Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

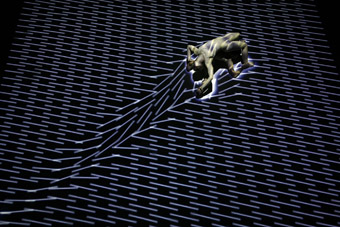

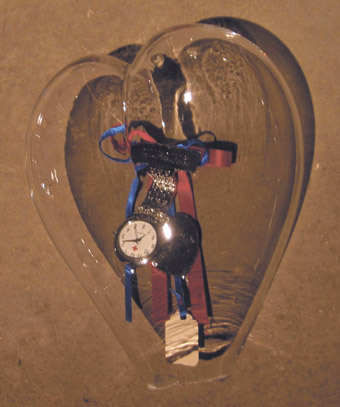

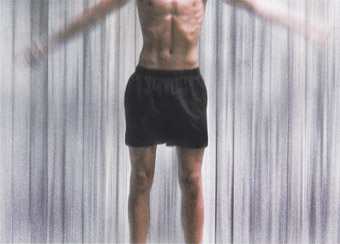

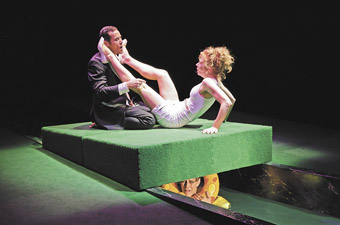

Scotia Monkivitch, A Mouthful of Pins

photo Bev Jensen

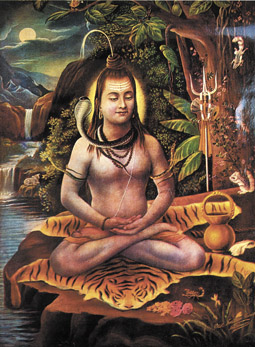

Scotia Monkivitch, A Mouthful of Pins

THE NEST’S A MOUTHFUL OF PINS ATTEMPTS TO WRING ENDURING BEAUTY FROM THE TERRIBLE EXPERIENCE OF MELANCHOLIA OR DEPRESSION. KOKO (LEAH MERCER), AS OUR CONTEMPORARY, CARRIES “THE TORN PAGES OF HER STORY UP THE STAIRS OF AN OLD VICTORIAN APARTMENT BUILDING IN BRISBANE.” HERE SHE MEETS, OR IMAGINES SHE MEETS, TWO DIFFERENT HISTORICAL CHARACTERS, ONE AN EXTRAORDINARY REGENCY PERSONAGE BASED ON THE LETTERS OF JANE AUSTEN (AOLE T MILLER), AND THE OTHER A 50S HITCHCOCK BLONDE/HOUSEWIFE (SCOTIA MONKIVITCH). THERE IS A SETTEE AND A COLLECTION OF BIRD-LIKE COMMEDIA MASKS SUGGESTING THAT THEY ARE KOKO’S ADOPTED PERSONAS.

Madness is in the air. Nature is outside (flitting bird images) and projected titles record the remorseless succession of days in a series of cryptic notes and quotes: “‘There isn’t a Monday that would not cede its place to Tuesday.’ Anton Chekhov.” Live music (piano and violin), song, visual images, the dislocation of narrative units along with highly suggestive symbolic actions invest the piece with deliberate ambiguity. These strands came together most movingly in an extended piece played by a violinist over the recumbent, temporarily enervated and silent figures on stage. At this point it became evident, looking at it from a Lacanian perspective, that “The things we are dealing with…are things in so far as they are silent. And silent things are not quite the same as things that have no connection with words.” At the very beginning, in order to define the space, words on paper are laid out in a circular pattern blank side up so that they are ritually obscured from sight. We are not dealing with a clinical case. What is of primary importance is, in Julia Kristeva’s terms, the rhythms and alliterations of semiotic processes which, combined with the polyvalence of sign and symbol, “unsettles naming.” In the best sense, The Nest’s project is grandiose: attempting to capture the sublime in art.

As a writer, Leah Mercer is obviously conversant with psychoanalytical concerns but (rightly) stops short of fully articulating them: “Sadness is a memory of something long ago, can you call it a memory if you can’t remember it? A memory of something I cannot quite recall, the unremembered, the unrememberable sitting there high in my chest.” Her adoption of a depressed person’s monotonous and rhythmically repetitive delivery stems from this sadness lodged in her chest, sentences that, as Kristeva describes them, “come to a standstill.” I admired what amounted to a sustained virtuosic performance of its kind, but questioned whether Mercer’s affects contributed to theatrical efficacy. At times it seemed that the beating heart of the production had also come to a standstill, and surely the beautiful words of her last song—“Singing is breathing, is thinking, is speaking…”—demanded soaring to the heights? The depth of Koko’s situation is encountered through an act of fellatio which, on the surface, seemed to imply for some in the audience a history of sexual abuse. I read it, to the contrary, as a rupture of Koko’s hermetic world. Abruptly propelled into a different space, she finds resources of compassion and forgiveness that lead her to intervene in the ritual self-harm perpetrated by the Monkivitch character.

The choice of a male to play the Jane Austen part had pluses and minuses. It allowed for Koko’s repudiation of the phallic mother in the fellatio scene but didn’t necessarily enable her to resist the circuits of patriarchal exchange within which they function as objects. But I’m afraid that Miller’s drag queen performance militated against any elaboration of this idea. This was a pity, though this richly written role has sent me off in search of Jane Austen’s letters.

Scotia Monkivitch’s hard boiled but vulnerable Hollywood diva displayed symptoms of hysteria rather than melancholia. She points this out herself when she expresses the view that Freud would have labeled all three characters hysterics. In this respect, she also appeared to be less passive than the others—the literal metaphor for her character being that the shoe doesn’t seem to fit. Monkivitch is also the most engaging performer, combining a clown’s panache with acid one-liners that cut (!) through Koko’s unremitting gravitas and the high-handed style of Miller’s Jane Austen. Her eruptive dancing with the latter evokes the sheer possibility of jouissance, of an active resistance. She is a fusion of acting and acting out. Unable to utter the void, she too is “growing a book/ tending slender pages of skin/ to replace you” (her ex-lover). Her brashness only renders her self-laceration more painful to the audience; attacking her own thighs with a knife in semi-seductive fashion negates all concepts of desire. Her most gorgeous and revealing theatrical moment occurs, however, when she comically stuffs her mouth with marshmallows. This action was prefigured when she insouciantly demanded her share of opium drops medically prescribed for her Regency counterpart.

Monkivitch’s excessively mimed bulimia is likewise prescriptive but also contains the idea of a not wholly successful attempt at self-determination. Thus there is unresolved irony as the lights fade after Koko’s apparently triumphal song. Monkivitch crouches like a cornered animal confronting the audience with her steely determination to remain hard boiled (thus untamable), at any price, unless the future manifests the kind of social revolution that legitimately grants women autonomy as subjects. There was much to admire about this brave and ambitious piece of contemporary performance despite a demonstrable need for reworking.

A Mouthful of Pins, writer Leah Mercer; director Margi Brown Ash, performers, Aole T Miller, Leah Mercer, Scotia Monkivitch, visual artist Jaqui Vial, production designer Bev Jensen, lighting designer Simon Johnson, music composed & performed by George Valenti and Moslo, songs & soundscape by Reilly Smethurst; Brisbane Powerhouse, Feb 14-16

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 38

© Douglas Leonard; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Head Under Water

AS THE GERMAN FILM INDUSTRY GROWS AND PROSPERS, THE GOETHE INSTITUT’S ANNUAL FESTIVAL OF GERMAN FILM ALLOWS CINEFILES TO KEEP TRACK OF THEMES (NOT A FEW OF THEM RECURRENT), TRENDS AND THE DEVELOPING VISIONS OF KEY FILMMAKERS. THE FESTIVAL REPORTS THAT “IN 1997 GERMANY PRODUCED 61 FEATURE FILMS, 14 OF WHICH WERE CO-PRODUCTIONS. TEN YEARS ON AND THE COUNTRY’S CINEMATIC OUTPUT HAS DOUBLED, WITH 122 FILMS BEING SHOT IN 2007, INCLUDING 46 CO-PRODUCTIONS.” THERE ARE 22 NEW FILMS IN THE 2008 FESTIVAL.

Director and novelist Doris Dörrie, who has been making confronting films since 1983, is represented by two works. In the acclaimed Hanami (2008), a man with a terminal illness suffers the sudden death of his wife and journeys to Tokyo where the cherry blossom festival provides final solace. In her 2002 feature Naked, Dorrie has two married couples play a game in which, blindfolded, they see if they can each pick their partner’s naked body: the consquences are unexpected.

Miguel Alexandre’s Border of Despair furthers the ongoing analysis of East German life under the Stasi as witnessed in last year’s controversial The Lives of Others, focusing here on a mother and her children attempting to flee to Romania. The World War II fate of Germany’s Jewish population is returned to in the Academy Award winning The Counterfeiters [director Stefan Ruzowitzky], in which Jewish prisoners are forced into currency counterfeiting. In The Edge of Heaven, German-Turkish writer-director Fatih Akin uses a pair of mature parent-child relationships to explore deeply rooted cross-cultural tensions in which prostitution and lesbianism clash with conservative norms.

