Kate Gollings

Karaikudi R Mani, Sruthi Laya Ensemble

Australian Art Orchestra: Into the Fire

Brisbane Powerhouse, July 24

The AAO musicians were seated in a semi circle, cradling the Sruthi Laya ensemble, who sat at the very front of the stage. A big band in the round with the karnatic musicians in the solo spot. Adrian Sheriff and Sri Mani’s title track from the Into the Fire CD grew out of their 1996 collaboration in India and later in Adelaide. One of the real difficulties in cross-cultural composition is the need to find ways of overlapping the styles, and also of working at a level of depth and respect within the 2 cultures. The composers have taken the basic material of the raag, the karnatik scale, and developed an exhilarating, enthralling performance. With the brilliance and accuracy of some of the best classical and jazz players in Australia flying through the melodic phrases, sparse but warm harmonic material, and the total focus and control of the Indian master musicians, the audience was captivated. At an emotional level I found the performance of this composition deeply satisfying. If there is a definitive list of “classic” cross-cultural compositions and performances, then Into the Fire is definitely on it for me. …Just as we reached the crescendo, the AAO put down their instruments and sat back to listen to the Sruthi Laya. For 20 minutes we were mesmerised by the brilliance and accuracy of their playing. Then, as if this wasn’t enough, the AAO members moved back into position and with the mighty clap of Paul Grabowsky’s guiding hands the orchestra joined in again, thundering through to the coda. Beautiful stuff.

Jim Chapman

The Queensland Orchestra: Turangalîla-symphonie

The Concert Hall, QPAC, July 21

…The end result was both richly textured and wonderfully playful, completely enveloping the audience in the composer’s unique and often unpredictable sound-world. Michael Kieran Harvey particularly seemed to revel in the demanding piano lines. At times he pushed the brassy Stuart & Sons instrument to compete with the full orchestra while at others he interjected with Messiaen’s trademark snatches of birdsong (most prominent in the languorous sixth movement). If anything, perhaps the performance erred more on the raw dynamic side, losing some of the carefully layered harmonies and elements in the overall wash of sound. Some of the blame for this, however, could be levelled at the acoustics of the Concert Hall which at times lacked the clarity required for such a work.

Valérie Hartmann-Claverie’s Ondes Martenot had no such problems with the hall or competition from the orchestra—its pure sound managed to cut through everything. Messiaen gives the main love theme to this instrument and uses its soaring glissando effects to evoke an otherworldly and transcendent space…Hartmann-Claverie’s delicate use of vibrato layered with slow violins in the restrained sixth movement helped produce a haunting crystalline sound that beckoned the audience to gaze into the starry face of eternity while Kieran Harvey’s piano called us back with the earthbound song of birds. It is with this type of beautiful and essentially melancholic moment that Messiaen strives to express the inexpressible and to give us a space to experience a time outside of time. For a moment during the movement I closed my eyes and dreamed of the stained-glass light of Sainte Chappelle which so inspired Messiaen’s musical language.

…In the final acts of the work [conductor] de Leeuw pulled out all stops and let loose the rawness of Messiaen’s orchestration with the tuned percussion and brass sections particularly working frantically to deliver. This had such an overwhelming effect that by the end of the symphony’s epic 75 minutes most of the audience rose enthusiastically for a standing ovation. The overall effect was inspiring and revealed a viscerality and feeling that I had not encountered in recorded versions of Messiaen’s oeuvre. Though this performance may not stand as what some may call a definitive interpretation of the Turangalîla-symphonie it was certainly one to be experienced–tutti con brio!

Richard Wilding

Anumadutchi & The Queensland Orchestra

Brisbane City Hall, July 26

…The performers brought the venerable Venáncio on stage and set up the 8 pieces of the timbila. This was a rare treat for a Brisbane audience. This xylophone-like ensemble is something quite special. Venáncio is a Mozambican man who has led a hard life, like many from this region, but who has managed to maintain the tradition of this music nonetheless. The instruments range from the 19 key sanje to the 12 key dibhinda and the amazing 3 key chikulu. Each instrument is played with a 2-handed, complex polyrhythmic pattern. Imagine hearing them played at breakneck speed, and with each of the different instruments playing different parts, once again interlocking. It is a richly textured kaleidophone. The only way you can hear it is to let it sink into your mind and to focus on any of the hundreds of possible patterns that can be heard. Visually, the playing is exciting, especially watching the chikulu players hurling themselves at the 3 log sized keys of their instruments. Venáncio is an unbelievable player. The counter melodies that he was playing were so deep in the cracks of the other patterns that it’s hard to imagine that anyone else could play them. He is probably the best timbila player in the world. He is regarded as such in Southern Africa, and his performance confirms this.

Jim Chapman

ELISION: Spirit Weapons

Customs House, Brisbane, July 22

…Since its inception, ELISION has excelled in the production of a brilliant palette of sound colours. It is this range which leads me to think in gastronomic terms—the sounds are so physical one can almost taste them. Michael Smetanin’s Vault has this quality, with its gorgeously crystalline sounds made by spiky high notes on the harp combined with viola harmonics, metallic percussion and rushing piccolo runs, along with bottom-register bass clarinet rumblings. The music’s physicality is also expressed in body-based rhythms, played with James Brown tightness by the ensemble.

…Anthony Burr’s robust performance style (on contrabass clarinet) was used to great advantage in an extraordinary new work by Liza Lim. A new piece by Lim is always an event, and she continues to surprise. Spirit Weapons consists of 2 short pieces drawn from Machine for Contacting the Dead. Lim composed this large work for Paris’ Ensemble Intercontemporain on the occasion of an exhibition of newly unearthed 2,400-year-old Chinese musical instruments. She resisted the obvious choice of composing for replicas of these instruments and instead invented ritualistic music referring to another object found in the tomb—a triple-daggered halberd (cutting/stabbing weapon). Three percussionists, perhaps reflecting the 3 daggers, form a “meta-instrument” with the contrabass clarinetist. This is very serious music, a “radiation of ancient wood and metal”, but I can’t help imagining a sense of fun, perhaps even mischief, in Lim’s use of instruments.

