Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

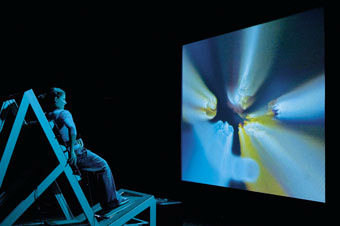

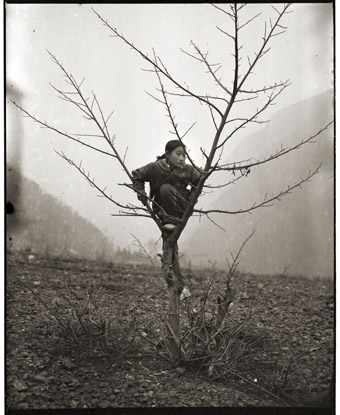

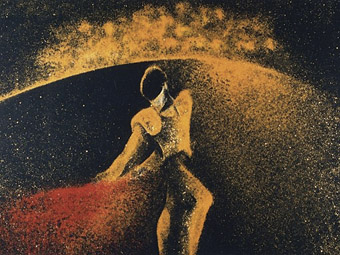

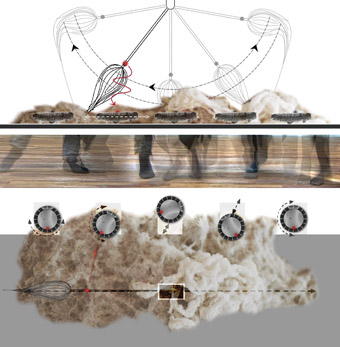

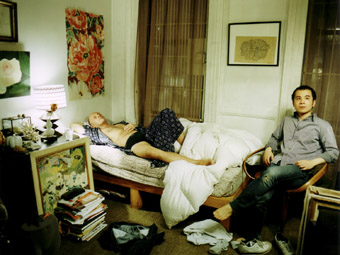

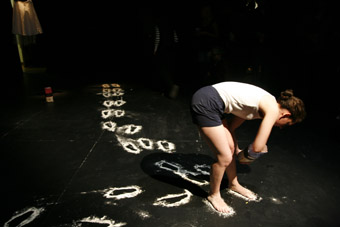

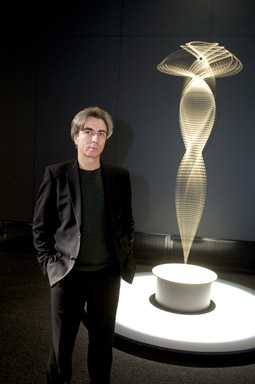

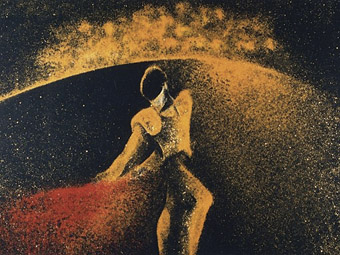

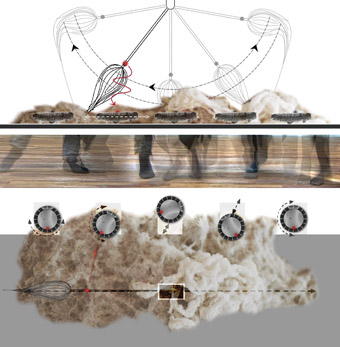

transmute collective, Intimate Transactions (2005)

photo David McLeod

transmute collective, Intimate Transactions (2005)

Keith Armstrong is a leading Australian artist with an integrative and collaborative mastery of diverse practices and media. Since 1993 he has created site-specific electronic art, networked interactive installations, performances and art-science collaborations, shown successfully here and overseas.

Central to Armstrong’s work is the notion of “embodied media”, which has taken his work and the creations made with Transmute Collective beyond conventional text and mouse-based interactivity into the potent realms of sensory and perceptual responsiveness.

Armstrong is currently exhibiting as part of Bathurst Regional Art Gallery’s Showing Off, a large-scale new media art survey exhibition curated by Daniel Kojta, running August 7 to September 20, 70-78 Keppel St, Bathurst, NSW. www.bathurstart.com.au

Transmute Collective’s acclaimed networked interactive installation, Intimate Transactions, now touring for Visions of Australia, completes its journey by connecting participants between the Albury and Dubbo Regional Galleries through physical action and empathetic virtual engagement. September 18-October 18.

A recent work, Knowmore (House of Commons) will appear in Montreal at the Elektra media arts festival in May, 2010.

A new large-scale interactive work, Triple Bypass, “based around the cultural dimensions of climate change”, has first stage funding from the Inter-Arts Office of the Australia Council. The work’s focus underlines Armstrong’s ecological interests—not only environmentally but in terms of the way that “scientific philosophical and ecologies…influence and direct the design and conception of new artworks.”

Documentation and images from Armstrong’s works, including those with Transmute Collective, along with research and writings can be found on his website: http://www.embodiedmedia.com.

interactive re-futuring

keith gallasch talks to keith armstrong

the ecology of interaction

greg hooper: intimate transactions

between research, philosophy & documentation

barbara bolt: intimate transactions, the book

interactive mysteries

greg hooper: shifting intimacies

animating the interactive spin

greg hooper: knowmore (house of commons)

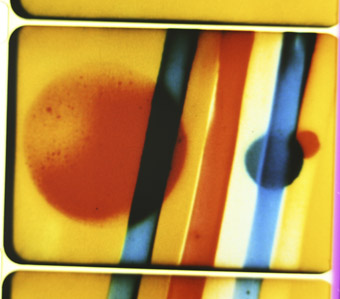

Chronology Arts Ensemble playing Alex Pozniak's Illuminations

Formed in 2007, Chronology Arts is a new force in contemporary art music in Sydney, promoting and producing the creations of young composers with its young ensemble. The group is adding breadth and complexity to a new music scene in which groups as diverse as Ensemble Offspring, Halcyon and Song Company and adventurous New Music Network concerts stimulate an audience greedy for new challenges as well as opportunities to reflect on 20th century innovations that live on.

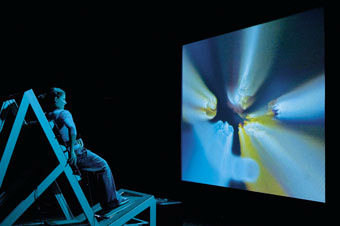

Chronology Arts will announce its 2010 program on September 4. Back in May, I attended its Gradations of Light concert in CarriageWorks' vast Bay 17. Undaunted, Chronology Arts filled the space with new music, light, responsive video art and ideas and, in Andrew Batt-Rawden's Rise—Gradation from Darkness to Light, moved musicians around and through the audience.

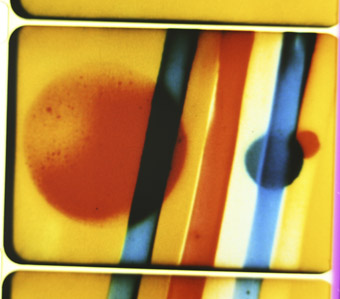

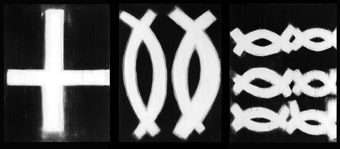

Rise emerges from a cello singing high against dark percussion. Other instruments are added, playing first from behind the audience and then joining the initiators in a rich texturing and swelling of sound with violin, viola and bird-like flute. The ensemble is supple, enveloping, accelerating like wind. A saxophone warbles. The pulse quickens into an aberrant march and then a strange dance, dwelling on an affecting flute passage, rising to ecstatic saxophoning, like the full glare of the sun. The world fades in a slow release breathed in long, sustained notes, the musicians ambling back into the dark. On a small screen in the stage foreground, coloured shapes have reconfigured themselves mysteriously in designer Ed Saribatir's Light Instrument, apparently in direct response to the played score.

Composer Batt-Rawden writes in his program note that sun-rise inspired the work, providing a metaphor for “facing our demons, rising to new challenges.” The result is, as he writes, something “of a primordial ritual…that touches on our cognitive-animal strength.” “Appollonian” might be an apt description for a work suggestive at once of a primal reality but at the same time one blessed with a sunny rationality—there's lucid construction, a sense of occasion and moments of intense feeling but with an optimism that elegantly eschews high drama.

Melody Eötvös' cool Figure Seven contrasts starkly with the warmth of Rise. It's “based on six digitally created creatures from a software program designed to map out evolutionary processes. Each section unfolds from a collection of pitches derived from a 'grid' of 36 squares superimposed over each picture (6 pitches along the y axis and 6 along the x axis). Therefore the subtle changes in the pitch collections mirror the gradual evolution of the images.” This is a work at once stark and delicate, its quietly insistent pulse relieved by pizzicato, downward glissandi and lyrical erhu phrasings (from Nicholas Ng), integrating an intriguing meme to this strand of Modernist evolution.

Ng's own work, Light channels: on circulation and percolation, is inspired by an 8th century Chinese text on alchemy, specifically “the flow of light energy through certain passages or channels in the human body.” The erhu is at the centre of the composition, again framed by Western instruments and tonalities. Gonging and glissandi, some striking, deep, flowing saxophone and jaunty flute and clarinet lines provide rich interplay. In a second movement solo, the erhu, increasingly and fascinatingly distorted, is amplified dramatically against pre-recorded sound (not unlike deep breathing and percolation) suggestive of physical interiority. The work then becomes almost meditative before dancing to a finish.

If there was a lot to take in aurally in Light channels, there were also visual demands. In the first movement, three large screens behind and above the musicians revealed a Rorschach-like triptych of initially abstract shapes folding in and out of themselves and gradually revealed to be a meditation on a tree, splitting, fusing and evolving. It's a work by Christopher Fullham that could stand on its own; here it seemed aptly complementary. In the second movement, clouds drifting against blue sky and criss-crossing each other proved less engaging if providing a kind of visual bass line in their quiet monumentality.

