Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Harrison Gilbertson, Geena Davis, Accidents Happen

GRIEVING—ITS NATURE, ITS STAGES (AS IN THE DISPUTED KÜBLER-ROSS MODEL), AVOIDANCE OR REFUSAL TO LET GO OF IT—IS ONE OF LIFE’S MORE IMPONDERABLE STATES OF BEING. ITS SENSE OF LOSS IS DEEPLY BOUND UP WITH REFLECTIONS ON LOST OPPORTUNITIES AND UNFULFILLED DREAMS AND IS SOMETIMES IMBUED WITH FEELINGS OF GUILT, OF HAVING CAUSED HURT OR EVEN DEATH.

This is the raw material for director Andrew Lancaster and writer Brian Carbee’s remarkable feature film, Accidents Happen, a nervy, funny suburban parable about a family and their neighbours enmeshed in a web of accidents, the causes sometimes innocent, and the complexities of grieving, loyalty and responsibility. Gradually the film’s tone shifts from ironic detachment to demanding emotional engagement as grieving and denial each reach critical mass.

The film opens in 1974 in lower middle class American suburbia with a nasty accident—a neighbour sets fire to himself and stumbles in slow motion, flaming, towards a small boy, Billy, playing beneath a garden sprinkler. It’s an ugly scene but a curiously beautiful one, as if a child’s dreamlike recollection. A little later the boy’s family go to a drive-in where they watch The Three Stooges (with their trademark mix of malice and accident) and suffer eldest son Gene’s bad public behaviour, enacted with his close friend Doug, a neighbour’s son. On the way home the resulting argument plus Billy’s move to the front seat and the father’s distracted driving result in a serious crash. These early scenes, a retrospective prelude, establish the initial mood of the film, brisk, shocking, witness to the role of chance and the complexities of cause, effect and responsibility.

Now it’s 1982: Billy (Harrison Gilbertson) is 15. His father (Joel Tobeck) has left the family for a new marriage, his mother Gloria (Geena Davis) is in bitter denial, keeping the world at bay with dark witticisms and refusing to see Gene, who is in care and visited regularly by Larry (Harry Cook), the second eldest boy, who blames Billy for the car crash (and, cruelly, for the fiery death of their neighbour). Billy, in the manner of his own grieving, emulates Gene by befriending Doug (Sebastian Gregory) and tempting him into misadventure, but their brief partnership causes a very serious accident. From this flow the events that—regardless of the resistance of the protagonists—will bring not today’s much vaunted ‘closure’ but at least release from the stranglehold of grief.

As tense and explosive as this scenario later becomes, the filmmakers nonetheless sustain just enough distance (Gloria’s jibes, Billy’s retorts, glimpsed character eccentricities, coincidences and smaller accidents) to maintain an essentially comic rather than tragic vision. There’s even a touch of deus ex machina in the plot resolution, but in the meantime the emotional drama deepens—trust is betrayed, physical pain inflicted on self and other and relationships are sundered, but equanimity is finally achieved and frozen lives are allowed to thaw and begin again.

A great strength of the film is its ensemble playing with uniformly good performances, script and directorial attention foregrounding each of the characters. It’s quietly done, for example, in the case of Dottie (Sarah Woods), whose suspicions never corrupt her neighbourliness, and more acutely with Ray, Billy’s feckless father, who comes into clearer focus as the film progresses: “But we can’t just wait for Gene to die, Gloria. We’ll waste away with him…Lose all feeling. Turn into vegetables. Make a salad.” Even the most minor figures are deftly sketched: the girl who must hug everyone suddenly and too vigorously at a wake, or Aunt Louise who disruptively appears there too: “Here’s to the living. You know what they say? When God closes a door he opens a beer.” Another neighbour, Mrs Smolensky, the wife of the immolated man, appears briefly if recurrently in what becomes a key symbolic role in a tightly crafted screenplay.

Geena Davis’ Gloria is central to the film, although she’s not always on the screen. Gloria’s loss of two of her children, then her husband to another woman, of her uterus to a hysterectomy and later her trust in Billy is a load she struggles to bear when not withdrawn—playing Bingo with friends, going on a date, always joking (“If I’m lucky, the Department of Health will board me up”). There are revealing moments when she cracks, for example after the wake: “I always think the next funeral will be Gene’s. I can’t go home,” she weeps. When she fears that Billy is turning into the delinquent Gene she atypically can barely speak. When Billy says he can’t recall much about his dead sister Linda, Gloria’s fury demands that he think again, which apologetically he does, because he can with his mother.

The relationship between Billy and Gloria is of easy intimacy, in the way he advises on the choice of earrings before her date or joins in droll exchanges: “Gloria: I’m so hungry I could eat a crowbar and shit a jungle gym. Billy: Good. All those loose screws you have will finally come in handy.” Davis invests power in Gloria’s facade, reveals its fragility and displays a warmth in her relationship with Billy. But hoping to see the overt smiling charm of Davis in this tough mother role risks missing the subtleties of a strong performance.

When Billy finally confesses the full extent of his sins, he argues, “I was trying to protect you.” Gloria retorts, “I don’t need protecting, Billy. I need someone who is on my side, damn it.” In Harrison Gilbertson’s fine performance as Billy, we see an adolescent trapped by accidents not all of his own making, but complicated by lies and loyalties and a rapidly escalating number of ethical crises—dealing almost simultaneously with discrete problems involving his mother, father and Doug and the police. Gilbertson plays Billy with a quiet charm, who at his lowest point sounds not unlike his mother: “I’m sorry you lost your father but this could turn into a great big shit shower with, like…no soap.”

Afforded the luxury of two viewings of the film and a reading of the screenplay, I’m convinced that Accidents Happen is a significant Australian film. Yes, it’s written by an American about his America of the early 1980s, and, yes, Geena Davis aside, it’s directed, acted and otherwise made by Australians and filmed here. For some that’s a problem. But the writer has lived in Australia for 15 years and the film is faithful to his vision. The actors’ accents are largely fine, as accurate if not more so than certain Australian actors who frequently play in Hollywood films with their trans-Pacific accents. Some criticism of the film reminds me of the rejection of Frank Moorhouse’s novel Grand Days from consideration for the Miles Franklin Award on the grounds that it was set in Europe, even though the principal character was Australian. Other criticism finds it difficult to locate the film, as if it’s totally alien. Surely, if with its own idiosyncrasies, it sits firmly in the tradition of the domestic dramas of American indie filmmaking (recently, Little Miss Sunshine, The Savages, Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead, Juno etc) and more commercial ventures in the same idiom like American Beauty and Revolutionary Road (both by British director Sam Mendes).

Accidents Happen is bracing cinema—funny, cruel, suspenseful and wise, never letting the viewer off the moral hook with loveable characters and a predictable tale. Its tonal, structural and thematic integrity is supported by the slightly heightened aesthetic of the production and art design (Elizabeth Mary Moore, Angus MacDonald) and the cinematography (Ben Nott), evoking the 80s while intensifying the everyday in what is a very contemporary, shadowy parable—and something more than mere realism. It’s a tale underscored with an essentially comic vision that allows for redemption and regeneration in a small suburban cosmos, if against the considerable odds of an accidental universe. Great writing, directing and acting make Accidents Happen’s wickedly tough, idiosyncratic vision of grieving a truly memorable experience.

The world premiere of Accidents Happen was in April 2009 at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York and in June 2009 it was shown in the Sydney Film Festival. Australian screenings commenced April 22, 2010.

Accidents Happen, director Andrew Lancaster, writer Brian Carbee, cinematography Ben Nott, editor Roland Gallois, composer Antony Partos, producer Anthony Anderson, production design Elizabeth Mary Moore, art direction Angus MacDonald, Redcarpet Productions; http://www.accidentshappenthemovie.com/

This article first appeared online April 27

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. 19

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Brian Carbee as Bingo caller in Accidents Happen

BRIAN CARBEE IS THE WRITER OF DIRECTOR ANDREW LANCASTER'S FIRST FEATURE FILM, ACCIDENTS HAPPEN. IT'S ALSO CARBEE'S FEATURE DEBUT, A SCREENPLAY THAT EVOLVED FROM A DANCE WORK INTO A NOVEL AND INTO A SCRIPT.

