Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

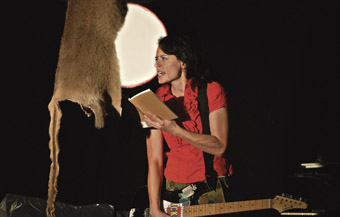

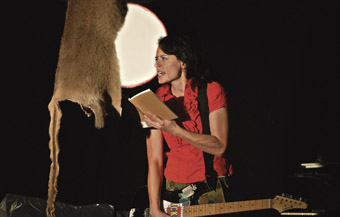

Benedict Andrews

photo Pia Johnson

Benedict Andrews

Benedict Andrews has proven himself to be the most consistently interesting and challenging theatre director in Australia. His totality of vision creates immersive theatrical worlds that seamlessly merge passion, intelligence and a heightened visual sensibility.

Most satisfying is the rigour with which Andrews and his collaborators generate design, media and character motifs which evolve and mutate with a frightening logic (the drinking in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? becomes a flood of ice and spilled liquids underlining emotional abjection; the glass wall between performers and audience in Eldorado fluctuates between windows on the home and a world at war—one nightmarishly unspecified).

Marked physicality—whether realised as utter stillness (Cate Blanchett as Richard II in The War of the Roses) or panicky desperation (everyone in Moving Target)—is characteristic of the director’s work, again with a strong pictorial, even choreographic awareness.

A sense of immediate contemporaneity is also evident, not least in plays chosen from the past. In Andrews’ production of The Season at Sarsaparilla 1960s Australia is meticulously evoked but as if seen through the eyes of Reality TV’s Big Brother, with cameras installed within the set to provide close-ups both amusing and chilling. The director’s account of Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure for Company B takes this surveillance motif even further. The sense of a shared present is also evident in Andrews’ engagement with violence—whether in his realisations of the psychotically closed worlds of Mr Kolpert or Fireface or the unidentified wars offstage in Eldorado or The City or the explicit ones in The War of the Roses.

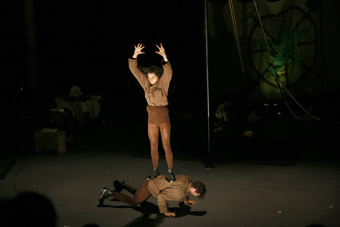

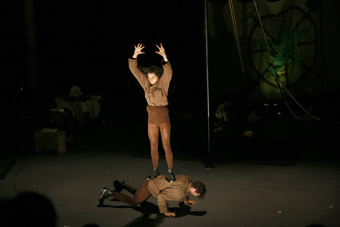

Robin McLeavy, Arky Michael, Measure for Measure, directed by Benedict Andrews

photo Heidrun Löhr

Robin McLeavy, Arky Michael, Measure for Measure, directed by Benedict Andrews

Facilely criticised in some quarters for being party to a ‘director’s theatre’, in “Directors + playwrights: the living & the dead,” Andrews took exception to an attack on young directors by playwright Louis Nowra: “I work with living writers and dead ones. I do not breathe some sigh of relief as Louis Nowra might imagine when working on a classical text as if I were suddenly free to dance on the playwright’s grave. Each project is demanding and all consuming and I enter it with questions and fantasies I want to explore with the community of people I work with and the audience who will watch our work.”

Benedict Andrews was born in Adelaide in 1972, graduated with First Class Honours in Bachelor of Arts from Flinders University Drama Centre, directed locally, including a stint as artistic director of Magpie2 for the State Theatre Company of South Australia. Magpie, formerly a Theatre in Education company, was now boldly targetting the 18-25 year-old demographic but Andrews had barely made his nonetheless palpable mark before Australia Council funding was withdrawn (Murray Bramwell, “A future or a blown youth?,” RT 23, p9, not yet available online).

In 1996 Andrews wrote for RealTime (RT 16, p6, not available online) about the experience of seeing works by Robert Wilson, Pina Bausch, Peter Stein and Robert Lepage, as well as Polish and Japanese performance, at the Edinburgh Festival and Fringe. In 1998 he was awarded the Gloria Payten & Gloria Dawn Fellowship which he used to travel to Europe as well as New York. His New York report for RealTime (“Looking for Elsewhere,” RT 30, p34) included a vivid account of the hard-edged performance style of the work of Richard Maxwell—perhaps an influence. What Andrews’ writing revealed was a young Australian theatre director’s welcome and rare openness to new forms and diverse performance languages.

Andrews went on at various times to work as assistant director to Neil Armfield, Michael Gow and Jim Sharman and was appointed resident director of the Sydney Theatre Company 2000-2003. Since then he has created productions for Malthouse, Sydney Theatre Company and Company B. He directs annually in Australia and at Berlin’s Schaubuhne am Lehniner Platz (see reviews of his Berlin productions of Sarah Kane’s Cleansed and David Harrowers’ Blackbird) and presently lives in Reykjavik, Iceland.

Andrews will direct King Lear at the National Theatre of Iceland in Reykjavik in December this year and the Monteverdi opera The Return of Ulysses for the Young Vic and English National Opera in London in 2011. His production of Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro for Opera Australia is now scheduled for 2012. According to an article in the Sydney Morning Herald, Andrews also has film projects in mind and is to have his poems published in Blast magazine.

In the same interview, Andrews said of Measure for Measure, “I want to stage it like a psycho-sexual thriller, like a David Lynch film…the play is very much concerned with desire and law and strange doubled realities, with another reality seeping through another reality” (June 2, www.smh.com.au/entertainment). Our review of Measure for Measure will appear in the July 12 RealTime online edition and in the RT 98 print edition.

A substantial list of reviews of Andrews’ productions appears below along with an interview and two examples of the director’s writing. One of these is an introduction to the work of Christoph Marthaler, a European opera and theatre director greatly admired by Andrews and written in anticipation of the staging of Marthaler’s Seemannslieder for the 2007 Sydney Festival.

Benedict Andrews has created many memorable works, not all of them perfect but sharing a boldness of vision and a recognisable evolving personality. His productions of Marivaux’s La Dispute (in Timberlake Wertenbaker’s far from funny version of the comedy), Mr Kolpert, Fireface, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and Caryl Churchill’s Far Away seem as vivid in my recollections as when I saw them. But it’s The Wars of the Roses and, above all, The Season at Sarsaparilla that have made the deepest mark, for the scale and fidelity of their vision. The hugely popular production of the Patrick White play and its critical success laid to rest the “directors’ theatre” debate. As James Waites has argued (see full article) it revealed the work to a be a classic of Australian playwrighting and the production worthy of an international audience.

There’s much more that could be said of Benedict Andrews—about the influence of contemporary performance, of media culture, of German theatre (via English engagement with German plays but also directly and in collaboration with German artists) and the evolution of a very particular design sensibility (working with a small, recurrent group of designers), at first glance very European, but as in The Season at Sarsaparilla, totally and radically responsive to our sense of the past as viewed through the present.

