Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Split Records splitrecCD 17

http://www.splitrec.com/

Sydney-based ensemble The Splinter Orchestra has made a name for itself in recent years for live improvisations, particularly at events such Liquid Architecture and through the landmark ABC TV series Set (2006). This is the debut, self-titled CD and is significant both in bringing recordings of the ensemble’s work to the public and in reframing its oeuvre through the process of recording.

The CD contains five tracks in all. The first, simply entitled First Play, opens quietly with a long, barely audible drone at very low frequency, the other instruments progressively entering. The performers play quietly and the sound gradually builds as each instrument’s distinct voice emerges. This is complex music demanding careful attention. The second and fifth tracks are entitled First Tutti and Second Tutti respectively, indicating that the whole ensemble is joining in, whereas other tracks are free improvisation, where individual performers might or might not contribute, depending on what develops.

First Tutti opens frenetically. Each performer seems to work through tightly prescribed idioms resulting in an impenetrably dense layering, but within a more restricted dynamic range than that of the first track. Less lyrical and more monotonal, the combinations of sounds produce interesting hybrid textures. There is a long trombone drone in the background, which morphs into a hypnotically rhythmic whirring sound as the piece quietens towards its conclusion. Though developed from a composite of disparate noises, the piece gains a level of coherence that suggests an intimately shared sensibility.

Track 3, Second Play, opens quietly with teasing arpeggios at the top end of what sounds like a prepared piano. Other sounds are progressively layered over it and a restrained, minimalist lyricism emerges. Again the piece quietens towards the end, some electronics closing it out. Third Play commences almost imperceptibly and gradually gains momentum. Overall, the music is dense but elegant and restrained, slowly seducing rather than forcing itself on you.

The interest in such music lies in the extraordinary lyrical complexity that emerges from the combinations of instruments, even if they are playing simple, repeated motifs. It also lies in the almost infinite variety of timbres and textures that are generated from the instruments as they combine. Musical development occurs through the blending of instrumental voices and the players’ responses to the overall effect, rather than through programmed structures or melodic line. In the pieces for free improvisation the performers respond to each other to build the most engaging compositions. Each time you listen to this CD, you hear new things and follow new trails. It’s like getting to know a forest intimately though, in a sense, this is a petrified forest, and those unexpected moments and unpredictable interactions that characterise improvisation are frozen into this disc.

The CD notes indicate the kinds of instructions given to the performers for their performances. For example, for the tuttis, the ensemble might be divided into three sub-sections and there might be signals to each sub-section to start or stop playing, within which each member is to make only one sound and to play at will. The final recording was edited and mixed from many hours of studio performance and the five pieces coalesce into a work that is symphonic in scale if not in form. Though editing and mixing challenge the concept of live improvisation, the result retains its freshness and dynamism.

There are 27 performers listed in the CD’s credits, playing a variety of wind and brass instruments, several basses, accordion, percussion, guzheng, organ, synthesiser and laptop, often at the limits of technique. Though there have been frequent changes of membership, most members have worked together extensively, and they achieve a unique and profound musicianship. Evidently, the final recording was the product of long rehearsals and careful planning, so that the improvisation is mediated by the members’ experience in ensemble as well as by the instructions to the performers. That such large-scale improvisation can work at all is remarkable, and it works marvellously. The CD’s total running time of 44 minutes seems underweight, but more might have resulted in less, given how carefully measured each element seems to be and how well it comes together as an opus. This is an enchanting disc, and a most important development both for The Splinter Orchestra and for music generally.

Chris Reid

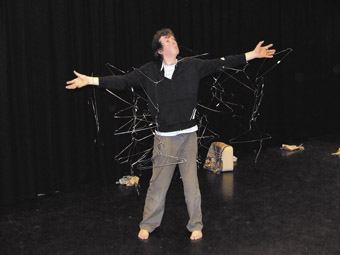

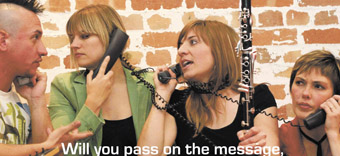

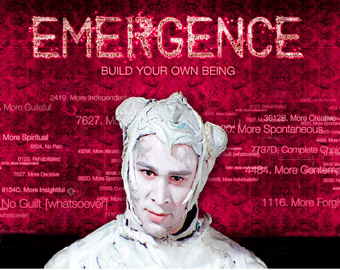

The Fondue Set, Evening Magic 2

photo Irèn Skaarnes

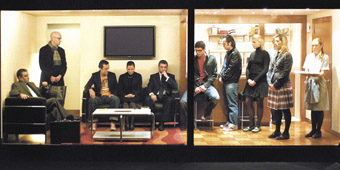

The Fondue Set, Evening Magic 2

THE HUGE PERFORMANCE AREA IS EVENLY DOTTED WITH DANCERS DANCING. THEY ARE PERFORMING BLANCHED VERSIONS OF ‘TYPICAL’ EXERCISE ROUTINES FROM A ‘TYPICAL’ DANCE CLASS. AT FIRST THE OVERLY DECOROUS AND BALLETIC MOVEMENTS SEEM AT ODDS WITH THE VIOLENCE OF THRASHING INDY ROCK. BUT IN CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE, DISJUNCTURE SEAMLESSLY MUTATES INTO SARDONIC COUNTERPOINT. THERE ARE TRAINED AND NOVICE DANCERS. ALL HAVE DETERMINEDLY BLANK FACES. I REGISTER THIS AS THE FIRST OF MANY IN-HOUSE STATEMENTS ON THE STATE OF CONTEMPORARY DANCE.

Like sedated inmates of an asylum the dancers obediently dissolve their formality and sit at tables in front of us—an audience within an audience. The Fondue Set appear, and from this point Evening Magic 2 becomes distinctly episodic. The first spoken/moved/sculptural vignette bursts with self referential text and coded dance references. In a Brechtian gesture we are handed directions to the toilets and emergency exits. The trio that is the Fondue Set form a sculptured image, meant none too subtly to disparage the very flexibility and dancerliness they display.

Despite this drastic plunge in energy levels, from frenzy to fancy, the Fondues maintain the intensity and audience fascination stirred by the opening. They do this through crafted performance skills, pithily witty text and compelling personas. They have been around for a while, extending the tendrils of modern dance into broader recesses of existence like pubs and clubs. These exuberant women, in signature red boots, employ text, mime, slapstick, theatrical production systems and music in equal weight with movement. Or maybe the weight is not so equal.

Clearly, coldly, palpably there came a point in this performance when I just wanted to see these women take their tongues from their cheeks and dance. Not sardonically but indulgently. Not ironically but gorgeously. Not generically but idiosyncratically. For these are gorgeous dancers. But here is raised the ugly head of expectation. I came here tonight knowing these women are trained in dance. I came wanting dance. The program tells me that this work aims at “broad communicative appeal…work that pushes the boundaries of what is considered dance, deals with original movement vocabulary and constantly questions existing theatrical dance forms”. These are big ambitions and I’m not so sure if they were realised on the night.

Involuted and coded messages about dancerliness only make sense to dance aficionados, actually tightening “communicative appeal.” While one audience member called it “anti-dance” I thought it not quite punk enough for this moniker. And traditional dancerliness was evident throughout. It’s in their athletic bodies and flexible extensions, their turned-out hips, in their lengthened muscles and in the very fibre of their being. It also lies in their deep familiarity with the canons of ballet and modern dance. Maybe in trying to be unique, in self consciously attempting to ‘push the boundaries’ they unwittingly place themselves on the same ground as those they would seek distance from. They appear tied to the very forms they revile.

But it was fun. I had a rollicking good time watching a show that ended before I was full. I loved the complexity of the sensorial experience as the guitar ripped into my ears, almost hurting, making me feel old. Production techniques and spatial largesse continually provided multiple and mutating points of interest. Costumes were whimsical, thoughtful and thematic while all the time flattering these fine female forms. I found Emma Saunders’ humorous posturing particularly infectious.

And I know the rest of the audience had a good time too. People ambled out smiling, aping bits of choreography and generally humming with aliveness, leaving the theatre as if it were a pub, as if we had been to a gig. And maybe this is the evidence of broadened “communicative appeal” as the Fondue Set lighten dance and set it free from the confines of serious art and the chin scratching search for meaning.

And Evening Magic 2 is unique. It was distinctive in the use of such a large group of dancers, calling up spectres of early modernist choreographers like Doris Humphries and Rudolph Laban who prized the communality of movement choirs. And yet dancers stood out, individuated against a sameness which ultimately highlighted idiosyncrasy. All were the same, all were different. Some grabbed my attention for lingering moments, but rarely did I lose sight of the organic wholeness of a group who were truly working together. This crowd of dancers congealed a potentially unwieldy space into a moving entity, and did so through an admirable admixture of focus and joyous indulgence. Groupness was never more evident than in the tap dance that wasn’t. A highlight of the night, gimpy hoofers faked a tap routine simply by making it sound right. It was hilarious. Other group vignettes, such as the milk crate choir, lacked vim and conviction and left me asking ‘why.’

Subtending and supporting often frenetic energy was technical proficiency. Evening Magic was thickly and slicky produced; exits and entrances of the large group went off without a hitch or a stumble. Large letters on wheels moved around seamlessly to create pertinent words just in case we didn’t get the message. The musicians appeared and disappeared silently and there was a general confidence with the material that let me know this was the result of dedicated hours of talking, dancing, thinking, planning and dreaming. The Fondue Set work through process. They create substance where there could be a frappe. And the ending was great and sad as we all knew it was over a bit too soon when the final word on wheels was rolled out: ENOUGH.

