Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

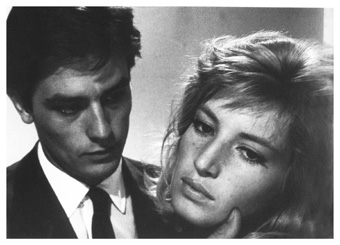

Kay Armstrong, Narrow House

photo Heidrun Löhr

Kay Armstrong, Narrow House

Experiencing Kay Armstrong’s The Narrow House is like getting into the head of a murderer by way of her body, her words and into the evolution of a psychosis, onto the planning and into the crime. It’s a claustrophobic trip as the will to act forms and the rehearsal of the murder forces choices. Naked seduction followed by a knifing? Or a cup of poisoned tea served with domestic grace in an apron? The fantasy is full-bodied, sexual, likely bloody; the fact is the female murderer’s favourite, the inversion of nurturing: poisoning.

Unlike John Romeril’s early work Mrs Thally F, a play about a real Australian poisoner, Kay Armstrong’s murderer is an invention but a nonetheless convincing one. This worryingly sensual, perversely poetic dance theatre work is about a consuming state of being. As the passion escalates we see the murderer across the theatre’s pitch dark spaces through various psychologically refractive perspectives. She’s a naked woman (self-)fondled in a kitchen window. She’s a close-up confidante of the audience. She serves tea at a table over which a mirror swings low so we watch her from above, doggedly rehearsing the increasingly mad moves of her murder. She appears in a distant corner of the ceiling like a spider alert in her web. She’s disembodied, projected onto a wall perpetually entering the crime scene-to-be.

But it’s in the naked and vulnerable but aggressive body that we see both the desire and the torment of the compulsion, an idiosyncratic and increasingly tormented dance to an unseen force that tugs at her, drags the woman off-centre. It’s a barely controlled agony heard too in Garry Bradbury’s rich, enveloping sound score. This body connects only with a few objects in this closed universe: a large, threatening kitchen knife, a bone china teacup that glows like the Grail and a statuette of the Virgin. The Narrow House is an absorbing and disturbing creation. Armstrong’s writing needs distilling and her acting more restraint, but after some tentative and difficult steps towards creating her own brand of dance theatre, she has now proven herself capable of a bracing totality of vision, not least in the self-choreographyof an aching dance of limbs, of a body dissociated as painfully as its psyche.

One Extra, The Narrow House, performed and choreographed by Kay Armstrong, dramaturg Nikki Heywood, composer Garry Bradbury, video Samuel James, lighting Simon Wise; Performance Space, March 10-21

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 48

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

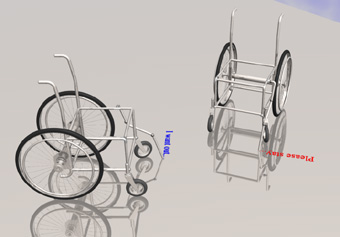

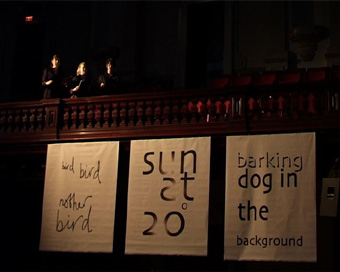

Velonaki, Rye, Scheding, Williams, Fish-Bird (work in progress)

With increasingly evil results to all of us, the separation is every day widening between the man of science and the artist…. [the artists] not only do not desire, they imperatively and scornfully refuse, either the force, or the information, which are beyond the scope of the flesh and the senses of humanity.

John Ruskin, 1883

Artists have been looking at what scientists of the day are up to since art critic and social commentator Ruskin’s time. Many have frowned at the notion of artists working with scientists, but artists have always worked with technology of some kind. And modern science, like contemporary art, produces knowledge through ideas. Concept and theory precede method, results are scrutinised critically, and occasionally outcomes are celebrated in public through the market place, exhibitions and forums.

Informal links between the disciplines have been cyclical in modern times. The Artists’ Placement Group (APG) in Britain, for instance, was instigated by artists in the 1960s to formalise processes for creating professional relationships between artists and those in science and commerce. It is only recently, with the broader recognition that advanced research programs are necessary, that initiatives like Synapse have begun to re-build these relationships here in Australia.

Synapse is a series of related assistance programs to encourage collaborative ventures between artists, scientists and technologists. As a structure at the junction between 2 neurons or nerve-cells, the synapse is an attractive metaphor for the program, representing the notion of connection. The Australia Council, starting with its commissioning of the Art and Technology report in the mid-80s, has been at the forefront of support for the establishment of bodies like the Australian Network for Art and Technology (ANAT) and more recently programs like Synapse. A joint initiative between the New Media Arts Board and ANAT, Synapse is a strategic alliance through collaborative research projects between key stakeholders, including the Australian Research Council (ARC), university research centres, the CSIRO and industry. Synapse is also a database, maintained by ANAT, bringing together information and advice for artists and scientists seeking to work collaboratively (www.synapse.net.au/). In addition, ANAT administers a program of residencies with specific host science organisations.

Three ARC bids have been successful in the first stage of the overall Synapse program, involving artists Nigel Helyer, Mari Velonaki and Dennis del Favero. There have also been several residency placements. The database is a substantial resource, though clearly speculative in its practical usefulness. A more coordinated branding of the scheme will develop as outcomes emerge from the 11 projects planned in the first phase ending late 2005, and as collaborative teams perfect describing their projects and processes to those providing funding.

The 4th century BC Greek term tekhne, meaning art in which creating, method and means are wholly integrated, is another useful image in the Synapse context. Nigel Helyer is a notable exponent, maintaining a consistent link between sound, the oral and their transliteration using the combined technologies of electronics, digital media and sculptural forms for over 20 years. Helyer’s practice has often included a close working with technology industries. Developing a relationship with Lake Technology in 1999, his approach to describing a research project using a narrative scenario with tangible outcomes was adopted over their more traditional practice. The tangible outcomes have been of considerable value to Lake, but because the intricacies of patent law (as distinct from copyright) were new to Helyer and the Australia Council, financial returns to the artist have been less than satisfactory. Though this situation is less likely to occur today, it remains an issue for careful negotiation between stakeholders involved in collaboration.

Currently, together with Daniel Woo and Chris Rizos at UNSW, Helyer is working on a raft of projects with a budget of $360,000 over 3 years from the ARC, UNSW and the New Media Arts Board. Some of the projects, such as the AudioNomad series, are developments of his earlier work with mobile augmented audio reality systems capable of navigation and orientation within real spaces. Others include a pedagogic project with the Powerhouse Museum for an audio trail around the Sydney Observatory, a “virtual wall” for Berlin and the Syren installation that will feature at ISEA04 in the Baltic. Here the ship on which ISEA04 will take place becomes the cursor within a sonic cartography, driving a surround sound installation.

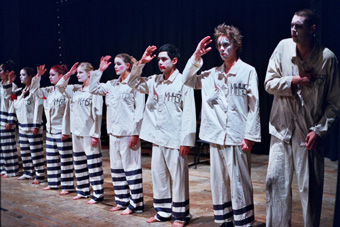

Mari Velonaki is another artist with an on-going interest in the science-art nexus who has received assistance through Synapse. She completed the multimedia performance Phaedra’s Circle in the early 90s in collaboration with Suzanne Chammas and Tanzforum Ostschweiz (where she had studied in the mid-80s), before completing a PhD at COFA in 2003. Formal qualifications are essential in research environments, where they increase the chances of raising research funding. An impressive series of exhibits (including Pin Cushion and Amor Veneris A) were outcomes of Velonaki’s skill-development in electronics and collaborative work with creative coders like Gary Zebington. Through astute networking with the research community and learning their specialised language, Velonaki has immersed herself in the hybrid culture of cross-disciplinary art and science, a world which attempts to balance business and politics with creativity.

Of her current endeavours, she says: “For the last 8 years, the projected character has been a major feature in my interactive installations. With the new project, Fish-Bird, my work moves towards autonomous 3 dimensional kinetic objects. This is a large conceptual and technological shift in my practice and requires a different level of collaboration and support.” The shift from the studio to the laboratory complemented the development of her process: “I felt I had to collaborate with people who were not only proficient with such technologies, but were also innovative thinkers in the use of such scientific knowledge. Working in a large-scale collaborative project requires time to think and evaluate, space to work and test, and sufficient shared activity for ideas to cross-pollinate. The Synapse initiative was extremely important for me, as it provides a framework within which artists can approach leading scientific groups with proposals for collaborations.” The director of the Australian Centre for Field Robotics at the University of Sydney, Professor Hugh Durrant-Whyte, introduced Velonaki to 3 roboticists (Doctors Rye, Scheding and Williams) who shared similar interests and concerns in human-machine interfaces.

