Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Synaesthesia SYN019

http://synrecords.blogspot.com/

Gauticle is the second release for the Melbourne-based trio of Anthony Pateras (prepared piano), Sean Baxter (percussion) and David Brown (prepared guitar) recorded during their foray into Europe in 2004. Unlike their previous record Ataxia, this time they have opted for solely acoustic instrumentation. Describing their music as ‘exploratory acoustic’, the group combine their interest in improvisation and idiosyncratic techniques with an appreciation of free jazz, electronic noise and the classical avant-garde.

One thing this album gladly lacks is that feeling of tentativeness which can so often kill recordings of improvised music stone dead. Having played consistently since forming in 2002 the trio is focused, deliberate and capable of great subtlety. Thankfully, this is also not a series of illustrations or set pieces to show off their various preparations, but rather 5 pieces of intuitively produced music. By focusing on their sounding possibilities Pateras, Baxter and Brown relieve both the listener and themselves of the need to examine or explain the purpose of the preparations, or the techniques involved.

With their various preparations Pateras and Brown direct their instruments away from the sound of strings, melody and harmony, and instead focus on the timbral and percussive aspects of music making. Baxter’s kit tends as much towards metallic junk, plates and cymbals as to drums. In a loose sense Gauticle is an album of events dispersed across all 3 instruments. Although this is a record with much attention to space and resonance, it never becomes reductive or simply pointillist. Instead what is most interesting about this music is the way small percussivie events coalesce into streams and layers of sound moving at different speeds, each of these layers containing elements from all 3 players. This lends the music a multi-directional feel, giving it an ability to propel itself forward without sacrificing a sense of space or even place. There are backs and fronts and spaces to the side, between and underneath the sounds presented here, but not between the instrumentation. This is after all a group sound. It’s sound that flows—not just like liquid, but like a bucket full of miscellaneous rivets.

Improvised music is often characterised as not just a music of interaction, but of possibility. This possibility is not just about what the music can be in the present, but how it can continue to invent itself in the future. And in that sense, it needs to draw inspiration from the resources it employs. On the evidence of Gauticle, it would seem that beyond their instruments, the music of Pateras, Baxter and Brown is underpinned by an attention to resonance. Of course, resonance is a fundamental component of acoustic performance: vibrating air inside the body of a guitar, a drum skin, a struck cymbal, the piano‘s sounding board, the tone of a room. Unlike much European ‘chamber improv’, which seems predicated on a reductive notion of sound played into some metaphorical silence, this understanding of resonance allows something more generative to occur and for the music to be able to find its future: that if music like this is underpinned by resonance then sounds other than instrumental sounds are crucial. So on Guaticle, even when individual sound sources fall silent, by following the trailing away of its reverberations we hear the recurrence of the sounds of other things, quiet, but still persisting: everyday sounds, other reverberations, other people, other interactions, and in those sounds the possibility for more.

Peter Blamey

Melbourne: Move, 2005

Melbourne: Move, 2005

MD3297

www.move.com.au/

Melbourne/Sydney: Cracked, 2005

Melbourne/Sydney: Cracked, 2005

www.crackedrecords.com.au

The influence of New Age-ism, and its associated, banal reinterpretations of Brian Eno’s “ambient music”, has contributed to a surfeit of dubious, cross-cultural musics.

Machine For Making Sense react against this by crafting harsh textures and violent, sound art concatenations (for example, Dissect the Body, featuring Satsuki Odamura on koto and Stevie Wishart on hurdy-gurdy), while Liza Lim and Julian Yu produce orchestral works incorporating European and Oriental instrumentation which possess some characteristics of both Euro-American Romanticism and high modernist dissonance and atonalism. The material compiled by editor/producer Le Tuan Hung for On the Wings of a Butterfly has some sympathy with this second approach—notably Brigid Burke’s fabulous, lightly perturbed mix of scattered percussion, sudden tabla accents, and irregular rumblings of clarinet, embedded within a harmonic vibraphone and electronics wash (track seven). On the whole however the artists presented here have chosen less arch and more lyrical methods, with several Oriental classical traditions being brought together with European Medieval and Renaissance ideas as well as atmospheric percussion. In this sense, On the Wings of a Butterfly sits well alongside the rest of the work of soprano Deborah Kayser (featured here in collaboration with shakuhachi player Anne Norman), Jouissance and others. While not “wallpaper music” in Eno’s sense, On the Wings of a Butterfly largely presents a meditative, seductive listening experience whose aggressive elements are found more in sudden jumps of the volume (as with Dindy Vaughan’s work; tracks five to six), rather than in overt sonic or textural distinctions. The materials are on the whole well balanced, harmonised and successfully melded. The approach is therefore more one of fusion rather than contrast or dialectic, of finding common timbre and rhythmic patterns across traditions rather than setting them against each other in a kind of debate.

On the first track, Kayser and Norman present a gorgeous, soaring, while at times barely breathed meditation on the work of Hildegard von Bingen, the long, gliding tones of the shakuhachi complementing the extended vocal lines of early European liturgical chorale. This is perhaps not surprising given that both musics developed partly to assist spiritual contemplation.

Nevertheless, some of the shorter, more hesitant enunciations of the duo help to give their interpretation a more modern, formalist touch. Norman’s collaboration with vocalist Ria Soemardjo (track three), underscored by Hindustani dulcimer strings, successfully melds two Oriental improvisatory traditions (Japanese and Indian) in a work which not only recalls the ragas and chants of the Indian subcontinent, but also incorporates some freer, non-verbal sung motifs, which are, in turn, echoed by Norman. Tuan Hung’s own contributions, in which he plays dan tranh or Vietnamese zither, are less effective, with the musician tending to flatten the material by interjecting repeated passages of strumming rising and falling through whole scales (notably in his collaboration with Ros Bandt on Medieval psaltery; track two). Where Tuan Hung resists this particular temptation, on track four, his work is impressive, the zither’s slightly fractured, discordant tones and string-bending technique answered or supported by ringing bell percussion and open, tube-y sounding pan-pipes.The CD closes somewhat disappointingly with the linguistically unremarkable (and strikingly Orientalising) poetry of Rewi Alley (tracks eight to 11), supported by shifting organ chords from Warren Burt, to which the vocals have also been tuned.

On the Wings of a Butterfly features an additional two compositions selected from Vaughan’s own CD, Up the Creek. The latter, 12-track collection sees Norman paired with harpsichordist Peter Hagen. The duo play six works together, and then perform as soloists on three pieces each. Hagen’s technique is at times harsh and brutal, with Norman generally doubling the main harmonic lines and introducing sections with a rising, breathy spaciousness, or rising above the stately lines of the harpsichord to lead in a complicated series of jumps and glides. As noted earlier, the dynamic of the pieces is often striking, with abrupt leaps from quieter, building sequences and scattered phrases, versus loud, crashing motifs and crescendos.

The harpsichord is such a cultural loaded instrument that images of Baroque symmetry and early cinema horror soundtracks cannot help but intrude, with much of the interest being generated by how Vaughan disabuses one of such assumptions without totally abandoning the idea of adding her own little, mathematic, self-enclosed passages, derived in part from the high Classical tradition. While only occasionally exhibiting actual atonalism, several tracks nevertheless attain a dissonant complication of musical structure through the tentative indirectness of the links between passages as well as their attendant silences, which makes for a highly unconventional listening experience. The vaguely modernist tracks five and six break, clash and then pause in a highly arresting manner.

Norman’s solos move from clipped materials which sound almost like discontinuous allusions to Stravinsky’s Firebird played on shakuhachi, to the more characteristic woody, breathy tones of the instrument, but with a fluttering and lack of intensity only found in 20th century American-Japanese composition. Hagen has less to play with in this sense with his rather more unbending instrument—though during the duets he performs some arrested plucking of the strings and abortive, percussive keyboard strikes. The recordings also include a subdued background of feet rearranging and wooden finger-block clattering. Up the Creek is, in short, a very interesting collection of pieces which is worth repeated listening to fully appreciate its sometimes hidden intricacies. Overall, Up the Creek is somewhat more satisfying than On the Wings of a Butterfly, exhibiting in a more overt fashion a sense of musical and textural rigour in composition. Nevertheless, both are fine, thought-provoking additions to the ongoing corpus of approaches which bring together the various and only indistinctly separate terms of Oriental, Western, Euro-American, traditional, classical, Early Music and New Music.