Kafka High is the setting for Andreas Kleinert’s Head Under Water, something more than a black comedy about murder in a village school. Also on the teenage front, in Volker Einrauch’s The Other Boy, domineering parents and a school bully trigger unexpected behaviour from an introverted child—the result apparently divides audiences—just what you want in a good festival. Dennis Gansel’s The Wave is based on a true story from the US in 1981, transfered here to contemporary Germany, in which a school teacher created ‘a learning experience’ in fascism. It went terribly wrong, suggesting the ease with which the ideology can manifest itself.

The advance word on these films is good, promising a stimulating festival. Festival guests include leading German actor Jürgen Vogel, who appears in six of the festival’s films, emerging director Martin Gypkens (Nothing But Ghosts, one of the festival films), and leading German film writer and reviewer, Anke Zindler. RT

2008 Audi Festival of German Film, April 16-26, www.goethe.de/australia

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 26

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

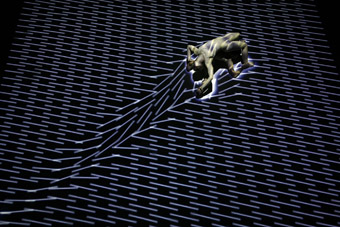

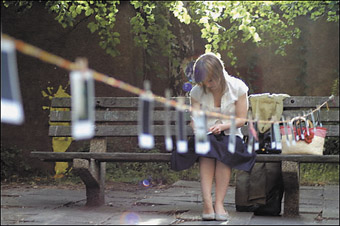

Habitat, LaborGras, Volker Schnüttgen and Frieder Weiss

photo Volker Schnüttgen

Habitat, LaborGras, Volker Schnüttgen and Frieder Weiss

FRIEDER WEISS LIVES IN NÜRNBERG AND BERLIN AND WORKS AS AN ARTS “PROBLEM-SOLVER” IN EUROPE AND INTERNATIONALLY, USING HIS INNOVATIVE VIDEO MOTION SENSING SOFTWARE TO COLLABORATE ON DANCE, PERFORMANCE, THEATRE AND INTERACTIVE INSTALLATION PROJECTS. HE HAS COLLABORATED WITH MELBOURNE’S CHUNKY MOVE DANCE COMPANY ON GLOW, NOW TOURING THE WORLD, AND MORTAL ENGINE [see article RT 81, and RT 83], WHICH PREMIERED AT THE 2008 SYDNEY FESTIVAL. DESPITE THE ONGOING SUCCESS OF GLOW, THE POSITIVE RECEPTION IN SYDNEY TOOK WEISS BY SURPRISE BECAUSE, AS HE SAYS JOKINGLY, “I’M AN ENGINEER, I’M LOOKING FOR PROBLEMS.”

From 1995 to 2006 Weiss was Co-Director of Palindrome Inter.Media Performance Group. Nowadays he works independently, collaborating with artistic partners who are interested in interactive systems. Both Mortal Engine and Glow use the Kalypso program developed by Weiss, where an image of the performer is captured using a video camera and fed into a computer. Weiss’ system relies heavily on this video capture, using infrared sensing from which it detects the outlines of the performers’ bodies and creates various visualisations and transformations.

Chunky Move, Mortal Engine

glow & mortal engine

It is this specialised software that allows Weiss to create the mesmerising imagery and interactions that characterise the Chunky Move pieces, with these complex visualisations projected back onto the dancer and stage in real time. When deciding on projects to collaborate on, the important thing for Weiss is the feel of the working environment, and he describes the relationship with Chunky Move as “a good match from the start.” With them he also found an artistic approach that was a particularly “good match” with his software systems. Artistic Director Gideon Obarzanek’s choreography often positions the dancers’ bodies close to the floor and Weiss similarly describes his technology as “getting close to the body.” With the dance floor in Glow and Mortal Engine acting as a horizontal screen, the performers can move across the whole projection area. By having the dancers close to the screen, Weiss notes that it’s much easier for audiences to focus on both the dancer and the visualisations at the same time, as opposed to performing in front of vertical projections where audiences “often watch the screen and lose the dancer.”

One of the elements that Weiss finds particularly pleasing about Mortal Engine is the way that the dancers’ bodies are accentuated not only through spotlighting, but also by darkening the stage at points where the performers are. In this way, the dancers are highlighted through “indirect light” and reflections off the floor, giving depth to the projected imagery and creating “a different kind of shadow.” This provides an interesting symmetry with some of Weiss’ previous works, which have used multi-layered visualisations to multiply and interact with performers’ silhouettes.

shadow play

Weiss created the piece Solo 4 > Three (Shadows) with Australian dancer Emily Fernandez, in which Fernandez performs in front of a single vertical screen projection. As she moves, her shadow is captured and multiplied by Weiss’ software and projected back onto the screen. This creates a layering effect of moving black and white silhouettes which appear and disappear, multiply and dwindle as the piece progresses. Weiss has recently expanded this technology with German dance collective LaborGras into a five screen installation. The flat, black and white shadows of the previous work are transformed into colour, photoreal reflections of the performers, with these images again being multiplied and layered on the multi-screen set-up. Each performance lasts for four hours (audiences can come and go) with three performers alternating in 45-minute sets of largely improvised dance, continually encountering their projected doubles (and triples), creating a combination of real and virtual spatial relations.

performative installation

Habitat, Weiss’ most recent collaboration with LaborGras, is a performance and sculptural installation piece that takes cross-disciplinary collaborations in further directions, incorporating sculpture with dance, computer-generated visualisations and virtual environments. Produced with German sculptor Volker Schnüttgen and performed at Montemor-o-moro, Portugal, in February 2008, Habitat uses Weiss’ interactive systems to facilitate more ephemeral interactions between the dancers, sculptures and the audience.

Installed within a performance space, Habitat is made up of several large, heavy oak sculptures, each with an in-built LCD screen which acts as a “virtual stage” for the performers. While the audience wander freely around the sculptures, the dancers perform the choreography in a separate space. More than simply a “live feed”, Weiss uses his Kalypso software to generate “virtual worlds” that are visible to the audience on the screens, and which the dancers can interact with in real time. Another screen in the performance space means that the dancers “can see the results they’re creating”, such as disappearing behind a wall on the virtual performance space, but remaining visible in their real location. Unlike the Chunky Move pieces, LaborGras uses more improvisation, which also elevates the possibilities of these real and virtual interactions.

Weiss is happy with the result, saying that the interactions between the performers in the real and virtual worlds were “really interesting, in some cases.” However, when asked whether the audience realised that the images were real time projections and not pre-recorded video, Weiss says “to be honest, I think 50 per cent got it without explanation.” While Weiss is continually refining his software and fixing certain issues, it is often the relationship of the audience with the technology and the performance that is most difficult to pre-empt and predict, especially in a work like Habitat when “there’s a separation between the performers and the visualisation.” More than simply a balancing act, Weiss laughs, describing it rather more frankly: “It’s a battle!” When working on such complex multi-disciplinary projects, often performed in non-traditional spaces or set-ups, the key for Weiss is to work with the possibilities and the limitations of the space and the system.

multimedia public art

The flip side to this is the unexpected successes that emerge, both in terms of the technology and audience reactions, as is the case with Weiss’ most recent public installation in Sandnes, Norway, entitled Ønskebrønn, The Wishing Well. Developed with German performance company phase7 for the 2008 European Capital of Culture, Ønskebrønn is an outdoor multimedia sculpture with a horizontal 80 square metre interactive screen. Comprising approximately 260 LED panels, the installation reacts directly to visitors’ movements as they step on and move around the panels, producing colourful and interactive visualisations. The images produced are much like those seen in Glow and Mortal Engine. However, unlike the Chunky Move pieces, which project and reflect light onto the dancers, the use of LED screens means that this installation is visually much brighter, glowing in the long Norwegian winter nights.

Not surprisingly, the challenges involved when installing the sculpture were significant and Weiss was sceptical as to whether it could succeed. As he says, the freezing outdoor conditions with rain, wind and snow are “not exactly what technology likes”, however the installation has proved a huge success with visitors and Weiss says the local community has become “a bit obsessed with it.” The city of Sandnes has held dance competitions on the installation, and if you log-on to the installation’s webcam, visitors can sometimes be seen dancing and playing in the early hours of the morning. For these reasons, Weiss describes it as one of the most fun installations that he’s done. As with Glow and Mortal Engine, he enjoys the chance to reach broader audiences, along with the ongoing opportunities of adapting his technological “tools” to the challenges (and limitations) of new artistic possibilities.

–

Chunky Move, Mortal Engine, Edinburgh Playhouse, 2008 Edinburgh International Festival, Aug 17-19

For video clips and photographs of the works of Frieder Weiss go to www.frieder-weiss.de

Solo 4 > Three (Shadows) http://www.emily.li/

I, Myself and Me Again http://www.euro-scene.de/v2/de/festivals/2007/videos/2007-hp02.php

Habitat http://www.laborgras.com/english/news/newshabitat.html

http://www.volker-schnuettgen.com/habitat/index.html

Ønskebrønnen http://watercolors.demo.coretrek.no/the-wishing-well/category178.html

http://www.watercolours.no/the-wishing-well/category187.html

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 28

© Kate Warren; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

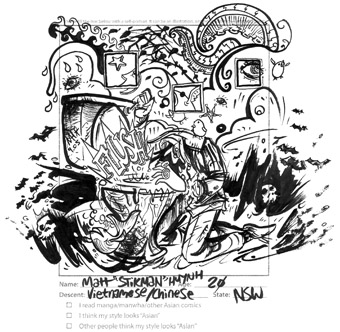

Eddo Stern, Best…Flame War… Ever (2007)

“VIDEO GAMES ARE THE FIRST STAGE IN A PLAN FOR MACHINES TO HELP THE HUMAN RACE, THE ONLY PLAN THAT OFFERS A FUTURE FOR INTELLIGENCE. FOR THE MOMENT, THE INSUFFERABLE PHILOSOPHY OF OUR TIME IS CONTAINED IN THE PAC-MAN. I DIDN’T KNOW, WHEN I WAS SACRIFICING ALL MY COINS TO HIM, THAT HE WAS GOING TO CONQUER THE WORLD. PERHAPS BECAUSE HE IS THE MOST GRAPHIC METAPHOR OF MAN’S FATE. HE PUTS INTO TRUE PERSPECTIVE THE BALANCE OF POWER BETWEEN THE INDIVIDUAL AND THE ENVIRONMENT, AND HE TELLS US SOBERLY THAT THOUGH THERE MAY BE HONOR IN CARRYING OUT THE GREATEST NUMBER OF VICTORIOUS ATTACKS, IT ALWAYS COMES A CROPPER.”

