Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

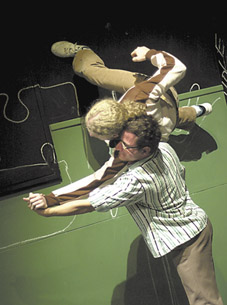

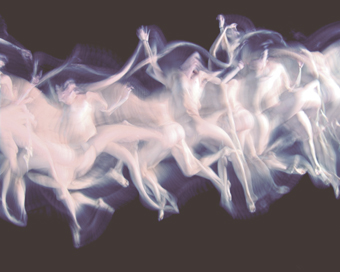

Polytoxic, Teuila Postcards

photo Dallas Blackmore

Polytoxic, Teuila Postcards

The South Pacific has long been a site for European travel fantasy with its geography strategic for colonialist expansion and its languid and intoxicating mix of palm trees and exoticised otherness. Teuila Postcards, the first full length production for Brisbane dance ensemble Polytoxic, is a well-crafted critique of the fantasy, fusing traditional Polynesian and contemporary dance theatre in a very funny and totally engaging take on all things culturally kitsch and colonial.

Following a prologue which sets up the non-linear travelogue narrative with a delightful departure lazzi, we experience Samoa simulacra. Familiar postcard representations of blue sea, blue sky and grass-skirted dancers manufacture desire for escape and excess. And while a long list of cultural protocols and etiquette projected on screen hints at the complexity and nuance of the host island cultures, these are cheerfully undermined with a final Virgin Blue proclamation, “if all else fails, just smile.”

Accompanied by a cheesy pop soundtrack, ensemble members Lisa Fa’alafi, Efeso Fa’anana and Leah Shelton playfully warp the tourist postcards and juxtapose the dream with the reality. A young woman (Fa’alafi) fantasizes her way through her decidedly unglamorous domestic duties with Prince and Whitney on walkman and her short brush broom as karaoke mike and dance companion. Performing a lipsynched show for tourists, a transgender fa’afafine’s (Fa’anana) elephantine eyelashes flutter with mock humility at her admiring audience as momentarily a thought bubble appears, “Oh, I forgot to feed the pigs.” A 19th century missionary’s wife (Shelton) confined in black lace and plastic represents the early Palagi (Europeans) and their erotic obsession with the ‘native night dancers.’ Breathlessly, she takes tea and enquires, “Is immoral behaviour still the fashion?”

In shorter pieces, Polytoxic never fails to entertain through the cheeky playfulness of multicultural choreography and a clear passion for connecting with audiences. And now, a full length production has allowed the ensemble’s natural flair for comedy to develop. This was most evident in the pure vaudeville of the trio of lipsynching divas who banter their way through a pre-show make-up ritual. In this sequence, the company’s finely tuned choreographic timing was effortlessly transferred to spoken word as their glorious gossip and idiosyncratic turns of phrase brought gales of laughter particularly from members of the Samoan community in the audience.

But behind all the laughs is a commitment to communicate the paradox and complexity of contemporary Polynesia not only through the clever narrative through-lines but also the performance’s choreographic range. The energizing high pace vitality of Polytoxic’s signature style is all the more alive silhouetted against the banal Hollywood rock-a-hula and MTV shimmying. While grounded in a contemporary bass beat and a lot of street style, Polytoxic’s choreographic attention to detail is evident in hand movements and here they often take centre stage: from traditionally inspired finger flourishes evolving from the ordinariness of pegging out clothes to erotically charged hand tableaux (those immoral night dancers again) framed by the porthole sized windows of the simple but inspired set.

Polytoxic happily take the piss out of the touristic and exoticising impulse but crucially give something in return—providing insight into the realities beyond the postcard grin. Fa’alafi, Fa’anana and Shelton are, as always, simply great to watch. And while the performance may be a shade too long, their invigorating style makes their “Polytoxic loves you” by-line so apt. It was clear the audience wanted to say, “Right back at you.”

Polytoxic, Teuila Postcards, creator-performers Efeso Fa’anana, Leah Shelton, Lisa Fa’alafi, Polytoxic in association with Strut and Fret Production House for the Afrika Pasifika Festival; Brisbane Powerhouse, March 18-19

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 35

© Mary Ann Hunter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Upon my initial reading of Nigel Helyer’s “Sound arts and the living dead” (RT 70, p48), I was outraged at his complete lack of understanding of the laptop performances he so confidently criticized and so I casually dismissed his comments as ignorant and self-important, as I imagine many of my fellow laptop performers and improvisers did. However, upon further reading and discussion, I am compelled to reply, feeling that despite its verbose and at times unfounded arguments Helyer’s article does, at its heart, touch on some very interesting and important issues.

“Sound arts and the living dead” opposes what Helyer sees as a historical revisionism of recent years that posits laptop performance as ‘sound art’ at the exclusion of any and all other artistic explorations in sound, be they radiophonics, installation or the sound sculptures he himself produces. Helyer’s own practice has demonstrated an extended, and committed, interest in the sounding of objects, which may go some way to explaining his complaint against laptop performance and what he describes as its “profound level of banality.” Certainly few would argue the banal nature of the laptop and its use in performance—as Helyer points out, “personal computers are now as ubiquitous as the Singer sewing machine in the mid-19th century.” However, is it not equally valid to argue the banality of the guitar as an instrument of modern music?

Laptop performance should indeed be recognised as banal, and purposely so, but this banality cannot be explained as the result of a complete disinterest in performance or commitment to the acousmatic. Laptop performance does not exist entirely in the French acousmatic tradition, as Helyer observes. Instead, it fuses these traditions with those of popular music and more conceptual artistic traditions. Laptop performers exist as workers of ambiguous responsibility who traverse a liminal space between the roles of musician, DJ and artist.

With its banality of instrumentation, coupled with a conscious absence of gestural performance (which itself is contradictory and inevitably incomplete), laptop performance exists as a paradox, presenting an ephemeral space of sounding, grounded neither entirely in existing languages of popular musical performance, musical avant-garde nor more established artistic conventions. As such it sits uneasily between art and music as a discipline, accepted fully by neither, and instead often functioning as an exclusive sub-culture, to its own detriment.

Helyer’s problems with the form arise from what he sees as “an alarming fog of amnesia that obscures the recent archaeology of sound art and sonic performance”, allowing a “hijacking of the term sound art…and its repurposing as a synonym for laptop electronica.” And perhaps this is to some extent due to the exclusivity and isolationism I’ve mentioned as common to laptop performance. However, in constructing his argument Helyer makes the patronising assumption that those involved in cultures of laptop performance are somehow ignorant of histories of exploration in sound, citing examples such the Futurists and Luigi Russolo’s text The Art Of Noises, as well as snidely suggesting younger artists are unaware of William Burroughs, or for that matter that it was Burroughs who initially claimed “language is a virus” and not Laurie Anderson.

Most laptop performers are in fact unusually knowledgeable when it comes to histories of sound and music. And in fact many of the laptop performers in Australia have passed in recent years through the newly established university degrees in electronic and media arts now so popular at institutions such as UTS, UWS, COFA and RMIT, in which they are commonly taught art and music theory side-by-side and emerge well aware of both histories. Prior to this it seems most identified as either sound artists or musicians. However these are boundaries that remain undefined and now seem irrelevant as we acknowledge the work of artists such as Russolo, Burroughs and Cage, in which all sound stands approachable as music, and indeed all music is recognizable as sound.

Far from claiming ‘sound art’ as their own, many laptop performers prefer to consider themselves musicians or, more commonly still, retreat from the argument with mumbled comments that they just work with sound. The use of the terminology ‘sound art’ to describe performative and, frequently, quite musical sound has been championed by publications such as RealTime in an attempt to theorize an inherently elusive art form. Rather than exposing the failures or pretensions of laptop performance, what Helyer’s article highlights is a disjuncture that has emerged in Australian sound culture in recent years in the form of a generational split between older artists who have commonly worked either in the field of ‘sound art’ or music and younger artists who are now emerging in a field where the two seem almost impossible to distinguish.

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 31

© Ben Byrne; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

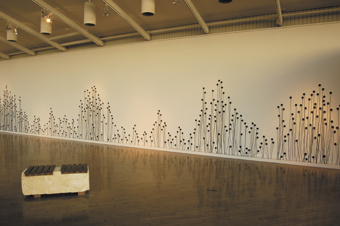

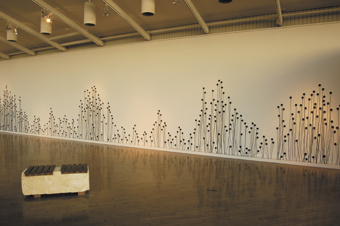

The North Melbourne Meat Market is a gracious Victorian building with a vaulted timber ceiling, wrought iron ornament and cobbled floor, part of both local heritage and contemporary culture. A huge open room that a century ago was filled with spruiking butchers haggling with buyers beneath laden meat-hooks is now filled with a hundred seats, lighting batons, projection screen, imagery of a silhouetted city and a PA—a site appropriate to performance with a viscerally urban edge.