Jonathan Marshall

ABC Classics, 2005

Cat No 476 8064

http://shop.abc.net.au/browse/label.asp?labelid=3

Producing a novel dialogue between elements of the European high Classical period and contemporary post-classical New Music can be daunting. To further extend such a musical collaboration across the centuries to include early liturgical music—in this case Byzantine chant—is therefore no mean feat. There are precedents such as Akira Rabelais’ sparse sampling of Medieval chorale (Spellewauerynsherde, 2004) or Darrin Verhagen’s use of religious chant behind his Goth textures (the Witch trilogy, 1993-2000). Under artistic director Nick Tsiavos, Jouissance has produced a unique, lyrical and musically complex take on sixth century Byzantine chorale with contemporary fusions.

Producing a novel dialogue between elements of the European high Classical period and contemporary post-classical New Music can be daunting. To further extend such a musical collaboration across the centuries to include early liturgical music—in this case Byzantine chant—is therefore no mean feat. There are precedents such as Akira Rabelais’ sparse sampling of Medieval chorale (Spellewauerynsherde, 2004) or Darrin Verhagen’s use of religious chant behind his Goth textures (the Witch trilogy, 1993-2000). Under artistic director Nick Tsiavos, Jouissance has produced a unique, lyrical and musically complex take on sixth century Byzantine chorale with contemporary fusions.

Although recorded at the acoustically neutral Iwaki studios, producers Jim Atkins and Tsiavos have created a gorgeous sonic space within which the cycle sits. The chimed bells of master percussionist Peter Neville and the at times almost ‘basso profundo’ of baritone Jerzy Kozlowski rest within a richly echoing context, at once wide and deep, yet sufficiently shaped and tweaked to go beyond a simple replication of the reverberance of a Medieval cathedral. The recording is simultaneously seductive yet complex, far from the faux historicism of most Gregorian chant recordings. At their thickest, Neville’s chimes and bowed gongs sound like they could resonate to infinity.

Neville, Kozlowski and cellist Tsiavos are joined by soprano Deborah Kayser and shakuhachi player Anne Norman. The CD begins with passages of often highly syncopated singing from Kayser, answered by active contemporary instrumental responses. Norman makes the most of the special character of the shakuhachi: sharp, highly pitched accents and extended, stretched notes hover over the other instruments or make up short lead sections. Periods of sustained, strongly tongued vibrato feature within the most intense exchanges, such as the tightly controlled storm of instruments on track five (a Thracian dance).

Each instrument has a track in which it leads. Tsiavos presents a gorgeous cello solo, at once mildly Romantic in tone, yet with a rough, grating texture to the bowing, lying deep and hard within a hummed vocal wash (track eight), while on track 10 Neville fills the space with lightly buoyant timbres. As the tracks progress, the vocals eschew the tightly clipped enunciation of Kayser’s initial delivery to rise and glide over passages in a fashion more familiar in Early Music. A kind of questioning emerges with the shakuhachi, then the cello, speaking out after these motifs creating an enticing sense of non-resolution. The cycle ends with a minimalist rhythmic percussion and cello section underpinning soaring vocals.

There is an implicit narrative at the heart of the Byzantine motifs reworked here, which although related in the liner notes, remains largely opaque to modern listeners. This matters little however as the sheer gorgeousness of these works, tinged with a sense of divine tragedy, more than carries the cycle. In the context of so much spiky, acerbic New Music, it is a rare pleasure to find such a luscious new work.

Jonathan Marshall

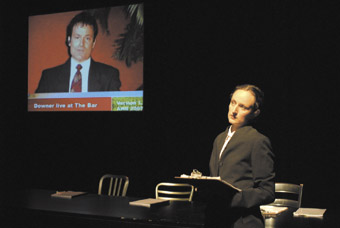

Presented by RealTime, Performance Space, d/Lux/MediaArts and the

Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council for the Arts at Performance Space, at Carriageworks, Sydney, Australia, August 21st, 2007, hosted by Keith Gallasch, Managing Editor of RealTime and David Cranswick, Director d/Lux/MediaArts.

This transcript has been edited for clarity and where the recorded dialogue became inaudible.

introduction

Keith Gallasch I’d like to welcome the manager of the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council, Anna Waldman to introduce Steve Dietz to you.

Anna Waldman In the visual arts there have always been over many decades some form of new media, and that the new, new media I believe is about questioning and lateral thinking and intellectual risk and artistic intervention—because many of us are paralysed by the control technology exercises over our lives and because we might like to shelter from satellite tracking and genetic testing and the twilight zone of the net and parallel universes. But also because art takes in a truly strange and wonderful domain that shapes our understanding of events, places and emotions, a forum like this is a rewarding event. And thank you Keith and Virginia [Baxter, Managing Editor, RealTime] and Fiona [Winning, Director, Performance Space] and David for organising and hosting it. We’re privileged to have with us Steve Dietz to help us explore the new worlds where control is within our grasp. Steve’s visit supported by the Visual Arts Board is part of our international media arts strategy, a focused program of visits and curated exhibitions we are working on at the moment.

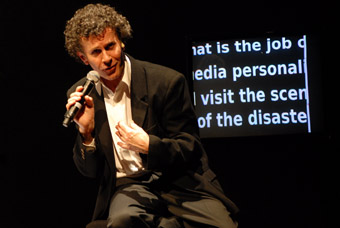

Steve was director of ISEA 2006, Symposium Zero One, San Jose. Between 1996 and 2003 he was curator of new media at the Walker Arts Centre in Minneapolis in the US, where he founded the new media initiative Beyond Line Art Gallery 9 and the Digital Arts study collection. He was founding chief of publications and new media initiatives at the Smithsonian Institute and the editor of the journal American Art. Steve has organised and curated many new media exhibitions including some of the first online exhibitions—Beyond Interface, net art and art on the net in 1998, Shock of the New: Art Historians and Museums in the Digital Age in 1999, the travelling exhibition, Telematic Connections, The Virtual Embrace in 2001, Database Imaginary in 2004 at the Banff Centre, and in 2005 he curated Public Sphere_s as part of Media Art Net in conjunction with ZKM exhibitions and, also for ZKM, curated the Fair Assembly web projects for the Making Things Public, Atmospheres of Democracy exhibition. Steve is also artistic director of the biennale Zero One, Global Festival of Art on the Edge in San Jose, 2006.

As you know, Walter Benjamin famously claimed that technology destroys the aura of the work of art, and Marshal McLuhan suggested that we always understand new media via the old media. So it’s good to know that Steve has positioned Zero One as an event where artists are making art, using technology [as they wish]. Steve has described his curatorial role as being polymorphously inquisitive. So this intriguing description should make for an interesting discussion tonight and I would like you to join me in welcoming Steve Dietz.

explorations

KG In one of your essays, you quoted Tom Stoppard, from his play Arcadia, saying, “It is the best of all possible times to be alive when everything we thought we knew is wrong.” Now, predictability as we know in new media art, and in the media in general with new technologies, it is just incredibly hard to project where things are going, and this has happened again and again particularly in the last 20 or 30 years. Has your own career been like the twists and turns of media and media arts developments? Has it been one of surprises, dead-ends, wrong turns and accidents? I know that when you started out you had some connection through Aperture magazine with photography and, in an interview I read, you said that your interest in new media perhaps sprang from aspects of photography and the relationship between text and image. So where did you get into all this, and when?

