Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Dead Man Walking

Alongside its successful venture into Wagner’s Ring Cycle, and Parsifal, State Opera of South Australia continues its commitment to contemporary opera and music theatre creations (John Adams’ El Nino, Philip Glass’ Akhenaten) with the forthcoming staging of another American work, Dead Man Walking. Inspired by the film and book it was based on, the opera takes on the issue of capital punishment, a potent one in the USA with an increasing number of states rescinding the death penalty (partly a humane decision, partly a legal one driven by DNA testing revelations of innocence and threats of considerable litigation) despite their President’s commitment to it. The widely produced Dead Man Walking is accessible, emotionally intense, naturalistic opera (music by Jake Heggie and libretto by Terrence McNally) and as was so common in the 19th century, its audience will know the story from its appearance in other media. And this story is a true one. The opera makes a great companion piece to the Handel oratorio Theodora, as staged by Peter Sellars for the Glyndebourne Festival in 1996, which convincingly frames this tale of Roman persecution of Christians as an allegory for the ills of capital punishment, replete with the modern tools of execution (Channel 4/Warner Music Vision/NVC Arts VHS 0630-15481-3). As with the Wagner and the contemporary works in the company’s program, doubtless interstate opera fans will be crossing borders to see Dead Man Walking.

Dead Man Walking, State Opera South Australia, Sung in English with English surtitles, Aug 7, 9, 12, 16, 7.30pm Festival Theatre, Bookings through BASS 131 246

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 38

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Seeing something isn’t the same as listening to it. Seeing is about location—the eyes track the moving object and fix it upon the retina. But hearing is about objects in action. Our ears listen to a world in motion and the resulting sounds tell us about substance: crystalline or liquid, cracked or whole, being one or many. So through listening we hear the physical substance of a dynamic world and learn something that vision does not reveal.

The systematic exploration of the phenomenology of listening became prominent with the work of R Murray Schafer and the beginnings of the Acoustic Ecology movement in the 60s. Schafer challenged the dominance of ‘eye culture.’ He claimed that the acoustic environment has pragmatic and aesthetic value and that there is a moral imperative to improve the quality of life through the preservation and enhancement of our acoustic environs.

By the 90s the World Forum for Acoustic Ecology was formed with members across Asia, Europe and North America. Their latest symposium, including talks, presentations, group chats, soundscapes, soundwalks, an audiotheque, exhibition and a concert was held recently in Melbourne. Topics for discussion included linguistics, field recordings, methodology, performance, composition and noise pollution. At first the varying methods and topics among presenters made for an annoying lack of focus. But by the end I wished I’d been able to get to everything (cursed work hours). Nowadays, inclusion, multi-discipline and cross-practice get the prime logo spot on the academic corporate guernsey but Acoustic Ecology (AE) actually practices the exploration implied in working across boundaries.

Hildegarde Westerkamp, a hero of AE, took us on a soundwalk, or guided listening tour, through a nearby park. The walk had a lovely symmetry, beginning with the crunch of leaves underfoot and ending with the rustle of leaves overhead. In between, the acoustic space took on architectural qualities, indicating varying degrees of enclosure as we moved through open lawns, next to walls, alongside a lake.

The soundscapes concert was held at the new BMW Edge Auditorium in Federation Square: Scandinavian floor timber meets crazy-pave Meccano and glass beehive. Composers worked the mixing desk at the front, while the speakers of the sound diffusion system from RMIT’s Spatial Information Architecture Lab were distributed all around. The resulting acoustics were maybe a bit harsh and reflective in the upper mids.

First up was Doug Quinn’s perfect underwater recording of Weddell Seals. Evidently the furry brutes had been building some sort of cruel and gigantic cheese grater 50 feet below the Antarctic ice cap and a fight had broken out. One for the marine mammal noise cognoscenti. Certainly changed my attitude to the clubbing of baby seals. Gabriele Proy then presented 3 beautifully recorded pieces. Lagom used sounds of children dive-bombing in water, playing tennis and football. Transitions from tram rides to water to ballgames hinted at the easy sociability of games. Natural sounds were treated as both document and material for synthesis in Barry Truax’s Island. The sound of wind across a lake, waves on the beach, frogs croaking, water dripping in a cistern and a final windy shoreline produced an intense mood and drama, volume and space. Next was Angel by Jo Thomas, with program notes about the passage of time, the body and the voice. I didn’t hear that within the piece but the audience liked it.

Lawrence Harvey played his Canopies: chimerical acoustic environments, originally produced for the 200 metre long Soundscape System in central Melbourne. This work showed off the spatialisation capabilities of the diffusion system, particularly the use of the front/back axis, as well as Harvey’s expertise on the mixer. Transformed wood-chimes, shells, beads and small bells made up the sonic material in a piece that moved to a beautifully quiet finish. Westerkamp used ‘rainsounds’ to evoke the west coast of British Columbia. Cars on a wet road. Wet gravel walks. Subtle modulations across short and long time scales and another clear and dripping ending.

Westerkamp (with photographer Florence Debeugny) also had an installation in Hearing Place: Exhibitions and Audiotheque, organised by Ros Bandt and Iain Mott of the Australian Sound Design Project (www.sounddesign.unimelb.edu.au). At the Edge of the Wilderness explored the ghost towns of British Columbia through recorded soundwalks and photographs. The poetry of the images, the rhythm of their presentation on the wall, the soundwalk as a narration, all evoked the damp decay of abandoned timber towns. I’m familiar with Ros Bandt’s work through CDs, books and her symposium talk. An acute sense of space comes through in her recorded works, and I regret only glimpsing her piece and missing those shown at the Yarra Sculpture Gallery.

I did however get a chance to hear Iain Mott’s piece in the Audiotheque—a binaural recording of Mott having a haircut. In a binaural recording, microphones are placed as though they are in the ears of a real head: this technique achieves a spatial representation of sound that is close to actual listening. The technique is particularly good for headphone use—the speakers-in-the-ear headphones mirroring the stuck-in-the-ears microphones. Mott’s decision to record a haircut binaurally (mics in his ears) is inspired. The proximity and pressure of the headphones replaces the hands and the scissors to give a haircut without the cutting. The haircutting sounds are heard as intrinsic to the haircut experience. Mott’s piece, like the strongest work in the symposium, used sound to recreate the sense of being within an experience while drawing conscious attention to the importance of the acoustic environment for the emotional and informational content of that experience. Which is where Acoustic Ecology began.

International Symposium of the World Forum for Acoustic Ecology, hosted by The Australian Forum for Acoustic Ecology & The Victorian College of the Arts in co-operation with Goethe-Institut Inter Nationes; various locations in Melbourne, March 19-23

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 30

© Greg Hooper; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Hydrogen Jukebox is an opera from 2 of the 20th century’s most controversial artists, composer Philip Glass, transgressor of classical music boundaries, and Beat poet/hero the late Allen Ginsberg, whose work is still about as contemporary as any can be. Using 18 Ginsberg poems as libretto, the opera paints a musical mosaic of America from the 50s to the 1988 Presidential election—and into the present. Synchronicity and the 60s still conspire: while this Australasian premiere was in rehearsal, the war in Iraq was brewing. In Hobart the show’s dramatic posters, on which Ginsberg’s words form Stars and Stripes dripping like paint slowly attracted a layer of anti-war graffiti. The war was at its height during the performance at Hobart College and we were all “…listening to the crack of doom on the Hydrogen Jukebox” as Ginsberg wrote in HOWL.

Rarely performed, Hydrogen Jukebox has a reputation for being difficult, but this production moved seamlessly from poem/trance to musical lightning strike across a canvas of controversial, confronting territory—political propaganda and anti-war feeling, personal anguish and sexual politics, religious and cultural dissonance, so content-rich and energetic it left me gasping.

Director Robert Jarman deserves high praise for making this important work accessible to a new generation eager for the hard-won truth: that sometimes art can explain life better than we think. Jarman’s innovation was the side-screen projection of scrolling computer text, taken from the net, listing US government and CIA interventions. Meanwhile, centre stage, Ginsberg’s lyrics rode effortlessly astride Philip Glass’ mesmeric musical lines. Glass uses the human voice as instrument and instrument as voice—just as Ginsberg played around with bizarre adjective-noun combinations. Medleys of incantations—“Who is the enemy, year after year…battle after battle…” (Iron Horse) form hypnotic, lilting word/sound waves that travel from performer to audience like electric musical current. This is a powerful and confronting production.

Behind the singers, actors made a living fresco—in Grecian white robes, or statuesque in plush towelling, slowly rubbing the stars and stripes off bronzed flesh, or forlorn in trench coats, travelling, crying. There’s humour too—Aunt Rose in lopsided 5/8 rhythm, and The Green Automobile, camp, upbeat.

