Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

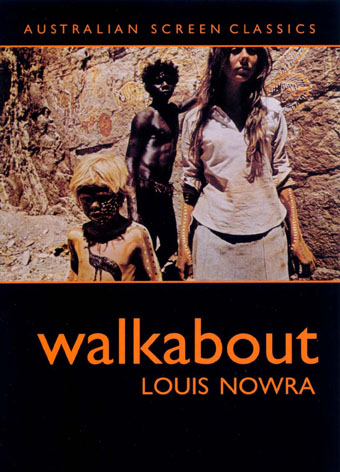

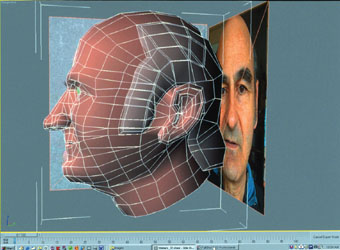

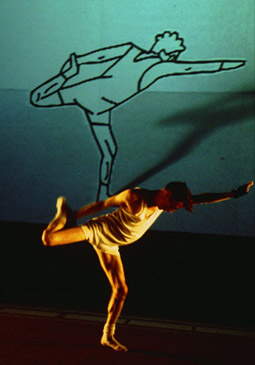

Urban Theatre Projects, India@oz.sangam

photo Heidrun Löhr

Urban Theatre Projects, India@oz.sangam

Carnivale appears to grow stronger year by year, presenting more coherent and adventurous programs and opening up local talent to the wider audience it deserves. Guillermo Gómez-Peña’s The Living Museum of Fetish/ized Identities, Sidetrack’s The Book Keeper, Urban Theatre Project’s India@oz.sangam, Karen Therese’s Sleeplessness, Sivan Gabrielovich’s The Cool Room and the installation, Sound of Missing Objects at Performance Space were just a handful of the many Carnivale shows that made for an engrossing experience. The Book Keeper has already been reviewed by RealTime; Gail Priest’s response to the Living Museum.

India@oz.sangam

Urban Theatre Projects is adept at adroitly managing large scale performance events. India@oz.sangam is another fine example of the company’s ability to focus on a community, draw out its talents and concerns and present them in an open-ended framework that can attract large audiences from that community and beyond. Most distinctively, this production had a tremendous sense of pride, fun and celebration, embodied as it was in the spectacle and melodrama of Bollywood, that miracle of the hybrid arts, and focused on being young and Indian-Australian. Dancing and singing were to be expected at every turn. In the foyer we watch children in a story-telling circle and, on a large video monitor, their peers in India learning yoga. We are then invited to join a parade led by a turbaned man held aloft to the adjoining riverside. Sari-clad girls dance on a long stairway (nicely reflected in the river) and Indian hip hop beats sail across the water. On the riverbank below us a cricket game materialises alongside a Hills Hoist hung with sheets picking up movie projections. Broken into groups we return to the foyer, passing a couple of eager rappers on the way, to witness women in delicate, sensuous song and dance amidst candles and bells. Our guide explains we are celebrating Diwali, the festival of light. We file into a darkened room where guides introduce us to Indian film classics, spices, flower patterning, a Diwali altar and invite us to relax on a couch as projected images of a hand painting ceremony gather on its veiled walls.

From this intimacy we emerge into a crowded theatre where cast members are cajoling the audience into an Indian singalong. A couple in their 50s constantly surprise their fellow Indian-Australians with a repertoire of rarities which everyone seems to half know. A few rows back, 4 boys break into glorious cross-cultural doo-wop. Once everyone has gathered, the performers spring into a quickfire string of comic skits and little dramas—parents struggling to understand sons who only speak hip hop; a “This is Your Wife” parody, “putting the ‘arranged’ back into the arranged marriage”; a father with 2 PhDs unrecognised in Australia; the trials of taking money ‘home’ to India; a grim monologue about sexual abuse in a conservative society; a young wife denied English classes. The younger women gather in a song of defiance, one of their number on sax, the bodies say pop, the gesturing hands say traditional Indian dance. Two boys perform a great piece about being labelled black (“all my life I’ve been running from one image to the next…I need to get rid of the mask, the colour.”) The irony of their plight is powerfully stated in their admiration for black American heroes—Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X…Performed on a sitcom loungeroom set these scenes are informally presented, the writing is rough, the acting is variable, endings sometimes indeterminate, but the commitment and the drive is there.

We’re led into a cabaret-formatted courtyard with video monitors, a pair of traditional dancers onstage. A sleek car invades the yard, the bonnet draped with girls in their modern best, ready to displace the past, but the final gathering onstage of the participants offers all possibilities: this from one of the most remarkably adaptive of human cultures. Although sometimes more conventionally theatrical than its Urban Theatre Project predecessors, India@oz.sangam doubtless reflects the passions and artform interests of its participants. But the overarching structure (of installation, exhibit, performance and spectacle) maintains the hybridity for which the company is famed and which offers communities the most flexible way to present and explore their cultures.

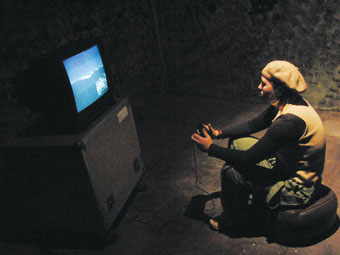

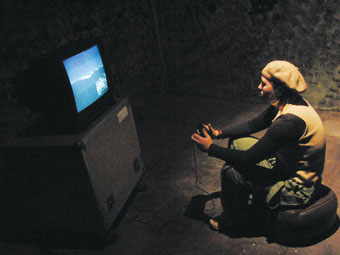

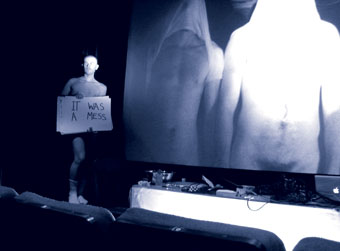

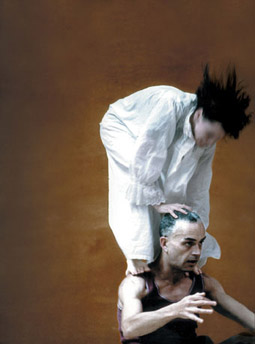

Karen Therese, Sleeplessness

photo Angie Abdilla

Karen Therese, Sleeplessness

Sleeplessness

Karen Therese’s solo performance is one the most adventurous of recent times and certainly one of the best of 2003. It’s a risky venture, an up-close investigation into a state of ‘not knowing’, a sleeplessness, a family mystery in which Therese plays both herself and, at several critical moments, her Hungarian grandmother who long ago disappeared and whose death certificate described her as male. This is a medical and psychiatric mystery and a tragedy about the pressures of war and migration. Therese and her sister solve the mystery but the great weight of personal plight lingers unbearably, as does the dark legacy of heredity.

Therese’s performance style is forthright, unavoidable and the enactment of the grandmother’s seizures, an assault, shock treatment and her own childhood anxieties are such that not everyone in the audience feels comfortable—sometimes these lives and personalities are too big for this small space. But what a space. Projections flicker across the walls, ranging from little iconic images to wall-to-wall phantasms. It is a space of transformations and the back and forth of history. Filmmaker Margie Medlin travelled to Hungary with Therese to create the wonderful black and white images of the performer in the guise of her couturier grandmother. Other images have a haunting old world colour that is at once nostalgic and appalling because of the pain of loss they signal. This is a space that Therese inhabits, frantically scrawling the accumulating data of the investigation across walls pinned with letters and documents and certificates, old clothes, dress patterns and strange fragments of latex, like the skin of stretch marks and ageing and torture. This is set design as installation: the curious audience inhabits it at the end of the show.

Karen Therese’s script is plain and simply delivered, but it is rich in detail and place; the evocation of Sydney from a migrant perspective is grim, the sense of moment always potent, of growing paranoia and suicidal impulses. The performance is brave and the sizeable team of collaborators have made a wonderful dramaturgical and design context for it. Sleeplessness should be widely seen.

The Cool Room

The Cool Room is sensitive, sometimes explosive territory that director Deborah Leiser has visited previously in A Room With No Air (1998), with Leiser as a fleeing Jew harbored begrudgingly by a German (Regina Heilmann). A Room With No Air, was a powerful performance work in which the physical and visual components counted more than the spare verbal utterances. The Cool Room is primarily a play of words, beginning sparely and growing in density and moral perplexity as 2 chefs (Israeli and Lebanese migrants) locked in a restaurant’s refrigerated cool room feel the full weight of the deadly chill of their relationship. However Melbourne-based Israeli playwright Sivan Gabrielovich establishes the play in jump-cut fragments, pulling back from literalising the situation or its transitions, making us read them and make the connections. Leiser finds in the spaces in between a physical language for the performers that choreographs the moral twists in an increasingly claustrophobic space where arguments turn on themselves and ironies become overwhelming.