Fondue Set, Evening Magic 2: Don’t Stop ‘til You Get Enough, Fondue Set, Emma Saunders, Jane Mckernan, Elizabeth Ryan, with The Exiles, Hot Box, members of Decoder Ring, La Huva and Youth Group, design Agatha Gothe-Snape; Performance Space, CarriageWorks, Sydney, Oct 19-20

RealTime issue #82 Dec-Jan 2007 pg. 31

© Pauline Manley; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

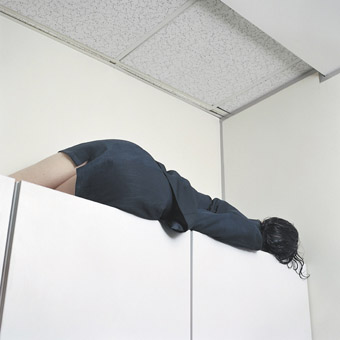

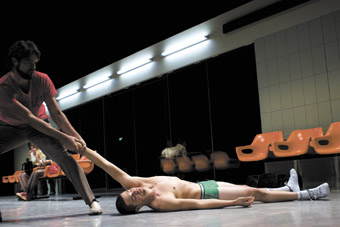

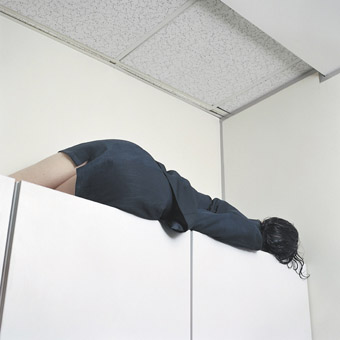

DANCER AISLING DONOVAN RECENTLY DISTINGUISHED HERSELF AS THE LEAD IN AIMEE SMITH’S COURAGEOUSLY HEROIC GALLANTRY, A DEMANDING PIECE WHICH EMPLOYED HARD ARTICULATIONS AND FOLDS OF LIMBS SPRINGING BACK AND FORTH BETWEEN AWKWARD AND ABSURD POSITIONS (RT 78, P33). A NEW WORK FROM DONOVAN FEATURED IN STRUT’S LATEST PROGRAM, DANCE #2, CONTRASTING REVEALINGLY WITH NEW WORKS FROM FLOEUR ALDER AND DEBORAH ROBERSTON.

aisling donovan

Donovan’s choreography, like Smith’s, also employed fierce limb extensions, carving up a corner with her arms and legs. Nevertheless, her Room With A View suggested a goth, if not melodramatic, ambience, unlike the bleak humour and cool detachment of Gallantry. The willowy dancer’s swathes of long, flying hair supported the work’s emotional tenor, Donovan presenting a figure on the verge of emotional self-destruction. Never quite fully dramatic, after a relatively static and introspective opening the dancer’s frenetic pacing and jagged twists were suggestive of the dark night of the soul. The ‘never-quite-there’ of the emotion was part of the work’s appeal, as well as its weakness. Theatrically, Donovan provided little to guide the audience through the emotional journey presented, beyond the heavy-handed music by Tool. This created a strange vacuum at the heart of the work around which Donovan’s muscular, bony poses moved. Overall, Donovan has established that she could dance a telephone book superbly, but the connection between form and affect here was uncertain—she needs to explore this further or throw herself deeper into expressive angst.

floeur alder

The use of a youthful muscular body to suggest emotional states from amidst a whirl of activity appears to ally Donovan with Floeur Alder. Donovan’s choreography and her work with Smith links her to the hard muscularity and performance art allusions of Australian postmodernism (Guerin, Adams, Stewart etc). By contrast, Alder has returned to Modernism’s heritage to produce a wonderful solo which could have come out of the Denishawn School of the 1930s. Using a suitably ‘exoticist’ score in tune with the primitivist allusions of Euro-American Modernism, Alder’s endlessly tensed body, and her expansions in and out of the chest, were executed in concert with clawed hands and spikily bent arms which recalled Wigman’s Hexentantz of 1926. Martha Graham and her predecessors trawled the cultures of those they called “pre-modern” for the primal rhythms of humanity, and Alder was well served by her choice of nuevo flamenco to accompany her own vibrant Expressionism. While Alder avoided the radical arching of the back in favour of a fluid, perching pose, settling into the ground and tearing out of it, every stance and spasm was nevertheless informed by the breath and energy clasped beneath her sternum. Despite the long history of this approach—to say nothing of how many consider it a politically problematic aesthetic—there is no denying Floeur Alder’s command over the material, nor her ability to craft these gestures and affects into a compelling study. Closer to Graham than Wigman, Alder’s dance too (not unlike Donovan’s) teetered on the edge of an emotional explosion. But where Donovan offered a curiously excessive body centred on an absence, Alder’s was a deep pool. Even so, the force beneath these waters was not released. Energy surged in tightly constrained, anguished pathways, imprisoning the body within its own richly affective forces.

deborah robertson et al

Choreographer Deborah Robertson’s task-based, performance art-like work offered something more than Alder’s intensity and Donovan’s emotional displacements. Robertson, Aimee Smith and Laura Boynes exhibited striking physical diversity. Robertson is a highly sensate dancer, proceeding from a quietly measured, inward self-awareness akin to Rosalind Crisp’s. Boynes and Smith are not indifferent to such subtle internal shifts, but their movement—both in this piece and in other projects—comes initially from outside the body, from form, shape, or political ideas. This dissonance suited the piece in that the often deliberately pedestrian movement revolved around a failure to fully connect; on rejection and ignoring one’s fellow. Smith was a lone rejected figure on a chair at the front while Boyne’s rapid move from her chair or away from Smith gave her movement a nasty edge. Robertson by contrast seemed a gentle focal point shifting throughout the space, but her mild articulations and reassuring self-awareness nevertheless failed to resolve this drama of dislocated individuals. Sounds of cars and city noises added a further layer to the sense of urban alienation. However, a work about the disarticulation of society risks drifting apart. Nevertheless, Robertson disarmingly sustained a sense of both accusation and forgiveness, of atomisation and socialisation in this simple work, providing a wonderful richness to its otherwise spartan form—an affective strategy far removed from the works by Alder and Donovan.

Strut Dance, Dance #2 2007, artistic director, curator Sue Peacock; Room With A View, choreographer, performer Aisling Donovan; Confessional, choreographer Deborah Robertson, performers Robertson, Aimee Smith, Laura Boynes; Seven choreographer, performer Floeur Alder; plus works by Keira Mason-Hill, Simon Green and Gerard Veltre, Bianca Martin, Lena John, Sally Blatchford and Shannon Riggs, Sarah Neville, and Valli Batchelor; King Street Arts Centre, Perth Oct 18-21

RealTime issue #82 Dec-Jan 2007 pg. 30

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

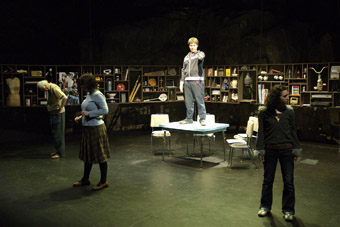

Weave Movement Theatre, Capsule

CAPSULE ENGAGES THE NOTION OF FLIGHT AT MANY LEVELS—FROM ITS MOST LITERAL INCARNATION OF AEROPLANE TRAVEL, TO THE ANALOGUE OF THE JOURNEY, THROUGH TO THE MYTHICAL FIGURE OF ICARUS.

Each of these incarnations signifies a certain vulnerability related to Icarus’ meltdown. The variety of dancers who make up the mixed ability Weave Movement Theatre embody our mortality by opening up our sense of who we might be. If dancing bodies tend to reinforce norms of beauty and facility, Janice Florence’s choreography engages a wider palette of human capacity. The result is a greater variety in the timbre of movement. What is it to watch action which must discover itself in the doing, rather than presuppose control? Nietzsche argues that there is no doer behind the deed, simply the deed itself. Here, the deed casts light on our presumptions about the doer. Is this to fly too close to the sun? Not at all. The use of irony, humour and parody alongside the poetic made Capsule much bigger and more resilient than us all.

Weave Movement Theatre, Capsule, director Janice Florence, choreographic advisor Michelle Heaven, performers Trevor Dunn, Janice Florence, Tom Hope, Sarah Mainwaring, Kate Middleweek, Noelle Rees-Hatton, Anthony Riddell, Ariel Verona; Dancehouse, Melbourne, Sept 13-15

RealTime issue #82 Dec-Jan 2007 pg. 31

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Moira Finucane, Burlesque Macabre, The Queen of Hearts,

photo Heidrun Löhr

Moira Finucane, Burlesque Macabre, The Queen of Hearts,

2007 DRAWS TO A CLOSE ON AN EXTRAORDINARILY BUSY YEAR OF INTERNATIONAL TOURING FOR AUSTRALIAN CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE. ASIDE FROM THE MAJOR COMPANIES RESOURCED TO TRAVEL (BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE, SYDNEY DANCE COMPANY ETC) SMALLER ORGANISATIONS AND INDIVIDUALS HAVE BEEN FINDING SUCCESS OVERSEAS. BACK TO BACK THEATRE, BRANCH NEBULA, ADT, URBAN THEATRE PROJECTS, DANCE NORTH, CHUNKY MOVE, LUCY GUERIN INC, CIRCA, ACROBAT, ROSIE DENNIS, CLARE DYSON, MOIRA FINUCANE, MEOW MEOW, MEN OF STEEL, TOM TOM CLUB…THE LIST GOES ON. WHAT IS BEHIND THIS UPSWING IN ACTIVITY? IS IT FASHION, CHANCE OR THE RESULT OF A SLOW ACCUMULATION OF SHEER HARD WORK? WHAT ARE THE MOTIVATIONS AND MACHINATIONS OF AUSTRALIAN ARTISTS ON THE INTERNATIONAL SCENE AND THOSE WHO SUPPORT THEM?