In regards to the ARC application process, Velonaki comments: “It is much more complicated than anything I had come across in the arts funding structure. The application itself was 20,000 words and required the joint efforts and commitment of the team for a month.” The outcome was $247,000 over 3 years from the cultural and mechatronics areas of the ARC, along with various combinations of cash and in-kind assistance from the Australia Council, University of Sydney, ANAT, Artspace Sydney, the MCA and commercial company Patrick’s Systems. Defining “in-kind”, and classifying exhibitions as “publications” (academic publishing which scores points towards research status), remain grey areas in translation between the studio and the laboratory. Like patent questions, these issues need to be carefully negotiated on a case by case basis.

Velonaki reports that her group has a genuine collaborative spirit where people are willing to assist each other’s project and her own research and practice is valued and respected: “At ACFR I felt welcome and supported from day one. We have already created a light-reactive installation, Embracement, which was premiered in Primavera 2004 at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Fish-Bird is progressing very well and is going to be previewed as a work in progress at Artspace in August, during the Res Artis conference.”

As Anna Munster observed in RealTime 60 (p4); “By working from a position of mutual respect for their differences and armed with skepticism balanced by thorough research into each other’s respective fields, art and science can come together in modest ways on specific projects.” Through the unique Synapse program, negotiating the sharing of resources and the setting up of creative collaborations between art and science has begun in earnest. Many have high hopes for the rewards.

Intersted readers should check the Australia Council website (www.ozco.gov.au) in late July for information regarding another round of Synapse ARC Linkage Industry Partner grants.

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 38

© Mike Leggett; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The recent Empires, Ruins + Networks conference at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image came as a timely, if tentative intervention in the growing ‘crises’ of art and politics in these postmodern times. One surmises that Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s controversial book Empire (Harvard University Press, 2000) provided the inspiration for part of the conference title and the theoretical impetus behind the many issues it explored.

The judgment of Empire bodes ill for the economy, for society, for politics and for culture. The authors argue that the interaction between neoliberal capitalism and the information technology revolution has produced a powerful system-logic. Since at least the mid-1970s, they argue, the whole of society has become connected, interdependent, and oriented towards the imperatives of capital. ‘Empire’ is thus the empire of capital; the interrelation of ubiquitous computing and omnipresent commodification that has seeped into every nook and cranny of contemporary life. The ‘ruins’ are the wreckage of a civil society where institutionalised politics are wholly ineffectual. And ‘networks’ are the global digital logic that makes this baleful prospect realisable.

A premise of the conference is that the theory and practice of art as a language for critique and as a dimension of a politics for change lies somewhere buried and lifeless beneath the rubble of civil society. Under the regime of neoliberal Empire, art that is not explicitly conceived as a commodity is nonetheless instantly commodifiable. Critique is either non-existent as part of the process of production or it is muted or distorted by the artifact’s exchange value. Coupled with the ineffectuality of mainstream politics, the crisis of art means that principle ways of understanding and changing the world have been repressed and silenced. Reading our children’s books and/or marvelling at, say, the ‘authenticity’ of a Tracey Emin is as good as it is going to get in terms of setting the world to rights or gaining insight into our contemporary condition. Mark Latham rapidly drops one solution for another and the obsession with the dregs of Emin’s life disconnects (and silences) the public politics of feminism from the highly marketable public persona of the artist.

Speakers at the conference, however, lifted the lid on another, presently subterranean logic that is emerging as the dialectical antithesis of neoliberal Empire. Across the world through many differing modes of articulation, networks, art and politics are coalescing in the production of alternative spaces for other ways of seeing and being. Digital technologies are central to this process. Artist/activists are increasingly turning to new media to connect and to collaborate as much as to produce the video or extend more traditional forms of visual art. Moreover, networking through the internet has made many projects observable to others who may want to connect with the existing connections. Through such networks art and politics simultaneously exist both locally and globally.

Highlights of the conference were many, but space allows for the mention of only a few. Keynote speaker Okwui Enwezor argued that the emergence of more collective work in art signals moments of crisis in society and a political reaction to these crises. He cited the political/artistic works produced by the Sarai collective based in New Delhi (www.sarai.net). Here theorists and artists from across the planet contribute to discussion lists, develop visual art projects and produce politically-oriented readers in new media theory and practice that are freely downloadable. Sarai, its website reads, is interpreted as “a very public space, where different intellectual, creative and activist energies can intersect to give rise to an imaginative reconstitution of urban public culture, new/old media practice, research and critical cultural intervention.” As Greek curator Marina Fokidis showed, Sarai has a sort of European-based equivalent in Stalker (2004) a Situationist-inspired Italian architectural collective.

The neoliberal empire takes ‘flexibility’ as its lodestar and ‘information and communication technologies’ (ICTs) as the solution to all problems. Ross Gibson, in his paper “Agility and Attunement” showed how, in a dialectical turn, these processes are being adopted and adapted to produce outcomes that work against the grain of the rigid instrumentalism of the neoliberal way. ‘Flexibility’ in the hands of ICT practitioners with a critical perspective on the dominant order, Gibson argued, may be a highly effective (and potentially deeply subversive) form that could be applied to developing new forms of politics. In this, Gibson echoes Geert Lovink and his theory and practice of “tactical media.”

Nikos Papastergiadis, co-organiser of the conference, closed the 2 day meeting with a reminder that art and politics intertwine. Their immanent power emerges as a “critical vector”, he argued, only when ideas “exist not only in the content of the work, but also in the way it joins up with the experience and ideas of other people.” In other words, in a world characterised by the “banalisation of information”, artists and activists need to make their own collaborations, develop their own matrixes of meaning and articulate these as critical and/or political interventions.

The difficulties facing the renewal of civil society through revivified forms of politics and art are considerable. Conference delegates came only with questions and pointed to scattered chinks of light emerging from the darkness of the ruins. In this sense the conference, one hopes, can be a catalyst for further explorations. What is clear is that collaborative and collective artistic practice will become increasingly political and radical as the crises of neoliberal postmodernity deepen. The key task is to develop ways to connect these emergent political and aesthetic languages with the everyday concerns of people before they become commodified and/or safely marginalised. What is also clear is that in a world reduced by ‘time-space compression’ and bounded by a single circuit of capital, the response must be both local and global, utilising what Ulrich Beck has termed global “networks of diversity.” These will be possible only though critical, aesthetic, political and tactical use of ICTs to create new spaces of meaning and resistance that form the basis of a new politics. The Empires, Ruins + Networks conference showed that this has already begun.

Empires, Ruins + Networks, ACMI, Melbourne, April 2-4

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 39

© Robert Hassan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Gaming is the fastest growing industry in the world, now grossing more than Hollywood in immediate sales. It has been suggested by game theorist Espen Aarseth that “the mass market of computer games is the single most effective cause of the demand for increasingly faster computing from the general public.” Computer game technologies have extended beyond entertainment to be used in the fine arts, education, military, medical, and architectural industries, and have even been used as tools for political amelioration (the US military-designed game SENSE was played by the President and other officials in Bosnia to aid reconstruction efforts). For a technology of such social import, surprisingly little is known about the industry responsible for its evolution.

Offering the public first hand information from game industry insiders is Game Loading, a regular interactive forum organised by the Screen Education department at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI). The forums are open to the public, but are targeted at secondary and tertiary students of multimedia, arts and media studies who are interested in games and might consider the games industry as a potential place of employment. In addition to outlining how animators, graphic designers, filmmakers and sound artists have found employment in the industry without specific game-making experience, Game Loading has raised broader issues faced by artists working in a creative industry which, in many ways, does not yet afford full creativity.

David Hewitt, lead designer at Tantalus Interactive, discussed the frustration faced by game designers who yearn to write interesting, creative games but are limited by the demands of a risk-averse industry. Publishers still prefer to back re-workings of last year’s big hit rather than experiment with novel content. In comparison to the film industry, where some auteurs easily source financial support after a single offbeat art house hit, game auteurs of equal calibre must repeatedly challenge publishers’ demands. Even Will Wright, with SimCity under his belt, found it difficult to develop The Sims because the concept looked poor on paper.

