Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Hosts: Keith Gallasch and Fiona Winning

Guests: Rosemary Hinde, Martin Thiele, and Harley Stumm Amanda Card (Executive Producer, One Extra Company)

This is an almost complete transcript of the forum: small edits were made where the recording was not clear. For a precis of the transcript, see “Wanted: Creative Producers” in RealTime edition number 69 on this site or in the print edition on page 40.

Keith Gallasch: Introduction

We’re here to discuss creative producers—who they are, what they do and why they’re needed. You could say that all producers are creative (or let’s hope so), that they search out and nurture the creativity of others. But, of course, some producers are more creative than others. I’m thinking of those, in particular, who don’t just pick up an already developed work but who are in there from the beginning with the artists helping to shape, fund and mount the work, sustaining the artists’ vision and even sometimes playing a dramaturgical role. We’re familiar with producers we like to think of as creative—perhaps, say, in the film industry; people like Jan Chapman who has worked with a number of Australian film directors. Or we think of the infamous model of the Hollywood moguls or producers like David O Selznick giving Hitchcock a hard time over the making of Rebecca, interfering every step of the way. And nowadays, again in Hollywood, the accountants who manipulate visions to suit their own ends. These are the people who appropriate the visions of others—hopefully they’re not the subjects of tonight’s discussion.

In the Australian performing arts, our image of the producer is not very clear. It’s a bit like dramaturgy, where everyone involved in a production plays a dramaturgical role to some degree but dramaturgs do it more than anyone else. Similarly, many artists are self-producing and sometimes they get help from various kinds of “producers.” There are agents, for example. Some agents just look after people. But others harness a particular group of artists. There are companies like Strut’n’Fret in Brisbane who put together a whole lot of idiosyncratic, cutting-edge cabaret performers. And you can recognise their very particular brand. There are venues whose programming helps to shape a terrain for artists to work. And occasionally, as with the Sydney Opera House, through Philip Rolfe, Virginia Hyam and The Studio and others will commission work and follow its gestation and development through to the end. Even more importantly is the role these venues play in creating touring networks.

There are also venues that act as incubators. I’m thinking of places like Performance Space who program work in a consistent way, who commission where they can, provide a home, a place where work can develop and be tried out. Performance Space too has its own networks. It’s currently part of a very important one, which will probably come up this evening, called Mobile States. Unfortunately, most venues rarely have the funds to commit to producing in any serious way. Then there’s a touring agency like Performing Lines. It picks up work it thinks it can tour successfully and sometimes the company can be in there from the beginning as a producer with artists and projects it feels it can commit to.

But I think there’s something that a lot of us feel is missing from the arts ecology at the moment and this is a group of independent producers who are not necessarily attached to venues and who are not agents. They’re another species or breed. These people, some of whom are here this evening, rarely have the funds to pursue their vision. Something similar happens in the film industry—we might get Martin Thiele to talk about this—he works both in film and in contemporary performance as a producer. What you get in both artforms is a kind of “bittiness”—people lurching from one project to another, and producers without the funds to achieve any kind of continuity; producers whose capacity to help artists is limited to a project-by-project basis. In the performing arts, the way funding is structured is that most funding is primarily sought by artists who get the grants and then seek help from people they want to assist them who may or may not be producers.

Tonight we’ll have what we hope will be the first of several discussions about strengthening the producer level in the ecology so that as the market gets more and more complex for artists to deal with, there will be people out there to sustain their vision. So tonight we’ll look at a number of models: an executive producer of a dance company, Amanda Card; Rosemary Hinde, a producer who sets up cross-cultural productions and tours them in Asia and Australia; a producer for performance—Martin Thiele, who’s worked with performance company Not Yet It’s Difficult, in Melbourne and is currently working with ABC TV on an arts TV program and who’s also played a role in producing documentary film; and Harley Stumm who’s worked with a different kind of producing model who’ll talk about the Urban Theatre Projects experience. He’s now working with Performing Lines.

I’ll hand over to our 4 guests and ask them what actually drives them as producers, what formed them. Where did it start? Rosemary, perhaps you’d like to kick off.

Rosemary Hinde

My company is called Hirano Productions and I’ve run it for the last 15 years. I do 3 things: I function as an agent. I represent companies with existing productions and tour them within the Asian regions on a tour-by-tour basis. I produce collaborations and co-productions with international partners from Asia—and that’s a big part of my work. Also, where it’s possible, I present, to some extent, Asian companies in Australia—mostly in the areas of dance and physical performance. In my agency work I also represent a lot of outdoor work. So I’m bridging the worlds of popular culture and fine art, I guess, because the reality of the market within Asia for most outdoor performance is that it’s a commercial popular market, particularly in Japan where I work quite a lot.

Within that group of activities and services that we offer, the main area in which I’m a producer is in intercultural projects. I’ve got to say I ‘ve never called myself a creative producer. If there’s anyone creative in my business it’s probably my accountant because I’m still here. That’s the miracle really. I’ve encountered the term in the area of popular entertainment that I work in. So when I work with advertising agencies in Asia or event companies, they have creative producers. What those people do is choose ‘the talent’, the ‘concept.’ They’re responsible for those aspects of the event or the advertisement or the production. I think their role is contrasted to someone like an executive producer or a line producer who deals with contracts, budgets, keeping things on track. Traditionally, I think, in the world of commercial theatre, the role of a producer is to have the final say on both the artistic and financial aspects of a production or an event. And that seems to me to be the characteristic of producing in whatever medium. The producer raises the money and, in commercial theatre, safeguards the interests of the investors. And that’s also the case in commercial film. The role has not primarily been as an advocate for artists. It’s, in a sense, historically been as an advocate for investors.

The artists’ interests, it seems to me, have traditionally been represented and safeguarded by managements and agents. Their role is to represent the artists rather than that being part of the producer’s role. The title ‘producer’ seems to have become quite common in the last 5 years. I notice local governments now have creative producers. City of Melbourne has a creative producer. Ten years ago when you dealt with Australian arts companies, they had general managers and artistic directors. Now they all have executive producers. So, it’s a bit of a terminology thing. It really gets down to what people do.

I’ve worked a little bit with film people and there’s a difference between the role of a producer in the film industry and in the live performance industry. The industries are structured very differently. In film, the companies are on the whole profit-driven. They’re private companies. So the production company for film and television is a normal profit-making company. Live performance is dominated by the not-for-profit structure.

The second key thing is that in film, the copyright is owned by the production company. In live performance, the individual creative artists own the copyright. Probably as a consequence of that, funding in film and TV goes to the producers as the representatives of the copyright. They hire and fire writers, directors, actors, whatever. Live performance doesn’t work that way. The key funding goes to the artists who then, if they choose, engage a producer. So, that’s a structural difference in those industries, which, it seems to me, makes it not very easy to transfer the role of producer from a film and television context to a live performance context.

I think there are many producing models. Deciding on the best model depends on what you’re trying to achieve. Firstly, it’s important to realise that just simply by introducing a producer, you’re not going to solve fundamental problems of lack of audience or lack of money or other resources. Some young artists think that’s going to happen. It’s not. The economic reality of the industry is not going to change simply by introducing a producer. So It doesn’t mean that styles of work that aren’t profitable or don’t get audiences are suddenly going to start getting them because you have a producer.

