Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

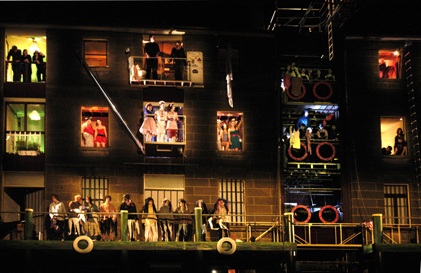

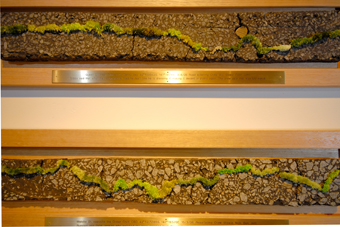

a thousand doors, a thousand windows

image cazerine barry

a thousand doors, a thousand windows

The curious history of windows (pondered by Bachelard, Virilio et al) and their metaphorical standing (windows on the soul; windows as eyes) are called to mind by Xenia Hanusiak’s A Thousand Doors, A Thousand Windows, a multimedia recital for soprano, recorded musical and electronic scores, and projected video imagery.

The Barn at the Historic Rosny Centre has no windows that we can see, just big wooden doors, a high timber rafted roof and richly textured, unadorned stone walls. We are enclosed in its darkness, our ears this time are the windows to whatever we might conjure from the musical creations of Xenia Hanusiak and Constantine Koukias. Yes, there’s a little stage business (occasional movement and gesture from Hanusiak) and video projections (alternating between blandly literal and irritatingly opaque), but the real drama of these works is in the singing. Hanusiak adroitly negotiates the demands of the composers, Hobart based Koukias and the Paris based Finnish composer, Kaija Saarahio, both requiring the soprano to plunge from ecstatic soaring to spoken and whispered text, and to leap back again to the heights. As well, the scores that Hanusiak sings with and against are far from the traditional notion of accompaniment—they merge into eerie wholeness ostensibly musical elements and recorded and created sounds.

Koukias’s Incantation Echoi II (1996) focuses on “the enunciation of pure vowels”, the open-mouthed, uncluttered tools of spiritual transcendance in ancient Christian and other ritual, here felt in passionate cries as well as lyrical flights in the big church ambience that is electronically provided. Lohn (from afar) (1996) is from the first part of Saariaho’s wonderful opera, L’amour de loin, in which a Christian prince in the European Middle Ages corresponds and falls in love with an Islamic princess in northern Africa. They never meet—he dies on the journey—but their relationship has evolved with an ecstatic intensity, here amplified by words sung, spoken and whispered in a shimmering percussive world and echoed with voices off in Occitan, French and English and ending in a heaven of bird calls. Appropriately Hanusiak holds the red-bound score, reading it (the text is the work of a mediaeval troubador) as if a letter from the lover prince. The singing is supple, full-bodied and finely integrated with the recorded material.

A Thousand Doors, A Thousand Windows (2003-04) is a work written and devised by Hanusiak and composed by Koukias. The text has the simple imagery and the aphoristic quality of ancient Arabic and Persian texts: “Do not shut the door/ The excuse is more shameful than the offence.” The authors write that their work is about estrangement and “the need for stillness and contemplation”: “The traveller in the journey knocks at the door seeking acknowledgment and a sense of sanctuary.” They find their inspiration in “the Call to Prayer and the Christian Ringing of Bells”—the bell sounds and a haunting church organ provide anchors in a world of uneasy electronic detail and dark vibrations further tempered by Koukias’ entrancing Greek Orthodox and Middle-Eastern musicality. Hanusiak engages with the condition of the traveller, from whisper to full-throated passion, singing with her own multiplying voice.

The three works of this concert were indeed like windows on the soul—one soul full of yearning for grace, for love, for acceptance; one soul achieving moments of hard-won transcendence in a musical cosmos of unexpected, beautiful sounds.

“Even in an academic context I would never talk about the work of et al, still less ‘explain’ it… the process of viewing art provides the explanation, and it is invariably particular to the viewer. The artist is exactly the wrong person to explain their work…”

This statement by dr p mule (sic) on behalf of the collective, et al. is a telling introduction to the show by this New Zealand group entitled Maintenance of Social Solidarity.

Mounted in CAST Gallery, the oppressive atmosphere of the installation is established immediately by the deep grey walls and ceiling. While the construction of individual objects is rough there’s a strong sense of deliberation and formality to the arrangement of elements within the space. At the entry, I’m confronted with two rows of easels facing each other. I hear a kind of chant bleeding from the other side of the room. Each of the easels displays a poster that has been defaced by cut and paste and packing tape then overlaid with thick, dark, handwriting. This text is like an abstract poem that triggers thoughts about war, solidarity and human rights abuse without really saying anything:

Degrading treatment is

never

Hostility hate

& contempt

day of dooms

a morally

permissible

option

infidel

Hanging from each easel is a set of headphones with soundtrack, the overlaid digitised voices immediately reminiscent of Stephen Hawking. These voices relay excerpts of speeches from key figures in the current war in Iraq, the war in Afghanistan and responses to 9/11. Stripping the actual voice and intonation of the speakers—George W Bush and Osama Bin Laden are featured—places each on the same platform for debate without the prejudice or limitation associated with language or accent. While the idea is interesting, there is a generic quality to the soundtrack –I quickly return the headphones—I feel like I’ve heard it before, another exhibition, other artists.

The remaining elements in the show hang together as one. In the centre of the room a cyclone fence encloses a large projection screen. Twelve chairs sit under a spotlight in their own cell—taped markings on the floor—as if to house a jury or audience at an execution. A desk is lit by a bare bulb like a monitoring station in the midst of the gloom. The chairs and desk also suggest presences that watch and wait. Three more easels sit beside the twelve chairs and on the wall behind them is a grid of images that map mathematical equations, again, defaced by loose, hand written text.

Within the fenceline, the projections are from Google Earth. In digitised tones I hear—“Stockholm”, “Cairo”, “Frankfurt”, “Washington”, “Baghdad.” The projection responds, spinning across the surface of the earth in that familiar Google way before settling just above an airstrip, as if about to land. At first I thought it searched out actual locations, but after a few repeats of the loop, I realised that these were fictionalised places where all else but that which immediately surrounds the airstrip seems blurred, missing or perhaps obliterated. It is as if I am witnessing a series of virtual airstrikes, perhaps from a simulated cockpit. At a certain point in the recording, most notably after “Baghdad” is uttered, the screen freezes and the recording switches to the haunting chant I heard upon entering the space. Given its Middle Easter edge, I read this like a prayer sung prior to attack.

I feel as though I’ve stumbled into a military monitoring or strategy room. From what little I can find about the secretive collective et al., this show is both typical and unique. The consistent aesthetic, the deep grey paint and the elements that appear to be modelled on some militaristic institution are typical. What is not is the minimalism of this piece – the group is known for using a mass of outdated sound and screen technology, quite often to build a cacophonous atmosphere. The use of headphones here allows the sole soundtrack to dominate and the space is easy to read in its arrangement. Given the introduction suggests the work should stand alone, I expected to be able to come to some sort of conclusion about it, but this obtuseness is also typical of et al. While I don’t feel like I’m treading any new ground I am intrigued by this show and the visual imagery—quite beautiful in its own way—stays with me.

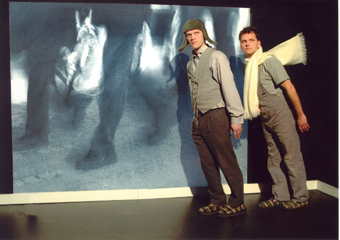

Mikelangelo & the Black Sea Gentlemen

photo Matt Newton

Mikelangelo & the Black Sea Gentlemen

The Nightingale of the Adriatic crooned and swooped in the crazy cage of the Crystal Palace last night, christened by the chants of the crowd The Baltic Stallion—they were swiftly corrected by the charming Balkan.

Mikelangelo’s statuesque form, clad in high black pants, danced in the mirrors beneath the chandeliers and disco ball of our devil’s kitchen. His voice soaked in sauerkraut, he truly was the devil sent from heaven. At one point, he enters the room like the Lone Ranger, guitar slung over one shoulder, dances on tabletops, caresses members of the audience, enticing even the most conservative of us into a fleshy sing-along—La, lah, lah, la, la. I left the show with blood thicker than wine racing through my veins, chanting La, lah, lah, la, la through Elizabeth Street Mall.

