Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

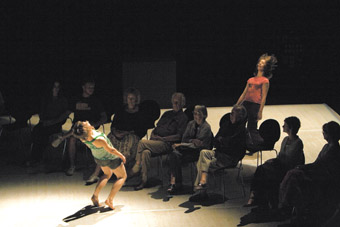

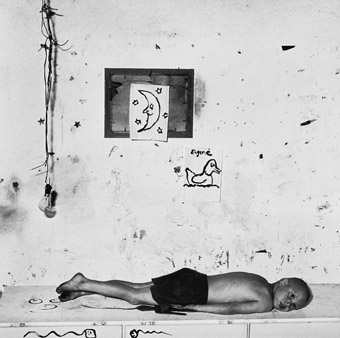

Small Metal Objects

photo Jeff Busby

Small Metal Objects

Small Metal Objects is about a drug-deal that goes wrong. Like any good gangster flick, it’s really about shifting power dynamics. What sets Australia’s Back to Back Theatre production apart from any gangster movie you’ve ever seen is that the drug-dealers are “mentally-challenged”, putting them even further outside the mainstream than your stereotypical dealer.

Thinking about it, a mentally challenged dealer, being largely invisible to the public would have a huge advantage over his competitors. The notion of visibility/invisibility is a key theme in Small Metal Objects. Ironically, when you eventually see the dealers, Gary and Steve, it is hard to think of two less invisible individuals. Gary is large with bleached hair and, to top it off, is played by a woman (Sonia Teuben); Steve (Simon Laherty) is small and thin. Seen from a distance, they make an intriguing odd couple with Gary providing protective gravity for Steve who looks as if a strong gust of wind might carry him away.

If Gary and Steve are outsiders, their customers couldn’t be further on the inside. Attractive and power-dressed Alan [Jim Russell is a lawyer, while Carolyn [Caroline Lee] is a corporate consultant of bundled sexuality. Their striding sense of command is unmistakable and highly visible. Alan is trying to score drugs for a large function scheduled for that evening. When the deal starts to unravel because of an ‘existential’ crisis being experienced by Steve, Alan calls in Carolyn, an expert in change management, to negotiate with the dealers and try to get through to Steve. At the core of this scenario is a delicious irony. The in-control insiders are looking to alter their mental state in order to enjoy some form of escape or even loss of control. The key to realising this altered state rests with two individuals who must confront mental issues dictated not by manufactured chemicals but by nature, something not lost on the observer of this performance.

I use the term observer advisedly. For the impact of Small Metal Objects is directly related to how the audience experiences the show. In a very special form of invisible theatre, the performance takes place in a public space—in this case, the vast atrium of Vancouver’s iconic Central Library. The actors wear small head microphones and move freely through the crowds who are generally oblivious to what’s going on. If the public notice anything, it’s the audience sitting on a raised platform, wearing headphones—so they can listen in on the performers. By these means the production neatly and effectively plays with notions of visibility and invisibility. One couldn’t help noticing the general obliviousness of the majority of people passing directly through the ‘performance space.’ Or how many in our city look like they should either be on the heath with Lear or in Waiting for Godot.

The show commence with a discussion heard through our headphones. The voices are disconnected from the setting; we have no idea who in the milling crowds is actually speaking. It’s interesting to watch the audience as they scan the atrium, looking for the performers. At first I surrender to the idea that we are meant to experience the voices this way, like an overheard conversation between unseen diners in a restaurant. But still the impulse to locate the performers is too strong and finally I spot two men sitting at a table outside a pizza place and focus my attention on them. The voices seem to match up with the movements of their heads. Suddenly my attention shifts. There, moving slowly into the centre of the space, are Gary and Steve. It’s as if they’ve come out of nowhere. The invisible made visible.

A slow, melodic piano score punctuates the dialogue. We gradually gather information about the speakers from the unusual directness and candour of their exchange. Gary, is married and has a family that he would protect at all costs, while Steve is single and worries that he might be gay because he hasn’t got a girlfriend. By the time I finally spot the performers, their exchange has built to a dialogue about dependency. Gary is going into hospital and is worried that Steve is going to be left alone, claiming his friend relies on him for everything.

Then the phone rings and Gary answers. It’s Alan speaking the international code of drug-speak, wanting to set up a deal. Gary’s response to Alan has such a fantastic, child-like blankness that you’re sure there’s been a mistake. Gary even calls out to Steve, “Do we know an Alan?” Long pause. “No”, answers Steve. But there hasn’t been a mistake and Gary finally agrees to meet Alan. The deal goes wrong when Steve, frozen with panic by Gary’s impending hospitalisation and other anxieties, refuses to accompany them to where the gear is kept. If Steve won’t go, neither will Gary. The deal is off. Steve refuses to move because he is deep in thought; he needs to understand something profound. The impact of his conversation with Gary is still resonating. In a performance of remarkable stillness, Laherty remains rooted to one spot for almost the balance of the show, while Gary, Alan and eventually Carolyn circle around him.

Nothing will persuade Steve to give in. Not more money or Carolyn’s offer to improve him or even the promise of a sucked dick. This is when the shift of the power-dynamic is most apparent. Steve considers Carolyn’s offer but still refuses. The phrase “small metal objects” refers to money and the production explores where and how we put value on things and people. Alan and Carolyn’s impatience with the dealers is palpable and their ability to quickly increase their offers through terms that they understand—money, social acceptance and ultimately sex—do not work with Steve or, because of his undying loyalty to his friend, Gary. However, Small Metal Objects is far more subtle and beautiful than this simple decoding can possibly express. It is also more than the cathartic experience of watching loveable outsiders triumphing over the powerful. Many times during the show Gary and Steve express a simple, beautiful logic that reminded me of the questions that children might ask. Questions which show a profound understanding of basic truths but which do not take into account the perceived difficulties that society imposes upon us. Just as we are often unable to answer the questions of children, Alan and Carolyn cannot fathom the dealers they have been forced to deal with.

The show is also about control and a sense of self set against the swirling demands and expectations of our world. I actually went to the library during a subsequent performance. After dropping off my overdue books, I looked back and saw Laherty perfectly framed in the wide rectangular doorway to the library: a vision of perfect, thoughtful stillness set against the oblivious and unseeing crowds. It was a striking image that will remain with me forever.

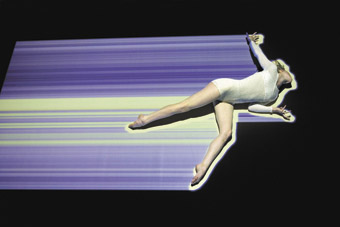

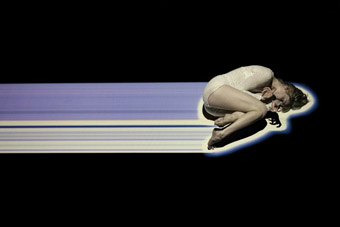

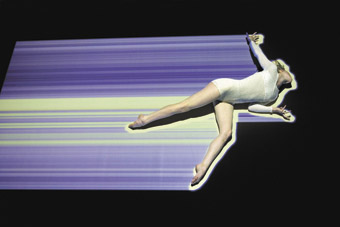

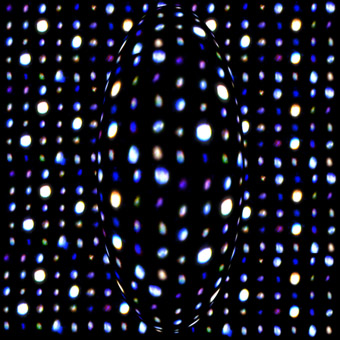

Kristy Ayre, glow, Chunky Move

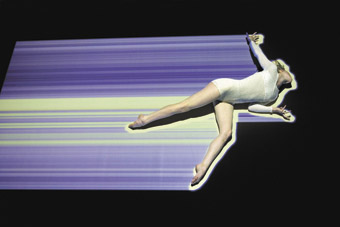

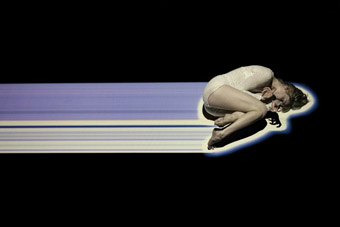

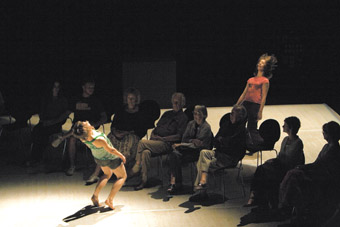

Glow by Chunky Move explores of the most basic definition of physical existence: that we are simply organisms powered by electricity. Not unlike a television documentary, Glow follows the life cycle of an organism from emergence into an environment through to its death. The focus of this exploration is the energy that drives the organism and the impact this energy has on its environment.

The environment itself is simple: a glowing, white floor that the dancer moves across. Much of the work is floor-based and the key relationship is between the performer and the white space that darkens below us during the performance. Using a video tracking system developed by German computer artist Frieder Weiss, a form of digital landscape is created on the floor-screen that responds to the movements of the performer. These are not pre-programmed effects but rather respond in real time to the performer’s movements as choreographed by Gideon Obarzanek, director of Australia’s Chunky Move dance company.