Like Gavin Bryars’ Sinking of the Titanic, this is music imagined as happening under water, and the Leviathan sound of the contrabass clarinet is a perfect fit. The piece is a “slowed down, submarine version” of the other component of Spirit Weapons, a cello solo, played with miraculous fluency by Rosanne Hunt, in which harmonic overtones continually emerge from sliding notes and the dark sounds of loosened strings.

Robert Davidson

Orkest de Volharding: Andriessen Music Video Program

Brisbane Powerhouse, July 27-29

…Smetanin’s Eternity was musically the most interesting thing on the program, drawing a completely different sound world from the ensemble. Two clarinets were added (Paul Dean and Diana Tolmie, both familiar to Brisbane audiences) which helped even the balance between wind and brass, such that Smetanin was able to play with delicate antiphonal choruses of continually shifting homophonic blocks of sound. Paul Dean’s precise microtonal playing in the upper register was particularly impressive. This strange, symmetrical, microtonal minimalism perfectly distilled a sense of the eternal, the otherworldliness with which Smetanin characterizes his feelings when observing the night sky.

Andriessen and Greenaway have had a fruitful artistic partnership since their first successful collaboration on M is for Man, Music and Mozart (1991). I was in some subtle way disturbed by the live performance of Andriessen’s music alongside a screening of the film. The music, and its performance aspect, was ‘foregrounded’ to an extent inconsistent with how I experience music in Greenaway films. For me it upsets the balance, normally so precise and deftly handled, between the swarming fecundity of Greenaway’s foregrounds and the cool, sparse intellectual rigidity of his background structures. Certainly an interesting idea, and worth trying as a festival event, but ultimately a viewing of the original film gives a more complete and balanced representation of Greenaway’s intentions.

Simon Hewett

Lisa Moore – The Stuart Series

Auditorium, Queensland Cultural Centre, July 27

American composer Martin Bresnick’s For the Sexes: The Gates of Paradise (2001) is a musical take on the William Blake poem and 21 illuminated line engravings of the same name (1818). Directed by Robert Bresnick (the composer’s brother), video artist Leslie Weinberg’s DVD projections consist of simple animations and manipulations of Blake’s black & white and illuminated emblems, enlarged onto an on-stage screen above the piano. Moore’s was both pianist and speaker, this time delivering the entire text of Blake’s poem.

As Moore starts to play the pulsing, determined Prologue, we meet the Lost Traveller, our Everyman companion for this 30 minute piece. He zooms on-screen, cane in hand, and hurriedly moves through time and space while trees pan right, sky pans left. Musically this world is built from colouristic expressive recitative, intersticed with pulsing sections of relatively static harmonies which rock unevenly, restlessly. Moore commands a counterpoint of voice and fingers, sometimes speaking the text to a rhythm; sometimes freer; and sometimes sung, as in the Epilogue’s slow and gentle jig addressed to Satan. …In an era of the supremacy of visual literacy, Bresnick’s collaboration with Weinberg is an example of evolution in action, as is the creation of the Stuart piano. A coherent multi-sensorial work, it invites sustained attention from a far wider audience than ‘pure’ concert music can hope to do.

Lynette Lancini

Michael Kieran Harvey – The Stuart Series

Auditorium, Queensland Cultural Centre July 23

Kieran Harvey explains that Australian composer Laurie Whiffen’s Sonata Mechanical Mirrors is “very loosely based on the Liszt B Sonata” and because it is built on “mirror images of musical cells…is awkward to play.” Well, this might not be Godowsky-does-Chopin, where the melodies at least remain recognisable, but Sonata Mechanical Mirrors is Lisztian in spirit, passionate, even demonic, and an olympian test for player and piano. Great waves of crystalline upper notes cascade against a thundering bass, the Stuart declaring ever greater capacity for volume, its middle range again revealing a bell-like radiance, the whole quaking but without surrender as Kieran Harvey sweeps relentlessly up and down the keyboard, pianist and piano at one. This is an exhausting, cosmos-conjuring 15 minutes. And once again, eruptions are succeeded by calm and afterglow…surrender or grace?

The work that lights up an already enthusiastic audience is Tim Dargaville’s Negra. Kieran Harvey notes its African references, gospel influences, Indian rhythms and distinctive recurrent note row. To my ears this is a great pulsing ragtime fantasia, always hinting at but refusing Joplinesque melody, driven by a pounding, rhythmically familiar left hand style pitted against constellations of upper end trills played at astonishing speed. At times it sounds like a virtuosic cross between Dr John and Jerry Lee Lewis. Is either in the market for a Stuart grand? Kieran Harvey makes a great salesman. In the sublime coda to Negra, as in Andriessen’s Trepidus, as the bottom notes die, the top ones quietly bristle with restless energy…until they too evaporate.

Keith Gallasch

Paul Grabowsky – The Stuart Series

The Auditorium, Queensland Cultural Centre, July 26

…Pivotal to the whole performance was Coal for Cook, dedicated to Ornette Coleman. An audacious nod given the Texan’s key ensemble innovation was the double horn front line quartet with no piano (ie no chordal accompaniment). This in its day freed Coleman’s alto sax into a domain of wild harmonic invention. The alteration of intention and conception was equally profound in the context of Grabowsky’s performance. The tone of the prior pieces, which saw the right hand trying to break free of the constraints imposed by the somewhat repetitive and pendulous walking bass figures, was fractured. This gave way to a much freer section with the pulse merely implied rather than insistently stated and restated and, more than that, feeding on the sheer aggressiveness of the work’s dedicatee. The nicest passage in the piece was perhaps the rapid 2 handed upper register section which mimicked the squally trumpet/alto sax blowing contests of Colemans’ own Prime Time quartet. Rendered on the chimingly bright-toned Stuart piano, these were as coruscations of light on a teeming sea.