Mikelangelo and the Black Sea Gentlemen are a quintet—guitar, accordion, double bass, violin and clarinet. Each brings his own unique flavour to the mix—Moldavio recites a poem about his tragic downfall from taxidermy; an accountant who was sold to the circus as a child bellows a mournful song from the bar (“like love, sometimes the sweetest grape is the first to go rotten”); and Guido Libido suspends our disbelief in a fantastic short silent film sequence achieved simply with a screen and strobe light. The Gentlemen howl like dogs, crow like roosters and all openly and willing support their front man’s formidable persona.

Besides dubious Eastern European accents, the threads that bind these men are strong musicianship and a genuine sense of improvisation. Together, they radiate a lust for life. From the moment they enter the stage (and kiss each other on the cheeks three times) to the final encore (“seven hours worth of blood, sweat and tears in our home country but here rolled into three and a half minutes”!) there is a striking sense of humanity, a liveliness that opens up the possibility of even the humble potato becoming sexy.

Nothing is staged, rather it’s lived and shared. To be so genuine is risky but this is precisely what makes them so captivating. They embody a mock Slavic gloom and traverse a landscape in A minor where the sea leaves villages stuck in mud flats, where the weather is always bleak and where “we’re all just skeletons dancing in a sea of flesh”.

Mikelangelo demands attention like a Spanish bullfighter, and he and his Black Sea Gentlemen have written polkas for the 21st century that you won’t see on Eurovision.

All this and sauerkraut…I fear I may have become a groupie.

Mercy

photo Michael Rayner

Mercy

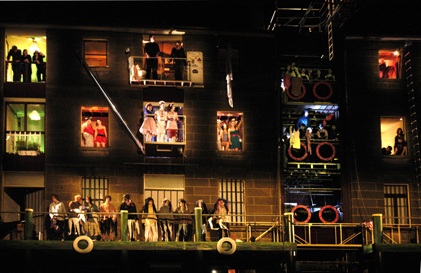

Mercy, the Raewyn Hill-Tasdance collaboration, proved curiously memorable, not the whole production, which problematically aestheticises imprisonment and torture into something quite beautiful (reds and blacks and columns of misty light evocative of fascist chic and movie concentration camps by night), but in a number of individual scenes and a final series that suggest a kind of narrative as an intimate couple go to their deaths.

The whole work, in its choreography, music and design is markedly formal. The brief passages of Pergolesi’s Marian Vespers determine the duration of each scene and evoke, of course, a religious formalism matched in the choreography by gestural imagery of supplication, benediction, crucifixion and pieta-like cradlings. Even their opposites—images of torment and torture—share a Baroque neatness, a dancerliness at times courtly and with evidence too of the balletic underpinnings of much modern dance. It’s when this formalism is broken or a series of images suddenly coalesce into something more potent that Mercy makes its mark in the memory.

A man, stretched out on the floor, wrestles with his chains but what disturbs is a sudden and repeated sharp stiffening of the whole body at the moment he puts his hands behind his back as if to have them bound. One victim struggles desperately in a swathe of red ribbon delicately wrapped about him by his tormentors. Another victim uses her body to plead with her gaoler, wrapping herself around him, climbing and clinging to him, losing grip to fall from his temporary or denied grasp. He catches her exhausted body one more time and she falls, totally and frighteningly limp, face down across his extended arms. He leaves her body behind. Is the gesture he makes one of perverted benediction? Another powerful image is of inert bodies carried in a slow dance across the stage, as if in rigor mortis.

Amanatidis and Dunn stand out in a somewhat uneven ensemble. Daniel Zika’s powerful lighting creates spaces both epic and claustrophobic. Greg Clarke’s costumes include identical bodices and striking skirts for male and female dancers (and the principals share short-cropped hair) creating ambiguity and dark elegance—creatures transcending gender and too beautiful to be destroyed. Unfortunately the balance of the costuming—bare-buttocked, leather strapped—looks the cliched stuff of S&M fantasy, reinforcing a feeling that the content of the work is at the mercy of a sleek aesthetic that undercuts the immediacy of its concerns—fortunately not always.

In a final series of images, Derek Amanatidis dances a remarkable solo of supplication, arms reaching high in a convincing embodiment of prayer, circling low

and returning again and again to stretch up for grace. Amanatidis and Trish Dunn whose bodies have hitherto remained apart but are drawn to one another now entwine in movements of subtle caring such as the gentle cradling of a head. The two separate and lie passively on the stage as a row of torturers advances slowly on them. There is no mercy here, perhaps only in the care they have shared and a dream of grace for those who believe in God’s beneficence—a distant prospect here for all the beauty of the music and the empathy of the choreography. Mercy is at its best when its images of suffering, supplication and caring are at their strongest, when the extremities of torment and yearning are palpable in the dancers’ bodies.

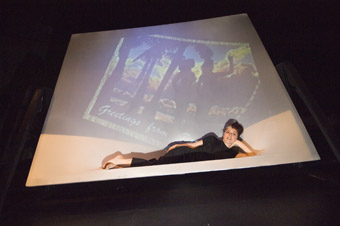

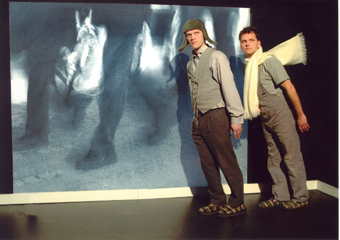

The major retrospective of Leigh Hobba’s work currently at TMAG offered the opportunity for live performance, and the potential was not wasted. Live work has formed an important part of Hobba’s practice since 1996 when he was involved in a number of collaborations at Adelaide’s EAF. This performance was a kind of ‘greatest hits parade’, as Hobba noted when introducing the work and himself. This disarming moment thankfully lightened the tone, which had become tense as an assembled audience of museum patrons and Tasmanian Arts intelligentsia scrambled for the limited seats. This was to be an event.

What then transpired was a gloriously ragged presentation of individual works that moved in and out of each other, creating a serendipitous whole that was strikingly engaging. There certainly appeared to be accidents and human error, but this added an element of informality that freed the work from being a mere rehash of past glories—here was a whole made of parts, like the stark self portraits of Hobba visible elsewhere in this retrospective. Not quite new work, but not a bloodless retread.

Variations 1, a work from the beginnings of Hobba’s practice was deemed the sensible place to start. Its striking use of shadow and the introduction of circular breathing—a technique of playing long, extended forms without interruption—was immediately arresting. This was ritual. Light and dark playing on the wall, the performer hidden yet totally audible, his disembodied silhouette huge, the image of his clarinet extending out to a vast length, every small movement exaggerated.

Unsure where one piece ended and the next began I gave up trying to decide: yes there was a change of pace here, the mood perceptibly shifted, Hobba spoke of Tasmanian tiger hunters, revealing how spoken text figures in his varied palette. Dancer, Wendy Morrow, a frequent collaborator took the stage and the focus for a time, but the sensation that every moment was an extension of the work prior, a growth out of it, was hard to shake. There was progression in the changes as the onstage monitors blinked awake, almost independent of the actual performers, they seemed to have a life of their own, competing for attention. Screen images were being triggered from assistants in the audience, yet the appearance was random, and the question of technical mishap seemed to hover—was this the intent? What was I seeing? And what was I hearing in the gorgeous trilling arpeggio that ended the piece as Hobba wandered out of the room and into the distance? He seemed elated somehow as he took in the applause, waving his clarinet in a gesture of triumph. Something had been achieved, something with deep significance to the personal world Leigh Hobba investigates.