SD Well if I can just back up one second, I do want to thank d/Lux and Performance Space and the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council and Anna and David and you and everyone for bringing me out, and I want to thank Romany for making sure that I could tell my family that I’m not here on vacation…But it is a great honour and actually a lot of fun to meet everyone here and those of you who have had your 30 minutes [individual artist meetings with Dietz. Ed] or whatever with me, I do appreciate that. I know that it’s a tense process often but it’s been really enjoyable for me, and a great learning experience. I really appreciate this opportunity to have hopefully a more two-sided conversation.

In terms of my background and interests, I did go to art school and very smartly knew that I shouldn’t try and be an artist after that. But I was always interested in the combination of art and text, you know, sort of multiple things at once, and I think probably for many people around the circle here, the so called 'new media' was a place where you didn’t quite fit in as an architect or an engineer or a programmer or painter, and somehow this sort of combination of things was an amazing opportunity. And that was what Tom Stoppard [was referring to], that we didn’t know exactly what was going to happen but there was a kind of excitement and enthusiasm and it wasn’t about success in traditional terms, it was about exploration and energy and for me it was around text and images and that combination and photography is both an artform and a system of communication, and digital media was sort of that on steroids.

KG But it was web art in particularly that grabbed you?

SD What actually grabbed me was the CD-Rom. I saw it and I thought this is what I want to do, and I went back and sort of founded the New Media Department at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. But I think net art was interesting because it was, kind of oddly, a substantiation of a virtual world. It’s a kind of platform that one could talk about that historically I think didn’t exist quite in the same way until the advent of the Internet and especially the World Wide Web. So that’s where a lot of my early curatorial energy was focused because I think that for me one of the roles of the curator is to be a follower not a leader. There were lots of artists, I think, who were doing things on the net that were interesting to me and I wanted to make them interesting to both my colleagues and the general public.

KG You actually said at one stage, looking at websites was a lot like seeing a photographic image appearing in the fixer in the dark room where there’s a magical moment.

SD My background is in photography and there was the magic of the images appearing in this red light and I think that there was something similarly magical [here]. I was typing in VT, a Unix editing language, well not language but editing program, and you would sort of FTP it and there would be this thing on the network and it was like, like magic!

just art

KG Later on you wrote an important paper called “Just Art: Contemporary Art after the Art formerly known as New Media.” I was wondering, how did you arrive at the ‘Just Art’ position having been so heavily involved in the promotion of new media art? Was this a rhetorical point? In what way was it strategic, because in the same essay, although you say it’s “formerly known as new media art”, you defend artists against the charge of technophilia. You say, in fact, that new media art would save contemporary art because it would never be curated in the same way, and you say at the end, new media art won. New media art is dead, long live new media art. …. Are you having it both ways?

SD Yes, exactly. Well, I think that this whole question—what is new media art is a really complex issue and it’s nice to be with a sort of knowledgeable and sophisticated audience because so often the question when you talk to a newspaper or whatever, is what is new media, and how does it relate to the latest, you know, stock price of Google? It gets confused with a lot of different issues. I think that there is this kind of time-based sense of a lot of different media—photography, video—that at one point it’s one thing and then at another point it’s another thing. And that’s actually kind of a normal situation even though I think we treat it as somewhat surprising or abnormal. And so for a certain amount of time I was very interested in championing and understanding the sort of differences and the new possibilities and capabilities and especially network and computational based artwork.

But I think at a certain point…there started to be a kind of ghetto happening, a kind of division, of conversations that weren’t happening between contemporary artists and so called new media artists. And one of the things I write is that every single artist and curator I talk to says it’s not about the technology, it’s about the art. But still we put on these festivals and we put on these exhibitions where there is a lot of technology. It’s not clear exactly what the art is. So, what I wanted to do was two things: avoid the idea of assimilation, that certain new media artists are worthy of the contemporary art world, but at the same time, say, new media art is really fantastic art and if you’re at all involved in the present moment, we have to pay attention to it. And so in that sense, my argument is, and not everyone agrees with this, that the best way to understand contemporary art is though the lens of new media art. It’s ephemeral, it’s performative, it’s real time, it’s, you know, all these things that everyone is dealing with and new media artists in particular have been dealing with them for a long time. So it’s a bit of a stretch—in the real world, in the pragmatic world—to say that new media art is now. But I do think that a lot of the issues that we have been dealing with for however many years are ones that are also front and centre in the contemporary art world and so, we need to have that conversation. And then just one last sort of little coda, I think it’s also really important to understand, and this is my sort of reference to photography, there is a sort of communications world, a system, and the Internet is a communications system, it’s an economic system. There are all sorts of other issues, so it’s not about a hegemonic position. And there are definitely artists and processes that aren’t interested in being part of the academy, part of the museum, that there is a kind of digital culture, there is a kind of social, relational aspect to digital media that has accelerated the kinds of communications that happened to the letter and the telegraph etcetera. I’m not saying that everything is the same, but I am interested in the conversations that many really interesting new media artists, so called new media artists, artists formerly known as new media artists, can and should be having and vice versa, with contemporary artists and contemporary curators and institutions of contemporary art.

zero one

KG And so in your own festival, Zero One, in San Jose, what kind of art do you include if you want a more expansive notion? I know you’re written about this. You’ve said, okay, perhaps we need our ISEAs, we need our Ars Electronicas, but the exclusiveness of some of these things can stop this dialogue. So what do you do with your own festival?

SD Well, I think that the goal of the festival is to be a festival about contemporary art that intersects with technology but is not medium specific. So it has nothing to do with whether it’s a computer or projector or a network. It could be a painting, it could be a sculpture, it could be, you know, some version of nature. And so in that sense it’s a very open field. But I do feel like a whole range of artists are looking at how technology has impacted on the universe for better and worse over the past 40 years and to separate those artificially into media arts and contemporary art is no longer a very interesting proposition. So when I go to the Sao Paulo Biennale and see fantastic work and really interesting ideas and there are no artists who actually use technology in a compelling way, it’s depressing. And I go to a media arts festival and there are no artists who are self-defining as new media artists, it doesn’t seem like a future, it seems like a dead-end.

KG Could you explain that a bit further? What do you mean by at such an event, a new media art event where people are not defining themselves?

SD Well, I’m trying not to name names, like ISEA and Ars Electronica, but let’s just say that historically ISEA has not shown a Janet Carter, who does amazing locative media works, that are just mind boggling. So why not? As media arts producers and curators and institutions, we’re artificially ignoring really interesting artists because either they don’t self-define or they’re not medium specific.

Unidentified participant Or there’s a heritage aspect to Ars Electronica, which ties it into certain kinds of new music practices—is that what you mean?

SD Music’s probably the most interesting, the most porous aspect of new media art practice. I do think that music is maybe an example of a practice where the same musicians appear at media arts festivals and contemporary art festivals.

category shifts & overlaps

UP …I’m just wondering in new media art, if you drop the “new”, you’ve got media and art sitting side by side, or if you drop the “art” you’re left with media and various kinds of creative practices within the very broadly defined continuum of media practices you talk about and economic systems that are tied up in contemporary media. [Then there's] a kind of convergence which puts a mainstream television station into the same stream of distribution system and access system as a new media art work, consciously defined as such. I’m wondering what do you see as the bleed across all these media practices where what was not previously defined as consciously as art finds itself actually located within a spectrum of practice, or an art practice, or vice versa where art practices bleed into mainstream media practices where the territory between them blurs?

SD I think that’s a really good point. Art is another definition that changes. I used to have this discussion with the director of the Walker Art Centre that some of these practices hopefully really change our notion of what art is. And that’s the assimilation part, it’s not about 'now you are art as we’ve always understood it', but now you are all changing what an art practice is. There is also this other element and it’s a kind of curatorial thing. The Palais de Tokyo had a show in January, a competition for chainsaw art. And I don’t know whether that was Hans Ulrich Obrist's idea, but it was a curator looking at this outsider practice and bringing it in into the realm of the art institution. So there is historically that aspect of bringing practices that are interesting into the realm of the museum. To my mind, as a curator, that’s fine and that’s interesting and you can make an argument and people buy it or not. But what’s really important is for that not to be the apex; the ultimate goal that we’re looking to create (is) a heterogenous environment where artists can be political, and, the same kind of practice can have very different meanings in different contexts and that we not valorise only one practice over all others. That’s the most important objective—or fear, in a sense—from my point of view.