The film premiered in 2009 at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York and then at the Sydney Film Festival. I met with Carbee as the film’s Australian season was about to be launched prior to American distribution in cinemas and on demand. I asked Carbee to detail the evolution of the film and to place it in the context of his career as an actor, dancer and choreographer and how those roles have influenced the way he writes for a film and collaborates on its making.

background

Born in the United States, Brian Carbee trained as an actor at the University of Connecticut, worked as a dancer and choreographer in Boston and New York and then migrated to New Zealand in 1986 where he created works for Limbs Dance Company, danced with Douglas Wright Dance Company and produced works for his own company, The Jump Giants. Carbee moved to Sydney in 1997 and made In Search of Mike, a 30-minute dance theatre piece which he adapted into an eight-minute film (see RT44) directed by Andrew Lancaster. He created Glory Holy! (see RT41), a much praised text-based dance work for One Extra’s 2000 season of Foursome and the following year made Stretching it Wider (see RT42) in collaboration with Dean Walsh. In 2004 he won the IF Award for Best Unproduced Screenplay for Accidents Happen and in 2005 the script was chosen to be part of the FTO NSW Aurora screenplay development project.

early evolution

How did the film evolve?

Its genesis was an exploration of language in the relationship I had with my mother. At that point it was a duet with a choreographic and a large textual element. I have a background as an actor. That’s where I started dancing, in drama school. So over the years I started to develop work that incorporated text because that was another skill I had and it was really interesting melding the two. It started to morph into various other forms. I did a bit of the material as stand-up once.

I moved to Sydney in 1997. I was approached by Leisa Shelton to be part of Inter-Steps at Performance Space. I thought, let’s re-work it. I was new here and I just wanted to land on something I felt secure with. So I made it into a solo and expanded the choreographic element and kept much of the textual component. Andrew Lancaster was in the audience one night—one of four. He just bailed me up afterwards and said, “Look that was really interesting. I’m a filmmaker and I’d like to make a short film out of it.” And I thought, who is this guy? But he was serious, though it took us quite a while, til 2000, to make In Search of Mike. It kinda sat around on various funding bodies’ desks. It didn’t quite fit the model of what short films were at that point.

Did it involve dance?

I’d basically eliminated the dance element. There’s one little dance piece in it. Up to that point Andrew had made short films, using sound and movement, and music videos and he wanted to branch into dramatic storytelling. He liked the material and thought this would be an interesting way to go. He hooked me up with a computer for the first time and I wrote a script. I wasn’t quite sure what I was doing but he got me through it. In Search of Mike was a big hit. It did really well, sold overseas. We even made a bit of money, which is unheard of. And it actually made the funding bodies take notice. First they weren’t going to fund it at all…then [someone] called us and said, “This is fantastic. Ask for more money.” It was completely surreal. I took all the choreographic elements out [which meant] we were left with the kind of harsher elements of the story which I didn’t feel did my mother much justice. It was a very ‘rough’ piece.

My mother was quite ill at the time. I loved our relationship. I thought it was a great, full relationship. It wasn’t easy but it was rewarding in so many ways. And I just thought, hang on…So I wrote a novel and Andrew read it and optioned it. As the screenplay was nearing production, it really separated quite strongly from the book. The book is quite epic.

The necessary economising that comes with a screenplay.

Yes. Characters went flying out of it—all that stuff. So, 1995-2010, for 15 years the story has been kind of shifting through various media and forms.

developing the script

I wrote a first draft and got money [from Screen Australia, then the Australian Film Commission] to write the second draft. Then after another two drafts, it was accepted into the FTO’s Aurora Script Development initiative. So we had a year focusing and that was the stage that was meant to bring it up to finance-ready, and it did.

Was Aurora helpful?

We had a good year. It worked really well for us. Not that it gives you any answers. It just ups the ante around the film, it shifts your thinking. And it brings a lot of interest to bear on it, which causes you to lift your game as well. As a new writer it really made me feel I had business doing it because, you know, Gus Van Sant was there giving me feedback, and John Sayles and Alison Tilson. It was really confidence-building because they liked it. They thought it had lots of potential, which was the reason it was there.

structure and emotion

What kinds of issues were you addressing in script development?

The real shift that Aurora made was that the script had been a black comedy. At that point it shifted to really bringing up the emotional core of the characters. That was really satisfying to me. It kind of went back to why I wrote the book, which was to bring more depth into what the relationship initially was. They helped mine that.

Geena Davis, Accidents Happen

The gradual tonal shift in the film is very interesting, from grimly comic to deeply emotional as the repressed grieving opens out.

It was a real challenge to mix that and to varying degrees of success. People criticise it either way. It’s a tough little balance to get. I think what little tragedy unfortunately I’ve had in my life has been the source of quite amazing humour. How we deal around those extremes of existence is quite broad.

Gloria (played by Geena Davis) puts up so many shields about grief that at the funeral, she’s asking [about the overweight dead man], “What did he do, eat an ice cream truck?” She’s so good at insulating. Then after the wake she breaks down. That wall is such a façade. The trick with her is to find the humour that’s a weapon, but mostly it’s a shield. It’s what keeps her from falling to bits.

So the structure was constantly being addressed so you could get closer to this depth?

And the whole causal effect that really starts to kick in in the film, once the boys make up lies about where they were—it all starts to unwind.

location, location

We were really keen to make the film in America because it’s an American story. It appealed to our sense of adventure and enterprise to do it there. But then, upon investigation and very close to production, the fringe costs and the labour costs and travel costs just blew the budget to such a degree that the percentage of the budget that was actually going to make it onto the screen was so minimal compared to what was going to be spent. Then we talked about, well, can we do it here? You know, there have been enough films made here, set in America, that we have the infrastructure to do it. When we started auditioning, we discovered the kids’ American accents were much better than the older actors. They grow up with it now. So it became an interesting possibility to do it here.

And that was embraced, was it?

It was a hard fight because you go back to funding bodies [who ask] “Why are we making it here? Why are we funding the second-best version of this film, the best being one made in America?” Fortunately, we’d been down that road and we could say, this is actually the best version because we can put a better quality film on the screen for the budget we have. So that was persuasive. In the meantime, Geena Davis got involved because we had been going to make it in the US and that suddenly lifted the finance possibilities.

It was interesting when we were doing Aurora, part of the process near the end of the year involved a follow-up workshop when actors came in and read the workshopped scenes. We said “just use your voices; don’t try to make accents.” And as they were reading, they naturally went into the American vernacular. There was something about the language for them to feel true doing it, they needed the accent. And many of the set pieces, whether about the bowling ball, the baseball, the drive-in, felt much more American than Australian iconic. We had to find the last drive-in in this country to shoot the film in! Then when Geena became involved, we thought well, we’re not gonna have her doing an Australian accent. That would be silly. She jokes that she came over here and her Australian accent was so bad everyone else had to learn American accents.

We got some private money. A British company called Bankside [also handling international sales] and quite a new Australian film funding group, Abacus Film Fund—we’re the first cab off the rank for them.

the re-writing mindset

Were you still writing at this stage?

I was writing right up to production. As it gets closer, all kinds of budget considerations come into play, location and scheduling issues happen. “We can’t afford to go to that location. We have to travel too far. The schedule doesn’t permit it. We need to combine those scenes.” All that stuff. But as a story it was settled.

You didn’t find this stressful?

No, there were so many changes over the years for various reasons and, because it had changed form, I was used to it. My promise to myself was that at any point the challenge wasn’t to change it but to make it better, to accommodate the change. I really feel I was able to achieve this. Even though we had “You can’t go there” and “We have to chop that scene.” It’s like, okay, well how is that a blessing?

When the film was being shot, were you present?

I visited very sparingly. That’s the kind of culture there. It was difficult, but prior to filming I had a great deal of influence really, during casting and location decisions and design.

the writer as collaborator

Andrew and I have a long history, and I was the resident American, the ‘expert’ if you will. The autobiographical nature of the film has been played up, but it’s a fictionalised memoir to a ridiculous extent. But there’s a basic truth to it because elements of it bleed through in terms of the basis of some of the characters. It was important that I have an input into the casting, to really understand and to secure the right people. So I was really lucky. Writers don’t normally get that kind of influence. They’re usually kept to the kerb.

What about in post-production?

Back into the game again. I was giving notes on picture edits, sound, music and marketing—I had a hand in some of that. So from one film, I’ve got a pretty broad knowledge of how the system works.

the dancer's vision

What did your experience in dance and other performance bring to filmmaking?