In Illuminations Alex Pozniak aims to generate “an elastic interaction of cells of material across the ensemble…with the instruments and instrumental section (winds, strings, electric guitars) negotiating different degrees of cohesion and liberty in textures that represent light as a dynamic source of energy.” The work opens with high whistlings and a growing sense of vibration replete with tumbling sax notes and rapid flute runs, high strings and guitar harmonics. Three electric guitars swell the scale of Illuminations, each soloing distinctively while accompanied by the other two, ranging from austere lyricism to a chugging slo-mo heavy metal and artful feedback before being joined by the balance of the ensemble in a beautiful collective drift to silence.

Scott Morrison's video response to Illuminations comprises unfocused lines—black, grey, white—running in vertical parallels and then intersected by horizontals. It's a gentle, unhurried work, serenely accompanying the growing passion of the score rather than mimicking its intensity.

Gradations of Light was a satisfying multimedia experience: an ambitious concert built thematically around light (actual and metaphysical) but also, for the most part, dextrously realised in inventive staging and engaging projections. Conductor Morgan Merrell calmly ensured that the ensemble ably managed the numerous demands of these welcome new compositions.

Works by Alex Pozniak will be the focus of a September 8 concert at Sydney University's Manning Bar, and the 2009 Chronology Arts season will end with a concert titled Playing in Tongues, December 9 at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music.

Chronology Arts, Gradations of Light, composers Andrew Batt-Rawden, Melody Eötvös, Nicholas Ng, Alex Pozniak, conductor Morgan Merrell, flute Jane Duncan, clarinet Toby Armstrong, saxophone Andrew Smith, viola Luke Spicer, cello Eleanor Betts, viola/violin Victoria Jacono, erhu Nicholas Ng, guitars Matthew McGuigan, Zane Banks, Matthew Kurukchi; CarriageWorks, Sydney, May 15; www.chronologyarts.net

RealTime issue #92 Aug-Sept 2009 pg. web

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

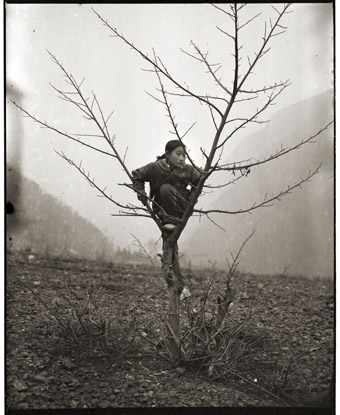

A Nest of Cinnamon

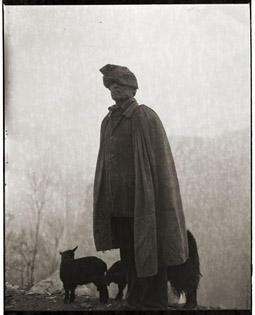

photo Damian Vincenzi

A Nest of Cinnamon

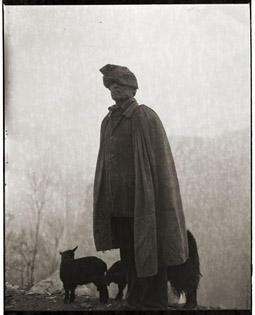

Cross-cultural collaborations can produce surprising hybrids, especially so when the resulting collision is one of Australian-Greek, Chinese and Japanese cultural and aesthetic practices. Angela Costi, poet and performer, quietly confronts her audience dressed in a spiffy yet heavily symbolic black suit. In contrast to this rather business-like cloak of death, musician Wang Zheng Ting, covered in an azure silk gown, solemnly holds before him an enigmatic imbroglio comprising grained wood, labyrinthine finger holes and a stainless steel mouthpiece. It’s a musical instrument the like of which I have never seen, and the wail that it produces is reminiscent of a flightpath borne of great pain.

The driving motif behind A Nest of Cinnamon, a work in progress, is the phoenix; which is appropriate really. Resurrection, or the release of human consciousness from its earthbound location in order to reshape itself elsewhere might very well be a type of ‘creative development period’ in and of itself. Time, space and matter compressed into an eternal present, cross-cultural arts practice is similarly characterised by a Borgesian premise, ie what if..?

Creative development showings are potentially testing for all concerned, particularly so here. The Japanese offering, rather than being performed live, is a video presentation of work completed in Japan some months earlier. It’s more perplexing that Stringraphy, the performance troupe who transform gallery space into acoustic installations that screech with the sounds of global transmission, is the basis for this performance’s rhythmical component. Consequently, the rhythms of the overall performance are simultaneously live, pre-recorded and split between watching bodies move through space and hearing the pre-recorded sound of Stringraphy’s musical instrument. Of course, the rhythms of video and live performance are very different. Digital sound and what the audience hear as Stringraphy pluck decentered lengths of monofilament stretched and threaded through polystyrene cups can in no way compare to the sound and active rhythms of Stringraphy’s ensemble members seen projected on a rear wall as each moves through a gallery space. A dilemma to be sure, but one that teases at the brain in the same way a prototype model of Stringraphy’s installation cum musical instrument does: one constructed in real time centre stage by the creators of Nest of Cinnamon in order to familiarise this Australian audience with the presence of the monofilament and styrene confabulation that can also be seen onscreen.

A Nest of Cinnamon

photo Damian Vincenzi

A Nest of Cinnamon

And yet I sense that all is well in this performance. In spite of the difficulties in understanding the context of this work there occurs a moment onscreen when a Stringraphy ensemble member steps forward and utters something in unintelligible Japanese. Almost immediately, the oblique rhythms of Angela Costi’s poetic presence and the piercing tremolo of Zheng Ting’s metal and wood imbroglio coalesce with Richard Vabre’s subtle shifts in red, orange and yellow light. This shift in complexion is less to do with external stimuli and more a case of individual perception. I can now see how this performance might integrate, once in its completed state. The intricate rhythms of Stringraphy’s global transmitter will, like all successful collaborations, intermingle and underpin Costi and Zheng Ting’s reflection upon the resurrecting spirit. From Canterbury-Bankstown to Reservoir, via Beijing and Okinawa, the story of what was once called migration is still one of people incinerating the past for the purpose of igniting a future. The global flow of human traffic is still, and forever will be, consistent with the resurrecting myth that is the flight of the phoenix.

A Nest of Cinnamon: a work in progress, dramaturg, director Christian Leavesley, poet-performer Angela Costi, sheng performer Wang Zheng Ting, Stringraphy Ensemble: Midori Yaegashi, Mitoko Shinohara, Momo Suzuki, Kiku, lighting Richard Vabre, producer Keiko Aoki, Global Japan Network; Arts House Meat Market, Melbourne, June 19

RealTime issue #92 Aug-Sept 2009 pg.

© Tony Reck; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

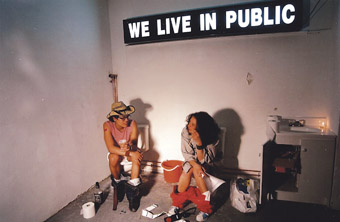

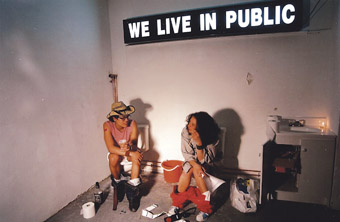

Nowhere Fast, Dance North

AN UGLY, GREY, DEAD END LIT BY A SINGLE STREETLIGHT AND OBSERVED BY THE COLD RED EYE OF A SURVEILLANCE CAMERA MOUNTED HIGH ON A WALL FORMS THE UNSYMPATHETIC SET OF DANCENORTH’S NOWHERE FAST. THE GRUBBY WALLS BEAR THE PENTIMENTI OF EARLIER TRAGEDIES—IS THAT A BLOODSTAIN IN THE CORNER?—BUT GIVE LITTLE ELSE AWAY. AS THE WORK UNFURLS THE SET FULFILS ITS PURPOSE, REPRESENTING BOTH THE OBSTACLE AND THE VOID AGAINST WHICH THE TWITTERING MASSES HURL THEMSELVES IN THE SEARCH FOR MEANING OR, AT THE VERY LEAST, SOME ATTENTION.

Nowhere Fast is Ross McCormack’s first full length choreography. The New Zealander has danced with the Royal New Zealand Ballet and Australian Dance Theatre, winning a Helpmann Award in 2004. He moved to Belgium to work with Les Ballets C de la B, and part of the idea for Nowhere Fast arose from the “urban loneliness” he observed living in the most densely populated country in Europe, as well as his concern for a generation experiencing “life at one remove” through a variety of new media. His principal visual influence is the work of American photographer Gregory Crewdson, whose meticulous set pieces reek of alienation within suburban ordinariness.

The musical score is the work of Jody Lloyd in his first foray into composition for dance. Much of it was developed in his studio, referencing McCormack’s rough ideas, Crewdson’s photographs, and DVDs of the work in progress. He spent the final two weeks prior to the show in Townsville working directly with the company, honing the atmosphere and pace of the varied soundtrack. It collages everything from ground shaking car stereo ‘doofdoof’ to Maria Callas to “squashed and pulled Hawaiian steel guitar”, solidly underpinning the action.

McCormack says he asked the six dancers to “put away technique to develop character, explore and express yourself emotionally.” The physicality, youth and raw strength of the Dancenorth ensemble rises to the task from the moment the work commences with a naked young man clambering over the wall to stand vulnerable and semi-exposed in the twilight. Initially, it’s as though D’Arcy Andrews, so unsure and awkward, has found himself there unexpectedly; and like the audience, is trying to figure out what’s going on. He pulls on underwear—dressing, undressing and clothes swapping are recurrent themes—and begins scrawling on the wall. Luke Hanna appears, fighting unseen demons, evoking Munch’s The Scream in his facial contortions and self-flagellation. Andrews observes tentatively, briefly mimics Hanna’s wild movements; Hanna licks Andrews, leaving a trail of bright blue across his body, but it is an arbitrary mark with no connection or empathy evident.