Most of Concave City’s 7-work program is for composite art forms, including 2 works for musicians and video. Biddy Connor’s Sleep Won’t Help (2006), for clarinet, trombone and bass clarinet accompanies Kirsty Baird’s montage of old black and white footage of women in lavish costumes dancing in a humorous parody of burlesque. The video’s soundtrack of recorded laughter is morphed, serialised and segued into the score, the clarinet emitting a staccato laughter before moving onto a lyrical, narrative line. The trombone’s mournful, evaluating speech, precedes an accelerating march tempo that mocks the dreamy, lighthearted imagery. The nostalgia of Connor’s work contrasts with Arnoud Noordegraf’s Netherlands-produced 15 minute video Pong (2003), a delightfully surreal comedy depicting a man’s descent into insanity, which is quietly accompanied by Linda Kent on harpsichord.

Wally Gunn’s The Hive (2005), for viola, percussion and pre-recorded audio, evokes the 3 complementary identities of drone, queen and worker as a metaphor for industrial society. Less metaphorical but equally potent is Kate Neal’s Dead Horse 1 (2005), which opens with a driving jazz rhythm that alternates with moody rumination, plenty of contrasting colour and drama; a work suggesting the influence of composers David Chesworth and Frank Zappa. Neal’s scoring for a highly amplified ensemble of strings and electric bass and guitar captures the intensity of contemporary life.

Two works for larger ensembles, though contrasting in mood and style, are Anthony Pateras’s Fragments, Splinters and Shards (2006) and Brett Dean’s Etüdentfest (2000). Pateras’s dramatic, textured work, the longest of the evening, is for computer-based audio with viola, trombone, recorder and percussion, including some uniquely original instruments. Brett Dean’s Etüdentfest (2000) is an eloquent and mature piece for a more conventional ensemble of strings and harpsichord, opening with a moto perpetuo motif that recurs throughout. The writing is balanced and measured, building to a climax through high pitches before decaying and rising again.

The evening’s finale, Kate Neal’s Concave City & A Love Story for Two Cars (2006) is the show-stopper. In the open space between the string orchestra and the audience, 2 cars drive in, one gently crashing into the rear of the other. Two traffic-weary drivers emerge to confront each other and begin an intense, agile and at times erotic dance in, on and around the cars. The miked sounds of slamming doors, indicators and windscreen wipers form part of the score. The excellent dancers—Lima Limosani and choreographer Anton—portray frenetic urban life with power and energy, supported by Neal’s evocative composition for strings. This collaboration is the most effective and powerful blending of media in an innovative concert for the 2006 Arts House program.

Dead Horse Productions, Concave City; Arts House, North Melbourne Meat Market, Feb 10-11

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 30

© Chris Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

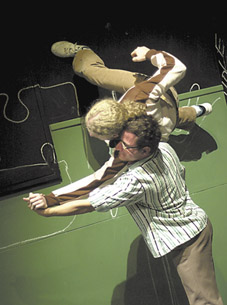

Devolution

photo Chis Herzfeld

Devolution

One hundred years ago, when Isadora Duncan was envisioning “the dance of the future”, she turned her body towards nature and moved with the rhythm of the wind and the waves. Duncan’s ecological choreography for the new century of liberation fuelled many an unburdened, barefoot dance, all free-flowing limbs and gravitational flow. Yet her cosmic view of nature’s rhythms was an enchanted 19th century romance. The futurists with their militant manifesto for arts violent and mechanic were gathering in the wings.

A century later, dance is a high-tech, futurist affair. Two works at the 2006 Adelaide Festival—Nemesis from Random Dance (UK, 2002) and the Australian Dance Theatre’s new work Devolution—choreographed dancers with machines and moving images on screens to digital audio scores.

The convergence of biological bodies and digital technologies is a frontier for innovation. Live performance has long served up its flesh from within a carapace of stage technology. In these new works, the techno-exoskeleton converges with the performers’ flesh on stage. Yet amidst the biotech convergence of 21st century dance, I sense how Wayne McGregor (Random Dance) and Garry Stewart (ADT) have both retained a fondness for the human body and a fascination with the natural world.

The envisioning of nature in these works trades Duncan’s cosmic vision for the minute and microscopic. The strange ways insects move—with their crisp and crunchy biomechanics, their swiftness, swarm and buzz—are traced across the choreography of both works. At times in Devolution, Stewart’s choreography recalls the movements, stranger still, of plants and protozoa.

The works are elegiac in their evocation of the human body. Gina Czarnecki’s meticulous video work for Devolution manipulates fragments of moving human flesh and flashes of X-ray skeletons. These video images, interspersed throughout the work, invoke prehuman memories of cellular splitting and ghostly after-images of bodily remains. They are haunting representations of emergence and dispersal from the past.

Nemesis

Digital video delivers humanising evocation in Nemesis as well. Ravi Deepres and Luke Unworth have designed a video montage that builds slowly, layer upon time-lapsed layer, with images of the dancers—frozen into poses of exhaustion, anguish and ennui—in the drawing room of an abandoned house. This recovered memory gives retrospective location to preceding segments of choreography accompanied by enigmatic images of other rooms from the house.

McGregor’s choreography for Nemesis is architectural and geometric. Dancers’ limbs extend along the cardinal directions outwards from the torso—back then forward, down then up, left then right. Their shoulders and their hips articulate the destinations of their limbs. Each move is plotted with the precision of a coordinate within a 3-dimensional grid.

Dancers enter, walk and wait. They dance solo and with each other in pairs and trios—lifting, leaning, carrying, placing. Their costumes are neat shorts, singlets and long-sleeved tops in grey and yellow construction colours. Their trajectories are adjacent, though their relations are indifferent. The floor is lit by Lucy Carter with architectural patterns; windows, circles, shafts of light and then a grid give structure to the dancers’ positions and progressions.

Scanner’s audio score for Nemesis builds from rattles, squeaks and breathy winds to ambient chirps and vocal echoes and rises to rhythmic intensities with metallic machine percussion and techno-synth progressions for a fiery ensemble sequence. The house burns, the dancers disperse. And then we are transported—or abducted.

A dancer crawls on stage and then another. Their body-suits are cockroach-black, their arms distorted. Jim Henson’s Creature Workshop designed spikey, flesh-stripped, arm prostheses which flex and flick like insect claws. Orange hexagons tessellate the floor as more dancers enter flicking claws. An insectoid sci-fi combat scene ensues. McGregor’s prosthetic interest in extension recalls ballet’s derivation in fencing.

McGregor dances a final solo scene between 2 see-through screens: a slug-like crawl, a parasite, a worm, while animated centipedes chase each other around the screens. Four years old, the screensaver-like animation shows its age and fades. An online animation records the Nemesis sci-fi game aesthetic (www.randomdance.org). Its robotic insects, honeycomb grids and fine-line text click through to audio loops and low-grade video of the dance.

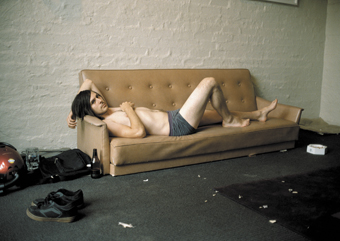

Devolution

In comparison with Nemesis, Stewart’s choreography for Devolution is fractal and organic. It grows and oozes, unfurls and folds, flips and flows. The dancers are dressed armadillo-like in layered leather skins by Georg Meyer-Wiel and they move as if by feeling, without the aid of sight.

Their heads are often down, their faces turned away. Their arms curl out, a leg folds up. Sometimes they are rooted, fixed like tripods on the spot, supported on 2 knees and an elbow, 2 feet and a hand, 2 hands and a head. At other times, the dancers travel in a pack, with arms and legs entwined and overlapping. Three pairs dance a sequence mouth-to-mouth. A man is left to dance a solo, angular and naked, but not alone.

Waiting in the wings and suspended from the rig are Louis-Philip Demers’ robots which stumble, trundle, scatter in to survey the scene. Unlike the dancers, these mechanical monsters have searching eyes—spotlights that transfix the dancers in their gaze. They intrude upon them and impinge upon their space. The dancers cower and sink beneath the awesome rudeness of the robots’ presence.

