Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

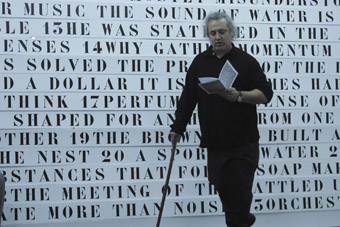

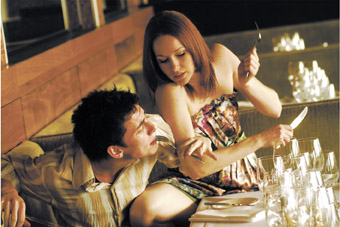

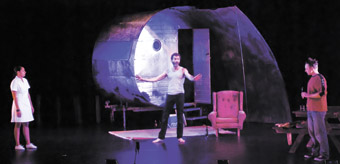

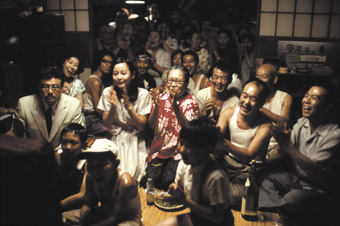

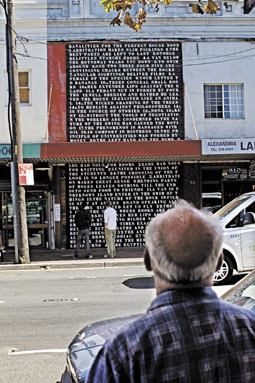

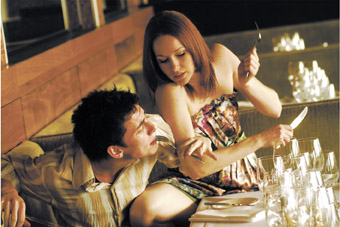

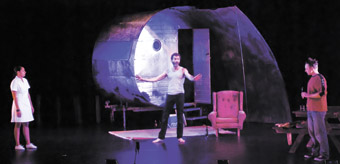

Embracing the work’s disturbing structure, Jonathan applauds writer and co-director Richard Murphet’s The Inhabited Man as a “dense, beautiful yet traumatising dramaturgical essay” about the psychological damage imposed by war.

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008

–

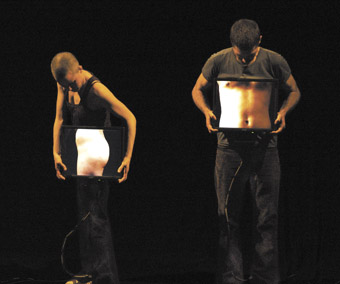

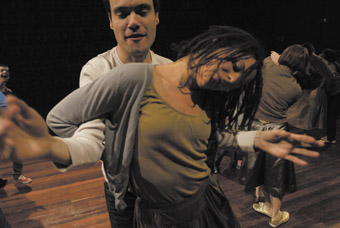

Top image credit: Merfyn Owen (foreground), The Inhabited Man

Shifting Intimacies

photo David Campbell

Shifting Intimacies

KEITH ARMSTRONG AND GUY WEBSTER COLLABORATED WITH CHARLOTTE VINCENT AND THE DANCER TC HOWARD TO PRODUCE SHIFTING INTIMACIES FOR A SHOW AT THE ICA IN LONDON IN 2006. AT THE BRISBANE FESTIVAL IT IS ON FOR A FEW HOURS SPREAD OVER FOUR DAYS. BOOKINGS MUST BE MADE. SINGLE VIEWER AT A TIME. TEN MINUTE SLOTS. THEY FILL UP PRETTY QUICK.

You turn up at the Judith Wright Centre, grab a drink, sit in the foyer and wait your turn. The usher comes out and quietly offers up the now mandatory fear of litigation instructions on responsible behaviour when encountering an installation. Emboldened by caveats I enter the room alert to the terrors that might lie ahead. The space is darkish and semi-industrial—silver aircon ducts, chunky pillars. Shifting Intimacies was originally designed for ‘the ideal black box’ (painting = the white box; installation = the black box. The white box isolates the object, the black box isolates the viewer). Although it does change the piece from its original conception the space works. There’s something shady and transitory about the combination of slick tech aesthetic and low rent industrial—sort of bump in, bump out biotech.

The floor is covered in white dust marked by the footprints of previous visitors. There are two discs at either end of the space, each one a couple of metres across. The closest disc is a sand covered platform raised to about knee height, the further one a disc of white dust laid out on the ground and defined by a rim of deeper dust. Both discs glow with video projections. Onto the raised disc is projected a dancer, life size, colour muted close to grey scale. The dancer spins and contorts within what looks like a very amniotic fluid. The face is obscured, the body de-identified. Motion is slow, there are pauses then rapid jerking shifts. Tissue filaments, like sheets of skin, float about in the fluid, disintegrate and trail the motion of the limbs. If the raised disc is gestation then the second disc is erosion. Again the dancer is anonymous and seen from above. But this time the image is repeatedly broken down into noise generated by the microbial growth patterns of an AI algorithm. Even though the images are large, the effect is of looking through a porthole or microscope onto a private mystery. The viewer presence is acknowledged but the dancer’s face is always turned away, there is nothing personal or dialogic happening.

Throughout all of this is the sound design—low rumbles, spatially driven static, unnerving resonances. Organic, layered, moving about, buzzes and drones. At times I wander away from the image and just enjoy the sound, which seems to be more responsive to my position in the space than the images ever were. It is as if the sound forms an enclosure within which the dancer acts out a private and necessary cycle.

At the end of the timeslot a light goes on in the corner of the space. One walks up a short flight of stairs to a platform overlooking the disc of the eroded body. But now the body is fully revealed, face down, knees clenched, crouching. You reach into a bowl and grab some dust and cast it onto the figure below. More dust blows in. Soon there is enough dust to erase the figure completely.

Gina Czarnecki’s Contagion provides a very different experience. It is designed around ideas of viral transmission—epidemics of disease and fear. The space is cubic and black, large screen at one end. The screen looks like a giant monocular scope, red crosshairs slowly moving across the surface. Billowing smoke tracks each person’s movement through the space—coloured according to their entrance point and beautifully detailed. And, underneath the smoke trails, a movie of a surveillance operation plays out, figures glowing hot in the long wavelengths of night vision.

Contagion presents a traditional theatric and game-like space with the action split between the presentation on the screen and the audience out front. People try and interact with the system by moving about the space to drive movement in the smoke trails. But one cannot move about the space and interact in a completely natural fashion as the head must be facing forward and angled upward to view the screen, which is quite high. It’s like being in the front row at the pictures. And the look of people all facing the front moving about with their faces craned upward at an uncomfortable angle doesn’t gel with the elegance of the imagery. There is nothing intrinsically wrong with a work that sets up some sort of disjunction or discomfort between action and response, but there must be some sort of conceptually coherent payoff for doing so. Unfortunately in Contagion there is no obvious payoff that links audience motion and orientation to the conceptual domain.

In the end, Contagion feels flat, any emotional or aesthetic engagement dominated by the clumsiness of the interaction. By contrast, Shifting Intimacies does not feel particularly interactive at all—the experience is primarily poetic, and more powerful for that.

Keith Armstrong: www.embodiedmedia.com

Charlotte Vincent: www.vincentdt.com

2008 Brisbane Festival: Shifting Intimacies, artistic directors Keith Armstrong, Charlotte Vincent, sound director Guy Webster, TC Howard, Judith Wright Centre of Contemporary Arts, July 30-Aug 2; Contagion, Gina Czarnecki, The Block, QUT, Brisbane, July 18-Aug 3

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008 pg. 35

© Greg Hooper; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

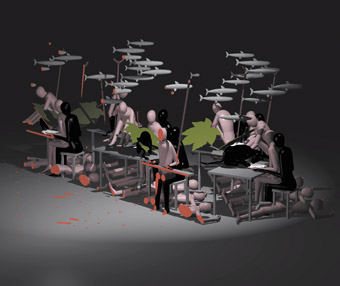

Yves Netzhammer, Die Subjektivierung der Wiederholung/The Subjectivisation of Repetition, Project C

NEW MEDIA ART HAS A VERY SHORT HISTORY ON CHINA’S MAINLAND, WHERE MORE TRADITIONAL FORMS SUCH AS PAINTING AND SCULPTURE TEND TO HOLD SWAY. SO, IN THE LEAD UP TO THE OLYMPIC GAMES, IT WAS A SURPRISE TO SEE BEIJING’S NOTORIOUSLY CONSERVATIVE NATIONAL ART MUSEUM OF CHINA (NAMOC) UNVEIL SYNTHETIC TIMES, A MAJOR SURVEY OF GLOBAL MEDIA ART PRACTICE.

The China-born, New York-based curator of Synthetic Times, Zhang Ga, has been involved in nurturing China’s nascent digital media scene for several years. “I was in China in 2003 and I looked around in Chinese universities and talked to a lot of artists”, recalls Zhang. “I realised their understanding of new media art really remained at the level of DVDs, digital photography, a little bit of 2D interaction and Flash. I thought it was important to introduce some of the most cutting edge, current media art production to China.”

During that visit, Zhang was invited by Tsinghua University to help introduce media art practices to Beijing’s creative community, which led to the inaugural Beijing International New Media Art Exhibition and Symposium in 2004. In 2006, the newly appointed NAMOC director, Fan Di’an, approached Zhang to curate a major exhibition of media art as part of the Olympic cultural program, signalling a significant shift in NAMOC’s curatorial philosophy. “[Fan Di’an] inherited a museum which is quite traditional”, says Zhang, “so I think he wanted to do something that is cutting edge and more appropriate for contemporary dialogue.”

