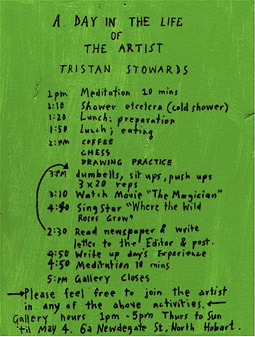

Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

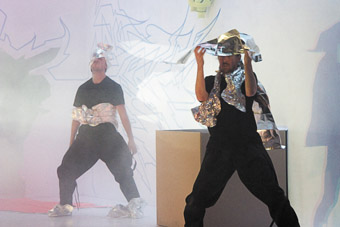

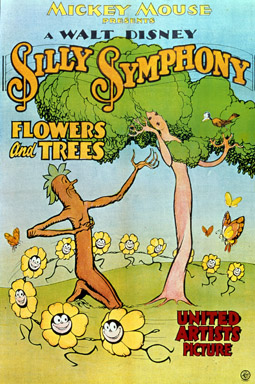

Shona Erskine, Will Time Tell? by Sue Healey

Sue Healey’s dance film opens with the question Will Time Tell? as its title superimposed on fuzzy horizontal streaks of a world flashing by. Fading into soft focussed closeup is a fair skinned woman (Shona Erskine) with brilliant red lips looking straight down the lens. Complicity with the camera is established.

She closes her eyes. Snippets of what might be memory abruptly interpose; of Erskine dancing with abandon in a scarlet coat on a massive outdoor wooden deck as if caught on coarse surveillance film by a camera on high, followed by a shot of ornamental carp languidly swimming, each scale etched in crisp focus. The dancer, still as a sign beside her, then stands feet planted on an urban Japanese rail platform as a train blurs in acceleration close behind. Its wind lifts her coat. The hurtling of the carriage flattens, becoming a restless field on the same plane as her stillness. Story-time is woven into being in the space between repeated multiple threads of visual and audio imagery. This film is a movement story of one woman’s travel experience. The stuff of time, its non-narrative materiality, is palpable in the juxtapositions of tempo mostly, but not exclusively, in edited human actions, choreographed and incidental.

The instantaneous momentum of the opening is arrested in a sharp focussed mid-shot. Erskine wearing a bright coloured 70s styled mini dress performs, with fingers like those of an orchestra conductor, a filigree of gestures carving sharp lines in the air. One stands out—her look back at us through ‘binoculars’ shaped by her hands in front of her eyes. This motif accrues weight as it pops up developed periodically by the five Japanese dancers Sue Healey worked with on her Asialink fellowship. It playfully evokes the continual observation of visitors to new places that travel prompts.

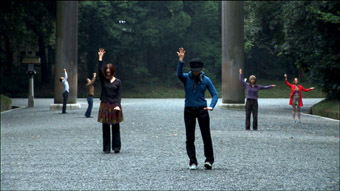

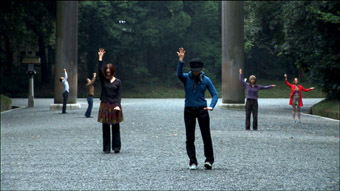

Is the narrative I read constructed by the film’s altering of human movement speeds and the rhythm of the edits, or are the grain, pace and colours, like the palette of a designer, meant for sensual appreciation? A Japanese dancer wearing a hoodie and the red-coated Erskine perform a smooth, delicate duet of immaculate unison in a Tokyo laneway. The choreography creates a shared time zone that bonds them, as pedestrians stride past unconcerned. This is time for reverie in a busy city street. This contrast between the pace and focus of the task-oriented pedestrians and meditative dancers is an entrancing compositional device in Will Time Tell? It returns later when the five Japanese dancers and Erskine fan symmetrically across a gravel avenue in front of a massive tori shrine gate, performing a gestural choreography with composure. Underpinned by a traditional sounding plucked instrumental and choral singing, tourists walk by, sometimes reversed in the edit.

Elsewhere, abrupt switches in music underscore stark edits. For example, koto-like strings cut to something like Japanese klezmah as our protagonist joins a man in a cafe by gently laying her head on white triangular-folded napkins set on a tabletop. As they sit up, the camera glides up and over from behind. It steadies on the relaxed dance of their hands, echoing each other’s shapes and grips in the warm dimness. There is a soupcon of voyeurism in the moment of touch. We see this male dancer next as one amongst five others, fishing in unison off a wooden boardwalk surrounding a pool in the middle of the city. The groups’ collective action is digitally interrupted, sped up and slowed. When images of the carp return, the camera lingers on the flowing rhythm of the fish.

Another jump cut takes us to a grainy Super 8 group portrait, the redcoated dancer included. They smile to camera as their eyelids close with imperceptible slowness. Is this a holiday movie grab from a Nihon vacation manipulated in the woman’s memory to embody a collective public meditation? Her intimate and gentle connections with people are tinged with the distance that travel compels.

Will Time Tell? vividly embodies the difference between time ‘for’ and time ‘to act.’ Periods for contemplation jostle with times to meet and be with others.

The film concludes with two contrasting vignettes. Reminiscent of a 19th century paper-cut miniature, Erskine’s wind blown silhouette dances on the crest of a paved hill against the smokey pastels of clouds just after sunset. In one long shot and in one dance she draws together fragments of movements glimpsed earlier. An aeroplane, rendered tiny in this wide shot, traverses the sky. The oompah of an organ grinder ushers in the end—a man places Erskine’s dress, red coat and shoes on a tailor’s mannequin for sale on a Tokyo street.

–

Will Time Tell?, a film by Sue Healey in collaboration with performers Shona Erskine, Ryuichi Fujimura, Makiko Izu, Mina Kawai, Yuka Kobayashi, Norikazu Maeda, director of photography Mark Pugh, composer Ben Walsh, editor Peter Fletcher; 2006

Will Time Tell?, Sue Healey

In her dance film, Will Time Tell?, Sue Healey follows a woman’s journey as she explores an alien city in which she is an obvious misfit. Time is manipulated and transformed around this lone figure, through jump cuts, slow motion and reversals, as she discovers new faces and places in a world that is unfamiliar. She wears a bright, blood-red coat: the deep, velvety hue is reflected on her lips. Peering into the lens, her hands delicately placed around her eyes, inquisitively looking through these hand-made binoculars, she views a foreign landscape.

in this 12 minute experimental film Healey investigates notions of time—how time can change our perception of place and how place can alter our sense of time. Time is discombobulated and morphed within a constant flux of images. The film opens with colourful sweeps of light, moving past at hyper-speed. Horizontal streaks of light flicker over the film’s focal subject, dancer Shona Erskine, her pale face lingering before the film cuts to an image of a speeding train—its details then becoming lost, blurring in and out of the frame.

The train, both friend and foe to the weary traveller, is an image repeated throughout the film. In one episode, I brace myself as I am taken on a joy-ride, the camera in the front of the train confronting its viewers with a fast forward wide shot. Like IMAX or virtual reality cinema, the screen seems to engulf even the peripherals of my vision and pull me into its world. I am out of my comfort zone: a music box plays as the audience is sped through the city in a flurry. Relief, the focus changes, back to observing. The red-sheathed figure, distinct in an environment of colourful fragments, intersects with others on a trajectory through time and space. Erskine forms brief relationships, which are all too quickly broken. Prolonged connections are rare for the lone explorer.

Though isolated, the woman shares a brief intimacy. In a tiny, seemingly claustrophobic restaurant, a man sits by her leaning on a small, rectangular table pressed against a window. They are soaring, sitting on the edge—observing, resting and folding napkins in nervous excitement. From a high-angle, over-the-shoulder shot we witness this awkward yet cosy interchange. The camera angle cuts to a view from directly behind, Erskine turning to us with a coy cheekiness as hands intertwine in an elegant dance with this stranger. They fold, overlap and tenderly touch, for a moment withdrawn from a frenzied, tumultuous world.

In another atypical moment of tranquility, in a little paradise in the hub of the city where the noise of the metropolis is stifled, carp bubble and splash in a man-made pond. The camera follows Erskine and others in a slow motion pan as they sweep their fishing rods across the water, in sync with perfect parallel spaces between. The sound slows, changing from an effervescent vaudeville-like tone to a light, calming one. The shift in dynamic makes Erskine and audience drowsy. We empathise with her—restless, jet-lagged and impatient—as she builds a makeshift bed out of three milk crates and fidgets to make herself comfortable.

Erskine awakes to navigate her way once more through this obscure, elaborate urban maze. She dances among others, though this time she is not the central focus. She is situated right of frame in a wide shot of a serene park in vivid contrast to the mechanics of the city. The dancers, in ordinary street clothes, move through a series of simple gestures, which when performed in unison create a dramatic choreographic structure. Erskine’s sweet, subtle gestures juxtaposed with her expansive, wild movements, take her body on an adventure that leads her onto a hill top at sunset. Her silhouetted figure, positioned centre-frame in a wide angle, un-edited shot, dances her last dance, a silent goodbye.

The shot changes: the dancer’s clothes remain but she has vanished. A shop mannequin is dressed in what once was Erskine’s, her experiences and stories now seemingly lost. Sue Healey’s Will Time Tell? has followed a woman and seen her sucked into a cultural vortex where she finds herself immersed in yet simultaneously cut off from a bizarre utopia.