For the most part, these are stripped down and stark lighting effects, dominated by white lines and shapes that move across the floor. When the performer first arrives, she crawls across the darkened floor like some an ancient, crab-like creature emerging from the seas. Her body is at the point where a horizontal and a vertical line intersect, giving a sense that the performer is somehow targeted in the scope of a sharp-shooter. On other occasions, the dancer’s body is outlined by a white line that the performer moves and shapes as if pushing from within an electric womb. In a particularly striking sequence, the performer lies in a foetal position, as if asleep, while white lines of varying thickness radiate from her body and race across the floor. It is as if we are seeing the energy seeping out of her into the environment. Although her body is at rest a sense of movement is created. This moment and others where an electric field is created around the performer’s body put me in mind of the aura that an electrically charged creature must give off.

The production is more than a light show and the sheer physical presence of the performer is vital. There are passages where she sensually crawls across the space, making eye contact with the audience and momentarily taking the experience out of the abstract where most of the production resides. These moments of focused attention on the performer’s body are accentuated by a decrease in the volume of the scoundscape and we are able to hear her movements on the floor. There are also moments where the performer vocalizes. While these are less successful, they do remind us of the organic, living creature that is, after all, the subject of this ‘documentary.’

By tracking the performer through light, we are able to see the impact her body has on time and space. There are sequences where the projections are delayed slightly, giving the impression that the floor is holding the memory of the dancer’s movements. This is used to greatest effect towards the end of the show, when the movements are held as black, organically rounded shapes. These shadows move of their own accord across the floor—the first time that the images take on a life of their own. Like strange cancers, the shapes move towards the performer who remains standing and perfectly still. The music builds, a touch melodramatically but effectively, and ends with a loud discordant sound as the shapes seem to re-enter the dancer’s body. The organism is entering the last cycle of life.

Glow ends with the dancer again lying on the floor with what looks like an electrical charge pulsing around her body. Although death is clearly implied, it is a strangely energetic moment. It is as if her energy were being released from her body back out into the universe—or more correctly being absorbed back into the ground where it originated. The dancer then stands in one corner of the space. In the centre of the floor, a grey dot flares, reminiscent of an old television being turned off, a lovely touch evoking an earlier form of technology while giving a sense of the life cycle ‘documentary’ coming to a close. Finally, a last charge of grey crosses the surface of the floor: the screen is dead, the energy gone.

–

Chunky Move, Glow, concept, choreography Gideon Obarzanek, performers Kristy Ayre, Sara Black, concept, interactive system design Fried Weiss, music & sound design Luke Smiles (motion laboratories), additional music Ben Frost, costume designer Paula Levis; Scotiabank Dance Centre, Vancouver, Jan 31-Feb 2; PuSh International Festival of Performing Arts, Jan 16 – Feb 3

Andrew Templeton is Vancouver-based writer and playwright who’s had plays produced in Vancouver and London.

© Andrew Templeton; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

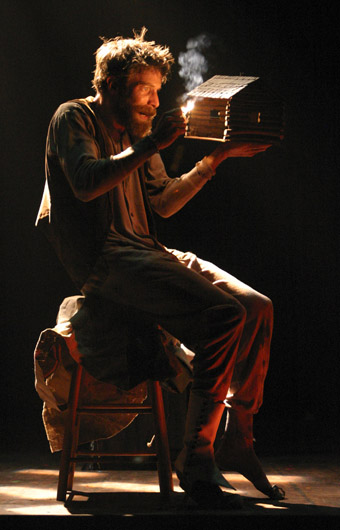

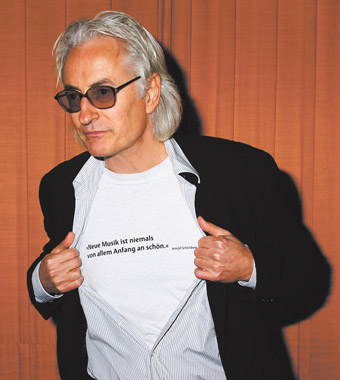

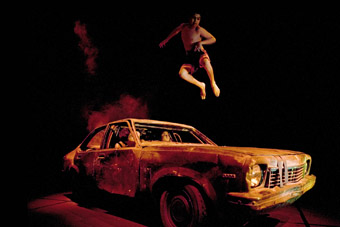

Jonathan Young, Palace Grand

photo Tim Matheson

Jonathan Young, Palace Grand

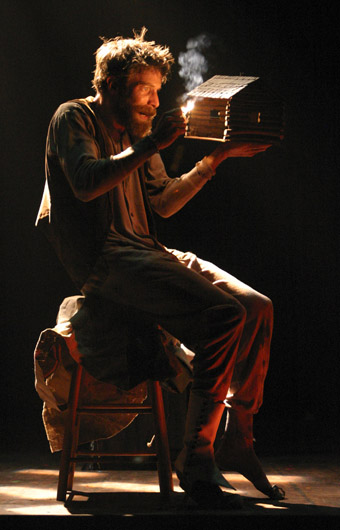

Palace Grand ends with an image that would make an effective gallery installation. We look into the interior of a wood cabin where a man, wrapped tightly in a sleeping bag, lies stretched out on the floor like a corpse. Through a window above the body, we sense the desolate, killing beauty of the North. This wooden cabin is the Palace Grand—or, more correctly—the Palace Grand exists inside the man, the central character of this piece.

I don’t think Jonathan Young, the creator of the work and its sole performer, or his colleagues at Electric Company would mind too much that I gave away the ending. If Palace Grand were a murder mystery—a genre it evokes—it would fall into the how-he-done-it rather than who-done-it category. It is clear early on that the two central characters, Walker and Tracker, are really one and the same person and that the driving force of the piece is seeing how the two halves will come together, what will happen when they finally meet at the Palace Grand.

Of course they never formally meet but are brought together for that final, haunting image. The majority of the production details the individual but inter-connected journeys of the two. First is Walker who in the late 19th century travels to the far north of Canada, to Lousetown with intentions of taking over an abandoned mining claim. I think this is the back-story although the fractured manner of the storytelling means that it is sometimes difficult to follow. The key thing to know about Walker is that he’s trapped in a cabin in winter and seeking solace in writing, the only way left for him to impose order on the world while suffering the worst case of cabin fever—ever. The second narrative strand follows Tracker, who has taken on a commission from an anonymous source to hunt down Walker. Tracker carries with him an old fashioned recording device and also relays his findings to a third character, an operator at a remote exchange who forms a sort of analogue to audience.

Associations to do with writing and transmission are central to Palace Grand. Walker never speaks; instead we see his writing projected across a black scrim that frames the playing spaces. This writing is accompanied by the sound of a scratching pen. Except for one pivotal sequence when he arrives at the Palace Grand, Tracker also never speaks; instead Young mimes to a pre-recorded voiceover. Young is a tremendous physical performer and realises the full comic potential of this conceit while—on the other side of the narrative coin—wordlessly evoking the madness and loneliness that grips Walker. My sense is that neither Walker or Tracker—nor the operator for that matter—are ‘real’ but instead are creations of the body we see at the end of the work. In this way, Palace Grand is about the unreliable narrator. Is the body at the end meant to be Walker or is it a third (really a fourth) character? Is this ‘narrator’ from the 19th century or is the whole set up merely a fabrication—a 21st century imagining of a 19th century story? As Walker’s words keep reminding us, don’t trust what you read.

Who, then, is the ‘story’ about? I suspect it is about Young himself. Palace Grand seems a meditation on the dual and inter-related processes of creation (Walker) and performance (Tracker) that go into producing theatre. In a very postmodern conceit, the work is really about the work itself. In previous productions, Brilliant and Studies in Motion, the Electric Company explored the relationship between eccentric geniuses and technology, Nikola Tesla and Eadweard Muybridge respectively. In its own way, Palace Grand is a companion piece to those works. Instead of electricity or photography, it is about Young’s relationship to the creation and use of the machinery and artifice of theatre. This sense of theatrical artifice informs the production in the rigorous and beautiful manner that we have come to expect from the Electric Company.

The playing space is divided into a series of cramped boxes that look as if they’ve been carved out of the darkness. The square playing spaces echo not only the stage of theatre but also the cabin window we see at the end. The boxes are connected by a rabbit warren of tunnels that Young moves through deftly. There are also wonderfully inventive moments, including a rocking chair that turns into a sled pulled by a stuffed dog and a small steamer ship with a puff of cotton wool coming out of the smoke-stack. As in all Electric Company productions, this low tech stage-magic is offset by high-tech projections.

When Tracker finally arrives at the cabin in Lousetown, he doesn’t discover Walker but instead finds himself—or is it Young—on the stage of the Palace Grand, a vaudeville theatre, the kind you might find in a Gold Rush town. For the first time, the performer speaks instead of miming to his own voice and there is a moment of vulnerable confusion as Tracker tries to understand what is happening to him. As the curtain behind him draws back he finds not the expected audience but a pair of mechanical hands clapping eerily. His hunt for Walker is not over. He descends into another box, below the main playing space. This is perhaps the abandoned mine shaft that exists below the cabin itself. We are then treated to a series of images of struggle, the most effective being Walker/Tracker/Young climbing up a ladder towards the audience as if emerging from a mine-shaft. I wish the production had ended with this image. It had a powerful sense of a real person emerging from darkness—from the depths of insanity. However, like a Hollywood movie there are a couple of false endings, including finding the pages of Walker’s manuscript stuffed in a sleeping bag, before we get to the final image of the body lying on the cabin floor.