Hewitt feels that the problem ultimately rests with consumers, who continually purchase substandard games due to a lack of knowledge regarding game design potential. For example, Hewitt suggested there is currently room for improvement in the degree of emotional engagement aroused by computer games. He referred to Iko as a singular example of a commercial game that proffers sensitive emotional engagement, eliciting deep empathy between the player and a game character. Other complex emotions such as fear and sadness have yet to be drawn out by game content, rather than the currently sought after excitement and curiosity.

Other works presented at Game Loading, such as SelectParks’ AcmiPark game-based interactive, further illustrate creative avenues that could be explored by game designers given the chance. AcmiPark required the development of a new game engine that could support sophisticated sound requirements. These included: complex, realtime, interactive, generated audio; a live, in-game, streaming concert venue; and the programming of subtle, time-based, tonal variations in sound effects. These developments have put in-game aural aesthetics at a new level. Given the range and flexibility of technology and artistic media available to game developers, AcmiPark suggests that the surface potential of game design has only been scratched.

AcmiPark succeeded in delivering this degree of innovation because of its status as an art-based, non-commercial project. It received financial support from the Victorian State Government through the Digital Media Fund (DMF) and was provided sponsored use of Renderware.

Other game projects to receive arts funding include Escape From Woomera (Australia Council) and Street Survivor (City of Melbourne), but these projects are exceptions to the norm. DMF game funding has shifted direction dramatically since reverting to the control of Film Victoria. Despite the fact that the fund has provided a rich breeding ground for innovation because it is independent of publishers, new criteria demand that all funding applicants secure links with publishers. As a result, Victorian government funding for game development is now delivered to already successful developers, whilst mini-developers focused primarily on research and development are neglected. With the world’s largest publishers, such as Sony, now implementing research and development departments, Australian government funding must support non-commercial development if our industry is to seriously challenge its international competitors.

The next Game Loading will be held in early August, featuring programmer Paul Baulch from Atari discussing Artificial Intelligence in games.

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 39-

© Rebecca Cannon; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

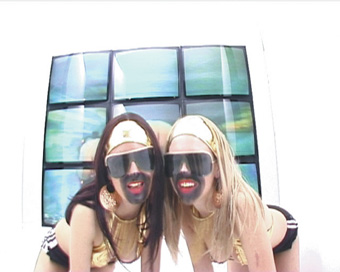

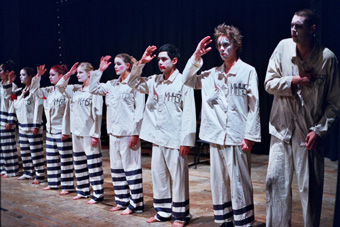

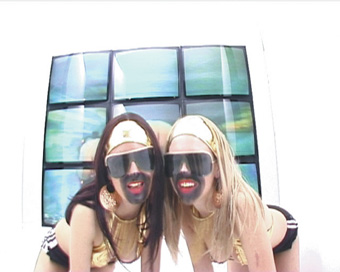

The Kingpins, Versus, 2002

Courtesy the artists

The Kingpins, Versus, 2002

Twin Annie Lennoxes greet the visitor to the second stage of Video Hits at the Queensland Art Gallery. Positioned at eye-level on angled monitors against a cobalt backdrop, the double Annies, from the Eurythmics clip Thorn in my Side, emerge from edited loops of the singer saying, on one screen, the word “you” and on the other, “I”. This whimsical dialogue is at once a quirky comment on the hackneyed themes of love and identity in pop music, and a sly reference to the centrality of the narcissistic trope in video art. It also neatly introduces the exhibition’s key theme: the bringing together of music video clips and video art, forms which share a technological history but whose institutional history and context is significantly different.

The first instalment of Video Hits took place in the central gallery with large rear projection screens, headphones strung from specially constructed overhead beams, velvet-covered bean bags and the high-concept works of music video stars Michel Gondry, Chris Cunningham and Spike Jonze. The second part of the exhibition consists of many smaller screens with headphones lining the length of one wall. The vision has broadened to include more Australian works and an historical survey featuring a range of music clip makers. There are also several key works of video art that engage with music and the visual representations of the music video form. Some of these confront the clichés of music video production with parody, others with creative re-imaginings. All engage in a conversation about the intersection between music, art and the moving image, encompassing the substantial divide between the television format of music video programming and the gallery setting of video art. It is this juxtaposition that generates the exciting frisson of the exhibition, facilitating new connections across genres of video practice and reconsidering the relations between differing histories and conventions.

The selection focuses on parallels and crossovers between contemporary art and music video production with a number of clips by major art-world figures. These include Wolfgang Tillmans’ clip for the Pet Shop Boys’ song Home and Dry and Doug Aitken’s for Fat Boy Slim’s Rockafeller Skank. Damien Hirst’s Country House clip for Blur highlights how dated both Britpop and Young British Art are in 2004, while one of the oldest clips in the display, Derek Jarman’s The Queen is Dead (1986) for The Smiths, holds its own admirably with skilful montage and chroma-key effects deployed to explore some of the aesthetic dimensions of iconographic Britannia.

Literally alongside the high-concept clips of auteur music video creators Gondry and Cunningham, made for big-name music stars such as Bjork and Kylie Minogue, is a selection of video artworks with different aesthetic and ideological prerogatives. Much contemporary video art continues to articulate themes first explored in the feminist video work of the 1970s. Personal subject matter encompassing identity, autobiography and remembrance, relation of self to others and exploration of self through personae was frequently expressed in the 70s via the direct address of the solo artist, whose body often formed the centre of the work. This same spirit of enquiry is still very much in evidence in today’s video art, with the added patina of ultra-voguish low-fi 80s fetishism.

Video Hits includes key works by Pipilotti Rist and Annika Strom. Strom sings her own compositions to the accompaniment of a simple Casiotone, and a meandering personal video featuring her parents, daily chores, footage filmed from a television screen and a diary of her art practice. Rist is shown singing along to other songs, overpowering and distorting the original with her version. Katie Rule’s garage re-enactment of the dance sequence from Thriller also affirms the body as an expressive site. While some may agree with Rosalind Krauss’ tart characterisation of video art as fundamentally narcissistic, a simplistic dismissal of these works as self-indulgent play-acting necessarily ignores their power.

These works continue the feminist project of validating personal history as subject matter and its challenge to dry formalism and ossified notions of ‘the beautiful.’ These artists conflate or sublate the division between art and life and understand art as a social practice. As part of this ongoing use of video art to generate discourse about ‘the personal’ and its political dimensions, artists featured in Video Hits can be seen to be reclaiming the female form—not just from male artists, but also from the commodifying proclivities of the video clip genre, where extreme examples of exploitation and unhealthy representations of women are, disappointingly, iconographic staples.

In addition to these performative urges are video artworks which emphasise editing as the central expressive device for moving images, such as Art Jones’ juxtapositions of popular songs with obscure and disturbing imagery, or Ugo Rondinone’s hypnotic re-edit of a Fassbinder film with different music. Though still crucial, music operates here as a creative element of post-production, rather than the raison d’etre for production.

Video art, while it emerged from the technology of television, is often centrally concerned with distancing itself from that medium, and its preoccupation with disavowing its ‘frightful parent’ can be seen at Video Hits in works such as the clips by Sydney video artists the Kingpins, which parody the unoriginal and aesthetically obnoxious visual clichés of many rap and metal clips, and Tony Cokes’ text-based dissertations on the politics of the music industry.

The exhibition has not tried to conflate video art practice with music video production; rather, it situates the 2 as overlapping in many areas (Jonze’s infamous Praise You street-theatre clip is also a masterful piece of video art), but with different prerogatives. In video art, ‘representation’ is unmoored from the band/performer as a central structuring element and floats freely through critique, parody and creative probing, whereas art and technique in video clips, ultimately, are subordinate to selling the band and their music. The music video genre doubtless offers a platform for remarkable innovation and the Video Hits selection showcases this with some stunning commercial works, particularly those from Gondry. However, the clever curation of video artworks that not only engage with the music video form, but mount a critique of music television, means that Video Hits also constructs a kind of intra-medium discussion.

