Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Diana Doman, Josie Petersen, Kerry Carlson, 1980, Love Lust & Lies

GGILLIAN ARMSTRONG’S MOST RECENT FEATURES, DEATH DEFYING ACTS (2001) AND CHARLOTTE GRAY (2008), HAVE BEEN FIZZERS, FULL OF BIG IDEAS AND CASTS, BUT LACKING THE CAREFUL SCRIPTING AND ATTENTION TO FINE DETAIL THAT MADE HER EARLIER WORKS, HIGH TIDE (1987) AND MY BRILLIANT CAREER (1979), SO MEMORABLE. HER RECENT DOCUMENTARY-MAKING IS ANOTHER STORY.

Unfolding Florence: The Many Lives of Florence Broadhurst (2005) was a wonderful unravelling of the demise of its subject, a luscious experience where style met substance and the audience swooned. Armstrong’s new documentary, Love, Lust & Lies (2009), is more down-to-earth but just as dramatically satisfying, the latest episode in a social-realist experiment that began in 1976 with three 14-year-olds—Kerry, Josie and Diana—plucked from an Adelaide youth centre, to talk to camera about their lives, dreams and hopes (Smokes and Lollies, 1970). Armstrong continued to check in with them at ages 18 (Fourteen’s Good, Eighteen’s Better, 1980 ), 26 (Bingo, Bridesmaids and Braces,1988) and 33 (Not Fourteen Again, 1996). Love, Lust & Lies meets the women in 2009, now at age 47.

In choosing a number of subjects to track through their lives Armstrong took on a challenge similar to Michael Apted in his Up! series, commencing with 7 Up! in 1964. Apart from satisfying your curiosity, seeing how the girls turn out and whether they realise their ambitions—with apparently limited resources—it’s also an opportunity to see how Armstrong reveals herself, how she has matured as a filmmaker. Her willingness to be present within the frame, to answer questions, engage in dialogue about the process, sets her apart from Apted, who remains very much the clinical observer. It’s also made very clear that Australia is not a classless society; her subjects do not have the same opportunities as Armstrong and there’s a sadness for everyone in this realisation.

Kerry and Josie tell Armstrong plainly they don’t want to watch the earlier films, that they “choose to forget,” concentrating on moving forwards. One of the limitations of the series’ format is that Armstrong spends a great deal of time looking backwards over the women’s lives. While good to have a recap, it’s slightly frustrating to spend so much time back then, particularly when I suspect most people seeing the film have seen the others too. I was also curious at first as to why Armstrong spent so much time talking to their daughters rather than the women themselves, as if pushing them out of their own film. But when Josie later says, “You don’t stop parenting when you’ve had your children. Parenting goes on for generations,” I understood the sophistication of Armstrong’s technique. Ultimately the film is not about three women any more; it’s about the legacy of motherhood. Josie and Diana are still struggling with relationships, with children, with deceit—both had absent mothers. Kerry, who had loving parents, knows how to treat her husband (and her own ideas) with care and respect; everything about the interviews reveals a couple in love.

Josie Petersen, Diana Doman, Kerry Carlson, 2009 Love, Lust & Lies

What’s fascinating about this particular instalment is how the stories of children and grandchildren (some now adults) start to reveal the web of lies and intrigue previously woven by the women in earlier episodes. There are dramatic revelations of lies told, not only to Armstrong and her audience, but within the families themselves—lies crucial enough to have destroyed the fabric of their lives. You suspect the women were often lying quite successfully to themselves, too, at the time, and it’s intriguing to reconsider former interviews from this perspective; fresh faces seen in a new light.

The other unavoidable comparison is between 14-year-old girls then and now. While the central themes remain the same—obsession with boys, becoming body-conscious, rebelliousness against parents—there’s no trace here of the contemporary world: mobiles, the internet, email. Back then, after her mother abandons the family, Josie serves her father and brothers food kept warm in the oven, automatically assuming the mother’s role at age 14. The girls are just on the brink—about to negotiate the first wave of feminism—but at this point their options seem so limited: get married; be a secretary; study to teach. As a father says, “A girl can get in a lot of trouble, a boy can’t.” The girls don’t question this. For their daughters, the options are seemingly enormous (the army, being a pilot) but that doesn’t change a great deal in this century—they too end up with limited education, often deadbeat, controlling men around and early pregnancies; the cycle continues.

Apted’s series, now available on DVD, hasn’t quite lived up to expectations, refusing to question its own currency and adapt with the times. Participants suddenly disappeared without notice (I’d spend the whole episode worrying about them: were they dead? just not interested? fed up? in a mental institution?). It was hard to tell what they thought of the process; some appeared to hate it. The interesting questions, never asked, were why did others continue to take part, and what impact did their participation have on the shape of their lives? But one aspect of 7 Up! I did like was the way its three female subjects were often interviewed and framed together. It gave them an interesting dynamic, bouncing off each other in heated debate. I often wished we could spend more time with the women as a group—with Armstrong interrogating them on the trickier issues, to see how they presented in front of each other, what they were willing to reveal, the divergence between narratives alone and together. But you get the feeling they have, as many friends do, drifted apart; they remain polite and tentative, probably not the footage Armstrong was really after.

The film ends, as always, on an open note, but it’s hard to imagine Gillian Armstrong will give up here. You yearn to see the women slogging on, into retirement, hopefully realising their dreams of travel and finding a place of peace. And there’s the burning question that remains: I just have to know, will Diana end up staying with Fury?

Love, Lust & Lies, producer, director Gillian Armstrong, producer Jenny Day, original music Cezary Skubiszewski, cinematographer Paul Costello, editor Nicholas Beauman; screening in limited release nationally.

This article first appeared online May 24

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. 20

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Kelton Pell, Geoff Kelso, Bindjareb Pinjarra

IN THE SOUTH WEST OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA IN 1834, FIVE YEARS AFTER WHITE SETTLEMENT, A GOVERNMENT SURVEY WAS UNDERTAKEN IN THE INTERESTS OF PROTECTING THE LIFE AND PROPERTY OF THE SETTLERS. IT CULMINATED IN A BLOODY BATTLE AT PINJARRA IN WHICH THE 21 NAMED BINDJAREB NYOONGARS WERE KILLED. OF COURSE IT WASN'T A BATTLE ANYMORE THAN IT WAS A SURVEY. IT WAS A MASSACRE AND THE BODIES OF MANY MORE UNNAMED BINDJAREB WERE WASHED DOWN THE MURRAY RIVER; ACCORDING TO INDIGENOUS ACCOUNTS BETWEEN 70 AND 150 MEN, WOMEN AND CHILDREN.

One white officer died from falling off his horse. Since then the Pinjarra massacre has been a casualty of the history wars. Back then the Bindjareb were wedged between two landowners: Peel who owned 250,000 acres on the Mandurah side of the river and Meares who had 20,000 acres on the southern side of the Bindjareb. They were squeezed in along the river. This configuration of forces was the basis for the massacre; the Bindjareb had nowhere to go and were mowed down with muskets fired from both banks of the river.

This year is the 175th anniversary of the massacre and it is being remembered with a play, a travelling art exhibition and a website with a podcast which can be downloaded as an audio tour for people who visit the massacre's location. The site is so fiercely contested that the local council still refuses to acknowledge the event or put up signage let alone erect a memorial. So, paradoxically the virtual site, www.pinjarramassacresite.com, is the contemporary historical site.

The podcast was made by the actors who feature in the play, Bindjareb Pinjarra, performed in Fremantle at Deckchair Theatre. This is a revival of the 1994 production. The original performer-creators, Kelton Pell, Geoff Kelso and Phil Thomson, who approached the Pinjarra man Trevor Shorty Parfitt to be the fourth storyteller, have regrouped to honour his memory and pass the show on to three new people, another senior Pinjarra man Frank Nannup and two young fellas—Nyoongar actor Isaac Drandic and Wadjella, Sam Longley. The play must be passed on because it exists as an oral form created from improvisation around the historical records and the oral acccounts of the Nyungars and informed by the everyday as well as present day interactions. The ensemble of six male actors are all agile performers and accomplished improvisers and very funny too, because this play about a massacre is presented as a comedy with a black undercurrent. The humour is always deadly serious. The actors play across age, class and race and play they do so that all the stereotypes are well worked over for comic effect. Its great strength is the depth of story it tells and the quality of the tale tellers. Among them, Kelton Pell and Sam Longley stand out in particular for their ability to take us deep inside the other and find the familiar self beyond stereotype.