–

Will Time Tell?, a film by Sue Healey in collaboration with performers Shona Erskine, Ryuichi Fujimura, Makiko Izu, Mina Kawai, Yuka Kobayashi, Norikazu Maeda, director of photography Mark Pugh, composer Ben Walsh, editor Peter Fletcher; 2006

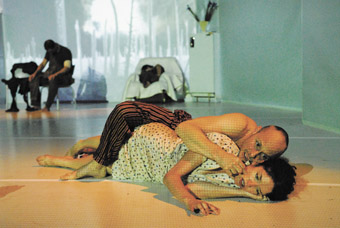

Nalina Wait

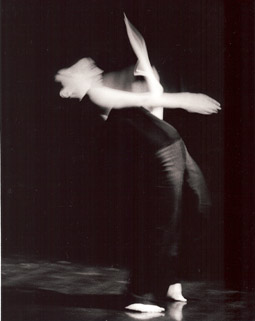

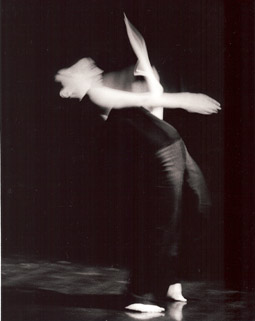

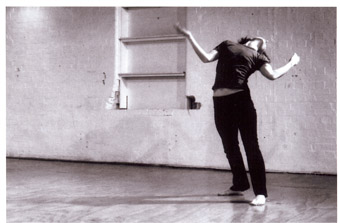

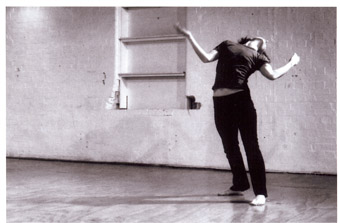

photo Andrew Whoolley

Nalina Wait

Nalina Wait is positioned in a set of perfect right angles, every hinge. Elegantly clad in soft, feminine green, her dress is modest yet exposing. Her limbs are milky soft, barely illuminated beneath a blanket of darkness. A lamp to her left leans over her. Its shade is inquisitively tilted, on the brink of toppling. The dancer’s fingers move to the lamp—it comes to life. An oscillating sound score emanates from the dark, croaking and vibrating like a mechanical insect.

The dancer’s body begins a gradual metamorphosis. The light floods, transforming Wait’s skin from a shade of pearl to warm amber. She moves through a chain reaction of twists, coils and circles which begins at her crown and end just beyond her toes. In a blend of tension and subtle calm the dancer’s tortured body is ironed into the floor. For an instant she seems to slip into an unconscious state before peeling herself from the surface. Has a slumber engulfed this helpless body or is Wait the subject of her very own lucid dream?

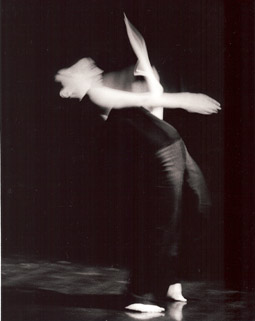

Suddenly on her feet, Wait moves rapidly downstage, her gaze skimming my head. Her body freezes with a numbing stare. Sporadic outbursts of flicks and flinches escape her as the ceiling lights clunk, grind and flicker on. Wait constantly arrives at a neutral stance, yet simultaneously fails to ever reach a climax in her moments of physical eruption. She is pulled through space by an external force; her limbs jolt and ripple as if wrenched from her torso in intermittent bursts. Possessed by her own nightmare, she is stolen.

In a post-performance discussion Nalina Wait says that she was influenced by the notion of “arriving and never arriving.” This is reflected through her choice of motif and in the dynamic of the work. Her body constantly struggles between stillness and spasmodic physicalisations. Much like Wait’s improvisations I’ve seen previously, the sense of presence and the movement quality of this performance are entrancing. Her dynamic shifts of weight create a mood of edginess and surprise. Much of this movement quality reflects the industrial, raw and eclectic noise of the guitar-based sound score—something new for Wait, who usually dances in silence.

Moving though a dance between her physical self, an invisible being and the floor, Wait slices the air with energetic tosses and breaks it with radical stops. What is being portrayed? Wait says that “embracing more of the psychological rather than anatomical elements” was of particular interest to her. She demonstrates this through her focus and a commitment that allows for momentum behind the movement. The choreographic detail appears to emerge more from sensation than aesthetic concerns.

Against the minimal setting of an empty room and a lamp, Wait’s movements are larger than life. Her deep lunges and abrupt foot work interweave in spirals of motion. It’s as if she’s dancing a duet with the lone lamp, detached but communicating inaudibly with it. She holds a secret she will never reveal to us. This shy object baffles me. Is it simply a lamp or is it a transportation device to take the dancer from one realm of existence into the next?

Wait’s breathing overrides the fading music, but her body resists, dancing on in silence. She gasps for air but eventually surrenders, returning to sit by the lamp. She stares, ghostly.

Nalina Wait

photo Andrew Whoolley

Nalina Wait

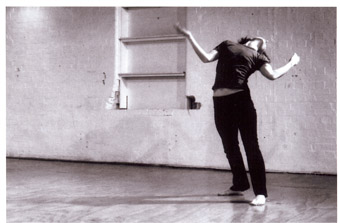

In a large, half-lit space, Nalina Wait sits by a standard lamp with a white, pleated shade. Her torso is straight, almost rigid, leaning backwards, slightly. Her left hand searches for the light switch. The lamp exudes a warm, golden glow, the shade tilted at the same angle as the dancer’s torso. Slowly, she turns her head upwards, allowing it to be bathed in light. She continues the circular motion initiated with the head, letting it travel through her body in a downward spiral towards her feet. These seem to have a life of their own, gingerly stepping away from the rest of Wait’s body, which soon follows, languidly moving across the floor into standing. Against a subtle electronic soundtrack, Wait is now in the dark, backlit by the lamp. She has utmost control over her body. And yet there seems to be a mysterious force at play that is larger than herself.

Suddenly, Wait forcefully strides forwards, stopping close by her audience as if to confront them. At the same time, a battery of overhead arc lights noisily clang to life and a loud guitar-driven soundtrack invades the space. The shift in intensity is enormous. The space is now completely transformed, both visually and sonically. Wait also appears changed. She looks straight ahead, into the distance. Her body jerks into action. Her legs are still planted solidly on the ground but her arms, head and torso are flung violently in different directions, exploding away from the body’s centre. The bout only lasts a few seconds and stops as abruptly as it started. The dancer returns to staring into the distance. Her expression is stoic, defiant even. It’s as if she is willing her body to be still, but to no avail: it erupts into another burst of out-of-control, short, sharp movement. More outbursts follow, never lasting much longer than the first and always succeeded by a moment of stillness. These function as both moments of respite and preparation for the next body explosion.

From time to time the soundtrack cuts out, only to resume its sonic assault soon after. The pattern of alternating movement bursts and intermittent stillnesses continues, relentlessly. Over time, the movement explosions seem to lose some of their sharpness, Wait’s body softens slightly. Her legs are not rooted in the ground as solidly as before, the knees are sagging, allowing for deep lunges and, at one stage, a roll on the floor. Is this exhaustion taking its toll or has the dancer succumbed to the violent movement attacks, resisting them less? Gradually, she moves backwards, eventually reaching the lamp and sitting next to it—exactly the position in which she began. She turns off the lamp; immediately the arc lights go out. Darkness again.

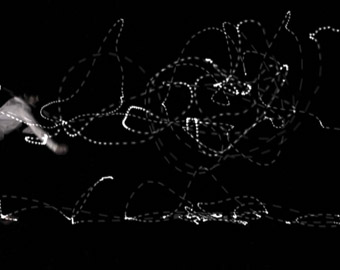

Martin del Amo, Anamorphic Archive, video still

Sam James

Martin del Amo, Anamorphic Archive, video still

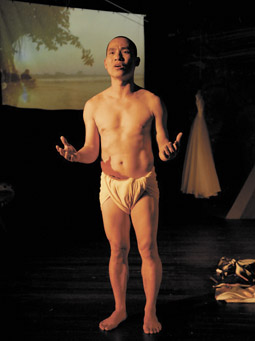

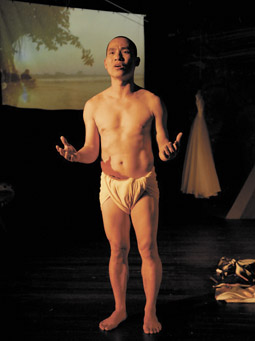

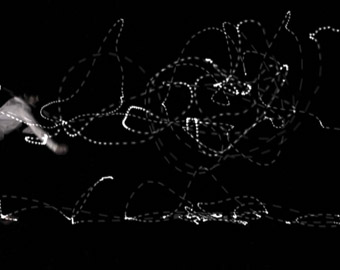

Dancer Martin Del Amo steps partially into frame. His right palm draws out his arm to full length, pulling his body into the black space. He is a small figure inhabiting the background, dressed in white trousers, long sleeved shirt and braces. He is a white figure moving left from the edge of the frame towards the centre, arms at length away from his body. He repeats a movement of arm to the sides: right, left, left then right, palms facing the camera. His legs move on a lateral plane: apart then together, in equidistance. It is an act of precise positioning. Function with form: a body knowing where it is going, where it has been. And yet, on this screen, a dancer seemingly displaced.