Synthetic Times would have been a major event in any country, let alone one in which the concept of media art is barely known, and the sense of excitement and interest among visitors was obvious. Over 40 works filled the museum’s ground floor and spilled onto the building’s forecourt, including everything from kinetic sculptures to interactive installations. There were some familiar Australian contributions, including Transmute Collective’s Intimate Transactions (2005) and Stelarc’s Prosthetic Head (2003-08), smiling down on crowds near the museum entrance. [Australia’s MAAP was one of 17 international media arts organisations that collaborated on Synthetic Times. MAAP’s retinue also included Korea’s Kim Kichul and Singapore’s Paul Lincoln whose Citizen Comfort is described below.]

the recording eye

Some of the works that resonated most with the pre-Olympics Beijing setting were those dealing with digital image-making technologies. On the one hand these technologies, like film and photography before them, offer the tantalising possibility of capturing something of our history for posterity. The elusive nature of this promise felt all the more poignant in a city where physical traces of the past are being erased daily. On the other hand these same technologies are being increasingly utilised to observe, record and classify our movements.

blendid collective, Touch Me, Netherlands, 2004

courtesy the artists

blendid collective, Touch Me, Netherlands, 2004

The blendid collective’s Touch Me (Netherlands, 2004) was a simple but affecting interactive installation, in essence a giant scanner fixed to the museum’s wall. Every so often a bright shaft of vertical light passed across the scanner which recorded a ghostly impression of spectators who pressed themselves against the glass. Each new sweep of light saw the previous image erased and new impressions recorded. If no-one pressed against the glass, the screen cycled through old images, creating a layering effect akin to a series of digital Turin shrouds. Initially amusing and a lot of fun, the blurry indistinct images took on a haunting air after a time, like ghosts reaching into the present from a murky past.

Nearby, Mariana Rondon’s You Came with the Breeze-2 (Venezuela, 2007-08) dealt in similarly fleeting imagery. Two robot arms suspended from a large metal frame each ended in a ring roughly the size of a football. The rings were dipped into bowls of soapy fluid, before being swung into the centre of the frame, where fans blew on the liquid to form giant bubbles. Clouds of mist were sprayed into the bubbles and shimmering images projected from the rear briefly appeared on the water droplets before the bubbles burst, the mist dissipated and the entire process began again. Images included a baby, a giant eye and, rather incongruously, a chicken. In the corner of the metal frame, indistinct naked figures were projected onto a solid plastic sphere, creating the effect of human forms swimming in a fish bowl. The work beautifully evoked the transient nature of images, suggesting that for all our archival technologies, time is always at work, eroding our attempts to fix memories.

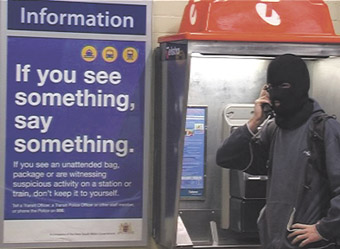

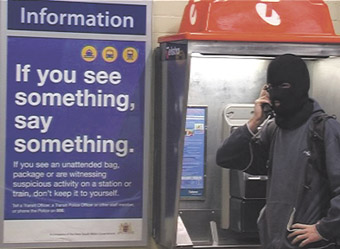

David Rokeby’s Taken (Canada, 2002) was one of the older works at Synthetic Times, but it certainly struck a chord in a pre-Olympics Beijing as surveillance cameras sprouted like mushrooms across the city. It comprised two screens, the right one a fuzzy yellow surveillance image of the crowd in front of the work, captured by a camera in the corner. The image depicted gallery patrons in real time, but also retained traces of past observers in the form of spectral shadows. Periodically a small rectangle, akin to a gunsight, would single out an individual and relay their close-up to the blue-toned screen on the left. Words and phrases, sometimes amusing, sometimes sinister, flashed above the close-ups, such as “Unconcerned”, “Completely Convinced”, “Implicated”, and “Deeply Suspicious.” Every so often, dozens of the close-ups would appear together, like a mosaic of animated mugshots.

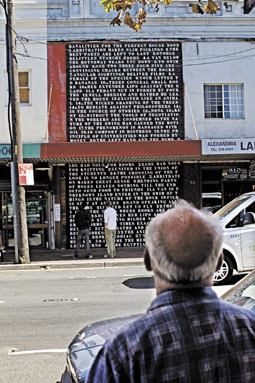

Paul Lincoln’s Citizen Comfort (Singapore, 2008) also reflected upon the way camera technologies assist in ideologically determining space. A small screen sat before a comfortable armchair and hat stand, signifiers of cosy domestic security. The screen showed the space in front of the armchair, but if the viewer picked the screen up and pointed it at the small air-conditioning holes in the museum’s wall, words in red block letters appeared in the televisual space, such as “United”, “Race”, “Democratic”, “Prosperity”, and “Nation.” A large flat screen fixed to the wall behind the armchair relayed the image appearing on the smaller screen, creating a hall-of-mirrors circuit of surveillance. Like David Rokeby’s Taken, Citizen Comfort interrogates how imaging technology both records an impression of the physical world and ideologically informs how we understand ‘reality.’

works of disquiet

A melancholic or sometimes menacing air lurked below the playful surfaces of the installations described above, but two works in Synthetic Times were unambiguously disquieting. The first was Cloud, by Chinese artist Xu Zhongmin (2006). A large cone spun as lights strobed and small child-like figures emerged from the cone’s top, tumbling and diving down the sides before dropping like rain from the base. Occasionally the spinning stopped, the strobing ceased and the children became stationary figures poised mid-action. Then the spinning resumed and they continued their lemming-like tumbles. Wide open to interpretation, Cloud was a disturbing portrayal of futile, repetitive mass action.

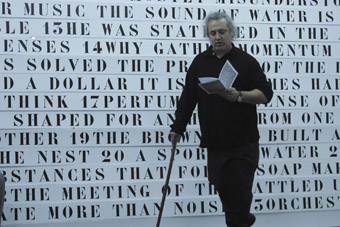

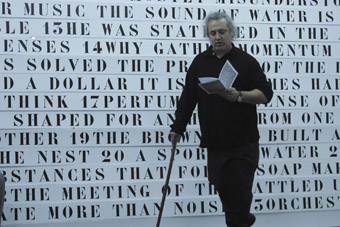

Yves Netzhammer’s The Subjectivisation of Repetition (Switzerland, 2007) was one of the exhibition’s more conventional works in terms of form, but also one of the most intriguing. A large installation comprising a main screen and three smaller screens on the opposite wall, viewers had to climb a sizeable mound made from timber in the centre of the room, as if gathering to hear a Biblical parable. The walls were filled with the silhouettes of strange creatures and vegetation, and maps of the world. On the main screen small animated vignettes played out in sequences lasting from a few seconds to a minute or so. A featureless black figure sat behind a white one, rubbed his finger on a blood red map of the world, forced out the white figure’s tongue and wiped it with his reddened finger tip. A dolphin swam beside a man walking on shore, until the creature hit a red pipe and went belly-up while the man walked on oblivious. A map of the world folded in on itself. Many of the aphoristic scenes were replete with acts of sanitised, clinical violence, the animated figures playing out a seemingly endless cycle of attraction, repulsion and struggle for domination with an unnerving air of calm. The rear trio of screens showed similar scenes. The scenarios felt both familiar and strange, like half remembered dreams. The Subjectivisation of Repetition was a beautiful, disturbing interrogation of our era’s contested signifiers, mediated violence, and sense of impending disaster.

wakeup call for local artists

Zhang Ga hopes Synthetic Times will “act as a wakeup call” for Chinese artists, who he believes have become too comfortable in China’s financially flush art scene. “Everybody’s making so such money, without really reflecting on what they actually contribute to the language of art…[This exhibition will] let people realise there are works that are very sincere, very serious, and require a lot of dedication.”

Of the exhibition’s more general impact, Zhang says, “Art is something that changes you over time; the way you look at the world, and eventually the way you perceive reality.” Art’s expansive possibilities are particularly vital in China, where the government severely restricts the exchange of ideas in public discourse. It was ironic, however, that many of the works in this “Olympics Cultural Project” utilised and interrogated the same technologies that were being rolled out across Beijing in the months preceding the Games, as authorities subjected the capital to an unprecedented level of electronic surveillance. Of course, this simply brought the city into line with long-established levels of ‘security’ in the West. It seems technology isn’t the only thing converging in our networked, closely monitored world.

Synthetic Times—Media Art China 2008, curator Zhang Ga, National Art Museum of China, Beijing, June 10-July 3, www.mediartchina.org

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008 pg. 32

© Dan Edwards; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Real Thing, photo courtesy the artist

When you peer into a kaleidoscope, into the mirrored surfaces on which tiny fragments of coloured glass spark and rattle, and raise the toy against the light, you don’t expect to see yourself. But in Sydney artist Jordana Maisie’s The RealThing, that’s what you get, the real you, captured by video and fragmented by soft and hardware magic into an infinite number of glorious mandalas.

Significantly Maisie’s work is on a human scale. The large screen facing you is contained in a deep circle of thin, bright metal, a camera hanging discreetly just above. Your actions become experimental as soon as you realise that the patterning on the vivid screen is evolving at the same rate as your own movement. You adjust relative to the camera. You discover that you can position hands, face, torso, objects with astonishing results, as surreal, temporary still lives or slow, lyrical dances.

