Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

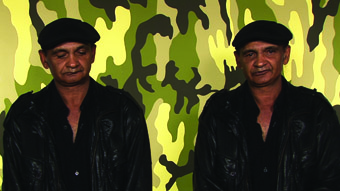

Clare Britton, Matt Prest, Hole in the Wall

image Clare Britton, Matt Prest, James Brown

Clare Britton, Matt Prest, Hole in the Wall

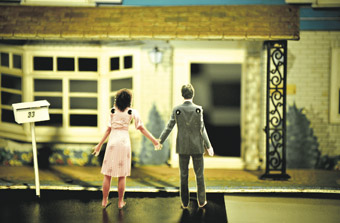

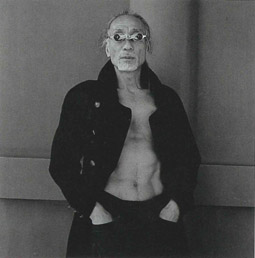

SYDNEY PERFORMANCE MAKERS MATT PREST AND CLARE BRITTON’S NEW WORK IS HOLE IN THE WALL, DESCRIBED IN A PRESS RELEASE AS “A CONTEMPORARY LOVE ADVENTURE…A HIGHLY VISUAL AND EXPERIENTIAL THEATRE WORK THAT EXAMINES SPACE AND POPULAR NOTIONS OF HOME, BEAUTY, LOVE AND DESTRUCTION.” I SPOKE WITH PREST ABOUT HOW THESE LARGE THEMES WOULD BE REALISED AND IN WHAT WAY THE WORK WOULD BE “EXPERIENTIAL.”

These days, in contemporary performance and live art, “experiential” suggests that an audience will be more than engaged onlookers, becoming an actively creative component in the making of a show. In his report on the 2010 PuSh International Performing Arts Festival in Vancouver (p2), Alex Ferguson describes a swathe of productions in that festival engaging intimately with audiences: “The role of the spectator has been shifted from decipherer-of-meaning to co-creator of the theatrical event. Another way to put it is to say that interpretation has been subordinated to encounter, and that it is in the energy of the encounter that meaning is created, rather than having meaning encoded in the event beforehand by the artist.” Increasingly artists ask their audiences to follow rules, solve problems or make art, while others offer immmersive experiences that require willing physical submission, like enduring sensory deprivation. Of course, there is a long history of works that have mobilised audiences to create their effect (including, memorably, those of Sydney’s Gravity Feed) but the current moment is seeing such approaches multiply and rapidly diversify.

Prest explains that Hole in the Wall is “a continuation of The Tent”, his previous work, in which “the tent provided a focus for the audience experience.” The audience entered, sipped soup and absorbed a laterally-told tale, with puppets and film, about a curious male relationship. The Tent fused an engaging low-key realism with theatrical magic yielding a strange otherworldliness—a hint of the metaphysical. It appeared at the Next Wave Festival and Performance Space’s LiveWorks in 2008 and, fortuitously as you’ll see, in 2009 at Campbelltown Arts Centre.

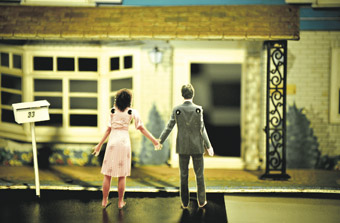

For Hole in the Wall, Prest tells me, the artists have built “four rooms—four large boxes, domestic in feel, with loud wallpaper and trimmings like skirting boards. They’re stiflingly domestic but without clear function. They could be a bedroom, a study or a cupboard, but there’s no furniture.” Each room will house nine members of the audience, viewing the performance happening outside through a window or a wall that opens out. The rooms are on wheels, are moved by the audience and can become two rooms or one as they join up and Hole in the Wall, says Prest, then becomes “more about an overarching space. Each disorienting move reveals and reframes fragments in a suburban love story.” From within these rooms, through windows or open walls, the audience witness “the psychological, emotional world of a couple seeking the beauty of perfection—the home which will be everything they want—and the destructiveness in the lengths they might go to get there.”

Although drawing on the lives of Prest and Britton as a couple, the work is not autobiographical: “it’s more than ourselves,” says Prest, “but the tricky themes are pertinent to us.” Although there is text (written by Halcyon Mcleod, one of Britton’s partners in the performance group My Darling Patricia)—”monologues, dialogue, scenes”—Prest sees the emphasis in the show as being on the physical and the visual. “Physical as in presence: the delicacy with which the performer enters the space and negotiates with the audience.” He explains that much of the show has been developed on the floor, working with Melbourne-based director Hallie Shellam. Also involved in the show are multidisciplinary visual artist Danny Egger and sound designer and composer James Brown who is also working with Prest and Britton on the animated film which will be part of Hole in the Wall—”a puppet couple in naive looking stop-motion influenced by [Czech animator] Jan Svankmajer.”

Prest pays tribute to Campbelltown Arts Centre for its investment in Hole in the Wall (after it had hosted The Tent) with a four-week residency when the show was just an idea, at which early stage no government funding body would likely support it. Then Campbelltown Arts Centre, Performance Space and Next Wave Festival 2010 joined forces to co-commission Hole in the Wall with the financial assistance of an Opportunities for Young and Emerging Artists (OYEA) Initiative grant from the Australia Council. This means that Hole in the Wall will appear successively at Campbelltown Arts Centre, Next Wave 2010 in Melbourne, and Performance Space at CarriageWorks in Sydney, a wonderful opportunity for a new venture, not least one based on an intriguing performative and thematic premise.

Matt Prest, Clare Britton and collaborators, Hole in the Wall, Campbelltown Arts Centre, April 22-24, school performances April 21, 23; www.campbelltown.nsw.gov.au; Next Wave 2010, dates TBA, http://inside.nextwave.org.au; Performance Space, CarriageWorks, Sydney, May 26-29, http://performancespace.com.au

Originally published in the March 29, 2010 online edition.

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. 34

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

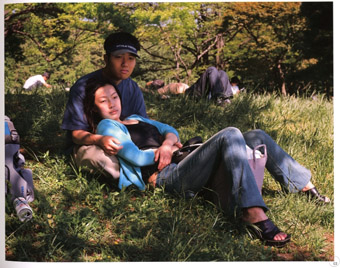

Love Me Tender, Thin Ice Productions

photo Jon Green

Love Me Tender, Thin Ice Productions

In a fascinating exercise in theatrical narration and with near agitprop urgency, Tom Holloway’s Love Me Tender directly addresses the contemporary rift in family intimacy wrought by two forces: the premature transformation of girls into women and the fear of sexually abusive fathers.

The play is inspired by, but is not an adaptation of, Euripides’ Iphigenia in Aulis (408-6 BC). Pressured by an army approaching murderous revolt, Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, sacrifices his daughter so that the gods will provide the winds to drive his stilled fleet to Troy to retrieve the abducted Helen, wife of his brother Menelaus. Euripides’ enduring account is complexly tragic, played out in a field of constantly shifting motives and loyalties. The playwright’s achievement lies in revealing that however much the gods can be invoked to rationalise human actions, the choices made are actually less clearly motivated—they are personal, social and, not least, political—and often not reliable—even Iphigenia changes her mind, ‘heroically’ (as it is often put) accepting her father’s will and going to her death. Filial love is brutally compromised by political pragmatism—Agamemnon still loves his daughter, but not enough to let her live and put at risk his power and the lives of the rest of his family.

In Holloway’s play, the setting is abstractly contemporary—a raised green pentagonal lawn bordered by a low perspex fence has something of the feel of a vividly illuminated specimen case into which we peer, watching what soon appears to be a nasty experiment. In this laboratory a man (Colin Moody) struggles to tell, or to invent, his story, prompted, cajoled and corrected by a chorus-like male (Arky Michael) and female (Kris McQuade) pair. The constant pressure and rapid alternations in the dialogue heighten a sense of improvisation apt for an experiment in which a man conjures a ‘what if?’ world where a father might sacrifice his daughter for the greater good of the community.

The language, as usual with Holloway, is sharply observed everyday Australian frequently delivered in staccato one line utterances, outbursts and interruptions yielding a constant sense of uncertainty, interrogation and of thinking aloud that is nonetheless cumulatively fluent and poetic in its repetitions and reworkings—if requiring an alert audience ear. But it’s more than a matter of style: Holloway’s language reveals from the play’s very beginning that the world we are observing is a socially and imaginatively constructed one and, initially chronologically ambiguous. The diction of the man and his prompters suggests the world of Homer or Virgil (“the sun hits the dust in the air…like pillars of fine, floating flakes of snow…they are ripped apart into…into…Chaos?). The trio’s narrative accelerates: the man rushes home to find another between his wife’s legs—jealousy and anger threaten—but it’s a doctor delivering their daughter. Even so, ambiguity persists: “Her fur and hooves. Now I see her hooves. Wet with placenta and blood.” The sense of a mythic world—with the line between man and animal blurred—is suddenly amplified. Uncertain of his feelings—love? joy?—the man arrives, with prompting, at a state where he experiences “amazing and yet terrible flashes of what is to come and suddenly I am filled with an immense and overwhelming sense of love and horror.” In a matter of minutes the play’s dynamic (of a world being invented) and its layering of the epic and the domestic, of human and animal, and of an event foretold, but not revealed, are immersively at work.

