Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

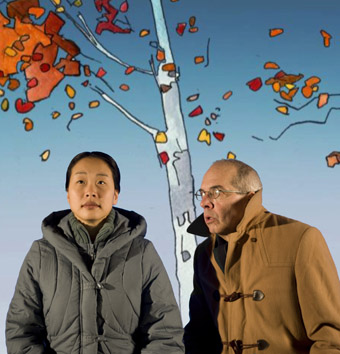

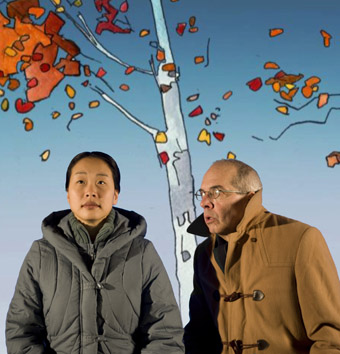

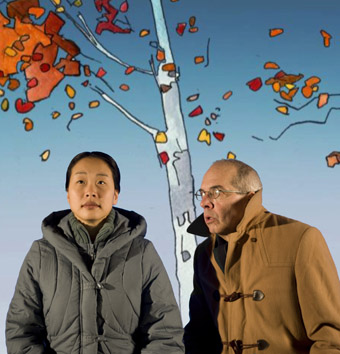

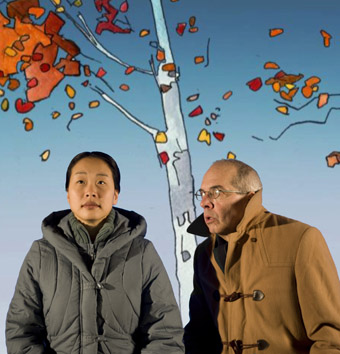

Small Metal Objects

photo Jeff Busby

Small Metal Objects

It’s hard to describe the sense of freedom you get watching this show. To start with, there’s the freedom of being outside the usual theatre box. Small Metal Objects (performed by Australia’s Back to Back Theatre) takes place in the atrium of the Vancouver Public Library, a crescent shaped concourse with a glass ceiling many stories above. On one side of the concourse is the library itself, also fronted with glass, all the way up, it’s insides open to view. On the other side are the cafes, flower shops and pizza parlors. We’re sitting on a narrow bank of seats somewhere in the middle. Crowds flow in and out of the main library entrance. People sip lattes, read newspapers or eat snacks at the shop tables. Each person in the audience stall is wearing a set of headphones. To the passersby, we may look a little odd. To us, they just look like normal people doing normal things. ‘Normal’ is a concept that will be unpacked in a most ingenious and surreptitious manner over the next 50 minutes. When it’s done, we may never feel normal again. But we may feel a lot freer.

We’re sitting on a narrow bank of seats somewhere in the middle. Crowds flow in and out of the main library entrance. People sip lattes, read newspapers or eat snacks at the shop tables. Each person in the audience stall is wearing a set of headphones. To the passersby, we may look a little odd. To us, they just look like normal people doing normal things. ‘Normal’ is a concept that will be unpacked in a most ingenious and surreptitious manner over the next 50 minutes. When it’s done, we may never feel normal again. But we may feel a lot freer.

A conversation begins in the headphones. Voice One (male): “Cooked a roast last night. Think it was chicken.” Voice Two (male): “I love chicken.” Space. A couple of spare piano chords. Voice One: “Celebrated my 15th wedding anniversary.” Space. Piano. Voice 1 again: “If a guy with a gun came at my wife and my kids I’d take the bullet for them.” The conversation continues like this for some time. It’s affectionate, honest, witty. It may be pre-recorded, we don’t know yet. Voice Two talks about how much he wants “to give,” to help, that he’s worried he’s gay because he doesn’t have a girlfriend, that if he were famous he would give every needy person in the world 825 grams of food a day. Voice One has great ideas too: he wants to get into the self-storage business because these days people don’t throw things away. In the same breath he mentions childcare as another good bet, presumably because people don’t throw children away either. The general movement of the crowd continues. Suddenly I see the source of the voices: at the far end of the atrium two men are slowly moving in our direction. They both have headsets on. One of them is a skinny, medium height brunette; the other is short and heavy-set with a blonde buzz cut. It turns out Voice Two belongs to the brunette, who’s name is Steve (Simon Laherty), while Voice One belongs to the blond, Gary (Sonia Teuben).

As they get closer, we can see by Steve’s movement, and by the performers’ physical appearance that the actors are mentally/physically ‘challenged’—a concept that is already beginning to be stripped of the logic of prejudice. After all, they were having a conversation that might be attributed to any two ‘normal’ guys, one who’s been married for 15 years, the other who is lonely and confused about his sexual orientation. The gentle pace of the performance, supported by a hypnotic sound score, is at odds with the usual rhythm of the concourse. Gary and Steve seem to inhabit a parallel world; the people who sit at neighbouring tables haven’t taken notice of them. The actors are almost like spirits. They take their time with every exchange. The crowd speeds past. We are witnessing a genuine clash of cultures: one is slow and considered, one is madly goal-oriented. We know which one we usually live in.

By the time the next character appears we’ve been well massaged into the culture of Steve and Gary, and judging by the grinning faces around me the audience is grateful for the experience. Allan (Jim Russell) is a speedy big time realtor. He’s putting on a major function and needs to furnish his clients with drugs. And here’s another challenge to our expectations: Gary and Steve are dealers. Allan doesn’t have much time. Gary is happy to furnish him with the goods, but things have to proceed at a pace that doesn’t suit Allan’s pressing agenda. To complicate matters, Steve has become immobile. He’s “deep in thought” and refuses to go to the lockers to get the stash. As much as Gary would like to accommodate Allan, he won’t abandon Steve, so the deal’s off. Allan phones for support from his psychologist, Caroline (Caroline Lee). Lee, who is a motivational consultant for large corporate clients, arrives, and the two ‘normals’ get to work, soothing and cajoling Steve—Caroline offers everything from free consultations to (when she gets most desperate) a blowjob. Most significantly, she appeals to Steve’s desire to improve himself, to become a happier, productive, more efficient person. This is the dialectic that has been playing throughout: Steve and Gary’s culture is based on personal bonds, on trust and human compassion; Caroline’s and Allan’s is utilitarian. As Steve and Gary say, “Everything has a value.” Caroline and Allan would agree with this statement, but in their world value is equated with productivity.

Small Metal Objects doesn’t present a utopia. It simply defines the ethos of two contrasting cultures. In the current paradigm, we demand that Gary and Steve play by our rules. We reward them inasmuch as they are able to conform to our standards of successful behavior. Small Metal Objects reverses the paradigm. Allan can’t adjust to the values that supercede getting what you want when you want it. He and Caroline simply cannot speak the language of the minority culture they are confronting. The performance raises a whole host of concerns about ‘otherness’ and difference that can be applied to so many aspects of our fractured world, whether we’re looking at issues like racism, poverty and other forms of exclusion on a community level, or whether we’re facing macro issues like global military conflicts. That sounds heavy-handed, something this show is resolutely not. The superb ensemble playing of the cast, the deft direction of Bruce Gladwin, and the mesmerising sound design of Hugh Covill reconfigure the atrium, removing density from the space between passersby, unlocking new ways of seeing—no, of being—for those of us consciously taking it in.

It’s appropriate that this happens at a library, because we are getting a first class education here. This is what great art can do. It can re-organise your bones, re-wire your brain, and perform open-heart surgery all at the same time. Far from the confines of a theatre box and from the spatial concerns that accompany conventional scripts and conventional acting, we get to re-imagine how the conflicting cultures of our world might fit together a little easier, what little adjustments it might take for us to approach each other and make contact with difference. It’s a very moving exercise in the art of the possible, and it left me with a surprisingly untainted sense of hope.

