Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Dan’s eloquent reading captures the vividness and thematic cogency of his review of director John Hillcoat and writer Nick Cave’s feature film The Proposition (2005), a seeming Western that tests white Australian myths.

Read the text:

RealTime issue #70 Dec-Jan 2005

–

Image credit: Guy Pearce, The Proposition

The OnScreen New Media Art Course Guide is available as a PDF (76kb)

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 27,

© ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

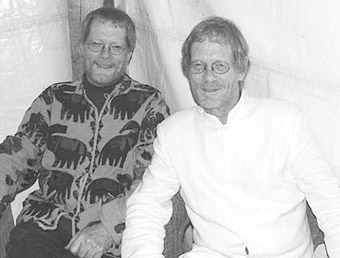

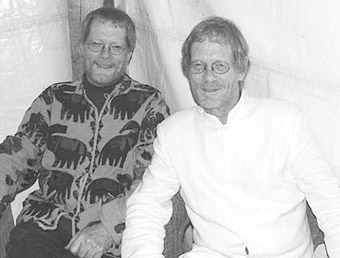

Mike Stubbs

Mike Stubbs

I interviewed Mike Stubbs the day before RMIT’s Vital Signs, a 2-day conference on new media art that brought together several hundred artists, theorists, curators and writers from around the country to discuss the standing of the field and the key issues of practice, distribution, reviewing and curation (see RT 70 for a detailed report). It’s appropriate for Vital Signs to be held at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image; it’s one of the hubs of Australia’s new media art scene and, internationally, a unique, specialised home for the latest in art practice. Stubbs is Head of the Exhibitions Unit at ACMI.

Trained at Cardiff Art College and the Royal College of Art, Stubbs was the founding director of Hull Time Based Arts (1985-2000) and developed EMARE (European Media Arts Residency Exchange). He co-founded Metamedia, a Soho-based production company specializing in art and music. As a producer he commissioned the award-winning media performance POL by Granular Synthesis featured at the 2001 Venice Biennale, and curated new media programs for the Kiev International Media Art Festival in the Ukraine and the Microwave Festival in Hong Kong. He also established strong collaborative links with European art organisations through establishing the Hull Time Based Arts’ Root Festival.

Stubbs’ commissioned films Donut (2001) and Resistor (2001) were broadcast on BBC 2 and Channel 4 Television; many of his films have won awards; and a retrospective of his video work was shown at the Tate Gallery, London. In 2001, he completed Zero, a short film made in zero gravity on board a Russian military aircraft at the Yuri Gagarin Training Centre. He has also created large scale outdoor projections and streamed works.

Curator and maker

After art school, Stubbs worked with film and then video. He recalls his first show, curated in a temporary cinema space in a supermarket in Cardiff city centre in 1980, was called Not just another art show. As for the difference between making work and curating, he says he has “never been able to separate the two. It’s the sense of working with materials, whether 16mm film or computer digits or expertly ironing shirts (my mother), or arranging the work of other artists; you take pleasure in the craft, the duty of curation, the ability to question, whether creating work or programming or curating. Of course they are different but the underlying principles are the same.”

Stubbs came to Melbourne from Hull via Scotland where he was a Senior Research Fellow at Dundee University. He refers to the experience as “a recovery period [from his 13 years at Hull Time Based Arts] when I actually got to make a body of new work which was, in a sense, critiquing agendas of social economic cultural regeneration which I’d become aware of through my work in Hull. My most significant collaborations have been with social scientists, health care, psychiatrists and scientists, not because they’re better than artists but they challenge your assumptions.”

Two cities

Stubbs describes Hull’s decline from being a highly industrial, masculine culture: “It lost its fishing industry which provided 80% of its employment and had the lowest education attendance figures and the highest rate of teenage pregnancies in the UK. Talent drained to the south. Here was a city that wanted to be part of the information age. It was strategically important for Time Based Art to be in a dysfunctional part of East England in terms of government funding. I was young, I represented techno-music and clubs, and I was up against ageing male councillors, the city fathers. It led to a sense of independence—Time Based Arts became the primary promoter of live and new media art in Britain. I don’t think we really tried to meet their measures of social regeneration but they turned a big-enough of a blind eye to what we were doing to continue to fund us, because enough people in positions of power supported us because we were developing an international reputation, which gave Hull something like having a premier league football club. I was working through the network I’d got from my filmmaking, capitalising on trips to film festivals and then establishing good solid working relationships. We had very strong connections with Holland and Germany, Hong Kong, the Ukraine…”

For Stubbs, Melbourne was very attractive: “a liveable city, security good, good for raising children, images of a relaxed environment, sun etc, but, ironically, it turns out Australians work harder and longer than anyone else.” ACMI is “an amazing site, challenging expectations for people about what they see and where. It has one of the best screen galleries in the world. And there are some great artists working in Australia.” He’s also taken with Australian culture: “Australia has masses of potential, it’s highly distinctive in terms of its history, the mix of migration. It can connect internationally but also with its Indigenous population. Christian Thompson is an intern here, it’s a small thing, but it is important.”

Curating history

Curation and programming are historically significant. Stubbs describes his work as the Head of the Exhibitions Unit and that of his fellow curator, Alessio Cavallaro, as “taking snapshots of particular practices at particular times, and in a way that’s artistic. I’m not a cultural theorist but historically you can see who’s been able to dictate ‘history’, impart versions of the world, for various reasons.”

He is alert to how a curator has to read the signs: “people want to manufacture movements because it’s convenient, because it post-rationalises theory—and Australia is full of theorists. In the early 1990s, he says, the scratch video movement was “romanticised as underground, uneducated garage culture, which didn’t really exist; it was students.” Similarly, being alert to what’s happening around the world is vital: “You have to take on multiple sources of information. I’m always interested to know what great art artists are seeing, otherwise you end up with biennale shopping, which is justified in terms of Australia’s isolation, but risks it being subjugated to a homogenised culture.”

Stubbs describes the unit as “a small team doing 3 or 4 exhibitions a year, but they’re big exhibitions. ACMI is over its start-up period, there’s a new director, Tony Sweeney, with a sustainable model for the institution. Exhibitions had been pretty much specialised media shows, but recently have become more variable in texture and curatorial brief. From here on they’ll be intermixed with shows like the Stanley Kubrick exhibition; a collaboration with the National Gallery of Victoria; something on the history of Australian television [in its 50th year]; and experimental film from Germany; and an emphasis on building audiences.”

White Noise

The current show, the Stubbs-curated White Noise, is a seriously entertaining exhibition of curated and commissioned abstract works in new media, a nice contrast to Experimenta’s equally engrossing Vanishing Point with its more representational animations and interactives. Both shows will be reviewed in RT 70 (December-January).

White Noise is not primarily interactive, but it can be intensely immersive, and that includes the exquisite installation design—a dark corridor with glowing blue frames receding into the distance, each the entrance to a visually and sonically discrete and often powerful work.

Stubbs recalls that as a young filmmaker, “I used to reject abstraction. I was always more interested in the representational than the non-representational. I had that need…but I came to know a lot about abstract filmmaking and loads about new media art. My tutors at the Royal College of Arts were eminent materialist and abstract film makers, Peter Gidal and Malcom le Grice.” Stubbs enjoys the beauty of much of the work in White Noise and is impressed by the artists each having a strong philosophical base.

The show also represents continuity for Stubbs: “There are artists in this exhibition I’ve worked with over a long period of time, more as a producer. I have confidence in them, a close working relationship, and I want to see where they’re going next. And I want to encourage that, provide the opportunity for them to make masterworks. I don’t know how many shots I’ll have to do this here, in a great gallery, with a great body of artists, with a show highly focused in terms of architecture and engineering, at every level. The balance in White Noise between having the right slate of artists, a significant thesis and a great audience offer is a dream scenario.”

White Noise, curator Mike Stubbs, ACMI, Aug 18-Oct 23, www.acmi.net.au

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 26

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

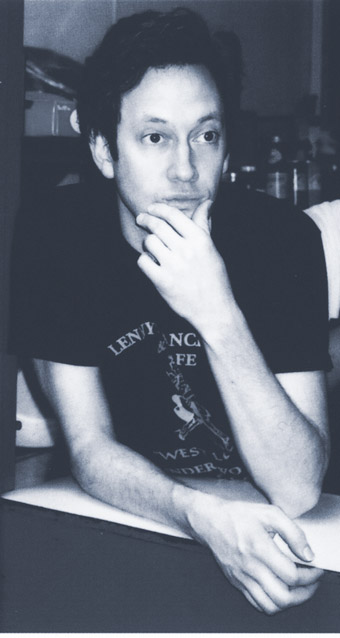

Wooster Group, House/Lights

Wooster Group, House/Lights

In investigating fundamentals of performance, Peter Brook, Richard Foreman and Elizabeth LeCompte have maintained their reputations as theatre innovators over long careers.