A burst of celebratory optimism—”I think it is the best time to bring a little girl into the world”—details the many opportunities for women these days (run marathons, banks, corporations, visit a strip club, “sacrifice herself for…some great cause”). But it’s immediately subverted by a list of threats to young girls that requires their protection—”It’s almost impossible to keep your children safe these days.” “It’s scary.” “Yes.” “What might be done to them.” “Yes.” “To their little bodies.” “Their hooves. Their fur.” But ambivalence creeps in: “…they taste so good.” “They are succulent like nothing else.” “They get them fresh. Straight from the parks and homes and churches and schools and straight onto the plate for us.” In Matthew Lutton’s production this dialogue is delivered by the man and the male prompter (the printed script does not specify who says what, leaving it a directorial choice), making the inference of co-existing and conflicting male desires unavoidable.

The next dialogue between the two men, where the father expresses pleasure in playing with his daughter and his attempt to understand what it is that passes between them, is undercut respectively by the prompter’s suspicions of sexual interference and his incomprehension of what the father sees as the spiritual nature of the relationship. The prompter is limited strictly to “Right,” “Sure”, “What”, but Arky Michael wrings every shade of suggestiveness and concern from them until the father erupts: “Everyone’s first thought goes to dad teaches daughter how to fuck and suck because that…all that…that is what they know.”

Love Me Tender, Thin Ice Productions

photo Jon Green

Love Me Tender, Thin Ice Productions

Subsequently, the man waters the lawn with a sprinkler. Amidst the spray, his wife (Belinda McClory) dances at a party to a chorus of cries directed at young girls: “Don’t forget your cut-off top!” “Got to show that cute little midriff!” “Are your g-strings showing?” The dance is increasingly and convulsively erotic until the wife collapses before her distant husband. She then becomes a pathetic figure, watching helplessly from the sidelines. She’s certainly no Clytemnestra, the dance suggesting she is complicit in the sexualisation of her daughter.

Having more than firmly established the doting father’s anxieties, Holloway now addresses the man’s public role; he’s a fire fighter chief whose wife wonders why “he has disappeared so much?” “Like he wants to confess some kind of thoughts to me.” “I can’t help but feel that something bad is going to come of all this.” Brief monologues are scattered between the dialogues, some delivered by a Chorus (played as a policeman here by Luke Hewitt), describing a fire-ruined landscape, a destroyed home, a lost girl, or is it an animal (“The ash stains her fur.”) This is the otherworld the father and the policeman occupy. As the fire mounts, the family gather with refugees at a swimming pool. The girl (now “ten-eleven twelve”) is there with “a boy that is a friend.” The father “[i]s standing there…knowing full well that there was nothing at the pool for them. Nothing but the anger of the gods.” He is anxious about “Not being off where his community needs him”, but what fills his mind and pours from his and the prompters’ mouths is a long, tirading litany of all the fears in him that his daughter’s almost pubescent body in a “tight little bikini” elicits—teen dance troupes, increasingly early physical maturation, a daughter catching a father cock-in-hand watching porn, predators at the pool, boy or boyfriend? “And suddenly he wants to let the fire burn!…to burn out all the psychos and freaks and degenerates because the world is fucked!”

Again, this is teamwork, urged on by the man’s prompters. He asks, “Is that about right?” They reply, “Absolutely.” He then feels compelled to sacrifice his daughter. A live lamb, representing the daughter, is brought on stage. The policeman demonstrates elaborately how to cut its throat. The wife, wet, quivering, sobbing, watches from the side. The father exits with the lamb. The policeman recites his own tale of shooting of wounded deer during the fire. The father returns, bloodied from the sacrifice to recount the death of his daughter in more literal terms: cries on the radio from the community for help had drowned out the screams of his daughter trapped in “the car he bought her so she could learn to drive.” He cannot or rather will not save her, watches her die, turning instead to the community “[w]here he needs to be a hero”, but crumbles into the chaos prefigured at the play’s opening. In this penultimate scene Colin Moody allows the father louder passion and pain than previously: perhaps they might have conveyed more if delivered quietly. The play ends with the sadly fatalistic American folk song “I am weary (let me rest)”; in the script it’s described as “Epilogue: Iphigenia replies…” She has accepted her fate.

Love Me Tender is an unusual theatrical experience. The non-literal setting and the manner in which the dialogue and parallel worlds are team-constructed generate a palpable distancing effect which is counterbalanced by a sense of urgency and suspense and of having to, as an audience, make the work intelligible—piecing together the shared first, second and third person accounts of characters and events. The spare, patterned blocking, the playing directly to the audience, the moments of song, the human-animal interplay and the inventive chorus model embodied in the two prompters collaborating with the man in his drive to psychosis aptly if never literally echo Greek tragedy. As a modern version of Euripides’ Iphigenia, the play portrays a like world, but instead of an army in revolt and gods to be appeased there’s a community obsessed with the vulnerability of children, their sexuality and the way it complicates father-daughter intimacy. The father, opting for responsibility to community, to save lives as a fire fighter, abandons his daughter. Ironically it is the same community’s pathological fears that have driven him to sacrifice the child he loves, if he still does. Love Me Tender is at once an indictment of the premature sexualisation of children and of the possible consequences of the fear of it—enacted as the sacrifice of love, not just of a life.

Although a memorable production with performances totally on top of the considerable demands of Holloway’s script, I was left with some doubts about the play. It’s a work by a man about a male plight, one worth exploring, but it does little for its female characters—the daughter is only referred to, save appearing as a lamb, and the mother an onstage cipher. Neither this Iphigenia nor this Clytemnestra can offer an account of their condition, nor defend themselves against the will of the men. They cannot challenge their fate without complicating the playwright’s thrust in what is essentially a monodrama, a very clever and timely one, and almost tragic—though the father is denied any insight into his condition. Love Me Tender’s dynamic is compelling, but in the end its reliance on the play of thematic oppositions into which the feminine is not allowed to intrude limits its capacity to speak beyond the contradictions forced on the father-daughter relationship. As an experiment, not just in submitting a man to the extremities of collective social pathology, but as an exercise in adventurous narrative form, Love Me Tender is exactly what Australian theatre needs.

For another modern version of Iphigenia in Aulis, one that keeps the female roles alive, take a look at novelist Barry Unsworth’s wonderful The Songs of the Kings in which the world of Agamemnon’s army is eerily imbued with contemporary corporate-speak.

Company B Belvoir, Griffin Theatre Company & Thin Ice: Love Me Tender, writer Tom Holloway, director Matthew Lutton, performers Colin Moody, Belinda McClory, Luke Hewitt, Kris McQuade, Arky Michael, design Adam Gardnir, lighting Karen Norris, sound Kelly Ryall; Belvoir St, Sydney, March 18-April 11, www.belvoir.com.au

RealTime issue #95 Feb-March 2010 pg. web

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Camilla Hyde

Recently in RealTime, Jack Sargeant (see RT95) and Mike Walsh (see RT95) have argued for the critical discussion of Australian feature films to start incorporating the ‘invisible’: the B-grade, genre or Asian films that are screening to audiences at festivals like MUFF (Melbourne Underground Film Festival) or multiplexes in the suburbs to NESB audiences—the films not funded by Screen Australia, ones that tend to fall off the radar. These films are also gaining a following via the networking power of Facebook: even in early production, you can become a Fan, tracing the film as it’s being made, finding out about festival screenings, looking forward to its DVD release.

Dave de Vries’ feature film debut is a good example. Made on a self-raised budget of around quarter of a million dollars, Carmilla Hyde is a vamped up revenge flick that won Best Feature at the South Australian Screen Awards in March after winning Best Guerilla Feature and Best Supporting Actress (Georgii Speakman) at the Melbourne Underground Film Festival. Now it's been selected for the International Film Festival South Africa 2010. It’s a film that begs an undergrad audience with lashings of sex, drugs, rock’n’roll and girls in leather.