Many in this production’s cast perform regularly with Hobart-based IHOS Opera. Of particular note were Sarah Jones’ crystal soprano, Matt Dewey’s wonderfully resonant bass-baritone, Chris Waterhouse’s and Craig Wood’s smooth tenor and Robert Jarman’s reading of Ginsberg’s Wichita Vortex Sutra. Thematically, as we crossed beyond America into the buddafields, into now-ness, I felt I’d watched a new media form being invented. This beatnik opera’s mix of imagery and soundscape is explosive, but gentle beyond words.

Hydrogen Jukebox, University of Tasmania Conservatorium of Music, composer Philip Glass, libretto Allen Ginsberg, director Robert Jarman, conductor Douglas Knehans, choreographer John Rees-Osborne, lighting Tony Soszynski, sound Malcolm Bathersby, Hobart College, April 15, 21, 24-26

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 30

© Anne Kellas; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

This year’s Totally Huge New Music Festival featured established artists from opposite ends of the new music spectrum. Putting experimental electronicist KK Null on the same bill as renowned contemporary classical composer Roger Smalley says a great deal about Tura Events Company’s eclectic and inclusive approach to programming. By amalgamating practitioners from various musical practices (who share only instrumental virtuosity and an infatuation with possibilities), the organisers demonstrate a commitment to continually blurring the boundaries that define new music.

Those unfamiliar with Smalley’s contribution to Australian new chamber and piano works might have found scheduling a 60th birthday concert in a ‘new’ and cutting edge festival somewhat contradictory. However when Smalley and the West Australian Symphony New Music Ensemble premiered Kaleidoscope, such preconceptions were quickly erased. The work is defined by short contrasting movements, circulating a divided ensemble (strings, woodwind and a horn, trumpet, percussion and harp group). The music was built up in thirds, creating great variation within a relatively limited space; swarming dynamism against stasis.

Smalley also paid tribute to the influence of 20th century composers, performing Suite No 1 by Stravinsky and a transcription of Scriabin’s 10 Poems, a reclamation that highlighted the continuing significance of work from new music pioneers. Principal oboist Joel Marangella had the perfect vehicle to display his technical talent in Smalley’s Oboe Concerto, his riveting presentation followed by the first performance of Piano Study No 1 (Gamelan). Composed for left hand alone, this was the first in a trilogy of projected pieces that focus on producing sound from the piano’s lower register, exploring the percussive, gong-like qualities of the black keys. The impressive works performed that evening confirmed Smalley’s reputation as a principal innovator among the local and international new musical field.

Belgium’s Rubio Quartet attracted a similar, but not quite as diverse audience to the Perth Concert Hall. Patrons packed into the foyer, an intimate, but perhaps not ideal venue for the Australian debut of Dirk Van de Velde and Dirk Van den Hauwe (violins), Marc Sonnaert (viola) and Peter Devos (cello). The quartet’s inventive programming enthralled the audience with instrumental virtuosity in an intense and refined performance from their modern repertoire. The players clearly revelled in the String Quartet No 4 by Shostakovich, whose music they describe as a “second language.” The audience was then lulled by the gentle ambience of Luc Van Hove’s lengthy Opus 3, before the unexpected outbursts of Wolfgang Rihm’s String Quartet No. 4. Undaunted by the structurally unusual piece, the players tackled each challenge with emotional energy, revealing their passion for works that manoeuvre at the edge.

However, it was the work of the young composers of Breaking Out that truly reflected the freedom and independence characteristic of new musical approaches and convinced audiences that chamber music is far from an insular form. Among the groundbreaking artists were David Howell with a bold statement in Chipped Chrome, a striking viola and trumpet combination; Nela Trifkovic with the 2nd song-cycle of Give Me Back My Rags and Year 12 Christchurch Grammar student Kit Buckley (the youngest composer in the program) whose String Quartet No 1 explored the sound worlds of an emotional response to architecture.

Chamber music experimentation continued as ethnomusicologist and artist in residence from Hanoi, Vu Nat Tan introduced listeners to the unique timbrel qualities of the Vietnamese bamboo flute. The ethereal music inspired many Perth improvisers to join in with Tan. Ross Bolleter’s improvisation on his famous ruined piano (part-prepared to retain some of its melodic function but mostly fractured by squeaks, groans and the rhythmic tapping of soundless notes) was later joined by Lindsay Vickery on clarinet, infusing the textural palette of sound with a lyrical quality. Then came an unexpected performance by Tos Mahoney on flute and finally Jonathan Mustard, playing a unique variety of wind and percussion instruments, setting the pace for the intense musical ferment to follow.

Relationships between traditional Western, Vietnamese and found instruments were explored in collaborations between Daryl Pratt from Match Percussion, Peter Keelan and members of Tetraphide Percussion. One of the few electro-acoustic collaborations involved Hannah Clemen, using her own invention to manipulate the sound of the bamboo flute. The first of a series of installations, the instrument in Clemen’s Intraspectral, was designed to separate and highlight the sounds that comprise the harmonic spectrum of voice. Back in the gallery, listeners were invited to vocalise into a microphone while a computer analysed the various qualities of their voices and responded unpredictably. This unique discovery challenged audiences to explore the extent of their vocal expressions and discover new ways of listening and responding to sound in daily life.

While the festival had an undeniably acoustic flavour, electronic noise fanatics were not forgotten. Perth’s reputable Lux Mammoth gave audiences one final aural nightmare to remember them by, leaving the senses truly alert for the devastating onslaught of Japan’s KK Null. In a predominantly improvised performance, Null’s pounding techno beats, intricate, dense and fascinating layers of noise and abrasive rhythms interwoven with some heavily distorted vocals, produced moments of juddering physical intensity. Null’s performance completed this year’s diverse conglomeration of local and international artists, in a festival that bristled with an undisciplined intermingling of sounds, instruments, media and music methods, giving greater complexity, new meaning and expanded purpose to the musical arts.

Totally Huge New Music Festival, presented by Tura Events Company, April 4-13

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 31

© Sarah Combes; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

This title suggests the common view we have of Medea, who slaughters her children supposedly out of jealousy when her husband leaves her. It’s a powerful and enduring myth—she’s the ultimate Bad Mother. (And our own continuing horror/fascination with Lindy Chamberlain testifies to this phenomenon.)

In another night: medea Nigel Kellaway pairs this classic with one from the modern repertoire, Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. Albee’s play answers Medea, with George killing off the (imaginary) child the couple has raised, after a night of cold fury, slugging it out in the living room in front of transfixed guests (a role designated for the audience).

This work is less concerned with the children’s deaths, though, than their parents’ lives: it is the Jason/George/Nigel and Medea/Martha/Reggie show. (Indeed, later on “Nigel” has little patience with “Reggie’s” [Regina Heilmann] pillow-baby smothering.)

Welcome to the Games that Lovers Play—or at least the rather less innocent and more manipulative ones long-term couples play. You have to know someone very well indeed to unerringly home in on and bring out their worst every time—or, in the case of long-time collaborators Kellaway and Heilmann, their best, as in this production.

another night isn’t just about middle-aged dysfunction, nor does it merely display the rubble of plundered texts. It also has more profound comments to make on the material itself and there is a clear logic at work which rebuilds these stories into a commentary on those same old, same old stories we fall back on, and the dead-end, self/mutually destructive grooves we lapse into. It’s an invitation to think anew.

This we particularly see through an especially gorgeous feature of this production, the 18th century Clérambault Medée cantata, sung by counter tenor Peretta Anggerek. The cantata itself stops short of the dastardly deed of infanticide and thus cuts short the natural conclusion of the Medea story. The pierced, tattooed, half-naked body-builder is not our usual image of an opera singer, and Anggerek embodying Medea the foreigner, Medea the enchantress is thus a double reminder that things aren’t always what they seem and assumptions can be dangerous. This Medea might well tell a different tale from the one that has repeatedly been told of her.

The set also echoes this invitation to shake out our preconceptions. Beginning mostly in darkness, all we can see are the grand piano downstage right and, prominently centre stage, a golden sofa (with Heilmann resplendent upon it).

Uh oh. In the last month both a playwright and a designer have commented separately to me on how much they hate “sofa” theatre, the writer claiming that it was almost worth checking in advance to see if there was a sofa on the set before buying a ticket: it’s become shorthand for unadventurous, naturalistic TV theatre-family drama at its most banal. Of course that doesn’t turn out to be the case here (though no one takes the credit for the set design), and a black gauze screen swings up to reveal 3 more musicians, behind them a cascade of scarlet drapes descend from ceiling height creating performance spaces on several levels.

What I also find particularly fascinating in this work is its lively conversation with opera in its high art form, rather than in its original (and opera Project) understanding of a “work” in its broadest sense.