Traditionally, within a funded and not-for-profit context, funding has been driven through the core unit of the company with its general manager and artistic director or executive producer. Historically, that’s been the basic unit and model of arts funding in Australia. Now, I’m actually not sure that that is any more the most economically productive way of deploying funding because it seems to me—and I work with companies. I tour companies that have exactly those structures—but I think that what you’re effectively doing when you fund things that way is to duplicate roles. Every company has a marketing manager, a finance manager, an operations manager, every core area of operations. I think not all companies need that.

A company that does 2 seasons a year, it seems to me, doesn’t need a marketing manager. But maybe 6 companies who are grouped together with a complementary set of skills, I guess, in the way a festival works with specialist managers who come together and work as a team that service each of those individual companies, might be a better way of looking at it. Performing Lines is definitely one model. Arts Admin in London is also a model that supports companies over time. It has that specialist expertise and it has line managers for each of those companies so that they’re preserved as entities.

I think it’s to do with the structure of the industry rather than a question of creative producers. You can’t look at one in isolation from the other.

Keith Gallasch

And what drives you as an agent/producer?

Rosemary Hinde

I always had a strong international focus. I worked for Melbourne Festival for a time. I started working in the industry when I was in London. I was interested in working internationally and I was specifically interested in Asia.

Keith Gallasch

What about the dance aspect?

Rosemary Hinde

I was a dancer too. So it’s personally driven.

Keith Gallasch

We might move on to Martin who works in both film and theatre domains.

Martin Thiele

I don’t think of myself as being specifically a performing arts producer. I actually started in visual arts, indigenous arts, multicultural arts, community arts, documentary film, media arts, and then performance art. So I think of myself very much as a cross-artform producer.

What drove me to become a producer? It’s actually a monumental moment in my life. I was general manager and working about 70 hours a week in an organization that was kind of in crisis, which is not unusual for small arts organizations. And in fact, I ended up having an industrial dispute with the board of management who were quite disengaged and the weight of the organization I felt was very much on my shoulders. So it was a particular moment in my life. I ended up threatening to take legal action against the board and then actually getting paid out and walking away from that and thinking, that was the most hideous experience of my life.

Seven years later I worked with a much smaller company called Not Yet, It’s Difficult (NYID), which really kept its board at bay and had a philosophy of putting its energy into making art rather than maintaining itself as an organization. I worked out that as an organisational manager, about 85% of my time had gone into maintaining the earlier organization and 15% into creative arts projects. Seven years later, 85% of my energy as a producer went into creating arts projects and 15% effort went into maintaining the organization. Curiously, these were both not-for-profit structures.

Rosemary, one thing you forgot to mention is that in company structures there are often boards of management and, unfortunately … and I’m sure people here are on boards, and I’ve been on boards…they can be full of dickheads, or it can be very hard. Often the people running the company know a hell of a lot more about the history and the artforms than the people on their boards. But because of this historical fact that most arts organizations need to be not-for-profit and need to comply with state regulations, often arts managers can inherit a particular structure that they have to work within.

On the flip side, film production companies are profit-making entities, though I’m still trying to find one that actually has made money! People think that because Vizard made money, everybody does. But actually, they don’t. What is interesting about the film industry is that film projects can become charitable entities in their own right. So a documentary film or a feature can in fact be registered with DOCITA and get 10BA status, which means it becomes a not-for-profit entity. I’ll just mention that and come back to it. I think it’s a really interesting point that a film or an artwork can become a charity.

I think a creative producer provides consensual, logistical compliance, financial and technical support to a project or at least oversees those particular elements of a project. I think in (performing) arts, film and television which are the 3 mediums I’ve worked in over the last 12 months, the producing element is essential. Historically, artists have taken responsibility for self-producing and I think that within the arts support infrastructure there’s still an assumption that artists will take that responsibility. And I think that’s something we need to address because, generally speaking, producers have no status. Independent creative producers have very little status within the arts. Within the film industry it’s acknowledged that such support is core and essential. So a producer is acknowledged alongside a writer and a director and, in terms of the budgeting structuring, is what you call ‘above the line.’ So it’s acknowledged that the role the producer plays is a core part of actually creating an artwork, a film. I think, interestingly, in TV a producer actually can be also the writer and director. So it’s inherently assumed that a producer is creative and has artistic ideas and can kind of manage things, although there are particular structures that people operate in. I think I’ll stop there.

Amanda Card

I came to One Extra after leaving dance. One Extra became what it is now in 1996 partly through necessity and partly through the application of someone for the job who offered the Board a different model from what had been the running model for most contemporary dance companies, which is the artistic director-driven model. Janet Robertson joined the company in 1996 and since then we’ve retained that model. I think they invented the Executive Producer title because (they were) trying to find a model within say film or whatever (with which) they could label this strange beast that became One Extra at the time.

It was also driven partly out of the desires and requirements of the artists who were around at the time. It had been happening for a long time but the small company structure which most of you would know about, well, the bottom had fallen out of it. There wasn’t a lot of support for it. It was also generational. A lot of people were coming out of companies and wanting to create their own work but there wasn’t a model under which they could create those works. A lot of people were trying to create work by themselves, being all those things that they had to be [administrators, publicists, artists].

When I joined One Extra in 2000, I did so because (a) I was looking for a job and (b) I had been trying to find a way in which my past could have an impact on my present. I’d been to university. I’d done all sorts of things like massage and whatever, to see how I could fit back into a system I’d really enjoyed, but I didn’t want to dance any more. It took me 10 or 15 years to find that. When I joined I had absolutely no idea of financial structures and all that sort of stuff. I worked full-time and I had a part-time administrator. What I did have and what I think keeps me at One Extra is that I still really enjoy watching dance performance [and] a group of people for whom this is a life’s ambition. They have to do it. They wouldn’t do it unless they had that burning desire. And most of the time they find themselves in the position where they don’t have enough time to spend in the studio creating the work they want to make because they have to do all these other things—be administrators, marketers, financiers, whatever. One Extra basically tries to provide all those things. And I do have a little bit of a problem in defining what I do in terms of either producing, creative producing, management—a bit like Rosemary. The multiplicity of what is expected of me and what I expect to be able to provide goes beyond just the idea of either finding the money or helping artists find the money to do things. It actually goes towards the early stages of getting work together.

We don’t do much touring. We’re trying to find ways to establish relationships that give the work, once it’s created, a second life. What we mainly do is create relationships. It is creating a sense of location, a sense of connectedness and a collection of relationships these people can have. Most of my time is spent brokering relationships with funding bodies, venues and other organisations. In the dance world here in Sydney it’s places like Performance Space, Critical Path, and The Studio trying to work out how artists can begin their work in the best way possible and then finally make the work that might have another life with any of those organizations. I’ve heard of producers on a film walking in and they don’t like what’s going on and so they get rid of everybody and start again. That’s not something that we would possibly want to do. I see my role as being a conduit for the beginning of the process. I’m trying to make as many relationships for the artists as possible that will allow them to make the work (a) that they want to make and (b) the best work it can be.

I’m not a dramaturg. I have opinions but I don’t walk into the space and say, “I don’t like that. Don’t do that bit.” I might ask questions but that’s also really fluid. It depends on the relationship I have with the artist. As far as I’m concerned, you’re constantly doing whatever you think might work for that particular artist. You don’t tick the boxes on every one. You have to keep moving all the time. Some artists I can talk to about the work that’s being developed. With others I don’t have that relationship with, I try to set up that relationship with someone else. The main thing is developing an environment within which all the best relationships are made in order for the work to be the best it can be. It’s always going to be a gamble.

I was looking at a website about what a creative producer could be. “Lunatic” was one of the things that came up. There was a documentary film site, which included some ideas that might be useful for producers. They’re things like:

Be comfortable with half-developed ideas.