Electric Company, Palace Grand, writer, performer, set designer Jonathan Young, director Kevin Kerr, lighting and set designer John Webber, video designer David Hudgins, additional video Jamie Nesbitt, properties design Rick Holloway, additional properties Stephan Bircher, sound design Kevin Kerr, Meg Roe, Allessandro Juliani, movement Serge Bennathan, costume design Kirsten McGhie, scenic painter Marianne Otterstom, technical director Harry Vanderschee; Waterfront Theatre, Vancouver, Jan 30-Feb 2; PuSh International Festival of Performing Arts, Jan 16 – Feb 3

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 11

© Andrew Templeton; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

A tall shifty man in a white shirt and long black jacket approaches a passerby in the covered area of Vancouver Public Library’s central promenade. “Gary?” “Er, no.” “Oh, sorry.” He crosses the promenade and approaches another man sitting alone outside one of the coffee shops by the paved walkway. “Are you Gary?” A bemused no. “Oh right, thanks.” The tall man looks around frantically. He spots another man alone, leaning on the balcony overlooking the glass-fronted library. He crosses the busy promenade. People bustle by with shopping bags and plastic coffee cups. Hesitantly, he asks again, “Are you Gary?” “Yeh.” Although we’re looking from quite a distance, I’m certain that I see a barely perceptible flash of surprise cross the tall man’s face.

On a bank of seats to one side of the promenade, the audience had earlier witnessed the opening conversation in Back to Back Theatre’s Small Metal Objects between Gary (Sonia Teuben) and his friend, Steve (Simon Laherty). Their caring and honest discussion of love, relationships and loneliness reaches each of us us through the isolated intimacy of headphones linked to the performers’ wireless mikes as they amble towards us down the length of the promenade, somehow in a world apart from the crowd rushing by. Initially, we had scoured the crowd to find these two speakers amongst the couples chatting at coffee shop tables and the curious shoppers who look up at us.

Steve’s dependency on Gary is evident, but Gary is a loyal friend. He explains to Steve that he has to go into hospital for a knee reconstruction: “You’ll be alone. I know you rely on me.” The accompanying intermittent chords lend an almost filmic character to the performance, pacing out the seemingly simple dialogue. Later, jagged discords build suspense. Although the reality of this pair seems out of synch with the public around them, their friendship is much more tangible than anything else in this space.

Alan (Jim Russell), the tall man, wants to buy drugs for the participants of some kind of corporate event he is organising. We wonder if Gary knows what Alan, with his mumbled euphemisms, is seeking, since Gary refuses to give direct answers or confirm his complicity in the deal. The fleeting expression I think I see on Alan’s face indicates his surprise, founded in a common socially instilled prejudice, that a drug dealer could be someone with a intellectual disability.

As Alan tries to seal the deal, Gary's role is confirmed: “I only serve top shelf,” he says, silencing Alan with an index finger pointed right into the taller man’s face. But Steve is having a crisis, and doesn’t want to move from the spot to which he has been stiffly fixed since Gary and Alan’s telephone exchange. And Gary won’t leave him to get the gear from a locker nearby, so the deal’s off. Increasingly panicked, having failed to buy Steve’s co-operation or to intimidate him into moving, Alan calls in Caroline (Caroline Lee), his sharply dressed associate. She arrives at the library within seconds. It emerges that she is a change management consultant, a corporate psychologist, who tries to bribe Steve out of his crisis with the promise of private sessions in which he can discuss his problems, with the suggestion that she can arrange for a woman to make him less lonely, and finally, losing any remnant of integrity, an offer of a blow job.

But Alan and Caroline don’t have anything that Steve needs; their brisk, manipulative, corporate approach seems like a ridiculous pantomime next to his genuine expression of feeling and lack of pretension. His struggle is the need to be seen, to be a “full human being.” In frustration Caroline shakes his small frame violently: “You’re a fucking useless piece of shit!” The suited couple storm out. The exchange has empowered and liberated Steve. His sense of dependency reduced, he simply says, “I feel a lot better now, thanks.”

Set apart on the raised bank of seating and in our headphones we provide a spectacle for the passing crowd. But the stares that scan us are just curious. They don’t convey the misunderstanding or prejudice Steve and Gary have to bear. We have consented to our difference and we are protected by being a part of a collective, and by the distance the headphones afford. The experience is powerful in its simplicity, and we realise that what at first seems to be a “conventional drama of two invisible men” as the program note suggests, is also a profound and intelligent exploration of power, expectation and dependency, once we have worked past our snap judgments and fixation on the superficial.

Kristy Ayre, Glow

photo Rom Anthonis

Kristy Ayre, Glow

There’s something sub-human about her. There’s a woman down there on the floor below us, but genetically altered, injected with the genes of a tadpole. Or maybe the DNA of a newborn lizard. Yes, she’s just coming into being. She’s seems to be trying to figure out how to use her limbs. She’s shaking, reaching, rolling and then suffering spasmodic contractions. She can’t get off the floor. The floor, in this case is a pale, bluish-white rectangle set in the middle of the black box of the Scotiabank Dance Centre stage.

With every twist of the lizard-woman’s body, an outline of shadow-light traces her figure and changes shape with her. It seems to be a projection coming from above, but a projection activated by her movement. It’s very responsive: she rolls—it rolls, she reaches—it changes shape. It’s like an LCD halo conferred on the woman by the god-mind of a computer program whose eye is a surveillance camera. Wherever this twitching, spasmodic, humanoid moves within its elastic halo, it is always kept at the point of two bisecting lines of light, which have the ominous look of the cross-hairs of a rifle scope.

This is a new kind of dance partnering. I’ve seen other attempts to fuse dance and technology in ways that allow human body movement to automatically generate audio-visual response, but Glow takes it to a higher level. The software developed by Frieder Weiss allows the tracking system to respond instantaneously to dancer (Kristy Ayre and Sara Black in alternate performances) with sophisticated video imagery that superimposes itself on the dancer and floor in black and white geometrical, or amoeba-like, patterns. In one of my favourite sequences, the dancer makes extended sweeps with her limbs that generate spyrographs across the floor. Moving in another direction, a new graph overwrites the previous one, which is fading, creating a beautiful overlay of fan-like blooms.

There is an attempt here by choreographer Gideon Obarzanek to explore the theme of human versus software or, to put it more precisely, to investigate the dehumanizing threat of over-technologized environments. In this sense Glow is both pushing the limits of human-technological interaction, while cautioning against its potential abuses. The woman herself seems to be struggling either to control the technology, or to free herself from the metal-white projections that delimit her movements by putting grids or ropes of light around her. Sometimes her face contorts and she lets out little screeches that might have issued from the beak of a half-strangled tropical bird or a chattering monkey. Or maybe this is the sound an insect would make if its clicking apparatus was enlarged to human scale.

I’m feeling these possibilities stronger now than when I saw the show. To be honest, for all its technological brilliance, I found it hard to connect to Glow. The vocabulary of the floor choreography exhausted itself pretty early on. Maybe this is due to a limitation imposed by the technology. But even though the dancer generates the video display, she seems almost incidental to it, to a demo for the software. Prior to the show, Obarzanek told us that this was a first attempt at integrating his choreography with a new technology. So, fair enough, it may be that this is just stage one—an experiment to see if the technology is responsive. What’s missing is a genuine choreographic investigation, a developed theme or movement idea. Hopefully we’ll get that next time. At the moment the partners in this duet don’t have much to say to each other. Well maybe that’s because one partner is a software program and the other is a subhuman creature wondering what kind of world she’s been birthed into.

–

Chunky Move, Glow, concept, choreography Gideon Obarzanek, performers Kristy Ayre, Sara Black, concept, interactive system design Frieder Weiss, music & sound design Luke Smiles (motion laboratories), additional music Ben Frost, costume designer Paula Levis; Scotiabank Dance Centre, Vancouver, Jan 31-Feb 2; PuSh International Festival of Performing Arts, Jan 16 – Feb 3

Alex Lazaridis Ferguson is a theatre artist based in Vancouver. He writes plays, acts, and occasionally directs. He’s also a founding member of the performing poetry ensembles, AWOL Love-Vibe and VERBOMOTORHEAD. His writings on theatre have appeared in publications such as Canadian Theatre Review, The Boards, Transmissions.

