January 2010

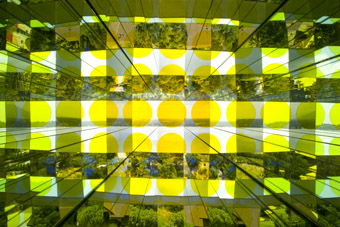

One-way colour tunnel 2007, Olafur Eliasson; Collection of the Art Supporting Foundation to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

photo Ian Reeves Photography

One-way colour tunnel 2007, Olafur Eliasson; Collection of the Art Supporting Foundation to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

WHEN MASSES OF LONDON GALLERY-GOERS BEGAN TO SPONTANEOUSLY SUNBATHE ON THE FLOOR OF THE TATE MODERN UNDER THE HAZY GLOW OF OLAFUR ELIASSON’S ARTIFICIAL SUN FOR THE WEATHER PROJECT IN 2003, THE ARTIST’S INSTALLATION CAPTURED HEADLINES WORLDWIDE. SEVERAL YEARS LATER ELIASSON CONTINUES TO PROVOKE WITH EXPERIMENTS INTO SPACE, LIGHT, NATURAL PHENOMENA AND VISUAL PERCEPTION THAT HAVE ESTABLISHED HIM AT THE VERY FOREFRONT OF CONTEMPORARY ARTMAKING.

This year’s Sydney Festival sees the inclusion of both a large survey of the Danish-born Eliasson’s work, Take Your Time, along with a trilogy of immersive video installations by one of Australia’s most prominent new media artists, Lynette Wallworth, as major components of its visual arts program. Take Your Time, showing at the MCA in Sydney until April 11, first opened at the San Francisco MOMA in 2007 then toured a number of museums in the US where its range of spectacular experiential installations generated a buzz among gallery visitors. Wallworth’s videos carry similarly impressive credentials, exhibited previously to much acclaim both within Australia and at a number of prestigious international festivals, and appearing at the Sydney Festival as a trilogy for the first time.

Sunset kaleidoscope 2005, Olafur Eliasson

photo Fredrik Nilsen

Sunset kaleidoscope 2005, Olafur Eliasson

That two artists so greatly concerned with rewiring the relations between viewer, artwork and the world around us should share top billing is a sign of the times, as a growing number of artists shift their emphasis from the art object to experience and process. Where Eliasson has arguably most effectively differentiated himself is in his refusal to shy away from either visual seduction or spectacle in the exploration of his more abstruse concerns. Whether it’s the creation of shared viewing experiences that overturn the traditional notion of contemplation as inherently solitary, or visual thought experiments that return the viewer to an awareness of his or her own perceptual faculties (“seeing yourself seeing” as the artist puts it), these works reveal beauty and awe as tools to be exploited rather than enemies to be resisted.

360° room for all colours, 2002, Olafur Eliasson

photo courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

360° room for all colours, 2002, Olafur Eliasson

Speaking with Adam Jasper for Sydney Ideas Quarterly in the lead up to the exhibition’s launch, Eliasson pointed out that “art-historically speaking, we stand on the shoulders of generations for whom looking at art was considered such an intimate act that having somebody else in the space would compromise the experience.” In Take Your Time, enclosed spaces refute this tradition by bringing viewers physically closer to one another while, as the mechanics of the works are often made visible, visitors are stimulated to interrogate how the magic is realised. From a fluorescent lit spherical room that places visitors within the colour spectrum (360° room for all colours, 2002) to a darkened, cave-like space in which visitors are drawn toward a mesmerising artificial waterfall (Beauty, 1993), these spaces generate discussion more aligned with the logic of scientific analysis than aesthetic appreciation.

Wandering through this labyrinth of special effects, however, a niggling concern arises that, beyond the initial shift in perception these installations facilitate, there may be limited scope for deeper interpretation. Following this line of thought, suddenly Eliasson’s approach becomes slightly unnerving. Completely a-historical, mainly non-representational, and largely without objects, this is artmaking with all the points on the compass wiped clean. Ultimately, though, this may be an idealistic strategy on Eliasson’s part, one in which art takes place in the present moment liberating the viewer from the encumbering expectations of transcendence, and its accompanying anguishes, handed down from history. And while the artist has insisted “it’s not about utopia or anything final,” it is from this perspective that the works seem most affecting. A quiet plea emerges to use one’s senses, however conditional their production of reality might be, to appreciate nature simply as it is, rather than treating it as a canvas for the projection of our feelings, anxieties and the desire to transform it into something of our own making.