Keith Gallasch

artist website

www.benedictandrews.com

reviews

degrees of pathos

keith gallasch: marius von mayenburg’s fireface, 2001

the arts of ageing, the limits of vision

keith gallasch: beatrix christian’s old masters, 2001

tough nights at home

keith gallasch: david gieselmann’s mr kolpert, 2002

benedict andrews: self, style &vision

keith gallasch: calderon’s life is a dream, 2002

beckett-land: spirit and letter, stage and screen

keith gallasch: beckett’s endgame, 2003

once upon the here and now

keith gallasch, caryl churchill’s far away, 2004

sarah kane in berlin

adam jasper smith: sarah kane’s cleansed, 2004

sydney performance: killer logic

keith gallasch: julius caesar, 2005

two ways of looking at blackbird

daniel schlusser, david harrower’s blackbird, 2006

strange words, alarmingly familiar

keith gallasch: marius von mayenburg’s eldorado, 2006

shocking symmetries

keith gallasch: albee’s who’s afraid of virginia woolf?, 2007

another time now

keith gallasch: the season at sarsaparilla, 2007

adelaide festival: the games art plays

keith gallasch & virginia baxter: moving target, 2008

the war within, the war without

keith gallasch: the war of the roses, 2009

violations: sex, history, form

keith gallasch: martin crimp’s the city, 2009

interviews

the luminous nightmare of marius von mayenburg

keith gallasch: benedict andrews on el dorado, 2006

inside looking out

keith gallasch talks with marius von mayenburg, 2008

writings

directors + playwrights: the living & the dead

benedict andrews replies to louis nowra, 2001

christoph marthaler: in the meantime

benedict andrews on a great european director, 2006

related article

wunderkind mysteries

john bailey: melbourne performance, 2010

Sullivan Stapleton and Jackie Weaver, Animal Kingdom

FROM THE OPENING SCENE, ANIMAL KINGDOM GRABS YOU BY THE SCRUFF OF THE NECK AND GIVES YOU A GOOD SHAKE. UNRELENTING, IT PULLS YOU IN TO A MOTHER’S DEN OF A SUBURBAN UNDERWORLD, WHERE YOUNG CRIM BROTHERS FIGHT EACH OTHER AND A BUNCH OF RATBAG COPS TO SURVIVE.

David Michôd (formerly mild-mannered editor at IF Magazine) is a VCA graduate with connections to the Edgerton brothers, having co-written a number of shorts with Joel and Nash before directing his breakthrough Crossbow (2007), which won the Melbourne International Film Festival award for Best Short Film with screenings at Venice, Sundance and Clermont-Ferrant. The development process for Animal Kingdom was a slow boil, taking nearly 10 years to craft the screenplay (based loosely on Melbourne crime stories) and every frame settles into your psyche, with a muted violence and sense of unease; a brilliant psychological drama.

Michôd couldn’t have hoped for a better ensemble to bring his take on corruption and crime in Melbourne’s suburbs in the 80s to life. All performances are note-perfect. With its positioning of men always on the brink, coiled and ready to spring, set around a quietly manipulative mother, the film recalls Rowan Woods’ The Boys. It also acts as an antidote to the hyped up razzamatazz of Underbelly, a show that dumbed down as it left Melbourne becoming less interested in character as it wore on to its second and third series. Animal Kingdom works on another level entirely. Michôd is not so much interested in the stylistic shoot-em-up and tits’n’arse life of the petty crim as in the internal spaces negotiated in a family where criminality has become entrenched, the degree of loyalty within when things become compromised, the lull when every character has begun a moral slide.

Rather than a seedy-glam look at the crimes, we’re thrust into a world in transition where the men themselves sense a shift: Barry (Joel Edgerton), settled with wife and child, wants to escape the game altogether while Craig (Sullivan Stapleton) is too caught up in the paranoia of his speed-haze to be able to read situations readily. And no-one does menace like Ben Mendelsohn. As ‘Pope’, he’s mesmerising, and every time his blue-grey Hawaiian shirt comes into frame (and it’s often what you see before his face), the tension both on screen and off escalates and the audience squirms. His ability to intimidate is not about large outbursts of violence but quiet moments of stalking. Using cat-and-mouse tactics, he tries to goad the truth out of others (accusing Luke Ford’s Darren of being gay because of the type of drink he pours), in a tone that belies his desperation to be the head of the family, the one to turn to as confidante: “Any time you want to talk to someone,” he intones smoothly, as they move past him and head out the door.

Newcomer James Frecheville as 17-year-old Cody, thrown into the family after his mother OD’s, is large and immobile, his face registering not much—an asset, he soon discovers. He looks older than his years but his sensitivity is revealed in the way he treats his girlfriend Nicky (another impressive debut performance from Laura Wheelwright) and longs to be a part of her family.

Reigning over these tall and physically imposing men is the diminutive ‘Smurf’ (Jacki Weaver), her cute nickname covering for a woman who will do anything to protect her brood. There’s a faint whiff of fear in the air as she manipulates her men with cuddles and long, lingering kisses on the mouth, positioning her body in a way that suggests she still sees them as small boys (and their behaviour can be reduced at times to that too). As ‘J’ says in voiceover, his uncles are men who—at the heart of it—are afraid, but too scared to show it. In a nice twist, only the cop, Detective Leckie (Guy Pearce), does not live in a world ruled by fear (although his colleagues, on the take, clearly do).

Animal Kingdom is a brilliant and exciting feature debut for David Michôd. The film’s title cleverly reminds you that, stripped of their clothes, their bravado, their posturing, these men are like lost creatures, products of their environment; it’s do or die. The complexities of character, the evocation of an era, the subtle acting, the deliberate camera, the sense of a community dying out—these all signal a director of great natural skill with an intimate knowledge of filmmaking (and the ability to relay this to his cast and crew) making Animal Kingdom one of the most dynamic films of recent years, and one for repeated viewing.

Animal Kingdom won the Dramatic Jury Prize for World Cinema at the Sundance Film Festival and is currently in national release.

Animal Kingdom, writer, director David Michôd, producers Liz Watts, Bec Smith, director of photography Adam Arkapaw, editor Luke Doolan, production designer Jo Ford, composer Antony Partos, sound designer Sam Petty

This article first appeared online, June 28

RealTime issue #98 Aug-Sept 2010 pg. 29

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

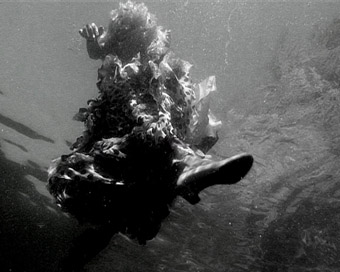

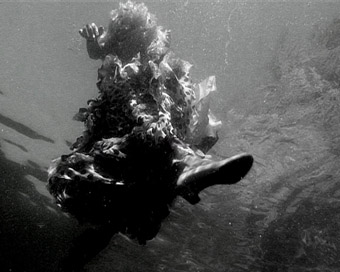

Rachelle Hickson, Reading the Body, Sue Healey & Adam Synott

SUE HEALEY AND ADAM SYNOTT’S READING THE BODY APPEARS ON A SUSPENDED SCREEN IN THE CENTRE OF THE IO MYERS STUDIO, DRAWING THE VISITOR INTO THE DARKENED SPACE. ATTENTION IS HELD BY ITS ELEGANT JUXTAPOSITION OF A MOVING FEMALE PERFORMER (RACHELLE HICKSON) OVERLAID WITH SKELETAL ANIMATIONS THAT ATTACH THEMSELVES TO THE DANCER’S BODY.

New Zealand poet Jenny Borholt’s text provides more layers: “The body as intention. It means well. Is full of good intent. Body as desire.” It’s a fittingly elusive and alluring entrée to the experience of GESTURE, part of ReelDance 2010, a screen-based exhibition running across the UNSW Kensington Campus and, according to the notes, “exploring the performance territory between dance, the everyday and dramatic body.”

Curator Erin Brannigan writes, “Choreography can play with our knowledge of gestural performance, occupying the space between walking and dancing, action and elaboration, communication and expression…These works take the choreographic manipulation of gesture further by spreading the performances across screens, dislocated spaces, manufactured locations and defamiliarised temporalities.”

Anna Mittel, Promise of Fallen Time, Isabel Rocamora

Isabel Rocamora’s video Promise of Fallen Time beckons from a curtained corner of the studio, compelling us to follow the full 19 minutes of its sombre scenario. We are led inside a derelict building, which might be an antechamber to the underworld. A slightly built but powerfully intense performer (Anna Mittel) advances tentatively through this grey world. Her movements are minimal but precise, appearing at times almost involuntary. She encounters a man (Enric Majo) and together they navigate the surfaces of this place (a derelict palace in Barcelona as it turns out), appearing sometimes to be propelled along its walls. Where they’re heading is unclear but the sense of foreboding is palpable, enhanced by the sound of a soft gong and whirring, thrumming chords. A door opens to reveal a young boy with a large dog. The frame freezes. The world turns and we begin again with the two dancers in another place, another time. I head for the light.

