Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Topshop, Berlin

In 2004 Australian artists created cheap multiples for sale under the title NUCA (Network of Uncollectable Artists), their droll ‘salespeople’ appearing with cases at art events around Australia. Adam Jasper reports on a like venture in Berlin, though initially in a shop, but now online. Eds.

There are benefits to a depressed real estate market. Along the northern extension of Berlin’s iconic Friedrichstrasse can be found an array of abandoned shopfronts, derelict warehouses and despondent government buildings. Specialist stores have made way for $2 shops, which in turn have shut their doors and papered over their windows. In their wake, galleries of a diverse nature have colonised the city, taking advantage of the cheap rents and desperate beauty that a decaying urban environment provides.

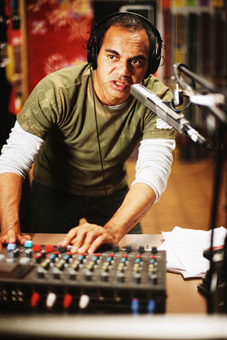

Topshop is a movement set up and run by a group of Berlin artists whose project bears witness to the capriciousness of a marketplace that has alternately indulged and neglected them. For 2 weeks of September last year their flagship locale was one of Friedrichstrasse’s failed dime stores. Modelled on an imaginary supermarket chain, the store was decked out with wire shelves, products helpfully highlighted by ‘Magenta Spot’ specials, 99c bargain tables and special offer corners.

A Topshop is different from an ordinary supermarket in a number of ways. Firstly, instead of tight regulation of prices in line with supply and demand, original work is sold at an arbitrary price by the artist, with the emphasis on the absurdly cheap. Topshop artists tend to produce Fluxus-style multiples–usually small, cheap objects that have been manufactured in limited runs. The way they are sold follows the financial logic of mass produced commodities (pile it high, sell it cheap) but their production shares in the logic of exclusion associated with fine art (the object is the unique work of an artist). Samples and failures, as well as misguided concepts and mistakes, are sold for 99c a piece.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, Topshop encourages the unrestrained copying, appropriation and modification of artists’ work. In the discount area, the exhibiting artists are free to decide which objects they will classify as “material for reproduction”, but any work under that classification can be photocopied by shoppers at machines near the checkout. This cheerful encouragement of brazen piracy is offered as a sort of defence against the assault of industry on the last bastions of avant garde notions of authenticity and originality. Industry appropriates innovations so fast that it is impossible for innovators to keep up. If it’s impossible to be authentic, because being original means owning a pair of Chuck Taylor Originals, then one might as well camouflage one’s self with inauthenticity, with derivative ideas, with objects and concepts so far removed from their origins that they don’t have owners anymore, and consequently can’t be sold.

Many of the pieces enter into an explicit, knowing and mocking dialogue with the notions of value, price and prestige that inform the economics of the art market. Christian Romed-Holthaus, for instance, sold his artworks–small, egg shaped concrete sculptures–by weight, as if they were fruit. His work then becomes not so much the objects as the act of selling art as if it were primary produce.

Another play on the economic relations of supermarkets and their standardising power was made by Inga Zimbrich with her European Day Trip Bar Coder. The barcoder draws on an archive of generic experiences within European cities to generate a completely normal looking EAN–compliant 13 digit barcode recording the events of your day. Within the archive are all the activities, locations, methods of transport and equipment that might feature in a day trip, as well as descriptors, ranging from hectic to placid. An unintended advantage of the bar coder is that any standard bar code also corresponds to a random set of experiences. This means that ordinary consumables gain a set of connotative experiences. Weetbix will always be linked to a maudlin day in a sultry Athens with an umbrella and bicycle. Your day or someone else’s, it barely matters.

One potential criticism of Topshop is its overt inclusiveness. Photos, clothing and pranks make repeated appearances. Catherine Shea’s garishly coloured badges declaiming “Saying It Loud Makes It True” made sense, in that they are designed to be smuggled into stores and left for consumers in a reverse form of shoplifting that both commodifies the artwork and reduces its price to zero. However the contribution of Berlin duo Good and Plenty just seemed a joke, although admittedly one in the Fluxus vein: Genuine Yakuza Slippers, consisting of 2 concrete blocks and a belt. However, as Ulrike Brückner (who along with Sabine Meyer is Topshop’s convener and founding member) pointed out: “The exhibition contained works of vastly differing aspiration. We were initially concerned that this would result in the denigration of some of the more serious works. But it was actually quite the opposite; the result was deeply exciting. To see these works of varying quality next to each other–for instance, a piece of museum-shop giftware next to an artwork with a rigorous conceptual content–had an astonishing effect. The statement of the artwork only became stronger” (my translation).

Chicks On Speed, the art school electroclash band and erstwhile darlings of New Musical Express were also prominently featured in Topshop, perhaps as representatives of the Berlin art scene currently most favoured by the vagaries of commerce. Chicks On Speed sold their new book It’s a Project in conjunction with their new album 99¢ (I couldn’t establish whether this album is named in honour of the Topshop bargain tables). Both book and music are marked by a pronounced DIY aesthetic, as if Chicks On Speed were never meant to be a real band, but a fake approximating a pop sensation better than most real bands. They also feature the only current Australian contribution to Topshop: band member Alex Murray-Leslie.

So is Topshop political art or a trendy prank? Collective vision or agglomeration? Futuristic or retro? Duchamp’s ‘readymades’ of the 1920s (a bottle drier, a urinal, a snow shovel) constituted the most corrosive assault on pre-modern assumptions about art, but paradoxically also embody one of the few art manoeuvres that has never tired. They assert the peculiar right of an artist to simply declare their output art, as if by fiat. It is a strategy that reaches its dialectical endpoint in Manzoni’s 1961 Merda d’artista (the shit of the artist) but has not ceased to resonate as a tactical possibility. But the commodities sold in Topshop are not exactly readymades. As Dieter Daniels (Professor in Art History and Media Theory at the Academy of Visual Arts, Leipzig) observed at the Topshop Panel Discussion:

“The readymade is a mass produced object that has been isolated from its kind. It is released from the masses, taken off the shelf, and set upon the stage as something unique. The multiple…is something produced in high numbers by an artist and could potentially end up in a shop, on a shelf.” (My translation.)

It is therefore in Fluxus that the Topshop movement finds its appropriate historical roots, in the creation and dissemination of ‘limited edition’ artworks that are sold at such low prices they refuse to be identified as artworks, and are instead confused with prank objects, objets d’art, and novelty gifts.

In August a workshop on Topshop will be held at Estonia’s Art Academy of Tallinn. Readers are encouraged to investigate the Topshop concept further and, in line with the official Topshop endorsement of piracy, are welcome to franchise, steal and misuse it.

Topshop, Friedrichstrasse, Berlin, September 16-26, 2004,

www.topshop-berlin.de

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 pg. 42

© Adam Jasper; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

He introduces himself as S* from Baxter IDC. He spends his time in detention with nothing to do but write and write as the days fade by. He wrote his first poem after spending days on Christmas Island mingling with children and families, enjoying seeing the kids going to school. Now in Port Hedland he is separated from their smiles and writes to remember the faces of his sons. He produces a regular newsletter to “unveil all the hidden suffering inside electrocuted fences.”

I introduce myself to S* as a member of PEN, a writers’ group that supports other writers wrongfully imprisoned in jail and in detention. When I begin to write letters I struggle for words, the right tone. Do I tell him what I see through the window on the train winding through the Blue Mountains? Does he want to know about the diversity of cultures, the beauty of landscapes; that there’s more to this place than red dirt, warped heat, hatred and endless languid days behind barbed wire? I start to create my world on a page with a new perspective. I re-create it for him and for me.

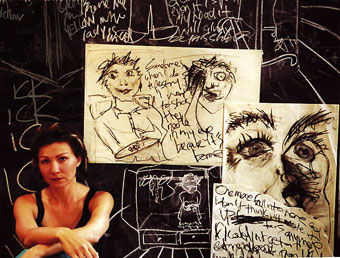

And so our dialogue begins. I send S* a program of the play I saw last night, Through the Wire, which offers accounts of relationships that have slowly developed between Australian women and men in detention seeking asylum. Similar themes are explored in documentaries: Clara Law’s Letters to Ali and Tom Zubrycki’s Molly and Mobarak. The play’s power comes from exploring the dynamics between the Australian women, one of them Jewish, and the men they want to help. The women, who include a psychologist, a guard and a lawyer, become mums, minders, activists, and one a lover, to the men–roles they perform well. A daily voice on the mobile, an unexpected birthday cake on the doorstep. My own voice is echoed in the script as the women negotiate how to communicate, even celebrate, slowly unfolding lives on different sides of the fence.