Peter Brook, at 80 years old and with a 60-year career, is the oldest and most venerated of them all, the most influential director in the world. His The Empty Space is theatre gospel. Historic productions include Marat/Sade, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, King Lear, Conference of the Birds and The Mahabharata. Though he has made a vast and varied contribution to the theatre, he is most frequently associated with a cross-cultural quest to discover universals in human performance. His interpretations of Shakespeare combine psychological insight, incandescent intelligence and a sublime imagination.

Richard Foreman has been making theatre for 37 of his 67 years. Early in the development of his Ontological-Hysteric Theatre, founded in 1968, Foreman’s interest in phenomenology produced a theatre that isolated objects and moments, concentrating focus and stretching time. Performers emotionlessly going through movements to the sound of flat voices over the loudspeakers, buzzers sounding within and between speeches, and ludicrous intrusions into stage action were among devices promoting Brechtian distance. Over time, the interruptions and non sequiturs became increasingly strong aspects of his work as he focused on realising his own trains of thought on stage. Most recently, Foreman has used theatre to consider aspects of contemporary culture.

Elizabeth LeCompte’s Wooster Group came about in 1980, growing out of Richard Schechner’s Performing Group, founded in 1967. The associative construction of performances, the alienating devices, the director’s meticulous control of all action, light and sound on stage have much in common with Foreman’s work. The collisions of texts drawn from high and low culture, classic texts and material drawn from improvisation, and juxtapositions of live performance and technology characterise the Wooster Group’s more recent work. Director Peter Sellars has described the work as “high-energy, show-biz media-blitzed theatrical grandslam.”

Peter Brook

Peter Brook and his company presented Tierno Bokar at Columbia University where Brook was an artist-in-residence. (How difficult it is to imagine an Australian university having the resources or the will to pursue such a residency!) Set in 1930s Mali, the play tells the true story of an Islamic mystic who demonstrates the courage of his convictions when he refuses to change his religious practice to fit the dictates of a more powerful sect. As a result, he is rejected by his fellows and left to die alone.

Tierno Bokar recalls another portrait of steadfastness, Robert Bolt’s depiction of Thomas More in A Man for all Seasons, but while Bolt’s More had more than a touch of ego, the holy man in Brook’s production is all gentleness and humility. He says on several occasions, ‘’There are three truths; my truth, your truth and the truth.”

The floor of Barnard College’s gym appears covered in dust for the show. There is an exquisite and characteristic minimalism to staging and gesture. Sticks suggest struggling trees. Two musicians at the side of the area provide wind and percussion for the action. Everything is essential and maximally expressive.

There is no rushing, either. Tierno Bokar is not so much the telling of a story as the staging of a quality; peaceful humility. The meditative pace takes at least some of the audience into a zone in which there are quite different relationships to time and space than the ones we are accustomed to in the West, especially in a city such as New York. At the end of the performance I saw, there was a very, very long silence before tumultuous applause began.

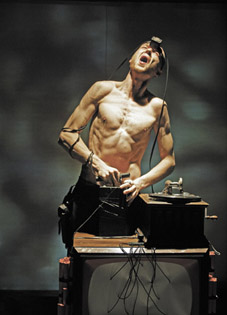

Richard Foreman

Richard Foreman’s The Gods Are Pounding My Head (AKA Lumberjack Messiah) is an endgame in at least 2 senses. Before it opened, Foreman announced his retirement from the theatre he has been making for over 3 decades. The Gods is also an elegy for a culture slipping from sight, leaving the sort of wasteland described by Beckett and Eliot.

The set is vintage Foreman. A steam engine protrudes from a wall. Golden planets with Roman letters around their equators hover among medieval chandeliers with doves hanging from them. The stark utility of industrial chutes is balanced by a whimsical playground slide. Valve arteries protrude from a giant, heart-like planet. Biblical tablets are blank. There are the trademark crossed wires and transparent shields, in case we forget about the 4th wall and whose show this is. Inhabiting the set is a chorus in Ottoman pantaloons, German helmets (complete with cross) and 60s sunglasses. The Exodus, changes to the conception of the universe, the Crusades, the Industrial Revolution and 60s youth culture are among the cultural disruptions thus evoked. Rationality/science and intuition/religion are also in the mix, as are ignorance, innocence and experience.

The director’s note in the programme reveals the reason for the myriad cultural associations. In it Foreman alleges the passing of “the highly educated and articulate personality—a man or woman who carried inside themselves a personally constructed and unique version of the entire heritage of the West” and “the replacement of complex inner density with a new kind of self—evolving under the pressure of information overload and the technology of the ‘instantly available’”, he describes this “new self” as needing “to contain less and less of an inner repertory of dense cultural inheritance—as we all become ‘pancake people’—spread wide and thin as we connect with that vast network of information accessed by the mere press of a button.” He speculates whether this will “produce a new kind of enlightenment or ‘super-consciousness’”, professing himself sometimes optimistic and sometimes shrinking “back in horror at a world that seems to have lost the thick and multi-textured density of deeply evolved personality.”

There is much here in common with Eliot’s regrets about modernity and, indeed, the 2 bewildered lumberjacks at the centre of the piece are hollow men for whom, ignorant of its cultural riches, their environment is a wasteland. Far from being destructive figures, they are incapable of using their axes. For them, “Between the conception/ And the creation/ Between the emotion/ And the response/ Falls the Shadow” of something like ennui or exhaustion.

At the end of the play, mushrooms sprout as characters drink a ‘magic elixir’ that might be a regenerative liquid, like the wine symbolising the blood of Christ or a suicidal potion. The clang of falling cups as the lights fade suggests the latter and confirms the aptness of Foreman’s description of The Gods as an “elegiac” product of “anguish.”

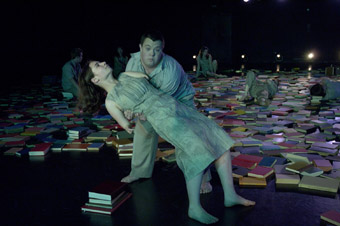

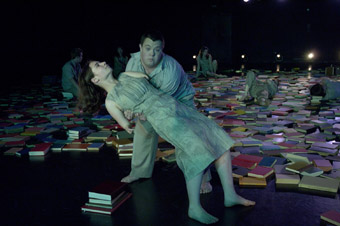

Elizabeth LeCompte & The Wooster Group

While Foreman’s piece is unusually dour for him, the Wooster Group’s House/Lights, first performed in 1998, is especially zany. The show juxtaposes two texts linked by their treatment of power and pursuit, “Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights”, a 1938 libretto by Gertrude Stein, and Olga’s House of Shame, a 1964 B-grade lesbian crime thriller.

In its use of technology in performance, House/Lights has much in common with other recent Wooster work such as The Hairy Ape that came to the Melbourne Festival. Not only are there bells and whistles but clanging platforms, cameras, TVs, headsets, voice manipulations and interminglings of live and recorded action, pop culture and high culture. There is a joyous playfulness to House/Lights. It provides frenetic fun for the audience and its techno-business is impressive. But ultimately it is rather shallow along lines suggested by Foreman. With sufficient cultural background and a lot more motivation, his lumberjacks might have made this show.

* * *

Considered together, these 3 remarkable theatremakers present an array of pleasures missing from most theatre currently on offer. But it is sobering to recall that these productions have occurred during the drab and dangerous Bush era. Seen in this light, Brook’s poetics, Foreman’s erudite elegy and LeCompte’s wizzbangery may well amount to fiddling in the flames.

CICT,Tierno Bokar, director Peter Brook, Le Frak gymnasium, Barnard College, Columbia University, March-April 26; Ontological Hysteric Theater, The Gods Are Pounding My Head (AKA Lumberjack Messiah), writer-director Richard Foreman, St Mark’s Church, Jan 18-April 17; Wooster Group, House/Lights, director Elizabeth LeCompte, St. Ann’s Warehouse, Feb 2-April 10

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 32

© Donald Pulford; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Chelsea McGuffin, Darcy Grant, David Carberry, The Space Between

photo Justin Nicholas

Chelsea McGuffin, Darcy Grant, David Carberry, The Space Between

From the moment of being directed to Circa’s studio rather than the main performance space at the Judith Wright Centre, The Space Between is something out of the ordinary. With the audience placed up against the 4 walls in a single row of seats facing a rectangular mat in the centre of the room, the space is bare, except for a single trapeze hanging in the centre. This sparse beginning is a kind of empty canvas that we will watch paint itself.