Assembly, Kate Murphy

Positioned in a triangle of monitors above head height as well as on a single monitor over the lift, Kate Murphy’s Assembly takes its place in the West Foyer of the Australian School of Business.

Twenty-four children in school uniforms stand in four rows inside a school hall. From time to time their arms move sideways or clutch at their hearts, hands inscribe crosses on their chests. The rhythms of the children’s gestures and their wobbly stillness fit neatly into the fabric, subtly shaking the bland edifice they occupy

I read in the program that these children are moving in response to “reflection exercises” being read from prayer cards that are used daily in the Australian Catholic primary school system: “Close your eyes and imagine that you are being held closely, tenderly in the arms of a most loving person…Whisper in your heart, “I am surrounded by God’s loving protection.” I shiver.

Vivaria, Sam James, installation view

Sam James’ Vivaria presumably takes its title from those places where animals or plants are kept for observation or research. Installed against a “pixellating” wall of black and white mosaic tiles, Vivaria displays the cream of Sydney’s contemporary dance species—Linda Luke, XX, Peter Fraser, Lizzie Thompson and Martin del Amo—each displaced into and onto an array of architectural spaces. The video works within its own grid, a gradually rotating cube with each facet revealing another setting, another performer. Gesturing at internal states, the dancers move as if feeling their way in the dark. Meanwhile buildings transform around them. Their setting renders tentative gestures more dramatic. An arm is caught inside or has it colonised concrete? “A co-joining of impossible spaces and bodies elicits the dancer as a hybrid creature—anthropomorphic like Descarte’s Animal Machines,” writes James. The work is richly textured, at turns elegantly pensive and playful, a meditation on the competing presence of bodies and the built environment.

To experience Vivaria in full requires standing for 26 minutes halfway up the stairs—not something that comes easily to students in the School of Busy-ness who are more likely to accumulate a vision of the work in fragments. I imagine Vivaria functions quite well in this way too. One student asked me why I’m so immersed. “Are you searching for the meaning?” he asks and I imagine one could do worse these days in the School of Business.

Tony Yap, Melangkoli – Sen Siao, Sean O’Brien

Sean O’Brien’s Melangkoli Sen Siao is housed on the 3rd floor of the Robert Webster Building where the two-screen work is installed in the tight reception area of the School of English, Media and Performing Arts. Earphones in place, listening to Madeleine Flynn and Tim Humphrey’s score, I sit inches away from office workers to be transported to the steamy streets of Melaki (Malaysia) and Yogjakarta (Indonesia) where dancers Tony Yap and Agung Gunawan are enacting intensely passionate rituals of grief in response to interior and exterior landscapes, sites that are “key to the performers, to their bodies, to their memories.” In this small, contained space I feel entirely displaced.

GESTURE offers many such disconcerting breaks in the continuum, a series of small shocks that open the mind to the world beyond surfaces. It’s a pertinent provocation and a gift to that increasingly fluid and fast moving entity called the student body.

–

GESTURE: Performance/Film/Dance,ReelDance Installations #04: Reading the Body, choreographer, filmmaker, editor Sue Healey, digital artist Adam Synott, music Darrin Verhagen, animation Adnan Lalani, cinematography Judd Overton, performer Rachelle Hickson, Io Myers Studio; Promise of Fallen Time, director, choreographer Isabel Rocamora, featuring Anna Mittel, Enric Majo, photography Nic Knowland, sound design, Jem Noble, Io Myers Studio; Samuel James, Vivaria, dancers Martin del Amo, Lizzie Thomson, Peter Fraser, XX, Linda Luke, sound Gail Priest, consultant Paul Gazzola; Assembly, Kate Murphy, Australian School of Business; Melangkoli—Sen Siao, writer, filmmaker, editor Sean O’Brien, choreography, dance Agung Gunawan, Tony Yap, music Madeleine Flynn, Tim Humphrey, Robert Webster Building; University of NSW, June 15-19

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Sandra Bullock, Quinton Aaron, The Blind Side

photo courtesy Warner Home Video

Sandra Bullock, Quinton Aaron, The Blind Side

INTRIGUED BY THE PUBLICITY AROUND THE BLIND SIDE, THE AMERICAN FILM, BASED ON A TRUE STORY ABOUT A WEALTHY, SOUTHERN, WHITE, REPUBLICAN FAMILY BECOMING THE LEGAL GUARDIANS OF AN AFRICAN-AMERICAN YOUTH, BIG MIKE, FROM THE VIOLENT, DYSFUNCTIONAL PROJECTS ON THE WRONG SIDE OF MEMPHIS, I DROVE THROUGH FLOOD WATERS TO THE YARRAVILLE SUN CINEMA TO SEE WHAT HAD BEEN DONE WITH THE STORY.

I viewed it in the light of my script for the feature film, Call Me Mum (see RT74) on a similar, Australian subject—the fostering of a Torres Strait Islander by a white woman, in this case myself. The pure, naïve, ‘missionary’ story The Blind Side told was exactly what I did not, could not and would not tell in Call Me Mum. How could it be, written in the context of the Bringing Them Home report and the Stolen Generations narratives?

I found The Blind Side very problematic on a number of levels. The simple narrative and two-dimensional characters meant the meat was removed from the bone in favour of the heart-warming and feel-good; the most interesting story was that told by the actual family photos screened under the end credits. The film would have sunk without trace except for Sandra Bullock’s Oscar-winning performance as Leanne Tuohy which, to me, as a white foster mother, seemed emotionally inspired—her task-oriented attitude, her closet compassion, her moral/ethical toughness, her emotional restraint. She refused, as I know I did, to ‘enjoy’ an emotional smorgasbord at her adoptive son’s expense. What bonded Leanne Tuohy and Big Mike was not pathological maternity playing itself out through interracial adoption, it was that both exhibited a high score in ‘protective instincts.’ Anyway, The Blind Side got me thinking, again, about the way the white adoptive/foster mother is represented in the few Australian films that deal with this subject of interracial adoption/fostering.

Catherine McClements as Kate, Call Me Mum

So, in the light of my construction of the white foster mother in Call Me Mum, I watched those films again—Chauvel’s iconic Jedda, Tracey Moffat’s ‘remake’ of Jedda, Night Cries—A Rural Tragedy, Anne Pratten’s short AFTRS film Terra Nullius, Andrew Bovell’s story for Anna Kokkinos’ Blessed, Baz Luhrmann’s Australia.

Sarah McMann, the white mother in Jedda—pale, scrawny, pathetic, the sickening prototype of the ‘do-gooder, mission manager,’ pathologically depressed after the death of her baby—takes the orphaned Aboriginal child Jedda as a replacement and determinedly tries to ‘tame’ her Aboriginal ways. Sarah teaches Jedda to bathe, read, play the piano, speak ‘well.’ She tries to stop her associating with the Aboriginal station workers and encourages her relationship with the ‘mission Black’ head stockman, Joe, who narrates the film. The Aboriginal child, Jedda, suffers at the hands of failed maternity.

In Night Cries Sarah McMann returns to the screen as a deathly white, geriatric, wheelchair bound invalid (played by Agnes Hardwick) being cared for, in her final days, by a frustrated, voluptuous Jedda (Marcia Langton), in a white, nurse/domestic’s uniform. Dialogue is replaced in the film by a haunting soundscape—amongst the animal cries, ‘corroboree, drum and didgeridoo’ sounds, cracking whips, laughter, the noise of a distant train are the poignant raspings of the dying Sarah and, finally, the extended, heartbreaking weeping of Jedda curled foetally beside the corpse of her dead ‘mother’ on a railway siding platform.