Mitch Cunningham

Editor’s Note: RealTime published online reviews during the 2001 QBFM. The full online feature will be re-published in the archive in the future.

RealTime issue #45 Oct-Nov 2001 pg. 31-

© Greg Hooper & Jim Chapman & Richard Wilding & Robert Davidson & Simon Hewett & Lynette Lancini & Mitch Cunningham; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

part of BAM's Next Wave Festival, New York

Welcome to the third of RealTime's annual surveys of developments in Australian new media art. Working the Screen 2001 celebrates the Australian new media artists and works selected for the Brooklyn Academy of Music's (BAM) Next Wave Festival. Now in its 19th year, Next Wave has long had a reputation for innovative programming. This year the festival includes Next Wave Down Under, a month-long celebration of contemporary Australian arts. The BAM website features the work of nine Australian net.artists, provide links to the sites of fourteen new media artists, two net.sound sites, an online documentary on Chunky Move dance company and audio-on-demand broadcasts of works from ABC radio's The Listening Room. This online exhibition has been titled Under_score: Net Art, Sound, and Essays from Australia (www.bam.org/underscore [link no longer active]).

(Download PDF of liftout – 1.4meg – right or control click for download)

RealTime issue #45 Oct-Nov 2001 pg. 2

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

When the federal arts ministers Richard Alston and Peter McGauran announced the film industry assistance package last week, the highly managed launch was similar to the opening of a factory or the naming of a dam the only things missing were the hard hats.

Robert Bolton, Australian Financial Review, September 11

In RT#40 (Dec 2000), we published “UK Arts: the creativity panacea” and in the editorial to RT#44 I raised the issue of the widespread retitling of ‘the arts’ as ‘creative industries’, a move heavily influenced by new arts policies from the UK. These days ideas and policy models spread with the efficiency of viruses. Bolton writes that “it’s understood a cultural policy statement is now cautiously being put together by the Department of Communications, with the intention of launching it during the coming election campaign. This will unite the separate sectors of the arts, formally label them as the “cultural industry” and announce them as a cornerstone of the information economy.” The first signs of the Federal Government taking an unusally strong interest in the arts are evident in the initiation of the Visual Arts Enquiry (successfully prompted by expert strategic moves from Tamara Winikoff and NAVA) and the injection of a much-needed $92.7m into the film and television industry. Bolton quotes Peter McGauran, the junior Federal Arts Minister, in an interview with The Australian Financial Review, as saying “‘We’re not going to peddle the myth that the creative sector is going to become the new grounding of economic innovation,’…But McGauran and Richard Alston, the Minister for Communications, Information Technology and the Arts, have not been immune to current thinking on culture and its impact on the economy.”

The widely promulgated thoughts of Chairman Cutler (friend and advisor to Alston) of the Australia Council have doubtless played a role in these developments. He most certainly has argued that artist innovators can do much for industry and the economy. For this reason RealTime requested an interview with Terry Cutler to ask how the artists benefit from the arts-industry equation. The ensuing discussion with Alessio Cavallaro, Sarah Miller, Linda Wallace and myself makes for fascinating reading.

The promise of improved arts funding looks more than likely. In WA a state budget increase of $7.6 million for the arts and future commitment of $26.5 million has been announced. Its theme, “Rebuilding the Arts”, acknowledged that there is still much more to be done. Arts advocacy group Arts Voice agreed. “The erosion of fiscal resourcing over the past decade has resulted in many organisations being so over-stretched that the energy needed to undertake substantial creative and productive work for the benefit of Western Australians has been sadly diminished.” The budget includes increased support for smaller organisations including the Blue Room Theatre, PICA, Multicultural Arts through Kulcha and the Community Arts Network and Indigenous arts through Yirra Yaakin Noongar Theatre. Arts Voice also welcomes increases in available funds for regional touring for performing, visual and literary arts and a focus on regional access. Sarah Miller, Artistic Director of PICA, cautioned that “these increases will only return organisations to early 1990’s

funding levels.”

Elsewhere, recent Australia Council grant results in New Media Arts, theatre and especially dance left many artists distraught. If new money comes into the Australia Council, and it is vital that it does for this country’s creativity, it should be directed through the Boards to artists and not to special initiatives and one-off programs. If the Federal Government and the Australia Council are putting such store by innovation then they must give it the support it warrants. The In Repertoire guides to exportable Australian performance that RealTime has produced for the Australia Council are proof that innovation here is alive and widespread, often touring internationally, often struggling to survive. They are also evidence that innovation needs to be understood within and without the emerging paradigms of the arts as digital content and cultural industry. While a functional approach to the arts and how they can profit Australia can help justify government expenditure, it could inhibit vision and should be handled with care.

The recent RealTime-Performance Space forum, The Place of the Space, addressing the role of contemporary art spaces and the future of PS, proved a significant event. One hundred participants joined in this 2 hour, open-ended discussion, more in the courtyard afterwards. Eloquent contributions from Nicholas Tsoutas, Sarah Miller, Zane Trow, established and emerging artists, and representatives of other arts venues, provided inspiration and material with which to move forward. The presence of Jennifer Lindsay, the new Deputy Director General of the Arts in NSW, and her participation in the sometimes confronting dialogue made the event even more worthwhile. The transcript of the forum will appear here in early October.

In this edition, we celebrate Australian innovation in new media arts with the publication of our third annual Working the Screen liftout. The artists represented in its pages have been selected by BAM (Brooklyn Academy of Music) for an online exhibition, Under_score, in its Next Wave Down Under program, part of Next Wave 2001, New York. We hope you enjoy Working the Screen and find it a valuable, ongoing resource. As well, in response to endless requests for the names and websites of new media artists, in October we’re opening our New Media Index (NMI) page on our newly addressed, more easily accessed website: www.realtimearts.net. As NMI grows we’ll be including images, reviews and news.