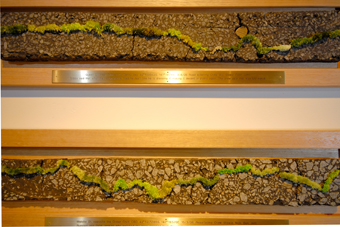

The curatorial premise is promising. Free Range is an exhibition featuring 28 of Tasmania’s leading designers and their prototypes and one-off pieces of jewellery, furniture, sculpture, lights and ceramics. It claims to provide “…a rare opportunity for the participants to venture outside of the constraints of the designer/client relationship and to try something new or different.” I was hooked by this proposal and excited to find out what results when the creativity and imagination of skilled craftspeople is let loose. My hope was that it might be something truly original, aesthetically challenging, and possibly fabulous.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, given that the show is presented by Design Objects Tasmania, all works are object-based. Nevertheless, there is a contingent of works which range into conceptual or artistic territory. I was drawn to these pieces as they represent the furthest deviation from designers’ usual concern for functionality. Textile artist Grietje van Randen for example creates a very tactile full-scale replica of a potbelly stove. It’s made entirely from felted white merino wool and comments on lifestyle habits exacerbating global warming, and urges us toward sustainable living. Ceramicist Zsolt Faludi contributes Three Islands, a beautiful sculpture of clay, glaze, glass and resin symbolic of the hermetic nature of island culture. Rebecca Coote’s two light objects (the largest sized 100 by 80 centimetres) are tentacle-like architectural installations of glass that wrap around corners and dangle from ledges, while Martin Warren’s intensely coloured slumped glass baskets stretch down from above like cooling toffee. These pieces reflect artisans taking delight in challenging the physical and visual potential of their media, as well their own skill.

Furniture is perhaps the most conservative category of works in this show. A number of unchallenging but nevertheless elegant table, seat and cabinet designs feature the precious indigenous timbers (such as Huon Pine, King Billy Pine and Celery Top Pine) ubiquitous in handcrafted Tasmanian furniture at present.

Patrick Hall’s Typeface is a notable exception. A visually heavy, boxy structure 1.8 metres in height, this piece grapples with recollection through the form of an archival cabinet filled with drawers. The collection—ceramic fragments illustrated with photographic images of faces, labelled with strange catch phrases—are not hidden inside but encased behind glass in the drawer-fronts themselves. This exquisite and conceptually complex object evidences Hall’s statement that his practice “is based in craft, is informed by design, but deals with ‘fine art’ concerns.”

Peter Prassil’s Recreational Device is a reclining lounge chair of aluminium, stainless steel and black leather, gadget-ed with microphone and amplifiers. Stylistically sitting somewhere between a dentist chair and the space age interior designs of the 1960s, this furniture piece also stands out for truly shaking off concerns of practicality and commercial viability in favour of fantasy.

The setting of Mawson’s Waterside Pavilion, a purpose-built design showroom, ensures this exhibition maintains an industrial feel. It could have been interesting to view these pieces in a gallery setting, and a number would certainly have benefited from controlled lighting. Alternatively it would be wonderful to actually sit in Prasil’s chair and find out what the microphone and amplifiers did, or to see Megan Perkins leather belts with luscious enamel buckles modelled.

As it is, these disparate works are collated in Free Range almost like an expo and not quite like an art exhibition and as such fail to capitalise on the opportunities of either format. A picture of avant-garde practice from the creative hybrid zones beyond commercial design is not quite realised overall, yet I sense Kevin Perkins could have addressed this to a degree through stronger curatorial direction. There are undoubtedly many very beautiful objects in Free Range and if I think of the show simply as a loose survey of creativity in contemporary local design, it is an excellent indication of the breadth and vibrancy of the industry here in Tasmania.

The Hobart Chamber Orchestra and Tasmanian Chorale’s concert for Ten Days on the Island lovingly entwined the music of Britain’s Henry Purcell and Ralph Vaughan Williams with works by Tasmania’s Don Kay and Peter Sculthorpe in an engrossing program that for good reason felt more British than Australian. That’s largely because Kay’s Matthina in the Red Dress and Sculthorpe’s My Country Childhood, despite local references, evoke the pastoral tradition of British music (Delius, Bax et al) in the finely modulated long lines of their writing for violins and violas and the darker, often telling underpinnings from cellos and basses. The Kay is inspired by an 1842 portrait by Thomas Bock of a young Aboriginal girl in an elegant dress; the Sculthorpe ‘country’ is in part the Tasmania in which he grew up.

A copy of the Matthina portrait sits to once side of the orchestra in the Town Hall, the girl’s apparent serenity and the quiet directness of her gaze captured in the gentle lyricism of Kay’s composition. There’s nothing programmatic about the score, but there is a gradual if always subtle darkening of mood from the cellos, a few sudden silences, like a dance interrupted, and some later plucking and then firm bowing of the double basses (perhaps a moment of disquiet about what the composer sees in the portrait), ending softly and fading with just the slightest hint of discordance. It’s a work more about the viewer of the painting than its subject—there’s a certain elegiac quality although none of the melancholy of nostalgia.

The Four English Folk Songs by Ralph Vaughan Williams are an acquired taste, but the Tasmanian Chorale under the direction of Stephanie Abercromby acquitted them with ease, attentive to the complex layerings with which Williams embroidered and sometimes laboured such simple songs. Their interest resides in part in juxtaposing them with Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas, the first English opera, written some 200 years before the Vaughan Williams and presented in the second part of the concert.

Sculthorpe’s My Country Childhood proved a fine companion piece for the Kay composition, opening in a similar way in part one, Song of the Hills, with a fetching iterated melody and a slight darkening from beneath before a solo violin sings out above the rest. Part two, A Church Gathering, although warmly contrapuntal, evokes a sense of yearning and again the solo violin rises heavenwards. In part three, A Village Funeral, cellos and basses brood, the cello this time dominant in a kind of keening followed by a surge of affecting anguish, heightened by the violins and concluding with diminishing cadences of the same hurt—death now almost accepted. Finally, in Song of the River rapid soft fiddling provides a sense of a speeding current over which run slower waters suggested by a melancholy cello before the whole speeds up in almost frantic ripplings—it’s a wonderful dance of a river as much as a song.

Conductor Myer Fredman paced Dido and Aeneas at the speed it warrants—brisk, allowing the spare drama to unfold without strain and for the listener to feel the considerable force of a string orchestra fattened out with harpsichord, an experience aided by the intimate, clean acoustic of Hobart’s Town Hall. The soloists were all in fine voice, Jane Edwards above all, her Dido heartfelt, unmelodramatic and the continuo playing (cello, Tony Morgan; harpsichord, Stephanie Abercromby) providing firm underpinning for the vocal action. The Tasmanian Chorale were allowed to display their full power and, in the sad final song, their capacity for nuance. This was not a period instrument presentation but the continuo playing and Fredman’s dance-like drive yielded the requisite crispness, elegance and passion.

Entwined was an unusual experience—a traversal of 300 years of music largely out of one tradition, moving broadly from the present to the past, and teasing out kinships between islands—sharing elegance, reflectiveness and a subtle dancerliness in these works. Then again, there was nothing like Sculthorpe’s Sun Music on the program to point to some palpable differences.

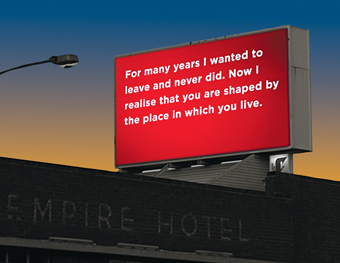

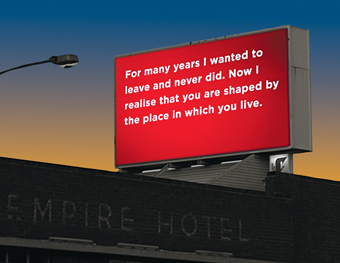

We live in a world of make-believe. We access more information than ever before but the technologies that make this possible can also blur our vision of reality. We are under the misconception that information is knowledge. We become insecure and, as we struggle to connect a constructed view of reality with our own lived experiences, ours is no longer a shared reality but a shared ‘dis-reality.’

The strongest point of audience engagement with et al.’s Maintenance of Social Solidarity appears to be in unpacking the theories it presents. The exhibition notes present six introductions to the New Zealand collective which investigates our systems of belief and defines our current state of disconnection. Etal suggests our freedom is at stake when we can no longer choose what we see and hear, perversely distorting our image of the ‘real’ world.

The room is set up like some self-ordering information bunker. The walls are gun-metal blue and a high wire fence encloses a large projected image of the Google map search engine, constantly scanning city to city around the world. As we zoom in on landscapes (bunkers, airstrips and military installations) devoid of any cultural detail, a computer animated voice tells us where we are. This sense of removal is a reccurring theme in the work. Through various technological means (headphones, projectors, laptops etc) we are reminded that ours is a constructed reality that we do not control. Political jargon and religious discourse rather than geography keep us distant from other peoples and lands, generating a sense of us and them and consequent insecurity.