Over the years I’ve directed shows and had dance companies so I’m used to the production role and working collaboratively. Dance is the great collaborative artform, particularly contemporary dance. Film is also incredibly collaborative. But I think on the dancer level, the great evolution of dance over the last 30 years has been the empowering of the dancer and their artistic expression.

Rather than being the tool of the choreographer. So is dance still a part of your life?

I still perform with Chunky Move when they do Tense Dave. Hopefully they haven’t retired it because I think it still has legs. We had a month in New York with it at one point and a couple of small tours around the States and around Australia. I teach contemporary technique at Sydney Dance Company, and stretch classes and yoga around various gyms. I make my living in a very physical way. The writing is new. I’m still trying to get the novel published and that could finally put that story to bed and I can move on.

Is there a relationship between writing and choreography?

Well I’ve had two writing experiences, one is the book which was very solitary, with the occasional agent or friend’s feedback. The film screenplay has continual feedback, weekly. Both work really well. I really like the collaborative element with the film. It’s how I’m used to working historically. As a dancer, you’re constantly criticised. It’s just part of how it works. So I kind of fell into that. It’s nice having that energy. I’ve read thousands of books but I hadn’t read many screenplays, so it was nice to have that support in terms of the language. I discovered I’m quite good at imagining what something is going to look like on the screen. Being a choreographer, I’m used to seeing visual images. So it played into one of my strengths.

You know when words are not needed.

That’s one of the things that dance has taught me, the power of an image and that the whole comprises many things, not just a performance. There’s a soundtrack, there’s lighting, the composition of each scene. So I intrinsically understand that and know that all the pieces make the story.

film or dance?

The film adventure came along and it was very seductive because suddenly there was all this support and interest and funding and I got swept up in it. At the same time, the dance world was really difficult to penetrate for me. Funding was impossible without going through years of development funding and all this step by step funding. I’ve been doing this work for so long, I’m just not interested in that. I’m a mature artist and I want to make work. And I’ve applied in the past and I got so discouraged because the whole process of asking for funding actually encourages you to lie. And that’s just no way to start an artistic contract. Or if not lie, to fantasise about “What do you hope to learn?” If I knew I wouldn’t need to do this. “How will it benefit the community?” “Why do you want to work with these people?” Well, because they’re fantastic and brilliant and they’ll inspire me and they’re people I want to spend time with.

going deeper

Lastly, I'd like to come back to what you were saying about moving the script away from black comedy into more something more deeply emotional.

That actually brought me home in terms of what I wanted to achieve with the relationship between mother and son and the power of Gloria, who is ball-breaking and totally devoted at the same time.

Did Geena Davis live up to your expectations?

The great thing about Geena is that while the role is at times so unpalatable, she brings a history of likeability. So you cut her a break because you can’t help but like her. She’s adorable. So you go, okay I’m gonna stick with her.

Conversely, Billy appears likeable, but when he starts lying and covering up, if sometimes from altruistic motives, you think that perhaps Gloria's right, that he's selfish, or heading that way. But that's unfair and her wit is cruel: “I’d always hoped you’d amount to something. Maybe I wasn’t specific enough!”

It’s like he doesn’t know quite how to be bad. It’s like the scene with him and the girl next door, Katrina, with the cigarette and the kisses. They’re both trying to act up but they don’t really have the DNA for it.

When Gloria asks Billy about remembering his dead sister, he confesses to a blank—until he’s made to think about it. This amongst others of the later scenes adds considerable depth of feeling.

It was one of the struggles. Early in development, they wanted me to lose Linda altogether. She’s one of the ones I fought for. I thought poor Linda has never been grieved for because she’s been eclipsed by this person, Gene, who’s in limbo, keeping the family in stasis. The double grave is half-empty, waiting for him.

next: the american market

How is the US distribution of Accidents Happen being handled?

That’s the next hurdle, which will happen sometime late their summer. At the moment, we’ve negotiated a couple of screens in major cities and a 12-city tour of Australian films, with Accidents Happen being the headline film. The cinema release will allow Geena again to do publicity tours. Two companies have been contracted in the US, one does the theatrical release and the other is doing ‘movies on demand,’ which is the new basic avenue for getting independent films distributed. It comes via the internet to your TV. It eliminates all the costs of cinemas and prints and publicity. Hopefully it will allow a return somewhere down the line and allow the film to find its own audience.

For more on Accidents Happen see the RealTime+OnScreen review and go to http://www.accidentshappenthemovie.com/; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accidents_Happen

This article first appeared online April 27

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. 18-19

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

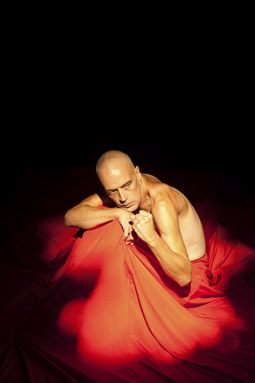

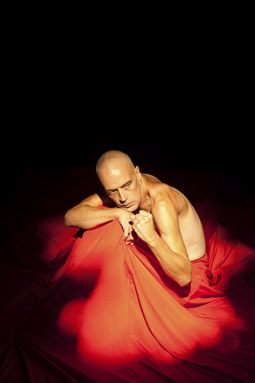

Dante's Inferno, Zen Zen Zo Physical Theatre

zen zen zo: dante’s inferno

Zen Zen Zo's engagement with the classics has included intensely physical realisations of Dracula (see RT80) and The Tempest (see RT92). Now it's The Inferno, the first part of The Divine Comedy by mediaeval Italian poet Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), a wonderful opportunity for the company, in a long line of artists across the centuries, to conjure its own images of Hell.

I asked Stephen Atkins, associate director with Brisbane's Zen Zen Zo, why the company had chosen The Inferno in particular. He explained, “It's been on the backburner for the directors for a number of years and fits the trademark image of the company—the naked form of the human body, images of the grotesque, but always alluding to hope and light in the darkness. That's their performance aesthetic and it really does parallel the content of Dante's poem. The company has tackled classic texts for a long time and they work especially well with physical theatre of a visual and edgy kind. It's a perfect fit. When I came over here from Canada in 2007 to do an internship they asked me to come back and eventually do The Inferno.”

The press release for the show says that The Inferno will be re-imagined in terms of modern Australia. Atkins explains how this transposition is being achieved: “It's done through reading the heart of the poem. It's a secular poem, one of the first ever written in the new language of Italian instead of Latin and was meant for the common man. It's also a political satire, a dark criticism of contemporary Florence. Dante was a philosopher as well as a poet, had many political enemies and a stern point of view, opposing corrupt clergy including the popes. However, a literal transposition that would include the personalities he criticises would have been alienating for a contemporary audience.

“We have taken Dante's concept—the geography of hell, each one of the nine circles punishing more progressively serious sins—and transposed this to our society but with a wry sense of humour, an edgy cabaret sense in the way that Weill and Brecht could make fun as well as poke fun. It's not the poem so much as its shape, although there are condensed sections guiding the viewers through the performance. The audience is going through the same hell as Dante, but 700 years on.”

I ask if the audience will have a guide—Dante has Virgil. “Yes, but updated,” says Atkins. “Dante's text is not very theatrical and a bit like a travelogue, so our guides are tour guides.”

The Divine Comedy is secular is the sense of being written in the vernacular, but it is deeply religious. How, I wonder, will the viscerality of the mode of Zen Zen Zo performance capture more than the punishing torments of Hell. Atkins replies, “Hell is a place of punishment so that performance aesthetic of viscerality and visual impact is very present in our production. But also Hell is a just place where punishments fit the crime. Also, people arrive there from their own choices and a misguided sense of self—they're not sent there by an authority. I think this is what makes it appealing to a secular, humanist audience—it doesn't follow the popular idea of Hell, of the devil on a throne dishing out punishment. According to Dante, Lucifer is the most punished person. If Hell is created by people from their own choices, the light at the end of the tunnel is that we have the keys to our own well being. So we must have the courage to go deeper into dark places in order to come out.”

I ask Atkins to describe something of the performance. He chooses The Circle for Heretics scene: “These are the followers of false wisdom and the corrupters of beauty, meaning of creation. The circle is one of the most severe in upper Hell. Where we have tweaked it is through using images of the distortions of the beauty industry—plastic surgery and the bodies beautiful of models—and what it does to people's self-esteem. These are projected onto the bodies of the dancers. In each of the little vignettes in the work we see the core of the misguided soul and what brought them there. We also see that the soul is unable to get itself out of its state and see beyond. We don't just want to see people being punished—it's about falling into states without examining them.”