Hsin-Ju Chiu enters and Hanna and Andrews observe her warily as she primps and poses. Alice Hinde and Nicola Leahey join her and the three begin compulsively flicking their hair in unison, laughing flirtatiously but manically in a dance where the flicking becomes scruffing becomes violent scratching. The heels come off to be banged and dragged against the walls, but attention spans are short and Hanna is off tweaking the surveillance camera, and a shaking skinhead is emerging from the shadows, graffiti-ing the walls, chalk in both hands.

The shaking man, Joshua Thomson, draws, increasingly frenetic, leaping and circling rapidly, and suddenly he is a human compass, his head centred on the wall and his outstretched arms drawing a near perfect circle as he spins on the spot. He stops and turns, resting his back against the wall, arms still wide—a latter day Vitruvian Man for an instant, having just created a bespoke frame for his exact proportions. As he slathers his head with magenta paint, his eyes and veins popping, a shot rings out and Thomson convulses in death throes. Writhing in Goya-esque agonies, he then enacts suicide by decapitation, disembowelment, strangulation, in a distressing and relentless, but utterly compelling sequence.

Atop the wall perch the girls, a giggling trio, reaching toward Thomson, chirruping platitudes. “Awww, honey!”, croons Nicola Leahey inanely as the consummate Barbie doll. The incongruity of their responses reaches its height as Thomson opens his mouth to scream and they literally begin to drag him up the wall by his open mouth, before dropping him in a heap in the corner.

This scary juxtaposition of vacuousness and sheer muscle plays out in several scenarios within the work—another frantic sequence sees the group fling Hinde through the wall. They look at each other in silence. A dog barks in the distance. Andrews lamely attempts to reassemble the broken pieces of the wall to conceal Hinde’s inert form. Hsin-Ju holds out her mobile phone and films the accident scene. Leahey laughs and disrobes to divert attention to herself, running back and forth, dress on and off, posing against the wall art like a demented package tourist doing Rome in a day. The boys are momentarily amused before they too start running and stripping, looking off into the distance to see who’s observing them.

In the final sequence all the dancers perform a repetitive floor-slapping routine in unison, like a wordless prayer for connection. But, frustrated by their own clueless self-obsession, it is a one-step-forward, two-steps-back exercise in futility. A shirtless Hanna personifies their internal stasis by contorting his jawdropping physique into a state of semi-mobility, a marble Rodin under the white-blue light. All are as disparate in the end as they were in the beginning.

Nowhere Fast left some of its audience scratching for a storyline, accustomed as they are to the strong narratives in the works of former artistic director Gavin Webber. McCormack’s guest work taps the same vigour and grit the Dancenorth ensemble have become renowned for, perhaps less poetically, but to powerful, confronting and often unexpected effect. The disjointed feel of the piece; the frenzied action interspersed with loitering, watchfulness, imitation and self-conscious posing; the frustrated attempts at meaningful connection; all successfully capture the mood of an age where we are so busy media surfing in an effort not to miss anything that we are in danger of going nowhere, fast.

Dancenorth, Nowhere Fast, choreographer Ross McCormack, performers D’Arcy Andrews, Hsin-Ju Chiu, Luke Hanna, Alice Hinde, Nicola Leahey, Joshua Thomson, composer Jody Lloyd, lighting Natasha James, Townsville, July 1-5

RealTime issue #92 Aug-Sept 2009 pg. 36

© Bernadette Ashley; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

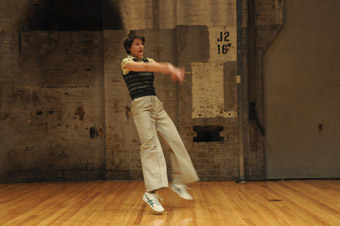

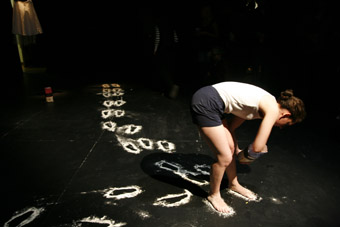

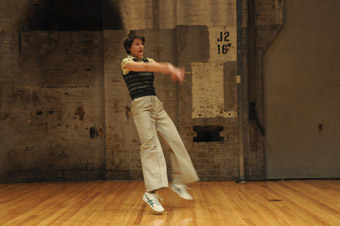

Martin Del Amo, It’s a Jungle Out There

photo Heidrun Löhr

Martin Del Amo, It’s a Jungle Out There

MARTIN DEL AMO IS UBIQUITOUS. HE POPS UP WILD HAIRED AND UNDIE-CLAD SO OFTEN ON THE SYDNEY UNDERGROUND DANCE LANDSCAPE THAT EXPECTATION IS FASHIONED BY FAMILIARITY. YET HE SURPRISES. HIS INSOUCIANT BELIEF IN THE INHERENT WORTH OF WHAT HE HAS TO SAY GIVES HIS WORK A TRADEMARK INTENSITY THAT RESULTS FROM THE PIQUANCY OF FASCINATION AND RESEARCH. WHATEVER DEL AMO IS INVESTIGATING, IT IS DONE WITH A FEROCIOUS AND METICULOUS ATTENTION THAT IS A LUST TO DISCOVER, UNCOVER AND REVEAL.

It is this lust that saves It’s a Jungle Out There from cliché. The work’s stated intention is to explore “the modern city as an ever changing organism.” Within such a topic lies potential for trite statements about regulation, hurried temporalities, frayed nerves and harried obedience. And Del Amo does make such statements. But he tempers predictability with the truths that emerge from research. He does not merely condemn ‘the city’ as a Gomorrah of undisputed self-interest; he also investigates it as a site of fertile possibility. Dance becomes embodied investigation and his body asks: what is it to exist in this landscape?

The invited opening night crowd warble in. Just sitting atop this diffuse murmur is another muffled voice. Del Amo is crossing the stage in straight lines, incessantly speaking numbers into a head mike. I am surprised by his modest and conservative clothing and tamed hair. Nearly corporate, neat, almost sharp. Gail Priest’s soundscape rumbles subterraneously and like the hum of a city goes almost unnoticed until it erupts into occasional porcelain scratches that hurt my teeth. In the black and grey space the numbers get louder and del Amo gets closer. The dancer’s shadows loom large and small, walking away from self. Numbers engorge themselves into ridiculousness then transform into pithy scenic descriptions. Del Amo’s voice remains incessant and constant, occasionally yelling to break the hypnotic patina. Now the script is akin to rapping, and rhythm is meaning. This first section is building with an almost foreboding rhythmic curve that stops me laughing at the very funny things he throws at us. As the performance unfolds this rise to climax and subsequent release will occur with regularity, even predictability, but it still works.

In his attention to detail, del Amo asks me to notice it too. In this opening section, walking is the dance. Each step is lovely. Each step is soft, loving the ground. Focused feet articulate bones, shifting in repetition and variation. In cities we walk. Cities make us walk. And this particular walking, slightly knock-kneed, sure but not bored, is both heartbeat and journey.

The climax rips apart the hypnosis of repetition. Lights flash and flare blindingly to shake us out of the zone. Almost reassuringly del Amo has removed his smart city shirt and his shadowed and naked torso swings and creaks like a rusty gate in the wind.

Section 3 presents as a lecture. Quietly del Amo brings out a microphone stand and delivers a monologue about a particular kind of urban agoraphobia where sufferers are compelled to build life-like models of the outside world inside the safety of their homes. Like so many of the artist’s observations, the potency resides in an admixture of disquiet and humour.

The disquiet tumbles into section 4 where del Amo runs and runs, round and round, carving the neverending figure eight pathways that now sit layered on the linear grids, mashing up space, making mess. To Priest’s repetitious pulse he runs backwards and forwards, he dodges, weaves, reaches, turns, twists, throws with a kind of focused anxiety rooted in the torso. The legs keep running. He sweats. I am getting warmer. And I realise that one of del Amo’s gifts is the creation of atmosphere through an embodiment that knows exactly why it is doing what it is doing and will keep on doing it. His use of repetition, development and variation allows these atmospheres to build through diffusion, thickening of temperature and sculpted temporalities.

As his breathing calms, section 5 develops into a square dance of negotiation: small steps forward, back and side create little lines of direct action. Restraint and constraint drive the performance down to mad quantum ruminations. Do the little red and green men who live in traffic lights change location? Do they talk to each other?

Emerging from this performance I am close to wordless. Like leaving a David Lynch movie, I don’t quite know where I am. The sensation is dreamlike, but not fuzzy. This dream is ripe with observational truth, clarities born of flesh, rhythm and atmosphere. It is not the clarity of intellect but of mindful body-in-place. This is because Martin Del Amo is a researcher. He does not seek to manufacture but to authenticate. He writes: “as part of my research for this piece, I conducted a series of excursions to heighten my perception of the city’s impact on the body. They included walking backwards through Sydney’s CBD, walking blindfolded along Parramatta Road during rush hour and crawling on all fours in the historic part of The Rocks.” From these bleeding-for-art excursions, blood, body, breath and rhythm speak.

Campbelltown Arts Centre Contemporary Dance Program, It’s a Jungle Out There, performer, devisor Martin del Amo, composer, live sound Gail Priest, lighting designer Travis Hodgson, designer Paul Matthews; Campbelltown Arts Centre, Sydney, June 25-27

RealTime issue #92 Aug-Sept 2009 pg. 36

© Pauline Manley; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

KAREN THERESE’S THE RIOT ACT FOR CAMPBELLTOWN ARTS CENTRE IS A GRUELLING PORTRAYAL OF THE SYMPTOMS AND CONSEQUENCES OF SOCIAL DISADVANTAGE.