Sandra Bullock, Quinton Aaron, The Blind Side, photo Ralph Nelson, courtesy Warner Home Video; left – Marcia Langton, Agnes Hardick, Night Cries, Tracie Moffat

courtesy Ronin Films

Sandra Bullock, Quinton Aaron, The Blind Side, photo Ralph Nelson, courtesy Warner Home Video; left – Marcia Langton, Agnes Hardick, Night Cries, Tracie Moffat

The mother here is a classic study of the Kristevan abject—ghastly white and wasted, the skin of her scrawny hands and feet old and scaly, emotionally and psychologically absent yet powerfully demanding in her helplessness and finally, a corpse. The film shifts gears from ‘a rural tragedy’ into the horror genre. The abject here is complicated by race and yet Jedda’s grief is real, affective and, in some way, accomplishes a reconciliation.

But that monstrous, old Sarah McMann, she’s one of the unholy undead. She won’t bloody well stay down—because she ain’t dead by a long shot. There she is again, geriatric, demented, pitifully hungry for love—white, white, white skin, hair, nightdress—haunting the well-heeled, leafy, leafy, leafy Melbourne suburbs and the silver screen in Blessed. Abject in her pathologically starved maternity, Laurel Parker denies her adopted Aboriginal son Jimmy access to his birth mother, hiding the humble present she leaves at the door for his 13th birthday; secreting it away behind her volumes of Marx (Karl not Groucho) in her well-stocked bookcase. This time Jedda/Jimmy challenges this ‘mother,’ although it’s still not dialogue; she’s good and dead, and there’s no reconciliation. At the morgue to identify her body he denies her once, twice. “She’s not my mother,” he says to the morgue attendant. “No, this is not my mother.” She has been killed as a direct result of this thwarted craving for maternal love when, in her senile delirium, she embraces and kisses a young thief she mistakes for Jimmy. Thus Bovell proves his racial ‘goodness’ through an unproblematic demonising of the adoptive, white mother—a real soft target.

Alice, in Terra Nullius, does dialogue with her adoptive mother, again reprising the ‘taming’ versus ‘Indigenous instincts’ arguments. The construction of all these Sarah characters is pretty much covered by the discussion between Doug and Sarah McMann in Jedda: “Still trying to turn that wild little magpie into a tame canary, Sarah? Well you won’t do it by shutting her windows at night to keep out the cry of the corroboree, dance and didgeridoo and you won’t wipe out the tribal instincts and desires of a thousand years in one small life.”

Luhrmann’s Australia does, to some extent, progress the discussion in the construction of Lady Sarah Ashley. Nicole Kidman presents us with another Sarah McMann but this is a more contemporary Sarah, finally out of the 50s, and one more in keeping with the adoptive/foster mothers I know. Despite some reservations about her young Aboriginal charge Nullah going walkabout, despite wishing, vaguely, to teach him ‘manners’, despite her inability to have children herself, her adoption and maternity are not constructed as something missionary, pitiful and pathological. It has more in common with Bullock’s Leanne Tuohy in its heightened empathy and task-oriented drive. Nullah is not a blank, needy orphan to be ‘loved’ either. Sarah Ashley responds to Nullah’s agency. He says to her, any number of times, “I will sing you to me.” The two mothers, Nullah’s birth mother and Sarah Ashley, combine forces to protect him from being taken to the mission by the ‘coppers’ at the behest of his violent white father. Finally, Kidman’s Sarah understands and accepts Nullah’s need to go walkabout with his grandfather and she waves goodbye.

How are race and child protection perceived in this country? The voices of adoptive mothers of Indigenous children go unheard. We, with our experience of interracial adoption/fostering, are treated as virtually non-existent except as abusers and thieves. All the parents I know are more like Sarah Ashley and have gone to extraordinary lengths to find and link their Aboriginal or Islander child with their birth families and are acutely aware of the needs of the child to have access to, and knowledge of, their Indigenous heritage and culture. A number have adopted or fostered through Aboriginal agencies yet are still cast as Sarah McManns. (I tried to voice some of this in Call Me Mum.) Most importantly, we know first hand the effect the singular, overarching ‘stolen’ narrative can have on a teenaged child searching for an identity as all young people do. I showed this in Call Me Mum when foster son Warren is cajoled into repeating the ‘stolen’ story by a journalist.

One academic who has researched the subject is Denise Cuthbert. She found that white mothers “have been rendered not only silent but their experiences are virtually unspeakable in the present context” (“Holding the Baby: Questions Arising from Research into the Experiences of Non-Aboriginal Adoptive and Foster Mothers of Aboriginal Children,” Journal of Australian Studies, December, 1998). Proving the point, Damien Rigg, in critiquing Cuthbert’s work, decries “her failure to adequately consider the potential need for some stories to remain unspoken” (“White mothers, Indigenous families, and the politics of voice,” Australian Critical Race and Whiteness Studies Association Journal, e-journal, Vol. 4, No.1, 2008). But the constant theme in Australia, and we hear it particularly from Nullah, is that knowing and telling your ‘story’ is the most important aspect of any culture.

To tell these stories we need to find ways to live in the complexities of the ethical paradox, cultivate a political sophistication, not reinscribe some Australian Good, not fall into the blind spot of assumption as Andrew Bovell does. Our cultural products, such as film, need to speak “against the grain of the good and its incumbent fantasies” (Jennifer Rutherford, The Gauche Intruder: Freud, Lacan and the White Australian Fantasy, 2000). They must acknowledge, explore and articulate the blind spot. Listen to all the stories, not just the socially and politically sanctioned ones.

This article first appeared online June 28

RealTime issue #98 Aug-Sept 2010 pg. 28

© Kathleen Mary Fallon; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Faraday Cage, 2010 Installation view of the Biennale of Sydney 2010, Power House, Cockatoo Island, courtesy the artist and Gallery Koyanagi, Tokyo

photo Sebastian Kriete

Faraday Cage, 2010 Installation view of the Biennale of Sydney 2010, Power House, Cockatoo Island, courtesy the artist and Gallery Koyanagi, Tokyo

HIROSHI SUGIMOTO IS AN ARTIST WHO USES PHOTOGRAPHY TO EXPLORE AND REALISE CONCEPTS ARISING FROM HIS WIDE-RANGING INTERESTS SPANNING ART, SCIENCE, LANDSCAPE, MATHEMATICS, BELIEF SYSTEMS AND ARCHITECTURE

He uses large-format cameras to create portraits of ideas—often to record light events over long time spans—creating revelatory images otherwise unavailable to human perception. For example, the brief but entire life of a candle or the duration of a movie projected on a cinema screen. In sculptural and architectural forms, he uses materials such as plaster or aluminium to explore the potentialities of shadows and abstract geometries.

For the 17th Biennale of Sydney, Sugimoto devised Faraday Cage, a new site-specific work located inside the decommissioned power station at the western end of Sydney Harbour’s Cockatoo Island.

Here and now, in the early 21st century, Cockatoo Island presents a unique palimpsest of maritime industrial activity and technologies, at once embodied and entombed in a utilitarian accumulation of remnant architectures watched over by the emblematic rusting carcasses of eerily figurative monumental cranes. Across, over and through this savagely cut and gouged sandstone mound, untold kilometres of cables, pipes and conduits trace the entire trajectory of the Industrial Revolution. And all of these systems, devices and machines required power to function—provided in stages by the muscles of men and horses, the circulatory energy of steam and fantastic, mysterious, elemental electricity.