Anamorphic comprises eleven short dance films produced by dance filmmaker and video artist Samuel James. Martin Del Amo’s work features amongst the work of other Sydney performers. James the documenter of these originally live works, has disturbingly treated and distilled the essence of these performers dispossessed of their performance locale. With Del Amo there are several drafts of a man stepping into and dissolving on screen, a man in all his measure. The doubling of his background image occurs early in the film, a second figure emerging out of step with its identical counterpart. A second del Amo is foregrounded, moving on the same plane. The facial expression suggests a being entrapped by a system of straightened arms spoking out from the torso, legs opening and head turning rapidly, relentlessly. Del Amo appears to seek depth in these separate tracks of flattened perspective and movement. We glimpse in his face a desire for respite, for change. A new arm movement traces a path into his body interrupting the sideways back and forth trajectory. The image deepens in dimension. A split screen halves the foregrounded dancer. The vertical line as axis placed over his midline invokes a third less defined del Amo who issues forth from the internal spaces of the front man. The trebled image induces an image of a tireless trio.

Martin del Amo, Anamorphic Archive, video still

Sam James

Martin del Amo, Anamorphic Archive, video still

Despite the repetition of movement, the pulses of these reproductions are neither regulated, nor stable. Del Amo’s head shakes intermittently as a result of James’ digital manipulation. It is a mark of subtle transgression. There is an overall sense that James’ post production assists Del Amo in his emancipatory action against the weight, direction and intensity of the situation. All these extra del Amos are supplied by James as versions varying in resolution, perspective, scale and colour. They arrive and leave the space with different intentions. Which one will be left to bear the consequences of this invisible assault? Under Attack, the original live work by Del Amo provides a fourth mostly naked del Amo: his sweating kernel emphasising the laboured process. The black and white image gives depth to the flattened perspective. He teeters on self-defined edges, his swinging torso unconstrained, no longer bound to any vertical axis. The other del Amos take their exits one by one. There is a sense of relief in this presence, like an authentic gut reaction to a problem which lies undefined. The dancer’s movement takes its shape from the rib cage which hovers over a well anchored body. He stands still with the visual hum of breath and looks out at an angle. There is resignation and a glint of defiance. He walks out of frame.

Sound Artist Gail Priest furthers the accumulation of this unfolding of a man under stress, a man aiming to get it right, with a sound suggesting repetitious, mundane purpose. A constant ache echoes within a machine’s industrial joints. As the inner del Amo extrudes, a violent tapping on a violin, highly strung, grows in fractals like a rash ad nauseam, invoking psychological tension. Both Priest and James in their applications of repetition show the devolution of a man within the promise of an unshakeable structure: he knows where he is going, what has been, but the present is unsettling.

Del Amo is like a little Russian babushka doll. At first the film’s form suggests ‘a similar object within a similar object’, but Sam James’ masterful manipulation of bodies in the dimensions of a filmic space makes complex the notion of peeling away outer layers. The inner emerges resolute through imbalances of scale, black and white costume in colour against black and white film, a split screen and superimposition. While the original live performance may remain a mystery to the film’s viewer, del Amo’s experience is distilled by his documenter, reconstituted and placed in new configurations: scattered little babushkas.

Shona Erskine, Will Time Tell? by Sue Healey

A woman in a red coat stands still on a street corner as traffic passes in front of her. We see her again as trains pass behind her; neon lights flash. She dances a jig along a travelator, moving the wrong way. She is seen in the grain of slow motion super8 film, alone with shoes off, leaping, turning and running. Sue Healey’s dance film, Will Time Tell? offers a view of passing time through the speeded up and slowed down journey of this woman in red against the background of Tokyo. Yet, in the director-choreographer’s approach to the theme of time, it is movement, in all its many forms, that is most strongly focused on.

The film opens with shots of the woman, dancer Shona Erskine, seated on a train, the flicker of colours from a window reflection trailing across her face. These shots are interspersed with Erskine performing a precise gestural sequence. With her hands forming alternately into binocular and camera shapes and neatly rearranging them across her face, Erskine shapes her vision or mimes the gestures of tourists, whose view is so often framed photographically.

Another scene has Erskine looking directly at the camera, laughing and approaching it with familiarity. These opening scenes are filmed on Super 8, evocative of the amateur footage of holidays past. This look and Erskine’s short shift dress, all paisley-like swirls, could place her in the 60s. She is positioned against the Japanese background with her pale skin and bright red lips as an outsider, but the choice of costume seems to locate her as slightly out of time too.

The high definition scenes, however, locate the film firmly in the present, and also introduce the play with speeds within the frame. We see Erskine, still but for the jerking movement of her arms, at a train station, while trains and people appear and disappear in fast motion around her. She could be conducting traffic or simply being moved by all this bustling energy. Later, there is a slowed down tai chi like movement sequence performed by a group of Japanese dancers, with pedestrians passing by in real time. In most of the scenes, Erskine is seen slow against the backdrop of fast or real time motion of the outside world. Again, she is the traveller/outsider.

In a post screening discussion of Will Time Tell, Sue Healey noted that although the film began as an experiment in shooting in external light out of the studio, it is, like much of her recent work, preoccupied with notions of time. For a dance film (a hybrid of forms in which playing with time seems unavoidable) this concept seems a complex undertaking. However, Healey takes a compositional approach, each scene having a specific reference to time through speed, rhythm and directionality, as well as references to clichés such as ‘time stood still’ or ‘marking time.’ There is the literal journey of the traveller, of trains coming and going, but also a journey in the cinematic narrative sense, with Erskine as central character in a foreign city.

What emerges is a film that is not unlike a travelogue, dealing in the currency of memory or nostalgia that we are used to seeing on the screen. In particular, I am reminded of those tourism advertisements for Melbourne where a lone woman reminisces on her visit, as we see shots of her wandering streets, meeting with friends, eating, laughing and drinking. But Will Time Tell is much more than this. There is the framing quality of Ben Walsh’s Japanese sampling soundtrack, the sheer radiance of Erskine’s cinema screen presence, and most of all Healey’s interest in choreography.

There is something about travelling in a foreign country and not understanding the language which makes movement and gesture apparent. Sue Healey’s film captures this sense of travel, through the large-scale organized movement of trains and crowds to the particular details of friends meeting. In one scene Erskine is pinned against a fence, awkwardly close to a group who perform an intricate choreography composed of the gestures of shaking hands, greeting and laughing. Erskine’s physically cumbersome presence highlights the sense of outsider through the particularity of movement in what would otherwise be a familiar scene.

The aspect I most enjoy in Will Time Tell? is seeing the fine precision of movement in Healey’s dance vocabulary set against the wider, incidental movements of Tokyo, the city and its inhabitants. This recontextualising of the dance within this cinematic background allows a broader, more nuanced reading of Healey’s choreographic terrain.

–

Will Time Tell?, a film by Sue Healey in collaboration with performers Shona Erskine, Ryuichi Fujimura, Makiko Izu, Mina Kawai, Yuka Kobayashi, Norikazu Maeda, director of photography Mark Pugh, composer Ben Walsh, editor Peter Fletcher; 2006

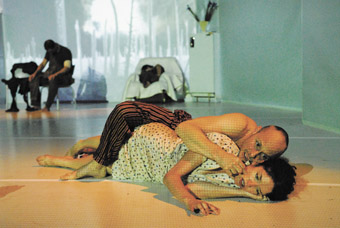

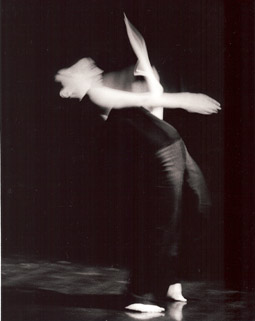

Nalina Wait

photo Heidrun Löhr

Nalina Wait

Nalina Wait’s audible breath in the throes of a final paroxysm is powerful. As the discordant, nervy loudness of a frenetic guitar is silenced by the presence of this laboured breath, a palpable intimacy is felt between the dancer, her audience and the finding of a dance. Wait hardly traverses the massive elongated space of the Drill Hall, but her breath thwarts this notion of visible distance, reminding us of the physical effort in negotiating the topography of an inner landscape. Through means deliberate and considered, Wait’s short work attempts to disclose hidden elements of her self, to herself, in the unpredictability of performance.

In the beginning she sits perpendicular to the floor, delicately composed with legs stretched outwards and torso slightly tilting. Her angle complements that of a standing lamp, its concertina shade slanting on the same vector. The soft rotation of her head leads the torso to hinge from the hips, lightly anchored by her lower body. Wait’s orientation shifts, deepening this hypnotically paced movement. Her feather like extension is paradoxically grounded by the astute instinctiveness of a body that knows its structure.