Mark Titmarsh I would have thought that the characterisation you made of artists in Sao Paulo not engaging with new media art in an interesting way, that the opposite of that would have been in ISEA. Maybe there are no media artists engaging with contemporary art discourse. And I get the feeling that the position you’re taking is that there needs to be some kind of rapport, which doesn’t exist as yet—a bridge between new media arts festivals and new media artists with contemporary art discourse.

SD I actually didn’t mean to say that it was artists at Sao Paulo. It was the curators who weren’t including the artists that could fit perfectly within their premises. And I also think the same thing is true and I talk to so many artists formerly known as new media artists who really view their practice as being about art or politics or whatever, but it’s not about the media that they use or the technology they use. Many new media artists are very cogniscent of their relationship to the ideas of the contemporary art world. It’s the institutions and curators that I think are keeping or creating the separation, for some odd reason.

art about technology

Lizzie Muller You were saying you’ve spoken to lots of new media artists who say their work is not about the technology, it’s about the art. But I wonder if that’s one of the distinctions that’s becoming a bit of a problem because if technology is someone’s medium, it might be fair to say that their art is very much about the technology, and that one of the problems I think is where that divide, that digital or that contemporary art divide comes because a lot of contemporary art curators are quite scared of technology, and about the kind of things technology brings into a gallery environment which include interaction, messiness, all kinds of irritating, kind of half-finished possibilities that are quite difficult to sustain in a contemporary art environment, or are felt to be difficult to sustain. Another possibility is that the division between art and technology has held for such a long time that if, as new media people we continue to say, it’s not about the technology, we are kind of refusing to allow our medium to be brought into contemporary art spaces, whereas if we started to say, actually it’s very much about the technology and we work with technology, as a material, that might start to create some of those conversations between contemporary and technological art.

SD I think there are probably several different arguments there but my experience is that most new media artists don’t feel that their art is about the technology, and I think Julian Moraito can talk about painting or Wayne Thibault can talk about painting and paint, but in the end, it’s a conversation that is never really about that in the same way, and so I don’t think that most artists think that art is about C++ or Flash or html or anything like that. I do think there is a larger issue on both sides, if we talk about sides, where technology is changing how society works and this is my sort of core argument. I mean, I really only have three arguments. And one of them is the whole idea of the computerisation of society, that the combination of computation and networks has changed the world. And the world includes art. But my experience, and frankly my own interest, is not that artists formerly known as new media artists are interested in their art being understood as being about technology.

KG Is it about the uses to which technology is put?

SD I think for many people, of course, surveillance is an issue. And that’s true in David Salle’s paintings of people falling in sort of non-horizon space. There is a kind of surveillance aspect to them that I think is equally the same as amnesia. Amnesia, where is amnesia?

Denis Beaubois It’s very interesting for me because I don’t think it’s an either/or argument, I don’t think it’s polarised like that. I think part of the debate about new media, in my understanding is, that it is a fluid thing, a developing field, something that is active, and that doesn’t necessarily or shouldn’t be pinned down by a medium. There are some practitioners who tend to work with alternative environments, alternative audiences, alternate technology and I think it’s all encompassing. So for me the debate about whether it’s technology specific, or not, it seems it’s limiting.

AW But our whole life, our environment, is described by technology. I don’t think art is about technology any more than knowledge is about Wikipedia, or research is about Google. This is just what defines contemporary life, in the same way there must have been different things that defined life during the industrial revolution. So it’s perfectly fine to be a painter in the 21st century—although most painters have complained bitterly that no-one is paying attention to them any longer—as it is to be an artist using technology.

LM Is it not possible to say that you couldn’t make an artwork now that wouldn’t be dealing with the impact of technology on experience, on one’s life? But that on the other hand some artists are really confronting that impact in an explicit way. And maybe that’s what joins together those artists that you’re talking about that come together at Zero One because, as you said, their art practices or artworks may kind of intersect with all kinds of different mediums but the uniting factor is that they all intersect with the technology. So there is obviously something about that intersection with technology which is very important and I think that we can’t get rid of it because otherwise, we might as well just say “art”, which I suppose is number two of your arguments?

SD There are two things I just want to be clear about for the record: first of all that is very well put in terms of how I would like to think about Zero One, because one shorthand way of saying it is: it’s not medium specific. And I think the other thing I tried to say at the beginning is that it is a complicated argument and I’m not trying to say that there is contemporary art sitting up here, and we’re all trying to be there. We have to actively support a heterogenous environment, the idea of experimentation and the support of new practices, and you know, those are really critical issues that can’t be ignored, or shouldn’t be shoved away. At the same time, I also think we have a certain responsibility, whether we’re curators or critics or artists, of not limiting ourselves to our most comfortable circle so to speak.

David Cranswick I don’t think there’s ever been a time when more of the general population have been more engaged with the substance of what a lot of media artists have been working with, that is, the internet, video, iPods, whatever. And I think that’s the really burgeoning thing is that the public are moving into the areas the artists have been already working with. The thing I’m thinking most about at the moment is the technology, which is the substance of what the artists are working with.

UP What was video art in the gallery can be now used as user-generated content online in that sense and, that from the media producers’ point of view, the rank amateurism of a lot of video art now becomes the rank amateurism of people participating through user-generated content. It’s interesting there is a blurring of this kind of what was once a kind of aesthetic practice is kind of a social practice.

DC But within that there are the beacons, amazing websites, which we all know and love, and pointing to them is what I do as a curator. And the challenge now is that—telling people that if you’re online all the time you can go ‘here’ and see something extraordinary. People now have fluency with navigating and understanding networks and systems—everyone has been drilled in the revolution that, say, Apple has brought to us. Everyone understands the networks that are there and are trying to work into that space, but again the artists have been working for decades now have been doing great stuff with this.

SD Exactly my argument—I would say everyone except the institutions and the curators, right? The argument is not with the artists, the artists are not the problem.

middle men & the new mass media

KG Perhaps we can just define this a bit. Let’s talk about museums, then perhaps about festivals, and then about life! Suddenly it’s all out there, it’s Second Life, YouTube, MySpace, and radical versions thereof. Steve, you spent some time in a famous museum, and had some interesting times, and you’ve written about this, what you hoped museums would become. Wouldn’t museums, instead of being platforms for representation, become platforms for reproduction, platforms for circulation of new works instead of just staging them in a privileged space? Now, have they done that?

SD Well, no, I don’t think they have. I mean some have and some haven’t. I think sometimes they do it and sometimes they don’t. But I don’t think the overall picture has sort of shifted significantly in the direction that I hoped…I actually think that there’s really still a valuable role for the middleman, so I love d/Lux’s little selection of ten machinima films on your site. And you know, I don’t feel that’s the only selection or there’s nothing else out there, but that was a really interesting selection. And so I think that museums and art institutions have a perfectly legitimate role to say pay attention for this reason. But they need to say for what reasons, and it can’t be that that’s the ultimate goal, that there aren’t other kinds of processes and places that are equally important, whether YouTube or Facebook, or you know, your kitchen! But I think, on the face of it, there is no adequate generalised appreciation of the amazing work that artists formerly known as new media artists are doing. And that’s you know, bordering on criminal.

video precedents

Stephen Jones There’s a historical parallel. The video art scene has gone through almost the same trajectory of acceptance, or failure of acceptance and then acceptance to the point where it is now pretty much mainstream, but it started 15 years or so ahead of network art, well maybe 20 years ahead of network art depending on how you date it. The experience is awfully similar. It went through a whole period where it was essentially a political attack on broadcast television. There was a period where it was a formalist kind of exercise about what the medium, what the technology as a medium was capable of doing. Eventually the DVcam becomes absolutely ubiquitous and you get all the sort of street video stuff that’s going on. You still get referencing back to beautiful, technologically interesting things. You get references into even more deeply what, prior to video, is the sort of modernist work that Daniel Von Sturmer is doing for example, or you get the sort of technologically investigative stuff that Daniel Crooks is doing.