© Alex Ferguson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jonathan Young, Palace Grand,

photo Tim Matheson

Jonathan Young, Palace Grand,

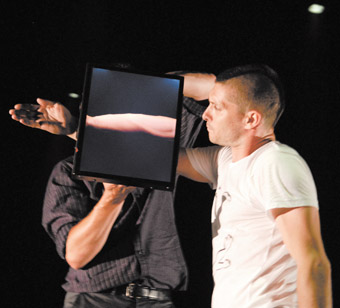

The fourth wall is covered with a taut opaque material. In the centre is a square hole: we look into a small cube. Against the painted backdrop of this floating box—a snowy, mountainous Canadian landscape, in turn-of-the-19th century picturesque style—a thin man with a bushy beard, the Tracker (Jonathan Young), opens a suitcase. In black boots, overcoat, black goggles and fedora, his deliberate and exaggerated in movement, stooped yet graceful, is part silent film comedian, part film noir private detective. He is a showman, a performer. The case is his recording device; he sets spools rolling within. He mimes to a voiceover of his own voice piped into the auditorium, as though speaking live. The voiceover mumbles as the Tracker pushes fur onto a can attached to the end of a tripod slung over his shoulder. Aha! A boom microphone! He creeps around the miniature stage, picking up the sound of mosquitoes, wind, the crunching of snow. Soundtrack and live action occur simultaneously, neither leading the other. “Cut that!”, the voiceover snaps. “And that.” “Leave that.” And, we are told, a distant roar (what is it?) contaminates Walker’s recordings.

A white curtain drops to cover the miniature stage. An even smaller hole in the wall, on the left, is dimly lit. The same bearded man, now stripped down to thermal underwear, has cans over his ears: vintage headphones. His movement more subtle than before, he pulls plugs from a switchboard. No longer performer, he is now facilitator. Techie. Operator. Silent listener. We hear the same voiceover: “Cut that.” He pulls out a plug and the buzzing of mosquitoes disappears. “And that.” Another pin removed and the whistling of the wind is gone. The Operator dismantles the recording until all that is left is the previously imperceptible, ominous rumbling of the distant roar, somehow evocative of the emptiness of this northern territory. The voice tells us that there is an operator out there, receiving these signals and messages. The Operator snaps upright, as if his personal space has been invaded. The voice continues: there is nothing between man and outpost apart from the signal of the message. “I’m just letting him know that he still means something to somebody”. The voice begins to chuckle, and the Operator laughs too, happy with this acknowledgment, perhaps relieved at the human connection in this vast wilderness. But the recorded laugh becomes warped and manic. The terrified Operator frantically pulls out all the plugs but the laughter won’t stop.

Earlier on in Palace Grand, by Vancouver’s Electric Company, we have been introduced to Walker the Writer-Explorer, the first facet of Young’s tripartite character, and his expedition to reclaim a mining shaft abandoned after the Klondike Gold Rush. Having dressed himself—top hat, waistcoat, spats, monocle, pencil—in a slapstick routine accompanied by stylised captions projected onto the screen wall that fills the stage (“Tonight only at the Palace Grand…”), he sits on a stool, scribbling onto a stack of paper. A projection of scrawled handwriting tells us that this man can’t be trusted. Has he written it himself? It’s not only this man, and his fragmented personality, that we shouldn’t trust. The world around him (or his perception of it) plays games with him, shifting the goalposts at the blink of an eye, the raising of a curtain. And the whole production plays games with us, throwing meaning over our heads to its miniature alter ego while we jump up trying to intercept the baffling game of catch.

Sophisticated technology in the structure and form of the show (alarming electronic sound interspersed with upbeat country jigs; projections of text, photographs and static onto the beautiful rabbit warren of caverns in the fourth wall; the perfectly timed uncovering and recovering of these holes) contrasts with rudimentary representations of technology within the show’s world (tin cans, a rocking chair sleigh, cotton wool puffs of smoke pulled by hand from a picture of a steam ship). As Tracker’s journey to the desolate north to try to find Walker, or what remains of him, is played out—bounty hunting and performance as metaphor for our existential search for self and meaning—theatre, writing, record-keeping are questioned as methods of investigating or representing life. We hear this man’s recordings, we see his scribblings, and there is a continuous and anxious ambiguity about which element of his personality is communicating to whom and when. This is the “Portrait of the Prospector writing a Self-Portrait of the Prospector.” This is Krapp’s Last Tape set against the fallout of the Gold Rush and the decline of vaudeville theatre. Its postmodern paradoxes will drive you mad chewing on your tail, if not chasing it round in a circle. Once you enter the fun fair hall of mirrors you might well get lost in your own eternal reflection.

In a classic postmodern sequence, the Tracker (or Walker, or the Operator: it’s getting harder to distinguish) has entered the empty cabin he believes to be Walker’s hideaway, only to find no trace of a body. He’s in a vaudeville theatre, we can hear the canned laughter and applause of an excitable audience. But as the red safety curtains open the sound cuts out. All we see are two electrically powered, sculpted hands rising up from a plinth, clapping mechanically. Later he finds a camera, some kind of simple projector: a small black box. He inserts two sticks into the edges of the camera, and two giant sticks simultaneously enter at either side of the floating box stage, threatening to knock him and camera to the ground. Confused, he stops. He decides to signal from the window of the cabin. He faces upstage and flashes the projector on and off blinding the audience. Are we looking in at him from the other side of the window? We lose track of time, of place, of where our position is in this relay. We see a body curled up in the cabin, its face a skeletal mask. We read handwriting that steadily becomes shakier: “It’s you who discovers the body. No-one else is watching but you.” He has run out of supplies. “These words are the only thing keeping me alive.”

And now, as I write, the impact of the visual and technological accomplishment of the show long past, these words are the only thing keeping me awake. From the opaque material of Palace Grand and the many interpretations I’m on the brink of unearthing from its postmodern mine, the resonating idea with which I am left is the danger of trying to read too much into it. Like the Tracker and his distant roar, I’m trying to hear too much. In the same way he doesn’t recognise his own voice or scrawl, I’m not recognising that which is right in front of me: the need to stop searching for answers, truth and gold.

Electric Company, Palace Grand, writer, performer, set designer Jonathan Young, director Kevin Kerr, lighting and set designer John Webber, video designer David Hudgins, additional video Jamie Nesbitt, properties design Rick Holloway, additional properties Stephan Bircher, sound design Kevin Kerr, Meg Roe, Allessandro Juliani, movement Serge Bennathan, costume design Kirsten McGhie, scenic painter Marianne Otterstom, technical director Harry Vanderschee; Waterfront Theatre, Vancouver, Jan 30-Feb 2

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg.

© Eleanor Hadley Kershaw; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Kristy Ayre, glow, Chunky Move

The sharp beams of light pulsing off her body are clearly digital, so a simple harmony is established when dancer Sara Black shuffles forward or swirls half-moons backwards in synch with the pulse of highly digitized music. The light often forms outlines that make the dancer’s movements seem liquid, erasing the stutter of a shuffle or a small leap. Other times Black looks like part of a video game, light shattering wherever it touches her edges. Glow takes place in a digital world created by Australian choreographer Gideon Obarzanek and German software designer Frieder Weiss. Highly sensitive video tracking software projects shapes in real time in response to movements below the lens. The images created this way are, in turn, read by the lens as well, allowing the dancer to manipulate the video world.

We are at the edges of dance technology and the challenge is to blend the fascination with tech and the meaning that choreography must provide. Fascination with sensors and the capacity for motion to generate real time sound and image thrives in gaming, new music and installation art. Audiences want to see what this new tool can, maybe can’t, produce. Glow satisfies that need but takes care, smartly, to create more than a software demonstration, partly by allowing the body be a familiar analog passion-maker as well as digital driver.

When a dancer shifts, rolls or twists inside Glow’s video environment, there are restrictions to work against. The tracking technology is most responsive to horizontal movements—to the points and edges the dancer’s body makes across the flat surface of the floor—and the technology creates shapes that are much more blunt than a body’s articulate arcs, angles or tremors. The choreography seems pushed towards horizontality because of these particulars.

A few times the work does feel like a demonstration, showing how many kinds of tracking this admirably sensitive technology can produce. Dark lines follow the performer’s outermost edges (finger, foot, elbow) as she dances on the white floor; there are dark shadows that only trace the dense core of her body; white lines that outline her silhouette like chalk against pure black. These effects are immediate and compelling, as if the light is magnetically attached to her. Most times the lines look about an inch and a half thick. In one passage they become very fine and the choreography is more focused on the floor, so when the dancer’s hands or feet land and the lines “stick” to them, it seems like Black is dancing inside an extremely stretchy elastic band. In other sections, the tracking produces smudged or delayed images. One passage becomes quite figurative: the dancer lies prone on the pure white floor and when she moves her arms up to meet above her head, soft grey blurs follow, slightly delayed. She looks like a child making angel shapes in snow.

This is where the choreography takes over from the machine. The dancer seems to roll over in shadowy snow, but then her body leaves dark tracks instead of gentle blurs and they, in turn, seem to rise and stalk her. Just when it appears that the show will be an intelligent but mostly pretty examination of software—just when Obarzanek has the audience used to this new “viscosity,” so to speak, of the air-and-light medium the dancer is immersed in—the dance suddenly moves into a struggle. It may be human against technology, or some struggle we’re not privy to, but Black breathes heavily, roars, hisses, screams: the analog body working with its own, ancient strengths. She returns to calm but the emotional arc is what brings Glow from tech study to art.