Chris Marker, Sunless

Truncated, repetitive, coin-operated nihilism? To a point. The “insufferable philosophy of our time” is not a single object or symbol, but an array of signs and symbols placed at odds with each other, made to wage a type of war we aren’t told how to engage with. We were told that play would desensitise, depoliticise and disconnect us, and now games are presented by the museum as the latest historical and contemporary cultural artefacts. So what happened?

To come to this point in proceedings exceedingly peculiar trajectories have been followed. The uneasy relationship between playful art practice and gallery culture always provided some friction, but there had always been something gauche about videogames, something beyond the pale. For over 20 years, there has been a relentless drumbeat of deferral—game art was always immature, not practical enough, too ephemeral, not critical enough. Rather than the always expected, never-mature ‘growing up’ of videogames and art, something funny happened on the way to the arcade. Games became permanently happy with their status as technological adolescents, always in the pouty, rebellious but also permanently lame zone of transition.

With very few caveats, the Australian Centre for the Moving Image has to be celebrated for its commitment to furthering the cultural capital of games. As the final months of the excellent experimentally focused Games Lab tick on, and ACMI’s transformation of the ground floor space into a screen culture antipasto takes shape, questions remain about how institutions see computer and videogames. That is, if they see them at all. There was always the threat of endorsement by government bodies becoming a stamp of legitimacy for commerce, but a happy if not always balanced path has been struck at ACMI with great effect.

This version of the monstrously popular Game On show adulterates the ever-sombre Screen Gallery with splashes of neon and carves out a tentative arcadia from what it steals from the abyss. Yet the two bookended iterations of the Game On show tell very different stories about games in galleries. In London’s original 2002 Barbican show, games and art co-existed, perhaps uneasily, but certainly in co-habitation. In Melbourne, a very different show strips back art’s presence but casually, almost without context, places game art at the literal end of the gallery space. The result is almost like a sensory prestidigitation; space designed for the element of surprise.

After a section on Australian-made games and cultural differences made playable, the visitor enters a walled-off screen room that is strangely designed to not appear at all. The ominous stone-cold lighting of ACMI’s screen gallery space has led to some amazing tricks of light in past shows, but the collection of works is being shown in the screening box of this show are like an amnesiac’s sudden flash recollection.

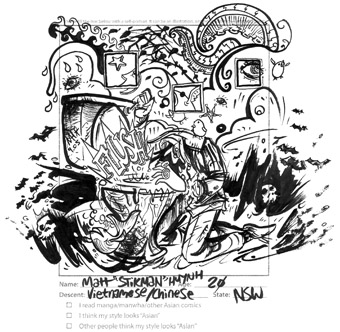

Artist Eddo Stern’s new work, Best…Flame War… Ever (2007) is the standout in this space. The video assembles faces in the style of Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s vegetable people and Jan Svankmajer’s Dimensions of Dialogue. Here, the figures are made up of World of Warcraft character models, desktop icons and other detritus. Their discussion is a monotone retelling of an internet flame war. If the principle is absurd, then the execution is a carnival. The pageantry of this work (crowns and all) demands an answer. At the literal end of the gallery, clustering together game technology, culture (and yes, commerce), arranged to tell a history, game art is positioned as the literal future of games.

It is true that ACMI’s Screen Gallery has always benefited from the sonorous secrecy of these zones, but the gamer logic of the show develops this one room like a secret area, accessible only through a ‘no clipping’ cheat.

A secret place always has aspects of a ‘removed’ existence, being a place that, physically or mentally, is created for retreat, intimacy, enclosure, screening, and protection. These often are places of power and control that cannot be known or invaded by ‘outside’ forces.

Frances Downing, Remembrance and the Design of Place

The secret place is, in actuality, the computer and videogames themselves. Growing up, they become cocoon-like and comforting in their particular idioms, capturing us in parallel zones and offering us an endless virtuality. The conflict with the art gallery was inevitable and will forever be unresolved. There are institutional and contextual tensions visible in Game On, but they are swerves rather than fractures. So how does a space—with contemporary art such as Eddo Stern’s, an independent game such as the furiously kinetic Warning Forever on a slightly grimy PC, and commercial game products such as Super Mario Kart—work? More importantly, what is it called?

Games in the gallery are asked to position themselves between a whole range of forces and bodies, to offer rules for others to play in. They are asked to bring in those who don’t usually come, while infecting them with art and thought. So on the question of the gallery, it will be difficult to imagine game art exhibitions 10 years from now being organised without reference to commerce simply because so much of the aesthetic of seriality is commerce driven. There does not need to be a corporate partner for the vast logical construct of product to rear its Pokemonic head. As Carlota Fay Schoolman and Richard Serra would say, gaming delivers players.

So Game On is the first truly major exhibition of videogame culture to come to Australia, and it is stained with all the baggage that honour provides. The subtle narrative it elicits is more timid than its international predecessors, but retains a glowing core of insight into the problems it poses. Galleries both big and small—and especially ACMI—will have to provide some answers and face up to the challenges that games provide to the categories of ‘art’, ‘commerce’, ‘the origin of the work’, and exhibition itself.

Especially important once the first major show packs up and the planning for the second takes place will be the role of the archive. How to speak about and access history has been gaming’s most difficult problem, and is it where bodies such as ACMI will potentially have the most positive impact? Game On offers some clues about how we will proceed as players, offering up art as a kind of semantic adulthood, but it is in preservation and historical framing that the show’s presence will be most keenly felt. We are already asking why we are disallowed access to our gaming past by corporate gatekeepers. The time has come for arts institutions to intervene; playtime is over.

Game On, organised and toured by the Barbican Art Gallery, City of London; Australian Centre for the Moving Image, March 6-July 13. www.acmi.net.au/game_on.aspx. The exhibition includes 125 games that can be played by visitors, taking them through the history of the form.

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 29

© Christian McCrae; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Trish Adam, HOST (video still), original cinematography Carla Evangelista

FOR CHILDREN, BEES ARE THE SUMMER TERROR OF THE CLOVER LAWN. OUT THE CAR, ACROSS THE PARK TO THE BEACH, PRICKLES ARE BAD BUT BEES ARE WORSE. (I’VE JUST CONDUCTED A SURVEY OF ALL THE PEOPLE I CAN IMMEDIATELY FIND WITHIN 20 METRES OF WHERE I’M SITTING AND THEY ALL REMEMBER THEIR FIRST BEE STING.) SO BEES ARE THREATENING, YET HERE BEES ARE, IN TRISH ADAMS’ HOST, GLIDING ABOVE AND GENTLY SETTLING ON HER UNPROTECTED HAND.

Trish Adams has previously collaborated with scientists at the University of Queensland where she worked with Associate Professor Victor Nurcombe on the transformation of her own stem cells into cardiac cells (machina carnis, www.realtimearts.net/article/issue68/7937). This time she worked with Professor Mandyam Srinivasan’s Visual and Sensory Neuroscience group at the Queensland Brain Institute. Srinivasan is famous for his work on bee vision and navigation.

[Three interesting facts about bees: 1. Bees can be trained to detect camouflaged objects. 2. Bees navigate by using the speed at which images move across their eyes—they fly down the middle of a tunnel by keeping the image speed the same at both eyes; they land by adjusting their descent speed so that the image speed at the eye remains constant. 3. Bees are lateralised in their learning, just like people are right and left handed. ]

Into the Bee House goes Adams and finds no protective suits, just your normal everyday science types, thousands of bees and an uncomfortable feeling of vulnerability. A couple of researchers, Dr Peter Kraft and Carla Evangelista, help out by filming the feeding sessions (high speed at 250fps) and providing the skills and patience needed to train the bees to feed from Adams’ hand. Film is edited, a soundscape designed (by roundhouse, www.roundhouse.tv), and the installation set up at the UQ Art Museum—a bland corporate box of a building refurbed into a gallery.

Enter through the glass doors, straight ahead to the far corner and down the stairs. Step off the stairs and a waft of honey rises up, faint, but clear. Small room, low ceiling, padded lowset bench. Sit and face the end wall/screen. Glass panel walls to the right and left shine in the darkness, recursively reflecting the far end projection. This is the installation space, quiet, intimate. Maybe two or three people can get in there without violating personal space rules. The screen shows a video laterally split between two images. One third is honey, dripping in real time, close up, luminous and golden. Two thirds are a cropped detail of hands. The hands are crossed lightly, one nestling in the other. Inside the cupped palm of the uppermost hand is the honey the bees were trained to seek. The hands are still, incredibly so, one slight thumb movement the only action. Around the hand float soft, purposeful bees, huge and close-upped, paced slow by the high speed video. They glide about, land to feed, take off, land on a finger, wait, take off again. They make no sound. It is as if the bees hover weightless above a familiar surface, collecting samples before returning to base.