The robots’ moves are cumbersome, and sometimes cute. When it’s quiet, we can hear them creak and breathe. But when composer Darrin Verhagen’s clunking, churning industrial score lends aural power to Demers’ machines, we are witness to the mechanical choreography of terror. We hear bones crushing and flesh tearing. The dancers shrink in fear.

A robot drags a dancer across the stage and drops him. Machines attach themselves to dancers, as parasitical appendages that pulse upon the dancers’ bodies with their piston push and shove. As the end approaches, the stage is electrified with action, robots agitated, lights flashing, bodies pulsing. And then a screen descends. The final video is of a clustering of human flesh, shrinking, fading, disappearing. In the curtain call for Devolution, as if to reassure us, only the human performers lined up for the applause.

–

Australian Dance Theatre, Devolution; Her Majesty’s Theatre. Adelaide, March 3-7; Random Dance, Nemesis; Dunstan Playhouse, Adelaide, March 15-18

Interviews RT 71, p 2 & 4 for interviews with Garry Stewart and Wayne Macgregor.

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 32

© Jonathan Bollen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Forsythe Company, Three Atmospheric Studies

photo Shane Reid

The Forsythe Company, Three Atmospheric Studies

The dancers line up along the back of the stage. We quickly become silent. A woman and a man walk forward beneath the low hooded lights, she further than he. She contorts her body (or does she only point at him), and says: “the night my son was arrested.” His body is frozen (maybe an arm is folded over his head, his body screwed away from the audience). She walks off. And the battle begins. This is how I remember it, and I’m sure I’m wrong. And being sure is a poke in the eye about witnessing, about reporting (telling what was), and the impossibility of that, even while feeling the pleasure of telling (tales). Telling is a freedom, a fragment of freedom, and that’s what we were watching—the fragment’s brief and discontinuous circumstance.

The ‘battle’ is an endless round of violent encounters, so finely worked out that while one contemplates the improvisation of street/gang brawls, one is also amazed by the formations of the body as it fights, and the permutations of bodies as they tangle and untangle, and the timing needed to ‘get-the-job-done’ and to keep the job coming, to prolong and inflame the situation. Then a pause, a still image; the eyes rest upon a moment. It is familiar; we’ve recently seen it on the TV from Cronulla for instance, and we’ve seen it in films; we know the moves and the perpetual energy. It can go on and on, and that’s alarming; and as the bodies physically tire they become sound—gasping and grunting floats to our ears, not by dramatized force but by the real-time exhaustion of the dancers. Sound becomes dance; and sound, as much as narrative, sets up the next 2 atmospheres—compositions 2 and 3 of Forysthe’s Three Atmospheric Studies.

Giving evidence while trying to work out what happened is the atmosphere of the second composition, Atmospheric Study 2, which itself has, language-wise, several compositions to deal with (nothing is straightforward). The woman who tells her story—how she saw what happened to her son (the one arrested)—thinks she’s in composition 1, but composition 2 comes to bear upon her story and its recording, and then composition 3 does too. There are fine white threads taut across the stage, sight-lines (of fancy). She tells her story to a translator who repeats it in (is it) Arabic, transposes more like, replaces one word with another. (We know this as another man intent on describing a painting—the atmosphere of a painting, maybe a painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder, several of which have influenced the work). She asks the translator for the word for ‘bird’, but unfortunately the translator only has one for ‘aeroplane’, and so forth. It’s too late anyway for the woman, who in a hysterical/convulsive ‘state’ twists her body and voice in a horrible display of grief. The trouble is it disturbs nothing/no-one in the scene (life goes on). The translator watches passively, the other man keeps on ‘painting the picture.’ Forsythe has said, about the state of the war-state (world-wide): “Nothing changes. In several hundred years … nothing changes” (The Age, March 10).

And then, after a break, the third composition/atmosphere. A man begins to tell us about a photograph (perhaps it’s a fragment of the same painting in the previous atmosphere) of clouds, but more about the relations between parts, the ‘over-there’ and the ‘over-here.’ The event/bombing unfolds, the whole disaster. Amplified treated voices are wrenched through bodies, flesh slams into the set—a wooden structure wired for sound—and people curl into odd shapes, mutilated. A woman, our woman from atmosphere/composition 1 and 2, is now silent and passive while a sensible man/woman, in charge, at ease with the disaster explains it; it is all necessary and for the greater good, there is no other way, the sense of it is obvious (can’t you see that?), and s/he’s come ‘all this way’ to address just/you, to reassure just/you. Nevertheless, our woman rightly, in his/her presence, quietly dies. Meanwhile, the cloud-man has given us a tour of bits of bodies, buildings, and belongings catapulted (from over-there to over-here) into the scene.

The atmospheres are variations, continuations, escalations of the one atmosphere; glimpses, sections, diagrams, architectures of ruin embedded in live/dead beings. There is no lesson here, that’s the blessing. But there’s also no reluctance to ‘speak’, to make fury in the face of the permanent disaster; to make new problems, not take up those of the ‘authorities’—whoever they are, however they appear. Forsythe’s work is dark (darker and less abstract since I last saw it), his choreography confronts language, it pushes language outward, like the world—making matter that it is. This is difficult to achieve as language at every turn (having a life of its own) can trip itself up (be too readily sweet or bitter). It must be small and tight to keep its nerve, to know what it’s doing (and even then it goes to pieces) with sound and affect in the listening world.

Atmosphere is pervasive, it’s never this or that; rather, it’s this and that and multiple relations of infinite ambiences and densities. And it was so in Forsythe’s Three Atmospheric Studies; you had to choose what to watch and hear; to change focus was to forfeit this thread for that thread. You could not witness it all, you could not tell the whole story afterwards, only what you thought you had seen. One is unreliable like the next person, no amount of effort will ensure the truth. That’s the strange dilemma of telling and re-telling, of having the insolence (taking the uncool Forsythe risk) to ‘speak of it.’

To make a work that functions equally on several performing registers—movement, theatre, sound, voice, design—with edges of humour, intellect and poetry as well as a politic that knows what it hates, requires an ensemble of skilled dancers who are more than dancers. Timing was critical, delicacy was exquisite, and the heavy hand of ‘what it means’ washed throughout yet never erased actual endurance (on the plane of real-life, and on the plane of ‘I love to dance’ in a field of utterance—sensation). Here, more should be said about the company of dancers and about individual dancers (and about William Forsythe), but the work’s power is at the limits of these; it resides in what seems a philosophy of dance, that as time, in time, is a sort of simultaneity of realms.

The Forsythe Company, Three Atmospheric Studies, choreographer, William Forsythe; Festival Theatre, Adelaide Festival, March 12-16

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 33

© Linda Marie Walker; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

From out of the dark, to the anxious sounds of accelerated scribbling, tearing and tense breathing, emerges a quivering Fiona Malone, tightly framed by light, close to but looking through us and anxiously into herself. The torso twitches, the arms hang and jerk. A tunnel of light opens behind her. She backs along it, pieces of torn paper falling from her mouth. She is revealed again, collapsing into herself in a small square of light. Now she appears stretched out, trapped in a coffin of green light, twitching the length of her long body, arms momentarily floating, rigidifying. She reappears, half-stooped, moving towards us, almost confident, but the arms are now defensive, as if brushing something away, her head up, then down amidst oppressive crowd noises and metal raspings. In the sudden dark there are cries and crashes as her body hits the floor. In a rectangle of low light she writes with chalk on the floor, her body sometimes a template, but erasing patterns and words as she drags herself across them. For a while she looks free and fluent (even if the expression of it seems to come to nothing) and then tense as she struggles to write on her skin. Voices fill the space, speaking of loss of control and self-destruction. She erases, she writes again, she falters, she cannot bring the chalk to the floor, her arms flail about her. A spot glares from the distance, silhouetting a half naked Malone moving freely. The light then opens out into a low unbounded wash of colour and as the dancer nears us, patterned symbols form and glow on her flesh.

Fiona Malone, Reticence

photo Heidrun Löhr

Fiona Malone, Reticence

This is dance as interior monologue, where thoughts and feelings have to be read from the performer’s body (save for the one cluster of rather literal voice-overs). And what we read is anxiety about self-expression, the struggle to record or to dance it (a deliberately limited vocabulary of taut, small gestures and moves, like a body blocked). In the end, comes the recognition that all this is already written, in and on us. In this measured, nervy work, Fiona Malone displays a consistency of tone and a careful development of theme, sustaining a demanding state of being. There are occasional longueurs where small moves seems to express little (Malone stretched out in the rectangle of green light), frustration for some over the opacity of what is actually written, and a desire for the choreography to be more expansive, a little more shaped. Known for her engagement with digital technology in other works, Malone here choreographs on herself an almost animated persona, building an image from one or 2 parts of the body and small gestures, until we get the whole picture.