Clean, bright digital lines can create noise and tension but they can’t communicate this kind of visceral grit alone. In Glow, bodies shine and also decay. The contrast invigorates.

–

Chunky Move, Glow, concept, choreography Gideon Obarzanek, performers Kristy Ayre, Sara Black, concept, interactive System Design Frieder Weiß, music & sound design Luke Smiles (motion laboratories), additional music Ben Frost, costume designer Paula Levis; Scotiabank Dance Centre, Vancouver, Jan 31-Feb 2; PuSh International Festival of Performing Arts, Jan 16 – Feb 3

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 5

© Meg Walker; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

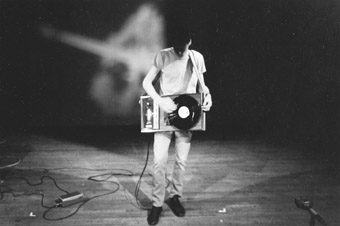

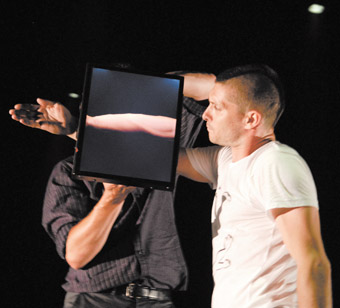

James Long, Clark and I Somewhere in Connecticut

photo Shannon Mendes

James Long, Clark and I Somewhere in Connecticut

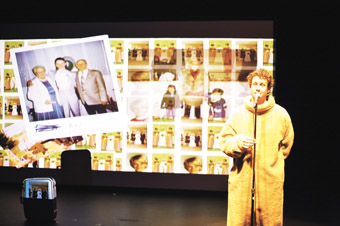

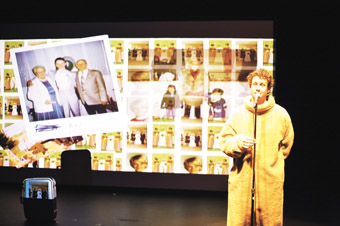

Clark and I Somewhere In Connecticut has to be about images, because it’s based on the contents of five family photo albums writer/actor James Long found in the alley behind his home, plus the events that unfolded when his fascination with those snapshots linked him to some of the people pictured there.

The faces in the photographs projected constantly onto screens beside or behind the bunny-suited narrator (in part James Long as himself) are blurred because he is legally restricted from revealing the identities of the family. Without seeing these strangers’ eyes, it’s hard to connect. However, the impact of the visual images is gradually displaced by the power of a few key anecdotes that are told several times, each time with subtle alterations. And, because names can’t be used, the narrator gives each person a voice-gesture nickname, such as grandpa Superman (swoops arms to one side, kicks foot up behind) or Sad Green (strokes L-shaped hand along cheek) or “Sschcrrh” (swings fists briefly beside hips)—“whose name is not fun to say.” A lighthearted dance, in a way, gradually underlies the storytelling and is partly what leads us from image to word.

Family photographs are intimate in some ways and illusory in others. The narrator—simultaneously Long and a fictional character—is somewhat lonely, wishing to join his lawyer friend and his family on their trip to Disneyland, or pretending to be the person in an album who has a job as a bunny actor for children’s events. He sometimes uses the photos to put himself to sleep, he says, imagining happy events at the family’s summer cabin; later, he meets the widow and learns those were weekends where the disintegrated family put up with each other for a few painful hours.

The narrator also loves dogs. He was walking his dog in a heavy rain when he found the suitcase full of photos, and he treasures the fifth album because it’s devoted to a toy pomeranian named Mandy. But even that love may be a fiction. One of the repeated anecdotes is about a kid working at a kennel who feels for a sickly, runt puppy abandoned by its mother and drowning in its phlegm. The kid decides to kill it by throwing the poor thing against the building. The owner of this story isn’t clear—the narrator tells it first, but eventually three others tell it with varying detail on video—but all like to agree that the puppy’s last thought was probably “wheee!” The way this anecdote morphs through repetition, and the way it’s impossible to know who “owns” the story, embodies the issues of ownership connected to the photo albums.

Clark and I Somewhere in Connecticut tells an entire family history through photographs. But what sticks is the visceral image (spoken not shown) of a Japanese man cannibalizing a young woman (the other most repeated, and true, anecdote) and the quadrupled experience of hearing how the puppy dies. It’s a fascinating reversal of how we usually give our eyes top authority when it comes to looking at pictures. If we’re willing to make that shift, maybe we’re also willing to consider whether story ownership is determined by who cares about it most—who digests it, who makes it theirs emotionally and physically. Or maybe we’re not willing, because we feel protective of our photo albums. Either way, the layered storytelling co-created by Long, onstage video artist and co-performer Cande Andrade and six offstage members of Rumble Productions is superb. The bunny suit always carries a sheen of sadness, and the nice-guy narrator—willing to help an old lady on a bus—is someone we trust. The unusual disempowerment of the photographs creates an open channel for us to linger in the narrator’s emotional world, and he tells us about it so well.

Rumble Productions & Theatre Replacement, Clark and I Somewhere in Connecticut, created by James Long, Cande Andrade, Owen Belton, Camille Gingras, Craig Hall, Anita Rochon, Jonathan Ryder, Maiko Bae Yamamoto; Performance Works, Vancouver, Jan 30-Feb 2; PuSh International Festival of Performing Arts, Jan 16 – Feb 3

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 4

© Meg Walker; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Instructions for Modern Living

You're driving home alone, late at night in your own city, but the light is strangely green so it feels like another place. A place where you know no one, and everything’s deserted. The empty spaces in this place are bigger and emptier than you remember spaces being. It’s cold outside. The lights that gleam on your car dashboard are a comfort, and you reach over to click on the radio because it feels better to hear a voice in the night.

Duncan Sarkies late night voice is speculative and gentle. Nic McGowan provides the quiet, looping soundscape, which keeps you floating in the strange space of your own city. Together, they may take you away—to the loneliness of outer space, even—but it feels the same as the loneliness you already know. Here: in the static light of a television without programming; here: outside a cottage in the country, glowing with light, that you will never enter.

New Zealand’s Instructions for Modern Living gives us a few minutes with the late night talk radio host who defines the work’s zeitgeist. It also gives us the manager of a fast-food joint, seducing and abandoning a young employee, a couple who have nothing to talk about, and a woman named Wendy who doesn’t know a ghost is following her everywhere. Each discrete scene is created with Sarkies’ storytelling, and McGowan’s accompaniment with voice, piano, theremin, and glockenspiel, and his old-fashioned whistling to punctuate the dark. Shaky, slow-moving video projections light the back wall. We have all the time in the world, and dawn is hours away. The reverb in the music is the sound of time crawling, through the vast empty space between me and you.

Instructions for Modern Living contains few instructions. Drink gin and tonic. Don’t commit adultery. Have friends. There are no guarantees, even for friendships. Words on the screen inform us that, with friendships, “results may vary.” There are few insights among the instructions. In fact, the script deliberately avoids opportunities for insight, highlighting that sense of something missing that is the core of loneliness. “What does the earth look like?”, an earth-bound radio controller asks an astronaut in orbit at three o’clock in the morning. “You know the picture of the earth from space, on the cover of an atlas? It kinda looks like that,” the astronaut replies, missing the chance to pass on something meaningful through the night.

There are things worth staying up for. Love or danger. A great dance or a fine book. A moment of connection. None of the sketches show us any of these moments worth a loss of sleep—with one exception. A man lies awake because his beloved is stretched out on the bed, leaving him only a tiny triangle in the corner. “I can’t sleep like this”, he tells himself. But because he has waited so long for this person, because he doesn’t understand why his luck has changed at last, instead of waking his lover he writes himself notes in the dark: “you lucky bugger, you.”

Without love or danger to propel us, we clock the midnight hours with instructions, hoping for the kind of insight that sometimes comes in the middle of the night, and which we always forget to write down. The moment seems to come near. All those children who are told that the story ends happily ever after, what happens to them when they grow up and find out it isn’t true? Is that the beginning of loneliness? Does loneliness come because there is a separation between who we are and who we used to be? The insight drifts away, the critic was taking notes but didn’t catch it anyway, and the insubstantial night fades. If we really want instructions, we’ll have to invent them ourselves, in the morning.

