Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

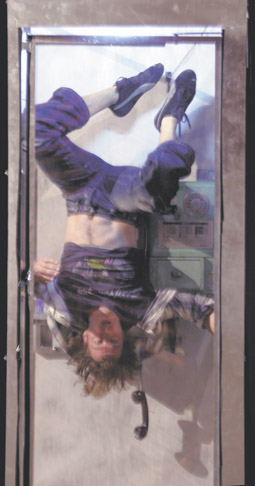

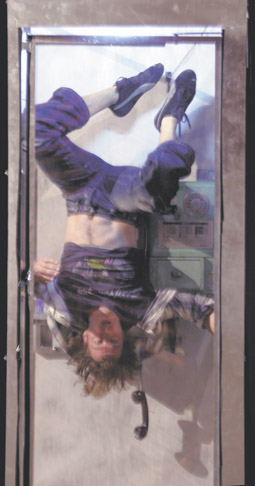

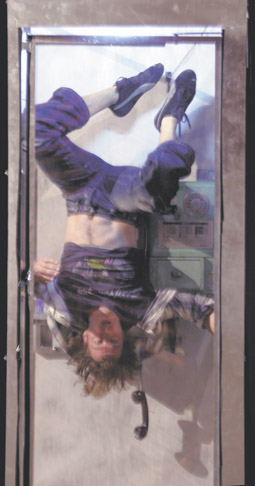

Kristy Ayre, Lifesize

photo Belinda: artsphotography.net.au

Kristy Ayre, Lifesize

LIFESIZE IS DEDICATED TO ANNA NICOLE SMITH AND DON LAFONTAINE. SO, CLEARLY, THE TITLE IS IRONIC. IF THERE IS ONE THING THAT THESE TWO NAMES STAND FOR, IT IS BEING LARGER THAN LIFE, WHETHER THROUGH DEED, IN SMITH’S CASE, OR THROUGH VOICE, IN THE CASE OF THE BARITONE SPLENDOUR OF LAFONTAINE’S MOVIE TRAILER VOICEOVERS.

Conceived by Luke George, Lifesize is a dizzying example of form as content. Taking on the vapid, electronic immediacy of popular culture, George and his collaborators have set themselves the outrageously far-reaching task of distilling more or less the entire postmodern lexicon. Naturally, the result is a multivalent pastiche of art forms, references, digressions and parodies. What remains relatively simple is the overarching narrative, an old-fashioned love story in the guise of a modern one. A man, Luke George, and a woman, Kristy Ayre, exist as individuals: they imagine themselves in a certain way; they imagine a potential lover in a certain way. These acts of imagination allow them to meet each other and to find themselves occupying a new imaginative realm transcending anything they could have imagined in isolation. It sounds complicated but this trajectory is nothing new; imagination has existed far longer than YouTube. What has changed is the degree of commodification.

Imagination is now more purchasable and externalised than ever. Imagined worlds and personas can be published and shared with no delay in gratification. In turn, this all feeds and is itself nourished by what is inadequately referred to as ‘celebrity culture’—it is, quite often, notoriety culture. The result is disposability, millisecond relevance and instantaneous feedback. So, the challenge for Lifesize is to be able to cannibalise this undeniably fascinating vein of material without itself being devoured in the process.

Lifesize begins very simply. Ayre is clad in a turquoise dress that, from a distance at least, looks like a taffeta high school dance affair. She stands demurely, facing slightly away from us; three standing lamps positioned to her side cast her in an unbalanced light. Her face is obscured, her shape seen in dramatic chiaroscuro. She begins to move a little more violently than the dress suggests is appropriate and when her face does appear her eyes are distant and disengaged. She turns on a video camera and steps in front of it. Positioned on the floor, the camera picks up her feet and legs. This live image is fed to a digital projector and shone on the full aspect of the rear wall.

The use of live cameras in performance always puts the audience in the dilemma of which to watch. In Lifesize, this dilemma forms part of the piece’s investigation of simulacra. Ayre is a perfectly watchable performer at any time, so why does the audience’s attention switch so readily to the screen? What the camera offers is, first and foremost, the opportunity to see what Ayre’s character wants us to see. Also, in a live performance, we as an audience are conscious of our physical presence and the barrier to invisible voyeurism that this puts up. When a camera is used as it is in Lifesize, our sense of seeing through the character’s eye serves to eliminate this corporeal barrier. We are removed from our chairs and placed inside the head of the character—the realm of psychology that is so important to filmmaking.

The sideways slant of the light still serves to obscure elements of Ayre’s body but in the camera’s gaze it is clear that this is part of her conceit, part of the image she is trying to manufacture, rather than any demureness. In a subsequent sequence, this coy bit of foreplay is exploded into an astonishing moment of faux amateur porn. As Barry White, slowed to a drawl, plays in the background, Ayre and George video grotesque close-ups of themselves creating lurid scenes with innocuous body parts—an elbow joint becomes a crotch with a moustachioed man eagerly licking, a hairy belly button becomes an improbably sexualised orifice that sings. To make fun of porn is nothing new, but to make porn truly funny is a very enjoyable achievement.

Lifesize gallops apace through references to dating services, Bindi Irwin, scrapbooks and tabloid magazines. At times, it skirts a fine line between professional exploration of subject matter and amateur infatuation, but this is part of the fun. To make something about pop culture, you have to know pop culture. And to know something you aspire to, as well as wish to explore, you have to like it. Luke George likes pop culture.

–

Lifesize, choreography Luke George, performers Luke George, Kristy Ayre, sound Luke Smiles, video Martyn Coutts, lighting Benjamin Cisterne, Dancehouse, March 12-13; Dance Massive, Melbourne, March 3-15

RealTime issue #90 April-May 2009

© Carl Nilsson-Polias; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Rogue

photo Jeff Busby

Rogue

A PARTICULAR PLEASURE ASSOCIATED WITH FESTIVALS IS THAT WORKS ACCUMULATE IN THE MEMORY AND AN INTERNAL DIALOGUE BEGINS. THIS CONVERSATION ALSO TAKES PLACE LITERALLY AS YOU BUMP INTO PEOPLE WHO’VE SEEN THE SAME WORKS ACROSS THE EVENT AND COMPARE RESPONSES. I’M PLEASED TO HAVE BEGUN MY DANCE MASSIVE EXPERIENCE WITH THE ‘PURE’ FORM OF RUSSELL DUMAS’ HUIT À HUIT. I FOUND MYSELF RETURNING TO IT THROUGHOUT THE FESTIVAL AS WELL AS TO DUMAS’ PROVOCATIONS ABOUT CONTEMPORARY DANCE AND HIS DISOWNING OF THE TERM IN CONNECTION WITH HIS OWN WORK.

Deeper comparisons are forming but, over the past week, I’ve taken in a vibrant display of work from the speculative explorations of Mortal Engine and the extended physicality and filmic structures of Splintergroup’s dance theatre (Roadkill, Lawn) to the expressionist brushstrokes of Melbourne Spawned a Monster, the cross-cultural mash-up of 180 Seconds, the deep meditations of Morphia Series and the playful experiment in dance translation, Untrained. The experience is completed with a glimpse of the up and coming in a night of three short works from Rogue.

Dance Massive and Malthouse have invested in this young company, comprising largely VCA dance graduates, that surfaced at Next Wave 2008. The result is a very creditable showing of three short works in the Tower at Malthouse, the company choosing notable up and comer choreographers for two of the pieces and a collaboration-with-direction from a couple of their own members for the third.

In A Volume Problem, choreographed by Byron Perry, the ubiquitous loudspeaker morphs in a profusion of configurations. Beginning with a tightly spotlit finger dance with small speakers, the seven Rogue dancers dressed in grey move through a set of highly articulated patterns interrupted by blackouts. Only occasionally do they flow in more lithe, organic groupings. Mostly they move with tight efficiency in the small space, their bodies serving with seeming ease the rhythm and shape of Perry’s idiosyncratic choreography and Luke Smiles’ insistent sound score.

Antony Hamilton’s The Counting offers the company more opportunities to display their skills in the mechanics of movement and tight teamwork to a driving sound score. The bodies of these one male and six female dancers appear light, their concentration consuming. Movements fly by, eschewing any memorable expressiveness in favour of drive and discipline and, again, the Rogue dancers deliver.

In the final work, Puck, the dancers collaborate with fellow company members (Derrick Amanatidis and Sara Black) to express what initially suggests a more playful sensibility. Colour is introduced with the suggestion of a fairground setting. The dancers appear to have lightened up, dressed in a variety of matching white costumes that display images of their faces (designer Doyle Barrow). Alas, a metronomic soundtrack sets the pace again.

The dancers move in unison through a set of prescribed movements as one of their number prowls the audience like an ice-cream seller doling out an array of sound-making gadgets—whistles, bells, quacks. At the sound of each, the movement is altered or ceased: one dancer bursts into fake tears, another breaks the pattern of movement. At the sound of the bell they return to square one.