Learn how to stretch organizational regulations.

Try not to dwell on mistakes.

Be a good listener.

Provide lots of feedback

Accept trivial foibles

Defend the artist against attack.

So when you get a bad review or everyone, except a small group of people hates what you do, it’s about having those conversations and saying, well, where do you go from here?

Development work too is one of the best things to be invented in the last ten-fifteen years. Instead of [creating the whole work in] 4 weeks [or] 6 weeks and on it goes, funding bodies are starting to realise that you can develop stuff over time. With the likes of Critical Path we have other places where the development process can go on… (allowing us) to have different conversations about each step of the way. Ultimately, the artist is the one that we’ve identified [to focus on]. We’ve said, okay we’ll give it a go. We’ll call you an artist too and see what you can make. And it might not always be great.

[Being located at] Performance Space has meant that we are no longer on our own either. We used to be at the Seymour Centre and we were a bit isolated and, structurally, a bit out on our own. Coming to Performance Space in 2003 has meant that we can have relationships of our own that we hope will start to develop, a relationship between artists and audience that will stretch over time. So, if you don’t like one work, you might hang around for the next one to see how it went, rather than saying, “Ditch this person. We didn’t like that. We’re not gonna come back for another one.” That constant shifting and moving between relationships, between artists, mentors, money, government is pretty much what we do.

Another thing I do when artists don’t get money is a lot of jumping up and down and carrying on in order to get the money from somewhere else. Also a lot of what One Extra does is stretching out to the relationships we can make with other people, looking at ways that we might be able to make it possible for other companies to have…not replicating, as Rosemary has suggested. One Extra works with anywhere between 6 and 10 artists. Sometimes, I will identify those artists. Other times they’ll come to me. Or there are historical relationships with people that extend over time.

Harley Stumm

In answer to the questions posed, eg, what drives me as a producer, I wrote: “Apart from the obvious things like earning a pay cheque and personal ambition and the desire to conquer the world and all those kind of things, I’d say a desire to influence our public culture, a desire to see the work of really exciting artists (insert your favourites here) to be experienced widely; a desire to make unforgettable performance events. Blah Blah Blah.”

Okay, activist, evangelist and artist, kind of. Which is not the answer that anyone expects. Businessperson is the connotation that usually goes with the title ‘producer.’ And that’s the sort of thing that you have to learn by accident. It’s not what drives you. It’s the means to the end, I guess. I was thinking about this when Rosemary was talking about the model of the commercial film producer who’s the businessperson who goes out to find the artist, to mine the talent. Probably the work we’re all engaged in is more pitching up rather than being a bottom feeder, or all those negative manifestations.

What formed you as a producer? The first event I produced was kind of by accident. I never thought of myself as having produced this event until I came to prepare this paper. The first performance event I caused to happen was in 1984 when I was 20 and worked at a community radio station (4ZZZ) in Brisbane. And for the radiothon market I organised—it’s interesting the other words for this work. There’s a different discourse for each sector or field, often depending on the politics. The whole idea of ‘organising’ obviously connects with political activism. Anyway, I organised the TV-Smashing event of the market in which I sourced 29 defunct television sets and stacked them up in rows 4 high and cut out photos of the baddies of the day—Thatcher and Reagan and Bert Newton and the Channel 9 newsreader and Andrew Peacock and John Howard. We charged people one dollar to hurl half a brick at the TVs. And then after all that—it was an extraordinary event—the punks moved in with long-handled pick axes and reduced everything to rubble. Then I found out it was the producer’s job to take the rubble to the dump.

The next thing I did as a producer—and of course I would never have thought of myself as a producer—I was actually employed by the Communist Party in 1988, to make an intervention into what would happen to the Expo 88 site in Brisbane. We made a submission and had an event with the oral social history of the area involving all the wonderful things that were going to be destroyed, made artworks about it and some fairly lame interactive models to get people into the idea that they could have a role in urban planning. So I think perhaps a lot of people in the arts have come out of this sort of background and we kind of forget it. I think of myself as being socially engaged without thinking of myself as an activist now. But I do think that is a model that we do tend to forget.

I worked in radio for 10 years as a radio producer. Through producing for public radio and for the ABC is very different. I mean, I didn’t know I even had a budget actually. People just showed up and I didn’t even realise they were being paid. But I did documentaries for Radio National and JJJ where I was the program maker, the creator. I also worked as a live radio producer show for Angela Catterns for a year, which I hated. There I wasn’t sure whether I was the brains of the outfit or the tea lady. That’s the radio model.

Then, by accident, I started working in theatre, for Death Defying Theatre, which later became Urban Theatre Projects. That was quite an interesting model. This was around the same time Amanda was describing, around 1996 when One Extra was moving to a producer model. DDT in 1995 had an artistic directorate and no full-time artistic director. And again, I never thought of myself as the producer but found myself running this massive community based hip hop project with workshops in 8 suburbs and 4 artforms and an event at Casula Powerhouse and what is now Bangarra Studios down at the Wharf. I produced a number of site-specific events after that. From 1996, John Baylis came in as artistic co-ordinator, then artistic director and then Alicia Talbot took over a few years later. Obviously they involved very different relationships. But I guess in a way, it never occurred to me that: (a) You never thought of yourself as a producer but (b) I kind of assumed that every manager of a small theatre company had the same intimate relationship with making a piece of theatre that I did.

I gave a talk here a few years ago about producing site-based performance and talked about how essential it was to integrate all the aspects, all the departments—creative and production and marketing and management—in that work. In site-based work, logistics and art are so interwoven in every aspect. I guess in a way, that wasn’t just an observation about site-based work but an articulation of my approach to producing performance. I think a lot of the things that are often seen as ‘dry’ management tasks (budgets, schedules and so on), they’re just a different discourse about the creative process. A budget is a plan for the distribution of resources. So, you can’t do all that work without having a really clear idea of the vision for making that work of art. Is the soundscape a layer at the end or is it completely integral? That’s a small, banal example. To frame a budget, entails asking a series of questions of the artistic director about the intention of the work and how it’s to be made. I don’t see how you can do that effectively without the two feeding back to each other. In the same way, writing an application for funding can often spur the development of the work and contributes to the conceptual development of the work. A media release, when you’re dealing with a devised work that is yet to be made, is the same kind of thing.

The other thing I wanted to say was that it’s really essential to conceive the outcome of this art-making process not as a contained piece of art but as an event that doesn’t meaningfully exist until there’s an audience. The audience are co-conspirators in making the event and then making the meaning. All of that is sort of “Contemporary Cultural Theory 101” I suppose. Often, I think the producer is the only one who has the time or the space or the need to see it that way. That’s the most useful perspective a creative producer can bring to making a piece of work.

I don’t want to talk much about Performing Lines because I’ve really only been there for a few weeks. I could just talk about a couple of projects I’ve worked on since I’ve been there. One is Branch Nebula’s BNP6 and version 1.0’s Wages of Spin and just reflect on how different the role was in each. And this reflects I think the very different work but also the very different structures of the companies and the different skills of the people involved. In a way, you kind of fill the gaps.

Branch Nebula is a devising group without a director. Rightly or wrongly, you kind of feel a bit more compelled to perhaps offer a lot more feedback than would be the case with the other project (welcome or unwelcome, as mostly it is). I see the role there as being an informed audience member and saying, I don’t understand what you’re doing there? What is it? Rather than saying, why don’t you do it this way. So it’s not so much a dramaturgical role but you’re acting as a stand-in for the audience who can’t be present in that making process.