Instead of the way you’d hold a kaleidoscope, in the Real Thing it’s the way you hold yourself, and far more interesting than, say, the fairground’s distorting mirrors. Here, Jordana Maisie the maker turns us into co-maker and subject at once. But it’s no mere narcissistic delight, because there’s no coherent mirroring of the self. Rather, we’re offered the perverse pleasure of dissolving and rearranging ourselves.

To see The Real Thing and to read about Jordana Maisie (she has a Masters Degree of Digital Media from Sydney’s College of Fine Arts and studied photography at the Glasgow School of Art) and forthcoming shows and collaborations, go to Studio.

Jordana Maisie, The Real Thing, sculpture, interactive video installation, Black & Blue Gallery,

Sydney, Aug 29-Sept 14; www.blackandbluegallery.com.au

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008 pg. 33

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

George Khut, The Heart Library Project: Biofeedback Mirror (2008)

photo Silversalt Photography

George Khut, The Heart Library Project: Biofeedback Mirror (2008)

AFTER NOT INCONSIDERABLE HARD TIMES, NEW MEDIA ARTS APPEAR TO BE ENJOYING NEW FAVOUR AND SOME RE-BRANDING. GROWING VISIBILITY, BIG PRIZE MONEY, SIGNS OF RE-GROWTH IN THE TERTIARY EDUCATION SECTOR AND THE EXPANDING INTERNATIONAL PRESENCE OF INDIVIDUAL AUSTRALIAN ARTISTS ARE SIGNS, HOPEFULLY, OF BETTER TIMES. EXPERIMENTA’S EXTENSIVE FORAYS ASIDE, EXHIBITIONS OF NEW MEDIA ARTS HAVE BEEN RARE, SO IT WAS EXHILARATING TO BE ABLE TO ENJOY MIRROR STATES, CURATED BY LIZZIE MULLER AND KATHY CLELAND, AT THE CAMPBELLTOWN ARTS CENTRE. IT’S A SERIOUSLY ENGAGING SHOW THAT OFFERS A RANGE OF INTERACTIVITY WITH NEGLIGIBLE MOUSING AND NOT A LITTLE PHYSICAL AND MENTAL ACTIVITY.

As for re-branding, the ‘new’ appears to have been clipped off ‘new media arts’ leaving us with the somewhat ambiguous ‘media arts’. Exactly who did the scissoring is not clear, perhaps it’s one of those meme things, but it’s certainly no fait accompli: the Queensland Premier’s National New Media Art Award is hanging onto the label with a $75,000 prize for the best work from a select group of artists. Certainly the argument about the ‘newness’ of new media arts has been long argued for and against, including on these pages. Those for ‘new’ argued that the constant inventiveness in electronic technology and art’s engagement and furthering of it justified the label; those against had seen it all before, all the way back through pre-digital multimedia, Expanded Cinema, Fluxus, Dada, Wagner…And then there were the new media artists who just wanted to be artists.

Although university courses are more likely to be titled in terms of electronic art, digital arts and still occasionally as new media arts, there’s a drift to ‘media arts’ in common parlance, encouraged doubtless by various kinds of platform convergence and the out and out digitalisation of the cinema. Media arts now encapsulates everything from photography to pre-cinema to film to video to gaming to Second Life to mobile phone and GPS art, and the big screens proliferating in public spaces across the world. [The international Urban Screens Conference is being held in Melbourne this month. Read Ross Harley’s report in RealTime 88.]

Meanwhile, film schools are pushing their media arts credentials. The Australian Film TV and Radio School (AFTRS), for example, has announced Graduate Diploma courses specialising in Game Design and Virtual Worlds, building, says Peter Giles, Director of Digital Media, on “AFTRS’ expertise in computer animation and interactive writing…coupled with our experience of rapidly prototyping digital content through our Laboratory of Advanced Media Production (LAMP).” The new federal film agency, Screen Australia (a merging of the Australian Film Commission, Film Australia and the Film Finance Corporation) has put out a statement of intent for public comment forecasting not just funding film but developing a broader notion of screen in a context of media convergence [www.screenaustralia.gov.au/soi].

For the $75,000 biennial acquisitive Premier of Queensland’s National New Media Art Award, nine artists have been short-listed: Peter Alwast (QLD), Julie Dowling (WA), Anita Fontaine (QLD/Netherlands), David Haines and Joyce Hinterding (NSW), Natalie Jeremijenko (QLD/USA), Adam Nash (VIC), Sam Smith (NSW), John Tonkin (NSW) and Mari Velonaki (NSW). It’s an intriguing range of artists, a broad notion of the field bringing together some recent converts to media arts alongside established practioners. The award exhibition will be on show in the Media Gallery, Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA) until February 8 next. The selection of artists was made by invitation and will be judged by Melinda Rackham (ANAT), Liz Hughes (Experimenta) and Tony Ellwood, Director QAG, while the $25,000 travel and study scholarship for an emerging new media artist living and working in Queensland was open to application.

There are other positive signs. ACMI’s Game On, a hands-on exhibition tracing the history of computer gaming, was a monster success, drawing record crowds. The Australia Council’s Inter-Arts Office pulled an unusual degree of media and online attention on the announcement of the successful applicant [the team of Justin Clements, Christopher Dodds and Adam Nash] for a residency in Second Life [see the interview with the Office’s Ricardo Peach on page 36]. Australia’s MAAP continues to work the Asia-Pacific region, participating in China’s Synthetic Times [see Dan Edwards’ report on page 32]. The Australian Network of Art & Technology offers artists key support through travel funding, workshops and its administration of the art-science program Synapse. Experimenta has upped the ante by titling its big touring shows as biennales. NSW’s dLux Media Arts has been particularly active in promoting the potential of locative media.

Meanwhile, Australian media artists roam the world, invited to major media arts events like Ars Electronica and ISEA [see reports on the 2008 festivals in RT88] or appearing in notable exhibitions. Recent travellers include Josephine Starrs and Leon Cmielewski with their new work, land [sound] scape (2008), chosen for the Guangzhou Triennial, China; Lynette Wallworth whose work has featured recently at London’s BFI and now the 2008 Melbourne International Arts Festival; and Transmute Collective, whose Intimate Transactions has taken them recently to the UK, Europe and USA [director Keith Armstrong’s Shifting Intimacies is reviewed on page 33].

If recent years have been frustrating for new media artists—watching ACMI turn predominantly to cinema before Game On, universities shutting down new media arts departments or forcing mergers with sometimes unlikely partners, the absorption of the Australia Council’s New Media Arts Board remit largely into the Visual Arts Board—things seem to be looking up. A more integrative vision is also evident. As Ricardo Peach makes clear, several of the Australia Council artform boards have partnered media arts projects and have individually addressed the potency of new technologies for their constituencies. I was pleased to be invited to launch the University of Technology Sydney’s Centre for Media Arts Innovation (see p42), which aims to work across disciplines and artforms within UTS and generate dialogue and ventures with sectors outside the university and the general public [www.communication.uts.edu.au/centres/cmai].

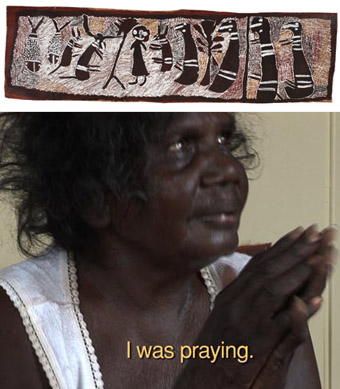

In Indigenous media art, the winner of the Wandjuk Marika 3D Memorial Award in the 2008 Telstra Aboriginal Art Awards, went to Nyapantapa Yunupingu, a Yolngu artist from Yirrkala, for her installation (natural pigments on bark, moving image) entitled Incident at Mutpi (see page 10). The filming for the work was done at Yirrkala’s new multimedia studio, the Mulka Project.

All these signs of new media arts life (Lyndal Jones’ RMIT Vital Signs conference in 2005 [RT 70, p35] in the wake of the demise of the New Media Arts Board had left not a few us fearing a fatality), not least a major media arts prize with ‘new’ in the title, suggest room for optimism even if the uptake of media art in galleries, proliferating video art aside, is still very slow. It’s good then to know that Campbelltown Arts Centre and GoMA are creating new benchmarks with a determinedly national approach (for a state premier’s prize) in GoMA’s case and a Pacific Rim one in Mirror States.

mirror states

Kathy Cleland and Lizzie Muller have drawn together works familiar and unfamiliar, all deserving of a wider audience. The spacious Campbelltown Arts Centre allows each work plenty of room to work its magic in a thematically rigorous show that seduces the viewer-participant into reflecting on their self perception with humour, trepidation and deep seriousness.

At the gallery’s entrance we are welcomed face to face by a video of the head of a ventriloquist’s dummy (from Bioheads, Anna Davis, Jason Gee, 2005-08). In appearance it’s a simple work displaying the usual mechanics of manipulation but, with restrained digital animation, the eyebrows seem to rise that little bit higher, the smile wider, the jaw deeper as the dummy intones deviantly mainstream self-help mantras: “I sing beautifully and am financially blessed”; “it is abnormal to be sick”; “poverty is a mental disease.” The extra animation touches and the eye to eye positioning of the screen make the doll just that little too real. You feel vaguely implicated, a tad grubby, for even staying to listen to the rubbish he spouts. That’s not me in the mirror, you hope.