A section of the space is set up with a series of easels to which are pinned large printed posters that have been defaced by a variety of packing and adhesive tapes. Each easel has a set of headphones attached. Some have a mouthpiece so you feel like a scud missile launcher when you put them on. But the mouthpieces don’t work and so the potential of dialogue becomes monologue as computer enhanced male and female voices speak in what first appears to be a familiar media discourse. It soon becomes apparent that the information we hear is mumbo-jumbo. Suddenly I feel angry, as if my time has been wasted listening to a distant rhetoric that pollutes my reality.

At the foot of each easel is a pile of street press style publications which you can take away with you. They are filled with abstracted imagery of sun-spots and quotes from George W Bush, Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein relating to God, freedom and change. Selected words in each quotation have file paths attached, abstracting them and making them seem computer generated.

Sporadic musical chanting is a reminder of our need to connect for more than just information exchange and heightens awareness of our isolation in a room full of technological equipment and computerised voices. Without being culture or gender specific, the Maintenance of Social Solidarity suggests that these notions of isolation and shared dis-reality are everyone’s concern. We are collectively, not individually, to blame for the displacement of our culture. By creating an awareness of how media and political middlemen make meaning for us we become aware of just how distorted our world view may have become. It makes me want to get straight to the source: to have a cup of tea and conversation with someone across the other side of the world and to hear about their reality.

Alex Pentek, Otherness

photo Craig Opie

Alex Pentek, Otherness

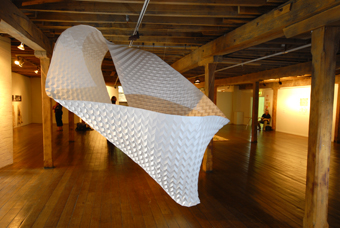

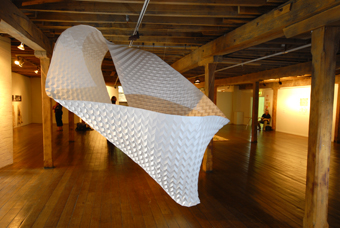

Alex Pentek’s Otherness is a monumental metre-wide Mobius strip constructed from a single length of cartridge paper approximately four metres long. The paper sheet is brought into relief through a meticulous process of scoring and folding. Beginning as a repetition of diamond shapes the folded texture morphs into rounded scales before gradually returning to the original pattern. The loop and twist of the overall structure is simple and graceful.

Amidst the already eclectic range of work in the exhibition An Other Place, Otherness it is an odd entity to encounter. It is big, white and its place within the exhibition concept is at first obtuse. Initially, I complacently assume I understand its investigation: something along the lines of a formalist pursuit of perfection. And I am only vaguely interested.

The sculpture is accessible from all angles and as I wander around its girth peering over its lip into its folds, I begin to realise I’ve been too hasty in judging it. Suspended on wires, it all but fills the volume of space between gallery ceiling and floor. In a dialogue of bodies I warm to this “white elephant” and begin to notice its surprising subtlety.

Natural light passes through the semi-opaque paper, bouncing off and between its surfaces. The interior has the luminescence of a seashell from some angles and elsewhere the gallery’s lighting throws facets of the paper into contrasting yellow and shadow-blue. Disturbances in the air trigger a gentle bounce across the paper structure, a reminder of the material weightlessness of Otherness.

Alex Pentek, Otherness (detail)

photo Craig Opie

Alex Pentek, Otherness (detail)

Crinkles, dents, small tears and holes made accidentally in folding mark the entire surface. No effort has been made to disguise the join in the paper strip, nor the reinforced attachment points of the hanging mechanism. Perhaps the artist was pursuing consistency and perfection, but this work is very much handmade and it bears testament to the fact that the artist is human not machine. The humility of the work renders the concentration, accuracy, care and persistence involved in the Pentek’s labour all the more potent.

An Other Place brings together three Irish and three Australian contemporary artists to explore the notion of ‘other in place’ (felt especially in island places) and curator Sean Kelly in his catalogue essay writes of the slippage between familiarity and confusion associated with this precarious state of being. This concept made tangible in the shifting pattern of Pentek’s work and the eternal loop of the Mobius strip is a powerful metaphor for transition occurring between assimilation and difference within one continuous entity. The play between inside/outside and the twisting that turns both sides of the paper outwards speaks of inversion and extroversion.

Pentek’s sculpture is a floating island: physically self-contained and visually at odds with other works in the show. Its scale makes Otherness impossible to overlook, yet its presence is paradoxically unassuming. What at first appeared a cold rather conceptual and self-referential work turned out, through interaction, to be sensual and receptive.

Mikelangelo and the Black Sea Gentlemen

photo Matt Newton

Mikelangelo and the Black Sea Gentlemen

Mikelangelo pauses to run a comb through his slicked-back hair “ This song is a rumination on gloom” he announces to the teary eyed audience. That’s right folks; don’t wear your mascara to this one. Mikelangelo and the Black Sea Gentlemen is an hysterically funny gypsy cabaret group playing at the Crystal Palace this week.

Mikelangelo is the handsome charismatic ringleader with a voice so absurdly deep that it competes with the double bass. Rufino the Catalan Casanova is a shifty looking violinist with the ability to jump onto tables without missing a note. On the clarinet is The Great Muldavio, a taxidermist on the run from an avenging duchess. Guido Libido, on the piano accordion, looks suspiciously like Uncle Fester (unlike the other Gentlemen, he refrains from singing because his tongue has been cut out in a battle over a woman and replaced with the tongue of a bull). Little Ivan, the bass player, may have been behind the killing of Mikelangelo’s entire family. These characters are completed with immaculate suits, intriguingly sexy European accents and morbid tales of their past.

This is black humour at its best. The truly macabre stories are told through monologues, dramatic re-enactments and satirical songs for which the Eastern European style arrangements are perfect especially for songs like It’s one of those A-Minor Days.

My favourite has to be A Formidable Marinade, a klezmer-themed tune. Besides the song itself which demonstrates the group’s expert musical and song writing abilities the melodramatics that accompany the performance are pretty impressive: Mikelangelo slides through the audience and between the tables like an animal possessed, while singing:

“Sodomy is not just for animals

Human flesh is not just for cannibals

I’ll feast on your body if you feast on mine

Blood is thicker and redder than wine

Lay ourselves out upon the table

Ravish each other ‘til we’re no longer able

When juices mix in the heat of the fray

It will make a formidable… marinade.”

At this point Rufino leaps onto a table and, ripping into his violin, plays a spine-chilling solo, his fingers climbing up the fingerboard to the bridge, higher and higher. The tortuously high notes truly make the described lust real.

The smoke and lights filling the circus tent- style venue provide the perfect stage for a group that enjoys interacting with the audience, jumping onto tables and visiting the bar mid-show (which reminds me: for the ultimate Gentlemen experience, make sure you have a glass of vino in your hand).

Their encore which they describe as a seven hour ordeal squeezed into three minutes of blood, sweat and tears, was rejected by Eurovision, and I probably don’t have to tell you that the producers haven’t any taste. I was trying not to mention the word taste but these are classy gentlemen. However dubious their subject matter, they pull it off, and they pull it off well. Although the band sound great on CD their utterly seductive show has to be seen to believed.

Mikelangelo and the Black Sea Gentleman in the Pacific Crystal Palace

photo Matt Newton

Mikelangelo and the Black Sea Gentleman in the Pacific Crystal Palace

It seems that you can’t have a festival in Australia these days without a Famous Spiegeltent. But sometimes there just isn’t one around when you need it, so an inventive New Zealander decided to build his own. Internally the Pacific Crystal Palace is faithful to the original—wooden floors, ornate booths, stained glass windows and mirrors—perhaps lacking the subtle sensation that generations of festival goers have lived, loved and caroused in its plush seats since the 1920s but including modern comforts such as insulation. Made of corrugated iron and white vinyl the exterior has a very rural feel. But at Ten Days on the Island it is certainly fulfilling its role as festival hub and haven for live music and cabaret.

Mikelangelo and the Black Sea Gentleman

They must have put something in the water in Canberra which produced a generation of wild and wonderful performance groups and bands: Splinters, The Bedridden and P.Harness all share a fantastical, chaotic humour, with more than a waft of feral exuberance. Once the barely clad thrust behind P.Harness, Michael Simic (Mikelangelo) has cleaned up his act over the years, left the nation’s capital and now appears immaculately suited and slicked, leading his Black Sea Gentleman through a Balkan cabaret of parodic ballads and dark entertainments.