Keith Gallasch

Thanks to all the speakers. I’d like to go back to Rosemary’s opening provocations. Perhaps this might be a starting point for a broader discussion. You suggested that it’s not primarily an issue of creative producers first up but of the structure of the industry—lots of small companies each with their own artistic director and general manager. And then there was Martin’s point about leaving that behind and getting out of that structure.

Rosemary Hinde

I’ve worked for organizations and you spend an enormous amount of time working out your strategy before the board meeting. I don’t have a board. I do whatever I like. I’m totally feral. It gives me a whole lot more time to do the work.

Keith Gallasch

The feral producer, I like that. If there is a fantasy world in which we have a sudden new breed proliferating, a new species—creative producers—and they’re out there, where does the money come from? Is it a matter of re-structuring? Do 6 small companies say, okay we’ll sack our artistic directors and our general managers and we’ll link up in a consortium to share this creative producer. Is that going to work? Even the smallest companies like to be autonomous, drive their own vision.

John Baylis (Director, Theatre Board, Australia Council)

Whether it’s practical or not is perhaps further down the track. Certainly the current model, picking up on what Rosemary said, isn’t probably sustainable—the idea of the little self-contained company with its general manager and artistic director. For a start, a lot of the smaller companies are having trouble even recruiting those staff because there are so many of them out there trying to get the right people. That model arose in the 70s when, if companies wanted to make their own work, they had to create the infrastructure to make it. That case doesn’t pertain now. There are more structures around. You rattled them off before—The Opera House, Performance Space and the like. Things you can tap into. You don’t necessarily need your stand-alone structure. But we’ve inherited that model and it’s rarely been questioned. It’s assumed to be the natural order of things. You aspire to be an artistic director and have your general manager to take all that boring work off your hands and get on with it. It’s cracking.

Fiona Winning

It’s the standstill funding model really.

John Baylis

It is, but … Sorry, just to introduce myself, I’m John Baylis and I’m the Director of the Theatre Board at the Australia Council and we commissioned research into the small to medium theatre companies two years ago which told us what was the problem with our 33 triennially funded organizations. And yes, that exercise was about trying to get more money from government to support them: we can say, yes this model will work, we just need more money. But if you forget about that for a minute and if you were creating things from scratch right now, is that the model you’d go with? I think that’s a question we should be asking.

Rosemary Hinde

I see an enormous amount of resources in things like venues. I think, why don’t venues have to apply with an annual program that includes x amount of Australian work or new work or whatever, and get their funding and do it on that basis? So the management and accountability stuff for the companies gets reduced and the pressure of spending 70 hours a week wondering how you’re going to deal with your board gets taken away. That’s 70 hours a week you can spend on getting the work out there. That gets moved onto a different structure. Some of these problems were created with federalism I think. Arts centres, which lock up an enormous amount of resources, are mostly state funded in a particular way. Partly it’s a problem of Australia being over-governed. It has national, state and local government which all lock up enormous resources and become somehow hard to access, I reckon. They don’t work together.

John Baylis

The last 20 years has seen a huge investment in local government funded performing arts centres both in regional and suburban areas. And yet they’re a parallel structure to the other Australia Council and state government funded kind of producing infrastructure. The two only meet vaguely when invited by Playing Australia or something like that. Yet they represent an enormous resource for artists which everyone turns a blind eye to, including funding bodies like us.

Anne-Louise Rentell

Could I just take that up as a representative of one of those regional performing arts centres. I’m the Performing Arts Facilitator in Wollongong and I’ve been down there for 2 and a half years. This is a position created by the NSW Ministry for the Arts to facilitate professional performing arts in the Illawarra region. It’s been quite an interesting job because you’re in a semi-producer role. You’re seeking out work and helping it happen and providing ways for it to happen, paths of development, that sort of thing. Even though it’s been based at the Illawarra Performing Arts Centre (IPAC), it’s also had an external involvement with the community. We’re now looking at making that position much more embedded within the Centre because it’s one of the performing arts centres that tours work. It tours big companies and whatever. But we felt that the work of the performing arts facilitator can’t go any further without there being a venue for that work to actually develop.

We used to have a regional theatre company called Theatre South, that was made redundant or wound up, about a year and a half ago. So there’s no regional theatre company. So we’re also a venue that’s placed to also be a professional producing company because there is no other company or venue with the capacity that we have. So we have resources from operations managers to technicians to a director who’s been working with a state theatre company, and I bring my own experience. And we’ve got 2 great venues. So we’re sitting there, under-utilised pretty much. We’re touring shows. We have the Merrigong Fringe, our alternative, locally driven—although not entirely—performance opportunity. But what John’s saying is right. We’re now seeing that we’re ripe to actually provide opportunities for development and to produce local work from the ground up. I think it’s a really exciting opportunity.

Martin Thiele

So where do you see the resources coming from to develop this new work that you want to put into your arts centre?

Anne-Louise Rentell

We’re working on that at the moment. We have applications in at the Ministry, one for the role of performing arts facilitator to morph into this new role that will actually look after the development of a theatre program. We’d be looking at things at a grass roots level, incorporating things that are already happening, for example I produce a bi-monthly cabaret down there which is a performance opportunity that’s starting to create work of its own. We’re looking at ways of feeding in. We’re dependent on funding but in terms of how we exist, we’re very well funded by the local council.

Martin Thiele

But does that actually include incubator money for new work?

Anne-Louise Rentell

No, it won’t. It provides resources, the venue, and wages. They don’t fund the artistic content. So we have to seek (funds), if we’re touring stuff, through Playing Australia like everyone else or in terms of projects, through the Ministry for the Arts. But I suppose what I’m saying is it’s an interesting model to contemplate [www.ipac.org.au].

John Baylis

In a way it’s an answer to your question of who will pay for the producer. Well, you could imagine maybe local government will pay for the producer and current specific arts funding, which is now paying for the art making but also for the infrastructure and the general manager to support that, can just go to the art-making. That’s one fantasy future.

Rosemary Hinde

I don’t think that’s entirely fantasy. In a way, the City of Melbourne sort of does that. They have a creative producer [Stephen Richardson] and it has rehearsal venues and performance venues and funds the work to go into them. It’s a fully vertically integrated system really. So it does happen.

Fiona Winning

I suppose there are models outside that. People who work around Performance Space are mostly self-producing, very lean teams of artists or independents making work and I just can’t imagine where they would go in a structure like that.

I’m wondering about another model—-one of my fantasies—that might sit alongside a series of other models such as that. This is of an independent producer with a very lean machine/office. They work with a cluster of artists in quite intense relationships, with those same artists over a number of years to create their vision, whether it be to creatively develop a work, make a new work, to get that on somewhere, to get it toured either nationally or internationally. I suppose this is another model we need because not everybody’s issues are going to be solved by any one model. And it seems to me that that sort of cluster, without the investment in a whole big infrastructure, is is very lean and about relationships. Mostly artists self-produce and mostly do it extremely well but when I see them working with producers, I see it actually enabling the artist to concentrate on making the work rather than worrying about, say, the media release. What producers are able to do in those circumstances is to create relationships at moments when the artist really needs to be in the studio making the work.

Martin Thiele

That’s roughly how I worked last year. I organised a national conference, I produced an interactive artwork with NYID that went to the Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne Festivals. And we worked on a theatre performance called Blowback, an immersive, interactive theatre project. Coincidentally, in the same year, the documentary film I worked on won an AFI Award and the book I’d worked on 2 years before was nominated for an Australian Publishing Award. And curiously, in that year, I earned $26,000 and clocked up 20,000 kilometres on my car and had a $2,000 mobile phone bill and swore I could never work like that again. It was the most successful year of my professional life and I’m still paying off the $10,000 credit card debt as a consequence of having worked like that.