Kellaway sways towards opera with live music (4 very talented musicians, including a truly delightful trio of harpsichord, baroque violin and viola da gamba), surtitles and the outstanding talents of Anggerek. At the same time, the sumptuous artificiality that is opera is neatly paraphrased/parodied by the ballerina-in-the-jewellery-box that is Anggerek in his opening scene; framed by red curtains, dressed in golden silk, revolving jerkily to the sounds of appealing music. An ironic answer to the all too familiar “park and bark” school of opera performance?

While static display is not part of Kellaway’s aesthetic, display certainly is, and Annemaree Dalziel again contributes costumes. Most gorgeous are Kellaway and Heilmann’s robes with full swishy skirts—great for flouncing about the stage—a sumptuous pink and gold for Heilmann, regal purple with frills for Kellaway. And Anggerek’s 18th century inspired half gown (all the better to see your pierced nipples and tatts with) is truly fab.

This show is also, I feel, The opera Project at its most accessible yet. Surtitles! A play (well, movie) we all know! Of course, there’s Heiner Müller mixed in there too with his Medea Material, but even he is digestible, given enough context, as we are here—and he certainly provides the text for some of the most theatrical and striking moments of the piece, especially in ‘solos’ by Kellaway and Heilmann.

Heilmann in her toxic frock sequence is wonderful: as she plans doom for Jason’s bride-to-be, she brings it (literally) on herself—and, unwittingly, thousands of years of condemnation with it. Twitching and grimacing on the floor, this lethal charmer is mesmerising.

That Kellaway revels in the language and music and their interplay in this production is clear. The sung and spoken texts are better integrated here than ever before, and they work powerfully off one another. An extract of Müller’s Landscape with Argonauts transforms into a visually and aurally arresting duet between Anggerek singing the cantata on the top level of the stage with Kellaway standing immediately below him, spitting out the text in the music’s pauses.

At the end, the screen descends once more, again cutting off the musicians from the performers, returning us to the beginning, and “Nigel” sends the “children” (the musicians) off to bed, before wandering off himself.

Everyone has gone except Medea who remains sprawled on her couch, her fiery, golden chariot; there before it begins, there after it ends. After 2500 years, she’s not going to stand for being pushed around/pushed off stage anymore—she concludes the evening with a defiant “Fuck you, Nigel!” But was anyone listening? Well, yes, the “guests” were still there and paying close attention.

The opera Project Inc, another night: medea, director Nigel Kellaway, performers Nigel Kellaway, Regina Heilmann, countertenor/narrator Peretta Anggerek, piano Michael Bell, baroque violin Margaret Howard, viola da gamba Catherine Tabrett, harpsichord Nigel Ubrihien, lighting/production Simon Wise, costumes Annemaree Dalziel, music Clérambault, Poulenc, Schubert, Melissa Seeto, Performance Space, Sydney April 30-May 10

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 32

© Laura Ginters; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

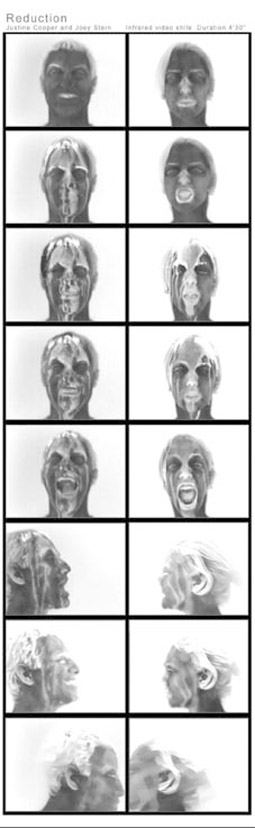

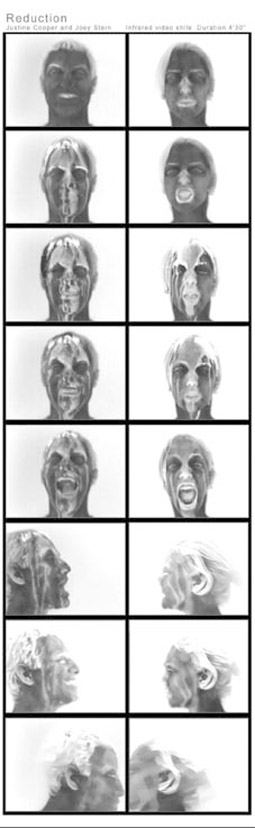

As Harriet Cunningham reported in New Music in Sydney: a lively corpse? (RT 52), contemporary music doesn’t fare too well in Australia’s biggest city and not for want of trying. However, Ensemble Offspring, a project-based collective of musicians with a commitment to new music, is one of a handful of groups that keeps the scene turning over, this one with idiosyncratic programming and keen audiences. Later this year they’re off to take up invitations to perform in the Warsaw Autumn festival, and in Krakow, London and the Netherlands. Then in November, as part of the New Music Network’s New Music Now series they’ll present the ‘imaginary opera’ of Matthew Shlomowitz, The Cattle Raid of Cooley or The Show, which is described as “a double narrative singerless opera exploring the (im)possibility of program music.” The same concert will also feature a multimedia work by composer Barton Staggs and digital artist Justine Cooper (see article). In their most recent concert they explored the work and legacy of idiosyncratic American composer Harry Partch (1901-74) with a day long exhibition of musical sculptures and new instruments and a night-time concert. Partch has no obvious musical heir, but his legacy has been widely distributed and appears in part in the work of many, hence the concert title Partch’s Bastards.

Partch’s percussion-oriented, instrumental inventions were influenced by ancient Grecian and Eastern models and were integral to his music theatre works like the magnificent Delusion of the Fury. Believing that Western music was out of tune, Partch proposed tonal alternatives, creating a rich musical vocabulary of his own, often working with voice, spoken, intoned and sung. In his Illegal Harmonies, Music in the 20th Century, Andrew Ford describes Harry Partch as a key precursor to Meredith Monk and Laurie Anderson. It was appropriate then for Ensemble Offspring’s concert to open with the composer’s Barstow (1941), a droll musical ‘road movie’ of hitchhiker inscriptions (Partch spent years as a hobo and itinerant worker) for voice and adapted guitar. Performer Christiaan van der Vyver ably rose to the demands of the work’s moments of gospel beauty and personal lament, and folk-tune iterations. The work required the guitar frets to be shifted to realise Partchs’ microtonal tuning. Other ‘instruments’ included 60 ceramic tiles (with a surprising range and sometimes bell-like depth) scratched and tapped in Teguala (2002) by Juan Felipe Waller (Mexico/Netherlands) and wine glasses in Amanda Cole’s Cirrus (2003), rung with fingers, tapped and bowed until they vibrated and whistled, evoking fragile violins and theremins.

The second Partch work, Two Studies in Ancient Greek Scales (1950), deftly executed by Jackie Luke (dulcimer) and Julia Ryder (cello), was a more demanding experience, worth a re-hearing to allow the brain to adjust to its strange tonalities. Christiaan van der Vyver’s ensemble piece, Light Flows Down Day River (2003), was a gently marching, bluesy concoction with an Eastern tang and featured the composer’s home-made xenophone with its bright, rounded notes. With characteristic flair, flautist Kathleen Gallagher brought the requisite theatricality to a Partch evening with her performance of William Brooks’ (US) Whitegold Blue, a relatively abstract piece requiring notes to be bent or plucked from the flute, and the voice to speak, hum and whistle. Lou Harrison’s engaging Canticle No 3 for the largest ensemble of the night (5 percussionists) had its welcome gamelan-ish moments and some notable passages for guitar and ocarina (Gallagher again) and ranged through intimate and huge sounds, pauses and delicate hesitancies. The concert lived up to its subtitle, An alternative world of sounds, and although the tonalities of Partch and his bastards sound for the most part more familiar than they did half a century ago—so broad has our collective musical experience become-there was still much to challenge the well-tuned ear. The excellent program notes were by Rachel Campbell.

Ensemble Offspring, Partch’s Bastards, concert coordinator Damien Rickertson, Paddington Uniting Church, Sydney, May 3

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 32

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

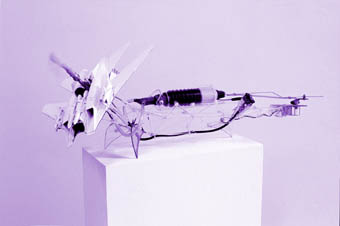

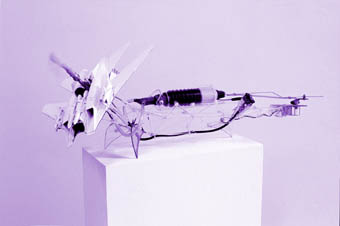

Simon Cavanough, Silly Aggressive Lust

Simon Cavanough is a path-maker artist, his work is about forging myriad in-roads towards ascension, as in Head on a Stick, the impossible blueprint for the clever boyish self-image (no body, but a spindly tower of etched lines and geometries), holding aloft its cute decapitation. Happy as Charlie in the Chocolate Factory, who ends up flying high above the city in a glass lift. Cavanough’s show, Pathway to Wellness at the Scott Donovan Gallery, contains the dream of becoming an anarchic Biggles, except the planes are all plastic or in pieces, co-opted for the war machine or wedged between bits of rock in a precision flying fantasyland. What else goes up? There are balloons inflating, little bridges, factories, houses, Puffer Dude! All Knockin Back the Sky.