I talked to the few producers promoting Australian performing artists internationally and, as you’ll read in the next edition of RealTime, to the companies themselves. Wendy Blacklock at Performing Lines has been in the business for over 25 years, first taking an Australian Indigenous theatre company overseas in 1982. Marguerite Pepper has a similar history and both refer to Justin McDonnell, now in the US, as another pioneer of their generation. Certain funders have been around long enough to follow the work of these producers and their artists, including Amanda Browne, who has over a decade of experience as manager of the International program of Arts Victoria.

motivation

All these individuals agree on why artists choose to tour. There is the fundamental drive to keep working, to fill the calendar and preserve livelihoods. There is the sense of relevance and connection to a world of diverse cultural contexts. There is the chance to meet other artists and absorb new ideas. There is, sometimes, a financial benefit to be gained. With luck, new presenters with touring connections see your work. Occasionally there are even commissions and collaborations. Always there is the increased cachet and resultant opportunities at home that follow success overseas.

Nobody can be sure whether the increase in touring of 2007 is an all-time high. There is no consolidated data, yet producers and funding bodies confirm that activity has been building over the last decade and looks set to continue. All recognise that success breeds success. A large part of international touring is confidence. Any sense of disenfranchisement, because of Australia’s great distance from other markets, is quickly dispelled by a sell-out season at a major arts festival. The producers elaborated how much of their role is about coaching and encouraging artists, as much as it is about tour booking and negotiations.

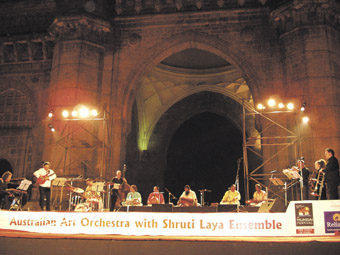

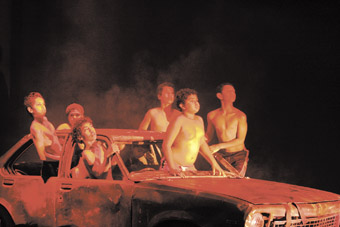

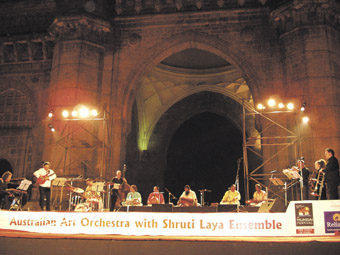

Australian Art Orchestra Sruthi Laya Ensemble, Into the Fire, Gateway of India Mumbai

global engagement, global issues

All agreed that Australian contemporary performance is currently expressing an unprecedented self-confidence, particularly in Indigenous and cross-cultural idioms. Mature performers such as didjeridu player Mark Atkins are leading new generations of artists into rich cultural dialogue. Amongst cross-cultural productions touring in 2007, Marrugeku’s Burning Daylight featured in Zurich’s Theaterspektakel festival and Urban Theatre Project’s Back Home travelled to Toronto’s Harbourfront Centre. And the rest of the world is particularly interested in this distinctive Australian discourse. Marguerite Pepper noted that the Pacific Rim focus of the 2007 Australian International Music Market in Brisbane was extraordinarly well received, by Europeans in particular. She cites the young Brisbane-based didjeridu player, Tjupurru, as a runaway success. Pepper talks of a coming of age of the sector but also of a more enlightened support structure which allows for risks to be taken with less proven artists or projects of scale, unconventional settings and more complex contexts.

Contributing to a global discourse is a sign of Australia’s cultural maturity. Benefiting from a cyclical change of taste and fashion is a less predictable but equally energetic connection. Australian dance, physical theatre and circus is the choice of European presenters jaded by their own artists’ current predilection for conceptual anti-theatre. Just as Meryl Tankard’s ADT, Legs on the Wall, Stalker and Circus Oz were feted in the early 90s, Splinter Group, Circa and Garry Stewart’s ADT now break into markets where virtuosity is thin on the ground. The hybridity of Australian work and its ease in cutting across forms, media and ethnicity has been praised by presenters such as Maria Magdalena Schwaegermann who favoured Australian work in her Theaterspektakel festivals in Zurich.

support mechanisms

While fashions have always come and gone, the difference now is that Australian artists are resourced to take advantage of them and are aware of and involved in the international arts market in ways impossible to imagine a mere decade ago. Web-based communication is making promotion easier as are cheaper travel costs. Blacklock spoke vividly about her trials raising a seemingly impossibly $100K to tour to Expo86 in Vancouver. In those days there were no specific programs to which companies could apply for travel support and this alone created an enormous hurdle. Now, as all agree, the range of sources of support encourages companies to invest in international presentation as a viable aspect of their business.

Producers and funders alike found it difficult to say if funding programs drive activity or vice versa. There was unanimity that Australian artists are professionalising apace and that many have formed coherent strategies for international activities. While some have done this in response to specific new funds designated for business development, such as Victoria’s SCOOP program, or the Australia Council Theatre Board’s International Market Development Strategy for Theatre for Young People, others have siphoned core funding into international activity as the most sustainable aspect of their business. Circa and Strut & Fret Production House (both companies are Brisbane-based) are examples of this entrepreneurial approach. Acrobat, who invested heavily in their career ever since their early borrowed bus and starvation tours, did it the hard way but are finally making a reasonable living not least in the UK and Europe where they are enormously popular.

the big picture

Sandra Bender, the new Director of Market Development at The Australia Council, is a Canadian who comes to the current situation with a perceptive take upon the successes and limitations of previous programs designed to promote Australian contemporary culture internationally. She recognises the intention of programs such as Undergrowth in the UK and the multi-year investment in Berlin as serious attempts by the Council to engage in reciprocity and exchange. She also realises however that such high profile, focused activity can be supplemented by subtler, smaller projects with longer lifespans. The Australia Council’s investment in arts markets is likely to diminish, and whilst the producers cited APAM, CINARS and APAP as the source of many of their most productive international relationships, they all agreed that nothing much materialised from the conversations engaged in there for years, and sometimes not at all. Bender plans to resource companies to tailor-make their international networking and relationships more strategic, aiming for future collaborations, co-productions and commissions. This approach has borne fruit for Arts Victoria, which has offered specific programs for international activity since 1995. Encouraging Victorian companies to make their own explorations, while still taking advantage of national initiatives such as The Barbican’s Ozmosis project or the Pittsburg Cultural Trust’s Australia Festival in 2007 makes the best of both worlds.

As the sources of support for touring proliferate the volume of activity naturally increases. The federal government’s recent announcement of the Australia on the World Stage program, to be implemented by AICC (the Australia International Cultural Council, a consultative group chaired by the Minister for Foreign Affairs and composed of leaders from government, the arts and business) is a promising new source of support, the details of which are not yet available. While this program will continue the focus upon key markets shared by the Department of Foreign Affiars and Trade (DFAT) and the Australia Council, the producers all noted that new markets are opening up to Australian artists. As the populations of Asian countries such as South Korea and China become more prosperous and more attuned to their role as global citizens, the doors to their cultural institutions are opening. Through proximity, something of a track record (at least compared with European artists) and the out-and-out encouragement by funders, Australian artists are making headway in Japan, Korea, Singapore and China. Artists in Western Australia recognise that performances in Asia are often less expensive to organise than a national tour.

pleasures & pitfalls

While there is a unanimous and hearty engagement with international touring among artists, producers and funders, it’s clear that there is an equal distribution of pleasures and pitfalls along the path to international success. Tales of lost freight, visa shenanigans, critics without context and language issues are balanced with accounts of budgets surpassed, standing ovations, return invitations and five star reviews. Most companies and artists report a fine balance between the cost and gain of their international activity and iterate the comments of funders and producers, confirming a lively interest and investment in this area and optimistic, if cautious views of the international future for Australian contemporary performing arts. In RealTime 83 I’ll report on how individual artists and companies view the value of their international touring.

RealTime issue #82 Dec-Jan 2007 pg. 32

© Sophie Travers; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

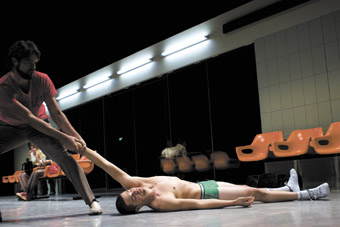

Joseph Del Re, Brendan Rock, Dogfall

photo Nic Mollison

Joseph Del Re, Brendan Rock, Dogfall

THE ‘THEATRE OF WAR’ IS A CURIOUS PHRASE WITH AN IRONIC RING. IT CONJURES AN IMAGE OF GENERALS, COMFORTABLY AT WAR, GATHERED AROUND A MAP ON A TABLE IN THE OFFICERS’ TENT, ARRAYING THEIR FORCES, THEIR PAWNS, IN WHAT SEEMS AN IMAGINARY GAME, A REPRESENTATIONAL FRAME, DIVORCED FROM THE ACTUALITY OF THOSE FIGHTING THE WAR.

That great 19th century theatrical shift—from actor-manager on the stage to theatre director in the auditorium—had an antecedent in military practice. By the time Carl von Clauswitz coined the phrase in his book On War (1832), the generals had long ceased leading armies into battle. Like the leading men of the theatre, they had retreated from the main action on stage. Modern war, like modern theatre, was to be directed from a distance.