Instructions for Modern Living, created and performed by Duncan Sarkies and Nic McGowan, technical director and operator Natasha James, lighting designer Martyn Roberts, video Duncan Sarkies; Vancouver East Cultural Center, Vancouver, Jan 30-Feb 2; PuSh International Festival of Performing Arts, Jan 16 – Feb 3

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 6

© Anna Russell; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

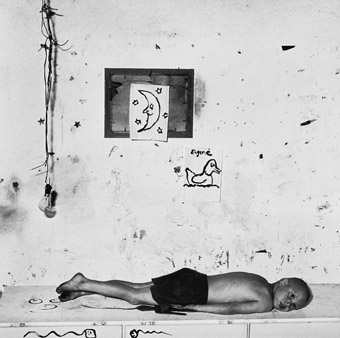

Peter Snow, Tess de Quincey, embrace: Guilt Frame

photo Samuel James & Russell Emerson

Peter Snow, Tess de Quincey, embrace: Guilt Frame

IN A WELCOME AND RADICAL MOVE BY THE SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY, INCOMING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS CATE BLANCHETT AND ANDREW UPTON HAVE PROGRAMMED A TWO-WEEK WHARF2LOUD SEASON OF TESS DE QUINCEY’S EMBRACE: GUILT FRAME, AN INTENSE 40-MINUTE MOVEMENT WORK “ILLUMINATING THE SHAPE AND RHYTHMS OF OUR INNER LIVES.” EACH PERFORMANCE WILL BE FOLLOWED BY DRINKS AND DISCUSSION. THIS DUET BETWEEN SYDNEY-BASED DE QUINCEY AND MELBOURNE ARTIST PETER SNOW IS PART OF A LARGER DE QUINCEY PROJECT CONNECTING WITH INDIA, SIMPLY TITLED EMBRACE.

Embrace is an ongoing exchange between De Quincey Co and Indian artists in partnership with Monash University. Seeded in 2003 in Kolkata, the Embrace exchange explores a relationship with The Natyashastra, the seminal ancient text and cornerstone of Indian artistic practice, with Body Weather, the practice developed by Min Tanaka and his Mai-Juku Performance Company in Japan. Tess de Quincey was a dancer with that company for six years (1985-91) before returning to Australia where she has continued to perform solo and with her company, as well as teaching Body Weather.

De Quincey defines the developing relationship between The Natyashastra and Body Weather as “a synthesis of Eastern and Western practice and thought, bringing together ancient Buddhist and Taoist thinking with elements of 20th Century Western philosophy. It’s a radical, open-ended exploration that melds contemporary dance and sports theory with martial arts, traditional Japanese/Asian theatre and Western avant-garde arts practices.”

Visiting old friends in India with a great library, de Quincey found herself one day sitting on the balcony reading The Natyashastra and feeling, she says, “a resonance and connection with my own work but at the same time a lot of differences.” Here, she thought, was a means with which to engage with Indian artists.

De Quincey wasn’t thinking of absorbing an Indian performance methodology but connecting with certain “energetic states” common to The Natyashastra and Body Weather. But it’s also, she says, about “the placement of the ego—the position of non-self-expression and utilising the body as a transformative entity.” De Quincey had turned to Body Weather in response to “a crisis of faith in relation to Western dance, because I knew I wasn’t getting what I needed.” Workshops in Bali with Yoshi Oida in 1984 in Topeng mask work, Noh Theatre and meditation with a Shinto priest provided the first steps for a new direction that lead her to Body Weather.

For de Quincey, leaving Western dance was to escape conventional notions of form and expressiveness: “Working in Japan for six years I became really aware that the placement of the individual is really different there, because you see the individual as servicing the communal space…You’re not concerned with the “I”, you’re actually concerned with the space in between.”

I ask if taking on Body Weather is to learn a discipline or evolve a particular state of being. “I think in one way it was almost like trying to shed. The first couple of years were about coming down to bedrock. Really everything I’d learned in terms of physical work had to be dropped. The Body Weather training on a mind-body, muscle and bone level is more like gymnast’s work. It’s quite purist in that respect. Most dancers are working to put aesthetic relationships into their body from the word go. In effect, this approach tries to drop them. All those things take a long time to shed.”

I wonder what de Quincey is doing if not actually dancing in the Western sense? She replies, “Developing strength and relationship to ground—the grounding that is embodied in that. For example, the mind-body workout is purely about understanding the depth of relation to the ground but also about working space together. The communal body is also a very big part of the mind-body. So you see the body from outside working into the greater body. And that in effect is another way of working, a preparation for performance.”

De Quincey senses profound cultural differences in performance and audience reception. “A Western dancer will perceive the internal line of the body cutting through space. So you see the line of the arm working through space. It’s like the geometry of the body is the indicative factor. For Mai-Juku, the body is being danced by the space. So the softness of the arm is totally different. Even if you were to make an arc through space, the reason for doing it would be so different that the expression of it is ultimately different. Often from an audience point of view you’re certainly aware watching this work that there’s a very different sense of time and space, especially of time. I think part of the thinking of Body Weather is to open up a different doorway. And of course, as soon as you shift into a new speed outside your natural speed, you shift out of normal mode.”

Not surprisingly then, framing is a term de Quincey uses frequently. In Kolkata in 2003 she worked on embrace: Limitless with 40 children from the slums, staged in the streets, and embrace: A Silent Thread, with 14 dancers and many locals in a spectacular site-specific work moving from a park to an old home, now a classical music venue. “The sense of framing has partly come about through doing site-specific works. A Silent Thread established a frame for audiences in a stately old home, shifted it around and took them through different frames. I was very affected by the portraits of the old Raj you see somewhere like the Bengal Club. If you’re directing the audience’s attention what they are seeing is, in one sense, a filmic frame. As you move through a site you’re drawing in on different focuses, using performers to delineate frames…and of course, there were plenty of frames within that building—windows and doors.”

But in embrace: guilt frame, there’ll only be one frame, “a gilt frame”, declares de Quincey, a metre wide that she and Snow will perform in, going though a number of “energetic states.” She fills me in when I wonder where the term comes from: “I’ve been working a lot on Gestalt with Philip Oldfield, a very interesting therapist and psychologist based in Sydney. Working with him, I felt an immediate parallel world to Body Weather, but it was a psychological understanding of the same elements. He reads the body completely. His whole relationship to understanding psychology is from the micro-signalling I understand to be the communicating factor in any performance. He speaks about energetics, so maybe my reference comes from that.”

De Quincey details the structure of the performance: “We’ve gone along with The Natyashastra states—love, laughter, sorrow, anger, the heroic, fear, disgust, astonishment. We run through a cycle of them and then, for eight minutes at the end, we’re improvising. The first state is love. You take the eight states and put them inside love. Within love, you have also astonishment, anger, fear and so on; but the base state is love. It’s almost like a holographic world that you can keep breaking down. The first time we did it as a total improvisation. I’d basically conceived it as the frame, the eight emotional states and physical lock-in points within, that delineates the agreement between the performers as to which state we’re in. And we’re going from one state to the next, as simple as that.”

There’s no sense of a one-off about embrace: Guilt Frame for de Quincey: “I find it very interesting, the idea of process and product. The only reason we can make this performance is because of all the other Embrace performances before it.”

Music is also an important component of the performance for de Quincey: “I’ve been waiting for a long time for a way to use Ligeti’s Symphonic Poem for 100 Metronomes (1962), which I discovered years ago and just fell in love with. But we couldn’t get permission from the estate to use it. So I asked Michael Toisuta to make a piece as a homage to Ligeti. It’s very different from the Ligeti, but it uses metronomes. We tried using computer-generated sounds but it was a disaster so we bought metronomes. In the Ligeti I’ve always liked the extraordinary patterns that only last for brief moments emerging from absolute chaos.

“But the interesting issue is how we understand patterns and perceive them. And the music seemed to me the means by which to open the space of the framing of chaotic relationships in our lives. The metronomes create a bedding, an endless felting of layers, but at the same time they cut through them. We’ve had to create that feeling afresh. And that’s been an interesting parallel experiment. Michael’s composition is much more musical than Ligeti’s, even though he didn’t set out to do that. And there are moments where it’s completely like a Balinese orchestra. And we hadn’t looked at that either.”

But the music is not there to be performed to, says de Quincey: “It’s a timepiece. It’s there all the time. To me, part of what I understand this piece to be about is time, because you can’t work with emotions without having time—all those long threads and where they go back into our histories and forward into our future imaginings. Those perspectives seem to be absolutely embedded in the issue of time and space, even thought it’s a tiny gilt frame space…As soon as you bring the world down to a matchbox, space becomes endless as well. It’s the paradox of scale.”

–

Sydney Theatre Company, Wharf2Loud, embrace: Guilt Frame, created and performed by Tess de Quincey and Peter Snow, original Concept Tess de Quincey, set Designers Russell Emerson, Steve Howarth, lighting designer Travis Hodgson, sound designer Michael Toisuta; Richard Wherrett Studio, Sydney Theatre, Feb 27-March 9

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 45

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Lotus Eaters

photo Heidrun Löhr

The Lotus Eaters

WE ARE POLITELY USHERED INTO WHAT APPEARS TO BE A FUNKY BASEMENT BAR – COLOURED LAMPSHADES SUSPENDED FROM THE CEILING, CUSHIONS AND COMFY CHAIRS SCATTERED ABOUT, AND A BABY GRAND PIANO COMPLETE WITH LOUNGING SINGER, READY TO CROON. THE MOOD IS DREAMY, AND AUGMENTING THE INTOXICATION, SMILING WAITERS DISTRIBUTE SHOT GLASSES OF WHAT THEY ADVERTISE AS “LOTUS JUICE.” A GAUDILY DRESSED YOUNG MAN TAKES THE MIKE. “YOU HAVE TWO CHOICES”, HE DRAWLS. “I CAN TELL YOU A STORY, OR YOU CAN FUCK ME.” THERE’S A SMALL PAUSE, AFTER WHICH HE SMILES AND BEGINS TO TELL THE STORY OF ODYSSEUS, LOST FOR 20 YEARS ON HIS JOURNEY HOME TO ITHACA. LOST, AND LONGING FOR HOME.