I'm curious if, with his large-ish cast, Atkins can also capture some of the epic scope of Dante's Inferno. “The original has images that go from horizon to horizon, with millions of souls,” says Atkins. “But we'll concentrate more on the ideas and the emotional journey through each of these hells. I've tried to incorporate the scale with a couple of large numbers with the entire cast of 19. In the middle of the show, which we have nicknamed “the feeding frenzy”, the whole cast is choreographed by one the company's core members. Dale Hubbard's musical score for the work is as rich and varied as the visual influences from Dante's poem, from swamps to flaming deserts to ice cold wasteland.”

The Inferno will be performed in the heritage-listed Old Museum Building in Bowen Hills, Brisbane offering the audience a distinctive journey through the circles of Hell. Atkins says that circularity is important in the work, “Many of the stations we're setting up are circular.”

Stephen Atkins is the director of Vancouver's Human Theatre and teaches at the Capilano University, but currently spends half his year in Brisbane as Associate Director with Zen Zen Zo: “I'm lucky. And the art scene here is very vibrant, young and very inclusive and accepting of new ideas. I'm having a fantastic time working with the company and we look forward to a very long relationship.” Zen Zen Zo Physical Theatre, Dante’s Inferno—Living Hell, Old Museum Building, Bowen Hills, Brisbane, May 8-20, www.zenzenzo.com

melbourne international jazz festival

With a theme of “celebrating the common chord”, the festival embraces a remarkably wide range of jazz forms and experiences curated by Michael Tortoni and Sophie Brous in a huge program with 400 performers, 95 events and 20 free concerts, 16 world premieres and 21 Australian premieres incorporating film, visual art, public art installations, forums and master classes.

Famed participants include Charles Lloyd, Zakir Hussain, Ahmad Jamal, Mulatu Astatke, Avishai Cohen, John Hollenbeck, Theo Bleckmann and John Abercrombie. But for those looking for edgier jazz and cross-overs, a variety of spaces in Melbourne Town Hall will be home to Overground which features European improvisers Peter Brotzmann (a festival coup, from Germany), Han Bennink (Holland), Brian Chase (Yeah Yeah Yeahs, USA) with Seth Misterka (USA), My Disco (Australia), Mick Turner (The Dirty Three, Australia); Kim Salmon (Australia); Kram (Spiderbait, Australia), Cor Fuhler (Holland), Kim Myhr (Norway) and Oren Ambarchi, Evelyn Morris AKA Pikelet, Bum Creek, Anthony Pateras, Paul Grabowsky with Sean Baxter (Australia).

Elsewhere on the program The Australian Art Orchestra and Paul Grabowsky will present a tribute concert: Miles Davis—Prince of Darkness. Paul Capsis will perform Songs of Love and Death with the Alister Spence Trio and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra will embrace “the interaction between exploratory improvisation and symphonic music with the Metropolis Series.

At the National Gallery of Victoria, as part of the cross-artform Visions of Sound program, Hybrids & Folklore features The Dead Notes, Hi God People, Joel Stern, Snawklor and Clocked Out Duo working with David Chesworth, in an interactive installation curiously described as “focusing on psycho-folkloric sound-making and improvisation in the natural environment.” The Places In Between features Chris Abrahams of The Necks in an immersive sound and light installation in Federation Square. Melbourne International Jazz Festival, May 1-8, www.melbournejazz.com

lynette wallworth does opera

Among video works for live opera, Bill Viola created enormous images for Peter Sellars' production of Wagner's Tristan & Isolde, and now Australian artist Lynette Wallworth has been commissioned to make works for new opera productions in Europe by major composers. In April, The Netherlands' company De Doelen toured a production of Gyorgy Kurtag's Kafka Fragmente, in which the writers' texts are scored for piano and soprano, with Wallworth's projections as “a third protagonist, a woman making art.” London's Young Vic, in a co-production with the ENO (English National Opera), is currently presenting Hans Werner Henze's Elegy for Young Lovers, directed by Fiona Shaw. For this production Wallworth has created an interactive video installation, responding to the actions of the performers and “inviting the audience to directly engage with the video.” Elegy for Young Lovers, Young Vic, London, April 24-May 8; www.youngvic.org/whats-on/elegy-for-young-lovers

adam geczy performs in gent, belgium

Remember to Forget the Congo is a five-day gallery performance (also webcast) by Australian artist Adam Geczy in Belgium. In a blackened room, he will write in white paint the entirety of Andre Gide's Voyage au Congo, an early 20th century text exposing the iniquity of the Belgian imperial exploitation of the Congo. The consequences live on. Geczy says that although Gide's text has been little remembered it was quite influential when published. The artist describes his action as “simultaneously enact[ing] political and social remembrance of trauma, whilst at the same time being complicit in its repression, since the end result is a white room…a dense palimpsetic residue of words, a skein, that is both beautiful and menacing, acting as both conscience and amnesia.” A performance by Adam Geczy, Croxhapox Gent, May 1-5; presentation May 6-30; www.croxhapox.org; webcast www.ustream.tv/channel/croxhapox

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Beneath Hill 60

photo Wendy McDougall

Beneath Hill 60

“TUNNELLING WAS CONSIDERED AN UNGENTLEMANLY WAY OF CONDUCTING WARFARE, IT WASN’T CONSIDERED HONOURABLE. THE GENTLEMANLY WAY TO CONDUCT WARFARE WAS TO CLIMB OUT OF A TRENCH, OVER A PARAPET AND RUN TOWARDS ENEMY LINES WITH A RIFLE…WITH AN AVERAGE AGE OF 42, A LOT OF THE TUNNELLERS HAD DUST ON THEIR LUNGS FROM THEIR MINING DAYS. THEY WERE SICK AND DYING MEN WHEN THEY WENT TO WAR…AFTER THE HOSTILITIES THEY FADED AWAY VERY QUICKLY.” Ross Thomas, Executive Producer, Beneath Hill 60

Jeremy Sims’ first feature Last Train to Freo (2006) was notable for its intense sense of foreboding. A woman caught on a train late at night, trapped by the cat-like menace of an unpredictable man fresh out of prison and hell-bent on confrontation, the film’s real-time unravelling created an acute atmosphere of fear and isolation, that moment when life suddenly spins out of your control. Producer Bill Leimbach (who directed the documentary Gallipoli: The Untold Stories) imagined Sims might be the perfect director for another claustrophobic tale—but here on an epic scale—about a group of Australian civilian miners, called up in World War I, given two weeks rudimentary training, and sent to the hellhole Western front, to start digging and laying mines under the German-held Hill 60.

With the opening scene—a soldier tying his bootlaces up, adjusting his belt, putting his sword in its sheath—we are introduced to the detail of soldierly life. But mining engineer Oliver Woodward (Brendan Cowell) is not your regular soldier. As a civilian, he (and the audience) are rapidly deposited into the tunnels near Armentières, northern France, 30 feet below, where carrying a candle through the darkness, scuttering about like a rat in a maze, his introduction to the men, as their new commanding officer, is: :I can’t seem to find my way out.”

The men use an instrument like a stethoscope to hear through the walls, catching any sounds that may be Germans digging tunnels themselves, or sinking mine shafts. A young boy, Frank Tiffin (Harrison Gilbertson, outstanding as Daniel in Ana Kokkinos’ Blessed [2009], and starring in Andrew Lancaster’s recently released Accidents Happen alongside Geena Davis), paralysed with fear and alone in the dark, is introduced to Woodward. He says he thinks he hears something. With a tap tap, Woodward reveals to the boy that he’s hearing his own heartbeat. As bombs explode around them and rattle the scaffolding, the men hold their cups of tea steady.

Although the underground world is dank and closed in, at least it’s sheltered from noise and rain. As Woodward surfaces for air, his short walk to the officers’ dug-outs (dramatically realised by DOP Toby Oliver, who also worked on Last Train to Freo and, more recently, David Field’s The Combination [2009]) brings home the true horror of men in the trenches, squirming in the mud and rain, bloody body parts left to rot, the continual sonic assault. An introduction to British officer Clayton (Leon Ford) is a reminder of other Australian classics of the war genre, Gallipoli (1981) and Breaker Morant (1980), with laconic Aussies pitted against the English class system in the shape of officers with little pity for the soldiers they’re overseeing. I wish for shades of grey here, beyond the clichés, some insight into these obnoxious Brits, but it’s clearly the way they were seen by many Australian soldiers—the stereotypes persist.