In the same way that video artists work with existing imagery or songs and rework them, much of Video Hits is about recontextualising the art of music clips in the environment of the art gallery, where they can be considered alongside reflexive video art. Given the increasing attention being devoted to the music video form as art, it’s a timely vision and a bold project exploring the multifaceted bases of video practice.

Queensland Art Gallery, Video Hits, various artists, Stage 1 Feb 21-April 12, Stage 2 March 27-June 14

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 40

© Danni Zuvela; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Derek Krekler, Holey 1, 2003, type C photographs, diptych

Courtesy of the artist and Margaret Moore Contemporary Art, Perth, 2004 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art

Derek Krekler, Holey 1, 2003, type C photographs, diptych

Any assessment of a survey like the 2004 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art is inevitably problematic. The works cannot be addressed on individual merit when their very inclusion is always an issue. Why that particular artist? Why that particular work? That the Biennials are themed is another facet attracting judgement, both in terms of the works’ relationship to the focus and the perceived validity of that focus. The grouping of traditional photography, film and digital technology this year under the nomenclature “photo-media” can also be interrogated or accepted according to individual opinion. There has been criticism of focusing on medium as a selection criteria, although it’s surely accepted that photography has transcended its materiality and become, as the most pervasive mode of representation as well as a key mode of self-representation, a valid avenue via which to assess contemporary culture and society. In this sense, the 2004 Biennial was certainly better than 2002’s conVerge: where art and science meet, where there was too much science and not enough art.

Although curator Julie Robinson stated that the Biennial had no theme “as such”, she also described how common threads appeared, with the artists engaging “with society, the world and the human condition” (exhibition catalogue). Some works do this explicitly. For example, Mike Parr’s painfully fascinating UnAustralian which documents the un-anesthetised artist having his lips sewn together, and Linda Wallace’s entanglements, a conglomeration of images culled from televised war coverage. In addition to the direct reference to the mediation of reality via television (framed by net curtains à la lounge room viewing), the slippery relationship of digital representation to reality is highlighted by the fact that, as Chris Rose points out in his catalogue commentary, any kind of magnification doesn’t evince detail, as would usually be expected, but rather disintegrates it.

Part of photography’s seduction is its status as a trace of the real, the result of a chemical reaction triggered by exposure to light reflected off the lines, curves and angles of physical objects and beings. Deborah Pauuwe’s photographs in particular seem to adhere to this in her sensuous tracing of her subjects’ surfaces. The young girls of Dark Fables, in party dresses with painted faces, are larger than life, their skin, hair and the curves of their features all rendered under incisive light that allows our eyes to roam their exteriors and visually consume them.

Craig Walsh’s ingenious video similarly offered an unusually intimate perspective. Cross-reference displays footage of crowds at an outdoor festival who, walking past the camera, bend down one-by-one and peer searchingly into the lens. Thus absorbed, they become completely unselfconscious and the viewer in turn unselfconsciously examines individual facial hairs, the outline of a nipple through a bikini top, or the very intimate movements of mouths slowly forming unheard words. As well, Walsh neatly addresses another common issue of contemporary photography: the viewer/viewed dichotomy. The work is rear-projected through an ajar ‘door’, creating the impression that these people are staring into the gallery space itself. While such scrutiny demonstrates the infinite individuality of human features, the procession of faces eventually blends into one. Likewise, the characters in David Rosetzky’s Untouchable speak with their own voices, cadences, rhythms and inflections, but the stories they tell are (literally) the same. Untouchable comprises 3 screens depicting actors performing monologues, of alienation, emotional abandonment, or the genesis of passionate relationships. Eventually it becomes apparent that, although narrated each time by a different character, the same stories are being told verbatim.

Derek Kreckler’s work also plays with narrative, with the paired images of Holey 1 depicting 2 views of the same beach scene, the tableaus only marginally separated in space and time and their temporal order left unclear. In addition, circles of the image have been excised and reproduced as small globes set before the photographs. This reconstitution in 3 dimensions seems both a comment on the way we see much of the world via 2-dimensional representation and a reassertion of (despite a Biennial’s worth of photo-media to the contrary?) the very 3-dimensionality of physical existence.

2004 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Contemporary Photo-Media, curator Julie Robinson; Art Gallery of South Australia, Feb 28-May 30

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 41

© Jena Woodburn; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Three major group shows recently highlighted the healthy state of contemporary Tasmanian art practice. The local artists on display (one exhibition also had an interstate contingent) gave a good overview of the state’s current artistic trends.

Body Bag showed at The Carnegie, Hobart Council’s contemporary art space. The participants, from the dynamic Letitia Street studios, were asked by curator Malcom Bywaters to utilise the body as a metaphor for island. While it is doubtful that all 10 of the exhibitors entirely addressed this theme, varied and engaging work resulted and the participants are among the state’s best emerging artists.

Neil Haddon’s resolutely geometric painting, Slip No 2, with its skewed perspective, effectively uses high gloss household enamel on aluminium. However, it requires an anecdote in the catalogue essay to fit the work into the curatorial theme. Colin Langridge, a talented designer and sculptor of some sophistication, reverts to a style of sculpture that is figurative, yet almost primitive in execution. His work depicts a human vertebra. Richard Wastell, arguably one of Tasmania’s most important younger painters, offers a striking, large 4-panelled oil of a forest view with quasi-realistic elements and a kind of trompe l’oeil in play throughout. Sally Rees makes interesting use of video projection and Matt Warren’s video and sound installation is minimal and compelling.

At the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, the new Director of Contemporary Art Services Tasmania, Michael Edwards, curated Group Material. This was a show with potential, despite the scant dimensions of the TMAG’s new gallery space. Too many of the works had also been exhibited previously.

Group Material showcased the work of 6 important artists: Ben Booth, Neil Haddon, Anthony Johnson, Anna Phillips, Lucia Usmiani and Kit Wise. All are currently, or were recently Hobart-based. All incorporate everyday items or substances in their art-making. Appropriating and recontextualising these materials, the artists extend the discourse between art and consumer culture.

Standout exhibits include Anna Phillips’ 2 works featuring solidified shampoo, bathwater and colouring. One is a seductive gold blob, plinth-mounted; the other 3 replicated aqua towels, hanging on bathroom rails and again made from Phillips’ tactile and seductive shampoo mix. Lucia Usmiani’s wall and floor piece comprised silver-coloured bases of hundreds of soft-drink cans, overlapping like the patterning of fish scales. Usmiani is a dedicated practitioner of tremendous originality and the sheer beauty and ingenuity of this work made it a real crowd-pleaser.

The other exhibition recently curated by Malcom Bywaters at the School of Art’s Plimsoll Gallery features some very exciting work by artists with Tasmanian connections as well as interstate practitioners. I’m not sure why it was entitled Boogy, Jive & Bop, as the exhibition did not seem to address any of these, though the work was undeniably ‘hip.’ Moreover, the catalogue, via artists’ interviews, made extensive reference to September 11, an event not mirrored in the works. Perhaps the catalogue was intended as an ‘add-on’, or even a kind of discrete exhibit in itself, reminding us that art-making persists even in the face of the worst disasters.

Among some very stimulating pieces, Jane Burton’s Type C photographs, The Other Side, depict glowing, deserted telephone boxes at night with an eerie surreality. Stone Lee was born in Taiwan and now lives in Launceston. His 3 strange assemblages are fascinating in their simultaneous identifiability and recontextualisation of materials. All entitled Everydayness, they utilise acrylic media, newspaper and found objects. Danielle Thompson created some highly seductive and beautiful lightjet photographic prints full of abstract movement and lush colour. Shaun Wilson is an engaging artist and his hypnotic video My Sweet Mnemonic Wonderland also uses vibrant colour and slow, contemplative movement. This talented artist’s work provides a good foil, both in medium and style, to the other pieces in Boogy, Jive and Bop.

Given that these are some of Tasmania’s newest artists, it was heartening to see the intelligence, talent and originality on display in all 3 shows. On a related note, the work of Megan Keating, melding pop culture and an obsession with military symbolism, features in Body Bag and constitutes the first show at Hobart’s newest commercial exhibition space, Criterion Gallery in the CBD. With its sound artistic ideals this will be a venue to watch.