Back to Back Theatre, Small Metal Objects, devisers Bruce Gladwin, Simon Laherty, Sonia Teuben, Genevieve Morris, Jim Russell, director Bruce Gladwin, performers Simon Laherty, Sonia Teuben, Caroline Lee, Jim Russell, sound design & composition Hugh Covill; Vancouver Public Library, Central Branch Promenade, Jan 30-Feb 2

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 10

© Alex Ferguson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The General

You’ve got to enjoy this one. Before the movie starts, the outrageously accomplished Eye of Newt ensemble warms up the crowd with a jazz improvisation that foreshadows some of the tactics it will use to underscore Buster Keaton’s classic film The General. Stephen Smulovitz (violin and saw) and percussionist Pepe Danza start off with a weirdly haunting violin–mouth-harp duet that pulls at the heart while relaxing the body. Paul Plimley then layers in a piano ‘score’ that echoes the movie’s original soundtrack while maintaining a contemporary feel. Plimley, Danza and Paul Blaney (double bass) will drive us through the emotional peaks and valleys of Keaton’s epic slapstick journey, with Brad Muirhead’s trombone and Smulovitz’s saw adding comic inflection. The trombone, and the violin and saw (which sounds a lot like a theremin, actually) will also create dissonance, colouring the film’s original moods with a palette of exquisitely darker tones.

The pre-show improvisation has the effect of activating our imaginations and surreptitiously encouraging our vocal participation with the movie. This was a surprise to me — I hadn’t expected people to cheer and clap at Keaton’s antics. I’m used to movie patrons who are well behaved. But if the film has suffered any lack of impact since its 1927 debut, Eye of Newt and the enthusiasm of an all-ages crowd restored its immediacy. Keaton’s inventive choreography and physical daring prompted cascades of laughter, squeals of delight and more than a few gasps.

In the film’s American Civil War setting, Johnnie Gray (Keaton) is a Confederate train engineer who has but two loves: his engine “The General,” and Annabelle Lee (Marion Mack). Annabelle is a patriot, so when Johnnie is rejected by the army he falls out of favour with her. She tells Johnnie not to show his face again until he’s in uniform. Johnnie redeems himself by diverting a Yankee attack almost single handedly, and by rescuing Annabelle (who was inadvertently kidnapped by a guerrilla unit).

There are plenty of heart-stopping train stunts and enough tumbling feats of daring to keep our eyes popping and our necks craning. Eye of Newt matches Keaton stunt for stunt. The musicians catch every pratfall and every double take. They have an arsenal of well-timed responses to the shifting moods of this surprisingly layered film. The General is given an infusion of new blood by Eye of Newt, just as Johnnie is redeemed when his commanding officer gives him a new uniform. Keaton was at the top of his game when he made The General, almost in a class by himself. It’s fitting that for this engagement he has been paired with five players whose powers inhabit the stratosphere of musical invention and ability.

Sherry J Yoon, James Fagan Tait, My Dad, My Dog, Boca del Lupo

The letterbox orientation of a typical movie screen is turned on end, vertically stretching from floor to ceiling. Like the rest of My Dad, My Dog this is just a gentle adjustment of accepted convention, not an aggressive challenge. A small picture frame appears on the screen, about the size of your bedroom window. Inside it, an animated dog skips through an animated fall landscape. The dog roams across the bottom of the large screen taking the frame with it. It’s as if we’re looking through a rectangular telescope. Then the dog arrives at the trunk of a tree and chases off a pigeon. Leaving the dog behind, the frame travels up the trunk into the boughs. As it reaches the crest we hear a crash, the tree shakes and sheds it’s leaves, the picture disappears.

This whimsical passage comes early in Boca del Lupo’s My Dad, My Dog, a delightful show that plays live action against a vast canvas of animations that are a wonder to behold. The dog scene offers us one possible way of exploring what’s to come. While taking in the whole, we might use a selective eye to pick out details that suit our sense of narrative. A similar technique is used a little further along. James Fagan Tait (there are no character names in the program) is an ornithologist searching for the rare white-necked red-crowned crane, which is found only in the demilitarized zone (DMZ) that separates North and South Korea. He stands before the screen, now filled from top to bottom with animator Jay White’s depiction (a fluttering watercolour) of the DMZ. Looking not-too-hopeful about ever finding the rare bird, Tait exits. A live-camera feed from a mini-stage set up at the left side of the stage allows White to project his own hand holding a magnifying lens onto the large screen. It finds the crane in the foliated background. So this story is also about not seeing things — like seeing the tree shake but missing the crash. Framing certain things implies excluding others.

And there’s another story-telling technique at play here. Telling a story is always an act of translation. There’s a possible source event, someone puts that event through a subjective filter and transmits it to someone else. The storyteller may use the biological machinery of his or her body (lungs, larynx, mouth etc), or technological aids — a pen, a camera, a computer. I think we usually picture story telling proceeding in that order: original event, internal translation, re-telling. But in My Dad, My Dog the order is reversed. Sherry J. Yoon imagines her way back to a North Korea she has never visited and to a woman who doesn’t exist but is a plausible type for a relative she might have there. It’s like creating a photo album of a vacation you never had.

Well that’s just what fiction is, you say. And you’d be right. But Yoon takes pains to frame this fiction as a search for a missing part of her family story. She offers biographical details of her ‘real’ life (“I am Korean”) as the starting point for an investigation into her relationship with her father. She imagines her father reincarnated as a North Korean dog. When Yoon is not performing herself she plays the part of her North Korean alter ego, who works for the government monitoring and limiting the movement of visitors to her country. She visits the dog chained up in an alley and talks to it, believing it will understand her (in one hilarious scene the dog complains to a fellow canine that he can’t understand the woman because she’s speaking English). Yoon, as herself, returns to the stage periodically to tell us which parts of the story are true (and exactly what she means by ‘true’) and which are inventions. The difference is as important as we want to make it.

Often the characterizations are made deliberately flat, while animations like the dad-dog almost jump off the screen and display a psychological complexity the humans lack. The blurring of fact and fiction is kept in play. We realize that, to some extent, we all assemble our ‘selves’ from a patchwork of memories, dreams and desires. We put a frame around that which we accept as ‘I’, as ‘me’, and leave out the rest.

The autumn colours on screen and the delicate figures of Alicia Hansen’s piano compositions give the show a very west-side-of-Vancouver feel. There’s a lot of light-hearted dialogue about the character of the city: “Vancouver seems liberal but it’s conservative. But not as conservative as Toronto.” These comments aren’t serious digs. For the most part, My Dad, My Dog doesn’t try to be the last word on any issue. But after a while it starts circling itself. The content and episodic structure gets repetitive —I don’t think this is a deliberate narrative strategy. The animated sequences, mesmerizing as they are, become devices not always integral to the theme. The attempted resolution — “sometimes there are no answers” — felt pat to me. It felt too much like an answer, it created closure to that which might have remained open.

But then again, maybe I was looking in the wrong direction. It would be like me to put a frame around the thing everyone else thought was irrelevant. You know, looking at the tree and missing the crash. Oh, but maybe that was the point. Or lack of a point. Um, throw up another cool animation, the critic is leaving the stage.

Sherry J Yoon, My Dad, My Dog, Boca del Lupo

A tall, blank screen dominates Boca del Lupo’s My Dad, My Dog. The screen fills with a variety of images, some animated, some magnified sets and props manipulated live by Jay White, who stands on one side of the stage, wearing an apron like a modern day Geppetto. The images are sharp and effective, forming clever backdrops to the action, with White’s monstrously magnified hand appearing occasionally to open doors and move furniture. It looks great. And anyone who grew up in Canada with the Friendly Giant will no doubt smile. Although the projections were high-tech there was something old fashioned about the whole artifice. The machinery White operates reminded me of a doll-sized opera house. This sense of 19th century stage-craft was nicely complemented by the live piano playing of Alicia Hansen who resides on the opposite side of the stage from White.

Before seeing the My Dad, My Dog, a number of people told me they found it charming or delightful. While the imagery created by White gives the show a lyrical and at times child-like softness, this work is steely at its core. Even the central narrative conceit embodies this tension. Sherry J Yoon, one of the creators and performers, appears at the top of the show as herself to explain what inspired the piece: she became convinced that her dog was her father reincarnated. While this might appear an absurdist notion—at least to Western ears—it evokes a painful story of death and, as Yoon alludes, the fate of the soul of a violent man. Precisely what the steel core of My Dad, My Dog is remains a mystery to me, a blank, and maybe this is appropriate.

The play is set in one of the last blank spots on the map: North Korea, a world we only glimpse through government controlled images. This is neatly played out when one of the characters attempts to take photos. We see what the foreigner sees through his viewfinder projected onto the screen: animated drawings of the rough and tumble of North Korean life. The translator moves the Westerner’s arm so that a sanitised, acceptable image is framed. The camera flashes and the drawing is replaced by a photo. The photos, which already have an inhuman bleakness to them, are made even more ominous. This filling in blank screens with controlled images set against what our imagination creates is a central motif of the work and one that is played with very effectively.