The lyrics are BLACK. One song is introduced as a ‘rumination on gloom’; another talks of ‘skeletons on a beach of flesh, drowning in a sea of organs, with lapping waves of blood.’ But somehow it’s all rather amusing. Mikelangelo has the charm of a Croatian Elvis, with constant banter, and audience provocation. Other band members also have their moment—Muldavio, the clarinettist, recites a poem about his days as a taxidermist to the rich, while Guido Libido, the accordion player, ‘performs’ a silent movie in front of a blank screen with a strobe light. They are also fine musicians, pillaging styles from around Europe, swinging between Parisian chanson, gypsy polka and Yiddish lament. In a quick slip across the Atlantic there is even a Western epic. By the end, of course we are singing along, and yearning for real or imagined European roots. If you can’t afford the airfare you should check out Canberra.

Lura

photo Deborah Metsch

Lura

Lura

Lura hails from Lisbon but now lives in Cape Verde on the West Coast of Africa. In her concert she takes us on a tour of the rhythms of her country. She is a diminutive figure with a big voice, warm and liquid in her lower registers, full bodied and punchy in her upper range. Backed by a band of piano, guitar, bass, drums and other percussion, the music is energetic but with a hint a of world weary melancholy. Lura is charming and persuasive, at one point encouraging us to repeat a word after her. She then reveals we’ve been saying “Vaseline” with a Portuguese accent—African hair gets very dry she tells us with a wry grin.

Most haunting were the songs that used the batuku rhythm—those belonging to women. These are slower songs, in which Lura drums on a kind of cushion of folded cloth. The instrumentation is sparser allowing us to appreciate her expressive nuances and gorgeous tone.

And of course there must be dancing. To conclude the show, Lura removes her shoes, ties a swathe of material around her hips, turns her back to us and shakes her booty. The smouldering sexuality that we have been sensing now breaks through as she manipulates the drummer with hip lifts and drops and stamps. Then it is our turn to dance (which you kind of wanted to do all along) and we shuffle between the chairs and tables of the Crystal Palace. Maybe next time we see Lura, the audience should be able to dance for the whole show—it certainly enhances the enjoyment of those hypnotic Cape Verde rhythms.

Christine Anu

Christine Anu appears in a sparkling caftan, thick curly black hair adorned with a massive frangipani. She tells us she is from the Saltwater people—of the swamp bird and the shark—and she welcomes us with an unaccompanied traditional song. And then she and the band launch straight in: “without a word of warning the blues came in this morning.”

Black is Blue combines blues standards with originals, joined by little anecdotes and reflections—Anu dawdling to church and slipping in late; her favourite scenes from The Color Purple; sharing how “the blues is a state of mind.” She does some fine renditions of Wade in the Water, Sister and Night Time is the Right Time interspersed with new songs, one particularly beautiful—My Grandma’s Hands—talking of the strength, comfort and guidance of her grandmother when Anu was growing up on Mobiac Island in the Torres Strait.

She has a big, gutsy voice and she’s not afraid to belt it out. In the second half, she curiously dons an oversized afro wig and the songs seem to get bigger, and brasher. Her tone in Georgia on my Mind, and Hold On becomes relentlessly strident, losing warmth and subtlety. But she recovers them for Fever and No Woman No Cry. Of course, as Neil Murray’s My Island home is the theme song of Ten Days on the Island, she couldn’t leave us without that, and considering the cringe I experience due to its hijacking for marketing purposes, it still holds its own as a strong and soulful song.

Anu is a polished performer and Black is Blue is slick and controlled, each segué and audience excursion meticulously prepared, falling just short of contrived. The initial format of standard followed by original provided a clear structure, allowing for some strong connections and resonances that unfortunately thinned out in the second half. As far as the fake afro for the entire second part including encore? Even in bad hair Christine Anu is a fine performer who gave her audience just what they wanted.

The Knitting Room

photo Robyn Carney

The Knitting Room

Agapanthus, geranium and lavender bushes line the white picket fence. Inside the front door is the living room, home to an old dial telephone which sits on a small table with a crocheted tablecloth. A homemade sponge cake is ready for visitors and a turntable (His Masters Voice style) sits poised to play the nearby Elvis record. I could easily be describing my grandmother’s house; but this is The Knitting Room and all of these objects have been knitted, crocheted or woven to make up the exhibition at the Moonah Arts Centre.

The Knitting Room is intriguing for its colourful detail, its historical and cultural value and its surprisingly raw humour. A knitted tyre-swan, iced Vo-Vo’s, Flick bug-spray container, the milk bottles sitting by the door, are all iconic items now disappeared from everyday life. These specific objects of an era now passed, have been created by the over 300 participants in this exhibition whose average age is around 70, with the oldest aged 96. The Knitting Room arouses affectionate memories. The objects are so lovingly made and the room emits this enjoyment.

You enter via the front yard; and from there you are invited to step into the living room, the kitchen, the laundry and then the backyard. The living room is obviously primed for potential visitors, but the kitchen and laundry sit behind-the-scenes for the regular visitor. I feel as if I’m intruding as I observe a knitted woman relaxing in the privacy of the laundry with her feet up, a cigarette close at hand. Adding to this feeling, the rooms are all roped off giving it a distinct museum aura.

Jennie Gorringe, the Arts and Cultural Development Officer for Glenorchy Council, informs me that this exhibition is a collaboration between nursing home residents, community and environmental groups, the CWA, day centres “and artists”, which explains the eclectic mixture of styles, objects, methods of making and materials. I have to question Gorringe’s use of the word ‘artist’ however. Knitting has long been associated with craft, and more specifically with “women’s activity” and consequently, is rarely seen in the context of high art. I am aware of a number of female artists who are trying to subvert this assumption and, observing the skill displayed in The Knitting Room, it’s easy to see why. I believe all the participants in this exhibition should be acknowledged as artists. Labelling the exhibition as a ‘community project’ also somehow undermines the worth of these participants’ efforts. On the technical side, I am greatly in awe of the skill and time that created such a feat. I know from my own disastrous attempts at knitting!

The Centre expects 4000 visitors over the course of the exhibition, and has had a great deal of interstate interest following coverage on ABC TV’s The Collectors and The Arts Show. By the time I arrive at Moonah Arts Centre, the exhibition has been open only half an hour, but 55 people have passed through the doors. This is a true testament to the wide appeal and novelty of this theme, and entirely appropriate for such a moving exhibition.

Christine Anu

courtesy Showtune Production

Christine Anu

Everyone loves a Diva. The ability to wrap a whole audience up in a gaze and have them smiling unconsciously at your beauty and glowing presence is rare and I imagine it’s a quality to which many female performers aspire. Both Lura and Christine Anu summoned up the spirits of the great divas in their performances in the Pacific Crystal Palace with varying degrees of success.

Raised in Portugual, Lura has made her home in Cape Verde—a series of islands off the coast of Senegal. Christine Anu, more familiar to most of the audience, is a Torres Strait Islander whose rendition of “My Island Home” is played on any available, celebratory occasion in Australia. Both women are utterly gorgeous and magnetic—ticks one and two in the list of how to be a diva. With front row seats for Lura (a single name is also a diva trademark), I was transfixed by her face, her amazing crop of fine curls and gorgeous smiling face atop a tiny frame clad in traditional African skirt and top. There was a sense of knowing and control about each of her moves and an effortlessness in her earthy voice. From my seat at the back of the room, Christine Anu also glowed like a mermaid in her shimmering dress. Her oiled, long curls magnificent, her smile wide. From the first moment, she captured our gaze. Going well so far.

Lura

photo Deborah Metsch

Lura

Musically, the journeys that each took the audience on were quite different. Lura’s show was entirely composed of the music of her Cape Verde home which she textured with stories and explanations of particular rhythms. I enjoyed the nonchalance of her predominantly African backing band. With that diva quality kicking in, Lura transformed the feeling in the room from exuberance to melancholy in the flutter of an eyelash. The sadness in her ballads was palpable and she seemed to need a moment at the end of each to recompose, such was her engagement with the song.