Even more alarming, filling the main entrance, floor to ceiling, is a huge, long, pink inflatable finger, Sean Kerr’s Klunk, Clomp, Aaugh!—Friends Reunited (NZ, 2008). It seems to have a life of its own, but you work out fairly quickly that if you turn to two small screens with large black dot-like eyes, in the corner and gesture you can perhaps influence the rise and fall of this phallic toy —shocking inflation, too big!, and worrying deflation, almost flat to the floor. You want to turn to the nearby gallery staff and say I didn’t do it, but then you think, Did I? Is it giving us the finger for imagining we’re on top of the new technologies? Is it mirroring our foolishness, our wishful thinking?

Deeper into the foyer, Hye Rim Lee’s Powder Room (2005, USA/NZ) displays a face, seen from various angles, being digitally made over on four small circular screens. The face is analysed and gridded so we witness the precise topography on which changes will be wrought—the slow re-drafting and fattening of lips or re-working of eyebrows and nose. It’s clinical but leavened by familiar, cute Asian-style graphic art which almost, but not quite, guts the horror of the cosmetic surgery reality behind this ‘mirror’ evocation of a possible future self. This is not me, but it might be the kind of hypothetical modelling offered potential makeover customers. Things get weirder when we’re drawn to an adjoinging large room where, in Lash, a huge version of the face fills a circular screen, engaging us eye to eye, waves of soft colour emanating from behind the coiffure, head rolling, a gentle moaning and then eyelids fluttering with an accompanying, alarming machine gun ratatatat. This is mechanistic animation, but like the ventriloquist’s doll, there’s a disturbing sense of being regarded, played to, in the loop of being estimated, or seduced.

In a spare, white room, two wheelchairs lurk on a floor littered with paper strips—that’s it. No screens. Mari Velonaki’s Fish-Bird: Circle C-Movement B (2005), created with a group of roboticists, is by now an old favourite but still manages to surprise as these empty conveyances with apparent lives of their own seem to uncannily sense your movements as they follow, back off or turn away at the last moment: they seem to mirror your intentions and expectations. Meanwhile they’re pumping out messages to each other on small strips of paper which they dump on the floor or which we bend to gratefully receive as gifts from another intelligence. One printout suggests I’m being addressed directly: “Fish is not talking to me.” The desire to be mirrored by another (the phenomenological loop that builds and sustains our sense of self), even if by a wheelchair, makes for an experience both uncanny and self-critical.

Mari Velonaki, Circle D: Fragile Balances (2008)

photo Silversalt Photography

Mari Velonaki, Circle D: Fragile Balances (2008)

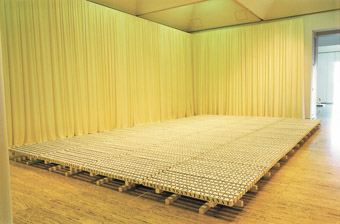

In a nearby room, the wheelchairs have been replaced by doppelgangers, two immaculately crafted timber boxes with crystal screens on four sides (Circle D: Fragile Balances, 2008). You pick one up and, as you gently turn the box around, writing unfolds in a similar style to the wheelchair printouts. At the same time you glimpse responses on the second box as a lateral, poetic conversation unfolds. It’s like coming across an expensive Victorian pre-cinematic toy that’s been digitalised. It’s an odd, and again implicating experience, holding an intelligent box as it writes, “If our eyes should meet, what would we have in common?” Exactly. Mari Velonaki is one of the contenders for the Queensland Premier’s New Media Arts Prize, so this work will be on show at GoMA.

I’ve also seen Alex Davies’ Dislocation (2005) before, but again it’s surprising to find your perceptions nonetheless tossed about as you bend to peer into one of four small peephole screens that reveal the room behind you. Suddenly, on the screen, someone enters—other gallery goers, a guard and a dog, variously indifferent, affable, vulnerable and perhaps dangerous—but, you turn quickly, to find there’s no-one there. The screen is an unreliable mirror. You wonder how you’ve triggered these ghostly intruders.

Canadian David Rokeby’s Giver of Names (1991-2004) is an even stranger experience. Brightly coloured toys litter the floor. You arrange them on a plinth. A camera and computer read your arrangement and interpret and transform it onto a screen above, thickening and varying the colours quite beautifully. Meanwhile the computer is converting its sense of the image into extremely lateral text, readable on another screen: a rubber duckie on the plinth becomes “that is the mountain girl.” This is no mere mirror of our actions rendered interactively, but an evocation of the challenges and limits of translation.

The closest we get to something like a true reflection is John Tonkin’s time and motion study (2006), the latest version of which will also appear in the New Media Art Prize show at GoMA. In a long, narrow, dark room you move towards a screen (and camera above it) on which fragments of a row of overlapping faces are fading and over which your own multiplies moment after moment, in portraiture of now and now and now and before, before, before…and, as you shift before the lens, now again. As in the Rokeby, there’s an absence of literal translation, the imagery is dark, grainy, not distorted but curiously Francis Bacon-like, each duplicated face locked into a kind of rictus in an infinity mirror, trailing light years away.

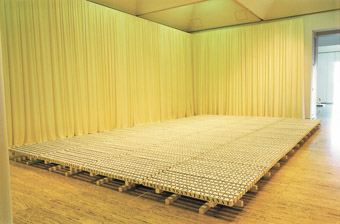

If George Khut’s previous works (Drawing Breath, 2004-06 and Cardiomorpholgies, 2004-07) have allowed the heart beat and breathing of individual participants to modulate his visual and sonic imagery, this new work, The Heart Library goes much further in transforming states of being into artistic mirrorings and with greater audience-as-co-maker participation. The visitor retires to a gently darkened space, stretches out on a cushioned platform, holds a sensor in each hand and encounters themself, life size, on a screen above. The pace of the heartbeat yields a flow of snow or blossom-like drift over the body and changes in colour and sound—for some participants the variation is subtle, for others relatively dramatic in intensity.

On leaving the space, you enter another hung with full-scale drawings by participants reflecting what they’d just experienced. A number are distinctive artworks and all are revealing about where people see their bodies centred or off-balance, wounded, anxious or enjoyed. Khut and collaborators (Caitlin Newton-Broad, Greg Turner and David Morris-Oliveros), have video-ed some of these drawings and recorded the makers explaining them. These, with headphones, are available on small wall players. The notion of a new kind of library is fully and immersively realised, and goes a step further in its offer of creativity. The artist Khut provides the framework within which others can make art of their bodies and their perceptions. As Anneke Jaspers writes in the Mirror States catalogue, “…the addition of a social dimension reconfigures interactivity within an inter-subjective rather than strictly technolgical framework.” We feel of works of art we like that they mirror something about us, even if we don’t like what we see, but in The Heart Library we are the actual subject of the work. Our heart beat turns us, thanks to Khut’s artistry, into co-maker while being audience to our own experience. Those who draw and speak become interpreters of that making. The hung paintings and screen recordings are left for others to share and compare as the mirroring multiplies.

Mirror States, curators Kathy Cleland, Lizzie Muller, Campbelltown Arts Centre, Sydney, July 18-Aug 24; MIC Toi Rerehiki, Auckland, New Zealand, May 16-June 28

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008 pg. 34

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Dan Monceaux, Niagara Falls 2007

THE OPENING MONTAGE OF DAN MONCEAUX AND EMMA STERLING’S SUPERMARKET IS FULL OF FAST CUTS, STARS, LIGHTS AND CARS, DOUBLING AND REPEATING. A SEQUENCE OF NIGHT-TIME CITYSCAPES TURN AROUND THE SCREEN. THE FOOTAGE SHIFTS FROM FILMIC TO THE OPEN SHUTTER BLUR OF VIDEO. LINES OF COLOUR SLOWLY DRAG ACROSS THE FRAME. LIVE FEED OF MONCEAUX’S HANDS, MIXING THE SOUND, DISSOLVES BRIEFLY IN AND OUT OF THE SCENE. THEN WE’RE TAKEN ACROSS A BRIDGE, MOVE INTO A TUNNEL. THE TITLE, IN THICK BLACK RETRO FONT, CROSSES OVER A LARGE WHITE SPACE. BLACK AND WHITE GEOMETRIC PATTERNS TAKE OVER. THERE’S A CROSS-SECTION OF A BRAIN, LIKE AN X-RAY. BUBBLES FALL. THEN A WARNING THAT THE FILM MIGHT CAUSE INDUCE EPILEPTIC EPISODES CUTS HARD ONTO THE SCREEN.

These eclectic media are driven by the audio beat: electronic music composed, performed and mixed by Monceaux. Meanwhile a male narrator, like documentary’s ‘voice of god’ and in a style reminiscent of cinema advertising and infomercials, informs us that Supermarket “speaks up for consumer interest…supplying several million people with the truth”, “for men and women in all walks of life.”

Supermarket unfolds as a series of chapters, or sections. Early on I’m wondering what will hold them all together. Even though it is described as non-narrative the approach to genres and styles fragments the work. There are a number of Monceaux-Stirling vignettes. One section comprises numerous shots of people wearing uggboots framed to cut off the person at the knees, keeping identities censored, or avoiding, like television news, the need for permission to shoot. At best the uggboot works like a ‘quirky’ homage to American avant-garde ‘catalogue’ films. This chapter is followed by a romantic comedy, shot on Super 8 for Shoot the Fringe. It tells a story about two balloons meeting in The Garden of Unearthly Delights. While a sweet interpretation of falling in love, its classical narrative form stands out amongst the otherwise experimental use of footage.