After its Sydney season, 22 suburban and regional centres lined up to present Through the Wire. However an application put by Performing Lines to the Playing Australia fund of the federal government’s Department of Communications, Information Technology and Arts (DOCITA) was unsuccesful. Surprised but undaunted, writer and director Ros Horin toured the production with Performing Lines and the assistance of the NSW Ministry for the Arts for 4 weeks in NSW and one week in Canberra to near sell-out seasons and standing ovations in most centres. Horin raised funds from many sources (“a kind of people power”, she says) and got the support of the Melbourne Theatre Company, who marketed the play gratis, to present it at the VCA’s Grant Street Theatre where it enjoyed another successful season.

The script of Through the Wire is based on words spoken by asylum seekers. It is theatre stripped back to essentials in both its stagecraft and performative elements. Writer/director Ros Horin has shaped the play over a number of years. She says she works like a sculptor, paring the dialogues back so new details are slowly revealed.

The asylum seekers are played by actors–except for an Iranian actor/playwright Shahin Shafaei who, it is revealed at the end, is one of the authors sharing his lived experience:

It is prison, you know, the detention centre, the whole shape of it…You have no idea how long you are going to be there. There is…no information about what is your status or situation here…at the second day of arrival, there are some people coming along to interview you…who ask you “Why did you come to Australia?” You would tell your story. If you don’t mention that I want to seek asylum in Australia, you will be considered a screen-out, so you are not entitled to seek asylum in Australia because you have never asked…my people smuggler wasn’t that smart to tell me you should say that.

This dynamic between performance and tragic reality reframed my experience of the play. In one of the most harrowing scenes a camera is set up in front of the actors, zeroing in on each face as they describe the circumstances that led to them fleeing their countries and families: smiling at tourists in a hotel, exposing corruption in local courts, writing theatre and performing it illegally, finding friends murdered because they’ve dared to question authority. The men’s voices mingle, rise and fall softly. A close-up of the actor’s face on a large screen above the stage means there is no place to hide and it’s hard work–a dense monologue, haltingly painful, at times beautiful imagery.

The first time I see Through the Wire I am least engaged by Shahin’s performance. This unsettles me for weeks but when I go the second time I realise this man tells his story with the distance and abstraction of a writer/actor through necessity; he can be deported at any time. How can he juggle such emotions and fears day to day in front of an audience, given that writing, acting and watching plays was what led to his being persecuted and fleeing Iran in the first place? Actor Wadih Dona (who plays Farshid) also had to flee his home (Lebanon) during the civil war. I ask him about working with Shahin:

Shahin is still on a Temporary Protection Visa…He has had his final interview as we were on tour and we still don’t know. It is incredible to watch him…but he is playing himself as a character in a director’s vision of who he is in a play that we are performing! The first reading, Shahin couldn’t even finish his story. He got up crying and left the room. It was so moving for me…because that was the first day I met him and I really got it in my heart how important this play is to him. It is not another theatre job, it is about his fucking life.

Wadih and the other actors in Through the Wire are fully aware of the crossover between perceptions of reality and performance in this work. When Wadih originally auditioned, he was in the unusual position of being up against the real Farshid for the role:

He was the real guy so you can imagine how I felt in hindsight. I didn’t actually know that it was him in the room. I though it was some exotic actor that [Ros] had selected to read as well. Later I put it all together when I met him onstage after we did opening night at the Sydney Festival. Shit, that’s Farshid! Oh my god that was the guy from the audition!

All actors were approved after the audition process by the men who had originally spoken/written about their experiences in detention and prison. But Wadih sees no difference between performing a fictional role and his characterisation of Farshid:

Word are words…it does not matter to me what their origin is. I don’t believe in psyching myself up in order to get into a certain emotional state to tell Farshid’s story…it’s like surfing to me. You go on the wave of the story and hope you can ride it to the end! Just commit to the ride and don’t worry where you want to take it.

The strength of a play like Through the Wire is its resilience and continuing topicality, as more is revealed about the government’s lack of mental health care for those in detention, about how up to 200 Australian citizens may have been deported by ‘mistake’, about the harrowing treatment of Cornelia Rau and others like her. The show continues to tour, hitting regional areas and giving asylum seekers a voice. Performing Lines has been instrumental in this. Their programming policy and regional tours encourage and nurture plays that are innovative, unique and of ongoing benefit to performers and audiences. Performing in intimate venues in places like Penrith, Wagga, Albury and Griffith, the actors get to gauge a wide variety of responses, from those who know a lot to those who know a little. A mark of the impact of the play is that audiences sometimes have difficulty differentiating the actors from the characters. Wadih tells the story of a little old lady who approached him after a performance and said tenderly:

‘I really hope you get to stay in Australia’. But the usual reaction from the audience is a profound sense of shame…and they usually ask us what they can do.

Like most in the audience of Through the Wire at Penrith, west of Sydney, I left the theatre angry. But the encounters between the asylum seekers and the women–and between the men and their writing, art, theatre, music–continue to nourish and sustain, inspiring me to write more letters to S*, to be less afraid of giving him glimpses beyond the walls. Only one thing now bothers me. Where are the women’s voices from detention?

Shahin Shafaei’s comments are taken from an interview with Andrew Denton on Enough Rope, www.abc.net.au/tv/enoughrope.

Through the Wire, writer, director, Ros Horin, performers Ali Ammouchi, Wadih Dona, Rhondda Findleton, Katrina Foster, Eloise Oxer, Shahin Shafaei, Hazem Shammas, Jamal Alrekabi; designer Seljuk Feruu, lighting Stephen Hawker, sound Max Lyandvert, music Jamal Alkrekabi, costumes Genevieve Dugard, film Heidi Riederer, Nick Meyers; producer Ros Horin with Performing Lines

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 pg. 28

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

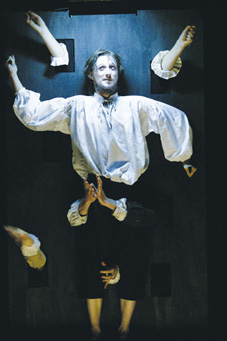

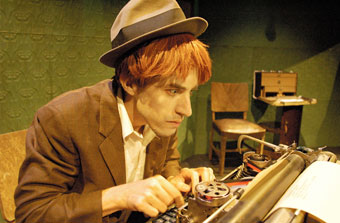

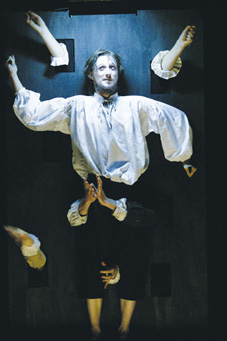

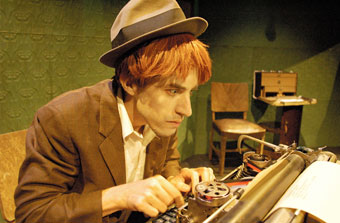

Matthew Whittet, Journal of the Plague Year

photo Lisa Tomasetti

Matthew Whittet, Journal of the Plague Year

Ham Funeral & Journal of the Plague Year

Though Max Gillies’ The Big Con was the official titleholder, it was The Ham Funeral and Journal of the Plague Year which really inaugurated Malthouse Theatre’s first season since its transformation from Playbox. Both shows opened in the same theatre on the same day, featured the same cast and, perhaps most importantly, the same director: Malthouse’s new Artistic Director and very visible face of the overhauled company, Michael Kantor. After the many changes announced since his appointment, this was the opportunity to see precisely what sort of theatre Kantor is committed to producing.

The more striking of the 2 works was Plague Year, written by Tom Wright after the story of the same name by Daniel Defoe. The play is structured as a series of tableaux covering 12 months in the plague-infested London of 1665, and features Robert Menzies as Defoe, guiding us through a society whose external sickness is mirrored by an internal decay. The rest of the ensemble take on multiple roles as denizens of this Dante-esque world.

One of the difficulties posed by the task of adapting Defoe’s tale stems from the original’s status as a kind of mockumentary: billed as journalism, many of the text’s stylistic devices exist almost purely to test the credulity of its reader. An abundance of trivial details, diagrams and first-person reminders of the narrator’s position as a kind of embedded reporter work to bestow an aura of authenticity. Lacking this requirement, however, the staged adaptation struggles to find a reason to include such devices; Wright must not only convert Plague Year to a new medium, but reinvent its generic setting as well. In fact he inverts the original by shifting it into the realm of the fantastic.

In freeing Plague Year from its original meanings, there is the danger that it will not find anchor elsewhere. Though a vague air of allegory permeates the production, it isn’t clear how we are to interpret the significance of events, an especially peculiar fact considering that a fatal pandemic plague has such obvious metaphorical resonance. Contemporary events are occasionally invoked (a passing reference to biological weapons, for example), but these potentially fertile references are rare.