The central character Milly (Anni Lindner) is an androgynous looking and awkward woman, revealed to be a virgin, who spends most of her time in her room, reading, until drugged by her housemates in the callous hope of liberating her. Her alter ego Carmilla, is brought on by the mysterious machinations of her psychiatrist Dr Webster—who implants a trigger word when he hypnotises her, and introduces her to a special brand of red wine that, when sipped, unleashes the devil. The vengeful alter ego dons a long raven wig, red lipstick, fishnets and leather boots and is suddenly up for anything, including night-club stalking, back-alley sex and popping pills. The angel/whore dynamic is overtired, and nothing new is added here. It reminds me of the poor librarian in 80s videos who is turned into a goddess by losing the glasses, shaking her hair out of her ponytail and dancing in bike pants. It seems, as we watch Carmilla pash every girl in her sharehouse, and then observe her lasciviously watching a poledancer do a lapdance at a lesbian nightclub, that many scenes are about as tacky as when the lead singer in the band gropes all the starlets in a hiphop video. There’s lots of finger sucking and women having a go at the hubbly bubbly. It’s like watching soft-porn without the sex.

Writer-director de Vries comes from a background designing comics and he’s done well with the look of the film on a shoestring budget. At times it seems loosely based on Dangerous Liaisons (the Buffy version), with scheming women manipulating the desires of Milly (and her wooden lover Nathan [Cameron Hall]) and there’s the obvious titular reference to Jekyll and Hyde. The costume designer has gone to town—the women look at times like they have landed on some 70s sci-fi planet. The script, though, is full of holes, and the acting needs work. The psychiatrist, Dr Webster (Sam Tripodi), in particular, is so over the top that you half expect him to start rubbing his hands and cue an evil laugh. Perhaps that’s intentional but the serious subtext of the film—repressed memories of sexual abuse; men’s violation of women—makes it difficult to take. As the central character(s), Lindner lacks the experience to be able to transform from one character to another, without the help of costume and make-up. Unfortunately, the film’s premise (of altered states) brings to mind the brilliant United States of Tara, and Toni Collette’s completely convincing performance in bringing a number of personas to life; so much acting is in the head as well as the body. The music is so ‘dum da dum dum daaaaa’ that it reveals the mood of the scene before it’s even begun. And the film seems to slip between genres. With a lack of suspense, it doesn’t work as the ‘revenge thriller’ it’s hyped to be. The horror and sex are just glimpsed, not down and dirty enough to class as Ozploitation.

You get the feeling that de Vries needed someone to come in and help him with an honest appraisal. The script needs a good cut—the film could be chopped by a

third. There’s no really strong narrative drive. Characters have dialogue like: ‘We’re outta milk.’ ‘Okay.’ When Britt (Georgii Speakman) finds her friend bleeding in the shower, after a suicide attempt, she says, “Oh, you stupid bitch.” A man from the alley comes into the house and terrorises the women for no reason other than the chance for a gratuitous tit shot in the shower. The male characters are moronic at best. And then there’s the house. The characters appear to live in a magnificent stone cottage by the beach with endless rooms, yet none of them seem to work. Oh yes, one of them says she is a student. Perhaps the rental market is different in Adelaide.

There’s something depressing about a character who, when it’s revealed she has thrown off her shackles of repression, is transformed into a woman whose banal idea of a good time is to go through the motions, seducing all the women and men in the room, always under the watchful gaze of other men (including those behind the camera). As a fantasy it could have dealt with some more experimentation or imagination. Nevertheless, de Vries managed to raise the funds to make it. I imagine with a tighter script, a reigned-in focus and more funds in his pocket, he might come up with something special.

Carmilla Hyde, writer, director, producer David De Vries, producers Fiona De Caux, Tony Ganzis, Andrei Gostin, actors Anni Lindnee, Nina Pearce, Georgii Speakman, cinematographer Maxx Corkindale.

Carmilla Hyde will screen at the Mercury Cinema, Adelaide, dates to be announced. DVD and Blu-Ray copies will be available online from August 2010 at www.darkmirrorpictures.com

RealTime issue #95 Feb-March 2010 pg. web

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Joanna Dudley and Dirk Dresselhaus AKA Schneider TM, Louis & Bebe

image courtesy the artists

Joanna Dudley and Dirk Dresselhaus AKA Schneider TM, Louis & Bebe

There are many Australian artists based in or working regularly in Berlin: Barrie Kosky, Benedict Andrews, Paul Gazzola, musicians Clare Cooper and Clayton Thomas, media artist Jordana Maisie, dancer and choreographer Adam Linder (see RT95) and live art performer Sarah-Jane Norman are just a few who have appeared in the pages of RealTime. One we should know more about is innovative director, performer and singer Jo Dudley. On a brief visit to Sydney recently she dropped into the RealTime office to tell me about her latest work, Louis & Bebe, inspired in part by electronic music pioneers Louis and Bebe Barron.

Dudley choreographs, makes installations and collaborates on music theatre works. Her most recent creation, with designer Rufus Didwiszus and electro pop/noise impro composer-musician Schneider TM (Dirk Dresselhaus), is Louis & Bebe. It will appear at the Sophiensaele (where it premiered last year), Berlin, April 15-17, for IETM [International Network for Contemporary Performing Arts]. The video excerpts on Dudley’s website convey some of the work’s musical and physical subtleties and viscerality.

Dudley’s principal music theatre collaborator is Didwiszus. Their work The Scorpionfish was part of the 2008 OzAsia Festival in Adelaide [see RT82]. Another work, Who Killed Cock Robin, was performed with the Flemish vocal ensemble Capilla Flamenca and Dudley’s sound installation Tom’s Song for music boxes and LP players was presented at the 2006 Sonambiente Festival, Berlin [see RT74].

Joanna Dudley and Dirk Dresselhaus AKA Schneider TM, Louis & Bebe

image courtesy the artists

Joanna Dudley and Dirk Dresselhaus AKA Schneider TM, Louis & Bebe

Dudley has studied traditional Japanese music in Tokyo and traditional dance and music in Java, and recently created the choreography for the opera Eugene Onegin directed by leading German playwright Falk Richter and conducted by Seiji Ozawa for Tokyo Opera Nomori and the Vienna State Opera. Dudley has also worked with Sasha Waltz, Thomas Ostermeier, Les Ballets C de la B, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui and Heiner Goebbels.

Louis & Bebe (1 couple, 3 lives, 3 deaths) is inspired by “forgotten pioneers of electronic music”, the Americans Louis and Bebe Barron who worked with magnetic tape to create distinctive sounds—later regarded as music—which brought them into contact with John Cage, Maya Deren, Morton Feldman and others. The couple also created the ‘electronic tonalities’ score for the 1956 sci-fi feature film, Forbidden Planet.

Dudley says that Louis & Bebe is not a literal account of the work, or the lives, of the Barrons, “we had to abstract it.” A particular focus in this music theatre work is the creation and death of a sound, and the parallel life of the soul. The work moves through three phases: childhood (The Landing, Reaching for the Red Star Sky), full-blown life (Garden, portraits of a Zoomorph couple), and death (Graveyard, A Night with Two Moons). In these worlds dense with sound, “there’s not much movement”, says Dudley, “it’s like still images—snap-shotttish.” The images seen in stills from the production are striking: in Garden the couple wear long-beaked masks inspired by Max Ernst images and symbolic of “soul, flight and heaven.” In Graveyard there’s a similar bird image (“a particular stork that eats dead animals”) in an eerily beautiful altar.

Other than a 20kg bell, small bells and some foliage, the space for Louis & Bebe, says Dudley, is a stripped back Sophiensaele—where the performance “works beautifully.” It would be wonderful if Australians could see more of the creations of Dudley and her collaborators at a moment when music theatre here looks to be enjoying revived promise.

Jo Dudley, Louis & Bebe, Sophiensaele, Berlin, April 15-17; www.joannadudley.com

RealTime issue #95 Feb-March 2010 pg. web

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Pomona Road, photo Katrina Lazaroff

Major bushfires bring increased pain each year and revive memories of earlier devastating fires cruelly etched in the psyches of many Australian families. Choreographer Katrina Lazaroff's family is one of these: her first full-length dance work, Pomona Road, reflects on the enduring physical and emotional consequences of the Ash Wednesday bushfire in 1980, but in the end, says Lazaroff, it's a dance theatre work about family.

Lazaroff is a dancer, choreographer, rehearsal director and dance educator who graduated with an Honours in Dance from WAAPA (Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts) in 2001, performed with Buzz Dance Theatre in Perth in 2001, and in 2006 and 2008 with Leigh Warren & Dancers worked as rehearsal director and assistant to the choreographer. She has been Artistic Director of the Youth Dance Festival 2008 (Ausdance ACT), choreographed for Fresh Bred—SA Youth Dance Ensemble, and worked with Restless Dance Company as a choreographic mentor on Debut 1 & 2. She is currently working as a choreographer and performer with Adelaide's Patch Theatre Company and teaches company class for Australian Dance Theatre. For Lazaroff, the hour-long Pomona Road is “a huge work”, an opportunity to create a totality that draws on her artistic experience and family life and allows her to embrace a wide range of means with which to realise her vision.