A conventional opening satirically trashes the caring rhetoric of politicians, bureaucrats and welfare NGO executives, their public platitudes eviscerated by a string of mobile phone calls they insist on answering. A subsequent media circus bribes the disaffected to perform badly, as expected, while behind the action huge projected graphs of crime rates and domestic abuse statistics in Sydney’s outer suburbs pulse by. Then everything changes. We’re transformed from our addicted media watcher selves into clinical observers of caged animals, society’s victims, in a world where time slows almost to a numb halt. The Riot Act has mutated into a largely mute, contemporary performance work where appalling states of being are doggedly examined.

This imploding non-time is interpolated with outbursts where the subjects abuse themselves and each other in acts sexist, racist and seemingly psychotic. Eventually a riot erupts from an apparently incidental trigger, igniting the fuel of accumulated pain and the delirium of insistent state surveillance. It’s a riot without an agenda, unplanned and with nowhere to go except more punishment and abjection—guilt confessed to the media, save for one dissenting voice.

The Riot Act offers neither small ‘l’ liberal comforts—there is rarely reassuring compassion in this non-society, rarely any reflection, sustained games, completed art—nor radical analysis. The riot itself is generalised: it doesn’t explode from a single motive—resisting or enacting racism in Cronulla or protesting police arrest in Macquarie Fields. Therese appears to be saying, specific trigger or not, the potential for riot is ever present given the abject states her subjects must endure. To amplify the danger inherent in this condition, she has chosen, in the style of Les Ballets C de la B, to convey a sense of real threat with performances that read like improvisation, unpredictable and sometimes visibly dangerous. But there is none of the Belgian company’s redemptive choreographic and musical collectivity. Therese’s performers are not allowed such spirit or virtuosity. It’s a risky strategy that inclines the Riot Act to one-dimensionality, melodrama (compounded by a point-scoring sound score) and formlessness. That said, the performances are passionately committed and, like a bad dream of a life you would not want anyone to live, the Riot Act worries at you weeks after you’ve peered into its darkness. The Campbelltown Arts Centre has boldly championed a challenging if challenged work.

The Riot Act, director Karen Therese, performers Matthew Day, Matt Prest, XX, Lalau Leo Tanoi, Latai Tauoepeau, Lizzie Thompson, design Mirabelle Wouters, Lara Thoms, sound design James Brown, Gail Priest, dramaturg Chris Mead, movement Kathy Cogill, video Scott Otto Anderson, lighting Paul Osborne, producer Annemarie Dalziel; Campbelltown Arts Centre, June 4-13

RealTime issue #92 Aug-Sept 2009 pg. 38

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Rosie Dennis, Fraudulent Behaviour

photo Heidrun Löhr

Rosie Dennis, Fraudulent Behaviour

IS THIS THE REAL THING—ROSE DENNIS, IN A SHOW CALLED FRAUDULENT BEHAVIOUR, WITH WHITEBOARD, CHATTING AMIABLY TO US LIKE A RACONTEUR, LECTURER, STAND-UP THEORIST, FOR THE BEST PART OF AN HOUR? OR A FRAUD, A FAKE—NOT THE FAMED, REAL ROSIE DENNIS OF 20-MINUTE TOURETTE-ISH BOUTS OF QUICKFIRE POETRY AND SPASMS OF LOVE AND OTHER ANXIETIES.

This Rosie Dennis whiteboards Nietsche’s “We need lies in order to live”, rattles off a long list of everyday and sometimes very funny, lateral untruths that illustrate how we deceive others and ourselves and then breaks away to have a familiar word or two with a decoy duck in a bowl on a plinth. She inexplicably dances at length in loping, elegant strides and tight turns to Tom Waits. That seems innocent enough, unless she’s in a reverie, a private lie of being somewhere or someone else and ‘big in Japan.’

Next on the whiteboard is Herman Hesse: “There is no reality except the one contained within us; that’s why so many of us live unreal lives.” We are introduced, consequently, to an imaginary childhood friend, Elvira, who subverts the laws of physics and time and will take Dennis “to paradise one day.” This comforting lie segues into an account of a couple living out another, the ‘paradise’ of co-dependency. And on Dennis goes, delving into our snowdome reality (a sustained image both spoken and actual in the show) with a Paul Austerish intensification of coincidence and misconception as she recounts taking a long, perhaps potentially risky cab ride.

This other Rosie Dennis is an amusing then worrying confider, netting the sudden moments of self-awareness she prompts, trawling us with her into uncharted metaphysical outer space. By the end we might be missing the original manic Dennis a little, but this laidback substitute is just as scary, and possibly not a fraud at all, but the same person. Whatever, this new Rosie Dennis persona is an intriguing development, still evolving and not quite on top of her play with her puppet-ish props. But it’s lovely to be lied to so convincingly.

See our online producer Jo Skinner’s response to Fraudulent Behaviour, a video excerpt from the show and links to archived RealTime articles about Rosie Dennis.

Fraudulent Behaviour, performer, devisor Rosie Dennis, trumpet Simon Ferenci, Performance Space at CarriageWorks, June 11-12

RealTime issue #92 Aug-Sept 2009 pg. 38

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

{$slideshow} THREE RECENT PRODUCTIONS MOUNTED AS PART OF THE VICTORIAN ARTS CENTRE’S FULL TILT PROGRAM HAD ME PONDERING THE SCIENCE OF INTERPRETATION. THE FIRST, A REMOUNT OF RED STITCH ACTORS THEATRE’S WONDERFUL RED SKY MORNING, WAS A BIT OF A SCHRODINGERIAN CAT. HAVING ALREADY SEEN IT IN ITS INITIAL INCARNATION AT RED STITCH’S TINY HOME IN ST KILDA, I WASN’T SURE HOW IT WOULD SURVIVE WHEN TRANSPLANTED TO THE BIGGER BOX OF THE ARTS CENTRE’S FAIRFAX STUDIO. I’M STILL UNCERTAIN WHETHER IT SURVIVED OR NOT.

red sky morning

I like to think the cat is alive. In Erwin Schrodinger’s famous thought experiment, we are meant to imagine a cat in a box along with poison which may be released without our knowledge. According to the physicist, the cat is both alive and dead until the moment the box is opened and, lo, we can observe the reality. Schrodinger wasn’t advocating the killing of cats, and I hope that nobody’s actually followed through with the experiment. But he was attempting to illustrate the limitations of a science that logically implied the possibility of incommensurable realities existing simultaneously. Which sounds to me suspiciously like art.

The play is, to my mind, one of the finest products of creative collaboration in years. It traces a day in the life of a family of three, all infected with a heart-wrenching depression that takes form in various ways. Mum suffers from a painfully realistic alcoholism that does away with simple clichés of the happy/angry/functional/dysfunctional drunk. Father is a painfully laconic figure whose inability to articulate his feelings has increasingly terrifying effects. Daughter’s teen frustrations make her a social pariah, unable to forge meaningful connections with her parents or peers. There is no obvious source for the dangerous black dog which menaces the family; its effects, however, are all too clear. Red Sky Morning is also very funny.

This is an astounding work of theatre that could only have resulted from an intensive association between its writer, director and performers over a long period of time. It’s exactly the kind of production I would want to see picked up by programs such as Full Tilt, allowing it to be exposed to a wider audience than Red Stitch’s considerable subscriber base alone. But of course I’m biased—having enjoyed its first outing so much, the cat is still alive for me. Transposing Red Sky Morning from a tiny St Kilda theatre to the sizeable Fairfax (which was itself curtained back to half its usual scale in order to maintain the tight forward focus of the original) may have reduced its effectiveness for newcomers, but I sincerely hope that this is a piece with a strong life ahead of it.

Simon King, Poet #7

photo Daisy Noyes

Simon King, Poet #7

poet #7

The second of Full Tilt’s most recent season of programmed works was a more difficult exercise. Ex-Melbourne playwright Ben Ellis has based himself in the UK for a number of years but his recent writing still has strong connections with the work he was producing here. One common thread is the use of apocalyptic scenarios: 2002’s Falling Petals saw the youth of a country town succumbing to a mysterious plague-like illness, while last year’s The Zombie State featured hordes of working-class undead ravaging Melbourne (RT88 online: www.realtimearts.net/article/issue88/9256). His theatre has often employed such imagery for political ends, to comment on the real dynamics and perils of contemporary culture. Like philosopher Slavoj Zizek, I’ve long been wary of the effectiveness of apocalypse as an ideological framing device—it’s all too easy (and disempowering) to imagine that radical change can only occur through a complete upheaval in society. Such scenarios, while undoubtedly terrifying, are seductive in the freedom from conventional morality and social bondage they envision, but are equally fantasies which deter us from imagining actual methods of altering the systems of power that presently exist.

Ellis doesn’t fall prey to this tendency, however, and Poet #7’s setting (or rather, settings) within a world that has undergone a cryptically-referred-to Armageddon are not accomplished simply in order to make crude comments on the problems of modern life. In fact, the setting would seem almost superfluous if it didn’t afford Ellis the chance to produce some wonderfully evocative poetry. The title of the piece refers to a poet recalled by one of the four narrators—a poet destroyed by a bomb blast while clasping the speaker’s hand, and which hand stays unwittingly clasped by the dazed speaker as he runs in terror from the scene.

We learn very little of the titular poet, and over the course of the play we don’t learn an awful lot of its characters either. Ellis’ script gives us four voices that each inhabit a different temporal zone. Though they’re related in various ways, it’s up to the audience to piece together a narrative from these fragmented chronologies. While it’s not unusual for theatre (or other art forms) to play with time in this way, it’s rarer to witness a work in which each character exists in complete temporal isolation.