Kantor’s ‘more is more’ approach sees the employment of a bewildering array of theatrical modes: mask, dance, farce, song. There is a sense that the real theme motivating directorial choice is simply the theatre itself as a vehicle for the production of wonder. If this is the case, Plague Year is an unabashed success. However, I find it slightly (though thrillingly) problematic that this production relies on an apocalyptic vision to achieve its effects. Apocalyptic visions can be seductive: lacking the psychological intimacy of tragedy, they instead use impersonal destruction to connote cleansing, starting over, even the possibility of rapture. Certainly, the mounting chaos engulfing Plague Year’s narrator is played out with ecstatic abandon, at one point incarnated as a very literal carnival. Here Kantor and Wright’s earlier work with Barrie Kosky’s Gilgul Theatre is revealed. Kosky has long been an exponent of carnival, grotesquery and excess.

The gleeful, heterogeneous vulgarity of Plague Year is echoed in the excesses of The Ham Funeral, but is moderated by the play’s iconic status as a misunderstood moment of shocking modernism in Australian theatre history. Viewing the work now, one can’t help but measure it against that which came before its controversial 1961 opening in Adelaide. More damagingly, one must compare it to what has appeared since. It’s not an especially challenging work to audiences weaned on absurd irony, black humour and alternatives to realism. It’s still a powerful piece of writing though, with Patrick White’s control of language shining through from the first lines of dialogue. The Ham Funeral is White doing his best Peggy Lee: if that’s all there is, then let’s keep dancing, break out the booze and have a ball. It’s revelry borne of despair, though there are times when this dips dangerously towards undergraduate angst.

An anonymous Young Man (Dan Spielman) moves into a squalid hotel/rooming house run by the basement-bound Mr and Mrs Lusty, a bloated, gluttonous pair. When her husband dies abruptly, Mrs Lusty announces a grand funeral featuring the titular ham, a dramatic absurdity which doesn’t bear quite the same vulgar connotations it may have when White first penned the play in 1947.

The performances are uniformly strong: Dan Spielman brims with confidence in a daunting role, inhabiting the character while retaining its ambiguous status as stand-in for White himself. In contrast, the rest of the ensemble tackle their roles with a vigour verging on the (entirely appropriate) hammy. Julie Forsyth and Ross Williams are the grotesque landlord and lady of the Young Man’s lodgings, and their bawling, belching banter carries most of the piece’s comic weight. Forsyth’s Mrs Lusty is a delirious rendition of the monstrous feminine, the antithesis of the somewhat ridiculously angelic woman upstairs (Lucy Taylor), whose disembodied voice and spectral presence obsesses the Young Man. He finds his libido pulled in contrary directions by carnal Lusty and her lofty, intellectual opposite–the symbolism is laid on with a trowel. The Jungian figuration of these and other characters comes across a little creakily, and this is perhaps the one area in which White’s script has not aged well. At the same time there is a joyous eulogising of outdated theatrical forms. The Young Man asks us “Is this a tragedy, or just 2 fat people arguing in a basement?” The answer to that question, I expect, holds the key to your appreciation of the piece. Both Journal of the Plague Year and The Ham Funeral are actors’ pieces, and it would seem that the new Malthouse is very much an actors’ theatre.

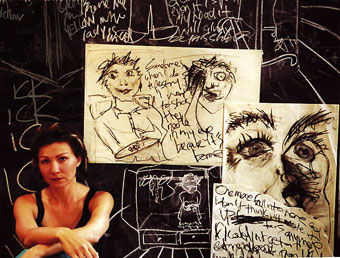

Anita Hegh, The Yellow Wallpaper

photo Peter Evans

Anita Hegh, The Yellow Wallpaper

The Yellow Wallpaper

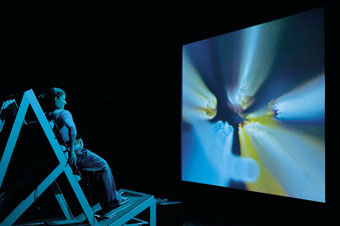

Another work which used a classic text as the launching point for a performance testing the boundaries of theatrical convention was Anita Hegh and Peter Evans’ The Yellow Wallpaper at The Store Room. The slim volume written by Charlotte Perkins Gilman in 1899 offers us a narrator confined to her room for a “rest cure.” We are made witness to her slow descent into madness as the room’s wallpaper begins to take on an hallucinatory life which mocks and mirrors the woman’s own incarceration.

Hegh’s performance is all in this production: a plain set and simple lighting allow us to focus on her hypnotic portrayal of a woman driven to hysteria by patriarchal dictates. If the style of presentation is not overly embellished, neither is it minimalist: Hegh’s monologue is occasionally interrupted by pre-recorded voiceovers continuing the narrative, and at times she dons a pair of sunglasses and grabs a microphone to continue her tale as a spoken word slice of punk protest. The performance is note-perfect, reverent to its source but willing to stray from it, illustrating the power of the performer to reinvest texts with new meanings.

Journal of the Plague Year, writers Tom Wright after Daniel Defoe, director Michael Kantor; performers Julie Forsyth, Dan Spielman, Lucy Taylor, Ross Williams, Robert Menzies, Marta Dusseldorp, Matthew Whittet; The Ham Funeral, writer Patrick White, director Michael Kantor; performers as above; Malthouse Theatre, April 11-May 8

The Yellow Wallpaper, based on the novella by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, director Peter Evans, performer Anita Hegh; The Store Room, Melbourne, March 15-April

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 pg. 29

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Elise May, Brian Lucas, Churchill’s black dog

photo Mark Dyson

Elise May, Brian Lucas, Churchill’s black dog

Beneath his gruff, no-nonsense exterior, Winston Churchill experienced a world of darkness and depression manifested in violent mood swings, emotional doubt and personal insecurities. Churchill called it his “black dog.” In a new work created by Clare Dyson in collaboration with performers Avril Huddy, Brian Lucas, Vanessa Mafe-Keane and Elise May, the dog takes centre stage. Churchill’s black dog is the result of Dyson’s tenure as artist in residence at the Judith Wright Centre of Contemporary Arts, and had its first public showing in Brisbane in April prior to a full production in Canberra later this year.

Churchill’s black dog attempts to choreograph depression and make physical the effect on sufferers’ family and friends. It’s an ambitious aim, but this collective of established Brisbane-based artists, working under the name Subject to Change, has created a strong exploratory piece that slips in and out of historical specificity (ie Churchill’s 1940s) to creatively respond to questions such as: what was the effect of the illness on Churchill’s wife or Virginia Woolf’s husband? Is the black dog a metaphor for conquest or acceptance; familiarity or ownership?

In an unsettlingly silent prologue, the piece opens with 2 naked bodies vulnerable against a brick wall. The stage is littered with autumnal leaves and, in a far corner, there is a bathroom. As a house’s inner sanctum, the bathroom harbours private turmoil and here Huddy silently flails in a bathtub of despair; while at a sink the everyday rituals of cleansing and shaving continue on empty faces.

The dulcet tones of popular 1940s music begin as a man in long johns (Lucas) hunches over a table purposefully reciting the micro tasks involved in the simple act of signing off and posting a letter. The process of naming and listing each action is a survival strategy, a way for this character–could it be Churchill?–to maintain a semblance of control over the present. Later, the table becomes a sanctuary, with the tall man curling into a foetal position beneath it while a voice-over narrates common familial refrains: “I am really worried about you…You can’t just lie there…You need to make more of an effort…You’re pathetic…You’re not trying hard enough…Sad and pathetic.”

Throughout the performance, the torment and anguish of the mind seeks bodily expression. At times, a well-worn physical vocabulary of mental illness is relied upon: anxious twitching, frenzied scratching and butoh-esque muscular strain. All 4 performers follow their own trajectories around the confined space, appearing not to see each other as they play with shadows and sweep up leaves. In theory, this individualised action seems appropriate to the dislocation and isolation of depressive illness, but the longer it is sustained, the more dissipated the energy of the piece becomes. Where are they taking us? Is the historical context meant to clothe each performer in character or are we meant to read this as an everyman/everywoman experience? The ensemble has worked together to create some strikingly original images and text but they are mostly disconnected moments–which is perhaps the intention. For the most part, the audience’s eye is drawn inexorably toward Lucas who best embodies mental turmoil with a startling clarity and fluidity of movement. With him, depression builds as a slow eruption from within.