Body Bag: Somewhere Over the Rainbow, curator Malcolm Bywaters, Carnegie Gallery, March 18-April 18; Boogy, Jive & Bop, curator Malcolm Bywaters, Plimsoll Gallery, March 5-28; Group Material, curator Michael Edwards, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, March 18-May 2

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 41

© Diana Klaosen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

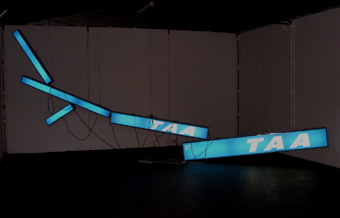

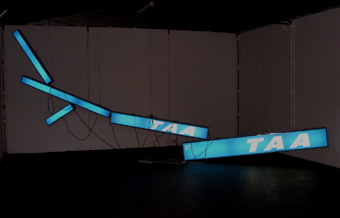

Matt Bradley, Ghost Gum

Although presented as one body of work, the pieces comprising Matt Bradley’s Dark Crystal show each contained sufficient material to stand alone. Indeed, the series of suspended light boxes entitled Ghost Gum is the epitome of all that is currently favoured in contemporary art. Featuring the blue and white logo of the defunct airline TAA, its luminous arms were cool and aloof. However, its combination with the artist’s Cnr of Danby and Carlton, Torrensville and Giant, gave the exhibition a more experimental and nuanced effect.

Shadowed by Ghost Gum’s elaborate structure, Cnr of Danby and Carlton, Torrensville depicts a Qantas jumbo flying low overhead, lights blinking forlornly against a dim grey-blue sky. Printed large and cropped crookedly outside the image’s border, the still has been pinned upside-down to the wall. This isn’t, however, immediately apparent: the plane still looks ‘right’ and is instantly identifiable. So what gets thrown by this reversal? Not gravity—the plane is still definitely, defiantly suspended. Rather, the effect is reminiscent of a film in which someone has been shot walking backwards, but is then played backwards, so that they appear to be walking forward. Or when magicians Penn and Teller film themselves strapped upside-down, so when the footage is screened the ‘right’ way, objects released from their hands look like they are flying rather than falling. Despite appearances, we pick up from small cues that something is not quite right. The plane is flying, but according to rules of physics different from our own.

What would be the destination of such a craft? Maybe the realm of Giant, one of Bradley’s self-described alter egos whose world features in eponymous stencil works. The square-jawed giant—oversized by our standards but normal in his own environment—is one of the many fantastic dwellers in this blue-and-white-toned world of clouds, snow and castles. Presented on small, unevenly cut boards, the components of Giant are less finished works than works-in-progress, creating the sense that they might be documentation rather than the products of sheer imagination. Combined with the small photograph of a silhouetted tree branch, Lucy and the Apple Tree, and preliminary sketches for Ghost Gum, Giant is not so much a discrete piece of art whose meaning or purpose is at once internal and evident, or limited to itself. Rather, the addenda act as footnotes, annexes, yielding insight into an intriguing inner world. This is a relief from the pervasive self-absorption of so much contemporary art, and its charm lies in this turning outwards, towards fantasy, make-believe, other worlds. And all the works in Dark Crystal essentially offer this, via the airline that enables your getaway, the actual plane on which you can escape, and your other-worldly destination.

Dark Crystal, artist Matt Bradley, Project Space, Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia, Feb 27-April 11

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 44

© Jena Woodburn; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

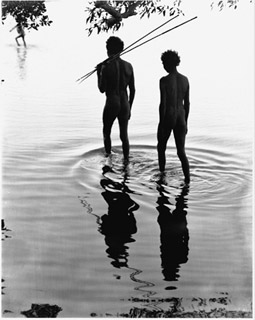

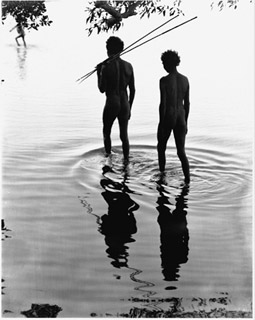

Sandy Edwards, Marina and Laura in Lady Grounds Pool,

Sandy Edwards, Marina and Laura in Lady Grounds Pool,

Bithry’s Inlet, Tanja, NSW, 1998

Indelible represents the suite of images that remained after photographer Sandy Edwards spent months viewing, re-viewing and culling the hundreds of rolls of colour film of family and friends that she had shot over the last decade. The images record Edwards’ visits to some of her favourite haunts, such as New York City and the New South Wales south coast, as well as documenting certain rites of passage and leisure activities of her close personal network. A child opens a Christmas present while another squirts a hose at the camera; a pair of adolescents pose in formal wear while others lie face down on the surface of a rock pool; a girl surveys a wedding reception, while another warms her legs by a fire.

The challenge faced by the artist, as Edwards herself describes it in her room-sheet notes, was the transformation of these images from personal snapshots into an exhibition with broader, or ‘universal’ appeal. Edwards has attempted to achieve this through honing in on content, selecting representations of those moments in life to which most of us are witness, events that mark the passage of time or personal change, such as weddings and birthdays, holidays and house-warmings.

There are several perils in such an approach. One is the by now familiar dubiousness of the traditional documentary photographer’s credo of truth and objectivity. Another is the equally problematic nature of any appeal to the ‘universal’, whereby culturally specific assumptions are necessarily made but not always acknowledged. Further, there is the related risk that in aiming for the general, one might lose the poignancy of the particular.

Edwards may have run these risks, but her erudition and experience allow her to navigate them, albeit with varying degrees of success. Her role in the documentation process—the images are to some degree autobiographical, with the artist herself appearing on occasion—is explicitly acknowledged, underlining the subjective nature of photography. The titles of the photographs locate them very specifically in time and place, as does the frequent reliance on the genre of portraiture that heightens the individual identity of the subjects; clearly these images are less universal than representative of a particular class and lifestyle. However, despite this, some of Edwards’ images fail to engage, and appear to suffer from a lack of intimacy. Perhaps, in seeking a more public mode of address, Edwards has at times sacrificed a personally charged register.

There is a sense of emotional reticence about some of the images, as if any scenes deemed too intimate or revealing have been edited out. For example, awkward moments are not really tackled, although there is a moving hint of discord in one title that tells us the artist’s mother no longer wishes to be her daughter’s subject. Indeed, at times the portrayals tip into the anodyne, remaining unremarkable and prosaic, not unlike those shots in an ordinary family album that attempt to evoke the significance of events through their sheer quantity rather than through a definitive image.

As a result, it is those photographs tending to the abstract, which demand a shift in the mode of spectatorship, that are the strongest and most evocative. When Edwards’ unmistakable eye for colour and composition is most in evidence, her photographs come alive for this viewer, as in the vibrant contrasts in Merilee’s hands, where fingers are outstretched to a pot belly stove and clothes highlight pattern and colour; or the cool sinuousness of Lisa’s legs in mum and dad’s pool; or the delight in the abstract arrangements haphazardly created by Adrian’s sarong blowing on my mother’s clothesline and Byron Bay Classics cozzies. The appeal of such images lies largely in Edwards’ ability, through her formal strategies, to transform the unremarkable into the aesthetically delightful. Her photographs infuse the ordinary with beauty in such a way that the viewer can bring a refreshed vision to his/her own surroundings, with eyes more attuned to colour, pattern, correspondence.

One correspondence that repeatedly structures Edwards’ images is between people and nature. A certain unapologetic Romanticism permeates her compositions: people are often shot in natural landscapes, or at least in contact with natural elements such as fire and water, with an emphasis on ‘naturalness’, ‘immediacy’ and ‘sensation.’ The urban shots, by contrast, tend to be less inhabited: fragments of the built environment, such as a neon sign or pedestrian crossing, stand as synecdoches for the city, while portraits shot in the street are closely cropped to limit the allusion to place.

While the emotional reticence and prosaic nature of some of the images detract from their power, this is counterbalanced by the formal rigour, aesthetic empathy and affirmation of human/nature interaction in others. On viewing this exhibition, I was reminded of Susan Sontag’s observations in her recent book about the ethically dubious nature of “regarding the pain of others.” Perhaps in offering us images of everyday beauty, Edwards is honing our powers of attention more effectively.