And throughout are the hands and an unconditional offering of food. The bees too act without conditions, offering their labour to the continuity of the hive. The food they collect is not only for themselves but for others, just as the glistening honey in the palm is not for the palm itself and the outstretched hands are for the bees and not for the hands themselves. The artist feeds the bees, the scientists film the artist. We watch the bees, the honey and the hands. An exchange between systems. Biology.

HOST, artist Trish Adams, The University of Queensland Art Museum, Brisbane, March 6-April 6

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 31

© Greg Hooper; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

THE AUSTRALIA COUNCIL’S INTER-ARTS OFFICE NOT ONLY FUNDS PROJECTS THAT CAN’T FIND TRADITIONAL ARTFORM HOMES BUT IT ALSO ENCOURAGES VERY DIFFERENT ARTISTS TO TEAM UP AND VENTURE WHERE NONE HAVE TROD.

Artlab funding criteria require not tried collaborations but new ones; experimental, research-based and risk-taking approaches; and, if the project involves creating technologies, they must be new. It’s a tough brief requiring a strong sense of vision, teamwork and, not least, pragmatism: significant cash or in-kind contributions have to be found beyond the Australia Council’s $75,000 funding of each project in 2008. Twenty two applications sought a total of $1.5m; two succeeded for a total of $150,000.

Thinking Through the Body comprises the artists Jonathan Duckworth (artist and architectural designer specialising in the development of real time graphical environments), George Khut (artist working in the area of sound and immersive installation environments), Somaya Langley (sound and media artist), Lizzie Muller (curator and writer working at the intersection of art, technology and science), Garth Paine (sound designer, installation artist, interactive system designer) and Catherine Truman (contemporary jeweller and object-maker). The collaborators intend “investigating the use and potential of touch and movement in body-focused interactive art. The group will use a variety of body-sensing technologies to explore the possibilities of interactive art that links technical experimentation and artistic expression.”

The Transmission Project: Wheel, Water, Wind brings together Rod Cooper (hybrid instrument maker), Robin Fox (sound artist working with live digital media), Jon Rose (violinist, composer, writer and installation artist), Jim Sosnin (a specialist in acoustics, audio electronics, sound recording and computer music) and German artist Frieder Weiss [see interview] to develop “a wireless data technologies platform for designing human/machine interfaces. The team will investigate the compositional, installation and performance possibilities of the design, presenting works in progress on the themes of Wheel, Wind and Water during the testing stage of development.”

Andrew Donovan, Director of the Inter-Arts Office of the Australia Council, is pleased with the 2008 Artlab funding results. In his report he writes, “The panel was particularly responsive to projects that detailed a concise and logical research methodology, whilst clearly articulating potential artistic outcomes for the project. The panel was also responsive to applications that were genuinely collaborative in nature, reflecting the objective of the ArtLab program to nurture and support new interdisciplinary, artistic collaborations that offered the best opportunity for the development of new knowledge, artistic innovation and creative risk-taking.”

Donovan told RealTime that he welcomes the diversity of arts practitioners in each project, the range of age and experience and the geographical spread. He’s especially impressed with the number of experienced artists willing to place themselves in very new collaborative circumstances. The assessment panel, he says, were particularly taken with the research and development process embodied in the projects. “This can develop a platform—with innovations in software and hardware—to push hybridity forward, making it easy for other artists in the future to break through technical barriers.” RT

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 31

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

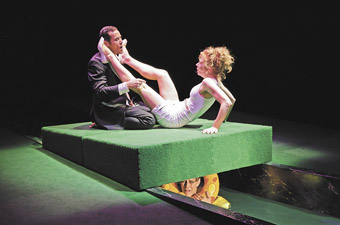

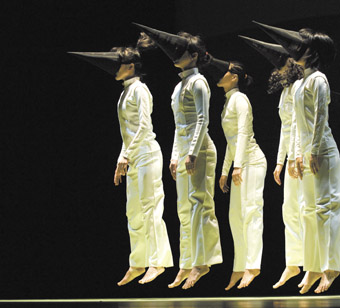

Akram Khan, Sylvie Guillem, Sacred Monsters

photo Nigel Norrington

Akram Khan, Sylvie Guillem, Sacred Monsters

TIME STANDS STILL IN THE MOST INTERESTING WAYS IN EMBRACE: GUILT FRAME. BECAUSE THE PERFORMANCE BALANCES ON A PIVOT OF STILLNESS AND EXTREMELY SLOW MOVEMENT, THERE’S INEVITABLY A PICTURE-LIKE QUALITY TO THE WORK ENHANCED BY THE ACTION BEING RESTRICTED TO A SMALL GILT FRAME THAT LIMITS OUR VIEW TO THE HEADS AND UPPER TORSOS OF TESS DE QUINCEY AND PETER SNOW. IT’S THE TIME OF THE ART GALLERY, EXCEPT THAT YOU CAN’T MOVE ON AFTER A FEW MINUTES OF VIEWING. YOU STAY STILL; THE PICTURE KEEPS CHANGING FOR SOME 50 MINUTES.

What we see pictured remains peristently enigmatic, always suggestive, of individual emotional and physical states, possible relationships, the history of painting even—such is lighting designer Travis Hodgson’s subtle texturing and profiling, his shifts in depth of field, evoking Carravagio, Vermeer, Rembrandt and more.

De Quincey and Snow work their way through a set of states common to The Natyashastra (an ancient Indian text) and Body Weather (the contemporary Japanese movement discipline; see RealTime 83, page 45 for an interview with De Quincey) but never literalise them. A smile is a smile, a grimace a grimace beneath which might be ecstasy or anger. But it’s the slow unfolding of these states that compels one to look for complexities, tensions, shared pleasures, changes in mood. Humans enjoy peering at portraits, painted or photographed, as if endlessly rehearsing primordial encounters with strangers in our evolutionary development. Embrace: guilt frame allows us to read faces with a rare intensity, registering tiny details, forming impressions, re-evaluating, never resolving. It’s a peculiar pleasure made palpable by disciplined performers who ease themselves into a temporal state slower than our own and invite us in.

But there’s more to embrace: guilt frame than faces—radical if slow changes in perspective, supple tonal shifts and endless evocations. There are moments when the performers lean out of the frame towards us, or recede into its deep dark interior; a moment when de Quincey turns ever so slowly, low in the frame, only her head, its back to us, providing support—it looks simple but must require great strength. There are moments that appear Gothic—the prolonged shudder in the residue of a laugh, Snow’s shaded face appearing to fatten with anger. There’s the suggestion of a grim puppet show—de Quincey’s head lolling like a fallen Punch. There’s a rare moment of touch, electric when it happens, other moments of apparent adoration or deep suspicion that suggest a relationship dancing in and out of sync.

Composer Michael Toisuta’s score operates at another level, a reminder with its persistent pulse of time manufactured and multiplied. Inspired by Ligeti’s Symphonic Poem for 100 Metronomes (1962) this surround sound creation is enveloping and some of its more dramatic changes in pace sharply re-shape the mood of the performance. There’s no sense, however, that de Quincey and Snow perform to it; it’s simply there with them; its time is not theirs.

Embrace: guilt frame is a small, intense work by skilled performers in a tiny theatrical frame that enlarges both our sense of time and of how driven we are by our visual curiosity.

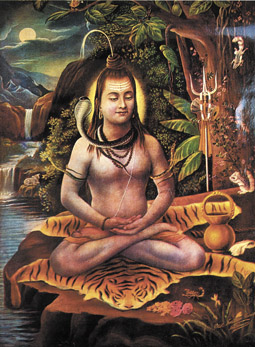

The Akram Khan-Sylvie Guillem duet, Sacred Monsters, is a very different experience, but it also has its roots in ancient Hindu culture and it too suspends our sense of time, if speed is more often its means than stillness. The work is very much framed by Khan’s story about himself as a young man wanting to play the god Krishna, but disappointed that he was too short and already losing his hair. He would find his way, he said, by finding the monster in himself, and that monster may well have been his meeting with modern western dance. By the end of Sacred Monsters he appears to have achieved the release and transcendance he has desired, but in a remarkable duet, not just his agonised solo—the god in many, not one.

There is therefore a very strong sense of release in this work. The initial image is of a still, chained Guillem, whom Khan soon frees. He then removes the long chains wrapped around his calves, hidden beneath his trousers, but heard jangling musically in the dance. Towards the work’s end, Guillem gently touches Khan’s bowed head as if investing him with godliness. Although Sacred Monsters largely comprises duets, each performer, while sitting, sipping water, wiping away sweat with a towel, intently watches the other’s solo. There’s a potent sense of mutual support and release.

There’s also a great sense of playfulness, of gentle mockery and brattishness in the dialogue. But the dancing expresses darker tensions between these divas (‘sacred monsters’ is the translation of the 19th century French term for ‘stars’) as they strike at each other, reeling from the impact before being actually hit, as if the work they had created together has been a battle. At separate points in Sacred Monsters, one falls prey to the other, flattened, left limp…ready to airily chat with us and move on. The informality is heightened by the musicians (providing another East-West dynamic) sitting on stage with the performers and the female singer moving around the dancers.