Though what you’ve really got is a beer bottle flying machine, propped on top of a delicate, almost collapsing, undercarriage. That’s where the strain comes in. What must come down. After all Cavanough isn’t singing naively along to the radio in an impossibly green field-sky rockets in flight, afternoon delight—his work reminds us that we are grounded horizontally in a world of detritus, not vertically in the ether. And his inventions are all awry, are unnecessary, like Structures for Holding Up Clouds—a piece of scaffolded yellow styrene. Also toying with precarious suspension is his collapsing bridge, The Road to Wetness and Dribble, a reinforced gloopy drip about to break. Nothing inspires confidence, All the Good Things Sometimes Fall Over. (And indeed, at the opening, people are accidentally bumping into and knocking fragile pieces off the podiums!)

Model making seems to have become very popular in contemporary art—artists are making models of things popular consumer culture already produces en masse, and exhibiting them in galleries. Cavanough’s antipathy to recognisable form—he uses everyday materials similar to arte povera—comes with the criteria that things must be dissembled and unrecognisable as such. He might use the pared back frame of a plastic lotus flower, as in I’ve Been Looking at the Ways of Higher Beings, though by the time it’s incorporated it’s been completely pulled apart. You get the sense that it’s important that the work doesn’t reek of popular culture, that the impulse behind it is a frustration with form and meaning, the dumb materiality of what’s finished and proper and produced. His reconstructions are forever attaining, never achieving, recyclable and fragile in their coherence—just one possible iteration. This isn’t the model-making associated with late 20th century nerd boys making sci-fi, anime, mecha—it’s deliberately not that pop.

The assemblages are the products of a ‘poiesis’—“or all representation whether visual or verbal is a making, a constructive activity, a poiesis” (The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics). Though model-making is technical, formulaic, you must follow set procedures, there are diagrams, it’s in every way rule governed. It’s a craft, if anything. Perhaps Cavanough is attracted to the anti-art nature of craft—is tempted to abandon art practice. Just as Duchamp gave it up “in favour of playing chess” in 1923 (though he didn't really). “In fact he continued working on his long-term project The Large Glass…What is important here is the gesture rather than the fact. (Kay Campbell, “Out of Humour” in Wit's End, MCA, 1993). And Cavanough seems also to deviate, because the instructions don’t allow for an intuitive or perceptual path. So he ends up making art after all. Once you leave the manual behind, what emerges is bricolage. And there’s the sense that the artist has had to invent his own narratives driving the will-to-form from these askew assemblages—there’s a wizardry, a role-playing or warped war game feel. Why are the plastic figures of Airmen suspended on stalagmites of fibreglass, tumbling like circus performers, euphoric and gleeful, or, more likely, are they free-falling from the sky? The organising principle of these often small 3-D works is that they are whatever the artist has scavenged, perhaps from a studio floor strewn with beer cans, model aeroplane parts, Redhead matches, and the refuse of styrene and foam, as it fell in the bin. All the accidental flotsam and jetsam of one person’s idiosyncratic practice and aesthetic eye. The process reminds me of Hany Armanious’ fantastic folky and arcane installations, involving the chance juxtapositions of found objects.

Cavanough is also technical, literally inventive—like his contraption for failing to fully inflate a pink balloon—which again puts in way too much effort for outcome. Its electric bellows, piston, plastic tubing and dirty old saw blade, all try to breathe life into the balloon—while straining and trembling with effort, shaking under the pressure. Is there a pathway to wellness for the patient on such a shonky respirator? Or does playfulness undercut the masculinity, the whimsy of pink balloons that will cure? It seems the artist is as wistful as his titles. You feel he might be wryly writing off some punk excesses of his youth—Silly Aggressive Lust signals his awareness of the eternal air of adolescence underpinning the avant garde: Graffiti: I once thought it would be cool to nail some meat to a wall of a bank but now I’ve mellowed.

Failure is a leitmotif. Cavanough once tried his hand at rocket-science in the suburbs—I’m Going Higher Than I’ve Ever Been Before II—though the event, the aspiration, the experimentation was what cathected. It was an attempt not just to test a hypothesis with almost guaranteed results, but to witness the danger, and abjection of failure, harking back to when flying machines crashed at air shows, rather than today’s high tech ‘friendly fire’ accidents. The rocket did get a metre or more off the ground, climbing the structure built to launch it, getting as far as the path went—while failing to reach the sky’s aporia (perhaps luckily for the residents of Tempe). I get the feeling the artist would also like his practice to launch and re-launch itself in unpredictable directions, while necessarily factoring in failure—I can see him as artist-in-residence at a regional RAAF base—as a dishonorary wing nut. Poetic licence, pilot’s licence—wanting both.

This show is toned down for the gallery setting, less elemental spectacle. It’s Cavanough in ‘hobbyist’ mode, building A Little House for Me & You in a city bedevilled by property development. It’s a modest, generative show, making some runways out of the ‘endism’ that characterised the embers of the late 20th century. The minutiae of this work is fitting, giving a perspective on the ground that suggests the aerial view—it’s metaphysical (both poetic and material) but doesn’t require transcendentalism out of the cosmos. And the show adds subtle continuity to the artist’s body of work that exceeds the gallery paradigm—his work has always been endlessly deconstructive/reconstructive, concerned with both disinvention/invention. Simon Cavanough continues to make fragile, failed objects—resisting art—in that they are kind of hard to classify, fetishise and buy. He’s also exhibiting here in a gallery facing imminent closure (perhaps to re-open somewhere else)—though this isn’t about being trapped in any victimhood cycle, Oh Wizard, rescue me with your canoe. It’s more a bit of nostalgia for old magic—for the sky which remains plentitudinal.

Simon Cavanough, Pathway to Wellness, Scott Donovan Gallery, Sydney, April 2-26

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 33

© Keri Glastonbury; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Prime Two

photo Damien Van Der Vlist

Prime Two

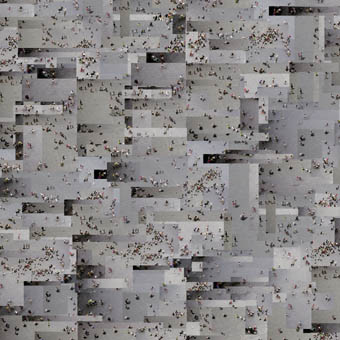

Prime Two was like an SMS conversation—fast and focussed. The Queensland Art Gallery was given over to people, movement and multiple performance spaces, with a dynamically different (and younger) crowd than at the openings I’ve attended. Inside, the noise was louder than at the largest opening, with the boom of the outside stage audible and overlaid with other music, acoustics and percussion. Instead of the usual focus on one event, this more disparate arrangement saw crowds gather around performances. Others flowed past, on their way to other dance, music, sound or performance points.

Prime Two was an ambitious program developed by the Gallery to engage a youth audience (13-25 years) they believe are “up for the challenge of contemporary art.” Its focus was hybrid art forms. Short performances from musicians, artists and performers working around and over each other ran from 2 until 8pm. Planning was required if you had an agenda and a wish-list of things to see, although simply following the noise and crowd had its charms.

The central water mall hosted Rock’n’Roll Circus 5 times over the 6 hours, teetering tantalisingly close to the edge of the bridged walkways. But despite acrobatics on precariously stacked chairs, nobody fell in. There were sudden and spectacular fashion and design parades. In an adjacent space, Phat! Streetdancers were synchronicity in motion, building on hip-hop, pop and rap influences, playing to riveted crowds and enthusiastic applause.

There were 5 strands—prime movement, prime art, prime fashion+design, prime interactives, and prime sound—none of which was privileged over the others. Performances and changes were not announced—each just began and ended or morphed seamlessly into the next.

While some strands of Prime were static displays—exhibitions and paintings up to the QAG’s usual exacting standards—those with performative and interactive possibilities moved outside the gallery ‘square.’ Chalk it out by Archie Moore provided a blackboard for graffiti from “the whole class”, and the audience shared their views on schools with little inhibition. This was located in the sculpture courtyard within earshot of the Prime stage where DJ Indelible alternated with performers Menno, MC Battle, and the first Australian show by Samoan rap and hip-hop duo Feliti+JP.

