Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Why is bad theatre so excruciating? Why is it so much worse than bad film? This question vexes many of us who spend a reasonable amount of our professional lives sitting in uncomfortable spaces enduring the slings and arrows of tragic theatre. So when the word gets out that something good is happening, we are prepared to endure a stinking hot night and a venue renowned for back-breaking seating and zero oxygen. Who and what was the cause of all this selfless devotion? Blame Matthew Lutton, whose outstanding physical and truly absurd production of Ionesco’s The Bald Prima Donna, had audiences in raptures during the 2003 WA Fringe Festival. Not surprisingly, it was awarded Best Fringe Production.

Lutton has packed a lot into his young life. At a mere 19 years of age, his credits include director, writer and performer. As a performer, he has been clown, acrobat, puppeteer and actor. With his company, ThinIce Productions, he has adapted and directed several productions. In 2002, he wrote and directed the sell-out physical theatre piece Trading Fates at the Blue Room Theatre and presented a self-devised work at PICA during Putting on an Act. So far this year, Lutton has directed the epic masked production of George Orwell’s Animal Farm and worked as assistant director on Be Active BSX’s Six Characters in Search of an Author and Black Swan Theatre Company’s The Merry Go Round in the Sea. In 2004 he is looking to direct Bed, a new script by Sydney writer Brendan Cowell in a multi-dimensional, audio visual and visceral production at PICA. Lutton is definitely across the boards (sic). He has just been appointed Director of BSX, a company for young artists producing new and contemporary theatre works with professional support from Black Swan Theatre Company. Oh, did I happen to mention that Lutton is currently completing his 2nd year of Theatre Arts at WAAPA. Long live good art.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 32

© Sarah Miller; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

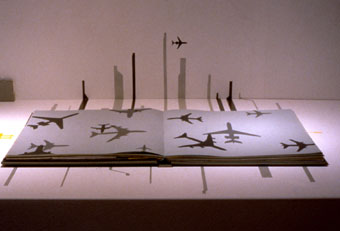

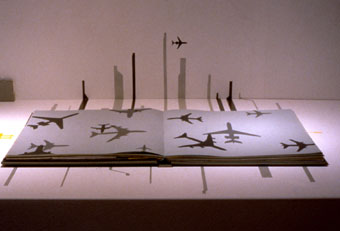

TV Moore, The Dead Zone

In a small, darkened sideroom in Sydney's Artspace, 2 large screens face each other. You sit on a padded seat between, turning to take one in and then the other, adjusting to 2 close views of a man running slo-mo through an empty Sydney CBD. Because he’s running backwards and because the speed isn’t modified to the point of mere artifice, and because the man keeps turning his head to see where he’s been/heading, there’s a loping anti-gravitational lyricism to The Dead Zone that adds to the doomsday suggestiveness of empty streets and time undone. Or, as Moore notes, “this barefooted man is certainly terrified but perhaps he is in fact running from himself.” The work was exhibited at the recent showing of Helen Lempriere Travelling Art Scholarship 2003 finalists at Sydney’s Artspace and was Highly Commended by the judges. With relatively simple means, Dead Zone exploits our cinematic awareness to maximum effect, multiplying meanings in a short time and lingering much longer than its 3 minutes 30 seconds duration. We’ll be watching more TV Moore.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 39

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

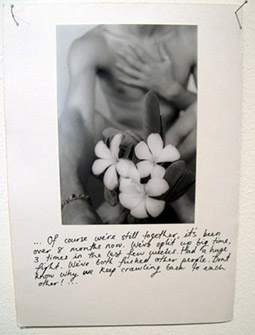

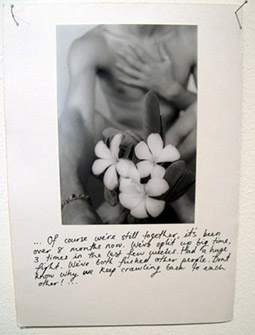

Mel Donat, Memory Play Back

Combining the warmth of analogue audio and video equipment with the calculated cool of their digital offspring, 4 Sydney artists explore a range of transitional/crossover/meeting points—between sound and image, personal and public, past and future, remembering and forgetting, observer and observed… Andrew Gadow, Mel Donat, Tim Ryan and Phil Williams emerged from Honours level electronic arts studies guided by senior lecturer Peter Charuk at the School of Contemporary Arts, University of Western Sydney. This year they will have an exhibition, Digital Decoupage, at First Draft Gallery, December 3-14. With varied interests, they work separately as well as on collaborative projects.

Gadow explores the translations from sound to vision and vice versa, generating pulsating video images from analogue synth keyboards, and making sounds from video footage. Most recently he exhibited in Tracking at Bathurst Regional Gallery. Gadow’s next appearance is at the upcoming Electro-fringe festival in Newcastle. Donat, working primarily in animation and installation, uses “subversion and contradictions to explore issues that may be considered disconcerting.” The installation—to be shown at First Draft—Memory Play Back, incorporates a hand-made soft toy rabbit, which operates as an interactive interface via which the viewer manipulates 3D imagery and sound. Donat’s experimental piece Trigger Displacement screened in the 2003 St Kilda Film Festival. Williams works mainly with sound in performance and installation, and for Digital Decoupage he continues with themes developed in the recent installation approaching silence at Casula Powerhouse, “a site specific meditation on the pursuit of absence.” Ryan’s work is a kind of minimal video. His Crash Media is currently touring New Zealand in the show Dirty Pixels. Ryan says the new piece, Future Proof, is concerned with ideas of obsolescence in the digital age.”[I]n this work I use defunct and faulty video technology to de-construct analogue footage.” Future Proof will show in Digital Decoupage in December, and, with Donat’s Bathing in A Warm Glow of Nothing will also be exhibited in Brainfeed at the Penrith Regional Gallery and Lewers’ Bequest, Oct 5-Nov 30.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 39

© Linda Wallace; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

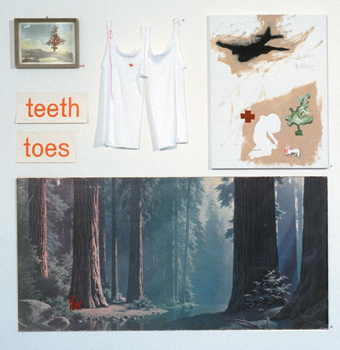

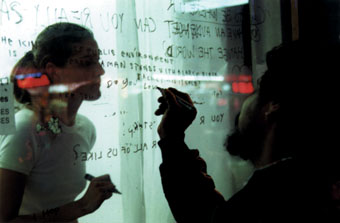

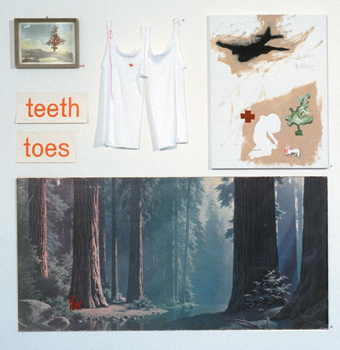

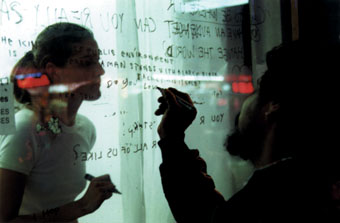

Sebastian Moody from 100% expression

In the text-based practice of Brisbane emerging artist Sebastian Moody there is a consistent concern with viewers and their reactions. With gestures both grand (such as the imposing statement “BUILT UNDER THE SUN” at Brisbane’s South Bank) and slight (the text “Primal man craves fire‚” posted in newspaper personal classifieds), Moody continually seeks a response, and considers each a little victory. However the response Moody seeks is never specific as his text works are fragmented, ambiguous and their precise intent continually debateable. What is important then, when encountering Moody’s work among the city’s landscape of advertising slogans, is the priceless freedom of choice that they wish to provide. In his most recent exhibition Generation: Point, Click, Drag, produced collaboratively with Craig Walsh as part of Moody’s 2003 Youth Arts Queensland Mentoring Program, the significance of the viewer’s response was again highlighted. Presenting gas masks and body bags emblazoned with the Nike logo, Walsh and Moody questioned the legitimacy of the audience’s, and also their own, ideological freedom within contemporary historical, social and economic contexts and the War on Iraq. Linking recreational sport and the war on terror, the show suggested the game of our current condition and the possibility that only a finite set of choices and responses exists. This gesture, intending to provoke a response, was not however predetermined as perhaps the response which commodity slogans endorse or games sanction. Rather, in his practice Moody seems to continually seek to conserve the reader’s free will in this increasingly authoritarian society.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 39