Yoon, who was born in Korea, tells us about the numerous cousins she has spread over both sides of the border separating North from South Korea. She plays an unnamed translator, an alternative version of herself had she grown up in North Korea. She portrays this character with a remarkable level of formality and control: another blank slate. Her interactions with two unnamed Canadians, a bird-fancier from Vancouver (James Fagan Tait) and a filmmaker from Canada’s east coast (Billy Marchenski) are filled with frustrating literalness. Everything is taken at face value. The translator in fact does no translating. Her job is to speak English to foreigners so that they understand what they can’t do. Her blankness is only really broken through her relationship with an animated dog. The other two characters also have their familiars, the Tait character has a pigeon, the filmmaker monsters, specifically King Kong who looks through his hotel room at one point. The Tait character, whose bird obsession makes him a self-imposed outsider, is a nice counterpoint to the state-sanctioned translator. The filmmaker’s relation to the other characters is not so clear and his reason for being in North Korea—to make a monster movie—stretches incredulity, even in a piece that stars an animated dog. I suspect the filmmaker character was created to underscore the theme of blank screens and the creation of images, but it doesn’t quite hang together for me.

The relationship between the performers and the projected images has something to do with the blank screen itself. This is most obviously illustrated in two scenes set in a restaurant. White draws the restaurant for us while the scenes unfold. We watch random lines form recognisable shapes of tables and diners. Towards the end of the scene the filmmaker notes that people in the restaurant are looking at them. Direct interaction between the actors and the images on the screen is limited and therefore becomes pointed: the translator engaging with her dog and the bird-fancier releasing a pigeon. In these moments, it is almost as if the actors are puncturing the blankness of the screen, using their familiars to achieve this transition to an unknown other side. This somehow relates to the motif of reincarnation and the cycle of creation and recreation. The almost too sweet lyricism of the last scene—a released bird making its way across impossible odds back to Vancouver—is cut short by a moment of cruel humour. The transition between worlds, of crossing over into blankness is not without its danger.

Boca del Lupo, My Dad, My Dog, created by Sherry J Yoon, Jay White, director Jay Dodge, performers Billy Marchenski, James Fagan Tait, Sherry J Yoon, animation and scenography Jay White, music Alicia Hansen, costumes Reva Quem, lighting Jeff Harrison, Jay Dodge; Roundhouse Community Arts and Recreation Centre, Vancouver, Jan 25-26, Jane 29-Feb 2; PuSh International Festival of Performing Arts, Jan 16 – Feb 3

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 6

© Andrew Templeton; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

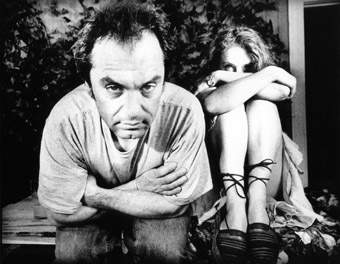

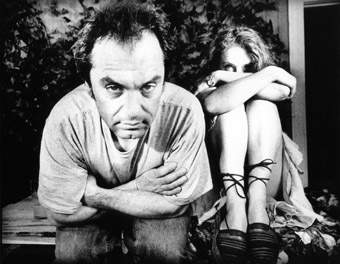

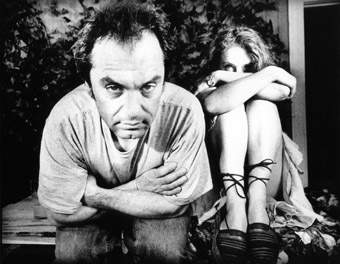

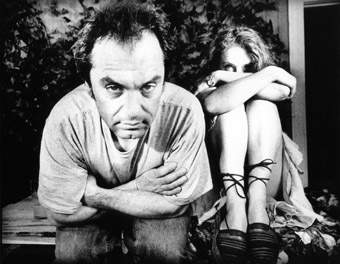

Nigel Charnok, Fever

photo Th. Ammerpohl

Nigel Charnok, Fever

Nigel Charnok comes on stage with energy so fierce it’s hard to decide what’s going on. With his long legs and arms whipping out in all directions, he might be a great black stork gone crazy, or an enormous bird of prey in crisis. Soon he runs through agitated, fast-paced gestures of grabbing his crotch, slapping his neck (with cologne?) and raising his wrist to his eye as if to check the time. Perhaps an addict, desperate for sex and preparing for a date that’s bound to be disastrous? The theory is temporarily strengthened when he crams the waiting microphone into his mouth and it amplifies his gasps. By the time he swings the microphone stand crazily around his head, I’ve figured out what he reminds me of: the last, drunken guest at a brilliant party, who will simply not go home.

Charnok’s collaboration with jazz musician Michael Riessler and the Virus Quartet is a theatre work with three elements: Charnok’s words and movement, Riessler’s music and Shakespeare’s sonnets. Of the three, we get to know Shakespeare least – the sonnets are almost incidental to this one-person riot. Every so often Charnok recites one of them; usually he distracts us at the same time. Only once he admits to the power of the music on stage and removes himself: “this is really beautiful. I shouldn’t be talking. Listen to this.” He sits down in the audience half-way back. The sonnet he recites next is quiet and meaningful, in a way the others haven’t been, because we can’t see him, and he isn’t drawing our attention away.

The disciplined, rich sound of the quintet sometimes provides a middle path between Charnok’s mania and the sonnets’ formality, but it’s not always enough to stave off disorientation. Even Charnok has to remind himself to make the transition sometimes. “Oh, Shakespeare, right”, he says, after a rambling rant on Starbucks and Afghanistan. And then we’re wrenched into “O cunning love, with tears thou leaves me blind” as he hides behind the upstage blacks.

At one level, Fever is a classic introductory text to postmodernism. The work is endlessly self-aware and repeatedly deconstructed. It’s also very funny. Charnock never stops moving as he reminds us that we are an audience, although apparently we’re better than last night’s. Unlike that lot, we’re clearly “a collection of very fine, receptive, elegant human beings.” He lets us in on the music ensemble’s emotional state: “They’re all jet-lagged and I’m in a bad mood,” but assures us “it makes for great art.” Stripping down to near-nudity as the night proceeds, he runs bare-legged, sweaty and disheveled around the stage. More and more deconstructed himself, he exits and comes back on, looking at a polaroid of his own butt, to tell us it isn’t the end of the show but “we’re very near.” Then he refreshes himself from a water bottle, and spits it over the audience.

Much of the deconstructionism is applied refreshingly to modern dance. “I don’t know what the fuck I’m doing,” he says, striking a pose with knees braced together, one arm flung to the side. “Do you have any idea what this means?” After the show, he tells us some of modern dance is “a big con.” Certainly for much of the work he dances the way a child or a drunk might, exuberantly, with a “look what I’m doing now!” spirit to it. We might have been conned, because he makes us watch it, and he calls it art. But we’re happy for a chance not to take modern dance seriously.

The work is modular, with a mix of composed and improvised sections organized according to set cues. Charnok claimed afterward that he and the musicians “ignore each other most of the time,” but the superb clarinettist (Michael Riessler leading the quartet) watched Charnok’s every gesture closely during their duets. Charnok maintains a studied indifference to the work. “It doesn’t really matter. That’s what gives me the total freedom. It’s happening for no one and I’m not there…. I’m really not there.” His attitude can sound disrespectful – to the audience and to the work. But Shakespeare can take it. So can Riessler and so can we. Let’s hope modern dance can too. It if can’t, it’s in trouble.

Drunken party guests aren’t known for their concern for others, but they still work hard for attention. Charnok craves our gaze. He may say what he’s doing doesn’t matter, but maybe he cares more than anyone. Unlike the last, late guest who’s despoiling the furniture and taking polaroids of his body parts, I didn’t want him to leave.

Henri Chassé, Annick Bergeron, Août – un repas à la campagne

photo Rolline Laporte

Henri Chassé, Annick Bergeron, Août – un repas à la campagne

It seems we’re about to take a stylistic journey into theatre history. Before us is a detailed replica of the front porch of an old Quebec country house. There’s a swing, a few lawn-chairs folded up at one side, a front door screen, windows that look into the rooms, little details like an overturned bucket under the porch. There’s an orange extension cord running out from the house and a power drill sitting on the swing. As the patrons take their seats, an actor walks out and uses the drill to put a new plank in the front steps. Soon we will meet the family that lives in the house, four generations of women and a few of their spouses. They will present nicely layered naturalistic character portraits rich in physical and psychological detail. Cars will honk off-stage, crows will caw.