Harrison Gilbertson, Beneath Hill 60

photo Wendy McDougall

Harrison Gilbertson, Beneath Hill 60

Sims has extensive theatrical experience and his strength as a director is clearly in terms of working with actors, especially the younger cast, and ensuring wonderful delivery of idiomatic Aussie dialogue, which rises above sentimentality or uber-nostalgia and goes beyond the well-worn treads of mateship. Although a fine actor, always exciting on screen, the casting of Cowell, however, just doesn’t quite fit: he’s been through so much 30-something angst (the TV series Love My Way; Matthew Saville’s Noise [2007]) that all the soft lighting and makeup in the world can’t make him a believable lad in his 20s, coveting a 16-year-old girl.

The flashbacks to the Queensland homestead, where he teases and seduces the girl (Bella Heathcote), take away crucial pace from a film trying to recreate the dramatic tension of men risking their lives underground. It’s such a long and complicated plotline that by the time the men actually reach the Hill (the bloodiest battle on the Western Front, along the Messines Ridge in Belgium), where the tension should be peaking, the dramatics have started to soak back into the soil, slowly oozing out rivulets from the mine, like the reluctant pump Woodward sets up in front of his superiors. I longed for the tension created in a similar film caught in confined spaces, Das Boot (Wolfang Petersen, 1091), and think with a more focused script and fewer ‘diversions’, Sims and writer David Roach could have achieved it. He also chooses to focus on two German miners on the other side of the wall and while this could have made a wonderfully dramatic connection between the Germans and Australians, the narrative device too leaks the tension rather than building it.

The men, by tunnelling into the blue clay of Flanders beneath enemy lines, are able to lay enough explosives so that the bang, when it arrives, is the largest that the world has ever seen. Sims does well to give a big budget feel to a film that doesn’t have one, transforming sunny Townsville via a rain machine into the quagmires of France and Belgium. It’s an immensely ambitious project with a captivating story that’s taken 90 years to reach the surface. For the most part, Sims and his strong ensemble cast bring the feature to life with more force than many US action flicks can manage.

Beneath Hill 60, director Jeremy Hartley Sims, producer Bill Leimbach, writer David Roach, cinematographer Toby Oliver, composer Cezary Skubiszewski, editor Dany Cooper, production designer Clayton Jauncey, www.beneathhill60movie.com.au

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. web

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Murray Fredericks, Salt

courtesy the artists

Murray Fredericks, Salt

SALT BEGINS WITH ONE OF THE MOST ASTONISHING OPENING SHOTS OF RECENT FILM. WE’RE ON LAKE EYRE. LIKE THE MIRROR LAKES NEAR MILFORD SOUND IN NEW ZEALAND, WHEN LAKE EYRE HAS WATER, THE SKY REFLECTED IS SO CRYSTAL CLEAR THE JOIN BETWEEN LAND AND SKY MAKES A NEW LANDSCAPE.

A black speck emerges from right of frame. It’s difficult to make out as it glides towards us. An ambiguous image. Like a Rorschach inkblot brought to life. Is it a sea creature? An alien? A two-headed monster? As the speck hurtles towards the screen, it becomes a man on a bike, carting his photographic equipment on a trailer. It’s like he’s cycled down from the clouds.

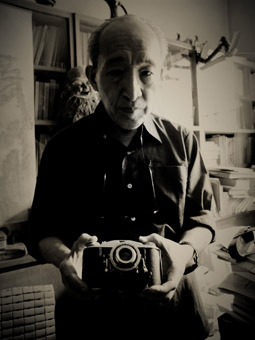

Murray Fredericks is a landscape photo-artist. For six years he has been camping on Lake Eyre (alone for up to six weeks each time, often twice a year) and setting up his tripod, searching for “a landscape devoid of features,” pointing his camera “into pure space.” From 2006 to 2008 he also took a video camera, capturing his day to day musings on art, nature, family, grief and the complexities of surviving as an artist—in a video diary interwoven with time-lapse photography and stunning images of the lake.

Salt, a joint effort by Fredericks and co-director Michael Angus, is an amazingly accomplished short documentary considering the isolation and the difficulties of shooting in various weather conditions on the lake. With no crew on board, the lone Fredericks frames each shot carefully, capturing stillness rather than motion. His monologuing, his intimacy with the camera as we sit in the tent with him, capture his moods, etch into the silent landscape. Fredericks has a talent for words as well as images, and there’s poetry in his everyday observations or in his conversations with his wife on the phone, describing meals (his favourite, porridge, over a camp stove), honestly questioning his art-making or meditating on the nature of self and loss in such an overpowering landscape.

As with the documentaries, Contact (Martin Butler, Bentley Dean, 2009; see RT93) and Night (Lawrence Johnston, 2003, see RT83), in Salt the landscape takes over the frames, dwarfing the protagonist and his tent. Fredericks describes how being completely alone, “to the point where [he] can’t see land any more” for 360 degrees, brings him into a dream state, immersed in a void, where even the smallest sounds—brushing his teeth—become magnified, where you end up “watching your thoughts…like a television.” He drifts into a life of rituals—preparing meals, cleaning his camera equipment, continuing to work at all costs—to fight off the “negative spiral” of depression that nips at his heels, the fear that he’ll surface at the end of the trip with no wonderful images: “Is there anything lasting?”

This short film is elegantly structured with the answer to that question revealed at the very end, after the video camera is switched off. As an artist Murray Fredericks is interested in exploring “why landscapes (or images of them) move people.” His still frames are so subtle, delicate and Rothko-esque they become impossible to forget.

Salt had its world premiere at the Adelaide Film Festival in 2009 and screened in March 2010 on ABC TV’s Artscape program. The DVD can be purchased from www.saltdoco.com.

Salt, director, producer Michael Angus, director, camera Murray Fredericks, original music Aajinta, editors Lindi Harrison, Ingunn Jordansen, sound design Tom Heuzenroeder, James Currie; Jerrycan Films, 2009

This article first appeared online April 27

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. 20

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Tape Projects. 100 Proofs the Earth is not a Globe

courtesy Next Wave

Tape Projects. 100 Proofs the Earth is not a Globe

CONSCIOUSLY OR NOT, ARTISTS HAVE LONG PUT AT RISK THEIR BODIES AND SOULS, AND SOMETIMES THOSE OF THEIR AUDIENCES. THEY HAVE TEMPTED THE DISFAVOUR OF CRITICS, AUDIENCES, GOVERNMENTS, MONARCHS AND DICTATORS AND LOST INCOME AND CAREERS.

For much of the 20th century, risk-taking was encapsulated in the notion of a formally and politically disruptive avant garde. In the 21st century the avant garde has been replaced by a multiplicity of agents for change, now busily reclaiming the right to risk as an aesthetic prerogative, and with utopian potential. Such an agent is Melbourne’s increasingly international Next Wave Festival, for and by young adults, directed, for the second time, by the ever energetic and clear-sighted Jeff Khan.

In an era when the artistic manifesto has been usurped by the business plan and society has become increasingly risk-averse (while contrarily wreaking environmental and financial destruction in the name of the free market), the call to experimentation is growing. If hardly a new concept for the arts, the ways in which artistic risk are being realised are evolving differently from their Modernist avant-garde antecedents. I asked Khan about the kinds of risk entailed in the works in this year’s festival.

The theme of the 2010 Next Wave Festival is, rather grandly, “No Risk Too Great.” It’s easy to say, but who and what are at risk in your program?

People inside and outside of the arts have become increasingly ‘risk averse’ so we wanted to open up a space within the festival to critically look at risk from many different angles, including the micro-management of ourselves and our behaviour in a broader cultural context—OH&S, fear of crime and all of that, which are focused on the individual, our rights, our property. We need to look beyond that in our fraught times, of environmental meltdown, of the big systems which are proving to be untenable. We need to be citizens who can step outside of our own comfort zones.

You’re doing this through art but also through talks and discussions.

Where we can drill down into the subject and address the complexity of risk.

Aesthetic risk?