© Sally Brand; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Like Camilla Hannan, Thembi Soddell is a grit/throb/atmosphere artist whose compositions featured in the early work of RMIT’s ((tRansMIT)) collective, helping to establish the Liquid Architecture festival. Where Hannan’s sound and installation work often has a cinematic, foley quality, laid out within spacious, hissy caverns (eg 4-Way Dam in 360 degrees: Women in sound, 2003), Soddell’s is arguably more abstract and mysterious. Her most recent piece—the superb installation Intimacy (also in 360 degrees)—was characterised by sudden jumps and cut-offs in sound, stochastic drop-outs in volume which revealed, on subsequent listening, a pre-existing subtext of sound now rising within the mix. The setting of Intimacy within a dark, claustrophobic alcove, bordered by heavy, red felt curtains, exaggerated its erotic and, at times, genuinely frightening trajectories. Soddell’s CV reveals her particular interest in the subconscious, psychological transformation of sound and space, which she prompts in the listener using processed field recordings and by exploring thresholds of perception. From an apparently ‘silent’ audio space comes a terrifying point of sound which then vanishes before it reaches such a conclusion that allows tension to be released. Although Intimacy represents the summit of this approach, Soddell has been moving towards it in pieces featured in the Document 03-Diffuse compilation (Dorobo, 2001) and the gallery showing and recording Gating (West Space, 2002). In her frightening fluxion between the organic (processed water sounds, air, etc) and the electronic, Soddell incites tense listening.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 37

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

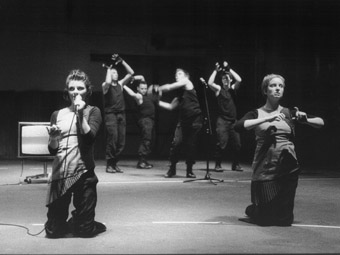

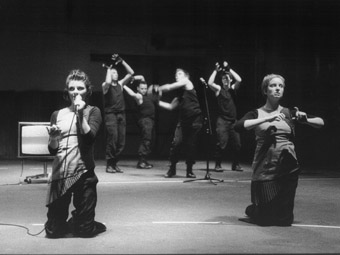

SacredCOW (Dawn Albinger, Scotia Monkivitch and Julie Robson) The Quivering

photo Suzon Fuks

SacredCOW (Dawn Albinger, Scotia Monkivitch and Julie Robson) The Quivering

SacredCOW (Dawn Albinger, Scotia Monkivitch and Julie Robson) is a Brisbane-based theatre ensemble that formed in 2000 to devise adventurous performance with strong physical and sonic scores. As they explain, “While touring and salsa dancing in the wild zones of Colombia, we dared each other to work together for 30 years.” And they’ve taken the dare seriously by establishing clear long term aims and direction for sustaining their fruitful collaboration. Inspired by “divas, lamenters, lullaby-makers and monsters”, SacredCOW became part of the Brisbane Powerhouse Centre for Live Arts’ Incubator program, designed to support local artists working on long-term laboratory style training and performance building. From here, the ensemble worked with Sydney-based director Nikki Heywood to devise The Quivering: a matter of life and death. SacredCOW’s creative partnership for The Quivering has since grown to involve Mount Olivet Hospice and the Creative Industries of Queensland University of Technology. With a history of assistance from Arts Queensland, the Australia Council and Playworks, The Quivering is scheduled for full production and a 2-week season at the Brisbane Powerhouse in November 2003. SacredCOW are also co-founding members of Magdalena Australia, part of an international network of women in theatre, and were coordinators for the recent International Magdalena Australia Festival in Brisbane.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 34

© Mary Ann Hunter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Frances Rings is an experienced dancer who is now emerging as a significant choreographer. She joined Bangarra Dance Theatre after graduating from NAISDA in 1993, 2 years after Stephen Page became artistic director. She performed in Page’s first full-length work, Praying Mantis Dreaming, and has continued to dance with the company, developing a remarkable onstage partnership with the late Russell Page. In 1995 she studied at Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, an experience that has strongly influenced her dancing and choreography. Ring’s first major choreographic work was Rations for the 2002 Bangarra double bill Walkabout, a narrative piece including an inventive use of props. Her pieces in the recent Bangarra work Bush were standouts: Slither, Stick and her own solo, Passing. Clear and inventive choreographic themes combined with traditional subjects in Slither and Stick, the latter featured a very effective use of stilt-like props, while Passing read as a moving eulogy for her former dance partner. As artistic director, Stephen Page encourages his dancers to develop their choreographic skills and this is evident in the opportunities he has given both Rings and Albert David. Rings has 2 major choreographic projects lined up for the coming year and is clearly keen to continue developing her craft both inside and beyond the Bangarra fold.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 34

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

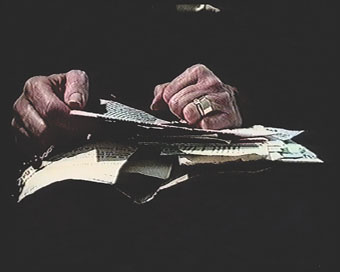

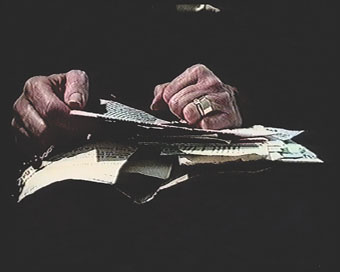

Rainer Mora Mathews, Dead Lions

Rainer Mora Mathews has exhibited as a cartoonist since he was 10. Now in his late 20s, he’s been working on Dead Lions (from the verse in Ecclesiastes: “for a living dog is better than a dead lion. For the living know that they shall die, but the dead know not anything”) for several years. It’s extraordinarily ambitious: a 300-page investigation of how we relate to our ancestors. The narrative stems from Mora Mathews’ fascination with his own ancestry: the experiences of his father’s family as Jewish Holocaust survivors and his mother’s Australian forebears’ role in removing Aboriginal people from their land.

Woven into this narrative is a series of archetypal myths from the Jewish and Western European tradition that reflect on ancestral relations. The comic form, which is a key creative paradigm for Mora Mathews (“this is not a novel nor a storyboard for a film”) enables a visual progression through which the ancestors or ‘dead lions’ take shape in the background, becomingly increasingly involved with the ‘live’ action in the foreground. This isn’t visual philosophy of the ‘Freud for Beginners’ variety but the telling of stories in ways that elicit philosophical reflection. The fusion is understandable. Mora Mathews’ mother, Freya Mathews, is one of Australia’s leading eco-philosophers. His father, Philippe Mora, the filmmaker, once drew comics, and his grandmother, Mirka Mora’s paintings seem strongly influenced by the comic form. Rainer Mora Mathews has hibernated north of Bendigo for the past 6 months, finishing his opus. Dead Lions is an epic of the Euro-Australian experience.

–

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 34

© Richard Murphet; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Pseudo Sound Project is an experimental fusion of DIY technology within performance initiated by SA-based media artist and event-architect Kristian Thomas. PSP has evolved over the last few years in a progression of rooftop performances, clubs, artist-run galleries, festivals and master classes, in collaboration with local and internationally-based video artists and musicians. With a love for the techno-aesthetic, Thomas’ performances are obscure and bombastic, slipping between glitch-pop, the moving image, hardcore electronica and rhythmic nature sampling. With a wide variety of electronic video and audio artists invited to PSP events, Thomas’ performances are chaotic, sublime and often grating, impressing upon his audiences a predilection for real-time experiences bordering on the spiritual. As a travelling performance sphere, the techno-playground of Thomas’ iconic mobile icosahedron rig stands in sharp relief against natural backdrops, yet with an obvious reverence for the chosen landscape. Nature themes have figured prominently within many PSP festivals and shows, with PSP no 8 featuring the successful planting of 1000 native trees. Pseudo Space is an interactive gallery and shop set up by Thomas and his partner Kerry Scarvelis, a cool-hunting nu-fashion designer. Pseudo Space is a home base for PSP events, outlet for local moving art, electronica and emerging designers. It’s also the sole distribution point for Thomas’ unusual beer recipes. Blends such as VegieGarden–a wheat beer with coriander and orange–notorious to the regular patrons of Pseudo Space opening nights, has recently caught the interest of brewers and local café owners. With a smattering of Epicureanism and an ardour for all things glitchy, Pseudo Space has added some vigour to the quickening pulse of experimental art, design and hospitality in South Australia.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 33

© Samara Mitchell; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Compared critically with brilliant artists DJ Shadow, The Beastie Boys, Tricky and David Lynch, The New Pollutants are making a big impact on the live arts scene in Adelaide and beyond. Featuring the talents of Benjamin Speed aka Mr Speed (vocals), and Tyson Hopprich aka DJ Tr!p (the 8-bit Wonder), The New Pollutants are intellectual hip-hop with an experimental edge. These guys have their own sound, it’s global and it’s local and it has evolved from who these artists are. In this sense, the experience of their work is intimate, leaving their audiences gasping—for air and for more! The New Pollutants recently

released their independent EP at Minke Bar in Adelaide—Urban Professional Nightmares, following their critically acclaimed debut album Hygene Atoms. These guys take lo-tech augmentation to the extreme, using the obsolete Commodore 64 S.I.D. Chip soundcard in the bedroom studio. The resulting sound is altered, embracing lo-fi technology with a familiar flavour. The New Pollutants are best experienced live, where the sensory atmosphere is addictive and the beats are phat. The live experience integrates visual experiments with original sound and a theatrical, interactive edge. The New Pollutants produce an honest sound with grounded ideas driving the creation of their work. There’s no doubt these guys are going to be huge, but only as huge as they want to be.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 33