Kay Armstrong, a.k.a

photo Hedirun Löhr

Kay Armstrong, a.k.a

In a.k.a. Kay Armstrong appeared as entertainer in various modes across the evening: greeting us in the courtyard with glittering top hat, quips and little magic tricks; chatty dancer loaded up with professional gear like artist-as-bag-lady; dancer recalling flamenco hand moves, deftly delivered in long corridors of light, but stamping only to flatten a beckoning pack of cigarettes; and failed stand-up comic, desparate to please. Coming from the artist who gave us the powerfully performed and constructed Narrow House (RT 61, p48), this was light fare, and not enough of it written by the body.

Liz Lea, DhIVA

photo Heidrun Löhr

Liz Lea, DhIVA

Written into Liz Lea’s body are multiple histories and cultures of dance displayed with great precision, furious energy and a strength you can feel through the vibrating floor in DhIVA, choreographed by Canadian Roger Sinha. Like Malone, Lea too suggests hesitancy, intially rocking in a reflective mood on a chair before springing into action, or pausing her vigorous dance to declare, “I’m a…I’m a…” But such inarticulacy is strictly temporary as Lea flies into action. Here it’s dance as essay, informed by observations about contrasts between the Western and Eastern dance languages her body so eloquently speaks, the hybridity of ballet (its absorption of European folk dance presented here with hilariously overwrought gusto), and a commitment to Indian dance in particular.

Onextra, Solo Series #2, Fiona Malone, Reticence, lighting Clytie Smith; Kay Armstrong, a.k.a, lighting Clytie Smith; Liz Lea, DhIVA, choreographer Roger Sinha, lighting Karen Norris; Performance Space, March 16-26

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 34

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

New forms, connections, networks

RealTime 72 is rich in reports of new forms, new ways of engaging with audiences and of making new connections—between media platforms, between performance niches (as the contemporary performance touring network in Australia grows), and between nations at the Inbetween Time festival in Bristol.

John Bailey reports on recent performances in Melbourne that stretch form in new directions, making fascinating, sometimes challenging demands on their audiences (p41). As he outlines the D>Art.06 program, David Cranswick, director of Sydney’s dLux media arts, describes the blurring of media platforms and the flexibility of delivery therefore available to the makers of short films and animations (p26). Gridthiya Gaweewong, co-director of the Bangkok Experimental Film Festival tells David Teh about the festival’s innovative approach to programming and screening (p22). Karen Pearlman reviews the finalists of the 2006 ReelDance Awards for Best Australian & New Zealand Dance Film or Video, looking at the continuing challenge presented by the dance/film dynamic (p23). Jonathan Bollen (p32) and Chris Reid (p27) report from the Adelaide Festival of Arts on the impact of robotics integrated into dance and sculpture. Christy Dena attended the Digital Storytelling Conference at ACMI in Melbourne where the multiplying multimedia means of telling were in evidence, much of it online for you to follow up, with some impressive sites in Wales, Canada and the US (p28).

Contemporary performance in Australia has received a much needed boost from the establishment of the Mobile States touring consortium, Melbourne City Council’s Arts House and its Culture Lab program, Performing Lines’ continued support of innovative work, and the Sydney Opera House’s programs in The Studio and now in Adventures in the Dark. Adventures… offers a year-round international program of performance that will expand the local vision of what can be seen outside the usual arts festival context. There are now an increasing number of venues across Australia ready to take on contemporary performance and dance. Keith Gallasch surveys these developments on p38-39.

The invitation to run a review-writing workshop on hybrid art practices at the Inbetween Time festival allowed RealTime’s editors an excellent opportunity to see and discuss new British work, especially in the areas of Live Art, installation and digital media. Inbetween Time proved an idiosyncratic festival, offering audiences all kinds of access and engagement which they took up with enthusiasm (see full Inbetween Time online covereage), suggesting the direction that arts festivals of the future may well take.

Just as opportunities are slowly opening up for performance to tour Australia, cultural exchange between Britain and Australia looks set to expand. Performance Space and Arnolfini are playing a key role in this development through their Breathing Space program which this year featured Australian artists Monika Tichacek, John Gillies, Martin del Amo, Deborah Pollard in Bristol and at Breathing Space partners, The Green Room in Manchester and Tramway in Glasgow. Other Australian artists Lynette Wallworth, George Khut and Rosie Dennis were also featured in Inbetween Time.

The reciprocity evident in these exchanges is vital to their future. Wendy Blacklock, director of Performing Lines, believes it obligatory for the future of performing arts touring. D>Art.06 includes a focus on experimental film and video from the Middle East and also has invited filmmaker Akram Zaatari to the festival. By coincidence, Zaatari is one of the artists selected by director Charles Merewether for the Biennale of Sydney’s Zones of Contact, a great gathering of artists, many from the developing world.

Next

RealTime 73 will feature more from RealTime’s UK visit, including a report on the National Review of Live Art (NRLA) in Glasgow, FACT in Liverpool and Cornerhouse in Manchester. There’ll be a special focus on East London where we visited Rich Mix, a new centre for British-Asian art with a strong social agenda, and a re-vamped LIFT (London International Festival of Theatre), directed by Angharad Wynne Jones with a vision blending the local with the global. Both ventures reflect needs and conditions in the East End, and both are planning for intensive participation. In the same East End we visited the Live Art Agency and Artsadmin to discuss the unique roles they play in the nurturing and dispersal of contemporary art. RT

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 1

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Spaghetti Club, outside Arnolfini

photo Mark Simmons

The Spaghetti Club, outside Arnolfini

Located on the rapidly transforming old docks of Bristol, Arnolfini is a handsomely refurbished and busy contemporary arts centre replete with multiple gallery and studio spaces, theatre-cum-cinema, impressive bookshop, reading room and café. Arnolfini’s Inbetween Time Festival of Live Art and Intrigue proved to be an accessible, adventurous and marvellously eccentric event, prototyping a new kind of festival in which the real and the virtual blur and, above all, audiences enjoy new kinds of engagement with artists and artworks. Not only does interactivity take many shapes, digital and personal, but audiences also witness at close quarters the formation of new works.

Outside the building an old, red double decker bus, the Spaghetti Club, stood by the water, providing an all day gathering point for artists and audiences to gossip and critique, while the café was packed and the reading room in constant use. A short walk away, the L-Shed provided more gallery space. Across town, the University of Bristol’s Wickham Theatre and The Cube hosted a variety of performances.

Interaction

Large numbers of the public streamed into the This Secret Location at Arnolfini and the L-Shed, a free exhibition of works exploring the interplay of the real and the virtual. Here they saw their heartbeats and breathing writ large in George Khut’s Cardiomorphologies (Australia); they stretched out between layers of light and sound in Alex Bradley and Charles Poulet’s Whiteplane_2 (UK); activated the flight of clouds of white cockatoos to their night-time Central Australian roost In Lynette Wallworth’s intensely evocative Still:Waiting 2 (Australia); or went it alone into the light and utter dark in Ryoji Ikeda’s Spectra II (Japan). Installations were also busy: multiple screen videos by John Gillies (Divide, Australia) and Monika Tichacek (The Shadowers, Australia) and Deborah Pollard’s Shapes of Sleep (Australia) exhibiting the behaviour of very real sleeping bodies.

In contemporary art, the audience, either alone or in small groups is increasingly becoming an active participant in works of art, triggering events, slipping into immersive sensory experiences, meeting artists one-to-one in structured engagements, or simply following sets of instructions. In Inbetween Time this could range from sharing an elegant lecture-cum-meal of oysters and champagne (later followed by a brief solo visit to see the formerly tuxedoed host, Paul Hurley (Swallow, UK), transformed into a kind of oyster by swathing himself in bacon—an immaculately crafted but slender “angel on horseback” joke); joining in a conversation which is destined not to work (Carolyn Wright, Conversations with Friends, UK); a real kiss which is set in dental plaster (Charley Murphy, Kiss-in-Between, UK); sitting in on a bloody wound fabrication workshop (Uninvited Guests, Aftermath, UK); wandering the streets in headphones alert to the special sounds of Bristol (Duncan Speakman, Sounds from Above the Ground, UK); or finding yourself in a small room with a group of performers who are exploring telephone behaviour for 6 hours (Special Guests, This Much I Know, Part 2, UK).

