Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Hypersense

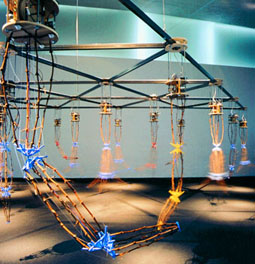

Across 4 Friday nights in February, if you shot down to Acton Peninsula, site of the National Museum on Canberra’s Lake Burley Griffin, you’d be among some of the funkiest new media worlds in The Garden of Australian Dreams. Sky Lounge 2004 was the third in a series of February multimedia mini-festivals. After heat-wave late summer days edged with gold-rimmed mountain lines, you could sit back beneath luminous skies, chill out, eat, drink and get into the slow-lane groove. Alternative, surfy, homie, artsy, under-age, over-age; in the lights we’re all green, all red and we all get along. There’s nothing to really compare.

Listen to electronic artists and DJs making music. Experience visual and music installations in The Tunnel. Watch animated flicks from the hill, plopped on beanbags (if you’re lucky), in between dingo, cyclone and backyard fences. Short films curated by Malcolm Turner (Animation Posse), projected onto a white box known as The House of Australian Dreams, framed by palm tree fronds in the middle of the garden. Or make little sorties to K-Space, featuring the best of interactive and linear new media. The open-air acoustics were surprisingly good and everyone could talk as well. Your own pace was the right pace.

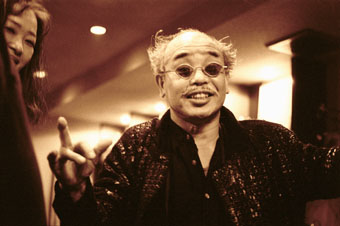

The highlights of the two final nights? Hard to pick, but here goes. Green Night: the HyperSense Complex in The Tunnel, an intoxicating mix of predetermined, programmed music and finger-puppet, gestural movement (or not), an experience of art-as-it-happens, with random events including people unintentionally wandering into the generated space. Hallucinatory choreography on the go. And a couple of animations: Grey Avenue (Eugene Foo, Australia), in which buildings morph into creatures (you want to take them home), and Ward 13 (Peter Cornwell, Australia), an hilarious projection of all-out hospital fear with a faux ‘wheelchair’ chase par excellence.

Red Night: watch Red Thread (Jo Lawrence, England) a can-opener ties up a woman with red string. Then an animation closer to home: It’s Like That (Southern Ladies Animations Group, Australia) features the voices of children in immigration detention camps, showing us their world. The animations come to an end and we’re told to move back so we’re not skipped on…

Ladiez of the Jump Rope are hop-hop hip-hop with smiles, clever rhymes, sexy legs. Juxtaposing rhyme, dance, singing, skipping, hopping and break-dancing, the Ladiez play out a fight between ‘Asians’ and ‘Whities’ at a school camp, concluding with a skip-out battle. Pony M of the Ladiez says: “We don’t take ourselves too seriously.” This attitude shines in their playful rhymes and sing-song taunts. The Ladiez are innovative hip-hoppers, dealing with contemporary themes with an ease and confidence that charms the audience.

Somebody whispers: “You light up a dark room.” And we smile. Time to go home.

Sky Lounge: the future friday 2004, National Museum of Australia, Canberra, Feb 6, 13, 20, 27

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 43

© Francesca Rendle-Short & Clare Young; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

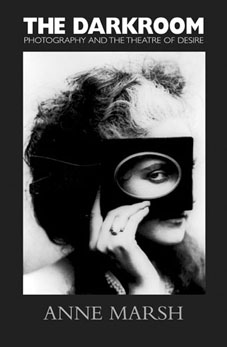

Anne Marsh, The Darkroom: Photography and the Theatre of Desire, Pan Macmillan, Melbourne, 2003 ISBN 1 876832 78 9.

Anne Marsh, The Darkroom: Photography and the Theatre of Desire, Pan Macmillan, Melbourne, 2003 ISBN 1 876832 78 9.

Those 19th century photographs in which the dearly departed seem to hover translucent and spectral beside the living are wonderful examples of the link between photography, desire and performance. While the living sought to souvenir one final glimpse of their dead, the spirit photographers who ‘staged’ such portraits profited from the huge popularity of an industry featuring “death and its accoutrements.” The popularity of Victorian funeral and spirit photography was part of a widespread “reaction against a rational modernity,” writes Anne Marsh in her new book The Darkroom.

Photography, Marsh writes, “is a performative representational practice that has aspects in common with theatre.” This approach is at the centre of her discussion of a range of historical and contemporary photographs and re-readings of some key critiques of photography. A senior lecturer in Visual Culture at Monash University, Melbourne, Marsh’s approach is heavily theoretical and most engaging and lively when specific photographs are used to bear out the critical concepts with which she is concerned. In a chapter on spirit photography, she describes how theatrical techniques, ritual and artifice are used in particular images which often mobilised dramatic swathes of light and darkness to symbolise the movement from one world to the next. While it’s not hard to detect the theatrical in the ethereal poses and framing of Julia Margaret Cameron’s otherworldly portraits, in the composite spirit shots of William Mumler or the dramatic snaps of mediums oozing white ectoplasmic emissions mid-séance, Marsh is also interested in teasing out the complex operations of desire in “the operator, the subject being photographed and the viewer looking on.”

While Muybridge and Marey’s movement studies were perhaps the first form of performance documentation, Marsh traces the performative aspects of photography back to the camera obscura and other 18th century optical devices which staged an experience like a private theatre. She writes:

One imagines the eighteenth century viewer, alone or in a small party, standing about in his or her darkened room trying to see the picture from nature in much the same way as people gathered at shop windows displaying the latest three dimensional computer enhanced puzzle picture in the late twentieth century. People move back and forth, trying to adjust their eyes, trying to get the best optical location…Then, as now, the body is the flexible seeing apparatus, the thing that moves about and alters the image, enhancing the body’s experience.

Theatrical effects are also evident in the supposedly factual realm of early documentary photography. Marsh details how American photographer Jacob Riis manufactured dramas to intensify the action in his 19th century New York slum photographs. In establishing photography’s essentially performative nature, Marsh writes, we can “acknowledge that the subject/object of the photograph can perform as a way of un-forming or de-forming the would be truth and objectivity of the photographic process.”

The Darkroom is primarily concerned with this issue of ‘staging’ in both contemporary and historical photographs and in the key critical discourses produced around photography from Benjamin and Barthes to Foucault and Lacan. Marsh argues against a reductive reading of Foucault’s theory of the panopticon that has at times produced a “paranoid discourse” on power relations and ignores the complex interrelationship between desire, seduction, fantasy and performance involved in the taking, posing for and viewing of a photograph. Arguing against a structuralist approach to photography, she maintains that the practice is not “exclusively the tool of any given dominant ideology” but ultimately democratic.

This mode of inquiry allows for a greater scope, depth and breadth in interpreting the photograph, and effectively avoids the kind of limiting moral positioning that occurred for example in Susan Sontag’s famous critique of Diane Arbus’ ‘freaks’ series. Instead of reading photography as an act of violence on its unwitting subjects, Marsh suggests we “focus on the subject or the photograph, rather than the violent action”; thus photography could also be considered a fetishistic activity. Her readings of a range of photographs (by Cindy Sherman, Joel-Peter Witkin and Australians Linda Sproul, Anne Ferran, Deborah Pauwe, Pat Brassington and others) offer multiple positions and interpretations that do not privilege one perspective over another, yet Marsh also avoids an eternal relativism by commenting on the vicissitudes of certain photographers’ approaches. When looking at Australian Polixeni Papapetrou’s restaging of Lewis Carroll’s famous child portraits using her young daughter as subject (Olympia from the Lewis Carroll Series, 2002) Marsh notes the series’ liberating possibilities in providing both the photographer and her subject “opportunities for…childish play acting.” Yet, while Papapetrou is not unaware of the criticisms of Carroll’s work and debates about representing the child in photography, there remains a potentially problematic imbalance in power relations between mother and daughter in her work. Olympia “is still a child and her knowledge of the way in which her own image fits into the history of photography would be limited,” Marsh writes.