There is brief respite in a series of delightful knock-knock jokes posed by Lucas as he sits inert facing a door. But the atmosphere soon darkens again as the performers gravitate together in a paranoid calling to the abyss: “Does it matter if you lose your favourite game?…Does it matter if you lose your mind?…Does it matter?” The choreography shifts to convey an angsty and torrid wretchedness. The solo energy that has characterised most of the performance finally becomes collective and, in turn, more forceful and compelling. We are torn from the 1940s as the performers drop and writhe in cold blue light. In time, each finds the fortitude to stand again and, although one woman continues to collapse, the overall image is of strength gained in a momentary togetherness. A sense of hope, perhaps, in the body collective?

Returning to the sepia light and wartime songs, the context turns historical once more. Churchill is in the bath, though he soon disappears. May sits at the table reading aloud from a newspaper: “Dr Genie’s tips for stress-free living.” Lucas reappears pushing the entire bathroom set-piece across the stage and turns it around, away from the public gaze.

We are left with the women, carrying on as usual with a public veneer of competence. Despite internal eruptions of their own, they continue with the laundry, with listing, with ordering, with dressing. Lucas returns to the open door to await the comforting arrival of a cat, but “the dog has come to stay for a while”–and in this performance we have glimpsed its true estranging effect.

Churchill’s black dog, creator Clare Dyson in collaboration with performers Avril Huddy, Brian Lucas, Vanessa Mafe-Keane, Elise May; lighting designer/production manager/photographer Mark Dyson; text advisor Gordon White; music Sia and Sunno; sound Chris Neehause; Judith Wright Centre of Contemporary Arts, Brisbane, May 27-2

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 pg. 30

© Mary Ann Hunter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Opening his solo performance Nothing But Nothing, asylum-seeker Towfiq Al-Qady immediately engages his audience by repeatedly asking “Are you my friend? Can you help me?” The answer is yes, of course, but backed by a giant “NO” constructed on the otherwise bare stage of Brisbane’s Metro Arts Theatre, Towfiq replies: “Really, I want to stay with your yes. I have missed this word for a long time. But between yes and no I have spent all my life.”

With this the dramaturgical framework for the performance is established and, as a newborn audience-community, we bear witness to Al-Qady’s life story: a beleaguered search for ‘yes.’ From childhood dreams and youthful passions to a gruesome ‘choice’ of either becoming a refugee or being executed, we see Al-Qady as an artist and young lover keeping his dreams alive by rejecting everything about a war in which “beautiful things have no meaning.”

Born in Iraq, Towfiq Al-Qady is a painter, cartoonist, actor, writer and director. When he was young, his father, like many other adult men from his region, disappeared without explanation. This had an enormous impact: as Al-Qady explains in his performance, his “dreams were stolen.” When as an adult Al-Qady refused to join the Iraqi army, he was told that he could continue working as an artist only if he painted portraits of Saddam Hussein. Instead, he became a political cartoonist and participated in political theatre, mainly in Syria. Exhausting other avenues to freedom, he emigrated to Australia by boat and was recently held in Curtin Detention Centre for 9 months.

Al-Qady’s depiction of his time at sea is harrowing. Constraining himself within the oval “O” of the onstage “NO”, he plea-bargains with the boat and the sea: “Please, boat, help us…Sea, I like you but I am scared of you.” After enduring the vessel’s motor failure and a life-threatening lack of food and water, he joyfully dances at the long-awaited sight of land. Yet, perhaps as a measure of his graciousness, Al-Qady refrains from lingering on his experience as a detainee in Australia. While in the program notes he describes this period as “very hard” and “not healthy”, in the performance the experience is indicated simply by a short strand of razor wire and a barrage of bureaucratic questioning. Like the off-stage bloodshed of a Greek tragedy, we are left to imagine the pain. In a poignant portrayal of the double-edged ‘compassion’ of Australian authorities, Al-Qady rests his weary cheek against the sharp wire as he plays a waiting game: “Will you say yes? When will you say yes? I should wait? Sorry. OK.”

Currently living in Brisbane on a Temporary Protection Visa, Al-Qady continues to paint and create theatre. He is an active member of Actors for Refugees Queensland, an organisation which has raised awareness of refugees in detention with readings of Michael Gurr’s Something to Declare, devised in collaboration with Actors for Refugees Melbourne using text from detainees’ letters. Nothing But Nothing takes this awareness-raising a step further by creating a unique opportunity for cross-cultural dialogue. Strongly supported by Brisbane’s Iraqi community, Al-Qady’s performance allowed for vibrant post-show discussion with his diverse audience.

Nothing But Nothing lays bare Towfiq Al-Qady’s tortuous journey facing a series of ‘nos.’ Yet this artist’s resilience, passion, and ultimate dream of peace make this performance remarkably optimistic. Nothing But Nothing is infused with Al-Qady’s positive attitude, while refusing to shy away from the immense physical and emotional toll this journey has had: “The war destroyed everything: my life, my love, my heart…My dreams become very small, alone, empty…NO–you are a very small word, but you have a very big impact on my life.” If only this performance was mandatory viewing for Australian politicians, they might finally realise that, in Al-Qady’s words, “I do not make me a refugee. War makes me a refugee.”

Actors for Refugees Qld, Nothing But Nothing, writer/performer Towfiq Al-Qady, musical accompaniment Taj Mahmoud, directorial assistant Leah Mercer, Metro Arts Theatre, Brisbane, May 10-1

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 pg. 30

© Mary Ann Hunter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Katrina Gill, Bridget Dolan, Sam Routledge, Politely Savage

photo Heidrun Löhr

Katrina Gill, Bridget Dolan, Sam Routledge, Politely Savage

The last few months have provided some inspirational performances, not something that can be claimed very often of the always hard work of making art, but when companies of young artists like Sydney’s My Darling Patricia and Melbourne’s Squealing Stuck Pigs Theatre realise haunting visions that thrill with their meticulous crafting and assuredness, the pleasure is palpable, the word is good and faith in the future of performance is restored. Both companies mix their media into a seamless totality–performance as installation, acting, movement, puppetry and film. Add to these the work of Matthew Lutton in Perth (p37), version 1.0 in Sydney (see RT68), Lucy Guerin’s Aether (p14) and the new lease of life for Melbourne theatre in the form of Michael Kantor’s Malthouse (p29), and the sense of possibility, of invention and renewal is pervasive.

Politely Savage

This is a very, very strange experience. We are greeted in the tiny PACT foyer by 3 young women (Halcyon Macleod, Clare Britton, Katrina Gill) all a-flutter like 50s cocktail hostesses in matching full red dresses, high heels and fixed smiles, speedily distributing bland snacks, cheap champagne and snippets of party banter. A nearby crash plunges them quaking into shocked silence, a sudden nervous fragility revealed, a crack in the façade followed by brisk recovery. A no-nonsense housekeeper (Cecily Hardy) arrives, announcing that she will be our guide, and leads us into the PACT performance space to encounter…a house. A very complete 2-storey ruin of a house through which we are led, first down a corridor of tattered wallpaper, splintered timber and embedded signs of life–old postcards, photos and clippings. Our hostess speaks ominously of someone who once lived here, a dry woman in a dry landscape, waiting to be flooded with feeling as much as with rain. She recalls the flooding of the Todd River in Alice Springs every decade, always leaving behind unidentified bodies. Our transformation is well underway, from innocent party guests to guided visitors, to curious confidantes.

We are led into a claustrophobic, dimly lit dusty room where our giddy girls appear in sombre mood to show a film (silhouette puppetry of a child barked at by increasingly monstrous and interchangeable women and dogs) and to act out 2 grim little vignettes with puppets. The first skinny puppet child plays with blocks, throws them away, becomes anxiously aware of us, is strapped to a chair, blind-folded and left, only to make a furtive escape. To the sound of wonderfully mock-Japanese music (toy piano, a high-flying voice) the second child puppet, with its outsize moon-face, is painstakingly, agonisingly coaxed into walking by its red-dressed manipulator, but then cruelly dumped. Dust pours down from the ceiling, instant karma perhaps, over the woman. She remains impassive. Shocked, we are taken upstairs.

We find ourselves on a rooftop looking deep down into the house, into a pool where 3 bodies float face down in water. Our hostesses in petticoats. The frightening vision expands, the walls are mirrors, and we are observed–a girl sits by the pool, lifelike, but, we soon sense, a mute witness, a statue, There are signs of life in the pool, the women slowly emerge and climb the stairs. They pass by like ghosts, treading a narrow bridge over the void to a newly revealed bright field of long grass into which they sink, only to be resurrected on film in their red dresses, movance & dramaturgy Chris Ryan; PACT Youth Theatre, Erskineville, Sydney, April 20-30 ing into the far green distance. As in Noh theatre, we have been entertained and then haunted by the dead–our hosts are ghosts, but have been released from their purgatory of drought and repression (with its child victims) into idyllic pastures.