A Prime performance that literally intruded into the crowd was Jemima Wyman and her “Body Double”. Jemima and sister Aja variously rode, beat, pushed, and kicked an oversized carrot-shaped orange bolster around the space in moves influenced by kickboxing, Kung Fu, mime and slapstick. Any conceptual depth was hard to identify, but the 2 performers clearly enjoyed the catharsis of letting go on a large phallic signifier.

Refuge was available in the Prime rumpus room, designed to celebrate the fads of the 1980s. If you hadn’t played Twister since childhood, here was your opportunity. There were also video clips and retro music designed to bathe you in comforting childhood memories and orange light—nostalgia for the young.

As night fell it was standing room only in the sculpture courtyard as Resin Dogs took the stage for the first performance of their national tour. As they exited, a white screen rolled down from the marquee, transforming the space for a mesmerising performance from Lawrence English and Tara Pattenden mixing sound and visuals. It was a fitting finale to 6 hours of stimulation attended by 4,000 young people, it brought the crowd to a brief silence.

Prime Two, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, Apr 5

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 34

© Louise Martin-Chew; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Three distinct categories of work exist within Scott Redford’s exhibition I’ve got my spine/I’ve got my orange crush. Yet though the shockingly pink Surf Paintings, the almost abstract photographs of the Urinal series, and the Dead Board video works are segregated, they are thematically interrelated by their references to homosexuality and in the use of the surfboard motif. These also mark them as a continuation of Redford’s previous distinctive explorations.

The large Surf Paintings are made, like surfboards, of resin-coated Styrofoam. Painted onto this foam base are sketches of Gold Coast scenery: high-rise buildings and palm trees, all in evocative silhouette. The smooth, highly reflective works initially seem all impenetrable surface, and, struck by their size and intense colour, the tendency is to regard them as a group and at a distance. But beneath their shiny seals the painted foam is grainy, like layers of multicoloured sand, and a closer look at the fine washes of pigment reveals their painterly qualities.

Redford has boldly—brashly?—interspersed these works with pieces that are similarly highly-coloured but otherwise blank, except for attached surfie-logo-like stickers, or text: “Our goal must be nothing less than the establishment of Surfers Paradise on earth.” Secret Surf Painting gradates horizon-like from pink to purple, accompanied by a plaque that proclaims: “The content of this painting is invisible; the character and dimension of the content are to be kept permanently secret, known only to the people of Surfers Paradise.”

The surfboard is, for Redford, linked to homosexual sex: his catalogue interview with Chris Chapman recounts a story about a well-known surfer who strapped boys to his favourite board before having sex with them. While this link may be personal, Redford also works with a more commonly recognised gay sex location in his Urinal series. The dark and gleaming close-up photographs present this quotidian hardware as surprisingly beautiful, the scratched surfaces burnished by the flashlight and coated in streams of water trickling in skittery rivulets down the dented, rusted facades.

The contrast of the brightly-coloured Surf Paintings with the dark and impervious metal of the urinals seems to pit the glitter of the tourist strip against the secret confines of the public toilet. The Surf Paintings are almost iconographic, potential mottoes of Gold Coast publicity. Possessing an entirely different glamour—not to mention comfort and hygiene—the appeal of the urinals is far more private. Each Urinal work’s title is followed by a location—(Surfers Paradise) or (Fortitude Valley)—and, so noted, they seem to function as mementos, fixing an encounter firmly in history like a scribbled phone number or snatched Polaroid.

The surfboard motif is continued in the video works Dead Board I, Dead Board II and Dead Board III (a “dead” board being one that no longer floats). In the first a surfboard leans against a parked ute; written on it in large red letters is the word “DEAD.” A young man takes a handsaw from the Ute and cuts the board in half. As it collapses, he stands back and regards it for a moment, before glancing toward the camera as the shot fades. Dead Board II shows 2 men cutting up surfboards and spraypainting “DEAD” on the boards. The excruciating Dead Board III features bikini-clad models—all perfect skin and limbs and hair—performing the same task in the more upmarket setting of a Gold Coast hotel room. In the catalogue Redford explains the girls were chosen to replace the boys in order to please his (straight) video collaborator. This last video is painful to watch: the girls are uncomfortable and horribly inexperienced at wielding the saw, coming fascinatingly close to severing fingers or scraping expanses of smooth tanned flesh. After they finish their chopping and hacking they stand and leave, admirably concealing their relief. The floor of the empty room is left littered with sorry and broken boards, not unlike, in the setting of the expensive hotel, prone lovers exhausted by their exertions.

Unlike the finely executed Surf Paintings and Urinal photographs, the Dead Board videos are an inelegant case of point-and-shoot. Redford was assisted by different artists on all 3 bodies of work, but the disappointment of the Dead Boards cannot be blamed solely on the shortcomings of the video. Rather, they have the off-putting sense of being made on a whim, and as such demonstrate the considerable distance that often exists between concept and manifestation, a distance that must be negotiated with care. Unfortunately, in this context the accompanying catalogue validation becomes almost humorous, if not objectionable. The repetitive screeching of the handsaw possibly does illustrate the “concept of modernism as an endlessly recycled paradigm.” But there’s a difference between “a play on the idea of boredom” and just boring.

I’ve got my spine/I’ve got my orange crush, Scott Redford, Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia, March 28-May 4

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 34

© Jena Woodburn; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

'Eternity boy', Enmore Road, Enmore Megan Hicks

An hour from Melbourne—a small cream fibro cement cottage, paint peeling, curtains fading. Inside it’s dark, cool, ants are making their way around. It is 2001, and the owner has only just left for the nursing home, but all over the house is evidence of the last 70 years. A calendar from 1956 hanging in the kitchen, letters from the turn of the century in the cupboards; old tins of laxative pills, matchboxes from the 50s with Aboriginal men standing on one leg and the sunset behind. There are recipes for Sao biscuits from the Depression, there is hand stitched linen; the laundry pegs are the big wooden ones Victorian children used to fashion into dolls. There is a collection of old mops hanging up, a wringer, and many old tin buckets and basins for handwashing. So much it is overwhelming. It’s a museum. And a few months later everything is collected by a younger relative who torches it in an all-night bonfire after downing a bottle of Jim Beam. Such is the ephemeral nature of most of our archives. Like memory, they can disappear overnight.

But the job of the archivist is to fix, to preserve. We are all collectors, accidental and considered. We hoard, we classify, we fetishise; magical objects arise from the everyday. The House of Exquisite Memory, at the Sydney State Records Centre, tips its hat to the “natural born archivists” (the hoarders, the children, the obsessives), although most exhibitors here are art professionals, a fact which is initially disappointing. However, the exhibition is necessarily reflexive given this: while some pieces work precisely as archives—Megan Hick’s Flat Chat, a photo documentation of footpath graffiti, is a fixing and celebration of what is fleeting in the everyday—others explore the nature of archive and memory.

In The Housing of Memory: off her rocker Fiona Kemp returns to the family home where her father, certainly a natural born archivist, has allowed the family archive to accumulate. From this, she has selected objects from her childhood and arranged them in a series of Perspex picture boxes—an autobiographical narrative of fragments, junctures and collisions. In one a type of suburban mise-en-abyme emerges: a hanky with images of washing hangs on a mini washing line, Astroturf below, in front of a photo of a backyard washing line. In another, the text “she always rocked herself to sleep at night” underscores a box in which a small blue dress hangs beside an empty hanger, with old receipts for clothes arranged underneath. There’s a haunting quality to it, and while there’s certainly an element of play here, there’s also loss and longing; gaps between objects and part-stories.

This is also the case in Barry Divola’s Critterholic, which traces a recuperation, not only of the objects but the practice of archiving. There is something here—in the recreated suburban kitchen setting, in the empty kitchen chairs at the Laminex table, and the Perspex cereal boxes, containing small toys—that resonates with a nostalgic recovery; not least because Divola’s present collection attempts to recover his lost one of 60s and 70s plastic cereal toys. (Divola resumed his cereal toy collecting 5 years ago—his mother had long since thrown out his childhood collection.)

Sally Gray’s My Garden as a Family Archive features dried flowers, images, and text suspended from the ceiling by string tied to rocks on the ground. Each picture twists with the breeze and movement in the room, giving us glimpses, a moving ephemeral montage of memory and attachment, where the familial and familiar are implicated in the complex of the garden. Memory, we are often reminded in this exhibition, is a collection, an archive. And in these works memory seems to disrupt more linear archival practices. Zoë Dunn’s first sounds and words, as recorded by her parents, again alert us to our often unnoticed practices (parents are always doing this kind of archiving), and the trajectory they trace along all our anxieties and desires.