Sandy Edwards, Indelible, Stills Gallery, Sydney, March 17-April 17

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 45

© Jacqueline Millner; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

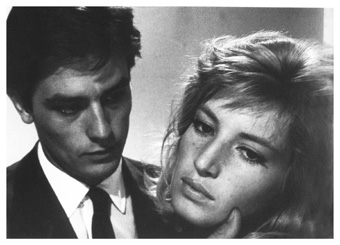

David McDowell, The Passenger

Courtesy Canberra Contemporary Art Space

David McDowell, The Passenger

In The Passenger David McDowell explores the contrast between still images and time-based video as a way of demonstrating the traveller’s experience of time. These 2 media forms remain separate in this large installation, in which the artist sets up a tension, yet narrative connection, between motion and stillness.

Large panels hang around the gallery like makeshift walls in a theatre set. Each panel comprises a grid of separate stills. Printed on transparent film stock, the back-lit images resemble projected moving images, only they are motionless moments caught in time. The fragmented surface is deceptive, with each still like a David Hockney photograph, capturing part of a larger image. With different depths of field for each fragment, it takes some time to focus and decide whether the panels in their entirety capture the vista of a passing mountain range, the view through a travelling car windscreen, an aeroplane wing on a tarmac, or sleeping passengers in a transit lounge. It is as if you have lost your focus in that moment of travel through unfamiliar places.

The artist seems to revel in the romance of older forms of apparatus used to capture and display images, alongside an acknowledgement of modern technologies like the domestic handycam. The lighting set-up on the panels recalls the bygone era of slide projection and the family display of slides from overseas trips. The stills, printed in muted tones, have a warm old-fashioned feel, with the light seeping through from behind. Each image looks like an old monochromatic photographic plate that you hold up to the light to see detail. They reminded me of a very old clunky projector that my father had, which required the viewer to slide in each precious glass plate to bring the image to life on the wall. The notion of projection in these static images intersects with the 2 centrally placed video works when you enter the gallery.

The first video work you encounter is screened on a monitor. The second is projected onto a hanging panel constructed from the same materials as the panels of photographs. The video on the monitor has a highly compressed quality, making the image blurry and again hard to focus on. The projection seeps through the hanging panel and can be seen in fragmented parts on the back. Both videos capture a moment of travel; a plane leaves the tarmac on the monitor and a car drives through a tunnel in the projection. These moments of time are slowed down and looped in an endless monotony. There is a connection with the still imagery combined with a sense of dislocation, of the world passing by while you are standing still and going nowhere. I got caught up in the tunnel and found a connection with the low droning audio track that permeated the space of the gallery. The soundscape seems to use treated environmental recordings, which can only occasionally be synched with the moving images. There is an instant where the sound of truck brake exhaust can be linked with truck headlights gliding through the frame. Placing these sounds with the moving images resonates with our attempts to focus on the wider image on the panels and form some kind of connection and escape from the shifting terrain of being a moving passenger.

In The Passenger, David McDowell uses the differences between stasis and movement to play with our perception of time, questioning the progressive narrative of the moving image. The viewer reading the panels pieces together static fragments to create a scene. The viewer watching the moving imagery arrives in the looped narrative and travels only part of the journey, never really going anywhere.

The Passenger, photo and video works David McDowell, sound Somaya Langley; Canberra Contemporary Art Space, March 26-May 1

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 45

© Seth Keen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ricky Swallow, Killing Time (detail), 2003-2004

Courtesy of Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney

Ricky Swallow, Killing Time (detail), 2003-2004

In the middle of a darkened space sits a heavy, old fashioned and roughly hewn kitchen table. A single spotlight illuminates fruits of the sea spilling out over the table top: dozens of oysters, a crayfish on a plate, squid, snapper, mullet and garfish. A knife rests on the edge, next to a lemon that is partly peeled, its skin curling away off the table. This cornucopia is laid out for our viewing pleasure.

Ricky Swallow’s sculpture/installation Killing Time possesses a ‘gasp’ factor that turns adult viewers into kids dying to touch. What takes our breath away is the fact that nothing is as it appears. The entire work—from the fragile curling lemon peel and the finely wrought legs of the crayfish, to the bucket and folded cloth—has been meticulously carved out of wood. Swallow’s mimetic skills are awesome and his ability to re-present reality captivates audiences who can’t seem to help taking a ‘reality check’ through physical contact with the work. Little wonder the gallery positioned an attendant to watch over it.

Ashley Crawford wrote in The Age (April 17) that Killing Time is based on Swallow’s childhood experiences as a San Remo fisherman’s son. Without doubt this work is personal, but it connects with viewers on a far more profound level. For all the carving skill demonstrated in the recreation of this laden table the work is disconcerting. There is no tell-tale fishy smell or seductive colour, no sounds of laughter or kitchen noises that such bounty would engender. It is as if all the life and colour has been bleached out of the scene.

Given that Swallow dedicated 6 months to crafting the work, Killing Time is an apt title. However, the title, the dramatic chiaroscuro lighting and the tableaux link the work to the Dutch and Flemish traditions of still-life painting or natures mortes— literally ‘dead life’. Seen in this light, Killing Time potentially takes on a political edge.

At a literal level, Dutch still-life paintings offer a skilful mimetic rendering of simple everyday things. However, simultaneously these everyday things assume symbolic meaning, a warning against the seductiveness and emptiness of material excess, reminders of the need to maintain balance between the spiritual and carnal. Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin’s La Raie (The Rayfish, 1728) for example, warns of the danger of licentious living, through its juxtaposition of sexually laden symbols: a cat with its hackles risen, oysters, jugs, the underside of a rayfish and a knife balanced on the edge of the table with its blade thrusting into the delicate folds of the tablecloth.

The similarities between the composition of Chardin’s La Raie and Swallow’s Killing Time begs a reading of one through the other. In La Raie, we are also presented with a rough hewn kitchen table groaning with seafood. And I ask: What does it mean to show the underbelly of a rayfish or to present a profusion of oysters? Is the knife balanced on the edge of a table just a knife or does it signify how delicate the balance of life is? Why is Swallow’s knife balanced on the edge of the table? Is the half peeled lemon hanging precariously off the side of the table intended to show the virtuosity of the artist, or something more significant? And why has the artist presented the crayfish with its underbelly to us in a state of helpless vulnerability and impotence?

In the silence of the gallery space viewers have responded to Swallow’s work in whispers and with an almost religious reverence. Yes, the work is a virtuosic feat. However, in the tension between its tactility and untouchable fragility it demands that we do more than just gasp in awe. In his interview with Ashley Crawford, Swallow makes the evocative comment that Killing Time is something to do with “owning up.” Perhaps this is what the work is asking of us.

Ricky Swallow, Killing Time, Gertrude Contemporary Art Space, Melbourne, April 2-May 1

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 46

© Barbara Bolt; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

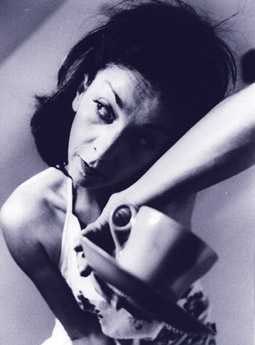

Maria Blaisse, Silverspheres, 1989

photo Anna Beeke

Maria Blaisse, Silverspheres, 1989

Remember when we dreamt of cyborgs and talked about “becoming” as if it all actually meant something? As if it was possible, this future of endless human plasticity? It seems naïve now that we’ve grown beyond the narcissistic phase of our social evolution and have a better grasp of the limits of our bodies. Now that we remember before bodies mutate they break, mash, incinerate, humiliate, decapitate. Humpty can’t be put back together again.

It’s because of this that I feel if I was looking at the work of Marie Blaisse at PICA, say, 5 years ago, I might have had a different reaction. Today I cannot help but respond with a sort of melancholy; that of the disenchanted futurist. Blaisse’s work was for me a phantom limb, missing but present, a reminder of a whole we once enjoyed, that we maybe took for granted, made too much of. As such, it is somehow more than just Lucy Orta for jazz ballet fans…as the faintly thrumming pain throughout this latently morose show gives it a kind of dignity I wouldn’t have thought possible.

Admittedly, these sombre reflections were far from my mind when I first dipped into the show. It did what I’d thought it would: reactivated all the striving playfulness of the 1980s and early to mid-1990s. The retro, brightly coloured foam costume pieces Blaisse is known for were strewn about the floor with a casual, licorice allsort quirkiness. A few dangled from the roof. The feel was Yazz meets Bananarama downtown at Mangoes for Shirley Temples—light, giddy, soft. This cutie harmlessness was amplified by the kids playing with the costumes, supervised by smiling, good-natured gallery staff. They placed tubes on their heads, slotted skinny arms through cymbal-like shapes. It was goofy good times and arty/fashiony merriment.