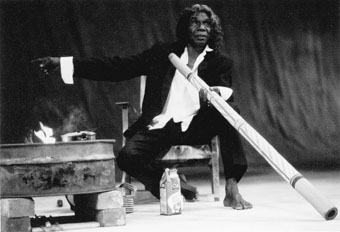

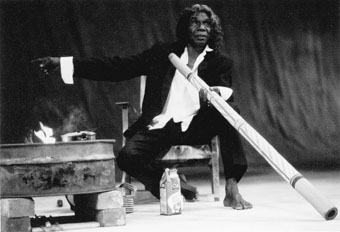

Perhaps of particular interest to RealTime readers, The Darkroom includes a substantial section on “Body art and Performative Photography” focusing on the role of masochism, narcissism and fetishism in performance work. In this section Marsh describes Mike Parr’s “obsessive and compulsive investigations of pain and endurance” and the role of autobiography and self therapy in his performances. Like Parr, performer Jill Orr “sustained a relationship with her self-image through photographic and video representations” and both artists mobilised the camera as a “critical or conceptual tool” within their performances, thus consolidating “the relationship between performative art and photography.”

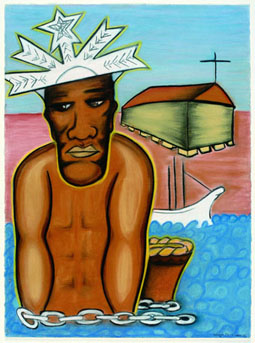

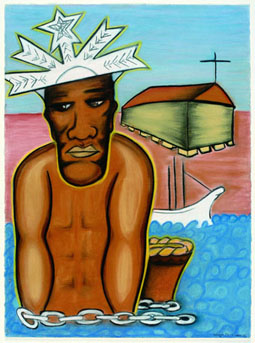

In the final section Marsh examines the photographs of postcolonial Australian artists which engage with “the text of the racial body.” She explores the crucial role of photography in identity politics, where the camera is used to document the fragmentation of identities and “embraced by artists as a critical weapon that could foreclose on authenticity and essentialist representations”; thus the camera is used “as part of an assault on humanism.” Included here are Tracey Moffatt, Leah King-Smith and Gordon Bennett whose Mirrorama (1993), a “psychoanalytic interpretation of aboriginality seen in the context of Australian history” stages a fractured subjectivity. For these artists “[t]he camera becomes a weapon in [the] scheme of misrecognition and dis-identity…[a] tool that can fracture and deconstruct subjecthood…creating a multi-dimensional view.”

By becoming a “performative machine” and an “instrument of destabilisation”, the camera, Marsh shows us, has operated as a “virus within modernism”, a tool for deconstructing those master narratives that privilege certain ways of seeing the world, while simultaneously negating others. Marsh’s work deftly shows how the camera can function as a “prosthesis for the operator”, as well as an instrument of fantasy, enabling the artist to extend the limits of his or her work in real space and in psychological terms. The Darkroom provides a rich history of how photography’s theatrical roots have remained evident in international and Australian work and how considering the complex functions of desire might broaden the ways we have previously read such work.

Anne Marsh is the author of Body and Self: Performance Art in Australia, 1969-1992.

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 32

© Mireille Juchau; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Mimi Kelly in Bianca Barling’s Slasher Slutz

photo Bianca Barling

Mimi Kelly in Bianca Barling’s Slasher Slutz

Destination: the budget motel. Transitory spaces filled with unfamiliar comforts, motels signify an arrival, a break in a journey. A motel offers temporary sanctuary; a place for respite, sex, sleep and shifting restlessness. With these ingredients of road movie consciousness in mind, 9 Adelaide artists invaded Motel 277 in Glenunga to stage No Vacancy, an exhibition of site-specific installation and performance art.

In Map Reference 201 D6, curator Honor Freeman delicately stitched beads around the perimeters of stains on bath towels, permanently and beautifully containing the area where each mark resides. Casually hung over a bathroom door and across the floor, the work sat harmoniously with Steven Carson’s I Know You’re In There. Brightly coloured buttons were methodically arranged, stacked and dispersed, growing like mould across the tiles, infesting the shower recess.

The wood veneer paneling and patterned textiles in Room 50 resonated with the luscious, tactile surface qualities of Sarah CrowEST’s 3 ‘objects.’ Ominously sitting in and around the bed, her comical blobs—oversized cakes or edible cushions—greeted the astonished visitor. In the next room, Tiffany Parbs’ carefully placed pools of transparent resin, disguised as water and urine, lay in the sink and on the floor as the trace of departed guests.

Bianca Barling approached American motel fiction with filmic humour and excess. Her Slasher Slutz was a combination of performance, installation and digital imagery, conveying the spectacle of messy death. Peering in through the window as if onto a stage, viewers saw 2 young female victims lying on a bloodied bed in their blood-soaked slips. Next door, in Room 49, Greg Fullerton’s Blue and White created a police crime scene, the unmade bed cordoned off, an abandoned cup of coffee on the kitchen bench, sugar scattered as if someone had left in a hurry. Part of Fullerton’s Bloodlines series, photographs of the participating artists, blood oozing theatrically from their faces, were placed along the breakfast bar in a line-up of likely suspects.

Transforming private, unseen acts, illicit relations and anonymous violent crime into a public acts, No Vacancy was a spectacle of intimacy, staged melodrama and lighthearted conspiracy. And perhaps a parody of those temporary habitations frequented by Adelaide Festival visitors.

No Vacancy, Bianca Barling, Steven Carson, Sarah CrowEST, Bridget Currie, Rachel McElwee, Honor Freeman, Greg Fullerton, Mimi Kelly, Tiffany Parbs, Motel 277, Glenunga, SA, Adelaide Fringe, Feb 22-24

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 35

© Sarah Quantrill; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

![Ben Howard, Jena Woodburn, [site-works], 2004](https://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/11/1107_currie_woodburn.jpg)

Ben Howard, Jena Woodburn, [site-works], 2004

At a time of year when Adelaide is filled with all things artistic shouting for attention, something very quiet is going on in the Hughes Plaza at Adelaide University. Jena Woodburn and Ben Howard’s video projection [site-works], occupies a smallish window of the Barr-Smith Library. The window forms the screen for the projector inside, the projection blending with the architectural environment. At first glance it could almost be an advertisement or poster.

We all know well the immersive sensation of being lost in a library, a world of information without time and physical space. The Barr-Smith is an august institution filled with level after level of narrow mission brown stacks. As a building it is hermetic in the extreme, much of it shut off from natural light and containing many levels of labyrinthine stairwells and corridors. It is the home of the book, the first virtual space.

In this building there is a window, a space for dreaming, for escaping. It can act as a porthole for physical and mental worlds to meet—the outside and the inside, the cerebral world of books and the world we physically negotiate.

window breaches the stronghold of the library’s body

usually it holds tight to its knowledge-store, only allowing out book-sized chunks

we’ve pierced it

inside pours out (is visible)

window is/was empty, transparent.

[site-works] is a skilful computer animation, travelling along trajectories of corridors and planes that can be read like walls, often dense with imagery. Leaves, rock strata, earth, shadows of trees in the wind, textures of the subjects of books and perhaps samplings of actual places. The Dewey Decimal System, a way of categorising all knowledge, of sorting the world into numbers, features as part of the animation, a self-contained system of numbers reducing information to code, not unlike that used in computers. The work contains both the internal logic of its making and the external logic of architecture. Sitting on the garden bed watching the work, the windows are not open but, strangely, you can smell the library.

[site-works], Jena Woodburn and Ben Howard, Barr-Smith Library, Adelaide University, Adelaide Fringe, Feb 25-March 13

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 35

© Bridget Currie; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Laurent Mulot, Stairway 2 Heaven

photo Laurent Mulot

Laurent Mulot, Stairway 2 Heaven

Three years ago, French artist Laurent Mulot took a train to Cook on the Nullarbor Plain. During a rest stop, he and the other passengers were drawn into the abandoned ‘ghost town’ experience maintained by Great Southern Railways and the town managers, Ivor and Janet Holberton. They explored deserted buildings, the abandoned shop and hospital, the golf course and a school where Mulot found some children’s drawings illustrating the habits of local fauna and, underneath, the sentence, “They come out at night” which he has used as the title for his multimedia installation exhibited as part of this year’s Adelaide Fringe.

Inspired by the strange initial experience, Mulot returned to Cook in 2003 for a 10 day visit. Using still photographs, video and sound, he documented the visitors who arrive by train and explore the small isolated town during the 90 minute stopover as well as the few remaining locals who receive them.