Poet #7 is a fascinating experiment—appropriate given its lab-type setting and medical-procedural themes—but its consciously high level of formal stylisation will mean that any observer will come away with a different interpretation. Science knows, I haven’t found two people who can agree on what is actually supposed to have occurred in the piece, and responses have ranged from ecstatic to bored. Perhaps, in discovering the narrative ‘truth’ of the work, its aesthetic beauty loses focus—and vice versa. This variety of individual interpretations is itself a kind of Heisenberg Principle given dramatic expression. In any case, it’s the kind of boundary-pushing work seldom seen in a state arts centre.

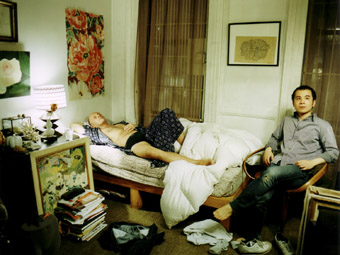

Affection, Ranters Theatre

photo James Boddington

Affection, Ranters Theatre

affection

Ranters Theatre’s recent works have been just as edgy, but as anyone who witnessed the brilliant Holiday will attest, their unique innovations are so thoroughly approachable that even the most wary of theatregoers will find themselves seduced. Affection isn’t as carefully crafted a work as Holiday, though it has developed from the same practices which informed that piece. It is styled as a hypernaturalistic series of conversations between people who appear as simply themselves—character, plot and backstory are dispensed with, and what we see is exactly what it is. This is harder to accomplish than it sounds. As audiences, we’re trained to look for deeper meanings, subtexts, the relationships and histories of the people we see onstage. Of course, we do this during Affection too, but the casual reticence of Ranters’ method makes us aware of our own role in constructing these narratives. Theatre no longer becomes a case of solving the mystery or finding the secret truth to a text, but instead forces us to consider that our own act of observing brings with it a history that massively affects our understanding of what we see. The Observer Effect, after all, isn’t limited to physics. Art is a science with infinite variables.

Red Stitch Actors Theatre, Red Sky Morning, writer Tom Holloway, director Sam Strong, performers David Whiteley, Sarah Sutherland, Erin Dewar, designer Peter Mumford; Fairfax Studio, June 3-13; Poet No. 7, writer Ben Ellis, director Daniel Schlusser, performers Edwina Wren, Merfyn Owen, Simon King, Georgina Capper, designer Meg White, sound designer, composer Darrin Verhagen, Martin Kay, Nick van Cuylenburg, lighting Kimberly Kwa, costumes Jemimah Reidy; The Black Box, June. 11-20; Ranters Theatre, Affection, text Raimondo Cortese, director, devisor Adriano Cortese, performers, co-devisors Beth Buchannan, Paul Lum, Patrick Moffatt, Anastasia Russel-Head, Heather Bolton The Black Box, Arts Centre, Melbourne, June 1-11

RealTime issue #92 Aug-Sept 2009 pg. 40

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Calibans, Zen Zen Zo, Tempest

photo Simon Woods

Calibans, Zen Zen Zo, Tempest

THERE IS SOMETHING SWEET, ENTIRELY SINCERE, SOMETHING WHOLLY OWNED BY THE CAST AND CREW OF ZEN ZEN ZO PHYSICAL THEATRE’S ADAPTATION OF SHAKESPEARE’S THE TEMPEST THAT WEAVES ITS OWN SPELL. THE TEMPEST HAS BEEN DESCRIBED AS AN ATTEMPT TO ENVISION UTOPIA WITHOUT UTOPIANISM, AND THERE’S SOMEHOW AN OVERDETERMINATION IN THIS PRODUCTION THAT SEEMS TO BE SUITED TO THE NATURE OF SHAKESPEARE’S PLAY.

It doesn’t simply stem from the energy of the mainly young cast or the eclectic fusion of high art and pop culture tailored for young audiences, but from what can only be described as a residual faith in art on its ultimate borders where, as the critic Leslie A Fiedler points out, it becomes indistinguishable from sorcery. This production actually contemplates a transformation in the fundamental structures of everyday life, a concept that shouldn’t be so astonishingly novel nowadays when it seems nothing less will halt the headlong destruction of the planet. The Tempest is the most quotable of Shakespeare’s plays, including that one line about the whole globe dissolving, leaving not a rack behind.

Lynne Bradley’s director’s notes announce that the core message of the company’s version of The Tempest is that “it is every human being’s imperative to struggle for freedom—both political and personal.” All the characters, including Prospero himself, struggle to be freed from some kind of internal or external entrapment—to write, as it were, their own scripts. It is the courtiers and the politicians who are enmired. As we enter the space, we notice that visual director Simon Woods has writ large across the cavernous Concert Hall walls what look like reproductions from the Folio manuscripts, simultaneously creating the dioramic impression of waves round Prospero’s island and generating notions of the text as either a set of discourses or set in stone by claims made in the name of The Tempest’s timelessness and transcendence. Later on, with gesturing hands, Prospero will visibly underscore the demeaning irony of being trapped inside another person’s script against this backdrop. The Tempest is a play in which the word ‘strange’ is the most frequently used adjective, and we are inducted into this promenade style theatre by wandering among living statues, tableaux of the actors who are not simply still but emanate that ‘ferociousness of being’ that Rilke attributes to the presence of his angels. The atmosphere is ‘strange’, but it is we who are the strangers.

Zen Zen Zo aim to create total theatre, with “the spoken, physical, visual and aural texts all playing equal roles in imparting the meaning.” They are also a training institute, which accounts for their need for a large cast in order to incorporate students. Physical disciplines predominate, including the Suzuki Method, Butoh and Contact Dance. All three are usefully in there, but it is the Butoh movement adopted wholesale by the Caliban Chorus that amounts to a conceptual as well as physical tour de force. Zen Zen Zo has drawn from post-colonial readings of the play, and the Calibans are portrayed somewhat as the American Indian tribes encountered by English settlers in Shakespeare’s time (Pocahontas met Ben Jonson): almost naked, hair tufts and terrifying facial war paint. These Ur-Indians who are also Butoh exponents might seem a bridge too far, but they could hardly be real Indians. Caliban was part fish, already ersatz. They are the European Other everywhere who must be taught language (as Prospero teaches Caliban) as a technique of colonial rule. In fact, the Calibans are the fantasy of the Other owned up to, swallowed and vomited forth—quite horrifying in the permutations of their degradation by the insouciant in-comers to the island. I flinched. What was magnificent, in balance, was the log rebellion, the mass enaction of Caliban’s suggestion to his outlander co-conspirators, Stephano and Trinculo, that they stave in Prospero’s head. Dale Thorburn articulated Caliban’s position well.

Music is the foundation of The Tempest: “Sounds and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not.” The music makers on stage are Ariel and Prospero, cabaret artiste Emma Dean and classic actor Brian Nason, doyen of his own Grin and Tonic Theatre Company in Brisbane: natural collaborators in terms of the play. Offstage the composers were Emma Dean and Colin Weber. Dean is a physical dynamo, snazzy, a musical virtuoso (piano and violin) and, indeed, the flighty Ariel threading the show. Nason is the ground. Properly irascible as his Prospero is, as internally conflicted, he has a lute player’s touch on Shakespeare’s language. Even in the soundaround his performance chimed. His final exchange with Caliban—“this thing of darkness I acknowledge mine”—shone with heartbreaking lambency.

Zen Zen Zo Physical Theatre, The Tempest, director Lynne Bradley, visual director Simon Woods, performers Bryan Nason, Emma Dean, Dale thorburn, Jill Guerts, Alex Mikic, Jamie Kable, Jane Cameron, Luke Kerridge, Alice Flynn, Carolyn Eccles, Jess Samin, Natalie Bak, Brigid Blanckenberg, Caesar Cordovana, Jamie Kendall, Alison McGregor, Emma Bleanay, Harriet Devlin, Krystal Hart, Oliver Skrzypczynski, Lisa Worthington, composers Emma Dean, Colin Webber, lighting designer Jason Glenwright, costume designer Angela White, set designers Drew der Kinderen, Lynne Bradley, Luke Kerridge; Old Queensland Museum, Brisbane, June 2-July 1

RealTime issue #92 Aug-Sept 2009 pg. 42

© Douglas Leonard; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Food Court, Back to Back Theatre

photo Jeff Busby

Food Court, Back to Back Theatre

THE LAST TIME I SAW BACK TO BACK THEATRE, THEY WERE FRAMED BY THE CONCRETE PYLONS OF SYDNEY’S CIRCULAR QUAY RAILWAY STATION. IN THAT SHOW, SMALL METAL OBJECTS, THE SPECTATORS BECAME THE SPECTACLE—SITTING IN BLEACHERS IN THE CUSTOMS HOUSE FORECOURT—WHILE THE ACTORS EXPERTLY PERFORMED THEIR INVISIBILITY. IN FOOD COURT, HOWEVER, THE AUDIENCE SITS IN THE CONFINES OF THE OPERA THEATRE, ANONYMOUS AND UNSEEN, AS THE ACTORS ASSUME A SELF-CONSCIOUS HYPERVISIBILITY, COMPLETE WITH RED VELVET CURTAINS AND GOLD LEOTARDS.

Food Court begins with the three musicians from The Necks making their way down to the pit to take up their positions on piano (Chris Abrahams), double bass (Lloyd Swanton) and drums (Tony Buck). The opening notes sound out their instruments, each other, and the audience, two of whom cough in response. The red curtains open to reveal a wide and shallow stage with black drapes which part as a man carrying a wooden chair comes onto the stage. Soon he has set up three chairs and two gloriously, grotesquely overweight ladies in gold leotards (Rita Halabarc and Nicki Holland) join him. They parade like gymnasts at the end of a floor routine: arching, stretching, posing and mugging you might even say. Their glitzy leotards recall the circus or the freak show, where performers with disabilities have historically been placed, and for a moment we wonder whether this show will be any different.