James Cockington’s Memory Triggers is an assemblage of knicknacks and miniatures dating from 1966 (small because they had to fit into a shoebox in his bedhead) and features such objects as a mini Fanta bottle, and a Whitlam era it’s time badge. The miniatures are time capsules, synecdoches for an era. The collection is assembled as an enclosed checkerboard, part of a loungeroom setting facing a TV which plays Maree Delofski’s film The Trouble with Merle, an exploration of the conflicting stories about Merle Oberon’s background. I caught the end, with Merle’s “return” to Tassie where the convergence of studio bio and truths, gossip and secret (all archives in themselves), marks “a disaster” for the film star and the beginning of her so called decline.

That the exhibition is anchored in references to the everyday—loungeroom settings, checkerboards, kitchen settings, gardens—affirms that the everyday and familiar are sites of desire, longing, loss and recovery, asking us to consider what makes us collect; what are the practices and rituals that trace memory and recuperation about?

In David Waters’ Bus Farm, at the Yarra Sculpture Gallery, miniature wooden buses, perhaps a hundred or more, made from redgum sleepers with burnt relief, are arranged about the room; children visiting the exhibition wanted to move them around (and did). Playful, nostalgic, indelible, the repetition does recall childhood, toys—but they are rendered with a precise aesthetic that marks the work as artisan. Waters gestures to mass production, hence Bus Farm, and there’s some irony intended in the mass production of something so obviously hand crafted, raising broader issues about the question of replication. But this replication evokes a feeling of comfort, both in the reception and, I imagine, in the production; there’s a delight in this, an intimacy.

Considering this, I sit on the refashioned bus seats, and, looking down on the buses I see a street scene, a herd, and recover a feeling of the power of childhood; our domain over our magical objects.

The House of Exquisite Memory, curator Susan Charlton, designer Kylie Legge, State Records Centre, Sydney, Mar 28-Aug16; Bus Farm, Yarra Sculpture Gallery, Melbourne, Feb 19-March 12

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 35

© Michelle Moo; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

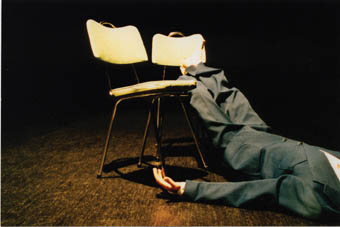

Brendan Lee, Death is a matter of time

courtesy the artist

Brendan Lee, Death is a matter of time

Brendan Lee’s video work is founded on a dissection of the technical devices used in mainstream cinema to produce emotional effects in the viewer, and his reinterpretation of those effects to subvert their original context and experiment with their use in isolation for other purposes.

Death is a matter of time is a short work building on the use of the eye in cinema. We all know that the eye is the most compelling of human features, window to the soul and all that. To me the eye means little without the face around it, so let’s see how Lee broadens the meaning of the image of an isolated eye with his digital wizardry and intellect.

Death is a matter of time is a companion piece to the installation “…a matter of time”, showing in May at Melbourne’s Gertrude Contemporary Arts Space. I haven’t been able to see the larger work, so must examine this smaller work in isolation. The video comprises 3 images: an LED countdown clock on 0:00:00:00; images of a flame and an explosion superimposed on the pupil of a man’s eye, from which tears drip. Then an ambiguous image I’m told is a sniper, is superimposed on a woman’s eye, it whites out then reappears as the eye widens before whiting out again. These superimposed images stutter in time with a faint heartbeat sound.

The implication is that the eyes express their owners’ realisation of their imminent death; that which kills them is reflected in their pupils. Removing this cinematic device from its context allows the possibility that these eyes are also those of the cinema audience. The “eye of the soul” cliché takes on new meaning as I consider the eye as portal to the language of symbols, accessing the subconscious, where the layers of correspondence a symbol brings become the building blocks of further meaning.

One image of the eye from modern cinema that leaps to mind is the recurring dilating pupil in Darren Aronofsky’s drug-filled Requiem for a Dream. I don’t think of that particular image as a device: it’s a coded message with one layer of meaning for the general public and a deeper, exhilarating but scarier one for those who’ve explored life’s darker pathways. Experiencing Death is a matter of time is instead more poignant in light of recent world events. We all think of ourselves as possibly immortal, until we aren’t.

My copy of the CCAS press release with its still of a man’s eye has been sitting beside my computer for a couple of days, spooking me. It’s too quiet. They say you never hear the one that gets you.

Death is a matter of time, Brendan Lee, Canberra Contemporary Arts Space, March 29-May 3

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 35

© Gavin Findlay; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Poolside Manifesto, Forgetting Tuesday

Love Tester, a site-specific, installation-based project opened at the Virus Lounge, a gaming centre on Francis Street in Northbridge Perth, one hot, late-summer night. Regular clientele were locked away behind glass in a grid of computer consoles, air-conditioned, seemingly oblivious to the swelling art crowd and intent on blowing their opponents’ virtual brains out.

Here they creep through dark labyrinthine environments, avoiding ghouls and zombies in search of the prize. In our case, we are informed, the prize is art, and the labyrinth is a somewhat brighter (if no less seedy) Northbridge. The zombies are self-explanatory, especially on a Friday night.

The arcade game, Timezone, pac-man, pinball, Playstation and Pot-Black are all plundered in Love Tester’s hot-pink, heat-sealed promotional material. We get it already! Love Tester is the product of Nintendo-generation boredom, short attention spans and engagement with a local arts scene that continuously battles the seemingly effortless high production values of popular culture. Pilar Mata Dupont’s opening-night performance, Estrella the Pony, engaged the audience with the generational theme of the Love Tester. A 20-something woman with a My Little Pony fetish grooms a life-sized plastic horse in the Virus Lounge car park.

Love Tester is the latest attempt by 2 curators and 13 young artists to shift the local visual arts paradigm from the confines of gallery-based exhibitions and thrust it in the face (or at least the peripheral vision) of the general public. It follows similar successful event-based and site-specific projects including Hotel 6151 (2002), Peep-in-Death (2002) and the video-based Drive-by (1999) to which it is more closely aligned.

Scattered between various Northbridge businesses, the locations of Love Tester’s individual works are disclosed on a map: large hot-pink symbols at each venue guide audiences from place to place. These measures largely avoid the risk of each intervention being subsumed within its environment, although investigations in the weeks following the jubilant opening night revealed some fragile points of connection between project aspirations and the actual work.

I searched in vain for Nathan Nisbet’s Bentley the Bear, an audio-visual collaboration between Mark McPherson and Philip Julian, putting its absence down to the kind of natural attrition that often occurs when site-specific works are displayed over long periods. Things break down. Julian and Nisbet’s Flow Form at Merizzi Travel did however successfully project its morphology of symbolic and design forms for the duration of the show.

Pearl Rasmussen and Danny Armstrong’s Empty Man Comic Strip stencil series was barely distinguishable from the greasy, black patina of chewing gum on the pavement of William Street, but this may have been its point. The artists’ subtle monochromatic animation is activated by the viewer only while walking, and staring down at the pavement.

Poolside Manifesto’s Forgetting Tuesday at Virus Lounge was easily the most resolved and engaging installation in the program. Consisting of a disturbing ice-cool, pastel wall painting and cut-outs illuminated by fluorescent lighting, the work takes its cues from retro fairy-story illustration and early learning texts such as the Janet and John series. Spanning at least 15 metres, this immersive work describes disembodied scenes, including a robin redbreast caught on a hook, and a boy flying his heart like a kite.

In Bennett Miller’s 2-part installation, Where’s The Love, at Pot Black and the WA Skydiving Academy, the artist repeats motifs from previous installations involving stuffed animals (this time, a leopard caught in a net) and a TV set showing the still, pixilated image of a cat, or boy. Enigmatic and indecipherable, Miller anticipates audience confusion with a quote from the late William Burroughs, “What is this asshole Bennett, who smokes two packs of cancer a day, really saying?”

Love Tester, AFWA’s Emerging Curator Project, curators Jess Clarke & Jennifer Lowe, various venues around Northbridge, Perth, March 28-April 20

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 36

© Bec Dean; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

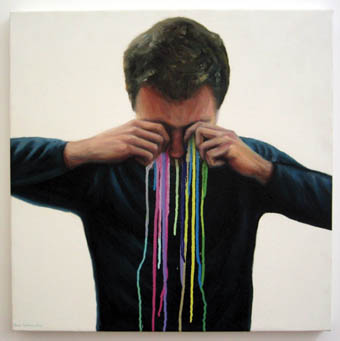

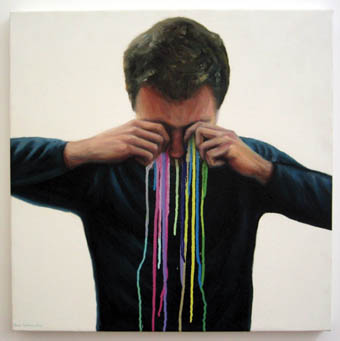

James Cochran, The Artist’s Tears, oil & enamel on canvas, 63 x 63cms

The most engrossing works in this fine exhibition by Adelaide artist James Cochran are self-portraits in which the face is either not realised in detail or just not seen. In the most striking, The Artist’s Tears, we see neither eyes nor expression, only the copious tears of paint he weeps (the work has been purchased by the Art Gallery of South Australia). In the smaller portraits the visage is a soft blur of blocks of colour, their arrangement curiously evoking a forceful personality in meditative moments. An accompanying video shows the artist stretched out, staring into a puddle of water on a busy city footpath, studiously ignored by passersby. Other works reflect the artist’s interest in down-and-out street life with a vivid coloration that draws on his years as an aerosol artist and brings an odd warmth to scenarios of despair.