The central focus of the installation is a large-scale projection of the train’s visit accompanied by a soundtrack in which Mulot musically arranges the various comments on the town that he’s collected. While the name of the town is repeated rhythmically to echo the sound of the train, someone says that in Cook; “there’s no life, there’s no laughter.” Meanwhile, across 10 monitors to the side of the projection, we are shown Mulot’s images of Cook, revealing a certain beauty in their geometric composition. These are repeated in the form of photocopies strewn across the floor. Striking as some of these images are, this presentation does them no justice. The audience is left to step around them while being careful to avoid the dead trees suspended from the ceiling. These ‘found objects’ overstate the point and would probably have been best left in the ground.

The various components of the installation struggle to come together in a resolved manner and seem clumsy when viewed as a whole. The ‘ghost portraits’ (double-images of the tourists) that line the wall upon entry are interesting and the video is strangely engaging. In slow motion and other manipulations it captures the anticipation of the train’s arrival and the stillness once it’s departed, conveying Mulot’s theme in one frame, without distractions.

They Come Out At Night, Step One is a work-in-progress. Step Two will be exhibited at Fremantle Arts Centre, Steps Three and Four in Lyon and Paris. To watch the work unfold go to www.theycomeoutatnight.org.

Laurent Mulot, They Come Out at Night, Step One, Light Square Gallery, Adelaide, Adelaide Fringe, Feb 18-March 24, Fremantle Arts Centre, May 22-June 20

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 35

© Leanne Amodeo; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lola Greeno, Maireener, 2003

photo Peter Whyte

Lola Greeno, Maireener, 2003

Tasmanian Indigenous artist Lola Greeno is making her mark on the Australian art world, acclaimed for her tradition-based, finely crafted shell necklaces and bracelets, as well as the splendid fibre water containers and other objects that she makes from bull kelp. This large brown seaweed is found washed up on coastal Tasmania’s beaches at certain times of the year. The fibrous material has been collected on a seasonal basis by Indigenous Tasmanians for a very long time and is well suited to making objects of both utilitarian and artistic significance.

Born in 1946, Lola acknowledges her mother, the late Val MacSween, as teaching her the closely guarded secret methods and relevant cultural knowledge of the Tasmanian Indigenous people associated with making these gracile necklaces and bracelets. There are strict rules associated with this pre-contact Tasmanian artistic practice and Greeno is observant of these, while at the same time showing a willingness to innovate within the parameters permitted: “Families usually design the shell necklaces and one must closely follow these [designs]. In my case, I re-create my mother’s patterns. Today I am developing new designs to tell a story…for instance I have just finished a shell necklace that relates to the Cape Barren Goose, an original bird from my birth island. The water carriers have been a revival that I learned from a cultural workshop on the East Coast of Tasmania with a large group of women.”

Today, Lola Greeno actively mentors the younger generation to ensure the continuation of this demanding artistic practice, where preparation of materials and fastidious attention to detail is paramount. Greeno’s approach to her artistic practice is both visionary and generous. With characteristic altruism and humility, she sees herself as predominantly “…a Tasmanian Aboriginal woman interested in developing contemporary Aboriginal arts in Tasmania and providing opportunities for emerging artists to advance their skills and talent to assist them to another level or to be recognised nationally so they can become involved with Indigenous brothers and sisters across the land…I am also highly focussed on my cultural relaying of stories of importance to my daughter and grand children so that my heritage is recorded.”

Part and parcel of Lola Greeno’s approach is her emphasis on promoting greater awareness in the wider community about Indigenous intellectual and artistic copyright issues “…mainly to prevent people from making the shell necklaces who are not entitled to do so.”

From her beautiful island home, Lola Greeno creates luminous shell necklaces in much the same way her ancestors did. The very names of these shells, the raw materials of Greeno’s art, are immensely seductive and suggestive of an under-watery world of voluptuous otherness: stripey buttons, cats’ teeth, toothies, rice shells and maireeners—little bluish-green pearl-like shells that are of great cultural significance for Aboriginal Tasmanians.

In all, Greeno makes use of 11 types of shell in her work. She says, “…the labour is all in the preparation. The maireener shells take up to 8 weeks preparation prior to threading. The few makers return to the islands at least once a year to collect maireeners. This takes a good 2 to 4 weeks, although some people can only go for a few days. You may need to spend 2 to 3 hours just collecting one type of shell…”

Citing her career mentors as Gail Greenwood, Glenda King, Doreen Mellor, Brenda Croft and Julie Gough, Lola Greeno also acknowledges the inspiration of her mother, Judy Watson, Yvonne Koolmatrie, Brenda Croft, Julie Gough and Greg Leong.

Fellow Tasmanian Julie Gough, an admirer of Greeno’s work, writes: “…Lola’s shell necklaces are intricate responses to place. They reflect where, when and with whom shells are collected. They are often made in memory of her mother and of other co-inhabitants of her island homelands, such as the Cape Barren Goose. These relationships are reflected in the patterning of the strung shell lengths.”

Lola Greeno’s work constitutes a unique historically and aesthetically important form of cultural expression that is increasingly and deservedly achieving significance in the art market. Greeno makes stunning contemporary jewellery. At the same time she brings real cultural and historical depth to her work, contributing to an authentically Tasmanian cultural future.

–

Lola Greeno is showing with other contemporary Tasmanian artists in Design Island: Contemporary Design from Tasmania, Sydney Opera House, March 23-May 16

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 36

© Christine Nicholls; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

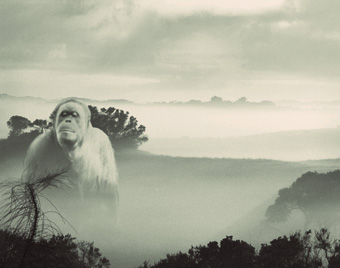

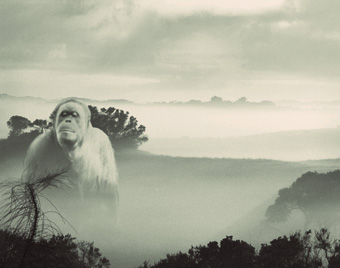

Lisa Roet, Pri-mates

Once upon a time Tony Bennett coined the term ‘exhibitionary complex’ to characterise the institutional shift of objects and bodies from the purview of the sovereign prince or lord into the public gaze. According to Bennett (following Foucault), the emergent 18th and 19th century museums and galleries performed the function of allowing people, “en masse, rather than individually, to know rather than be known; to be the subjects rather than the object of power; interiorising its gaze as a principle of self-surveillance, hence self-regulation.” One of the things we learn from our galleries, museums and zoos is nothing less than the order of things, ourselves included.

Don’t get depressed. Things can change. Take zoos: nowadays we construct simulated rain forests for the gorillas, a savanna for the African beasts, rocky pools for the turtles. We ask that our zoos in some way resemble the imaginary origins of our captive species (never mind most have never seen these far-away first homes). We tolerate enclosure as long as the frame is obscured, blended, masked by fake boulders and clumping bamboo. We continue to travel through gates and doors to see our wild things, but we can no longer ignore the subjectivity of our objects; hence, we tolerate the odd glimpse of the meerkat and suppress our frustration at animal-centred timetables (What? The tiger is sleeping again?).

But what about the gallery? Is it still a concrete cage for art and its objects?

Such questions arose as I traversed the exemplary space of the Lawrence Wilson Gallery in search of Lisa Roet’s exhibition Pri-mates, fantasising, like a latter-day Jane Goodall or Dianne Fossey, an encounter. Is there anything more tremulous, poignant, more poetic and dramatic, more beloved of Hollywood anthropology? It appears that our imagination—damp domesticated cliché that it is—still requires pockets of virgin forest and impenetrable wilderness, where we can meet the unseen and the unknown. The essence of ‘the encounter’ is that it be unexpected and in many ways unrepeatable. Though increasingly rare (I hesitate to say endangered) art can be such an encounter, as when, at a young age I saw the Bridget Riley exhibition at the Art Gallery of Western Australia: you mean, that’s what art looks like?

When it comes to encounters with the Other, we try to be alert to the fluidity of boundaries, the violent history of frontiers, and we prefer to use words like dialogue and exchange. And if we are not yet vegetarian, we are definitely thinking about it.

At the doors of Lawrence Wilson I am greeted by a video monitor showing an image of a human hand reaching through a cage bar towards an ape’s hand (or is it a monkey?). The reference is obvious. I am annoyed. I want an encounter, not an art-historical moment; I want a disturbance at the edge of the frame, a fracas, a disordering of subject and object, not an easy key to reading the work.

I pick up a sheet at the desk and read; “Pri-mates deals with investigations into the genetic similarities that exist between humans and primates, issues of language and communication and the point at which humankind is both alienated from and joined to the animal kingdom.”