These days wars fill our screens with their spectacle. Their ‘shock and awe’ imitates the animated splatter of computer games while, in the intimacy of our theatre, playwrights, actors and directors conduct laboratory experiments in the trauma psychology of men at war. Caleb Lewis’s Dogfall is a well-pedigreed play, declared ‘wonderful’ by American playwright Edward Albee, with whom the Australian Lewis undertook a two-week workshop on another of his plays. The wonder, I think, is Lewis’s imaginative insight into war and what can make us care.

The scenario is a war-time convention. Will (Brendan Rock) and Jack (Joseph Del Re) are soldiers, mates in the adversity of war. Life in the trenches means living it rough and doing it tough, while the battle rages and rumbles like thunder off-stage. They are disturbed by a third. A boy soldier, Alousha (Martin Hissey), becomes the unwitting target for their rough love, their piss-anguished fear, their gut-empty catharsis.

Director Justin McGuinness commands the energies of emotional realism from the actors. They sweat with fear and eat tinned food for real. They smoke on stage and drink and swear like troopers. They piss and shit copiously off stage to dysenteric sound effect. With the synaesthesia of intimate theatre, the production’s signifiers mingle in my nostrils: whatever the conflict, war stinks.

Lewis arrays the wars of past and present like tin cans in a rough-shot shooting gallery. While the characters conform to the continuities of drama, the theatre of their war changes with each scene—the Somme, Edessa, Guernica, Nanking, Northern Ireland, London, Treblinka, Stalingrad, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Phnom Penh, Israel, Mogadishu, Kuwait, Home (as comic interlude), Bosnia, Rwanda, New York, Guantanamo Bay—till we end up bogged down in mud, mired in oil and blood with the dying and the dead.

Yet sitting in the audience, it’s for neither Will, Jack nor Alousha that I care. Their suffering is tarnished by the complicity of their guilt. In this theatre of war, there are no conscientious objectors, no women and children to be spared. I am desensitised to all but dogs, that fall mysteriously from the sky on the screens behind. I see an Alsatian falling, a Saint Bernard, a Dalmation. A spotty mongrel falls. I yelp in pain. “It’s just meat”, says Will. But not to me. I care.

TheimaGen, Dogfall, writer Caleb Lewis, director Justin McGuinness, performers Brendan Rock, Joseph Del Re, Martin Hissey, design TheimaGen, Tsubi Du, sound Peter Nielsen, lighting Nic Mollison; Bakehouse Theatre, Adelaide, Nov 2-17

RealTime issue #82 Dec-Jan 2007 pg. 33

© Jonathan Bollen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Roza Ilgen, In My Shoes

photo The Bellasis Bros

Roza Ilgen, In My Shoes

IN A RANGE OF EVENTS IN GALLERIES AND MUSEUMS AND CULTURAL CENTRES THROUGHOUT THE UK, 2007 IS BEING COMMEMORATED AS THE 200 YEAR ANNIVERSARY OF THE ABOLITION OF THE SLAVE TRADE. IN BRISTOL, ARNOLFINI’S RESPONSE TO THE ANNIVERSARY IS DISCURSIVE, RATHER THAN DIRECT, AN EXAMINATION OF THE WEST’S IMPLICATION IN PAST AND CONTEMPORARY PATTERNS OF GLOBAL EXPLOITATION. THE RESULT, PORT CITY, IS A MAJOR CROSS-ARTFORM PROJECT EXPLORING ISSUES OF MIGRATION, TRADE AND CONTEMPORARY SLAVERY, CONCERNED WITH THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PORT “AS GATEWAY TO A WIDER WORLD…A SYMBOLIC SITE OF CULTURAL EXCHANGE.”

During the Port City Live Art Weekender at Arnolfini, I felt I was truly being engaged as a global citizen, by other global citizens, the artists: an unruly bunch of compromised, ambivalent, intercultural border-crossers. Much of the work was about being in one place with roots in another; translating/making analogies between one situation and another.

brennan, speakman

Both Tim Brennan and Duncan Speakman invoked a sense of moving through the English landscape, crossing long lines of traffic or transport or time, connecting urban to rural, historical to immediate. Brennan, in Performing Northumbria: Empire, mediated his story through deliberately informal, low technology journal keeping and conversation, reading aloud from William Hutton’s early 19th century account of walking Hadrian’s Wall. Assisted by rather gauchely literal props—an actor dressed as a Roman legionary, a large stuffed eagle, a child’s umbrella with mouse ears—he had audience members volunteering for various story-assisting duties, including several people reading extracts from Hutton’s journal in a chorus of overlapping voices.

Speakman, using high-tech recording and mixing in For Every Step You Take, I Take A Thousand, constructed a sound picture of a four-day walk taken through countryside fields into Bristol. Recordings made during that journey—Eastern European farm workers, drinkers in a pub, birds in hedges, an aeroplane passing, traffic—could be listened to either through the studio speakers or, more intensely, through headphones. Speakman mixed and processed the sound live for the audience in a tightly-controlled, evocative work.

curious

In (Be)longing, Curious made play for us with their culturally-determined, authentically inauthentic selves—middle-class English intelligentsia and dislocated Texan—in a delicate, funny piece about longing and identity. Under a glowing neon road sign they addressed the audience, wryly performing failure to be a shit-hot guitarist, or failure to evolve into a higher being through yoga; gently demonstrated the ordinariness of disappointed aspirations. Also showing was a short video piece bu curious in which a group of young women, teenage asylum seekers, were asked about their wishes, hopes and fears. All are likely to be deported once they reach the age of 18, fracturing any sort of continuity in their lives and educations. The link between video and performance was tenuous, but there was an attempt to find common ground between very different women’s lives, and to use the empathy thus poetically engendered as the basis of political awareness.

patel and bradley

In Morris Dancing, a piece about cultural exchange and mirroring, Hetain Patel and Alex Bradley posed adjacent to each other. The skin of each was decorated with henna in patterns derived from William Morris wallpaper, a deliberately hybridised system of signs highlighting a specific moment in their two countries’ long history together, echoing down from the British Raj into the present. Spotlit but separate in a dark space edged by the boundary marking of a strip of wallpaper, each fell into their own rhythm and style of display, relaxation and camouflage, sometimes resting, sometimes seated, sometimes laid against the wallpaper as if to match the pattern on it.

jiva pathipan

Jiva Parthipan’s Necessary Journey related the snafu details of an attempted trip to take up an artist’s residency. Seated at a desk, Parthipan (an Asian artist of Sri Lankan heritage) read out official letters he had received from embassies, from the Home Office, from the Arts Council, accumulating the narrative of a completely thwarted journey to Mexico and the US. He would periodically interrupt himself to step to one side of the desk, take some of his clothes off and transform, through mannerisms, into first a dog, then a monkey, and finally, nakedly, into plain humanity, explicitly glossed in the program notes as ‘godhead’, the divine.

That evening, from the same artist, we had a treat in the shape of cabaret from the Al-Quaeda State Ballet, supported by free rum for the audience. It would have been alarming if it hadn’t been so impish—there was jumping and gyrating and a sort of Ninja can-can—clothes came off at some stage—there were black tights involved but those could have been on his head…

harminder singh judge

A godlike man, his bearded face and head painted blue, delivered his urgent, incomprehensible Live Sermon to us, the audience in the dark, from a speaker placed in his mouth. Dressed in a heavy silk skirt, Harminder Singh Judge (whose work is rooted in Hindu and Sikh religion) stood in a wide shallow dish of luminous-looking milk—an effigy, a mouthpiece, a resonating instrument, an avatar. Afterwards an almost invisible trace of his presence was left in the milk, a cloudy blue shadow, an indecipherable portent, a stain from the hem of his skirt.

qasim riza shaheen

In the Light Studio for Qasim Riza Shaheen’s Queer Courtesan, I’m instructed to select one of a bunch of old vinyl 45s scattered by a portable record player, one of those 60’s affairs that folds up into a little briefcase. I discard an old pop song and a couple of discs with Urdu titles in Roman script to choose a polka. There’s a booth to the side, fairground colours, a plastic strip curtain in the entrance. I’m ushered inside. I sit down.

I can see a shadowed human figure behind a transparent sheet of plexiglass just in front of me. The light changes and I’m in the dark, the figure spotlit. Dressed in a heavily embroidered silk sari, fanfared by the music, a gaunt, graceful, heavily made up man with a martyred, ecstatic expression begins to primp and preen and touch himself up. It’s suggestive, but tasteful.

I’m just relaxing into it when the light goes off, the music stops, that’s it, that’s my lot. No more technicolor, no more polka, no more tease. It was so well-timed for maximum frustration, I was sure he’d been looking at me (the program notes explain he only sees his own reflection). If I’d been a punter I’d be angrily banging on the glass—but I’d also pay up for another five minutes. Seduction, I guess, has to be about something you can’t get: a satisfied client has no further reason to pay. However I remain unenlightened about the relationship, mentioned in the program notes, between dance and prostitution.

Queer Courtesan manifests too as a video installation in the Dark Gallery with six telly-sized video screens across a wall. In each the artist presents a cameo of a different individual: he impersonates, or represents, one of the Khusra, transgendered sex workers of Lahore he worked with over a period of two years. He wears that person’s clothes (elegant female clothing) against a backdrop of their habitat—their room, or their street corner. One of the rooms is white and shiny, full of electrical equipment and speakers. Another screen shows a couch on the street beside a smoking fire and a tyre swinging from a rope. On another screen the artist sits in an armchair; on another he dances. His costumes are ornate and appear expensive. Looking straight at the camera he strikes attitudes, displays cleavage, plays with a scarf, tears his hair.