Lit only from above and sometimes assisted by projections, the mat becomes textured with shadows that create shapes, or inversely, spaces in which the performers place themselves. In the light and in between, the performers are confined and defined. This recurring attention to space is in keeping with the production’s exploration “into the things that keep us apart and our desire to be together”.

These lighting states also ensure that this is a piece about bodies rather than faces and when these bodies (performers Chelsea McGuffin, Darcy Grant and David Carberry) enter and take their place there is an impassive quality, an effortlessness that is neatly contradicted by the moment they engage and the performance begins. The passion and effort builds in an accumulation of moments, of stunning solo dexterity, beautiful duets and gorgeous ensemble work. This is a work of momentum and of images tumbling one after the other. The moving bodies, the riffing physical images and the constant, changing patterns of light on the floor create rich impressions.

The integrated soundtrack ranges from Jacques Brel songs to industrial sounds. When it describes “walking and falling at the same time” we seem to have lost track of which way is up and which way is down as the performers defy our logical understanding of what bodies can do. When McGuffin is lifted up to the trapeze, the vertical dimension of the space—right there in front of us the whole time—seems to open up. And that’s one of the many qualities of this work, what it creates out of thin air. McGuffin’s work on the trapeze is stunning, an exquisite, crash mat-free, heart-stopping duet, performer melding with apparatus.

The other two performers are equally compelling. Carberry has the flexibility of a rag doll coupled with amazing feats of strength, while Grant brings a mix of grace and danger. The only false note came in the stories told by McGuffin and Grant. Without the flair or seamlessness intrinsic in every other element of the production, the texts seemed oddly out of place.

This is a brave work, a simple performance that is strikingly complex, without tricks and yet full of them. Resting on the skills and presence of its 3 performers, The Space Between gives them no room to hide, nor do they need it.

Circa Rock’n’Roll Circus Ensemble, The Space Between, director Yaron Lifschitz, Judith Wright Centre, Brisbane, Aug 17-Sept 3

See more on Circa in An Axis of Edges, p8

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 34

© Leah Mercer; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Fiona Macleod, Todd MacDonald, Construction of the Human Heart

Enter ‘Him’ and ‘Her.’ They sit in a nondescript, aqua green set, reading from scripts, actors playing roles in a show at The Storeroom, Melbourne. Yet each carries a pencil and uses it to make alterations. Actors yes, but actors playing writers who have written a play, joking and laughing about the vain silliness of the theatre. A self reflective dig at a scenario all too familiar…Yet ‘Him’ and ‘Her’, and the oceanic set they are immersed within also hint at an interior space—the masculine and feminine sides of playwright Ross Mueller. Two sides of one personality walking a line between melodramatic realism (a child has died), expressionism, and a self-reflective preoccupation with not just the writing process, but the process of creating a play. The passage from reading to rehearsal through to the public performance of private lives grieving over the loss of a child. Is it the playwright’s ‘baby’ that has gone to the grave? An intimate piece of writing Mueller has offered up for scrutiny to an arbitrary audience ? Or is it a ‘real’ child who has died? Does it really matter?

The human heart is a labyrinth of interconnecting chambers, at its most palpable when dissected in the theatre. Overlay the glib and distant recorded voice of a character who may be a representation of the surface mind of the playwright masquerading as a TV boothman, and Mueller’s play is complete. The omnipotent playwright, aware of his absurd situation, and the absurdity of his creation, delineates the contours of a ‘heart’ that can only be made apparent by a strange contradiction—a distant view of intimate space. One eye is on the story being told, another on the effect of the story as it unfolds on the writer’s emotions. Or perhaps this is just a play about the loss of a child and its effect upon 2 ordinary people? What is this dream we call the theatre and what of the theatremakers whom playwrights ask to interpret their dreams?

Director Brett Adam skilfully teases out the manifold concerns of a difficult script while Todd MacDonald and Fiona Macleod provide the emotional crunch that made Construction… a go-see show, one that entertains yet also challenges its audience by suggesting its melodrama is just another device within a play, within a play, within a play…Such is the oblique resonance of a work well constructed within Construction of the Human Heart.

Construction of the Human Heart, writer Ross Mueller, director Brett Adam, performers Todd MacDonald, Fiona Macleod, lighting design Rob Irwin, set design Luke Pither; The Storeroom, Melbourne, Aug 2-21

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 34

© Tony Reck; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

You know the set up. The party’s over and it’s time to leave. If you don’t, things may get ugly. Instead, you stay on, trying to recapture the spirit of an event as it diminishes. One too many pills, a bottle or 2 of vodka, and the party just gets uglier…

The End of Romance has something of this ugliness. A pudgy, bearded Jason Sweeney in white singlet and Y-fronts disco dances with balloons. Vampish Julie Vulcan repeatedly stabs a heart shaped chocolate cake with a knife, stuffs cake into her mouth, and later offers it to members of the audience (many choosing to eat the mess). The End of Romance might be muddled, self indulgent and excessive, but what of that moment when a relationship fails—that transitional space, that haemorrhaging of a fruitful, satisfying partnership in our capacity to abandon those we love? This is the space that The End of Romance inhabits, but it is not just a show about personal relationships. Sweeney runs around the space with a framed map of ‘Old Australia’, singing an ironic song that reinforces “Howard’s Way”—back to the 50s while charting a 21st century path. The political dialectic of the show is all too familiar, but Sweeney and Vulcan move beyond this mundanity.

The performance is conducted from a trestle table with 2 laptops. The computers appear to have no other function apart from receiving confessional emails from a collaborator supposedly situated in Brussels, who also appears on Sweeney’s screen singing a bastardised version of a popular song. The whole set up suggests a dubious dysfunction that may or may not be intentional: artists propelled back in time to 50s Australia, a surreal place in which metaphors of shit, blood and vomit prevail. Might this be symbolic of the end of the romance between the Australia Council and new media and hybrid artists brought about by the recent dismantling of the New Media Arts Board? Possibly, but you may not glean this from the performance if the allusion was not included in the publicity. Perhaps artists should have known that once the business world dispensed with its short lived fetish for new technology, it would only be a matter of time. In a sometimes shabby and often eccentric show, there is power in Sweeney and Vulcan’s suggestion that the party is over. Like dead meat, the characters are left hanging on a butcher’s hook. And the blood flow is slow and painful from a couple of wounded hearts drunk in the kitchen at a party now trapped in time.

The Rouge Room: Unreasonable Adults, The End of Romance, performers Jason Sweeney, Julie Vulcan, outside eye/collaborator Ingrid Voorendt, remote artists Caroline Daish, Jaye Hayes, Stephen Noonan, Kerrin Rowlands, Theatreworks, Melb, Aug 25-Sept 1

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 35

© Tony Reck; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Zen Zen Zo, those with Lucifer

photo Morgan Roberts

Zen Zen Zo, those with Lucifer

Zen Zen Zo’s latest work those with Lucifer is the first of what will be an annual In The Raw Studio Season providing a space where the company, now in its 13th year, “can return to its experimental roots, and develop new, challenging and edgy works.” It also marks the first time that Artistic Directors Lynne Bradley and Simon Woods have handed over the directing reins, in this case to their newly appointed Associate Director, Steven Mitchell Wright.

According to Wright, those with Lucifer was inspired by the myth of Lucifer’s fall from heaven as punishment for sin. Told from the perspective of contemporary humankind or “sinners”, using the Seven Deadly Sins as a framework and the fall of Lucifer as a starting point, the performance and its audience moves through the space of Sub-Station 4 (a disused power station). Along this journey, we and Lucifer (Katrina Cornwell) are introduced to sins written on the wall and performed by the ensemble or by various configurations of duets and trios. All the usual suspects appear: Sloth, Gluttony, Greed, Envy, Lust. Variously depicted through images of yuppies socialising (“Sloth”) or babies slopping up pasta (“Greed”), these episodes were engaging and entertainingly performed, but for the most part steered clear of exploring the consequences of sin. Those episodes that did left a lasting impression.