It’s all meant to be fun and the audience accepts the invitation to play along. But equally it might also be read as a sad reflection on the prescriptive life of the dancing body put through its paces by a diabolically demanding audience. The company’s name, Rogue, suggests defiance. Maybe that’s why at the end, I wanted the dancers to break rank, step out of those trained bodies and into their real ones and engineer a devilish advance on their fun-loving audience oppressors or, though it’s a world away, slip magically into a set of those elegantly meditative Dumas duets and forget about us altogether.

–

Rogue, A Volume Problem, choreographer, costume designer Byron Perry, composer Luke Smiles, original set construction Anita Holloway; The Counting, choreographer Antony Hamilton, sound design Pansonic, costume designer Doyle Barrow; Puck choreography, performance Rogue: Derrick Amanatidis, Sara Black, Danielle Canavan, Holly Durant, Laura Levitus, Kathryn Newnham, Harriet Ritchie; Tower Theatre, CUB Malthouse, March 11-15; Dance Massive, Melbourne. March 3-15

Laura Levitus, Derrick Amanatidis, Danielle Canavan, Kathryn Newnham, Holly Durant, Sara Black

photo Jeff Busby

Laura Levitus, Derrick Amanatidis, Danielle Canavan, Kathryn Newnham, Holly Durant, Sara Black

IN A FESTIVAL DOMINATED BY CHOREOGRAPHERS, ROGUE IS THE EXCEPTION—FUNDAMENTALLY A COLLECTIVE OF DANCERS. THAT IS NOT TO DIMINISH THEM OR THEIR CHOREOGRAPHERS, FOR THAT MATTER. BUT ROGUE’S TRILOGY OF SHORT WORKS, PERFORMED AS ONE SELF-TITLED PROGRAM, IS STAMPED WITH THE UNMISTAKABLE DEMOCRACY OF AN ENSEMBLE.

Byron Perry and Antony Hamilton, who are both dancers in Lucy Guerin’s Untrained, contribute their own choreographic turns for the first and second segments respectively. Compared with the fresh-faced members of Rogue, Perry and Hamilton must qualify as senior statesmen—with the exception of Harriet Ritchie, the ensemble all graduated from the Victorian College of the Arts in 2006. The concept and choreography for the third and final section of the night’s offerings are credited to the ensemble as a whole, with Sara Black and Derrick Amanatidis stepping up to direct their colleagues.

Perry’s work, A Volume Problem, begins with a spotlit box wrapped in fake grass. Crowded around the box are the seven dancers, their hands darting across the greenery and then retreating. Fingers become legs, become bodies, become mouths. The images fold out and back in dexterously until two protagonists arrive in the form of disrobed speaker cones. Individuated from their familiar box and mesh habits, the cones are easily anthropomorphised with their central circle suggestive of a monocular perspective. Given a set of finger legs and the ever-propelling beats of Luke Smiles’ sound design, the speaker cones soon find themselves bounding about on the grass in harmonious stereo.

It is a beginning that echoes, with a touch more ornateness, the opening moments of Elbow Room’s excellent There (Melbourne Fringe 2008; p40). And, just as in There, this micro beginning bursts out of its frame when the speaker cones disappear and their character is transferred into the larger bodies of the dancers themselves; the contained box stage giving way to the stage proper. The dancers have their hair pulled back in simple ponytails and are dressed in grey shirts and black pants that give them an appearance of anonymity, androgyny and austerity—the focus is on movement, not bodies. The dance itself is steeped in the waves and beats of sound, with Smiles’ mastery of drum and bass composition a vital player.

As solos, duets and ensemble moments come and go, the figurative language of Perry’s choreography remains intact. Each body produces a beat and concentric circles of sound waves that emanate, propagate and overlap with those of others. The result is interference, both constructive and destructive, that either amplifies or mutes one’s partner. Towards the end, Ritchie and Amanatidis solo in isolation and then come together, the beat becoming that of their hearts and the very specific form of propagation that this entails.

Hamilton’s piece, The Counting, does away with Perry’s austerity from the outset. The costumes by Doyle Barrow, fluoro leggings and thin white cotton singlets, sit somewhere between Merce Cunningham and an American Apparel advertisement. The dancers, who have suddenly been given gender and sexual presence, are accompanied by an amazingly slappy bass line and undulate in unison.

Yet, despite its grinding sensuality, there is something very formalistic in Hamilton’s choreography here. He tweaks and replays movements and gestures with a modernist sense of purpose—seeking nothing more than a rediscovery of forms, of shapes and physical textures. There is no narrative or psychology to speak of, nor any of the impish fancy that characterised Blazeblue Oneline (RT85, p35) or I Like This (a collaboration with Perry, RT89, p12). Not that this is surprising per se because, as a dancer, Hamilton has always seemed particularly entranced by the quality of movement and this explorative instinct has made him one of the most formidably gifted dancers in Australia.

The final part of the night’s program is named after the prankster sprite Puck, though the arcade-like set by Anna Cordingley suggests that the title may well reference the video game Shufflepuck as well. The twin associations work well together because the piece, especially created for this Malthouse season, is all about interactivity. The rise of video games as an artform and medium of entertainment has dubiously, though nevertheless firmly, entrenched interaction as a byword for contemporary. The concept in Puck is that the audience, equipped with various noisemaking devices can, with the sounds they create, prompt certain responses in the dancers: go back to the beginning, change places, wiggle while dancing.

The effect of course is utter mayhem. The audience is put to the test in deciding how disruptive or respectful they want to be. But a fundamental paradox is set up because it is the disruption that creates the elements worth respecting. The form is inherently messy and prone to somewhat facile conclusions—in the end, all that can be affected is the pictures we see as an audience. While there are moments of exaggerated emotion, it will be interesting to see if Rogue can develop this cheerfully enjoyable concept into something that extrapolates more on the relationship between the audience and the performers, between the eyes and the bodies, between what is liked and disliked, where the stakes are almost as high as they once were in the interaction at the Colosseum. That could make for some real mischief.

–

Rogue, A Volume Problem, choreographer, costume designer Byron Perry, composer Luke Smiles, original set construction Anita Holloway; The Counting, choreographer Antony Hamilton, sound design Pansonic, costume designer Doyle Barrow; Puck choreography, performance Rogue: Derrick Amanatidis, Sara Black, Danielle Canavan, Holly Durant, Laura Levitus, Kathryn Newnham, Harriet Ritchie; Tower Theatre, CUB Malthouse, March 11-15; Dance Massive, Melbourne. March 3-15

RealTime issue #90 April-May 2009

© Carl Nilsson-Polias; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lawn. Splintergroup

photo Justin Nicholas

Lawn. Splintergroup

GERMANY AND TANZTHEATER GO TOGETHER LIKE BRAZIL AND SAMBA, LIKE SWEDEN AND WHITEGOODS, LIKE MARLON BRANDO AND FROZEN YOGHURT. SO, WHEN SPLINTERGROUP’S LAWN SETS ITSELF IN BERLIN, IT IS BUILDING ON THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL REMAINS OF EVERYONE FROM RUDOLF VON LABAN TO PINA BAUSCH AND SUSANNE LINKE.

But Lawn is not a cross-section pastiche, nor is it an entirely new layer of topsoil sitting on the sedimentary layers of its forebears. Instead, it is of that species of creation peculiar to New World artists, one which absorbs and revels in the dense history of Europe while paradoxically yearning for the perceived naivety and sunlit banality of home. Of course, this is a grand fallacy—the cultural perpetuation of Terra Nullius—but, nevertheless, the notion that a green Brisbane lawn might be appealing amidst the overcast mire of Central Europe is hardly a stretch.

Layers of European history are made immediately concrete as the audience enters the theatre for Lawn. The set is an immense and immensely clever deconstruction of a realist fourth wall box—Henrik Ibsen would feel at home if they could just get the walls straight. Indeed, the walls, with a touch of Expressionism reminiscent of Max Beckmann, are angled in such a manner that shifts in lighting can almost make them appear to move, a nightmarish illusion that presages the dance to come. Covering these are three layers of wallpaper, each one petering out before the top as though each subsequent generation had succumbed a little bit more to apathy. On the stage are three men: one eating cereal at a table, another vacuuming, the third brushing his teeth at a very European basin. With an entry point grounded so firmly in reality, the dance is almost invisible—the choreography camouflaged by familiarity and quotidian habit. And, in the context of Dance Massive, this is a markedly distant language to that of Chunky Move’s Mortal Engine or Shelley Lasica’s Vianne, for example, while Lucy Guerin Inc’s Untrained does dip its toes into this vocabulary.

As the men continue their routine, the choreography comes more clearly into view. One realises that the three share the same space but not the same time. In a beguiling sequence, their gestures become a synchronised ripple of different purposes—one man might stretch his arm upwards to put on a jumper, another does the same to remove something from a bucket. At first, each man’s path through space is carefully calibrated so as not to interfere with the others, but even then they affect each other like spectres of history—more Old World layers.