“Men and women from all walks of life” are presented to the audience through a combination of archival and borrowed footage. However, unlike, say, Tracey Moffatt’s Love (2003), which liberally takes from Hollywood, Supermarket doesn’t appear to have a sense of direction. Early on there is a sequence of images that runs approximately in this order: an Aboriginal man hunting with a spear, kangaroos, the face of a native American, an eagle, a bull running, snow on branches, time-lapse footage of Uluru, and smiling black children who wave at the camera. Are the artists calling into question the ethics of representation or are they unconsciously contributing to a colonialist perception of Aboriginal people? And what about the generalising association the sequence makes, likening the indigenous peoples of Australia with those of America?

Other sections of Supermarket either rely on audience cinematic memory or assume that the audience doesn’t have any. Scenes from Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), 1970s martial arts and other films are re-cut. While the artists are perhaps concerned with deconstructing authorship the sequences seem to bear no relationship to an overall theme, except to say that everything can be accessed and is all available for consumption.

In keeping with the tradition of experimental filmmaking, Monceaux and Sterling do take risks. Supermarket has been created under the radar. It’s low budget, asynchronous and amorphous. It’s openly in development, always in flux, and this allows the artists plenty of room. At times Supermarket offers images that stand alone as remarkable moments. It is worth noting that the filmmakers come from a visual arts background and their documentary, A Shift in Perceptions (2006), about the experiences of three visually impaired women, has done very well in both national and international film festivals [RT75, p50].

It’s ironic that the makers of Supermarket claim to comment on the emptiness of consumerism and yet present their work in some way as a ‘must have’ consumer event. Perhaps that’s the incongruity of making art about society valuing the superficial while needing to market the work to secure an audience. Or if irony is part of the artists’ intentions why am I am still wondering what I’m missing from the Supermarket experience? If, as Monceaux explains, their objective is “not to sell you anything substantial, just the image of an empty shopping trolley”, then it fulfils its sales pitch, paradoxically leaving the audience with the same old consumerist dilemma.

South Australian Living Artists festival: Supermarket, artists Emma Sterling, Dan Monceaux, camera, editor Emma Sterling, music, sound Dan Monceaux, producers Emma Sterling, Dan Monceaux; Mercury Cinema, Adelaide, Aug 9

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008 pg. 35

© Jessica Wallace; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

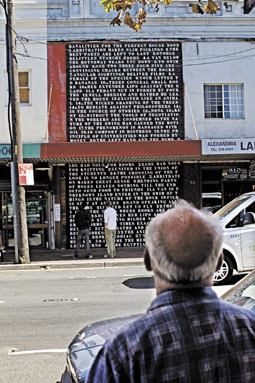

Babel Swarm

RICARDO PEACH IS THE PROGRAM MANAGER FOR THE AUSTRALIA COUNCIL’S INTER-ARTS, OFFICE. PEACH IS AN ENGAGING MEDIA ARTS ENTHUSIAST WHO HIMSELF ENJOYS A SECOND LIFE. WE MET TO DISCUSS HOW, IN 2007 THE AUSTRALIA COUNCIL FOR THE ARTS BECAME THE FIRST NATIONAL ARTS FUNDING BODY TO FUND AN ARTIST RESIDENCY IN SECOND LIFE. THE WINNING TEAM, WRITER JUSTIN CLEMENS, VISUAL ARTIST CHRISTOPHER DODDS AND SOUND ARTIST ADAM NASH CREATED BABEL SWARM, A NETWORKED PROJECT LINKING PEOPLE IN REAL LIFE WITH AVATARS CREATING AN IN-WORLD, REALTIME 3D SCULPTURE BUILT FROM THE SPEECH OF PARTICIPANTS. THE MEDIA RESPONSE AND PUBLIC INTEREST WAS WAY BEYOND EXPECTATION.

Although the Australia Council doesn’t have any Second Life property, it has ‘borrowed’ space from the likes of the ABC and the Australian Film Television and Radio School, allowing it to conduct an in-world media campaign, in-world client meetings, in-world artist matchmaking and the first in-world grant assessment meeting. The virtual gets real-er all the time.

What made the Inter-Arts office take up the Second Life challenge?

We’re keen to support those practices that would otherwise fall through the funding gaps between the artform Boards, and interested in what Adam Nash calls “post-convergent” art. I’m not quite convinced about the term yet but it’s about spaces opening up room for practices to flourish that are not limited to the physics of the natural universe.

Getting past conventional representation must be a challenge for artists making work in Second Life?

Yes, it’s a kind of parallel ‘real’ world for many people, and it’s cheaper: you can buy virtual Gucci shoes for five cents rather than paying a million bucks. But in terms of aesthetics, there’s a huge potential to shift things. So we thought why don’t we support the emerging practices that are already testing Second Life and other spaces. There was already a cluey and energetic art culture happening there and Australians seemed to be engaged in it from the beginning.

So Inter-Arts has played a triggering role?

That’s what we aim to do, to make potential practices visible and then other artists become more aware of it as well. So it’s about finding ways, with small amounts of funding, to support emergent practice.

Because Second Life is cheaper than real life, does this mean you don’t need to invest quite so much money?

It’s a helluva lot cheaper. But in fact it was the largest grant that artists have received for such a virtual platform. It was $20,000 for up to three Australian artists to develop a project that used the disciplines of literature or writing, sound art or music and a digital visual practitioner. The Music and Literature Boards and the Inter-Arts Office funded the project collaboratively. It was an interesting collaboration within the Australia Council itself.

Were there funding criteria beyond making the work, for example how it might be exhibited or broadcast?

One we built into the grant itself was for the applicants to create some form of mixed reality showing or event where people who weren’t necessarily conversant with these virtual platforms could experience the new spaces for themselves. It was about making people aware of the potential of the platforms and assisting those who might be technologically phobic, or just not into these spaces, to at least have access. The artists collaborated with Lismore Regional Gallery so that a regional centre had the first mixed reality showing of the Second Life initiative. Lismore farmers mixed with the directors of Eye-Beam [new media arts centre] in New York as Babel Swarm evolved in the gallery.

Virtually and actually.

Well, you know, there’s no difference. There were people in the gallery and people online from various places interacting, avatars ‘flying in’ from wherever and the people in the gallery space with access to a few generic avatars. They could access an avatar and then interact with the other avatars from Tokyo or New York. The artists cleverly developed the event in three stages. The first was like a traditional gallery approach with images, photographs and text. The second space, on screen, was machinima: a filmic version of the artwork. The third space was where people were engaged interactively in real time with Babel Swarm and with other avatars.

The people at the opening were creating Babel Swarm in the process of interacting with it. This is something very interesting about the project—it’s user-generated. The words people spoke or typed into the space were the same words that create the work’s sculpture as the letters fall from the sky in the Second Life lansdcape. It’s beautiful metaphorically as well. There are many layers and I’m sure I haven’t touched on all of them yet. After the letters fall, they start searching for each other but avatars can destroy them and once destroyed they have no chance of becoming whole again, becoming one with other letters.

A strange kind of ecosystem. You’ve described Babel Swarm as “sculptural.”

Others would call it musical because there’s a very complex sound aspect to it and the sounds are triggered by the letterforms. So, depending on people’s preference—I’m very much visually oriented—but people who have a sound or literary orientation would perhaps read it in a different way.

What might the literary people get out of it, do you think other than the joy of seeing letters?

There is a growing understanding that literature is more than poems or novels, that literature is a practice that’s living and that people interact in other interesting ways through words. There are probably writers watching their text fall and interacting in a dialogue about the ways words and letters can impact on each other.

The gallery audience loved the experience and so did the in-world audience and participants—there were more than a thousand visitors at the time.

What do you think is the future of this initiative?

It will depend on the type of artists and their interests. I think there’s probably a lot of room for performance art as well, which doesn’t necessarily require the huge technical skills which artists like Nash and Dodds need to code the letters in Babel Swarm and make sure they connect. A key thing is that this practice engenders a collaborative approach. If artists are not necessarily confident within the virtual space they can collaborate with somebody who knows more about it and maybe thinks about that space in a different way. That can be very productive. One of the processes we developed for this initiative was a matchmaker or collaborator blog where we put artists in contact with each other, not just the technically proficient. So it’s an ideal space for collaboration.

Has there been a new phase of the initiative?

Another one emerged from the Second Life initiative called MMUVE IT!, a Massive Multi-user Virtual Environment Initiative. There was a recognition that the next step would probably be an embodied computer-human interface, a little bit more complex than, say, the mouse or the keyboard. There are a lot of new interfaces being developed in areas like gaming: alpha waves or 3D motion-tracking cameras allow people to move their bodies and therefore their in-world avatars.

The successful artist team for MMUVE IT! is Trish Adams (RT84, p31) and Andrew Burrell who’ll be working with the Queensland Brain Institute to develop a project called Mellifera (http://mellifera.cc), working with sound and with bees to help people manipulate, interact with and develop ecosystems in a virtual space via their avatars and their bodies. It will explore cognitive processes and bodily interaction and their relationship to virtual environments. They’ll use Second Life and the work of an Australian start-up company called Vast Park where you can have your own virtual world and connect to other virtual worlds.

More parallel universes!

So rather than having your own island, there’ll be a galaxy of virtual worlds. What Inter-Arts wants to encourage in our next round, closing December 1, is work that can engage with mixed reality settings but also more locative media based works—mobile phones, GPS—different ways of interacting in public spaces. It doesn’t always have to be technology based but some of it will be. And we’re also interested in user-generated content, a growing area, that reduces the audience-artist dichotomy with the audience being involved in the creation of the artwork. The Second Life and MMUVE IT! initiatives are designed to generate interest and activity, but our key focus is still on the grant rounds where artists apply with great ideas for works.