Actors will wipe away imaginary sweat and present languid bodies oppressed by summer heat. They will speak dialogue that, through a century or more of theatrical convention, we have come to accept as ‘everyday’. The playwright will carefully note the psychological cause-and-effect that motivates each character. And like the 19th century progenitors of this type of play, he will insert a symbolic element (here, a seven foot garter snake) that adds mystery and is the key to unlocking the deeper meaning of the work. It will all be handled rather deftly by actors who have raised their craft to a fine pitch. And I will wonder if we still need naturalism in theatre, and whether I should be at the movies instead.

There’s a distinctly Chekhovian quality to Aout – un repas à la campagne (August: an afternoon in the country) produced by Montreal’s Le Théâtre de La Manufacture, and written by Jean Marc Dalpé. It’s the story of a family whose fortunes, for generations, have been tied to a maple tree plantation which is now failing due to devastation by acid rain. Jeanne (Sophie Clément) the matriarch, is dutifully running the household while trying to keep her daughter Louise (Annick Bergeron) and granddaughter Josée (Catherine De Léan) in line. She also has to keep tabs on her husband Simon (played by the playwright), who has ambitions to make the plantation turn a profit again, but who suffers a heart condition that lays him out when he gets over-excited. Josée, 19, wants to cut and run to start a screenwriting career in the big city. She’s also bulimic, and for that reason Jeanne tries to keep her under a watchful eye. Daughter Louise, married to Gabriel (Henri Chassé), is a realtor having an affair she hopes will be her ticket to California and out of here. Gabriel is a hard working, beer drinking, salt-of-the-earth type, who tries to pull Louise back into their twenty-one year marriage. Grandma Paulette, played by the 86 year old Janine Sutto, an acting legend in French Canada, masterfully provides comic counterpoint to the action with dry jabs and a stubborn refusal to surrender an inch of her hard won peculiarities for anyone else’s satisfaction.

Echoing Chekhov’s rural comedies, the two younger women are dying to get out of this backwater, while Jeanne is doing what she can to keep the family together and to uphold tradition. As we will discover, she will do this even if it means crushing Louise’s spirit and allowing her to be subjected to physical violation. Thankfully, like Chekhov, the playwright gives us plenty of opportunity to laugh at the contortions the characters put themselves through to maintain their sanity in this stifling situation. The predicament becomes positively farcical at times. Louise carries on a playfully seductive phone conversation with her lover right in front of the family and guests. After she leaves, André (Jacques L’Heureux), one of the guests, ineptly tries to comfort Gaby by touching on all the horrible legal and emotional complications he will face after divorce — but hey, at least there won’t be a custody battle, Josée is 19.

André again exemplifies the absurdity of human behaviour when he describes how he overcame the grief of his first wife’s death by playing a few rounds of golf just hours after burying her. While the humour opens things up, and while we’re temporarily seduced by the hopes and dreams of these people, as with Chekhov’s country characters, this family is stuck in an evolutionary dead end. This may be where the symbolism of the snake comes in. After an excited Gabriel shows it off, it escapes, perhaps representing his last chance to save the marriage and/or the family’s last chance to save itself.

I was eventually drawn into the story, mainly on the strength of the acting ensemble, which handled the material effortlessly, tightening and slackening the tension with acrobatic precision. A colleague described Quebec actors as having that rare ability to shift from heightened emotional pitch to casual patter seamlessly. Jean-Denis Leduc, Artistic Director of the company, thinks it’s the result of a Latin culture (French speaking) transplanted to North America. Seems like a fair assessment.

In the tradition of his naturalist forefathers (with nods to plays like The Seagull and Miss Julie), playwright Dalpé serves up a melodramatic ending (something the naturalists were rarely able to resist despite themselves) that returns the family to a disturbing status quo. Despite the strengths of the acting ensemble and the subtle rhythms of the script, Aout borders on museum piece, a homage to a period when naturalism was a subversive theatre movement.

Sherry J Yoon, My Dad, My Dog, Boca del Lupo

Boca del Lupo’s new show My Dad, My Dog is an unusual convergence of animation and live theatre, and animator Jay White has talent to burn. The dog of the title is animated with spooky care. Its movement and timing speak of every dog I’ve ever known, although it looks like none I’ve ever seen. As it creeps into view from the bottom right of a huge screen placed upstage, it’s hard to believe it’s not real. A Korean woman (Sherry J Yoon) believes it may be the reincarnation of her father – this in a country where people eat dogmeat soup in the summer. Understandably, she’s feeling a little confused.

So am I. Although the dad-dog storyline continues to an inconsequential ending, other stories emerge and ramble about without apparent purpose. It doesn’t matter that the relationship between the woman and a slightly seedy pigeon smuggler (played with excellent timing and a submerged creepiness by John Fagan Tait) is never resolved. But there’s also a young Canadian filmmaker (Billy Marchenski) who may or may not be imprisoned in his North Korean hotel room by order of the autocratic Kim Jong Il. The filmmaker’s storyline peters out, as does the pigeon smuggler’s intention to study the rare cranes that have flourished in Korea’s demilitarized zone over the past 50 years. After narration and animation had spent several wonderful minutes building up to these magical cranes, I so wanted to hear more about them, and I missed them all the way to the end.

Animator Jay White stands stage left with the tools of his trade, and is a visible part of the action throughout. With his interventions, new scenes are often established by combining animation and live-action film. In front of a drawn backdrop projected onto the screen, White’s giant hand comes into view, setting out miniature pieces of furniture, where they appear full scale as set elements, but doll-house sized in relation to the hand of the artist.

At its best, the animation adds wonderful layers to the world of the play, literally. “I’m here for the birds,” the pigeon smuggler says as he sits outdoors with the woman. “So far I’ve only seen pigeons, but I’m optimistic.” And here comes a projection of the out-sized artist’s hand, holding a real magnifying glass. The glass reveals a miniature crane hidden in the painted foliage behind the couple.

In moments like these, the animation dominates the production, and it’s so good-natured and virtuosic that it temporarily blinds us to the fact that the overall aesthetic is fragmented. Scratchy black and white line drawings are mixed with full-colour, painterly scenes. Single animated elements trade places with panoramic views. The screen itself is often used to support the live action, but at other times it’s the actors who are helping to animate the screen. When the screen displays scenery, it maintains the focus on the foreground action. When the actors interact with animated images, their attention is directed upstage, emptying the playing area. At other times animation and actors are merged on one flat plane, as with silhouettes. And some moments are purely filmic, providing a sense of immensity in a small, black box theatre.

For some reason the narrator (Sherry J Yoon playing herself) feels compelled to interrupt this unusual world to tell us the dog’s a symbol, to teach us facts about North Korea, or to tell us what parts of the play were based on personal experience. The show’s creators are too aware of the information vacuum in our media on the subject of North Korea, and their concern for our education stilts the script. Without the narrator’s irritating presence, the play would have been almost twice as good.

Animation is laborious work, and the co-creators noted in a post-show talk that the “rhythms of animation and theatre are very different.” New plays in development are often being revised late in the production process; working with an animator would make that approach impossible. An 80-minute play represents a powerful amount of work for a single animator, and it may be that the needs of dramaturgy were overridden by the needs of animation. I still appreciate Boca del Lupo’s desire to try the partnership.

I absolutely loved this play for the first 20 minutes, and I’d see it again. But My Dad, My Dog has at least three unfinished stories, a constantly changing aesthetic, and an extraneous narrator. These post-modern embellishments weaken what would otherwise have been an absolutely captivating night at the theatre. The images are wonderful, but something’s gone awry when the strongest parts of a play are its scene changes. The variety of visual approaches could still triumph if the script were stronger, but with this script, the animation almost felt gimmicky at times. White’s obvious talent saves it from that. I left the theatre feeling oddly sad. This play had so much going for it, and a near miss can be devastating.

Sherry J Yoon, James Fagan Tait, My Dad, My Dog, Boca del Lupo

Directly framed by Sherry J Yoon’s straightforward announcements as herself to the audience, My Dad, My Dog presents a fragmented story about a Canadian woman of Korean descent (Yoon) imagining how one of her North Korean cousins might live. Yoon once had a dog who, she was convinced, was her reincarnated father. She wonders what her unknown North Korean cousin would do if she experienced the same thing.