Every act of creation is a risk—starting with nothing and taking a position. A risk averse culture is contrary to the artistic process putting at risk, in turn, the scale and ambition of artists’ projects.

Since at least the 1970s and 80s risk has increasingly manifested as cross-artform, intercultural and multimedia, entailing new performer-audience relationships and a pervasive engagement with media technologies. What kinds of aesthetic risks are being taken in Next Wave 2010?

It’s definitely about the dissolution of boundaries between artforms, collaborations between complementary and sometimes contradictory practices, and especially the engagement with art in a non-art context. One of the things that most excites me has been a real ramp up, for this festival, in the number and rigour of site works that make interventions into the public arena.

What are the risks for site-specific work?

It’s about making meaningful interventions but it’s also about speaking to a non-arts audience at the same time as to an arts audience.

It takes courage as well, or foolhardiness. Both are aspects of risk-taking.

It’s also about the choice of sites, of public spaces. This year’s Sports Club Project evolved out of using night clubs as sites in the last festival. This time we’re establishing a deep engagement with two sports club spaces: George Knott Athletics Reserve, which is a suburban track and field training facility and the MCG, one of the most iconic sports venues in Australia. To really meaningfully intervene in these spaces with integrity is a huge challenge. The artists visited each venue once a week for six weeks, not only getting to know the architecture, but meeting with the sports people and the stakeholders—sports administrators, little athletics clubs, security guards, operations people—to learn about the function of the space both in an operational and a cultural sense. So the artists’ works will be genuine responses to these sites.

Now they’ve assimilated these places, what will they then do in them?

There’ll be a durational event in each venue over eight hours beginning in the afternoon and comprising roving and spot performances and media art works installed in nooks and crannies. People can come and go at any time and will find themselves immersed in these altered environments.

Immersion, sensory deprivation or amplification, one-on-one performances, mass durational events, unusual locations—these are increasingly indicative of the tasks artists set themselves to attract or challenge audiences, to build them into the work.

Ashley Dyer, And Then Something Fell On My Head

courtesy Next Wave

Ashley Dyer, And Then Something Fell On My Head

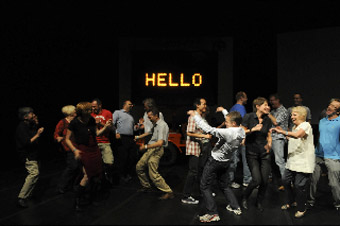

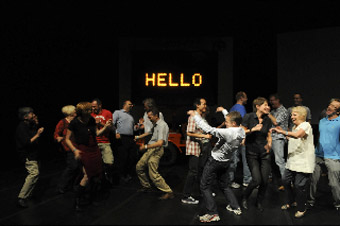

Parts of the program are very immersive, very experiential, like Great Heights, which is staged across Melbourne rooftops. There are performances which are very physically confronting—Ashley Dyer’s And Something Fell On My Head is a full-length performance made entirely of objects that are choreographed to fall from the ceiling of the space towards the audience who are fitted out with safety goggles and hard hats. There are also works where audiences will become participants in unfamiliar places. The Melbourne new media arts collective Tape Projects’ 100 Proofs the Earth is not a Globe is essentially a tour of the Victorian Space Science Education Centre with performance, video and sound, transforming the educational tools. It’s a work that requires the curiosity of the audience as well as a real sense of adventure. A lot of the festival’s projects have a sense of stepping into the unknown.

Mish Grigor, Jackson Castiglione, The Short Message Service

© www.maxmilne.com

Mish Grigor, Jackson Castiglione, The Short Message Service

We’re used to the idea of performers tempting fate, as in physical theatre, but now different kinds of risks are being broached. What about Mish Grigor and Jackson Castiglione in The Short Message Service (a collaboration with Lachlan Tetlow-Stuart and Leah Shelton), where the audience text the performers instructions they must carry out? In performance art this kind of approach has sometimes been physically dangerous for the performer.

The success of the show will depend on the fearlessness of Mish and Jackson and how they handle the SMS commands from the audience. The risk is that the premise could result in something banal or something completely out of control, but what tempers it is that fearlessness and the performers’ incredible proficiency in channelling the instructions into creating situations that are dramatic and spontaneous.

And doubtless their skills at improvisation in interpreting the commands.

There’s such a complicated backend tech and media system which underpins the performance, but what elevates it is the quality of the two performers.

Paula van Beek, Dangerous Melbourne

courtesy Next Wave

Paula van Beek, Dangerous Melbourne

I’m intrigued by Dangerous Melbourne, an advisory session on how to handle the city’s perils.

It follows the format of a community information night and will be presented in a series of town halls across Melbourne where Neighborhood Watch meetings might normally happen. It’s equally a photography and performance event. Paula van Beek’s been doing surveys and research to establish what various samples of the Melbourne population find dangerous about the city. Her photography is a sometimes literal, sometimes abstract interpretation of those fears. People will be given tea or coffee and name tags and a slide show which will accurately represent their fears but also poke fun at big irrational fears in the collective consciousness.

This criss-crossing of fact and fiction is fascinating. Doomsday Vanitas likewise engages with the facticity of fear by being located in Melbourne laneways inhabited by works of art: “sharp, hologram-like projections [creating] a series of ominous still lives” in “a video game-like labyrinth.”

There’s a lovely connection with Dangerous Melbourne here, because Nicole Breedon takes iconography from literature, film and largely computer gaming culture—the icons you ‘collect’ on your visit are everyday objects but become weapons and tools of survival. Both Dangerous Melbourne and Doomsday Vanitas are about being held in thrall by our fears but also about being entertained by them while the world around us melts. What kind of gothic fantasies, for example, will be spun out of the recent volcanic eruption in Iceland?

Managing the growing scale of Next Wave must in itself involve risks. It see that your international project is aptly titled Structural Integrity.

Structural Integrity is the biggest exchange that Next wave has undertaken, with artists from the Asia-Pacific region in residence at the Meat Market. We’ve brought together 11 artist run initiatives and art collectives from across Australia and around Asia. Each is building a pavilion structure to house or represent emerging art in their region. It’s been conceived as a melancholic world fair [LAUGHS] rather then celebrating the values of nationalism. It looks at how grassroots cultures balance their work with their geopolitical position. There’ll be different takes on this. Post-Museum from Singapore are apparently meeting with 20 non-profit organisations from around Melbourne—climate change, anti-domestic violence, arts groups and charities who all believe they can change the world for the better—to organise a collective action which will determine the structure of their pavilion. It’s a utopian collectivity which really reflects the group’s position in Singapore where they support arts projects and live art but also provide a meeting point for activist organisations, as an intersection of art and politics.

The utopian aspect looks like a seriously appealing antidote to risk-aversion.

There’s a strong sense in Structural Integrity of art collectives and artist-run initiatives as providing an alternative social structure. The project is bigger than Ben Hur but it’s looking pretty stunning at the moment.

**********

In a speech about Next Wave 2010, Jeff Khan cited as inspirational the words of French philosopher Simone Weil who in 1943 wrote of risk as an “essential need of the soul,” arguing that “[t]he absence of risk produces a type of boredom which paralyses in a different way from fear, but almost as much.” Next Wave invites its audiences to accept exciting and unnerving challenges—to enter unusual non-art spaces, to become essential ingredients in or agents of creation, to be open to new forms and experiences and to talk risk, in the Risk Talkers program, as well as engage with it as art.

The demands are sometimes epic: Ultimate Time Lapse Megamix is an eight-hour dusk-til-dawn video art marathon on Federation Square’s big screen with works from Australia, Asia and the Pacific. Others are intimate: in Private Dances “audiences will be indulged with a lavish banquet and immersed in a series of private rooms, for one-on-one encounters with some of Australia’s most brilliant young dance artists.” Stranger is Bennett Miller’s Dachshund UN which will “convene a meeting of the UN Commission on Human Rights populated entirely by live dachshunds.” While I Thought A Musical Was Being Made promises “a large-scale performance on the intersection of Russell and Lonsdale Streets that the audience will watch from windows high above the on-street action.” Or you might choose to be spooked in a church crypt by the Sisters Hayes’ A Good Death or find yourself literally inside the performance of Hole in the Wall (RT95). Dive in.