Night sounds are evoked by a metronomic ticking. The concentrated circle of light from the lamp that balances the contrast between darkness and Wait’s creamy skin is extinguished as the overhead house lights turn on. Their reeling flicker eventually illuminates the room. The recording of an electric guitar played atonally is intermittently switched on and off instigating fitful dance movement and sudden twitches from Wait, punctuating her stillness as she stands in close proximity to her audience.

Moments where Wait is ‘overcome’, by an internal emotional force or an almost Tourette-like disorder, accumulatively intensify. Her first phrase, however, emerges as though her body is undergoing an external attack: the left elbow bends, drawn out of the body; the head strains away, tipping her entirely off centre though still rooted by legs moving in varying configurations of open second. She re-gathers by moving her feet into parallel, her tilted torso negotiating the horizontal, swung out by arms, brought in by a contraction at the centre with a single knee rising into sculpted flexion. Occasional peace in the delirium is also arrived at through bobbing down: upper body meeting lower body, or weaving arms toward her midline to escape peripheral forces.

Towards the end of the guitar track Wait begins to retreat upstage, the self-gathering lessens, the body unravels, yet still teetering on the threshold. She has arrived, for the moment. Her coda is the breath score, a final image: her original position next to the lamp. As the overhead lights and lamp are switched off we are left to feel that there was never to be any resolution, just respite from the sporadic concertina folding and unfolding of internal states. Her ending merely suspends the inquiry.

Rose Dennis, Anamorphic Archive, video still

Sam James

Rose Dennis, Anamorphic Archive, video still

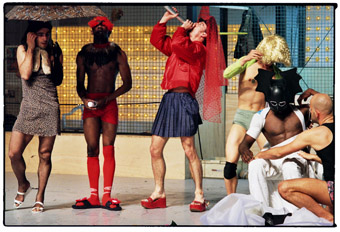

In his remarkable new dance film project, Anamorphic Archive, dance filmmaker and video artist Sam James digitally manipulates documentary footage of live dance performances to create filmic reinterpretations of the original works. One of the most striking examples in this impressive collection, comprising eleven short films, is James’ treatment of footage documenting Rosie Dennis’ 2005 work Access All Areas.

Dennis, clad in the uniform of an office worker—white blouse, blue vest, blue skirt, brown shoes—strides through a large space framed on one side by a black brick wall. The footage, including the audio track, is slowed down, Dennis’ footsteps on the dark floorboards echoing ominously as she walks forwards as well as back. There is something eerie about this opening sequence. Slowing down the footage gives the performer a menacing presence. Is this is the calm before the storm?

Rose Dennis, Anamorphic Archive, video still

Sam James

Rose Dennis, Anamorphic Archive, video still

It sure is! The next section could not be more different as far as pace is concerned. It accelerates Dennis to top speed, both physically and vocally. It’s as if a previously dormant volcano has unexpectedly erupted. She frantically shakes her head, the right arm stretched out in front of her, also shaking. Sharp intakes of breath give her voice a percussive quality. She continuously repeats the phrase “I don’t want to touch what the majority touches.” The speed at which she moves and speaks is dizzying. All of a sudden, her image multiplies. There are now three versions of her, each one layered on top of the other, several frames out of sync. By splitting the performer’s image into three and having them each reverberate against the other, James powerfully emphasizes the manic, obsessive-compulsive quality of a Rosie Dennis performance.

Usually, the main objective of the archival documenting of live performance is to preserve the works, making them accessible to viewers long after the actual performance. With Anamorphic Archive, James subtly subverts this notion. His work begins where other archivists stop. He uses the documentary footage as source material for his own artistic endeavours. Taking the liberty to change the framing and timing of the documented live performance, James reinvents the original, creating a new, autonomous work in the process.

It is James’ great achievement that, even though he manipulates the documentary footage entirely according to his own artistic vision, he manages to capture the essence of the original works. This brings up the question: can Anamorphic Archive only be appreciated by those who have seen the live performances on which the films are based? The answer is inconclusive. The results of James’ digital treatment are so accomplished and sophisticated that the films certainly can be enjoyed as independent works in their own right. On the other hand, there is definitively an added joy in being able to see to what extent and effect James has altered the original performance.

The live version of Rosie Dennis’ Access All Areas, for example, is a model of conceptual rigour, choreographic economy and performance skill. At first glance, it is difficult to imagine how such a finely tuned work can possibly gain through digital manipulation. And yet, by creating images that exemplify the inner turmoil of Dennis’ troubled office worker, James succeeds in adding a dimension that cannot be achieved in live performance. One section in the film is particularly memorable in this respect: five images of Dennis are positioned in different places on the screen, all in sync. Dennis moves at the same breakneck speed as in the earlier section described above, but the sound has now been removed. With her gunfire vocals silenced, her franticness appears strangely softened. The images are then rotated at different angles, appearing to float freely against the black backdrop of the screen. It’s as if Dennis has lost her footing, drifting in space, alone, lost to herself and her viewers. Her head is still shaking, circled by one of her hands, desperately searching. Suddenly, the images of Dennis multiply again. Serialized in eight rows of 12 small images each, now there are almost a hundred incarnations of Dennis.

The title of Sam James’ dance film project refers to the phenomenon of anamorphosis, describing both a distorted image that appears normal when viewed from a particular point or with a special device and the process by which such images are produced. Creating new films by digitally distorting their documentary source material, James offers audiences a new perspective from which to view the original works. As is the case with his take on Rosie Dennis’ work, James does not abuse his role as the all powerful manipulator. He tries to stay true to the intentions of the dance makers. It is his interest to illuminate rather than to obscure. The sensitivity with which James approaches the manipulation process prevents his reinterpretations from competing with the originals. The films are distorted reflections of the live works, neither one more real than the other.

Nalina Wait

photo Heidrun Löhr

Nalina Wait

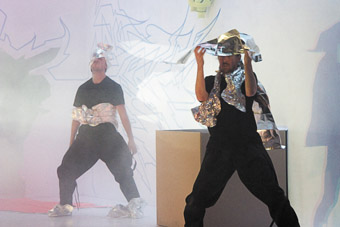

A body, all twitches and flung out limbs, creates crackling shapes against a black curtain; a body jolted into action by some unseen force, the motion constant, driven. Another body, still with eyes fixed on the wall behind us, is drained of potential movement, rooted to the floor. In the central section of this five-minute performance, Nalina Wait jump-cuts between these two bodies. There is no sense of arriving, but of having already arrived at one state or another. There are no transitions, no preparations, none of the in-between steps common to formal dance. It’s all or nothing. I see two Waits, overlayed: the still and the moving.

Wait’s performance begins with her sitting on the floor, her legs outstretched and torso angled back, next to a standard lamp. She flicks it on, and begins a slow rotation of her head. The sound score evokes insects in summer heat. Wait slowly winds herself to face away from the lamp, rolls to the ground, keeping her limbs long and straight, and pulls herself back to sitting, lead by her fingertips. She sustains this taut straightness, a drag of limbs against the ground, to standing.

The soundscape cuts out and a rough, loud guitar squall takes over. The overhead arc lights individually grunt their presence, cueing Wait to break her movement. She walks directly to the audience, and stands in confronting proximity. Her gaze is out, directly over our heads. A shockwave of movement erupts, head back, elbows flung out, fingertips charged, then halts into stillness. Wait splices between these two states, on and off. The movement builds, taking over; the stillnesses contract. Wait is in and out of sync with the sound. The movement takes her backwards towards the lamp. She stops and sits. The lamp and lights flick off.

I declare my interest. I have worked with Nalina Wait over intensive periods in the last year on her new work, Dual, and have watched her dance, responded to her dance and tried her dance on. I feel familiar with the rhythm, impetus and arc of her dancing body. Yet, on first watching in this turned round position of reviewer, I feel stumped. I’m not watching the dancing body. I’m looking for grand narratives, meaning. I’m mixing up personal information with what is actually happening. The lamp evokes a domestic setting. Who is her intensely fixed stare focussed on? At whom is the twitch, jerk, coil and recoil of her movement directed?

Wait repeats her performance. I am glad of a second viewing. This time I watch the body, its tone. There is an elasticity in all her movement. In the opening passage, the skin is stretched taut, resisting an impetus or fire. I am taken by the small release of this tautness as the music changes and Wait walks forward. The centre section is also fired by this elasticity. Her limbs are flung out from her body but are always retracted, arcing back in, seeming to provide an internal engine for more movement. There is tension, not only between stillness and action, but also in the movement itself. Apart from the small moment of change in the music, it is never quite released.

This tension suggests the kind of psychological state in which Wait, post-show, declares a new interest. Her dancing body seems to evoke possibilities of emotion, while never settling on any stable reading. But the overt duality of frenetic movement and dulled stillness suggests more subtle resonances of interior/exterior and conscious/subconscious. What I find most compelling about Nalina Wait’s performance is her ability to jump directly between these states.

Will Time Tell?, by Sue Healey

Will Time Tell? is a delicately crafted, episodic dance film directed by choreographer Sue Healey. It is the tale of a traveller who remains the tourist, never fully sinking into the landscape into which she journeys. A hand held Super8 camera takes grainy holiday shots, cutting across the clarity of digital technology used elsewhere, reminding me I am watching a film, keeping me distanced from the seductions of narrative. Clear manipulations of time, so do-able in mediated art, create a contiguous but choppy story that meanders, developing from the speeds at which people move. In this world meaning is time. Disturbingly, a mist of colonialism lingers around the woman, archetypal in her blonde whiteness, her vivid costuming, her anonymity and her alienation as she swishes through urban Japan. Remaining apart, she seems voyeur to her own action. Will there be a re-assuring embrace? Is she an apparition?