The staging is pared back and clear, everyone wears the same costume-uniform, there are few props, no sets, just benches to return to between scenes, and, dominating the space, a mural backdrop painted in the Carrolup style by contemporary Nyoongar artist Lance Tjyllyungoo Chadd whose work features in the exhibition at the old Fremantle Gaol along with 20 other artists. The backdrop is a powerful, atmospheric landscape of big old river gums and grasstrees beside a deep gully and a shaded creek depicted at sunset, conjuring a gothic scenario of ghosts, blackboys and a river running with blood and choked with bloated bodies. It presents a disturbing stillness that can never be read as elegiac once you know the history of the place.

Subtly dramatic lighting played on this painting, animating all its moodiness enhanced by the soundscape which incorporated voices, rifle shots, birdsong and the plaintive wail of a didjeridu. The actors contributed the live sound of clapsticks to punctuate the scenes, drive the action forward, keeping us alert and alarmed, unable to forget what happened. If there was any doubt that the play needed to be revived post-Apology, then what happened to Shorty Parfitt's family on opening night when they ordered a taxi which refused to pick them up, shows that even in tourist savvy, sophisticated Fremantle there are still deep pockets of racism. The story still needs telling.

Bindjareb Pinjarra will tour to The Dreaming Festival June 11-14 June, Woodford, www.woodfordfolkfestival.com/thedreaming, and Brisbane Powerhouse, June 15-17

Bindjareb Pinjarra, created and performed by Isaac Drandic, Geoff Kelso, Sam Longley, Franklin Nannup, Kelton Pell & Phil Thomson; Victoria Hall, Fremantle, March 17-April 3

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. web

© Suzanne Spunner; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

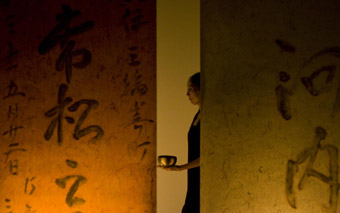

Tatsumi Orimoto, Oil Can, 2010, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art

courtesy the artist, photo Alex Craig

Tatsumi Orimoto, Oil Can, 2010, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art

“IF IT’S ART, IT’S ART,” CONCEDES A BEMUSED PEDESTRIAN AS HE HEADS OFF AFTER BEING MOMENTARILY ABSORBED INTO THE CROWD OBSTRUCTING THE FOOTPATH OUTSIDE THE 4A CENTRE FOR CONTEMPORARY ASIAN ART. IN A SMALL WHITE-WALLED ROOM FILLED WITH 15 GREEN 44 GALLON OIL DRUMS PAINTED RED ON THE INSIDE STAND BLANK FACED FELLOW CITIZENS AND THE ARTIST WHOSE WORK, OIL CAN, THIS IS—TATSUMI ORIMOTO.

In a line outside the window, volunteers await their turn to expressionlessly occupy a drum for 30 seconds. Orimoto purposefully fusses about, directing individuals—it might be five, or 14—into position. When satisfied, he chooses a drum for himself and is helped in using a small step ladder. Once everyone is still, looking forward towards the street, the moment is captured by a photographer perched high on a ladder just inside the window. Then the process begins again, Orimoto creating new permutations for well over an hour.

Outside the crowd grows and, after a half hour or so, an emboldened Orimoto beckons to passersby to join his volunteers, which they willingly do. Meanwhile, chatty observers explain to the newly arrived what they think the work is about: “alienation,” “ordinary people at the mercy of the oil industry,” “people discarded,” A newcomer asks, “Is someone making a movie? “Now there are several other photographers in the room and, outside, mobile phones are held aloft. Moments of stillness, as the latest permutations are realised, alternate with the bustle of selection, arranging and clambering in an out of drums. The sense of occasion is palpable and participation unthreatening. The cultural mix of volunteers, true to China Town (next door is the inviting Polish deli, Cyril’s), is rich and welcoming.

Oil Can suggests much, reminding us of Ham and Clov in their bins in Beckett’s Endgame, sharpening our sense of non-communicative personal isolation (curiously at odds with the conviviality of the crowd and the willingness of the volunteers) and heightening our appreciation of art as its usual complex two-way process—observer and observed—but to which has been added the ever increasing role of observer as observed, through participation and co-creation with the artist. All of this intensifies the sense of ‘everyday surreal’ that Oil Can evokes—pedestrians in their street clothes stepping into the neat rows of drums to have their images captured for purposes that remain unexplained. I look forward to seeing the documentation; doubtless it will be a work of art in itself, offering a more formal meditation, but stripped of the excited hubub of the performance it might mean something else.

Centre 4a’s enterprising program of live performances engages new audiences—surprising them with art while making it simulantaneously part of the everyday.

Tatsumi Orimoto was born in 1946 in Kawasaki, Japan and studied at the Institute of Art, California. In 1971 he moved to New York, where he worked as an assistant to Nam June Paik and was introduced to Fluxus. In 1977 he returned to Kawasaki where he currently lives and works. His performances have been presented in several countries including the Biennale of Sydney, Sao Paulo Biennale and Venice Biennale.

Tatsumi Orimoto, Oil Can, 4A Centre for Asian Contemporary Art, Sydney, May 13

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. web

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

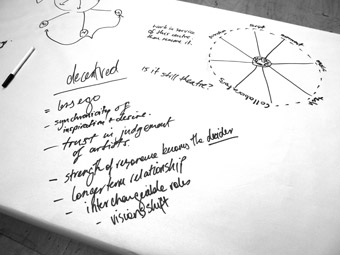

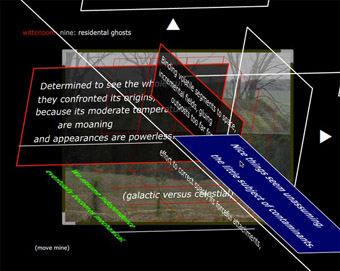

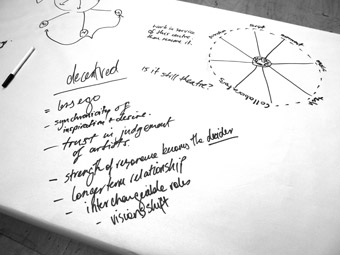

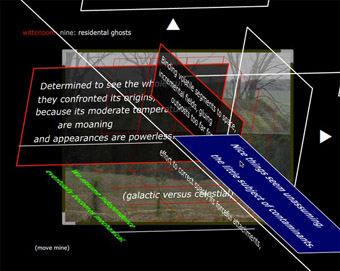

Workshop notes Dramaturgies #4

FEBRUARY SAW THE 4TH DRAMATURGIES SEMINAR ORGANISED BY MELANIE BEDDIE, PETER ECKERSALL AND PAUL MONAGHAN. PREVIOUS MEETINGS FOCUSSED ON THE ONLY PARTIALLY RESOLVED DEFINITION OF 'DRAMATURGY,' ON DRAMATURGY AS A CRITICAL AND POLITICAL PROJECT (“INTERVENTIONIST DRAMATURGY” IN ECKERSALL’S WORDS), AS WELL AS PRACTICAL STRATEGIES FOR WORKING IN A DRAMATURGICAL MANNER.

There were three working parties for Dramaturgies #4: Collaboration facilitated by Eckersall, Diversity by Beddie and Training and Research (the group I joined) by Monaghan. John Romeril noted of Dramaturgies #3 that it had an “experiential emphasis.” with a “learn by doing and observing approach”, problems being addressed “on the floor” and on one’s feet. The decision of Eckersall’s group to present their findings in the form of a space strewn with snaking passages of text, balls of paper, objects, and scenographically arranged mess, reminiscent of artist Joseph Beuys’ perfomative lectures for the Free International University, represented an attempt to blend experiential knowledge (the body, performance, space) with theory and ideas.

Overall though, Dramaturgies #4 took the form of oral discussion. With Richard Murphet playing a prominent role, at times it seemed a festschrift for the former head of VCA Theatre. Murphet’s engrossing keynote reminded us of links between contemporary understandings of theatrical structure and Euro-American developments, as well our indebtedness to the experimental, often nationally-focused, work of the Australian Performing Group and the Pram Factory. Murphet attended US director and theorist Richard Schechner’s infamous production Dionysius in 69, which The Australian characterized as “the ultimate 1960s group-grope show.” Schechner’s ideas on the transcendence of the mundane through staged interactions, in which text, image, design and the body all played a significant role, and which were widely dispersed about a multi-focal theatrical space, helped set the tone not only for much of the material produced by artists like Murphet, but incited Australian practitioners to wrestle with articles on Artaud and Brecht from Schechner’s journal, TDR. Thinking dramaturgically has a long history in Australia, running from Eugenio Barba’s influential appearance in The Drama Review [TDR] through to Murphet’s production of The Inhabited Man (2008; see RT 87, p8).

The working parties at Dramaturgies #4 struggled to find common ground, leading to some “group envy.” In closing presentations, many of the Diversity panel contended that the matter is best addressed as an integral concept, enmeshed within every aspect of theatrical thinking, rather than treating it separately, whilst we in Pedagogy wrestled with how to approach so broad a question as the teaching of the full variety of practices involved in the structuring of theatrical knowledge.