The production is striking from the outset—the chefs carry in 3 performers like sides of beef and hang them on hooks: they are the ‘meat.’ They become a chorus, no mere ‘meat in the sandwich’, there is little innocence in this world. I would have liked their role more tightly defined. Too often they slip into a generalist chorus mode, or become a handy satirical device. At the play’s end they get the last word, carrying a moral weight they have not earned, the content of which threatens to trivialise all that had gone before (in effect: ‘don’t cry for us, we love our war’).

Through its bloody anecdotes, appallingly cruel jokes, sexual paranoia, reflex racism, shared recipes (same foods, different names) and its acute sense of migrant displacement The Cool Room offers a disturbing account of cultural tensions carried over to another homeland, Australia. However, this local situation is barely coloured in at all, it is always a metaphor for a conflict initiated between Lebanon and Israel in 1982, lasting 18 years and still alive in the bodies of these men, these cultures even if they don’t want it. As a young Israeli writer, Gabrielovich is not easy on her own people, but nor does she see a way out. The end of the play is like hitting a brick wall—the Middle Eastern conflict as neurosis turned psychosis. Incurable. Of course, I might have missed significant nuances as the play argued its way to a conclusion; it’s a head-spinning debate. The Cool Room is one of many plays appearing now that urgently address social, political and ethical issues with a bracing immediacy. At its best it does so with passion, if not always with finesse, and with a not undeserved bluntness given Australia’s own moral obtuseness—who are we to judge?. Matthew Crosby is good as the extrovert chef, an ex-Israel soldier alert to his country’s wrongs, while Majid Shokor conveys a quiet intensity and woundedness that is palpable.

Sound of Missing Objects

Paul Virilio proposed a museum of accidents based on the premise that every new technology comes with an accident in tow (a ship, a shipwreck; a light, a blackout etc). Sound of Missing Objects is an installation created by Panos Couros (sound artist), Jonathan Jones (installation artist) and Illaria Vanni (writer, academic, curator), a spooky visual and aural evocation of a museum of cultural erasure. There are 5 elegant Victorian glass-topped museum cabinets (with plates like ‘The Great Exhibition, London 1851’), and there’s writing on the wall. In the cabinets there is crumpled, cryptically patterned tissue paper, the kind for wrapping precious objects, but empty. Finely etched into the glass are the names of cultural artefacts and their taxonomies reflected in the mirrored bases of the cabinets. The words are those of the European collectors: “Bamboo shaft”, “Womerahs”, “Nulla Nulla Sharp-pointed”, “Three Plaster casts of Aboriginal feet and fingers” etc. The words are like ghosts—you’re always looking through them. Some are crossed out. The patterns on the paper are also traces, delicate designs based, for example, on “‘two drawings by Mickey, native of the Ulladulla tribe’…1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition, Chicago.” The writing on the walls is just as fragile, it’s in pencil. On one side of long diagonal lines it’s in an Aboriginal language; on the other it’s in English, an often derogatory account of Indigenous people, forecasting their inevitable extinction, but noting occasional virtues, like skill at drawing. The sound score is also ghostly; it’s difficult to find its point of emanation (until you realise it’s the cabinets themselves) as it distantly catalogues a world of objects and people lost to invasion, scattered to the world’s museums and extinction. Sound of Missing Objects is a melancholy work. Beyond anger, its sense of loss is deeply felt, realised as measured, beautiful, putting desecration to rest in a reconstitution and emptying of the 19th century museum.

–

India@oz.sangam, Urban Theatre Projects, co-directors Cicily Ponnor, Alicia Talbot; visual design artist Vananda Ram; multimedia Sam James; musical director Phil Downing; choreographer Chum Ehelepola; sound artists Masala Mix; DJ earthbrownkid; Parramatta Riverside Theatres, Oct 2-12

Sleeplessness, performer, maker, installation Karen Therese; visual media design, installation Sean Bacon; sound design, composer Anna Liebzeit; dramaturg Nikki Heywood; facilitating director Toula Filokostas; film artist Margie Medlin; latex screens Jane Shadbolt; Performance Space, Oct 1-12

The Cool Room, writer Sivan Gabrielovich, director Deborah Leiser, designer Niklas Pajanti, performers Matthew Crosby, Majid Shockor, Alex Ben-Mayor, Karen Therese, Konstantinos Tsetsonis; Performing Lines; Downstairs Theatre, Belvoir St Theatre, Sydney, Oct 16-Nov 2

Sound of Missing Objects, installation by Panos Couros, Jonathan Jones, Illaria Vanni; Performance Space, Oct 3-Nov1,

Carnivale, Sydney, Sept 24-Oct 19

RealTime issue #58 Dec-Jan 2003 pg. 10

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Halcyon

Among new music events in recent months the one that lit me up was Raising Sparks from sopranos Alison Morgan and Jenny Duck-Chong who, as Halcyon, gather skilled musicians around them to present rare contemporary compositions and commissions. The standout in this truly daunting program was Harrison Birtwistle’s 9 Settings of Celan (1996) from his Pulse Shadows series. One of the enduring great late modernists, there is a monumentality about this British composer’s work, a sense of vast movements of nature and thought even when writing for small forces, here sublimely integrated soprano, 2 clarinets, cello, double bass and the requisite pulsing viola (Nicole Forsyth). Sensibly, Halycon reproduced translations of the Celan text in the program allowing for reflection on the poet’s brooding imagery. Morgan, in great voice, enunciated with clarity and in the challenging Todtnauberg, displayed eerie ease in the rapid alternations between the octaves of text spoken and sung.

In an hermetic reverie on the divinity scattered throughout creation, the Scots composer James Macmillan’s polystylistic Raising Sparks (to a poem by Michael Symmons Roberts) blends and juxtaposes chant, folk tune, flares and bursts of hurried sound, operatic passion and passages of simple tonal beauty. It’s music that is accessible but that also manages to formally challenge. Equally, Macmillan allows his Catholic faith to open up to Jewish mysticism, musically realised in the opening and recurrent chanting of ‘zimzum.’ (“In the Hasidic tradition the moment of creation can be understood as a divine act of self limitation [zimzum], where God held back his own power and light to make space to create something other than himself”; program note.)

By comparison, Australian composer Jane Stanley’s Aunts (2003) to a poem by David Malouf seemed modest fare, rather too literal at times in its enactment of the text, but nonetheless a fine vehicle for the entwining voices of soprano Morgan and mezzo Duck-Chong who seem to become the aunts while at the same time observing them at a distance both ironic and sympathetic. Also on the program, Paul Stanhope’s Shadow Dancing (2001) has a Ravelian summery ease, clarinet jazziness and, in the second movement, an (almost excessive) eastern edge on the viola, all held together by an engaging and finally mellow dancerly propulsion.

Raising Sparks was a big concert yielding striking resonances and contrasting visions between the Macmillan and the Birtwistle, from the low chant of ‘zimzum’ in the one as the light of creation shatters across the universe and, in the other, the final, hugely sustained last note on the word “light” following on from Beckettian angst glowing with hope, dimly (the same passage bluntly utters: “Art pap”). This was an exemplary concert—musically brave, thoughtful and meditative.

ensemble offspring

Back from Poland and beyond, ensemble offspring continued its adventurous programming with a collection of idiosyncratic compositions in a multimedia context. Ever a risky business, the engagement of music in concert with new media is littered with failures, while dance, for example, seems to me to be making a pretty good go of it. In Lucy Guerin’s Melt or the best work of Company in Space, there’s a meticulously crafted and balanced relationship between projected images, sound score and the live body. There were moments in Testimony, the Sandy Evans/Nigel Jamieson/Paul Grabowksy tribute to Charlie Parker, where all media coexisted in a thrilling dynamic. In this concert however the projected imagery didn’t always enjoy such a relationship, the conjunction between media simply being too loose, one or other element in danger of becoming mere background, and sometimes it was best to just shut the eyes. That said, it was still a pretty interesting concert which ever way you didn’t look at it.

Justine Cooper’s videos, Moist and Excitation, have been exhibited internationally, making beautiful a red and blue microscopy flow of “blood, phlegm, pus, cervical mucus and tears…transformed into images of interstellar geographies” (program note). Silence would do justice to these images, but Barton Staggs’ composition guarantees the reverie starting with bowed vibes and mellow piano rhythmically attuned to the ebb and flow of the bulging liquid image in Moist. The ensuing Excitation video tryptich suggests an eternity of living and the music is an empathetic mix of movement and stasis as if the instruments are resonating with the images, calling back to them, a bizarre music of the spheres, of micro and macrocosms. The associations seem casual, but they work.