Sad to say, Philip Brophy, our OnScreen Cinesonic genius, has decided, with regret, to leave RealTime. After 5 years of contributing his bi-monthly column despite a heavy teaching load, organising the unique Cinesonic annual sound and cinema conferences (and getting them published), Philip has decided to commit himself to his art, a reminder that he has been the creator of some key Australian films and responsible for the brilliant sound design for the 2000 feature film, Mallboy. Thanks Philip for the use of your finely tuned cinema-going ears for the last 5 years, we’ll seriously miss them. RealTime readers

will seriously miss them.

KG

RealTime issue #45 Oct-Nov 2001 pg. 2

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

In a short burst we witnessed unfathomable horror. And yet we have been denied witnessing others’ horror for years. There is compassion for some and not for others. In a brief instant all the gains of dynamic multiculturalism have been decimated. We are witnessing the lie of justice for all and the surge of globally manufactured racism with the invocation of crusader vengeance and the politicisation of difference.

Synergy no longer surprises me although populist ignorance, and talkback’s propensity for connecting the asylum seekers and terrorists, is astounding. Recent actions have made it acceptable to demonise difference. There has been deplorable lack of leadership in the face of cowardly racist attacks. Perverse government policies are sanctioning these actions while contradicting the basic principles of mainstream multicultural society and the ethics of hospitality. Communities are increasingly fragmenting and segregating and the possibilities for reconciliation seem further away than ever. Critical multiculturalism has become a burning issue—the pervading spectre of our time. As John Rajchman asked, “how can we be ‘at home’ in a world where our identity is not given, our being-together in question, our destiny contingent or uncertain?” Responding to this challenge of dealing with cultural and racial difference in the face of the escalating politics of prejudice will be our greatest test of maintaining a just, hospitable and creative society.

At a time that now seems so much lighter, the July Globalisation + Art + Cultural Difference Conference addressed the renegotiation of multicultural discourses for the arts. Providing a multidisciplinary platform of theory, activism, policy, art and ethics, this was a vital colloquium that investigated the current debates in an international context seeking to come up with global solutions. It combined industrial-strength talk with a serious commitment to providing new models of cross-cultural collaboration in workshopping solutions for future action and understanding. This was the first conference I had been to where there was a healthy, non-hierarchical mix of artists, theorists, activists and policy makers.

Convened by Nikos Papastergiadis, Nicholas Tsoutas and sponsored by the Arts in a Multicultural Australia Policy of the Australia Council, the conference attracted a full-house from around Australia to hear 16 excellent papers and celebrate the launch of Jennifer Rutherford’s terrific book, The Gauche Intruder (Melbourne University Press, 2001), that traces the pressures on Australian morality. There was a large contingent of international guests and inspirational Australian speakers: a wonderfully productive cacophony of accents, positions, backgrounds and colours that denied the need to pin down identity.

Papastergiadis set the tone for the weekend by declaring his boredom with cultural identity and theory. In privileging slapstick theory and a dis-ease with identities he called for a proactive engagement with multiculturalism in private relationships and outside official discourses. A number of speakers reminisced about their search for a way to feel at home when confronted by the ambivalence of the hyphenated-experience that inspired both shame and later empowerment in the possibility of escape from the dominant culture. Ien Ang called this routine, so integral to everyday life, “living in translation.” This is a constant process of negotiation between cultures and communication that denies a notion of ethnic homogeneity since the transformations are never uniform, but are oppositional and always localised. Although I used to think that the evolution into hybridity was a positive thing, Ang among others offered a critique of its redemptive powers, noting that hybridity is based on the destruction of optimistic reclamations of difference since they are always bound by power relations.

This floating existence with its de-centred whiteness and identity-in-process shaped for many a general comfort with being outside obvious belonging. Chinese-Australian artist Lindy Lee explained that despite being told from an early age who she was by how she was viewed, she found it liberating not feeling or being all that Chinese but coming to discover it later. By reinventing things through the ‘bad copy’ her work is a continuing assessment of issues of authenticity. She explained that she was looking at that which is not reproducible while questioning the self as an interweaving of myriad experiences. This is a search for living through a constant dismantling and recreation of new configurations. For artists and theorists, becoming-other of themselves and of the social milieu that they inhabit is essential for sketching alternative modes of belonging and possibilities for multiple translations.

Rasheed Arena, a theorist and artist, spoke about the parallels between modernism and multiculturalism and repercussions on art and social agency. He argued for the positive advancement of society through artists thinking collectively not individually, emphasising the critical role of cultural difference in community-based regeneration projects. Gerardo Mosquera, a curator from Cuba working through Caribbean poetry, spoke of the globetrotting installation artist as an allegory of globalisation—more global for some than for others. Jean Fisher, a writer on contemporary art from England, presented an engaging paper and slide show on the metaphysics of shit and the ethics and agency of the trickster. She argued that globalisation is empowering and that artists should make use of its effects—its excesses and waste in deploying an ethical responsibility. Ghassan Hage discussed transcultural migration and the Lebanese diaspora with a special focus on Venezuela. He identified hope as the greatest inspiration for immigration—the bargaining on increased possibilities of difference, greater security and opportunity away from home.