James Cochran, Narcissus, Gitte Weise Gallery, Sydney, March 26-April 26

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 36

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Dead Man Walking

Alongside its successful venture into Wagner’s Ring Cycle, and Parsifal, State Opera of South Australia continues its commitment to contemporary opera and music theatre creations (John Adams’ El Nino, Philip Glass’ Akhenaten) with the forthcoming staging of another American work, Dead Man Walking. Inspired by the film and book it was based on, the opera takes on the issue of capital punishment, a potent one in the USA with an increasing number of states rescinding the death penalty (partly a humane decision, partly a legal one driven by DNA testing revelations of innocence and threats of considerable litigation) despite their President’s commitment to it. The widely produced Dead Man Walking is accessible, emotionally intense, naturalistic opera (music by Jake Heggie and libretto by Terrence McNally) and as was so common in the 19th century, its audience will know the story from its appearance in other media. And this story is a true one. The opera makes a great companion piece to the Handel oratorio Theodora, as staged by Peter Sellars for the Glyndebourne Festival in 1996, which convincingly frames this tale of Roman persecution of Christians as an allegory for the ills of capital punishment, replete with the modern tools of execution (Channel 4/Warner Music Vision/NVC Arts VHS 0630-15481-3). As with the Wagner and the contemporary works in the company’s program, doubtless interstate opera fans will be crossing borders to see Dead Man Walking.

Dead Man Walking, State Opera South Australia, Sung in English with English surtitles, Aug 7, 9, 12, 16, 7.30pm Festival Theatre, Bookings through BASS 131 246

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 38

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

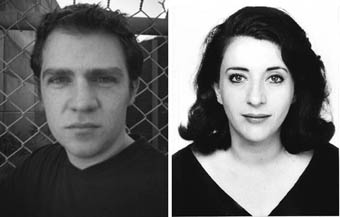

Robin Fox, Anthony Pateras

The Melbourne sound scene is a factional, sprawling, many-headed beast. If this sounds like a gripe, it isn’t. Take it as fact posing as opinion. The audience required to sustain such a monster exists, though it consists largely of sound practitioners, and we are prepared to venture far and wide, geographically and aesthetically, to look each head in the mouth and hear the echoes of our own voices shouting down the chasm.

As pleasant as it is, Footscray Community Arts Centre, a bluestone basement on the banks of the Maribyrnong River, is not the most accessible venue. It takes a brave aural adventurer to take on the quest. The 5th series of Articulating Space, held every Monday night in March, ran the gamut of sweltering heat to biting cold, and veered sonically from grating tedium to compelling aural assault.

This, of course, is one of the series’ main strengths. A diverse and challenging program is essential to the health of any event, and it’s a feature of the many other heads of the Melbourne sound art beast, but Articulating Space distinguishes itself by the context within which work is presented. It’s show-and-tell. Artists present their latest works in a matter of fact way that largely sidesteps or informalises the ‘performance before an audience’ aspect.

This trend really became apparent when the out-of-towners performed, becoming exceptions that prove the rule. Jim Denley (Sydney/Brussels), KK Null (Japan) and even the pairing of Philip Samartzis and Casey Rice (Melbourne/US) for the first (and last?) time, were compelling more for performance reasons than necessarily sonic ones.

Meanwhile, among the locals, there was an almost total removal of the entertainment factor; the performances were more akin to demonstrations, or workshops. That’s not to say that the issue of performance was not addressed at all—c’mon, this is still the performing arts, folks! In particular, performances by followers of the extended techniques religion (Jim Denley, Anthony Pateras, Tim O’Dwyer etc) obviously had to address performance. Denley was most interesting, perhaps because he chose to perform from the centre of the seated audience in what seemed an attempt to direct attention away from himself as performer. However, watching Denley’s bodily gestural theatre is as crucial as the sound.

In contrast, Thembi Soddell also performed within the audience, but as transparent sampler anti-performer. She presented a compelling combination of shy quietcore and abrupt volume/intensity cuts that hinted at a perverse grunge aesthetic.

There was the usual predominance of laptop/mixing desk performances, which seem to naturally raise the question of performance. The laptop performance argument is getting somewhat boring, and increasingly irrelevant, but I have to say the ‘3 amigos of laptop’—Steve Adam, Ross Bencina and Tim Kreger were exceptional because they gave a real sense of 3 musicians/artists playing as an ensemble. This was also largely evident in the sound they produced, as the usual range of smirks and grimaces in the glow of the monitor screens gave little away. Showing even fewer facial tics, Tim Pledger and Dave Nelson, ostensibly twiddling knobs on a mixing desk, presented a focussed piece of restrained discord and harmony interplay, and tonal tension.

But back to the show-and-tell where Klunk (Rod Cooper) stood out. Prefacing his performance with an explanation of how he came to design and build his continuous bowing instruments he methodically moved through the instruments’ koto/hurdy-gurdy-like plucking and dronal effects, offering a mesmerising sonic insight into his work.

The show-and-tell format also becomes interesting when familiar performers present, allowing analysis of the micro developments in an artist’s oeuvre. Tim Catlin continued his explorations of the sonic range of the electric guitar, presenting the instrument in perhaps the most fragile and delicate fashion he has to date. Natasha Anderson has extended her wind instrument fetish so far that the only remnant of an instrument was a hand operated air pump! Robin Fox and Will Guthrie stretched the ‘Fox Paradox.’ Fox, an extremely knowledgeable analog synthesis historian, performs using software processing that requires audio input to process, in this case Guthrie’s percussive tinkering. Fundamentally this is the opposite of synthesis, which generates output from a purely electronic starting point.

Ultimately, deliberately dismissing any pretence toward entertainment means audiences need to consider not whether they enjoyed the event, but rather whether they learnt or discovered anything. Articulating Space consistently provided fertile opportunities for sonic discovery.

While Anthony Pateras takes a well-deserved break from organising the series, and its return to Footscray remains in doubt, it would be a shame if this type of sound art event disappears from the scene.

Articulating Space: Live Electronic Performances and Extreme Acoustic Practices, A Music Hive Presentation, Footscray Community Arts Centre, Melbourne, Mondays in March

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 29

© Nat Bates; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

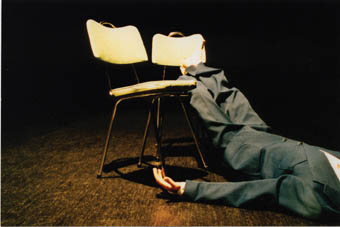

Phillip Gleeson , The Follies of Emptiness

Dancehouse curator Helen Herbertson’s Bodyworks 02 was a showcase of well-developed, inspired works from Rosalind Crisp of stella b, Tess de Quincy, and Phillip Adams of balletlab. By contrast the 2003 program largely consisted of modest pieces at earlier, tentative phases of their development. Martin Kwasner, Tim Davey, Rakini Devi, Eleanor Brickhill and Phoebe Robinson presented fine studio studies containing compelling elements or moments, but none was cohesive or satisfying in overall form. Sue Healey’s Fine Line Terrain also had a searching inconsistency for the opposite reason, it was adapted from several longer studies with more dancers and a complete design. Although Bodyworks 03 reinforced Dancehouse’s position as an institution promoting catholic, innovative choreographies, it remains unclear if Bodyworks is an annual ‘showcase’, or a more experimental season.

The uncertain, sketchy quality of Bodyworks 03 meant that those pieces developed from a strong, cohesive idea, or which self-consciously grasped and worked with their own play and ebb-and-flow were all the more impressive. Born in a Taxi for example presented a superb structured improvisation, using general yet stringent narrative and characterisations on which to hang exuberant yet often vaguely melancholy clowning and movement. Although The Potato Piece was new, performers Penny Baron, Nik Papas and Carolyn Hanna have worked together for years and so the project represented a more evolved showing of their established physical, dramatic style.