Unfortunately, White Call, the James McGrath interpretative images meant to be teamed with Morton Feldman’s Instruments 1 had been impounded, we were told, by terror-nervous customs officers. Feldman had to stand on his own which, of course, he did admirably. Rarely heard in Sydney (Adelaide’s the place) there is much in Feldman to love and linger with and little to fear: an unpredictable linearity, theatrical moments, beautiful textures shades of ritual and evocations of the delicious rattle of the gangaku orchestra.

The concert’s main work, The Cattle Raid of Cooley or The Show, Imaginary Operas in Three Acts didn’t cut the new media mustard. This over-narrated lumbering juxtaposition of a tale of yore and trendy Manhattan arts scene fused with the disparate work of a trio of visual artists is in desperate need of editing on every front, as well as some serious aesthetic reassessment. Matthew Shlomowitz’s score needs more aural attention than most with its relentless modernist angularity let alone having to stand up against scrolling text inexpertly voiced and images that are either too far removed from the content of the tales or too obviously illustrative to be effective partners to the music. Occasionally there are visually inventive moments, for example when scattered sentences fall into a heap of words across the bottom of the screen. Musically it’s a seriously demanding work served well by the ensemble, especially in Adam Yee’s virtuosic performance on oboe, in fact this is the strongest visual element in this opera without song.

Ensemble 24

The highlight of this double bill was Australian composer George Lentz’s Caeli Enarrant… IV. Informed by the composer’s mysticism (it would have fitted Halcyon’s Raising Sparks program more than comfortably), the adoption of instrumental techniques that evoke the music of Tibetan Buddhism and the careful deployment of silences, Caeli Enarrant… is an engrossing work and not an easy one to describe in its many shifts of pace, tone and pitch. As Gordon Kerry writes in his excellent sleeve note on the CD of Caeli Enarrant… III & IV (Ensemble 24, Naxos, 8.557019), Lentz’s “harmony ranges between strident density and radiant consonance.” Passages of hard-edged modernism co-exist with a postmodern penchant for a sublime melody; a loud, starry burst of cymbals (pre-recorded) sits beside a silence that can surprise with its fullness, and the cosmos is evoked in all its strangeness. Presented essentially as a string quartet interpolated with pre-recorded passages (presumably to bring bigger forces into play, but making for an awkward fit) and very occasional live percussion, this was a truly memorable performance.

The audiophonic work, Derelict Woman (writer Susan Rogers, director Richard Buckham, composer Barton Staggs) was a less satisfactory experience regardless of its meticulous realisation and aural production values. Staggs’ contribution, realised live and on tape, musically and as soundscape, was assured and enveloping. Occasionally it revealed a distinctive compositional voice, most evident in the mellifluous piano part (Tamara Anna Cislowska) reminscent of his writing for Moist and Excitation in the ensemble offspring program (see above).

As for a relationship between Rogers’ text (intoned by Kerry Walker) and Staggs’ score there seemed little to it except in the very broadest sense as one would expect, say, of much movie music. Of course there were moments without words when spaces were opened up and there was a glimpse of a potential dialectic that could have driven what seemed to settle into stasis. The central problem was the text, a whimsical, sentimental evocation of a bag lady who narrates an account of her life, a world of velvets and perfumes and feathers and poetry, and encounters with other eccentrics. For the most part it’s numbingly ethereal, largely devoid of the specificity of personality and place that might have earthed it. Well into this epic of recollection when the woman finds 2 plastic bags, one full of body parts, the other of money, things liven up a little. The woman develops an affection for an ear and a penis and hangs onto them, and some of the money, when she turns over her find to the police. There’s suddenly an edge and wit to the writing (and some eerie plot possibilities) but it’s in such disjunction with the rest of Rogers’ reverie that by then it doesn’t really matter.

Halycon, Raising Sparks, conductor Matthew Wood, Verbruggen Hall, Sydney Conservatorium, Nov 7

ensemble offspring, The Imaginary Opera Project, Music Workshop, Sydney Conservatorium, Nov 2

Ensemble 24, New Music Network & The Studio, A Derelict Woman, The Studio, Sydney Opera House, Nov 16

RealTime issue #58 Dec-Jan 2003 pg. 44

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

There are 2 fundamental directions in sound: an increase in sonic or musical density through rising volume or an increase in layering of materials; or a decrease in density through the minimisation of volume or a greater spaciousness between materials. As I revisit those Punk era recordings that introduced me to experimental music, such as Suicide, The Velvet Underground, The Birthday Party, The Fall and Cabaret Voltaire, I find I have little patience for those who build on John Cage’s 4’33” by exploring ever more dispersed or quiet musics. For me the harsher, fuller soundscapes command attention more effectively than low level acoustics. At the 2 performances of the Melbourne leg of i.audio, it was the former which, to paraphrase Iggy Pop, brought raw power runnin’ to me.

The first night featured several artists whose approach epitomised, in different ways, the drive towards low sonic densities. Natasha Anderson (contrabass recorder) and Jim Denley (various flutes and parts thereof), both Make It Up Club regulars, represent a trend in the crossover between free jazz and new music improvisation. Their performance was all incomplete noises and ‘improperly’ produced woodwind and brass sounds, off-centre gasps across the mouthpiece, or un-tongued, barely sustained whispers through hollow tubes. This was a world of isolated fragments, of numerous gestures that led to surprises or sudden drop-outs of enunciation. While this approach has its adherents, it constitutes a musical cul-de-sac. Once you’re familiar with Denley’s extraordinary sonic range, there is little more to appreciate, while Anderson’s material holds marginally more interest largely because of her relatively exotic instruments.

Regular collaborators Oren Ambarchi and Philip Samartzis—here joined by Joel Stern—exhibited a considerably less gestural quality due to their instrumentation (processed guitar; prepared CDs and electronics; and laptop and electronics, respectively). There was nevertheless a similar sense of dancing about the edges of silences and spaciousness due to the extreme subtlety of Samartzis’ dispersed sinewave intrusions and crackles, or Ambarchi’s elusive, gritty materials. Once again, the lack of consistent, overt energy or something more arresting to hang on to left me indifferent. The unintended earth hum that persisted throughout all of the first evening’s performances was extremely irritating given the quiet nature of this piece.

The hum presented an insurmountable problem for Taku Sugimoto, the first night’s closing act. The Japanese artist’s long piece—frankly shocking in its radical minimalism—consisted simply of his crouching beside his guitar and amplifier, essentially willing a gentle, cottony, fluttering hum from these devices. With another hum already in the system though, identifying Sugimoto’s barely audible evocations required an act of monumentally close listening. I found myself wishing Sugimoto might spontaneously transform into extreme noise artists Merzbow or Voicecrack. If you are going to summon the beasts that dwell within electronic equipment, I’d rather raging demons than hollow angels.

Unlike the first night, the second was characterised by works of considerable sonic density and the earth buzz was absent. The first 2 performances by Will Guthrie and Arek Gulbenkoglu, then Scott Horscroft with his mini guitar orchestra, were both readily coherent because of their foundational use of layered, sustained notes and chords. Guthrie built his own base by lightly flicking a large, amplified gong with a carefully positioned hand fan, while Horscroft forged an even denser weft of chords by mixing and manipulating 4 continuously agitated, amplified guitars.

Guthrie sat at a desk of percussion items and electronic processors, while the similarly electronically endowed Gulbenkoglu tweaked and mashed materials over the pick-up of his prone guitar. Their improvisations had a visibly gestural quality, yet it was the bedrock of Guthrie’s gong and the equally evocative, underlying sound of fan-blades through the guitar’s bridge that made this performance more than a collection of intriguing discontinuities. The sustained, continuous materials established a context for Guthrie’s measured twangs and scrapes of pliable metal rods, or the shaking of a large spring, whose sound was reshaped through the amplifying medium of the small drum on which it sat. Gulbenkoglu meanwhile pressed metal brushes and steel wool over the guitar’s lightly harmonising strings and through its popping, crackling pick-up. When the sustained sounds dropped out, these smaller, secondary gestures were suddenly foregrounded, taking on a dramatic intensity.

Horscroft’s performance was simultaneously both more and less complex. Where Guthrie and Gulbenkoglu used a heavy, bassy substratum to provide a contrast to discrete musical flourishes of a different sonic character, Horscroft produced a thicker layering of essentially like materials, deepening and increasing their musico-dramatic charge through the accumulation of first guitar hums and taps, then single notes and chords, and finally inserting within these a simple, 3-note sequence. Although Horscroft’s extended gathering and cycling of polyrhythms recalled Steve Reich, the sound was closer to Terry Riley’s messier, more ecstatic minimalism, married with such classics of sheets of guitar and feedback as Television’s Marquee Moon (Elektra, NY: 1977).