Rosemary Hinde

I’ve got to say that my experience as an independent producer is exactly the same. I had an absolutely bumper year with overseas tours last year but it’s not reflected financially. So for that to work, somehow producers have to be paid because it’s not a commercially viable market. It just isn’t.

Fiona Winning

So it needs subsidy.

Rosemary Hinde

Well, it needs something.

Harley Stumm

That’s why people persist with incorporating and setting up the infrastructure. That’s the way that arts funding covers those costs. Martin and I saw each other a year ago and he said, “So you sold out before I did”, because I’d taken on a salaried job. Really I didn’t give it even 12 months. I mean, I didn’t have any money to invest. How can you call yourself a producer if you don’t have any money? Obviously you’re going to have to invest in a project, apart from giving it your time and enthusiasm and energy. Otherwise it feels like a bit of a fraud really to say that. So then you’re working on a project basis when there’s money available. Or for the things that you really believe in you’re working on ways to advance them as an investment of your own time. But then there’s the effectiveness of working out of an organization, like when you send an email to a festival director from harley@performinglines compared to harley@optusnet, [the difference is] just unbelievable.

Fiona Winning

There’s a UK company called Arts Admin which I think is a fascinating model. Maybe you could talk about that Sophie.

Sophie Travers (Critical Path)

That’s pretty much your dream model. It’s a subsidised entity. I worked with them when I was in the UK. And I think it’s really interesting that the model is held up around the world and in the UK itself and yet it doesn’t exist anywhere else. So even in the UK everyone acknowledges that that is the model but nobody can replicate it. Arts Admin came up through 3 very strong women who started the organization about 15, 20 years ago. They weren’t subsidised and muddled through pretty much like you’re doing, you know, losing money and always on the brink of giving up. Then they broke into being subsidised but they held onto their integrity with the artists and refused to grow as much as they were pushed to do. And it sort of always exists on a knife-edge, even now that they’re world-renowned. It’s the sort of alchemy that nobody can quite pin down.

I think a lot of it is to do with the fact that the critical mass of artists they’re associated with are really good artists. So there’s always more demand out there for those artists….so they’re always on the winning side. They’re never really scrabbling around for a project. They’re also working with enough artists so that if certain artists want to take time off as quite a few do, on a sabbatical or a research project, they’re not having to chase that next bit of income for that artist. The portfolio is really broad and that enables them to sustain over the long period without having to shift their methodology.

Keith Gallasch

How does it actually work?

Sophie Travers

There are two senior producers and there’s one really interesting, shadowy woman who almost nobody knows who’s actually the sort of financial and business genius. I’ve never even met her and I’ve worked very closely with Arts Admin. So she somehow keeps the whole thing afloat. Then the 2 senior producers, who’ve been there from the beginning as the founding members, they have in a sense recruited other younger producers to work with them. And each producer has a range of companies that they’re responsible for. But they also have a different skill set. So every time they introduce somebody new, they bring in different cultural networks or different sponsorships. So they’ve evolved with the times but they’ve kept that one-producer-for-one-group-of-artists. And they really range. Some of them are like an individual who makes one work every 5 years, to companies like DV8. They work across performing arts, visual arts. They pick up projects and put them down again. They got very heavily into science and arts and they didn’t continue with it. They run a bursary scheme. That’s a separate satellite. They were, like everybody, bombarded with people who wanted to be on their client list and they couldn’t deal with them so they set up this bursary scheme where people could access some of their expertise but the company didn’t have to grow to bring in all these new people.

Fiona Winning

I think that’s fantastic because [the funds], as I understand it, are devolved money from Arts Council and other sources. So it becomes this bursary that they can give to emerging and mid-career artists—an amount of money that could be used for R and D or creative development with 10 or 15 artists a year so that those artists always potentially could come onto the books, should someone be taking a sabbatical or someone grow big enough to have their own infrastructure. So there are artists who’ve been with them for years but there are also new people coming in as well. It’s incredibly vibrant.

Sophie Travers

But still, it’s always on the brink of collapse. Always struggling.

Martin Thiele

I was talking before with Fiona about Rising Tide in Melbourne. Angharad Wynne-Jones and Stephen Armstrong and Tanya Farman, a group of far more formidable creative producers than me, and Kristy Edmunds who’s now the director of the Melbourne Festival, actually got together and presumably they tried to create something similar. (This was) an alliance of incredibly well connected international but Australian, and internationally-based producers, but one by one, they’ve all taken jobs. So you have to ask, why didn’t that work? John, what do you think?

John Baylis

Well, Angharad came to see Rosalind Richards (Dance Board) and I to try and find a funding hole for them. The existing funding programs are not very friendly towards that. I think Dance gave them business planning funding.

Rosalind Richards (former Manager, Dance Board, Australia Council)

We gave them an establishment grant of around $15,000.

John Baylis

But beyond that, it’s more or less, you know, we’ll fund the project and you can take your cut. And of course, that’s not a very profitable…. so the funding structure is not set up to deal with that and it’s a great shame.

Fiona Winning

Perhaps this could come out of the Special Initiatives fund, which is now bigger than anything else at the Australia Council from what I can tell, isn’t it?

Russell Dumas (Dance Exchange)

This is also the battle of Artists Services in New York in the early 60s and 70s. And it collapsed because it eventually gets to a point where there’s too much conflict of interest. You devolve money and then there’s all this internal stuff. And they were Trisha Brown, Douglas Dunn and Robert Wilson—quite diverse. It doesn’t work because they all want their own.

Fiona Winning

It worked well for quite a specific arc of time.

Russell Dumas

Yes, but I think that arc of time it works for refers to a much broader sociological thing than saying you can just reproduce this in this time, now. It’s a different time, a different paradigm. It’s like introducing a dinosaur. I think a lot of this producer stuff is doing that too. If you’re actually talking about a structure that has already failed elsewhere. It hasn’t failed here yet but do we need to have to go through it here like we have to do with all the other structures? Do we have to have our own local version of that?

Keith Gallasch

We are at a difficult juncture where the old model is fast running out of steam. A lot of key organizations are facing collapse.

Russell Dumas

But that’s happening everywhere.

Keith Gallasch

It doesn’t matter if it’s happening everywhere, we still have to address it. We were just at a point in the conversation where we were about to say; maybe the time is ripe for a new model. Was that what you were saying, John?

John Baylis

I’ m not suggesting the funding structure is there yet. But certainly I think it’s in the air. Because we’re in a very tight funding situation, the models that I’m grasping at are of using existing infrastructure and inflecting that towards it. And whether that’s the performing arts centres or existing funded entities which are willing to kind of transform into more umbrella…It’s interesting what Sophie just said because in this very room in the 80s, there was a tiny attempt to set up a similar type of umbrella: I was then manager of One Extra Company and I sat in that corner; Christopher Allen was manager of Entr’acte and he sat there; Performance Space sat in that corner. We made the first steps towards setting up an umbrella. What held us back was that our existing companies wouldn’t let us go. You know, you’re my administrator, said One Extra, and so on. So there was that sense, you’re our resource. So it’s getting that transition, where companies are prepared to merge that infrastructure.

Rosemary Hinde

You should start with artists and not companies. We’re not looking at trying to transform companies, which seems to me a really hard job. If you’re looking at it with new artists and new structures…

John Baylis

That’s the other way.