Literary issues of editing, textual analysis, and May-Brit Akerholt’s wonderful keynote on script translation, loomed large, but we broadly agreed that the task was to assist students, artists and the public to “think dramaturgically”—rather than necessarily to become that strange beast, the “company dramaturg,” who is typically yoked to the text. Dramaturgy was seen as a way to think in terms of the structures and tendencies involving space, text, sound, light, time, politics and so on (Barba’s weft or “weave”), all of which are measured, invoked and manipulated within the theatrical scene—and within many social and historical arenas as well.

After much to-ing and fro-ing, Murphet offered a possible systematisation of certain critical aspects of a dramaturgical consciousness, which I gloss below. Universal agreement was never to arise, and I felt there was a reluctance by many to confess how our own constructions of dramaturgical practice were weighted towards post-1960s “performance” and the kinds of neo-avant-garde theatre promoted by Schechner and his successors. Dramaturgies #4 was not just notable for its stellar list of delegates, but also for those not present. Where was MTC, the Australian Ballet, Bell Shakespeare, the Australian Writers’ Guild and other institutions many of us characterise as relatively “conservative”? Eckersall’s proposed “‘national audit’ of dramaturgical practices in and for the sector” could not be fully effected here.

The circle Dramaturgies #4

Dramaturgies #4 rather reflected a partisan (though internally divided) set of proposals for thinking about how theatre is put together and how it relates to the wider world, whereby certain aspects of avant-garde praxis and ideals of social or aesthetic intervention—however modest in form, even if only focused on changing perception rather than political structures per se—would be espoused. Whilst dramatically inflected work was the dominant subject of discussion, dance theatre and at least some forms of performance art could be accommodated by the proposed models and membership. Nevertheless, dramaturgy as a potentially totalising socio-aesthetic critique, as a way of modelling the wider social 'ecology' of theatrical ways of acting and describing phenomena—be these on stage, in the visual arts, in political and social action, of socio-cultural occurrences varying from war to shopping—remains an unexplored challenge.

To think dramaturgically, one must learn how to read a piece of theatre; which I would see as rendering all dramaturgs critics. Secondly, it was agreed that one must have a broad knowledge of all aspects of theatrical practice and construction, running from choreography to lighting, text and so on (there was some debate as to whether one should learn such ideas “from the inside” by doing, or, as in my own teaching, through “outside” analysis). One must be able to think of theatrical composition in terms of its formal elements. Phrases such as “the performance score” were deemed helpful, as were models from music (harmony and dissonance), literature (Homeric structures, the Epic, Aristotelian tragedy, Viktor Shklovsky’s concept of “making strange” or defamiliarisation and so on), visual arts (balance and composition), plastic arts (texture, weight, mass) and—especially as far as my own teaching is concerned—the multidisciplinary pedagogy of director Oscar Schlemmer, architect Walter Gropius, painter Wassily Kandinsky, composers Paul Hindemith and others at the Bauhaus School in the 1920s.

Ian Maxwell from Performance Studies at University of Sydney observed that dramaturgs must know how to “break the hermeneutic circle of the work”, or in Murphet’s terms, to disabuse those “expectations” which the structural rules listed above might impose. Barba and Eckersall have used the terms “turbulence” and “con-fusion” to suggest a similar interplay of order and a deconstruction of that order within dramaturgy. This could involve, for example, sudden transitions from tragedy to farce, or vexing a progression from light to darkness.

Monaghan began with the suggestion that a dramaturg is one who “imagines his or her audience”. Such a generalised concept is broad enough to encompass works where the aim is to challenge and provoke, as well as more humanist ideas of the performing arts as entertainment, as describing one’s own life (drawing-room comedy, for example) and other forms of practice.

Finally, one concept which I would contend is essential to all considerations of art, is an awareness that any and all forms of dramaturgy contain within them a “worldview.” The dramaturg must take seriously ideas about philosophy, politics, the body, religion, ritual, anthropology, race, gender, sexuality and other matters as they pertain to the work and to the world as a whole. To craft a theatrical space is to model the world, society and the cosmos—the theatrum mundi or little theatre of the world which Renaissance scholars extolled. Dramaturgical perspectives have the potential to provide a totalising “gesamtkunstwerk” of culture itself, of politics, the arts and of our relation to these phenomena.

Whilst Dramaturgies #4 did not reach any final agreement on how to impart such a way of conceiving knowledge and experience, let alone what limits to such concepts we might want to impose and under what circumstances, Eckersall, Monaghan and Beddie provided a challenging forum wherein such ideas could be debated. If the only outcome of Dramaturgies #4 was to allow us to listen to theatre-maker and Director of The Centre of Performance Research (UK) Richard Gough’s celebration of the cultural and affective density of objects, then it was worthwhile. Gough confessed that, like many other dramaturgs, he was “drawn to objects that…emerge into daylight from dusty attics, mouldy sheds, damp garages and…junk shops…I liked the patina…the scars and markings of an object well used, of functionality and distress; objects abandoned, discarded, rejected and forlorn.”

Such Duchampian detritus has an already established life of theatrical processes and history, which is waiting to be invoked within new theatrical environments, from the cabinet of curiosities to the stage. Having heard that one of Australia’s most successful dramaturgs, Michael Kantor, announce to delegates he is leaving theatre to take up a more environmentally proactive life, Gough’s words about cherishing of the worn textures of embodied refuse, and of the performative weight locked within otherwise derelict objects, suggested that the full ecology of dramaturgy continues to need careful and sensitive husbandry.

Dramaturgies #4, convenors Melanie Beddie, Peter Eckersall & Paul Monaghan; Victorian College of the Arts, Melbourne University, Feb. 17-20.

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. web

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Heavy Metal Work Orchestra

heavy metal work orchestra

The DeMiXerphone, a new instrument created by Frederick Rodrigues, amazingly allows composers and musicians “to have precise control over the pitch, timbre and rhythmic potential of almost any electrical appliance.” You can see it in action as Rodrigues, Abel Cross, trumpeter Scott Tinkler and pianist Adrian Klumpes perform a work for “a 12-piece computer controlled ensemble of power tools and appliances.” Heavy Metal Work Orchestra, The Red Rattler Theatre, 6 Faversham St, Marrickville, Sydney May 28, 7:30pm; May 29, 7:30pm; May 30, 3pm, www.heavymetalworkorchestra.com

adelaide film festival submissions call

The 2011 BigPond Adelaide Film Festival (BAFF) is calling for submissions for its 2011 program in the categories of feature film, documentary, animation, short film, experimental and new media work. You can download a form, submit online through the BAFF website or visit Withoutabox (www.withoutabox.com), an online film festival submission service. For submission deadlines and guidelines visit the BAFF website at www.adelaidefilmfestival.org. BigPond Adelaide Film Festival, Feb 24-March 6, 2011

Luke Hanna, The Cry, Dance North

photo Ferry Photography

Luke Hanna, The Cry, Dance North

dancenorth, the cry

Dancenorth’s eagerly awaited first full-length work from new artistic director Raewyn Hill is The Cry, exploring “the momentum created by a life of [drug] dependency that sweeps others up in their path. Ultimately, we wish to portray the relentless nature of pursuing recovery and the strength needed to build a life in recovery.” The Cry opened in Cairns, May 21-22, has its hometown premiere in Townsville, June 2-6. and tours to Proserpine, August 13-14. Dancenorth, The Cry, www.dancenorth.com.au