On the other side of the theatre space, hitherto covered by gauzy drapes, another performance begins in response to the story offered in the lounge bar, with excerpts from Odysseus’ story presented through tableau and declamatory monologues. Performers struggle across a stage covered in a thin layer of dirt, with a grid of naked light bulbs overhead, creating islands of light amongst the darkness that appear and disappear as they are switched by passing performers. It’s a simple but highly effective technique. The stage morphs strangely as the performers navigate their course endlessly through these islands, but as the map continues to shapeshift, the course ahead becomes no clearer.

The dirt crackles under our feet as we are invited to leave the comfort zone around the bar and inhabit the space of the lost travellers. Around us, a vast number of young performers strut and fret their minutes upon the stage, recalling on the dimly lit field of dirt encounters and incidents from Odysseus’ unwilling journey—the sirens, the Cyclops, and Circe’s island where the crew are transformed into pigs. From the lounge area performers read letters to real and imagined distant homes. As Odysseus struggles with both terrible monsters and impossible longings for a home denied him by the gods, the performers describe a more pedestrian melancholy. Finally, Penelope appears, at home in Ithaca waiting faithfully, fending off the predatory advances of an army of suitors. Rather than a happy homecoming, our hero returns and promptly slays all of his would-be rivals, filling his longed-for home with blood. Journeys, it is abundantly clear, change people, and sometimes these changes can be terrifying to behold.

For all its evocative ambience, there is a curiously disconnected quality to Lotophagi. There’s a fine line between exploring states and stories of losing oneself and being lost, but Lotophagi, for all its moments of beauty, feels most often like the latter. As a sprawling epic, it shows the audience some potentially wondrous sights. But these remain postcard moments, happy snaps from which we must immediately move on. Little in the work seems to build or linger and, unusually for an ensemble emerging from PACT’s traditionally strong training program, the cast don’t ever feel as if they’re operating in the same performance work. For me, Lotophagi, while colourful and frequently interesting, remains mostly a collection of disparate elements—a work whose aimlessness, unlike Odysseus’, cannot be solely blamed upon the curse of the gods.

PACT Youth Theatre, Lotophagi: The Lotus Eaters, co-director Regina Heilmann, co-director/design concept Jeff Stein, directorial input Chris Murphy, Chris Ryan, sound design James Brown, lighting Frank Mainoo, designer Claire Sanford; PACT Theatre, Nov 22-Dec 9

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 36

© David Williams; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

IT WAS WONDERFUL TO SEE THE WESTERN BROADWALK FOYER OF THE SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE DURING THE SYDNEY FESTIVAL AWASH WITH VIDEO MONITORS LARGE AND SMALL SURROUNDED BY EAGER PRE- AND POST-SHOW VIEWERS. WHAT THEY SAW WAS BOUNTY FROM A TREASURE CHEST OF AUSTRALIAN DANCE FILM CURATED BY REELDANCE’S ERIN BRANNIGAN.

Small monitors with associated touch screens offered a selection of works and two pairs of headphones for shared viewing, and the opportunity to cut out the buzz of the crowd and immerse yourself, glass of wine in hand, in up to 14 works ranging from Tanja Liedtke’s One Cell, Nalina Wait and Jane McKernan’s Dual and Samuel James and Rosie Dennis’ Simulated Rapture to films of ADT’s Devolution and Chunky Move’s Glow.

The large ‘3 Screen’ outside the Drama Theatre featured The Fondue Set (collaborating with Shane Carn) re-creacting in serio-comic detail The Lorrae Desmond Show, alternating with Force Majeure’s The Sense of It, and Margie Medlin and Rebecca Hilton’s Miss World.

The ‘Screen Wall’ also provided viewing on a larger scale but changed content daily, featuring award winning dance films such as Gina Czarnecki and ADT’s Nascent and Sean O’Brien and Yumi Umiumare’s Sunrise at Midnight, a documentary of Stephen Page’s Kin and works by Anton, Shaun Parker and Natalie Cursio among others. A ‘VJ’ program on more large screens put works by Bangarra, Chunky Move, Dance North, Lucy Guerin Inc, David Corbet, Sue Healey and others in the mix.

For successful viewing of works on the big screens, less crowded, quieter foyer moments were preferable, but the curious were not deterred, while the small monitors offered ideal intimacy. Dance Screen was a popular venture that warrants repeating. Certainly for the many hundreds who course through the Opera House daily on tours the program should have been running all day. Not only did Dance Screen reveal to the audiences packing out the festival’s Movers & Shakers dance program a wealth of dance film of all kinds, but it provided audiences with options—either to mingle or relax into another world of dance altogether.

–

Sydney Festival, Moves & Shakers, Dance Screen, curator Erin Brannigan, Theatre Foyers, Western Broadwalk, Sydney Opera House, Jan 5-16

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 44

© RealTime; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

mily Amisano, Trish Wood, Being There

photo Fiona Cullen

mily Amisano, Trish Wood, Being There

IN THE PAST 18 MONTHS, INDEPENDENT ARTIST CLARE DYSON HAS PRESENTED THREE MAJOR WORKS OF DANCE THEATRE, EACH OF THEM DEALING WITH SITUATIONS IN EXTREMIS, OR AT LEAST IN THE LATEST CASE, FRAUGHT. THEY ARE CHURCHILL’S BLACK DOG, ABSENCE(S) AND, NOW, BEING THERE. THE FIRST OF THESE UTILISED CONVENTIONS OF CHARACTER (ALBEIT IN A CONTEXT WHERE THE CONCEPT OF CHARACTER WAS UNDER STRAIN); THE SECOND IMMERSED THE AUDIENCE IN AN INSTALLATION WITH OVERLAPPING MEANINGS DEPENDENT ON THE POINT OF VIEW. BEING THERE WEAVES PURE DANCE AND A RECORDED SPOKEN NARRATIVE INTO A SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL MOSAIC. IT WAS DEVELOPED AT TANZFABRIK IN BERLIN WHERE IT HAD AN INITIAL SHOWING.

These three works add up in diverse ways to a consistent, heuristic theatre of ideas based on Dyson’s investigation of audience agency and heightened by an unashamed proclivity for the potent poetics of Romanticism. Her rigorously conceived work is always sensitive to the surprising complexity, the mystery, the flawed beauty and fragility of life.

Dyson is canny in her choice of like-minded collaborators, including Mark Dyson (lighting) and Bruce McKniven (design). The circumscribed performance space of this new work is an ellipse delineated by muted lighting and a surround of chairs, a minimalist configuration that nevertheless gradually assumes a meaningfulness compounded by the failure of different geometrical planes to meet and the syntactical sense of ellipsis whereby words are left out and implied. There are gaps in the seating arrangements as transit points enabling the dancers to move here or there. As if in the complete intimacy of a dance studio, the dancers are within reach, and the audience is face to face.

Being There is about a woman who has an affair in a foreign country (over there), betraying her husband at home here in Queensland. Her predicament is that she is at a moral and artistic impasse. “When she was younger, she imagined the purpose of art was to move. Audiences, I believed, want to be discomforted. Move where? She wonders now.”

Being There constitutes a kind of dream fugue, a non-linear series of glimpses from past events. It plays on the dancer/text relationship, and portrays a struggle for mastery. Writer Siall Waterbright’s dispassionate vignettes amount to a cool appraisal that the unnamed woman cannot be there, wherever she is. Ironically the unseen woman’s infidelity is a poignant quest for visibility. By contrast, the dancers take a stand in the here and now, not standing in for the text. They choose to be present, authentically themselves, introducing themselves to the audience, even taking time for a water break. But sometimes the text gains ascendancy and the performers are over there. Lyrics to a song are in a foreign language. A woman removes her knickers, or strikes matches, illuminating, as Dyson says, “the domesticity of everything.” Sometimes the vocalized text takes centrestage, relegating the performers to the dark. Dyson conducts this antiphony seamlessly.

The two performers, Emily Amisano and Trish Wood, are personable, casually dressed, just two young women who dance beautifully, and beautifully together. They double relations in the text, traverse the same emotional territory, but as themselves, they unnerve us. We are proximate to them, breathing with them. They are falling women. They really cry, blow their noses, bruise themselves and slap the floor in an anguish which refracts rather than reflects the text. They are so committed that we are plunged to the depth of our own resources of memory and desire in order to meet them, and ultimately to realise that our own moral situation is fatally compromised or at the least exigent. As we leave, we can only match the “uncertain dignity” of Dyson’s protagonist. For a little while we cannot look each other in the eye.