Sue Healey casts dancer Shona Erskine as the stranger in Tokyo. Her startling red costume is unsettling in its domination of the tonal palette, its searing colour mitigating against subtlety and complexity. It screams at me in every scene. But this costuming choice does transform Erskine into a superimposition, keeping her slightly unreal; separated from people, place and shared time. A train rushes behind her, blurred into abstraction: she is steadfast and still against this speed and the world behind her is made pallid against her loud and stolid tones. She is alone.

Disjunction, as the propelling narrative tension, is expressed as a manifestation of time in this wordless 12 minute film. The red coated woman is warped into slow time somewhere beyond stillness while Japanese locals are propelled into hyper speed, rushing in streams around and past her, throwing her into a solitary bubble, but also swallowing her in hubbub. Paradoxically, she at once stands out and is negated.

On a travelator Erskine dances quick and perky amidst the marked restraint and orderliness of dark suited workers, going about the business of a regular day in this regulated city. She is ahead of the game as she glides gaily across this landscape of plodding time. Now it is she who is oblivious, resisting the tempos of her environment: not just a victim to disjunction, but an active participant.

Healey manipulates filmic temporality to reiterate the essential constructed-ness of lived time. Perambulatory time, measured and object oriented, creates people who pass by, not seeing. Time spent in waiting becomes awkwardly lengthened and uncomfortable as the red coated woman stands on a corner that becomes a spatial and temporal intersection; she appears indecisive, almost fearful. Happy time is jumpy and so sadly brief. Time alone is maddeningly slow or restlessly yearning and time with friends dissolves into time alone again.

But there are moments when she enters this world. Short sequences of unison dancing that embody a Japanese delicacy and reveal the idiosyncratic detail of Healey’s choreographic skill. Erskine and a Japanese dancer come together in slow lateral sweeps of hands with gesturing fingers, making time stand still in a streetscape where movement is meant to get you somewhere. These simple and delicate gestures of dancers out of context are a lacuna in the fabric of regular time and space. Gentle unison binds these women as the traveller shares language with a local. But still the coat screams.

The dance of the hands is the point of most complete immersion. At last the coat is removed in a suggestion of cosiness and ease. This is the ‘sex scene.’ In a busy café, hands meet, slightly shaky, and mingle flesh, digits dancing. A lingering high view reveals differing skin tones: between man and woman, Caucasian and Asian, between palm and back of hand. The muted light of the restaurant softens the slow touching. I see the hands as the lovers do, from above and they become mine, my body drawn into the film just as the traveller is drawn temporarily into the warmth of intimacy. It is peaceful in its congruence, a relief in its contentment, so pleasurable in its sexuality, voyeuristic and intrusive in its proximity.

But this conjunction disappears quickly, her lover soon becoming just one in the crowd. A shop front mannequin is being dressed in her coat, ready for sale. Has she gone? Was she ever there?

–

Will Time Tell?, a film by Sue Healey in collaboration with performers Shona Erskine, Ryuichi Fujimura, Makiko Izu, Mina Kawai, Yuka Kobayashi, Norikazu Maeda, director of photography Mark Pugh, composer Ben Walsh, editor Peter Fletcher; 2006

Nalina Wait

photo Heidrun Löhr

Nalina Wait

Sounds like the whirring of electro cicadas in the night become audible. The performance begins. On the floor, taut, tilting on her tail like the point of a compass sits a young woman beside a standard lamp. My head rolls in response.

Impulses hit dancer Nalina Wait without warning, minute and then all encompassing. Sudden stillness strikes this body. A subtle trio unfolds between the sounds—the snap of lamp switch or the staccato of thrash guitar soundtrack—unseen features of this room and this dancer’s body. Bit by bit we are made aware of the room as the brief dance progresses; lamp and location gather significance as time passes.

We are in a professional dance studio on a warm Saturday afternoon. The event is a boutique showing for an invited, appraising audience. Simultaneously the aura of night-time, of a domestic space thickens. We are all in both places at once.

Wait heads downstage and abruptly stops, facing us. In unanticipated crescendo, the ceiling-full of arc lights, whose presence had gone unnoticed, splutter to brightness. Their sonic glitches invade her body without warning, radiating through her joints. Nervous energy hurtles through spine, shoulders and hips, propelling her limbs. Stillness interjects, textured with tiny ripples through her neck, lifting her chin. These are an aftershock of frenetic but precise gestures of legs, arms, chest and head.

She waits in suspension, feet grounding her composure. Her stillnesses echo sudden silences in the thrash guitar track, but not in sync. Soft yielding alternates with bracing, strident action. The rasp of inhalation and visible pumping of her pulse become prominent in the silences. Her gaze returns gently to a place far beyond us, but her eyes don’t fix on anything. Her focus seems to emanate from her skin reaching around her instead of ahead. Eruptions from places within, like buttons pressed, trigger reverberations of short-term audio memory. The soundtrack ends. Wait’s limbs continue to ferociously carve space about her.

The intermittent battle settles. She is back seated beside the lamp. Not-quite calm returns with the darkness.

Nalina Wait, without a shred of didactic intent, has gently inducted the audience into the work’s vocabulary, sharing how her body was surprised, shocked in the ravelling and unravelling. There were hints of emotional reaction to matters close and far away alongside items of the everyday—home interiors and clothing. These could suggest a narrative. However, the relationship between a hovering backstory and Wait’s intense labile engagement with the materiality of the actual setting was ambiguous. In this gap, there was space for our bodies to be caught up in the visceral flow or to elicit memories and sensations of other rooms.

Nalina Wait

photo Andrew Whoolley

Nalina Wait

Nalina Wait sits firmly upright: a sharply and simply perpendicular body. This position calls on and displays the power of a working dancer’s abdominal musculature and structural alignment. This centralised strength will be her engine room, her ballast and her home throughout this furious work that dances the nightmare.

This untitled, five minute dance piece uses light as a harbinger of madness. A darkened and peaceful pre-set dissipates as a solitary light, a humorously tilted standard lamp, generates the electricity of movement. The dancer is sleepily complicit as she turns on the light and becomes the heroine in a David Lynch-ian descent.

Wait’s head tilts slowly to the side, revealing the neck in a luscious moment that will be too quickly lost. This tilt takes her away from symmetry and begins the journey from surety to distraction. Rotation takes her torso to the ground, but, unable to rest, her arm involuntarily reaches away and pulls her up, up, up to her feet. Like her pelvis, Wait’s feet are knowing and solid, bound to the earth in gravitational suction, lifted in the arch and ever-ready for movement in a buoyancy only efficient strength can provide. These glorious feet will hold my attention as they spread and contract on a floor the dancer trusts. Her feet know when to speak and when to stay silent.

A blast of light floods the room with manic brilliance and instant heat: in a moment peace and logic are lost. The dancer charges at the audience only to suddenly halt. Movement will now become a frenetically flinging and flailing motif repeatedly modified, allowed and controlled by Wait’s deep sense of centre. Punctuating the wild hurling of limbs are moments of soft but measured collapse to floor and standing stillnesses where Wait stares out to an imagined place over our heads. Her eyes glaze meditatively, the dreamer arrested by the need for respite, however slight.

But repose is smashed apart by quick turns on feet sucked together to provide a solid base for her tilted spins. Wait doesn’t rise up in the ballerina’s releve: she hovers across and around the landscape, simultaneously light and gravitational, madly efficient. Little jumps twitch her up and back and around. Lunges pulse back and forth. Arms are held up and out to dry, dislocated from a dropping torso or stretched back, disappearing from her own arc of vision, unnaturally investigating the dark terrain behind. Grounded legs support madly carving lines of action creating a field of forces, exhausting and compelling to watch.

Wait is a dancer who understands the gradations, possibilities and fleshy realities of intensity and how to play with them. The variant forces of frenzy and stillness pull her around the stage and stop her in her tracks. Herein lies the dramatic tension that Wait speaks of in a post-performance discussion as a vital choreographic stimulant and structure. There are the conflicts of “arriving and never arriving”, the confluence of “surprise” and repetition, the solidity of structure and the spice of improvisation, the push of agency and the pull of unleashed psychology.

She is both affecting and affected as she dances and is danced by the torrential guitar that tears through air and bodies. A score that began as a metronomic chirp has become the slamming chords of violent nightmare, a dream that would sit any sweat soaked sleeper bolt upright. This is music a dancer must stand up to, it is huge and demanding, with screeching irregularities, that, like the dancing, writhe and rest. And Nalina Wait does stand up: apparent in the heaving breath that is testament to her effort and a lingering trace of psychic turmoil.

At last there is return to the possibility of gentle sleep, to the symmetry of perpendicularity, to a more lasting stillness and to sweet darkness.