Roet is fascinated by primates. Fascination is dialogic; to ‘fascinate’ is to ‘cast a spell over by a look.’ Her process is exemplary; residencies in zoos, visits to Borneo, long periods of study, interaction and engagement.

I linger at the works on paper—the feet and hands of chimpanzees. There is an essay here: on monkeys, mimicry, finger-puppets mark-making, creativity, but I am not equipped to write it. Perhaps Roet’s attraction to charcoal lies in the fantasy of recuperating primal creative drives (the child learning to grasp and strike the paper, the history of mark-making in art.) The huge drawings of fingers/toes are at once grotesque and beautiful. They conjure the whole history of things; the bleak scientific study of the fragmented ‘primitive body’, the anthropological and scientific scalpel cutting and bottling and labelling, the gaze of the student studying classical form (the hand of David). I move on. The bronze casts of chimpanzee’s heads recall photographic studies of babies attempting verbal communication. These works fascinate me. They are profoundly ambivalent; at once a study of a nameless other whose individual subjectivity has been subsumed in the name of genus and species, and an indictment of the anthropocentric limits of post-human portraiture.

Will there ever, I wonder, be an ape in the Archibald?

In Kate McMillan’s Disaster Narratives there is no fantasy of mutual recognition. Vision is not privileged in this exhibition, because on one level there is nothing to see. Superficially epic and classical in its aesthetic, Disaster Narratives draws attention to the ways we have encountered the art frame, and the potential emptiness of that encounter if the surface image or content is the organising or dominating principle. The huge central photographic image conjures a particular painting (Dejeuner sur l’herbe), but it also references the enormous history paintings found in some museums. The shell wedged high up in the wall exemplifies the exotica illuminated in a table case in a natural history exhibit. Yet the huge photographic image is also wallpaper—a billboard, and the single shell excised from taxonomic security is surely a private mnemonic, a reminder that outside of the cage, the images roam free. Hence the small static video image is both avant-garde and banal; on the one hand a refusal to reward the viewer with a ‘feed’, on the other an invocation of the endless tedium of domestic television. The ominous interiority of the large video projections of tunnels belongs just as well to a contemporary art space as to a late-night offering of Hollywood gothic-horror.

So what is the real story here? Who would know? A local viewer might confirm that the distant island in the video is Rottnest, formerly a prison for Aborigines, now a holiday destination. A well-travelled member of the audience might recognize the photographic wallpaper as Rubble Hill, a park built upon the destruction of Berlin. Someone else might know that Mao secretly built tunnels beneath Beijing, just in case of an emergency. In its very inability to narrate, this work enacts ‘the disaster’, which in Blanchot’s writings is that which is outside of the human, that which by being outside cannot be represented.

Meaning here lies beneath the surface, but it cannot be exhumed. Postmodernism eschews depth, yet this work is not about mere juxtaposition. It is not playing with us. The tone is serious. Mournful. Disaster Narratives reads like a very private, very formal essay on grief and mourning written through the formal hieroglyphics of art history. A disaster takes the subject to the edge of experience and abandons them there. Rather than being wilfully obscure, ironic, or “leaflet-dependent”, as one reviewer put it, I think of this work as leading the animal right to the door of the cage and opening it. Where, upon looking out, the terrified animal realises it is incapable of crossing the threshold.

Perth International Arts Festival: Lisa Roet, Pri-mates, Lawrence Wilson Gallery, University of Western Australia, Feb 13-April 20; Kate McMillan, Disaster Narratives, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, Feb 12-March 21

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 37

© Josephine Wilson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ben Murrell, Untitled (Wall Relief) V6.06, 2003

Fresh Cut is the Institute of Modern Art’s (IMA) annual exhibition of South-East Queensland’s recent art school graduates. Rather than selecting works according to a ‘best of’ criteria, Fresh Cut is a curated exhibition. This presents a challenge, since the art school is an environment where art making is compulsory and diversity accentuated. Attempting to find and articulate any prevailing theme for an exhibition under such conditions is fraught with problems, and the quality of work in any graduating year can never be assured. Too often over the last 8 years, Fresh Cut curators have presented us with a group of highly disparate works strung together by a tenuous rationale.

This year’s exhibition, curated by Chris Handran, was not entirely exempt from these problems though it did offer a slightly different curatorial approach. Rather than searching for a grand link between all 12 artists, Handran selected works which provoked a personal response. The result was a diverse collection featuring video, ceramics, interactive technologies, paintings and installation.

In his catalogue essay Handran noted, “No single theme or style characterises these works, though a number of affinities have come to light.” Wonderlands, private rooms, untold tales and natural selection are the terms through which Handran spoke of such affinities. The dividing of the exhibition into separate rooms under each term created a focus on linking clusters of works rather than a singular overarching rationale.

In gallery 1 visitors were welcomed by an infestation of curious creatures in David Spooner’s Mantle. Reminiscent of a domestic interior, yet given over to fabric fancies and plastic excess, Spooner’s work was appropriately lit by warm artificial and natural light. Accompanying this work was Kate Dickson’s Wallflower series, a suite of large-scale documentary photographs of posters which Dickson had installed across Brisbane’s cityscape. The posters took the form of a female figure, depicted in a cartoon style, usually close to life size and wearing colourful, fashionable clothing.

In gallery 2, the lighting was more subdued, and this darkening trend continued in galleries 3 and 4. Catherine Chui’s standout work, Betweeness, is composed of walking sticks recast from various media including noodles, newspaper, maps, dictionaries, coins, beer caps and koala fur. Hung like ladders and bridges across one corner and consuming almost a quarter of the room, the soft shadows of walking sticks cast against the walls was quietly arresting. Chui’s work lends itself to reflective moments, as it references the artist’s personal relationship with her walking stick, which both frees her from immobility and signifies her disability. The media Chui selects also references her journey from Hong Kong to Australia and her continual crossing between cultures.

Gallery 3 is the largest and is often an awkward space. Handran overcame any difficulties by installing works using very little light. Except for spots on oil paintings by Sonya G Peters, the only light in this gallery was emitted by the works themselves. Ben Murrell’s luminous architectural sculptures were beautifully placed, their fluorescent light enveloping the viewer. Adjacent to these shining installations was the glow of Alice Lang’s video projection and fabric installation. Avoiding a conventional square frame, Lang projected her video at an acute angle to the wall so that the frame became a morphed elongated quadrilateral. This suited the monster-like imagery from sessions recorded in cheap hotel rooms, in which Lang moves in and out of frame wrapped in satin sewed into bulbous and irregular shapes. Beyond Lang’s projection, 3 monitors sat on low pedestals replaying surveillance camera footage of Katherine Taube’s opening night performance, depicting her dressing and undressing in an interior lit box.

The increasingly dark journey continued in gallery 4, with a display of Julia Dowe’s slowly evolving video work and Svenja Kratz’s installation using interactive technologies.

This year’s Fresh Cut did not completely do away with the curatorial challenge but rather pared it back to the achievable and consumable. The exhibition is driven by the desire to provide positive outcomes for local emerging artists, but as Timothy Morrell stated at the end of his 1999 catalogue, Fresh Cut is also “a snapshot of a slightly shaking moment that makes focusing difficult. What matters is what happens next.”

Fresh Cut, curated by Chris Handran, artists Megan Bennett, Catherine Chui, Kate Dickson, Julia Dowe, Joshua Feros, Krystal Ingle, Svenja Kratz, Alice Lang, Ben Murrell, Sonya G Peters, David Spooner, Katherine Taube, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, Feb 6-March 13

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 38

© Sally Brand; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

<img src="http://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/10/1094_marshall_arabian.jpg" alt="Rob Meldrum, David Michel, Odette Joannidis,

Josephine Keen, Arabian Night”>

Rob Meldrum, David Michel, Odette Joannidis,

Josephine Keen, Arabian Night

photo Natalie Cursio

Rob Meldrum, David Michel, Odette Joannidis,

Josephine Keen, Arabian Night

Like much new German writing, Roland Schimmelpfennig’s Arabian Night resembles a prose poem or instruction text more than a conventional playscript. Actions are related to the audience by characters who perform them, as are settings and scenographic details. This serves Schimmelpfennig and director Chris Bendall well in creating a dreamlike atmosphere as the characters go about their lives in distracted fashion, imbuing everything with the sense that this might be a seductive, poetic illusion.