“Pride”, the final episode, began with what was a signature image for the work, one which opened and closed the show, each performer standing before the audience with arms and fingers extended straight up, faces tilted towards the sky, in an exquisite expression of abandon and endeavour. The race-like scenario that followed provided a compelling image for a physical theatre company, where training is all and ego is often one of the first hurdles. Here, as in “Envy”, which honed in on the consequences of body image, “sin” seemed to take a toll.

The shifting ground of what qualifies as divine, or moral or just plain good taste makes it difficult to know what constitutes sin nowadays. When bureaucrats and politicians lock up children in the desert and callous indifference to human life seems the norm, these old sins just don’t seem to cut it anymore. Or perhaps a redefinition of sin is in order. In those with Lucifer ‘sin’ was for the most part associated with things that seemed more fun than evil.

Zen Zen Zo has a knack for nurturing emerging talent whose passion for performance feeds and enriches their work. The abandon and joy exhibited by this young ensemble created a kind of ‘total performance.’ Particular mention should be made of Katrina Cornwell, her Lucifer acted as both observer and participant, providing the perfect conduit for the audience. This was a sold-out season, with extra shows added. To see young audiences and young performers clearly engaged by the potential of live performance demonstrates that this In the Raw season represents an exciting new step for Zen Zen Zo and for their work with emerging talent in Queensland.

Zen Zen Zo, those with Lucifer, director: Steven Mitchell Wright, performers Katrina Cornwell, Mary Findlay, Kat Henry, Mark Hill, Katie Hollins, Tora Hylands, Robbie O’Brien, Kat Scott, Helen Smith, Peta Ward, Annabelle Winkler, co-choreographer Lynne Bradley, composer: Colin Webber, sound artists Emma Dean, Lyndon Chester, lighting Simon Woods, designers: Steven Mitchell Wright, Suzie Russell, Annabelle Winkler, Sub-Station 4, Brisbane, July 20-30

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 35

© Leah Mercer; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Stace Callaghan and Margi Brown Ash, The Great Exception: or, The Knowing of

Mary Poppins

photo Juanita Broderick

Stace Callaghan and Margi Brown Ash, The Great Exception: or, The Knowing of

Mary Poppins

In a year in which Queensland celebrates the centenary of the women’s vote, theatrical testimonials to a renegade feminist history in the state have been surprisingly few and far between. Sue Rider’s The Matilda Women springs to mind as an earlier contribution. With such offerings to the national body politic over recent decades as Lady Flo, conservative socialite/mayoress Sally Ann Atkinson and a certain red-headed rightwing firebrand and ballroom dancer, turning to the world of letters by way of inspiration seems a much more edifying option for contemporary performance makers. Whatever the gender or political hue, Queensland undeniably does a fine line in radical individualism and it is fitting, then, that the determinedly eccentric P L Travers (creator of the character Mary Poppins) should have emerged from federation era rural Queensland. As theatreACTIV8’s production The Great Exception: or, The Knowing of Mary Poppins asserts, the home-grown cultural milieu certainly gave Travers something to run passionately away from in the long trajectory that was her gloriously idiosyncratic life.

Taking Valerie Lawson’s biography Out of the Sky She Came as a departure point, director Leah Mercer pooled a strong ensemble, including writer Marcel Dorney and actors Margi Brown Ash, Stace Callaghan and Carol Schmidt to create a unique performance experience in which theatreACTIV8’s bold physical sensibility combines effectively with Dorney’s dialogue driven text. The actors each inhabit an aspect of Travers’ female (if not always avowedly feminist) psyche: a triptych Travers herself describes as comprising nymph, mother and crone. The cast glide effortlessly between these constructions at various points of Travers’ cantankerous life, intruding upon and contradicting each other’s sketchy and subjective accounts of her narrative.

Particularly intriguing in this regard is Travers’ complicated relationship with men, who, if women are assigned 3 basic archetypes, might also be correspondingly described as either genius, father or fool. Certainly, her first major love interest, the Irish poet ‘A.E’ is nominated by Travers as the former; whilst mystic, Gurdjieff, might be considered any of the above; and studio chief, Walt Disney, absolutely the latter if not the former. Callaghan in particular does a fine job of animating Dorney’s amusing popinjays and patriarchs, creating the chilling sense of a fourth (male) actor in the ensemble (whom I was faintly disarmed not to find appearing in the curtain call).

The famous Poppins iconography—umbrella, starched blouse and long skirt (equally at home in the Kransky Sisters’ Esk Valley mise en scene) and crisp uber British consonants and nasal vowels—wend their way with marked constraint into the performance text. Poppins-esque gewgaws hang from Celtic wiccan-like totems in Conan Fitzpatrick’s initially intriguing (but ultimately under-utilised) scenic design. Schmidt’s Poppins only occasionally utters the iconic “spit spot!” and the overall effect is aptly one in which the complex personality that created Poppins, rather than Poppins herself, takes centre stage. Indeed, as Ash Brown’s wonderfully world weary crone suggests, it was never a matter of having ‘created’ her at all, but of allowing her to descend, enigmatically, from the ether. Robert D Clark’s evocative and jaunty sound design is worthy of special mention here by way of invocation.

There was much to like about The Great Exception. With an all too brief 4-day run, this rough gem, with a little further polishing, deserves a second appearance before a wider audience.

theatreACTIV8, The Great Exception: or, The Knowing of Mary Poppins, director Leah Mercer, writer Marcel Dorney; Visy Theatre, Brisbane Powerhouse, August 17-20

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 36

© Stephen Carleton; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

!Metro Arts’ Independents series began with a trial run in 2002 under Sue Benner’s pioneering artistic directorship. More an attempt to forge a hothouse environment for the city’s freelance performance practitioners than an effort to house any pre-existing overflow of activity, the series was an immediate success and has become a fixture in the Brisbane arts incubator’s annual programme. !Metro promotes itself as being “in the centre…on the edge”, and indeed it’s an edge the city desperately requires. Having championed physical theatre and circus longer than most Australian capitals, and having one of the nation’s most committed mainstage writers’ theatres in La Bôite, !Metro has stepped up to the plate and provided the forum for a genuine affordable fusion space for artists across the span of the city’s eclectic contemporary performance spectrum to collaborate, experiment and push parameters. It’s a space where artists—at various stages of their careers, and regardless of their area of performance specialisation—can try and fail, though in the case of the Restaged Histories Project’s latest offering, The Greater Plague, the signs of success are strong.

Set during a plague year—an iconic plague year, as it transpires—during the 17th century, writer-director Nic Dorward’s heterotopic exploration of disease takes place in a specialist London asylum in which denizens of the city unaffected by the epidemic are quarantined for 40 days of sustained physical deprivation and psychological abuse. The most immediately arresting image is Kieran Swann’s starkly ingenious design: !Metro’s inflexible black box is subverted by a white box within. The Plague House is represented as an antiseptic white puzzle box—a berko Rubik’s cube that shifts, slides and reveals slots that double as windows, doors, fire grilles, escape hatches, peepholes and gaudy picture frames.

Two sisters, Lettice (Morgan French) and Edith (Saskia Levy) stumble in through the floor, having broken in through the neighbour’s cellar. They are escaping a domestic abuse nightmare in Paris, and inadvertently find themselves trapped in an exponentially more ghoulish world within the asylum’s macabre confines. Theophilia (Emily Tomlins) is about to give birth, and faces an extended 40-day incarceration in the hellhole if the baby survives. The deranged Nurse (Louise Brehmer) and Bearer (Jonathan Brand) prey on the inmates in fiendish (and, in the latter’s case, necrophiliac) delight. All the cast are excellent.

Dorward’s idiosyncratic directing combines improvisation and extended physical scenes as well as robust adherence to immaculately researched and intellectually rigorous dialogue that makes no apologies for its historical fetishes and predilections. Indeed, the whole piece is refreshing for its refusal to kowtow to lowest common denominator audience expectations, without ever lapsing into prosaic self-indulgence or obscure self-referentiality. It is not a naturalistic narrative. The audience is required to work, to use its imagination to piece together the individual character back-stories (told in impro-styled comic flashback).

There is a feast of physical, visual and linguistic images woven together and driven along by an exceptional sound design by Luke Lickford. There is a renegade bonhomie in the ostensibly mordant study of incarceration that augurs extremely well here, not just for the careers of the team of emerging artists involved, but also perhaps for the future of independent contemporary performance in Brisbane.