The full 2010 Next Wave program can be found at http://2010.nextwave.org.au/festival/program. Participants in Structural Integrity are: Art Center Ongoing (Tokyo), Boxcopy Contemporary Art Space (Brisbane), FELTspace (Adelaide), House of Natural Fiber (Jogyakarta), Locksmith Project Space (Sydney), Post-Museum (Singapore), Six_a Artist Run Initiative (Hobart), TUTOK (Manila), Vitamin Creative Space (Guangzhou), West Space (Melbourne) and Y3K (Melbourne).

Next Wave Festival, No Risk Too Great, Melbourne, May 13-30; http://2010.nextwave.org.au

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. web

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

We Have Decided Not To Die

2010 MARKS TEN YEARS SINCE THE FIRST REELDANCE INTERNATIONAL DANCE ON SCREEN FESTIVAL. THE EVENT HAS GROWN ENORMOUSLY IN SCOPE SINCE THEN, BECOMING AN INDEPENDENT ENTITY, OUT FROM THE UMBRELLA OF ONE EXTRA DANCE CO AND PERFORMANCE SPACE IN 2008, AND AN EMERGING KEY ORGANISATION THROUGH THE AUSTRALIA COUNCIL IN 2009.

In May, Reeldance will launch its sixth International Dance on Screen festival and tour under the banner “A Collision of Art, Dance and Film”, the first to be curated by new artistic director, Tracie Mitchell who replaced founding director Erin Brannigan in February last year.

Mitchell’s background is primarily as a dance filmmaker. Her career spans over 20 years and her films are in the collections of the Tanz Museum, Cologne, La Cinematheque de la Danse, Paris, and at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne. She is currently completing a practice based PhD at Victoria University, researching new critical frameworks to describe dance for camera. The basis of her work as a dance filmmaker, researcher, mentor and curator is the broad question “What is dance for screen?” and it is this provocation, as well as her interest in process, experimentation, play and deep passion for the form, that she brings to her role as director for this year’s festival.

Mitchell’s program is diverse. Many of the strands that Reeldance has traditionally offered, like the documentary session (this year Paris is Burning and In Bed with Madonna), international shorts sessions and Reeldance International Dance on Screen Awards, are still in place, but there seems a broader sweep of both high end and low budget films, as well as films made specifically by choreographers and more general art films with an interest in the body and movement. Aptly, the theme for the festival is space—physical, emotional, imaginative space and tensions held in space.

The opening night of the festival represents the high end with the films We have decided not to die by Daniel Askill and The Rape of the Sabine Women by Eve Sussman and the Rufus Corporation (which premiered in Australia at the Melbourne International Arts Festival in 2008; RT87). Both have enjoyed wide audiences internationally outside of the dance on screen genre, but Mitchell enthuses about seeing them within the context of the Reeldance festival. Askill is a filmmaker with a strong interest in fashion, and therefore Mitchell notes an interest in the body, movement and composition. “I think what’s so interesting about the film is the subtleties of movement and the intimacy of the camera to be able to express the coming together of those forms, to actually express something with meaning, rather than an audience looking at something going ‘oh, isn’t that beautiful’.”

Mitchell first saw Sussman’s film as an installation in North Carolina and then again in feature film format at the Melbourne Festival, and was excited about how it addresses elements of dance for the screen. She is interested in the ways Sussman holds the tension between people and space, people to people, and to the camera.

The Forgotten Circus

There will be a retrospective of films by UK artist, Shelly Love, who will be attending the festival as an international guest and hosting labs in Sydney and Melbourne. These will focus on the festival theme of space and will create an environment for testing ideas, embracing spontaneity and play without the pressure of an outcome. Love trained at the Laban Centre in London and is among what Mitchell calls the first generation of choreographers to come out of training into the strong dance screen culture in the UK in the 90s (such as the BBC’s Dance for Camera series, South East Dance, Dance Video at The Place) and to utilise such opportunities. Love received the first dance screen residency at The Place and has ‘crossed over’ into making video clips for bands. Mitchell hesitates to use the word whimsy in relation to Love’s films, but describes watching her work as similar to dropping into Love’s imagination. Mitchell is also interested in Love as an artist whose first language is dance, and whose filmic choices are made through this dancerly perception.

Send The Cameras Out will launch the second stage of Reeldance’s Indigenous Initiative, taking place over a three-year period and providing opportunities for Indigenous dancemakers, editors and composers to engage with making dance for screen works. The session will screen six new dance works made over the last year as part of an intriguing experimental process. Each of the six choreographers was given a camera and one month to respond to the questions “What is dance for camera?” and “What is space?” The raw footage was handed to six editors who created a six-minute edit over a month, and then in turn handed the films to six composers who created a score. The screening will be the first time the 18 artists will see the finished works, and there will be a forum for the artists to respond to the project. Mitchell sees this as an initial experiment to begin to build infrastructure for the ongoing program, and there will be much consultation with the artists on where to go from here.

Out of The Hat is another session with emphasis on experimentation and chance, and comes out of Mitchell’s recognition that there is little opportunity for Australian dance filmmakers to have public screenings of their work. Based loosely on the chance procedures of Merce Cunningham and John Cage, artists are able to register their works and at the beginning of the session an hour’s worth of films will literally be pulled out of the hat for public screening. Each artist whose work is shown will be afforded time for public response to their work.

From the Archives will launch the opening of the Moving Image Collection (MIC), Reeldance’s database project initiated by former director Erin Brannigan, archiving the accumulation of work in the organisation’s history over the past decade for public access and screening works drawn from the collection. In conjunction, there is currently a window installation at the Australia Council building in Sydney with 10 screens showcasing works from the archives. This installation will tour to Chunky Move in Melbourne and the Judith Wright Centre, Brisbane as the festival travels from state to state.

Beyond the individual sessions, Mitchell is interested in the overarching concept of a festival. She reminisces about days spent at the Valhalla Cinema in Melbourne in the 70s with a thermos of tea and packet of shortbread biscuits, watching films from morning to night, submerging herself in the filmic world. She speaks of the importance for her as an artist early in her career of attending festivals overseas to “meet, be inspired, critically respond, investigate, network and be fed” and to create the connections she felt difficult to maintain in Australia at that time. Mitchell’s vision for the Reeldance Festival is to provide a platform where artists and audiences alike can immerse themselves in the world of dance on screen.

To increase the sense of national convergence and conversation, Mitchell has created Artbus, two buses travelling overnight from Melbourne and Brisbane respectively with dance film screenings every hour and places for 48 people on each, who will be guests of the festival in Sydney with access to all screenings, forums and talks. Mitchell wants the festival to be not only about screening dance film, but about process and community too. She likens the process of her curation to creating a fabulous dinner party: you meet great people who give you stories; the surroundings are divine; the lighting’s perfect; you are served a degustation menu, with each taste like an amazing adventure; and you leave exhausted with all your senses satisfied.

Reeldance International Dance on Screen Festival; Performance Space, Carriageworks, Sydney, May 13-16. See www.reeldance.org.au for national tour dates: Perth, Adelaide, Alice Springs, Darwin, Cairns, Brisbane.

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. 28

© Jane McKernan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

You Were In My Dream (2010), Isobel Knowles and Van Sowerwine

image courtesy the artists

You Were In My Dream (2010), Isobel Knowles and Van Sowerwine

FOR ITS FOURTH INTERNATIONAL BIENNIAL OF MEDIA ART, EXPERIMENTA WAS FRAMED BY THE LURES AND ELUSIVENESS OF INHABITING ‘UTOPIA.’ AMASSING MORE THAN 35 INTERACTIVE AND SCREEN-BASED WORKS FROM AUSTRALIA AS WELL AS INDIA, CANADA, FRANCE, SOUTH AFRICA AND THE UK, THE BIENNIAL CHARTED MYRIAD WAYS MEDIA ARTISTS TODAY ENVISION THE LONGSTANDING DESIRE FOR A BETTER WORLD. WHILE THE TITLE OF THE EXHIBITION, UTOPIA NOW, LEADS ONE TO EXPECT AN IMPLICITLY HOPEFUL ENCOUNTER WITH NEW MEDIA ART, THE SELECTED WORKS RANGED FROM JOYOUS AND HUMOROUS TO DESOLATE AND UNNERVING.