UP Bill Viola?

SJ Well at the very point where Bill Viola has become absolutely mainstream. So, you’re quite right, curators are followers and it’s just that the lag time is quite long, because there is a great deal of technological understanding to have to grapple with for curators. Without someone providing massive amounts of technical support in the really early days there wouldn’t be a video scene now—support from various people like myself who came in to museums as needed. That kind of development has reached a point where Roslyn Oxley and Sherman and Schwartz galleries are selling video work as a mainstream, very successful product. And some of it is extraordinarily beautiful and some of it isn’t. So I think that new media is [going through the same process]. Well, let’s not call it new media because video was new media 30 years ago. But network art and web art are going through a similar trajectory of development and acceptance in museums. There have been seriously important early events like Mike Leggett’s Burning the Interface CD-ROM exhibition at the MCA [1996] and 010101 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2001—a bit mainstream to my mind, but you know. Artists pursue questions of curiosity and experiment and investigation, and they can be political, and they can be about wonder, and they can be about science, and they can be about technologies, and they can be about all kinds of other things that we may have. And what we are really doing is trying to provide subjectivities to other people that envelop them or they can embrace in various ways.

SD Bill Viola is certainly a blue chip artist but I’m not sure that DeeDee Halleck the founder of Paper Tiger Television would say that video art has been accepted quite in the same way. I think maintaining space and possibilities for alternative practices are also a really critical element that’s not as clearly solved by time, because there are these really strong, hierarchical, economic structures that militate against those kind of practices.

SJ That’s about frameworks, and critical frameworks, and about the politics of media production and media presentation, and so Paper Tiger is an extremely radical operation—it would in fact probably be horrified to find itself accepted within a sort of mainstream framework.

battling obsolescence

KG Tell us about the Guggenheim Variable Media Initiative. Because the whole notion of “obsolescence of art that seems out of date before it becomes historical”—to quote you, or someone who quoted you—seems to be a very pertinent issue about making art. Is the Guggenheim type of initiative common? Or is it just a one-off?

SD The Variable Media Initiative is a small consortium—the Langlois Foundation has been supportive of it, but I noticed that in the next month there are five different media archaeology symposia around the world. It’s clearly a topic of interest and importance—basically it’s because everyone who’s going to run their videotape through the machine one more time is probably the last time. So that really makes you think about these issues. But to me the most interesting thing about the Variable Media Initiative is precisely that it gets the medium out of the equation—it’s about the intent and it’s about context, it’s about framing…but it really has nothing to do with the medium. So it’s equally applicable to Dan Flavin, to Jody, to Meg Cranston and to any new media artist. And I think that’s a really interesting way to think about it.

KG So what are they actually saying to an artist? Here’s your work, we might not be able to run this in five years, so what do you want to do?

SD Yes. So there’s an interview process where they go through a set of questions and say—again it’s easier to look at the historical examples. They might ask Dan Flavin 'Is it more important that you can get a red light bulb [you can buy] anywhere or is it important that it’s red dye number 2? And red dye number 2 was outlawed but the Guggenheim and the Whitney have this huge stockpile of red dye number 2 when presumably his original intent was you could go to the hardware store and get it. So I think that, as a sort of litmus test, it raises these issues of what’s the best format or format that you would like to allow your work to be presented? Does it have to be 35mm film? Can it be transferred to DVD? Can it be projected—all those kinds of issues. So that’s the goal, which seems to me to be absolutely appropriate.

future curations

DC We were talking earlier about pasts; now let's talk about futures. What’s on your mind for five years from now in terms of your curation and how you are developing festivals? Where are you heading? What exciting things do you see on the horizon?

SD I would like to see this happen, I would like to see the artists that I care about—that I have to go to two different kinds of worlds to see—together, and have these interesting fights, and drinks at the bar. I see five years as an ambitious goal for that to happen. On a curatorial basis as well, I can see, obviously there are lots of concerns, issues like the environment, and how artists are interested in intersecting with that. But it’s not about what I’m interested in, in that regard per se. But if artists are doing it, then I’m interested in supporting it.

DC We've talked with you about ecologies and GPS and locative media. In recent months more and more people, and organisations like the City of Sydney, have alerted themselves to the fact that there are new channels, and they’re interested in how people traverse the city and how we might communicate with people, say within an arts festival, or a biennale or so on. I’m saying, well I know there are artists who have been working with these ideas for some time. And these [organisations] say, well I never knew about that. And they are really interested in the tool set that a lot of artists have developed and have brought into play in utilitarian environments. Perhaps public sector support is fading away and the private sector are more interested—coming out of San Jose, I guess you get a lot of that, because you’re working in the hot bed of the drivers of the economies of technology. Thinking about five years from now, I’m not asking you to name the technologies [that will dominate] but is it GPS or some super network? Where are the movements do you think?

SD This gets back to my three ideas. I was talking to someone here earlier about Second Life as an instantiation of a larger issue around virtuality and networks. And so at one level, I couldn’t care less about Second Life per se. It’s a particular thing of the moment. So I do think that, you know, networks and computation are critical and what’s happened is that there’s this convergence– and I’m sorry for repeating what everyone already knows—of mobility, the power of computing and the global network always being available. And that creates new possibilities, and I think that the larger issue there is: how do we think about a universe that’s always online everywhere, all the time. And yes, I absolutely think that that’s a direction that’s happening, whether it’s the iPhone or the Palm Pilot or GPS or a new set of satellites that the Chinese will put up into orbit—I don’t know, but I think that will change things. But the interpenetration of the network of computation into the physical world is only going to get more and more dense, and artists are going to do more and more interesting things with that.

human filter: the archiving curator

UP Artists can be completely feral and viral as well as put in a box—is that liberation or a problem? Do you aim at gaining many small audiences or try and aggregate people towards larger spaces where things can be found? How do you work as a curator trying to discipline the network?

SD Well, in terms of the network, this is where I do idea number three, and one of my models for this is a site called Runme.org [www.runme.org]. It’s basically a very simple structure where Runme define their field as software art. Anyone can submit their project to Runme so it sort of goes through that first filter—is it software art, or is it just a Flash animation? When I say filter, it’s a human filter. And if it’s software art then it goes into their catalogue of art. Then they have a privileged group of people running it, and if one of those people writes a review of it, in other words curates it, it’s going to go to the second level. So I think this notion of combining the archive with the curator is actually a really interesting model for the network. Because I want to be able to go and look at any machinima that I want, or I like to see what d/Lux did. I like that, as long as I know that that’s not the only imprimatur that I care about. And so I think that there is a role for curation but it can’t be exclusive, there have to be hooks for people to find their own paths.

UP Equally, of course, you could go looking for a ringtone and carry away a piece of new music. So you could be a punter with no interest in art, and stumble quite by accident across something pretty amazing.

SD Absolutely.

AW But that’s rare. Most people are still looking for gatekeepers, or some formal validation.

the co-creating audience

KG But there is also an audience increasingly expecting to be not an audience but a participant and even a co-creator. The new mass media such as Youtube and Myspace and Facebook are already leading the way in this, and artists are thinking, how can I get into it.

LM Even through there will always a role for gatekeeping, Steve, wouldn’t you say that a curatorial role is more than just picking, it’s more than selection, and what would you say was part of the curatorial skillset in new media art, beyond just picking the best of?

SD I think what I see as providing a point of view is absolutely, fundamentally a total requirement of the curator, or the curatorial process. It’s not exactly the same as transparency but I think it’s a responsibility. I think on a sort of pragmatic level you learn how to help navigate the bureaucracy. So, let’s not talk to the director, let’s talk to the IT guy, you know, he can do it in two minutes. But I think fundamentally it’s really about point of view, and there’s probably some ethical issues there too.