Dyson has a dangerous flair for not allowing the audience to resile. Hers is an existential art. The title Being There alerts us to the dialectical relationship with Absence(s). In that earlier work Dyson eviscerated us by dramatically conveying the contingency of human existence, turning us into hollow men and women forever haunted by loss and death. In effect, denying our presence. Being There seemingly rejects the Sartrean take on being-for-others, or existing purely in terms defined by the Other which is so problematic for her fictional protagonist. Instead, an open invitation is issued to be fully present to a face to face encounter by directly challenging the stance of the audience as uninvolved observers. When Dyson’s art moves us, it moves us to ethically new positions. We are moved by the naked intensity of the live performers, and even sympathise with the one who is not present. We care for them all, and want to take responsibility for them. This is the possibility for an ethics defined by the philosopher Levinas.

Heidegger points us towards her method. Clare Dyson is at pains to provide a ‘clearing’ where “we can apprehend the being of a being, apprehend the being as it is, where it is.” To pull this off is wonderful and, I think, important. Art wasn’t meant to be easy. If you have the taste for this sort of thing, it sure as hell beats shopping.

Being There, creator Clare Dyson with dancers Emily Amisano, Trish Wood, writer Siall Waterbright, designer, Bruce McKniven, lighting designer Mark Dyson; Judith Wright Centre of Contemporary Arts, Brisbane, Dec 12-15, 2007.

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 43

© Doug Leonard; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Brindabella, Balletlab

photo Jeff Busby

Brindabella, Balletlab

BALLET LAB’S WORKS ARE NOTHING IF NOT IMAGINATIVE. CHOREOGRAPHER PHILLIP ADAMS HAS, OVER THE YEARS, CREATED MANY SCENARIOS DRAWING ON MYRIAD SOURCES, LITERARY, MUSICAL, FILMIC AND MYTHICAL. BRINDABELLA IS NO EXCEPTION. PART AUSTRALIAN FOLKLORE, PART SOFT-PORN, THE WORK CANVASSES SEVERAL IMAGINARY MOTIFS. THERE IS A SUGGESTIVE GRANDEUR ABOUT THE OPENING. RUCHED, CRIMSON CURTAINS BEDECK THE MALTHOUSE’S MERLIN THEATRE, CREATING A PROSCENIUM FRAME. THE RICHNESS OF THE FOLDS OF RED MATERIAL BROACHES A SENSUOUS DIMENSION REDOLENT OF THE 19TH CENTURY OPERA HOUSE. BELOW DECKS, A SUBMERGED MUSICAL GROUP AMPLIFIES OPENING NIGHT ANTICIPATION.

The music begins, distorted shadows of the musicians evoking a dark palette. A courtly quintet emerges through the curtains. A woman, Brooke Stamp, in a sumptuous Louis Quinze gown, preens herself in a small mirror. Her courtiers circle, fawning fauns. Their furry outfits suggest a less than historical take since these Rococo mannerisms are promptly discarded as the curtain reveals an archetypical forest setting, complete with obligatory wolf howls.

Forgive the detour, but we could be at St Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theatre, watching an adaptation of Roman Polanski’s Fearless Vampire Killers. As in that 1960s satire, mittel European fairytale joins folksy ballet to create an ironic twist on horror. Predictably, the woman is at the core of the tale, a symbol of sexual difference encircled by male activity, their fur suggesting beastly intentions. Although Brindabella purportedly draws on Australian folklore, the male dancers reappear strapped to pine trees, not eucalypts. As the heavy foliage lists across the stage, the men stumble to keep up. I worry for their health and safety. Happily the trees are discarded and somehow the costumes melt away.

The five performers are now running in unison, tracing a large circle over the entire floor. They each discard their clothes as they run, over and undertaking to keep up with the group. This was a very special moment in the development of the work, an eye in the storm of parody and pastiche. The simplicity of the running, the lack of costume and the unison of ordinary movement forged an aesthetic break which could have been taken in any number of directions. I’m not entirely sure where things went at this point. Movements blur in sweaty encounters and departures. Two men grapple in a roughly honed male-to-male duet.

Eventually the group reforms and takes to the front of the stage wielding chrome and leather—the disassembled wheels could be used for circus, unicycles, a bit of juggling perhaps? But no, slowly a motorcycle in bicycle form is pieced together. The performers suggestively straddle the leather seats, leading us into the cum-soaked world of Pumped, Rimmed and Loaded. Vintage Adams duets, triplets and groupings occur, performing perfunctory folds, bends and twists to create a series of tableaux. Ultimately couples team up to consummate all manner of intercourse. Where sexual innuendo may have permeated the rough and tumble of Adams’ previous works, here suggestion well and truly comes out of the closet, reflecting the iconography of Brindabella’s publicity shots. Heads loll in synch as bodies are straddled, while jeans are whipped off to castigate the reticent. Someone’s bum protrudes as his jeans are pulled down. The whole scene could have been enacted in suds, mud or lubricant. Although the borders of porn were not transgressed by this theatrical play, the audience’s ‘premature’ clapping at the end of this section suggests a certain discomfort—or was it appreciation? In any case, the story doesn’t finish here. Cast and audience are transported to a darkened stage sundered in the distance by a blinding central light. Naked and holding ostrich feathers, the performers approach the pearly gates of Burlesque afterlife.

This was another moment in the flow of Brindabella where a certain conceptual space was opened up. I wonder whether this and the earlier running sequence was the work of Adams’ choreographic collaborator, New York’s Miguel Gutierrez? Both sections summoned an existential vortex. This was in part the consequence of marked contrasts—while the sexual play was quite stylistically rendered, the running and the final section were stripped back, lacking artifice. Similarly, the mannerisms of the opening courtly scene were markedly absent in the “boy stripped bare” section at the work’s end. This difference resembles that between western art’s classical nude and Lucien Freud’s naked bodies. Narrative drops away here in favour of something else. Personally, I would have liked to see more power on the part of this something else, to have seen it ‘queer’ (displace the centrality of) the rest of the material, its parody, irony, and recognisable iconography.

It’s not for me to say where this work might go, but 20th century artists such as Bataille and Klossowski played with the boundaries of art, pornography and philosophy. In another (after)life, Brindabella might likewise challenge its own boundaries, setting up a relation between its multiple differences of genre in such a way as to inform its divergent movement aesthetics. It is a story of desire, of desire unbound, with the potential to flow beyond the boundaries of convention. This relates to the sexual, sensual but also kinaesthetic conventions which pertain to the queer sexuality underlying the work. To challenge such boundaries is to challenge the morality inherent in heterosexuality, something Brindabella was, I think, attempting to achieve.

–

Balletlab, Brindabella, choreography Phillip Adams, Miguel Gutierrez, performers Derrick Amanatidis, Tim Harvey, Luke George, Brooke Stamp, composer: David Chisholm, set & lighting Bluebottle, musicians Lachlan Dent, Peter Dumpsday, Timothy Phillips, Nic Cynot; Malthouse Theatre, Melbourne, Dec 5-8

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 43

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

David Tyndall

THERE IS CHANGE AFOOT AT DANCEHOUSE IN MELBOURNE, AS THE SMART NEW MICRO-SITE WHICH ACCOMPANIES THE 2008 WEBSITE SUGGESTS. NOT ONLY IS THE LANGUAGE AND IMAGERY CLEARER, SHARPER AND ALTOGETHER MORE DYNAMIC, BUT THE CLUSTERING OF INITIATIVES FOR OPEN APPLICATION IN 2008 SUGGESTS AN ENERGY WHICH ARTISTIC DIRECTOR DAVID TYNDALL IS KEEN TO COMMUNICATE.

Tyndall updated the website himself, admitting that, “As soon as I was in the door, I wanted to address the way Dancehouse is seen by the community and how we see ourselves.” Tyndall is satisfied that his 2008 programme portrays the kind of forward-thinking he has promoted in his first year in the position.

“There has been a lot to do”, he says. “Dianne (Reid, the previous artistic director) left in August 2006 and I did not start till January ‘07, so although her excellent initiatives continued with the help of David Corbet, we had been kind of rudderless for a while. The Board had been working hard to address issues of management and artistic direction, so that by the time I arrived, as the first ever full-time artistic director, they were ready for me to take the reins.”

Tyndall is a VCA graduate and former dancer with recent producer experience with Chunky Move, Dance Works and Expressions dance companies. He has taken to the role of artistic director with relish, delivering a busy program in 2007 and collaborating with his board to instigate organisational change. Tyndall has just advertised for two additional part-time positions, Programme Producer and Venue and Production Co-ordinator, and is excited about how this will free him for further strategic planning.

Dancehouse is triennially funded by both the Australia Council and Arts Victoria, yet its cash turnover of $320-$350K seems small in relation to the volume of activity crammed into the busy program at its North Carlton home. “A huge amount of what happens here is generated by the community”, says Tyndall, “Our members bring their own projects and momentum to the program. There is a challenge to balancing the content we generate and that created by the community. We have to ensure that we are still accessible to the dance community. We do that by remaining affordable and available to hire. In the past couple of years, Dancehouse has been stretched to breaking point with a mass of activity and constant communication. There was a danger that people felt overwhelmed by all this undifferentiated activity and switched off. The board encouraged me to streamline the activity. I have done this by identifying three core areas: research, training and performance. Of course there is a great deal of crossover between those areas and we encourage that. This just helps us to create balance and leave gaps for the community to input.”