In Pomona Road Lazaroff employs dance, theatre and visual and audio design to evoke the enduring suffering and the rebuildling of lives and a sense of home. Unusually for a principally dance work, she also incorporates documentary material—recorded interviews from family and community members. Not surprisingly then the show's press release declares it “new Australian documentary dance.” Certainly Lucy Guerin's Structure and Sadness is rooted in the reality of the 1983 collapse of Melbourne's Westgate Bridge, but it's not a documentary work per se. Banagarra Dance Theatre, on the other hand, has works in its repertoire based on painful social realities, but the label 'documentary' is not apt.

Pomona Road, photo Katrina Lazaroff

Lazaroff tells me that Pomona Road—in evolution since 2006 and with three stages of development—was never intended as a comment specifically on the social and emotional impact of bushfires. Her first impulse was to explore family, “where we come from.” Stage one addressed her relationship with her sister (“sibling rivalry, kooky and a bit sinister”), and stage two father-son interaction (drawing on her own family and the experience of her dancers). It was while working on stage three and addressing the whole family that she discovered that the fire experience provided a meaningful framework for the exploration of family life. The Ash Wednesday starting point offered the beginnings “of a journey and a focus on loss—of home, place, identity. And the pain of starting again—the parents tackling it, the kids bumping along.” By 2009, says Lazaroff, the fire scenario had taken over.

Lazaroff decided that she wanted to make a dance work that was documentary in character, capturing the feelings of loss to fire. To this end she interviewed her parents about Ash Wednesday 1980 and victims of the subsequent 1983 Ash Wednesday. She thinks that “feelings and relationships can be sensed” through these voices which the audience hear—sometimes on their own, sometimes in tandem with the dance. The dancers, playing members of a family, also speak, but not in a conventionally scripted fashion, their utterances a form of vocal movement—family bickering, a song, familiar expressions. Lazaroff says that in stage three of the work's development she learned to give space to the recorded voiceovers, “to let them come first, and provide continuity.”

Asked about her choreographic style, Lazaroff says it's rooted in the contemporay dance which has been her life. However, the dancers create “recognisable characters whose gestures and character traits fuse fluidly with the dance language.”

Kerry Reid's set for Pomona Road comprises simple timber structures (originally made by Lazaroff's partner from materials from her mother's verandah for the stage three development, but now re-made and evocative of her father and his fence contracting business) and large hanging sheets of white paper that receive the images from two powerful projectors that wash the whole stage with impressionistic, 'textural images of bush and fire.” With Nick Mollison's lighting and projections, Lazaroff hopes that substantial depth of field will be created.

Lazaroff describes the sound design for Pomona Road as “highly collaborative, with a lot of give and take” in its making with Sascha Budimski's score comprising “sound effects, hums, drones, voiceovers, rhythm beats and Gerry Rafferty's Baker Street”, the 1978 hit which her father played frequently.

I ask Lazaroff what creating Pomona Road has done for her. “It's been a moving experience, looking back into family history and seeing that there were many more things that happened to us than I realised. As an artist I feel it's set me free.”

inSPACE Program, Pomona Road, Space Theatre, Adelaide Festival Centre, April 21-24. Pomona Road was part of inSPACE:development in 2009.

RealTime issue #95 Feb-March 2010 pg. web

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Willoh S Weiland, Yelling at the Stars

photo Tilly Morris

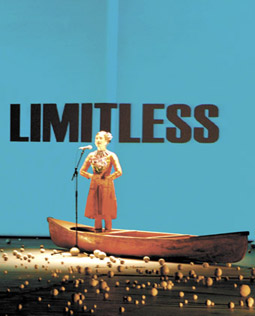

Willoh S Weiland, Yelling at the Stars

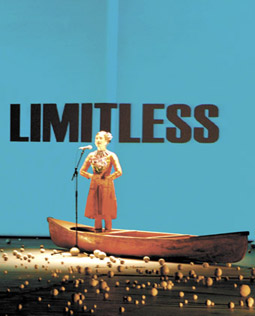

new aphids artistic director: willoh s wieland

Exciting news from Melbourne: Willoh S Weiland has been appointed as the new artistic director of Aphids. As we were putting this online edition together, Weiland was flying back to Australia. We look forward to catching up with her once she’s settled into the job of guiding one of the country’s most innovative outfits, renowned for its idiosyncratic hybrid creations and international collaborations.

A young and energetic artist, Weiland looks made for Aphids. Her projects as artist, writer and curator over recent years have been strikingly individual. The ongoing art-science project Yelling at Stars (see RT 88) was presented at the Sidney Myer Music Bowl as the closing event of the 2008 Next Wave Festival and then in Glasgow at Less Remote, an art/science symposium running parallel to the 59th International Astronautical Congress. Her 2009 Synapse residency was at the Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, where she developed Void Love (www.voidlove.tv), “a soap opera about astrophysics” starring Kamahl.

Weiland is involved in ongoing collaborations with Spat & Loogie and, as part of Deadpan, with video artist Martyn Coutts—including an Asialink residency in Beijing and NES artist residency in Iceland in 2010.

David Young, the outgoing artistic director and co-founder of Aphids (and now director of Chamber Made Opera; see RT95) sees Weiland as “hugely talented and a perfect fit with the Aphids spirit and ethos.” He thinks that with the current Aphids team, “I really cannot imagine what Aphids will become under her watch—and that’s exactly what I am most excited about.”

Lillian Starr Pinup Girl, Tina Fiveash, part of Women in Piracy

courtesy the artist

Lillian Starr Pinup Girl, Tina Fiveash, part of Women in Piracy

women and piracy

As the application of copyright laws tighten, creative commons becomes part of the big picture and internet censorship escalates, it’s timely to take yourself to Kudos Gallery to reflect on the good use to which appropriations, adapatations and thefts have been put in Women in Piracy. The show includes works by Penelope Benton, Brown Council, Tina Fiveash, The Kingpins and others. Curated by Marcel Cooper it’s part of the 2010 Sheila Autonomista Festival for queer women’s art and music centred at Red Rattler Theatre, Marrickville. Women in Piracy, Kudos Gallery, 6 Napier St, Paddington, Sydney, March 30-April 10; scooter.org.au/sheila.html

jo lloyd: 24hrs

God knows what all the fast turnaround short film and short play festivals are doing to our psyches as artists and audiences—blessed be the slow food movement—and now dance has joined the rush! But what an intriguing race it might be in the Jo Lloyd-curated 24HRS at Dancehouse. Four choreographers will each create a new work over 24 hours—one for each Friday over four weeks. Just to add to the inevitable delirium of commencing work on a Thursday night at 9pm, “the creative process will be twittered and streamed online and the teams must be ready to present the work to a live audience by 8pm the next night.” There goes the privacy associated with the slow boil of the creative process. The stellar line-up of choreographic speed freaks is Natalie Cursio, Shelley Lasica, Phillip Adams and Luke George. 24HRS, performances April 30 (Cursio), May 7 (Lasica), 14 (Adams), 21 (George), Dancehouse, Melbourne; www.twitter.com/24HOURS; www.livestream.com/24HOURS

Adrift, Nigel Helyer, Memory Flows exhibition

courtesy the artist

Adrift, Nigel Helyer, Memory Flows exhibition

cmai, memory flows

As our major easten rivers and Lake Eyre fill after an epic drought that threatens to return almost as soon as it has departed, the UTS-based Centre for Media Arts Innovation is holding a timely exhibition of underground water basin and river-inspired art. “Australian rivers are conduits that are emblematic of networking systems, travel systems and survival systems. They are also the ground for flows of memory as riverbeds, for instance, hold the memory of water embedded in the land. This project will tap into and out of memory flows—along Australia’s riverbeds and groundwater systems.” The distinctive venue, Newington Armory, and its proximity to some of Sydney’s unique waterways give the exhibition added frisson. The artists are Ian Andrews, Chris Bowman, Chris Caines, Damian Castaldi, Sherre DeLys, Clement Girault, Jacqueline Gothem, Ian Gwilt, Megan Heyward, Nigel Helyer, Neil Jenkins, Solange Kershaw, Roger Mills, Maria Miranda, Norie Neumark, Shannon O’Neill, Greg Shapley, Viktor Steffenson and Jes Tyrrell. CMAI, Memory Flows, Newington Armory, Sydney Olympic Park, weekends May 15- June 27; www.memoryflows.net

art for easter 1: sounds unsound festival

Recommended, say the organisers, for people who don’t do Easter, the Sounds UnSound Festival is “a one-day event focusing on the experimental, improvised, noise and left-field musical fringe of Sydney and beyond.” Artists include Japanese noise maestro Defektro, improvisors Forenzics, Chippendale improv group The nHOMEas, Toydeath, glass vocalist Justice Yeldham, audio-visualists Infinite Decimals, bass/drum duo The BZNZZ, Prehistoric Fuckin’ Moron(s), the computerised Scissor Lock, The Not Too Distant Future and Baad Jazz. Sounds Unsound Festival, The Wall (The Bald Faced Stag), 345 Parramatta Rd, Leichhardt, Sydney,April 2, 2-10pm; www.myspace.com/thesoundsunsoundfestival

art for easter 2: arvo pärt’s berlin mass

A special Easter Saturday performance of Arvo Pärt’s immersive Berlin Mass by Sydney Chamber Choir and the ensemble Ironwood will celebrate the composer’s 75th birthday. On the same generous program, directed by Paul Stanhope, there will be selections from Carlo Gesualdo’s Tenebrae and a work inspired by them, Scottish composer James MacMillan’s Tenebrae Responsories. Ironwood will also present a movement from Haydn’s Seven Last Words from the Cross. Via Crucis, Verbrugghen Hall, Sydney Conservatorium of Music, Sydney, April 3,