A critical point occurs when Khan sits upstage quietly uttering, “Is this right?”, “Just an experiment!”, as if querying and asserting his melding of ancient and modern traditions. Moving forward on his knees, torso low to the floor, almost abject, his delivery becomes more urgent. His right arm shoots out and withdraws. Suddenly he thrusts his body up, almost erect, suspended, before falling to the floor and moving even more urgently forward again reporting the action. It’s an astonishing and painful dance. And crucially it’s followed by the pivotal duet of Sacred Monsters where Guillem straddles Khan, hip to hip, face to face. She leans back and they become one, an eight-limbed god in a dance of astonishing strength, sensuality and passion, their hands flickering their own finely articulated dance. Krishna.

Khan and Guillem languidly mop the floor with their towels (it’s your sweat, she mocks), preparing for a final, very earthed celebratory dance. Sacred Monsters is a wonderful collaboration, a fine conjuction of styles, traditions and personalities. Guillem’s stories are less elemental than Khan’s, less revealing, but wry and witty, reinforcing the embracing casualness of the show’s chatty framework (audible, if not always, in a concert hall bedecked with extra curtaining to damp the resonance). Her dancing, however, is almost beyond description, long lined and fluent, capable of breathtaking moves, like the reverse flip where her feet seem to barely leave the ground one after the other, and the ease with which she meets the speed and weight of Khan’s lower-placed centre of gravity. Sacred Monsters is a work of reflection and cross-cultural kinship, movingly and bracingly performed with great passion and remarkable skill.

–

Sydney Theatre Company, Wharf2Loud, embrace: Guilt Frame, created and performed by Tess de Quincey and Peter Snow, original concept Tess de Quincey, set designers Russell Emerson, Steve Howarth, construction by erth, lighting designer Travis Hodgson, sound designer Michael Toisuta; Richard Wherrett Studio, Sydney Theatre, Feb 27-March 9

Sacred Monsters, artistic director, choreographer Akram Khan, dancers Akram Khan, additional chorography Lin Hwai Min for Guillem, Gauri Sharam Tripathi for Khan, composer Philip Shephard, lighting Mikki Kunttu, set design Shizuka Hariu, costumes Kei Ho; Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 32

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

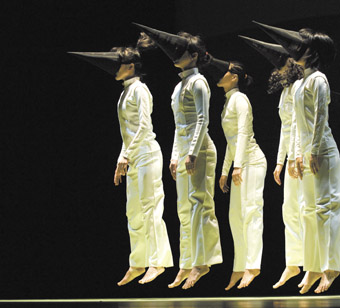

Dance Theatre ON, Ah Q

photo Choi YoungMo

Dance Theatre ON, Ah Q

THE DANCE PROGRAM OF THE 2008 SINGAPORE ARTS FESTIVAL IS PARTICULARLY STRONG, NOT LEAST IN THE WAY IT MORPHS INTO THE THEATRE PROGRAM WITH SOME FASCINATING HYBRID CREATIONS.

In Amjad, choreographer Édouard Lock and Canada’s La La La Human Steps challenge romantic ballet in the shape of Swan Lake and Sleeping Beauty. Lock was born in Morocco where Amjad, a name for children both male and female, means “greater glory”—the choice of title suggestive perhaps of Lock’s desire to transcend the inherent violence of gender divisions, not least in classical ballet. He requires of his company both ballet skills and hard-edged, fast contemporary dance.The multimedia set is by French-Canadian sculptor Armand Vaillancourt and the music mix comprises works by Gavin Bryars, David Lang, noise artist Blake Hargreaves and, of course, Tchaikovsky.

Romanian Edward Clug is the house choreographer and head of ballet at the Slovene National Theatre in Maribor, Slovenia’s second largest city. His Radio and Juliet is Romeo & Juliet performed to the music of Radiohead and tells the tragic tale in reverse. In another major work, The Architecture of Silence, Clug choreographs his company as fish-like dancers in virtual waters to contrasting requiems by Mozart and contemporary Polish composer Zbigniew Preisner (who scored films for director Krzystof Kieslowski). This epic production features 45 dancers, 80 singers and the Singapore Festival Orchestra.

In Japanese artist Nibroll’s No Direction, an exercise in miscommunication and an argument against homogenisation, eight performance artists “haphazardly inhabit a grid on stage, absorbing each other’s idiosyncracies and sporadic urges in a continuous interplay of music, movement, and visual images.” What began as an installation for Tokyo’s Metropolitan Museum of Photography has become a major performance work with the multimedia collective formed in 1997 by Yanaihara Mikuni. No Direction is dance and much more.

In Ah Q, South Korea’s Dance Theatre ON employs the Quixotic character from Luxun’s novel The True Story of Ah Q to explore the effects of ignorance and foolishness. Choreographer Hong Songyop’s productions are well known for their rich symbolism and surreal effects in their ventures into the psychological interior.

In the festival’s theatre program dance makes some intriguing appearances. In For all the Wrong Reasons, a collaboration between Belgium’s Victoria and the UK’s Manchester-based Contact, leading experimental theatre director Lies Pauwels addresses stupidity. The setting is a faded end-of-the-pier revue, the performace a set of dances, songs and confessional monologues replete with sheer silliness and moments of profundity (you can enjoy a delicate if bizarre dance segment on the festival website).

In Nine Hills One Valley, dancer-director-designer Ratan Thiyam and the Chorus Repertory Theatre of Manipur celebrate the traditional dance, theatre and other cultural forms of the remote regions of Manipur in eastern India, but they also lament the passing of these ancient and often interdisciplinary arts. Although not dance-based, Awaking, a new interdisciplinary work from Ong Keng Sen and TheatreWorks with contemporary Chinese composer Qu Xiao Song, looks to the literature, theatre and music of the past in very different cultures. Awaking addresses love through the works of Shakespeare and Ming Dynasty poet and playwright Tang Xian Zu, of Peony Pavilion fame. Both writers died in 1616. The performance features the Singapore Chinese Orchestra; the Musicians of the Globe led by Philip Pickett; and the kunqu opera actress Wei Chun Rong and her musicians from the Northern Kunqu Opera Theatre in Beijing.

The festival also includes Forward Moves, commissioned works from three female Singaporean choreographers: Ebelle Chong, Neo Hong Chin and Joavien Ng. Continuum from the Singapore Dance Theatre presents the Asian premieres of Evening by Graham Lustig (USA), The Grey Area by David Dawson (UK) and Glow-Stop by Jorma Elo (Finland).

On the experimental theatre front, Singaporean visual artist and filmmaker Ho Tzu Nyen [RT80, p54] and co-director Fran Borgia have been commissioned by the Singapore Arts Festival and Brussel’s Kunstenfestivaldesarts to create The King Lear Project: A Trilogy. The three productions, played over three days, work from well known critical essays on Shakespeare’s tragedy, realising them as audition, rehearsal and post-show discussion, worrying at the right way to stage the great work.

As for Australian content, in the 2008 Singapore Festival Geelong’s Back to Back Theatre continue on their quiet path to world domination with the remarkable Small Metal Objects. RT

The 2008 Singapore Arts Festival. May 23-June 22, www.singaporeartsfest.com

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 33

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Pilobolus

photo John Kane, courtesy of the Joyce Theatre

Pilobolus

IN A 2005 ARTICLE IN THE NEW YORKER ON WHAT SHE SAW AS A SURREALIST REVIVAL IN DANCE IN DOWNTOWN NEW YORK, CRITIC JOAN ACOCELLA IDENTIFIED PILOBOLUS AS ONE OF THE PIONEERS OF THE MOVEMENT WHICH MORE RECENTLY HAD BEEN TAKEN UP BY CHOREOGRAPHERS LIKE TERE O’CONNOR AND FORMER MEMBERS OF HIS COMPANY INCLUDING UP AND COMING CHOREOGRAPHER/PUPPETEER CHRISTOPHER WILLIAMS. SHE EXAMINED CHUNKY MOVE’S TENSE DAVE, TOURING NEW YORK AT THE TIME, IN THE SAME SURREALIST LIGHT.

Taking its name from a sun-loving fungus, Pilobolus emerged in 1971 when a group of dance students at Dartmouth College interested in “a collaborative choreographic model and a unique weight-sharing attitude to partnering” decided to form a company. Pilobolus is still a deeply collaborative entity with three artistic directors and the company’s seven dancers all contributing to the repertoire. Merging dance and biology into an inventive and eloquent physical vocabulary, this is also a company with a mission “to use their organization and creative methodology to stimulate, educate and expand the audience for dance through innovation, collaboration and public service.”

Pilobolus is visiting Australia for the very first time in May, performing a five-work show in the hotbed of Adelaide Festival Centre’s variegated dance program, Pivot(al), including Day 2, set to the music of Brian Eno and Talking Heads which “captures the awe of evolution and the wonder of existence.” Let’s hope there’ll be time while they’re here for a little cross-pollination of ideas on artistic sustainability.

Speaking of survival, Dean Walsh is a highly accomplished Australian dancer/choreographer who has been evolving his own idiosyncratic body of work over a decade and, at the same time, performing with companies such as Australian Dance Theatre, DV8 Physical Theatre in the UK and No Apology Company in Amsterdam.

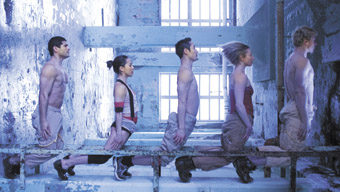

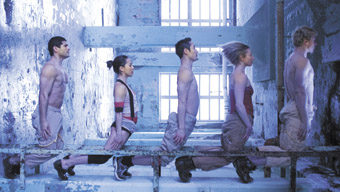

Dean Walsh’s Back From Front

photo Heidrun Löhr

Dean Walsh’s Back From Front

Walsh’s new work, Back From Front premiering at Performance Space in May, draws on stories from veterans of World War 2 through to the Iraq conflict. Walsh defines this as “a piece about the lingering impact of wartime experience on soldiers and their families—from the immediate challenges of re-adjusting to post-war life, to the continuing cycles of violence that can penetrate families for generations to come.”