Anu’s program was more mixed. In the first half she worked alternatively with originals and blues standards. Songs were introduced with delightful stories about her Islander upbringing and her identification with the feeling and form of the blues. I particularly liked the way she sang the negro spiritual Wade in the Water after telling a story about making her way to her village church via the beach, then went on to a beautiful song about her grandmother’s hands. Taking a lengthy break which was covered by her band, Anu re-emerged wearing an enormous, red, afro wig and proceeded to complete her program with a solid block of blues standards. She lost me at this point and I found myself withdrawing from the show, crossing my arms and sitting back in my chair. Why? She can crank out immaculate versions of these tunes – Natural Woman, Georgia on My Mind, Fever – and has the most beautiful hair, so why the wig? Deduct a tick for distancing.

I guess the final tick on the diva checklist is crowd response and for this Lura and Anu came up trumps. Lura’s audience responded to her sexiness, her rhythms, her engagement. When she commanded the entire group to “get up” to dance at the end of the show, there were no arguments. Christine Anu’s audience were feverish. I heard a woman behind me say “Did she touch you?” after Anu had just done a lap of the room handing out touches like an evangelist. There was much hooting and stamping of feet to bring each of the singers back for an encore.

There is no doubt that each of these singers is a diva. Lura and Anu matched each other on beauty and magnetism and the ability to fill the room with their voices. But Lura won the diva contest for me with her emotional connection with the music. Her contagious smile and long pauses, eyes closed, at the end of particular songs were compelling. Diva or not, I was left wondering about Christine Anu. I feel that she lost her footing when she took on a wigged persona. I wished that she’d been comfortable enough to make the blues standards her own and know that she could do so without somebody else’s hair.

Sonia Teuben, Simon Laherty, Small Metal Objects

photo Jeff Busby

Sonia Teuben, Simon Laherty, Small Metal Objects

There is something very intimate about listening to music or voice through headphones. It is as though the sound hovers in the middle of your head, making itself comfortable in your own thoughts. A haunting musical score and a personal, heartfelt conversation fill this place in the opening scenes of Small Metal Objects.

Staged in Salamanca Square, the construction of a story through sound provides the structure for the show. The audience is housed in raked seating at the end of the square. Each wears a set of headphones for the duration of the show. The remainder of the Square, the city and the mountain beyond form our stage. With an apparently empty stage in front of us, to any passerby we are quite the spectacle.

In the opening minutes we are all expectant. The music begins and with that, we search our stage for any person or sign that could be part of the show. A conversation opens in our headsets with, “I cooked a roast last night.” This is chat between two male friends that mixes ordinary observations with personal thoughts on life and love, “You know what you should do? Get a pet. A pet brings out the love in people.” The voices are slow and stilted. These are two men for whom speaking takes some labour and thought, but the content of the conversation is common place–loneliness, love, fear–“Are you scared of dying?” Garry and Steve seem close, they talk openly about their affection for each other.

It takes over five minutes until the two men are revealed in the square. I become aware of the sound of falling water in my headphones and realise that it is in sync with the fountain in the square, allowing me to locate the men about 60 metres away from the audience. They wear wireless mikes so that their talk reaches us in real time. The conversation continues as they walk toward the audience and we see that each of these men might be labelled as having a disability. It is at this point that the plot speeds up. Without wanting to give away too much of the story that ensues, Steve and Garry become engaged in an apparent drug deal involving two others who emerge from cafes and restaurants within the Square. Alan and Caroline are a high flying lawyer and change management consultant. The deal falls apart when Steve has a crisis: “I want people to see me, I want to be a full human being” and the couple are unable to get the two dealers to cooperate.

I have to admit to finding the set up for the show compelling but confusing at first and I found it difficult to get past the fact that the square is almost empty at our show’s timeslot – there is something lost in the absence of innocent bystanders as I imagine that their reaction to the play would range from complete ambivalence to avid curiosity. A crowd would have also given the players an environment within which to hide more successfully. It is only in the hours that follow the show, in considering and reconsidering the content, that I realise the greatness of Small Metal Objects.

Certain people within society, particularly the aged and disabled, are often the “unseen” to quote from the show’s program notes. I understand now why Steve’s crisis abates after the bungled deal: “I feel better now.” In the context of the deal, he is not only seen but in control. The high-powered pair, who are accustomed to getting anything they want, going anywhere they please, are rendered helpless. Their money and influence mean nothing and they are forced to operate within Steve’s sense of time. And what a perfect cover if Steve and Garry are actually dealers—would you suspect them?

This is a slow-burn show that left me puzzled at first, and worked its magic afterwards. Small Metal Objects found its way inside my head just like the music in the headphones.

Sonia Teuben, Simon Laherty, Small Metal Objects

photo Jeff Busby

Sonia Teuben, Simon Laherty, Small Metal Objects

I am sitting on tiered seating at one end of Salamanca Square, headphones on, exposed to the wind, the rain and the gaze of passers-by. I am a spectacle In this unique way Small Metal Objects challenges notions of community and judgement in society.

This public space is converted into a stage, and the public are the performers. A conversation between two men is heard through the earphones, punctuated by electronic music, while the audience looks out at an almost empty square searching for the source of the voices. I spot the pair as they pass the bakery; the square is so empty that it’s not hard. They wander towards us, while people walk past and stare at both the performers and us.

The characters, Gary and Steve, both appear to have a disability, made obvious to the public by their physical appearance; and so the stares they receive have a different focus to ours. We have voluntarily placed ourselves in this position, and we can slip out of it after the show when we remove the headphones. I must admit, this is of particular interest to me, because I have worked in the disability services field, and have regularly witnessed quite negative reactions from the public towards people with physical and developmental disabilities. This theme makes Small Metal Objects personally compelling, even more than the dialogue unfolding.

It begins with a conversation about marriage, sexual orientation and the death of Steve’s cat. The language is slow and simple, caring, patient and understanding. Then Gary takes a phone call from a nervous sounding man, Alan, who enters the square, carrying an envelope of cash and talk of a ‘deal’. A ‘business partner’ of Alan’s, a corporate psychologist, is called to the scene when Steve refuses to cooperate in the deal, and she takes over from Alan using different methods of persuasion. Steve needs time, Gary explains to the anxious, pacing Alan, while the music becomes deeper, percussive and suspenseful, matching the tension felt by Alan and his partner. What follows is a sickening display of misunderstanding and disrespect.

However, there is an element of humour in the production, a welcome addition to a grave subject. The introduction of the ‘corporate psychologist’ for instance, where a jargon filled job description designed to impress the listener, fails on the uninterested Gary who obviously holds different values. Later, Steve turns to Gary and says of Alan: “I know he’s famous and all but he just looks like an ordinary guy”.

I did wonder what the production would be like if the square was filled with people. Due to the cold weather and time of the day, the space was almost completely empty, whereas the production is designed for a crowded public space. The actors utilised the space well, traversing the entire square; and I can imagine that my response would be very different if the figures were blending with the public and often blocked from view. In saying that however, the empty square did work as a positive in some instances, such as when Alan was first looking for Gary. Despite standing near him, Alan walked away approaching the few other people in the area, before finally returning to Gary, an emphatic last resort.

The values manifest in Gary and Steve’s characters and their relationship are beautifully observed and played out in the production, in distinct opposition to Alan and his partner. These are accentuated by the body language, contributing in particular to the key interactions between the characters. I have never seen such an original and entertaining attempt to challenge social attitudes that discriminate against people with disabilities.

Small Metal Objects

photo Bec Tudor

Small Metal Objects

Scouring the scattered groups passing between the restaurants and bars in workday twilight I am trying to match the intimate conversation coming through my headphones to people in the square. Two males speak frankly about love, relationships and loyalty. The lines are delivered slowly and deliberately. Steve is depressed, he wants a girlfriend, he’s also wondering if he is gay. From my vantage point on the raked seating tucked into the side of Salamanca Square I focus briefly on a group of young men smoking. The other guy, Gary, is understanding, “You’ll work it out mate…I just want to see you happy.”

Disparate piano notes and a deep repeated reverberation form an ambient, almost cinematic, soundtrack supporting this dialogue. I start thinking that perhaps I will not meet these characters. Couldn’t this almost be anyone’s conversation? I watch passers-by watching me. I am completely comfortable in my voyeurism, elevated and aurally insulated. Shit weather is rolling down off Mount Wellington, it’s cold and windy and the square is emptying out. Behind the voices, the recognisable sound of falling water suddenly emerges and I immediately look to the fountain. The protagonists are easy to identify—not because they are miked up actors in a public space—but because they look and sound like they might be people with a disability.