© Rachel Kent; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Rachael Guy, Doughboys

Over the past decade Rachael Guy has worked across several disciplines. Formally trained as a visual artist, her voice has been in demand in contemporary music theatre circles and she has been a soloist in Ihos Opera productions. Writing is another passion. For a long time Guy has wanted to create a body of work that incorporates all these practices. She began exploring the concept of adult puppetry and in 1999 produced a series of erotic dolls with highly detailed porcelain heads and hand stitched lingerie bodies. Disquieting and fascinating to look at, these little figures became conduits for Guy's themes of transgression, appetite and ambiguity. Seeing them in an installation, or being held or regarded by people (usually with a mixture of curiosity, revulsion and humour), gave her the idea for Torrington’s Buttons, a solo show which will lie somewhere between performance art and theatre. The piece provides a vehicle through which Guy explores her experience as an adolescent, grappling with a sense of acute isolation in the suburbs of Launceston and how she dealt with this by forming an intense emotional and imaginative attachment to a deceased sailor (a member of the Franklin Expedition to find the Northwest Passage in 1845-8). In 1986, the perfectly preserved remains of the young sailor, John Torrington, were exhumed from permafrost. His image appeared in the media and struck a profound emotional chord with Rachel Guy during a difficult adolescent period. She intends to tell this story of adolescent love survival through a theatre work that combines narrative, song and puppetry in a minimal theatrical setting.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 33

© Susanne Kennedy; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

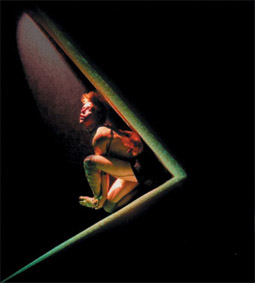

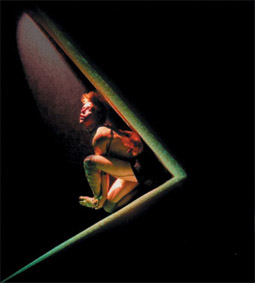

Ninian Donald The Obcell

photo Mark Gordon, Garry Barnes

Ninian Donald The Obcell

Fiona Malone’s career is a model of multi-skilling . She’s worked in Australia and Europe in all manner of dance forms from folkloric to dance theatre to movement research with an abiding interest in live multimedia performance. Before joining the Australian Dance Theatre in 2000, she toured Europe for 5 years with Belgian multimedia dance and technology company, Charleroi Dansers directed by Frederic Flamand. Last year, as well as being nominated in the Outstanding Female Dancer category at the Australian Dance Awards for her performance in the ADT’s The Age of Unbeauty, Fiona presented her site-specific work Bamboo Bathing at the Contemporary Art Centre of SA. Recently she spent a month in Birmingham as part of the DanceExchange program working with choreographers Henry Oguike and Akram Khan on the research and development of new ideas and movement.

This year Fiona was awarded an Australian Choreographic Centre fellowship to develop The Obcell, an interactive dance/theatre/multi-media performance addressing issues of human testing, manipulation and solitary confinement. The dancer wears the Diem Dance System, a new sensor-based technology designed for the use of dancers and composers at the Danish Institute of Electro-acoustic Music. Stage 1 of The Obcell was presented in the Risky Manoeuvres season at Canberra Theatre Centre earlier this year. In September, Stage 2 manifest as a collaboration between Malone and 4Bux:Progressive Arts, another multi-faceted Adelaide outfit. Performed by Ninian Donald with sound and technology by Peter Nielsen and dramaturgical input from director-designer Ross Ganf, early response suggests that while the themes of The Obcell need some refinement, the use of multimedia in live performance makes this a team to watch.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 33

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Stephanie Lake

photo Virginia Cummins

Stephanie Lake

Melbourne has been a centre for muscular, bony and often violently articulated choreography. Stephanie Lake is not new to this scene. She has danced for Phillip Adams (balletlab), Lucy Guerin, and Gideon Obarzanek (Chunky Move), and the influence of all 3 choreographers can be seen in her own pieces. Now that the physical characteristics of this trend within Melbourne dance have become fairly well defined, there has been a return to theatricality amongst such practitioners and it is here that Lake’s distinctiveness is most apparent. Her work is closest to Adams’ in its movement style and dramatic, violent energies, but if Adams’ dramaturgy is as much defined by the juxtaposition of theatrical ideas and elements as by anything else, then his is arguably a non-aesthetic, rather than a style per se. As such, this broad field of dance leaves plenty of room for Lake to invent her own mad imagery and strangely funny, off-kilter scenarios. Lake’s full-length work Love is the Cause (2001) represents the summit of her independent career to date, while her short study The Loop was the highlight of Chunky Move’s recent Three’s a Crowd program (2003) and exhibited considerable potential for development in its wryly angular, contemporary ballet. Lake has also collaborated with James Brennan on his staged events (namely Piglet, 2001). In the spaces between theatre and dance, surreal comedy and the avant-garde, Stephanie Lake has emerged as an important and invigorating new artist.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 32

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

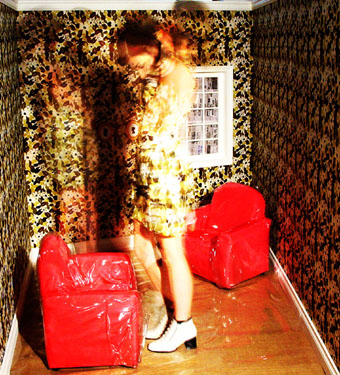

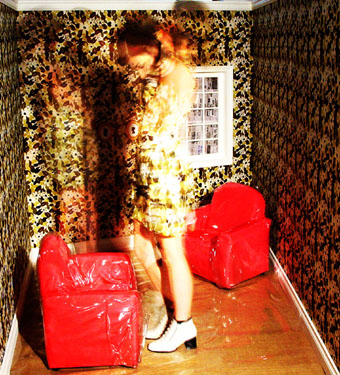

Anna Tregloan

It is apt that, among other projects, theatre-maker Anna Tregloan is adapting the writing of Borges. Like Tregloan, he often employed spatial devices as metaphors for social, philosophical and literary ambiguities: a map so detailed that it covered the landscape it represented, the library as labyrinth. Tregloan’s most recent piece is the still-embryonic performance installation, The Long Slow Death of a Porn Star. Along with design commissions ftom Danceworks, Circus Oz and The Three Interiors of Lola Strong, Tregloan has been devising her own installation-like productions such as Mach (2000) and Skinflick (2001). LSDPS is partly a sequel to the latter, in that both employed a series of voyeuristic scenarios to produce wonder, unease, discomfort, pleasure and seduction. Context and conjunction produce the theatrical content here.

In Skinflick the audience charmingly and somewhat vulnerably observed the performance at eye level, with their heads extending to the height of the stage from beneath the rostra. The staging of LSDPS was less restrictive–the performance had no formal beginning or end, offering spectators several linked spaces to traverse, or rest within. At the top of a staircase, beyond a tight hallway, and through a doorway draped with bordello-esque beads, lay a snug viewing hall peppered with mounted illustrations. At the other end sat a foreshortened recreation of a 1950s/60s chic domestic interior. To one side lay a small, white room containing a mounted crayon, endlessly describing a circle. In the hall before entering, a sign signalled that all objects were for sale, with a description and price of each. Art as stylish sexual commerce.

Within the toy-like domestic annex, 2 women–saturated with a sublime ennui-idly posed, gazed vacantly outwards, or collapsed in upon themselves and 2 little chairs. Much of the ‘action’ was provided by David Franzke’s gently scorifying, contemporary musique concrète score, composed of sounds of breath, inflation, deflation, moans, crackles, laughter and something akin to male masturbation.

It has been argued that pornography is inherently avant-garde because, to infuse viewers with feelings of masculine potency, pornographers strive to represent female orgasm, allowing the viewer to fantasise that he has produced this reaction in the subject of his gaze. Femal orgasm is however impossible to satisfactorily represent visibly or audibly. Despite the apparent explicitness of pornography, what makes something pornographic is in fact precisely what remains forever absent but alluded to within pornography itself. Tregloan’s interaction with and referencing of pornography (presented in a book available within the performance space) was not particularly satisfactory, but in producing this sense of pornographic absence, both Skinflick and her newer project were wonderful successes. Sex is never visible in Tregloan’s works, but it is one of the themes she virtuosically recreates through staging an absence of overt action, associated with a dark, explicitly voyeuristic audience relationship. Her circle-drawing machine was, in this context, the quintessential pornographic object, its aesthetic frottage terminally spirally around issues of sex and the feminine grotesque.