Clearly referencing the territory of some of Walsh’s earlier, intimate solos, Back From Front is his first large-scale group work. With a strong cast and a team of production collaborators (including John Levey, Rolando Ramos, Simon Wise, Nikki Heywood) the work combines video imagery with lighting and movement.

Elizabeth Ryan, Jane McKernan, Emma Saunders, The Fondue Set, No Success Like Failure

photo Irèn Skaarnes

Elizabeth Ryan, Jane McKernan, Emma Saunders, The Fondue Set, No Success Like Failure

Adaptation is what it’s all about for The Fondue Set (Elizabeth Ryan, Jane McKernan, Emma Saunders) and if their new work sounds a bit ‘under’ as they say on So You Think You Can Dance, it’s intentional. For a while now this talented trio has been performing serious experiments—taking dance apart and trying to put it back together in some semblance of order—while simultaneously masquerading as good time girls. In No Success Like Failure, their collaboration with the idiosyncratic UK choreographer Wendy Houstoun, they have distilled hours of serious experiment into an intriguing evening of performance in which they’ll be “lying, dying, singing, trying and trying again.” And as if that weren’t enough they also promise “motivational dancing, negative cheering, successful snoring, hypnotism, word bingo and more!”

Sara Black, Dance Like Your Old Man, Chunky Move

The highly adaptive hybridiser Chunky Move, working across dance, film and interactive media, is currently thriving with the international suucess of Glow and now an invitation to stage their Mortal Engine at the 2008 Edinburgh International Festival. In works like Singularity and I Want to Dance Better at Parties, the company has also been evolving a repertoire of choreographic works that intersect with everyday movement. In the film Dance Like Your Old Man, Gideon Obarzanek and Edwina Throsby’s joyous and thoughtful 10-minute dance documentary, six women do just that, proving once and for all the power of body memory. As they recall their moves, the women also remember the men who made them (in more ways than one). With this film the company has collected a couple more trophies, namely the 2008 ReelDance Award for Best Dance Documentary and Best Documentary at this year’s Flickerfest Short Film Festival. RT

–

Pivot(al), Pilobolus, Her Majesty’s Theatre, May 6-10, www.adelaidefestivalcentre.com.au; Dean Walsh, Back From Front, Performance Space at CarriageWorks. May 1-10, www.performancespace.com.au; Fondue Set, No Success Like Failure, The Studio, Sydney Opera House, June 4-8, www.sydneyoperahouse.com; Campbelltown Arts Centre, June 12-14 June; Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall, August; Chunky Move, Dance Like Your Old Man, Reeldance 2008, www.reeldance.org.au; Chunky Move, Mortal Engine, Edinburgh Playhouse, 2008 Edinburgh International Festival, Aug 17-19

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 33

© RealTime; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ningali Lawford-Wolf, Margaret Mills, Kelton Pell, Tony Briggs, Jimi Bani, Jandamarra

photo Gary Marsh

Ningali Lawford-Wolf, Margaret Mills, Kelton Pell, Tony Briggs, Jimi Bani, Jandamarra

AFTER A ROCKY PREMIERE, JANDAMARRA BECAME A SUPERB WORK OF EPIC THEATRE, AKIN TO NEIL ARMFIELD’S CHEERY SOUL (1993) OR CLOUDSTREET (1998). DIRECTOR TOM GUTTERIDGE ECHOED ARMFIELD BY FILLING THE WINGS WITH PARTIALLY VISIBLE INSTRUMENTS, WIND-MAKERS, AND OTHER THEATRICAL MACHINERY WITH WHICH THE OFFSTAGE ACTORS VOICED THE ACTION. WITH ELDERLY INDIGENOUS SINGER GEORGE BROOKING SEATED BEFORE A MICROPHONE, THIS GAVE A SENSE OF MEMORY, BREATH AND RITUAL TO THE WORK, BRINGING THE ACTORS, FORMS AND HISTORIES TO LIFE.

Zoe Atkinson’s design for Jandamarra consisted of cliff panels—parting to reveal a vulva crease into which the protagonist stalked—bounded below by a sandpit from which set elements emerged or into which they were planted (fires, trees, graves). Platforms atop enabled split level performance, languid Indigenous scenes floating above tense European exchanges. Also remarkable was how Atkinson’s crinkled surfaces, projections of translations and Indigenous animations turned the space into a worn chapbook onto which histories and dreams were screened.

Jandamarra tells the story of the eponymous Aboriginal resistance leader in the Kimberley region in the 1870s, focusing on his complicated standing with whites and his own people. Never formally initiated into his clan, Jandamarra was befriended by the sporadically ruthless Constable Richardson before killing him and leading the Bunuba people against the graziers. The Bunuba attributed Jandamarra’s prowess to his magical skills, redefining him from tribal outcast to a key figure in their mythos.

Steve Hawke’s script was compiled with the traditional owners and Jandamarra’s story is portrayed in environmental terms above those of race or war. Jandamarra becomes one who, even without initiation, could read the land’s pain and recognise those waterholes which neither Bunuba nor white should disturb. Eventually, Jandamarra claims he fought not to defend his people per se, but the land itself. Although subplots involve black-white relations—notably the awkward reconciliation between the placeless station-owner’s widow and Jandamarra’s mother—the play comes across as somehow apolitical, being more about issues of the natural rather than racial oppression and armed resistance. It’s hard to imagine depicting the Irish resistance to English farming after 1600 in similar terms, despite the significance of Indigenous land use to both.

This recasting of identity in spiritual terms also characterised Tero Saarinen’s Borrowed Light. The Finnish choreographer drew on that American modernist archetype the Puritan sect, the Shakers. Together with the Amish, the Shakers’ austerity in their much collected furniture and quilts was central to 20th century American aesthetics, influencing architects (Frank Lloyd Wright’s furnishings), composers (Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring, written for Martha Graham) and dancers (Doris Humphrey, Twyla Tharp and Graham all produced Shaker pieces). The dialectic between Protestant restraint and the ecstatic seizures of devotees to such 19th century US ‘campfire meetings’ fascinated choreographers from Mary Wigman to Ruth Saint-Denis. Despite the hostility of these sects to modernism (the Amish do not drive) and social norms (the Shakers are celibate), they were central to post-WWII America’s self-definition as a streamlined, modern, yet lyrical, nation.

Saarinen sets aside these national references but embraces a nostalgia for disciplines of physical and emotional frugality and the tragedy of their loss. Borrowed Light is a hymn for a lost idea of what modern art was. Amidst the sustained simplicity of a choir (the Boston Camerata) singing Shaker hymns, Saarinen’s dancers twist and sway in unison (recalling Wigman’s “choric dancing”) before succumbing to individual contortions and an emptying out of the body via tension and release.

Bodies begin as trapezoids, with wide stompy legs (emphasised by the men’s black robes and the women’s dresses) rising to a dynamic torso. This alternates with expansion of the chest outward with arms not just flung back but curled into neurotic filigrees. Saarinen’s work is dramatically classical in its precision and sculptural form, yet its grotesque details recall butoh. The design also echoes Euro-American modernists, notably Adolphe Appia and Edward Gordon Craig, who advocated tides of directional white light between rising stairs to create a hierarchical space for the individual to strive for his or her spiritual ascent. Bounding the space, these flights and levels (differentially tinted black, grey and white by Mikki Kunttu) become a parable for the dancers’ terrestrial embodiment and their eternal striving, through and of the body, to free themselves. As dancers collapse and drag themselves across the space, the insufficiency of modernist ecstasy—as well as its joy—is performed.

A different sensibility is found in the work of Chrissie Parrott and Jonathan Mustard. Each piece in their trilogy, Metadance in Resonant Light, includes projection: animated figures in Recording Angel and Metadance, computer code in Metadance, and noirish Expressionism alongside the black-bobbed women of Split. Film noir is the dominant style in the latter, a duet supported by video showing dancers silhouetted in doorways. Head shots also feature, with hair swirling about visages, obscuring personalities even as they are suggested. Split evokes a house of memory and angst, affectively placing it in a predigital realm. This is further enhanced through haunting, aged-sounding music by Set Fire To The Flames. Split is animated by doppelgangers—the women’s other selves, and their struggle against their own otherness; femme fatales of their own desire. While similar to In Absentia (1997) by Sandra Parker and Margie Medlin—another work evoking uneasy memories through projection—Parrott’s work is more dramatic, with suggestions of specific (if opaque) characters.

Metadance

photo Jon Green

Metadance

Metadance has four dancers within a sea of floating and spinning text which codes music and avatars. As with Merce Cunningham’s Biped (1999), Parrott uses the X-Y-Z coordinates so generated to devise the choreography. Nevertheless, the movement remains recognisably hers. Hidden amongst translucent screens bearing rows of letters and grids, dancers under spotlights mark a constrained area with taught precision and line. Full limb extensions are common. Although each body often crouches low with one leg moving out at 30 degrees under the hips while the other bears the weight, aggressive twists or bends are rare. The dance retains Parrott’s sense of lyric control and clarity. Mustard’s music is less characteristic, departing from his 1980s MIDI palette to create a weft of ringing metallic strikes echoing away eternally, radiophonic quotations (a French vaudeville song for the juggling interlude, complete with projected balls), shuddering percussive fields and whining tones.