Prompting us to consider a series of possible futures, the theme of the exhibition parallels the concerns of the sci-fi genre where projections of the future function as anxious meditations upon or inspirational extensions of the present day. For myself, it seemed fitting, then, that entry into the Blackbox space resounded with allusions to science-fiction. After passing through a large inflated white façade—itself reminiscent of the gleaming white cities of hope that once appeared in the design of 19th century world expositions and the futuristic city designs of films such as Things to Come (1936)—we are greeted by a suspended garden, Akousmaflore by the French duo known as Scenocosme (Grégory Lasserre & Anaïs met den Ancxt, 2008). Invited to touch the draping tendrils and leaves of the overhanging plants, we discover that this garden can emit sounds and acoustic vibrations.

Akousmaflore, Scenocosme

courtesy Experimenta and the artists

Akousmaflore, Scenocosme

Akousmaflore brings together the human, the natural and the technological to imply harmonious fusion. The work itself is founded upon proximity and recognition: as flesh and flora connect, the tiny concealed sensors that are lodged within the greenery become ‘aware’ of our presence and trigger varying sonic effects. One wonders, however, whether or not this leafy chorus harbours darker undertones. In the greenhouses of the future, will the hybridisation of nature and technology lead us towards social betterment or destruction? Such questions became all the more pressing when an occasional scream issued from the garden. At that point, the captivating ‘song’ of the plants ceded to the potential for a botanical uprising—perhaps along the lines of John Wyndam’s novel, The Day of the Triffids (1951)—and I chose to move on.

I Feel Cold Today (2007), Patrick Bernatchez

image courtesy the artist

I Feel Cold Today (2007), Patrick Bernatchez

One of the most compelling features of the biennial was its notion of a future still to be decided, through a rhythmic alternation between ominous and optimistic scenarios across the assembled works. Thanks to Sir Thomas More’s Utopia, published in 1516, the idea is commonly understood as the dream of an ideal society or a perfect world. If utopia is an age-old ideal that speaks to our sun-dappled dreams, then Experimenta rightly chose to pay heed to the aesthetic complexity of its curatorial premise by showcasing the prospect of utopias lost as well as found. Alongside the more humorous artworks of the exhibition—for instance, were video shorts that elicited our laughter through the dissonant and the absurd, such as The Hunt (Christian Jankowski, 1992/1997) in which a man, armed with a toy bow-and-arrow, enters a supermarket and deftly spears supplies (bread, milk, a frozen chicken) with child-like abandon, before proceeding to the checkout—are works charged with nightmarish visions of dystopian chaos. To that end, the elegiac I Feel Cold Today (Patrick Bernatchez, 2007) presents us with the darkened flip side of utopian rationality and order. At once beautiful and imbued with a palpable sense of mourning, the work journeys through floor after floor of an abandoned office building, gradually filling with snow. Instead of people, its scenes are filled with office chairs and windswept paperwork. All that is left of capitalism and economic industry are its vestigial remnants, soon to be covered over by a blanket of post-apocalyptic snow.

Shadow 3 (2007), Shilpa Gupta

courtesy Experimenta and the artists

Shadow 3 (2007), Shilpa Gupta

Often, it is difficult to separate out the ludic appeals of the works on display from their darker portents as both utopic and dystopic possibilities reside within the same piece. Consider the affective implications of the Indian artist Shilpa Gupta’s large-scale interactive installation, Shadow 3 (2007). What begins as a playful scenario in which the visitor’s shadow is projected life-sized before them gives way to an unnerving ‘string’ that steadfastly attaches itself to our silhouette. Whereas beforehand we had controlled the actions of our shadowed selves, now detritus begins to slide down the string and affix itself to our shadow. Shadowplay animation leads to our own uncanny automation for we cannot halt the accumulating pile of debris. Eventually, our shadows are overcome by a tidal wave of junk, drowned by the rubbish.

Utopia (2006), Cao Fei

image courtesy the artists

Utopia (2006), Cao Fei

Alternately, Cao Fei’s mesmerising film, Whose Utopia (2006), posits that utopia is where you make it. Set within a light bulb factory in Guangdong, China, Fei’s film entwines scenes of factory workers engaged in mundane and repetitive tasks and the escapist fantasies of four workers. Shots of a ballerina’s poised gestures alternate with images of a man break dancing in the aisles or another man absorbed in strumming an electric guitar, while the drum of industrial machinery, the regimentation of work and the stark lighting of the factory floor persist throughout. Sometimes, utopia is found in the most unlikely or gloomy of places because this is a concept that is tethered to individual hopes and dreams.

Without question, the stand out work of Utopia Now (and a definite crowd favourite) was the Isobel Knowles and Van Sowerwine commission, You Were In My Dream (2010). As the artists so adeptly prove, even the utopias belonging to long since past traditions of art and entertainment can be discovered again and revitalized anew, within the ‘new media’ sphere of technologically augmented art. You Were In My Dream is a glorious stop-motion animation that recalls media art history from the vantage point of the present. Functioning as equal parts perspective box, reflective display and interactive installation, the visitor is seated at a booth and provides the stand-in face for a child protagonist (fed live into the animation). Equipped with a mouse, we are prompted by the appearance of sparkles on-screen to select our chosen path/storyline within an enchanted forest. The densely textured world of You Were In My Dream consists of hand-cut paper human and animal characters, delicate feathers and fronds–demonstrating how such material still persists within the age of the digital. Unlike the traditional perspective boxes of earlier periods of history, however, this work is not confined to a single-user experience. Indeed, the crowds who gathered around the piece seemed just as transfixed by the exterior projection on the side of the wooden box as I was by the world unraveling within it.

Similarly, William Kentridge’s What Will Come (2007) opts to retell the historic atrocities of the Italian invasion of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) through the forgotten media art of the anamorphosis, projecting the ‘real’ story of these events upon a cylindrical surface that dates back to the seventeenth-century. Life Writer (Laurent Mignonneau & Christa Sommerer) also merges the analogue and the digital: you sit at a typewriter, press the keys and the letters generate different codes that result in insect-like creatures swarming across the projected page. The combination of code and artificially-generated creatures from an older mode of writing seem entirely apposite—it is well known that cyberpunk author William Gibson first conceived of the birth of cyberspace from the purview of his own typewriter.

While many of the works contained in Utopia Now do function as somewhat like one-trick ponies—have your digital portrait taken and watch yourself aged via face-reading and morphing software; press a button, hold yourself against a glass panel and see yourself transformed into a suspended, full-body scan—this should not be taken as criticism. Arguably, much of the strength of Experimenta’s Biennial stems from its negotiation of old and new technologies. To that end, I am reminded of what the early film historian Tom Gunning refers to as the pre-1910 “cinema of attractions” as it invoked a presentational rather than representational experience of film and one that directly addressed the spectator. Towards the conclusion of the short digital animation, Please Say Something (David OReilly, 2009), another favourite of mine, a complicated cat and mouse pair steps forward to take a bow and allude to our own appreciation of the display. This is the great strength of the Experimenta Biennial—its deliberate inclusion of the visitors themselves as embodied and vital participants within the artworks.

Decades on from the techno-utopianism that accompanied the beginnings of digital culture and new media art (what the cultural critic Scott Bukatman aptly terms “cyberdrool”), Experimenta continues to bring together old and new technologies, to suggest that no medium ever completely disappears, and invites us to have fun along the way. This biennial might not have been utopia attained but, at times, it did function as an enthralling place to visit.

Experimenta, Utopia Now: International Biennial of Media Art, Blackbox, The Arts Centre, Melbourne, feb 12-March 14

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. 27

© Saige Walton; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

(Not) a Love Song

photo Valério Araújo

(Not) a Love Song

WHAT IS IT ABOUT RIO DE JANEIRO THAT MAKES EVERYBODY GO WEAK IN THE KNEES AT THE MERE MENTION OF ITS NAME? IT FEATURES IN THE TOP 10 MOST DANGEROUS CITIES IN THE WORLD ALMOST AS OFTEN AS IN THE MOST BEAUTIFUL. THIS HAS NOT DIMINISHED ITS ALLURE. SO WHAT DOES AN ANNUAL DANCE FESTIVAL IN THIS MOST GLORIFIED OF CITIES LOOK LIKE?

Founded in 1993 by choreographer Lia Rodrigues, Panorama Dance Festival is currently headed by artistic directors Eduardo Bonito and Nayse Lopez. Now in its 18th year, Panorama has developed into one of the most important platforms for contemporary dance in Brazil, if not in all of South America.

(not) a love song