Although jazz-noise artists David Brown (abused guitar) and Sean Baxter (drums and junk) had much in common with fellow improvisers Anderson and Denley, the proximity of Brown and Baxter to rock and its in-your-face manifestations gave their performance a greater depth and volume. The 2 shifted between tiny crinkles and passages that literally slid from one to the other as Baxter let his scratching, bowing stick travel in a single arc from one bent cymbal to another before the artists counterpointed each other with more aggressive, chaotic explosions. Brown and Baxter presented a typically solid work at i.audio, adopting a late Modernist, jangly quality through the addition of Anthony Pateras’ impressive prepared piano crashes, waves and fine miniaturas.

Japanese vocalist Ami Yoshida concluded the evening with an enthralling curio; a horrified, acoustic counterpart to the electronically produced “Little Voice” of Laurie Anderson. Yoshida both externally and internally squeezed her vocal chords and larynx, amplifying these sounds within her head alone, rather than in her chest. This created a highly restricted, squeaking, piercing, choked note; a kind of aural scraping of the open-mouthed, sound “e.” Yoshida’s performance constituted a distillation of the erotic scream of horror film, an absolute reduction and purification of the acoustics of terror and sex to its merest hints, yet no less sonicly powerful for this. The physical challenges involved in forcefully producing such a cry did mean however that Yoshida’s vocalisations functioned more as a demonstration than performance.

The highlight of both evenings was Robin Fox, who overcame the poor PA set-up of the first night to offer a forcefully ripping, laptop performance. Fox’s piece had a commanding rise and fall of squelched electro noises, cut with brittle, musique-concrete—like masses, all characterised by a sense of sonic cut-off and a leaping between materials which evoked a particularly aggressive, electronic version of hip-hop turntablism. Laurie Anderson once joked that her jangling, amplified violin work reflected the beat of a dance that we all unconsciously know: one that’s produced when you stick your finger into a power point. Fox’s compelling beats similarly summoned tunes that were too chaotic to consciously decipher, but which subliminally extended deep within the body and the psyche. Only sonic dynamism of this power can approach the “raw power” that Iggy Pop and the Stooges tore from their Marshall stacks.

i.audio, curator caleb k., Performance Space, Sydney, Sept 12-20; Footscray Community Arts Centre, Melbourne, Sept 17-18

RealTime issue #58 Dec-Jan 2003 pg. 45

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

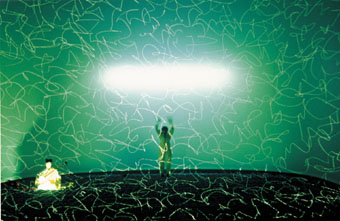

Ed Osborn & Elision, Particle Moves 2003

photo courtesy Institute of Modern Art

In installations by Ed Osborn (Germany) and Nigel Helyer (Australia) in Brisbane and Sydney respectively, I spend most of the time staring at the floor. And listening. Especially listening. In both works suspect objects litter gallery floors. In Osborn’s Particle Moves, clusters of tiny metal disks, appearing to hover just over the sheen of the concrete floor, suddenly buzz and rattle to life and move short distances like wary robotic insects. In Helyer’s Seed, the objects are overtly worrisome, they’re landmines neatly positioned on the centre of a series of eastern prayer mats. But they’re also transmitters and as you approach them you pick up the sounds they emit in the earphones (which you collected when you left your shoes outside) via the handset you carry, replicated to look like a mine detector. Elsewhere on the floorspace of Particle Moves sound drivers vibrate wok-shaped bowls and long wavering rods; on the walls elegant elliptical black metal cut-outs a la Matisse are just as driven, quietly humming or crackling or thundering between protracted silences. As you come within range of each of the “mines” in Seed you detect not a warning, but the 99 names of Allah, looped Arabic music and extracts read from the Koran.

Nigel Helyer, Seed

At one level Seed is curiously meditative; you journey from one mine to another, from one passage of the Koran to the next, you learn, you take in the details of the mats, the insistent rhythms of the music. On another level it is alarming, associations turn between agriculture and war, between the seeds of life and the seeds of death. Helyer writes: “…the death toll inflicted by landmines (principally in the developing world) is equivalent to the appalling destruction of the World Trade Centre—repeated 5 times each year.” Other resonances accumulate in Helyer’s “sonic minefield” to do with our incomprehension of the Islamic faith and culture and what the West will reap from this ignorance.

Osborn’s work is urbane and abstract, but its irregular beauty is made from the fundaments of sound—the movement of particles. It too has much to do with resonance, the loud speaker/sound driver as an instrument engaging with other, musical instruments, the outcomes accumulating in a computer. So although there’s not much room here for metaphor (beyond the distant connotations offered by wok and rod), there is the sense of something unnameable, larger than the gathering of objects in a gallery space, because the objects are linked by sound, because they are growing something sonic and uttering it, it seems, whenever they like. The seeds for this creation were partly sown by members of the Elision ensemble in improvised live performance with Osborn recording them, feeding their sounds into the installation where they became something else. A week later I had the space to myself, but not really. The room rattled and sighed and sang and wailed and went silent and I waited and it sang again.

Seed and Particle Movement confirm in their very different ways the power of expertly realised sound installations to fascinate and disturb, to take you deep into and through sound into rewritten, re-sounded worlds.

Particle Moves, Ed Osborn, IMA, Fortitude Valley, Brisbane, July 31-Aug 30; Nigel Helyer, Gone to Earth: Seed and Haiku, Boutwell Draper Gallery, Redfern, Sydney, Sept 10-Oct 4

RealTime issue #58 Dec-Jan 2003 pg. 46

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lyndon Terracini’s second Queensland Biennial Festival of Music in July this year was another notable success bringing remarkable music to Queensland and from Queensland itself. Terracini also extended the festival’s regional reach, using the model of uniting local and visiting artists and communities, often through long term workshops and commissions that then belong to those communities. Over a mere 2 festivals the legacy of these collaborations is already in evidence in places like Barcaldine with its massive marimba ensemble and Rockhampton with its 2001 and 2003 symphonies by Elena Katz Chernin with words from local poet Mark Svendsen.

RealTime focused on the Brisbane portion of the program producing over 30 reviews that you can read on our website. (The site also includes interviews with artists working in regional centres—Svendsen, Graeme Leak and Jacinta Foale.) The Brisbane performances ranged from the sublimely epic, Heiner Goebbel’s vast orchestral and vocal work, Surrogate Cities, to the intimate, crystalline Rautavaara choral works performed in a small church, and immersive sound compositions in a tiny theatrette in the Judith Wright Centre.

Twilight concerts in the Spiegeltent attracted crowds with a free taste of some of Australia’s leading musical talents eager to sell their wares to visiting producers and presenters. David Chesworth Ensemble, Clocked Out Duo, Topology and Andrée Greenwell (with Deborah Conway and musicians with excerpts from Dreaming Transportation) delivered engaging sets with vigour and commitment. Patricia Pollett on viola gave one of the best, with an impressive range of Australian compositions, demanding serious listening from her attentive audience and. Trumpeter Scott Tinkler was equally intense, leading a marvellous set with his group, DRUB; the dueting and texturing from guitarist Carl Drewhurst was beautifully distinctive. A substantial excerpt from Chamber Made Opera’s Recital worked well in the intimate space with Helen Noonan in fine voice and executing tautly controlled choreography. The tent also housed daily forums and nightly cabaret performances, late night togetherness and exactly the right kind of hub for an intimate festival.

The Brisbane Powerhouse was home to the International Critics’ Symposium and several performances: a bracing array of creations realised by Elision and a generous and inspired staged concert from Meredith Monk and her ensemble. The highlight of Elision’s Burning House was seeing Lilla Watson’s artwork, Sight and Sound of a Storm in Sky Country (2003) side by side with and projected above Timothy O’Dwyer who delivered a sublimely controlled pointillist saxophone response to the work. Meredith Monk couldn’t bring the fully-staged version of Mercy past Singapore, so we got the concert version, but we weren’t short-changed—Monk and company magnificently gestured, tableaux-ed and danced to their idiosyncratic singing. In the Brisbane City Hall, The Big Percussion Concert packed them in twice over, once again a marvellous cross-cultural extravaganza, as subtle as it was athletic. The following are excerpts from a small selection of RealTime reviews of QBFM 2003.