The reply comes soon enough, as a thinner woman (Sarah Mainwaring) enters and seats herself, her hands shaking involuntarily. The other women interrupt their banal conversation—“Have you ever had a hamburger?”—to declare, for no apparent reason, “You’re fat.” Though the insults start with a false innocence—“I don’t want to upset you but…”—they soon come without apology: “You’re fat, you’re a fat lady, you’re disgusting, you’re embarrassing, lose some weight, she can’t even talk, learn to speak English.” The phrases are discomfiting not only because the text is projected onto the black curtains but also because they seem like comments the performers themselves might have heard over the years. When the surtitles falter momentarily it is as if the abuse has become literally unspeakable.

Without landing a single blow, the second act proceeds to unleash extraordinary violence. The black drapes part to reveal a scene behind a milky scrim, distorting the silhouettes behind it and making them seem far away. The music gathers apace as the two women, all the while screaming abuse, force the other to strip slowly and dance naked. When Mainwaring lopes elegantly across the stage, the lighting shifts and what was a black shadow becomes pink flesh as she oscillates to her own hidden rhythm, oddly beautiful. Someone steps in from the side, then another and another, and soon she is surrounded by a crowd standing and pointing at her. The image recalls a schoolyard, a desolate car park, and an asylum, all at once.

When the crowd leaves the stage, the scene shifts and we see a projection of a forest and sky that looks like a Bill Henson photograph. We are in the same liminal zone that his images occupy, though instead of being on the child/adult threshold we are on the border of the human/inhuman or what has been called in the context of Romeo Castelluci’s work (a possible influence) the human/dis-human. One of the characters even calls the victim an “animal person” as they proceed to brutally and relentlessly beat her. In the midst of this violence, there are absurd demands for intimacy: from one gold lycra’d lady to another; from a lonely man (Marc Deans) to the lifeless victim. The scene reaches fever pitch when the victim wrenches the following from her body (and lone letters simultaneously dance into words on the scrim): “Be not afeared. The isle is full of noises, Sounds, and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not …” The lines are from Shakespeare’s The Tempest but by this time my febrile brain thinks of every island under the sun: the Island of Dr Moreau, Jules Verne’s Mysterious Island, John Donne’s “No man is an island”, Australia. This chain of thought is typical of the many associations that every image in Food Court creates. Finally, the back screen and scrim fall away, revealing a figure that is brave, humble and all too human.

The image fades, the music softens, and the retina starts to restore itself but the show offers little consolation; even during the curtain call one of the performers appears ill and walks off stage. She is not alone in feeling off balance—coming up into the night air I have a dizzying sense of the bends, a desperate desire to decompress. Compression is key to Food Court, which, like an elegant picture of barbed wire, depicts violence, beauty and tragedy in a single piercing image. Food Court pricks the conscience, senses, skin.

Back to Back Theatre and The Necks, Food Court, director, set design, devisor Bruce Gladwin, performers, devisors Mark Deans, Rita Halabarc, Nicki Holland, Sarah Mainwaring Scott Price, music by The Necks, set design Mark Cuthbertson, lighting design and technical direction Andrew Livingston, bluebottle, animated design Rhian Hinkley, sound design Hugh Covill, costume design Shio Otani; Luminous program, part of Vivid Sydney, Festival of Music Light & Ideas, Opera Theatre, Sydney Opera House, June 9-10

RealTime issue #92 Aug-Sept 2009 pg. 42

© Caroline Wake; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jeff Michel, Sabrina D’Angelo, The Falling Room and the Flying Room, Terrapin Puppet Theatre

photo Sean Fennessy

Jeff Michel, Sabrina D’Angelo, The Falling Room and the Flying Room, Terrapin Puppet Theatre

TERRAPIN’S LATEST SHOW CONTINUES THE COMPANY’S INVESTIGATIONS INTO THE NEW REALM OF DIGITAL PUPPETRY. IN EFFECT WHAT YOU GET WHEN YOU SEE THEIR NEW SHOW, THE FALLING ROOM AND THE FLYING ROOM, IS A SORT OF EXPERIMENTAL THEATRE AIMED AT CHILDREN.

As with Terrapin’s Helena and the Journey Of The Hello, there are ‘Wow!’ moments where I was impressed by very clever devices and nicely thought through ideas. The strong, clear narrative drives everything: Samuel Paxton, a young lad with a lot of energy and imagination, is being somewhat ignored by his grumpy family, so he tackles their grumpiness, and his loneliness, by making a wonderful machine that contains special spaces—the falling room and the flying room. Sam makes his magical creations by ‘fixing’ old junk from the back shed. He’s a curious fellow who exhibits a streak of self-reliance and invention—he might even be an artist in the making.

Eventually Sam moves into the shed with a big screen he can crawl into and literally be on TV—transformed into pixels but still present. This is the digital puppetry terrain Terrapin is investigating—a highly choreographed effect whereby an actor’s arms can reach into a TV screen and be seen on it—like looking at someone reaching into a fish tank, or even climbing into it. Puppets drift in and out of this screen world as well in a deftly executed bit of theatre that excited me. It was pretty clever but, vital to the narrative, never an end in itself. Sam effectively discovers re-contexualisation as a way of of re-making the world and even making it a bit better, at least for him and his dysfunctional family.

In fixing all the broken stuff in the shed—magically making something better rather than simply restoring its former function—Sam repairs his family as well. They all get together and play with his crazy machines. The distant parents recall falling in love, remembering its importance and that doing things together is what a family does. There’s a kind of healing in this play about about human interaction that could be understood in the imagination-ruled world of an eight-year old child and by any adult.

The cast had a lot of work to do: Sam was brought to life by Jeff Michel while Sabrina D’Angelo played all the other characters including the family members and the elf Sabrina who guided Sam about, all the while never speaking or quite being seen by him. More than comic relief—with her silent asides—for a primary school audience, she seemed to me like the boy’s muse.

D’Angelo’s direct communication with the audience and Michel’s wandering into the auditorium reduced the somewhat distant staging at the Theatre Royal. The theatre is by no means cavernous, but The Falling Room and The Flying Room is an intimate show that wants strong contact with the audience to get the magic flowing. Luckily, the show is built to tour 40 schools across Tasmania, so up close is how most children are going to encounter Samuel Paxton, his family, his magic rooms and his sneaky elf pal in their endearing world.

Terrapin Puppet Theatre, The Falling Room and the Flying Room, director Frank Newman, writer Finegan Kruckmeyer, performers Sabrina D’Angelo, Jeff Michel, design Rachel Lang, puppets and props design Greg Methé, sound design, music Fred Showell, video animation Solid Orange, lighting designer Reuben Hopkins; Theatre Royal, Hobart, June 10, 11

RealTime issue #92 Aug-Sept 2009 pg. 44

© Andrew Harper; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Andrew Pandos, Bedroom Dancing, Restless Dance Theatre

photo David Wilson

Andrew Pandos, Bedroom Dancing, Restless Dance Theatre

THE INTIMATE PRIVACY OF THE BEDROOM MAKES IT AN APPEALING—YET SOMEHOW DISARMING, EVEN UNSETTLING—SUBJECT FOR SPECTACLE. THE APPEALS OF EXPOSURE AND INSIGHT ARE GENUINE, BUT THE SENSE OF INTRUSION IS DIFFICULT TO SHAKE. BEDROOM DANCING FROM RESTLESS DANCE THEATRE EXHIBITED THE CONTENTS AND OCCUPANTS OF 15 BEDROOMS IN ADELAIDE’S GUTTED QUEEN’S THEATRE.

In the foyer, a video-installation from Lachlan Tetlow-Stuart invited spectators into bed with the cast. Spectators could snuggle up to a pillow and listen to sweet whispers from a speaker concealed within, while video projections of the performers one-by-one sprawled and rolled their way across the vertically-mounted double mattress. Inside the space, the audience were welcome to walk through and watch as bedroom scenes on adolescent themes were played out.

Evenly dispersed on squares of carpet—like booths in an exhibition hall, the beds were single and, for the most part, solitary. Their occupants were preoccupied with various choreographic tasks. Sleeping—even pretending to sleep—did not figure prominently in the work. Rather, the bedrooms were personal zones of retreat, their occupants engaged in world-making and connecting at a distance, communing with objects and media projections of stylised selves.

The mattresses and bedspreads—those soft, intimate technologies of comfort, warmth and enclosure—were, for the most part, misused and displaced. In one room, the bed itself was upended, the bed clothes spilling out in a twisted mess. In another upset gesture, the mattress became a trampoline in defiant memory of however many times a parent told us not to jump on the bed.

Kyra Kimpton, Bedroom Dancing, Restless Dance Theatre

photo David Wilson

Kyra Kimpton, Bedroom Dancing, Restless Dance Theatre

At an audio installation in the middle of the exhibit, one performer explained that “dancing in the bedroom is not what I usually do.” What distinguished each bedroom were the activities and technologies—some old, some new—of play and escape: a pair of dice, a jigsaw, some toy soldiers, a ukulele, a torch and a book, pencils and paper, travel magazines, a CD player, a radio, a laptop with Skype video-conferencing.

As a piece of dance theatre, Bedroom Dancing was a large-scale assemblage—a collaboration between 15 performers of the Restless Youth Ensemble and an artistic team comprising director Steve Mayhew, choreographer Alison Currie, designer Gaelle Mellis, sound artist Jason Sweeney and lighting designer Ben Shaw. It was also a project for a company in transition, initiated by outgoing artistic director Ingrid Voorendt and staged as incomer Philip Channells took up the role.