After a long wander down a bitumen road between a towering sandstone quarry cliff and a narrow deepwater dock, the approach to Faraday Cage is via a short oversized tunnel carved through the island’s sandstone body. Behind a giant’s ribcage of angular steel trusses, roughly hewn stone walls drip with seeping rainwater. Rounding a bend, a small accidental atrium space serves as outdoor ante-room to the power station proper. Massive monochrome-grey triple-height wooden doors stand closed at the entrance. Faraday Cage is inside.

Common to the industrial vernacular, a much smaller secondary door is cut near ground level into one of the two huge swing-doors. Reminiscent of the experiential commencement of chanoyu, the Japanese tea ceremony, visitors must stoop to enter the building containing the artwork. There’s a brief moment of instinctual care taken as one steps over this awkward threshold, bent toward the floor. On standing upright again, the shadowed, cavernous space of the defunct power station interior is revealed.

High up, a massive gantry crane sits motionless. Hugging one wall on a raised walkway is a procession of tall metal cabinets adorned with rows of white dials and black switches. An open stairwell of rusted steel descends to an ominous dark void. Down there, the relentless sound of a strong flow of water—an underground stream? Huge iron tubes like taut muscular arms, spherical mesh cages, Frankenstein throw-switches, precision rows of bakelite dials, warning signs—everything here is about containment and flow of enormous pressures and deadly forces. This is energy bondage fetishism born of engineering necessity. Over there, worn wooden workbenches with careless assemblages of abstract metal shapes, rusted drums, stained walls, stained puddles…it is a space filled powerfully with absence. And to this redundant post-industrial setting, Sugimoto introduces various interventions, asserting a different potential.

Of immediate visual impact, the artist has contrived a grand, temporary stairway delineated by steel-pipe bannisters to dominate the central void. Ascending dramatically away from the viewer, it is punctuated with a series of four broad metal platforms, each flanked by a pair of large vertical light-boxes displaying exquisite, luminous examples of Sugimoto’s recent experiments in producing photography with (not of) static electricity.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Lightning Fields Illuminated 003 | 2008 black-and-white film with light box

courtesy the artist and Gallery Koyanagi, Tokyo

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Lightning Fields Illuminated 003 | 2008 black-and-white film with light box

These glowing dendritic monochromes serve as symbolic portraits of the friendship between two 19th century ‘natural philosophers.’ Michael Faraday and William Henry Fox Talbot. Faraday’s investigations led to the industrial development of electricity, while Fox Talbot invented calotype photography and used it as a medium for artistic expression. They were both progenitors in the maelstrom of invention that was the Industrial Revolution—within which legacy we now reside.

Atop the stairwell, which commingles industrial make-do with mnemonic tropes from grand theatre foyers, banal hotel lobbies and aristocratic homes, stands a crude wooden column. Astride this column, above the heads of visitors, is an extraordinary menacing figure—an emanation of elemental power, of lightning’s hair-raising cohort, Raijin the Japanese deity of Thunder. Leaping across time and space from 13th century Japan, this arresting polychrome wooden incarnation expresses the energy of thunder as a bulging, squat, blood-red daemon, fierce mouth agape, green-glass eyes madly staring, oversized golden loin-wrap swirling as he runs across the sky beating great invisible drums with double-headed mallets clenched in brutish fists.

This astounding sculpture—so beautifully conceived and skilfully executed—represents a deity with obscure origins in both Indian Hinduism and Chinese Taoism, adapted into Japanese animist traditions and finally into Buddhism as one of the many protectors of Kannon (Avalokitesvara), the 1,000-Armed Bodhisattva of Infinite Compassion. Long before, Raijin attempted to frighten and menace the Buddha, but after becoming a protector of the dharma, he is said to have saved the islands of Japan from invasion by Mongolian forces in 1274. He stood atop the clouds hurling spears of lightning down upon their fleet.

But 13th century Raijin is not the only deity invoked within the charged atmosphere of Faraday Cage. Sugimoto effortlessly reaches back and forth across time, bringing diverse ‘cultural warriors’ together on the stage of his contemporary art practice. If Faraday and Fox Talbot are tangentially evoked, another ‘giant’ of a different order is made unmistakably apparent.

Near the entrance is a well-known photographic portrait of Marcel Duchamp, elucidating an explicit and appropriately tongue-in-cheek reference to the readymade quality of this amazing building/space. The glass in the frame has been damaged by what appear to be a few light hammer blows, and it’s attached to an old two-wheeled hand-pushed goods trolley. Duchamp—and the weight of his conceptual baggage—has been literally wheeled out and parked in the space.

Nearby and behind, camouflaged within the tangle of decommissioned industrial debris, is a Faraday Cage apparatus, named after Michael Faraday’s invention of 1836. This esoteric example of the device incorporates a common metal bird cage, symbolically referencing the capture and taming of elemental forces for human amusement. The Faraday Cage hides there, apparently dormant but silently accumulating immense and invisible power, until periodically discharging its pent-up electrical energy with startling, noisy arcs of blue-white miniature lightning.

The overall effect is of a strange, dimly lit cathedral-like space. It is at once a homage to and mutation from its original purpose, becoming a place for the generation of speculation on art, science and technology, and for the temporary worship of harnessed elemental forces. Perhaps it includes one which is everywhere apparent in this part-industry, part-art hybrid tableau—the elemental force of the human imagination. The imagination to portray epic deities to explain the terrifying indifferent fury of natural forces. The imagination to radically investigate those same forces and derive different explanations in substitution of deities. The imagination to devise technologies to cage and tame and apply those forces. And the imagination to conjure and realise utterly different forms of art—a urinal as sculpture, electricity as a photograph, decayed post-industrial hulk as contemporary art space.

Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Faraday Cage points directly to this cascade of minds falling through time, sparkling with erratic energies.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Faraday Cage 17th Biennale of Sydney, Cockatoo Island, May 12-Aug 1

This article first appeared online, June 28, 2010

RealTime issue #98 Aug-Sept 2010 pg. 34

© Gary Warner; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

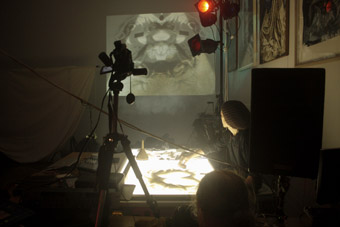

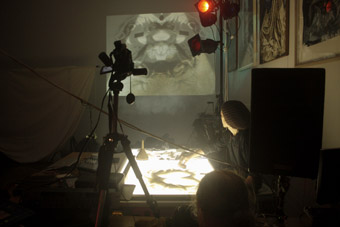

Deborah Robertson, Prompter Live Studio Development, 2010, Hydra Poesis

photo Traianos Pakioufakis

Deborah Robertson, Prompter Live Studio Development, 2010, Hydra Poesis

THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN THEATRE DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVE (WATDI) IS NOW IN THE SECOND YEAR OF ITS PILOT PROGRAM, WITH 2010 APPLICATIONS CURRENTLY AT THE SHORTLIST STAGE AND THREE SUCCESSFUL APPLICANTS FROM 2009 WELL ADVANCED IN THEIR CREATIVE DEVELOPMENTS.

Funded by the Australia Council, WATDI’s formal structure is of particular interest for two reasons: its five-stage, consultative application process, and a seemingly unique management partnership of three key players in Perth’s contemporary performing arts scene: Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA), The Blue Room and ArtRage.

According to PICA Director Amy Barrett-Lennard, WATDI is currently the only significant provider of development funding for new theatre in WA, following the demise of the state government’s Major Production Fund. The scheme’s particular aim has been the encouragement of artists to engage in intensive research and creative development, without necessarily focusing on performance outcomes. It offers amounts of $30,000, $60,000 or $90,000 to assist successful applicants to achieve their goals.

To this end, in 2009-10 local companies Hydra Poesis, pvi collective, and a Sudanese-Australian theatre exploration, The Shrouds or the Dead, have each been fortunate to explore, research and develop work, not only free from the pressure of producing a show, but actively encouraged to ‘think big’ along the way.