Nic Dorward, YOUTHvsPHYSICS 2009

photo Amelia Dowd

Nic Dorward, YOUTHvsPHYSICS 2009

restaged histories project, youth vs physics

After its Next Wave premiere of YOUTHvsPHYSICS, the Restaged Histories project flies to hometown Brisbane to examine “thwarted attempts to fly” as exemplified by Icarus, Superman and a fictional Soviet cosmonaut named Omon Ra. The company describe the work as “part science experiment and part rock concert” with “two performers, risking life and limb in the name of heroism and entertainment and taking a smart and irreverent look at boyhood and imagination in an attempt to disprove heroism.” Restaged Histories are Artists-in-Residence at Brisbane Powerhouse and YOUTHvsPHYSICS was commissioned and developed by Next Wave through kickstart 2009. The Restaged Histories project, YOUTHvsPHYSICS, Brisbane Powerhouse, June 2-5; brisbanepowerhouse.org

the light in winter, melbourne

The European tradition of light festivals in mid-winter has taken hold in Australia, first with The Light in Winter in Melbourne (see RT84) with a focus on community installations, and then in Sydney with VIVID and the Smart Light Festival in 2009 with an emphasis on innovation (see RT90). The music-oriented VIVID is on again this year (more below) and will be joined again by Smart Light in 2011. Robyn Archer’s 2010 The Light in Winter program involves, community events, forums and leading illumination and digital artists, with a commissioned work from Mexican electronic artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer to be launched on June 4. Read Scott McQuire’s introduction to this artist’s work (see RT89) and you’ll see that the commission is a considerable coup for Melbourne. There’ll be a new interview with Lozano-Hemmer in RealTime 97 -June 11]. For more information about The Light in Winter and the work of Rafael Lozano-Hemmer visit: www.fedsquare.com/thelightinwinter and www.lozano-hemmer.com. The Light in Winter, Federation Square, Melbourne, June 4-July 4

vivid sydney

Last year’s inaugural Vivid festival seemed to appear out of nowhere, but offered some large scale spectacle and intense musical experiences that Sydney’s audiences embraced. This year, the guest curators of the performance program, Vivid Live based at the Sydney Opera House, are the power ‘odd couple’ Laurie Anderson and Lou Reed. They are billed as “bringing Manhattan to Sydney” with a very impressive range of concerts by both established and rising stars such as Rickie Lee Jones, Marc Ribot, The Blind Boys of Alabama, Bardo Pond, My Brightest Diamond and Holly Miranda. There are also artist from further afield such as Melt Banana and Boris from Japan and the Tuvan throatsinging champions Chirgilchin.

Along with individual concerts many of the artists have been programmed together into themed nights such as the Slow Music Night (June 4), and Noise Night (including Australians Oren Ambarchi and Lucas Abela’s Rice屎Corpse, May 31). There is even a daytime concert for dogs in the Opera House Forecourt (June 5). And of course there are numerous appearances by Anderson and Reed including a Transitory Life, a solo retrospective performance by Laurie Anderson; Songs from Delusion with Anderson joined by Eyvind Kang, Colin Stetson and Doug Wieselman; Reed’s Metal Machine Music; New York Genius, photos curated by Reed from the Magnum Photographic Archive; and a range of talks with the curators. There’s also a theatrical offering with The Shipment by Young Jean Lee’s Theatre Company lauded as some of the best and boldest experimental playwriting in America.

Apart from the Vivid Live program, a range of other activities are also gathered under the Vivid umbrella such as the lighting of the Opera House Sails with images from Laurie Anderson, and Macquarie Visions, which will illuminate the historic buildings of Macquarie street with projections. The harbour spectacular Fire Water returns to the Rocks, this time with a Bollywood flavour exploring the story of ship that sailed to Sydney from Calcutta in 1797. Creative Sydney also returns with talks and forums focusing on the local scene (its artists again almost totally absent from the Vivid Live program), which along with X | Media | Lab and the Song Summit offer opportunities to discuss the creative health of Sydney and NSW. Vivid, various venues, May 27-June 21; Vivid Live, Sydney Opera House May 28- June 11; http://vividsydney.com/; http://vividlive.sydneyoperahouse.com

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Eliza Logan, Josh Quong Tart, Vashti Hughes, David Keene, Vashti Hughes Ensemble, The Wild Party

photo Brendon Moar

Eliza Logan, Josh Quong Tart, Vashti Hughes, David Keene, Vashti Hughes Ensemble, The Wild Party

FOURTEEN YEARS AGO THE FOUR-MEMBER VASHTI HUGHES ENSEMBLE PRESENTED WILD PARTY TO SOME ACCLAIM AND SOLD-OUT SEASONS AT THE MELBOURNE COMEDY FESTIVAL. NOW RE-PRESENTED AT THE NEW RAVÁL THEATRE IN SURRY HILLS, THIS JAZZ, CABARET AND SPOKEN WORD FUSION IS FULL OF REMINISCENCES OF BYGONE TIMES, RAISING QUESTIONS ABOUT THE USE-BY-DATE OF SOME PERFORMANCE MODES.

The evening opens with a four-piece jazz band providing mood music in Ravál’s dimly lit and crowded theatre bar, tucked above the Macquarie Hotel’s sports bar. The couple in front of me seems to have the right idea, perched on a plush black, leather lounge sipping a string of martinis. We could have been transported back in time, although the music is without the experimentation, the improvisation, the ‘being in the moment’ that I idealistically associate with 20s jazz bars. Enter the Vashti Hughes Ensemble, energetically forming a tableau vivant, while the band slip into providing soundtrack for the performance. Two men and two women pose in costumes evoking 1920s bohemia, but the men’s incongruous Converse shoes, the careful theatricality of the poses and the exaggerated whiteface make-up hint at a contemporary clowning troupe.

Wild Party is a risqué narrative poem written by Joseph Moncure March in 1926 and banned upon publication. It is often seen as a jazz-influenced precursor to Beat poetry, particularly as William S Burroughs once declared that it made him become a writer. The Hughes Ensemble is fairly faithful to the tradition—the poem being the driving element of the show to which all other elements seem subjugated. It comes to life as the ensemble craft an aural space, drawing together sounds, rhythms and narrative through-line. The story is of Queenie (Hughes), “a blonde [whose] age stood still” and her misogynist lover, Burrs (Josh Quong Tart), “A clown. Of renown”, whose portrayal is strangely reminiscent of Heath Ledger’s Joker. After a falling-out and near bout of domestic violence the couple decides to throw a party. Queenie’s best mate Kate (Eliza Logan) turns up with the handsome Mr Black (David Keene) and Queenie executes her revenge on Burrs by ‘making a pass’ at Black which fast-tracks into a love affair.

Although the four performers each take on a character, their predominant role is as ensemble poet narrator. The fidelity of their recital however reveals the datedness of form and text removed from their original context. Moncure March’s text is less shocking these days and while the ensemble do their best to show off the raunchiest bits, and this is where most of their comedy comes from, the piece grasps for contemporary relevance. Cabaret can still be sexually and politically subversive as in queer performance seen in Sydney, such as Gurlesque and much of the work at Red Rattler. I look hard for this in Wild Party, but I find homage more than anything else.

The whole affair predictably comes to a head with a pistol being pulled from a bedroom drawer. Burrs is murdered and Queenie (now channelling Cole Porter) sings apathetically, it was “just one of those things.” There was little variation in musical tone throughout and the performance was for the most part formulaic. However, it looked like a lot of fun to do, and it’s hard to say a form has reached its use-by-date when a packed house is enjoying it.

Vashti Hughes Ensemble, Wild Party, performers Vashti Hughes, Josh Quong Tart, Eliza Logan, David Keene, Ravál Theatre, Macquarie Hotel, Sydney, March 15-April 3

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. web

© Megan Garrett-Jones; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Brendan Cowell & Peter Helliar, I Love You Too

photo John Tsiavis, courtesy Roadshow Films

Brendan Cowell & Peter Helliar, I Love You Too

FIRST-TIME FEATURE DIRECTOR DAINA REID HAS BEEN A COMEDIAN UP TO NOW (WRITING AND ACTING IN FULL FRONTAL, PERFORMING WITH SHAUN MICALLEF) AND DIRECTING MAINLY TV SERIES, INCLUDING THE UNDERRATED ABC COMEDY, VERY SMALL BUSINESS.

Her debut film relies on star power—Sydney super model Megan Gale strutting the red carpet at the Sydney launch before her first Australian screen role; a wonderfully nuanced performance as always from Peter Dinklage, the sensitive leading man in The Station Agent, and who, according to IMDB, has appeared in both the original and now the US version of Death at a Funeral; and Brendan Cowell, who seems to be everywhere.

Having just surfaced from the muddy mines of Flanders in Beneath Hill 60, here Cowell stars opposite Peter Helliar (who also wrote the feature). His effortless move from upstanding hero in a war drama to scruffy but sexy no-hoper in a romantic comedy shows he’s a truly versatile actor and probably the first choice on most directors’ lists. But stars are not enough. The film eventually suffers from a slowly grinding plot and various romances that never seem to quite blossom.

Brendan Cowell, Peter Dinklage, I Love You Too

photo John Tsiavis, courtesy Roadshow Films

Brendan Cowell, Peter Dinklage, I Love You Too

US director Judd Apatow proved with Knocked Up and The 40 Year Old Virgin that romantic comedies don’t have to be about a man and a woman. It’s the bromance that counts, that awkward and shambolic love affair between a guy and his mates. In Apatow’s work the writing can be crisp, hilarious and sometimes deeply disturbing. Here, Peter Helliar seems to be aiming for the same kind of film (and no doubt a lucrative market) and while he’s created some sharp one-liners and lovably messed-up characters, overall, the writing and pace of the film fall flat. It’s not helped by the unevenness of the acting. For all Megan Gale’s grace and beauty, she is not a natural on camera and her stilted performance highlights the talent of others around her, Cowell and Dinklage in particular. Then again, she doesn’t have much to work with. She’s a model with a heart of gold. Full stop. Helliar also seems to be working in a bit of Love, Actually with various relationship strands he tries to tie up by the end and there’s the lovable quirky family, a la The Castle—I Love You Too has ‘produced for the multiplex’ stamped all over it. You suspect though that Helliar had a darker story in mind and it’s lurking in there somewhere.