A studied invocation of The Virtuous Woman haunts each of these drag acts, trailing implications of forbearance and tenderness and of sacrifices made on the altar of love; meanwhile the tease is tremendously aggressive. It lures you in, so to speak, only to slam the door in your face. One of the cameos actually does this: the artist comes closer and closer to the camera until his face fills the frame; he seems to be just on the verge of being available and, then, bang! The door of the booth slams shut, with you, the client, on the outside, in darkness.

Shaheen impersonates Khusra for the gallery in a way that could not be done without their justified cooperation and trust. The artist places himself as a conduit between the community and the outside world: he does it with beauty and one hell of an attitude. Histrionic and very alluring, at the heart of the work one can discern contempt for the client combined with a yearning for love (maybe clients are to be punished for not being that mythical creature, ‘a real man’). The performances ooze with a defiant sense of entitlement which is linked to the visual portrayal of an ideal of exquisite suffering; and the viewer is uncomfortably cast in the role of john, with all the complicity and self-deception that entails.

Roza Ilgen, In My Shoes

photo The Bellasis Bros

Roza Ilgen, In My Shoes

roza ilgen

The foyer at Arnolfini is open all the way up the stairwell to the top floor, all clean white angles around the brushed steel lift-column. A young woman sets up camp here. The niche she creates is untidy, like a market stall. She sits on a low stool, with a dish of viscous white liquid to her left. Two chairs face her, and on her right are big metal basins heaped with dark fuzzy patties of what looks like felt. It’s a terribly organic colonisation of that clean white space.

She’s an attractive, personable presence, facing onlookers with friendly engagement. She could be…Southern European? Latina? South Asian? Her dress contains a nod towards the Orient in that she’s wearing calf-length black jersey shalwar; these look, however, as if they could have come from Gap. In other words, this woman in her untidy territory looks completely cosmopolitan.

On enquiring what she’s doing, you could find yourself seated in front of her with one foot on a low stool placed in a basin of soapy water, while she smears suds over a disc of human hair placed round your foot to make a felt slipper. Similar slippers line the walls of the foyer, all sizes from toddler to galumphing size 12, and in all colours. Of hair, that is, which means in fact brindled. It seems the colour of human hair in Europe, while not absolutely mousy, averages out to brown. When I speculated that in a different country this base colour would be different my assumptions about Scandinavians were quickly corrected! Bin bags full of hair had been collected from 20 different hairdressers in the city and the artist had prepared a supply of felted discs ready for the installation.

Looking at the circles of hair packed into the bowls, you begin to conjure up presences. That person, a rarity, has black hair, and had a complete change of style judging from the quantity cut off; that must be a child with fine blond curls; that person just had a trim; that one is going grey, and oh vivid, there’s a redhead! The spectre of these invisible donors is urgent, and you’d imagine that having your foot swaddled in their off-cuts would be intrusively intimate, but it isn’t. It’s workaday, mundane, like getting a manicure or being measured for a bra. Distancing kicks in, and the process feels like just another variant of the service industry.

Roza Ilgen wrapped my foot in cling film, shaped a circle of human felt around my heel with warm soapy water, moulding more patches onto it to make up a slip-on bootie. She really got into it, kneading and squeezing gently, pouring on more soapy water, covering the toes, building up the throat. When she was satisfied she tackled it with a hair dryer, felting the material more. Then she eased the boot off. It was still damp but held it’s shape, looking sturdy and, already, well-used.

As a black woman I bring such a heavy set of interpretations to the symbolism of hair, I was in danger of missing what was happening here. I wondered about the rows of empty shoes bounding the space, facing the wall, the possible ethnic presences or absences indicated by hair type and colour. I missed the analogy with shoes removed at the door of the mosque—in this case facing a blank wall rather than pointing towards a place of worship.

I nearly missed this beautiful, pragmatic, deeply subversive gesture for what it was: a stubborn exercise in de-mystification and defiance. Ilgren performs a personal service for an audience, engaging them, drawing them in. Meaning streams from her presence in the middle of the activity: she is a Kurdish artist, one of the people without a country, just for now treating the gallery like a cottage industry squat. She takes a material attribute of humans that is, within Islam, culturally loaded and prescribed in a specifically gendered way: with this she makes public, workmanlike, hardy artefacts. Artefacts that are meant to be trodden on. Artefacts that somehow infect the conceptually clean gallery space with some of their own physical fuzziness.

Port City Live Art Weekender, Arnoflini, Bristol, UK, Sept 28-30

RealTime issue #82 Dec-Jan 2007 pg. 34

© Osunwunmi ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

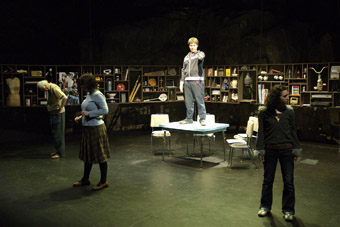

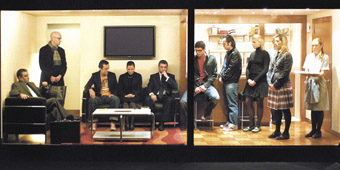

l-r – Ron Haddrick, Sara Cooper, Jonathan auf der Heide, Jemma Gates, Beyond the Neck

photo Tony McKendrick

l-r – Ron Haddrick, Sara Cooper, Jonathan auf der Heide, Jemma Gates, Beyond the Neck

TOM HOLLOWAY WAS 17 YEARS OLD AND WORKING IN A PIZZA SHOP IN HOBART WHEN THE TRAGEDY AT PORT ARTHUR UNFOLDED IN 1996. HIS PLAY, BEYOND THE NECK, A STORY PERFORMED 10 YEARS LATER, IS HIS POWERFUL RESPONSE TO THE EVENTS OF THAT DAY.

An arc of shelving containing family memorabilia wraps around the performance space. Isolated in compartments these artifacts include a transistor, phone radio, wireless, pair of binoculars, traffic cone, model ship, horseshoe, red safety helmet, photo developer, dartboard, pair of red shoes and a model of a colourful Montgolfier balloon. Most of these embody a nostalgia for childhood and the shared times of family life. Because we are alert to the symbolic significance of many of the items, this miscellany of memory also evokes a sense of menace and foreboding.

Four strangers are seated at a table. They introduce themselves as a boy (Jonathan auf de Heide), teenage girl (Jemma Gates), young mother (Sara Cooper) and a tour guide (Ron Haddrick). They offer fragments of their story interspersed with interruption and disjuncture. Each character strategically draws on the device of a closing imperative such as “No!”, “Stop!” and “What!” These intercessions deflect a specific or difficult strand of thought that threatens to summon terror, blame or dread.

It’s Sunday. Making their separate journeys by car or coach are the boy, the teenage girl and the young mother. Inevitably someone is whingeing. The teenage girl is cramped in the back of a car with her knees jammed under her chin. She resents her mother’s intimacy with the driver, her father’s best friend. The boy is hyper-excited because his friend Michael is traveling with him—or is he? The young mother is part of a mystery bus tour with a blue-rinse mob. She turns toward the rear of the bus to ensure that her husband David and daughter Molly are present—or are they?

It is this indeterminacy of past, present and future that contributes to an inexorable build of tension. Our knowing and imaginings are already filling in the spaces. Through an interweaving of narrative and back-story, our apprehensions hover about the temporal uncertainty and the indeterminate fate of these Sunday travellers.

The Neck is a narrow strip of land a few hundred metres wide, 83 kilometres from Hobart. To cross The Neck is to be inexorably drawn to the former penal settlement of Port Arthur. This prison was modelled on Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon which functioned as a round-the-clock surveillance machine where each prisoner was left alone in the dark without sound or name, inevitably raving into madness. We are similarly seated in the darkness of the auditorium while observing each character’s terror, grief and compassion unfold.

Waiting at Tassie’s top tourist attraction to meet his next tour group and unleash his “old fart’s bad jokes” is the tour guide (Ron Haddrick). When he welcomes us to the Visitors’ Centre our indeterminate journey begins. The impact of that day on each of the characters is gradually revealed. Again we are reminded of the cruelty of sudden absence: the boy hears his friend Michael urging him to act, the teenage girl grieves the loss of her father, the young mother recalls her terror when she is locked in the darkness of a solitary cell. Ten years later the tour guide is still fending off intrusive questions and angrily refers to the “bullshit” of ‘closure.’ “Were you there?”, the teenage girl asks the tour guide and an autumn chill slaps our necks.

Beyond the Neck was one of five plays out of 400 entries to be chosen for presentation as part of the Royal Court Theatre’s International Young Playwrights’ Festival in London. Holloway structures his play so that through fragments and overlays of story, through the fluctuation of presence and absence, four strangers find connection, solace and possible redemption.

The events at Port Arthur reverberated around the world. To echo the words carved in stone at the memorial site: “…cherish life for the sake of those who died. Cherish compassion for those who gave aid. Cherish peace for the sake of those in pain.” Holloway’s tautly crafted work offers a theatre of renewal for and of our time.