History does not stay spectral for long though. Two of the men start to mimic the third by manipulating a suit on a clothes hanger, and then move on to the man himself. Like a marionette, he is spun and dangled, hoisted and lowered, finally, into prostrate submission. The puppetry propels Lawn into a thrilling conjugation of characters, as Vincent Crowley’s clean-freak triangulates the space with streaks of gladwrap, Grayson Millwood climbs like an insect up a wall and Gavin Webber throws himself around like a marionette without a master.

Throughout, the dance remains anchored in psychology and in the imaginative leaps of the subconscious. When Millwood clambers across the walls, the simple spectacle of his virtuosity is woven into a reference to Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis with all its attendant associations to Central European living. When Crowley performs a bastardised German folk dance, complete with lederhosen and piano accordion accompaniment, it balances the claustrophobic density and dark moods around it. Only once, during a fight sequence somewhat coordinated to movie sound effects, does the form of the dance feel forced.

Towards the end of Lawn, Webber recounts a scene from the 1953 film Houdini, featuring Tony Curtis. In it, the escapologist finds himself trapped beneath the ice of a quickly moving frozen river and has to breathe the air he can find in pockets beneath the frozen crust. It is clearly an allegory for the three inhabitants of this increasingly dilapidated room. The velocity of European history, its cold ghosts and its air of inspiration all exist simultaneously. In the end, like Houdini, Lawn is a giant escape trick. Crowley slips into the darkness, Millwood disappears under a rug while Webber, all suited up, basks in the warm glow of a Brisbane front yard, happily oblivious to the darkness that engulfs him as the lights go down.

–

Splintergroup, performed and choreographed by Gavin Webber, Grayson Millwood, Vincent Crowley, dramaturg Andrew Ross, designer Zoe Atkinson, composer, performer Iain Grandage, lighting designer Mark Howett, presented by Performing Lines for Mobile States; Malthouse, March 11-14; Dance Massive, Melbourne, March 3-15

Ross Coulter and Simon Obarzanek,

Untrained, Lucy Guerin Inc

THE TITLES OF LUCY GUERIN’S RECENT WORKS HAVE BEEN MARKED BY CLARITY AND TRANSPARENCY, EVEN LITERALNESS. STRUCTURE AND SADNESS DEALT WITH THE AFTERMATH OF GRIEF CAUSED BY THE WEST GATE BRIDGE COLLAPSE. MELT WAS A DUET FOR TWO WATER MOLECULES THAT MOVE FROM ICE THROUGH TO STEAM. CORRIDOR LIMITED ITSELF TO A LONG TRAVERSE STAGE AND TOOK A CORRIDOR SCENE FROM KAFKA AS ITS INSPIRATION. AND NOW UNTRAINED JUXTAPOSES TWO ARTISTS TRAINED AS DANCERS WITH TWO ARTISTS UNTRAINED AS DANCERS.

Contrast these examples with the titular and choreographic opacity of Shelley Lasica’s Vianne and there would appear to be nothing hidden in Guerin’s world, nothing that is so mysterious that it cannot be elucidated in a simple, perfectly decipherable title. For her critics, this is a cause for frustration: her works can be seen as the physical equivalent of begging the question in rhetoric, where the proposition assumes its own truth before being argued. In other words, is the dance redundant once you read the program notes?

Yet, aside from the inherent value judgements involved in meriting metaphor over literalness, describing Guerin’s dance as redundant is to deny its capacity to transcend the admittedly literal text that tries to encapsulate it. Guerin is not given to ornateness in her language but her sensibility for the human form is far from plain—the duets across her body of work are remarkable in their mesmerising intimacy, their detail and their capacity to enliven the space between the dancers as much as they animate the bodies themselves. Moreover, by starting with such conceptual distillation, Guerin’s work emerges from a kind of purity, with every subsequent extrapolation seeming to fit and flow on perfectly from the last.

Indeed, it is a questioning of purity that lies at the heart of Untrained. The title is easily decipherable, yes, but what is it to be untrained? Is the untrained body pure in its movement—unfettered by the conditioning of choreography and exercises? Or is it the trained body, in its refinement and exactitude, that achieves purity by sublimation? Guerin is certainly not looking for an easy solution to this dialectic. She is interested in what it does to us as an audience and to the performers themselves to see these questions made manifest by exploring the continuum from pure naivety to pure technique.

Her staging of Untrained maintains this notion of purity. The set is nothing more than a grey playing square marked out by broad white lines. It is a clever delimiter, its form suggestive of a playground ball court or a boxing ring—both stages perhaps but ones not restricted to the arts. The performers never leave our sight, yet, with just one exception, only when they enter this square are they viewed. This is no geometrical sleight of hand. What we are witnessing is an experiment where we are the lab technicians and this square our Petri dish. By placing contrasting physical presences in the same space one after another, Guerin provides us with a microscope through which to examine the idiosyncrasies, the likenesses, the differentiators and the foibles of four bodies in motion.

The identities of these four bodies are important to note. Byron Perry and Antony Hamilton are two wunderkinder of the Melbourne dance scene. Not only are they ubiquitous presences in the works of Lucy Guerin Inc and Chunky Move, but they are also celebrated choreographers and visual artists. Their untrained co-performers are Simon Obarzanek and Ross Coulter, who are both visual artists. So, as it happens, all are men and all are visual artists.

To begin with, the performers present themselves to the audience one at a time by standing in the centre of the square for a few seconds, doing nothing. They have been asked to be neutral. However, each of them carries a stamp of personality and of habit, and we see this. From this starting point, Guerin uses a succession of provocations to tease out different performative languages: sing a song, be a cat that gets electrocuted, copy your partner. At times, the audience laughs at the ineptitude of the untrained. At times, they laugh at the hubris of the trained. As the work progresses, the laughs dissipate and the analytical eye is no longer restricted to the audience—the performers themselves begin to reflect on how they compare with the others and, vitally, are asked to speak to their own image.

–

Lucy Guerin Inc, Untrained, concept, direction Lucy Guerin, performers Ross Coulter, Antony Hamilton, Simon Obarzanek, Byron Perry, music Cusp by Duplo Remote, producer Michaela Coventry; Arts House, March 11-14; Dance Massive, Melbourne, March 3-15

INTERVIEWED IN REALTIME 89, ARTS HOUSE CEO STEVEN RICHARDSON COMMENTED THAT THE INAUGURAL DANCE MASSIVE WAS REGRETTABLY SHORT ON CONTEMPORARY INDIGENOUS AND INTERCULTURAL WORKS, IDENTIFYING THESE TWO AS “AREAS OF STRENGTH IN AUSTRALIAN DANCE AND DEFINITELY ON THE AGENDA” FOR PHASE TWO OF WHAT’S PLANNED AS A THREE STAGE BIENNIAL PROJECT.

Along with the intercultural collaborations featured in 180 Seconds in (Disco) Heaven or Hell, a forum hosted by Ausdance Victoria at Fitzroy Town Hall helped to correct the imbalance, throwing open the floor to a range of Australian dance artists to talk about and show examples of their work to an audience which included the international producers invited to Melbourne for Dance Massive.

context

In a contextualising session, historian and reviewer Jordan Beth Vincent gave a speedy history of dance in Australia from the 1930s emphasising the importance of Middle-European, often Jewish, influence and the rejection of it in favour of a more national ethos in the 1970s. Peggy Van Praagh ran a series of influential summer schools at the University of New England from 1967 to 1976. Vincent sees the workshops of 1974 and 76 as a critical juncture, where first time local choreographers, including Ian Spink and Graeme Murphy, were encouraged to make works for each other to perform. At the same time, more and more Australian dancers were making their own way to Europe and Asia, choosing their own influences to create brilliant hybrids.

The current scene, said Vincent, covers everything from minimalist “pure physicality to loud extroversion.” Dancers still look abroad for inspiration, but these days “collaboration is the name of the game”; all part of what Vincent terms “the democratisation of dance” where the work of individual contributing dancers is as important as the all-seeing eye of the choreographer (who often label themselves both directors and co-choreographers). Further, the very strong sense of collaboration (designers, media, sound and visual artists) can be “richer than movement.” Nevertheless, Vincent pointed out that collaboration of this order had also been important in the 30s. Likewise the phenomenon, now so marked in Melbourne, of key individual dancers contributing to work across a range of companies, could be found in the (presumably American) dance history of the 1940s.

Indigenous choreographer and administrator Marilyn Miller gave an impassioned address about the serious lack of Indigenous dance programmed in current Australian arts festivals and, further, the meagre representation of forms of dance in what is a multifarious culture. In a country where there are 200 Aboriginal language groups and their respective dance forms and stories, only one is truly represented (Bangarra Dance Company’s interpretation of Yirrkala culture). Miller contrasted this with the training of Aboriginal dancers at NAISDA which combines traditional dance with a variety of other forms—Graham, Limon, African dance and popular forms such as jazz and tap.