RealTime was part of the official program of QBFM 03

RealTime issue #58 Dec-Jan 2003 pg. 42

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Goebbels’ Surrogate Cities recalls the great choral symphonies such as Beethoven’s 9th, and Shostakovitch’s 14th, which (with solo voices) muses on an existential death. These were landmark works, as is this. Here, spoken word, taped, sampled sounds, all kinds of unusual percussion instruments, including torn newspapers, bundles of sticks being rattled, a stainless steel mixing bowl—the sounds of civilisation—bring the symphony into the present. Goebbels has managed to avoid the pitfall of many composers who try to blend heterogeneous forms, by weaving his own original form with just a few threads of others, rather than simply adding them on top of each other. ‘D and C for Orchestra’ is intended to evoke city buildings; these replace the forests and fields of the Romantic repertoire. It also suggests a dance, returning regularly to a pulsating theme driven by double basses and contrabassoon and heightened by a clanging triangle and massive brass forces. Passages in ‘D and C for Orchestra’ recall the fatal dance in Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, and the music for his The Soldier’s Tale, with their dynamic, irresistible energies and the sense of the inevitability of the drama of life being played out.

Generally, this was a splendid performance of an immensely difficult work. The orchestral elements are frequently an amalgam of disparate sounds and textures that do not depend on thematic or harmonic development, and strict direction is required to keep the event together. Expressionistic music of this kind requires concentrated effort by every performer. The work itself is metamorphosing, for example new elements were added in this performance and the sequence was quite different from the CD version (ECM New Series 1688 465 338-2). The soloists were superb—David Moss’ vocal range is prodigious, from baritone to countertenor. Goebbels’ writing would be unrealisable without such a performer. Smith and Moss are not merely singers. Some of the texts Moss delivered were babble, a meaningless abstraction of the sound rather than the content of conversation, recalling the work of Berio, and requiring consummate skill to bring off. Smith’s performance was superb; both are vital to the success of the work. On stage, their presence is dramatic, operatic in its intensity.

Heiner Goebbels has created an extraordinary synthesis out of a disparate array of musical forms and instrumentation. Surrogate Cities is a masterpiece and a fitting opening to the Queensland Biennial Festival of Music.

Heiner Goebbels, Surrogate Cities, The Queensland Orchestra, conductor Andrea Molino, Concert Hall, QPAC, July 18

RealTime issue #58 Dec-Jan 2003 pg. 42

© Chris Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Gail Priest opened the show. A couple of laptops, logos glowing in the darkness. Priest’s work involved live mixing of samples, and some text to speech improv. Beautifully paced set, starting slow with spooky wooo-wooos, scissors working, clanking train journeys with delays. The limited palette produced coherence with just the right amount of variation. The text to speech was hard to decipher at times, losing semantics to become punctuation for the underlying drones. One highlight of the set was the use of very deep register tones—sub-bass better than I have previously heard, no oscillating feedback boom resonating to the architecture, just clear and large. At the end, the lid goes down, and the machine shuts down.

Bruce Mowson then introduced his work with a slyly disarming apology. He told us that it would be fairly static, a case of turning a sound on then waiting 12 minutes for it to end. Ready. Set. Go. The sound jumped out like a real bastard, harsh pumping machine noise full on into the head. And it kept on coming, no let up, no change. Except to the listener, modulating their attention to the relentless interplay between room acoustics and sound source. Only criticism was the volume—too loud. Consult that audiologist. I joined many others in putting my fingers in my ears about halfway through. But quality music. And then it stopped.

Lawrence English and Philip Samartzis then stepped up and improvised some statics and circuits. Beginnings were gradual, slow microsounds from the turntable, walks on moist gravel. Some sine waves wandered in and got close enough to set up interference. Sounds of foraging and late night listening to something scrabbling inside the wall. Not so much overt structure in this performance. More crafted sounds and obsessive tweaking. Fine motor control. Rifling through cases of white label CDs.

After the interval came the grand old man. Bernard Parmegiani, pioneer of tape music and loops when loops were rings of physical tape, not a method for addressing files. Parmegiani mixed 3 stereo tracks from CD across all the speakers of the diffusion system to get those sounds moving through the space. Worked a treat, much better than just playing straight stereo.

The pieces came in chronological order. First up was Capture Ephemere from 1967. I’d forgotten how much I missed the rich sound of analog tapes. The piece had an economy of means that strengthened its impact. Speed changes and echoes, cut and splice. Next was Rouge Mort from 1987. Nightbirds. Wind. Trees. Hipster bongos and violins. From natural to abstract and back. 17 minutes of sonic and dynamic variety. Last up was Les Memoire des Sons from 2001, a more electro-acoustic work using the sounds of bells, the wind, blowing through pipes, accelerating to create headlong rushing and hurtling through electro-acoustic space.

Liquid Architecture 4, Brisbane Powerhouse, July 19

RealTime issue #58 Dec-Jan 2003 pg. 43

© Greg Hooper; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Timothy O’Dwyer’s and Lilla Watson’s composition, Sight and Sound of a Storm in Sky Country (2003) is a collaboration in which Watson, an Aboriginal artist, has made an artwork in response to a piece of music by O’Dwyer, and the composer/performer O’Dwyer has then made a new piece of music for electronically mediated saxophone based on, or as a response to Watson’s artwork. That artists should respond in such a way to each other’s work is not unusual. For example, we know of Mondrian’s interest in jazz. What is significant here is the cross-cultural nature of the work and the active collaboration between 2 artists who have both reconsidered the forms of their cultural traditions and synthesised something new and different. Instead of using traditional pigment or modern acrylic paint, Watson’s artworks are made by burning rows of small holes in layers of heavy drawing paper and adding a further layer of coloured papers beneath that are visible through the holes, the colours evoking sky, water and so on. The paper around the holes is scorched by the burning process in a controlled way, creating motifs. Thus the artworks are highly symbolic—not only do they tell the story of Watson’s country, but they also symbolise for a wider audience the use of fire to pierce and to mark, and the importance of the trace (of the smoke) and the rituals in traditional art. The layering of the papers also suggests a metaphor for the layering of cultural and traditional forms, the ‘true’ colours found beneath the pierced, blank surface.

Watson’s work is an abstraction that parallels the abstract forms of another culture, providing common ground on which both artists can reach and greet each other. O’Dwyer’s musical response to Watson’s art is itself heavily layered and is concerned with the physicality, almost as ritual, of the performance. The O’Dwyer/Watson work is significant musically, and makes clear the value of experimental and developmental composition. Such a work can be appreciated not only in terms of musicality and form but also due to its symbolic significance within wider cultural contexts. O’Dwyer’s performance of the music, in front of the projected images of Watson’s works, was captivating.

Elision, Burning House, Powerhouse, July 20

RealTime issue #58 Dec-Jan 2003 pg. 43

© Chris Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The concert finale was Rautavaara’s 1979 setting of the Magnificat, a more darkly brooding piece than the lighter, earlier works. Sung in Latin, the voicing included a countertenor, and the soprano solos were hauntingly beautiful. The work alternates powerful, gestural statements with softer passages to build drama. Lines are sung in parallel with spoken text evoking an angelic chorus. But this work was not the finale after all, the audience volubly demanding an encore. The choir chose another Finnish hero, Jean Sibelius, and offered 2 of his works, the latter a choral setting of Finlandia. Culminating in a single melodic line that reaches a powerful crescendo, Finlandia was intense and moving. One wondered how many in the audience might have wanted to join the choir in singing what amounts to a Finnish anthem. The Kampin Laulu 23-member choir was superb, creating an ethereal sound that filled the gracious St Mary’s, the voices clear and balanced.

Ethereal Voices: The Music of Einojuhani Rautavaara,Kampin Laulu Chamber Choir

St Mary’s Church, Brisbane, July 23

RealTime issue #58 Dec-Jan 2003 pg. 43

© Chris Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Monk’s melodic style is like no other, but has connections to an enormous range of music; it embraces the notion of music as a universal language. The voice is perhaps the primary musical universal—all peoples sing. To explore the voice as a musical instrument (she calls it “the original musical instrument”), to produce an astonishing range of sound colours and in settings that suggest ritual, is to join a very ancient tradition that nevertheless sounds utterly new. A visitor from 50,000 years ago could relate to this music, but it has also been on New York’s cutting edge since the 1960s.

This makes the music an excellent vehicle for the themes embraced in Mercy, the experience of giving, receiving and withholding compassion. A highlight, for example, is a duet between a doctor and patient, ending with the sung word “help” repeated by both. The voices intertwine to become a single sound, Monk making virtuosic use of the hocket technique so beloved of medieval troubadours and West African singers, where the notes of a single melody are divided between 2 or more performers.

At other points in Mercy, sounds are passed around the whole ensemble (2 male and 2 female singers, piano, percussion and clarinets, with the instrumentalists contributing vocals) creating a mesmerising spatial effect. In “Liquid Air”, pairs of kneeling singers sway around each other, the sound moving between and seeming to wrap around them.

In Shaking, dance and music are married completely—the movement and sound are inseparable. The singers shake their heads from side to side while rotating their bodies, creating constant pitch shifts and tremolos. The effect is both disturbing (with its appearance of insanity) and absorbingly beautiful.