The main problem is that the film tries to hide its bromance leanings behind a conventional romance (between Cowell as Jim and Yvonne Strahovski as Alice) that never rings true. Alice sports a jolly hockeysticks Bridget-Jones-accent so grating you wish she would return to London and stay there. The writing of romance is difficult and Helliar appears uncomfortable with it, and the female characters in general. It’s as if he doesn’t really want to let his characters fall in love. He holds them back. The film is much stronger in the scenes where Helliar and Cowell bounce off each other in their insecure manly ways, trying to pick up chicks, arguing at the squash court. By the end we’ve had all the cinematic clichés we can handle bundled into the final scenes: an explanation (as to why he can’t say ‘I love you’); a race to the airport in a taxi, to ‘stop that plane’; a funeral (why did he have to die?); and, of course, a wedding.

At the gala premiere of I Love You Too, the radio commentator on the red carpet was welcoming the stars, saying each time, “Australian films are always so depressing, aren’t they! It’s great that this film is a comedy. It’s a breath of fresh air, isn’t it. It’s not like other Australia films.” But you could tell he hadn’t seen an Australian film for years. Popular Australian comedies (The Castle, Muriel’s Wedding, Strictly Ballroom, Kenny) have been sharper than this, and audiences know what they want when they see it. As Cowell and Helliar left him behind to enter the cinema, he tried desperately, floundering, to give away free tickets and t-shirts to the crowd. But they just weren’t interested—unless they could get a photo with Megan Gale.

I Love You Too, director Daina Reid, producers Yael Bergman, Laura Waters, writer Peter Helliar, cinematography Ellery Ryan, original music David Hirschfelder, editor Ken Sallows, production designer Jennifer A. Davis. www.iloveyoutoomovie.com

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. web

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

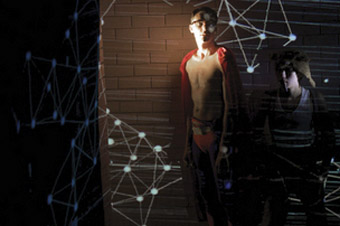

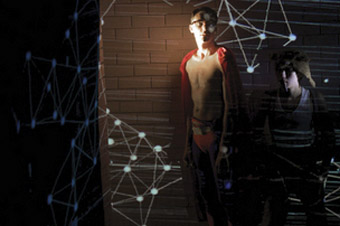

Tom Hall, The Past Will Betray

courtesy the artist

Tom Hall, The Past Will Betray

AS A MULTIMEDIA ARTIST, COMPOSER AND ELECTRONIC MUSICIAN, TOM HALL HAS CREATED WORK CONSISTENTLY REVOLVING AROUND TWO COMPLEMENTARY AMBITIONS THROUGHOUT HIS CAREER—THE EXTRAORDINARY EXTENDING ITSELF INTO THE ORDINARY AND VICE VERSA.

As a musician, Hall’s work within Brisbane-based ensembles like Damon Black’s Secret Birds or his own AxxOnn project has often been defined by the composer’s ongoing struggle to redefine laptop drones and electronic composition as a pursuit as egalitarian and accessible as the electric guitar and heavy metal. The laptop-oriented AxxOnn, by way of example, have spent the past two years performing alongside metal-oriented acts like Boston’s Isis and Seattle’s Sunn 0))).

Hall’s work as a multimedia artist, by contrast, has frequently found him sequencing and re-contextualising tasteful photographs and naturally occurring imagery of mundane environments into transcendental collages of light and sound. His solo compositions as a sound artist, furthermore, echo this approach. Euphonia, Hall’s 2008 collaborative album with fellow Brisbane-based artist Lawrence English, consisted of little more than solitary murmurs of shimmering electronics woven into gorgeous and hypnotic soundscapes.

The issue that has stalked the artist’s entire career has been the effective synthesis of his two perspectives. Hall has shown consistent difficulty in regards to creating a work that unites both ordinary and extraordinary worlds without revealing a clear bias to either. At best, in 2009’s Left of Left installation at Brisbane’s Judith Wright Centre, he has created transcendental work with a strong grounding in everyday influences; while, at his worst (Secret Birds’ earliest collaborative performances), Hall’s various worlds have collided, with violently fractured and disappointing results.

The Past Will Betray, however, has brought Hall closer to a unified artistic vision than any of his previous works. A stylistic successor to Left of Left presented within an almost identical framework, Hall’s most recent installation reveals both a broader conceptual scope than previously and a more refined appreciation of focus and deliberation. The work is officially geared towards exploring the indistinct areas between past and present but, ironically, The Past Will Betray is Hall’s most distinctive and focussed work yet.

A week-long interactive visual exhibit displayed nightly via the Judith Wright Centre’s Shopfront Space windows, The Past Will Betray’s installation component is very much a refinement of Hall’s Left of Left practices. The key difference is, whereas Left of Left consisted of multiple projections layered and dispersed throughout the entirety of the Shopfront Space and glimpsed through its windows, Betray’s visuals are projected directly onto the windows. The work immediately engages more with the public and fosters a greater sense of interactivity—a true joy.

Tom Hall, The Past Will Betray

courtesy the artist

Tom Hall, The Past Will Betray

Visually the exhibit is titillating enough: Hall has expanded his range of austere, distended urban and nature images into colourful psychedelic vistas, effortlessly bathing the Shopfront windows in hues of orange and red without sacrificing the beauty of his more staid imagery. But, in interacting with the exhibit on a physical level, you discover an especially rewarding connection.

Placing your hands on the warm glass of the windows, you can practically feel the work give way to your indeterminate will. The colours, images and ideas almost seem to morph beneath your very fingertips. It’s often difficult to determine how much change is governed by interaction, but the work is a mammoth step forward from Left of Left and a truly thrilling experience in and of itself.

As with Left of Left, the exhibition concludes with a concert performance of work by Hall with supporting sound artists. But this somewhat blemishes the exhibition’s advancements. Whereas Left of Left saw Hall delivering the audio-visual source material of his exhibit over to multimedia artists Lawrence English and Lloyd Barrett to present additional versions of the exhibition’s central premise, The Past Will Betray’s final night doubles as a launch for Hall’s latest solo album Past, Present Below and, as such, proves to be a much more sound-oriented affair.

The performances presented on the night are far from unremarkable—Oren Ambarchi’s deconstructed guitar noise proves fittingly cerebral and Ambrose Chapel’s blend of doom-metal and ambience is intriguing and accomplished while Hall’s lush drones are a particular delight—but the entire event seems like a rather discontinuous and dissatisfying conclusion for such a fascinating exhibit.

Tom Hall, The Past Will Betray, Judith Wright Centre of Contemporary Arts, Brisbane, installation March 18-25, performance March 25

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. web

© Matthew O’Neill; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Alison Pratt, Gethsemane

photo Keith Saunders

Alison Pratt, Gethsemane

IN THE BIBLE, GETHSEMANE IS THE PLACE WHERE JESUS CRUMBLES, FOREKNOWING HIS OWN DEATH, FEELING ABANDONED BY HIS GOD. THE RABBLE WILL TURN HIM OVER TO HIS CRUCIFIXION. THROUGH HIS INTENSELY PERSONAL SUFFERING, CHRIST DOES NOT GIVE UP; RATHER, HE GIVES OVER: PEOPLE WILL DO AS THEY WILL DO. THIS FEAT OF ACCEPTANCE IS PROVOCATIVE AND DEEPLY MOVING.

Gerard Brophy’s Gethsemane follows quite a different trajectory. The five textual passages around which the performance is shaped depict snapshots of life, struggle and death in contemporary Calcutta in a journey across the city from dawn to dusk. The musical form winds and unwinds around these passages. I have an image of spirals within channels of decay—like the labyrinthine passages of this ancient ‘city of joy,’ like a worried angel overlooking a putrefying feast.

Martin del Amo’s first solo dance passage is accompanied by an ascending electronically generated scale which begins in unison but proceeds to divide. His arms and torso—rising, falling, being pulled and propelled—struggle like cells parting ways. The dance becomes thicker, as if spiralling through honey. This is a slow death.

A later dance becomes thinner, sowing its struggles in water, thence becoming brittle, as if broken apart in wind. The Song Company as chorus also works its struggles, shuddering and shuffling in alleyways, trembling as if scattered by internal quakes. A final, jagged scavenging, as if trapped within a thin cylinder of breath, is quieted by the blow of conch horns, sounding the gates of hell (or the other place). The soprano saxophone, a cobra’s dance, calls the final chant; the figures become translucent and turn to their deaths.