The Greater Plague, writer-director Nic Dorward, designer Kieran Swann, sound Luke Lickford; producers Restaged Histories Project and !Metro Arts Independents!; Metro Arts, Brisbane, Sept 7-24

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 36

© Stephen Carleton; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Steven Ajzenberg, Nick Papas, Not Dead Yet

photo: Sandra Matlock

Steven Ajzenberg, Nick Papas, Not Dead Yet

Rawcus & Born in a Taxi

During an Australian tour last year, New York dancer/theorist Bill Shannon expanded upon his performances by incorporating discussions of a particular politics he saw as essential to the reception of work by those with bodies outside of the social category of ‘normal.’ Shannon, on crutches since the age of 5, articulated an aesthetics of “failure and heroics”—a kind of grass-roots discourse of performance as becoming, rather than being, of process over product. Every performance is an attempt, and ‘failure’ is not an aberration but a component of expression with its own significance. The majority of live performances seek to conceal the attempt in favour of the end result, but differently-abled bodies draw our attention to the normative politics of such an endeavour. The distinction between what could be termed the ‘try’ and the ‘act’ is something that separates sports, circus, comedy and some forms of dance such as breakdancing or tap from more traditional modes of performance which seek to pave over the effort that goes into delivery.

Viewing performers with disabilities can reveal some of the underlying assumptions we bring to our interpretation of all performances. Do we judge disabled performers differently? Probably. But works like the recent Not Dead Yet can help us to understand this as a productive way of seeing. Judging an actor’s ‘ability’ here takes on a new dimension: after all, we often praise or condemn a non-disabled actor’s ‘ability’ in a role without considering the kinds of politics which might surround such interpretation.

The cast of Not Dead Yet is made up of contemporary physical theatre ensemble Born in a Taxi and Rawcus, a company featuring performers with and without disabilities. Born in a Taxi’s Penny Baron devised the piece after a South American journey which introduced her to Aztec and Incan cultures’ worship of disabled individuals as guides into the afterlife. Not Dead Yet is a group-devised response to death and the hereafter, and though there is a loose narrative thread to the piece (a woman’s slow journey after death), the piece is largely composed of a series of disjointed responses to the overall précis. Part of the work’s enjoyment comes from realising the questions posed by each scene: how would you least like to die? What are you afraid of leaving behind? What would you most hope the afterlife to hold for you? This last question underscores one of the piece’s most moving sequences, an initially cryptic scene in which performers throw paper planes, play in a sandpit, or slow dance together. When blind and wheelchair-bound Ray Drew, who was himself pronounced technically dead after being electrocuted, begins to cry “I can see again! I can see again!” it becomes apparent what is being explored here. Moreover, the emotional affect of this scene is so powerful precisely because it acknowledges the embodied experiences of its participants, both disabled and otherwise.

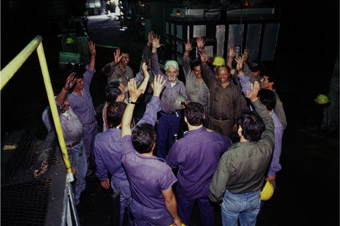

Theatre@Risk

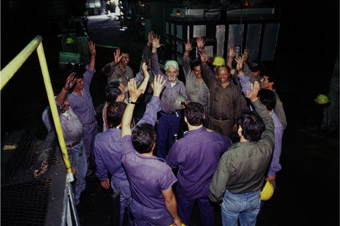

Australian theatre has sometimes struggled to find a footing when dealing with urgent political issues. The tendency towards didacticism must be tempered with a realisation of the sophisticated theatrical vocabulary of audiences, many of whom are sensitive towards overtly polemical narratives. Theatre@Risk has already demonstrated an ability to address contemporary affairs with delicacy in mounting recent works from abroad (Terrorism; Arabian Night) and original productions (The Wall Project; 7 Days, 10 Years). Stalking Matilda engages with the politics of paranoia and the treatment of refugees, ostensibly exploring the mysterious death of its heroine as a means to uncover a society of trenchant racism, institutionalised xenophobia and ultimately explosive class tensions. An ensemble of uniformly strong performers creates the social environment in which the doomed Matilda and her immigrant husband move, and as we learn more about the 2 we begin to question our own complicity in such a perilous state of affairs.

While the politics of stalking itself offers fruitful ground for a theatrical work, the title of this piece initially appears somewhat misleading. A trenchcoated voyeur occasionally hovers at the fringes of proceedings but only rarely becomes a notable figure. As the story unfolds, however, it begins to appear as if the audience itself is the stalker, looking in on, at times, obscured views of the central character’s life, piecing together a distorted composite image of her complex existence. It is a testament to both Tee O’Neill’s writing and Chris Bendall’s direction that the idealised, glamour model portrait of Matilda is always rendered only partially, while remaining a distinctive and many-levelled characterisation. As Matilda herself, Jude Beaumont creates an entrancing intensity for a character who is in other ways composed only of surfaces. In this she is matched by Rob Jordan, whose charismatic portrayal of Matilda’s husband Suleyman is both sympathetic and bold. Staggering through a city street, clutching a rag to an open stomach wound, it is apparent that Jordan understands the importance of subtlety in what could otherwise have been an overplayed death scene. In this, as in most of Stalking Matilda, Theatre@Risk has once again produced a keen-edged and incisive investigation of local and international politics and the pressures which place both social and personal ties in crisis.

Stuart Orr

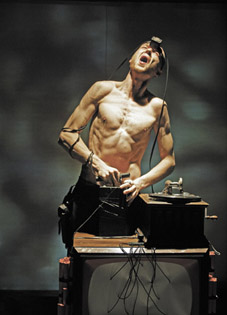

Stuart Orr, Telefunken

photo Jeff Busby

Stuart Orr, Telefunken

The recent remounting of Stuck Pigs Squealing’s Black Swan of Trespass and the commissioning of Telefünken are part of Malthouse Theatre’s new Tower Theatre program. Independent artists and companies are invited to stage existing or new works in the intimate venue and are given creative freedom to present their final product without interference from the company. At the same time, they are required to provide the kinds of progress reports and budgets which would be expected of a larger, professionally mounted production, thus schooling emerging artists in the kinds of practice which await them later in their careers. It’s a gamble, but one which has so far resulted in strong works which add a vital energy to the Malthouse calendar.

Telefünken is a solo show devised and performed by Stuart Orr and directed by Barry Laing. I’m not sure if Orr was inspired by author Thomas Pynchon’s magnificent opus Gravity’s Rainbow, but this was the text which most forcefully impressed itself upon my interpretation of the piece, and that’s a potent recommendation. Like Pynchon’s notoriously difficult work, Telefünken re-imagines the closing moments of World War II through a cacophony of voices and embedded narratives. Trapped within a Berlin moviehouse as Russian tanks roll into the city, the audience is confronted by an SS soldier eager to relate the story of his life, but the manic deserter does so by both describing and enacting his tale as a movie with storyboard, commentary and dialogue, amongst other framing devices. The plot unfolds through this series of competing mirrors, and Orr’s incarnation of Mann, the increasingly erratic storyteller, emphasises his position as the postmodern Unreliable Narrator, who may be mad, sick, duplicitous or forgetful. We are never provided a safe position from which to make sense of these events, instead attempting to navigate this explosive terrain in the same method as our guide.

Like many of the postmodern authors of the late 20th century, Orr also offers us Telefünken as an encyclopaedic narrative, one which matches densely textured detail with an impressive scope. The many streams which carry through the piece include Northern European mythology, reality television, the modern psychology of crowds and the mutability of history. Orr plays a multitude of characters, and though his accents are impressive there is room for development in the area of vocal delivery. This quibble aside, if the rest of Malthouse Theatre’s Tower season matches this level of brave innovation, few will argue with the direction the company has chosen to take.

Not Dead Yet, directors Penny Baron, Kate Sulan, designer Emily Barrie, lighting Richard Vabre, deviser-performers Steven Ajzenberg, Clem Baade, Kellyann Bentley, Ray Drew, Rachel Edward, Nilgun Guven, Carolyn Hanna, Valerie Hawkes, Nick Papas, Kerryn Poke, Louise Riisik, Jolan Tobias, John Tonso, presenters Born in a Taxi, Rawcus Theatre Company; Theatreworks, St Kilda, Sept 15-25;

Theatre@Risk, Stalking Matilda, writer Tee O’Neill, director Chris Bendall, performers Jude Beaumont, Irene Dios, Odette Joannidis, Rob Jordan, Toby Newton, Jeremy Stanford, designer Kelle Frith, sound Kelly Ryall, lighting Nick Merrylees; Theatreworks, St Kilda; Aug 5-21

Telefunken, writer-performer Stuart Orr, director Barry Laing, Tower Theatre, Malthouse. Melbourne, Sept 14-25

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 37

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ryk Goddard, UTE 4 Universal Theory of Everything

photo Sandi Rapson

Ryk Goddard, UTE 4 Universal Theory of Everything

For the past 4 years Hobart’s innovative is theatre ltd has conducted the National All-Media Improvisation Laboratory under the umbrella of the Boiler Room Improvisation Festival, holding a series of workshops in sound, words and voice, movement, technology and physical comedy. At the end of each day a performance highlights the skills and techniques achieved. The final night—the performance I saw—was described as a “cross-artform slam.”