Monk’s troupe of performers are extraordinarily devoted. They constitute a whole singing tradition of their own founded on Monk’s inspiration. And they share great virtuosity (I was particularly impressed, for example, by Theo Bleckmann’s precise, clarinet-like head voice) and theatrical, whole-body sensibility. The camaraderie and community was palpable. The 3 instrumentalists embraced the performance whole-heartedly, contributing improvisation, playing multiple instruments (pianist Allison Sniffin often joining the vocals, and also playing violin; clarinettist Bohdan Hilash performing on all clarinets from piccolo to contrabass) and inventing new sounds (percussionist John Hollenbeck coaxing complex overtones by playful use of a microphone and cymbals).

Meredith Monk: Mercy, Brisbane Powerhouse, July 25-26

RealTime issue #58 Dec-Jan 2003 pg. 43

© Robert Davidson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Porch and Woo-la weh from Monk’s 1977 work Songs from Hill have a folk-based melodic progression exploring vowel sounds. Vowels and notes seem completely interlinked, in symbiotic relation. Her Insect Songs investigate some of the harsher edges of the voice, the first using a dry throaty static, the second ringing out nasal tones accompanied by playful gesture. Movement is inherent in the production of the sounds and Monk adopts a different body position and attitude for each piece, like the open-chested exuberance of Bird Code. Of these unaccompanied works the most impressive were the Light Songs from 1988, duets for solo voice, like Click Song 1 with its soft-palette humming accompanied by its own rhythm track of tongue clicks and tocks. The jawharp piece from Songs from the Hill was also a highlight with beautiful manipulation of vibration and harmonics.

These early pieces set the conceptual framework for Mercy, performed in a pared-back concert version but with a distillation of choreography, spatialisation and gesture to evoke a sense of the depth of the work. Mercy begins with Monk’s expanding arpeggios and the haunting tones of disembodied voices perfectly underpinned by the bowed vibraphone. The other performers join Monk for the collective calling of “leaping song.” It feels like a summoning. The ensemble is virtuosic—expansive voices with constantly shifting qualities and gloriously minimalist piano cycles augmented by perfectly placed woodwind and percussive lines. Of particular beauty are the reflective drone interludes performed by John Hollenbeck for cymbal and microphone. The highlight of the piece is doctor/patient, an astounding duet between Monk and Theo Bleckmann of syncopated vocal leaps and yelps for help, one of the few ‘words’ in the opera. Bleckmann and Monk go note for note, their voices so tightly plaited that you can’t tell whose voice is whose. Each segment of Mercy is divine, with shifts of tone and context, investigations of each singer’s vocal qualities, and the astounding beauty of the voices slipping around, melding and then separating again. Monk has written a cry for compassion that sinks into the flesh and dwells in you.

In the artists’ talk following the performance, Monk lets us in on some of the imagery created by Ann Hamilton for the fully-staged work, including a mouth held video camera, huge sheets of bubble membrane and paper cascades. You can’t help yearning to see Mercy in full production (the same goes for Laurie Anderson’s recent concert tour of Happiness), however the meticulously presented concert version is a rewarding and inspirational experience.

Meredith Monk: Mercy, Brisbane Powerhouse, July 25-26

RealTime issue #58 Dec-Jan 2003 pg. 43

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

ABC Management has axed The Listening Room. ABC Classic FM has cut New Music Australia. Aside from Critical Mass and the occasional new arts documentary, ABC TV does little to embody the vibrant Australian arts. There’s something toxic in the organisation that’s invaded the broadcaster, eating at its art, destroying vital organs, impelling it to cut off its ears and gouge out its eyes, rendering it a near comatose, cosy-chatshow, personality-driven hulk, drained of the diverse riches that once were its life blood.

Despite the depletions it too has suffered, Radio National still manages to ingest and convert the world into rich aural sustenance but how long before the virus strikes there too? What has caused this hideous illness? Is it an agent from the outside or is it something immunological of the ABC’s very own making, hollowing it from the inside out?

It would be easy to blame the Howard government: sure it provides the sickly environment of funding deprivation, editorial trepidation and the dumbing-down fear of being labelled “elitist.” And yes, this year’s refusal by the Federal Government to properly fund the national broadcaster led, much to Senator Richard Alston’s chagrin, to the unplugging of the ABC’s new digital prostheses. But other savings had to be made. What were the solutions? Abortion— removal of the cadet training program—and sterilisation—cut out the ABC’s capacity to make art, remove the internationally acclaimed, prize-winning (2003 Prix Italia) Listening Room made by sound artists and composers from across Australia and its richly creative team of producers.

Of course, the ABC is no stranger to self-mutilation insanely lopping off an ear when it banished stereo radio drama to mono broadcast and conducting a home lobotomy with the excision of Arts Today. Julie Copeland on Sunday mornings and Andrew Ford on Saturdays just keep the arts brain ticking over, but can they live up to the prodigious Australian arts output? Why remove The Listening Room at a mere one hour a week! If it was a matter of cost, as smugly proposed by The Sydney Morning Herald’s The Guide (Nov 10-16) why not re-think, re-shape, re-budget? How about some holistic solutions for improvement? To toss it aside is to discard a living part of our culture. Where are the micro-surgeons of ABC management? Pick it up, put it back!

The Listening Room is living, contemporary art, exemplary of sound art and new developments in the generation of multimedia and hybrid art forms. As the concert hall future narrows and technologies provide new compositional tools and broadcast media, this program offers composers new ways of working. It provides established international links and outlets for Australian art. Each year an emerging artist is awarded a 6-month fellowship with The Listening Room, jointly offered by the Australia Council’s New Media Arts Board and the ABC. The associated Adlib project created by Jon Rose is archiving an astonishing collection of the ways all kinds of Australians make music. Cut out The Listening Room and you lose all of this, you do irreparable damage to the body of the ABC, the body of Australian sound art, the body of Australian culture.

The admirable New Music Australia on Classic FM plays music both accessible and challenging, recorded and, importantly, live and provides significant interviews with leading composers (a handful still downloadable from the no-longer updated ABC arts web gateway). It seems that the program will be dissected and its parts grafted onto Classic FM here and there in the hope that listeners will accept more Australian music if it becomes a part of the everyday listening experience. A lot will depend on the surgical cunning of the programmer—will the listening body tolerate an invasion of the unfamiliar and the sometimes innovative, and at what time of the day? Will the voices of living composers and musicians be allowed to interrupt wall-to-wall classics and, if yes, for how long? Will new music continue to be played live, and how often? If the transplant is rejected by audiences, what has the operation achieved? Will ABC middle management have the nerve and arts nouse to persist with a higher quota of Australian music in the face of possible bad reaction?

Again it has to be asked why the radical surgery? What’s wrong with a specialist focus on developments in Australian contemporary music in a specific timeslot, a place the listener knows they can visit. Yes, Australian music has come of age, but the mature body still needs a good solid workout, not short runs off the leash.

The death of programs like The Listening Room and New Music Australia is just more bad news for Australian artists at a time when David Throsby’s report for the Australia Council on artists’ incomes (Don’t Give Up Your Day Job) reveals high levels of poverty. With the exit of The Listening Room there will be substantially reduced commissions. The ABC may continue to make artful mini-series, comedies and documentaries but they hardly represent the full extent of the broadcaster’s capacities. When Throsby launched his report he decried the absence of an Australian cultural policy. When the ABC fails to live up to its charter “to reflect our cultural diversity” (that’s for SBS isn’t it?), to contribute to a national sense of identity and produce cultural enrichment, it appears to have no consistent cultural policy (Art is now subsumed to Entertainment in the ABC hierarchy). At times like this, it seems that achieving a cultural policy for Australia is about as likely as a policy on human rights—then we really would have to address the refugee issue.

The cultural health of the ABC used to be reflected, as the charter puts it, in its “balance between broadcasting programs of wide appeal and specialized programs”; the result was tremendous choice. Its vision of Australia was not ratings-driven. It was for all Australians, a truly diverse bunch, not a bland mass of homogenous bodies. Now the generalist position prevails with ratings clearly governing programming decisions. Lifestyle shows supplant arts programs and almost everywhere on radio live talk is easier than crafted programs and a lot cheaper—and sounds like it.

Deaf in one ear to radio drama and stone deaf to audio art, and in danger of tuning out to new music, will the ABC stop listening to Australian artists altogether? If so we might as well sign that free trade agreement with the US and get the selling off over and done with. What is needed is a coherent cultural policy so that art is assured of its place within the ABC and our national broadcaster regains its cultural well-being. KG

Happy Holidays

To all of our readers, writers, contributing editors, advertisers, subscribers and the funding bodies who generously support RealTime+OnScreen, we wish you a Merry Xmas and a creative 2004. ‘Prosperous’ is not a word thrown around casually in arts circles, but if you’re feeling flush think about treating yourself or a friend to a RealTime subscription for 2004. We’d really appreciate it and we trust you will too!