Yoon appears as herself several times, emphasizing a (possibly false) truth-fiction distinction – “It’s not a real story, but every detail in it is true.” As the Korean cousin (all characters are unnamed), she presents a slide show about North Korean culture. A Canadian filmmaker (Billy Marchenski) worries that he’s been kidnapped; his monologues are rapid. Another Canadian, a professor (James Fagan Tait) who seems to have minimal knowledge of the birds he’s supposed to be studying, develops a flirtatious but awkward relationship with the Korean cousin by talking about his obssession with pigeons. Cuts from the original Godzilla backdrop the filmmaker’s thoughts about monster movies. Sound is mostly live: performers stand stage right by a microphone to provide voiceovers for hand-drawn animated scenes; Alicia Hansen plays gentle rills on an upright piano, stage right, silent movie style.

The play is a comedy, ranging from dreamy scenes of feeding (animated) pigeons to insightful comments on Kim Jong Il’s obssession with cinema to hilarious moments of non-communication sparked by differences in Canadian and Korean expectations. But it doesn’t find its focus in the story. The filmmaker overcomes the fear that he may be kidnapped and learns that he may be too presumptuous, but what does it mean to learn something so general about oneself? The pigeon-man remains a flat character whose role is to urge the Korean cousin to talk about herself. She becomes somewhat personal with him, but gives no specifics about who her father was, or why it would matter for her dad to appear as a dog. If that conversational distance is meant to reflect on opaque North Korean privacy habits, then the significance of the dad-dog needs to appear in another way. And the dad-dog, one of Jay White’s gentle, hand-drawn animations, doesn’t get enough stage time to become anything more than entertaining (there’s a great scene where the dad-dog confesses to another animated dog that he thinks the Korean woman has bad plans for him, but he can’t really tell because she keeps speaking English).

Because the storytelling style skips all over the place – the flow between scenes is almost, but not quite tight – the set and the layers of technical innovation take over and become the heart of the performance. In a high-tech culture increasingly devoted to all things digital, it is a pleasure to enter the well-crafted world of low-tech projections that White uses to create the whimsical set for My Dad, My Dog. White’s hand-drawn animations fill a movie-size screen, so images are large enough for the performers to walk around in or, suprisingly, for White to animate around the performers. In one scene, for example, White pans down an image of a tall elevator while a performer stands still. Elsewhere, the projection is set up so he can draw a backdrop live: as he sketches on a glass panel, the lines gradually form a restaurant and fellow patrons around the two performers sitting centre stage at a three-dimensional dining table.

The simple animation techniques are deft and playful, innovative in how they surround the performers. My Dad, My Dog is fun but ultimately remains sketchy, leaving the audience charmed by literal drawings instead of metaphorical ones.

Sherry J Yoon, James Fagan Tait, My Dad, My Dog, Boca del Lupo

What I write here doesn’t express my response to My Dad, My Dog. I’m just using it to explore my possible response, had I been watching a different show in another country, with other people. While it isn’t a true account of My Dad, My Dog, it is made up of details that are true…

It is with a similar postmodern bent that Sherry J Yoon introduces us to Boca del Lupo’s production of My Dad, My Dog, the story of her imagined North Korean doppelganger’s discovery of a dog she believes to be the reincarnation of her father. Through inventive interaction between animation, film and live performance, we witness her unfolding relationship with a man who likes pigeons (James Fagan Tait) and a filmmaker obsessed with monsters (Billy Marchenski). In an idiosyncratic exploration of how Yoon’s life might have been had she been born on the other side of her family tree in Korea rather than in Canada, we experience a sometimes witty, sometimes whimsical investigation into perspective and point of view.

Framed by the animator (Jay White) and his tools on one side of the bare stage, and the musician (Alicia Hansen) with her piano on the other, Yoon guides the naïve film-maker around the streets of her city, neatly stamping in a straight line as he trails in zigzags behind her. She is responsible for him during his stay in North Korea, and instructs what he may and may not photograph. He pans his camera towards the audience, looking for an image he wants to capture. On the large screen behind the actors, we see the rectangular frame of his viewfinder scan the landscape. The screen is white apart from the small frame, which reveals to us a continuous, beautifully painted watercolour image of the city. The filmmaker finds a view he is pleased with, and shoots; we are momentarily blinded by his flash. In this instant, the onscreen watercolour transforms to an actual photograph: several men, police or soldiers, are lined up carrying guns. Panicked, the guide snatches the camera and deletes this image, explaining that her charge must check that it is appropriate before he takes a shot. This is the least composed we’ve seen her: a momentary lack of restraint reveals the severity of the consequences if prohibited behaviour occurs under her watch. The filmmaker wavers over another couple of images and Yoon quickly points him towards more appropriate compositions. He finds a poster with a man’s face blown up to enormous proportions, presumably the President. Flash, and we see the photo. That’s right, says Yoon, you seem to be getting the hang of this.

Luckily for us, Boca del Lupo’s ability to portray differing perspectives on a narrative is not restricted. The cultural misunderstandings between Yoon and her newfound friend, the bird enthusiast, are touchingly comical. As they sit to eat, the animator draws efficiently simple lines onto glass, creating a restaurant around them. Yoon misreads the ornithologist’s emphatic concern about “the soup” and can’t understand why he struggles to bring himself to eat it. When it dawns on her that he believes that this is dog soup, an infamous Korean delicacy, to his embarrassment she laughs uncontrollably. When they first meet in the park, what she believes to be a polite smile in reaction to his invasive questions and attempts to test her personality, he reads as an Asian contempt for westerners.

By far the most entertaining perspectives on display are the conversations between animals, played out in animations which appear on the big screen while the actors provide voiceovers into a microphone downstage left. Two pigeons crossly discuss the fact that the crane, which gets so much attention, wouldn’t even be there if it wasn’t for the DMZ (Demilitarised Zone, a strip of heavily guarded, and therefore environmentally protected, land between North and South Korea). The dog that Yoon believes to be her father discusses his bewilderment at her behaviour with another stray: just one of the guys discussing his woman troubles with his buddy. Earlier we witnessed Yoon speaking to the dog, reaching out her hand towards his form on the screen as she thinks out loud about her father. The dog doesn’t know whether she wants to hurt him or love him. There’s one of a number of postmodern quips as his friend asks, “what did she say?” “Well that’s the thing, I have no idea – it was all in English!”.

Later on, the ornithologist’s huge face – actual not animated – looms over us, occupying the whole of the screen. He purses his lips, squeaks and clicks, and it becomes apparent that we are the pigeon that he has decided to smuggle back into Korea in his trousers, at the moment just before the sedative is administered. Later on, the filmmaker sets Yoon’s dog free and he scampers out of sight. We hear screeching brakes and a crash. The dog has been run over by a car. The camera is brought centre-stage and we see the three humans looking at it, while onscreen their sad faces look down on us.

With this clever layering we are shown that situations can be experienced differently depending on which perspective you approach them from, or which perspective you are permitted. Following the dog’s death, Yoon breaks out of character, relaxing her stiff body language and losing the almost robotic Korean inflections in her English. The dog’s death is the only detail of this story that isn’t true. It’s invented to create “a sense of convergence and closure.”

The three characters decide to write down their secrets and give them to the pigeon to carry away, in an act of remembrance. The ornithologist cups his hands, facing the screen, and as he opens them out the bird appears on the brown and green park landscape onscreen, flying away from us into the distance. The animation follows and eventually catches up with the bird, so we are given a literal bird’s eye view of the sea as it flies towards Canada. It passes a semi-submerged Godzilla, then approaches Vancouver, and finally a large white house. Just as we think we are safely home, another dog bounds into view, leaps past us and we hear a squeak and a crunch. A single feather drops to the floor. Through another viewfinder, the dog, mouth full, looks guiltily back at us, then jumps away towards a tree in the garden. The camera idly drifts up to the top of the tree. Then a screech of tires, a yelp, and a crash. The camera drops to the floor. Blackout.