Russell Dumas

So you’re just going to set up another structure. Where are the artists going to come from?

Rosemary Hinde

They’re already there. They’re knocking on the door every day wanting producers. And we can’t afford to take them on.

John Baylis

If the very best artists want to work that way I guess they will attract that structure. Lucy Guerin seems to be one of them. Kate Champion seems to have done that in Sydney.

Harley Stumm

John’s story about the shared infrastructure reminds me of Performance Net which was the experiment in shared management and producing resources between Gravity Feed, Kantanka and Erth. This was Michael Cohen’s baby and then he took the gig up in Newcastle and the 3 companies moved to the Red Box at Lilyfield and then, unfortunately, the Ministry discovered that the sprinklers hadn’t been put in so everyone had to move out. So all these disasters happened on top of the fact that the companies all existed on a sporadic project-by-project basis. But I think that was a really exciting idea about how to share resources.

I worked on this for a while. We had endless planning meetings trying to make it work. But we were always stymied by the building not being finished and things like that. But that’s a kind of model that’s worth thinking about for the future. Three companies coming together and employing a producer/manager to service them all. We were talking about bringing in new people and thinking, well, perhaps we can sell our services at a higher rate to corporate users and this could subsidise the arts companies. Performing Lines has done this a little bit, not so much for corporate users. But it has the ability to charge bigger bucks to the Opera House and the festivals and to subsidise the work in development—for Branch Nebula, Jessica Wilson and so forth. That’s something that this sector should look at doing more because the skills that people are exercising on a daily basis are being paid 10 times the rate in the corporate world. Is there a way to generate some income that can then subsidise the development of contemporary work?

Rosemary Hinde

That’s the way I work a lot of the time.

Simon Wellington (Urban Theatre Projects)

I think this is a really big discussion because there are so many models that work for so many different personalities or companies or groups of artists. I’m interested to understand or talk about where a producer steps in. What’s the compromise between taking risks and producing material that is edifying to a touring circuit or a particular venue or a council to put into their venue?

Amanda Card

Sophie mentioned to me that when she was working with Random Dance Company and thinking about all of the venues as possible locations at which Random might present, she decided to flip it and instead go to the venues and ask: What do you want? What do you present? How do you do your thing? Basically she minimised …

Fiona Winning

Her pitch.

Amanda Card

Yes. She could look at the group and say, that’s where I’ll go. With One Extra, we get to the point where we’ve made a work and only certain works will appeal to say Performing Lines. But that’s a real problem. When you start from this end, from development and making work. Once the work exists, sometimes that’s it. There’s no obvious location where we can go forward. So for us it’s about how to make relationships with a wider group of people where these works might have a location to go to and have another life. Otherwise you’re in a constant cycle which independent artists here will know about, the cycle of making new work all the time.

Simon Wellington

I guess my point is finding that balance between organizations that support the risk-taking, whatever the outcome might be—a one-off season, you know, or 3 years of touring throughout Australia or Europe or Asia or wherever it might go—compared to the companies who may only produce or support the production of the work that will have a definite outcome, where they can see the ingredients there that they can sell on to specific venues or their network of relationships. So it’s finding that balance, I guess, rather than there’s this model, or who’s determining the work.

Amanda Card

It depends on the artist. If an artist wants to present at The Opera House, then we need to find out together, One Extra and the artist, what makes a work possible for the Opera House. And if the artist then makes the choice to make the work reflect that, then it’s up to them. I often use the analogy of the visual artist. The first work the artist makes might be the work they want to make. Then someone comes in and says, “I really like that piece but I’d like it in purple to go with my couch.” The artist is in a position to say well, give me $20,000 to do that.

Fiona Winning

Or not.

Amanda Card

Or not. So there are artists who want to make finite work and then drop it and start the next 3 or 4-year project. There are others who’d like to see their work move around.

Fiona Winning

You’re right, Simon. There’s a multiplicity of models. There’s also a range of work that is of its moment that must be made which is for an audience of 6 or a research and development project, which nobody might see, which relies on other outcomes.

Simon Wellington

You need the flexibility to have the support and the resources there to respond to something that’s happening right there and then rather than waiting till—you know, “We don’t make decisions until February 2006” or something.

Russell Dumas

The consequence is you reduce… Like in Europe all the different festivals. You go to Monpelier, different dance festivals around France and Germany and it’s the same producers who are making decisions about what survives and what doesn’t. In a real way, they become the ones who are determining what is produced.

Fiona Winning

Who’s determining it now?

Russell Dumas

Oh, a whole bunch of them and they keep going. It’s the same in America.

Fiona Winning

No, I mean here.

Russell Dumas

I don’t think there is enough mass here to actually to talk about that. In the extreme you can see things like that. I think it’s difficult in Australia because there are so many mitigating circumstances. We’re actually a mish-mash of models that always came from elsewhere. And we can’t really contextualise. And the people making the decisions are making them with bits of information. Simply, things like the terms we use. If you start to problematise the relationship between dance, dancer, choreographer and say, we use these terms as if we know what they mean without actually their historical production. Sally Gardiner talks a lot about affective and effective relationships—the conditions under which a work is made. So for a choreographer she talks about relationships between the choreographer and the dancers they’re working with. Well, if you’re in a pick-up situation, which is the model, we have in the Australian Ballet, we’ve taken this one model and we’ve reproduced it like fungus across the country. It is the only model we have.

I think we started off talking about why people incorporate. And it’s because the legal requirement to get money is that you actually have to have a board of directors who are responsible because, as we all know, artists aren’t responsible.

Keith Gallasch

Simon has brought up this matter of risk. What role does risk play in Hirano, Rosemary?

Rosemary Hinde

It varies a bit. I accept that to get anywhere you have to make an initial investment because to market a show and to set up, just looking at the touring side of it, I won’t take on anything that’s will give me any less than 2 years—because you can’t do anything in terms of developing the strategy and building those relationships for those particular artists and companies. You’re not earning money while you’re doing that. You’re investing in the work. So, I have to believe that at the end of it, it’s going to be worth doing. It does effect what I think I can take on. It’s my house on the line, basically.

John Baylis

If you were to be subsidised, what form would that ideally take, you know, not just money in a brown paper envelope. But what strings would you accept, what would you find intolerable?

Rosemary Hinde

That’s a difficult question, John. I’d have to think about it. I’ve worked independently for nearly 14 years now. Obviously within that time I get money for projects and particular tours and stuff like that. But there is a trade-off that doesn’t necessarily occur in film, does it Martin? Film producers don’t have to make that trade-off.

Martin Thiele

How do you mean?

Rosemary Hinde

In terms of setting up those sort of companies. Producers can be funded directly without having to have the levels of government accountability that….

Martin Thiele

They have legal infrastructure. It’s quite complicated in terms of assignment of risk. Curiously, in terms of that producer support, both the AFC and also Film Victoria have actually been exploring the idea of producer subsidy or business grants to producers, often with quite substantial interest rate returns (10% in the case of Film Victoria), on the assumption that when you get a film financed, a percentage of the production will actually be returned. So, for example, in the case of Big and Little Films, the production company I was working with, we had a digital feature film that was commissioned by SBS. So about $5,000 of that would have gone into repaying a $30,000 producer’s investment. But I actually suspect that given film production has been stalling, at this stage, people have taken on that return responsibility without necessarily getting the capacity. A lot of really experienced film producers are out of work and have been for a number of years. In some respects, I think there are some interesting structural things in film production, but the state of the film industry is that it’s in crisis.