How successful was the promotion of Babel Swarm?

It was extraordinary. It took us all by surprise. It was great to be on the crest of the wave. I think it’s to do with the social networking phenomena that has emerged over the last few years. People are now more comfortable with being in these virtual spaces. They’re like 3D chat rooms—3D MySpace or 3D Facebook. There are people who say these spaces are destroying social skills but these are places where you can blossom and you’re not going to be killed or become a social pariah, not for long anyway. You can always come back in another avatar and make new friends.

The media and public response to the Babel Swarm launch was extraordinary. It got the highest hit rate of any initiative that the Australia Council marketing team has developed to date. I think one of the keys to its web success was that there was international interest. It was an interesting to see the potential of social networking sites in terms of art practice. In hindsight I’ve labelled these practices Social Media Arts—a combination of Media Arts and Social Networking. It’s not just the form of the art and the new means of expression but the huge networks they’re connecting to. That’s new, I think.

What have the other artform boards of the Australia Council taken on in this area?

The Literature Board, through Stories of the Future, had some great Second Life and other digital initiatives in its promotion of digital publishing over three years. It included the mixed reality event Mix My Lit at Federation Square where V-Jays and Lit-Jays were mixing their sounds and images and texts that the public were texting them onto the screen and their little stories were being mashed. So there is no distinction between “this is what literature is” and “this is what visual art is.”

The Visual Arts Board funded dLux Media Arts to do a whole range of machinima and Second Life initiatives, including tours in Second Life. The Music Board and the Literature Board were already on board with this. The MMUVE IT! initiative was a collaboration between the VAB and the Inter-Arts Office. I think that’s one of the most successful aspects of these initiatives. You have emerging practices, collaboration across artforms, breaking down barriers and giving artists the opportunity to seek support for work they may not be able to apply for in one particular board.

Post-convergence funding. What about the issue of facilitating participation and development in regional areas?

We’re learning from artists, as we did with the Babel Swarm-Lismore Gallery collaboration, where they saw a need to develop these projects in regional Australia. We’re not developing specific initiatives here yet but we are looking at how we can facilitate it with other boards or initiatives to incorporate regional possibilities in the projects they’re developing.

The Inter-Arts Office part funded a project with urban and regional dimensions called A-lure by Visionary Images completed this year in Melbourne, Shepparton and Richmond where socially disadvantaged young people worked with media artists to develop locative media games within the City of Melbourne.

Is Council looking at the potentials of multiplatforming?

At the international Urban Screens event that’s happening in Melbourne (Oct 3-5) Council supported a focus on the re-purposing of interactive work, perhaps initially staged in a small space, so that it can be made public in a large urban context. We also assisted MEGA (Mobile Enterprise Growth Alliance) to develop some projects to teach artists how to link with business to get their content out there on the mobile phone platform—a huge market’s emerging and one of the most lucrative markets as well. We also have a major partnership with the ABC to assist in the broadcasting of work made by Australian artists.

As technological developments in media continue to accelerate and arts opportunities multiply, the Inter-Arts Office’s R&D alertness is a valuable resource for artists working on landscapes real and virtual and, not least, un-signposted.

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008 pg. 36

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

screenshot of Pool website – tag search

THE RISE OF WEBSITES LIKE YOUTUBE AND FLICKR HAS MADE THE SHARING AND REMIXING OF CONTENT MORE MAINSTREAM AND MORE CONTROVERSIAL THAN EVER. REUSE AND REINTEPRETATION AREN’T JUST FOR ABSTRUSE FRINGE-DWELLING SITUATIONISTS AND GRANT-UNWORTHY CRAFTS LIKE SCRAPBOOKING. CULTURAL APPROPRIATION IS THE CURRENCY OF A NEW, FASHIONABLE GENERATION OF VERY MAINSTREAM INTERNET USERS. IT IS ALSO THE GROUND ZERO OF A PROTRACTED DISPUTE ABOUT THE NATURE AND OWNERSHIP OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY THAT ENGAGES MEDIA ORGANISATIONS, ARTISTS, GOVERNMENTS, COLLECTION AGENCIES AND THE GENERAL PUBLIC.

Into this disputed territory steps the ABC’s pool.org.au, a project that invites and fosters reuse of digital art. In the short time since the launch, the site has been populated with a fascinating array of content spanning the full spectrum between kitsch and inspired, unfinished samples and well-produced remixes and reworkings. There are already some familiar names uploading content; at a cursory inspection Alan Lamb and Jim Denley, and from within the ABC, producers Nicole Steinke and Gretchen Miller seem positively active. It’s not the only such experiment launched of late—the textually-oriented, Australia Council-backed Remix My Lit project has been making a splash in the blogosphere. The ABC has also made tentative gestures in this direction before with small creative reuse projects, such as the Night Share and the Orpheus Remix Awards.

But while the style and form of a social media site might be familiar to internet users in 2008, the institution behind this one is not your typical Facebook or Yahoo, nor is it an entrepreneurial startup. Why this sudden adventure into potential anarchy by the ABC? Are we seeing a public broadcaster relying on volunteers to make up a shortfall in content? Or an adept and thoughtful attempt to respond to the social media zeitgeist? Is it so very different to Australia Talks Back, and is it any more interesting?

I interviewed two of the project’s instigators, Sherre Delys and John Jacobs, about the venture and its origins. What follows is excerpted from those two interviews. Starting with the question: where did the idea for the pool come from?

pool evolution

Sherre Delys: The pool has [evolved] from an idea around since before YouTube—the idea of sharing and remixing. It’s only recently that we’ve been able to make the case to the ABC that this kind of thing is worth getting involved with. It’s an experiment with the role of a public broadcaster.

John Jacobs: There’s a lot of different ideas going into the pool. It’s a petri dish, it’s got culture in, it’s growing, and we’re all sticking our finger and licking it occasionally.That culture we’re growing is going to inoculate the ABC against becoming a fossilised media organisation…It’s R&D, to see what public media might be, in a networked, social media future. Public media have historically been cultural gatekeepers, representing people back to themselves…A networked social media thing could be the public media of the future…ABC workers have certain skills—we’re employed to “do” media for the people, if you like. I think there’s a role for the people to be paid by the government to help administer and facilitate a social network space.

why the abc?

Dan Mackinlay: What does the ABC getting involved in social media offer to the users that they would not get from, say, just filesharing on YouTube, or Facebook? And how about the criticism made of YouTube—that this “user generated content” is a cheap way to get media produced by volunteers while providing little in return?

SD: There’s a lot of answers to that. For one, we’re constantly concerned about giving back to our users. We’re organising production advice and resources—some of our projects get ABC studio time for pool users. We get exposure for people’s work, and provide a trusted brand and a non-commercial context, an advertising-free context. We don’t have to behave like a YouTube and work out how to make money out of it.

If it’s what users want we have resources to assist making that transition from ‘am’ to ‘pro.’ We’re curating works on the site. We have radio producers sharing their experience. You’ll see that Street Stories has started a project up—and at least one job at the ABC has come out of it already. We have a strong moderation process, a lot of skilled time goes into it, bringing out high quality results. It’s not at all one way.

copyright: issues & options

One part of the pool that has drawn a lot of attention has been the copyright regime. The pool allows works to be submitted under a variety of Creative Commons Licences, some of which allow legal re-use of the content without royalties to the artist who created it.

DM: As it currently stands: when you submit content to the site, you choose what licence to place it under. This can be either a Creative Commons licence, or not, and there is also a voluntary dual licence to allow the ABC to rebroadcast.

SD: We see it as providing a variety of options. So if you upload a low quality version of the work you might want to licence that with a very open licence to allow it to be distributed, to raise your profile. And you might reserve a high quality version for commercial use. It’s completely up to an artist and what their goals are with a given work.

DM: As far as I can tell, in the latest iteration of the relationship between [musical royalties collection agency] APRA and Creative Commons Licences, APRA argues that their collection contract is technically incompatible with Creative Commons. But they also acknowledged at the Music Industry Forum last year that a huge number of their members are actually using Creative Commons Licences, and they conceded that they would not to sue their own members…It’s definitely a grey area. Is there awareness of that among the users?

JJ: Absolutely, it’s come up. A lot of APRA members have been concerned about that…There’s compromise needed and the players are at the table working it out, but there’s a long way to go.

It’s time to think carefully about your rights, and not just allow other people to make the decisions for you. When you see the pull down boxes and all the different types of licences, it’s time to read the fine print. We’re already seeing artists becoming their own labels, putting their stuff out there, becoming experts in all sorts of areas, production, instruments. We know lots about lots of different fields; it’s time to know about rights management.

DM: One thing pool does is make really clear which licence the uploaded work has, what you can and can’t legally do with it. I’m assuming that’s part of the intent—a safe space for reuse of material? I notice you can also see which other works a piece derives from.

JJ: [Attribution] has got to be easy. If you are a remix advocate, like myself, that’s part of your responsibility. And so, on pool we have a first baby step in that direction—that is the ‘derived from’ field, you have a menu of [works] in the database…That’s a start, but it should be so much easier. And it will be.

everyday pooling

For my part the pool project is a hard one not to like; the effervescent excitement amongst the site users is more response than I’ve seen to an ABC project before, and all this without the usual high budget trappings and drum beating that kicks off, say, a new TV show. The budget didn’t even run to a catered launch. In the absence of an offer of celebratory canapés on the public purse, I consoled myself with a trip to the MCA show in the Biennale of Sydney.