Performance possibilities

If the public queued for and happily took to This Secret Location and other installations, another audience, often comprising students (in numbers that made us Australians envious) and performance fanciers, packed into the festival’s performance spaces.

Each morning the lecture format would transform as various artists used it for everything from E-Bay Power Selling (AC Dickson, USA), to demonstrations of silent movie slapstick devices (Howard Murphy, A Working History of Slapstick, UK) and robotics (Paul Granjon, The Heart and the Chip, UK-France), and the performance company Gob Squad (Me the Monster, UK) report on their research into fear—seeking out vampires and werewolves in public places.

Grace Surman, Slow Thinking

photo Adam Faraday

Grace Surman, Slow Thinking

Other performances manifested themselves more conventionally at first glance. David Weber-Krebs (This Performance, Germany-Netherlands) turned the stage sculptural; Pacitti Company (UK) contracted us before we entered an intimate space saturated with British myth and history and reflections on our dreams and ambitions in the immaculately crafted and performed A Forest; Rosie Dennis (Love Song Dedication, Australia) seamlessly and bracingly hybridised performance poetry, physical performance and the stumblings of love; Miguel Pereira (Portugal) arranged for selected guests to murder his stage persona; Martin del Amo (Under Attack, with Gail Priest, Australia) wrestled with personal demons and Jacob’s angel; and Grace Surman (Slow Thinking, UK) duetted in surreal role reversal with Nic Green (other performers will work with Surman in other cities).

Big picture

What did Inbetween Time add up to? Whether thematised or not festivals sometimes sum up a cultural moment or epitomise a trend. As I’ve already indicated this was certainly the case with the range of ways audiences were engaged and the many hybrid forms in evidence. Tim Atack thought he detected something: “Being left hanging is a familiar motif in Inbetween Time. The themes of being incomplete, unfinished, beyond rescue or beyond recall seem to resonate through a series of otherwise contrasting works” (“Mortality Manifesto”). The fluidity of audience-performer relations and the easy interplay between the virtual and the real, self and other, body and machine certainly underlined the pleasures, in particular, and anxieties of the age with a new and pervasive intensity.

Creative tensions

The contrast between works-in-progress and complete and tested productions also provided Inbetween Time with a curious dynamic, especially given that the Australian works were in the latter category (Del Amo, Tichacek, Gillies, Pollard). Breathing Space UK counterparts will reach fruition at Inbetween Time 2007. As well, this tension extended to some contrasting aesthetic attitudes which we’ll address in the next edition of RealTime when we look at the extensive Live Art phenomenon, of which there is no equivalent in Australia. An enormous range of work is encompassed by the term Live Art, work which appears to hover between performance art and contemporary performance but is open to many more possibilities. In fact, it is most often described in terms of what it is not. Much of it seems solo, low budget and roughly crafted, with a calculated 90s anti-aesthetic or an air of intellectual burlesque and not a little bovva, but there are plenty of exceptions. It certainly has a strong institutional presence in the form of festivals, the Live Art Agency, New Work Network, Live Art Archive (its new incarnation in Bristol after a relocation from Nottingham was celebrated at Inbetween Time), well-established funding patterns, a strong regional presence, some committed venues and producers, and plenty of opportunities to work in Europe.

The Australian works were much admired, though sometimes described in terms of style, control and polish, while British live art and experimental theatre were seen in terms of conceptual power, a process orientation and spontaneity, which the Australians, in turn, sometimes read as under-conceptualised and under-crafted. The debate continued on our travels to Glasgow and Manchester where the Breathing Space Australia artists also toured, and was enriched by the experience of the National Review of Live Art at Tramway in Glasgow and our meeting with the Live Art Agency in London, more of which in RT 72. From my point of view, these differences were welcome, reflecting how different the artistic milieus are in Australia and the UK, thus making the ongoing Breathing Space exchange program between Arnolfini and Performance Space even more vital for what it offers in debate and, above all, ways of working. These creative tensions ran other ways too, even in live art itself, between younger and older generations of artists, not least in the problems of labelling. In a discussion of the issue of definition, writer Tim Atack commented, “This is a form in which the definitions are always being contested and the ground is always shifting, so let’s leave it at that.”

Thanks

Helen Cole

photo Jamie Woodley

Helen Cole

Above all our thanks to Helen Cole, artistic director of Inbetween Time, for an adventurous festival of the moment and of the future, and one which brought Australian and British artists together in a much needed and ongoing program created with Performance Space. Our very special thanks go to Helen for inviting the RealTime editors to run a review-writing workshop and securing the funds with which to do it.

The workshop was a wonderfully immersive experience with a fine team of 6 writers who committed themselves to a hard task with vigour and good humour, turning out reviews daily on demand. The writers were Marie-Anne Mancio, Niki Russell, Winnie Love, Osunwunmi, Ruth Holdsworth and Tim Atack. You can read their reviews on the Inbetween Time section of this site.

Our thanks also go to Tanuja Amarasuriya and Tim Harrison for making our 2 weeks at Arnolfini friendly, comfortable and efficient. Thanks also go to the Australia Council’s Community Partnerships & Market Development division for additional funds to extend our visit beyond Bristol to Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester and London, as part of the Undergrowth Australian Arts 2006 program.

The workshop has allowed RealTime to meet writers both British and Australian in the UK who will contribute to future editions of the magazine as the cultural exchange between the 2 countries accelerates and intensifies, adding, we hope, a level of documentation, review and debate.

Keith Gallasch, Virginia Baxter, Gail Priest

RealTime-Inbetween Time, Reviewing Hybrid Arts: Intensive Workshop, Jan 30-Feb 8; InbetweenTime Festival of Live Art and Intrigue, Arnolfini, Bristol, Feb 1-5

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg.

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

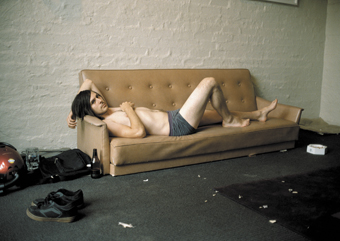

In 2005, Asialink in partnership with the Dance Board of the Australia Council selected 5 Australian choreographers, including Jo Lloyd, to develop new collaborative works in Japan as part of the Asialink Japan Dance Exchange, Neon Rising. In May 2005, Lloyd, Melbourne designer Shio Otani and composer Duane Morrison visited Japan and collaborated with Off Nibroll members Mikuni Yanaihara and Keisuke Takahashi to create Public=Un+Public. Mikuni Yanaihara founded the art collective Nibroll in 1997, a company of 6 directors in the fields of film, dance, music, lighting and fashion producing works seen around the world. Off Nibroll’s work focuses on the relationship between body and image. Public=Un+Public was presented at Yokohama BankART1929 and has now been seen in Melbourne where Lloyd is based and has been building a body of work including Not As Others, seen in the Adelaide Fringe Festival and Next Wave 2006. Eds.

Mikuni Yanaihara, Jo Lloyd, Public=Un+Public

photo Rohan Young

Mikuni Yanaihara, Jo Lloyd, Public=Un+Public

Shown recently in Japan, Public=Un+Public’s Melbourne incarnation was created inside Chunky Move’s Melbourne studio, whose usual box-like dimensions were transformed by Shio Otani into a series of spaces, levels and screens. Two bedrooms at each end were connected by a central sphere, green and grasslike.

The work begins with Lloyd and Yanaihara at each end, in their respective rooms. The screens flanking each room reflect the activities of the other, thereby connecting the women. If this is private space, it’s pretty sparse and depersonalized at best, an external view upon interiority. Perhaps the term ‘un+public’ suggests this, that the private is simply an inflexion of the public. After a series of activities, the women swap ends to continue their individual musings. They are not the same. Yanaihara’s range of emotional textures highlights the secular nature of Lloyd’s boisterous, bouncerly energies.

Takahashi’s accompanying video images undergo simple but mesmeric transformations—silhouetted doorways, interiors framed and reframed; windows upon social, personal space. A crowd of small black figures explodes into what looks like a flock of birds pouring out of a diminishing human form, repeatedly blotting the screen in flying formation. At one point, the width of the room gives way to a single screen, the women leaving us to pay attention to the images. Some beautiful imagery combines with dancing text. Yanaihara was filmed on her bed in her flat (inspiration for the overall design?), the image contracting into the room’s TV, a frame within a frame. A reminder that the realism of video is never more than virtual?