Marcia Langton and Hetti Perkins spoke in very different ways about Aboriginal art, ownership, innovation, authenticity and discursive marketing restrictions. They challenged a variety of preconceptions about Aboriginal art and its institutionalisation in the Western context that all too often just doesn’t get it, missing the playful and the sexy, living, social processes. Langton addressed the issue of authenticity and the suspicion of innovation in Aboriginal art and culture that, in the service of Western value and values, exploits the marketable yet unreconstructed trope of Stone Age primitivism. She argued that this construction of culture as a highly nostalgic post-imperial souvenired commodity denies Aboriginal responses to innovation, globalisation and most importantly secret-humour business. This reproduces the accusations of nostalgic traditionalism often levelled at multicultural art that denies the possibility of innovation through amalgamation. She argued for the dynamism and multiplicity of Aboriginal art that has an importance outside of the postcolonial white world that only gets the spiritual bongo-bongo and commercial value. Telling a story about the Rover Thomas paintings at the police station at Argyle Diamond mine and their community functions, she emphasised that the real audiences of Aboriginal art see the jokes and the dirty bits in an open-ended engagement. The ‘dirty bits’ are often edited out, but reappear in invented translations or place names. It was heartening to learn that the Australian sacred is covered in faeces, urine and sperm.

Similarly, new technologies have unleashed possibilities for new forms of communities and connections for cultural activism. Ricardo Dominguez, concealed in a black balaclava, presented a stunning autobiographical performance of his coming to digital consciousness through his involvement in the Zapatista networked activism. It was exciting to observe the history of hacktervism and its re-emerging connections with the new activists who have reclaimed the streets as sites of resistance. His comments on the ethics of international digital zapatismo tied in with the questioning of the limits of performance art in Coco Fusco’s reading of her as yet unperformed play, The Incredible Disappearing Woman, about the ‘disappearance’ of assembly line workers on the US-Mexican border. The play was not so much about the excesses of a performance artist recording having sex with the corpse of an unknown woman in a Mexican bordertown (and then attending a retrospective of his ‘censored’ work many years later) but, as Fusco explained, an imaginative investigation into the inequitable modes of cultural exchange and their institutionalisation. The decision to use the body of a Mexican woman to carry out a necrophilic sex act as performance, the actual transactions that enabled the artist to acquire the corpse in Mexico, and the ability to ‘make her disappear’ when she was no longer needed, demonstrated the economic and cultural intricacies of US-Mexican relations. The excellent reading was a potent allegory of the spectacle of inequality and the skewed ethical discourses that emerge in art practice. It emphasised the micro struggles by the gallery attendants to intervene in these processes, challenging us to consider how we as artists intervene with language, relations, practice and policy to achieve greater social and cultural equity.

Multiculturalism was seen as contentious with continuously shifting definitions and without a major all-encompassing theory. Although identified as no longer a minority issue, it appears to be meeting increasing resistance from populist voices claiming that it is an assault on Anglo-Australian culture. Fazal Rizvi argued for working pragmatically within prevailing state ideology and language while keeping the notion of multiculturalism unstable to provide active and radical possibilities.

Strategies for destabilising multiculturalism created 2 opinions for defining the way forward. Some argued for mainstreaming multiculturalism and taking it out of the ghetto while others saw benefits in maintaining its ghettoisation as a pragmatic form for artists working with cultural difference to obtain institutional support. Fusco stressed that theory can and should move beyond segregation of multicultural arts whilst funding arrangements continue to foster and support this area. The realities of Australian society and arts practice were identified as no longer fitting the prevailing policy and funding models. The policy of managerial multiculturalism with its benevolent ‘access and equity’ logic that tolerates but manages difference was dismissed. There was a lack of accord on how to ensure that multicultural and Indigenous cultures—the source of Australia’s greatest vibrancy and creativity, far more so than the nostalgic, antiquated ‘white high arts’—receive appropriate support. Yet this inspired a productive range of strategies for engaging with cultural difference and resisting dominance that included a focus on individual artists and issues, greater community engagement, reforming education and the unrealistic financial support of the western canon, battling cultural ignorance and de-categorising cultural difference to make it our central concern. The practical outcomes of this conference will define and influence the conceptualisation of future policy since artists working with cultural difference will continue to struggle with issues ranging between social equality and outlandish creative projects in the hope of negotiating new forms of an ethical, dynamic, multicultural Australia.

The conference was the best talkfest I have been to in terms of the quality and range of the papers, the high level of engagement from the audience and the inspiration for future engagements.

–

Globalisation + Art + Cultural Difference: on the edge of change Conference, Artspace, Sydney, July 27-29.

Papers from the conference will be published later this year by Artspace.

RealTime issue #45 Oct-Nov 2001 pg. 8

© Grisha Dolgopolov; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Melissa Madden Gray

Heidrun Löhr

Melissa Madden Gray

Melissa Madden Gray is a striking performer, whether in ELISION ensemble’s Liza Lim-Beth Yahp opera, Moon Spirit Feasting (formerly Yue Ling Jie, Adelaide Festival 2000, Melbourne Festival October 2001) or in Richard Foreman’s My Head Was a Sledgehammer for the Kitchen Sink company (Belvoir Downstairs, B Sharp, Sydney). Both are demanding works revealing the acting, singing, dancing and choreographic range of Madden Gray’s talents. She arrives for the interview with a touch of the flu, anxious about her voice—she’s performing nightly in the Foreman and rehearsing the opera during the day. But she is driven—no sooner has she been offered a seat and tea, than she’s whipped out the score of Moon Spirit Feasting and is demonstrating its vocal riches, how Lim has scored these and remonstrating with herself for singing when she shouldn’t.

When ELISION contacted me I had to do a demo tape. They’d heard about the work I’d done with Opera Factory in London which was a fairly extreme mixture of physical and vocal delirium. They had in mind a mezzo soprano with acrobatic skills. The framework for the demo was “chesty, nasal, guttural, Chinesey.” I stood in front of the microphone and I couldn’t find a way in to make those noises. This was during the horrors of Kosovo…you know that mass media imagery of all those women in trucks being carted off and that incredible keening, wailing. I couldn’t get it out of my head and the deadline was coming up to send the tape in and, ruthlessly, I used it. But it was honest in that I couldn’t stop thinking, what are we seeing in the world and what we are doing as performers and artists. Liza incorporated the essence of that demo into a chunk of the score—the Ghost Feeding scene. I had to re-process her processing of my ‘noise’ and then find a way into that but with her structure around it, still giving me quite a bit of room to improvise. That’s what’s exciting about working with a living composer.