Speakers shimmied around the awkward topic of form and content in contemporary Australian dance (an interesting take on this issue can be found in Carl Nilsson-Polias’ review of Lucy Guerin Inc’s Untrained, pointing out just how literally Guerin titles and conceptualises but then makes complex her stated content). Theatre critic Alison Croggan admitted to a growing interest in dance, a form she approaches from her perspective as a poet. In dance she sees a refreshing renewal of interest in the audience-performer relationship, for example in works such as Simon Ellis and Shannon Bott’s Inert where an audience of two encounter one each of the two performers. The audience, Croggan said, was on the one hand deprived of its normal relationship with the performer, on the other “incredibly privileged.” In other recent works such as Lucy Guerin Inc’s Corridor and Chunky Move’s Two Faced Bastard, similar renegotiations are made possible.

David Tyndall former dancer and now director of Dancehouse talked about the independent dance scene in terms of the trend in Australia away from large ensembles. He saw the cost to dancers’ continued employment opportunities as balanced by the growth of a very strong independent dance community.

international visitors

In the following session, we were introduced to the international guests invited by the Dance Massive organisers to experience the festival and, potentially, begin negotiations for future collaborations and co-productions. The most interesting of the programs described were the most idiosyncratic.

Martin Wollesen is the Director of the University Events Office at University of California, San Diego, guiding a huge multi-presenter program in dance, music, spoken word and film, including the new ArtPower! series of interactive films and The Loft, a performance lounge and wine bar “where emerging art and pop culture collide” four to six nights a week. His international contemporary dance program partners with “dance innovators to create projects that embrace and reflect the university’s commitment to interdisciplinary investigation.” In 2009 Wollesen inaugurated the Innovator-in-Residence Project with Wayne McGregor of the UK’s Random Dance in a three-week residency “that explored choreographic cognition and creativity with UCSD cognitive science researchers.”

Audience development was a key theme for presenters from Spain and Brazil, Former dancer and choreographer Marc Olivé has worked since 2005 as a programmer at Teatre Mercat de les Flors in Barcelona, which in 2007 became The Centre for Movement Arts with an exclusive focus on dance. Here attention is given to developing works as well as providing workshops for the public to contextualise them, in a program Olivé translated as “Pedagogical Baggage.”

A radical approach to audience development, especially in areas of social disadvantage, was described by Brazil’s Nayse Lopez, a cultural journalist, dance critic and creator of the country’s first professional website for contemporary dance (www.idanca.net). She’s one of the curators for Panorama Rioarte Dance Festival in Rio de Janeiro where programming focuses on experimental and multidisciplinary work. She says she watches audiences for difficult experimental work and thinks: “Oh, well, there goes that 500!” In an increasingly wealthy Brazil, one-third of the population remains illiterate and deprived of the arts while a highly sophisticated audience attends mainstream theatres. Nayse is involved in a scheme to take progressive mainstream work to a poorer city in the country’s west, performing in old, under-used theatres, and with tickets costing one to three dollars. A number of companies are funded to commit to one week a year performing for such audiences.

Other speakers included Agnes Henry of extrapole, Paris, who emphasised the importance of creative dialogue as exemplified in IETM, the ‘informal European theatre network’, which is now reaching out to Australia. Sophiline Cheam Shapiro, artistic director and choreographer from Khmer Arts in Cambodia combines classical, “indigenous” Khmer dance with collaborating composers from Asia and America. A recent work involved a partnership with New York avant-garde composer John Zorn and his musicians.

Niels Gamm runs the Department of Dance and Physical Theatre at the Konzertdirektion Landgraf, Germany. This private company produces 80 works per season in 1800 performances, including theatre, musicals, classical dance and especially non-verbal theatre, physical theatre and dance, focusing on the receiving regional theatre market in Germany, Austria, Switzerland as well as Belgium, The Netherlands and Luxembourg. Gamm spoke highly of a very successful recent tour by Brisbane’s Circa, but worried about the lack of a reciprocal taxation agreement between Australia and Germany that could inhibit touring.

australian artists

A range of independent artists then spoke about their work, representing a fascinating slice of Australia’s vibrant contemporary dance culture. All had extensive experience both within and often outside Australia, whether in their training years or in touring works internationally. Again, we were reminded of the importance of the small-medium sector in the creation of Australia’s international cultural profile.

Sydney-based Shaun Parker combines his passion for mediaeval music (he sings counter-tenor) with a dance background that included working with Meryl Tankard, Sasha Waltz and Meredith Monk. His very detailed, European inspired works reflect these multiple perspectives. Parker showed excerpts from his very successful This Show Is About People along with intriguing work-in-progress images from a new piece entitled Happiness.

Natalie Cursio lives in Melbourne and as well as creating solo works has curated a number of collaborations within the Melbourne independent dance community. Her interest is in subverting cultural clichés and addressing the human/nature interface (including endangered species). The video images she showed of her choreography with Korean dancers were particularly striking. She’s also worked in Japan and, from meeting Asian artists through the Little Asia Dance Program, formed the Homeless Dance Group, an informal collaborative venture with artists in Japan, Korea, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Vicki Van Hout gave a vivid presentation of Indigenous dance moves and video images from her striking works. She’s an Indigenous Australia who explores her heritage by learning dances from people steeped in tradition across the country. While concerned about the wrongs perpetrated on Aboriginal people, she said of her work that she’s “not so interested in sadness; we’re already sad.” What she wants to know is how Aboriginal culture infiltrates the rest of Australia.

Brisbane’s Polytoxic arrived “marinaded in carnie” from a 3am bump out at the Adelaide Fringe. Two of the company are Samoan-born (Fez Fa’anana, Lisa Fa’alafi) but grew up in Ipswich; one is white Australian (Leah Shelton). As well as Samoan culture and Shelton’s “Suzuki crazy world”, Polytoxic calls on Australian Indigenous culture (which, they say, influenced them considerably when looking for ways to perform beyond South Pacific cabaret culture) and hip-hop to “widen the language of social change and commentary around ideas of interrogating identity and cultural stereotyping.”

After performing extensively in Europe Gabrielle Nankivell has returned to Australia where her rural upbringing had instilled, she said, a sense of space and of living in the presence of animals: “a sense of physical power and instinct.” She characterised her training, including the VCA, as the accumulation of a mix of experiences. Consequently, she enjoys working collectively and showed us an excerpt from a work created in Europe with two male dancers performed on a stage with a striking graphic backdrop, a red thread stretching at an angle across the stage. Nankivell has a show coming up at Dancehouse in July this year to do with struggle and survival.

Phillip Adams’ BalletLab is currently enjoying considerable success, working in New York and soon touring to Copenhagen and Oslo. Melbourne born, Adams grew up in Papua New Guinea, was VCA trained and “danced with everyone” in New York. He described the essences of his vision as “curiosity, intrigue, queer… an onslaught of ideas which an audience experiences for a short time.” He said he creates baroque dance works, and is increasingly interested in the visual arts and the architectural language he can find within it, while testing his dancers’ endurance. He showed excerpts from Brindabella and Axeman Lullaby and described a new, pared back work about trance in US religious cults, Miracle, due to premiere mid-2009. Surrounded by 40 loudspeakers, the audience sit in a circle in which the dancers perform.

The rich conversation about Australian dance in an international context continued over and well after a sun-drenched, outdoor lunch. This Ausdance contribution to Dance Massive offered not simply market opportunities but the more important creative dialogues that might, in the long term, offer inspiration, collaboration and co-production.

–

Ausdance Victoria, International Dance Massive delegation day, Fitzroy Town Hall, March 9; Dance Massive, Melbourne, March 3-15

Ross Coulter, Simon Obarzanek, Antony Hamilton, Byron Perry, Untrained, Lucy Guerin Inc, photo Belinda: artsphotography.net.au

photo Belinda: artsphotography.net.au

Ross Coulter, Simon Obarzanek, Antony Hamilton, Byron Perry, Untrained, Lucy Guerin Inc, photo Belinda: artsphotography.net.au

THERE ARE PERFORMANCE WORKS THAT PLAY WITH AND DISORIENT THE SENSES—IN DANCE MASSIVE, SIMON ELLIS AND SHANNON BOTT’S INERT, THE HELEN HERBERTSON-BEN COBHAM MORPHIA SERIES AND CHUNKY MOVE’S MORTAL ENGINE; IN RECENT THEATRE, BARRIE KOSKY’S TREATMENT OF POE’S THE TELLTALE HEART. AT THE SAME TIME, GAME AND TASK-BASED WORKS FOR PERFORMERS AND AUDIENCES ARE ON THE RISE IN LIVE ART EVENTS AROUND THE WORLD, AND IN PROVOCATIONS SUCH AS PANTHER’S EXERCISES IN HAPPINESS AT THE 2008 MELBOURNE INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL.