When they returned, Lloyd and Yanaihara interacted in the central space, back to back, back to front, tossing, lunging, swinging at each other, coming together, coming apart. Elements of domination or competition were suggested but nothing was made explicit. A menagerie of shredded newspaper balls were tossed about. Many qualities were explored in this duet, which canvassed a range of relational possibilities. This was the section of Public=Un+Public that appeared the most experimental, a place where the women could have taken the work into another space, beyond its initial dichotomies. My feeling is that more collaborative time is needed in order to fully develop this section, and to integrate it into the piece as a whole. Lloyd and Yanaihara are each strong performers with their own qualities and differences. They clearly have ideas about the work, along with Takahashi’s video projections and Otani’s design structures. If there is an element of cultural difference in the mix, there is also the question of kinaesthetic difference: how to produce joint movement by way of addressing the themes of the whole. This is about the work as performance, rather than installation. In other respects, Public=Un+Public felt very clear, Lloyd’s aesthetic combining well with Off Nibroll’s input and Duane Morrison’s music to create a distinctive and enticing world.

Public=Un+Public, choreography and performance Jo Lloyd, Mikuni Yanaihara, video Keisuke Takahashi, music Duane Morrison with Yuki Kato+Sound Sleep, design Shio Otani; Chunky Move Studio, Melbourne, February 15-19

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 35

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

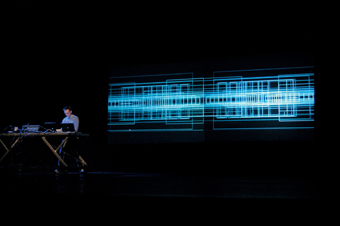

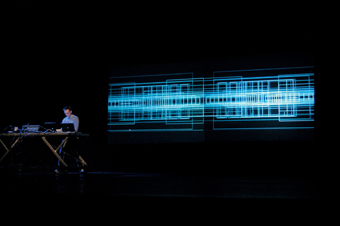

alva.noto

photo Kenichi Hagihara

alva.noto

Calling for a “tuning of the world”, R Murray Shafer was influenced by Pythagoras’ concept of the music of the spheres—the harmonious hum of the universe. But he wasn’t too fond of the overcrowded audio soup that industrialisation and modern living was making of the acoustic environment. While electricity is a natural phenomenon, its technological taming is the foundation of contemporary living and one of the major ingredients of this soup. So I wonder what Schafer’s thoughts would be on Sound+Electricity at Performance Space featuring performances by Carsten Nicolai (aka alva.noto) and Joyce Hinterding, both of whom use this energy source directly to conjure their sonic worlds.

Hinterding has been summoning the hum for quite a few years now. Using large, hoop antennae, she amplifies the under rumble of the electrical grid. It is a warm, caramel sound tonight reinforced by the projection showing 2 mirrored ovals of a flowing bronze substance. Hinterding’s work is meditative, the shifts of tone minimal and incremental. At some point it becomes a duet as lighting designer Richard Manner subtly brings up dim squares of light, shifting the intensity and pitch of the drone. For those of us who have spent considerable time trying to eliminate interference between lighting and sound systems, this is a perversely pleasurable moment. Patience is rewarded with the development of crackles, pops and fizzes fringing the bass tones marking the climax of the work. At its end, there is both relief and a hint of loss plus some very strange flange effect filtering the foyer voices for the next few minutes.

In contrast to Hinterding’s slow flowing release of electrical energy Carsten Nicolai’s sound consists of tightly controlled punctuations and calculations. Nicolai describes his work as “atomising…Every particle carries the same information as the bigger object it came from…a kind of micro-macro thing” (Wire 238, Dec 2003). In this performance each sound element—spit, spark and sputter—is perfectly crafted, a glistening glitch. When these particles combine, the whole becomes an intense, vibrating composition of intricate syncopations. Accompanying the sound are synaesthesic visuals of blue lines snapped to a grid, directly emulating the intersections of audio. These form strict geometries, like insanely complex architectural drawings in constant states of redesign. The entire effect is as physical as it is mesmeric. The rhythmic entwinings create primal pulses and cool melodies which entice the body to movement. Why are we sitting in concert mode? We should be dancing!

This was perhaps the most intriguing aspect of Sound+Electricity. alva.noto is an artist who manages to bridge the esoteric and the accessible. The audience comprised elements of the local sound crowd but the larger proportion were newcomers to this kind of sound event. Of course alva.noto has international appeal but are many here aware that there is also a vibrant experimental scene happening in nooks and crannies around Australia? Hopefully Sound+Electricity not only tuned us in to our contemporary audio ecology but also to the potential to expand the audience for experimental audio.

Carsten Nicolai (aka alva.noto), Joyce Hinterding, Sound+Electricity; Performance Space, March 12

Carsten Nicolai was presented in association with the Adelaide Festival of the Arts and forma UK.

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 31

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Needcompany’s Isabella’s Room

photo Maarten Vanden Abeele

Needcompany’s Isabella’s Room

Peter Brook loomed large over the 2006 Perth Festival. Brook mastered a ritual, story-telling frame to bind together “a little of this and a little of that”—theatre for “the brunch eating class”, as The Nation put it. He helped establish a ‘fringe on Broadway’ style, mixing elements of dance, mime, opera, physical expressivity and text which distilled elements of avant-garde dramaturgy into rich flavours within more traditionally acceptable narrative or character based formulae. Canadian director Robert Lepage is Brook’s peer and heir here, a revival of Lepage’s La trilogie des dragons (1987) headlined at the festival.

Dragon Trilogy

A sparse, plastic scenography supported Lepage’s epic scope, offering 3 snapshots of interconnected lives in different cities populated by French-Canadians, Canadian-Chinese, Canadian-Japanese and Anglo-Canadians, their families, and star-crossed lovers. The opening established the tone: 2 Francophone girls recreate their neighbourhood using shoeboxes laid out on a rectangle of gravel (Brook’s proverbial “empty space”, pregnant with potential), bounded by a concrete path along which bicycles, scooters, wheelchairs, wheelbarrows and skaters later zoom. Lepage uses this dialectic between centre and periphery in conjunction with that between fast and slow to alternate between scenes of quiet, centrally located contemplation or intensity, and those later encircled and rendered storm-like by multiple figures rushing about the edges.

Lepage’s now venerable show was remarkable for this effortlessly controlled use of space. The director remains however an unreformed Orientalist. Spectators learnt almost nothing about the Asian characters who ‘featured’, only about Canada’s projection of itself and Lepage’s vision of spiritual redemption through interaction with such outsiders. Orientalist clichés ranging from the opium addled, gambling Chinaman to the avaricious white-slaver abounded. Even Madama Butterfly was uncritically (and implausibly) relocated to US occupied Okinawa. Brook himself brushed aside cultural difference as largely irrelevant, and any dramaturg like Lepage who still quotes with approval “Antonin Artaud saw theatre as Eastern” must be viewed with suspicion by those of us critical of Western fantasies about the ‘mysterious East.’ Nevertheless, in reminding one of the scenographically and performatively expansive modes underpinning popularly successful epic works from The Mahabharata (1985) to Angels in America (1991) to Susie Dee’s Tower of Light (Melbourne, 1999), Lepage’s theatrical skills yield deeply moving work.

Chronicles—A lamentation

Although Polish company Teatr Piesn Kozla developed their expressive style from Jerzy Grotowski and other sources, Chronicles—A lamentation recalled Brook’s gently lulling, melancholy rituals more than Grotowski’s intense and abstracted Catholic mysteries. Amidst earthy hues, unpainted wood and brown costuming, 7 performers sat or stood in an otherwise empty space, each word, musical lament and exhaled expression directed at the audience as they rolled their weight from foot to foot like boxers or capoeira dancers. The Albanian and Polish text was sung in the polyphonic style popularised by the Mystère des voix bulgares CDs. In Edinburgh, spectators were given printed translations of the show’s text, but here the narrative was simply vocalised, demonstrating the error of Brook, Grotowski, Herbert Blau and others. Throughout the 1970s, artists claimed to isolate universally embodied forms of human expression. That Chronicles failed to communicate illustrated their mistake. The performative emphasis on actors speaking at the audience meant that Chronicles functioned as an intriguing collection of physical hieroglyphs which, while designed to have dramatic content, remained opaque to most Perth spectators.