Can you describe some of the sounds that you had to learn?

She’s making my voice sound like a Chinese gong, using microtonal inflections, throat distortions, gasps, ululations, exhalations, harsh whisperings, extreme crazy vibrati. Sometimes she talks about Chinese Opera parody. There’s Mandarin in there which is very heightened. There’s street Cantonese which is really rough as I discovered when I had some coaching in somebody’s office and caused heads to turn! They’re all the things that come out when you play with the voice and start looking at extreme forms of expression that don’t come out with the general social and theatrical preoccupation with beauty or with careful grotesqueness. Understandably, most opera singers don’t want to push their voices to those limits.

You find ways of placing less stress on the voice. The hardest thing for me with this music is actually being sensible because it is so fantastic. Once you’ve deconstructed it and put it back together again, and put it in your body, it’s hard to do it half-heartedly. I can’t really make those noises unless I really hurl myself into it. Half way through the opera, where I’m pretty “possessed”—and I have simultaneous images of empowerment and disempowerment—I am a vessel for various hungry ghosts and I’ve got all sorts of geisha rape images and Bangkok prostitutes going through my head—it’s hard to put a lid on it. But I had to because for the other half of the opera I’m singing very high and very purely and I simply can’t get those notes if I’ve shredded my voice.

Beijing Opera is very formal. How does this form connect with it?

I did a lot of research before we started, particularly a trip to Singapore and Penang with the director, Michael Kantor, and the designer, Dorotka Sapinska, and looking at the Hungry Ghost Festival that the opera is based on. In Penang, there are shrines on every corner and street theatres where these performances are in constant play to the hungry ghosts who are let out once a year for a month—basically, ghosts who have no descendants to worship them and therefore need assuaging and distracting with constant performance and offerings. Moon Spirit Feasting is based on those street theatre operas which are now in very tawdry form. You can see very old people mouthing the words but a lot of young people don’t know what’s going on. It’s much more fashionable to have a karaoke night or these incredible performances where starlets leap out of black limos and jump on stage and do a couple of numbers in clear plastic raincoats, yodelling…

ELISION’s opera has the feeling of a bridge between something esoteric and something very contemporary. It’s sexy, it’s plastic, the design is almost Foremanesque with its little box stage..

Liza’s very interested in the necessity of ritual and you see it in Penang because people are burning effigies while they’re on their mobile phones. It’s part superstitious and part really entrenched in the psyche. But this work never feels like it’s just a pastiche.

So how do you see the character you play?

It’s like the women performing in the street theatres in Penang during the festival and then she is also an ancient demon goddess who, in various forms of the myth, is either evil or good, fertile or infertile. I was also influenced, in researching this, by the sex clubs we went to in Bangkok. There’s a whole chunk of the opera, The Bridal Bed, where the entire sex manual—

—that’s when some of the audience start to get a little agitated.

Fantastic, I say! What’s art for? I tried to incorporate some of that as well. I had written a lot about the body in performance and pornography as part of my degree at Melbourne University. I did Arts Law and Honours in Fine Arts and German and was doing the final bits of my Law degree while I was still at drama school at WAAPA (West Australian Academy of Performing Arts).

An artist should always have yet another skill.

As much as I could I made it performance-related and I did the final exams when I was rehearsing with Opera Factory in London. By day I was this shrieking primal force and by night I was sitting saying, hmm, trust accounts.

What took you to WAAPA?

I’d had dance training. I had an extraordinary teacher—Merilyn Byrne. She was very strict but her major concern really was the joy of children dancing. I know now how unusual that is. She died last year but I realise now, I knew all the time, she was sort of my creative mother. I miss her terribly. Merilyn was so into the drama of it. She always had a monologue running over the top of everything—(SINGS) “The-ere is the hat for me, run, run, run….” It all had a sing-song thing which I think inadvertently led to my wanting to speak while I was moving.

So you always knew you’d go on to become a performer even with the arts law degree?

I was a stupidly over-imaginative child. I thought I was Elizabeth I for a period of time when I saw Glenda Jackson at age 3 or something. I was always performing. I had the full dance training in ballet and contemporary and jazz. I had a fabulous drama teacher at school and I was singing all the way through and also my mother used to take me to the Pram Factory when I was a wee thing and I would insist on going again and again to the same show, seeing people like Evelyn Krape and Tony Taylor and Sue Ingleton and, later, Robyn Archer. They are my strongest childhood memories. My grandfather was always taking me to the opera and Gilbert & Sullivan. So it was a very theatrical childhood. They’re all lawyers, so there was the simultaneous thing of, well, that’s lovely but of course, you’ll get a sensible career.

What were you performing at university?

It was really quite a hotbed of experimentation—Kosky, Kantor, Lucien Savron. It was a really exciting time and it set me up with an idea of the possibilities of theatre. And then I had a scholarship to go to Berlin. It was this strange world of cultural clashes and essential truths. There was an International Theatre Institute World Congress and I was the Australian rep to the actors’ workshops and I happened to be placed with the Butoh director, Tadashi Endo, who’s based in Germany. That was mind blowing—my first experience of Butoh—especially having come from a movement based background and then to be opened up in a totally different way. As I’d shifted more into ‘acting’, I’d almost had to negate myselfas a dancer, to get weightier or more grounded. This was a different way back into the body. As much as my dance training was incredibly theatrical, you’re still working with that upwards and outwards energy and that I-won’t-breathe-till-I-get-offstage sort of thing. So to suddenly to be thrown into such a primal movement world, which made so much sense, it was really quite extraordinary. At the same time I saw Pina Bausch do Cafe Müller. I had seen her work on video before but to be working in such a supposedly ‘foreign’ theatre form but feel that it absolutely related to tanz theater made sense to me about, I guess, where I am now, using everything I have.