An outline of the story is insufficient to explain this performance. However, as it develops it involves a young property developer named Alan who is desperate to buy $3000 worth of drugs from Gary and Steve. Like the businessman, I am unsure whether what ensues is merely the result of a miscommunication, or if the dealers have a very unorthodox way of doing business. The “goods” are never named and neither Steve nor Gary ever directly confirms they have them. The correct money is handed over but the trio never walk to the locker to collect because, as Gary explains, “Steve won’t leave that spot and I won’t leave him alone.” A distressed Steve has decided it’s time to be seen—he wants other people to value him as a full human being. The deal is off.

In desperation Alan calls in colleague Caroline, a corporate psychologist in the business of ‘change management.’ She tries all of her manipulative, condescending tactics and eventually loses her last thread of integrity when she tries, unsuccessfully, to lure him with the promise of sucking his dick. The executive pair leave in anger, chasing an alternative score. Steve and Gary are nonplussed. In fact, Steve feels better now.

The performance finishes and I am utterly bewildered. It’s like I never quite got to connect the dots, and yet I don’t feel it entirely went over my head either. I enjoyed the show, so why do I feel I don’t get it? And what were the ‘small metal objects’?

I’m thinking the title could refer to the money exchanged (though that was in paper notes) and Steve and Gary’s comment early on, “Everything has a fucking value!” Having the right change doesn’t necessarily get you what you want. Being loaded doesn’t make you happy. Being ‘less fortunate’ doesn’t always mean you’re missing out. Money, after all, is just small metal objects.

In a funny way the small metal objects could refer to the radio microphones. While these are hidden on Gary and Steve, Alan and Caroline wear highly visible headsets. This technology gives the high-powered professionals an aura of authority, like they’re privy to more information than the others. The radio microphones connect the audience to the action in a manner of surveillance, which in this age of terror, operates through the identification of difference.

It’s fair to say that the general public pay no attention to those performing out there in public space. Not even when Caroline yells insults at Steve. Not even when she’s pulling his arm and Steve cries out “I don’t want to go.” Suddenly this scene takes on the sickening likeness of a child-snatching in a crowded shopping centre, where later everyone wonders how no-one saw or did anything. How would you react if you saw a drug deal underway in public? Or an aggressive argument between a woman and man? Social awkwardness often leads us to look away thinking we’re not implicated, thinking, I’m sure they’re alright. How do you behave when simply you encounter someone with a disability?

Dependency is the recurring theme of this performance. Gary provides emotional support for Steve, who supports Gary when it comes to ‘doing business.’ Between those two there is a short discussion about pets. Caroline accuses Alan of displaying needy behaviour when he calls her for help, yet they are both desperate for the drugs. And underlying all this is the idea that people with disability are people with ‘special needs.’ Implied in this euphemistic phrase is the belief that these people depend on others to live an ordinary life. But there is nothing Alan or Caroline have that Gary or Steve really need or want, and they refuse to be used as mere conduits for a transaction.

There were aspects of Small Metal Objects I simply didn’t understand—Steve and Gary’s ‘business’ discussions for example. And I wonder if something was lost because the square was so quiet that day. Or maybe because the culture of Salamanca precinct is so tourist-driven that a little rain completely drains it of atmosphere. I imagine the experience would have been very different in the bustling civic spaces of Sydney’s Circular Quay or Melbourne’s Federation Square. And perhaps even the thoroughfare of Hobart’s greasy Elizabeth Street Mall (where, incidentally, I regularly witness public fights and intoxicated people) could have been a more fruitful setting. The enduring dynamic I am left contemplating is the friendship between Steve and Gary. Throughout all the assumptions, value judgements, transactions, pressures and attempted manipulation these two are like rocks in a stream. They have integrity, they stand by one another, they have love. They may also have had $3000 worth of drugs, but I’m still not sure about that.

Cheryl Wheatley, Queen of the Snakepit

photo Michael Rayner

Cheryl Wheatley, Queen of the Snakepit

Distracted for a moment in Cheryl Wheatley’s Queen of the Snakepit, I found myself mentally revisiting that seminal 70s pedagogical text for actors by Robert L Benedetti entitled Seeming, being and becoming—as you do.

Wheatley comes on strong in her persona as Lois, our guide on a virtual tour to Flinders Island in the northeast corner of Tasmania. Lean and rangy, clad in skirt and blouse, knee-high stockings and plimsolls Lois is an instantly engaging, if brash and bawdy host, shouting some of us down the front a beer (or a shandy), which she whips from her well worn Esky. Later, from this bottomless pit, she’ll also extract a slide projector and a couple of inflatable kangaroos. Like any good guide Lois introduces us to the outstanding features of the island, including its incessant wind. To do this, she lugs an industrial strength wind machine from the wings. When, in the process, she inadvertently knocks the hat from the head of the Mayor of Tasmania (who’s apparently rarely seen without one), Wheatley handles it all with bravura and the audience (Mayor included) respond with even more good humour. Playing the affable guide seems an easy transformation for Cheryl Wheatley who was born and bred on Flinders Island and has a deep love for the place (she identifies its location by referring to her own breast) and the earthy characters who populate it. As in all good performance, it’s often difficult to untangle the persona from the performer herself.

The other aspect of the work demands that, before our eyes, the performer “becomes” a series of women—the ones who stay on the island while the men go to sea and hence, she believes, share a unique understanding of the place. Most are variations on Wheatley’s relatives, among them, Queenie, based on her grandmother, an earthy old lady who holds court in the “Snakepit”, the ladies’ lounge at the back of the pub. Wheatley’s work with mentor, John Bolton, presumably focused on developing each of her personae in this work in situ. Somehow, though, as Wheatley steps in and out of these imagined bodies, she loses her performative footing. She adopts the physique, the vocal tics, a nicely poetic turn of phrase, but now appears actorly, tongue-tied, less assured in her connection with the audience.

Finegan Kruckemeyer has the writer credit on this show but clearly its construction has involved a number of hands including the performer herself as co-devisor. Sound artist, Jethro Woodward’s work provides an important atmospheric layer. There’s also a rudimentary show of slides that fits the homey feel of the show. At another distracted moment, I imagined Lois as one of those well-equipped guides with a video camera that would allow us some quality images of the Island. Principally, though, I’d say this promising work has a way to go to achieve the fluidity of form suggested by the material. Some sharper writing is needed for the island “characters” and a more comfortable performative bridge to take performer and audience safely from the friendly engagement of the guide we meet at the beginning of Queen of the Snakepit to the deeper understanding embedded in the female spirit of place that it seems Wheatley would like us to souvenir from her tour.

Robert Jarman, The Spectre of the Rose

photo Carolyn Whamond

Robert Jarman, The Spectre of the Rose

It’s good to be surprised. It keeps you on your toes. There’s a moment in The Spectre Of The Rose where Robert Jarman, as Jean Genet, takes a razor to his own wrist. Ugly and abject, this was also a moment of revelation: despite being the third time this work has been mounted in Hobart the text itself is still being interrogated. Each time, some new, darker meaning is dragged into the light.

As Genet’s small bright wound was revealed, the whole performance shuddered closer: I understood something. This show is about Genet in his familiar roles—thief, writer, homosexual—but it’s more: an attempt to get underneath the Genet created by the text to the Genet writing, living the text in his cell, where this play’s action occurs.

The key moment arises as Genet indulges himself in a dark sexual fantasy: rough street sex with a sailor he then imagines murdering for the sheer thrill of it. It’s a fantasy drawing on Genet’s adolescent idolising of famous murderers. In Jarman’s previous versions we witnessed Genet somehow triumphant in his cell indulging like a dark god in extremes of sex and death. Here was the same empowered Genet, but with nowhere to direct the raging energy he has built up, but at himself. There is no sailor. He is alone. He is cutting himself.

That’s all he can do. Is this release?

There is further to go and worse to see. Jarman’s Genet has already told us, epigrammatically, that the only way to escape horror is to bury yourself in it, and that’s the way this narrative goes, into a horror starker than Genet had ever imagined. He is alone, naked in his cell, howling to the stone walls: “Kill me! Burn me!”, a cry competing with a terrible throbbing on the piercing soundtrack.