Michael Nyman’s lightly pulsating, neo-Baroque music helped emphasise the Peter-Greenaway-esque, tangibly sensorial nature of the production. Simple set elements such as heavy, wooden boxes and planks, a pile of rough tan-bark, water, textured hessian and garden produce-potatoes, apples and oranges-solidified the show. It also made it as much about the audience’s empathetic identification with the performers-smelling fruit, discovering new tastes and textures, or settling to work seated upon cool, upturned tin pails-as about any overt narrative or character development. Three figures, each associated with a particular fruit or vegetable, moved from isolated introspection and self-devised physical rituals, to meet, exchange produce and gestures, and sort through their collective materials. The performance was like a quizzical coming-to-life of a still-life, complete with the glistening, painterly patina of ripe, cut fruits and warm lighting by Nik Pajanti in the style of the Dutch masters; a sort of opera buffo in Buster Keaton style physical game-play and dance.

The show concluded with the characters’ discovery of books amongst their surrounds-another element from the tradition of late Renaissance still life. This final device led to a delightful sequence in which each performer stood on a heavy, oaken cube, gesticulating and physically relating the tale that they had just read intently to themselves. However this sequence was less well integrated into what preceded it, the characters failing to return to their central, identifying props (potatoes, apples, oranges), closing with an explosion of business largely unrelated to the motif of the 3 growers. The Potato Piece was nevertheless a thoughtful, joyful performance.

Dianne Reid’s Scenes From Another Life also sustained a sense of comic play. For Reid however, this was tied to an interest in her own self as a form of remembered, public performance. Reid’s physical intonation exhibited a quality common to several of Melbourne’s mature independent dance-makers (Sally Smith, Felicity MacDonald, Shaun McLeod, Peter Trotman). Although her apron-like costume and clearly-defined musculature evoked Chunky Move’s young dancers, Reid and her peers have abandoned the exploration of physical extremity as a device for developing choreography. Reid performed with more of a sense of the everyday and with a wonderful softness and lightness, which made the sudden lilts of strength and precision that come with a dancer’s body all the more charming.

Using text, music and projection, Reid explored the uncertain body of the public performer. Unlike the more conceptual, linguistic model developed by choreographer Simon Ellis in Indelible (see RT 54), here memory was inherently psychokinetic, melding pleasure, discomfort, hallucination and the physically remembered past in the act of recalling events. While Ellis clinically yet evocatively rendered the idea of memory, its structures and its conceits, Reid amusingly depicted the psychophysical experience of finding one’s body suffused with the quirks of recollection.

Tiny, projected versions of the performer clambered and tumbled over her torso as she looked on, disconcerted by this bodily revolt, yet also lovingly empathising with her diminutive other selves, helping them over her shoulder with a gentle push or lift from under their feet. Reid explained that she wasn’t even sure if these and other remembered gestures and songs were her experiences or moments from films she’d seen, or stories she’d told. As the show’s title indicates, the body and our sensory memory constitutes another life, including dreams, awkwardness, yet also our pleasures and our most comforting personal sensations. Reid concluded that the bemused confusion she felt about the source of these impulses and sensations mattered less than the idea that one can recall with absolute certainty such mundane feelings as “stretching out on your stomach, in the sun, like a cat.”

The highlight of Bodyworks 03 was director Phillip Gleeson’s The Follies of Emptiness. Ben Rogan’s most notable performance trick is a roiling of his abdominal organs and musculature to represent psychophysical disorder and alienation. Under Gleeson’s guidance though, Rogan’s form became a microclimate of electric ripples and erratic tremors. Gleeson’s lighting created an environment in which Rogan and Trudy Radburn’s bodies melded with wavering tangibility sustained by Expressionist aesthetics (The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, Pandora’s Box etc). By using barely perceptible, misty illumination, juxtaposed with brightly-focused points of light hovering in darkness, Pajanti helped render the performers as semi-decomposed, textured phantoms, unfixed within the audience’s perception of space and depth.

Emptiness was not, however, a neo-Expressionist homage, despite its superficial visual similarity to that dark scion of illusionistic, vaudevillian cabaret. The show was characterised by a more viral sense of mutation and interaction. Jen Anderson’s exquisite, scintillating sheets of noise drew on some relatively ‘popular’ music such as Aphex Twin and Einstürzende Neubaten, but overall the score sounded similar to contemporary French electro-accoustics like those on the label Les Emprintes Digitales. The turbulent, musique-concrète-crazzle echoed and reinforced the sense of an explosion of sensations outwards and inwards-of bodies and personalities absorbing and projecting everything from cheap, electrical lights to hissy 1960s tango-pop; from the lurid, luminescent orange wallpaper Radburn absent-mindedly sashayed before, to the vinyl and chrome kitchen chair Rogan fused with, spider-like. Just as the score sometimes resonated with a sudden backward sweep of magnetic tape sound, one had the occasional impression, watching Rogan and Radburn, of viewing videotape in rewind.

There was a bleed-through of signals, influences and emotions, a mutual contamination of sparse, thematic elements that made the few moments of robotic, automatic movement seem more akin to a wildly visceral form of wet-ware, virtual reality (which of course it is), than the now venerable idea of Cartesian, mechanised life. As in David Lynch’s Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive, or even Jean Luc Goddard’s more raggedly inter-cut work, the very DNA of character and emotional ambience here became subject to spontaneous change, producing an uncontrolled, hypnotic sense of instability at every level. This jumble of references created a deliberately abstruse portrait of weird, (sub)urban, formlessness, or domestic cyberneticism. Emptiness was particularly impressive in this respect, given that Gleeson eschewed almost all of the touted, glossy tools of contemporary new media normally employed to achieve such effects within his own rich yet minimal dramaturgy.

Bodyworks 03, curator Helen Herbertson, lighting Nik Pajanti, John Ford, Dancehouse, Melbourne, Mar 12-30; The Potato Piece, Born in a Taxi, devisers/performers Penny Baron, Nik Papas, Carolyn Hanna, direction Tamara Saulwick; The Follies of Emptiness, director/choreographer/lighting/set Phillip Gleeson, performers Ben Rogan, Trudy Radburn, Max Beattie, music & sound Jen Anderson, Kimmo Vennonen; Rust, performer/choreographer Martin Kwasner, dramaturg Tim Davey, text Allan Gould; The Dusk Versus Me, performers/choreographers/projection Tim Davey, Katy MacDonald; Q U, performer/choreographer Rakini Devi, percussion Darren Moore; Scenes From Another Life, performer/choreographer/video Dianne Reid, costume Damien Hinds, dramaturgy Yoni Prior, Luke Hockley; Waiting to Breathe Out, performer/choreographer Eleanor Brickhill, performer Jane McKernan, music/text-performance Rosie Dennis, lighting Mark Mitchell; The Futurist, choreographer/performer Phoebe Robinson, music Tamille Rogeon, sculptures Alex Davern; Fine Line Terrain, choreographer Sue Healey, performers Shona Erskine, Victor Bramich, music Darrin Verhagen.

RealTime issue #55 June-July 2003 pg. 39

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Emma Saunders, Elizabeth Ryan, Jane McKernan, Blue Moves

photo Heidrun Löhr

Emma Saunders, Elizabeth Ryan, Jane McKernan, Blue Moves

In the world of film noir the femme fatale is mysterious, duplicitous, heartless and usually gorgeous. In classic thrillers we know them as helpless damsels in distress. Think of the forlorn Isabella Rosselini in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, the terrified Janet Leigh in Hitchcock’s Psycho and the cunning Mary Astor in The Maltese Falcon. A long tradition of violence has been perpetrated on and by women in stories like these. They’ve been paraded through popular culture to become mythic icons in themselves.

As in their previous works, which have lightheartedly explored aspects of the female psyche, in Blue Moves The Fondue Set (Jane McKernan, Elizabeth Ryan and Emma Saunders) examine the leading lady in their own terms. Through an ensemble of dance, movement and monologue the work steps beyond the archetypes offered by film to present a more contemporary brand of mademoiselle.

They enter wearing uniform red-patent boots and clingy dresses. They sashay, hips swaying, looking nervously behind them, legs giving way with every second step. The moves suggest archetypal victims, but these women are strong, graceful, coy, sexy, noisy, angry and violent.

The more successful moments of Blue Moves take just a small element of the archetype and play with it. One piece sees Ryan sprawled on the floor, crawling after a microphone that is pulled away from her. Panicked, breathless and silenced, it’s an arresting analogy for the victimised woman.

The work is less effective when the group tries to modernise the plight of their women. In one piece Saunders pounds out a vengeful version of Kylie’s You’ve Got to Be Certain, hurling punches, sideswipes and knee jerks at an invisible ‘ex.’ An amusing take on modern revenge for the broken hearted, the premise is too thin to entertain for the length of the song. Elsewhere, in an awkward chorus of laughter, wavering between the cackle of the femme fatale and the howl of the wounded, the idea seemed lost on both performers and audience. Rather than unpacking any filmic codes, it felt like we’d missed out on a private joke.