The Long Slow Death of a Porn Star—The prequel, director/designer/concept Anna Tregloan, performers Caroline Lee, Victoria Huff, music/sound David Franzke, Hush Hush Gallery, July 23-25

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 40

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Video was one of the strongest components in the recent showing of Helen Lempriere Travelling Art Scholarship 2003 finalists at Sydney’s Artspace. In his finely shot and beautifully edited Pablo Velasquez Shoeboard Remix, Matthew Tumbers’ anonymous protagonist does everything you’d like to do with a skateboard— without actually using one. Feet skid assuredly across surfaces, the body twists and glides with the trademark crouch and angularity, the camera goes closeup on the virtuoso ride. Is this for real? Tumbers writes that his video “mimics and parodies a form, namely skateboard manoeuvers with elements of ‘street dance’, creating a fictional form that could well be real and achievable.” It’s pretty convincing, but the pleasure beyond surprise is in the dexterity of the very making. It’s a witty variation on other skateboard videos doing the rounds. Tumbers is a COFA graduate who has exhibited solo at Block and TAP galleries and whose Gumnut Xanadu 3: Expanding Conglomerates opens soon at Kudos Gallery.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 31

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jane McKernan is best known for her work as one of The Fondue Set, which she founded with Elizabeth Ryan and Emma Saunders in 2000. McKernan’s solos work in a more subtle register, still confronting the audience but drawing us in to share delicate observations and actions. She performed in Mobile States last year in a powerful solo, I Was Here and took the ideas behind this piece to Dancehouse in July this year where she performed an improvisation at Dance Card, an informal season featuring 5 dancers each week. She also appeared with Eleanor Brickhill in Waiting to Breath Out at Antistatic 2002, at Performance Space in Sydney. McKernan currently has “a Sigourney Weaver thing” and is developing a piece with Lizzie Thomson called Working Girl.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 31

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jodi Smith is a writer, photographer and filmmaker whose video Redux? Part 1 was in the recent showing of Helen Lempriere Travelling Art Scholarship 2003 finalists at Sydney’s Artspace. After working in Australia, New Zealand and the US as a camera assistant on such films as The Matrix, Smith has been accepted to study for an MA in Fine Art at The Slade School of Fine Art in London where she hopes to make a feature length film. Redux? Part 1 plays engagingly with our knowledge of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now and the constellation of masculine values that gravitate relentlessly around it. Smith remakes the first 6 minutes of the film, blending the original with carefully constructed scenes that mimic it closely but with a different protagonist—a woman. The effect is much more surprising and enduring than you’d first imagine. Smith writes, “Over the last year I have been dealing with the history of war and specifically how gender roles both define and are defined by war. A key issue within my filmmaking practice is the issue of female subjectivity—particularly the lack of it within the cinema and how this is a reflection of first world society.”

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 31

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

I remember the video as intensely coloured and almost hallucinogenic in its rainbow effects. The idea of someone videotaping the sun has a pathos and strange logic that is a defining feature of Kajio’s work. Often an intensely colourful and multi sensory experience, Kajio’s work uses heightened video colour effects or coloured light reflections. In her 2002 exhibition Forest of Invisible Waves, at the Contemporary Art Centre of SA, installation components such as water showers, acrylic rods and mirrors were used to create an immersive space of reflected and multidirectional projected light. Sound was used throughout the space, further dislocating reality. Kajio writes, “Reality is not something that is perceived directly…My work usually plays on this abstraction or distortion to create a kind of space between the viewer and my piece, in which they can experience an alternative ‘reality’.” In 2003 Kajio curated Electtroni Nessun Senso, at Downtown Art Space. In her work for this exhibition projected light swims up the walls, LCD lights are refracted through a glass fish bowl with oxygen bubbler. One interpretation (there are several) of the exhibition title is “electrons with no sense of direction.” Yoko Kajio was born in Kyoto, Japan. Since graduating from the South Australian School of Art in 2000 she has exhibited in Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, CACSA, the Physics Room and the Experimental Art Foundation. Kajio has also been a core member of performance art group shimmeeshok since 1998.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 31

© Bridget Currie; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Sally Rees, video still, The Groove, 2003

Matt Warren is a multimedia artist who creates work for solo shows and collaborative pieces for performance installation and theatre. Awarded a Samstag scholarship in 1999, he completed a MFA at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. He is currently a recipient of an Australia Council New Media Arts Board grant. Warren has recently returned from 8 weeks research in Germany and a grant from Arts Tasmania has enabled him to also work in the Czech Republic where he collaborated with a performance poet and an electro-acoustic composer to produce a performance installation for the Cultural Exchange Station total recall festival. Warren’s work has evolved from his initial explorations around the concept of absence, culminating in on the run (2002). His current concerns are exploring the ideas inherent in transcendence, the sublime and the supernatural. Sally Rees is a pop music fan who incorporates single channel video and installation in works that use autobiography and self-portraiture. Her recent video The Groove (2003) and research focus on popular culture through exploring the emotional investment of its consumer audience. Rees’ developing practice includes a newly discovered capacity to perform in her video projects. She aims to move beyond the constraints of the rectangular screen and develop richer ways of using and viewing the medium. Rees collaborated with Matt Warren on the theatre piece Pop for IHOS Experimental Theatre Laboratory in 2002.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 31

© Sue Moss; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Here is a new event on its second outing, and of major significance for Australian live art/performance art. The intensification of the relationship between Australian and international performance scenes is building rapidly with the emergence of Time_Place_Space (see page 28), the Performance Space-PICA-Arnolfini (Bristol, UK) Breathing Space connection, and the visits of Blast Theory (2002) and Forced Entertainment (2004 Adelaide Festival). The welcome consolidation of this rich pattern of exchange is more than evident in The National Review of Live Art Midland, Perth’s international festival dedicated to the presentation and exploration of live art practice. Established in 2002, the NRLA Midland is a collaboration between the City of Swan and New Moves International (UK), producers of NRLA Glasgow, Europe’s longest running and most influential festival of Live Art.

This will be an unconventional festival, with works that will take you beyond the niceties of neat timetabling into the time-space loop of durational performances and installations offering contemplative experiences, new ways of regarding the body, movement and issues of the moment. The program includes Hideyuki Sawayanagi (Japan); sculptor and performance artist Richard Layzell (UK), also conducting workshops; Dutch choreographer Angelika Oei and sculptor RA Verouden (with <> “in which a spinning dancer causes notions of time to vanish”), lone twin (UK) and Alastair MacLennan (UK, Professor of Fine Art at the University of Ulster) in a 5-day durational performance/ installation. With Edith Cowan University's School of Contemporary Arts, NRLA Midland 2003 has also commissioned new works by Perdita Phillips, Gregory Pryor, Domenico de Clario, cAVity, Lyndal Jones and Geoff Overhew and Singaporean artist Chandrasekaran. Nikki Milican, Artistic Director of New Moves International, will be on hand as will Mary Brennan, courageous and incisive dance and live art critic for the Glasgow Herald, conducting a workshop with local writers.

Midland Railway Workshops, Oct 22-26

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 30

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Inside the Angel House (scheduled for a short season in November) is a new multimedia performance being developed by Theatre of Speed, a group of young performers with disabilities, as part of the Geelong-based Back to Back Theatre’s workshop program. The workshops, led by director Marcia Ferguson and animator/filmmaker Rhian Hinkley, are focused on the skill development in performance, improvisation, animation and photography. Just before he left with Back to Back for their European tour—he created the projected imagery that surrounded audience and players so powerfully in Soft—Hinkley wrote, “Theatre of Speed is an amazing opportunity to work with some of the most innovative and creative artists in Australia. The work that these guys create is unlike any other. I received a research grant from the Australia Council New Media Arts Board which has allowed me to spend more time with the group than I previously would have and to investigate the production of graphics and video that recreate Downs Syndrome…not as an actual representation of the syndrome, rather as an indication of the creative possibilities and benefits that genetic abnormalities can produce. The actors have had a chance to look at and use some great new technology which has been really exciting for all of us: a large Wacom tablet, a new G4 laptop, video projector, large screen TV, DVD players and burners. The actors take to new technology without any fear or preconceptions; this leads to really exciting levels of development that other groups don’t reach.

“The Wacom was really excellent for a number of reasons. Firstly, the actors loved the concept of being able to draw in multiple colours and with different brushes while using the same pen. Also the concept of filling areas in with a single click was something that really excited them. Another interesting element was the handwriting recognition with Wacom and OSX. This produced some really interesting translations and with a simple Applescript program I could make the computer translate their writings and then read it back in a number of voices.