Genet’s brutish epigram is however realised: somewhere in this awe-full moment is the kind of transcendence Artaud sought in his Theatre Of Cruelty. The performer is naked and open, totally exposed, in a moment of symmetry in his engagement with the text. Nudity is a hell of a gambit in theatre, and may miss the mark of genuine transgression by being simply gratuitous, but here I felt it was successful, adding meaning rather than shock. We were looking at a real Genet, failed by his own fantasy: he cannot kill. He is not one with the murderers he idolises. He’s a thief. All he can do is wound himself, the cut revealing far more than blood, the text exposing an angry human, his articulacy warped by imprisonment, a man mired in consuming erotic fantasies, which despite their ultimate failings are still all he has to sustain himself. It’s a deadlock: there is nowhere for him to go, no God to judge him and give him release. He crawls back into the bed where we first saw him. The performance ended, but there was, and still is, a ringing in my ears.

Cheryl Wheatley, Queen of the Snakepit

photo Michael Rayner

Cheryl Wheatley, Queen of the Snakepit

Lois stands on a chair holding two lit torches as headlights. We’re passengers on her ute tour of Flinders Island and everyone in the audience has been made to put on their seatbelts. She calls the potholes in the dirt road ‘Dolly bumps’ because, while Lois loves Dolly Parton, at times like these you’re glad you don’t have her attributes. On “go” two audience members hurl inflated kangaroos at Lois’s head. Chaos briefly ensues. With manic swerving and cursing she avoids a crash and the guided tour through family history and mythology of place continues.

All the props in this performance emerge from Lois’s Esky, and many of them end up in a strange shrine-like arrangement carefully constructed over the duration of the show. Containing fragments from the stories told, such as Naked Lady flowers, abalone shells, paper nautilus shells, the pieces of a ripped-up crayfishing licence and a windswept tree branch, this assemblage is like a tribute to Flinders Island. Throughout we’re shown a teatowel map and hazy landscape images, but it is this collection that makes Flinders visible for the audience.

In Flinders folklore the paper nautilus shell washes up every seven years. This periodic appearance is symbolic of the islander way of life, characterised by a gradual passing of time that is measured on the ancient scale of the landscape itself. The return of the shell also mirrors the journey of the island’s youth who leave seeking adventure and return home (the place, as Lois found, where your feet grow roots) years later. Coming to shore from the ocean, the shell also links the domains of the men and women folk. We learn that while the fishermen are free of the island when they are at sea, the women are relentlessly land-bound.

Queen of the Snakepit is the story of female life on Flinders told through four characters from the one family. In addition to Lois there’s her cantankerous mother Queenie who single-handedly built a jetty of stones for her fishermen husband and sons to come home to, but now spends her days alone. There’s eccentric aunt Myrtle who, when her complaints to Parks and Wildlife back in the early 1990s were ignored, took the feral cat problem into her own hands. And there’s the memory of young Lily staring out the window asking questions and making observations about this place and its people. She at first seems to be Queenie’s dead daughter, but is later revealed to be Lois herself.

This performance is devised and performed by Cheryl Wheatley. She undergoes impressive physical transformations as she morphs between four women of different generations to create a montage of incidents and memories across time and space. Moments of humour and intimacy created by each character propel the performance. Queenie’s debate with herself about whether or not the old pine tree needs its middle cut out was for me a very tender insight into a life of hardship and isolation. We learn from the dedication at the end that the character of Queenie is actually based on Cheryl’s mother, who passed away only weeks before this show opened.

In contrast to these engaging characters our guide and narrator Lois seems a conglomeration of loud ocker stereotypes—from her op-shop ensemble to her clipped language, hackneyed expressions and tit jokes. Sure, Lois is meant to be a woman of strong personality, the tough-as-guts country type who’s lived most her life in a small male-dominated community. I know this kind of sheila, I’ve got one or two in my own family, but I find Lois an ugly caricature. I see none of the knowingness, the disarming charm or dangerously sharp wit that makes natural yarn spinners of the Australian breed so charismatic. Given Cheryl is a fourth generation Flinders Islander I wonder why she felt the need to invent the ‘larger than life’ Lois.

It is only as Lois that Wheatley initiates audience interaction, and her manner is rather like playground bullying. She plays favourites with some individuals with whom she holds inaudible, rather lengthy, one-on-one conversations mid-performance. In other moments she intentionally invades personal space, helping herself to our drinks, blasting us with a wind machine and spraying us with water. I think I experienced a personality clash with Lois. I suspect, at its root, this may reflect a discomfort I feel with much such theatre. But that aside, I simply didn’t find this “witty and wise” character insightful or funny.

There is beauty, richness, idiosyncrasy and universality in the stories of Queen of the Snakepit. The family connections between characters give this account of place its form and sense of authenticity. Unfortunately however, the crude rendering of the central character meant that intimate and engaging moments were scattered through an often tedious and frustrating show. Curiously, I like the fact that after this ‘tour’ I still have very little sense of what Flinders Island would be like to visit.

Maria Island school children, c1930, Anne Christie collection

How many islands are there off the coast of Tasmania? Do you know how many people live on them? Anything about their chequered histories? What makes these places special? Most importantly, what does it feel like to be an islander? I’m a Tassie girl through and through and I don’t even have half the answers. With a quest to right this wrong Maria Island of Dreams and Queen of the Snakepit take audiences on a guided tour of two Tasmanian islands.

Along with its Indigenous occupants, Maria Island has hosted inhabitants from a parade of countries throughout its extraordinary history including Holland, France, England, Italy and New Zealand. Devised to weave music, poetry, video projection and spoken word, the show tells the story of Maria Island through the recollections of Vega Bernacchi, the daughter of an Italian entrepreneur, and a host of other characters. Accompaniment is by local group Silkweed, on violin, accordion, keyboards, cello, percussion and voice, and whose members are woven into the story telling. Apart from a dancing couple who appear towards the end of the show, the musicians and narrators all stay in place, concert-style for the duration.

For Vega Bernacchi (Sarah Cooper), Maria Island was her first playground. She recalls her delight with the sound of the Indigenous name of the island and childhood re-enactments of the penal settlement era. She is nostalgic for the time when her parents farmed wine and olives and her own life as an adult on the island. Against a projected backdrop of historic images, family photographs, paintings and present day landscape shots, we hear snatches of letters and reports from French explorers, English convicts and their captors, Moari martyrs, an Irish political prisoner and Diego Bernacchi whose dreams for Maria seem to be the inspiration for the show’s name. The male characters are played by Les Winspear. Silkweed build the atmosphere with delicate tunes and folk songs that flesh out the emotions of the events. There is a sense of completeness to the story—we see the life of Maria Island go from uninhabited to agricultural and semi-industrial and then back to nature—as a reserve. Maria Island of Dreams is comfortable, polite—a multimedia recital.

Cheryl Wheatley, Queen of the Snakepit

photo Michael Rayner

Cheryl Wheatley, Queen of the Snakepit

By comparison, Queen of the Snakepit is brash and loud. We are a captive audience. Lois (Cheryl Wheatley) from Flinders Island takes us on a tour of island landmarks and characters. She is a bundle of love and hard luck with her white cricket hat, high waisted nylon skirt, saggy shirt and slip-on sandshoes. Lois’s Esky is her magic pudding of props—everything emerges from the ubiquitous white lidded box throughout the show. A tea towel tucked into her waistband is the map for the tour and a suspended sheet is her projection screen. With the audience seated cabaret style, Lois weaves between the tables alternatively delighting and harassing us with her demands for attention and participation. While this is confronting for some, there is a disarming sweetness and warmth to Lois’s engagement: “yeah… that’s all you need to do really, say G’day back, then you might get to know someone that you never imagined knowing.”

For the hour of the performance, Lois is all of the women of Flinders as they watch their men come and go from the sea. She morphs into Queenie (the Queen of play’s title), her aunt Myrtle, and herself as a child. Queenie and Myrtle are tough, wise and very rough around the edges. Just like the tides, these women represent the ebb and flow of island life. While Queenie has spent her adulthood giving birth to islanders (eleven children in all) and seeing her men off to sea, Myrtle bears witness at the other end of life, making wreaths for the dead from “the old flowers, that most people call weeds” along with slaughtering as many feral cats as she can get her hands on. Wheatley’s characterisations of these women are both humorous and poignant. We laugh at Queenie screaming for her beer from the Snakepit (a nickname for the Ladies’ Lounge at the Whitemark Hotel), while also registering her grief: “You should never have to bury your children. They should bury you.” Like breaks between chapters, Lois builds a shrine throughout the show that is composed of important objects or island symbols. There are the trees that “grow sideways like the people”, the nautilus shells that keep time, and the ever present snakes that seem to represent fear, wisdom and longevity.