Now you might not want to reflect too deeply on all of this: it’s iconic gothic Australia–Picnic at Hanging Rock, lost children, The Ghost Wife. The power of Politely Savage comes from its consummate realisation and the idiosyncratic way it deals with these familiar images, making them strange once more. It would be an astonishing achievement for any performance company let alone an emerging one. The performance is considered, carefully shaped and its personae and rhythms meticulously realised and sustained. The 4 young women (Halcyon Macleod, Clare Britton, Bridget Dolan and Katrina Gill) who comprise My Darling Patricia wrote, performed and designed the work, made and operated the puppets (with the assistance of Sam Routledge), built the set and collaborated with a team of artists. A blend of performative styles, puppetry, film and sound, the live-in set for the audience with its alarming changes of perspective, all suggest a confidence in practice and vision. As for the title, it’s just right, Politely Savage, well-mannered gothic–mythic rural darkness beneath suburban veneer.

Christopher Brown, The Black Swan of Trespass

photo Brett Boardman

Christopher Brown, The Black Swan of Trespass

The Black Swan of Trespass

With a like sense of totality, vision and conviction, Melbourne’s Stuck Pigs Squealing Theatre create an intimate and inverted but seductive world, and with Australian iconography again at the core. While My Darling Patricia built a house for us, Stuck Pigs have created a tiny old-fashioned stage world (red curtain, foot lights, pedal organ) for a small audience, using only half the space of Belvoir Street Downstairs. Such intimacy is just right for this fantasia in which writers Chris Kohn and Lally Katz present the creations of the anti-modernist hoaxers of the Ern Malley affair as cartoonishly real: the dying, mechanic poet Ern and his sister Ethel. Their grim, restrained lives and Ern’s bursts of creativity, pain and unrequited sexual desire are framed by the hoaxers’ narrative (Harold Stewart and James McCauley hilarious as a stuffed cat and rooster respectively), period songs from a fine crooner (Gavan O’Leary doubling as Ern’s mosquito antagonist, Anopheles) in a tux and a musician (director Chris Kohn) on organ and guitar. Christopher Brown as Ern is all quivering, junked-up vitality in a performance that is physically virtuosic and which, against the odds of the poetry that pours from him and the ruin that is his life, becomes increasingly real. So too does Ethel (Katie Keady) as she reveals her quiet possessiveness for Ern and her fear of the world. And the poetry makes better sense than its customary rejection as mere parody or the acclaim for its inadvertant modernist achievement by 2 significant poets. Ern’s naivety, his verbal fecundity, his delirium and his desires, the popular songs that haunt him, and a dark Albert Tucker milieu (especially in Princess [Jacklyn Bassaneli] the goddess-whore of Ern’s affections) churn and meld, vomiting up lines from his unconscious that the poet can barely grasp as his own.

The Black Swan of Trespass has enjoyed success in Melbourne (where it returns soon to a Malthouse season), New York (where it picked up a NY Fringe Festival prize and an invitation for the company to return) and now Sydney. Aside from wanting more integrated roles for the singer and musician, I found this an exhilarating work, both in its theatrical inventiveness and its creative response to the Ern Malley story.

The New Breed

The Melbourne based National Institute of Circus Arts made its first visit to Sydney with The New Breed, featuring final year students in a demonstration of individual and collective skills. The show was directed by Brazilian circus artist Rodrigo Matheus with choreography by Carla Candiotto and NICA’s Guang Rong Lu directing the circus routines. Loosely centred on the theme of miscommunication, especially when it comes to love, The New Breed entertained on many levels with a judicious distribution of expert solo routines and duets, verbal and sight gags and sudden surges of collective action keeping the show well-paced and rhythmically engaging. Hoops, stilts, bungy, trapeze and bicycle work kept soloists busy. A worker casually climbs chairs stacked by his mates indifferent to his spectacular balancing. Particular challenges came in the execution of routines while engaged in conversation (a xenophobic paranoid niggles at a slack wire artist) or while being verbally abused (a man balances virtuosically on bricks which are later snatched away by an angry woman). A woman reflects on love while adroitly manoeuvering a giant wheel, herself at its centre.

Some of the best and most confident collective work involved the tall poles distributed across the space. Performers matter-of-factly scaled them, sometimes travelling upside down, or leapt from one to another with simian ease, or kicked each other to the floor in climbing competitions to the strains of a grand waltz. One of the most effective scenes took the shape of a fight between 2 gangs. Tautly choreographed it involved dramatic gesturing and sudden flights through and over a fence, comic moments in which individuals find themselves on the wrong side, and bodies appearing to be magically sucked back through holes in the fence. Other crowd moments, like the repeated pedestrian routine where walkers took on ever stranger animal-like and insect shapes and movements, worked well, but not so the group juggling with clubs, which faltered badly and seemed to breed a wider nervousness early in the show.

The New Breed proved to be a promising advertisement for an important institution. Although unevenly scripted and acted (not all of these performers are going to excell here and nor should they have to), occasionally flawed in skill execution and sometimes too thematically loose, the show kept its audience eager for more and the performers were rightly rewarded with generous applause.

PVI: TTS: Australia, Tour of Duty

The Perth-based PVI new media arts collective focus their gleeful attention on the impact of the Australian government’s response to terrorism–it’s an excuse for an open assault on civil liberties. Despite the sombre mood induced by being lined up for TTS (Terrorist Training School), checked over and checked in at Performance Space prior to boarding the bus on a tour of Sydney’s terrorist target hotspots, the tone soon switches to madcap. We’re sworn in like fascistic Cubs and, once on the bus, we find our leering guide is masked, half-naked and has a severely limited vocabulary. In case of accident we are instructed to “wait until the smoke reaches your chest” and, helpfully, “not to fuck with daddy.” The video entertainment in the tiny bus is a protracted performance art account of interchangeable terrorist/anti-terrorist training replete with brutal body scrubbing, explosives detailing and associated gruesome tales (our host cackles at an incineration story). For the duration of the trip we can’t escape the video. It’s torture, perhaps not PVI’s intention, but a pertinent thematic side-effect. However, we are gratefully distracted, if anxious for, the ‘red man’ in track suit and runners who pursues us across the city, catches up and crouches in a start position for the next leg of the journey. His is a surreal presence as we course through the city.

At Hyde Park, while watching balaclaved tai-chi practitioners and a police car cruising around the fountain, we are told that the park’s fig trees are highly flammable, and we are given our first ‘pop quiz’, which includes guessing what kind of burns you get from battery acid–2nd or 3rd degree? We indicate our answers with the provided card, but our success at getting the answer right is not confirmed, here or in most future tests. It’s that kind of educational trip.

Of the locations we visit, the Opera House is the most memorable on a couple of counts. First, the lights are out, like some war-time blackout; it’s one of those rare nights when no shows are on in the building. From the far side there’s a sudden burst of fireworks from some event or other. Then it’s dark again, Small groups of determined tourists and security guards with dogs look on as we follow the instructions from the headsets we’ve been given, creating a weird collective miming of bomb chucking at the Opera House. We’re not arrested. When we’re parked outside Centrepoint Tower, a passerby traps her heel in the pavement, creating a momentary 2-way diversion between performers and public. Snaps are taken. Beneath Sydney Harbour Bridge we are joined by a host of PVI extras who fling themselves to the ground, as if reacting to an explosion we have not sensed. But unlike the Opera House moment, we’re observers more than participants.

There’s more to this trip, a few more locations, more quizzes, and, at one stage, a tougher (“smiling is not permitted”, “losing is hateful”), sonically-distorted guide who briefly ups the terror tension when he replaces our loopy host who goes off to send our protest postcards to the Telegraph. Looking back on it, TTS was impressive, a logistical and performative challenge involving all kinds of police, council and security negotiations and management of a cast of extras from the Sydney performance scene. There were striking images, like the red man and the initial impression of our tour guide, or the extras dotted across the already dramatic Sydney cityscape, or our own performance beneath the Opera House. Some more moments of heightened participation like this would have been welcome. What disappointed was the sense of a show petering out as we headed to the terminus. Our host seemed lost for words, there were no PVI staffers to receive us at Performance Space, the bar was closed, there was no dialogue, no post-mortem on the terror scenario we’d shared. And whatever happened to the mysterious red man? However, despite the desire from time to time to scream, “Is there a dramaturg on the bus?”, it was a trip worth taking, not least for its mad mocking of the anti-terror regime. The accompanying TTS: Australia Critical Reader, edited by Bec Dean, proved a highly readable bedtime substitute in the absence of a de-briefing.