Beyond the Neck, writer Tom Holloway, director Iain Sinclair, performers Jonathon auf der Heide, Sara Cooper, Jemma Gates, Ron Haddrick, design Jamie Clennett, lighting design Daniel Zika, composer, sound designer Steve Toulmin, An Argy Bargy Production presented by Tasmania Performs; Peacock Theatre, Hobart, Sept 12-15

RealTime issue #82 Dec-Jan 2007 pg. 35

© Sue Moss; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Hotel Obsino

I MUST CONFESS TO HAVING SPENT A SOLITARY NIGHT IN THE SIR CHARLES HOTHAM HOTEL, SPENCER STREET MELBOURNE. AS THE INSPIRATION BEHIND ADAM BROINOWSKI’S PLAY HOTEL OBSINO, I ALMOST FEEL AT HOME AMONG THE STICK BOOKS AND SYRINGES LURKING WITHIN THE FLOTSAM ON LA MAMA’S FLOOR. IN A BOOTH BENEATH THE STAIRCASE SITS A SO DESCRIBED CURRY-MUNCHING CARETAKER. CORNERED BY BOUTS OF CROSSWORD CONTRIVED WISDOM, BUDDHIST RHETORIC, OUTBREAKS OF RESIDENTIAL MADNESS AND INCOMING INDUCTEES, HE IS BOTH MANAGER AND MADMAN. ENTER NOAH, ON THE RUN FROM EVERYONE, INCLUDING HIMSELF.

Searching for solace in this ark of decay, Noah is the ballast Hotel Obsino requires. Well, somebody’s gotta ‘keep it real’ amidst death, drugs, life sentences in rooms that resemble Sadean dungeons, madness, despair and the Devil’s delight circulating within a purgatorial twilight…In doing so, Noah discovers that he also is an accomplice of the criminally insane.

A parade of dying souls descends the staircase, beginning with a young woman wearing a negligee and carrying a bucket. Miss Jones squats and piddles, then pats her pubis with a sheet of toilet paper. Singing “It’s a fine line between pleasure and pain”, she exits stage left. Obsino is a man’s world, and I cannot help but wonder what the women in the audience are feeling… Excluded perhaps, like the Aboriginal, Noodles, who after unleashing a moment of squawking madness, is only ever seen wandering alone through corridors, sitting invisible, listening to whitefella attempts at camaraderie, or crossing off the days in chalk on a wall in what might be his room, but could also be a memory of incarceration at Grafton Prison. Bigotry never takes a holiday, and nor do the relentless days and nights filtering through cracks in walls from an outside world that is only ever referred to in paranoid terms. A tourist with a typewriter, Noah will eventually jump this Ship of Fools. As for the other residents, they’re down here for the the term of their natural lives.

Dave has a swastika tattooed on his neck and may have been baton raped while doing three with a five. Fabio dreams of having sex while his cock is wrapped in a nail studded towel. Gold is a jive talkin’ junkie hybrid of the Wogboy and the Universal Soldier. Felix and Doug are curious creatures. The former is a sentimental European who recreates his mother in his room; the latter, a religious nut primed with a fear of the Devil that is explosive when unleashed upon Noah. As confidante, Noah commiserates, and is complicit in the anti-life of each fruitloop. But all are united by survival on the edge of a metropolis that itself may be a manifestation of insanity. Common to all these characters is a fear of religious damnation. In this sense, Hotel Obsino is an examination of people trapped in purgatory. Driven mad by an inability to relinquish a belief in the Divine, each slowly self-immolates.

Having myself spent seven years living in a notorious St. Kilda dive, I can vouch for the authenticity of Hotel Obsino’s characters.

Hotel Obsino, writer, director Adam Broinowski, performers Le Roy Parsons, Eric Mitsak, Tahir Cambis, Tom Davies, Brendan Bacon, Melanie Douglas, Craig Hedger, Dylan Lloyd, Polish Larsen, Greg Ulfan; La Mama, Melbourne, Sept 12-30

RealTime issue #82 Dec-Jan 2007 pg. 35

© Tony Reck; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

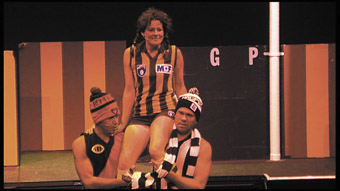

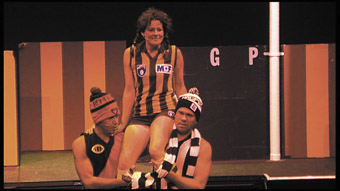

Raymond Wright, Tanya Langdon, Donald Mallard, Barracking

photo David Nixon

Raymond Wright, Tanya Langdon, Donald Mallard, Barracking

AWARENESS OF THE HUGE CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF AUSTRALIAN RULES FOOTBALL FOR INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN THE NORTHERN TERRITORY HAS ONLY RECENTLY BEGUN TO DAWN ON WHITE URBAN AUSTRALIANS. THIS HAS BEEN DESPITE THE FAME OF INDIVIDUAL ABORIGINAL PLAYERS FROM THE REGION WHO HAVE SUBSTANTIALLY LIFTED THE GAME OF LEAGUE TEAMS IN THE SOUTH. IN THE WAKE OF THEIR SUCCESS WITH MICHAEL WATTS’ NOT LIKE BECKETT (RT81, P32), ALICE SPRINGS’ RED DUST THEATRE HAS NURTURED ANOTHER FASCINATING PLAY, THIS TIME ABOUT FOOTBALL, AND TOURED IT THROUGH THE TERRITORY.

Katherine-based writer Toni Tapp Coutts, who saw the play in her home town, describes its tone as “although heart-wrenchingly honest, essentially comic.” She writes,”Barracking does not take the easy road. You squirm in your seat as Cuz tells the ambitious young footballer Brownie in no uncertain terms what it can be like to be a blackfella in the city. Coutts thinks that “the focus on the shared faith of football, almost a religion for many Australians, allows the play to confront issues of racism, love, family pressure, community demands and the internal struggle of a young man who wants to be a great footballer in the city, playing for his beloved Hawks, but doesn’t want to let down his home team, family and friends.”

Written by Jane Leonard (a long-time writer who moved to Alice Springs nine years ago) and Steve Gumerungi Hodder (a Mornington Island man who has lived much of his life in the Alice as an actor and broadcaster), Barracking is, on the page, a brisk and engaging account of a developing romance between Brownie and a Melbourne writer, Goldie, who has moved to Alice Springs after the death of her father. A series of brief encounters where Goldie is sometimes the only white person at a community match bring the two closer together, a shared passion for the Melbourne-based team Hawthorn providing common ground. Brownie has the talent to play for the Hawks and yearns for the accompanying luxuries in contrast to the poverty and despair that surround him. His cousin, Cuz, has lived the life of the footballer in the city, a venture undone by white racism and his own stubborness. Brownie is undeterred, he already knows racism. However, when the ‘draft’, the search by white coaches for black talent, ensues and Brownie is told by his coach to give up his community team coaching, his love for Goldie and a vision of a Northern Territory team taking on the south creates a new future for him and his community.

Threaded through this tale are scenes, often comic, of Goldie’s evolution as football fan (and writer, as she mimics sports broadcasters) from childhood to adolescence and university, in each period having to restrain her passion for the Hawks in the interest of not upsetting male domination of footy fandom. The exception is her beloved father with whose ghost she affectingly chats to in a cemetery before taking off for Alice Springs, saddened by her loss and deploring the corporatisation of the AFL. In the Alice she finds both love and a community-based football that reminds her of better times.

Barracking is often overtly didactic (Goldie’s Armenian heritage, for example, is a loaded late addition to the story) and in the end it’s wilfully and jovially sentimental, largely because there is no scene where we witness the emergence of Brownie’s vision and the struggle to realise it—we find out about it after the event. Similarly, although the developing relationship between the lovers is nicely handled, the challenges to it becoming a marriage are sidestepped (even though Brownie is elsewhere as frank about Aboriginal racism as white) and the birth of their first child simply announced. Although there are clues to Brownie’s background in his chats with Cuz, there’s not the same attention paid to his growing up as there is to Goldie’s—how did he become a footballer, what of his relationship with his relatives, how is it he’s escaped the pull of alcohol and other traps?

The great strength of Barracking, however, is in its language—the footy coach with his mouthfuls of mixed metaphors, the droll humour that seems an inherent part of the riches of Aboriginal English, and the playwrights’ often deft handling of dialogue. There are ample engaging cultural details, for example in an exchange on playing aids: “Cuz: He was cheating anyway. Them Nungkara rub that ndura on his legs. Brownie: Can’t be. May as well be on steroids, dirty camp dog! So where you get that stuff?” Later, Goldie comments that a player “leaps like one of these big red roos.” Brownie explains: “You know why? He been sung. Them old men sing all night for him, then they call for that wallaby, eagle, kangaroo, anything. Transform him. He’s that kangaroo now.”

Issues of race and culture are woven through the narrative: “Cuz: How any white blokes know your skin, your totem? They don’t know our language, our country. They don’t know ‘cause they got none either.” Brownie is shocked when his white team mates treat him as one of them while using racist language: “like I wasn’t there…it was like them pretty boys didn’t even think I’m black.” And Cuz speculates on cultural difference: “Why you think they don’t have a Territory team in the league? We got enough talent here for a half decent team…Money, that’s why, footy all shop now. Them management take care of business, not spirit. That’s why us blackfellas all over the shop. White man worry ‘bout money first, then spirit after.”

In performance, says Tapp Coutts, “Brownie and Goldie are surrounded by an assortment of characters capably played by just two actors: the bitchy girls on the netball team in Goldie’s teenage years, a university professor, a beatnik boyfriend, the disillusioned Indigenous player who has returned to the Territory, the ghost of Goldie’s father and even an AFL ‘Bishop.’ Raymond Wright, who plays Brownie and has enormous promise, was sighted by director Craig Mathewson at a shopping centre only five weeks before the tour.”