These phenomena resonate, on the one hand, with the immersive media arts and virtual realities of the 21st century and, on the other, with computer game playing and the ongoing surge of popular competition, from quiz shows to reality TV. With none of the latter’s dumbed down Darwinism, Lucy Guerin Inc’s Untrained benignly offers us reality dance—an extended set of tasks that pit two trained dance artists (Byron Perry, Antony Hamilton) against two visual artists (Simon Obarzanek, Ross Coulter)—revealing much about how we perceive the human body and what we think we know about dance.

The ‘reality’ of Untrained, however well constructed the overall work might be, is that the non-dancers’ lack of dance skills provides a considerable likelihood of risk and of chance happenings, moments of surprising verve and sheer failure. Nor are the tasks simple for the trained dancers: there’s a large quotient of improvisation and passages where they have to closely mimic the unpredictable moves of the untrained or interpret their choreographies. As much as these amuse, they’re also telling. The untrained pick up the broad patterns of movement, but rarely the detail (hinged on acute degrees of propulsion, balance and articulation), while the trained briskly realise additional layers of possibility.

So, instead of a finished dance work, we are witness to a series of revealing portraits and tests with a chancy, cumulative impact. Above all, we are implicitly asked to look very closely at, and listen to, these four men, our role as observers considerably heightened. This is accentuated by the spare staging—a large open space with a square marked out in the middle, a frame in which everything happens as soon as the men enter it from the queues they form either side. Initially, each man stands before us, motionless. We take each in. We’ll subsequently see these same faces, these same bodies again, at rest (as if asleep), pulling faces, making weird sounds, reading aloud comments they’ve made about themselves. Towards the end, each of them simply stands before us again, but now we know more about them—not a lot (this is not the confessional faction of reality TV), but details of physiognomy and assessments of mobility, risk-taking, engagement with each other and us. We have guessed at and largely learnt this not from the brief images of the men alone, but from their work together.

There’s even a moment where, with cards and textas, the men stand at the four corners of the frame and sketch each other’s faces, then show the results to the audience. In another, they display photographs of themselves, and elsewhere, videos they’ve directed. They even comment on each other’s dance and visual art capacities. But it’s the dancing itself which is most revealing. One after another the performers execute a move; as the image mutates the effect is of a visual Chinese whisper. More brief moves—balances, kicks, spins, painfully slow motion extensions—ensue and morph. Ross Coulter wittily removes his shoe and uses it puppet-like to mimic a slow motion fall while his body remains at rest. The tasks grow more demanding, if leavened with moments of yawning or sighing, or long jumps, or solo songs or speaking backwards, or performing favourite pop culture figures. The extended copying duets break the frame as each trained performer follows an untrained one around the space and then the roles are reversed—concentration, effort, surprise and amusement are palpable.

These competitive duets tell us much. Obarzanek tries very hard, he’s a bit of a performer (naturally inclined to dance when he sings in his emphatic baritone); Coulter is economical, more low key, laconic, if nonetheless committed. With the trained dancers the differences are subtler; theirs is an easy-going naturalism, the singing more polished, personalities less overtly expressed. Not surprisingly it’s their dancing which is telling: Perry’s spring-loaded, quietly dramatic articulacy, Hamilton’s sinuous, rippling intensity.

As well as the duets, there’s recurrent group work which comes affectingly into its own at the end—where you find yourself wishing that there’d been more of it, as big a demand as that might be. In the course of the show, the group moans, cries and, among other things, demonstrates various, revealing techniques for removing and putting on t-shirts. Above all the men collectively convey an undemonstrative competitiveness, mutual empathy and good humour as they perform their long list of tasks, while the audience doubtlessly reflects on what its own dance abilities might be in the same circumstances.

Perhaps, too, the audience think about the pleasure of witnessing a benign image of men collaborating and competing without corporate, militaristic or sporting straitjacketings. However well or not they can dance, these men flow, as Klaus Theweleit put it in his anti-fascist classic Male Fantasies (1977), and the sense of them as real and complex, beyond artifice, is rooted in the lucid pragmatism of Guerin’s task-based formulation for Untrained.

–

Lucy Guerin Inc, Untrained, concept, direction Lucy Guerin, performers Ross Coulter, Antony Hamilton, Simon Obarzanek, Byron Perry, music Cusp by Duplo Remote, producer Michaela Coventry; Arts House, March 11-14; Dance Massive, Melbourne, March 3-15

RealTime issue #90 April-May 2009

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Deanne Butterworth, Vianne

photo Rohan Young

Deanne Butterworth, Vianne

FLIGHTS OF FANCY ARE HARD TO AVOID WHILE WATCHING VIANNE, SHELLEY LASICA’S OBSTINATELY HERMETIC WORK. ABSTRACTION OFTEN DEFIES INTERPRETATION, BUT VIANNE IS A SMILING, PURPOSEFULLY MUTE ENIGMA, A PERFORMANCE OF CHOREOGRAPHIC AND SEMANTIC COMPLEXITY THAT IS VISIBLE, BUT OFFERED WITHOUT A KEY, AN EXPLANATION. WHY IS ONE OF THE DANCERS WEARING PEACH? WHO IS VIANNE? WHERE, IF ANYWHERE, IS VIANNE? ARE WE WATCHING A MEDITATION ON RELATIONSHIPS, OR ON MATHEMATICS? AND WHAT CAN CRITICISM SAY ON A DANCE SO IMPENETRABLE TO ANALYSIS?

This figureless flux, looking incidental but clearly structured to a T, reveals an interest in chaos quaintly parallel with the 1950s discovery of quantum physics. The need to test the depth of macro order in apparent micro-level chaos resulted in chance choreographies by Merce Cunningham and Judson Church, with their shuffling and remixing, confusing the mind trying to make meaning. Vianne produces similar frustration with its density of signs and paucity of explanation.

Phillipa Rothfield observes the necessity to introduce frames, spatial or temporal, integral or external to the piece, in order to make sense of Vianne [RealTime 89]. With the elements recombining at a frequency that does not allow us to take in the whole stage action, focus must narrow, and two people making sense out of this knot of emotion and indifference, symmetry and disorder, will make very different overall conclusions.

Five excellent dancers (Deanne Butterworth, Bonnie Paskas, a slightly pregnant Jo Lloyd, Timothy Harvey, and Lee Serle fresh from Chunky Move’s Mortal Engine) group and regroup against the sound of crowd buzzing through resounding, transitional space (the sound of an airport) turning into flat, synthetic beats. The interaction between the dancers unfolds and contracts: Butterworth, a peachy stand-out among the black costumes, engages in an intimate duet, albeit tinted with hostility, with Paskas, who will then fluidly cut herself out and into a duet with Harvey. The movement ranges from physically broad (often vaguely aggressive or loving, but never even remotely figurative) to filigree. The closest Vianne gets to figuration is in choreographic moments that strongly mimic quotidian, mundane movement: stretching, walking, idleness, attentive observation. Lloyd and Paskas seem to engage in a tactile routine of mutual encouragement (head gripped, fists clenched, eye contact sustained); the same sequence has, by the end, migrated onto a different couple, this time Lloyd and Serle.

Choreographic loops are closely reiterated, abandoned and returned to: Lloyd will approach Serle in an invitation to physical combat over and over again, each time ending up prostrate on the floor, his foot slowly migrating up her thigh in a cryptic moment of aggression and seduction. She will then try to teach him a formal salute (he learns to her satisfaction, each reiteration shorter and more fluid). Some trios look like an illustration of family dynamics: broody Harvey, suspicious Paskas, overzealous, jogging soccer-mum Butterworth.

The breadth and density of the choreography is astonishing: audience members must choose their focus, as different duets and solos unfold in the same space. Movement will often stretch and jump, dancers tearing off groups to join into another, sequences mirrored across what sometimes looks like dancefloor chaos. The build-up of speed and hostility slowly dissolve in the last third, the airport noise returns, the conflicted duets turn inside out into repeats of the early signs of affection: hugging, encouragement.

Without interpretive coordinates, everything is potentially significant: the soundtrack, veering from electronic white noise to electric organ harmonics; the red-lit back wall; the silicon cube Serle and Harvey rig up in the centre of the stage and which the dancers dance through, then women dismantle with focus but utter inscrutability.

Both in its first run, and now at the Dancehouse, Vianne happens (for ‘happens’ is the right word) in a room bathed in natural light; and both times it is scheduled during crepuscule, when the crisp post-sunset light fades into night. A spotlight affixed to the external wall at Fortyfivedownstairs, mimicking streetlights, has been replaced with one in the corner of the Dancehouse studio, suddenly illuminating the darkening room with a loud flick of the switch.

There is a lot of watching in Vianne, a lot of eye contact. No intimate moment from one dancer is ever disconnected from the others, not even when they are still: a duet between Paskas and Harvey at the back of the stage is observed carefully both by us and an entire row of dancers, covering our view. The observer’s eye touches the observed and intrudes, changes the image. Like bored airport-dwellers, each dancer takes their turn to sit or stand by the wall, silently observing others dance. Sometimes they breathe heavily, exhausted. Sometimes they merely look, with the vaguest spark of personal interest.