Tenebrae

The Song Company’s latest Easter celebration is the first part of a projected trilogy, a music theatre creation that merges song with dance as singers and dancers move as one; interpolates the responsories of Gesualdo’s nocturnes for Passion week with Jeremiah’s Lamentations in plainchant; and gradually and ritually extinguishes the light. The audience crowds onto the Sydney Town Hall stage, witnessing voice and movement fill the vast dark space before them. But the core of the performance is intimate and sensual, the performers joining us on stage, their bodies entwining, forming a constant flow of images–sudden non-literal evocations of collapse, the wrack of pain, the lowering from the cross, the laying out of the dead and the pieta. Kate Champion wonderfully and distinctively through-choreographs the performance, ever attentive to the demands on the singers but integrating them seamlessly into it, their brave bodies raised, lowered and embraced; they, in turn, shaping the dancers. The singing is immaculate, refulgent with Gesualdo’s idiosyncratic blend of the chaste and the sensual, and like images are realised in the movement with the fall of hair, a look into the audience, the care that becomes caress. Song Company Easter events are now a significant part of the cultural calendar: the collaboration with Champion’s Force Majeure and the ambition of the trilogy are welcome for believers and atheists alike.

My Darling Patricia, Politely Savage, created by Halcyon Macleod, Clare Britton, Bridget Dolan, Katrina Gill; performer Cecily Hardy, puppeteers Bridget Dolan, Sam Routledge, additional puppet-making Bryony Anderson, lighting Richard Manner, sound Phil Downing, music Marcus Teague, Phil Downing, film Sam James, costumes Jade Simms, Kirsty Stringer, Tanya Aston

Stuck Pigs Squealing Theatre, The Black Swan of Trespass, writers Chris Kohn, Lally Katz, director-composer Chris Kohn, performers Christopher Brown, Katie Keady, Jacklyn Bassanelli, Gavan O’Leary, design Danielle Brustman, sound Jethro Woodward; B Sharp, Belvoir St Theatre Downstairs, April 14-May 1

NICA, The New Breed, The Studio, Sydney Opera House, May 4-15

PVI Collective, TTS: Australia, created by Kelli McCluskey, Steve Bull, Kate Neylon, Chris Williams, James McCluskey, Christina Lee, Jackson Castiglione with Jason Sweeney; Performance Space, Sydney, March 17-27

Song Company & Force Majeure, Tenebrae Trilogy–Part 1, musical director Roland Peelman, artistic director Kate Champion, lighting Sydney Bouhaniche; singers Clive Birch, Richard Black, Tobias Cole, Mark Donnelly, Ruth Kilpatrick, Nicole Thompson, dancers Tom Hodgson, Shaun Parker, Katerine Cogill; Sydney Town Hall, March 28

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 pg. 32

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Thomas Cauker, Passport to Happiness

The third 10 Days on the Island arts festival celebrated the richness of island cultures through a diverse program presented in locations across Tasmania, from Flinders Island to Couta Rocks and Southport. Modelled on a Spiegeltent and made in New Zealand, the Pacific Crystal Palace on Hobart’s Parliament Lawns provided a new focal point for the festival and a venue for world music, cabaret, theatre, forums and a late night lounge. Sue Moss reviews 4 productions from the main festival program.

The Garden of Paradise

Terrapin Puppet Theatre’s production of Hans Christian Anderson’s The Garden of Paradise (1839) is based on the premise of promise. A raked bare stage leads the eye upward to an imagined garden. A prince begins his obsessive search for a mythical garden described by his grandmother. As in all inter-generational tales her story is leavened by partial truths and exaggeration. She warns him not to become mesmerised by the magical flower. His task is to carry a message from the phoenix. If he fails to deliver it the garden of paradise will disappear.

Jason Lam animates his body so that it doubles as dancer and puppet. Lured by his grandmother’s story the young prince walks too deeply into the forest and becomes captivated by the alternately visible and invisible fairy princess (Emee Dillon). Too wilful and brash to grasp the distinction between myth and reality, the prince obsessively follows the fairy princess into the cavern of the 4 winds.

The prince’s journey is told through the magic of silhouette puppetry against a stage-wide diaphanous scrim. Constantine Koukias’s sound score, including a harp played live by Christine Sonneman, evokes an ethereality associated with magic and other-worldliness. This is a subtle production, with director Benjamin Winspear deploying the performers as both stagehands and puppeteers, the ambiguity of roles enhancing the sense of mystery and strangeness. Lam and Dillon’s forest pas de deux is redolent with power, memory and forgetfulness. The garden of paradise sinks into the earth and the prince wakes on top of the tallest tree. After failing to deliver the message he is banished to the mortal world. Another cycle of 100 years begins.

Tempting Providence

Tempting Providence is based on Robert Chafe’s finely crafted biographical script. It is the story of British nurse Myra Grimsley (Deidre Gillard-Rowlings) living in the isolated community of Daniel’s Harbour after signing on for 2 years as the only nurse on the remote coast of Newfoundland, where she remains until her death at 100. Entering this lonely and isolated world, Grimsley practises duty without sentiment, observing “there’s nothing that catches my eye or my peripheral vision.” The nearest doctor is 200 miles to the north. The islanders fear Nurse Grimsley yet need and appreciate her medical skills. She brings efficiency and officiousness to her task of ministering to injuries while assisting in an unusually high number of breech births. Only later does she make the connection between the number of babies being born feet first and women in advanced pregnancy repeatedly leaning over to harvest and lug potatoes before the onset of winter.

As the seasons change so does Nurse Grimsley. While caring for the Daniel’s Harbour community, there are times of loneliness and doubt, a sense of absence and emotion “as still as the grass.” Despite this ambivalence, it is the shared commitment, strength and generosity displayed by 8 men who assist after a saw-logging accident that removes her uncertainty. This mercy dash involves reattaching her brother-in-law’s near-severed foot and trudging 100 kilometres through winter snow to reach the nearest doctor. Nurse Grimsley enters the province of providence and stays. Her story is performed with nuance and precision by Theatre Newfoundland Labrador.

The Island of Slaves

The theme of exile continues in The Island of Slaves, local writer-director Robert Jarman’s adaptation of Pierre Carlet de Marivaux’s 18th century work first performed in 1725. Stories located on islands often involve inversion of existing social hierarchies. From Sophocles to Shakespeare, Robinson Crusoe and Lord of the Flies to the Reality TV of Survivor, this inversion results in the emergence of behaviours characterised by experiment, foibles and violence. De Marivaux commented on the uncertainties that arise when class and social protocol are sufficiently challenged to disturb the optimism of the Age of Reason. This in-the-round production by Tasmania’s Big Monkey Inc places 4 castaways (Brett Rogers, John Xintavelonis, Susan Williams and Noreen Le Mottee) on an island beach. Tutored by an island resident and former slave (Les Winspear), roles and rules are reversed. Each begins to usurp the protocols and behaviours of the master and servant relationship. The result is vengeance, mayhem, farce and ultimate redemption.

Passport to Happiness

Passport to Happiness is the story of Thomas Cauker from Sierra Leone, who fled his home in Bonthe on Sherbro Island to spend 3 years in a refugee camp before arriving in Tasmania. Cauker’s story conveys the reality of a contemporary and terrifying inversion of reason. It is told through video and visual theatre, physical performance, percussion, poetry and narration.

Set in the claustrophobic confines of a shipping container, Cauker tells his story by enacting the joy and ease of life on Sherbro Island. Invasion by rebels and subsequent deaths, family dispersal and existence in a refugee camp dramatically alter his life. Cauker inhabits a world of khaki tents, open pit toilets and frustrating UNHCR bureaucracy. He inscribes his name beside hundreds of others on the metal wall of the container and waits for the processing of his passport and the eventual realisation of his dream. Refugees, he observes, are like shipping containers. They do not know where they will be “dropped down.”

Directed by is theatre’s Ryk Goddard, Passport to Happiness is direct and powerfully engaging. In the opening sequence Cauker offers water as a blessing and a welcome to the narrative of his life. We sip and proceed to witness Thomas Cauker’s journey of tragedy, despair, humour and renewal.