Invisible by Night, 2004, Lynette Wallworth

photo Colin Davison

Invisible by Night, 2004, Lynette Wallworth

Over at CarriageWorks in Redfern, the exhibition of Lynette Wallworth’s trilogy of immersive video installations follows the first major survey of the artist’s work staged at Adelaide’s Samstag Museum in early 2009, which also coincided with the debut of Duality of Light, a groundbreaking moving image artwork commissioned by the Adelaide Film Festival. Like Eliasson’s installations, this trilogy of intimate videos reveal Wallworth’s concern to place the viewer at the centre of the work but, in marked contrast, her approach is very much anchored in the specifics of history, place, identity and personal stories.

In the earliest work presented, Invisible by Night (2004), a life-sized woman appears trapped behind a misty screen and is beckoned to greet the viewer when the video is activated by a touch sensor. This uncanny encounter with a grief-stricken figure represents the artist’s melancholic and empathic response to the site of Melbourne’s first morgue. In a later work, Evolution of Fearlessness (2006), the same touch activation technique is used but here the idea is extended with the portrayal of 11 women, again in life-sized portraits. Some are refugees who have relocated to Australia from various corners of the globe and each has suffered violent persecution. The women’s harrowing true stories of survival are documented in an accompanying text.

In Wallworth’s videos the haptic dimension of the touch screen is not simply about engaging the senses as a challenge to the essentially non-tactile character of the cinematic medium. Rather, it belongs to a larger concern to use gesture, here the simple act of two hands meeting, to engender compassion and expose the viewer to meeting a stranger’s gaze at close proximity—a subversive act in a culture which conditions us to look away. Touch is not harnessed in the final installation, Duality of Light (2009), but again the notion of encounter is significant. In this instance it takes on a more mystical dimension. Immersing the visitor in the sounds of dripping water the installation brings to mind the emotive video works of Bill Viola where water signifies near religious journeys of birth and rebirth. Although here the subterranean sound of water hitting limestone, captured in a cave in Auckland by noted sound artist Chris Watson, leads into deeper recesses of memory becoming, as Wallworth describes it, like “an echo of time.”

Duality of Light, 2009, Lynette Wallworth

photo Grant Hancock

Duality of Light, 2009, Lynette Wallworth

So Wallworth, too, brings the experience back to the viewer with interactive video installations that issue a challenge to feel, to empathise and to relate, that runs counter to an entertainment culture that often demands little more than to sit back and enjoy. Eliasson offers similar challenges in differing ways, yet neither artist denies the audience pleasurable viewing experiences. In fact, the very opposite is true. Heed their advice to look more closely about you and on the faces of fellow visitors at both exhibitions you will find expressions of wonder, surprise and delight.

–

Olafur Eliasson, Take Your Time, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Dec 10 2009-April 11 2010; Lynette Wallworth, Invisible by Night, Evolution of Fearlessness & Duality of Light, Carriageworks Sydney, Jan 7-24 2010

RealTime issue #95 Feb-March 2010

Shangoul-o-Mangoul, 1999, Farkhondeh Torabi

IN HARUTYUN KHACHATRYAN’S RETURN OF THE POET (2006), WE FOLLOW THE TRANSIT OF A MASSIVE SCULPTURE OF LATE 19TH-CENTURY ARMENIAN POET AND PHILOSOPHER JIVANY FROM YEREVAN, THE CAPITAL OF ARMENIA, TO JAVAKHK, JINVANY’S BIRTHPLACE. IN MANY WAYS, THE FILM’S TRACING OF THIS SLIGHTLY SURREAL JOURNEY, WITH NUMEROUS UNEXPECTED OBSTACLES AND DELIGHTS ALONG THE WAY, SYMBOLISES THE EXPERIENCE OF THE APT6 CINEMA PROGRAM.

The Australian Cinematheque established the expectation that major art shows should be accompanied by film screenings with its maiden outing at the fifth Asia Pacific Triennial in 2006. Now, with nine programs comprising over 100 films, documentaries and animations, the Cinematheque for the sixth incarnation of the APT cements its reputation for insightful, far-ranging programming.