This also presents Bendall with the challenge of animating what is essentially a series of inter-cutting monologues. Director and performers skirt such performative tautologies as having the actor begin to run while saying: “I began to run.” Performance is rather gently embodied through minimal movement, easy posture and well supported voice.

The relationship between design, vocal work, Kelly Ryall’s lovely soundscape and the performance is slight, but on fortyfivedownstairs’ intimate stage, this matters little. Bendall is most adept at manipulating space and rhythm. The movement is shaped according to 2 main patterns. The first is a whorl about the iron post that permanently occupies the centre in this venue, becoming both a resting place and a pivot about which the increasingly disorientated characters spin. The second is a series of left/right corridors parallel to the seating, which turn the characters’ musings and personal journeys into something akin to slats glancing off each other on a venetian blind.

Although exquisite to experience, the dominant motifs of Schimmelpfennig’s script are not especially sophisticated or novel. The tale is set, for example, within a block of flats, constructed as a village unto itself or a microcosmic city, with its inhabitants coming close to each other but never really touching. As in the films of Altman and Tarantino (as well as much contemporary fiction), the play draws a web of connections between disparate figures, with the overlap of their lives producing an inter-woven narrative. This becomes the poetic motif in Schimmelpfennig’s work, as the surreal link between these characters is eventually revealed to be their having fallen into the dreams of the central protagonist, Francizka (Josephine Keen). She is cursed to forget her life nightly as she falls into slumber and to bring misfortune to all who kiss her.

Schimmelpfennig also employs the motif of the long, hot night as a catalyst for change and unusual behaviour, an idea which recurs in many plays, from Cat on a Hot Tin Roof to the 2002 fortyfivedownstairs production Sailing on a Sea of Tears (also set in a European apartment block). Schimmelpfennig skilfully uses this familiar concept to introduce a metaphoric interplay between desert and river dreamscapes. The water supply has stopped on Francizka’s floor, where the building attendant and others alternately experience dry, sandy winds or the frightening yet euphoric sensation of water coursing through the walls.

Arabian Night is a highly evocative production which, despite initial appearances, relies upon its performative realisation to render this beautiful if somewhat derivative text as something more distinctive than a mere theatrical sketch. In this sense, Theatre@Risk’s staging represents a triumph for Bendall and the actors, particularly Josephine Keen as Francizka and stalwart Robert Meldrum as the attendant.

Theatre@Risk, Arabian Night, writer Roland Schimmelpfennig, translation David Tushingham, director Chris Bendall, performers Josephine Keen, Robert Meldrum, David Michel, Odette Joannidis, Joshua Hewitt, sound Kelly Ryall, lighting Marco Respondeck, design Danielle Harrison; fortyfivedownstairs, Melbourne, Feb 10-22

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 39

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

<img src="http://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/10/1095_marshall.jpg" alt="Fiona Macleod, Adrian Nunes, Scott Gooding,

Trudy Radburn, Sensitive to Noise “>

Fiona Macleod, Adrian Nunes, Scott Gooding,

Trudy Radburn, Sensitive to Noise

photo Brad Hicks

Fiona Macleod, Adrian Nunes, Scott Gooding,

Trudy Radburn, Sensitive to Noise

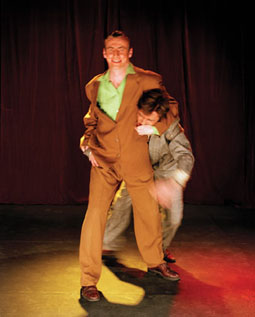

What are the emotional and social effects of naming? What is closed off and what is revealed or liberated? The latest project from Alison Halit and Ross Mueller is an attempt to coax out of the darkness of depression and introversion a representation of post-natal depression (PND). Speaking that which resists being spoken is central to both the creation of Sensitive to Noise and its performance. Within scenarios collaboratively devised by choreographer Halit and playwright Mueller, the characters struggle to speak, communicate and find peace. The very structure of the work emphasises the power of naming, with the characters’ confusion being (partially?) resolved by a penultimate scene in which a clinical diagnosis of PND is literally spoken on stage.

The use of the term PND brought legitimacy, validation and relief to women (and men) previously ignored as simply “down” or “oversensitive”, making sense of confusing behaviours and mood swings. One should not forget the negative effects of naming however. The kaleidoscopic vignettes and monologues of Sensitive to Noise superbly depict a spiral into intra-familial dysfunction. The partner becomes an enemy or irritant whom one nevertheless depends upon and the house a claustrophobic jumble of domestic detritus (beautifully rendered by designer Kathryn Sproul through literal and symbolic objects). The relationship between the couple becomes a theatre in which the sins of their parents are replayed as they neurotically reflect the discontent of their own childhoods. But is this PND? Or more significantly, if this typically occurs with PND, does it mean that every domestic drama involving these elements is also a representation of PND? And if PND is such a protean, wide-ranging collection of symptoms, what, precisely, is achieved by naming and depicting it on stage?

In a sense, one of the most compelling yet ambiguous aspects of this production is the way it replays the very contradictions it is designed to make sense of. The doubling of text with movement, of physical action reinforcing and adding an unbearable texture to mental disassociation, renders the show itself as an extended stutter. Scenes heave one to another, as an armchair wheels about to catch characters fleeing one scenario, before vomiting them up into another equally disorientating situation. As in the symptomatology of PND, the show repeatedly asks: “How did we get here?”

Perhaps the most ambivalent element of the production is the unresolved gendering of the work. It is no accident that the most potent symbol is the increasingly mute dancer, Trudy Radburn, looking out wide-eyed at an environment that seems unfamiliar, dreamlike and daunting. Despite the introduction of men’s stories, the asymmetry between the depth of dance experience embodied by the unspeaking Radburn and the men’s greater reliance upon spoken performance replays the model of PND as women’s business (which it surely is) and a disorder in which an unreasoning female body replaces the reasoning mind. The shadow of hysteria and the awkward histories of medicine, gender and science fall heavily across the performance.

Sensitive to Noise is most impressive for its final paradoxical sleight of hand. This is the closing dance sequence involving Radburn and the tragically adorable Adrian Nunes, in which PND is reinscribed as that which forever eludes full representation in all its chameleon-like social manifestations.

Sensitive to Noise, devisors/directors Alison Halit, Ross Mueller, performers Fiona Macleod, Scott Gooding, Trudy Radburn, Adrian Nunes, design Kathryn Sproul, sound David Franzke, lighting Jen Hector, North Melbourne Town Hall, Feb 18-29, Geelong Performing Arts Centre, March 6

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 39

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Frumpus, Crazed

photo Michael Meyers

Frumpus, Crazed

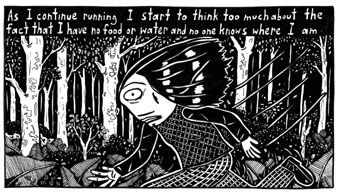

Entering a Frumpus performance is like pushing through to some much-needed Buffy dimension where the demons are actually you, in disguise, in some nightmarish cinematic loop, but with matching red tracksuits and sinister grins. Crazed is a new work by this dedicated ensemble of shape-shifters and Adelaide seems like the perfect place to unleash it, especially as a late night horror feature in the biennial Fringe Festival. In fact, their venue choice was only a matter of metres from dark, historical Adelaide-terror central: the Torrens River. Bodies dragged, bodies dumped.

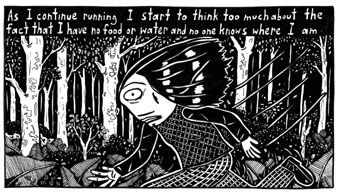

Crazed is a manic composition, variations on a theme of slasher/horror genre (filmic references aplenty, some recognised, others not, me being the squeamish type who always looks away when the guts are spilled, the head cut from the body, the limbs severed…). Crazed takes me anywhere from the Chainsaw Massacre-type hopeless chase in the woods (there’s no escape! you’ll never get away this time!); to the Blair-Witchefied surrounds of the sleeping-bag-cum-tent with a camera shoved in your face, tears streaming; to the Hanging Rock zombie drawn to the abyss of pan-piped hell; to the begging for water, to drink (not even a sip!); to the petite rituals of mad fireside needlework in some Victorian gothic, storm-ravished mansion, disturbed by the incessant ringing of a telephone (dare not answer for fear of the terrifying voice of a Telstra answering service); to the abandoned country house with only the killer for company; to Cronenbergesque mutations, visceral, oozing. Sigourney Weaver would fall so deeply in love with the alien glove puppets whose seedy obsession with porn, sauna orgies, car hoonin’ and chain smokin’ would endear anyone’s tender (soon to be torn open) stomachs for a spot of sci-fi bio-tech co-habitation. Not even your washing basket is safe from bad planet creature invasion.