There are still interesting lessons in that model. One of the good things about film production is that they’ve got great systematized structures. Your A-Z budget and your cost reporting structure. At some stage, the AFC thought, okay can we absolutely systematize the process of the business behind the making of film? And they have. So you can get your Producers Pack from the AFC for $150, which will give you all the necessary compliance information including a funding structure. I think that’s really quite useful in terms of refining and standardising the way people might work for stuff that can be systematized. Obviously, not everything can. But a lot of the compliance and financial structures can be. It’s certainly worth considering. Every time I’ve produced something, I’ve had to invent a system to go with it.

Rosemary Hinde

The other thing, in answer to the question, is that when I set up Hirano, I did it because I couldn’t see any other way of doing it. There weren’t organizations that had job labels that said: “You can develop touring markets in Asia and intercultural co-productions.” There weren’t any. That’s why I did it.

Fiona Winning

When we were looking at the list of people to ask to speak at this forum, there weren’t actually independent producers operating like you two have been—Marguerite Pepper wanted to attend but is away.

Rosemary Hinde

It’s the same in Melbourne. Companies die all the time because it’s hard.

Martin Thiele

It’s not just performing arts. I worked a lot last year with [new media artist] Lynette Walworth, trying to put together an interactive project and we would just have endless meetings. In the end it was impossible to put together a deal to support an interactive film project with a budget of $50,000 with an artist of her stature. And David Pledger will say he still hasn’t worked out how to tour work between Australian cities. It’s much easier to tour overseas.

There are lots of structural problems and the bittiness of the bureaucratic structure. And I’m not going to hold the Australia Council completely responsible. It’s impossible. You go to ACMI and they talk about commissioning a $50,000 project with a $6,000 investment. It’s completely out of whack. The costs of making new and innovative work are just not being acknowledged. And so a lot of people, who would love to be making the innovative work in Australia, are giving up, taking academic jobs, taking paid work or heading overseas. And that’s not a new thing in this country. It’s been happening for years. But in terms of innovative work that’s made in new ways, there just isn’t that many ways to make it.

Russell Dumas

But there isn’t support for what is being made. So, to actually set up another bureaucratic…

Martin Thiele

Well, there is some support. The festivals initiative, the MFI is one way that some artists have been able to get commissions for new work.

Russell Dumas

But, again, it’s funnelling through a particular group of people who actually decide what survives and what doesn’t. And they’re not artists. And you can’t make work without resources.

Rosemary Hinde

I wouldn’t call them producers. Festivals aren’t producers. They’re presenters. They hire producers to put together what they want. And I do think there’s a problem with the presentational culture in Australia. I think there’s an incredible risk-aversion.

Russell Dumas

But it’s often the same people. They just do the shuffle. After they’ve done one festival, they just move on to the next one. So it’s actually coming down to a very small group of people who are making all the decisions about what survives.

Rosemary Hinde

Of course.

Russell Dumas

That’s the thing that I think is dangerous. And I don’t think it’s going to be solved by putting in another level of bureaucracy.

John Baylis

I don’t think it is. It’s actually quite the opposite. It’s actually about trying to devolve money from the bureaucracies to people who have more flexibility and can cut corners and don’t have the same accountability structures that big bureaucracies do. If there was a network of independent producers whom we could devolve a lot of what is our New Work money to, and trust them to choose the artists, and work with them to take the work, I’m sure they can get more value out of that money than we can, going through our transparent processes.

Russell Dumas

Don’t you think it will be more parochial?

John Baylis

Parochial?

Russell Dumas

You devolve it far enough and it’ll just eventually….

Audience member

I like the out-of-town model. “It wowed them in Wollongong.” Are we brave enough to go that way?

Keith Gallasch

There was a model of devolution which everyone was afraid of in the 80s which suggested that you gave the money to large companies to look after the little ones or you gave it to state governments. But I don’t think we’re talking about that kind of devolution. I think we’re talking about a different group of people with perhaps a national overview who are interested in works touring, like the Mobile States initiative. And I think that’s quite a different model of devolution. The money goes to the small to medium sector and these producers work with the people they’re interested in. The Australia Council has become this kind of grant processing machine and this would change some of that to a degree.

Amanda Card

(If One Extra doesn’t suit the artist’s) requirements, they’re not going to want to work with One Extra. They can take themselves elsewhere or do it on their own. It’s not imposed. Of course, sometimes, especially for a commercial producer, there are a whole lot of ways you have to think. But the funding bodies will find out very quickly if nobody wants to work with a particular producer. And so in a way, the responsibility for, or the imposition of choice is not always from the producer’s end. It’s often from the artist’s end. And sometimes, of course, it’s made in a very unfriendly environment. So obviously, everybody’s going to be going, where can I find someone to help me do this stuff? But if you’re not doing it to their satisfaction…

Keith Gallasch

And it doesn’t have to be a total model either, does it? It’s just another element.

Amanda Card

And the moving in and out of those associations—it’s important that people can do that. Like the model you were talking about in the UK. It’s not always something that you have to be grafted to. What you find with a number of the company models—I can only talk about dance, I don’t know what it’s like in theatre—but often what happens is this incredible pressure to keep producing work year after year, means that sometimes you just want to stop and go away and come back. I know that for some that pressure is also great. It’s not always advisable that it should be maintained over long periods of time.

Simon Wellington

Isn’t the Australia Council getting better at that idea of companies taking breaks, going into development, having longer genesis periods for new work? These seem to have become more acceptable over the past few years?

Keith Gallasch

Fiona and I are aware that we’ve all been talking for an hour and a half, so we should start to wind up. This has been a very interesting conversation and we’re hoping that it will be part of a continuing one. It is interesting to see if we are on the cusp of something else—another model. I’m just not quite sure whether it’s already in process with things like Mobile States. Or if we think it’s worth fighting for, what are the next stages of pushing this, because I think it’s really important. Funding for the arts is not increasing. Apparently, according to Australia Council Chair Gonski, we can look forward to a boom in private philanthrop—-people dropping dead and leaving $16 million to the Conservatorium of Music …[LAUGHTER]… but not to the rest of us. Different models need to evolve so that we have improved access and networks right across Australia that artists can participate in. So we’re ready to wrap up now. But if anyone has anything to add…

Simon Wellington

Just one thing. All of the models we’ve talked about are interesting. But also if we’re talking about producers…just from my experience in a company, the leverage that you get out of that large amount of money that you get-and sure, at the end of the day, only a relatively small amount of it might go into the creative process after you’ve paid for the administration-but what that can leverage at a grass roots level in terms of alternative sources of funding is a really interesting thing that we might face in changing models. It’s something that has to be confronted. How do you maintain those links? That’s really important.

Harley Stumm

Yep, I agree with that. Particularly in terms of the philanthropic and private sponsorship stuff, it’s very hard to get those people to give money to a relatively faceless organization like Performing Lines compared to a pitch to your local community such as “Hi, we’re this Western Sydney company…” You’ve got to weigh up the cost benefit analysis I guess. But it must be thought through.

Keith Gallasch

Thanks to our guests from both Melbourne and Sydney. Thanks to you all for coming. Please have a drink and keep the dialogue going.