“In producing the animations we used 2 processes. The first is hands-on, direct input and control by the actors. In this scenario the actors devise, create and animate the work. We did everything from basic cut-out and puppetry, from scratch animation directly on 16mm film to Flash from drawn animations. This produces raw and energetic pieces that are unpredictable and follow unique paths designated by the actors.

“The second process was to use myself as a tool and let the actors create works as directors or collaborators, giving them access to the full power of the technology. By directing me to make changes to their work or to create things for them we could work in 3D, and use software that is normally too complex to pick up within a short timespan. This resulted in works that have a slicker edge …but still retain the orginality of concept and direction.”

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 30

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

A graduate of the Canberra Institute of the Arts (ANU), Somaya Langley is a composer, instrumentalist and digital artist. She also collaborates as radio presenter and producer on Therapy, the national electronica show on 2XX FM. Her interactive work, Disjointed Worlds (2000) is an email fiction that gently plots the psychic space between separated lovers. As a composer she ranges ably and inventively across acoustic, electroacoustic and digital domains. Langley is part of the HyperSense project (with Alistair Riddell and Simon Burton), who perform compositions in wearable flex sensor suits. The group recently appeared on ABC FM’s New Music Australia.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 30

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Chi Vu

photo Ponch Hawkes

Chi Vu

Migrant writing, as Sneja Gunew pointed out some years ago, is often shaped by nostalgia, that psychic force that requires the subject to return repeatedly to the place of origin in the hope of recovering an identity that connects body, self and homeland. For the child of migrants, or those whose own memories are immature, the remembered country is secondhand, more or less a product of their parents’ nostalgia. If she returns to that place as an adult visitor, she must put together the childhood stories lived on the inside with a jumble of new languages, rhythms and sights that represent a different outside.

The premise of Vietnam: a psychic guide is that Vietnam can only be an imaginary location, as seen through the eyes of a young Vietnamese-Australian woman writing postcards back ‘home’ to Australia. “The journey of importance is not the physical one. The real journey is in the heart and in the mind.” Written backwards in a strange red book that becomes her tourist guide, this instruction is given to Chi Vu by a postcard seller. Her departures, her returns, from the City of Lakes, Halong Bay, Café of Babel, Hanoi or the City of Face generate poetic rhapsodies that attempt to capture fleeting impressions, to take snapshots or make song like the melodic tune of the plain brown birds. Indeed this performance began as a series of prose poems published in Meanjin. Although now in a stylish theatrical production complete with multimedia projections, the vignette-like format remains as the postcards are delivered–winged through the air by 2 chorus members at the beginning of each scene. Received by her father, played by older Vietnamese actor Tam Phan, and Jodee Murphy, as best friend Kim, Chi Vu herself appears as the narrator or as other kinds of cultural transmitter-postcard seller, motorbike rider, train traveller, café customer. Through them she carries the action—of discovery and excitement—whereas the other characters re-enact this different Vietnam, or with Murphy’s mime-dance style, animate the sensations of this new world.

In this committed bilingual performance, I enjoyed the musical, sometimes competing, layers of Vietnamese and English particularly when Tam Phan sings like an old crooner in both languages. A Vietnamese spectator noted that the Vietnamese was antiquated, far from the contemporary mix of North-South dialects and popular expression one hears in postmodern Vietnam. Perhaps the script reflects the proper speech of translator Ton That Quynh Du—also a long-term Australian resident—or that of the older male actor and thus its linguistics stand in for the 1950s voice of the father that Chi Vu knows. Rather than visiting a new Vietnam, it seems that the text oddly revives a traditional symbolic order.

By way of contrast, the computer graphics (Ruth Fleishman) project abstracted images of ponds, birdcages, or Oriental architectures as iconic shapes that slide up or down or open like barn doors. They flatten the landscape, leaving more space for the gap between a Vietnam lost and a Vietnam reconstructed to appear. This place remains overly idealised, and although we witness a momentary electrocution and the old man swallowing papers, it is difficult to locate this trauma either in her father’s history or in the young traveller’s streetscape.

While there is much experimentation with form, the performance never breaks from the circuit of nostalgia. Its structural repetitions give us too many beginnings and the endings tail away. I wonder if more speed or intensity could be accumulated by seeing where one image collides with another or whether the messages from Vietnam could psychically and physically disrupt the neat separation of ‘home and away.’ As a writer Chi Vu commands a delicate poetic register but this production makes me think that for each generation of migrant experience, the Greeks and Italians in the 1980s or the Vietnamese in 2000, the pleasure of returning might always be left in deficit rather than in credit. Particularly unless writing becomes a theatre of the present.

Chi Vu, Vietnam: a psychic guide, text Chi Vu, director Sandra Long, North Melbourne Town Hall, Aug 22-31

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 30

© Rachel Kent; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

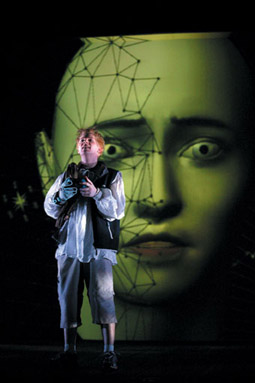

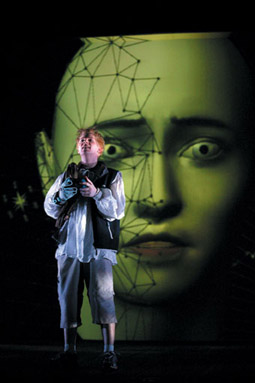

Cameron Goodall, The Snow Queen

photo Tony Lewis

Cameron Goodall, The Snow Queen

Windmill Performing Arts is an important new Adelaide-based national venture with international ambitions. The company’s Creative Producer Cate Fowler has had a long and significant history of creating and developing festivals and performances for young people in Australia. Fowler expertly brings together different creative teams for each of the company’s productions. The latest is a version of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snow Queen celebrating the 200th anniversary of the writer’s birth. The concept for the show came from Wojciech Pisarek, the creator of the show’s virtual world, who writes, “The Snow Queen is a ruler of virtual reality and computer games rather than snow, frost and ice. We show 2 journeys and 2 different ways of gaining experience and knowledge. Gerda goes through the real world, Kay [a boy] through the virtual. It is not about which one is better, it is about a balance between them.” Based on his PhD research at Flinders University (see RT#52, p32 for a detailed account), “5 years of experimentation”, Pisarek says, “are to be tested for the first time in a commercial theatre production. The Snow Queen character is purely digital. Some characters will have both physical and virtual representation. All the 3D characters and the digital environment will run in real time–nothing is pre-recorded.” Pisarek describes this as “a scary exercise–we will have 2 independent computer set-ups to run the show, in case one crashes.” The Snow Queen is directed by Julian Meyrick, written by Verity Laughton, designed by Eamon D’Arcy and Mark Thompson, with music by Darren Verhagen. The eagerness of Windmill to engage with new technologies in works for new audiences is a sign of a healthy embrace of innovation.

The Snow Queen, Adelaide Sep 26-Oct 4; Sydney, Apr 22-May 9 2004

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 29

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Anita Johnson, Underland

Brisbane-based Anita Johnson is a multi-disciplinary artist working with new and old media. With a background in graffiti, illustration and music videos, she has been integrating these formal and vandal art styles into contemporary and interactive videogame technologies. Curious about “faerytale vs impossiblity”, her work “re-contextualises (un)familiar fragments into virtual (3D) pop culture nightmares and wonderlandesque daydreams.” In June 2003, she participated in a candy-themed residency in Canada, where she began development of the first in her Underland series, an immersive 3D adaptation of Hansel and Gretel. Underland is currently being developed into an online 3D environment filled with secret lands; the next instalment will be launched in early October, 2003. Johnson is temporarily based at The Banff Centre, in Canada, where she is collaborating with a team to develop educational science toys.

http://anitafontaine.com/content/

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 29

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Multi/inter/cross/hybrid are notions that intrigue and drive the work of Brisbane-based artist Luke Jaaniste. Having explored and experimented with diverse artforms, contexts and media since graduating in musicology from the Queensland Conservatorium in 1999, Jaaniste’s practice traverses the fields of sound installation, performance and public art. He has created work for concert hall, radio, CD, gallery, theatre, public sites and festivals using a broad range of materials including acoustic instruments, digital media, text, video, found objects, sculpture and the human body. Recent works have been presented at Small Black Box, a sonic performance event at the Institute of Modern Arts, and the Datum Video Show at Metro Arts. Jaaniste also co-directs the national composers group COMPOST, collaborates with Julian Day as juaanellii, and is currently Composer Affiliate with the Queensland Orchestra. The idea of space is central to Jaaniste’s PhD research in Creative Industries at QUT, which he began this year. “My key term at the moment is ‘making space’: physical, sensory, corporeal space, and cultural or communal space. Not ‘filling space’, which is a compositional notion (image within a frame, sculpture in a space, plot within a story, words on a page) but something more positional in actually composing the frame.” Jaaniste extends this approach to making space in his public and corporate work and in his many advisory roles in the industry: “I really enjoy thinking and discussing and planning on a policy development and ‘big picture’ level, and see that part of my future practice will be teaming up with others to make space for artistic practice to grow and flourish.”