Although the relentless postmodern frame of this show sometimes seems a little tired, it is often charmingly self-aware: this quirky twist is a beautifully crafted ending to the personal and cozy journey of My Dad, My Dog. And as for this article? The only detail of the review that doesn’t express my true response is the beginning…

Adrienne Wong, My Name is Rachel Corrie

photo Tim Matheson

Adrienne Wong, My Name is Rachel Corrie

The challenge any playwright faces is how to make their work robust enough to survive the potential vagaries of production. It requires making strong choices that will support a clear vision. Drawn from the writings of a young activist killed in Gaza, My Name is Rachel Corrie is far from a traditional play text. The process of turning Corrie’s journals and e-mails into a script is credited to the editors Alan Rickman and Kathleen Viner. Editing is an alien concept to theatre where the preferred term is dramaturgy, a process which includes an exploration of how the text will operate in performance. If Corrie’s voice survives this translation process, it is because of the performative quality of her journal writing and the chatty, informality of her e-mail style. Corrie was a gifted writer. Beautiful evoked images – salmon swimming underneath the streets of Olympia – alternate with affirmations that have Hemingway -ike economy: “I want this to stop”. Despite these strengths, this is fragile material that needs to be handled delicately.

The Havana is a small black box theatre located at the back of a restaurant on Vancouver’s eastside. It has never looked so gorgeous. The space has been completely cleared, with a single row of seating running around the four walls. Above the seating are wall-length rectangular projections. When the audience enters, cuttings from newspapers telling of Corrie’s death are projected. The texts overlap making them difficult to read. During the show, the projections are mostly colours and abstract designs until Corrie arrives in the Middle East, at which time we see photos of cityscapes and destruction. In the centre of the space a white square is boldly defined on the black floor. Within the square there is an office chair and an indefinable piece of ugly office furniture which acts as a table. The space looks futuristic and very tidy. Resting on the table is a white Mac Book computer, a model unavailable in 2003 when Corrie was killed; an early clue to the distancing artifice that informs the production.

The performer, Adrienne Wong, greets the audience as they come in, introducing herself to strangers. If she knows you, she greets you by name and spends a few moments catching up. When the show is ready to start, Wong goes to the entrance, where two more Mac Books glow stylishly in the darkness. She closes the door and does something with the laptops, giving the impression that she’s running the show with them. She makes her way to the performance space, takes off her shoes and then – accompanied by a suitable jet-like sound and lighting effect – steps onto the white square. She never leaves this claustrophobic space, except for one stylized moment where she follows a lighted path around the square. The rest of the time, Wong moves restlessly around the space engaging with the audience, making direct eye-contact.

It’s worth describing the production in this much detail. I will long remember the stylish presentation but not, alas, Corrie’s words. This is a production interested in the artifice of performance. The implication is that we should never believe Wong is Corrie and I never did. Rather, she is Wong performing Corrie’s words. Perhaps the producers, neworld and Teesri Duniya Theatre, were concerned about mimicry and felt this was a more sensitive approach to remembering Corrie. Unfortunately for me the artifice was simply too heavy. Wong’s entrapment within the white square is too distracting, even the projections take us too far from the words. This is not a traditional script with a coherent narrative structure that can support all the weight the production throws upon it. It is too fragile.

Wong is a charismatic performer who commands attention but even she struggles against the artifice. She gallops restlessly through the script at high speed. Perhaps this is meant to evoke Corrie’s youthful energy but it came across to me as a lack of faith in the material. It meant that her performance wasn’t as nuanced as it should have been and came off as too one-note. The one moment where things did slow down – an e-mail exchange between Corrie and her father – suddenly brought the production to life.

Corrie was a list maker and lists are featured repeatedly throughout the text. List-makers try to impose some form of order on a chaotic world. It is ironic that the over-determined nature of this production overwhelms Corrie. Her writings demonstrate the passion and emotion that drove her, yet this production generates a cool, intellectual distance. Perhaps this was a response to the controversy that has dogged this play (protests took place in New York and Toronto over the play’s sympathetic depiction of the Palestinians). While rationalism is laudable in the face of polarised debate, it seems untrue about what we know of Corrie. With the audience able to see each other, with Wong making direct eye-contact there is a form of calculated intimacy but it was with the performer and not the text or with Corrie herself.

Rachel Corrie was a vibrant individual seeking a role in the world and an identity that would suit her passions. Despite her strengths, her fragile body was too easily destroyed. I wish this production had relaxed its intellectual guard so that we could glimpse more of the fragile beauty of the script and the emotional power of Rachel’s story.

Sonia Beltran Napoles, Hey Girl!, Socìetas Raffaelo Sanzio

photo Peter Manninger

Sonia Beltran Napoles, Hey Girl!, Socìetas Raffaelo Sanzio

When the mob of twenty-odd men pounded the white girl and the floor around her with pillows, I was anxious. When the white girl held the chain of the person she had been forced to strip and purchase – the black girl in her prison irons – I was distressed. During the opening scene, I balanced between repulsion and fascination as a female form untangled herself slowly, jerkily, from a pile of oozing, pale pink slime that seemed abandoned on a laboratory table under a short-circuiting fluorescent light.

From the dripping slime to the silver, armour-like paint the white girl later slathers onto the black girl, Romeo Castellucci’s Hey Girl! is full of visual surprises and tensely sculpted stage space. Hey Girl! plunges us viscerally into women’s oppression, racial subjugation, betrayal and splintered willpower, using a few narrative fragments and a multitude of visuals, some illustrative, some opaque.

The best moments are both illustrative and opaque. For example, there are two oversized fake heads in the performance, both sculpted to look like the white girl. The heads appear close in time. After the white girl is beaten, she reappears from the line of now-still men wearing the artificial head and waving a huge black flag. She begs for the lights to go off. When the lights return, the head lies ‘decapitated,’ stage front: one of the many “queens who lost their head on account of the people” that the girl listed earlier on. For a moment, the head is simply illustrative.

Then there is female sobbing. The white girl walks gently through the crowd of men and brings forward the source of the cries: a black woman wearing an even larger version of the artificial head. So much for simplicity. When the white woman sees a version of her own face on another woman’s body, it’s a moment of total identification; it is also a moment where identification is cut. The white girl falsely comforts, apologizes, and beheads the white face from the black body. Then, although ashamed of herself, she joins in enslaving – or is she releasing – the black woman. There is similarity, there is difference; there is a shift of power from the white woman being a victim to the white woman victimizing; there is also a long list of words – all nouns – being projected above their heads. The interaction between the girls is so codified, and non-naturalistic, that any communication between them invites but resists interpretation.

Tension can be generated by presenting a highly codified scene and then asking the audience to decode with little assistance. This tactic flourishes in performance art, a genre that asks viewers to watch body-based action in a context made difficult either by long duration, physical discomfort or extreme content. Thinking about performance art helps me translate Hey Girl! because it specifically resonated with my experience of Marina Abramovic’s Lips of Thomas (1975, 2005). Naked, Abramovic alternates through a group of gestures aimed at exhausting her body so it can escape the heavy codes of Christianity and communism (Abramovic grew up in the former Yugoslavia and continues to use the name Yugoslavia for her homeland). She eats honey, whips herself on the back, lies on a cross of ice until numb, cuts a star into her belly, stands at attention in a pair of military boots and listens to a folk song, eats honey again. Because the actions and the timeframe are both extreme – the 2005 performance extended the original work from less than an hour to eight hours – the analytical mind can’t process what’s going on until later. If authority pushes the bodies it manipulates to total exhaustion, then authority collapses from the lack of having something to control.

Hey Girl! similarly works to shatter symbols by presenting bodies and structures on the edge of physical damage and exhaustion. Bodies on stage are in pain, at least if they’re female. The girls are buried, shackled, beaten, traded, but also capable of wielding a sword or joylessly dancing. Viewers’ bodies are affected: the viscous pink material is palpably revolting; we endure the acrid smells of lipstick, perfume and fabric burned against a flagrantly phallic hot metal sword. When at last the patriarchal, colonial gaze, represented quite literally by four suspended lenses that hang between the white girl and the shackled black girl, snaps, only then can a new code be written, though it initially involves dancing around the shattered glass left from the previous hierarchies.

Hey Girl! is theatre, though, not performance art. It’s theatre that asks us to move into an understanding with our gut more than with our mind. Canadian actor and writer Darren O’Donnell once said, “What theatre is really about – like any other form – is generating affect, and that’s it. Feelings. And, if things go well, quickly following feelings will be thoughts. Stories certainly can do this, but they’re not the only thing to do it, and they’re no longer always the best way to do it” (Social Acupuncture, 2006). Castellucci aims at our affect directly. As Hey Girl! evolves, visuals that seem iconic become messy and harsh moments are tempered by sudden kindnesses. This complexity means that, afterwards, images continue to shift and morph, playing with the mind and maybe never yielding a stable response. It’s an effective way to go into culturally familiar stories about women surviving violence because it provokes authentic feelings around gender and race.