Clare Langan, Too Dark for Night

Within an hour of landing at Tullamarine I can usually be found, like a faithful pilgrim, descending the staircase of ACMI’s screening gallery in the hope of losing myself in selections of the best in contemporary screen-based art. The latest offering World Without End, is definitely an exhibition where the viewer is asked to surrender to an unknown journey. Inspired by Godard’s dictum “It is not necessary to create a world, but the possibility of a world” (catalogue essay) curators Alexie Glass and Alessio Cavallaro have selected Australian and international works which play with scale and time, exploring vastness through compression, fetishising the detail in the epic, and challenging the sense of self in an infinite universe.

In the entrance stairway is the Pleix Collective’s Netlag (France)—a tessellated map of the world made up of footage from over 1600 web cameras across the globe. We pan and zoom in on sections of the map to glimpse quotidian activities as captured by the anonymous cameras. The banality of detail provides this world view with a bland universality, heightened by the generic electro beat of the soundscape.

Susan Norrie’s Enola (Australia) also plays with scale but focuses more on the compression of the constructed world. Filmed at the Tobu World Square theme park, the camera slowly circles the wonders of the world in quarter size—the Eiffel Tower plonked next to the Vatican, nestled near airports with aimlessly circling planes. Strangely the muzak soundtrack adds to the suggested silence of the place, in which the only living figures are 2 hooded observers, peering in wonder at these creations. This world is too clean, too ordered, too observed, too quiet…we have built ourselves out of existence.

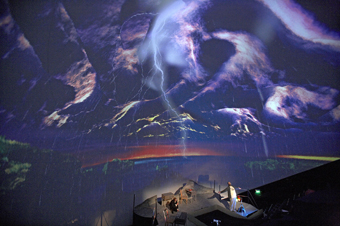

From this quiet, constructed world we enter the bombastic audiovisual symphony of Simon Carroll and Martin Friedel’s History of a Day (Australia). Here the viewer is surrounded by cascading images of a day in progress from sunrise to sunset. In the intervening 4 minutes we experience earth, air, water and fire—soaring across seas and deserts, plunging into volcanoes and industrial zones, riding tempests and cloud gusts. The footage is stunning, playing in cannon across the 5 screens, accompanied by a near operatic soundscape. The pace and virtuosity of the piece is certainly impressive even if the grandeur overrides the possibility for deeper contemplative resonances.

Matching the visual scale of History of a Day, is Daniel Crook’s Train No 1 (Australia). Shown several times over the last few years, this is the most impressive presentation of this work, spanning half the wall of the main gallery, utilising 3 projectors. Using his TimeSlice technique, the vision is staggered and interwoven extending the visual material—in this case a train—into seemingly infinite dimensions. Each sliver of image has its own character and charged essences which in combination create a shimmering mirage of everyday experience.

Deftly placed opposite Train No 1 is the most subtle but beguiling of the works in World Without End—Ross Cooper and Jussi Ängeslevä’s The Last Clock (UK). Concentric circles are formed by the rotation of clock hands—hour, minute, second. The circles are heavily textured with tawny smears, each with a different density. The accompanying notes tell us that these are the product of the sweep of the hands of a clock across live video images from a camera placed upstairs on Federation Square. Knowing this and discovering figures appearing and being wiped away—moments held and then obliterated over 3 different timeframes—lends the piece an ephemeral, poetic quality, a ‘liveness’. However, it is a knowledge well hidden unless you read the notes. Perhaps there is a way in which this work could be presented in relation to the source of the video material, so that the cause and effect could be more easily discovered.

It is this same ‘liveness’, the physicality of Lynette Walworth’s Hold: Vessel 1 (Australia) which makes it such an appealing work. A gentle interactive experience, the visitor holds a finely crafted translucent glass bowl in order to catch the projection—underwater creatures of quivering cilia, wispy tendrils and exotic colours are manifest in your hands, accompanied by an intricately textured soundscore. Placed in its own viewing room, the work still weaves its magic 4 years after its initial inception.

Scattered through the exhibition are Robert Cahen’s Cartes Postale: Video Melting Pot (France). Starting with touristic stills, these scenes have but a brief moment to come to life, before being frozen again in time. There is a satisfying haiku element to these works—revealing layers below the cliche. My favourite is the idyllic view of an Icelandic town which, when unfrozen, shows an aeroplane soaring across the skyscape.

A jarring inclusion is A Viagem (The Voyage) by Christian Boustani (Portugal). Commissioned by the Portuguese government for Expo ‘98 it depicts the 1543 Portuguese expedition to Japan. It is a finely crafted and visually impressive film of collaged action and 2 and 3D animation inspired by Japanese gilded panels. However, there is a self-conscious trickiness and triteness that makes it sit uncomfortably within the contemplative framework of the other exhibits. Its cute and beatsy soundtrack completely drowned out the unearthly calm of Darren Almond’s (UK) A, a meditative exploration of Antartica.

Moving from the white ice of Antartica into the sweltering vastness of the Namibian Desert, Clare Langan’s Too Dark for Night (Ireland) is an apt culmination for this journey to the end of the world. A lone figure walks with calm purpose across the massive wind-sculpted sand dunes. The cinematography is astounding, and Langan’s use of handmade filters subtly protects the viewer from being swamped by the image. The figure searches for signs of other humans, finds only ruins and continues the search, a cycle as inevitable as the entropy of the shifting landscape. This is quietly devastating.

Seoungho Cho’s Rev (South Korea) and Brian Doyle’s The Light (US), were the least engaging works in the exhibition. Positioned next to the exit escalator, Doyle’s quietly contemplative studies of light (lights) are both visually and aurally overwhelmed by Cho’s hyperactive portrait of urban living—a collage of wildly spinning cameras, a revolving door and a candle flame. This section also marks the centre of the gallery space, so not only did Cho’s sound overwhelm Doyle’s work, but all the sound from the works seemed to coalesce into a cacophony of thunderclaps, train noises and clashing tones. In fact, soundbleed was an issue for all the works not accorded their own viewing rooms. Although considerable effort was made to place speakers directionally so that visitors sitting on the viewing couches could discern elements of each audioscape, several works dominated the entire aural space. This is an ongoing problem in screen-based exhibitions, and while many seem to accept the inevitability of it, the compromised audio element of this audiovisual medium should not be underestimated.

Even though the placement of works is seriously problematic for the sound, it is the fact that the works rub up against each other—each piece sharing some element of the works placed near it creating sympathetic resonances—that makes World Without End such an enjoyable exhibition providing many possible pathways to explore and possible worlds in which to lose yourself.

World Without End, curators Alexie Glass and Alessio Cavallaro, Australian Centre for the Moving Image, April 14-July 17

RealTime issue #68 Aug-Sept 2005 pg. 38

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Junebum Park, 1 Parking 2001-2002, DVD

Mirror Worlds—Contemporary Video From Asia reflects, often humorously, sometimes surreally, on globalised culture and its consumerist economy that both fuels unbridled change and provokes violent reactions.

Junebum Park’s 3 videos are typical of the exhibition’s tone. 1 Parking (South Korea, 2001-02) offers a bird’s-eye view of a car park where an enormous pair of hands hover over the scene, moving the cars about and pushing pedestrians along when they threaten the traffic flow. The impression of a controlling force guiding the city is enhanced by the projection of the image onto the gallery floor, placing the viewer in the position of the giant ordering the rapid fire activity below. In 15 Excavator (2003), the same oversized hands operate an earth moving machine on a building site, while The Advertisement (2004) sees them nimbly plastering advertising signs across an office block’s naked facade. The fast motion in all 3 works lends a comic edge to the unsettling representation of the myriad powers ruling life in the modern metropolis, with the hands evoking everything from the surveillance of traffic controllers to the more abstract ‘hand of the market’.