Kate Murphy, The note, 2010

image courtesy Breenspace, Sydney

Kate Murphy, The note, 2010

kate murphy at breenspace: the note

The latest work from one of the leading and more lateral of Australia’s video artists, Kate Murphy, is The note, a 10-minute, single-channel HD video installation in 5.1 surround sound. According to the Breenspace website, the work was conceived when the artist “read a distant relative’s suicide letter. Murphy asked composer Basil Hogios to develop a musical composition based on every word written in this letter.” The result is an aurally immersive video of a mezzo soprano singing in an empty theatre. Kate Murphy, The note, Breenspace, 289 Young St, Waterloo, Sydney, March 12-April 17 www.breenspace.com

RealTime issue #95 Feb-March 2010 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Kate Murphy, The note, 2010

image courtesy Breenspace, Sydney

Kate Murphy, The note, 2010

kate murphy at breenspace: the note

The latest work from one of the leading and more lateral of Australia’s video artists, Kate Murphy, is The note, a 10-minute, single-channel HD video installation in 5.1 surround sound. According to the Breenspace website, the work was conceived when the artist “read a distant relative’s suicide letter. Murphy asked composer Basil Hogios to develop a musical composition based on every word written in this letter.” The result is an aurally immersive video of a mezzo soprano singing in an empty theatre. Kate Murphy, The note, Breenspace, 289 Young St, Waterloo, Sydney, March 12-April 17; www.breenspace.com. Kate Murphy and the MCA’s Rachel Kent will discuss the work on March 20, 3.00pm.

art for easter 1: song company, gethsemane

Atheists and agnostics can join Christians in a celebration of the art that constellates around Easter in Song Company’s Gethsemane. The company’s previous collaborations with choreographers Kate Champion and Shaun Parker offered us intense meditations from singers (themselves bravely and successfully integrated into the action) and dancers, attracting large, responsive audiences.

In a radically new approach this year, instead of the Tenebrae of Gesualdo there’ll be a new score from leading Australian composer Gerard Brophy, informed by a visit to India: “Gethsemane interprets the traditional Jeremiah lamentations from the Old Testament through modern-day accounts of life on the streets of Calcutta to create a contemporary meditation on poverty, abandonment and compassion” [Press Release]. The work, directed by Roland Peelman, will be performed by Song Company and Synergy Percussion with saxophonist Christina Leonard and choreography by Martin del Amo. Gethsemane, City Recital Hall, Angel Place, Sydney, March 31; tour: Canberra: Albert Hall, March 21, Wollongong City Gallery, March 22; Bowral: Chevalier College Auditorium, March 24; Newcastle Conservatorium, March 25; Bathurst Memorial Entertainment Centre, March 27; Parramatta: Riverside Theatres, March 29; www.songcompany.com.au

art for easter 2: arvo pärt’s berlin mass

A special Easter Saturday performance of Arvo Pärt’s immersive Berlin Mass by Sydney Chamber Choir and the ensemble Ironwood will celebrate the composer’s 75th birthday. On the same generous program, directed by Paul Stanhope, there will be selections from Carlo Gesualdo’s Tenebrae and a work inspired by them, Scottish composer James MacMillan’s Tenebrae Responsories. Ironwood will also present a movement from Haydn’s Seven Last Words from the Cross. Via Crucis, Verbrugghen Hall, Sydney Conservatorium of Music, Sydney, April 3,

www.sydneychamberchoir.org

Kerry Fox, Anamaria Marinca, Storm

image courtesy 23/5 Filmproduktion/Berlin

Kerry Fox, Anamaria Marinca, Storm

festival of german film: storm

Here’s early notice that the Festival of German Film looks particularly strong this year, with contributions from Michael Haneke (the eagerly anticipated The White Ribbon: village life unravelled by strange events before World War I), Margarethe von Trotta (Vision—Aus dem Leben der Hildegard von Bingen; a biopic of the composer and visionary) and the brilliant Fatih Akin in an unexpected comic turn, The Soup: “A run-down restaurant gets a fresh lease of life when the owner hires a temperamental new chef who alienates the regular customers, inadvertently turning the eatery into the toast of the ‘it’ crowd” [Press release].

Mediaeval history is addressed not only in von Trotta’s Vision but also Sönke Wortmann’s Pope Joan (Die Päpstin): “A 9th century woman of English extraction born in the German city of Ingelheim disguises herself as a man and rises through the Vatican ranks. More recent events are resurrected in a rarely told story in Florian Gallenberger’s John Rabe, “The true story of a German businessman who saved more than 200,000 Chinese during the Nanjing massacre in 1937-38.”

Hans-Christian Schmid’s Storm is an impressive inclusion in the program. I was lucky to see a preview of this largely English language film starring Kerry Fox as a War Crimes Tribunal prosecutor thrown at short notice into the trial of a Serbian commander turned popular politician. What seems straightforward becomes quickly and dangerously complex in the manner of a good political thriller. But Schmid pays consistent attention to the realpolitik of the European Union’s attempts to defuse murderous local tensions by overriding ordinary citizens’ need to tell what happened. Storm effectively addresses the big political picture while focussing on the pain of players and victims, with Kerry Fox excellent as a lawyer who finds her own life trapped in these contradictions. Fox creates a laid back persona, droll, determined, often blunt, but increasingly alert to nuances that will test her own morality as events unfold. The fine widescreen cinematography embraces both intimate scenes and varied location choices. One pointer: as Storm unleashes its series of climactic events you certainly need to pay attention to the political and legal machinations as they play out. Storm is suspenseful, moving and memorable, its story an unusual and admirable choice. KG. Audi Festival of German Films: Chauvel Cinema/Palace Norton Street, Sydney, April 21-May 2; Palace Cinema Como/Palace Brighton Bay, Melbourne, April 22-May 2; Cinema Paradiso, Perth, April 22–26; Palace Centro, Brisbane, April 28–May 4; Palace Nova, Eastend Cinemas, Adelaide, May 7-May 9; www.goethe.de/australia

Kelton Pell, Geoff Kelso, Bindjareb Pinjarra

image courtesy the artists

Kelton Pell, Geoff Kelso, Bindjareb Pinjarra

bindjareb pinjarra: massacre & reconciliation

The 1995 stage production Bindjareb Pinjarra, an improvised work about the Pinjarra massacre created and performed by Isaac Drandic, Geoff Kelso, Sam Longley, Franklin Nannup, Kelton Pell and Phil Thomson has been revived for a season in Fremantle as part of Deckchair Theatre’s umbrella program. It focuses on “a major incident which occurred in October 1834 between Nyoongahs and the police at a place now known as Pinjarra, 90 kms south of Perth.” [For an excellent account of the massacre and associated history see www.pinjarramassacresite.com.] With a sense of both tragedy and humour, the equal mix of indigenous and non-indigenous makers aim “to show how black and white Australians are all part of the same history, and how by acknowledging that history we can move forward together to create a better future as one people.” Bindjareb Pinjarra, Victoria Hall, Fremantle, March 17-April 3; www.deckchairtheatre.com.au

arts house: future tense

This is a brief reminder that Melbourne’s Arts House has an excellent program of live art and contemporary performance from March 16 to April 3. Rivetting Australian groups Acrobat and Scattered Tacks [see RT90] are programmed alongside the intimate audience-interactive works of Rotozaza (Etiquette; Wondermart); Mem Morrison Company’s up-close wedding reception show (Ringside); and Helen Cole’s magical Collecting Fireworks, reminiscences of pivotal encounters with performance. Rotazaza, Mem Morrison Company and Helen Cole are all from the UK and give some indication of the expansive range of works that constitute live art. Arts House, Future Tense, Melbourne, March 16-April 3, http://artshouse.com.au

sydney dance company: new creations

The Sydney Dance Company’s double bill New Creations opens March 23 with 6 Breaths by artistic director Rafael Bonachela and Are We That We Are by young Berlin-based Australian dancer (most recently with Meg Stuart’s Damaged Goods) and choreographer Adam Linder. Read the RealTime interview with Linder about his career and his new work with its focus on altered states of being. Sydney Dance Company, New Creations, Sydney Theatre, opens March 23; www.sydneydancecompany.com