LM But coming back to Keith’s point, the audience expects now to have more of a role in media art than ever before, and wants to be involved at the point of the museum. And, as you were saying, the museum is no longer just a place for presenting work any more, it’s a place for collaborating and producing. And consequently the curatorial role has to change a great deal—working with the audience and with the artist.

SD Yes. One of the things I wanted to bring up earlier is the notion of the open platform and the artists and the audience as the participants co-creating the work. Again, one of the things that I’m interested in is this idea that Steven Johnson [author of Emergence, Pengin Books, 2001] has written about, the greatest challenge in the 21st century is how do you put enough parameters on an open system that you get something interesting out of it, without over-determining it? So that’s why I like this Runme.org model because it enters an open system where anybody who meets a basic criteria can be part of it, and there’s a kind of selection or critical appraisal as part of the process. I think it’s not so interesting to say anyone who uses, say Mark Napier’s potato head and draws a drawing is somehow [creating art]…How do you differentiate the result of that software artwork from the software artwork itself? It is a difficult question, and I think some systems are much more successful. Paul Serman’s telematic couches are amazingly successful I think. Other kinds of projects that are open and that the audience completes are like ‘Kilroy was here’!

ML In Runme you’ve described a bit of a closed system. The people who get to write about the works that are submitted, who are they? And how do they get there?

SD Exactly. I think they get there because people in the end respect Amy Alexander or Alexei Shulgun or Thomax Kaulmann or Olga Goriunova…And they respect them because over the past 10, 15, 20 years their opinions have mattered. I guess it gets formalised around the notion of a reputation economy, but it’s not exactly a closed system. But also it’s not a completely open system. I mean, people matter.

art embedded in industry

LM Funding [for this kind of work] has been reduced in Australia and artists have had to find other places to conduct their practice and one of the places has been the cross-disciplinary areas [for example, artists working within the commercial, industrial and scientific sectors]. The question therefore comes about—and it’s one that Mark Amerika has raised in his recent book—that there are considerable dangers in this kind of approach, which he is alarmed about.

SD Coming out of Silicon Valley I think there’s what I would call ethos around the idea of the artist in the research centre, that somehow we’ll end up with better science and better technology if only the artists could be there at the origin. And I’m agnostic about that. I think amazing projects have [come out of it]. I always point to the Ben Ruben collaboration with a scientist from Bell Labs to create the Listening Post. But I think that 10 or 20 or maybe 100 people around the world could be embedded in labs, and of those 100 people, if 10 of those create really interesting projects which may or may not be successes, that’s a huge success rate. So that’s ten projects. What interests me is when that research technology gets commodified, and can be used by almost anyone. And commodification can be $10, 1 cent, a thousand dollars, even ten thousand, but there is a really broad practice, or landscape, that lots of people can act on. And so in that sense I think the open source movement is at least as important, if not more important, than getting a research project with an artist in a lab as a goal to move the field forward and to make the world a more interesting place. I think commodified technology is—and commodified can be open source—I don’t mean patently owned—is a very productive terrain. And the research in the lab, it’s less compelling to me personally.

UP To a degree the museum has become commodified. If you can see it on the mobile phone, everything by the mobile phone, then the platform for engaging with the work as a commodity is regularly accessible.

SD No, no, that’s exactly my point! As soon as we get away from the idea “did you see what that person did on a phone?” to look at what that person actually did, and it happens to be on the phone. It’s like Nam-June Paik got a Sony portapack—isn’t that amazing? But now everyone has an HD 3-chip video camera, and actually some really interesting [works] are being made, but not because they own the camera. It’s when everyone has it, it no longer matters that it’s the technology; it’s what you do with it.

UP But now, rather than with the Guggenheim, you can negotiate with HP for your next project.

DC That’s all right!

SD Artists should have the ability to go wherever they need. Artists are very smart about using a context and the ways that it makes sense to them, and that’s what we need. To me that’s what institutions need to be open to—to being used by the artists, and not controlling the artists.

transvergence

MT I thought you created a really interesting conceptual challenge at the beginning, which I kind of visualise as a Venn diagram where you have two circles overlapping, where one is new media art and one is contemporary art. And they overlap in one small area and how do we unpack that overlapping. But we seem to inevitably fall back into the new media circle on its own, and talk about technologies and open sourcing, and the internet and Google and so on. I guess I’m just trying to bring it back to that overlapping area. You seem to be interested in stripping away the technology: let’s not talk about technology, let’s talk about the idea, and purity, let’s talk about what the artists do. I keep thinking, you know, what you’re doing or making is intimately tied to the mobile phone. It is more than just what they did on the mobile phone, in many ways the mobile phone is indivisible in the interacting, the making and the doing of what appears on the mobile. So is there some kind of split there where you want to strip the technology away so that we can equate ideas of Dan Flavin and someone working on a mobile phone, yet you can’t do it. Can we find that overlap with real people and strip away the technology at the same time?

SD It’s a really good question. Two comments I guess: one is I wouldn’t want my position to be that this work is intimately connected with this technology. Of course that happens. Why is it that we can acknowledge Wayne Thibault’s relationship to paint without ever thinking that his work is about paint. There’s some kind of gap there that I don’t fully understand. The other issue is—sorry, I don’t really have this fully formulated—but there is the idea of the Venn diagram, which is how we think about multimedia, this intersection of text and image and sound and music, and in the middle, there’s multimedia. But there’s this other way, and in Zero One last year we called it “Transvergence.” The idea was you have two disciplines, which for now are called new media art and contemporary art, and what happens is, the practice of one perturbs the practice of the other and changes it, but it’s not so much about a kind of mechanical overlap that’s sort of changing how they relate to each other. And I don’t know if that’s in the end useful, in terms of your question. But the question I keep coming back to is why do we talk about the technology of sculpture or video or painting without ever thinking that that’s what it’s about, but every time we talk about cell phones and html and C++, somehow, that’s what it’s about. I really don’t get why that happens.

MT Well, there have been times when it was exactly like that—when we go back to, say, Greenburgian formalism, when painting was about the paint and the canvas. And those issues, and that kind of formalism has been messed around with, and played around with an infinite number of ways ever since, so it does happen.

SD I’m not sure that formalism is the same as media—maybe. But so what I would say is that we really have to get away from a unifying sense of what a medium is.

the trouble with 'new'

LM Is this perhaps where the term “new media” is still useful? Because it designates the idea that the artist is struggling with the emergence of some new kind of technology which is impacting on practice, so a new kind of paint, or equally perhaps the emergence of a printing press or something like that, or like the emergence of the novel in the 18th century, or other kinds of moments where makers developed a kind of new form to go along with the technology, and that’s why the term new media is useful. Because the internet no longer is a new medium, but perhaps mobile phones and the different capabilities which are emerging now still are, the term “new media” describes the kind of avant-garde of experimentation with technology that ushers in new forms.

SD That’s a seductive argument, but the thing is, mobile phones—I mean, how new is new? And [how can the] new [be equated with] avant-garde. Avant-garde seems to me to be a much more philosophical position than 'new.' And then there is this other thing that I sort of call “the powers of ten problem” which mostly relates to code—that someone’s idea of what code is could be assembler, or C++, it could be Flash, it could be processing—and it's the same thing with 'new.' To a lot of people the computer is new. So I think in that sense, the impulse behind this idea of experimental is an important one and I understand and agree with that. But somehow 'new media' seems inadequate. And also does that mean that if I’m interested in new media, I can no longer be interested in the web because that is old now, so I really have to only be interested in the new things.

SJ Surely the point is that we’re experimenting with ideas and notions and occasionally those are technological notions, but we are actually experimenting with curiosity, and investigation. And it’s kind of independent of the medium, and most of us, I’m sure, have worked in a number of different media in the time we’ve been making work, and each piece is sometimes per se about the work and sometimes it’s about the technology, but mostly it’s about trying to communicate some other subjectivity and to make available to others your own subjectivity in one way or another. And the media, be it new old or indifferent, be it paint or photography or digital photography or video or mobile phone or biology, as it’s become in some areas now, is actually more about ideas and investigation and curiosities and political issues and trying to transmit that. And that the medium per se is, I guess we’ll say, irrelevant.