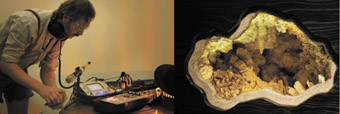

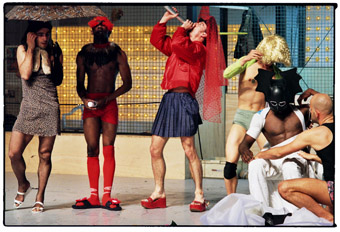

Vanessa Tomlinson, All Vinko: The Theatre of Music

photo Sharka Bossakova

Vanessa Tomlinson, All Vinko: The Theatre of Music

FOR AUSTRALIAN CONCERT GOERS VINKO GLOBOKAR (FRENCH-BORN SLOVENIAN, 1934) BELONGS TO A ‘LOST GENERATION’ OF EXPERIMENTAL COMPOSERS PRODUCING WORKS FOR THE CONCERT HALL FROM THE 1960S ONWARD. HIS WORK HAS HAD ALMOST NO EXPOSURE HERE OUTSIDE OF REFERENCES IN ACADEMIC TEXTS. CLOCKED OUT (INCLUDING VANESSA TOMLINSON WHO WORKED WITH GLOBOKAR IN VIENNA) GIVES US A CATCH-UP CONCERT DEVOTED TO FIVE OF GLOBOKAR’S WORKS, SPANNING 1969 TO 1997.

The concert starts with Discours VIII for wind quintet (1984), scales rising at different rates to create a complex overlay of notes that sync up every so often, turn into drones, then start rising again. The performers move about, leave one standing alone in the central spotlight, return, stand with their backs to the audience, exchange conversational snippets of sound and gesture. The sound is beautifully balanced. The effect of the movement is formal, measured, music as re-enacted dance.

Next is Corporel for Body Percussion (1985). Tomlinson sits alone on the stage, hands over her face, forcing sound out of her mouth and through her fingers. She rubs her face, taps her head, taps a clavicle, leans back and slaps her hands down on the floor. She moves her hands across her body from top to bottom, scratches her hair in a systematic exploration of the spatial geometry of the head. The effect is discomforting, as though Tomlinson is visiting an unfamiliar body and checking the surface for defects. The personal is suppressed, the performer reduced to a vehicle for the expression of rules and the ordering of symbols.

Kvadrat for four percussionists (1989) follows. The performers sit facing outwards on chairs arranged in a square. Each chair has its own set of commonplace objects nearby. Water drips from hands, paper gets scrunched and shaken, carrots clap together, ropes get whipped, feet move, micro gestures make no sound, and at a cue—maybe a music box or an alarm clock sounds—the performers change places. It’s like a party where everyone gets to adopt positions, say their piece, but never actually speak to each other—although there is a final all-in-together singing of the universal OM. There seems to be a claim for percussion as a way of finding the meaning of the world by sounding its objects, or perhaps the claim is that the sounding gesture magically brings meaning to the objects it strikes. Again there is the indication that the performance of music has some function over and above the making of sound.

Another solo piece for Tomlinson, Pensée ecartalée for percussion solo (1997). Voice sounds and the hum of whirlies, coughing, moving from one bit of equipment to another, getting annoyed and hitting things in frustration. Like early tape music, this work of Globokar’s is very serial, one sound after another, with little or no overlapping between. But the gaps between the sounds aren’t long enough for the sounds to become things-in-themselves, not short enough for them to gestalt together into a rhythmic progression. On the up-side it reminds me of John Cage’s Water Walk (http://blog.wfmu.org/freeform/2007/04/john_cage_on_a_.html). However, the humour and musicality of Cage’s performance is missing. Comes across as a bit aimless in the end. The composer again seems to be using the performer to enact a behavioural sequence rather than seeking to engage them with the possibilities of performance.

The final, and oldest, work—Discours II for trombone quintet (1969)—is the strongest. To begin, we watch the performers getting ready to begin—making sounds with the mutes, banging the trombone bell, shuffling about with the gear. This gradually works into lots of breathy sounds and the usual fabulous farty resonance of the trombone—Globokar has been a virtuoso trombonist and it shows in this piece. There’s humming, laughs and chuckles, lots of vocalisations made through the instrument to transform the voice and situate the performer within the sound making. A soloist plays on all the time and the others pop in and out trying to get some sort of conversation going. Sparse and silent becomes waiting and preparation. The performers begin to grumble, pick up their mutes and one by one walk off, leaving the last soloist gabbling away like a TV left on by mistake in another room.

Clocked Out, All Vinko: The Theatre of Music; Queensland Conservatorium of Music, April 4, http://www.clockedout.org

RealTime issue #85 June-July 2008 pg. 49

© Greg Hooper; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Synergy, Bree van Reyk, Michael Askill, Alison Pratt, Timothy Constable

IANNIS XENAKIS IS REPORTED TO HAVE SAID THAT “TO ESCAPE FROM THE TRIVIAL CYCLE OF RELATIONSHIPS IN MUSIC, THE MUSICIAN, THE ARTIST, MUST BE ABSOLUTELY INDEPENDENT, WHICH MEANS ABSOLUTELY ALONE.” ONE SENSE OF THIS WAS EVIDENT IN THE SHEER DRAMA OF TIMOTHY CONSTABLE’S PERFORMANCE OF THE COMPOSER’S PSAPPHA (1975), A SOLO WHICH, WHILE EXPRESSING NOTHING LITERAL, SUGGESTED MUCH.

CarriageWorks’ Bay 20 is a perfect venue for such percussive theatricality. It’s an acoustically and spatially ideal venue for contemporary instrumental music, offering clarity, limited reverberation and opportunities for maximum expressiveness, realised here in the clear geometry of instrument placement and Neil Simpson’s pools of limpid light and casting of giant performer shadows.

The first half of the concert comprised two mesmerising works by Steve Reich. Six Marimbas [1996] was given great aural depth of field by placing the marimbas in a wedge widening out to the audience in twos. The rear two appear to provide the underlying machinery for the work, while the forward four at different times drop in out of the soundscape, sometimes quietly as Reich’s phasing is magically realised, sometimes dramatically with a loud, precise bell-like entrance. Amazing sounds are generated as if the six marimbas are one instrument, their overtones suggestive first of a deep organ and later of distant carolling bells. Here is work that takes you up with its insistent, contagious complexity.

Drumming [1971] Part 1 for eight tuned bongos is, as Reich intended, never imitative of African music, although inspired by it. There are certainly moments that seem to incidentally evoke that sophisticated percussion tradition; built around a bell pattern, the phasing generating layers of merging sound, create a high collective shimmering rattling and, out of the blue, strange half melodies. Again the staging is potent: a line of bongos at right angle to the audience with three percussionists on each side, the whole in a narrow line of bright light in an othewise darkened space, heightening the sense of musical and physical concentration.

The second part of the concert featured three works from Xenakis: Psappha [1975] and Claviers (Keyboards) and Peaux (Skins), both from Pleiades (1978). After the determined pulsing of Reich, we enter a world of radical changes in tempi and mood, familar to us from romantic and especially modernist idioms, but with their own very special character in the works of Xenakis

In Psappha, Timothy Constable stands amidst his instruments: two large drums, one of them huge on his left, a glockenspiel centre, small metal or wood blocks to his right, and overhead a small set of chimes. With this musical machine Constable performs a wordless dramatic monologue replete with moments of reflection, of passion and suspended actions—hanging over the big drum before belting it mightily and swinging about to tap out its sharp opposite, or breaking into a supple glockenspiel melody, almost oriental in feel, quite counter to larger antagonisms. There’s a compulsiveness and violence about the recurrent strikings that some have suggested reflects the composers experiences of World War II where he fought with the Greek resistance. Psappha is nothing so literal but its existential drama is here amplified by Constable being aptly cast as two huge overlapping shadows on the stony CarriageWorks’ wall. The drama concludes without lingering, with the loud and lone ringing of the small chimes. An ambiguous ending.

If Psappha is drama, Claviers is dance. Conducted by Daryl Pratt it features three vibraphones and two marimbas combining to create a bell-like asynchrony against rippling marimbas, all the instruments high, liquid and sparkling, then dipping into a constantly repeated scaling up until reaching a plateaux again of bell resonances rich in harmonics. There’s a little vibe solo and a return to the collective scaling, all the peformers leaning deeply to their right and darting left in a cohesive dance. Theres a pause and then a fast bright, almost minimalist beat interpolated with gonging overtones leading to a final transcendent humming harmonic, all the players, finally still, holding sticks aloft. Magical.

For Peaux, six players and eight timpani, with smaller instruments tucked in between, are placed in a wide gentle arc and variously played with sticks, as well as hands and pedalling feet. There are moments of complexity and then sudden, propulsive unison riffs. A storm of pummelling is followed by a deep unanimous drum-rolling, broken from and then returned to until the whole is tapped down to silence. Again the work is wonderful to watch, with Constable and guest player Eugene Ughetti ‘dancing’ on the outer ends of the arc to the demands of the scoring. There’s a heightened sense of teamwork all round, the players keeping an eye on each other, signalling, conducting, dextrously moving as one.