The Drover’s Wives

Though far from Brook and Lepage, The Drover’s Wives also sustained a tension between abstraction, history and narrative. In director Sally Richardson’s dance theatre piece, 5 performers depicted the stories of 2 turn-of-the-century women abandoned by their husbands in the bush. The choreography mixed overt mime (hanging washing, etc) with simple, unison dance. The movement truly shone, though, when a dark sense of abstraction took over. In Richardson’s rendering of Barbara Baynton’s story from The Chosen Vessel (1902; Jonathan Mills’ source for his opera The Ghost Wife, 1999), an unseen swagman raped 1 of these women. The others transformed into beastly presences, on all fours with shoes on their hands, their stomping, leather-shod limbs menacing the wife before she was encircled by tree stumps, as though the very bush itself was attacking. Iain Grandage guided the show’s trajectory, his mildly Sondheim-esque score recalling Lennie Niehaus’s for Pale Rider (1985) and Unforgiven (1992) in its rhythmic combinations of folk instrumentation, strings and cut-down orchestral motifs. The Drover’s Wives was another popular work which frayed under intense scrutiny. Ostensibly an exploration of feminine isolation, the ensemble work rather suggested an oscillation between individual loneliness and feminine community, of women coming together to share domesticity and spatial play. It was moreover not clear why, of the 5 dancers, 2 played specific characters. Who were the other 3? Aspects of the first 2? Finally, the radically different sense of cultural space—and that of the stage design itself—as one moved from bright, projected landscapes of the inland plains to dense, dappled ironbark forests, was not explored. Nevertheless, the broad scope of the production and its sense of light engagement made for stimulating viewing.

Super Vision

Compared to the antiquarian neoclassicism of Chronicles, the Builders’ Association’s Super Vision glistened with modernity. Using digital projection, director Marianne Weems offered 3 sketches dealing with the transmutation of identity via computerised data: a New Yorker helping her Indian grandmother to archive and identify photographs from her life; a man using his son’s name to evade mounting debt; and an Indian-Ugandan repeatedly stopped by US Customs. Images of the son and live close-ups of the other performers were projected onto translucent screens effortlessly sliding in front of the main stage. Behind the performers curved a space bearing the projected sets. The intricate digital designs were laid on black in blocks of line, colour and text reminiscent of the London Underground map. Sound and music underscored the performance, the use of bird calls as an abstract, vaguely digital aural signature echoing Stories From the Nerve Bible (1992) by Laurie Anderson and Brian Eno. Like much slick, postmodernist performance, the scenography and music gave the piece an oddly dated ambience—very mid 1990s, a production buoyed by the sharp rise in interest in the internet and new technologies which has yet to abate. Super Vision was more impressive in form than content, Weems contrasting the strangely flat sense of glossy ecstasy sustained by the efficiency of her onstage technology with ambivalent, mildly dystopian narratives. Even the father’s attempt to flee beyond technology to the Far North seemed borrowed from Anderson’s tale of setting out for the North Pole. A particularly perspicacious narrative detail though was that the traveller was initially identified as a security or health risk because of his racial and geographic origins, but was eventually given a royal welcome once his prosperity became apparent. In contemporary global capitalism, class can trump race. (See also Kate Vickers review on p27.)

Isabella’s Room

Alongside such supremely proficient, crafted works, it was Needcompany’s Isabella’s Room which provided challenging aesthetic defamiliarisation in its radical objectification of onstage materials. Director Jan Lauwers mixed an easy, off-hand performativity with dense allusions. Twentieth century history and life became a room, a clutter of objects and people. Characters died during the narrative, but did not leave the stage. The past remained.

The conceptual centre was an assemblage of African and Middle Eastern art works and objects which Vivianne De Muynck (Isabella) told spectators were first left to Lauwers by his real father, and then to the fictional Isabella by the paternal liar who raised her. Like everything in this production—actors, musical instruments, voices, words—these materials stayed immutably themselves, objects incapable of transformation yet thick with an opaque past. Unlike Lepage, Lauwers did not offer transcendence through sharing culture or history. Rather he relied on a knowing ignorance and distance. Stripped of their colonial contexts, the stone penis, the slave’s shackles and the Ashanti bronze remained simply that: objects about which one knew a little, but which one could not fully comprehend through a blithe, 90 minute show. As one of Isabella’s lovers said: “You’re a liar Isabella! You told me people were good!” Like theatre itself, Isabella’s Room was a world of lies, some beautiful—that she was raised on a lighthouse, betwixt land and sea—but also ugly—the rape of her mother, the bombing of Hiroshima transformed into an aesthetic image, “as if the sun had exploded and scattered its ash over the earth.”

Delivered as a series of interrupted monologues, the performance effected an easy familiarity, mixing storytelling, verbal poetry and physical interactions on an open, white stage. In sifting through the beauty, banality and ugliness of this century of war and love which Isabella endured, choreography was both invested in and yet discarded as wanting. Lauwers compares his dramaturgy to Jean Baudrillard’s description of postmodern society as “beyond the end”, characterised by “extreme phenomena.” Lauwers’ confusing yet entrancing project expressed the political, social, aesthetic and emotional ambiguity of this condition, in which history seems to have ended, yet, as the cast sang in the finale, suffering, life, love and violence “go on and on.” In the end, Lauwers’ concentrated, festive gobbets proved more weighty than Lepage’s 6-hour-long yet pleasingly digestible menu.

Ex Machina, La trilogie des dragons, director-devisor Robert Lepage, Claremont Showgrounds Feb 11-19; Teatr Piesn Kozla, Chronicles—A lamentation, director-designer Grzegorz Bral Octagon, Feb 14-18; Steamworks & Black Swan, The Drover’s Wives, director-devisor Sally Richardson, performer-choreographers Claudia Alessi, Felicity Bott, Shannon Bott, Jane Diamond, Danielle Micich, composer-performer Iain Grandage, designer Andrew Lake, costumes Zoe Atkinson, projections Ashley de Prazer, Danielle Micich; Playhouse, Feb 3-11; The Builder’s Association & Dbox, Super Vision, director/devisor/text Marianne Weems, His Majesty’s Theatre, Feb 14-19; Needcompany, Isabella’s Room, director/script/set/lights Jan Lauwers. His Majesty’s Theatre, Feb 14-18; 2006 Perth International Arts Festival, Feb 10-March 5

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 36

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Adventures in the Dark, Hanging Man

photo Keith Pattison

Adventures in the Dark, Hanging Man

The hunting and gathering of grants is a tougher task then ever. It seems that there are fewer of them relative to the population of artists, their value in real terms declines annually and the competition increases as training institutions hatch each new generation of artists. As we await the emergence of a new breed of politician who can grasp the consequences of keeping most artists below the poverty line but can also face the futures that artists conjure, there are indications elsewhere of a growing responsiveness. A few signs of this break in the weather include the steady growth of the Theatre Board’s Mobile States touring initiative, operated by a consortium of venues; Melbourne City Council’s Arts House multi-platform program and its Culture Lab; expanded touring opportunities for innovative Australian work overseas and the development of reciprocal programs, like Breathing Space (see our InBetween Time feature in this edition) and Asialink’s Neon Rising Australia-Japan choreographic program; as well as a range of regional arts developments across Australia, strengthening the potential for greater cultural exchange between cities and country centres.

For contemporary performance practitioners these developments bring with them opportunities for finding new niches and new partners within Australia and beyond. A show that might have once enjoyed a brief season can now be kept in repertoire and reach far flung audiences. Of course, it’s not that easy. The old monoculture of arts funding, where finance for individuals, small companies and projects was sought from one or 2 sources is being replaced by a hive of potential partners (venues, programmers, producers, presenters, agents, consortia, festival directors). This has moved well beyond the challenge of writing and acquitting a grant application—and often you’ve still got to get that money in the bank before the other partners come into play. As was revealed in the RealTime-Performance Space forum on the need for Creative Producers (RT69, p40), artists need help to engage with an increasingly complex arts habitat, not only at home, but also as they venture out across borders and oceans. It’s good news then that the Theatre Board has recently announced three 2-year grants for producers at $50,000 per annum, possibly extendable to 3 years, to develop their own models of working with artists. If it works, this strategy could begin to fill a significant gap in the cultural ecology.

Australia’s major arts festivals and venues need to be part of that ecology, embracing innovation, seeding the audiences of the future. The Melbourne International Arts Festival, first under Robyn Archer and now Kristy Edmunds, leads the way, while Sydney Opera House’s The Studio has become a home for cutting-edge popular entertainment distinctly aimed at younger audiences but blended with more demanding material and cultural events that include NYID’s Blowback and dLux Media’s d>Art. Now Sydney Opera House has launched Adventures in the Dark, the kind of program of Australian, Pacific region and international works usually restricted to the arts festival circuit. Such initiatives offer openings for Australian artists and audiences but also provide rare opportunities for inspiration, dialogue and exchange.