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 44

© May Ann Hunter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Looking around and not really knowing where to find new documentary filmmakers (even though, I realise now, they’re all around us, except I don’t always think of them in that way—new/old etc—I mean, does that really matter?) I’m introduced fortuitously to a new series of half-hour documentaries on SBS called Inside Australia. All new directors, several with little or no broadcast or filmmaking experience, and a determined push to put them up the front of the schedule—7pm on a Sunday. What could be better? Let’s see…

Meet George from Aurora Scheelings’ The Trouble with George (the first film on the schedule) except he’s not really trouble, he’s a delight, albeit maddening, infuriating, a handful, 2 handfuls even. George is 81 with the mental age of a small child. Brian finds him living in a bus shelter so he takes him home to his wife, Jennifer, and they look after him. Now, several years on, Brian and Jennifer have parted but Jennifer is still caring for George. “Why?” you might ask, as this film does. George is a character but you know he’s hard work-imagine an irascible old man with a toddler’s temperament-although you can also see why he’s still with Jennifer after all this time. It’s an unusual relationship, partly mother/child but also one of companionship and mutual need, an irresistible emotional call and response. The film’s strength is that it makes sense of it all without wrapping it up too neatly–in the end, we don’t really know what will happen to George and Jennifer but that’s okay.

In Me Me Me and ADHD, directed by Shelley Matulick, Ben is a 21-year old with, that’s right, ADHD—he’s practically bouncing off the insides of my TV, so much energy pouring down the tube. Not that Ben is going down the tube, he’s right there dead centre—I mean, of course, there’s a documentary being made about him-who else? His family are there too, although rather more battle weary and circumspect. They don’t really come alive to the same degree as Ben but that would be hard to do anyway (only the boy who lives down the road, also diagnosed with ADHD, comes close). The film works because it doesn’t try to airbrush ADHD but manages, mainly, to show what it’s like to live with it on both sides, inside and out.

Disturbing Dust (director Tosca Looby) is a very ordinary story in that it is about a woman, Robyn Unger, dying of cancer, an everyday occurrence for somebody, somewhere, and something that is oddly banal for all its awfulness. In this instance, Robyn has mesothelioma, which she contracted as a result of handling asbestos sheeting 25 years earlier. There’s understandable anger that an activity as innocent and matter-of-fact as building a house should lead to such painful consequences decades later, but it’s to the credit of everybody involved that this outrage doesn’t obscure the central, inevitable process of somebody dying with whatever dignity is allowed. In one scene, Robyn farewells her work colleagues who, watch wide-eyed and dumbfounded by what’s happening, even as Robyn chats matter-of-factly about her cancer. At times, Robyn and her husband, Peter, appear incongruously cheery as they prepare for death, in the manner of people trying to jolly themselves along in the midst of great pain because the alternative doesn’t bear thinking about.

There’s nothing lightweight about these topics and the rest of Inside Australia promises more of the same but on the evidence of the first 3 episodes, the effect is undeniably positive. It’s continually amazing–what people can do—and this is something the directors all seem to recognise and value. The episodes are pacey and taut as befits a half hour slot, no gradual unfurling or leisurely settling in-the subjects fill the space and the screen and the immediacy is an obvious counterpart to the intimacy between the directors and their protagonists. The filmmakers are savvy, as are the subjects.

Obviously, in half an hour, there are going to be elisions and lacunae–you sense there must be more to George and Ben and Robyn and their situations (there are hints of this in the films anyway)—but I guess we’re mature enough now in our viewing to understand that this is television and half an hour with these people is far, far better than nothing at all.

The 3 opening episodes, for all their differences, document the pressures of living together today, especially when those pressures are intensified by specific challenges; Inside Australia, in this instance, means indoors, in the family home, and the dramas played out in bedrooms and kitchens. Other episodes promise to take us outdoors, but the focus remains tight-individuals, families, small communities-as if these are the basic units with which to build an understanding.

‘New’ documentary, in this instance, means staying close to home and watching the daily dramas of people trying to get by in the extraordinary everyday. Perhaps these documentaries are a reaction to the seamless gloss of ‘lifestyle’ and faux reality where a simple makeover can seemingly make everything okay. Undoubtedly, too, it’s easier logistically to make these ‘home’ movies, especially for first-time directors. ‘New’ means something well-formed but fresh, a personal engagement that doesn’t necessarily equal ‘SBS documentary’ but ends up there anyway. It takes a fair bit of passion to make documentaries this way-why else would you do it?–but the results speak for themselves.

Inside Australia was commissioned at SBSi by Commissioning Editor Marie Thomas who is upbeat about the state of the documentary as exemplified by the directors in this series: “At the moment I think Australians have every reason to be positive about their industry. I think that it is on the move and we are on the crest of a new wave of creativity. Certainly at SBSi we feel that we have been allowed to renew our remit to invent and change. I sense that the industry is loosening its stays. There are a host of really bright, committed new filmmakers out there-under 35, full of fight, ideas and attitude. Just what an industry needs to thrive.”

Directors mentioned by Thomas as the ‘tip of the iceberg’ (not just new but emerging talent) include Aurora Schellings, Emma Crimmings, Melanie Byres, Zane Lovett, Kate Hampel, Shelley Matulick, Rebecca and Jonathon Heath, Sean Cousins, Tosca Looby, Faramarz K-Rahber and Anthony Mullins and producers Melanie Coombs, Anna Kaplin and Celia Tait.

The challenge now is to ensure that the ‘new wave’ translates into something sustained and sustainable for these directors, with enough impetus, perhaps, to push them toward more, bigger and better projects. Thomas believes that the local documentary scene has been playing it “a bit safe” lately, leaving it to overseas sources to develop new forms and reinvigorate old ones. “Worst of all, this conservatism isn’t bred by lack of funds. That’s fumbling with fig leaves. We’re the cause of it. Filmmakers and broadcasters alike,” she says.

“When I arrived in Australia, I was fresh from the frontline of the terrestrial UK market where a lot of the broadcasters’ time is spent considering who will watch and why, balancing ‘should-be-made’ with ‘it’s-what-they-want’ programming. On my arrival, I was shocked by the ‘bugger ‘em’ attitude towards the viewer that I found amongst filmmakers here. It seemed so counter productive.

“First and foremost, television is a medium that needs to be watched in order to be effective and second, we are dealing with viewers who have been watching television for half century and documentary for longer than that. To assume they can’t make informed choices seems to me to be arrogant. Good ratings don’t equal dumbing down-and yet that was the regular war cry I heard from all around.

“Recently SBSi and the independent sector have been given the thumbs up by the channel’s television management. Ned Lander, Senior Commissioning Editor, and I have been told to give our TV instincts and new ideas a go-ideas that perhaps a year or 2 ago may not have been seen to be fitting or ‘the thing’ for the channel to do. Personally I feel that we are being allowed to open the door to new players and fresh content and being given the opportunity to widen the vernacular of documentary output. From now on, programs can come in different shapes and sizes, as will budgets. We have been given the opportunity to play with light and shade in the schedule.”

Inside Australia isn’t going to change the scenery overnight but it is a good start. Stay tuned.

Inside Australia Sundays 7pm, SBS from October 12

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 16

© Simon Enticknap; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Madeleine Donovan, Bedroom Acrobatics

Madeleine Donovan has performed in several Australian circuses and this year worked with the Womens Circus in Ghosts at the Melbourne Docklands. Her photographs featured in the 2002 Summer Salon at the Centre of Contemporary Photography, Melbourne. Based in Canberra, she is studying honours at the Australian National University School of Art and is a circus and physical theatre trainer/director with Canberra Youth Theatre.

Koky Saly, Untitled, lambda print from series How Much longer Will You Live Like This 2003/2004

Koky Saly is a Melbourne-based photographer who documents her Cambodian community. The series was shown at We Call This Paradise, First Site Gallery, Melbourne in August this year. Saly was awarded the Gabrielle Emma Hayne Memorial Award acquisitive prize for great potential in photographic art in 2002 and in 2001 was named Student of the Year in the Experimental Category by the Victorian Institute of Professional Photography. She is an honours student at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology.

Tamara Dean, from series Friends

In 2003 Tamara Dean’s work was selected for Art and About, an outdoor photographic exhibition of emerging and established artists in Sydney’s Hyde Park–and shortlisted for the 2003 Josephine Urlich Portrait Prize. Based in Sydney, Dean is a staff photographer for The Sydney Morning Herald. Friends was shown in Reportage, Sydney’s annual photojournalism festival, 2001.