The overall effect is uncannily like observing the street, a train station or an airport, possibly in a foreign country. After a while, one starts noticing rhythms and patterns in the large, uncoordinated mass of movement. The decipherable figure moves in and out of the interpretive grid. One makes up relationships, coordinates love and hate, invents purpose and assigns labels. When at a loss to explain the behaviour of these ‘foreigners’, one interprets with what one has: the street light, the train schedule, the music on the radio.

Of all the performance Australia has seen lately, it is paradoxically Nature Theater of Oklahoma’s No Dice (seen at this year’s Sydney Festival) that comes closest to Vianne. No Dice maniacally accumulates the minutiae of everyday conversation, driven by the same need to recreate the vast rhythms of cosmic murmur in the black box; but NTO’s project was leavened by a pop sensibility, and expansive humour. Without a semantic aim, the main goal of Vianne’s stern choreography remains to inscribe open movement in theatrical space, to extend the stage beneath the dancing feet to the uninterpretable chaos of the city.

–

Vianne, choreography Shelley Lasica, performers: Deanne Butterworth, Jo Lloyd, Timothy Harvey, Lee Serle, Bonnie Paskas, music: PEACE OUT! (Milo Kossowski, Morgan McWaters, from Melbourne band The Emergency), set Anne-Marie May, costumes Shelley Lasica, Kara Baker for Project, lighting Ben Cobham; Dancehouse, March 10–11; Dance Massive, March 3–15

Helen Herbertson, Morphia Series

photo Rachelle Roberts

Helen Herbertson, Morphia Series

OVERHEARD AUDIENCE MEMBER AT DANCE MASSIVE EVENT: “I DON’T KNOW ABOUT DANCE; I’M SAFER IF THERE’S A TEXT. OTHERWISE I FIND MYSELF INVENTING NARRATIVES. I WATCH A DANCER MOVING AND I THINK ‘WATCHFULNESS’, THAT’S WHAT IT’S ALL ABOUT. BUT I KNOW IT’S NOT THAT AT ALL!”

In Morphia Series, Helen Herbertson and Ben Cobham offer text as well as everything else but audience members searching for meaning might find themselves in the same cul de sac.

I experienced an earlier work in this series a decade ago at Performance Space in Sydney. In that version (which is with me still), the audience was separated from the performer in her yellow stage box by Ben Cobham hovering over a slide projector, placed between us. In this new version, the technology has progressed considerably, such that no lighting source is visible and we, the audience, are totally in the artists’ hands. I won’t give the game away by revealing how this works—surprise is part of its magic. Suffice to say that the relationship between performer and audience here is crucial and echoes the matter of the work (rather than the meaning) stated in the program as “working with the notion that life hovers somewhere between the ordinary and the metaphysical.”

Of the dancer’s movements I remember only fragments. They are pedestrian but equally, earth shattering. There’s geometry but no patterns, no obvious displays of skill or prowess—if you don’t count navigating the unconscious. There’s a feeling that something crucial is on the tip of the tongue. What pervades is the atmosphere, the sense of being elsewhere. When you leave the room after the 18-minute performance, it feels like crossing a border into another country. A friend greeting me as I emerged reported on a kind of collective double take amongst departing audience members. As they left, he said, they each took three steps through the door, dipped their heads, looked up, blinked and then moved off.

In the first sequence, we see Herbertson at a distance and hear her recorded voice uttering a poetic text to do with a dream of Estonia (was it?). A fine white mist appears in the yellow box. Movements from the silhouetted dancer are at first deliberate as if being slowly recovered or performed without full consciousness. At one of many illusory moments an arm becomes a serpent. Stabbing gestures mirror explosive, whipping sounds.

Next comes a dream of place, faintly familiar to me, featuring my own fantasy of the perfect living space in which human and nature are separated only by glass and inside there’s nothing to bump into. The black clad silhouette moves with the same minimal gestures feeling her way as she imagines the space into being.

In the third sequence, the text is of a vision, a body leaving its marks on nature. Were there hooves? Whatever is being said is over-ridden by the strange power of the dancer’s gaze. I remember no movement save turning, and Herbertson’s now entirely vulnerable features facing us squarely while she remained elsewhere, as if clothed in memory.

Just as shadows from the earlier incarnation of this work have stayed with me for a decade, this new work takes its place in my own unconscious. Searching for comparisons, what surfaces the morning after Morphia is the sharp memory of an hour in the Rothko Room at the Tate in London in 1997, gazing into the deep colours of the huge canvases, overtaken by an enveloping sensory reverie.

–

Helen Herbertson and Ben Cobham, Morphia Series, design concept Ben Cobham, Helen Herbertson, performance, text, sound concept Helen Herbertson, lighting Ben Cobham, sound compile David Franzke, morsels John Salisbury; Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall; March 10-15; Dance Massive, Melbourne, March 3-15

RealTime issue #90 April-May 2009

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Fondue Set, 180 Seconds in Disco Heaven or in Hell

photo Belinda Strodder

Fondue Set, 180 Seconds in Disco Heaven or in Hell

TICKETS WERE A MERE $10 AND THE SIX KEY PERFORMANCES WERE THREE MINUTES EACH, BUT NOBODY IN THE AUDIENCE FOR DANCE MASSIVE’S GENEROUS 180 SECONDS IN (DISCO) HEAVEN OR HELL COULD SAY THEY WERE SHORT-CHANGED.

The Fondue Set (Emma Saunders, Jane McKernan, Elizabeth Ryan) hosted with their trademark mix of wit, panache and gauche physicality, later leading their committed volunteer hoofers in the group dance they’d designed for the public at this year’s Sydney Festival. The sense of fun collaboration was typical of the night.

Six dance groups had been selected to work with six choreographers. The pairings had then been allowed a mere three hours to create a 180 second work to be performed on a large, raised stage amidst the requisite mirror ball sparkle and wafts of smoke.

Four of the creations provided the audience with fascinating ‘before and after’ perspectives. In a short prelude, the Natyalayaa Dance Company (Ushanthini Sripathmanathan, Asvini Rajasekaram, Hasini Wickramasekara) impressed with a demonstration of their classical credentials exemplified in supple and always surprising articulations of neck, shoulders and wrists and a fluid synchronicity of overall movement. This was followed by their collaboration with choreographer Byron Perry in which a host of classic disco moves were executed with the same verve and wicked smiles. The three bodies clustered as one and flowered into individual displays, and without suggesting Bollywood; this was something more distinctive.

Kita Performing Arts (represented by Sabrina Chou and Ruby Kao) demonstrated their classical skills with fans and twirling sticks before revealing their collaboration with Alisdair Macindoe. Here the focus shifted away from the skill-set to a more open expressiveness of the dancers’ bodies, propelling them dynamically around the stage and again revealing a sense of abandon. Like the Natyalayaa-Perry collaboration any sense of parody was kept in check by the dexterity and commitment of the two performers.

The Wickidforce Breakers entertained the crowd with quick serves of their hip-hop and break dancing skills before revealing, under the direction of Matt Cornell, a capacity to sustain moves and poses beyond fleeting moments of virtuosity. The piece was a reminder of just how much the forms have been explicitly and implicitly absorbed into contemporary dance.

Mel Rogers, Pure Welsh, Rishi Fox, Underbelly Dance

photo Belinda Strodder

Mel Rogers, Pure Welsh, Rishi Fox, Underbelly Dance

A popular highlight was choreographer Bec Reid’s tight-knit collaboration with Underbelly Dance (Mel Rogers, Prue Welsh, Rishi Fox). Underbelly first titillated us with some dextrous belly moves of the Middle-Eastern variety before disco-ing the formula, thoroughly integrating their quivering tummy balletics with showgirl verve.

Other groups simply offered their finished works. Panther (Madeleine Hodge, Sarah Rodigari) got down and drolly conceptual with a group of performers (Rob McCredie, Harriet Ritchie, Melissa Jones, Daniel Newell) who ogled the audience, wrote on cards with textas and offered the audience the inscribed words from disco song lyrics. VCA undergraduates collaborated with a couple of ornate armchairs on the creation of a circular, perpetual motion of bodies and furniture, odd couplings and erect posturings; shades of voguing. Finally, Kate Hunter added a dash of polished spectacle inspired, she says, “by Esther Williams, sharpie dancing and the Jazz Hand”, and choreographed to Amii Stewart’s Knock on Wood.

Between sets DJ Kelly Ryall and VJ Matthew Gingold kept the festive mood on the innovative boil and, after the performances, the impressively big-bandish Bamboos got the crowd dancing. Coming midway in the Dance Massive program, 180 Seconds provided just the right opportunity for audiences, choreographers, dancers and international presenter and producer guests to relax and take in some very different kinds of Australian dancing. The capacious and characterful Meat Market was ideal for the personal and collective narcissism of disco, while the event’s programming, with its artistry and lightly ironic distancing, made it much more a heaven than a hell.