Framed in a polystyrene horror house with filmic windows, flames mediated via projected image, Frumpus bodies dressed in Super-8 screams and psychotic struggles for help, help, the performance space is a kind of eternal movie set silhouette, a malleable site in which to enact the inevitable death scenes, the sort that seem to just fill with blood until the next big baddie moves in for the kill. These demons have taken the form of some other Frumpus frightener: scary nurse-vamps with cigarette holes for mouths. Red worms from the planet Camp. An action flick duo who punch-glove martial art their way to the knife point of death. Did I mention Buffy?

Enter a Twin Peaks procession of bloodied feet wigged-out morphed heads who will take the applause anyhow. Cos they’ve walked so far. In heels, no less. Probably across some desolate bridges. Their deaths and lynchings were staged over at least 20-odd takes. It’s about getting that right expression. That perfect look of fear.

Crazed is an audio-bite cut-up live show of blood-curdling screams, breathless voices pleading to the insane one to please stop knocking, even though we all know what’s gonna happen next…but Frumpus has gotta run, over the moors, into the dark night.

Fire, walk with Frumpus.

Frumpus, Crazed, director Cheryle Moore, performers/devisors Janine Garrier, Lauri Kilfoyle, Lenny Ann Low, Cheryle Moore, Julie Vulcan; video & video Samuel James, sound, Gail Priest & Cheryle Moore; presented by Vitalsatistix Theatre Company, Adelaide University, Adelaide Fringe, Feb 21-March 7

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 40

© Jason Sweeney; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

If visibility and inclusion are a measure of success, Strut’s dance program Two Way—featuring new works from Jo Pollitt and Sue Peacock—in the Perth International Arts Festival was an occasion for celebration. Since its inception, Strut Inc. has provided a site for dialogue and development of contemporary dance.

Room is choreographed and performed by Jo Pollitt, its 3 sections directed by Paige Gordon, Felicity Bott and Bill Handley in turn, signalling that dialogue and collaboration were important to the works, if leaving the audience mystified as to the role of the director in relation to the choreography. In conceptualising her works around the idea of 3 rooms—’inside’, ‘outside’ and ‘waiting’— Pollitt underlined her intention to explore relationships of exclusion, inclusion, and adjacency. However, the works failed to resonate with each other, either stylistically or conceptually.

If the opening image of an elongated and elevated Pollit set upon some kind of hidden plinth, adorned in a swathe of white was intended to strike the audience, it missed its target. As a study of minimalist articulation—of arms, back, neck, head—Room 1-Inside had difficulty projecting its subtleties within the space of the Playhouse. More troubling was its failure to acknowledge its kinship with living statues that function well on the street, sustaining the glance, the stare, the gathering of a small crowd that assembles briefly only to break up—but not the seated paying audience. Drawing upon a vocabulary of slapstick and mime, Room 3-Outside amused without truly engaging. What was missing was the very idea of being outside.

Room 2-Waiting, directed by Bill Handley, was the most successful section. Largely autobiographical, its tone was tragicomic, the narrative qualities enhanced by Pollitt’s spoken text. Here was a piece that acknowledged the breadth of the festival audience, that was generous and open in its revelations, and which touched me in its delicate handling of personal tragedy. Here Pollitt as performer was able to tell us of death in the family, of car accidents, of the loss of opportunity, and in the very telling of that story through the body enact an overcoming.

Sue Peacock is an accomplished choreographer and performer, most recently seen in the finesse and precision of her marvellous solo Swallow in PICA’s Dancers Are Space Eaters. Give up the Ghost was a shambolic affair. It begged for dramaturgical input, particularly since this was a piece for 7 performers negotiating shifting relationships across at least an hour of dance time. All of the dancers are fabulous performers, yet they were terribly let down by the basic concept and its failure to develop. Is there no other subject for an ensemble of men and women than ‘relationships’? Not that there is anything wrong with relationships but the problem is the focus on the cliché of ‘relationships’ at the expense of a particular relationship.

An insurmountable problem for me was the staging of the piece within a squat/inner city/loft adrift with bare mattresses and graffiti—all very New York/Lower East Side circa 1989, except that in real life slumming is not a style but an absence of choice. There was none of desperation, the poverty, the tragedy of real life. Yes, I know it was dance, that it was a representation, and where is my sense of humour?

Well I didn’t find it funny, but pompous and self-important, and at times plain tedious. Couples coupled, fought, made up, made love, fought again, found themselves, lost themselves and occasionally were allowed to demonstrate the inventive exuberance that audiences love—only to have the music cut off their legs. There were plenty of moments that were almost marvellous—and then the music changed and the dance stopped. Peacock drew upon a marvellous set of extant music, and the projections were great, but the unrelenting and unmotivated disc-changing came to dominate and determine the movement, adding to the sense that the work was conceived on the run. A sense of breathlessness and desperation dominated Ghost, evident in the inability of the choreography to settle upon a phrase and explore it, in the unmotivated shifts in mood and music, in the lack of thought given to audience response. (And why was the text in French—is there something inherently urbane and ghetto-chic about French?)

No doubt there is another story here, of lack of resources and lack of time but not of lack of talent. Perth choreographers have demonstrated their talent over and over. But a full program in a festival requires more than potential. Choreographers must rise to the event, or I fear that the event will not again arise for them.

Two Way: Room, concept, choreography, performer Jo Pollitt; Give up the Ghost, choreography, direction Sue Peacock; Strut Dance, UWA Perth International Arts Festival 2004, Playhouse Theatre, Feb 11-28

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 40

© Josephine Wilson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Kristine Nilsen Oma, Dance Card

photo Masayuki Yamane

Kristine Nilsen Oma, Dance Card

The Dance Card mixed bill premiered in 2003, featuring musicians and lighting designers improvising with a changing selection of dancers over a 3 week period. Solos from the first 2 weeks returned for the final week to be re-scored and re-lit. The diversity of styles and relationships sketched through music, illumination and physique meant that one’s reaction to a particular designer or dancer was beside the point: the program was about audiences and artists evaluating each formulation of elements. This year, however, Monique Aucher lit all 3 weeks while Tamil Rogeon was composer for both weeks 1 and 2. This made Dance Card 2004 less invigorating, but it still contained many moments of quicksilver magic.

Aucher’s design consisted of a selection of warm colours: bare, yellowing globes and pinkish-red lights contrasted with blues and greens. These washes were complemented by central highlights and bright white axial corridors. The mixing was beautiful, echoing John Ford’s highly diffuse, colour-based design for Dance Card 2003. However, Aucher’s use of these options was less assured, employing flashes and chases that were not only distracting but often highlighted areas where nothing was happening. I had similar quibbles with Rogeon’s coordination of virtuosic violin highlights, lingering extended playing, dance music-like chordal beats and glitchie or static-like atmospheres. Although seductively insubstantial, the wafting music was often hard to hold onto, or too musically didactic to support the improvisation. Nevertheless, Rogeon’s use of a deliberately circumscribed musical palette established a pleasing sonic cohesion to each night, even if the nature of the solos didn’t altogether merit such consistency.

David Franzke re-scored the solos in week 3 and mastered best the challenges of the program. While some of his sci-fi, low-key soundscapes derived from materials similar to Rogeon’s, Franzke skilfully suggested particular readings. Rogeon’s scoring relied primarily on a paralleling or guiding of tempo, rhythm and texture in performance, carrying elements across the solos. Franzke’s contributions functioned according to an essentially dramaturgical logic, while enhancing the interpretative dissonance and uniqueness of each dance piece by allowing only hints or slight layers to be reworked sequence to sequence.

This difference was exemplified in Kristine Nilsen Oma’s performance. Unlike the other dancers, Nilsen Oma’s movement was predetermined right down to the text she recited and the point at which this was offered to the audience. The movement was essentially Graham-based, consisting of forceful, jerky variations on melodramatic Expressionist tropes, such as an emotional pushing through the chest with the back and head arching behind, or a weaving of arms into and out of the body to represent emotional pain and release. In week 2, Rogeon followed tradition by providing her with emotionally laden strings, enhancing the performance’s neo-Romantic ambience and power. In the last week however, Franzke replaced this with a series of musical cut-ups, including recorded text, music and radio fragments coming in over each other in an electric pastiche. Rather than the cliched model of the angst-ridden artist offering us her suffering, Franzke’s provocative style recontextualised Nilsen Oma’s body as one racked by the infection of multiple languages, sound bytes and cultural references. Instead of the classic, modernist dancing body, Franzke repositioned Nilsen Oma within a postmodernist framework. Even so, he was sensitive enough to drop his contribution to nothing to allow Nilsen Oma’s voice to come out for the scripted finale. Franzke’s work thus combined modesty with highly active musical interactions.