SD Part of what I think you’re trying to say, if I can put words in your mouth, is that when a new technology comes along, it can mean a new printing press, it actually expands and there is this sort of symbiotic, Mcluhanesque relationship to technology where we can actually imagine new things, and so for me, computation actually does give rise to all sorts of new things that weren’t equally previously available.

SJ Yes, but the stimulus of the technologies is as much a thing about which one can be curious, and investigative and developmental, as it is about Prime Minister John Howard and making a mess of him. It is exactly that. It’s that loop of relations that develop and how that evolves and grows, and shifts and changes and modifies your thinking, and how your thinking can then impact on the rest of the culture. I mean, putting a book out there is a really effective means of infecting the culture with a whole new set of ideas and shifting and changing the way people think about things—some people anyway.

technology's cultural impacts

Kate Richards It certainly seems there's a historical specificity in the incursion of technology into art around engineering and computational technologies. For example, in the 19th century there was a little kind of meme going, 'Oh, gee you’re not really an author but you can vanity publish.' So it’s almost like, with the technologies that we use as new media artists, both software and hardware, the enormous proliferation of those, the commodification of them and how they were sold to us from the 70s onwards, creates a very historically specific situation. For example when those earlier softwares came out it was like, buy something like CorelDRAW and you can become Da Vinci, or get a handycam and you can become De Palma, and there’s lots of reasons and I’m sure we’ve got lots of ideas as to how that has emerged, but there is an historical specificity that we haven’t really seen before and I think that’s one important aspect.

I think there is also an historical specificity with the Me-generation. For millennia we have seen individuals with a creative process, and whether that involves being on a ship and taking a whale tusk and inscribing on it, or whether it involved hammering out a coin and making a medallion for your loved one at a remote location, people have always done that kind of thing. But what we’ve seen in the second half of the twentieth century is the whole proliferation of the individual, the cult of the individual—you’ve got your own right to express what is actually not a personal expression, it’s a broadcast expression. And I think that’s kind of a subtle philosophical thing that has also reinforced the ubiquity of the individual and it completely underpins the justification of user-generated content. I think that’s all absolutely fantastic—every individual has a broad right to have creative expression in how they live their life. They don’t have to be professional artists.

And the third point: what is a technological avant-garde? I believe that there always will be an avant-garde, it’s just how the definition shifts and I think, in some ways today, for artists working in media or technology, the role of the avant-garde goes back to some earlier idea of an avant-garde, say mid 20th century, where the aim is to critique both through your subject matter for want of a better term, and through your application. SymbioticA's work really can be very strongly defined as conceptual—ideas and their conceptual documentation. But they have a very, very important role in illuminating for both a more literate and less literate audience a whole phalanx of crucial political issues around biotechnology and so on and so forth. And so, as a technological avant-garde these days we have to continually reinvestigate what that terms means, and I think today it can actually be critiquing and drawing attention to some of the ubiquitous technologies that are around. It may not actually be inherent in the form of the work, which it has been in the past, and that will probably shift again, but I think there is a lot of historical specificity in the connection between art and technology.

DC And the economies of it are unheralded.

KR Absolutely! I’ve been on the board of ANAT and when they formed it was genuinely grassroots and it came out of a city that has had a lot of centralisation and bureaucratisation of technological development like the military and so on. It was 15 years ago when artists working with say robotics, or ubiquitous networks, were neck and neck with the commercial industries. That’s not the case anymore, the commercial industry—anything that you can think of has been done! Buy it off the shelf! That’s not the point. We cannot compete at that level, we have to find applications, we have to find appropriateness, we have to find ways to revisit content and all those sorts of ideas.

KG We’ve traversed a lot of terrain and we can continue, as always on these occasions, to talk over food and drink. My big question, and Virginia has often asked this over the breakfast table: Keith, where are we in the evolutionary trajectory? One new media writer has said that thanks to the mobile phone the human thumb is going to grow way out of whack in the younger generation. I like something that Steve wrote, where he said, “It is not hard to imagine that an anthropologist of the future examining 20th century artefacts and interfaces of the digital age would have to postulate a being with at least 20 digits, if not several hands, myopic vision, no hearing except for extremely loud sounds, no sense of smell or touch, perhaps a large cranium but only vestigial lower limbs and a very large bottom.” And on that happy note, I would like to thank Steve Deitz for being with us tonight.

Further information about Steve Dietz can be found at www.yproductions.com

A VITALLY IMPORTANT CHAMPION OF NEW MUSIC IN AUSTRALIA FOR 21 YEARS, THE ELISION ENSEMBLE STAGED THREE

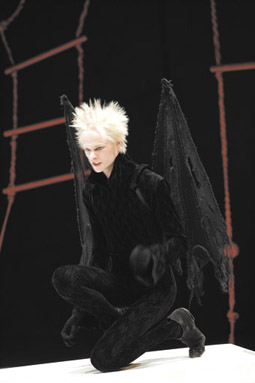

Marilyn Nonken, Elision Ensemble

photo Sharka Bosokova

Marilyn Nonken, Elision Ensemble

CONCERTS IN MELBOURNE AS PART OF AN EXTENSIVE NATIONAL TOUR, INCLUDING WORKS BY REGULAR COMPOSERS LIZA LIM, JOHN ROGERS, RICHARD BARRETT AND CHRIS DENCH, AND ESPECIALLY FOREGROUNDING THE WORK OF US COMPOSER AARON CASSIDY AND POLISH COMPOSER (AND SOMETIME AUSTRALIAN RESIDENT) DOMINIK KARSKI.

ELISION players are renowned for bringing off difficult and inaccessible work, often in association with visual and other art forms. As well as showcasing some demanding new composition, this season emphasised clarity and virtuosity in instrumental performance.

vca, university of melbourne

The VCA concert comprised mainly solo performances of works that emphasised playing technique. This was evident from the opening work, the premiere of Dominik Karski’s ethereal open cluster M45 (2003), which was inspired by the constellation Pleiades. For amplified bass flute, it explores fully the instrument’s sonority and timbre, receiving an enchanting performance from flautist Liz Hirst. John Rodgers’ fiery Ciacco (1999), personifying the hog from Dante’s Inferno, is no less demanding, and bass clarinettist Richard Haynes was superb, ably shifting from the highest to the lowest pitches in consecutive notes and producing the multiphonics and overtones that evoke the snorting, squealing and howling of the monster of hell.

Violinist Susan Pierotti gave us Helmut Lachenmann’s Toccatina—Study for the Violin (1986), which requires the performer to pluck, poke and prod the instrument—everything but conventional bowing. Composer Liza Lim’s two works—Ming Qi (2000) for oboe and percussion, and Shimmer (2004) for solo oboe—make great demands of the oboist. Ming Qi, inspired by a Chinese tomb, is an intense but engaging work with a forceful oboe line, wonderfully carried by Peter Veale, which overlays the measured percussion. ELISION’s Artistic Director Daryl Buckley suggested that the VCA concert was intended to emphasise the timbre of the instruments and solo virtuosity. The recital had the flavour of a masterclass, demonstrating the musicality that can be achieved through unconventional playing techniques. Listener attention shifts back and forth between the composition, the playing and the resonance and character of the instrument itself.

australian national academy of music

Buckley introduced ELISION’s ANAM concert by coining the word ‘hypervirtuosic’ as an appropriate descriptor, and it is. The two performers—Haynes, on clarinet and bass clarinet, and Carl Rosman, on clarinet and contrabass clarinet and, in two works, singing a falsetto alto—brought extraordinary dynamism to their performances. Such music couldn’t work without this level of musicianship. They opened with venerable US composer Elliott Carter’s Hiyoku (2001), an engaging clarinet duet with intertwining melodic lines. The evening also included the premiere of Chris Dench’s absorbing new work The Sum of Histories (2006/7), for bass and contrabass clarinets, which was inspired by physicist Richard Feynman’s term for the multiple ways in which sub-atomic particles can decay. Scored for the two largest of wind instruments, which are rarely used for solo performance, The Sum of Histories is a poetically lyrical work, stentorian but finely controlled.