Presented as part of Come Out 2009, the Australian arts festival for young people, Bedroom Dancing attracted strong audiences over the course of a week. There were almost too many spectators at the performance I attended. Walking amongst the bedrooms and the crowd entailed an up-close relation of looking down at the performers’ work, which tended to individualise and isolate each bedroom as an exhibit in itself.

Instead of wandering from exhibit to exhibit, I found myself wanting to get down low and look across—to see and sense connections and relations across the array of bedrooms. But opportunities for a wide-angled, zoomed-out focus were difficult to grasp, until, cued by Sweeney’s sound work, the performance climaxed in a communal shudder.

Occasionally during the performance, some dancers visited each other’s bedrooms where they danced together for a while. These were welcome moments because they enacted a desire for contact to cut across the cell-like isolation of the exhibits. Prompted by memories of the adolescent loneliness evoked in this work, I felt a desire for more of these moments of connection across bedrooms.

Contact and connection are the hallmarks of Unreasonable Adults’ successful Gift/Back series. In its latest incarnation as part of Come Out, Unreasonable Adults invited young people to participate in the gift-exchange of supplying raw materials with which the artists make art. The artists called for gifts of a virtual, mediated or actual kind. Kids donated photos, drawings and paintings of themselves and their worlds. They also donated dolls, bears and cartoon characters, popsicle puppets, a clock, a billy cart and a large bag of rice, the names of some colours and some scraps of text. The artists’ undertaking was to use and respond to all they received.

The resulting mix-and-match process yields outcomes both inherently surreal and intimately connected to their audience. As an avant-garde approach to the making of art, the Gift/Back technique seems uncannily suited to a young audience. In creating opportunities for contribution, participation and recognition, it also models an artful ethic of re-use, re-cycling and re-invention which merits emulation.

Julie Vulcan, Jason Sweeney, Kerrin Rowlands, Gift/Back, Unreasonable Adults

photo Sam Oster

Julie Vulcan, Jason Sweeney, Kerrin Rowlands, Gift/Back, Unreasonable Adults

At the performance I attended, the audience sat—cross-legged, of course—on squares of carpet in the Queen Theatre’s second space. We were addressed by the performers directly. The structural clarity of the work—with its step-by-step articulation of segments and an hilarious half-time break for orange slices and odour-ama—revealed an almost educational aptitude for engaging the audience in a process of aesthetic elaboration. I was taken by the work.

The look was colourful and bright. Three performers—Julie Vulcan dressed in orange, Kerrin Rowlands in green and Jason Sweeney in blue—performed a series of meditations on the value of colour in our world. Caroline Daish appeared remotely as an animated face. The set was as vibrant as children’s television. The mood was lively and engaging, the themes just slightly sinister.

Vulcan, addressing the audience in story-book mode, invites us to consider a world in which the colours orange, green and blue are replaced wherever they appear with dismal shades of grey. With excess affect, Rowlands dances in an apple-green negligee with a guitar case, the contents of which remain unrevealed. Intimate on live video, Sweeney tells a stick puppet story of lost children and croons a medley of blue tunes.

The work was intriguing, visually delightful and gently subversive with its imaginative narratives of abnegation and loss. The pleasures for an audience of young adults at the evening performance were apparent. The performers seemed ready to entertain, freshened perhaps by the afternoon performance to an audience of parents and children.

I attended the evening performance so I can’t say how the work played to children. But if I had taken a child or two I would have been grateful for their opportunity to participate in the artful reciprocity of Unreasonable Adult’s Gift/Back.

Come Out 2009: Restless Dance Theatre, Bedroom Dancing, devised and performed by the Restless Youth Ensemble, director Steve Mayhew, choreographer Alison Currie, design Gaelle Mellis, sound Jason Sweeney, lighting Ben Shaw; Queen’s Theatre, May 15-22; Unreasonable Adults, Gift/Back, Caroline Daish, Kerrin Rowlands, Fiona Sprott, Jason Sweeney, Julie Vulcan, Queen’s Theatre, Adelaide, May 29, 30

RealTime issue #92 Aug-Sept 2009 pg. 45

© Jonathan Bollen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

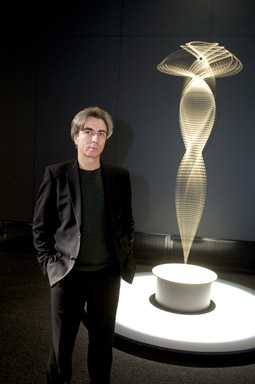

Michael Fowler, Tristram Williams, Act II, LICHT

photo SIAL Sound Studios (Lawrence Harvey)

Michael Fowler, Tristram Williams, Act II, LICHT

IN THE ATRIUM OF SYDNEY CONSERVATORIUM, A FANFARE DESCENDS FROM THE UPPER LEVELS, WELCOMING A MIX OF VISITORS AND AUDIENCES TO THE SMART LIGHT FESTIVAL’S STOCKHAUSEN PROGRAM, A DAY OF LIGHT. THE STARK MELODY, MARKED BY VISCERAL BREATH ACCENTS ON PICCOLO, ACCOMPANIED BY CLARINET AND BARITONE SAXOPHONE IS, HOWEVER, VASTLY DIFFERENT FROM A TRADITIONAL PUNCHY, OPTIMISTIC BRASS FANFARE. WHAT BEGINS IN THE ATRIUM CONTINUES ON IN AN UNRELENTING CYCLE, PUNCTUATED BY LONG SILENCES AND TURNING INTO A MUSICAL JUGGERNAUT, SEEMINGLY UNSTOPPABLE AND ALWAYS UNRESOLVED. THIS IS THE LICHT-RUFT (1995), THE EPIC FANFARE INTRODUCTION TO KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN’S SEVEN-DAY OPERA CYCLE, LICHT (LIGHT).

An hour after it began, the fanfare did indeed prove to be unstoppable, as it continued to play while audiences were ushered into a small recital hall to hear two Stockhausen works performed by Ensemble Offspring. Setz Die Segel Zur Sonne (Set sail for the sun), delicately evolved from a contemplative opening ambience. Part of a series of text-based works titled Aus Den Sieben Tage (From the seven days, 1968), this piece was treated with necessary reverence by the performers. The works comprise vague yet poetic guidelines for improvisation, such as “play a note for so long/ until you hear its individual vibrations” and “…slowly move your tone/ until you arrive at a complete harmony/ and the whole sound turns to gold,/ to pure, gently shimmering fire.”

For a composer often identified as belonging to a European avant-garde known for treating every musical parameter with the utmost precision and detail, in this work Stockhausen demonstrates a fierce creativity and extreme openness in finding new musical terrain. In this rendition, the ensemble interacted through subtle sculpting of dynamics and blending of instrumental colour, resulting in a delicate balance and an ethereal quality, never dominated by an individual player.

Tierkreis (Zodiac, 1975), a series of melodies based on the signs of the Zodiac, represented a vastly different compositional approach, the melodic character a radical departure from the textural and atmospheric nature of the opening work. More traditional in comparison with many of Stockhausen’s works, and characterised by unusual scaleic materials and intervallic harmonies, Tierkreis was at times reminiscent of Stravinsky—sometimes haunting and simple, at other times driving and rhythmically complex.

Originally composed for three music boxes as part of a children’s theatre show, these pieces can be performed for any combination of suitable instruments. Ensemble Offspring’s rendition moved through a colourful array of instrumental combinations and playing techniques. Arranged for clarinets, flutes, percussion, piano, toy piano, accordion, melodica and celeste, this version was never dull as new sounds injected fresh energy into the piece throughout. Perhaps the most poignant moment was provided by the sound of a fragile solo music box, seeming all the more vulnerable when exposed by a single spotlight. There were dramatic elements too that breathed additional life into the performance—Clare Edwardes swinging a cowbell while walking through the space and Jason Noble marching around the stage performing a melody on his clarinet.

The creative interpretation of these works conveyed a sense of daring that seemed to be relished by Ensemble Offspring. This was a beautifully curated concert; the material well balanced and standard chamber music conventions interrogated.

The audience emerges into the Atrium, the LICHT fanfare continues. The juggernaut rolls on and already we sense the prolific, intense output of this composer.

Licht

photo David Clare

Licht

Following Ensemble Offspring, The Song Company performed two works, taking us directly into the world of the opera, LICHT. The six-strong company were joined by six vocal students from the Conservatorium to perform Chor-Spirale, from Fritag aus LICHT (Friday of Light, 1994)—”six hybrid couples conceived as six candle flames unite into a single flame, spiralling up into heaven.” The use of glissandi and hissing added new colours to the conventional pallet of unaccompanied voices, and was executed with utmost precision under the direction of the curator of the Day of Light, Roland Peelman. As the piece evolved a solo bass and soprano moved respectively to the lower and upper extremes of their ranges. Towards the end, silences of increasing length added a new dimension, bringing with it a palpable tension.

From Sieben Lieder Der Tage (The Seven Songs of the Days), the Song Company then performed Montag aus LICHT (Monday from Light, 1986) adapted for six singers and piano. Each singer represented a day of the week and dressed in a corresponding colour. This visual element played out further as the singers, in two rows spread out across the stage, stood dead-pan waiting for their solos, all of which were delivered with dramatic poses or gesturing. Against this stark theatricality, the piano accompaniment—characterised by irregular rhythms and a chromatic spectrum of pitch material—maintained an ambling sense of flow.

The centerpiece of the day’s concerts was Act two from Dienstag aus Licht (Tuesday from LICHT, 1990-91), the Australian premiere of part of the cycle. In a darkened studio the work opened with an ominous electronic score. Drones, various timbres and occasional explosive gestures morphed and blended through an eight channel spatial mix, demonstrating Stockhausen’s remarkable skill in sustaining an homogenous texture over such a long duration. Perhaps this dark sound world is symbolic of the mountainside—the focal point in the story of the second act of Dienstag aus Licht.