In the dying days of that festival the galleries seemed more crowded than usual, and more full of miscreants. Those most mischievous of Sydney-dwellers, the mobile phone owners, were out in force with their illicit happy snaps of the works, keeping the gallery attendants busy. I had most sympathy for the gent getting himself shooed off Tracey Moffat and Gary Hillberg’s REVOLUTION. The didactic panel explained that this video work was proudly constructed from unlicenced samples of commercial works. That did not help the attendant make her plaintive case that this gentlemen could not in turn take photographs of those stolen frames of video. It’s gallery policy, you see.

www.pool.org.au

www.abc.net.au/classic/orpheus/

http://remixmylit.com/

http://creativecommons.org.au/

www.viscopy.com

www.screen.org/

www.copyright.org.au/

www.apra.com.au/

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008 pg. 37

© Dan MacKinlay; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

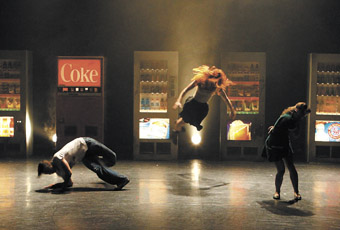

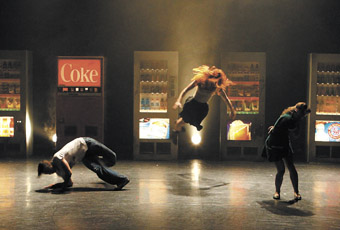

Menske, Ultima Vez

photo Martin Firket

Menske, Ultima Vez

DANCE KEEPS VIENNA BUSY FOR FIVE LONG SUMMER WEEKS, EVERY CORNER OF THE CITY DOTTED WITH GLOWING BALLOONS, ENDLESS OPEN-AIR PARTIES AND GRACIOUS BOYS AND GIRLS ON PINK IMPULSTANZ BIKES. EUROPE’S PREMIER DANCE FESTIVAL, IMPULSTANZ IS AN ARTISTS’ BUSINESS, NOT ENTERTAINMENT FOR THE TAXPAYER, ITS INDEPENDENCE VISIBLE NOT ONLY IN THE MERCIFUL ABSENCE OF POLITICIANS’ ADDRESSES, BUT, PRIMARILY, IN THE CENTRAL ROLE THAT EDUCATION, DISCUSSION AND RESEARCH HAVE IN THE PROGRAM.

Established in 1984 by Karl Regenburger and Ismael Ivo as a vehicle for development of contemporary dance in Austria, ImPulsTanz introduced its performance component in 1988, and now boasts over 200 dance workshops, an extensive scholarship program, a young critics’ forum and this year’s first Prix Jardin d’Europe for emerging choreographers.

European dance, however, is not an unequivocal affair. With walls between performance art, theatre and dance long breached, many an overseas visitor is seen stumbling baffled out of a performance: ‘Can this be called dance at all?!’ Much of the focus (despite the enormous individual differences between choreographers) is on disrupting and dismantling the relationship between the performing body and the world at large. Instead of what André Lepecki calls the “anatomical self-experimentation” of modern dance, complicit with modernity’s restless drive towards mobility, its kinetic excess, the Viennese dancer refuses to be a “dazzling dumb-mobile”, rebels through stillness and speech, ugliness and failure. In a time when the body has become the central fixation of Western politics—detained, surveilled, displaced, dutifully exposed or wrapped in shame, focus of ethnic hatred and identity anxieties—contemporary dance in Europe strikes me as unmistakably political.

ultima vez

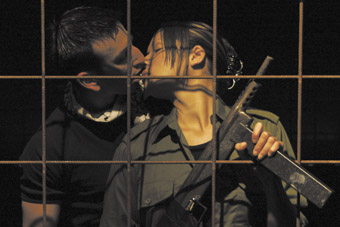

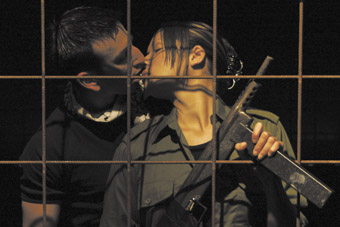

Even the standing room only tickets have sold out, and the raging mass of disappointed kids looks like they may start a riot: the atmosphere before Ultima Vez’s performance is akin to a rock concert. Choreographer superstar Wim Vandekeybus’s company has toured the world with their trademark vocabulary of acrobatic, extreme, often violent movement, soaked in multimedia and energetic music. Menske (meaning approximately ‘little human’), their latest work, has all the typical flaws and qualities of classic Vandekeybus. On the conservative end of political intervention, Menske is an explosive concoction of brash statements about the state of the world today, a sequence of rapidly revolving scenes of conflicting logic: intimist, blockbuster, desperate, hysterical. The broad impression is not so much of a sociological portrait, but of a very personal anguish being exorcised right in front of us, as if Vandekeybus is constantly switching format in search of eloquence. Visually, it is stunning, filmic: a slum society falling apart through guerrilla warfare, in which girls handily assume the role of living, moving weapons. A woman descends into madness in an oneiric hospital, led by a costumed and masked group sharpening knives in rhythmic unison. A traumatised figure wanders the city ruins dictating a lamenting letter to invisible ‘Pablo.’ Men hoist a woman on a pole her whole body flapping like a flag. “It’s too much!” intrudes a stage hand, “Too much smoke, too much noise, too much everything!” And the scene responsively changes to a quiet soliloquy. At which point, however, does pure mimesis become complicit with the physical and psychological violence it strives to condemn? Unable to find its way out of visual shock, Menske never resolves into anything more than a loud admission of powerlessness.

robyn orlin

South African Robyn Orlin’s work is political in the broadest sense: in dialogue with culture, history and identity in the post-apartheid, attentive to the politics of representation, she regularly brings the untouchable on stage and unleashes it on the audience. Her Dressed to kill…killed to dress… is neither subtle nor immediately likeable. It is, in turns, in-your-face, obnoxious, sentimental, playing for cheap laughs, gaudy; and yet enormously compelling and rather smart. We are invited to judge in a ‘swenking’ competition, a lovingly presented South African quirk: the fashion competitions of migrant workers in Johannesburg, sometimes with prizes in money, watches or even livestock. Personal style is displayed in a softly graceful sequence of movements: wrist to ankle, tie to watch, jackets flung over the shoulder. This mesmerising dance is coupled with video presentation of each swenka’s real-life world: workplace, family, the street, the city. Meanwhile, glimpses of newspaper headlines announce “Hidden Cost of Power Cuts.” Familiarising an exotic strangeness to the point of banality, then making it strange again is no small feat for an hour-long performance. Descending into mayhem of images, Dressed to kill… becomes first a confrontingly trivial dissertation on consumerism (MC Rafael Linares sighing, “Hugo Boss! Prada! Gucci!”), but then warps into a devastating picture of blind narcissism and cultural loss: the suits deconstructed into war costumes in ominous pink, music violently blaring, the ensemble breaking into the audience to hysterically demand a winner. It is neither cute nor quaint anymore.

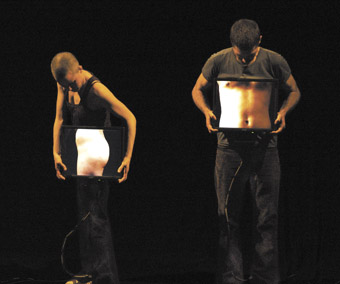

Gustavia, La Ribot & Mathilde Monnier

photo Marc Coudrais

Gustavia, La Ribot & Mathilde Monnier

mathilde monnier & la ribot

The most extraordinary performance, however, is Mathilde Monnier and La Ribot’s Gustavia, a sharp and intelligent exploration of female identity abused through physical violence, prejudice, the imperative of silence, prescribed emotions. “After these tears are shed”, Monnier announces weeping, “all feminine in me will be gone.” On a cocoon-like stage, wrapped in black cloth, intimate and chokingly oppressive, unfolds a bleakly literal, demystified burlesque in which highly sexualised women humourlessly step into pails, fall, receive slapstick blows. Monnier, repeatedly hit in the face with a gigantic plank, collapses and obediently rises again, frail and unsteady in high heels and a skin-tight leotard. In the triumphant final scene, the two performers populate the stage with a menagerie of strange and familiar creatures, employing only a torrent of words and growingly frantic gesticulation: “a woman has ears with trees inside!”; “a woman has thighs cut with a chicken here!”; “a woman has small breasts which fit inside her bra!”; “a woman sews her hymen to get married!”; “a woman in the dark.” Hysterical laughter and horror collide to great effect, and political side-taking never smothers superbly executed formal inquiry. Nothing is superfluous in Gustavia, which proves that it is possible to be topical without falling into cliché.