So it helped to place you?

Yes, to say this is all you and these are all modes of expression and when it works it’s about the most pure, terrifying, visceral parts of us. I found that exciting because it’s natural for me to combine sound and body and not to divide them.

This is often seen in the West as hybridity rather than unity.

Hybrid is a great term in some ways but it sounds watered down to me rather than a built-up, holistic thing. Maybe we should refer to everything else as ‘divided’. The work that I’m attracted to, the people that I really love working with, are the ones who force you to confront why you censor.

After Berlin, you went to the Opera Factory?

First I went back to Melbourne University and wrote up my thesis on Annie Sprinkle and the body in performance. That was huge to work on because it felt like I couldn’t disengage from it in an academic or cerebral way. I started from a really anti-porn position, I guess, and the more I read, the more I started to think the more porn the better, the more in control of it people are the better, the fewer chances for exploitation, the more we realise the difference between fantasy and reality, the more we unlock the spirit, the less dangerous it is in repression. Having said that, then seeing those Bangkok sex clubs, I felt that I should re-write my thesis. You know, I’m an educated, white, middle class woman and, of course, speaking in relation to performance art and strip and exotica and pornography in a specific sphere. When I was faced with poverty en masse and desperation, obvious exploitation…so blatantly to do with power and money and the Western dollar, it was horrific. So I did re-enact a scene of that in the opera because I felt so broken by what I’d seen. And if you can’t respond in your artform then I don’t think you can justify being an artist. There are times I think I should be working in a women’s refuge where I can maybe tangibly measure—today I gave this person this phone number or took them and put them into a safe place. So I want to do that in my art and not make it a separate performance for people in the know.

This has been the great appeal of contemporary performance from the 70s onwards, where you can comment directly on your own experience, make your own life the material of your work.

It’s interesting now to know where to take that. I was in New York recently and I saw quite a lot of performance art and there’s such an expectation now for it to be transgressive. Where do you go from there? I saw John Fleck who was one of the NEA 4 and there was this great moment where he put newspaper on the floor and was about to shit and then didn’t. The only way he could now be subversive was not to be.

What made you decide you needed WAAPA?

I think I needed to feel that I had the training. I did Music Theatre but they sold me the course very much in terms of contemporary music theatre more than musicals. And they let me do plays with the theatre school and classes with the dance faculty and work professionally in third year. It was a fantastic place to be, particularly because of the people they brought through. David Freeman from the Opera Factory did a workshop for the STC and he used some of us. To meet and work with him just re-connected me with all of my instincts about what theatre should be. It was totally timely. His way of working is so extreme but I like that.

How is it extreme?

He says, why would you do an improvisation half-heartedly? That’s 2 hours of your life gone! He’s gathered all sorts of exercises and techniques from all over the world. He draws on trance and primal forces and he puts you very quickly into a place where you can’t con yourself. It’s the same with Butoh where you go straight to ‘the thing.’ So his method is to hurl you into a whole lot of situations where something might happen, those blissful moments of no-mind, when you’re not censoring yourself….It’s not indulgent, huggy theatre. It’s about life being short and getting rid of the rubbish and going straight to the essence of things.

Which shows did you do with him?

I did a workshop in Japan on Chikamatsu’s The Love Suicide at Amijima. Chikamatsu is Japan’s Shakespeare. And that was fascinating because there was a fabulous Welsh actor who’d worked a lot with the Royal Shalespeare Company, a Butoh performer now based in Paris, a Japanese soapie actress, a punk rock singer, a straight theatre actor and me. It was absolutely wild. We were doing the David Freeman version of this ancient play and because we didn’t have a common language we had to work in the most primal way. We all came from different performance traditions. In Britain David has this radical opera reputation. He’s got that preoccupation with the body and nudity on stage.

He’s still a provocateur after all these years.

He’s says, “I just can’t help it. They’re just so easy to shock!” So in London I did the final Opera Factory show called And the Snake Sheds Its Skin by Habib Faye, a West African composer, who writes most of Yousso N’ Dour’s music, and a British theatre composer, Adrian Lee on the epic of Gilgamesh. So you had David playing Monteverdi, Phillip Glass, rock’n’roll, all of these different musical genres. For Habib it had no chronological significance and none of the weight of a western canon. It was just music. And David was playing him that and he’s got this fantastic West African pop sensibility and he’s putting this ancient text to music and then it was being morphed into theatre again by a British theatre composer. That’s the kind of collaboration that I love.

Then you came back to Australia?

That production toured around the UK, then I worked with the composer John White. I came back and, since then, I’ve done the opera with ELISION and more recently lots of commercials and mainstream theatre.

These are survival gigs for you?

The commercials are but I just love performing. I am energised by that variety. Recently I played Hedy La Rue in the musical How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying for The Production Company. The following week I did a webcast to the Amsterdam Festival for their closing night, John Cage Song Books. I’d made 3 short films for them and we did this insane live webcast at 5.30 in the morning. The program included people like Joan La Barbara and Sonic Youth—quite a fantastic line-up. The piece that I did was a video duet with my mouth pre-filmed on a Satie phrase, “Et tout cela m’est advenu par la faute de la musique”—“all of that is the fault of music.” And I’d just got back from New York where I’d seen so much well-meaning self-conscious art and some pockets of inspiration but a lot of things that really made me think I’m not gonna find the answer in any city; it’s got to be about collaborating with interesting people globally. The John Cage Song Books sort of encapsulated the joy and exhaustion of the compulsion to create.

It would be very hard to find someone else to do Moon Spirit Feasting the way you do it. But on the other hand, it’s not your work, though you’ve contributed substantially to it. Do you want to build your own repertoire?