Throughout, the choir—always exemplary in their vocal work—is comfortable in its motions; for each member their movement decisions seem entirely in place. The choreography as a whole displays an admirable restraint in tone, letting me sit within the experience.

The weakness for me is in Brophy’s text. Even the Song Company’s website describes it as ‘florid’; as an actor, I would find it very difficult to know how to pitch it. The main issue, I believe, is that it is overwritten, and the narrative of ambiguous disposition—horror? disgust? wonder? Its delivery lies just on the edge of scorn. Even after reading the text and then watching again, it remains very hard to grasp in real time. The imagery lacks tautness and coherence—especially in comparison with the music, which has both these qualities.

The vocal writing is spare, almost plainchant, nodding towards the Flemish masters (Lassus and Tallis) whose lamentations Brophy did not want to imitate, but which recognise the power of sound quality—whether vocal, instrumental or electronic—to carry experience from the deepest chambers of human experience. I am still haunted by several glorious, sparse melodies. Eastern tonalities resonate, without making the mistake of imitation. This work is grounded in the concrete timbres of sound and transcendent of specific geography. It carries a landscape of soul.

By its final moments, I am left strangely opened, yet also closed: moved, worked on by grief, but also strangely neutered. What has happened here?

Song Company director Roland Peelman initiated the project by pointing Brophy to the Lamentations of Jeremiah, where he watches the city of Jerusalem burn. As a prophet, warning his people about the impending wrath of God, he had been reviled and jailed. But Jeremiah’s lamentations as he watches his beloved city fall express an intensely personal grief that is also full of love for the very people whom his God destroyed.

I expect this compassion is what is missing from Brophy’s text. The story, the lecture on the city’s filth, corruption and waste, the finger pointing to its social injustices throughout the program notes, are confusingly angry yet ungrounded, disgusted and yet aloof. What makes us care is the ache in the movement, and the music: simple rising scales with raised fourths and lowered sevenths, played on chimes or bells whose pure and complex timbres sound the world; the electronic aural landscapes that prise space apart; the spiralling motions of the dancers and the dance, the shudder of their struggles against the limitations of the alley and the wall; the struggle to move beyond, but being held back.

Calcutta is not a destroyed city, as was Jeremiah’s Jerusalem. It is teeming, fetid, dangerous, tangled with contradiction, but it is also ‘the city of joy’, full of life. If only this Gesthemane could perfect its passions. I could then sit with its musics and motions and be fired with passion, sorrows and compassion, for all the days of my life.

With thanks to Roland Peelman and Timothy Constable for discussing Gesthemane with me.

Song Company, Gethsemane, concept and music Gerard Brophy, texts Gerard Brophy, plus Bible adaptations, director Roland Peelman, dancer, movement director Martin del Amo, performers Song Company, Synergy Percussion’s Timothy Constable and Alison Pratt, saxophones Christina Leonard, sound design Bob Scott; St Paul’s Church, Canberra, NSW tour, March 21

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. web

© Zsuzsanna Soboslay; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Satsuki Odamura, Wakako Asano, Mayu Kanamori, Vic McEwan, In Repose

photo Jenny Evans

Satsuki Odamura, Wakako Asano, Mayu Kanamori, Vic McEwan, In Repose

PHOTOGRAPHER MAYU KANAMORI, DANCER WAKAKO ASANO AND KOTO PLAYER SATSUKI ODAMURA ARE JAPANESE-BORN ARTISTS WHO HAVE CHOSEN TO SPEND THEIR LIVES IN AUSTRALIA AND, EVENTUALLY, TO BE BURIED IN THIS ADOPTED HOMELAND. THEIR PROJECT IN REPOSE (ALSO WITH SOUND DESIGNER VIC MCEWAN) REPRESENTS AN ARTISTIC EXPLORATION OF WHAT THIS DECISION MEANS NOT ONLY TO THEMSELVES BUT ALSO TO THE MANY JAPANESE WHO HAVE PREVIOUSLY MIGRATED AND DIED HERE.

The In Repose project has been under way since 2007, with a range of performances, exhibitions and community workshops in Townsville, Broome, Thursday Island, Port Hedland, Roebourne and Cossack. In each the group performed a version of ‘kuyo,’ a ceremonial offering to honour the spirits of the dead. This involved lighting incense and pouring water on the graves to slake the thirst of the spirits, and in their contemporary adaptation also incorporated music and dance. In many places this ceremony was opened up to involve the local community while in other smaller locations the acts were more private.

The performance lecture, presented in 2010 amidst the photographic installation at the Japan Foundation, brings these outcomes together. Like Kanamori’s photographs—close-ups of the weathered texture of inscribed rocks, native grasses entangled with headstones—the performance, with the addition of music and dance, offers a more impressionistic retelling of events. It is not overladen with information, but rather offers fragments, anecdotes and space for reflection on the project.

Japanese Cemetery, Broome, In Repose

photo Mayu Kanamori

Japanese Cemetery, Broome, In Repose

What becomes quickly apparent is that there can be no discussion of the Japanese sense of ancestral spirituality without acknowledgement that the graves are on the lands of indigenous Australian peoples. It is the cultural exchange that takes place around this that makes the project particularly interesting. In Broome the connection is most obvious as many Japanese pearl divers married local Indigenous people. In Repose’s title image, taken in the Broome cemetery, shows small, honey-brown hands on a sand-coloured gravestone that Kanamori describes as the “the colour of the skin when Indigenous Australians have children with Japanese.”

On Thursday Island one of the workshop participants makes a short video discussing the local beliefs surrounding death and the passage of the spirit, which Kanamori tells us is particularly resonant with Japanese culture. In Port Hedland, visiting Japanese video artist Shigeaki Iwai wanders over the hill from the graveyard to discover the local Indigenous people. Initially they mistake his tripod for a gun, but then they get to talking and he asks if their ‘mob,’ can look after ‘our mob.’ In the small town of Roebourne, the team discover that the graves they’d been told about have been cleared to make way for housing for the local Indigenous residents. In an impromptu ritual, the team honours the dead, but also passes on the story to the local kids, so that this ‘new’ history may be added to the old history of the land.

Wakako Asano, In Repose

photo Jenny Evans

Wakako Asano, In Repose

The performance itself, is restrained and contemplative. McEwan joins Kanamori as a lecturer, offering the perspective of an Australian of Scottish origin, with gentle wit, and the small moments of banter between them loosen the formal lecture feel. Between the textual vignettes, Satsuki Odamura plays pieces commissioned for the project on koto and bass koto while Wakako Asano dances. There are some beautiful duets, atmospherically lit in the challenging gallery surrounds by Amber Silk. Asano works closely with the rhythmic complexities and ethereal harmonies of the music, and it is always a privilege to hear Odamura’s virtuosity on these wonderful instruments. However while these moments, sometimes accompanied by projected images, offered time for deep reflection there were perhaps a few too many for the structural balance of the work. Interestingly, most of the music was commissioned from western composers, and similarly Asano’s choreographic language is predominantly western contemporary. Initially I yearned for a more ‘Japanese’ dance-style, more earthed than the float and extension of the modern style, however the combination of western influences in both the music and the dance serve to illustrate the cultural duality that these artists have chosen in their move to Australia.

In Repose represents a very personal journey for the all the artists involved. It treads softly around the more contentious issues of colonisation, racial conflict and the White Australia Policy, instead highlighting the power of personal connection through the significant cultural and generational exchanges that took place within a range of communities. Through the retelling of these events it also opens up a space for the audience, rare in contemporary western culture, for our own reflection on death, spirituality, ancestry and a sense of homeland.

In Repose, photographer, storyteller Mayu Kanamori, koto player, sound Satsuki Odamura, dancer, choreographer Wakako Asano, sound design, storyteller Vic McEwan, lighting design Amber Silk, video Shigeaki Iwai, compositions Satsuki Odamura, Mark Isaacs, Rosalind Page, Michael Whiticker; Japan Foundation, Sydney, exhibition April 1-May14, performance April 10, May 1, May 13; http://www.mayu.com.au/folio/inrepose/; www.jpf.org.au

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. web

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

theatre director Subramaniam Velayutham, Minister for the Arts Virginia Judge MP, actor/singer Tama Matheson

at the Small to Medium Performing Arts Forum

courtesy of StreetCorner.com.au

theatre director Subramaniam Velayutham, Minister for the Arts Virginia Judge MP, actor/singer Tama Matheson

at the Small to Medium Performing Arts Forum

IIT WAS QUITE A SURPRISE TO RECEIVE IN THE MAIL AN INVITATION FROM ARTS MINISTER VIRGINIA JUDGE TO PARTICIPATE IN A FORUM AT PARLIAMENT HOUSE ON THE TOPIC OF NSW’S LONG-SUFFERING SMALL TO MEDIUM PERFORMING ARTS SECTOR. IT WAS ODD HOWEVER THAT THE INVITATION WAS NOT FROM ARTS NSW (A DIVISION OF A DEPARTMENT TITLED ‘COMMUNITIES NSW’, SUCH IS THE LATEST NON-ELITIST RELEGATION OF THE ARTS) EVEN THOUGH IT IS INFAMOUSLY ALOOF AND NON-CONSULTATIVE. INSTEAD HERE WAS MINISTER JUDGE DIRECTLY FORGING HER OWN RELATIONSHIP WITH ARTISTS IN A SERIES OF FORUMS FOLLOWED, NO LESS, BY ACTION AND FOLLOW-UP TALKS.