Sonia Beltran Napoles, Hey Girl!, Socìetas Raffaelo Sanzio

photo Raffaelli

Sonia Beltran Napoles, Hey Girl!, Socìetas Raffaelo Sanzio

Romeo Castellucci’s new work Hey Girl! contains many effects that aren’t really allowed in the theatre. Normally you don’t burn perfume because you’d get stuck with a huge bill for dry-cleaning the blacks afterwards. Normally you’re not really encouraged to shatter circles of glass onstage. It’s definitely considered inappropriate to drip gloopy substances all over the floor. Castellucci strips the stage back to a bare working space to protect the theatre (from himself), and gives us a painting instead.

Visual elements drive the work from moment to moment. Precisely focussed lights pick out the next object that will shape the action – a sword, a drum, a man watching. Careful staging draws our eye to each new tableau as if to a specific point on the canvas. Spoken text is rare, and always whispered, so as not to impinge on this dreamy, fog-laden visual world. Even the main character, the iconic Girl of the title (Sylvia Costa), is an image resolving out of an abandoned, amorphous glob of thick paint left heaped on a table. The skin-tone paint she emerges from never stops dripping onto the floor during the whole mesmerizing length of the work.

This is a polyptych – a many-panelled work of art, imprecisely seen through the smoke of ages, like the dust that collects on an old painting. On this panel, over here, is the bird that can no longer fly, and the violent crowd. On this panel is the other side of the Girl, the dark half who is enslaved to a man. On another panel is a newborn woman, weeping. Castellucci places the Girl stage front, listening to the brutal light of the Divine – in this case a laser beam. He shows us the Girl comforting herself in the person of another woman who bears an enlarged copy of the Girl’s head. In creating these moments, he’s suggesting what an allegorical painting would look like, if it came to life before us in three dimensions.

The challenge with allegorical painting – more typically a product of the Renaissance – is that the modern audience is out of practice reading the symbols. Castellucci has updated the images, but some mystery remains. How literal is the reading intended to be, and how much reading should we do?

The girl kneels before a large, metal sword. Slowly, exquisitely slowly, she reaches across and picks up a lipstick case I didn’t notice until just before her hand touched it. She puts the lipstick on. Then she places it on the sword and smoke rises. Reaching over to a bottle of perfume, she draws the scent onto her skin with a throat-slitting gesture. Poured over the sword, the perfume steams and sizzles and the theatre fills with a hot fragrance. The Girl soothes the angry sword with a folded pink sheet and recites the names of dead queens. Marie Antoinette. Ann Boleyn. The Russian Tsarina. She lifts the burning blanket and unfolds it, a dark brown X revealed, newly branded. “These are the queens who lost their head on account of the people,” she whispers.

A bald description of the Girl’s gestures does not convey the ritual power contained in each tableau. The impulse is to search for meaning, although following that impulse feels like an inadequate approach to the work. Certainly, there are multiple ways the scene above could be read. Most obviously, the lipstick and perfume signify the queens of history, the women with power who were destroyed by men. Alternatively, these are symbols of femininity that at various times have been rejected as disempowering. There are other possibilities, but the actual interpretation may be less important than the attempt to interpret. The pace of the piece is ritualistically slow, giving plenty of time for conjecture.

Hey Girl! is an extremely unusual work by a director with that rarest of qualities – a unique vision. It’s exactly the kind of work I hope to see at Vancouver’s PuSh Festival, which aims to present the best of contemporary work, including more risky and challenging pieces. It’s not like anything I’ve seen before outside the visual arts, and Hey Girl! makes me realize how much room there is to develop the images of live theatre. Castellucci expands our ability to read those images in places we never expected to see them. But he also creates a world in which humans move through a landscape full of symbols without ever trying to interpret them at all. Maybe that’s what we’re doing every day, but the layer of paint he applies allows us to see it for the first time.

Nigel Charnok, Fever

photo Th. Ammerpohl

Nigel Charnok, Fever

If fever can bring on delirium, it can also loosen a person from the usual constraints of decorum and let unspoken truths tumble out. UK dancer/performer Nigel Charnock creates an atmosphere of excited passion from start to finish in Fever by interspersing mad, large-scale movements with pseudo gentle moments. He’ll rush about with sweeping arm movements and scissor-leg high-kicks, sprint up and down the theatre stairs, throw himself on the musicians’ speakers – and then sit in an empty audience seat to join us listening to “the beautiful music; isn’t it like Schubert?” Charnock speaks physical gesture so fluidly that he can improvise hilariously cutting monologues about fundamental human obssessions without dropping his focus on movement.

Fever is a structured improvisation for Charnock and for the musicians, the two-cello, two-violin Virus String Quartet led by Michael Riessler on bass and tenor saxophones and clarinet. Originally inspired by Shakespeare’s love sonnets which Charnock speaks in part or whole but, as the program points out, every night is a new possibility. “Nigel Charnock will present a personal selection of Shakespeare’s Sonnets, possibly: No. 18, 34, 16….” The musicians, for their part, satirize minimalist music, quote Purcell, send Charnock “shut it!” messages by increasing the volume when he teases by dancing erotically close to one cellist.

Nothing is safe from Charnock’s rant. This realization keeps the audience happily on edge, grinning in anticipation. It also creates a performance-long link of trust – we like this guy – so we’re willing to consider at least temporarily a comparison between a Catholic’s fear of passion (familiar satirical territory) and a burqua-clad woman’s view of the world “through a letterbox” (uncomfortable satirical territory). Charnock mocks everything, including his dance training and his (eventually) bare legs, so when he does get serious, we believe him. He ends the show with an orgasmic “death,” clenching the microphone stand in response to Riessler’s agitated clarinet solo played over his writhing body. The Vancouver crowd, for once, let silence sit for several seconds before applauding.

It’s remarkable that Charnock and Riessler have been performing Fever for a decade. The show stays fresh because the structure includes space for commentary on current events (the night I saw it, Charnock referenced current events like Canada’s presence in Afghanistan; another night he mourned Lady Di) and because Charnock and the musicians perform the piece wholeheartedly. The performers use their intimate knowledge of the material to bend phrases and treat everything with irreverent playfulness, knowing they will all meet up again at particular points and on cue. Charnock has a long, accomplished career behind him; successes include a commission to make Stupid Men for the Venice Biennale in 2007. Looking across from Fever to his later works, it’s clear that this rambunctious performer obssesses about death, religion and sex. But then, don’t we all, and he does it with irresistible hilarity and polish.

Adrienne Wong, My Name is Rachel Corrie

photo Itai Erdal

Adrienne Wong, My Name is Rachel Corrie

The slight young woman’s intelligent eyes lock onto mine as she perches on her upholstered white office chair, knees drawn up to her chest. I feel as though she and I are alone in the room as she tells me how, when she was younger, her mother told her that she thought she might be a better mom if she took her children to church. “This may have been a scare tactic.” The audience’s laughter snaps my connection with Wong and she swivels on her chair to address the person next to me.

Wong, who has introduced herself to each audience member personally as we entered the tiny blackbox space, is speaking the monologue edited by Alan Rickman and Katherine Viner from the diaries, emails and letters of Rachel Corrie following her death in Rafah, Gaza in 2003. The audience are probably aware of the circumstances of Corrie’s death: while protesting about the demolition of Palestinian homes, she was crushed by an armoured bulldozer operated by the Israel Defense Forces. But this performance allows us to get to know the woman behind the newsprint, extracts of which are projected in thin strips on each wall of the Havana Theatre as we enter.

The intimate, in-the-round setting of Wong’s performance painfully draws attention to her physicality in the space just a metre or two away from us. Four single lines of, at most, fifteen chairs form a square around the performance area; I can see the expression of every person present. Through Wong’s energetic portrayal of the powerfully evocative words of Corrie as a girl, we are invited right into her messy teenager’s bedroom and inner thoughts, witnessing her childish self-absorption, but ever-present sense of justice and engagement with the world. Through the strength of her writing, helped along with images projected above each line of seats, the space transforms from the world of her childhood and education in Olympia, Washington, to an aeroplane journey to Gaza, to check points outside of Rafah, and the base there for Corrie’s work with the International Solidarity Movement.