Virginia, Keith, Gail, Mireille, Daniel

RealTime issue #58 Dec-Jan 2003 pg. 3

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

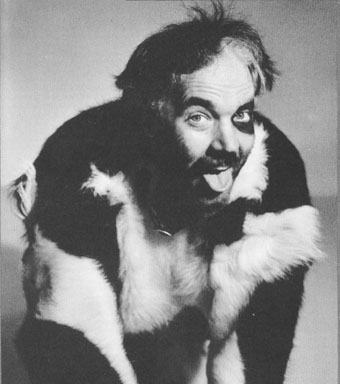

Societas Raffaello Sanzio, BR#04, Tragedia Endogonidia IV Episode

KunstenFestivaldesArt, Brussels, May 2003. Thirty innovative projects, 20 world premieres, 15 venues, over 3 weeks in one very edgy city. Time is of the essence. And it’s not just my experience of ‘festival time’, which always seems distorted, what with the early morning bedtimes, the running late through dark, unfamiliar streets and the twilight zone of entire days spent at the theatre. Time is a theme and an obsession in much of the work I see at Kunsten, offering structures and perceptions to interrogate and subvert.

Rushing from the airport I thankfully arrive on time for the latest offering from Societas Raffaelo Sanzio. BR#04 (IV Episode of Tragedia Endogonida) is the 4th part of a dramatic cycle to be presented over 3 years in 9 European cities. Director Romeo Castellucci’s aim is to investigate the traditions and mechanics of tragedy and reinterpret them in each city into the world of the here and now.

In Brussels, a large white marble room (perhaps it’s the lobby of some bureaucratic office at the headquarters of the EU) becomes the laboratory in which a series of scenes examine the duration of the body through life and time, from conception to death. Some of the images are devastatingly direct; the curtains open to reveal a baby lying on his belly. He is left to cry for 3 or 4 minutes. The curtains close. Other scenes are thick with complexity: apocryphal text, ancient and macabre rites, ominous figures who flash through the phosphorescence. I get the feeling that I’m not witnessing these astonishing images for the first time, but that they have been mined directly from my own or some collective subconscious, some shared dreaming. In one scene 2 policemen bludgeon a young man to death. The company is disinclined to suspend my disbelief. I watch them repeatedly apply fake blood to the young man’s skin. It spreads as he writhes. Each time he is struck the theatre shakes with violent synthetic sound and every blow to his body resonates through mine from sheer decibel power. The mechanics of theatre become the tools of brutality.

Tickets for the festival are, by Australian standards, incredibly cheap, and highly prized. Every event is full. One of the festival staff tells me that a woman who arrived late to a show because her husband was trying to park the car, threw herself screaming at the theatre doors and refused to be removed when she discovered her tickets had been resold.

The show she missed was Christoph Marthlaler’s interpretation of Schubert’s lieder cycle Die schöne Müllerin (The Fair Maid of the Mill). Bypassing the original performative context of the recital, Marthaler dramatises the cycle in a severe flat salon, a kind of rundown eastern bloc apartment, where a troop of listless nobodies mooch with seemingly no purpose, biding time with their songs of romantic yearning and loss. The staging, full of physical comedy and absurd imagery has a kind of anti-structure, which is at odds with and entirely complementary to the music.

Most of the ensemble are not professional singers and I was particularly moved by their imperfect voices. It is as if these characters have more to lose, mainlining the audience to the fragility inherent in the songs. There’s a compelling rhythm and sense of time at work. Where, in a conventional lieder recital, Schubert’s music would provide the dominant time structure, Marthaler has employed a choreography designed to work against it. Certain songs and actions are repeated again and again, or drawn out to be painfully slow, some characters disengage mid-song and go and hide in a cupboard or sleep in an enormous feather bed. Time dilates, warps or suspends.

Edit Kaldor explores the experience of cyber-time in her ingenious solo Or Press Escape. On entering the theatre we see her sitting alone, her back to the audience, in front of her computer’s giant screen. The only sound is the amplified staccato of the keys as she types. She records last night’s dream, makes ‘to do’ lists, tidies her desktop, receives mail, downloads files, deletes them, empties the trash. It’s an unlikely script, but this silent text is utterly theatrical. Solitary thoughts are made explicit, censored and unwittingly betrayed. At one point Kaldor enters a live chat room and for the first time we see her face via the web cam on her desk, illuminating a wonderful tension between the smallness of her body sitting in the half-light and the expansiveness of her projected cyber-self.

My highlight is 5, a timed journey through a series of installation/performances created by Kris Verdonck and Aernoudt Jacobs. Their work attempts to reduce to an extreme the codes of visual and performing arts, allowing the essence of each code to inform the other, producing a hybrid form, a distillation that achieves an exquisite impact. In one installation, IN, an actress dressed as a French maid is submerged in a tank of water. She breathes via a tube connected to air canisters outside the tank. Microphones amplify her breathing and the slight movements of her body. Her senses have been distorted: she is in a trance. In another, To Sleep we enter the tiny room to discover 4 people asleep on transparent cots. They have altered their body clocks and undergone hypnosis to actually be asleep. The initial impact deepens through the 20-minute duration of each piece. Our subjective responses begin to write the narrative. In the room with the sleepers, first we creep and whisper, then sit in silence on the perimeter, ‘performing’ with as much authenticity as those we are trying not to wake.

KunstenFestivaldesArts, Brussels, Belgium, May 2-24, 2003

Die schöne Müllerin, co-production KunstenFestivaldesArts and Schauspielhaus Zürich, direction Christoph Marthaler, set & costumes Anna Viebrock, Halles de Schaerbeek, Brussels, May 6-8

BR#04, Tragedia Endogonidia IV Episode, Societas Raffaello Sanzio, direction, set, lighting & costumes Romeo Castellucci, vocal sound & score Chiara Guidi, writings Claudia Castellucci, music & live execution Scott Gibbons, La Raffinerie, Brussels, May 4-7

Or Press Escape, concept, text, performance Edit Kaldor, Kaaitheatrestudios, Brussels, May 5-9

5, concept Kris Verdonck, sound Aernoudt Jacobs, performance for IN Heike Langsdorf, BSBbis, May 11-15

RealTime issue #58 Dec-Jan 2003 pg. 4

© Lucy Taylor; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

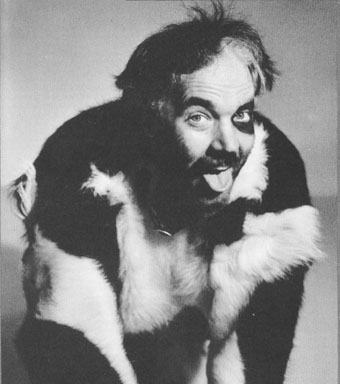

I Am Blood

photo Philippe Delacroix

I Am Blood

I Am Blood has 2 dramaturgs listed in its credits. It is curious this fascination with and increasing dependence upon the dramaturg over the past couple of decades. These dramatic architects, these advisers and guides in the architectonics of theatre: the systematic arrangement of knowledge. With the unities of time, place and action, with the hero’s journey from unknowing to experience via the monster’s cave, with the lineal chain of cause and effect to anagnorisis and perepeteia etc etc, there was/is an underlying arrangement of experience, so that the various stories laid upon the top produced variations upon old (and deeply resonant) themes of individual and personal (re)organisation. Not so with so many contemporary performances: Teshigawara’s I Was Real: Documents, Needcompany’s Snakesong, Castelluci’s Giulio Cesare and Genesis, to mention only some of those that I have written about for RealTime over the past few years. And now the ‘anxiety of formlessness’ caused by Jan Fabre’s I Am Blood. They are not easy to absorb. They are impossible to fit into any recognisable structure. They feel carefully fashioned but without any underlying form; and maybe (horror!) this equates to surface without soul.

The Age reviewer Hilary Crampton concluded her review: “As Art, the work fails, because it lacks any sense of selectivity, of form and structure, resulting in an indulgent presentation…” Neil Jillett in the Sunday Age dismissed it as “a spectacular display of chaotic nastiness…poorly choreographed…a bloody shambles.” (Interesting that the word ‘shambles’ which, figuratively, has come to mean “a mess, a muddle”, was originally the word for “a butcher’s market-stall, a flesh market, a slaughterhouse.” Jillett’s description was more apt than perhaps he realised.) For many of my friends and fellow artists it was a ‘mess’, ‘studentish’, ‘obvious’, ‘lacking directorial control’ etc. There’s something going on here, some kind of extreme concern. Hence my term ‘anxiety of formlessness’ to describe the effect it has caused. And I’m not saying I was immune to it: alternately enthralled, confused, thinking I understood it, bored, excited and shocked etc.