This feel was matched in the Paula Abdul video piece where dancing fascists in Blaisse-molded attire gleefully gyrate and hump and goosestep and jitterbug and arse-bounce. Foam-fattened cartoon frames for the Abdul stage show, they were more properly part of an extended extravaganza that had begun with Kiss or Bowie and led to Michael Jackson and worse and then worse still. Art or fashion (or whatever the hell Blaisse does) was a stadium act, just for a moment, but in the process was reduced to being simply part of the era’s dominant culture’s yearning for surface glitz. It’s worth comparing Blaisse’s work for Abdul with Cirque de Soleil’s efforts for New Order in the True Faith video. The French company used a similar aesthetic but to a more rabidly creative and compellingly artful end. Blaisse’s effort couldn’t escape the gravitational pull of the middle-of-the-road. It ended up as its road kill.

Naturally, this satisfied-with-itself escapade was the least interesting part of the show. The film work (produced in collaboration with dancers/models and filmmakers) was an altogether different experience, albeit one that revealed its intensity only on repeat visits. It took solid time and effort to clear away the surface froth to get at the fragile, haunted skeleton of this richly cold work. In one monitor-based work, for instance, we see a woman wrestling with gravity wearing a red, bud-shaped hoop around her waist. One moment she’s Kafka’s giant beetle who cannot right itself. Next she’s Minnie Mouse. Then a ladybug. Oh, metamorphosis is just so fucking hard.

The other works, tucked away in the screening room, took this dynamic to another level entirely. Immensely, awkwardly artful and fun—Godard for the Xanadu generation—they were full of unexplained, unexplainable jump-cuts, formal interruptions and visual and auditory non-sequiturs. Uniting this strange fruit was the fact that the otherwise graceful models who sport Blaisse’s works are forever struggling with the limitations of their new appendages. Blaisse’s bodily additives are definitely, defiantly prototypes. The films are test runs. The models are the fashion world’s equivalent to crash test dummies (which maybe they always are?). My favourites involved rollerskating women (precursors to the genius video for Cat Power’s Cross Bones Style?). One skate flick features a gal with elongated arms connected to her feet. She’s a bug bent on all fours, but not quite; suddenly the arms dislodge from the feet, and she doesn’t know what to do. Then she (or was it a man?) is spinning around, legs splayed thanks to a foam insert.

The rollerskates are significant here. Both skates and the foam body attachments extend and amplify bodily pleasures. Despite this, the logic of the films offers pleasure and then achingly hems it in: the performers are specimens acting out their limitations and possibilities in rooms of clinical clarity and texturelessness. Ultimately, this instills a sense of elegiac melancholy that overrides any overt playfulness and evokes more than a whiff of S&M (in the Freudian sense).

So when, as in the glorious images of a woman’s back turning into a dove, the body reaches a state of grace, it does so surprisingly, as a temporary release made all the more sweet because of its cloistered context. What is clear is that elegance is also a result of being frozen rigid. Indeed, in the still shots of Blaisse’s work on models, the body is pure graphic. The head appears severed from the body. Limbs protrude, a new being is created. The film works, though, show that this is merely an empty promise. The condition of human as graphic is an interlude, a fantasy, a projection of art.

Of course, Blaisse’s work activates these dynamics within a very precise context of sartorial modernism. Elements of futurism and surrealism fuse with 1960s design sensibilities of a Panton-gone-to-the-Moon flavour. There’s something retro-futuristic about Maria Blaisse’s work, but it has learnt from, and moved past, its inherited utopianism. Nevertheless, the thin margin for pleasure, within and against restraints, is obvious and locates her alongside designers such as Belgian Martin Margiela who continue to make fashion along the line between containment and chaos.

Curiously, the flaws in the show’s presentation, while initially annoying—the lack of labels, monitors running side-by-side with inaudible sound—aided the Blaisse effect. Blaisse’s work is best approached at a remove, as a memory trace, as a gesture that doesn’t hold. At its best it opens up the problem of being human, at its worst it is a distraction. It’s pleasure and pain, pop and philosophy, lycra and foam as existential fundament.

Marie Blaisse, Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, April 1-May 9; part of The Space Between: Textiles_Art_Design_Fashion

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 46-

© Robert Cook; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

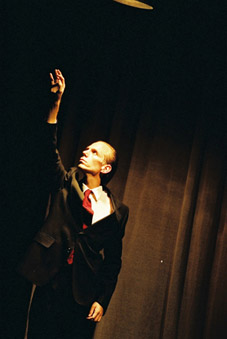

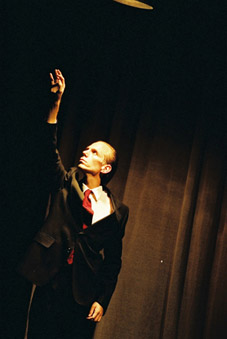

Martin Del Amo, Unsealed

photo Heidrun Löhr

Martin Del Amo, Unsealed

The performer smiles. She’s met a policewoman who has confided tales of her dysfunctional relationships. She makes a series of tentative moves, a little half dance of self-protection, a hand swinging almost instinctively over the groin. She moves along the wall, a dance suggesting impact and defence. An alarm summons her to a desk where she operates a transcription machine with her foot while typing the policewoman’s words onto a laptop (for us they unfold on the screen behind her). She stops, rewinds, catches up, ignores errors, speeding on as the story spills out. In it the policewoman transforms from victim to defender to near-murderer of her attacker, her partner.

The performer joins us at the front of the space, sitting, smiling, commencing a slow, silent writhing and twisting, conveying a desire to burst free, but also strain, the anxiety of the almost-murderer as the recorded voice runs backwards in aural space around us. Eleanor Brickhill’s performance in An Unknown Woman is the embodied emotional aftermath of the story, it is an act of empathy, acknowledging moral complexity, a taking in of a story and of a fellow being. This short, tautly contained work makes an intriguing companion piece to Kay Armstrong’s The Narrow House in which we see the premeditation of a female murderer (see article).

In Stand Still, a small precise work, 2 dancers share a space, together and apart, but never in a duet. One turns and turns, slowly, an arm out, leading. The other’s simple articulations suggest semaphoring, a vertical to the first’s horizontal reaching and turning back in. Stillness. They start up again, the movement slightly faster, more articulation, greater extension, Nalina Wait is fluid, bending at one knee to reach out further, arms arching out, hands in to meet with a sense of completion. Lizzie Thomson opens out and up, more angular, less certain. Stillness. Here too is empathy, across different forms and rhythms, sharing the same space, the same momentum and stillnesses, like a dialectic that almost but never resolves.

A man paces in his underwear. Is he lost? Looking for something? Mapping out space? The walking becomes almost hypnotic, its obsessive footfall subtly extended by a sound score evoking stranger spaces than the one we see before us. Between these walkings (rectangular mappings, sudden diagonals, impulsive stop-starts, on the spot reachings-up like involuntary signallings, half-squats, circlings) the man stops, faces a mirror, wipes himself down, drinks water. These are quiet, slow moments. He looks at himself. Each time he stops here he adds an item of clothing before coming to address us, or, once, singing…before setting out on another, more intense walk, the sound score sometimes pulsing as if rippling through him and, in a rare moment of extroversion, suggesting a demented carnival.

He addresses us quietly. He’s been to a psychiatrist, not that he’s off the rails, “but if the rails are not clear…” It’s about loneliness he says and the thin line between self deception and self perception. About what you want to be…a singer? Is it about happiness? He thinks we can get “homesick for sadness…we wouldn’t be happy without it.” Later he talks about a moment in his flat, an impulse to destroy, and acting on it, tearing apart magazines, documents, passports…but, unable to let go, keeping them in blue plastic bags sitting on the top of bookshelves. By the time he sings, a searching, fine interpretation of a Friedrich Hollaender and Robert Liebmann cabaret song, he is fully dressed. The suit appears to contain him, bulking the strange reaching gestures—a half-hearted aspiration for transcendence? He walks again, looking to connect. He stops, he shudders.