Artistic director Ryk Goddard explained, “Everything you see tonight will be improvised, from the lighting to the sound, movement and images.” Part 1 evolved as a wryly amusing, absurdist piece with kung-fu moves, a tentative love scene, an engrossing, rambling monologue from a ‘Chinese doctor’, a skit-like interlude with a female protagonist and a gnome, and lots of use of 2 chairs and a cupboard, the ‘characters’ almost generating a coherent narrative. There was plenty to entertain, provoke and amuse, much of it beyond rational explanation.

Part 2 of the presentation, UTE (the Universal Theory of Everything), was a process researching improvised performance as a site-specific collaborative practice. To quote the Boiler Room program, “the challenge [is] to lift impro beyond the interesting and make work that combines the power of theatre, the visual impact of installation and the physicality of dance.”

Titled The Room, this manifestation of UTE investigated the room or cell as a site for “interaction and performance, refuge and imprisonment.” The 3 performers navigate their way in and out of a flexible, multi-purpose, interactive space created from swathes of suspended translucent fabric. Music is integral to the piece, a minimal, repetitive guitar solo setting the tone. Performers dance, pose and make abstract movements. They interact with the white cube, moving in and around the space, pulling at and manipulating its fabric walls into a fascinating variety of shapes and configurations—after which, thanks to ingenious design, it all springs back into its original form. Digital projections onto the walls add to the ambience.

Without the safety net of script and rehearsal, Boiler Room was genuinely entertaining, frequently amusing, thought provoking and absorbing, a triumph of improvised theatre.

Another unconventional performance was Jeff Blake’s anarchically original one-man show Cancelled by Popular Demand. Its non sequitur comedy is reminiscent of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Groucho Marx and the Theatre of the Absurd—to name but a few elements. Physical comedy features prominently—cricket balls are lobbed at speed against a side wall; Blake climbs into and over the audience, muttering grumpily all the while; shuttlecocks are randomly hit into the auditorium; and the performer’s neatly suited character intersperses the early parts of the performance with shuffling, deliberately self-conscious ‘cool’ dancing.

The comedic dialogue zanily dissects humanity’s woes and evils, astronomical phenomena, Shane Warne’s bowling, crooner-style cabaret…the list beggars belief but it all works outstandingly well. One of the most absorbing performances I have seen in Hobart for ages.

National All-Media Improvisation Laboratory, Boiler Room, performers scot d cotterell, Cam Deyell, Ryk Goddard, Bec Reid, Martyn Coutts, Greg Methe, Aaron Roberts, James Wilson, Caleb Doherty, is theatre ltd, Backspace Theatre, Hobart, Aug 25-28; Cancelled by Popular Demand, writer-performer Jeff Blake, Peacock Theatre, Salamanca Arts Centre, Hobart, June 22-26

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 38

© Diana Klaosen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

My memory of Romeo Castelluci’s Giulio Cesare at the 2000 Adelaide Festival (RT 36, p22) is frighteningly vivid. Although a substantial variation on the text and themes of Shakespeare’s play, it served nonetheless as a radical reading of the classic, the problems of the protagonists writ large and displaced into bodily distortions and the wasteland generated by civil war made devastating almost beyond imagining. Benedict Andrews’ production for the Sydney Theatre Company is, instructively, a very different creature, revealed in the portrayal of an altogether cooler, pragmatic culture as epitomised in Robert Cousin’s set—a bleak cut-away concrete amphitheatre, evoking both the senate house of ancient Rome and the brutalism of modern stadiums. Here there are gross entertainments straight out of Abu Ghraib prison, a fairy floss seller, thuggery and conspiratorial gatherings, but the mood is of restraint and paranoia. This is epitomised in the portrayal of the crowd, so pivotal in Shakespeare’s Roman plays. Andrews has disappeared the crowd, but in very revealing ways.

First seen, the crowd comprises surreally masked, distracted and isolated individuals scattered across the amphitheatre. They hardly warrant the lecturing and hectoring by their betters in the opening scene. After Caesar’s death they become mere noises-off during the orations of Brutus and Anthony: none is physically present, their whisperings and calls transmitted through loudspeakers on stands placed about the Forum. It’s as if the crowd is mere background noise to the great political machinations taking place. So it is today, any politician invoking public opinion or a silent majority is bound to be wielding a fiction. The focus in this Julius Caesar is a very interior one, full of difficult choices and populated by the ghosts of the victims of political logic.

Brutus (Robert Menzies) looks like a harried home body, hair wildly tousled, dressed in a red woolly with white shirt sticking out, certainly a very interior, unfashionable man, marked by his anxieties at very first sighting and not someone who deals with the world, conspirators or Cassius face to face. Andrews choreographs the action so that this isolation, political and domestic, is unmissable. Cassius (Frank Whitten), dressed in a suit, is a watchful businessman, physically relaxed, mentally alert, another man who keeps his distance. Both actors speak with a quiet intensity in a delivery that is lucid, the poetry more conversational than sung, slow and considered, and true to the inexorable logic of the play as it moves towards Caesar’s death. And slow and intense the first half is, capped by a slo-mo murder in mime and Brutus’ washing of the body…in blood—as if he, like Lady Macbeth, has come face to face with the enormity of his crime and nothing will wash it away.

After Anthony’s speech (Ben Mendelsohn playing a truly blunt man, all the rhetoric in the shape of the argument rather than in flourish) many a production slips into decline—there are no heroics to be had in the bickering between Brutus and Cassius or in the nuances of loyalty tested by pragmatism, or in the pathos of Brutus’ suicide. Andrews now accelarates his production and wisely concertinas a number of scenes into one, set at a long table lit only by hundreds of candles. Brutus, Cassius, allies and the ghosts of the recently deceased sit on one side looking out over the audience. Forced to avoid eye contact throughout and driven by the staccato structure this scene yields from Brutus and Cassius an unprecedented emotional intensity that reverberates beyond private tragedy to the destruction of the very republic the pair were defending. It’s a nightmarish scene that builds to sudden release when Brutus and Cassius do finally face each other and Cassius accepts his friend’s strategy, although knowing it means defeat. Andrews’ approach here has a power that might have advantaged the production elsewhere; in this scene it gripplingly prepares us for demands of the play’s final bleak moments. This is a fine, engrossing, sometimes visionary Julius Caesar.

In progress

The Sydney performance scene appears to have been quiet in recent months, but there’s a lot of backroom activity. Showings of works in progress in Performance Space’s Headspace, its hybrid performance laboratory, revealed a number of pieces already far advanced in vision and realisation. Branch Nebula’s Project No 6 (shown with the support also of Performing Lines) seamlessly and erotically fuses skateboarding, BMX-biking, acrobatics and breakdancing in various partnerings—it sounds unlikely but it works beautifully with a hypnotic intensity and not a little physical virtuosity. Karen Therese showed Y. Smith, part 2 of the Sleeplessness trilogy, this time investigating and recreating the life of her mother in moments both delicately intimate and shocking, accompanied by magical images from Margie Medlin. Melbourne’s Neil Thomas and David Wells, as Two Bare Light Globes, gently humoured us with improvised tales and new songs about what it means to be a man in Man Talk. Jeff Stein and collaborators in Il Ya led their audience into one of the strangest experiences encountered in contemporary performance in recent years. Inspired by Emmanuel Levinas the work takes us into spaces that are both physically and philosophically dark, and hard to describe. Stein and company are off to Italy to develop the work further in Romeo Castelluci’s studio.

At Drill Hall, Critical Path presented German dancer and choreographer Antje Pfundtner (interview p12) in a remarkable solo performance for a small audience after the workshop she’d been running for local choreographers. Combining unusual shapings of the body and tales from her own and other’s lives, Pfundtner is charismatic, her performance fluid and idiosyncratic. It’s hoped that Pfundtner will soon return to Australia to perform her work publicly and conduct another workshop.