Those dancers working from formal or emotional concerns had largely devised in advance their basic poses and choreographic palette. It was the sequencing of these elements and their nuanced execution which was developed live in performance. It was therefore amongst the jesters that the principles of improvisation were most fully embraced; every element was generated in the moment with typically uneven results. Dianne Reid and Shaun McLeod were superb, employing a soft, elegant take on improvised comedic text and performative pathos. It was their seesawing between unaffected, dancerly turns of beautiful fluidity and more pedestrian movements and banal scenarios which made their nightly performances so affecting.

On the other hand, Michaela Pegum and Siobhan Murphy presented essentially formalistic, semi-choreographed studies given a seductive lilt through touches of emotional execution. With a highly mannered use of self-caresses and a kilt, Nick Sommerville danced a great solo echoing some of Phillip Adams’ concerns in balancing moments of muscularity and energetic bounce with an interesting play of gender.

Pegum’s was the most technical and austere solo, sharply danced in a plain, white costume and energised through particularly measured, often geometric shifts of movement and exchanges of momentum. Her right forearm carved out lines on the floor as her body crouched above, before the obtuse angle of the left leg was echoed and its shape erased by lifting the entire body up and out in a diagonal line, via a transition which was led and articulated through the point of the elbow. Responding to the rising beat of Rogeon’s music or Franzke’s open, charged static, Pegum increased the extent of these movements, while allowing the transitions between them and the falls of the body to linger longer and longer, imparting a palpable sense of sexuality and ecstasy into her open-mouthed performance.

In contrast, Murphy danced from a more impressive, physically subtle space, beginning with irregular crossings of legs and feet, before these absent-minded jumps in concentration and velocity progressed into hands and arms, finally causing the body itself to whirl or half-fold irregularly upon itself. Between these frequent yet essentially discontinuous spikes of activity, the dancer’s eyes flickered and mouth trembled, as hands moved across, in, and above each other, in small, retreating jabs, as though trying to feel out a gesture or a cognitive phrase which would make sense of these impulses. This constant searching for and locating places in movement and expression resembled a fractal version of the thinking body dramatised within the more precise choreography of Rosalind Crisp.

Alongside these promising explorations from relative newcomers sat Deanne Butterworth’s wonderful, effortlessly massive performance. Frequently featured in projects from Dance Works and Shelley Lasica, Butterworth is a master of seductive lyricism. For all the elegant beauty of the choreographic palette she has enjoyed, there is nevertheless a danger that she might simply echo that highly attractive, sparse lyricism in her own work. By dressing herself in what appeared to be a gorilla suit without a head, Butterworth undercut expectations. Floppy ripples of black fur drew attention to the dance’s focus on unforced manipulations of weight through the hips. The fur also highlighted the lethargic beauty of Butterworth’s softly moving form, as she gently released into the ground and then lightly returned to stand using only a few well-chosen, yet unassuming movements. It was the gentle undulation of hairy cloth and inertia that gave this work its ambiguous drama.

Dance Card may have already run its course as an innovative way of dramatising the exchanges generated in theatrically-framed dance, but the plethora of fantastic relationships contained in its 2 year run has been well worthwhile.

Dance Card 2004, curator Helen Herbertson, various performers and sound artists, Dancehouse, Feb 11-28

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 42

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

embrace

photo Victoria Hunt

embrace

A new work by Tess de Quincey is always a red letter event in the performance year and already there’s a buzz about De Quincey Co’s …an immodest green, the first in a series entitled Embrace inspired by the company’s 3-month residency in India last year to be presented at Performance Space in May.

Tess de Quincey has a longstanding connection with the sub-continent dating back to her meeting in the 80s with dance ethnologist Ranjita Karleka and, later, documentary filmmaker JoJo Karlekar. Ranjita introduced her to The Natyashastra, a fundamental text in Indian artistic tradition. Meeting up with these two in Kolkata last year, De Quincey was interested to explore further the text’s parallels with the Body Weather discipline which informs her company’s work. At the same time she began to conceive an intercultural performance exchange which would bring together Indian and Australian artists in a series of workshops and performances culminating in 2005/06 in an all-night installation event reminiscent of some of the ancient Kathakali performances that mark the passage of time from dusk to dawn.

When asked by Erin Brannigan what we might expect of Embrace in Sydney, De Quincey replied from Kolkata where she was about to embark on a 10-day workshop with Indian participants at the School of Music, “Well, given that … every day is an intense onslaught of colour and texture and smell amidst a wild anarchic bustle and passionate thriving humour in a deeply black, polluted city, we’re running constantly on the spot just to keep up. It’s the magnificent discordance and defiant skirmishing which imbue every level of life here that are soliciting and formatting our bodies and our thoughts.” (Read the full interview in Ausdance’s Dance NSW, Jan-Feb 2004)

–

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 42

© RealTime; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Christine Johnson, Lisa O’Neill, Pianissimo

The irrepressibly energetic and adroit programmer Virginia Hyam is running her 5th 6-monthly season for The Studio at the Sydney Opera House. Hyam has carved out a space for idiosyncratic, often cutting edge entertainments from around Australia and created new audiences to match them. As just one dimension of the Sydney Opera House’s expanded vision of the art it presents and the audiences it needs to develop, The Studio is a key player.

The 24 shows in the program to July are indicative of Hyam’s eclectic taste as well as that of her largely young audiences. Not surprisingly then music in one form or another is to be found throughout a program which includes Pianissimo from the wonderfully eccentric and innovative talents of Brisbane artists Christine Johnson and Lisa O’Neill; hip hop comedy in Inna Thigh by dynamic rappers Sista She; virtuoso percussionist Ben Walsh in his one man, many drums show First Sound; the Ennio Morricone Experience’s instrumental extravaganza of spaghetti western music; Morgan Lewis in the see it-and-DIY hip hop theatre show, Crouching B-Boy Hidden Dragon (RT 54, p38); and there are dance works from leading choreographers Russell Dumas and Sue Healey. Other shows and events in the program—the recent Global Beats mini-music festival, the Message Sticks Indigenous arts celebration, a smattering of comics, The Song Company doing a not-to-be-missed reading of The Song of Songs, new media screenings, exhibits and performances in Scope (as part of the Sydney Film Festival) and, for something completely different in an already headspinning lineup, the popular Scratch Nights. The first of these is Embalmer! The Musical, the second the immersive and interactive Sprocket from Sydney’s new media outfit, Tesseract Research Laboratories. I asked Hyam if her approach to programming had changed over the last 3 years.

I think it’s coming from the same basis, the core being that there’s no particular formula as to what shape it should take. It’s not all theatre, not all dance, and has a completely eclectic feel. It’s responsive to what contemporary work is out there, around Australia and what is in the process of creation, so that we’re involved in the making of new performances. It’s about supporting emerging artists and established artists involved in small scale work and talking to both niche and broader public audiences. Balancing all of these is what I’m still trying to do with the program.

At your launch for the first program for 2004 there were very few of the usual arts suspects, and you said proudly, there’s probably quite a few hairdressers here.

What we’re really on about is trying to attract people to come to the theatre who otherwise wouldn’t. I know everyone talks about developing new audiences but I think The Studio program is an avenue where we can. Purposefully it’s been made accessible both price-wise and with a lot of the content. I think [the British show] Duckie was a good example, attracting a queer audience from across Sydney who might be clubbers who wouldn’t necessarily think of coming to live performance. I’m hoping that they’ll be intrigued to want to come back and see something else.

Is there is in fact a flow on effect?

Certainly over the last few years we’ve noticed there are crowds that regularly come back. When we do our data collection to send out the program, there are very large numbers of people who’ll come and see 3 and 4 shows across the year. It’s not a subscription series because we don’t want subscribers to then be dictating what the program will be. Every year I set out to cater for certain groups and their tastes. People pick up the program and see 2 or 3 things in a 6 month program of particular interest to them. Consequently we talk to a whole range of audiences.

You rarely program shows with long seasons.