Hydra Poesis received $60,000 to develop Prompter Live Studio. The work takes place in three locations simultaneously, with three completely separate audiences linked by interconnected studio installations. It follows the evolving relationship between a foreign correspondent and their local ‘fixer;’ explores a surreal prisoner-exchange; and enters the performative world of the lone video blogger.

Prompter Live Studio’s development team includes Hydra Poesis Director Sam Fox, co-writer Patrick Pittmann and sound artist David Miller, with performers Deborah Robertson, Michelle Robin Anderson and Brendan Ewing. The WATDI grant, in addition to buying development time, has enabled the team to work with mentor Dicky Eton of UK performance group Pacitti Company, live forum TV producer Richard Fabb and writer/dramaturg Stephen Sewell.

Working with these artists, says Fox, has helped the team develop a deep understanding of how Prompter Live Studio’s blend of performance material and technical approach might work with more traditional ideas of storytelling. The project, he says, has been an opportunity that other forms of funding could not have adequately supported.

“One of the things the WATDI process is trying to be true to,” he says, “is the idea of this being a predominantly research and development process, and not turning it into a creative development where we try and produce as much of the work as we can.”

He believes that without the WATDI funding, Hydra Poesis could not have undertaken the research: “We would have made an attempt at the work but…it’s a really ambitious project, and thematically and conceptually it requires a lot of development.” He also feels that the standard “bums on seats” requirement would have precluded it from other current funding options.

WATDI’s five-stage application process begins with a one-page proposal. Shortlisted applicants are interviewed by panellists from the three partner organisations, and a further shortlist is invited to develop proposals further, and provided with $3000 to do so. In-depth discussion then takes place with the panel, this time including an additional, ‘external’ member. Stage five is the funding announcement and from here on, the degree of communication is largely up to the grant recipients.

All the partner organisations see this process as a chance for artists to discuss and develop their proposals in a supportive environment. Fox agrees that rigorous discussion of the proposal at interviews helped Hydra Poesis to refine and develop their proposal. Both Fox and PICA’s Performance Program Manager, Vernon Guest, acknowledge the care with which the artist–funder relationship needs to be managed, however, particularly in a small arts environment where ‘everyone knows everyone.’

Guest says the structure continues to evolve in the current round, with the panel working to achieve the ideal balance between ‘arm’s length’ and ‘responsive’ approaches. The benefit of more communication with artists lies in greater sharing of expertise and advice, and a more supported structure. At the same time, a major benefit of less contact is the minimisation of administration costs. Guest cites some organisations as carrying around 15% of administration costs, partly due to the need for project officers to be constantly communicating with artists. WATDI is currently running at around five to seven percent administration costs.

Both PICA’s Amy Barrett-Lennard and The Blue Room’s Louise Coles comment that one of WATDI’s unexpected positives has been the developing relationship between the three partner organisations. The work of running WATDI is divided according to resources, for example PICA takes care of marketing and communications, as it is well set up to do this.This ‘piggy-backing’ of WATDI requirements onto existing infrastructure is also significant in keeping costs down.

Workshop, The Shrouds or the Dead

Hydra Poesis is nearing the end of its WATDI development, and plans to produce a ‘test’ version of Prompter Live Studio in 2011. Other recipients in 2009, pvi collective, used their WATDI funding to research and develop Transumer, an ‘augmented reality’ work using iPhones, currently running as part of 17th Biennale of Sydney. The Shrouds or the Dead, based on a play by Sudanese-Australian writer Afeif Ismail, took the form of a three-week intensive development in which performers, musicians and a translator joined Ismail in exploring the ‘transcreation’ of his work to an Australian, multicultural context, examining how Sudanese performance tradition could inform and be informed by other methods, including Butoh.

Workshop, The Shrouds or the Dead

ArtRage Festival Director, Marcus Canning, speaks positively about the applications in the current WATDI round: although they were fewer in number, he says, the quality this year was higher overall, with greater diversity and some very strong regional proposals. The point of the initiative, he reasserts, is “development unshackled from the needs of set production outcomes.”

“There is a sense in the second year that there is a growing understanding of what this can mean,” Canning says, “and more key practitioners putting forward a greater array of expansive and brave development ideas.”

It appears WATDI’s impact is threefold: strengthening the research focus of the companies involved through the critical feedback process (a process, it should be noted, that extends not only to successful applicants); providing WA’s theatre sector with an important new opportunity to develop work at a deep level; and building relationships between the organising partners. The Australia Council for the Arts will soon receive reports from WATDI on its first year of operation; then it will begin to make its own assessment of the initiative. Meanwhile, it will be interesting to see what emerges from the 2010 application round.

The Western Australian Theatre Development Initiative (WATDI) is funded by the Australia Council for the Arts and driven by partners PICA, The Blue Room and ArtRage. WADTI: www.watdi.org.au; Hydra Poesis: hydrapoesis.net; pvi collective: www.pvi.com; The Shrouds or the Dead: http://shroudsorthedead.wordpress.com/about/

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. 30

© Urszula Dawkins; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Sarah Ogden, Dylan Young, Moth, Malthouse Theatre and Arena Theatre Company

photo Jeff Busby

Sarah Ogden, Dylan Young, Moth, Malthouse Theatre and Arena Theatre Company

AT THE TIME OF WRITING, THREE PUBLIC DEBATES ARE RICOCHETING AROUND MELBOURNE: THE ALLEGED INVASION OF PRIVACY ENACTED BY SOCIAL MEDIA SITE FACEBOOK; THE “DON’T ASK, DON’T TELL” COMMENTS BY AN AFL FOOTBALLER REGARDING HOMOSEXUALITY IN THE SPORT; AND THE TROUBLING NATIONAL CALL TO “BAN THE BURQA.”

Though no one has, as yet, articulated any link between these issues, it strikes me that a common thread connects them: the right to choose how much of ourselves we reveal to others, and the ways in which we do so. Is society eroding distinctions between public and private, with ‘transparency’ (that loathsome term so favoured by government and big business alike) used to justify an increasingly Foucaultian surveillance of citizens? Maybe. Thankfully I can take these thoughts to the theatre, where the politics of the gaze and the power of the audient can be explored under more controlled conditions.

malthouse & arena: moth

At the centre of Moth, the latest production between Arena Theatre and Malthouse Theatre, is a moment of violence that speaks directly to these concerns. There is an assault, but the true savagery stems less from the physical harm inflicted than the fact that it is filmed on a mobile phone and uploaded to the internet. We watch the two teenage victims reliving their pain as unwilling spectators themselves, party to the comments of schoolmates splaying out beneath the endlessly repeatable footage. It’s a peculiarly postmodern horror that is compounded by their own complicity—in assuming the position of witness to their own bullying, they soon take on the role of bully themselves and turn upon each other.

There’s far more to Moth than this—it’s an outstanding character study inspired by tragic real events, as well as a finely crafted example of collaborative theatremaking at its best. Declan Greene’s script digs deeply into the monstrous dynamics of high school life that many of us have probably repressed (for good reason); it’s almost assured that any audience member will leave with an enriched, if unsettling, understanding of the frightening world today’s teenagers inhabit. It’s also a superbly performed work, with Dylan Young especially creating a compelling and complex anti-hero.

Roberta Bosetti, The Persistence of Dreams: The Sandman, IRAA Theatre

photo Umberto Costamagna

Roberta Bosetti, The Persistence of Dreams: The Sandman, IRAA Theatre

iraa: the persistence of dreams:

the sandman

The gaze is turned upon the audience in IRAA Theatre’s The Persistence of Dreams: The Sandman. A pair of strangers enter your home; after guiding them through the dwelling you are seated and a performance, of a sort, begins. Into the dialogue creep telling references to a range of intertexts that explore the breakdown of social norms and domestic security—Michael Haneke’s Funny Games, David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Soon enough you find yourself involved in just such a violation, subjected to a mild but provocative series of acts that put you in the role of object rather than voyeur. The fact that the experience is shared—you must gather between six and 12 fellow travellers—adds to this a sense of shared subjugation.