Cynics considered Judge’s move as election-minded, agnostics prayed that there would be more to it than ‘improved networking’ (the funding bodies’ mantra of the decade as was sponsorship to the 1990s) and optimists hoped for small improvements, but doubted that the cold, hard reality of under-funding would even be broached. The palpable Carr legacy to the arts was very much bricks and mortar—CarriageWorks in the city and arts centres across Western Sydney—creating new niches for artists and bringing local government into play. Councils have shown increasing commitment to the arts and, in some cases, have provided artists with funds otherwise not available. However, the overall state of the small to medium sector in NSW remains parlous—whether state or federal, the last thing any politician appears to want to do is raise the standard of living for artists, despite the mountain of evidence of dire need from successive reports by arts economist David Throsby.

not so empty space

Minister Virginia Judge begins with a quote from The Empty Space, Peter Brook’s 1968 treatise on the state of modern theatre, in which the director addresses the importance and potential of the theatrical form. She links those in the room with Brook’s ideals mentioning “presence, immediacy and experiment” and tells us she’s passionate about this sector.

I am among the “leading representatives from the performing arts” invited to discuss challenges for the small to medium creative industries sector: “how to promote and expand the vital role that performance, dance and theatre plays in the community.” The organisers had to rearrange the venue in Parliament House when over 100 representatives from the sector from across the state accepted the minister’s invitation. The gesture is generally welcomed, breaking the long drought in dialogue between artists and the arts bureaucracy in NSW.

The Minister assures us that “investing in the cultural sector is a key part of the Keneally Government’s strategy to stimulate the economy and create vibrant, diverse communities.” She is keen to hear suggestions as to how the government can “support this sector to benefit the industry and the community as a whole.” “The forum will give small to medium performing arts organisations an opportunity to explore new ideas to empower the industry to expand its skills and audience base.” Sounds good.

This is the third in a series of Creative Industries forums. Others brought together practitioners working in the live music industry (with a focus on jazz) and in visual arts and artist-run spaces. Next up will be the film and screen sector (a new Arts NSW program, oddly inherited from Screen NSW) followed, importantly, by an all-in gathering of representatives to discuss the implications of the forums on government arts policy and strategies. Even better.

The Minister is proud that the recent abolition of the restrictive Places of Public Entertainment (PoPE) licenses has created more jobs and opportunities for musicians and performers. No disagreements on this one either.

Mary Darwell, Executive Director, Arts NSW (within Communities NSW) talks about creativity, sustainable business models and access as priorities. She mentions the Arts NSW booth at the recent Australian Performing Arts Market (APAM) in Adelaide, promoting NSW artists. She tells us that structural changes in Arts NSW have been taking place over the last 18 months and that in the last six, the priorities have been Aboriginal arts and culture, opportunities for employment in the Creative Industries and how to reach diverse audiences.

The following statistics are shared. NSW is home to 37 percent of the nation’s creative workforce, accounting for five percent of the State’s workforce or 150,000 jobs for people working in film, music, design, publishing, advertising, architecture, visual arts, television, performing arts, radio and electronic gaming. 39 percent of all creative industry businesses are located in NSW, accounting for 27,000 or four percent of all businesses. The NSW Government’s $42 million Arts Funding Program supports 11 of our major performing arts companies, regional galleries and community-based organisations as well.

By now, we should have been impressed by the scale and largesse of NSW’s commitment to the arts, but as the struggling providers of “presence, immediacy and experiment” it offered little consolation. The empty space for small to medium sector artists is the one felt in the pocket.

where are the artists?

As well as the opportunity to be heard, the gathering was paid respect in the choice of keynote speaker, Sarah Miller, a great supporter and contributor to the sector in her work as former director of Performance Space, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA) and now as Head of the School of Music and Drama in the Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong.

Miller argues that, given the problematic status of artists, their obligation to an increasing number of ‘stakeholders’ and a general lack of clarity about the ‘creative’ society being built for the future, “our governments need to develop clear and reasoned philosophies and strategies outlining just why they provide support for art and artists.” However, on looking at Arts NSW’s strategic plan, Miller “found not one word dedicated to artists of any kind; not one mention. Arts yes, communities yes. Programmes, yes. There’s even a bullet point that promotes advocacy for the arts and promises to improve sustainability for the arts, but nothing about supporting artists—the people who make the ART. Does anyone else find that extraordinary?”

Miller goes on to argue for “locating artists and practitioners at the heart of arts policy development and recognising that the relationships between government and company, funding body and artist is a partnership—not a master/slave or an employer/employee relationship. It means informed, committed, staff supported within the bureaucracies to grow policy development and arts funding programmes in a sustained and bipartisan fashion.” If this could be achieved, it means that “…the development of the sector, the role of the arts and culture in society and so on, will have a completely different complexion, particularly if artists and theatre makers of all kinds are invited to sit at the table when developing policy—which is arguably what the Minister is doing by setting up this forum today.”

Miller says that from this, “a whole lot of other things follow: we can recognise that people need spaces to live and work in; we can identify career pathways, and support artists and companies to develop, mature and flourish. We need artists AND we need infrastructure. It’s a symbiotic relationship—not an either/or one—working through—as Performance Space Director Daniel Brine has identified—both the ‘what “we” need’ (the infrastructure map) and the ‘what “I” need’ (the artist’s map).” But this kind of progress will need artist input—“With an effective advocacy network you can make the case for improved funding.”

Miller acknowledges areas of improvement which Arts NSW should more energetically embrace: “The development of regional, national and international touring circuits have seen small to medium companies flourish in a range of arenas, and Arts NSW should not shy away from supporting such initiatives on the basis of some misplaced parochialism.” She also calls on Sydney Festival to create more opportunities for NSW artists and companies (this should be extended to the Sydney Opera House’s New-York-out-of-town VIVID Festival). In this vein, Miller concludes with extolling the virtues of collaboration and partnerships across the state.

small breakouts

We are then mustered for Breakout Sessions in which groups of 12-15 representatives are consigned to corners of the room with butcher’s paper (always a depressing prospect) to come up with quick responses to a basic agenda.

One hour is allocated to this discussion. A colleague whispers: “How do you convey desperation in an hour?” And, of course, you don’t. Nor do you get even close to the complex needs of a sector that has been denied real recognition and equitable treatment for so long. The groups assembled represent a wide range of creative endeavours and scales of operation. Dancers seemed under-represented. Nevertheless, there was a sense that the gathering was in basic agreement on the answers to the three key questions put to them by the Minister:

1. What have been the successes of the small to medium performing arts sector to date and what can we learn from them?

2. What are your long-term aspirations for the sector?

3. What do you regard as immediate priorities?

successes

The breakout groups proudly declare the sector’s capacity, against the odds, for survival: the ability to remain robust and flexible and, of necessity, multi-skilled. They point out that the sector invests in research and the development of talent in the way large organisations will not, and fuels the festival circuit and new arts centres thus improving infrastructure. Significantly, the bulk of work touring overseas is from this sector. The elimination of the PoPE venue licence restrictions is seen as a particular success.

long-term aspirations

The NSW Government has long been preoccupied with what goes on in the arts within its borders and is rightly proud of its regional arts infrastructure. It has, however, lacked the national and international vision of some other states. Some participants argue for the government to build on the international potential of its artists and companies. Quick turnaround funding is proposed (and has now been implemented; see below) to allow for immediate response to invitations from overseas festivals and other opportunities.

Also suggested is the commissioning of a report on the economic impact of the arts in NSW, incorporating information on working conditions and professional development. These include the need to urgently address the supply of training facilities, especially for dance, circus and physical theatre, and assistance for artists in professional development and with ‘brokerage.’

Infrastructure needs are seen as including how the small to medium performing arts sector connects with others, with a desire for a closer relationship with the education sector to enable more access for artists to young audiences. Similarly the position of the sector in the relationship between Arts NSW and local government is seen as needing clarification, as are connections between various development and touring schemes.