Fabre’s show in 1984 was called The Power of Theatrical Madness—in that title he stated a mission which he still adheres to. Hans-Thies Lehmann describes it thus: “Theatre was and is searching for and constructing spaces and discourses liberated as far as possible from the restraints of goals (telos), hierarchy and causal logic. This search may terminate in scenic poems, meandering narration, fragmentation and other procedures…on the borderline of logic and reason.” (Performance Research, Spring 1997). Fabre is also a visual artist: a sculptor, graphic artist, installation artist and video maker. The pressure of the experimentation in the visual arts pushing against the tenacious borders of theatre can be felt in I Am Blood.

The beetle has been a fascination of Fabre’s for many years, in art and theatre. Beetles wear their skeleton on the outside. It is their defence against the penetration of the flesh. Near the beginning of I Am Blood a chorus of men in armour dance a mock chorus line number while one in their midst spins out into a crazed ‘structureless’ sequence in which armour and sword are no longer defences but potential for self-damage. On reflection, the show seems as much as anything to be a meditation upon the act of shedding and covering. The bodies cover themselves with armour, wedding dresses, ordinary clothes, only to take them off again and again revealing the vulnerable flesh (and blood) underneath. Suction cups are placed on the body, only to fall shattering on the floor, the shards swept up presumably to protect bare feet. More metaphorically, steel tables are alternately used as platforms for human display and surgical benches for bodily desecration. I think of the jeeps and tanks and helicopters in Iraq, supposedly providing armoured protection to the ‘invulnerable’ US troops, but ripped away increasingly by bombs and missiles to expose the flesh of the soldiers underneath. We are still kidding ourselves like beetles do. We are still medieval.

The ultimate protection, of course, is the word, which can justify and sanctify and give a sense of order to every mad thing we do to one another—in the name of the father. The show begins with 2 figures sharing the stage. One is the fearless, mainly naked, seemingly sexless, curly-headed contortionist who is witness to all the theatrical madness that proceeds, who attempts to send it all up, and who ends with his nakedness covered in feathers. The other is the woman with the book on her head. She is the word provider throughout the play. It is she whom we first see and she ends the show as she began it, parading around the stage, confronting us, the book as both weight to carry and armour against whatever may drop from above.

Paradoxically, whilst it resists the recognisable forms of dramatic progression, I Am Blood is made up of images and sequences of exquisite formality, set against sequences of seeming chaos. It is in the progression from one to another that the rationality—the ability to make meaning of it all—breaks down. Lehmann has called this “the aesthetics of poison”: “An image of beauty, craving and desire is presented, but with the addition of a disturbing element, a vivid poisonous green tinge of colour…(which) spoils my enjoyment, while at the same time stimulating it to reach a different level of reflection.” How to reach that level is the challenge these works of ‘mere anarchy’ place upon us.

–

I Am Blood, writer, director, choreographer, Jan Fabre, Melbourne Festival, Oct 9-25

RealTime issue #58 Dec-Jan 2003 pg. 5

© Richard Murphet; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Der verlorene Atem

Director Barrie Kosky’s Australian productions were marked by profuse energy and inventive, often deliberately excessive amalgamations, drawing on expressionism, German language cabaret and Yiddish culture. Although these sometimes seemed wrought only from a rearrangement of these antique references spiced with garish postmodernism, the results were compelling. Kosky’s current Viennese pieces in his new role at the Vienna Schauspielhaus are sharper and sparer but somehow less embracing.

The word about town was that Der verlorene Atem was not Kosky’s best Schauspielhaus show. Though a masterpiece of precision and evocative restraint, it was unsatisfactory as theatre—largely because it offered much but delivered little. Kosky drew on Kafka, specifically the instrument of tortuous punishment and the Law described in The Penal Colony and the destabilising self-transformation in Metamorphosis. Like much of Der verlorene Atem though, these rich motifs became throwaway ideas within a performance mostly devoted to the expressions layered within the strained female voice.

The piece began beautifully, with actor Yehuda Almagor playing a digressive Jewish Houdini, chatting charismatically with the audience about his “apparat” which contained Kafka’s ambiguous machine. Almagor unbuttoned his shirt in wan light while singing in Hebrew, suggesting that this appalling device might offer the transcendence that its victims desired. In Act 2, 4 variously costumed tap-dancers performed German, Yiddish and Broadway cabaret tunes outside Houdini’s former cabinet. Metamorphosis’ protagonist Gregor remained hidden inside this Tabernacle, but rather than depicting Gregor’s family confusedly dealing with his change, Kosky’s unseen Gregor was represented as a playful, growling-voiced participant in his relations’ light musical games, interjecting lines into songs otherwise unconnected to Kafka’s themes—an amusing interlude, but not much more.

If the second act constituted a fraying of Kosky’s theatrical conviction, the third signalled its abandonment. The audience was presented with nothing but almost immobile performers, caught in nebulous spotlights, singing Robert Schumann’s ode to lost love, Dichterliebe, in German. As one spectator quipped, a recital is fine, just don’t call it theatre. The performance was beautifully modulated in playing-off broken voices with operatic fullness, but this was not a well-conceived conclusion. As another spectator observed, yes, we all end up feeling like we’re locked in a box, alone and unloved—but this is a banal final message for a piece subtitled: A Kafka evening in 3 acts (Ein Kafka Abend in 3 Akten).

While Kosky staged a cabaret recital misrepresented as theatre, Melbourne’s Aphids offered 2 fine music performances which stretched (though did not break) the recital form. Skin Quartet, composed by David Young, used various graphic and notational methods which were then incorporated within Louisa Bufardeci’s accompanying projections derived from close-ups of skin tones, tattoo-like shapes, and maps rich in the patina of cultural history. Young kept the arrangements integrated and softly flowing, despite the composition’s post-classical basis, with interjections and exclamations largely resting easily within the overall sound, rather than cutting across it. This produced a beautifully seductive effect, but it did mean that all the musical ideas seemed to have been introduced about two thirds in, while only deferentially alluding to the racial politics foregrounded by the visuals. Skin Quartet was nevertheless an exquisite gem, sitting well against Aphids’ more variegated Fight With Violin.

Fight showcased 6 contemporary pieces for solo violin ranging from Motoharu Kawashima’s fun, John-Cage-esque instruction piece (rub violin on top of head, end performance with empty stage and a recording of a classical piece) to Kate Neal’s almost romantic sketch of melancholy, sour notes. Yasutaka Hemmi performing in a Japanese armed martial arts dojo, complete with demonstrations enhanced the novelty of these rarely seen works. The audience had to draw its own conclusions about what this combination suggested (the sound of a swiftly drawn katana blade generating a cruel tension in Neal’s work, for example). If nothing else, the staging added firmly poised, meditative bodies to such aggressively avant-gardist compositions as Helmut Lachenmann’s pointillist scrapings.

Dumb Type’s Memorandum was particularly energised by its paradoxical performativity. Video documentation of their 1994 Adelaide Festival production S/N suggested that Memorandum was a weaker work, while dance purists were nonplussed by the its movement elements. These criticisms missed the heart though of this extraordinary, totally overwhelming and wry, yet impersonal, work. At a sonic level alone, the monumentally forceful, finely tuned and shaped white-noise assaults and the repetitive, purified sine-waves of Ryoji Ikeda were sublime in the wonderful audio mix—I melt at Ikeda’s combination of carefully nuanced violence and electronic minimalism.

Dumb Type’s formation in 1990 epitomised the supremely manufactured and designed aesthetic of the Japanese “bubble economy”; the company’s productions today restate the familiar motif of the postmodern individual, a self sublimely dispersed throughout culture, language and technology. Dumb Type was however always guilty of presenting style over substance—indeed, style as substance—so such a summary does not do justice to its consummately slick form, produced through sound, action, multi-screen projection and shadow play. The company’s approach transformed the arguably antiquated technique of performance art (as in Jan Fabre’s I Am Blood) into a glistening, plastinated extrusion.

The company masterfully achieved an astonishingly clarified, controlled aestheticisation of banal actions, thoughts, experiences and metaphors. Everyday events and ideas were rendered strange on stage not through the manipulation of content, but through the form and framing of the work. A man sketched his room, trying to remember each piece of furniture, which then magically arrived. But it was the mundane details beautifully cast into relief by these acts that were significant, not what this act said about memory. I was entranced as each new gesture of writing made a sharp line in the creases of the man’s pressed, red shirt. Such exquisite minutiae of the everyday framed an act of play so serious in its simplicity of execution that it became both transcendent and funny. Dumb Type may be trapped in an aesthetic cul de sac, but remain nevertheless impressive. Memorandum was destined to appeal to those who marvel at simple things well presented, such as the donuts, coffee and pie that pervade David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, Laurie Anderson’s USA Live or Quentin Tarantino’s gangster cinema.