Julius Caesar, William Shakespeare, director Benedict Andrews, designer Robert Cousins, costumes Alice Babdidge, lighting Damien Cooper, sound/composer Max Lyandvert, Sydney Theatre Company, Wharf 1, opened July 1; Headspace, Performance Space, July 18-Aug 28

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 38

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

For many individual artists and small companies working in performance, the time and energy they expend on self-producing is becoming increasingly exhausting, often threatening to drain their creativity. One solution, often raised but rarely discussed in depth, comes in the form of the ‘creative producer’, a kind of cultural angel of mercy.

On August 8 RealTime and Performance Space held the latest of our popular open forums for artists, this time to address the role of the producer in contemporary performance. Some 50 artists, curators, producers and venue managers listened to and talked with our guests. Rosemary Hinde is the director of Hirano, an agent and a producer of dance across Australia and Asia. Martin Thiele works as a producer in performance, film and new media. Harley Stumm, formerly with Urban Theatre Projects, is now working for Performing Lines. Amanda Card is the Executive Producer of One Extra Dance. Hinde and Thiele are based in Melbourne, Stumm and Card in Sydney. The session was hosted by RealTime’s Keith Gallasch and Performance Space Artistic Director Fiona Winning. What follows is drawn from the complete, transcript. See RealTime-Performance Space Forums on the left of our home page for other forums).

Agents, presenters, producers

You could say that all producers are creative, that they search out and nurture the creativity of others. But, of course, some producers are more creative than others, in particular those who don’t just pick up an already developed work but who are in there from the beginning, with the artists, helping to shape, fund and mount the work, sustaining the artists’ vision.

In the Australian performing arts, our image of the producer, let alone creative producer, is not very clear. There are agents: some look after artists and groups as individual entities, others harness a particular group of artists, like Strut ’n’ Fret (unfortunately unable to make it to the forum) in Brisbane who have effectively put together a stable of idiosyncratic, cutting-edge cabaret performers. Some double as agents and producers, alternating roles as the need arises. There are venues whose programming helps to shape a terrain for artists to work, ranging from the incubators, like Performance Space and PICA, to the Sydney Opera House where Philip Rolfe, Virginia Hyam at The Studio, and other staff will program seasons but also commission some work and follow its gestation and development through to the end. Then there’s Performing Lines. It picks up innovative work it thinks it can tour successfully and sometimes can be in there from the beginning as a producer with artists and projects it feels it can commit to. But its resources, and its brief, for this kind of activity are limited.

Is there something missing from the arts ecology at the moment—a group of independent producers who are not necessarily attached to venues and who are not agents but who work closely with a small group of artists and companies? The forum began to work towards establishing precisely what role the creative producer plays, who needs them and how funding models can accommodate them.

Amanda Card described the evolution of One Extra from an artistic director-driven company to a facilitator for choreographers and dancers to mount works with Card herself as executive producer. The move was in part responsive to local needs: “the bottom had fallen out of the company structure…It was also generational. A lot of people were coming out of companies and wanting to create their own work but there wasn’t a model [and] not enough time to spend in the studio creating the work [while being] administrators, marketers, financiers, whatever.” Card said that One Extra provides those services where possible and as early as possible in the development of new work.

Rosemary Hinde has run Hirano Productions for 15 years: “I do 3 things. I function as an agent. I represent companies with existing productions and tour them within the Asian regions on a tour-by-tour basis. I produce collaborations and co-productions with international partners from Asia—and that’s a big part of my work. Also, where it’s possible, I present Asian companies in Australia—mostly in the areas of dance and physical performance… Artists’ interests, it seems to me, have traditionally been represented and safeguarded by managements and agents. Their role is to represent the artists rather than that being part of the producer’s role.” Hinde thinks that the label “producer” has been widely adopted, but without addressing what the role entails: “Ten years ago when you dealt with Australian arts companies, they had general managers and artistic directors. Now they all have executive producers.”

Inhibiting structures

Both Hinde and Thiele spoke of the problems presented by traditional company structures. Thiele described company producers expending more energy on servicing boards of management than on their creative role, a condition he’s worked on overcoming in his own practice. Hinde put a case for reviewing company structures: “Traditionally, within a funded and not-for-profit context, funding has been driven through the core unit of the company with its general manager and artistic director or executive producer. Historically, that’s been the basic unit and model of arts funding in Australia. Now, I’m actually not sure that that is any more the most economically productive way of deploying funding because it seems to me—and I work with companies. I tour companies that have exactly those structures—that what you’re effectively doing when you fund things that way is to duplicate roles…A company that does 2 seasons a year, it seems to me, doesn’t need a marketing manager. But maybe 6 companies who are grouped together with a complementary set of skills, in the way a festival works with specialist managers who come together and work as a team that service each of those individual companies, might be a better way of looking at it. Performing Lines is definitely one model. Arts Admin in London is also a model that supports companies over time.”

There was further discussion about artists not needing to build their own stand-alone company structures or, certainly, elaborate ones. It was suggested that more than ever before there are various structures to tap into and make good use of—Performance Space, the Sydney Opera House, Melbourne City Council (which has its own Creative Producer in Stephen Richardson), Hirano, One Extra, Performing Lines, and agents who do also act as producers, like Marguerite Pepper and Strut’n’Fret. However some inhibiting factors were described. Rosemary Hinde pointed to the growth of arts centres “which lock up an enormous amount of resources…are hard to access and don’t work with potential national and state partners.”

Anne-Louise Rentell described the Illawara Performing Arts Centre as addressing the producing role for local artists. Rentell is Performing Arts Facilitator in Wollongong, a position created by the NSW Ministry for the Arts to facilitate professional performing arts in the Illawarra region. She describes her role as “a semi-producer.” The centre is well-resourced, programs big companies, has “2 great venues”, so, says Rentell, “we’re ripe to actually provide opportunities for development and to produce local work from the ground up.” In this model the centre provides staff and facilties, but the funding for artistic content is sought from the state and federal governments and, if touring, through Playing Australia. Perhaps then, as with Melbourne City Council, local government could focus on funding creative producers.

Creative status

However, some speakers thought that attitudes to producers would need to change as well as the organisational and funding structures already discussed. Both Martin Thiele and Harley Stumm spoke of the importance of the producer in areas superficially not part of the creative process. Thiele said, “I think a creative producer provides consensual, logistical compliance, financial and technical support to a project or at least oversees those particular elements of a project. I think in [performing] arts, film and television, which are the 3 mediums I’ve worked in over the last 12 months, the producing element is essential.” Stumm commented, “I think a lot of the things that are often seen as ‘dry’ management tasks (budgets, schedules and so on), they’re just a different discourse about the creative process. A budget is a plan for the distribution of resources. So, you can’t do all that work without having a really clear idea of the vision for making that work of art.”

Thiele’s concern is that the performing arts needs independent producers, but that they have no status: “Historically, artists have taken responsibility for self-producing and I think that within the arts support infrastructure there’s still an assumption that artists will take that responsibility. And I think that’s something we need to address because, generally speaking, independent creative producers have very little status within the arts. Within the film industry it’s acknowledged that such support is core and essential. So a producer is acknowledged alongside a writer and a director and, in terms of the budgeting structuring, is what you call “above the line.” So it’s acknowledged that the role the producer plays is a core part of actually creating an artwork, a film.

Another model

Fiona Winning introduced “another model—one of my fantasies—that might sit alongside a series of other models such as [the local government one]. This is of an independent producer with a very lean machine/office. They work with a cluster of artists in quite intense relationships over a number of years to create their vision, whether it be to develop a work, make a new work, to get that on somewhere, to get it toured either nationally or internationally.”

Sophie Travers, director of Critical Path (a NSW dance workshop and masterclass program at Drill Hall, Rushcutters Bay), who has had extensive experience working in the UK, was asked to describe the work of Arts Admin. She said it’s a successful, government subsidised team of producers each working long-term with a particular group of innovative artists on projects, programming time out for artists to do research or take sabbaticals, working across artforms, and offering artist bursaries. Travers described Arts Admin as “pretty much your dream model. I think it’s really interesting that the model is held up around the world and in the UK itself and yet it doesn’t exist anywhere else. So even in the UK everyone acknowledges that that is the model but nobody can replicate it.”