2008 ImPulsTanz: Menske, direction, choreography, design Wim Vandekeybus, music Daan, creation, performance, script Ultima Vez, artistic assistance, dramaturgy, Greet Van Poeck, Museums Quartier Halle E, July 21, 23; Dressed to kill… killed to dress…, choreography Robyn Orlin, performance City Theater & Dance Group, video Nadine Hutton, Akademietheater, July 11, 13; Gustavia, choreography, performance Mathilde Monnier & La Ribot, lighting design Eric Wurtz, Akademietheater, July 15-18, ImPulsTanz, Vienna, July 10-Aug 10, www.impulstanz.com

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008 pg. 38

© Jana Perkovic; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

left – Leah Shelton, Polytoxic, right – Vou Dance Company

photos Fiona Cullen

left – Leah Shelton, Polytoxic, right – Vou Dance Company

THE TOWERING SOUNDSCAPES OF BABEL INVARIABLY HAUNT EVENTS THAT ASPIRE TO A LARGE-SCALE EXCHANGE OF HUMAN IDEAS. AS AN ANTIDOTE TO ANTICIPATED COMMUNICATION MELTDOWN, 21ST CENTURY MANAGEMENT EMPLOYS TACTICS LIKE OBEISANCE TO THE FAIR PLAY OF RHETORIC TO DEFLECT CONTROVERSY AND CHAOS WHICH CAN, UNINTENTIONALLY, GENERATE PASSIVE LISTENING RATHER THAN EXCHANGE. THIS UNINTENTIONAL PARADOX IS OF THE SAME ORDER AS THAT POSED BY CULTURAL COMMENTATOR, RUSTOM BHARUCHA’S PROVOCATION: “DO THE IDEAS OF THE LIBERAL THINKER IN OUR SOCIETIES NEED TO BE QUESTIONED?”

In some respects, Bharucha’s question was a throwaway line, dropped like a pebble in the hushed auditorium of the Cremorne Theatre to prick the indignation of Babel, but it fell that night without so much as a splash. Where was the rabble-raising such a question was crafted to sting? Admittedly, it was a relief that war was staved. But what about the dialogues, conversations between opposing ideas, exchanges in diversity?

Such musings arise not in criticism of the mighty effort from Associate Professor Cheryl Stock and Janelle Christofis (Ausdance Queensland) and the extraordinary team of associates and volunteers who made the event sparkle, but to wonder why the dialogues at the heart of the World Dance Alliance Global Summit and its vision of “Conversations across cultures, artforms and practices” sometimes faltered.

The World Dance Alliance was born from Carl Woltz’s belief in the capacity of dance artists, educators and scholars to transcend difference and present a richly varied and united front to the world. Hatched in the Hong Kong Academy of Performing Arts, Woltz’s idealism spread through the Asia Pacific region, the Americas and Europe, forming a loose coalition of like-minded people who wished to promote the significance of dance in human affairs. Annual meetings, propelled by the key training organisations’ desire to share their physical achievements, gave way to greater visions of what dance on the world stage might mean. Cutting a complex history short, that is where Brisbane stepped in to host the 2008 Global Summit, proposing an institutional ‘coming-of-age’ which privileged the ‘voicing’ of artists, educators, scholars, administrators, producers and critics’ practices.

Dialogues, embodied and verbal, thus guided the event’s unfolding. From an Australian perspective, the targeting of debate was politically proactive, straining against the nation’s habitual avoidance of incisive art form commentaries. Such reticence has been attributed to the fragile state of funding, but there are also strains of the laconic Aussie temperament in the mix which signal acceptance and equality but can be misinterpreted by outsiders as a lack of interest.

At the same time, “she’ll be right mate” nonchalance, if underpinned with tight, organisational control, can strike just the right notes for a thoroughly embracing and bracing hospitality. Such was the relaxed pitch of excitement at the opening night’s party in the QPAC courtyard. Dialogues were unleashed in encounters, inevitably incomplete and side-tracked against the resonant welcome to country from artists of Treading Pathways and their Fijian counterparts. The interplay between dijeridu and drum, together with the volume of the milling crowd, intimated the vibrancy of exchange ahead.

In large conferences, delegates can be assured of finding abundant stimulation for their particular bent, even if all sessions focus on crossing, shifting and interrogating cultures in one way or another. Culture is notoriously or fortuitously indeterminable in contexts such as dance. Be it queer or techno, post-humanist or ethnic, culture incubates interpretations and consequently facilitates diversity, resulting in choice overload. If you latched onto what ‘bele’ might mean for Pan Caribbean identity, you were bound to forego insights into who frames the writing and performing of Odissi in India; the impact of managerial cultural policies of dance in the UK; methodological and theoretical issues of clinical practice research; educational strategies on culture in the classroom and a poetic invitation to “Boundaries … dreams …beyond.” More pertinent to the desired outcome of dialogue, each session seemed time-constrained which, though indicative of the smooth-running of the event, tended to disable exchange at the point of its critical engagement. Is it the nature of conferences that rhetoric outstrips the conditions possible for considered reflection? As one idea is conceived, the next topic whizzes off on alternative conceptual tangents.

Another innovation of the event aimed to raise the level of discussion by embracing eminent practitioners within the Australian environment. The Cremorne venue and celebrated guests of the afternoon Dance Dialogues certainly contributed prestige but presentation styles and the stage/auditorium separation inhibited the flow of spontaneous debate. Professor Susan Street’s Dame Peggy Van Praagh Memorial Address raised questions about the dance community’s possible failure to exploit the educational and political potential of creativity in an age poised to respond to “conceptual and emergent experiences.” Such a far-reaching issue cannot be resolved through an immediate barrage of questions and opinions but, by the same token, participation can underline the significance of these matters by infusing the political with the personal.

Undoubtedly dialogues did continue in multiple fragments through dinner engagements that generated their own momentum, however, shared moments to tackle pressing challenges did not eventuate from the dialogue series in spite of valuable probing and reflection from an impressive array of guest speakers. It seems that the interrogative practices of the dance community need sharpening.

That said, “Dialogue Five: Re-thinking the way we make dance”, the Summit’s closing exchange highlighting the Choreolab that took place in parallel to the week-long talk-fest, did ignite an odd fiery crackle. The Choreolab provided four mid-career choreographers with the opportunity to work on the all-important writing of bodies through time-space with a selected group of dancers under the mentorship of two masters, Lloyd Newson (UK) and Boi Sakti (Indonesia). Here, dialogue was reduced to monologue, initially by the decision not to show any transitory outcome of the week’s explorations which the assembly accepted with good-will, but then by an ill-informed attack on the very core of the organisation’s belief in diversity. Though protesting against intolerable persecution of a certain social group, the latter speaker’s inflexible ‘righteousness’ overstepped the boundaries of tolerance and, ironically, united delegates in multi-directional debate. Injustice, as the ensuing discussions acknowledged, comes in many morally-complex forms.

World Dance Alliance Global Summit, Brisbane, July 13-18

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008 pg. 39

© Maggi Phillips; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Underground, Dancenorth

photo Justin Nicholas

Underground, Dancenorth

LIKE MOST PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES IN AUSTRALIA, DANCENORTH WORKS HARD TO MAINTAIN ITS PLACE IN THE CONTEMPORARY DANCE ARENA, BALANCING A STRONG REGIONAL PRESENCE FROM THEIR BASE IN TOWNSVILLE, NORTH QUEENSLAND ALONG WITH AN INTERNATIONAL PROFILE. IN RECENT YEARS, THE COMPANY HAS TOURED TO GERMANY, YOKOHAMA, SINGAPORE, LONDON AS WELL AS SYDNEY, PERTH AND THROUGHOUT QUEENSLAND. TO INSPIRE DIVERSITY, THE COMPANY ALSO HAS A STRONG COMMITMENT TO COLLABORATION AND CO-PRODUCTION.

Fresh from their most recent international foray, a residency at the prestigious Vienna International Dance Festival, Dancenorth is presenting a national tour throughout October-November with a new work titled Underground, soon after another new work, Remember me, reviewed in RealTime 86 (p33).

Featuring six young performers (Alice Hinde, Charmene Yap, Hsin-Ju Chiu, Joshua Thomson, Kate Harman, Kyle Page), Underground turns a commuter precinct into “a vivid and surreal dream world where routine is transformed into spontaneous action.” Choreography is by Dancenorth’s Artistic Director Gavin Webber who joined the company following a five year stint with Meryl Tankard’s ADT, followed by three years in Brussels with Wim Vandekeybus and Ultima Vez [see page 38]. His previous works for Dancenorth include the wildly inventive Lawn and then Roadkill. Undergound also features a score designed by Luke Smiles, “turning it up with Nick Cave, Nine Inch Nails and Messer Chups.” RT

Dancenorth, Underground, tour dates: Brisbane Oct 8-11, Lismore Oct 14-15, Bathurst Oct 18, Sydney Oct 22-Nov 1, Hobart Nov 5-8, Melbourne Nov 12-15, Perth Nov 19-29

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008 pg. 39

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Axeman Lullaby, BalletLab

photo Jeff Busby

Axeman Lullaby, BalletLab

WE ENTER A DEEPLY FOGGED SPACE UPSTAIRS AT THE CHUNKY MOVE STUDIOS. A SPLINTERING THUD REVERBERATES THROUGH THE DARK, THE KIND OF VIBRATION THAT LODGES ITSELF DEEP WITHIN THE CHEST. THERE IS SOMETHING INCREDIBLY UNSETTLING ABOUT A HEAVY AXE SWUNG HARD IN THE BLACKNESS. IT’S NOT SO MUCH FEAR OF PERSONAL INJURY AS INJURY OF THE OTHER. AND THIS IS A FEAR THAT IS HEWN INTO WITH FERVOUR IN CHOREOGRAPHER PHILLIP ADAMS’ LATEST WORK.

Black shadowed sentinels stand in the green gloom of the clearing fog when we finally make out the image of the axeman. Laurence O’Toole, a real World Champion axeman is the Goliath standing at the back of the cavernous studio diligently making woodchips from a barkless hardwood trunk. A deep russet blazes clear across the stage, a reminder of the infernal fury trapped within the heart of the wood. Gumbooted and feathered women beat out a rhythm with planks and offcuts as David Chisholm’s composition works along with the grain, the metronome of the woodchop echoed by piano and violin.