This was an impressive concert in every respect, musically complex, dramatically powerful and spatially well conceived, the extended ensemble (guests Eugene Ughetti, Jeremy Barnett) playing with confidence and a sense of exhilaration. The new Synergy (Michael Askill, Timothy Constable, Bree van Reyk, Alison Pratt) looks set to enjoy a great future. Not least, this concert was for many a revelatory introduction to Xenakis as a composer for percussion.

There’ll me more about Synergy in a feature interview in RealTime 86. See also page 51 in this edition.

Synergy Percussion, Xenakis & Reich, CarriageWorks, April23-26.

RealTime issue #85 June-July 2008 pg. 48

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

GROWING UP IN SYDNEY’S SOUTH WESTERN SUBURBS I FELT LIKE CONTEMPORARY CULTURE WAS SOMETHING THAT WAS HAPPENING ELSEWHERE: SOMETHING THAT I WOULD ONLY FIND IF I ESCAPED THE ENNUI OF FIBRO AND BRICK VENEER, HOTTED UP CARS AND UNWALKABLE DISTANCES, TO DWELL IN THE RUNDOWN FEDERATION CHIC, COFFEE SHOP INFESTED, WORLD-AT-YOUR FINGERTIPS INNERCITY. HOWEVER AS WE HAVE ALREADY SEEN IN THE PAGES OF REALTIME, SOUTH WEST AND WESTERN SYDNEY ARE CURRENTLY UNDERGOING A RENAISSANCE WHICH EXTENDS TO THE AREA OF NEW MUSIC.

Directed by Matthew Hindson, 2008 marked the second iteration of the Aurora festival (the inaugural event occurring in 2006), and this year it benefited greatly from a new critical mass of arts venues in the West with programs presented at the Campbelltown and Blacktown Arts Centres, Joan Sutherland Performing Arts Centre (Penrith), Parramatta Riverside and the Parramatta campus of the University of Western Sydney. However the Aurora festival is significant not only because of its geographical placement but also due to its endeavour to present new music by living composers, with a healthy number of those being Australian.

Crash, Bang, Swoon

Crash, Bang Swoon by Bernadette Balkus (piano) and Claire Edwardes (percussion) featured the works of six composers, two of whom were so alive as to be present, offering introductions to their pieces. The concert commenced vibrantly with Alex Pozniak’s The Tower of Erosion. Inspired by a rocky cliff face on Sydney’s northern beaches, the piece comprises ‘cells’ of music that build up and disintegrate. The interplay of piano and percussion is fluid, with parallel rhythms breaking up into sharp jazzy syncopations; cymbals and snare rising and crashing like waves, working against the structure, literally and metaphorically. Pozniak spoke of drawing inspiration from noise artists such as Japan’s Merzbow and this contemporary influence came across in his attention to texture, making the work evocative without becoming illustrative.

New Zealand composer John Psathas’ Fragment (2001) is indeed that: short, delicate and sweet. Adapted from a piano duet the piece begins with gentle chords as the vibraphone carries the melodic line, and then the roles are swapped. When asked about the unusual coupling of piano and percussion in one of the made-for-radio introductions (several Aurora concerts were broadcast on ABC Classic FM), Claire Edwardes said that she was particularly attracted to the configuration as it allowed the musicians to be equal partners. Fragment certainly illustrated the lyrical possibilities of this coupling.

Edwardes presented solo pieces for marimba by Japanese composer Keiko Abe. Memories from the Seashore (1986) capitalised on the woody qualities of the instrument—the hollow clatter and deep warm undertones—playing a sweet, almost sentimental motif of rising and falling phrases. The second piece, Vase (1986), was sharper, more intellect than emotion, using harder mallets in an ambivalent ode to a Japanese urn.

US composer Kevin Puts’ Alternating Current (1997) was Balkus’ choice for a solo. Instead of fighting against the weight of the classical piano repertoire, Puts works within the style of three greats—Bach, Beethoven and Prokofiev—but introduces the element of alternating meters and modes. The work is almost pastiche, yet offers far more intrigue—what we think we know and understand is permeated by strange pulses and contemporary melodic phrases that slip around in the work, insistent but hard to catch. It’s also a piece requiring virtuosic skill which Balkus did not fail to deliver.

Cyrus Meurant was also present (along with Pozniak) to introduce the world premier of his piece Ritournelle (2008), interrogating the various musical meanings of that term from a refrain, a song, to an instrumental repeat. The piece played with roles of leading and accompaniment between piano and tuned percussion, with surprising shifts, and dynamic changes from wistful to rousingly robust.

The consummate skills of Edwardes and Balkus were confirmed by the final work, Harrison Birtwistle’s The Axe Manual (2000). This is a difficult to play, some would say difficult to listen to work, spiky and agitated with the percussion and piano joining together through pulses. Edwardes works her way systematically around the range of her instruments from the driving woodblock section to the strident drums, and everything in between, supported and provoked by Balkus’ piano. It was an appropriate conclusion to a smartly curated concert of challenging and beguiling works from two inspiring performers.

Car Orchestra

A truly accessible event in Aurora was the outdoor spectacle of the Car Orchestra, presenting Michael Atherton’s Utility HoRn GrOoVe, a piece for funk band, rap MC’s, a mag wheel gamelan and five fetishised Ford Utilities. Bringing together a range of participants from UWS Macarthur Drum Academy, the Fisher’s Ghost Youth Orchestra and the NSW Ute Club, the event enthusiastically explored the integration of car horns and indeed car ballet into a kind of funky, hip hop, musical melange held together by Atherton as the dancing conductor. A family oriented event, the Car Orchestra certainly broadened the audience demographic for this new music festival.

I couldn’t stay for more of Aurora at Campbelltown Art Centre as I had to hit the highway and flee back into the innercity to catch What is Music? This has been a big month for festivals. Perhaps by the next Aurora, the innercity monopoly on the cultural pulse of the new music and sound art will be well and truly broken. Already in 2008 the NOW now festival relocated itself to Wentworth Falls—maybe the cultural map, (along with many of our assumptions) is finally set to be redrawn.

Aurora, Crash Bang Swoon, Bernadette Balkus, Claire Edwares; Car Orchestra, Utility HoRn GrOoVe, musical director Michael Atherton; Campbelltown Arts Centre, April 12

RealTime issue #85 June-July 2008 pg. 47

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Miles and Zai van Dorssen’s Feuerwasser, What is Music?

photo Harry van Dorssen

Miles and Zai van Dorssen’s Feuerwasser, What is Music?

AFTER THE METAL INFLECTED DRONEFEST OF 2005 WE HAVEN’T HEARD MUCH FROM WHAT IS MUSIC? PRESENTING A FESTIVAL ALMOST EVERY YEAR SINCE 1994, PERHAPS IT WAS TIME FOR THE DIRECTORS ROBBIE AVENAIM AND OREN AMBARCHI TO TAKE A BREAK AND LET THE TINNITUS SUBSIDE. IN 2008, UNDER THE LEADERSHIP OF AVENAIM ALONE, THE FESTIVAL HAS COME BACK AT A STRATEGICALLY SMALLER SCALE YET STILL MAINTAINING A PRESENCE IN MELBOURNE, BRISBANE AND SYDNEY.

I didn’t catch the onslaught of Maxximal Patterorist (Anthony Pateras and Max Kohane), who opened the nine-acts-on-one-night extravaganza at CarriageWorks, as I was tooling down the highway from the funky Ford Utilities (see Aurora review). However I asked one of my esteemed colleagues what it was like and he responded, “scrabbling avant piano hammering welded to grind-core percussion, peppered with quieter, but no less intense, passages of textural exploration.” Sorry I missed it.

I entered the packed venue to see Dale Gorfinkel pottering around like Dr Dean from the Curiosity Show, with a small child on stage holding a tennis ball container over a vibrating contraption that amplified the nasal drone. Gorfinkel’s hacked vibraphone was besieged by plastic cups holding spasm-ing ping pong balls and other clattering bits and pieces. He quietly walked the space, making adjustments, switching elements on and off to create intriguing layers of textural drone. Both Gorfinkel and Avenaim have been seriously exploring this machinic approach to sound-making (in the tradition of Ernie Althoff), and it is engaging both sonically and in its unpretentious task-based performativity. Avenaim’s set up involves an augmented drumkit, from which machinic vibration and microphone feedback elicit deep rich tones. A large part of his piece involved trying to get a recalcitrant motorised drum stick to behave, illustrating the multiple possibilities of chance rhythms and textures. There is something very appealing in the honesty and vulnerability of Avenaim and Gorfinkel’s processes: we see the elements, we see how they come alive, how they come together, and then how they fall apart again.

It was particularly pleasing to hear Marco Fusinato play as prior to this I had only known of his series of ‘blank’ vinyl LPs on which he scratches and carves creating visual artworks. When played these objects make a music of surface noise, clicks, jumps and skips (0_synaesthesia edition, syn 013-16). For this set Fusinato produced bursts of harsh guitar and effects-generated static in which manipulation of volume and timing were paramount. A loud burst—just long enough so that you begin to block your ears—then it stops…followed by a quieter burst, which somehow makes you feel the loss…interspersed with definitive silences. It was a deeply satisfying work showing a compositionally controlled and structured approach to noise.