David Wills, B3, 18 images of handknitted Bananas in Pyjamas found in Op shops, garage sales and markets

David Wills, from B3, 18 images of handknitted Bananas in Pyjamas found in Op shops, garage sales and markets.

David Wills has had several solo shows, most recently Bird Fancier at First Draft, Sydney 2003. His work has featured in numerous group exhibitions including Amnesty International's Faces of Hope at Womad, Adelaide in 2003 and Proximity at Chrissie Cotter Gallery in 2002. He is studying honours in visual art at the Australian National University, Canberra.

David van Royen, David from series him self, CCP, Melbourne 2002

David van Royen’s clutch, gear and silence series (video and still prints) was exhibited at West Space Gallery in 2002 and features in the latest issue of Photofile. Based in Melbourne, van Royen did an undergraduate diploma and Honours at Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology where he is completing a Masters in media arts.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 35-36

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Every year at this time we survey new work. Since 1999 our focus has been on new media arts both onscreen and performative. For 2003 we’ve taken a bigger, bolder step, selecting over 100 artists from all fields, mostly in their 20s, the majority working in the small to medium arts sector, their work exciting us, our contributing editors and writers. What is striking about these artists is their often direct, sometime provocative engagement with the world, the ease of their deployment of new media and the capacity to generate hybrid practices, and not a few adopt intriguing personae.

Any selection on this scale and across huge distances is necessarily impressionistic, and print space limits the number of new artists, companies, venues and events we can cover. However, beyond the artist/company profiles (a mix of critical appreciations, self-penned biographies and brief reviews) you’ll find more key names in reports on new filmmakers (p15,16), emerging film producers, the Time_Place_Space hybrid performance workshops (p28), and the recently opened Primavera at Sydney’s MCA (p21). Some of the new companies are ventures established by experienced art workers (Windmill, p29), some new works represent a mature artist (like Greg Leong, p29) moving in a new direction. Some regionally-based artists have been included but we’ll survey more in a forthcoming edition.

Although we’re surveying the work of young artists (a remarkably flexible category that has run up to 35 years of age for novelists since the advent of the Vogel Australian Literary Award decades ago) we don’t analyse the impact of youth arts policies as developed by the Australia Council and some state governments. We’ll do that at another time. However, even a casual reading of the artist profiles will tell you that there has been growing support for young artists, not big money but siginificant incentives, like the Australia Council schemes, Write in your face, Start you up, 2 EXCITE-U and Run_way (p24), along with various state government programs, Asialink grants and the many opportunities in film provided by the Australian Film Commission and state-based programs, like the NSW FTO Young Filmmakers Fund. Larger scale opportunities come via the likes of Samstag fellowships (Astra Howard, p14) and the Helen Lempriere Traveling Arts Scholarship (Paul Cordeiro & Clare Healy, p8) which have contributed enormously to the development of young artists. Often young artists gain most support from working with established practitioners in formal or informal mentoring relationships, or by being offered opportunities within companies, for example choreographing for the likes of ADT’s annual Ignition season or as part of the Australian Choreographic Centre program, or through the support of an artists’ collective (Christian Bumbarra Thompson and Boomalli, p40).

Putting SCAN 2003 together has been a challenging and exhilarating task. Thanks to our editors and writers and all the artists who responded to this opportunity to register the breadth and complexity of new Australian art. RT

–

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 3

© RealTime; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

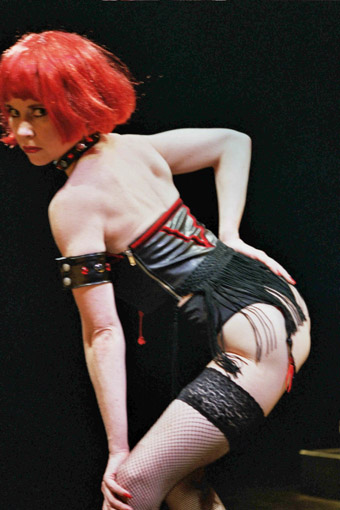

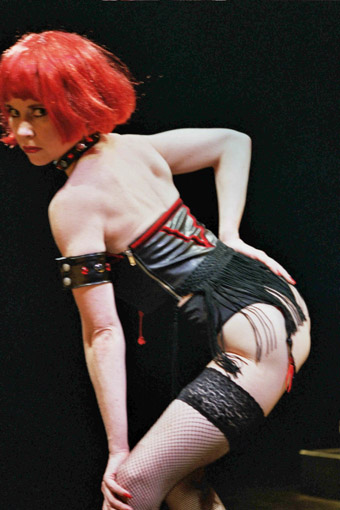

Wendy McPhee, Private Dancer

Q: How do you subvert a strip show?

A: Start nude.

Performed on a traverse stage, with a lucky wheel at one end and a changing room at the other, Wendy McPhee’s Private Dancer exists somewhere between an RSL and a sex club. Through a series of episodes and costume changes that highlight the ways we dress flesh, Private Dancer explores the commerce and social construction of female sexuality.

One of the first acts McPhee performs is a faux-lucky number spin-the-wheel sequence designed to split the audience according to gender. By the end McPhee is situated in the middle of a literal divide between the women and the men. From where I sat Private Dancer became a performance about women looking at men looking at the dancer. Men of all types, the beaming man, the gum-chewing guy, the old bloke who had to retrieve his glasses in order to read the instructions McPhee gave him and the young guy who, after slow dancing with McPhee, gave his female partner an apologetic shrug from across the room. Not that McPhee neglected her female audience: in one of the few moments of vulnerability performed to a cyclical voiceover she engaged them literally as her hand trailed across the front row of women.

The performance created a tangible complicity among the audience—both women and men wisecracked across the divide. In one sequence McPhee remained off-stage while each audience watched separate TV monitors. While our side laughed loudly at bad jokes like: “How do you know when your wife’s dead? The sex is the same but the dishes pile up”, the men stayed surprisingly silent. When one of the women snuck over to the men’s side and reported back that they were watching porn, the incongruous silence resonated.

Private Dancer is particularly successful as a demonstration of how the female body is packaged. With the nude sequences performed under full houselights, McPhee’s deathly pale flesh became a costume of its own. In a performance that employs masks of all kinds her commedia dell’arte-like dildo seemed highly appropriate. McPhee’s work may not be particularly radical (compared to someone like Annie Sprinkle it seems relatively tame), but there are moments where her particular blend of cabaret, dance, burlesque and striptease generates a unique experience for the audience.

Private Dancer (episode 2), softcore inc. in association with the Judith Wright Centre of Contemporary Arts & QUT Creative Industries, creator & performer Wendy McPhee, director Mary Sitarenos, designer Ina Shanahan, sound Myles Mumford, Judith Wright Centre of Contemporary Arts, Brisbane, September 10-11

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 47

© Leah Mercer; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

For the past few years, para//elo has been engaged in a series of collaborative projects with European artists on the theme of distance. These have included workshops, email conversations, a website, and sound and video compositions, culminating in the “live art experience”, In the Time of Distance. The Victorian-era Queen’s Theatre in Adelaide, little more than a heritage-listed shell of its former self, was transformed by James Coulter’s installation into an intimate and immersive space. Video projections covered most of one wall, soundscapes (by Scanner and Jason Sweeney) emanated from the opposite side of the venue, while a bar, computer monitors and television screens (peeking out from 1950s petrol pumps) completed the eclectic setting for this multi-faceted work.

The audience, seated on couches and chairs, were scattered around the centre of the venue. Performers moved freely through the audience, stopping occasionally to quietly impart fragments of the text (“days like this the simplest things fail to make sense”). Lines were delivered into microphones at the front of the space, with the audience hearing them from speakers at the rear. Hypnotically looped images, sounds, text and movement shifted slightly through every iteration, states of being changed gradually so that it was impossible to distinguish where one ended and another began. These techniques evoked the feeling of being inside someone’s head, their thoughts and memories washing over you, varying from lyrical evocations of a remembered Eden to chanted propaganda: “Be wary! Distrustful! On guard!”

One central theme of the performance was the nature of the migrant experience—alienation from the original culture, and from the new. Much of the subject matter depicted emotional responses to the changes brought by distance, especially those journeys that were forced or undertaken with mixed feelings. When emotions this fundamental to our nature are explored, some truths that result are necessarily banal, but no less true for our having heard them before.

In the Time of Distance was a lament, an evocation of the injustices of the past and present without offering more than a glimmer of hope in the future. Remembered stories of rape, torture, forced dispossession and imprisonment unsettled the audience and darkened the mood. This was a confronting and thought-provoking work distinguished by strong performances from Elena Carapetis, Irena Dangov, Astrid Pill and Jason Sweeney.

para//elo, In the Time of Distance, co-directors Teresa Crea, Laurent Dupont, installation James Coulter, soundscapes Scanner, Jason Sweeney), live image manipulation Lynne Sanderson, photography Peter Heydrich, Queen’s Theatre, Adelaide, Sept 4-13 http://www.parallelo-distance.net

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 47

© Ali Graham; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Being nothing and everything Told via her clown-dag persona, Donna Carstens’ Thirty Years In a Suitcase is a litany of the trials of growing up as a girl who looks like a boy in the straight world of Brisbane suburbia circa 1980s. This one-woman show is about “not being black, not being white, not being gay, being forgotten, being remembered, not being funny, being nothing and becoming everything you ever wanted to be.” It is ultimately a feel-good story and Carstens knows how to charm an audience and keep them on her side.