Travers added that, “Each producer has a range of companies that they’re responsible for. But they also have a different skill set. So every time they introduce somebody new, they bring in different cultural networks or different sponsorship. So they’ve evolved with the times, but they’ve kept that one-producer-for-one-group-of-artists. And they really range. Some of them are like an individual who makes one work every five years to companies like DV8. They work across performing arts, visual arts. They pick up projects and put them down again.”

Devolution

Arts Admin, along with Performing Lines and the Mobile States group (a consortium which includes Performance Space, PICA and other spaces around Australia touring innovative performance), are examples of organisations managing devolved funds. The discussion focused on the advantages of this model where a network of independent producers could, with creative verve, lean management, on-the-ground know how, and direct contact with artists, choose the artists they want to work with and develop long term growth in the performing arts. Over post-forum drinks, participants felt that the time had come to research producer models like Arts Admin, to look at the particular needs of Australian artists and to reconsider current company structures and funding models. No small task, but worth the venture given the urgent needs of artists and the the presence of individuals in the arts community capable of becoming committed creative producers.

See also Wanted: Creative Producers – FULL TRANSCRIPT

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 pg. 40

© Virginia Baxter & Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

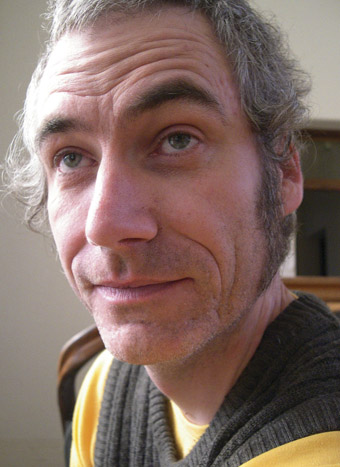

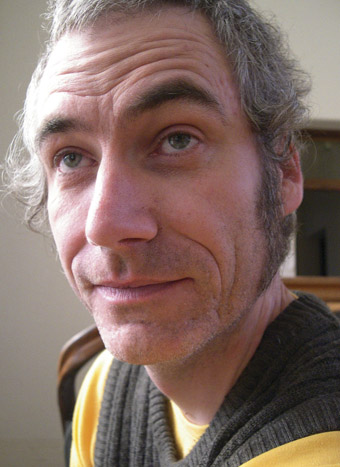

Deborah Kayser

photo Yatzek

Deborah Kayser

David Young is a composer and co-artistic director of Melbourne-based and world roaming Aphids. Around composer and company a world of collaborations constellate. The Libra Ensemble are premiering Young’s song cycle Thousands of Bundled Straw for the 2005 Melbourne International Arts Festival. Shortly after comes a showing of Origami, the working title of a new BalletLab work in collaboration with BURO Architects who are designing the huge folding set under instructions from the origami-inspired artist Matt Gardiner (whom Young worked with on Oribotics) and with graphics by 3deep design. Young is working with Jethro Woodward and Eugene Ughetti of Speak Percussion on the sound score, partly electronic and partly live and using graphic notation informed by Gardiner’s work.

When Young says ‘graphic’, he means that the instrumentalists respond to non-musical notation as in Skin Quartet where the instrumentalists follow instructions on how to musically interpret skin tones or tattoos in photographic images. This multimedia string quartet performance recently appeared in the Time Based Art festival (curated by Melbourne Festival’s Kristy Edmunds) in Portland, Oregon, before going on to Les Bains::Connective Festival in Brussels (where Aphids was in residence in 2004), and Johannesburg.

In November, Aphids, will present Gardiner’s new version of Oribotics as an installation at the Asialink Centre with Young again writing music with Jethro Woodward and Eugene Ughetti. Aphids co-artistic director Rosemary Joy is creating new percussion instruments for the show.

Young sees this set of shifting collaborations within and beyond Aphids as organic, “like a theatre or music ensemble, but not all musicians. The sense of an emerging ensemble is a new thing, an evolution of Aphids. It’s like a new species, but I don’t know what it is.”

In December, at the Big West Festival (in Melbourne’s western suburbs) Speak Percussion will present Ughetti solo in Raising the Rattle, a performance of works he’s commissioned from 4 Australian composers, along with elements of Oribotics.

At the end of the year, says Young, “we’re doing the creative development of our next work, which is Nasu [The Eggplant Project], a Belgian/Japanese/Australian collaboration with 3 composers and 3 musicians.” Beyond that, Young is thinking about a new work based on his “fascination with people being so obsessed with space and yet not knowing anything about deep sea life. It’s almost like psychological denial, a blind spot. I want to do a performance at the bottom of a diving pool with an audience in the water.”

Hybrid life

Unlike other new music ensembles, when I think of Aphids, it’s not music that springs to mind, but strange hybrids of installation, sculpture, video, puppetry, song and sound art. The key, says Young, is the artists: “It’s the people and it’s definitely the fact that we’re not bound by an artform or a format even. That completely opens up the possibility of plugging into different venues and presentation formats, adding different artists. It gives us the freedom. And this is something I discovered with the puppetry trilogy, A Quarrelling Pair, about myself (RT64, p38). While essentially most of the people involved were thinking about it as a theatre show, I was very committed to the fact that I didn’t know what it was going to be. It could have ended up being a radio play or a publication or an installation event, or cabaret. I was committed to suspending judgement. And that’s just because I’ve been allowed to do that through the body of work we’ve been creating.”

Process and duration

In that case, sufficient time for development appears to be critical to Aphids’ success. “Yes”, says Young, “it seems that everything we do takes years. And that’s not necessarily through choice. It’s partly pragmatic. These things take a long time to get together. There’s the underground stream that bubbles to the surface every now and again but it’s always running there underneath. Another metaphor is of plates spinning in a circus act. You give one plate a bit of a spin, run to another as it starts to wobble, and sometimes a plate crashes.” One image of nature, one of artifice and risk: “I can’t settle on one or the other. It is a bit of both. I often talk about nurturing and supporting and tilling the soil. And, of course, Aphids—it’s such an organic, garden-y kind of thing…Certainly that’s what appealed to me about being involved as artistic director of Next Wave. It wasn’t my work but I was collaborating through a nurturing, curatorial role. That happens in Aphids a lot.”

Life cycles

Growth is central to the Aphids vision: “You have an idea, you gradually develop it and collaborate, have some workshops, and maybe you make some experimental tests until eventually you create and present a work. Then it’s documented and kind of solidifies. And the intention has always been that it would then live on in some other form. And that might just be the documentation, a publication, the recording or whatever. But it also might be the tour or the re-mount. And that has happened with works in the past but in a much slower way. Ricefields (1998) was one of our first works that toured. But it took 18 months after its first presentation at La Mama before it went to France and Japan and around Australia. What’s happening now is that cycle is not just faster but a bit more robust and it’s gaining momentum. So that gives us a different kind of fuel. It just gives us different areas of activity, generates more work and more opportunities and more ideas.

Rosemary Joy and I are the kind of engine room. We share the administrative, management/production type things. But also in a way we pin down the activities and events that happen. A lot of the strategy of making these artistic processes unfold happens within that context. But then we also have our formal committee. There are 6 people on that. All of them have been involved from pretty much day one across the decade. They’re the sounding board and the foundation of Aphids. Then, of course, there’s Cynthia Troup who provides a critical perspective and research as well as literary and performing skills. There’s an intellectual rigour which she provides which pushes the work.

Thousands of Bundled Straw

The song cycle has had a long evolution: “I started writing it 10 years ago, just after Aphids started up. I was in Japan at the Temple of the Healing Eyes on Lake Shinji-ko in Far West Japan. There’s a myth about a fisherman who finds a statue of Buddha floating in the water. It appears to him in a dream and tells him if he throws himself off a cliff, his blind mother’s eyes will be opened. So he gets up the next day, wraps bundles of straw around himself, jumps off the cliff and he survives, his mother’s eyes are opened and he founds the temple. You can still visit it. The story goes that he put the statue of Buddha in a box within a box within a box in an altar in a temple. It’s revealed every one hundred years.

“In a way, the song cycle is like that, architecturally—boxes within boxes. But at the heart of it there’s the leap of faith. You’re never going to see the weight of meaning or significance that is within, but you have to believe in it, otherwise it can’t be there.

“I remember writing the first song, which is actually in the fifth part of the cycle. There are 7 parts. The fifth part has 7 songs for voice and guitar, which are written for soprano Deborah Kayser and guitarist Geoffrey Morris. And I remember writing the first one in this fishing village just near the temple and very clearly writing it for Deborah and Geoff. Both have performed in all sorts of projects that I’ve worked on and have been significant collaborators in my artistic career. Deborah was the first person to perform my music in public.”