Two knockout works were those in which Rosman exercised his vocal showmanship: Aaron Cassidy’s I, purples, spat blood, laugh of beautiful lips (2006/7), another premiere, and Richard Barrett’s Interference (2000). Cassidy’s piece, for unaccompanied high male voice, requires the performer to monitor a computer-generated random pitch line through an earphone and sing that line while pronouncing fragments of words derived from texts by Arthur Rimbaud and Christian Bök. Cassidy’s work addresses their translation and, in the absence of conventional verbal meaning, Rosman’s declamatory voice delivers a powerful emotional impact, extending the consideration of verbalisation and sound poetry since Kurt Schwitters and the Dadaists. The randomness of the pitch line ensures the work is never rendered the same way twice. Barrett’s Interference (2000) is based on a text by Lucretius and is set for falsetto voice alternating with contrabass clarinet and accompanied by kick-drum, and Rosman’s theatrical one-man-band effort is electrifying.

abc iwaki auditorium

This ABC live-to-air concert opened with Genevieve Lacey’s rendition of Liza Lim’s delightful weaver-of-fictions (2007), written for the Ganassi recorder which was popular in Renaissance Venice. The recorder is a larger than conventional one, with a sound approaching that of the shakuhachi. It can render gentle, mediative lines with a rich sonority and support compositional gymnastics including clearly articulated multiphonics. The instrument used is an Australian made alto and hopefully its revival will stimulate further compositional interest. The concert also included Cassidy’s asphyxia (2000) for solo soprano saxophone (Haynes), a physically demanding work that incorporates into the musical material playing techniques such as breathing through the instrument and fingering notes without breathing, and legendary US-based UK composer Brian Ferneyhough’s dramatic and highly complex La Chute d’Icare (1988) for clarinet (Rosman) and the Ensemble.

The central work was the premiere of Karski’s larger ensemble composition, The Source Within (2006). Commissioned by ELISION, The Source Within is, in effect, three quintets performed sequentially, each of which comprises three different quartets of instruments together with piano (Marilyn Nonken)—firstly, flute, guitar, harp and violin; then clarinet, contrabass clarinet, horn and cello; and finally, trumpet, trombone, oboe and percussion. Karski’s work is intense, evocative and demanding for performers and audience, each movement establishing four instrumental lines that build independently on the piano element. The complex and often contrasting voicing produces some unique sonorities and textures. The ensemble works draw together the extreme techniques of the solo works, demanding virtuosic playing to realise their musicality, and under French conductor Jean Deroyer, ELISION carry off these pieces wonderfully.

Concerts such as these consolidate the musical languages that emerge from compositional and performance development, and, especially when supported by radio broadcasting, strengthen public appreciation. Buckley’s thoughts behind the programming for this series were to bring together the musicians (many of whom are often overseas) and the composers, and to showcase particular instrumental combinations and techniques—an interweaving of musical ideas. The new works from Karski, Lim, Dench and Cassidy are terrific, and contrasting them with the more established Ferneyhough and Carter works identifies some current directions in composition, Cassidy for example incorporating unconventional performative techniques and Karski devising elaborate formal structures. With the predominance of wind instruments, the compositional use of controlled instrumental multiphonics and the emphasis on timbre are consistent threads.

ELISION Ensemble, Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne, May 22; Australian National Academy of Music, May 24; ABC Iwaki Auditorium, May 26

RealTime issue #80 Aug-Sept 2007 pg. 52

© Chris Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

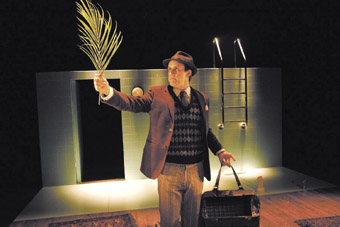

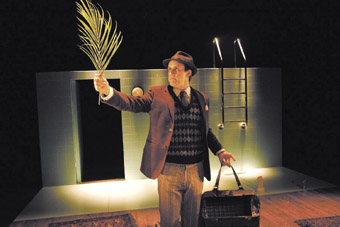

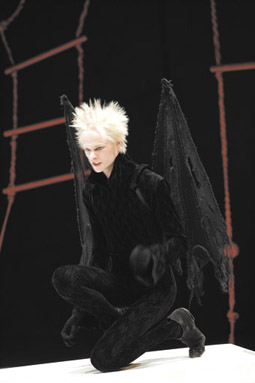

Eamon Flack, The Goose Chase

photo Bohdan Warchomij

Eamon Flack, The Goose Chase

THEATRE CAN BE HARD, ADULT, WORK AND FOR THAT WE SHOULD BE GRATEFUL. THE GROWN-UP DEMANDS OF A NIGHT AT THE THEATRE OFFER A RARE ANTIDOTE TO THE UBIQUITOUS TELEVISION, WHICH HAS BEQUEATHED US A TEENAGER-ISH MODE OF ENGAGEMENT CHARACTERISED BY WEAK ATTENTION, MILD DISINTEREST AND POOR POSTURE. UNLIKE THE MOVIES, WHERE OUR EXPECTATIONS AS VIEWERS ARE LARGELY GENRE-DRIVEN AND FRAMED BY A COMBINATION OF MARKETING AND REVIEW, THEATRE PROMISES THE INTENSELY UNEXPECTED.

But with intense engagement comes the risk of intense boredom. It is a singular state, the boredom of theatre, irreducible to other kinds of boredom. Is there a word (in German perhaps?) for the muscle-clenching, teeth-grinding experience of being stuck inside a theatre with an hour and a half behind you, and another 50 minutes in front?

Two recent productions in WA offer an opportunity to reflect upon the intense experience of theatre.

Matthew Lutton has emerged as a powerful force in West Australian theatre, both through his role as Artistic Director of Black Swan’s BSX Theatre and in productions with his own company, ThinIce. In the first half of Lutton and Eamon Flack’s recent The Goose Chase, I was thrilled to get to work, grateful to be given a grown-up job to do. There was no doubting Eamon Flack’s energy and skill as he flipped between era and character. The script was witty and insightful, and I wrestled happily with the tricky parallelisms established between Edwardian detective Edward Blunt, struggling to find his identity, and the contemporary Edward Taylor, young, gay, expatriate, desperately seeking a new plot for his next novel while holed up in London. I was moved by the drama of a young Australian author struggling to locate a subject for his writing within a universe which objectively promulgates postmodernism and globalism, but which subjectively robs him of reference and roots. At last, I thought, an original theatrical production which is dialogically engaged with issues that matter to me, to us, here in the State of Excitement, in the Land of Opportunity. Hurrah!

But, alas, interval and then the befuddlement of devised theatre. What appeared in the first half to be an actor inside an act, increasingly proved to be an actor putting on an unnecessary act. In scenes set in Singapore, the contemporary Edward rediscovers his ‘roots’, travelling back to his family home. The performance collapses into autobiographical sentimentality, with a tedious parody of a Malay trader on the beach adding nothing more than proof that the actor can do accents. What had been a fine balance between Shandy-esque digression and narrative focus now spilled over into—well, to put it bluntly, boredom. Excruciating boredom. Boredom raised to the degree to which I had been formerly engaged. Where was this goose chase leading? And if nowhere, and for no good reason at that, what was the point of working at it?

The sad thing about The Goose Chase is that it broke its promise to the audience. It was very nearly very good, but in falling short it proved its reputable devisers to be further from home than most had hoped. The most telling moment came in the epilogue, where the actor stepped out of frame to offer us a faux resolution which jettisoned the complex, dialogic concerns of the first half (where do we belong? does the local matter? how do we straddle the commitment to place and speak beyond that place?) in favour of a pallid ‘we are one’ individualism. Teeth clenching indeed. But which is worse? To have no idea where you are headed, or to have no interest in anything other than the destination?