In 2000 Carstens received a Lord Mayor’s Fellowship Grant from the Brisbane City Council and made her first international trip to study with several international artists (at the Del’Arte International School of Physical Theatre in San Francisco and festivals in Geneva and Frankfurt). This travel provides the light frame upon which she places her autobiographical story told as a series of flashbacks. Combining family snapshots, shadow puppets, juggling, the strategic use of music (including an unforgettable performance of Desperado on ukulele), Thirty Years In a Suitcase unfolds through a series of narrated stories and Carsten’s interaction with several suitcases that take on different roles.

The show doesn’t shy from the bleaker side of her life including Carsten’s initial estrangement from her mother after coming out, the domestic violence that shaped her mother’s childhood and the revelation that her grandmother, who was jailed for murder, was one of the Stolen Generation. Helped by its hometown audience whose recognition of local places helps to win them over, Carstens’ style of storytelling is direct and heartfelt.

Thirty Years In A Suitcase, Donna Carstens with Metro Arts, co-director/sound Tamsin McGuin, puppeteer Lynne Kent, lighting Veronica Joyce, projection Amanda King, audio Guy Webster, Brisbane, Aug 27-Sep 6

The project was part of MetroArts' The Independents program supporting emerging and fringe artists.

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 pg. 47

© Leah Mercer; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

There are 2 things you can’t afford to miss in Robyn Archer’s 2003 Melbourne Festival—a small cluster of important overseas works and a huge range of great Australian dance. For RealTime readers, top of the list of must-sees will be provocative artists with long track records and the capacity still to unnerve, excite and to rethink form. They are Belgian performance-maker Jan Fabre with I am Blood, A Medieval Fairytale, and, from Japan, multimedia performance virtuosi Dumb Type in Memorandum. Both have been seen in Australia before—Adelaide audiences walked out in droves or dared not go near Fabre’s The Power of Theatrical Madness in the 1986 festival (allowing others of us repeated viewings of great art understood as barely controlled violence) and Dumb Type packed us in at Sydney’s MCA in 1992 with pH where we peered down into a deep pit to watch a machine churning out projections, relentlessy traversing the space regardless of its hapless human co-habitants.

One-time Pina Bausch dramaturg, the performer, writer and choreographer Raimund Hogue triggers 60s recall using popular and classical music in the 2 hour reverie, Another Dream. Those who have seen Hogue in Edinburgh, and queued to see him again, warn us not to miss this show. Another Edinburgh attraction has been solo performer (and Robert Lepage collaborator) Marie Brassard in her cross-gender realisation, Jimmy, which she is presenting in this festival. A third solo, performed in an installation by Vera Rhom, comes from Catalan dancer and choreographer, Cesc Gelabert, in his reconstruction of the late German choreographer, Gerhard Bohner’s acclaimed In the (Golden) Section 1.

From the Schauspielhaus Vienna (see RT#56 p8) comes Barrie Kosky’s The Lost Breath, performed in English, German, Hebrew and Yiddish. The work brings together 3 stories by Franz Kafka, the reflections of escapologist Harry Houdini and the Robert Schumann song cycle, Dichterliebe in a music hall fantasia with Kosky himself on piano. Many will want to see what new dimensions there are to his work now that he’s based in Europe—and hot on the heels of his huge success with Ligeti’s Le Grande Macabre for Berlin’s Komische Opera.

From France, as part of the Franco-Australian Contemporary Dance Exchange, which last year showed Chunky Move, Gravity Feed, Rosalind Crisp and Tess de Quincey to Parisian audiences (see RT#53, p4-7), there are 3 works. Centre Choreographique National de Franche-Comte a Belfort present Trois Boleros, choreographed by Odile Duboc. Yes, that’s Ravel’s Bolero danced 3 times, to 3 different orchestral interpretations. Using acrobatics, dance and film, the young performance company Kubilai Kahn Investigations evokes the agony of the refugee and the homeless in Tanin No Kao. From Burkina Faso in West Africa comes Salia Ni Seydou, fusing traditional and contemporary dance, song and percussion.

On the Australian front, there’s much to relish. Archer gives top billing to Acrobat, all too rarely seen in Australia these days, the Australian Dance Theatre’s prize-winning The Age of Unbeauty, Chunky Move’s new work, Tense Dave (“as the stage turns, [the characters] are caught in the spotlight of unexpected scrutiny, performing acts that usually pass unseen”), the Leigh Warren-State Opera of South Australia realisation of Philip Glass’ Akhenaten and Stalker Theatre Company’s Incognita.

The key festival dance figure though is Lucy Guerin. Involved in 3 works in the festival, she is directing and choreographing Plasticine Park, a collaboration with visual and new media artist Patricia Piccinini; choreographing Delia Silvan’s performance in Stravinsky’s The Firebird (Melbourne Symphony Orchestra); and co-choreographing the Chunky Move premiere. Plasticine Park will be presented in ACMI’s Screen Gallery with 8 soloists working in projected spaces created by Piccinini, Stephen Honegger, Laresa Kosloff and David Rosetzky. Let’s hope that this festival commission is a prelude to more new media performance at ACMI.

Other Melbourne-based dance and performance works in the program all deserve attention. At the Malthouse’s Beckett Theatre, there’s a strong triple bill from Gerard Van Dyck (Collapsible Man), Christopher Brown (the return of his charismatic mass media idiot savant, Mr Phase, RT#49 p11) and Cazerine Barry (in her the new media dance theatre work, Sprung recently premiered in Adelaide). Choreographer Christos Linou and visual artist Robert Mangion screen their CBD interventions at fortyfivedownstairs in part 4 of their Intertextual Bodies series. At the same venue, Yumi Umiumare and Tony Yap, whose duets have developed impressively in recent years, appear with their new, unpronounceable Butoh company, “_”, design by Michael Pearce, in in-compatibility. Phillip Adams’ Balletlab always intrigues. In Nativity, at Dancehouse, the company invokes the museum diorama as a site for exploring the human/animal dichotomy. In another work about transformation (“from animal to angel, from gremlin to diva”), also at Dancehouse, the wonderfully inventive and idiosyncratic Ros Warby presents SWIFT re-frame, with design by Margie Medlin. At North Melbourne Town Hall, Kate Denborough directs Kage Physical Theatre in the premiere of Nowhere Man. a timely journey into the loss of meaning —“the story of an ordinary man’s transformation, where nothing feels familiar.” At the Atheneum II, Danceworks are celebrating 20 years of work with Symptomatic, which reads like a good companion piece for Nowhere Man—“characters struggle to negotiate competing demands on mind and body, never quite getting it right.” Transformation and breakdown are tellingly recurrent themes in these and other festival works, with bad old Humanism continuing its struggle to reassemble itself and the neuropathology of everyday life paralleling the distress of political disorientation.

Archer’s 2003 festival is a celebration of dance and movement. While it cannot make up for the sorry lack of a recurrent national dance festival, and can but hint at the range of Australian dance, it nonetheless does a mighty job. The vision of dance is enlarged by the inclusion of curator Erin Brannigan’s Body on Screen program. On screens inside ACMI and outside in Federation Square, the program ranges from Maya Deren’s innovative short films and Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia to Singin’ in the Rain, to films about the body at its performative limits, the disappearing body, the body as narrator and, in Body of Work, leading international and Australian choreographers as filmmakers. The program also premieres Michelle Mahrer and Nicole Ma’s Dance of Ecstasy, complementing the visit to Australia, and this festival, of the Whirling Dervishes. And there’s more, a series of forums providing dance artists and afficionados from across Australia the opportunity to meet for serious dance discussion.

There’s a 90 minute symposium on drama and dance in Asia (featuring members of Dumb Type and Cloudgate’s Lin Hwai-min), a 3 day forum on skills and choreographic training and the future of dance in Australia, and a day long “research forum on contemporary dance and choreographic cognition.” The Australian Indigenous Choreographers Project will bring together Australian and Asian artists. As well there are workshops with Kubilai Khan Investigations, Odile Duboc, Salia Ni Seydou, Cesc Gelabert, Chunky Move and Raimund Hogue. Not performing in the festival (a real pity), but running workshops are Sydney artists Tess de Quincey, Gravity Feed and Rosalind Crisp. Add to this a number of key dance presenters from around the world invited by the Audience & Market Development Division of the Australia Council and you have what adds up to a potentially significant moment for Australian dance.