Recording Angel is the most impressive of the trilogy, simplifying and extending Metadance. Dancer Joshua Mu perches, birdlike, head down, arms spread, barely visible under tints of blue, posed beside his virtual double. The separation between live performer and avatar is blurred, both defined by slight glows within an ill-defined space. The measured choreography also imparts a sculptural feel, challenging not only distinctions between body and projection but dance and installation. It is often hard to see the movement. This is combined with Martin Tellinga’s music, recorded so well that, even in stereo, it sounds like its windy sheets and angry shimmering textures are charging behind us. Beyond narrative, meaning, or choreographic or dramaturgical evolution, Angel is a durational, experiential piece, affectively holding spectators in a profoundly sensual yet indeterminate fashion. As such, it avoids clichés of oscillating between technological visions of Frankensteinian disaster or naïvely utopian transcendence, to suggest a state neither liberating nor oppressive, yet intensely affective.

Perth International Arts Festival 2008: Black Swan Theatre Company with Bunuba Films, Jandamarra, writer Steve Hawke, director Tom Gutteridge, associate director, performer Ningali Lawford-Wolf, musical director Paul Kelly, designer Zoe Atkinson, lighting Andrew Lake, projected animations Kaylene Marr, Clancie Shorter, performers: Margaret Mills, Jimi Bani, Geoff Kelso, Emmanuel Brown, Tony Briggs, George Brooking, Simon Clarke, Peter Docker, Danny Marr, Kelton Pell, Dennis Simmons, Kevin Spratt, Sandra Umbagai-Clarke, Perth Convention Centre, February 9–23; Tero Saarinen Company and the Boston Camerata, Borrowed Light, choreographer, performer Tero Saarinen, musical director Joel Cohen, design & lighting Mikki Kunttu, costumes Erika Turunen, sound Heikki Iso-Ahola, His Majesty’s Theatre, Feb 27–Mar 1; Metadance In Resonant Light, choreography Chrissie Parrott, lighting/projection Jonathan Mustard, performers Joshua Mu, Sharlene Campbell, Sally Blatchford, Jacqui Claus. PICA, February 14–21

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 34

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Chris Ryan, Meredith Penman, Chekhov Re-cut: Platonov

photo Jeff Busby

Chris Ryan, Meredith Penman, Chekhov Re-cut: Platonov

THE ANXIETY OF INFLUENCE, TO HIJACK HAROLD BLOOM’S TERM, IS PROBABLY MOST EVIDENT WHEN IT BESETS AN EMERGING DIRECTOR. YOU KNOW THE SORT—THE YOUNG TURK WHO WANTS TO REINVENT THEATRE, BREAK THE MOULD, SHAKE OFF THE SHACKLES OF AN ARTFORM OSSIFIED INTO RIGID PREDICTABILITY. OFTEN THE RESULT IS A LAMENTABLE MESS THAT MERELY ENDS UP IMITATING OTHER REBELLIOUS THEATREMAKERS WITHOUT BEING CONSCIOUS OF THE TRADITION BEING FOLLOWED. SOMETIMES, THOUGH, THE DELICATE BALANCE BETWEEN AN ORIGINAL VISION AND AN AWARENESS OF HISTORICAL TRADITION MAKES FOR SOMETHING GENUINELY NEW AND EXCITING.

Matthew Lutton and Simon Stone are both 23-year-old directors who have arrived on the stage from different directions. Lutton studied in a now defunct cross-disciplinary program at WAAPA before going on to establish his own theatre company and working as an associate director with Black Swan. Stone, on the other hand, comes from an acting background—the VCA grad’s self-formed company The Hayloft Project features many of his old classmates. And though they evince very contrasting aesthetics, both directors are proving capable of rubbing shoulders with theatre veterans twice their years.

Marcus Graham, Alison Whyte, Barry Otto, Tartuffe

photo Jeff Busby

Marcus Graham, Alison Whyte, Barry Otto, Tartuffe

malthouse’s tartuffe

Lutton stepped in to direct Malthouse Theatre’s first 2008 production, Tartuffe, at (quite literally) the last minute. The assistant director was informed on the first day of rehearsals that Michael Kantor was handing over the reins in order to undergo medical treatment for a coronary irregularity. It’s testament enough to a certain amount of sheer gumption, I suppose, that Lutton didn’t baulk at the announcement but set to work. And though Kantor’s own artistic imprint is still visible in the final work, Lutton brings enough creative license to the piece to finally make it his own.

Tartuffe is freely adapted by Louise Fox after the Molière play of the same name. Where the original was a satirical swipe at the hypocrisy of organised religion and the greed of the aristocracy, Fox’s version is a bawdy, carnivalesque skewering of contemporary Australian mores and misdemeanours. Marcus Graham plays the titular holy roller who infiltrates a wealthy, soulless Toorak family and profits from their moral bankruptcy and desire for the kind of spiritual satisfaction only money can buy. Barry Otto and Alison Whyte are the heads of the vacuous clan, and this trio makes up the central dynamic of the piece.

Lutton’s version pushes the comedy to suitably manic extremes. Like any good sit-com there’s rarely a line that isn’t some kind of gag or a moment without some physical foolery. He makes the most of a lavish set, complete with a long lap-pool, three-level balcony edifice and numerous trapdoors. But where a lesser work would simply devolve into zany clowning and frothy farce, this Tartuffe outdoes itself in a final directorial choice near the work’s end. In Molière’s original, the sudden, improbable intervention of the King neatly resolves the tale. Translating this into a more interesting contemporary parallel was always going to be difficult, but Lutton’s decision is a stroke of brilliance. Where much of the production is an hysterically amplified take on the real world of today, Lutton’s Tartuffe climaxes with the hilarious entrance of Jesus in robes and beard, arriving to set all aright. Rather than undoing the cop-out of Molière’s deus ex machina ending, Lutton turns it up a notch to go beyond satire into something approaching meta-theatre, exposing its own internal cracks as much as those of the flawed characters it has so far ridiculed.

hayloft’s platonov

Simon Stone’s Chekhov Re-cut: Platonov takes the early work by the canonical playwright and treats it with the irreverence one would expect from an emerging talent. This is only Stone’s second production—the first, Spring Awakening (to be seen in June at Belvoir Street in Sydney), was an equally riveting work, and Platonov continues his trajectory. It cuts and shuffles Chekhov’s sprawling five-hour play to less than half that. It updates the setting, to a point, to lend it both a contemporary relevancy and a generous respect for its source. And, visually, it’s a beautiful gift to its audience.

Platonov is a liberal misanthrope, an existentially despairing tragic who turns his bleak desolation on the humans around him. Numerous affairs and betrayals seem to entertain his love of power games, but when the precarious house of cards he gradually builds brings about his ruin the audience must ask whether this self-destruction was in some way willed. He’s certainly not a sympathetic figure at any turn, but he is a fascinating one.

In Stone’s hands Platonov, like Spring Awakening, is very much an actor’s piece. The performers are given full rein to explore and embellish characters with gusto, and each proves more than capable. There’s plenty of stage business making full use of the space, but this adds a tactile dynamism and energy to the work rather than appearing contrived or unnecessary. With the exception of a superfluous second-half opening in which the feverish Platonov is beset by a ghostly chorus of his peers, the production aims for heightened realism instead of heavy-handed symbolism or obvious directorial intrusion. Most encouraging of all, it’s a realism that meshes perfectly with theatricality, too often seen as exclusive opposites.

Evan Grainger’s set is a sure contender for a swag of accolades. The entire playing space is flooded with black, rippling water fringed by shattered and burnt walls; piles of mouldy books and decaying antique furniture jut from the water like lilies. A subtle lighting design creates a warm and cloying sense of brooding intimacy which shimmers as the performers wade, splash or retreat from the pool.

Simon Stone, like Matthew Lutton, displays a powerful ability to reinvent an old work, making that reinvention the point of the exercise. Both bring an understanding of and respect toward their respective sources while remaining unafraid to depart from them in order to produce a superior work. Are you paying attention, class?

Malthouse Theatre, Tartuffe, writer Molière, adaptation Louise Fox, director Matthew Lutton, performers Laura Brent, Marcus Graham, Francis Greenslade, Peter Houghton, Rebecca Massey, Barry Otto, Ezekiel Ox, Luke Ryan, Alison Whyte, designer Anna Tregloan, lighting designer Paul Jackson, composer Peter Farnan; CUB Malthouse, Feb 15-Mar 8; The Hayloft Project, Chekhov Re-cut: Platonov, writer Anton Chekhov, adaptation, direction Simon Stone, performers Jessamy Dyer, Amanda Falson, Angus Grant, Adrian Mulraney, Eryn-Jean Norvill, Meredith Penman, Chris Ryan, Simon Stone, designer Evan Granger, lighting design Danny Pettingill, sound Jared Lewis; The Hayloft, Footscray, Melbourne Feb 27-Mar 16

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 36

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Alex Grady, Matthew Prest, The Whale Chorus

JANIE GIBSON’S THE WHALE CHORUS IS MYSTERIOUS AND CHAOTIC, A DREAM MUTATING INTO NIGHTMARE AMBIGUOUSLY HOSTED BY A YOUNG WOMAN (GIBSON) IN DARK WEIMAR CABARET PERSONA, ACCENT AND ALL, A SET OF TRULY EERIE TALES AND, IN THE CLIMAX, SPECTACULARLY STAGED SUPERNATURAL POWERS OUT OF THE MATRIX AND THE RING CYCLE.