Tapp Coutts reports that “Barracking toured remote regional Northern Territory during August, playing to small crowds of devoted theatre-goers in the Ti Tree Indigenous Community, the Ali Curung Indigenous Community, Tennant Creek, Katherine, Timber Creek and at the Darwin Festival and the Alice Desert Festival. It was a miracle that the performance went ahead in the small town of Timber Creek, 300km west of Katherine, as the road crew vehicle and trailer—with all the staging, sound and lighting—rolled over three times, the equipment strewn across the highway. In true Territorian style the actors proceeded to Timber Creek with a clothes rack and costumes and performed, without sound or theatre lighting against a sheet-covered whiteboard backdrop, to an enthralled 40-strong crowd. Aboriginal children squealed with joy, calling out their favourite footy teams.”

–

Barracking, writers Jane Leonard, Steve Gumerungi Hodder, director Craig Mathewson, performers Tanya Langdon, Raymond Wright, John Robb Laidlaw, Donald Mallard, costume designer Franca Barraclough, lighting Greg Thompson, sound design Steve Gumerungi Hodder, Craig Mathewson, producer Danielle Loy, Red Dust Theatre, Alice Springs; Aug 14-Sept 8

Written by Keith Gallasch with Toni Tapp Coutts, a Katherine-based short story writer who works in remote indigenous communities as Project Coordinator for Katherine Regional Arts.

RealTime issue #82 Dec-Jan 2007 pg. 36

© Toni Tapp Coutts & Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

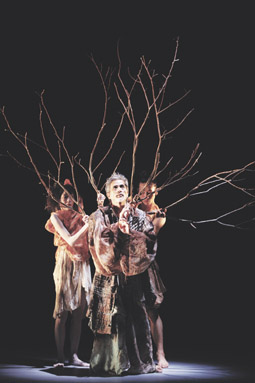

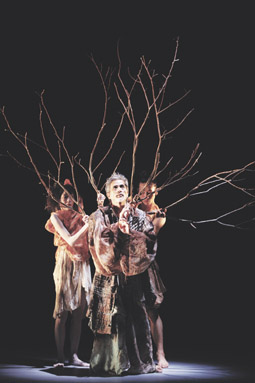

Martha Marthe Mathilde Matthieu, De Kopergietery

photo Phile Deprez

Martha Marthe Mathilde Matthieu, De Kopergietery

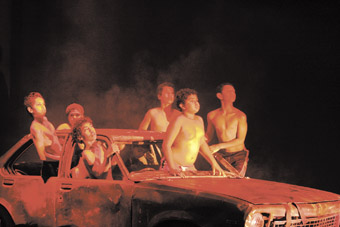

THE 11TH EXPLOSIVE! INTERNATIONAL YOUTH THEATRE FESTIVAL IS, ACCORDING TO THE PUBLICITY MATERIAL, ITS MOST POLITICAL PROGRAM TO DATE, THOUGH YOU WOULD NEVER GUESS IT FROM THE OPENING NIGHT’S SHOW, AMAZONIA, BY BRAZIL’S COMPANHIA APLAUSO. THE SHOW BEGINS WITH PERFORMERS TUMBLING ACROSS THE STAGE AND SCALING UP THE SILKS, ALL WHILE MAKING MONKEY NOISES. WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE. UNFORTUNATELY, THE POLITICS OF THIS PIECE ABOUT A RAINFOREST THAT HAS BEEN RAVAGED BY BOTH COLONIALISM AND NEO-COLONIALISM ARE COMPLETELY AT ODDS WITH THE POLITICS OF ITS PRESENTATION.

There were many uncomfortable moments but the image of a black man standing on stage in a leopard-print loincloth, beaming out at a largely Anglo-Saxon audience, and singing “Brasil!” stands out. Forget the jungle, welcome back to the 19th century, where bare brown bodies are displayed as exotica/erotica for your viewing pleasure. Skin, sex and some capoeira to boot—the Brazilians seemed to confirm every stereotype imaginable in a single performance.

I’m in Bremen, Germany, to perform with Sydney’s PACT Youth Theatre in The Speech Givers, a show which draws on the themes of previous PACT shows such as Toxic Dreams (RT73, p16) and Whistling Man (RT77, p44) but which was developed especially for this festival. After watching Amazonia we are beginning to wonder about what we are doing and why. What exactly is international about an international youth theatre festival? To what extent are companies expected to confirm or contest national stereotypes? And what would the audience make of an Australian show about a series of speech acts that only sometimes succeed?

Perhaps the highlight of the festival was Sehnsucht (Longing or Desire), directed and choreographed by Belgian Ives Thuwis and performed by the Forum Freies Theater from Dusseldorf. It begins with the director dancing, slowly at first and then with increasing rapidity until his breath becomes laboured and loud and he retreats to the side of the stage. In what follows, 11 performers aged between 10 and 20 proceed to evoke the barely contained chaos of a party without parents. To the strains of Dusty Springfield’s “Son of a Preacher Man”, Audrey Hepburn’s rendition of “Moon River”, and Sonny and Cher’s “I Got You Babe”, a young woman sips water through a straw from the crevices (ribs, clavicle, navel) of a young man’s torso. There is a tense pas de deux between two teenage boys, which proves too much for one of them so he heads across stage and tackles a teenage girl to the ground. She escapes his grasp and stalks off to the couch to sit in a silent sulk, trying but failing to avoid the early onset of post-party blues.

The younger children are oblivious to all this teenage angst, busy as they are playing ping pong, hiding under the table and sending out a string of paper boats across the floor. Once in a while the two groups interact—a young boy spies the sulky girl changing and decides to steal her dress. One tender moment has three of the older members of the group spooning their slightly younger counterparts. It is as if they are already dancing with younger selves, a reminder that you are never too young to experience nostalgia and that even at 16 you can still miss your 10-year-old self. More importantly, it reminds us that there is no such thing as a singular ‘youth’ and therefore no such thing as a singular ‘youth theatre.’ The piece comes to climax with an ecstatic version of Lesley Gore’s “You Don’t Own Me” before the director, who has been standing and watching the entire time, comes back on and dances again.

The songs are the soundtrack of the director’s youth not the performers’ but because the work is so accomplished we tend to forgive him the indulgent framing device. Besides, perhaps it’s a metaphor for working in youth theatre where one is forever standing ‘in the wings’, casting an adult eye over the chaos, trying to harness erratic energy while instilling a degree of discipline in those beautiful bodies that, ultimately, are not yours to inhabit or even to inhibit. Indeed, they always emphatically reply, “You Don’t Own Me.”

Thuwis also collaborated on a performance on the next night, Martha Marthe Mathilde Matthieu by De Kopergietery (Gent, Belgium). Each child of the title worked with a professional choreographer, resulting in four curious portraits. These might also have been called Bedroom Boredom because they are about what children do—or more accurately what adults think they might do—when left to their own devices. The first girl walks in wearing what looks like a red party dress but she soon throws it off in favour of some far more comfortable black pants and a loose blouse, freeing her to gallop around the room. She flings cushions about with abandon, turning them into a trampoline to bounce on, a sea to swim in, and skates to glide on. She is utterly absorbed and utterly absorbing but when an older girl comes in wearing her party outfit and carrying a birthday cake, the smaller one scampers off.

Alas, this new girl does little more than loll about on the floor like Lolita. While the piece itself is uninteresting, the juxtaposition with the previous portrait is arresting. What is it that happens to girls? How can someone be so full of agility and agency and then a few short years later be boring beyond belief, desiring nothing more than to be desired? The contrast between this learned feminine passivity and masculine activity becomes even more apparent when a teenage boy enters. He doesn’t have half her grace but he is far more intriguing. Loud music blares from his laptop and he lurches around the room, doing bad stunts and telling bad jokes but thinking sweet thoughts. Eventually he steadies himself while listening to the Counting Crows intoning, “I am ready, I am ready, I am ready, I am.”

The extensive use of popular music—entire songs played back to back—recurs throughout the festival though not always to the same effect. In fact, the songs in Schauspiel Essen’s show Homestories (ballads for the girls and hip hop for the boys) are interspersed with the personal stories of the performers, as well as some odd but occasionally compelling video footage they shot in and around their home town of Essen-Katernberg. Unlike Sehnsucht and Martha Marthe Mathilde Matthieu, Homestories is instantly recognisable as ‘youth theatre.’ The production was facilitated by Armenian director Nuran David Calis who lived in the city of Essen’s troubled social district of Katernberg for six months while collecting the stories of the young collaborators, many of whom are migrants. Homestories had been awarded the Sociale Stadt 2006 (Social City 2006) prize so perhaps the social coherence it promotes is more important than the artistic coherence it lacks.

What is obvious from these three performances, as well as from the production of Hamlet (co-produced by the festival’s German hosts, the Schlachthof theatre, with the Dutch company Growing Up in Public theatre and the Danish director Jeroen Kriek) is that they do not explicitly engage with notions of nationality. Indeed, through the very fact of their being, these ‘international’ collaborations simultaneously ignore and problematise the idea of the nation. This implicit approach contrasts with the rather blunt approach of the last show, k-ENTER-n, which looks at issues of globalisation through a regrettably rudimentary lens. If Amazonia resorts to national caricatures then k-ENTER-n, which was also produced by Schlachthof theatre, resurrects socialist clichés. The play has evil corporations threatening to take over the world via the internet and the program even refers to the “stormy oceans of capitalism.” PACT’s The Speech Givers is neither an international collaboration, nor agit-prop theatre, nor an attempt to think through the identity of Australia. Even so, it may have been interpreted that way, with people commenting that the show was ‘very athletic’ or that they were expecting something ‘sunnier.’