RealTime issue #95 Feb-March 2010 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lake Mungo, Mungo Productions, 2009

IN A CHILLING CLIMACTIC MOMENT IN LAKE MUNGO, A FEATURE FILM BY JOEL ANDERSON, AN ADOLESCENT GIRL COMES FACE TO FACE AT NIGHT WITH HER ZOMBIE-ISH SELF ON THE BED OF DRIED-OUT LAKE MUNGO IN FAR SOUTH-WESTERN NEW SOUTH WALES. LIKE OTHER EVENTS IN THIS GRIM MOCK INVESTIGATIVE DOCUMENTARY, THE ‘EVIDENCE’ IS MEDIATED BY AV TECHNOLOGY. HERE WE WITNESS NOT THE ACTUAL EVENT BUT THE GIRL’S OWN MOBILE PHONE RECORDING OF HER FATE. ELSEWHERE IN THE FILM, AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHS AND FILMS, FAKED AND NOT, LEND CREDENCE TO THE FACTICITY OF A POSSIBLE HAUNTING OF HER FAMILY BY THE GIRL. SHE HAD DROWNED IN A LAKE NEAR THE TOWN OF ARARAT NOT LONG AFTER HER LAKE MUNGO TRAUMA.

In Josephine Starrs and Leon Cmielewski’s land(sound)scape, the same Lake Mungo is the subject of a media art installation that contemplatively conjures a largely forgotten 19th-century moment, when migrant Chinese labourers were contracted to build sheep station sheds from soon to be exhausted local cypress pine forests. The Chinese found the strange, weather-sculpted shapes of Lake Mungo’s surface oddly familiar, seeing in them the ‘Walls of China’, a naming that persists to this day.

![lake mungo, land[sound]scapes, installation, josephine starrs and leon cmielewski, 2009](https://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/34/3460_gallasch_lakemungo_install2.jpg)

lake mungo, land[sound]scapes, installation, josephine starrs and leon cmielewski, 2009

Land(sound)scape is not about ghosts but the way the work resurrects the past is curiously unsettling as you sit in a former Tea House in the Chinese Garden of Friendship, Darling Harbour, Sydney. The room is largely made of timber, the names that echo through it are Chinese and we observe the land they inhabited and which evoked for them a distant home.

Sunlight is softly filtered through the room’s blue-tinted windows. On either side of the viewer are two large screens on which land(sound)scape’s gentle disorientations are generated by the contrasting movement of images. On one screen photographs of the uninhabited Lake Mungo landscape pulse slowly, and uncoventionally, right to left revealing strange figurations, buttes, small canyons, empty horizons. On the other, the orientation is aerial, a satellite point of view. We look down steeply onto the white beds of Lake Mungo, stark surrounding country and patches of green vegetation. Our internal movement feels like a slow dance in the air as we shift from the horizontal plane of the first screen to the verticality of the second.

Amid the factual if lyrical interplay of photographs, satellite images and the spoken, layered lists of immigrant and ship names and arrival dates (in Mandarin and Cantonese-inflected English) we notice something quite unexpected—the vegetation here and there spells out words and phrases that eventually form a poem. This quietly fanciful insertion generates another temporal and spatial layer—the evocation of a contemporary Chinese sensibilty nostalgic for a fading past. The artists explain: “[the immigrants] may have been homesick and wished to give the landscape a Chinese name as the formations do resemble some of the eroded outer walls in China. The text incorporated in the satellite image video, ‘I only wish to face the sea,’ is from a poem by the Chinese poet Hai Zi, 1964-1989. His poetry is about the disappearing Chinese landscape, and expresses nostalgia for the traditional countryside brought about by the large scale migration from the country to the cities.”

![satellite view, land[sound]scapes installation, josephine starrs and leon cmielewski, 2009](https://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/34/3459_gallasch_lakemungo_install1.jpg)

satellite view, land[sound]scapes installation, josephine starrs and leon cmielewski, 2009

In another unsettling moment, the crackling of fire breaks through the Lake Mungo ambience, “refer[ring] to what is known as the Lake Mungo Magnetic excursion; evidence of a change in the earth’s magnetic field 30,000 years ago which has been discovered in the ancient Aboriginal fireplaces found at Lake Mungo.” The subtle perceptual shifts that land(sound)scape subject us to now vibrate with a long ago tilting of the earth’s axis while we contemplate much more recent cultural history.

Lake Mungo is a significant archaeological site of ancient Aboriginal life, dating back at least 40,000 years. In land(sound)scape that history is not central to the work but it is acknowledged, while in the film Lake Mungo it’s absent—the landscape is simply eerie, haunted by a palpable image of death to come. Either the filmmaker was ignorant of Lake Mungo’s cultural significance or chose to sidestep it. A pity, as its deep history would seem an asset for a horror film—a landscape already populated with spirits. Perhaps the issues and negotiations entailed might have been too much to handle in a whitefella ghost story.

Martin Sharpe, David Pledger, Rosie Traynor, Lake Mungo

Mungo Productions, 2009

Martin Sharpe, David Pledger, Rosie Traynor, Lake Mungo

For an Australian horror film Lake Mungo is atypically restrained. Although over-extended and with just too many loose ends, its quiet, consistent pressure on the viewer to read images and attend to words closely makes us more than mere observers. We look repeatedly and forensically into photographs and videos. At the same time the film’s cinematography oscillates between its ‘documentary’ content (interviews, news and home movie footage) and sustained, immersive images of the night sky, of the time lapse turn of the stars and beautiful light patterns on the cusp between day and night. While adding to a pervasive sense of eeriness, of vast spaces and forces beyond the haunted confines of the home, these moments lend the film a measured, reflective quality supported by the consistency of the documentary tone and the realistic un-melodramatic performances (including Not Yet It’s Difficult (NYID)’s David Pledger as the father)—most apparently improvised.

But what Lake Mungo imparts is not revelatory: means are more interesting than ends. The dead girl’s remorse over her secret sex life with a couple-next-door is the underlying motive for her suicide. Sexual abuse is a harsh reality, but its pervasiveness as a too-convenient trope in theatre and film plots mostly exhausts it of any meaning beyond itself. This relieves artists from addressing complexity of character, which remains simply mysterious. Of course, that’s the appeal of much of the horror genre, a therapeutic revelling in and acceptance of the inexplicable, here embodied in Lake Mungo as a place where, simply, very strange things can happen. The 40,000 year-old remains of Mungo Man and Mungo Lady are not invoked, nor the land’s inheritors, the Barkindji, Nyiampaa and Mutthi Mutthi peoples who today manage the Mungo National Park with the NSW Government.

Joel Anderson’s Lake Mungo is located firmly in a European tradition of ghost tales—specifically ones tied to visual technologies. The opening credits comprise Edwardian-styled, sepia-tinted photographs of ghostly figures and ectoplasmic outpourings, locating the narrative immediately in the contested arena of documentation and fakery. But true to the genre in general, the otherworld is a place of fear, a limbo of guilt: the girl haunts her family into discovering the shame that killed her. The otherworld of Aboriginal Dreaming, however, is home to good spirits and bad, a place actually made explicable through inherited knowledge rooted in the land.

Doubtless, this landscape will inspire more art projects. A notable earlier one was Sydney performer Tess de Quincey’s Lake Mungo Project, Square of Infinity (1991-94) which premiered in the lake bed and was made into a film, the live solo performance entitled is (1994) and the touring production is.2 (1995). De Quincey seemed to evoke through the almost still movement of one body the expanded sense of time and space associated with this place.

While Anderson’s fascinating film uses Lake Mungo for its title and as the location for a key narrative turning-point, a meaningful connection between plot and site, culturally, thematically and cinematographically, is not made. It might be a lot to ask of a popular suspense horror film, but its intelligence, not least about ways of seeing, is so evident that it’s surprising a deeper connection with the site wasn’t made.

Of course, Starrs and Cmielewski’s land(sound)scapes has none of the constraints attached to feature filmmaking and these are works of very different scale and intent. Land(sound)scapes embraces Lake Mungo directly, allows us to take it in and reorients that perspective, visually and historically. It tells a story—of 19th-century migration, with hints of ancient time—in the broadest terms, but the narrative is found in standing between the two screens, in the turn of head and body, and landscape, and in the roll call of the long dead—not ghosts, but newly remembered and ever present.