Performing Lines

Performing Lines develops, produces and tours innovative new Australian performance nationally and internationally—across genres including physical theatre, circus, dance, indigenous and intercultural arts, contemporary opera, music, puppetry, and text-based theatre. Performing Lines website

Asked about the vision that drives Performing Lines, director Wendy Blacklock, speaks of a desire “to reflect the current trends in contemporary work as broadly as we possibly can.” Works range enormously, says Blacklock of the company’s 2005-06 program, from large scale (Stephen Sewell’s Three Furies: Scenes from the Life of Francis Bacon seen at Sydney, Adelaide and Perth Festivals) to solo works by Performing Lines regular, William Yang (Shadows, Objects for Meditation), and newcomer Rebecca Clarke (Unspoken, directed by Wayne Blair). The company has assisted Kate Champion (Force Majeure’s Already Elsewhere, Sydney Festival 2005) and, as part of the Mobile States consortium, is presenting emerging choreographer Tanja Liedtke (Twelfth Floor). Both choreographers conjure strange worlds out of the everyday. Powerful contemporary performance works are provided by version 1.0 (Wages of Spin), Branch Nebula (Paradise City, seen as a potent work-in-progress in 2005) and Urban Theatre Projects (Back Home, Sydney Festival 2006). Add composer-musicians Linsey Pollak (another Performing Lines stalwart) and Graeme Leak as The Lab and you’ve got a strong selection of touring potential, a good Sydney showing (deservedly after a tough decade for dance and performance in this city) and a wealth of partners—the country’s leading arts festivals, international festivals, Sydney Opera House, Melbourne’s Malthouse and, not least, the Mobile States consortium (see below).

Blacklock emphasises the importance of large-scale works, like the Nigel Jamieson-Paul Grabowsky Australian-Indonesian collaboration The Theft of Sita toured internationally by Performing Lines and generating profits that could be ploughed back into smaller works. However small-scale works, like William Yang’s, that travel extensively also yield income that supports works yet to prove themselves at home before venturing overseas. As well as nurturing new work, Performing Lines supports creative development but also assists Australian companies in the formation of partnerships in, for example says Blacklock, Wales, Argentina and New York.

Wendy Blacklock is particularly approving of Mobile States—Performing Lines is one of the consortium—declaring it an “extremely healthy” operation, supported by several Boards of the Australia Council, focused “on the work those Boards are interested in” and “growing every time it’s programmed.” As for audiences for touring productions, it’s always a challenge, says Blacklock, but the response to Mobile States has been good. As for regional audiences, Blacklock reports that presenters are “more and more curious, wanting to know about Performing Lines’ work.”

Speaking about the international market for Australian work and the kind of obligations that come with it, Blacklock thinks, “reciprocity will rise to the top of the agenda. We can’t keep sending out Australian work if we’re not able to reciprocate. We’d love to be involved in it.”

Mobile States

The consortium of Australia’s major independent contemporary performance presenters that runs Mobile States comprises Arts House (Melbourne), Brisbane Powerhouse, Performance Space (Sydney), Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts and Salamanca Arts Centre (Hobart). Other venues join the touring network for particular productions, eg De Quincey Company’s Nerve 9 included a season in Darwin.

The criteria for selection for Mobile States touring are that works should “employ multiple languages eg physical performance, projection, spoken word and contemporary music/sound; be conceptually and formally ambitious; contribute to current cultural and/or artform developments; be dramaturgically coherent and have attracted positive critique in press and by peers.” The aim is not just to tour innovative works but also “to provide opportunities for audiences across the country to experience contemporary Australian theatrical performance that would otherwise not be seen outside their home towns.” The Australia Council’s Theatre and Dance Boards and Inter-Arts Office have all committed to funding for Mobile States for 2006-2008, and Theatre to 2009. The Australia Council funds go to presenter organisations to subsidise their costs and additional assistance is sought from Playing Australia.

Mobile States represents a major breakthrough for contemporary performance touring (it has included Jenny Kemp’s Still Angela, Chamber Made Opera’s Phobia, De Quincey Company’s Nerve 9, and now version 1.0’s Wages of Spin and Tanja Liedtke’s Twelfth Floor). The number of shows is small, but given the context of much other movement of new work through arts centres and festivals, it is highly significant.

Sascha Budimski & Anton, Twelfth Floor

photo Bryan Mason

Sascha Budimski & Anton, Twelfth Floor

Tanja Liedtke’s Twelfth Floor

Developed by Adelaide-based artists in-residence at the Canberra Choreographic Centre, Twelfth Floor is the first Mobile States work to come from outside Sydney and Melbourne. Tanja Liedtke is a choreographer with a rapidly growing reputation and a lot of dance experience. She believes that the strength of Twelfth Floor grew from the opportunity to work with “5 performers I’m close to and respect enormously…and they’re 5 very distinctive individuals. For 2 months we ate, worked and lived together and that seemed a great premise for making the work, and in a city without many distractions. It became a work about human interaction and confinement, small people in their own small worlds.” Discussion, improvisation and research informed the creation of the work, including Sartre’s “Hell is other people…” from No Exit. The result: a show about a group of people confined in an unidentified institution, withdrawing, dreaming, surviving.

Liedtke feels that “a lot of Australian dance is very nice, but that’s not enough, I want to get to the underbelly, to see people as complex—affection and hostility are such great physical premises for dance.” She recalls that the process of creating the works was “not always easy; at times it was tense and tough, but everyone was up to it. After 6 weeks, 80% of the work was there and we rehearsed it for a week of performances (at the Choreographic Centre).”

Asked how the performers accommodated the demands of her choreographic language, Liedtke replies that they had been in her earlier, shorter works but were also bringing new things to Twelfth Floor. As for that language, Liedtke says: “I work from a visual sense of my own body and its history… It’s a long body…long-limbed, very clear and articulate. I always play with what my body can do…” Music is a vital component of the work, in this case created by DJ Trip (of Adelaide’s New Pollutants) in the workshop.

As for influences and inspiration, Tanja Liedtke says her considerable experience with Garry Stewart’s ADT (1999-2003) taught her a great deal about physicality and energy; then she turned to Lloyd Newson of the UK’s DV8 Physical Theatre (2003, 2005) for the conceptual development she felt she needed: “They’re 2 fantastic artists and my work is about tying what I learned from them together.”

As well as choreographing for ADT’s formative Ignition series, Liedtke’s recent work includes 2 pieces for Tasdance (Enter Twilight 2004) and, forthcoming, Always Building, 2006); a short work about angels for Brigit Keil’s Akademie des Tanzes in Mannheim, Germany and 2 works for Brazil’s Ballet Contemporaneo. The concept of building (“and collapse and rebuilding and, as always, based in the body”) is central to her newest creation, which will also show at the Purcell Room in London’s Southbank in May 2007. Liedtke, like many Australian artists, is more likely to be seen overseas than at home. However, the Mobile States tour of Twelfth Floor offers her the excitement of getting her collaborators back together again and a rare chance for national exposure on a 5-city tour.

Jacklyn Bassanelli, Pink Denim in Manhattan

photo Danielle Brustman

Jacklyn Bassanelli, Pink Denim in Manhattan

Arts House, Melbourne

Melbourne City Council in tandem with the Victorian government is focused on developing venues for the arts: Arts House uses North Melbourne Town Hall, Horti Hall and Meat Market. But it’s not just a matter of programming venues, says Steven Richardson, Artistic Director of Arts House (the Team Leader is Sue Beal), but of nurturing works through the Culture Lab program, which will then become the material for those programs. Culture Lab provides “time, money, space, advice, administration and marketing from the very early ideas stage through to final production. But the approach in these early days”, says Richardson, “is minimalist rather than heavily interventionist.” He doesn’t see Arts House yet in the role of creative producer, rather working with artists with existing agendas and helping them broker partnerships. He sees Arts House’s own partnerships as vital, as a consortium member of Mobile States. Media artist Lynette Wallworth spent time with Culture Lab before heading off to Inbetween Time in Bristol.

Richardson describes the Arts House program as involving “a multi-dimensional process”, with “a curatorial role responsive to the sector.” Artists are supported by Arts House’s own grants program, the funds coming from Melbourne City Council as well as Arts Victoria: “We’re really like a department of the Council.”

What Arts House puts together is “a truly multi-platform program”—visual arts exhibitions, theatre, dance, media arts and contemporary performance. Richardson emphasises that this means a program which can be variously focused, for example the dance and physical performance prominent in the first half of 2006 might not be immediately repeated: “the spotlight will then be on other forms, magnifying their significance.” As well, gaps in the program can be filled from elsewhere in the sector, including interstate work: “we’re keen to foster dialogue”, as is evident in the presence of Sydney’s Sidetrack and others in the program for the first half of 2006.