Far from sunny, The Speech Givers depicts the necessity and impossibility of speaking in general, and of speaking up and speaking out in particular. The six performers prepare the space and then themselves to stand and deliver the speech of a lifetime. These public speeches are well-intended but ill-executed—white noise overwhelms one speaker while a wave of mass hysteria sinks another. More private speeches happen when performers accost one another as they stride across the stage, cruising the corridors of power. Once again, the speakers are inaudible, inscrutable, impossible. Ultimately, whether public or private, promising or compromising, these speech acts are also solitary acts, monologues that may or may not be understood by the addressee. The piece finishes with the six performers and the sound artist walking to the front of the stage and sitting face to face with the audience. Together they listen to the strains of Elgar’s Chanson de Matin and look at the strain on each other’s faces, suggesting that perhaps the most radical speech act of all is to sit and listen, to try and move beyond monologues towards dialogue.

Perhaps this is the point of the festival more generally: to introduce artists to other artists and to other audiences and in doing so to start a quiet conversation. Nothing more and nothing less, but still no mean feat in an age of megaphone diplomacy.

1tth Explosive International Youth Theatre Festival, Bremen, Germany, Sept 14-15, www.explosive-info.de

RealTime issue #82 Dec-Jan 2007 pg. 38

© Caroline Wake; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Louis Fitzpatrick, David Buckley,

Deborah Pollard, Blue Print

photo Heidrun Löhr

Louis Fitzpatrick, David Buckley,

Deborah Pollard, Blue Print

FOR FRENCH PHILOSOPHER GASTON BACHELARD, THE CHILDHOOD HOUSE REPRESENTS THE SHAPE OF THE HUMAN PSYCHE: A MEMORY CONTAINER STACKED WITH DELICATE OR DANGEROUS TRACES OF THE PAST. STAIRWAYS, LINEAR AND ANGULAR; OPEN-PLANNED SPACES LEADING INTO LIGHT AND SHADE; UNDERGROUND CELLARS THAT REPLAY THE DARKER RECESSES OF THE MIND. THESE ARE THE CAVITIES AND GEOMETRIES IN WHICH WE GROW ACROSS TIME. WE EMBODY THESE SHAPES AS THEY SHAPE US. THINGS GET STORED IN SUCH SPACES: OUR OBJECTS (A BROTHER’S LOUD‘N’DUSTY LED ZEPPELIN COLLECTION) AND OUR MEMORIES (ANGER, GRIEF, RAGE…A PETRIFYING AND ANGUISHED SCREAM ACROSS THE TELEPHONE…).

Deborah Pollard’s personal reflection on the loss of her childhood home in Blue Print is a reverie in response to the devastation of the 2003 Canberra bushfires. “After a firestorm”, the opening projections explain, “there is silence…no lawnmowers…no trees.” These bushfires are remembered for their absolute destruction, swallowing two thirds of the region in flames, gutting 501 houses and killing four people. For Pollard, it is the 501st house that offers a statistic of humanity amidst such mammoth anonymity. She likes to think of the oddly numbered house as her house; the one uniquely singled out amidst those many others.

A phone sits centre stage, ominous symbol of events to unfold. Around this, Pollard paces out the plan of her childhood house, using a linemarker to chalk the floor with rhythmic precision to reveal stairways and doorframes. Her poise is strong and calm but her actions (obsessively precise) tell a different story. In her act of both retrieval and grief, we watch the house emerge from muddied beginnings into a vision of its former glory. Recorded interviews are cut against Pollard’s action, and we hear relatives recollecting the moments leading up to what is now (we know) predestined destruction. Anecdotes, memories—the minute administrivia of everyday families in the thick of everyday life—crackle across the audio sphere. At times emotive, at times teetering unnervingly towards the feel of Australian Story reportage, voices fill the space with an empty, nostalgic echo.

Sentiment in words and action is undercut by the presence of three anonymous firefighters. Like bright yellow stock characters, they sprint across the space, pull ropes, or convalesce, blackened and exhausted, against a smoking Christmas tree. These are the uniformed tricksters who animate Pollard’s backstage psyche. They have moments of partytime, exhaustingly head-banging to Led Zeppelin’s Dazed and Confused (a comment on the dubious commitment of ACT authorities to the prevention of the fires?). They also have to deal with staggering grimness, pulling a heavy, life-sized dead horse—inanimate, flopping and falling across the space. The horse is rendered in a lifeless darkish purple, making it a metaphor for all the loss that this scene has witnessed. It is pathetic, ironic, tragic, disgusting: a striking image against the mundane simplicity of Pollard’s home world.

Sound (Gail Priest) and video (Samuel James) also introduce curious signifiers into the space. A door frame seemingly grows and retracts like a worm on the upstage projection screen. The door bleeds into visions of a burnt-out, trunk-laden landscape against the searing horizon sun: that archetypal image of an Australian bush summer, holding smells of Christmas and heat and soggy roast chicken in its iconography. Sound evokes an ambient melancholy, occasionally mimicking the gentle crackle of fire, but often gestures emotively, underlining stage action and story.

Blue Print is less about smoke and fire than the innate trauma of time passing: of losing the touchstone of what is most familiar and known. And yet, amidst such potency, there is an aura of stasis in Pollard’s theatre of recollection. We watch the performer looking at her leftovers—the psychic residue of her childhood home—without much hope of revelation. Memory is like this too. Cyclic and unrelenting, it can make inertia out of the very catharsis that it would rather seek. The poetic transcendence that theatre brings to stories of trauma can elevate the personal into a shared sense of insight and healing. In Blue Print I was strangely unmoved by the scenescape of recuperated bits and pieces. I couldn’t help thinking that all childhood houses disappear in one way or another—it’s how their corners and geometries have shaped us that counts.

Blue Print, devisor, performer Deborah Pollard, performers David Buckley, Daniel Fenech, Louis Fitzpatrick, dramaturg John Baylis, video design Samuel James, horse design erth, sound Gail Priest; Performance Space, CarriagWorks, Sydney, Oct 26–Nov 4

RealTime issue #82 Dec-Jan 2007 pg. 39

© Bryoni Trezise; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

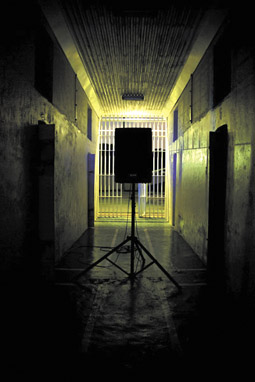

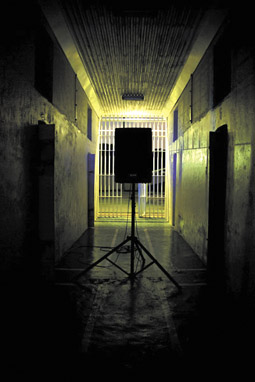

Sounds Unusual, Fannie Bay Gaol

photo Tanja Kimme

Sounds Unusual, Fannie Bay Gaol

THE 2007 SOUNDS UNUSUAL EVENT BEGAN IN ALICE SPRINGS THIS YEAR AS PART OF THE ALICE DESERT FESTIVAL BEFORE MAKING THE JOURNEY THROUGH DESERT TO COAST TO DARWIN TO PRESENT SURREALESTATE AT FANNIE BAY GAOL AND ISLANDS:CROSSING IN WHICH FIELD RECORDINGS BOTH AUDITORY AND VISUAL WERE COMBINED FOR MULTICHANNEL SOUND AND NEW MEDIA INSTALLATION AT THE DARWIN VISUAL ARTS ASSOCIATION (DVAA).

Director Rob Curgenven likes to gather audiences in historical Darwin sites, previously the WWII oil tunnels and this year Fannie Bay Gaol. These significant sites provide more than a backdrop, often dictating the overall listening compass. The essence of these events is an individual’s experience of a textured and tactile listening world, performed in a venue with great acoustic potential and theatrical presence.

The opportunity to explore the grounds and in particular the maximum security building where surrealestate was performed provided sombre reflections on 96 years of incarceration including that of Lindy Chamberlain. Many of the inmates gaoled here languished under appalling colonial policies which were racially prejudiced against Chinese and Aboriginal Australians.

Blastcorp (aka Kris Keogh), one of Darwin’s most invigorating performers, teamed with newcomer Ruben from The Fairweather Dolls to provide an appropriate ‘Welcome to Darwin’ set. Jason Kahn from Switzerland performed a solo for analog synthesizer and percussion, and then completed the event in an improvised duet with Curgenven’s field recordings and instrumental harmonics.

Sounds Unusual, Fannie Bay Gaol

photo Tanja Kimme

Sounds Unusual, Fannie Bay Gaol

Kahn’s sleight of hand across the snare drum created a gradual, entropic state change which was mesmerising. His right hand shimmered over an inverted cymbal while his left deftly controlled the output on the analog synthesizer. Minute changes to the position of the cymbal over the drum created dramatic sonic resonance via an overhead microphone. It seemed the slightest movement from the audience within the cell blocks also impacted on the sounds in the space.

There was a cyclonic build-up of volume as superseded sounds echoed down the darkened tunnels of cell blocks A & B. Speakers formed horizontal columns of sound either side of the audience.

The performance paralleled Darwin’s most famous sound recording, Cyclone Tracy, which plays in a dark room at the Northern Territory Museum & Art Gallery. The gaol is one of the survivors of that disaster. Kahn, perhaps unaware of this uncanny connection, drew us to an immersive finish of gentle dissipation.