Some of the points raised address fundamentals for the sector. Because its work is often engaged with experiment, long development time is crucial and this needs to be understood when funding decisions are being made. More difficult in an era of accountability, benchmarking and KPIs is the development of a culture of risk aversion and a concomitant fear of failure. What happens then to “presence, immediacy and experiment”?

Even more fundamental is the survival of the artist. It’s argued by forum participants that NSW government and artists should lobby the Federal Government for a recalibration of the unemployment benefit system to acknowledge the value and work of independent artists. This was hoped for in 2009, but Arts Minister Peter Garrett altogether sidestepped the opportunity with further investment in emerging artists funds—welcome in some respects, but always leaving the question begging: emerging into what?

immediate priorities

Urgent need is again expressed for space: affordable, flexible for rehearsal, development and production. Venues like CarriageWorks and those in Western Sydney are significant improvements, as are the Queen Street Studio and like schemes, but still do not meet the real need.

Participants feel that it’s not just the amount of space but its effective use, management and distribution among artists. Suggestions included the establishment of a database, brokerage on behalf of artists, a think-tank about needs and opportunities, and a rethink about how current venues are used.

Sarah Miller’s suggestion is taken up that a peak body for NSW performing arts would give the small to medium sector a united voice and opportunities for conversation and sharing knowledge. Above all, concern for individual artists is strongly expressed, reliant as they are on auspicing companies, organisations, producers and venues to secure funding in NSW.

getting to the point

These responses to the set questions are delivered politely by the team leaders from each group. At one point someone asks me, “Are they speaking your language?”

Finally, there is a refreshing break in the pattern as Grant O’Neill from Legs on the Wall sums up for his group the range of successes—expansion, growth, resilience, partnerships, improved focus, support from local government (regional centres especially)—“very few (of which) have to do with any policy instigated by Arts NSW.”

He goes on to add a list of ‘disasters’, under which category his group identifies a range of misfires by Arts NSW, namely: the recent funding restructure, the way it deals with applications, the nature of its announcements (“not remotely acceptable”), absence of known methodology, barriers to communication (nobody authorised to speak), lack of any understanding—especially of the independent arts sector. O’Neill finishes with a creative flourish, returning to the Minister’s reference to The Empty Space, but as miscommunication.

And finally, Nick Marchand, formerly artistic director of Griffin Theatre Company and now director of the British Council in Australia, eloquently sums up his group’s discussions. Judging by the approving murmurs, he and Grant O’Neill get closest to the feelings in the room. Among the sector’s successes Marchand lists resilience, innovation, collaboration, touring, “ensuring its own longevity outside of Arts NSW,” providing opportunities for artists—emerging, transitional and established—and “creating the bedrock of arts culture.”

Marchand’s group argues the need for government to recognise and acknowledge the individual artist within the system. One size does not fit all. Focusing, like O’Neill, on the absence of dialogue, he tells us that Arts NSW representatives are not approachable: “When you speak to someone on the phone, you need to speak to people who have authority to speak.” Dialogue between state and federal governments is similarly problematic. This group believes Arts NSW should be driving business development and, crucially, opening dialogue between sectors, infrastructure organisations and artists.

are we really talking?

For a first meeting between the small to medium performing arts sector and Arts Minister Judge this was less a conversation than an opportunity for the minister to listen and the sector to have a voice with which to express its mutual, on-going concerns. Critically, Sarah Miller’s keynote address drew attention to the ‘artist’ as the missing agent in Arts NSW policy and to the need to address in a balanced way the relationship between infrastructure and the individual. Much that followed in the responses to the Minister’s set of questions pivots around this issue of the role and place of the artist in our culture, whether individually or in companies.

In a letter (April 30) to forum participants, Minister Judge suggests that “The need for affordable and accessible performance space was the strongest issue that emerged.” As well as reminding us of the reform (PoPE) regulations, Judge writes that the Renew Newcastle model might extend across NSW and that she has asked her department “to examine further options for affordable rehearsal spaces within its current property portfolio as well as exploring other practical options.”

Judge sees networking and advocacy as the second major issue of the forum. She advises the sector to “get together on a more regular basis to share ideas and resources and to represent shared interests to the Government.” She also acknowledges “that there needs to be better communication between the Government and the sector.”

On the position of artists, Judge writes, “I am looking at ways Arts NSW can better engage with artists and arts organisations, in particular improving the Arts Funding Program and support mechanisms for individual artists.”

On May 5, Judge sent out an email announcing “a Quick Response project category which will be offered four times a year to assist individuals and organisations who need to apply outside the annual funding cycle. There will be a six-week turnaround for applications to the Quick Response Category and closing dates are 2 August 2010, 1 November 2010, 7 February 2011 and 2 May 2011. The inclusion of this new funding category is a direct response to issues raised in the three forums that I have hosted for the industry at Parliament House.”

For Project Funding, individual artists in NSW have to find an organisation willing to auspice their grant; it’s not always an easy task to find like-mindedness and it’s quite competitive. The Quick Response application does not appear to require auspicing (although it’s not absolutely clear on the final page who should sign the form). It looks like a breakthrough for artists and a more realistic government attitude to the realities of responding to the marketplace. Mind you, Quick Response funding will presumably be money re-allocated from Annual and Project Funding, which raises the issue again of overall funding levels. As Sarah Miller quipped in her keynote address, “Maybe for the next forum we could invite the Treasurer along as well.”

Just what “improving the Arts Funding Program and support mechanisms for individual artists” will add up to is difficult to imagine in economically challenged NSW and with the limited vision of Arts NSW, but with an election coming we must take Sarah Miller’s prompting seriously. Is it time for small to medium sector artists to act collectively, to stake a claim in the state’s cultural future, the one they themselves are building? Arts Minister Virginia Judge has listened, acted and promises further conversation and action. Let’s define that action with her—the empty space between government and the arts just might begin to fill.

Small to Medium Performing Arts Forum, Parliament House, March 19

First published in RT Online, May 10

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. web

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

save caochangdi art district

In RealTime 92, Dan Edwards wrote from Beijing about Three Shadows Photography Art Centre in Caochangdi, an ambitious initiative to give photography a recognised place in contemporary Chinese art see RT92). We've just received the bad news that Caochangdi, home to many other high profile galleries and leading artist Ai Weiwei's house, has been slated for demolition by local authorities. Protests have been mounted but help is needed. The organisers write, “We are artists, curators, representatives and friends of art institutions who support the Chinese art community and its vibrant environment. In conjunction with the Caochangdi PhotoSpring festival, we are launching an effort to collect 10,000 signatures from art supporters around the world. The goal of this effort is to protect and preserve the current state of the Caochangdi Art District. We want to launch negotiations to explore reasonable ways to resolve this issue. The effort to collect signatures for this petition ends on June 10, 2010. The signatures collected will make up a formal petition to be presented to the Beijing City Government.” You can sign the petition at http://www.threeshadows.cn/qianming/index.htm

reeldance festival: eve sussman

Eve Sussman & The Rufus Corporation's The Rape of the Sabine Women (see RT87) is one of the featured films in this year's Reeldance International Dance on Screen Festival in Sydney. In 2008 Carl Nilsson-Polias saw the 83-minute film and interviewed the maker for RealTime about her interpretation of the historical tale and the influences, classical and modern, on her art. Nilsson-Polias wrote that Sussman and her collaborators “brought the story into the aesthetics of the 1960s and with that came the concomitant cinematic references of that decade. Foremost among these is the work of Michelangelo Antonioni, whose distinctive visual style utilised long focal-length lenses to produce abstract graphical compositions with flat areas of colour, in the tradition of painters such as Barnett Newman. Sussman readily admits to having rewound again and again across “millions” of frames of Antonioni’s films for inspiration, as well as those of Jean-Luc Godard and John Cassavetes.” Also on the 2010 festival program are works by visiting UK filmmaker Shelly Love with her distinctive brand of fantastical imagery (www.shellylove.co.uk). ReelDance International Dance on Screen Festival, Performance Space, CarriageWorks, Sydney, May 13-16, www.reeldance.org.au

Superdeluxe@Artspace

sydney biennale: superdeluxe@artspace

SuperDeluxe@Artspace will present a dynamic program of DJs, sound artists, dancers, music, films and informal PechaKucha Nights over 12 weeks in a program co-curated by SuperDeluxe Tokyo, KDa, Namaiki Joni Waka, Artspace and the Biennale of Sydney. Friday and Saturday nights will feature DJ’s, sound artists, performers, musicians and guest curators including Rosie Dennis, Rice Corpse, Phil Dadson, Scott Donovan, Wade Marynowksy, Oren Ambarchi and Jeff Stein, Gail Priest, Alex White and a swag of Japanese and other artists.