The piece resonates with the nuanced musings of Gail Priest’s improvised sound score which involves the miking of the space to pick up, amplify and ever so slightly alter del Amo’s footsteps, breath and movement. When he sings, the increasing resonance has the effect of separating the performer more and more from the real world as he retreats into that of the cabaret singer, and also pushing the microphones to the point where they too ‘sing.’

At 40 minutes, Unsealed is a complete, quietly disturbing, confiding and important work from Martin del Amo that makes an art of walking, invites our empathy and offers a sad paean to the virtues of melancholy.

Performance Space, Parallax: An Unknown Woman, Eleanor Brickhill, sound Michelle Outram; Stand Still, Nalina Wait, Lizzie Thomson; Unsealed, Martin del Amo, sound Gail Priest; design Virginia Boyle; producer Fiona Winning, lighting Simon Wise, project coordinator Michaela Coventry; Performance Space, April 21-May 2

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 47

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

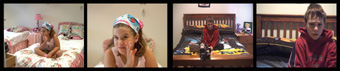

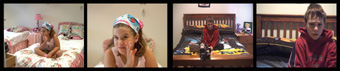

Kate Murphy, PonySkate, 2004

Courtesy the artist

Kate Murphy, PonySkate, 2004

PonySkate, the latest work from Sydney-based artist Kate Murphy, investigates the world of the child and the video camera. A 7-year old boy and girl from different families is each given a camera to record their lives from Friday afternoon through to Saturday. As they go about their normal routines after school, play, dinner, and Saturday morning fun at the pony club and skate park, a second camera, set and left on a tripod, is also running. Extracts from the resulting 4 video threads have been synchronised and shown on separate monitors in the final installation.

As Murphy observes; “The home video has now replaced the stills camera as the favoured instrument to record childhood occasions and history. From the youngest age, children now grow up understanding and at ease with performing/living in front of the camera.”

Video conventions are also replacing the traditional grammar of film. Big Brother contestants exist in a seamless video force field. Video is spontaneous, like everyday life, and unobtrusive, like surveillance. PonySkate explores not only the effect of the ubiquitous camera on the child’s evolving sense of self, but also points to a generation who will have a greater familiarity with the moving image as a means of communication than any before them.

Since graduating from the ANU in 1999, where she received the University Medal in Visual Art, Murphy has been exploring the documentary impulse, working with multi-screen installations to develop a space where the need to organise a beginning, middle and end from the messy stuff of real life is less pressing than in the linear form. Murphy reveals her subjects through the careful establishment of formal limits, both during shooting and in the installation design. Despite the absence of narrative, her works are compellingly intimate and thoroughly engaging.

PonySkate uses multiple sets of opposites to examine the lives of the 2 children: male and female, portrait and self-portrait, mindful and oblivious. A humming tension is established within and between these pairs, but it’s difficult to concentrate on all 4 screens at once, so the viewer becomes an editor, drawn to certain images, making selections and assigning hierarchies.

The central device of synchronised cameras, one operated by the child and one by the artist, is at the heart of the work. A real conversation builds between the 2 viewpoints, which are sometimes almost identical and sometimes completely divergent. You can almost apply the literary terms of first and third person voice, with the child’s camera as an ‘I’ and the adult’s as a more distanced ‘He/She.’ The technical consistency of the cameras, with their automatic iris and focus, only serves to emphasise the delicate, floating sensibilities of the children, who shift mercurially between different levels of performance for the camera and complete forgetfulness of its presence. As the kids carry the cameras from place to place, the wildly swinging images create a kind of visual imprint of their individual physical presences. As Murphy says: “The process of empowering the children to be the directors in the process that normally records them is an important aspect of the work, especially to make them comfortable in sharing their world.”

While still a student, Murphy made the stunning Prayers of a Mother (1999), a 5 screen piece featuring a woman discussing her life of prayer. The central screen shows her hands holding a cross and rosary. In a voice brimming with longing she talks about her 8 children, her desire that they will all come back to the faith, and the saints she invokes on their behalf. On the surrounding 4 screens, images of her children’s faces, listening intently, fade in and out. The stable central image, flanked by the extraordinary range of emotions and responses recorded on the children’s faces, suggests both an altar and a family tree. This structure economically emphasises the religious and family influences underlying the children’s spontaneous reactions. Prayers of a Mother was acquired by the Australian Centre for the Moving Image in Melbourne, and exhibited in 2003 as part of Remembrance + the Moving Image (RT55, p22).

After graduating, Kate Murphy spent some months living and working in Glasgow, where she befriended Brittaney Love, an 11 year old girl. Their shared fascination with pop star Britney Spears resulted in Britney Love, a solo show held at the Canberra Contemporary Arts Space in 2000. This work comprises floor to ceiling video projection and 6 monitors arranged in a V-shape on the floor, just like a pop video or catwalk. The screens all show the young Brittaney in her lounge room, singing and dancing to a Spears song, radically fusing the private daydream space of early adolescence with that of the public and highly sexualised role model. It’s a slightly uncomfortable fit for the audience, mediated by Brittaney’s voice on the soundtrack talking about her hopes and plans for the future.

Murphy began to experiment with synchronised cameras only recently, influenced in part by the Mike Figgis film Timecode (2000). Joe Hill (2003) was her first work to explore this territory. Video testimony conveys his wish that the song Joe Hill be sung at his funeral, paired with footage from a second camera observing the man alone in the middle of the night, setting up and recording his message.

Anyone working in the documentary genre, which claims to have truth on its side, will inevitably face galvanising ethical and formal dilemmas when it comes to translating raw footage into a final work. For the time being, Kate Murphy plans to continue exploring the potential of multiple cameras to address this issue. Speaking about Joe Hill she comments: “Both (videos) document the same sequence of events. But the subtly different points of observation illustrate the contingency of truth… They also make it clear that the truth presented to the viewer is always one that has been framed for the audience.”

PonySkate shows as part of Interlace, artists Shaun Gladwell, Emil Goh and Kate Murphy; Performance Space, Sydney, May 28-July 3

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 37

© Fiona Trigg; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Sue Healey, Fine Line Terrain, 2003

photo Alejandro Rolandi and Kate Callas

Sue Healey, Fine Line Terrain, 2003

Choreographer Sue Healey is a survivor in the Australian dance scene. Beginning her career with Dance Works (1983-88), Healey led the Canberra-based company Vis-à-Vis from 1993-95. Since then she has choreographed independently, creating works for a fluid company of dancers which has included Michelle Heaven, Philip Adams, Jennifer Newman-Preston, Shona Erskine and Nalina Wait. She has been commissioned by many Australian dance companies and has an ongoing relationship with the Aichi Arts Centre in Japan. Healey has worked with filmmaker Louise Curham (RT58, p15) on several film and installation projects since 1997 and has recently begun directing her own films, including the award-winning Niche (2002) and Fine Line (2003).

Healey is currently a Research Associate with the Unspoken Knowledges Research project, led by Professor Shirley McKechnie at the Victorian College of the Arts. Her recent Niche series has been part of McKechnie’s project and consists of 5 works created between 2002 and 2004: the films mentioned above, 2 live works (Niche/Japan and Fine Line Terrain) and an installation (Niche/Salon). Healey’s finely crafted, intricate choreographies are too rarely presented in Sydney and her upcoming season of Fine Line Terrain at The Studio (Sydney Opera House) has been much anticipated since a showing of the work last year. Since then, the piece has been performed in Auckland, Canberra, Melbourne and New York.

Healey talked to RealTime about the logic behind the Niche series, her interest in space and perception and the challenges she faces as an independent choreographer working with an increasingly consistent company of dancers.

The Niche series covers 5 works and has traversed a number of formats: film, video, installation and performance. Why a series and how is the variety of formats tied to your exploration?

Each work ‘found’ its own niche, so to speak. I started with a dance video focus—wanting to make dance for that specific space rather than my usual method of choreographing the action before its translation into video or film. As our focus was space, it made absolute sense to keep finding new spaces and contexts to explore, manipulate and extend our material, including the screen space, a traditional proscenium space, a white gallery, a new cultural context (Japan) and a ‘site specific’ (30 metre deep) space. I didn’t set out to create a series—it evolved quite organically. I can look back and see that the driving force was a search to place the ‘right’ work in the ‘right’ space.

You are particularly interested in movement and perception. How does this relate to your use of both live and screen formats?