–

180 Seconds in Disco Heaven or in Hell, Meat Market, March 9; Dance Massive, Melbourne, March 3-15

BEFORE A NIGHT-TIME CITYSCAPE, A LONE MAN GESTICULATES ODDLY, POSSIBLY FROM A LEDGE HIGH ABOVE THE STREETS, MOMENTARILY PEERING DOWN AT US FROM THE VERY FRONT OF THE STAGE, AS IF DIMLY REGISTERING WITNESSES TO HIS OBSESSIVE DANCE. HE IS A MAN PROFOUNDLY POSSESSED, MAKING NEAT AND LATER TORTUOUS GEOMETRIES FROM HIS BODY BEFORE HE ABJECTLY AND CONVULSIVELY COLLAPSES, ONLY TO REVIVE AND RE-FORM THEN SINK ONCE AGAIN, AS THE CITY LIGHTS FADE.

The non-literal arc of this decidedly strange passing is preceded by the sound of tennis balls bouncing off the wall in the dark followed by a brief glimpse of the man at play. In the dark, and against a mini rendering of a skyline, he suggests a hometown King Kong bouncing balls off buildings. But then, it’s as if he’s stopped, turned around and seen the city, been taken with it (or some other compulsion) and now measures himself against it. Facing us straight on, feet placed well apart, a knee bent, a hand at hip, he sways, calmly, contentedly in synch with the tolling bell, fast click and increasingly ominous thump of the sound score. He raises an arm over his head, the sway turns to swing. Thin strands of coloured lights glow or, alternatively, dim as he passes. Perhaps he believes this magic is his. Sustaining his strange composure and the gait that edges him back and forth across the front of the stage, but now gazing up, he raises his arms grandly as if to embrace or emulate the height of a skyscraper or the vastness of the sky.

Soon, other emotions flicker as arms briefly scissor across an expressionless face, as legs kick out with involuntary force, as the strange swaying strut accelerates upstage, as hands clutch from front and back beneath the crotch, and an angry, frustrated body decends to the floor, lurching with the last of its life force. Collapse is followed by gradual revival and recovery of the monster’s odd, stiff dance, if lacking its initial energy. Some kind of psychological implosion appears to have done its physical damage and the creature winds down, a bright light elegaically playing across the declining body like a lighthouse beam or indifferent car headlights pulsing through the city.

Melbourne Spawned a Monster is a decidedly strange if not althogether satisfactory work, with the kind of vaguely suggestive narrative you have when you’re not getting the one the title promises. Does Melbourne, “epicentre of Australian dance” (as proclaimed during Dance Massive), in fact spawn monsters of impossible ambition and inevitable defeat? Originally performed by the choreographer, Jo Lloyd, here the work is effectively realised by Luke George, his downstage, mechanical two-dimensional cut-out becoming an upstage three dimensional image of anguished malfunction.

Roadkill, Splintergroup

photo Belinda: artsphotography.net.au

Roadkill, Splintergroup

TANZTHEATER IN AUSTRALIA—SAVE FOR MERYL TANKARD AND SHAUN PARKER—IS THE DOMAIN OF SPLINTERGROUP AND PRODUCER DANCENORTH. THEIR VISIT IS A RARE TREAT FOR THE EUROPE-FRIENDLY PALATE.

Theirs is a dance grounded in the world as we know it: it transpires with sex, with physical violence, club music, everyday clothes and places, everyday emotions, everyday torpor. It is a dance resolutely post the abstract, monochrome modernism of Russell Dumas’ Dance Exchange, and with no patience for either the intimist slowness of Michaela Pegum, or the anti-spectacular navel-gazing of The Fondue Set.

From Sweeney Todd to the Grand Guignol, horror in theatre has a long and respectable, if forgotten, history. The stage, balancing its semiotic inevitability of real, material signs (chairs, lights, bodies) with a necessarily abstracted construction of situations, is a strong place from which to wildly associate gestures and events with submerged fears. As Hans-Thies Lehmann puts it, the signifying nature of theatre points to the constitution of meaning in general.

Dance Massive, coincidentally yet appropriately, is teeming with monsters. We have the slick, almost romantic spectacle of haywire eugenics in Mortal Engine. On the other end of the theatrical scale, Jo Lloyd’s one-man short, Melbourne Spawned a Monster, is a delicious attempt at a Penny Dreadful in 2009, and achieves sublime, almost tragically alienated banality. Originally danced by Lloyd, the choreography sits uneasily on Luke George’s body, hips swinging and shoulders circling into a feminine figure only to grow into the Hulk-like, psychotic body of a monster. The intimate relationship with abstraction that contemporary dance has cultivated allows for the full effect of these figurative disharmonies to be experienced.

Roadkill, our third horror-show so far, instead opts for the cinematic road. It possesses both the manic rhythm of a music clip and the tactile, solid mise-en-scène of film, grounded with some very heavy props: a phone booth and a car. Twisting mundane reality into pop-cultural hallucinations, Roadkill wouldn’t look out of place in David Lynch’s oeuvre. It edits and furiously remixes cinema language recreated on stage: bodies twist in slow-motion, car crashes rewind, sounds cross-fade; even panning and zooming out into a panoramic shot are achieved, the latter with some clever use of miniatures. The result is hyperreal: an impossible, yet undeniable, assemblage of scenarios.

Opening with a couple stranded in the outback, waking up in their broken-down car to birdsong and increasing paranoia, Roadkill rummages through every commonplace fear we are taught to cultivate, from rapist strangers to hitch-hiker murderers. Yet each progressively more surreal scenario hiccups back to the initial moment: after each fantasy catastrophe the couple wakes up again.

Roadkill was developed with the assistance of Sasha Waltz and Guests (p10), while Gavin Webber’s company has cultivated a style imported almost verbatim from his training with Ultima Vez, and the two influences clash without merging. The aggressive, 1990s MTV cool of Ultima Vez sits in the uneasy company of hysteric banality reminiscent of Waltz’s early works. Consequently, Roadkill attempts two conflicting types of dramaturgical progression. On the one hand, there’s the realist descent into hard-edged, psychological horror, as movement slows down into gripping narrative sequences eschewing dance, gesture or certainty for suspicion, double-edged hints, and short circuits of frightened imagination—theatre outweighs Tanz.

When Grayson Millwood, the stranger danger, appears out of nowhere, Sarah-Jayne Howard locks herself in the car, brimming with unspoken fears. Millwood and Webber’s conversation mutes, the microphone amplifies the sound of Howard’s car-bound breathing. Avoiding psychological profiling, Roadkill utilises the full range of horror devices at its disposal: from thundering, seat-vibrating beats; unreliable sources of light (at times reduced to a torch flickering towards the audience); repetition of uncertain scenarios with variation and other intrusions in linear time; Luke Smiles’ impressionist soundscape; overheard fragmented conversations; to moments when the only certainty is the enormous fear of the characters, mirrored, medusa-like, back on the audience.

On the other hand, Roadkill slides laterally into surrealist comedy of absurd, brainstorming exaggerations: the first stranded morning escalates into an anatomically improbable backseat romp; a car chase is illustrated with Webber and Howard running past with trees, road signs and dead animals. An argument between the couple is interrupted by a rain of pebbles. When gravity changes direction, Webber prevents Howard’s dead body from flying away with a pile of stones, while Millwood hovers upside down in a phone booth. Moments later, he appears, hanged by the phone chord, in a strange descent back into horror.

As Mortal Engine’s abject images demonstrate, terror resides in the least defined, least certain. Filmic attention to detail works against desired effect in Roadkill, and the production labours very hard to make strange without resorting to abstraction. To suspend reality, every hyper-real moment needs to be contradicted by another; every movement forward by an inexact rewind. The strongest moments of the performance are precisely in the pauses, uncertain junctions of dramaturgical sway, U-turns of stage action: Webber driving a toy car over Howard’s prostrated body, or a long, ambiguous duet between the two men, their mirrored motion broken by outbursts of aggressive collision. Which one is the other’s fantasy becomes unclear, as they spin against each other’s neck, shoulder or waist in Vandekeybus-like, energetic contact work. Having spun in rewind over the car bonnet, Webber and Howard comfort each other in dreamlike, decelerated grief. Which one, if either, is dead, we are left to wonder.

Without anchoring wildly imaginative hysteric outbursts in myth or psychology, Roadkill struggles to find its emotional gravitas. The result is a highly palatable comedic horror, an upbeat and furious montage of improbabilities.

–

Splintergroup, Roadkill, choreographed and performed by Gavin Webber, Grayson Millwood, Sarah-Jayne Howard, composition, sound design Luke Smiles/motion laboratories, dramaturg Andrew Ross, lighting designer Mark Howett, Bluebottle, producers Brisbane Powerhouse, Dancenorth, toured by Performing Lines for Mobile States; Arts House, Meat Market; March 5-8; Dance Massive, March 3-15

RealTime issue #90 April-May 2009

© Jana Perkovic; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lee Serle, Mortal Engine

photo Andrew Curtis

Lee Serle, Mortal Engine

THERE’S A MOMENT TOWARDS THE END OF MORTAL ENGINE WHEN A MALE DANCER REACHES OUT TO THE ENORMOUS ‘WALLS’ CREATED BY ROBIN FOX’S LASER PROJECTION AND APPEARS TO BE HOLDING THEM APART. IT INDUCES AN EXCITED ‘WOW!’ IN THE AUDIENCE AROUND US.