Ten Days on the Island, director Elizabeth Walsh, artistic advisor Robyn Archer, Tasmania, April 1-10

The Garden of Paradise, director/co-writer Benjamin Winspear, artistic advisor/co-writer Scott Rankin, choreography Graeme Murphy, puppetry director/designer Ann Forbes; puppeteers Tim Denton, Kirsty Grierson; dancers Emee Dillon, Jason Lam; Theatre Royal, Hobart, April 1-3; Tempting Providence, writer Robert Chafe, director Jillian Keiley; Playhouse Theatre, Hobart, April 1-5; The Island of Slaves, writer Pierre Carlet de Marivaux, direction/adaptation by Robert Jarman; Hobart Town Hall, April 3-6; Passport to Happiness, performer Thomas Cauker, director Ryk Goddard, Salamanca Square, April 8-10

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 pg. 34

© Sue Moss; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

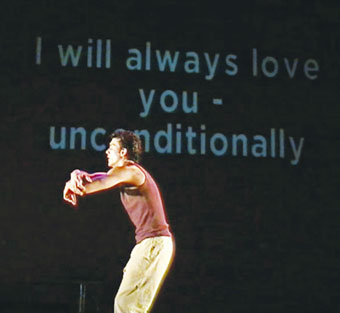

Darcy Grant, This Text Has Legs

photo Natalie Warner

Darcy Grant, This Text Has Legs

Circa’s latest work This Text Has Legs blends contemporary circus, improvisation, music and multimedia. The audience is invited to leave their mobile phones on and their text messages are projected onto a screen and incorporated into the performance. This evokes the rare feeling that what happens on stage is at least partly in your hands.

Fumbling in the dark for your mobile, you break one of theatre’s traditional taboos to be rewarded by the temporary thrill of seeing your tiny private message projected onto the screen for all to see. This level of mild titillation is what initially grabs your attention. You want to know who wrote “2moro i will be reborn as a chicken”, or “CSI Toowoomba cow abduction unit.” There is also the constant question of the degree to which the performers’ actions are responses to the SMS messages.

More than anything, this is a performance that thrives on accumulation. At first it seems like nothing more than a highly skilled Viewpoints exercise, an interesting use of time, space and gesture. Initially this is purely mechanical, as if the audience is watching a warm-up. What becomes clear is that this is also the audience’s warm-up period. The first 20 minutes or so was a texting rehearsal, and as we got better so did the performance.

It’s a show in which the performers’ actions–the usual expertly executed circus tricks (juggling, jumping through hoops, skipping on a unicycle, doing the splits on a tightrope)–are secondary to what the audience does. When the SMS “is the other lady only part time?” appeared on the screen, “the other lady” (Rockie Stone) moved more centrally into the action. Her series of ‘Strong Woman’ stunts prompted another SMS: “I bet she could kick your ass part time.” From this point the to-ing and fro-ing between audience members, and between audience and performers accelerated until after a particularly stunning trick it culminated with the message “part timer you rock my world.”

The set piece was what I’ll call the ‘Patrick Swayze’ episode. It began after a particular trick when the SMS “i saw that in dirty dancing” led to a running gag centred around the movie. How this unfolded demonstrated the possibilities of improvised interaction. Suddenly the soundtrack is Swayze’s She’s Like the Wind, one of the performers is quoting from the movie and an SMS is asking “whatever happened to patrick swayze?” For an audience rarely authorised to exercise their creative muscles, the power of making narrative choices (or not) dawns on them slowly. It only really became clear after the event when, considering all these moments together, a predominately whimsical performance experience now seems more lively and lucid than it did at the time.

It’s both a revolutionary way to enrich the connection between audience and performance and a revolutionary way to order beer, like the smart arse who texted, “may i have another boags please?” And that’s just it; you’re at the mercy of the audience, they can raise or lower the tone, or most likely keep it hovering somewhere in between.

Circa, This Text Has Legs, artistic director Yaron Lifschitz; performers Darcy Grant, Chelsea McGuffin, David Sampford, Rockie Stone; composers Zane Trow, Lawrence English; Judith Wright Centre of Contemporary Arts, Brisbane, March 22-26

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 pg. 35

© Leah Mercer; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

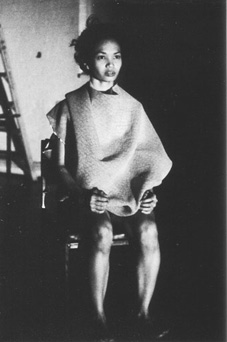

Lone Twin

photo Team Brown

Lone Twin

Sydney-based performer Rosie Dennis appeared at the third National Review of Live Art held in Midland just outside Perth. The parent festival, directed by Nikki Millican is based in Glasgow. Dennis performed her Access All Areas at NRLA in Midland and, on return, kindly met our request to describe the works in the festival that interested her. Eds

The UK’s Bobby Baker opened this year’s National Review of Live Art in Midland with Box Story. For those unfamiliar with Baker’s work she almost always works with food and adopts a housewife persona: Box Story begins with Baker lugging on a huge refrigerator box in very high, very expensive, very uncomfortable electric blue shoes. The box is full of other boxes: a wine cask, washing powder, matches, juice–about 10 in total. Each box comes with a personal anecdote attached, most of them tragic, ranging from the trivial (a failed perm) to the bleak (the death of her father). The contents of the boxes are used to make a map on the floor. The mess she has made comes to represent the world. Individual dark chocolates (from the final box) are thrown amongst the mess to represent the innocent victims of incest, of plane crashes and of wars.

Baker has a cheeky stage presence; she’s got a great smile and wins the audience over within the first few minutes. However, the structure becomes a little tired, especially since all 10 boxes are revealed at the beginning. After only 30 minutes I find myself counting how many remain.

Lone Twin (Gary Winters and Gregg Whelan), also from the UK, have been making work together since 1997, most of it involving walking and some of it dancing. Sledgehammer Songs is a culmination of the stories collected on their travels over the last 4 years. It evokes the mystery of the medicine show, the poetry of pub rock, the loneliness of the European busker, and the drawings of the great and the cursed.

We are invited to stand outside under rain threatening clouds, just as Whelan, dressed in thermals, gloves, hiking boots and layers of polar tech, finishes dancing. He’s been dancing for about 40 minutes, to 21 songs taken from a tape Winters listened to as a child: a guitar practice tape with no lyrics. He’s hot and sweaty. We are each given a cup of water. Cat Stevens’ Wild World blares from the amp and Whelan strips off, inviting us to throw water on his body. He is trying to make a cloud. We watch as condensation rises from his shoulders. Success! From that moment he is known as Gregg The Cloud.

The performance moves inside. We walk the length of the great Midland Hall–about 200 metres–and settle in to watch the 21 stories. Only this time the roles are reversed: Whelan narrates and Winters dances. Winters’ aim is to become Gary The Cloud (at the moment he is Gary The Revolver). During the next 80 minutes there are bull rushes, Bruce Springsteen and tales of lost love. All the while Gary The Revolver dances, adding more layers of clothing and dancing more and more complex choroeography. Finally we are invited outside again; the temperature has dropped and the sky cleared, making way for the clouds that now rise above the shoulders of Gary The Cloud.

Singapore’s Lee Wen has been performing variations of Yellow Man since 1992. We arrive and sit in a semi-circle of chairs. He is already standing in the space. He has objects laid out in anticipation: a paper bag, a plastic shopping bag full of PK chewing gum, local newspapers, a branch and yellow paint. He is quiet and intense. Over an hour Lee Wen moves through each of the objects on a clear trajectory, from punching his fist in the air inside the paper bag, to filling his mouth full of PK–causing him to dry retch–while repeating the mantra: “the state domesticates the artist as soon as the artist calls the state home.” He undresses, revealing an extraordinary body; perhaps the worst scoliosis I have ever seen. This serves to heighten an already politically charged and provocative performance. He uses his shoes as fists and beats himself, one cheek and then the other until his face is dusty and red. The branch is used to whip his tired body. I look around at the audience, people are wiping tears from their eyes. This was a beautiful and deeply moving work; although created 13 years ago many of Wen’s images seem more relevant than ever.

Cat Hope’s Voyeurgers (Australia) is a contemporary investigation of the journey. The work consists of travel footage Hope shot over the last 5 years. Ten distinct journeys are projected onto 10 bare backs to stunning visual effect. Each body sits on top of a 44 gallon stainless steel drum. Each has a voice recorder in their mouth to amplify the sound of wind. The audience moves in and around the bodies, invading the personal and metaphorical spaces of Hope’s travel memories…

Other works presented at NRLA worth mentioning are Grace Surman’s Midland White (UK), a quirky and whimsical take on the assistant, ever ready to serve the non-existent master. She popped toast, crunched apples and chased rubber balls. Bangkok-based Varsha Nair unpacked, stacked and built shapes from her childhood house in in-between-places. Croatian artist Zoran Todorovic gave the audience the opportunity to have their hands washed by 2 Serbian women, using soap made from his own body fat. A photographic installation accompanied this durational performance. Canadian sound artist Alexis O’Hara closed 2 nights of the festival with I Require Electricity. Outfitted as a nurse and plugged into her sampler she attempted to answer our questions–some more successfully than others.