Camouflaged by the similar pitch space of the electronic score, the sound of a trombone emerges from the mix and Lucifer, played by trombonist Ben Marks, enters. Moving around the stage, up one aisle, behind the audience, back down the other aisle and onto the stage again, all the while Marks performs fragmented phrases made more palpable by a set of gestures that point the trombone in different directions. The short phrases are punctuated further by occasional use of one of several mutes strapped to the player’s waist. It’s as if Lucifer is attempting to break through the mountain—the vast electronic score that continues to surround us. Although not presented in this modestly staged version, the mountainside is penetrated, revealing a metal wall. During a battle between Lucifer and Michael, played by trumpeter Tristram Williams, the wall disintegrates, revealing solid crystal.

A duet follows between the wounded Michael and Eva (Stockhausen’s variation on the biblical Eve), played by soprano Jess Aszodi. By now the electronic score modulates, allowing a greater depth of interaction between the performers and the score itself. Aszodi manages to successfully project her voice through a still very dense sound to blend with Williams’ trumpet. The unusual musical development of this extended piece was at times interspersed with extended techniques such as tongue clicks, whistling and inhalation sounds on the trumpet and might have been more succesful had Aszodi’s voice been amplified to bring greater clarity to these smaller sounds amidst the electronic wash. Nonetheless, her projection was remarkable under the circumstances. Both players conveyed a powerful stage presence through an extreme economy of physical movement.

The electronic score geared up once more and entered into another extended segue, this time in anticipation of Synthi-fou, a trickster figure who distracts the war-makers. Dressed in a multi-coloured robe and surrounded by a multi-synthesizer set-up, Michael Fowler performed this highly complex and intricate music with remarkable showmanship and ease. With manic laughter, over the top gestures and wide-eyed smiles, the eccentric performance culminated in Fowler standing to count down from 13, waving his hand with each count and slowing as he approached one. Synthi-fou’s broad pallet of sounds seemed to interact with and manipulate the electronic score, blending so well that it was, at times, hard to distinguish their source.

The fanfare, concerts, semi-staged opera extract and other events in Day of Light at the Con amply and admirably demonstrated over more than eight hours the epic nature of Stockhausen’s vision. Often the sheer duration of his works conveyed a force almost sufficient to intimidate even a curious and willing audience. As Andrew Ford remarked in his introduction to Ensemble Offspring’s program, Stockhausen’s creativity, now enjoying fresh recognition, was truly fierce and at his death in 2007, we lost a composer like no other.

Smart Light Sydney & Sydney Conservatorium of Music, A Day of Light at the Con, curator Roland Peelman, part of the Vivid Sydney Festival of Music, Light & Ideas, Sydney Conservatorium, June 6

RealTime issue #92 Aug-Sept 2009 pg. 46

Plump, LA10 Sydney

photo Kazumichi Grime

Plump, LA10 Sydney

IT WAS SYDNEY LAPTOPPER ALEX WHITE WHO KICKED OFF THE FIRST CONCERT OF THE LIQUID ARCHITECTURE 10 PROGRAM AT CARRIAGEWORKS. HIS ARCHITECTURAL IMAGES WERE BUILT IN THE LISTENING SPACE FROM WHITE NOISE THAT ARRIVED, DISAPPEARED AND ACCUMULATED. IT WAS HARD TO LISTEN TO AT FIRST UNTIL HEARING ADJUSTED TO THE EMERGING SUBTLETIES WITHIN MULTIPLE SOUND-PIPES AND PULSES CROSSING TRAJECTORIES AND CAUSING A RUCKUS. VOLUME LEVELS WERE NOT HIGH BUT MY AUDITORY MEMBRANE STILL OSCILLATED WILDLY TO MAKE SENSE.

Surprisingly White had a couple of walk-outs but the work following him had most of us reaching for the ear plugs (supplied at the door) as West Australian musician Cat Hope alternately attacked and lulled the listener. Ear plugs were, however, no defence against an atmosphere pressurised and made tactile by imperceptibly low frequencies arising mysteriously from somewhere in the auditorium. Attuned perhaps to the ghosts of the funeral march Hope was interpreting, the body vibrated, depending on the particular frequencies she produced. These deep resonances were a long way from the silence notated (bars and staves only) by 19th century Chat Noir activist Alphonso Allais who inspired the work. He was long gone yet only traces of Hope’s physical presence were evident. Her apparition flickered across the video screen in indecipherably low-lit, live-feed images gradually providing clues to the nature of her concealment below the seating grid.

I found out later that we were hearing Hope’s bass guitar mediated by an array of effects and sub-woofer speakers. It was played variously by collisions with the seating superstructure or by simply coaxing sound out of it by more or less hitting parts of the instrument. This music was moving but not for the faint-hearted and many punters ran for it. The architecture felt the stress too with shockingly high pitched screams triggered in the lighting rig and mid-range metallic groans and murmurs vibrating in the seating structures. This Cat was playing the room, co-opting the building into her program and providing the most challenging work in this year’s Sydney concerts.

A little easier on the body was Bradbury. The image of a wax light was projected as beautiful bell sounds began the first of about nine pieces. Bradbury has a unique, recognizable style favouring short pieces and often re-moulding material into beats or reconfiguring field recordings into new contexts. One piece mixed a Jimmy Saville style TV shopping salesman and flat piano tones with delay drenched loops transforming from humour into a poignant statement about commercialism.

The clarity of Bradbury’s video projection was replaced for Thomas Köner’s piece by more obscured objects. It would take Imax technology for Koner’s projected images to successfully match up to the enormous spectrum of sound he created. The looped vision of a metro train journey and various ghostly humans superimposed onto similarly smeared locations became a puzzling distraction from the immersive engagement of his sound world. I greatly enjoyed the intriguing aestheticisation of the everyday via the overheard but indistinct human voices set amidst grand, airborne sonic gestures. At one point a passing jet seemed to have entered the space even though the expected decay of its passing was never realised.

Köner’s approach shared some aesthetic points with Asmus Tietchens who closed the Saturday concert. Tietchens as one of the innovators of electronic music in Germany has had an enormous influence on the form since the 1970s. He created a wonderland of sound, layering frequencies in a concerto supported by a riveting bottom end through to high-pitched ringing with occasional bursts from every register in between. Machinistic throbs were sunk into hypnotic ground and opposed by sudden fanfares which were then subsumed into the underlying pulses. The composition was very finely crafted, working with rhythmic oscillations and many unidentifiable and peculiar creations constantly reconstituted by Tietchens’ settings. Attention to detail was as delicate as the harpist’s stroke, one of the transitions dropping down into an almost inaudible range.

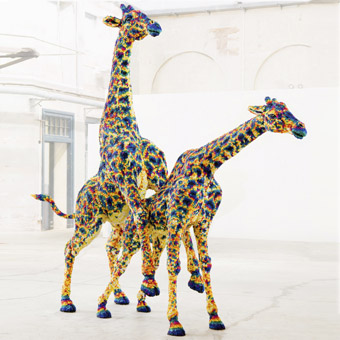

Unlike Tietchens and his colleagues of the men-at-tables ilk, Plump explored the sound qualities of a sculptural installation they had constructed over the five hours preceding Saturday night’s concert. It took up most of the performance area of the theatre. They played a surprisingly restrained set considering the scale of the instrument—a series of angular but asymmetrical suspensions of cable and scaffold-like aluminum. All this was complemented by a dozen or so randomly placed, mis-shapen light shades about the size of physio balls. Marc Rogerson controlled these from upstage by using hand-held arcing low-voltage contacts across a live power board. Philip Samartzis began with soft cricket whispers yielding eventually to many clangs and cries from Dave Brown’s bowing and tapping. Ringing, cello-like laments combined with electronic interpretations of sounds picked up from various contact points around the structure and processed by Samartzis. We could have been witnessing the capture of the musician by some terrible arachno-robotic figure as Brown provoked and stroked the beast variously by hammer and bow to produce ‘architectural’ music par excellence.

Opening the Saturday night concert alongside the imposing Plump sculpture, Somaya Langley was a diminutive figure in her suit of triggers and hanging projection surfaces. Her piece was, however, underwritten by some big ideas and the modulated swoosh and crash of her limbic sound-triggering produced some tasty sonic onomatopoeia.

Whirlpool (Chris Abrahams playing pedal harmonium and Kraig Grady on prepared vibraphone) followed Plump after the interval looking more austere but drawing from an enormous tonal pallette. Once acoustics had been contained by the ‘curtaining’ of the perimeter walls, the ringing began. Grady had repositioned the vibes’ metal bars unconventionally to create beautiful dissonances, enthralling beats and strange harmonies. They cut across and embedded themselves into the drones provided by Abrahams and it was hard to believe at times that they were both completely acoustic. Some of their discords struck disturbing resonances even in (or perhaps because of) the cavernous spaces of CarriageWorks. The piece was like an amalgam of gamelan with early Moog music as Abrahams demonstrated his penchant for extracting sonic modernity from pre-electronic keyboards.

Marc Gunderson, LA10 Sydney

photo Kazumichi Grime

Marc Gunderson, LA10 Sydney

As compere Brent Clough noted, we were “sopping wet with sound” after these two concerts so it was hard to muster enthusiasm for DJ-driven music. But the 10th anniversary after-party at Hermann’s Bar (complete with a profiterole stack) also contained some unexpectedly exciting sound art. Best of these for me was Buttress O’Kneel (sic) who intervened with marvellous invention into some well-known pop using effects pedals to alter musical states in extreme ways. As ‘his’ androgynous mask and wig messed with our minds, his mix attacked Stairway to Heaven, the themes from Skippy and Sesame St not to mention the Australian national anthem—no cow was too sacred for deconstruction. This work would have easily fitted into the concert context—extraordinary found-sound noise art.