Two competitive young men (Matthew Prest, Alex Grady) prance about like centaurs, revealing their love-lorn inner states via intensely delivered pop songs; two women (Phoebe Torzillo, XX) engage in more gnomic behaviour, sometimes gratingly cute but also tinged with dark prophecy.

Like the vigorous, ambitious ensemble dancing, the production constantly threatens to fall apart. Save for Gibson’s disturbing, blackly comic tales the writing is thin, the other female roles limited and the production’s grand symbolism opaque.

As a director Gibson is courageous, her vision reminiscent of Melbourne playwright Lally Katz’s anarchic theatrical magic but, unfortunately, there’s little sense of The Whale Chorus being through-written. Nevertheless the production proved oddly memorable. Alex Grady is a subtle presence, Gibson has a magnetic, quiet intensity, and Prest a vibrant nervous energy. Above all it was exhilarating to see a young ensemble performing with total commitment.

The Whale Chorus, director Janie Gibson, performers Alex Grady, Matthew Prest, Phoebe Torzillo, XX, Janie Gibson, sound James Brown, costumes Lucy Thornett, magic maker Michaela Gleave, lighting designer Frank Malnoo; PACT Youth Theatre, Sydney, Feb 28-March 9

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 36

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

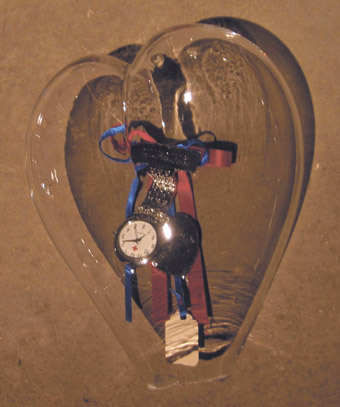

REACH INTO YOUR POCKET AND BRING OUT YOUR WALLET. YOU DON’T RECOGNISE THIS WALLET. REACH INTO YOUR BAG AND BRING OUT YOUR MOBILE PHONE. YOU DON’T RECOGNISE THIS MOBILE PHONE. LOOK AT THE NAME ON THE PIECE OF PAPER YOU’RE HOLDING. YOU DON’T RECOGNISE THIS NAME. IS THIS A NIGHTMARE OF LOSS OR A FANTASY OF FREEDOM? EITHER WAY, IT WAS THE EXPERIENCE OF PARTICIPANTS IN LIFE EXCHANGE, A PROJECT ORCHESTRATED BY BERLIN-BASED ARTISTS WOOLOO PRODUCTIONS.

Between October 31 and November 6, 2007, 10 people were sent blinking into the streets of New York with just a stranger’s possessions to guide them. Martin Rosengaard and Sixten Kai Nielsen, of Wooloo Productions, interviewed participants who were each willing to swap lives with a stranger and matched them into pairs. The longest exchange took one week; the shortest was 24 hours.

Surely you’d have to be crazy to trust a stranger with your house keys, your credit card, your job, your relationships? Participants didn’t just swap material possessions but also met each other’s lovers, worked in each other’s jobs and (although not in all cases) lived in each other’s homes.

For some, this demand for trust might seem like a nightmarish risk, but Rosengaard says it is one of the project’s strengths. Particularly in America, he says, there is a “performance of distrust” carried out by the state, which encourages people to be suspicious of each other’s motives and exploits an inherent conservatism of fear. In contrast, Life Exchange invited a very un-public display of trust and openness.

In fact, the relationship between two strangers was not the central experience of Life Exchange—after all, they didn’t really meet. One participant, occupying the life of Guilio d’Agostino for a day, found himself flirting with a woman on the subway. Twenty-four hours later he had returned to his identity of Ektoras Binikos, who is gay. Obviously, Life Exchange did not affect Ektoras’ sexuality, but it did encourage him to do something outside his normal experience. Crucially, this change in behaviour was not because Ektoras stole Guilio’s identity, but because for a time he was bereft of his own.

Participants in Life Exchange knew nothing about their ‘new life’ until the moment they inhabited it; and for each piece of someone else’s persona they acquired they lost the corresponding accoutrement of their own—their own mobile phone, their own best friend, their own routine. The process must have seemed more like a loss than an acquisition. In this light, the man who flirted with a woman on that November morning was not Guilio d’Agostino (who knows if he flirts with women on the subway?) or even a performance of ‘Guilio d’Agostino’ (having never met him, how could Ektoras know how to perform?). Instead, it was an anti-performance of Ektoras Binikos—a man whose codes and imperatives of behaviour had suddenly been stripped away.

In a city that was playing host, at the same time, to the dead-eyed ‘re-enactments’ of Alan Kaprow’s Happenings [RT 83, p17] , this seemed like a breath of fresh air. Kaprow wrote scores to encourage people to meditate on the experience of living and to blur the definitions of art and life. But, a year after Kaprow’s death, these re-enactments, watched in a packed warehouse in Long Island, were like the hammy cousins of an art historical moment that was never meant to be played to an audience. In contrast, Life Exchange seemed to promise a very real experience—the “sensory becoming” that Deleuze and Guattari describe as the true effect of a work of art.

But while Binikos found the experience of Life Exchange liberating, the project encouraged self-reflection in a very controlled way. The precedent for Wooloo Productions’ 2007 Life Exchange is Nancy Weber’s Life Swap (1974, written up in a book published by Dial Press in the same year), in which Weber changed lives with another woman. Her swap was precipitated by months of discussion, note-taking and written instructions between the women, but it ended badly with each accusing the other of dishonesty and misrepresentation. Life Exchange, however, removed the possibility of any such accusations, because it took responsibility for the project away from the people taking part.

It was Wooloo Productions (rather than any of the people whose lives were exchanged) who provided legal documents and disclaimers; Wooloo Productions who carried out interviews and made matches; and Wooloo Productions who conducted a Life Exchange Ritual at the beginning of each swap. This meant that ‘exchangers’ were free to concentrate on their personal experiences. And, unlike the earlier project, they could never accuse each other of sabotage, because they didn’t own the processes that governed their behaviour. These processes were owned and issued, instead, by Wooloo Productions.

In other words, Wooloo Productions institutionalised Weber’s model. If Weber’s Life Swap was carried out like two women bartering in a market, then Wooloo’s exchange was more like people ticking ‘yes’ to the terms and conditions on a website. This overt mediation concentrated the experience on each participating individual, but it also rendered them strangely passive in the process. Even when exchanges ended badly—as did one between Jane Harris and ‘Joanna’, cut short after just a few hours—the participants did not blame each other but the institution that had led them there. “Just be forewarned”, says Harris about Wooloo Productions, “they don’t seem to know what they’re doing” (www.artnet.com).

It is this relationship of trust between individual and institution that lies at the centre of Life Exchange. Harris’ disappointment with the project reveals her desire to trust the institution—if ‘they’ don’t know what they’re doing, then who does?

In fact, during Life Exchange Wooloo Productions acted just like the big cultural institutions that govern our lives—what Althusser calls institutional state apparatuses. This similarity even extends to the “performance of distrust” Wooloo’s Rosengaard identified in US federal policy. Like the government’s performance, Life Exchange relied on an entity whose power is hinted at but never explained; participants were even blindfolded during the Life Exchange Ritual that began each swap to reinforce this sense of mysterious power. And, like government performance, Life Exchange demanded casual complicity from its public.

Was Jane Harris right to have doubts about Wooloo Productions? The institutional façade that the organisation erected was flimsy at best. The Life Exchange Ritual, for example, which featured candles and New Age music, was an empty, generic scene such as might appear, Rosengaard says, if you googled the world ‘ritual.’ And unlike US government policy, Life Exchange did not exploit conservatism. Instead, it centred on unpredictability, stripping individuals of their symbols and then leaving them to their own devices.

Life Exchange created a dream of freedom and a nightmare of loss at the same time. It gave its participants liberty from identity, agency and expectations. But in return it enacted a loss of identity, freedom and agency. Creating a mask that borrowed from the familiar processes of big cultural institutions, Wooloo Productions suggested that liberty can only come from the comforting arms of an institution. The question, then, is which institution do you choose? And which liberty?

Wooloo Productions, Life Exchange, New York, Oct 31-Nov 6, 2007

RealTime issue #84 April-May 2008 pg. 37

© Mary Paterson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Erth dinosaur, designers Steve Howarth, Bryony Anderson , Chris Covich, Phil Downing, Clalre Milledge, Ferdinand Mana

photo Prudence Upton

Erth dinosaur, designers Steve Howarth, Bryony Anderson , Chris Covich, Phil Downing, Clalre Milledge, Ferdinand Mana

TWO DINOSAURS ROAMED THE VAST FOYER FOR THE JOINT LAUNCH OF THE 2008 CARRIAGEWORKS AND PERFORMANCE SPACE PROGRAMS, A PALPABLY EXCITING MOMENT AFTER THE 2007 SETTLING IN FOR BOTH ORGANISATIONS. THE AMIABLE BEASTS ARE UTTERLY CONVINCING CREATIONS BY ERTH PHYSICAL & VISUAL THEATRE INC, ONE OF THE COMPANIES RESIDENT AT CARRIAGEWORKS.

Like big, slow puppies, the dinosaurs mingled with the large, if surprised crowd, making a brief appearance before leaving for Los Angeles—they were commissioned by the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum. A proud Scott Wright from Erth declares that the creatures are anatomically correct but is at pains to point out, because they’re often asked about it, that the company has nothing to do with the multi-million dollar Walking with Dinosaurs show. Wright is emphatic, these are human-driven body puppets; look, no animatronics!