There was a strong line up of Australian artists this year, most of whom had attended the national laboratory Time_Place_Space. A blindfolded Domenico De Clario performed Codependent Arising: bathed in blue light, he played piano from midnight until sunrise. Carolyn Daish offered 2 video installations, caravaggio heart and You Can’t See Me, exploring the play between the projected and real self in space. Kerrin Rowlands invited us to adorn her naked body with objects that included bunny ears, shaving cream, a cap gun and pegs in Rastro (meaning residue or canvas in Spanish). Anne Walton stretched time and lycra, moved ladders and shaped space in her time-based projection installation per:former, assisted by sound from Michelle Outram. Collectively they added texture to a festival that allows artists from the UK, Asia and Australia to exchange ideas about practices and politics, and present provocative new work.

The National Review of Live Art, curators Sharon Flindell, Andrew Beck, Nikki Milican; Block 2, Midland UK; April 8-1

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 pg. 36

© Rosie Dennis; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

For the first time, the hybrid arts research and development laboratory, Time_Place_Space, makes strong regional connections with its choice of visual artists Shigeaki Iwai from Japan and Ahn Pil-Yun from Korea as facilitators, joining open-air performance maestro Threes Anna from the Netherlands and Australian facilitators Derek Kreckler, Elizabeth Drake and Teresa Crea.

Shigeaki Iwai’s recent works deal with communication and multicultural phenomena in cities and rural areas, often involving long-term fieldwork and extensive filming. For Dialogue, Iwai filmed speakers of 58 languages across Europe and Asia between 1996 and 1999. His works incorporate sound, text, video, and installation. He has exhibited internationally and across Japan. He lectures at Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music.

With Korean shamanistic rituals at the centre of her work Ahn Pil-Yun attempts to transcend the social constraints on the artist at the same time engaging with computer technology to explore issues of cultural identity in a globalised world. Threes Anna is a novelist and filmmaker “who creates visual stories based on extreme places and circumstances”, and was artistic director, writer and director of Netherlands’ site-specific theatre company, Dogtroep, from 1989 to 1999. The company’s largely open air performances, drawing huge audiences, have been staged on the remains of the Berlin Wall, at the Winter Olympics in France, in the slums of Uzbekistan and on an artificial lake at the World Expo in Seville.

The artists who are attending T_P_S4 represent a spectrum of practices from physical theatre to sound art: Greg Ackland (SA), Kirsten Bradley (VIC), Sohail Dahdal (NSW), Sam Haren (SA), Noëlle Janaczewska (NSW), Elka Kerkhofs (NT), Jason Lam (NSW), Fiona Malone (NSW), Stephen Noonan (SA), Simone O’Brien (VIC), Abigail Portwin (NSW), Bec Reid (Tas), Sarah Rodigari (VIC), Jodi Rose (NSW), Yana Taylor (NSW), Ingrid Voorendt (VIC), Sarah Waterson (NSW), Tim Webster (VIC). RT

T_P_S4, curators Teresa Crea, Sarah Miller, Fiona Winning; produced by Performance Space; Adelaide Centre for the Arts, July 9-24; www.performancespace.com.au/tps

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 pg. 36

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Michelle Fornasier, The Visit

photo Nigel Etherington

Michelle Fornasier, The Visit

Swiss-German playwright Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s (1921-1990) work has recently entered the English language repertoire, much as George Büchner’s did before him. As a result Dürrenmatt’s place within European dramaturgy has been much debated. He is typically identified as reconciling Bertolt Brecht’s political theatre with the moral-cosmic dramas which Martin Esslin proposed as the basis for his existentialist reading of Absurdist theatre. Under this uneasy alliance, Dürrenmatt’s The Visit is placed alongside Eugène Ionesco’s Rhinoceros, their complex meanings being distilled into a critique of the ease with which the individual submits to social pressures and becomes complicit with fascistic aggression, violence and retribution.

The Visit is certainly a moral allegory. The now fabulously wealthy Claire Zachanassian returns to the debilitated town she was driven from as a pregnant and abandoned youth, with no recourse in law to appeal her unjust expulsion. She offers to give the town a billion marks if they kill her former seducer, Alfred Ill. Despite their initial horror, the townspeople gradually succumb and rationalise their decision. But is this all the play has to tell us? That money corrupts, that poverty speaks, that justice is a sham, that few individuals can resist the tide of communal violence, craving and complicity? This is not a new message, now that, as director Jonathan Miller describes it, the “mixture of excrement and edelweiss” which underwrote Austro-German fascism and its lingering aftermath has been repeatedly identified.

In his production for youth company BSX Theatre, director Matthew Lutton does not reject this interpretation. The climax of the staging is the final town meeting in which the schoolmistress–the last to hold out against Ill’s execution–argues with force for its moral necessity. This differs from Simon Phillips’ 2003 Melbourne Theatre Company version, which climaxed with the last, somewhat reconciliatory visit to the woods by Ill and Zachanassian. Phillips rendered Dürrenmatt’s social satire as a humanist drama of love lost. For Lutton, the piece remains a drama of ideas, a portrayal of (sub)human conversion.

Lutton offers more than just dramaturgical doodlings in the textual margins to realise this on stage. His production is non-realist and highly dynamic. A pair of screens at the back are adorned with blown-up images beamed live from a camera resting inside a sad little grey model of Guellen’s railway station suspended from the ceiling above the action. The lack of colour in the image and the station’s hard, blocky architecture suggest indifference and inevitability. Actors periodically retrieve this object and move it forward, before the camera is finally collared about Ill as he commences his death march.

The stage begins awash with clothing, as though a flood of detritus has clouded the theatrical space, before Zachanassian’s arrival reawakens the populace. Zachanassian brings a coffin with her, which periodically grows along with the townspeople’s complicity. Chairs and tables are moved about by the cast to serve as miniature hierarchical stages.

There are other performative flourishes: a pleasing evolution of colour in costuming and make up and open wings where the actors are seen changing. One could ascribe meanings to these motifs, interpreting the central space as a kind of cabaret of moral decay, but in the end there are too many devices to fully cohere. The train arrives in Guellen as a dazzling floodlight is rolled out from behind the rear screens. It passes back and forth several times before Zachanassian’s silhouette steps through. This is a great image, creatively solving the problem of how to represent the train. However, the exaggerated posing of the cast every time it goes past, like refugees from Gustave Munch’s The Scream, is an ostentation on top of an already established sense of doom.

Lutton is not celebrating a sense of theatrical excess or purposelessness, as Daniel Schlusser did with the carnivalesque exaggeration of his 1999 Melbourne production. There is nevertheless a sense of sheer performative invention spilling over the sides of the moral, political and cosmic meaning implied through the spoken text. By staging so much, Lutton makes the production exceed its stated import, performing for us without leaving us quite sure what is being performed. While this may not be intended, Lutton’s overweening theatrical imagination complicates the play sufficiently to add an engrossing sense of unease regarding the now commonplace and hence banal interpretation usually ascribed to The Visit, cutting through these interpretive traditions to suggest something more arresting.

The Visit, writer Friedrich Dürrenmatt, director Matthew Lutton, BSX-Theatre, Melbourne, May 10-28

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 pg. 37

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Lens Project is an ambitious attempt at delineating the relationship between literature and performance, while ruminating upon the mind of a man who has lived an uneventful life. Leonard Stone, a fictitious Melbourne spectacle maker, is the central character of a real book by Megg Minos. Seven days after the book’s launch, Leonard is the subject of a performance written and directed by Willoh S Weiland.

At the book’s launch, the author sells copies of Lens from piles on a trestle, but this is really Leonard Stone’s show. Objects indicating Leonard’s past are precisely arranged throughout the space. A city made from cardboard, Leonard’s home in miniature, a varnished wooden case containing various types of spectacles, and a delicate piece of lace. As those attending engage in raucous chatter, a woman appears, glides through the audience, sits in a chair and mouths words from a recorded song. Drenched in nostalgia, her voice wafts in and out of earshot: a memory from the life of Leonard Stone. Meanwhile, a technician has set up a microphone stand, only to return and dismantle it a short time later. Like the furtive imagination, Leonard Stone is enigmatic, everywhere and nowhere simultaneously, until I am quietly informed by the technician that Leonard’s life story has just been launched.

In the book, Leonard Stone’s entire life is on display: his birth in a rural town, the death of his father, Leonard and his mother moving to Melbourne, the First and Second World Wars, and the economic opulence of the 1950s. Within these personal and historical episodes further detail is extrapolated: Leonard’s mysterious illness, the family home as convalescence facility for returned servicemen, Leonard attending university, then opening a spectacle business. The 2 constants in Leonard’s life are his ubiquitous mother and his failing sight. In contrast, Leonard is introduced to the spectrum of light, initially by a convalescing painter, and then a university physics lecturer.