The work’s title alludes to the ETA Hoffmann short story which prompted Freud’s theories of the uncanny, and the experience itself literalises this notion as an incursion of the unfamiliar into the known. It’s not a terrifying experience, and neither is The Persistence of Dreams, but it does have a haunting effect enhanced by the manipulation of your home’s lighting and the rearrangement of the items in your living space. Most tellingly, once the strangers had departed, I found myself discussing for several hours with my fellow guests exactly what had just occurred, as if to dispel some lingering phantom and seek through words the return of the familiar.

jo lloyd’s 24 hrs, dancehouse

A recent Jo Lloyd project commissioned by Dancehouse offered a less threatening form of meditation on the way the makers of art modulate what is shown and kept hidden. 24 Hrs saw four choreographers each given a 24-hour period in which to develop a work from scratch, presenting the new performance at the conclusion of the allotted time. Much of the development was recorded on video and streamed online, where audiences could join in discussions of what they were seeing and become active commentators.

Though I could only make it to the first two presentations of 24 Hrs I found in them a marked contrast. Natalie Cursio’s work was a messy installation of recycled waste in which a series of fertile scenarios sprouted. The three dancers worked around clear moments in which power dynamics shifted or relationships reformed themselves; within this framework there was still a loose sense of play and spontaneity which tapped the tight time restrictions to produce a charming liveliness. In a post-show forum Cursio was asked whether the piece would go on to have a further life in some form, but all present seemed to agree that its transience was key to its meaning.

Shelley Lasica’s work the following week—also for three dancers—had a similar air of improvisation within boundaries, but for me didn’t raise the range of questions Cursio’s work inspired. It appeared more a formal exercise in technique, admirable in that respect, but not making the conditions in which it was produced a part of its own investigation. It was a work that could easily be seen as the starting point for a later, more developed project, but this meant that on its own it seemed too much a performance in embryonic form rather than something complete and contained in its own right.

Both pieces did allow audiences to contemplate the exposed mechanics of creation, but does viewing fragments of a work in progress and hearing the thoughts of makers on the fly add to or subtract from our experience of the final result? I don’t know the answer. It simply offers a different experience with its own rewards and disappointments. I certainly wouldn’t want the bones of every production revealed, since one of the joys of art is the possibility of encountering something magnificently realised from a position of innocent ignorance. Conversely, most forms of aesthetic production emerge from a process in which artists select those things they wish to reveal and attempt to control other functional elements. Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain.

Tony Yap, Rasa Sayang

photo Jave Lee

Tony Yap, Rasa Sayang

tony yap, rasa sayang

None of this is new. The contract between a performer and their audience has always possessed its variable clauses of revelation and reticence, knowing and guessing, curiosity and blindness. There is an uncomplicated pleasure in being offered something that doesn’t claim a raw, unmediated transparency but is the result of careful crafting and modulated reticence. One such offering was Tony Yap’s Rasa Sayang, a small but exquisite solo dance accompanied by a live score by Tim Humphrey and Madeleine Flynn.

Before the performance began, Yap was among his audience, conversing with animation, but once the lights dimmed he entered a state of precisely controlled expression that channelled great emotions into tiny gestures. Much of the work seemed to work through memories of Yap’s mother and the intimacy of memory, regret and grief, but this was not an autobiographical work. That only brief, at times abstract details, of this relationship were unveiled didn’t obscure the effects of the piece but broadened them, allowing Yap’s audience space within which to introduce their own experiences and understanding of family and distance. Though not an overt subject of the work, this necessary reciprocity in any act of performance will always inform its shape and significance; when we look at another, we may also be looking at ourselves.

Arena Theatre & Malthouse Theatre, Moth, writer Declan Greene, director Chris Kohn, performers Sarah Ogden, Dylan Young, design Jonathan Oxlade, lighting Rachel Burke, composer Jethro Woodward; Tower Theatre, CUB Malthouse, May 13-30; IRAA Theatre, The Persistence of Dreams: The Sandman, created & performed by Roberta Bosetti & Renato Cuocolo; various locations, April 7-May 7; 24 Hrs, curator Jo Lloyd, choreographers Natalie Cursio, Shelley Lasica, Phillip Adams, Luke George; Dancehouse, April 30 – May 21; Tony Yap Company, Rasa Sayang, creator, performer Tony Yap, composers Tim Humphrey, Madeleine Flynn; fortyfivedownstairs, Melbourne, April 22-25

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. 29

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jason Klarwein, Thom Pain (based on nothing), Queensland Theatre Company

photo Rob Maccoll

Jason Klarwein, Thom Pain (based on nothing), Queensland Theatre Company

SO FAR THIS YEAR IN BRISBANE TWO PERFORMANCES STAND OUT FOR THEIR ABILITY TO TRACK THE TWISTS AND TURNS CONTEMPORARY ANOMIE HAS TAKEN WHILE AT THE SAME TIME SHOCKING US INTO A PROFOUND REALISATION OF OUR OWN ISOLATION AS INDIVIDUALS. INSTEAD OF ASKING US TO GET INVOLVED, JOIN A RECOVERY GROUP OR ASK OUR DOCTOR FOR A PRESCRIPTION FOR PROZAC, THESE WORKS SEVERELY TESTED THE METTLE OF THEIR AUDIENCES AS THEY PRESENTED INVIGORATINGLY DIFFERENT (AND DESPAIRINGLY SIMILAR) VERSIONS OF THE GROUND ZERO OF THE HUMAN CONDITION.

The first of these was the homegrown product, Brian Lucas’ Performance Anxiety (RT96), a whirling dervish of performance cabaret which stands authoritatively alongside, and bears comparison with, American playwright Will Eno’s monologue titled Thom Pain (based on nothing), directed by John Halpin and performed by Jason Klarwein for the Queensland Theatre Company, and which has been described as “stand up existentialism.”

If both productions are dominated by the en-soi—in Sartrean existential terms the world experienced as alien and senselessly contingent dominated—they also cast a penumbral light on the dialectically opposing notion of the pour-soi, the individual self who challenges the givens of both social and personal history from a position deemed to be inalienably and ineluctably free. Both performances hinged on this quixotic quest for self-identity, so it is no wonder that a forthcoming project of Eno’s is an adaptation of the classical treatment of the subject, Ibsen’s Peer Gynt.Nor is it surprising that Lucas is currently directing Ionesco’s absurdist drama, The Chairs, for La Boite Theatre in Brisbane. In an evident revival of tradition, both seem to have learned from Beckett’s use of even the most miniscule silence to offset their words, and are well versed in Pinter’s throwaway sleight of hand.

Eno is a funny writer in the sense that Pinter wrote to The Sunday Times in 1960: “As far as I’m concerned The Caretaker is funny up to a point. Beyond that point it ceases to be funny, and it was because of that point that I wrote it.” Eno in an interview with QTC, revealing the level of his own subtle sleight of hand, writes, “The play’s title reminds me, of course, of Thomas Paine (famous for his Revolutionary War pamphlets with the words “the summer soldier and the sunshine patriot”), but it also somehow reminds me of a broken arm, both soft and hurtful, recognisable, but somehow wrong.” Behind the wounded and apparently character-armoured and conformist representation of Eno’s anti-hero, who wears a plain dark suit and tie and sports black horn-rimmed glasses, stands an authentic revolutionary hero, the existential pour-soi. If Thomas Paine the pamphleteer is feebly recapitulated in Thom Pain’s solipsistic maunderings, and Thom’s feints to rhetorically engage with the audience are succeeded by an almost instantaneous withdrawal from the fray, there is indeed a soft hurtfulness, a recognisable wrongness which is manifestly our own mirrored in his actions.