Land(sound)scape was originally developed for the 2008 Guangzhou Triennial. In 2010 it was a Chinese New Year event presented by Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority. Josephine Starrs and Leon Cmielewski are Sydney-based artists: http://lx.sysx.org.

land(sound)scape, Josephine Starrs & Leon Cmielewski, voices Wendy Ju, Jenny Ng, Lionel Bawden, HD video editing Greg Ferris; Chinese Garden of Friendship, Darling Harbour, Sydney, Feb 12-28

Lake Mungo was shown at the 2009 Sydney and Brisbane Film Festivals and is to be remade in the US for Paramount Vantage.

Lake Mungo, writer, director Joel Anderson, actors Talia Zucker, Rosie Traynor, David Pledger, Martin Sharpe, Steve Jodrell, cinematography John Brawley, editor Bill Murphy, music David Paterson, Fernando Corona, production designer Penny Southgate, visual effects supervisor Mathew Mackereth, sound Anne Aucote, sound designer Craig Carter; producers George Nevile, David Rapsey, executive producers Bill Coleman, Gilbert George, Robert George, 87 minutes; www.lakemungo.com

Originally published in the March 15, 2010 online edition.

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. 25

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Shahrukh Khan, My Name is Khan

copyright Dharma Productions

Shahrukh Khan, My Name is Khan

THE YOUNG WOMAN SEEMED DUBIOUS ABOUT SELLING ME A TICKET: “YOU KNOW THIS IS A FILM FOR INDIANS? BOLLYWOOD AND ALL THAT?”

The movie in question was the Hindi blockbuster My Name is Khan. It opened recently at number 10 at the Australian box office with the second highest per screen average of any film that week, a fact that film website Urban Cinefile remarked upon despite its having “been released under the radar” (which I take to mean that, like all Hindi films, it was not reviewed in any of the mainstream media, including Urban Cinefile). It seems that our film critics, taking their lead perhaps from the Victorian Police, are still in denial over the existence of Indians in our midst.

In the last issue of RealTime, Jack Sargeant made a case for what he labelled Australia’s invisible cinema—self-funded horror movies made by young wannabes [RT95,]. But here is a much more significant invisible cinema, one which equally puts large numbers of bums on seats.

By my reckoning, 19 Indian films were released in Australian cinemas last year, grossing around $3.5 million. The marginalisation of these films by the mainstream critical establishment is typical not only of Indian films but also of Chinese films such as Bodyguards and Assassins or Overheard, which are also consistently released these days in subtitled versions in Australian multiplexes.

The increased prominence of these films is in direct proportion to the growth of Asian communities in Australia. At the last census almost 1.7 million people identified themselves as having Asian ancestry. In central Melbourne alone, over 31% of the population was of Asian extraction.

Surely the cinema has a role to play in incorporating new communities within Australian society, rather than perpetuating the exclusionary racist bases of what has traditionally been defined as Australian.

A sub-titled French film like A Prophet can be released with fewer prints than My Name is Khan and take much less at the box office but David and Margaret will be all over it. European films fit comfortably into established arthouse distribution and exhibition channels and conventional modes of critical reception. There is still the assumption, however, that popular sub-titled Asian films, and by extension their audiences, exist within a diasporic ghetto whose walls cannot and probably should not be breached. On leaving the cinema after My Name is Khan, I overheard two ushers discussing the need for care with the audience because “many of them probably won’t speak English.”

On the contrary, the family of Sikhs who eagerly came over to discuss the film spoke better English than me. I am learning that such conversations are not uncommon when attending Indian films, where South Asian audiences are often eager to embrace anyone who shows curiosity about their cultural pleasures.

These issues have a particular saliency when thinking about My Name is Khan, a film which deals with the tribulations of Indians living in western societies. It tells the story of Rizwan Khan, an Indian Muslim living in the United States. He has Asperger’s Syndrome, giving Indian superstar Shah Rukh Khan the opportunity to channel Dustin Hoffman in Rain Man and Tom Hanks’ Forrest Gump. In the aftermath of September 11, Rizwan and his family suffer vicious attacks and exclusion from the white majority. He sets off to wander the US in search of the President so he can proclaim to him, “My name is Khan, and I am not a terrorist.” This becomes an anthem embraced by the marginalised and the excluded who now stand up for their place in society.

The film is made by India’s leading commercial producer-director, Karan Johar. (Spell-check has just suggested to me that I substitute “jihad” for his surname. Note to Bill Gates: You might want to get that fixed.) Johar has become something of a specialist in making films set in the US. Kal Ho Naa Ho (Tomorrow May Not Be, 2003) is set entirely in New York and has Shah Rukh Khan performing an Indianised version of Pretty Woman in front of an American flag. Last year Johar’s Dharma Productions made Dostana, a sex comedy set among hedonistic Indian expatriates in Miami.

It should be no news that commercial Hindi films are often set in western cities. Australian governments are almost as eager to attract Indian film crews as they are to attract Indian students. Within Hindi cinema, these cities are then transformed into glamorous locales full of Indians living the cosmopolitan good life, synthesising the freedoms of modernity with their cultural traditions. America, in a film like My Name is Khan, functions as the arena in which Indians’ globalised aspirations are played out. A threat to it is therefore a threat to India. The nightmare which this film confronts is that the flaws of communal prejudice in India’s own past are suddenly reasserted in a fantasyland of its future.

Why am I thought to be aberrant for liking these films? Hindi cinema cranks up style and emotion beyond a point generally thought to be acceptable in the drier and more ironic reaches of western cinema. When was the last time you saw George Clooney cry? Well, barely a scene goes past in Hindi film without tears.

And we all know that Bollywood cinema commits the unpardonable sin of singing and dancing. It is a cinema which defies social realism in favour of a more utopian take on the world. At one point in My Name is Khan, someone gives Rizwan a video camera, telling him that when you are scared, it is easier to look at the world on a screen and then it’s easier to handle.

The film’s energy comes partially from its craziness as it hoovers up everything in its path—Guantanamo Bay, Hurricane Katrina, Barack Obama’s election—and puts it at the service of a highly charged set of emotions constantly on the verge of spiralling out of control. And finally, this is the major attraction of Bollywood: the assertion that humanity is, at its core, a mass of emotion, and one of the major functions of cinema is its unique ability to reach to that core through heightened manipulations of style.

Let me turn to another foreign film which, by way of contrast, everyone has seen and upon which every critic has delivered an opinion. At one point in James Cameron’s Avatar the baddie confronts our hero and asks him, “How does it feel to betray your own race?” Not a bad question in a film which tries to set up a safe fantasy space for American liberals in Obama’s America to try out what it feels like to become a more righteous colour. Though, of course, Avatar is also an assertion of the continued dominance of the strong and the rich. The blue people embrace the leadership of the white guy just like Australian audiences shelled out $110 million to its American distributor.

For Australians the cinema has always asked us to betray, if not our race, then at least our country by imagining other places that are more modern and filled with strange and fantastic aliens we call movie stars. Perhaps it is time to move beyond the conservative limitations of these fantasies and to truly betray our race if this means enlarging our sense of what the world and Australia might contain.

The presence of popular Indian and Chinese cinemas in our multiplexes offers the possibilities of including and embracing what has been seen, for too long, as external to Australia. To be Australian, after all, has always been to be open to the influences of the new and the unAustralian.

Originally published in the March 15, 2010 online edition.

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. 17

© Mike Walsh; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Curated by Dorkbot Sydney’s “Overlord” Pia van Gelder, the dorkbot-syd group show was a small, well-balanced exhibition presenting the recent experiments of Sydney’s creative tinkerers. I missed the crammed opening, instead opting for the artist talk several days later.

Reminiscent of a shrine, Samuel Bruce’s installation, Art is great to waste time before dying, was situated by the pillar in the centre of the room. The hand-constructed speaker box and cattle skull with embedded red LED flashed away, accompanied by a cloud of chaotic noise, an offering from the artist as a memento mori, a reminder that one day we all must die.

Warren Armstrong’s software application, Twitterphonicon, as the title suggests, drew on a range of Twitter tweets, identified by selected hashtags. Sonifications of phrases, created by mapping words to various general midi instruments, produced short monophonic melodies. The mapping—always a challenge when using streams of data—was far too simplistic, and I was left desiring more. However, the work became more promising during the artist’s talk when Armstrong read aloud a tweet, spoken in synchrony with the sonification. All the audience agreed: Twitterphonicon was destined for a performance poetry future.

Light Speed Sound #2, Melissa Hunt

photo Somaya Langley

Light Speed Sound #2, Melissa Hunt

Light Speed Sound #2, by Melissa Hunt was immediately accessible with little instruction. It utilised light dependent resistors hooked up directly to the motor of a toy turntable plus some circuit bending skills and assistance from Nick Wishart. Hunt has no-doubt created what numerous teenage bedroom DJs dream of at night—the ultimate air-turntable interface. Hours of fun for those who like to wave their hands in the air while manipulating sound.