Throughout the 40 minutes preceding this moment, we have watched much more astonishing feats of technological interaction created in the fruitful collaboration between Gideon Obarzanek and his dancers with Fox and German new media artist, Frieder Weiss. Just when you think you’ve seen all it can do, it surprises once more. But the engagement of the audience in those first 40 minutes appears more passively appreciative.

In Mortal Engine, the Chunky Move dancers move at full stretch. In fact, I’d be surprised if at the end of all the touring they have in the pipeline, they haven’t grown a few inches. These extensions of leg and arm are required to gain maximum effect from the interactive projections that follow the dancers wherever they move. And because the stage is at a steep rake, to show the feats of light at their best the dancers are often splayed on the floor face down, crawling, rolling, merging into piles of bodies or shadowy shapes that might be animal or vegetable. There’s a whole sequence in which the electronics take centrestage and dance to their own music.

The floor pieces are interspersed with standing sequences in which dancers in twos and occasional threes perform against sections of the floor that rise to vertical. Now the bodies are identifiably human, and for the first time, we see their faces. But even now they appear as if unconscious, asleep with eyes open. Here the interaction between the dancers and the symbiotic technology perhaps becomes more evident to informed sections of the audience though there’s a sense that for many, what’s happening is a mystery. A couple emerges, their movement enhanced by a dazzling array of video fields some accompanied by sound, all of this manipulated by the dancers themselves. But equally, this might be interpreted as a couple pinned down in some technological nightmare not of their making. At another point the couple shift position against a white background, their grey shadows lumbering behind them to what sounds like the rumble of the Earth moving at its core. Though Gideon Obarzanek has deliberately opted for a world in which the line is blurry, it occurred to me, especially on this second viewing of Mortal Engine, that to engage with this work fully, the audience could do with a dramaturgical hook that makes it clearer just who’s zooming who.

So while images dazzle, the strength and prowess of the dancers impresses mightily, we watch in silent awe and wait until the slightly cheesy laser sequence for our moment of zen, our real engagement with the interaction that’s occurring in this work. The first 40 minutes reveals a flat, ominous world in which human and ‘other’ beings are mysteriously moving and being moved or colonized. In the vertical world, the inhabitants are asleep, every move exaggerated by the light and sound that surround them. Nothing in the scenario hints at the reality of the performer-technology relationship. Only at the end, do we get the matching gesture we’ve been craving, the sense of human agency intervening in the technological landscape, taking control of it however fleetingly and with this moment comes the ‘wow.’

–

Chunky Move, Mortal Engine, direction, choreography Gideon Obarzanek, performers Kristy Ayre, Sara Black, Amber Haines, Antony Hamilton, Marnie Palomares, Lee Serle, James Shannon, Adam Synnott, Charmene Yap, interactive system design Frieder Weiss, laser & sound art Robin Fox, composer Ben Frost, set design Richard Dinnen, Gideon Obarzanek, lighting design Damien Cooper, costume designer Paula Levis; Malthouse Theatre, Melbourne, Mar 4-8; Dance Massive, Mar 3-15

PHOTOGRAPHS OF DANCE PERFORMANCES TRY TO CAPTURE MOMENTS OF GREATEST FINITENESS, OF ABSOLUTE CRYSTALLIZATION INTO STILL, PERFECT, COAGULATIONS OF DANCING ENERGY. CUT EVERY ONE OF THESE MOMENTS OUT OF A DANCE, AND WHAT REMAINS IS MICHAELA PEGUM’S LIMINA. WHAT REMAINS IS, IN THE RIGHT SENSE OF THE WORD, IN-BETWEENNESS.

While everyday motion is an exercise in energy conservation, dance, by definition, aims for the opposite. It is movement characterized by excessive expenditure of energy, of finding and utilizing the longest path between the two points of stillness. Limina not only seeks out the longest path, but stretches it ad infinitum, develops it sideways, unproductively, for its own sake, obstinate to the requirement of giving us culmination, climactic points of complete satisfaction. Pegum dances around instead, skipping highlights, turning our attention back to the hard labour of gradually building movement. Instead of stretching out striking poses, she lingers on moments of no activity, before launching into another neverending quest for phrase finish. In Pegum’s dance, the work is never finished, the end of a phrase never recognised and lit by its own glorifying light. Limina goes, thus, against the entire conventional narrative of self-realisation as movement-towards-result.

It is salutary to note that Pegum’s objectives may not be so different from those of The Fondue Set in No Success Like Failure, another Dance Massive performance. Although stylistically completely different (Fondue Set have worked with Wendy Houstoun, developing a Forced Entertainment-esque aesthetics of a failed small-town spectacle, with all the pop humour this implies, while Pegum creates minimalist, abstract understatement), both work towards stretching out the periods before and after what we normally anticipate as the salient moments in a performance. But, while The Fondue Set twirl and explain, stumble and apologise, Pegum merely dances, with great focus and enormous input of energy. There is more here than just a drive towards stillness, dancing down-time, symptomatic of so much contemporary dance as a putative rebellion against the ever-accelerating rhythms of hyper-modernity. Historically, dance has had a long and unresolved relationship with incidental pornography: all those flashing crotches, bare toned limbs, perfectly sculpted females showered with flowers, idolized. While it has taken half of a century to wrestle the artform away from the dubious company of pole dancing and fertility rituals, the dance stage is still one on which we expect young, toned women to be strikingly beautiful for us.

Both the Fondues and Pegum take the path diametrically opposite to what Germaine Greer has deemed exhibitionist female art, from Sam Taylor-Wood to Tracey Emin. Instead of giving maximum, ironic titillation with an accusatory question mark, they elude, they hide, they betray. Refusing to bring their actions to a closure, an expected, gratifying conclusion, they are stretching the moments of their own power, as stage performers, as women. The question asked may be one about purpose and futility. If the wow-moments are edited out, if only hard work remains, will we recognize it and applaud?

In Limina, the stage reveals first Pegum’s body prostrated on the floor, from which she slowly, jitteringly rises, and slowly falls again, struggling to complete the phrase. The focus is never more than soft: the soundscape of crumbling waves, singing birds or electronic murmur; the light that lags behind, precedes the body, or lights the wrong fragment of it; and movement that struggles towards completion it then evades. Pegum is more interested in the work than in the result. The power—understood as the predatory, sexual power of triumphant tick in all the expected boxes, and more—is always out of her reach, as she dances with maximum investment, giving up all the moments in spotlight to pursue yet another a propos-of-nothing.

The choreography, while unabashedly feminine—fluid curly shoulders, flexible joints—ends up in entangled, ongoing dead-ends that resemble the insectoid phrases in Chunky Move’s Mortal Engine. Legs and arms wrapped around joints, limbs radiating in otherworldly silhouettes. However, where Mortal Engine delivers one complete, victoriously disturbing image after another, Pegum’s liminal poses never resolve in anything other than another fluid change of direction. On two occasions, her long, nimble body slowly glides down the wall, in a spotlight that loses interest before she starts and before she finishes her painfully protracted collapse. Long filigree hand movements stop short. Failure to strike a satisfactory pose may reflect on her face, as she looks alarmed that her entire body is collapsing in clunky spasms into a heap around her. With doubt and uncertainty, entire phrases are repeated twice—and what is less conclusive than a mirrored diptych? At other times, composed slowness is replaced by a frenetic accumulation of small-grained movement, limbs flying around with a disconcerting lack of result. With her arms stretched forward, her leg raised, with her knee between her elbows, Pegum flaps like a mutilated butterfly, appearing confused and disturbed. There is great humour and even greater intelligence behind this subtle, elegantly understated choreography. Finally, in a deliciously appropriate conclusion, Pegum crawls back into her initial pose, yet eludes our expectation of a circular finish, rising on her wobbly feet. Before she completes the ascent, and raises her head towards us, the light wanders out and off.

Bataille links thanatos back to eros through this walk on the edge of excess: sex as expenditure of energy over and beyond what is required for purposes of reproduction. This excess, overflow, is what we register as intimacy, if not love, and is what Pegum creates on stage. The intensity of Limina comes from the raw eroticism of will, of agency, as Pegum never drops focus in this meander without conclusion, never lets herself rest in a pose. When she does rest, it is in moments of respite, precisely those normally edited out of a finished dance. From the body in total focus, she occasionally breaks into the unceremonious stop-points of heavy breathing, sweaty stillness. The flipside, according to Bataille, is self-destruction by exhaustion. By avoiding delivery, Pegum lingers in her own agency, avoids the moment where, having delivered a climax, her own body will become superfluous.

–