Wong jumps from chair to floor, she pushes her desk around the space, her boundless energy brims out of her small frame, threatening to spill onto the audience. She paces round the perimeter of her square of light, making lists, ordering her quick-firing thoughts. “What I have: thighs, a throat and a belly. Sharp teeth and beady eyes.” This witty attention to her corporeality and the horrible irony of her perceptive words as a 12 year old are incredibly moving: “It’s all relative anyway; nine years is as long as 40 years depending on how long you’ve lived.” We learn the motivations behind her activism, her desire to see what is at the other end of the spending of American taxpayer’s money, and her sense of guilt that she can leave the Middle East whenever she wants, but that the local people who have “sweetly doted on [her]” have no escape from their afflictions. The monologue is given a sense of conversation as we hear extracts from her worried parents’ emails: “There is a lot in my heart but I am having trouble with the words. Be safe, be well. Do you think about coming home? Because of the war and all? I know probably not, but I hope you feel it would be okay if you did.”

But at moments the dense text heads towards information overload and Wong’s unwavering energy feels monotonous. I alter my focus onto the audience directly opposite me. Some seem entirely engaged, others shuffle and accidentally make eye contact with me. It’s difficult to digest this vibrant stream of thought without any downtime. At one point my mind wanders onto why this show has previously provoked so much controversy in North America, with performances cancelled in New York for fear of offending Jewish audiences. The performance doesn’t claim to be anything other than an individual’s subjective thoughts about the Israeli-Palestinian situation; Corrie’s naivety is not disguised. We see that this is someone learning, changing, and scared as she starts to question herself and her “fundamental belief in the goodness of human nature”.

In an article for the Guardian, Katherine Viner states that she and Rickman “chose Rachel’s words rather than those of the thousands of Palestinian or Israeli victims because of the quality and accessibility of the writing.” To me it seems that in using an outsider’s perspective on the situation in Gaza, Viner and Rickman not only create a route into these complex issues with which Western audiences might better be able to identify and therefore begin to think actively about the Palestinian/Israeli conflict, but they also avoid a reductionist “taking of sides”.

Wong’s animated outpour finally pauses. “Rachel Corrie died on the 16th of March, 2003.” She puts on a bright fluorescent orange jacket. Standing still, she switches on two TV monitors in opposite corners of the room. We crane our necks to see a fellow activist’s hurried and emotional account of Corrie’s death. The reality of his fear and adrenalin rush hits me hard in the stomach. Wong then turns over a panel on her desk which reveals a miniature landscape, a tiny version of the place Corrie died. Another video is projected onto the walls above: Rachel Corrie as a child is making an impassioned speech about how we can “solve hunger by the year 2000” if we work together, how a bright future where everyone’s human rights are respected is possible. As the onscreen audience applaud the small blonde child, Adrienne Wong joins in. Stunned, we follow.

During the show I was overwhelmed by the mass of information being propelled at me. But I’m still thinking, still running her words through my mind. I read my notes and Guardian reports on the incident of her death, trying to gather as much information as I can about the context for My Name is Rachel Corrie. If its aim has been to make us think, to spark interest and encourage discussion about the issues it introduced, it has succeeded. Whether the show will provoke action and involvement on the global scale that Corrie envisaged as a child, or even on the individual scale that she worked on in Rafah, is another—disheartening—question.

neworldtheatre & Teesri Duniya Theatre, My Name is Rachel Corrie, taken from the writings of Rachel Corrie edited by Alan Rickman and Katherine Viner, director Sarah Garton Stanley, performer Adrienne Wong, collaborating director Marcus Youssef, designer Ana Cappelluto, lighting Itai Erdal, sound Peter Cerone, video Candelario Andrade, sound/video systems Jesse Ash; Havana Theatre, Jan 24-Feb 2; PuSh International Festival of Performing Arts, Jan 16 – Feb 3

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 10

© Eleanor Hadley Kershaw; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Adrienne Wong, My Name is Rachel Corrie

photo Tim Matheson

Adrienne Wong, My Name is Rachel Corrie

The actor shakes every person’s hand as they walk into the small, square Havana Theatre. “Hi, I’m Adrienne Wong.” The gesture invites you personally and a few minutes later, when Wong launches into My Name Is Rachel Corrie, you realize she’s set up an intimacy that she’ll develop as the play unfolds.

In fact Teesri Duniya Theatre (Montreal) and neworld theatre (Vancouver) have taken care to build intimacy into every part of the show. The performance is in the round but there’s only one row of about twelve seats along each wall, so every sight line is direct. The set is functional: a thickly upholstered white office chair and a skinny white one-legged table, both on wheels, a white laptop computer, and a white square of light projected onto a white vinyl square taped to the floor. Narrow horizontal screens hang above each row of chairs; the initial projection is a collage of headlines about the death of the young American peace activist killed in Gaza in 2003 along with excerpts from her emails. It’s all pared down and it’s all around you all the time.

Pacing the stage, or swirling in the chair, Wong swivels every minute or so to address all of the audience. At some point she will look at you, and you know she’ll do it again. It’s not invasive, it’s engaging, and it brought me into the story almost as if it was a conversation.

Directness shapes the evening profoundly. The play is constructed from Corrie’s metaphor-filled, descriptive emails and letters (compiled by UK actor Alan Rickman and Guardian journalist Katharine Viner in 2004-05). Corrie was a skilled, nimble writer but the words were originally meant to be read, not spoken. Wong’s eye-contact and restless movements give them a convincing physicality. And the straightforward, person-to-person approach cuts through the thick layer of controversy that surrounds this work – polarized opinions, cancelled productions in New York and Toronto, and the difficult facts about Corrie’s death and Gaza Palestinians’ ongoing lack of reliable access to water, housing and food. When Wong/Corrie looks right at you, the question is: what do you feel, what do you think? It’s a powerful way to handle what has become such a locked-down story.

And this is what usually gets lost in debate about this play. A substantial chunk of it is about Corrie as a person. We meet her as a pre-teen, then in high school, then college, before she feels the pull to try and understand personally a complicated part of the world. Her young voice is endearing and funny. One day she goes for a walk in the forest and sings Russian drinking songs to the trees. She describes walking home late at night in “slutty boots” thinking about the salmon who, thanks to modern city life, have to swim back to their birthplace through culverts since that’s where the streams are now diverted. “It’s hard to be extraordinarily vacuous when you always have salmon in the back of your mind.” These are simple, almost innocent thoughts that show a mind growing.

The play reveals the context of Corrie’s activism. As she learns, organizes and joins events, like walking down the street with forty other people dressed as white doves, her voice alters. She wants to know what happens on the other end of US tax dollars in places where that massive military budget is being spent. She’s angry but humble. After she arrives in Gaza, to work with the International Solidarity Movement to watchdog against events like water wells and greenhouses being bulldozed, she retains that sense of probing. She never sets herself up as an expert: “I am new to speaking about the Israel-Palestine conflict so I don’t always understand the political implications of what I am saying.” She’s just a person trying to figure out what’s going on. She notices glow-in-the-dark stars in blown-out bedrooms; she’s disturbed when closed checkpoints prevent Palestinian workers from going to, or returning from, their jobs. The play doesn’t become didactic; it offers information and opinion, and asks us to form our own thoughts.

Wisely, Corrie’s death is not enacted. Completing her moments as Corrie, Wong puts on a bright orange safety jacket, reads aloud her last email to her mother (about two men offering her a meal), and steps off stage. A moment later, she takes off the jacket and activates two small-screen videos in which a young man describes how the bulldozer moved toward, then over, Corrie. It’s the right amount of detail: facts are involved here, and no one pretends to know them all.

My Name Is Rachel Corrie is a story about how a person grows to look outside her own life and tries to grapple with huge, traumatizing events that she knows she can walk away from at any given moment, even though the people living there can’t. Corrie’s convictions about justice, compassion and activism led her to Palestine, but those beliefs can be applied to other injustices in the world. Journalists, activists, immigrants and others in areas torn by military conflict talk about having to make difficult choices on a regular, sometimes daily basis. Can the rest of us learn from their experiences, or are they too distinct from ours? And, thinking of Corrie’s death specifically, aren’t there any insights from her story that reach beyond the specifics of the Israel-Palestine conflict?

Like the square of light that widened and shrank around Wong as she moved through expansive or frightened, tightened moods, the play can open out or close down our ideas if we are willing to take that first handshake for what I think it was: an invitation to hear one real person tell another real person’s story, respecting us, too, as individuals with so much to learn.