Lukasz Karluk, with collaborator Gentleforce, created the most striking work of the exhibition. Partly due to its size and also to an inviting interface, tr-IO earned this accolade with its video projection of triangular patterns spanning one entire wall of the space. Constructed from three polypropylene pyramids, Reactivision symbols pasted on the bases, and complete with pulsing LED colours, no child or adult could resist picking up these objects. Reposition the pyramids on the plinth and the projected image (think Tetris crossbred with patterned doona cover design) altered colour spaces, pattern sizes and perceptions of direction and speed of movement. Hitting the nail on the head in terms of mapping, the work wasn’t so complex such that you’d wonder whether it was interactive at all. Neither was it too obvious: shifting an object just once wouldn’t entirely demystify the process.

Programmable Light Metronome is exactly what it purports to be. Composer Amanda Cole developed this system out of her need for a device that did not exist. Utilising fairy lights, an Ardiuno microcontroller and MaxMSP, the Programmable Light Metronome was essentially created to provide a visual cue for musicians who perform her compositions (which often consist of dual time signatures and resultant cross rhythms). As an artwork it appeared purely decorative; as part of a larger work it holds the potential to be more.

Niche, Tega Brain

photo Pia van Gelder

Niche, Tega Brain

Occupying the back corner, Tega Brain’s Niche effected the most engaging user interaction with a projection of imaginary plant life, allowing users to tread on it, watch it die and regenerate. The work teased out intrinsic behaviours in audience members: some stood back to watch the plants grow, others stamped their feet to kill them off as rapidly as possible. Listening to Brain speak about Niche was rewarding. Knowledgeable and technically adept, the artist expressed her wish to expand the work to incorporate rewarding various forms of audience behaviour. This work was unfortunately let down by the exhibition space. The marked floor masked the detail of the plants, while the projection shook as occupants of the venue moved about upstairs.

Having exhibited their works, I suspect the artists have lists of modifications and possible enhancements that they’d like to implement if they ever get the chance. As is frequently the case when discussing experimental electronic works suggestions for improvement are always proffered. The artist talk illustrated the fact that so often such works are proof of concept, and with access to better resources the quality and professionalism of the works would increase a thousand fold.

The risk in developing these kinds of experimental electronic works is that the creative focus becomes the making of the tool. As I walked away from the exhibition space, I was accompanied by the question, “When is the moment the instrument slips away and the art emerges”?

Dorkbot-Syd Group Show: People doing strange things with electricity, curator Pia van Gelder, artists Warren Armstrong, Tega Brain, Samuel Bruce, Amanda Cole, Melissa Hunt, Lukasz Karluk + Gentleforce and Gavin Smith. Serial Space, Sydney, Feb 10-13, http://dorkbotsyd.boztek.net/

RealTime issue #95 Feb-March 2010 pg.

© Somaya Langley; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ross Coulter, Simon Obarzanek, Antony Hamilton, Byron Perry, Untrained, Lucy Guerin Inc

photo Belinda: artsphotography.net.au

Ross Coulter, Simon Obarzanek, Antony Hamilton, Byron Perry, Untrained, Lucy Guerin Inc

Lucy Guerin Inc has been established in Melbourne since 2002, gaining momentum through the steady production and touring of well received dance works. Guerin occupies a focal place in the Australian dance ecology, maintained by the excellence of her choreography, the diversity of her artistic collaborators and presenting partnerships and her support for emerging artists. Guerin has a generous and modest persona, which carries through into her quietly authoritative work.

Born in Adelaide, Lucy Guerin graduated from the Centre for Performing Arts in 1982 before dancing for Russell Dumas (Dance Exchange) and Nanette Hassall (Danceworks). She moved to New York in 1989 for seven years and danced with Tere O’Connor Dance, Bebe Miller and Sara Rudner. Guerin’s pedigree shows in work that is highly crafted, fascinated by choreography and eager to explore aspects of everyday behaviour inside abstract frameworks.

In the last five years, Guerin’s profile in Australia has developed significantly. Previously, she was prolific but her repertoire was varied to the point of experimentation. Works presented in New York or in Melbourne’s more peripheral theatres combined with a programme for ACMI’s gallery spaces to introduce an energetic new vision to the contemporary Australian dance scene.

It was not until 2005 that Guerin began to achieve the rhythm that now enables her to create and present work in major festival contexts and important spaces like Melbourne’s Malthouse and Sydney Opera House.

The programme of short works, Love Me, and the full evening production, Aether, both premiered in 2005, followed in 2006 by another major premiere, Structure and Sadness. These works remain in Guerin’s repertoire and have attracted national and international acclaim and prestigious prizes, including a Bessie (New York Dance and Performance Award) for choreography for her work Two Lies in 1997, a 2000 Sidney Myer Performing Arts Award for Achievement by an Individual, a Helpmann Award for Best New Dance Work (Structure and Sadness) in 2007, and the 2008 Australian Dance Award for Best Performance by a Company.

The coverage of Guerin’s progress elaborated in RealTime’s archives, depicts her movement from the margins to the mainstream in terms of presentation. It maps this trajectory with the altogether less predictable diversity of her interests. A preview of Corridor, which premiered at Melbourne International Arts Festival in 2008 also explores Guerin’s contemporaneous collaboration with Japanese choreographer Kota Yamazaki. A review of Guerin’s Love Me, is followed in the subsequent edition of RealTime with a review of her annual commissioning program for emerging choreographers, Pieces for Small Spaces. Guerin’s collaborations with visual artists such as Patricia Picinnini and David Rozetsky show her willingness to be challenged by peers with a signature aesthetic. This openness extends into sound, as Japanese composer, vocalist and producer Haco, created the score for Corridor and Guerin has worked with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra and Australian Opera. Guerin also collaborated with Chunky Move on Tense Dave and Two Faced Bastard, works that toured to the US.

The most recent RealTime reference to Guerin places her at the forefront of developments in Australian dance. Touring more widely than ever internationally, she is also extending into the Australian regions and will embark upon her longest ever tour in 2011 through the Australia Council supported Roadwork touring circuit. Untrained, the piece that offers Guerin this breakthrough, was exhaustively reviewed in RealTime’s Dance Massive residency and the range of responses to the work proves how many nerves Guerin is able to touch.

Sophie Travers

reviews: lucy guerin inc

consumption a la mode

phillipa rothfield: arcade

expectation and revelation

phillipa rothfield: melt

immaculate melding

keith gallasch: melt and the end of things

bodies as signals, nodes, networks

john bailey: aether

love undone

keith gallasch: love me

lateral moves

phillipa rothfield: pieces for small spaces

risky business adds aesthetic value

philipa rothfield: structure & sadness

a spontaneous sounding

jodie mcneilly: aether

nothing hidden, nothing much gained

carl nilsson-polias: untrained

reality dance

keith gallasch: untrained

reviews: collaborations with chunky move

contaminating bodies, existential dances

jonathan marshall: tense dave

awestruck by dance

john bailey: two-faced bastard

interviews & related articles

between temperature and temperament

jonathan marshall interviews lucy guerin

melbourne international arts festival: inside out/outside in

sophie travers interviews lucy guerin

a branching practice

gail priest interviews haco

purist, improvisor, shape-shifter

sophie travers interviews anthony hamilton

australian dance: unseen at home

sophie travers: national dance touring & roadwork

Bran Nue Dae

image courtesy Roadshow

Bran Nue Dae

WATCHING RACHEL PERKINS’ BRAN NUE DAE ON A WARM, DANK AFTERNOON IN SUBURBAN SYDNEY’S RANDWICK RITZ WITH A LARGE AUDIENCE OF OLDER COUPLES AND YOUNG FAMILIES WAS A FASCINATING EXPERIENCE. LAUGHTER RANGED FROM SPORADIC TO UNANIMOUS WHILE THE FILM’S CLIMAX WAS GREETED WITH MUCH APPLAUSE AND A SUBSEQUENT BUZZ OF SATISFACTION. ACTORS’ NAMES WERE MUTTERED APPROVINGLY AS THEY APPEARED ON SCREEN—GEOFFREY RUSH, ERNIE DINGO, DEBORAH MAILMAN, AUSTRALIAN IDOL FINALIST JESSICA MAUBOY—WHILE OTHERS—KELTON PELL, NINGALI LAWFORD WOLF—LOOKED FAMILIAR: “THAT’S…?”

When I was a kid in the 50s, comedies and musicals often featured opening credits with cartoon figures or animations. Perkins immediately establishes her film’s retro tone—in bright tropical skies an animated black angel knocks a white one out of place. Before we know it we’re immersed in a world of iconic figures—young lovers, an anxious parent, a cruel authority figure, an avuncular helper and some could-be-baddies—who all sing and dance at the drop of a hat. With its fusion of romantic comedy, coming of age and road movie genres, brisk changes of location, if lovingly fixated on Broome, and broad characterisations, the film sustains a sense of immediacy, escalating furiously towards the end when the lovers are reunited and tangles of paternity are unravelled.