Z32, 2008, Avi Mograbi

image courtesy Doc&Film International

Z32, 2008, Avi Mograbi

The sixth broadened this juggernaut’s ambit to include not just Central Asia, but the Middle East as well. This move is reflected strongly in the film program, which essentially eschews the more familiar cinemas of Japan, China, Korea and Hong Kong for those further west with two major programs, Promised Lands and The Cypress and the Crow: 50 Years of Iranian Animation. South-East Asian arthouse cinema isn’t entirely absent; three auteurs are profiled with retrospective seasons during the exhibition of APT6. Of these, Takeshi Kitano (Japan) and Ang Lee (Taiwan/USA) are unusually well-exposed choices for such an adventurous program but the third, Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh, offers a challenging counterbalance. Panh, whose work includes documentary and dramatic filmmaking, as well as cultural conservation endeavours in Phnom Penh, deserves this sustained attention and the Cinematheque congratulations for bringing him to light.

_2008.jpg)

Un barrage contre le pacifique (the sea wall), 2008, Rithy Panh

Threaded throughout the APT6 season, The Cypress and the Crow program highlights the richly textured history of animation practice in Iran. The vast cultural achievements of Iran’s Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (known as Kanoon) include well-known alumni such as Abbas Kiarostami, but its animation work has until now escaped wider attention. The Cypress and the Crow flings open the door prised ajar by 2007’s Persepolis (included in this program), leading audiences on an exhaustive journey through the Iranian animated tradition. Revered veteran director Noureddin Zarrinkelk is well represented, with a choice selection of gorgeous 1970s and 80s animations, as well as a more recent work, 1998’s Persian Carpet.

Iran’s history of textile design recurs in various forms across the program. It is however most evident in the four-screens installation in the gallery on Level 1, in the main APT artists’ section with the works by Farkhondeh Torabi and Morteza Ahadi. A striking still image from one of these, Ahadi’s exquisite, self-reflexive 35mm animation, The Sparrow and the Boll (2007), emblazons the print program, though it’s a shame it was only screened once in its proper black-box glory, amidst all the colourful chaos of the opening weekend celebrations. On the other hand, the installation of these gorgeous hand-made works amongst all the other artworks confers numerous benefits, not least the multiplication of eyeballs in the form of the thousands of visitors who visit over the APT’s four months.

Promised Lands is divided thematically and geographically into five autonomous curatorial categories, including Cinema of Partition, which examines Bangladesh, India, Kashmir and Pakistan, and The Tree of Life, looking at Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq and Kurdistan, both of which run concurrently throughout the APT6 season.

_2002.jpg)

Yadon Ilaheyya (Divine Intervention), 2002, Ella Suleiman

Though the slimmest, the Sri Lankan set, The Road to Jaffna (Feb 4-14), is among the most vital of the programs, offering a rare glimpse of the conditions of civil war on the island. Two other shorter programs, Return of the Poet, focused on the cinema of Armenia and Turkey, and Eating my Heart, looking at Lebanon, Israel and Palestine, contain some of the most lyrical and moving work of the entire program. Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman cuts a Keaton-esque figure with his deadpan appearances in front of the lens, repetition of bizarre sight gags and a pervasively wistful sensibility. Suleiman’s “occupied imagination” comes powerfully to the fore in 2009’s The Time That Remains, and especially 2002’s Divine Intervention, where the comic and the tragic, the humiliating and the absurd, and the fantastic and the banal uncomfortably co-exist.

In Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari’s How I Love You (2001), gay men talk about their feelings to do with their own and other men’s bodies. However, speaking from a place where homosexuality is punishable with a jail sentence, Zaaatari’s subjects’ faces are over-exposed, or blurred by a filmy white veil. As they discuss, among other things, gender roles in relationships, the viewer gains access to a host of complex sexual and personal realities normally totally hidden from view. Many of Parvez Sharma’s interviewees in A Jihad For Love (2007) are also veiled, for obvious reasons: through a series of sophisticated interviews, the film explores whether or not the idea of spiritual struggle can be reclaimed to reflect the internal struggle of those who find themselves gay in a near universally hostile world. The documentary urge also runs through the memorable Armenian program. As well as Harutyun Khachatryan, the series also offered a rare chance to experience the work of the incredible filmmaker and theorist Artavazd Pelechian, whose idea of “spiritual” or “intuitive” montage has contributed to his international cult-director status, and whose shorts program mobilised a small army of art/film lovers at APT6.