No event seems complete these days without the laserlight show of Robin Fox, and although I’ve seen and heard it several times, it just keeps getting better. In this version he uses two lasers pointed at the audience, the raked seating enhancing the three-dimensionality as the lasers catch the smoke, carving up the space into shifting sheets and sheering planes. Sonically the work is also getting more intricate, with cross rhythms emanating from the brutal tones that slip in and out of overexcited arrhythmia and pumping beat.

Fox’s spectacle was a hard act to follow for the contemplative piano duo of Cor Fuhler and Chris Abrahams. Fuhler concentrated on piano preparations and ‘electronifications’ while Abrahams worked with the ‘raw’ sound of the grand piano. Initially I felt that I didn’t have the ears left for this piece and the amplification of Abrahams’ piano seemed distancing and unnecessary. However as the work progressed, the sounds of both players mingling in the same mediated space became increasingly rich. The duo’s intense summoning of just the right sonic event and gesture out of the aether, and their tangible sense of playing ‘together’ created a sustained, meditative experience that rewarded the patience it demanded.

Former What is Music? director Oren Ambarchi was the seventh act. His set of luscious, loud, occasionally harsh drones produced by four guitars building into a painfully beautiful squall seemed, by this stage, overly long, though nonetheless momentous. Unfortunately it called upon whatever concentration many of us had left and visiting Italian artist Valerio Tricoli had a challenge to keep the crowd focused. Calling for night (lights out), his set occurred in the glow of a television screen that was tapping into his audio feed. Tricoli has a dark, ambient, almost gothic flavour in his work, with cavernous echoes and shifting vocal fragments. I wish I could say more… but as the programming proves, more is not always the best approach.

The final event sent us out to the vast foyer of CarriageWorks where Miles and Zai van Dorssen had constructed Feuerwasser, consisting of a large swimming pool full of water which, with the encouragement of a blowtorch begins to sport a ring of flames—a fire fountain. By altering the amount of gas and water pressure the artists ‘play’ their construction, making the jets of water and flame rise ever higher into the air. Incorporating the sound of hissing and sharp, cracking explosions as vital molecules within fire and water clash, the piece is awesome, defying our understanding of the elements as a flame dances on top of a ten metre high jet of water.

What is Music? 2008 was a mature and serious beast. (An additional Sydney performance at another venue presented some of the terror rock elements for which the festival is also renowned). Although the event may have sustained attention better with fewer acts, the choice of who to lose from the impressive line-up would have been a hard call. It will be interesting to see whether What is Music? continues to grow old gracefully.

What is Music?, CarriageWorks, Sydney, April 12.

RealTime issue #85 June-July 2008 pg. 46

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Christian Pruvost, MIBEM

photo Andrew McDougall

Christian Pruvost, MIBEM

THE MELBOURNE INTERNATIONAL BIENNALE OF EXPLORATORY MUSIC IS A SIGNIFICANT ACHIEVEMENT IN CONTEMPORARY MUSIC PROGRAMMING, BRINGING TOGETHER AN EXTENSIVE RANGE OF COMPOSERS AND PERFORMERS WITHIN THE OVERALL REQUIREMENT THAT THE MUSIC SHOULD BE EXPLORATORY. COMPRISING 35 PERFORMANCES IN SEVEN CONCERTS OVER FIVE DAYS, AND INCLUDING PERFORMERS FROM ALL OVER AUSTRALIA, EUROPE, THE US AND NEW ZEALAND, MIBEM IS ABOUT A PARTICULAR ATTITUDE TO MUSIC, ABOUT PUSHING BOUNDARIES.

Co-artistic directors Robin Fox and Anthony Pateras invited participation from musicians and composers they had seen or with whom they had worked, particularly in Europe. Fox stated that MIBEM is not intended to be specific to any genre, and the program was almost encyclopaedically diverse, a collection of samples from each composer/ performer’s oeuvre.

I attended two concerts. Saturday evening commenced with Brisbane’s Clocked Out Duo: Vanessa Tomlinson, percussion, and Erik Griswold, prepared piano. Their performance used a variant of a technique seen in their earlier compositions, where drumsticks are attached to long ropes fastened at the other end to a fixed object. As Tomlinson performs, the movement of the ropes simulates the movement of a sine wave and, in this work, the moving ropes strike an array of plates, bowls and other objects on the floor, creating tapping and ringing sounds. Accompanied by Griswold’s piano, the result is an absorbing and satisfying composition—a detailed orchestration of percussive and resonant sounds, using musical and non-musical objects, within an overall musical structure, but which has aleatoric and improvisatory aspects as well as a visual quality.

The second work, by a trumpet quartet of Peter Knight, Tristram Williams, Scott Tinkler, all from Melbourne, and renowned Lille-based trumpeter Christian Pruvost, was all the more evocative for being performed in an eerie darkness—in acknowledgement of Earth Hour, the auditorium was illuminated only by the Exit lights. One trumpet was miked and prepared, looking as though a rubber tube was attached to the mouthpiece, which the performer would bend and pluck and blow through, creating some extraordinary sounds. This group improvisation emphasised technique and, as the performers moved about the space, their breathy sounds coalesced into a strikingly intense and unpredictable whole. Chris Abrahams’ enchanting solo piano performance followed, a work that explored dynamics, tonality/chromaticism and sonority, and was perhaps more cerebral and introspective in flavour than is typical of his ensemble, the Necks.

Berlin sound artist Kirsten Reese’s contribution was a short piece in which she sat at a table gently touching a variety of very closely miked glasses, bowls and other everyday objects. These sounds were processed via a laptop using morphing and delay to layer the sound. The work makes the most of a brilliant PA that can convey every nuance of even the lightest fingering of an object, creating a haunting intimacy that negates the physical distance between listener and performer and makes music out of the ordinary. The final work for the evening was a performance by Amsterdam-based composer Cor Fuhler, who has pushed the prepared piano to new levels, using electro-mechanical devices that sit on the piano strings and create endlessly sustainable resonances and harmonics. Both pianist and mixer, Fuhler stands at the piano, sometimes playing the keys, sometimes touching the strings directly and simultaneously manipulating the devices inside it. The result is a unique sonic language that Fuhler arranges into a delightfully melismatic composition.

Sunday afternoon saw three highly contrasting performances—the Reindeer and Parchment ensemble’s theatre, Jim Denley’s heavily mediated saxophone and an entrancing rendition of Morton Feldman’s Triadic Memories by Adelaide pianist Stephen Whittington. Reindeer and Parchment’s stunning work was a short play in which the main protagonist appears to be ill and is to go to hospital. Her inner agony and her conflict with her partner are portrayed using pre-recorded sound and an array of typical sound-art devices: objects with contact mikes are rattled and scraped and the resulting sounds are processed—by a performer dressed as a surgeon, at a laptop—establishing a series of wry metaphors for the human condition. In parts, sound substitutes for dialogue and the work is a fascinating exploration of how sound art and theatre can be melded to produce a unique synthesis with great potential for further development.

Denley’s solo sax & laptop improvisation conveyed a feeling of deep introspection, as if he was ruminating over the idea of sound as breath, inhalation and exhalation. Moments of sound would emerge and then be abruptly cut off, like confused thoughts trying to emerge into conscious awareness. But as the soliloquy progressed, the sounds developed into more extended musical figures, finding voice, power and release.

But the focal point of MIBEM was Morton Feldman’s epic solo piano work Triadic Memories. Now 27 years old, the work is hardly new, and lacks the technological innovations of much of the MIBEM program. But it places immense demands on the performer, who must use a very different playing technique to realise the minutely detailed score. As a mature work of Feldman’s, it represents the culmination of his own compositional exploration, and is so highly resolved and so musical that technical considerations are subsumed. In just these two concerts, we saw many approaches to the piano and to piano writing: Abrahams’ studied improvisation, Feldman’s extraordinarily refined and subtle composition, and Fuhler’s and Clocked Out’s approaches to preparation, testing the limits of the instrument. As Whittington commented privately, there are many ways to play a piano.

The printed program rarely cited the titles of works performed and, apart from Whittington’s excellent essay on Feldman, lacked contextualising literature, so that MIBEM sometimes had the feel of a workshop. But this biennale is a significant and very welcome achievement. The event wonderfully showcased the possibilities of experimental music and sound art, revealing multiple trajectories and new aesthetics and poetics, encouraging artistic innovation and development and energising audiences. While some musical directions are well established, others are at a developmental stage. But the variety of approaches and often the quality of the works and the performances were breathtaking, variously addressing instrumentation and musical form, modern and postmodern musical traditions, the boundary between sound and music, the nature of performance, the idea of improvisation, the types and uses of notation, the use of recording and synthesising, and the potential of the ubiquitous laptop.

Melbourne International Biennale of Exploratory Music, performers Cor Fuhler, Kirsten Reese, Chris Abrahams, Christian Pruvost/Peter Knight/Tristram Williams/Scott Tinkler, Clocked Out Duo, March 29; Reindeer & Parchment, Stephen Whittington, Jim Denley, March 30; ABC Iwaki Auditorium; MIBEM, various venues March 28 – 2 April 2; www.mibem.net

RealTime issue #85 June-July 2008 pg. 45

© Chris Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Seal Wife

photo Joe Pasquale

The Seal Wife