The average season is 2 weeks or one, or one nighters. I’ve tried longer seasons but, to be quite honest, some of the work we bring in attracts only a certain number of people and if you spread it over 3 weeks, you’re only diluting the size of your audience. Often we’re introducing new artists into Sydney and I tend to reintroduce them back into The Studio once they’ve developed a name here. Christine Johnson from Brisbane is a good example. She’ll be coming back this year with Pianissimo, her show with Lisa O’Neill, The audience for Johnson’s Decent Spinster last year built up well over the 10 performances of a 2 week season. And we offer a broad range of choice. You’ll see the same sort of fields repeated across the program. It’s a bit like a festival. If you miss one thing you know there’ll be something else interesting coming up.

The program reflects the changing nature of the arts field in your hook up with Sydney Film Festival and various new media arts organisations.

The film festival came to us, seeing The Studio as a good venue to present their new media work because of the sort of audiences we have already been attracting. I saw it as a really positive relationship. The other element that came into it was the Ennio Morricone Experience doing spaghetti western film music. I asked the festival if they wanted to have them as an umbrella event. It’s a perfect partnership. Those sorts of relationships are crucial.

Your program, as ever, looks very entertaining, full of laughs, campery and satire. That’s not to say that it’s not serious fun, as in the work of hip hop artist Morgan Lewis.

I think I like politics presented that way. And you’re right, there’s a lot of that throughout the program and that’s the contrast I’m trying to find with other work that’s already happening around Sydney. I know people want to profile their work at the Opera House but not everything can be or is necessarily appropriate or indeed best shown here.

What’s the relationship with artists coming into your program?

Everything that goes into The Studio has to be supported. And that’s what I love about the program. I love building it and it’s always done in collaboration with independent artists who are all coming from the same place of being under-funded or unfunded and working out ways that we can make it work between the two of us. When I started there was a certain contract you’d have with the artists and now we have many versions of that contract. You’re thinking there can’t possibly be another kind of relationship and then it’s oh, I think I’ve just come up with another one! The core factor is that it’s a shared relationship. It’s very rare that The Studio is just paying out the money, putting the show on and going forward. More often, we’re all working together to ensure the success of shows. That’s what’s exciting about it.

You’re not in a position to commission new work all the time.

Exactly. There are not a lot of commissions in the first part of 2004. We’re developing some new work in the second part of the year. Certainly, it depends what’s on the table and what’s already out there and who’s coming to me. It’s fluid but every 6 months there’s money going towards development of something. And it’s often on a smaller scale. In the next 6 months we’re developing a relationship with the independent radio station, FBI, doing plays that will go live to air from The Studio. We can do small things which can have quite a vast effect on the people involved. I’m really interested in commissioning emerging artists and bringing them into the venue working within a different framework. The Dance Tracks program has been a great model for that and an opportunity for commissioning artists to do short works.

What about the future?

We’re looking at establishing a jazz festival working with Jazz Groove and SIMA [Sydney Improvised Music Association]. What’s going on in Sydney is constantly changing…our program has no fixed formula. It has to be fluid, it needs to remain current.

The Studio, Sydney Opera House, www.sydneyoperahouse.com/thestudio

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 41

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Boxed Set

My Darling Patricia, Dear Pat

photo Heirdrun Löhr

My Darling Patricia, Dear Pat

Hinting at residues of human cargo and mysterious ocean traffic, a converted shipping container worked as provocative metaphor and sculptural performance space for the diverse sequence of works that comprised Live Bait festival’s Boxed Set program (RT58, p36). At once an ominous capsule incinerating its freight, a house of feminist horrors, a monster’s home and a satirically-sweet motherly dwelling, the container became an expression of the theatrical imaginative, prompting explorations of the invisible cultural and political boxes that we covet, ignore, repress and escape.

First to emerge amidst the buzz of Bondi’s open amphitheatre are 5 destitute figures, landed from some other dreadful place in time or history. Their faces are stretched in torment, their bodies harrowed and gaunt. One tows a large, heavy tabernacle. One pulls a barrow heaped with crumpled suit jackets. One stalks ahead and purposefully—urgently—climbs a ladder and begins clanging it, and his bucketed-head, violently against a brick wall. This is Gravity Feed, and from the moment their presence is felt in the arena, frivolous evening becomes ritualised chaos, secure crowds become scattered, immaterial bodies.

The Gravity of the Situation works to generate unfamiliar zones, to desensitise the audience to the calm balminess of a summer’s night and surround them with harbingers of…death, nightmare, apocalypse, underworld? Propelled by the sonic thuds and gurglings of a world aching to split open, the performers band and discharge, carry fire, throw coats, grip to the edges of walls in shafts of light. People are pushed into corners or the centre of the courtyard, made to assume and surrender territories or dodge spinning cardboard flanks.

This movement plays out a kind of compulsive nihilism, a frustrated and repeated logic of anarchy clamouring to access a blip or glitch in the seamless running of things and push any moment to its inevitable point of rupture. And the thrill of this perforation is compounded by the fact that the audience not only witnesses, but completes the experiential exchange. It suddenly becomes part of something bigger than itself—a frightening yet scarily enticing modality that is part ritual, part performance, part yearning for something other than what we know and have.

Notions of feminine fear, gothic horror and female representation (depicted as its own type of horror story) are all given a comic bite in Frumpus’ Ripper 2004 (director Cheryle Moore, video Sam James). Transforming Gravity Feed’s smoking tabernacle into a house of horrors, Frumpus emerge ridiculously red-tracksuited with torchlights and begin running (and dropping) pac-man style in a pantomime of fear and dodgem’ bullets. In front of a projected sequence of blonde women (again) running (presumably excerpts from various slasher films), enter the Frumpus women newly dressed in the archetypal white nighties and blonde wigs requisite of any truly gruesome horror flick. They “want water” they tell us, “water to drink”, in a peculiar moment of mimicry and satire that mirrors their thirst-crazed ‘feminine’ counterparts on screen. And then they are running again, this time their nighties becoming those in the projection, whilst a miniature ‘evil’ Frumpus doll is bloodily birthed from a backpack serving as a prosthetic womb.

Frumpus are masters at clinching just the right edge between comic artistry and ridiculous silliness. Ripper 2004 explores connections between mythologies of fear (especially a ‘feminine’ fear) of unknown territory and of femininity replayed on the omnipotent boxes of popular visual culture. Hence, later in the piece they construct a curious juxtaposition of sleeping Red Riding Hoods set against a video of buxom naked women teaching Tai Chi. At times these textual collisions can be oblique or alternately too obvious, but the skit-like quality and general buffoonery Frumpus employs suggest that not only are they running from the horror of their own representation, they are running because they just do it so well.

Julie-Anne Long, Boxing Baby Jane

photo Heidrun Löhr

Julie-Anne Long, Boxing Baby Jane

Womanhood is given a different telling in Julie-Anne Long’s subtly satirical meditation on motherhood, Boxing Baby Jane. In collaboration with video artist Samuel James, Long constructs a “duet for live mother and projected child” in which the figure of saintly mother is placed against footage of a very sickly-sweet disembodied girl child. In a series of projected sequences, Long interacts with the ‘fictitious’ child through a combination of abstract and literal choreographies, building a progressive antagonism that stems as much from the implied mother/daughter relationship as from the compositional difference their live and filmic bodies erect.

James’ video montage merges realtime footage, still shots, film intertexts and animated sequences to form a suspended limbo of part-image, part-performance that creates a skewed multi-dimensionality, particularly in moments where mother and daughter ‘enter’ excerpts from 1960s psychological thrillers that recall haunted suburbia and sinister veneers of smiles and propriety. Yet it seems that these canonical films and James’ playful interventions are intended to work more suggestively than literally. As the house of their pas de deux erupts into flames, both mother and daughter remain caught in past ideals of role and gender, living the frustrations and complexities of an obsessive relationship that has its cinematic boxing incinerate around them.

The past is met again with the entry of the 3 Patricias. Poised at the edge of the theatre space, they move in slow motion: a glance aside, a wave into the distance. Their faces are stiff with genteel smiles. As they begin to work slowly repeated choreographies of dainty running, anxious searching and signals afar, their focus carries us into the historical mise-en-scène of Dear Pat and compels us to attempt to make sense of their world.

The oddity and charge of Dear Pat stems from its orchestration of disparate elements. Calculated, choreographed bodies skilfully enact and lightly satirise mannerisms and ladylike gestures, while the sound design oscillates between the suggestive evocation of historical place, operatic lament, and the repetition of a mysterious love letter. And finally the enormous and otherworldly many-teeted puppet that explodes from within the box proper.