I’m doing a crazy 60s deconstructed French cabaret character, Miaow Meow, who is becoming quite a force. She’s emerging but she’s performed for the Totally Huge music gang in Perth at Club Zho with Lindsay Vickery. She’ll do some gigs at the Melbourne Festival. I realise how much of my work is about the shift between sexuality and fetishisation. With Lindsay, I’m working on all those pieces, feeding them into a program that will reconstruct them into totally new songs which I’ll perform as a kind of cyber 60s cabaret girl who’s broken down and come back together again in a new musical framework.

You don’t feel any contradiction? You talked about how Butoh and working with Freeman gave you a holistic sense of total focus and energy where you could suspend that sense of consciousness and yet still be true to the work. Nonetheless, here you are doing a range of work that might make some think, well, yes, she can do Moon Spirit Feasting and the Foreman, but How To Succeed In Business…?

It’s a fantastic part! It’s hilarious. And you’ve got 2000 people at the State Theatre in Melbourne every night who really love it. Always this perceived dichotomy! Rodney Fisher directed me in Design for Living at the MTC and will direct me in Masterclass later this year and was co-producer of My Head Was a Sledgehammer. He’s an extraordinary man who’s obsessed with language and text and he’s got the same kind of intense brain as David Freeman—same but different. They’re just people who are passionate about theatre and getting the essence of you. That’s exciting. I don’t see a difference.

You’re happily based in Australia?

Yes, but I think it’s creatively deadly defining yourself by or limiting yourself to any particular place or scene. I love travelling and the global collaboration that technology facilitates. I’m very excited to do the tour (of Moon Spirit Feasting) to Berlin and Paris next year. Hopefully I’m also doing Dennis Cleveland at the Lincoln Centre with Mikel Rouse. His music is the opposite to Liza Lim’s in many ways but it’s the same in that he’s absolutely specific. He draws on his culture which in this case is TV talk shows, New York. It’s totally different but it makes sense to me to work with those people. They are honest. That’s what makes them interesting. I don’t think there’s pretension in that work, which is what I’m terrified of as a performer. I want to keep finding the ‘real’…even though it’s always shifting.

RealTime issue #45 Oct-Nov 2001 pg. 4-5

Dr Terry Cutler

photo Vicky Jones

Dr Terry Cutler

Dr Terry Cutler is 53 years of age, a former chief strategist with Telecom until the early 90s, Deputy Chair of the advisory board to the National Office of Information Economy, 1997-98, Chair of the Australian Government Industry Research and Development Board, 1996-98 and Managing Director Cutler & Co Pty Ld as well as a Council Member, Victorian College of the Arts. Cutler was co-author with venture capitalist Roger Buckeridge of the Commerce in Content report which is said to have fuelled the Keating Labor government’s Creative Nation program.

Cutler’s appointment to the Australia Council is unique: he’s not just a businessman, but one working in new media with projects in Tonga, Malaysia and in Australia and has close connections with government. When appointed Australia Council Chair, Cutler briskly adopted a high profile and made unusually early pronouncements in the press, on IT pages, in an article he wrote for Business Review Weekly and in an edited version of a speech reproduced in the Sydney Morning Herald. In the SMH he was reported as saying that, “Creativity will be the crucial driver of the new economy…and that as the first new chairman of the Australia Council in the 21st century he will be pushing the value of arts in innovation” (“White knight on a mission…”, SMH, June 19).

It was “the value of arts in innovation” that caught my eye. In BRW he declared: “Creative artists will be at the centre of [the] next revolutions, creating technology-enabled solutions that, like all good tools, extend our human capabilities and horizons” (Cutler, “The Art of Innovation”, BRW, June 29). As with Creative Nation, the Blair government’s focus on creativity, the Queensland government investment in “creative industries, and the federal government’s Creative Industries Cluster Study (see below), the connection between the arts and industry is pivotal. Or is it what artists can do for industry? What’s in the relationship for artists?

With this in mind I thought it would be opportune to have a discussion with Cutler early in his Australia Council career, especially on this subject of innovation. Alessio Cavallaro (new media curator and project manager at Cinemedia, former director, dLux media arts), Linda Wallace (artist, writer & curator, most recently of hybridforms, Amsterdam for the Australia Council) and Sarah Miller (writer, Artistic Director, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts) joined in the discussion, which also included the Council’s New Media Arts Board Manager, Lisa Colley.

Just before the meeting date, Richard Alston, the Federal Minister for Communications, IT & the Arts, announced that the Australian Film Commission would manage a “$2.1m fund to seed the further development of innovative broadband content.” A second initiative was the undertaking of “a study of clusters in the creative digital industries to analyse cross-fertilisation that exists between various capabilities in the Australian economy, creative and otherwise, that are producing, distributing and marketing digital content and applications, and what are the key capabilities we need for the future” (www.dcita.gov.au, Aug 31). The panel monitoring the study is Colin Griffith (President, Australian Interactive Multimedia Industry Association), Professor Robin Williams (Dean, Faculty of Art, Design & Communication, RMIT), Kim Dalton (CEO, Australian Film Commission) and Dr Terry Cutler.

KG What’s in the Creative Industries Cluster Study (CICS) for artists, do you think?

TC Well, hopefully the fact that I’m on that small advisory panel to the study in my OzCo role rather than wearing some of my other hats. It’s been assigned to me to think about it in terms of the role of digital arts within the whole digital industry, digital content arena…[I’ve been] grappling with the issue of how you distinguish between some of the imaginings that we use in this area. We talk a lot about how digital content and digital arts are all digital content, but not all digital content is digital art…The value of the study I think is in trying to have a systematic overview of the whole value chain, if you like, of digital content production.

KG So it’s not just a matter of seeing people as networking or how they might help each other out by sharing costs and so on?