_1969.jpg)

Meng (We), 1969, Artavazd Pelechian

Coming on the heels of the program immediately prior to the APT6, the View From Elsewhere (2009), which also examined Western and Central Asia and the Middle East, Promised Lands and the Cypress and the Crow develop our cinematic understanding of these regions of the globe in thoughtful selections reflecting the Cinematheque’s sensitive and intuitive approach to programming. Mapping, as it does, cinematic expression across some of the world’s most fractious, troubled zones, it is perhaps not surprising that some of this fragmentation and volatility has crept into the print program advising audiences of what they will encounter at the Cinematheque: the absence of a single day-by-day calendar was felt. This notwithstanding, the APT6 cinema program provided an enormous wealth of ideas, as well as viewing pleasure, for an increasingly grateful Brisbane audience. It is through exposure to these ideas, sounds, images and experiences that we reach greater understandings of our place in the region, and the world, and of those we share it with; in Pelechian’s words, that we are “a ‘we’ that is just a piece of the larger ‘We’.”

APT6 Cinema Program, curators Kathryn Weir, Jose da Silva, Australian Cinematheque, Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane Dec 5, 2009-April 5, 2010

http://qag.qld.gov.au/cinematheque/current_programs/apt6_cinema/promised_lands

RealTime issue #95 Feb-March 2010 pg.

The Fence, Urban Theatre Projects

photo by Heidrun Löhr

The Fence, Urban Theatre Projects

In 2011, Urban Theatre Projects will be 30 years old. It is a feat of incredible resilience, which itself is an enduring theme of their work. In 1981, Kim Spinks, Paul Brown and Christine Sammers founded Death Defying Theatre. Ten years later, artistic director Fiona Winning (1991-95) relocated the company from Bondi to Auburn and then to Casula. In 1997 John Baylis (1997-2001) took over the reins. The company changed its name and moved to Bankstown in 2001, where it is still based. This archive focuses on UTP’s more recent history, documenting the era associated with artistic director Alicia Talbot (2001 onwards), rather than her predecessors (whom we will cover when our archive is completed back to 1994. Eds).

There are three discernable strands to Urban Theatre Projects’ work over the past decade. First, there is Talbot’s body of work as a director—Cement Garage (2000), The Longest Night (2002), Back Home (2006), The Last Highway (2008) and most recently The Fence (2010). Sitting alongside this corpus is the more spectacular work UTP has developed with collaborators, for instance Mechanix (2003) with designer Joey Ruigrok van der Werven, Karaoke Dreams (2004) with Katia Molino, and Plaza Real (2004) with Branch Nebula, as well as india@oz.sangam (2002) with the Western Sydney Indian community. Finally, there are the performances produced by solo and/or emerging artists whom UTP has mentored, auspiced, or generally supported in some way. These include the intimate performances of Brian Fuata in Fa’afafine (2002), Valerie Berry in The Folding Wife (2007) and Ahilan Ratnamohan in The Football Diaries (2009), as well as the performed oral histories Fast Cars and Tractor Engines (2005) and Stories of Love and Hate (2008), directed and devised by Roslyn Oades.

Of course the distinctions are not as clear-cut as this and these threads overlap, braid together, and sometimes tangle. Though Talbot cautions against seeing “aesthetic cohesion” where there is none, together the artists involved in these projects have examined the politics and poetics of resilience. Time and time again, Urban Theatre Projects has explored who becomes marginalised, how and why; but rather than talking about marginalised subjects, UTP prefer to talk with them through community consultations, running workshops and mentoring emerging artists. More importantly, UTP enables people to speak not only about their lives, but also about life more generally—as one collaborator remarked, “my social and political opinions and ideas about the world.” Through their many productions we have come to know many modes of resilience: modest, contingent, defiant, temporary, permanent and sometimes triumphant, but rarely in the way we expect.

The irony of pioneering an aesthetics of resilience through theatre is that it’s the least ‘resilient’ art of all, which is where this RealTime archive comes in. It’s a focused collection of our best profiles, images, interviews and reviews. They might prompt your memory if you were there or jealousy if you weren’t, but above all else they will make you think—as Urban Theatre Projects does—about how the world works within theatre and theatre works in the world.

Caroline Wake

reviews

innocents retrieved

david williams: the fence

game: life and art

caroline wake: the football diaries

learning to listen

caroline wake: stories of love and hate

roads to despair

bryoni trezise: the last highway

one woman in many: survival and resilience

jan cornall: the folding wife

urban theatre projects

jo litson: UTP then, now and next

journey into the unexpected

bryoni trezise: back home

all in the re-telling

david williams: fast cars and tractor engines

to shop, to die (for)

keith gallasch

the fun of fakery

bryoni trezise: karaoke dreams

towers of power

keith gallasch: mechanix

the winner: urban theatre projects

realtime: the myer awards, melbourne

on the cross-cultural beach

margaret bradley: girl by the sea

escape route

jeremy eccles: the longest night

a nice, nasty night out

will rollins: fa’fafines