Jason Klarwein, Thom Pain (based on nothing), Queensland Theatre Company

Although he adopts the stance of being perpetually, paranoidly en garde, it seems useless to attempt to psychoanalise a character who is such a writerly, theatrical confection. Only towards the end, when the defensive precision of language breaks down into a painful, repetitively fragmented stream of consciousness does he let his guard down and invite our sympathy in the usual sense. This is the point at which he flies away, disappears back into the realm of his author’s imagination while leaving behind the concrete presence of the hapless other, his mirrored substitute—the member of the audience he has cajoled onstage to assist in an act of magic which has failed to ensue, unless by Catholic transubstantiation. His last line as he exits is the puckishly ironic: “Isn’t it great to be alive?”

The strength of the production lies in Eno’s Wildean language which incorporates such pithy observations about the end of a love affair as “I disappeared in her and she, wondering where I went, left.” Such ironic lucidity is equally applied to the nicely established loneliness of childhood (Thom doesn’t mention his parents) in an anecdote about the accidental electrocution of his pet dog. The most verbally actualised and traumatic scenario describes the boy’s misapprehension when he is attacked by bees: “Kind of beautiful, if you like that sort of thing. If you like the idea of a little boy desperately spreading stinging bees over his bleeding body. Desperately yelling, ‘Help me, bees, Help,’ and putting his little swollen hand into the hive for more.”

Thom’s recounting of his life turns on such incidents in a Yeatsian gyre rather than any straightforward narrative. A writer like Eno, as Martin Esslin said about Beckett, is essentially lyrical, concerned with such basic questions as “Who am I?” Both Eno and Lucas have returned to the problems enunciated by the great 20th-century poet Rilke in The Notes of Laurid Brigge: “And so we walk around, a mockery and a mere half: neither having achieved being, nor actors.” John Halpin and Jason Klarwein made an intelligent and sensitive team elucidating the philosophical premises, and at the same time urging each of us to become the good person whom Eno was trying to be when he wrote the piece.

Queensland Theatre Company, Thom Pain (based on nothing), writer Will Eno, director Jon Halpin, performer Jason Klarwein, composer Phil Slade, lighting designer Jason Glenwright, design consultant Josh McIntosh; Billie Brown Studio, Brisbane, March 15-April 10

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. 32

© Douglas Leonard; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Rachael Ogle, Sam Fox, Hydra Poesis

Hydra Poesis’ new work Personal Political Physical Challenge premieres in July at PICA. It’s described as “a provocative, exciting and adult interpretation of the childhood game “truth, dare or physical challenge?”

Hydra Poesis is run by Sam Fox who has been artistic director of STEPS Youth Dance Company, created in community cultural development and festival programs and is working on a Masters degree on community collaborative production models at Murdoch University. You can read about his Western Australian Theatre Development Initiative (WATDI) project Prompter Live Studio.

Fox’s motivation for the show is clearly evident, “From B-grade romance to high drama, protagonists are so often concerned with the internal intricacies of their relationships with each other with no regard to their shared connection to the rest of the world. In this show we set those plot indulgences on fire!” Yes, fire is one of the components of the show, along with dance and ‘surreal’ theatrics.

Fox is directing and co-choreographing with collaborators Rachel Ogle and Martin Hansen while the show’s visual world is being realised by Thea Costantino and its music by Stina Thomas. RT

Hydra Poesis, Personal Political Physical Challenge Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, July 16–20; http://hydrapoesis.net

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. 32

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Silvertree & Gellman, Scattered Tacks

photo Alicia Ardern

Silvertree & Gellman, Scattered Tacks

THE NEXT DECADE IN THEATRE AND CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE WILL BE A DECADE OF PHENOMENA, NOT OF SIGNS, OF EXPERIENCING RATHER THAN READING PERFORMANCE. THE FIRST ‘SEMESTER’ OF THE ARTS HOUSE 2010 PROGRAM COULD BE NEATLY DIVIDED IN TWO PARTS: AUSTRALIAN CONTEMPORARY CIRCUS AND UK-BASED RELATIONAL PERFORMANCE. THE LATTER (WHERE THE AUDIENCE BECOME PERFORMERS AND CO-CREATORS) IS A BACKLASH AGAINST 20 YEARS OF MEDIATISED POSTMODERN THEATRE.

These new works are theatre minus stage, performance minus performers and spectacle minus the spectacular. The audience experience is the event itself: tactile, immediate, immersive, anti-ironic. The semiotic component is minimal, sometimes altogether absent, as the performance exists mainly in the mind of the spectator. It appears, perhaps, as our era abandons questions of meaning and engages with amplified possibilities of doing. It’s almost like a direct answer to Deleuze’s dream of the new non-representational theatre, in which “we experience pure forces, dynamic lines in space which act without intermediary upon the spirit.” And although tested by performance-makers both here (bettybooke, Panther) and elsewhere (Rimini Protokoll), the UK, building on its rich variety of live art, is something of a leader.

This form is too young to have encountered much meaningful criticism in Australia, but every form quickly accumulates knowledge. While I don’t think everything we have seen at Arts House could be called successful, the failures are just as interesting, like the results of an experiment.

Take Rotozaza. Their two shows, Etiquette and Wondermart, promised a new form of expression, ‘autoteatro,’ but delivered a half-hearted combination of pomo referentiality and demanding, mediatised interactivity. Both are no more than voices inside a headset, giving instructions to a single audience member. Wondermart is a walk through a(ny) supermarket. Etiquette is 30 minutes in a café, in which you and another audience member perform an encounter, a conversation from Jean Luc Godard’s Vivre Sa Vie, the final scene from Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, and much else—sometimes by talking to each other, sometimes moving figurines on the chess board in front of you.

Wondermart, Rotozaza

photo Ant Hampton

Wondermart, Rotozaza

While very engaging in those few moments when the narration matches what’s happening in space (such as when theories of shopper behaviour are confirmed by innocent bystanders in the supermarket), most of both shows consisted of a series of mundane and tiring little tasks. Despite the interactive pretences, they were not so much an experience for one audience member as a performance by one audience member, with the concomitant stage anxiety—even if nobody was watching. The problem was not just that many aspects of the situation cannot be sufficiently controlled by the audience-performer (my noisy supermarket trolley forbade me from following shoppers as instructed; or the concentration required to both quickly deliver lines and hear your partner-in-dialogue). Rotozaza underestimate our anxiety not to let the performance down: a compulsive need to please the dictatorial voice inside the headphones by performing everything right.

Mem Morrison, Ringside

photo National Museum of Singapore/Chris P

Mem Morrison, Ringside

If Rotozaza forgot how unpleasant structured events can be, Mem Morrison went all the way and staged the worst aspects of a wedding ceremony in Ringside. Its entire conceptual spine is the sense of alienation, monotony, meaninglessness and loneliness one feels at a collective ritual. The performance starts before it starts—audience groups are arranged into family photos, well-dressed and carnation-studded as per instructions—and seated around one long table. An infinite number of black-clad women, both attendants, family and brides-to-be, deliver food and crockery. Amidst the flurry Morrison is the only male, unhappy, confused, 12 years old, jokingly told it’s his turn next, sometimes playing with a Superman toy and sometimes MC-ing with his shoe instead of a microphone.

Ringside’s aspirations are sky-high, but the performance never manages to reveal much of its topical menagerie: ethnicity, gender, tradition, multiculturalism are signposted rather than explored or experienced. Morrison’s entire text is delivered through headphones, creating a mediatised distance that in 2010, after 20 years of screens onstage, is as déjà-vu as it is genuinely disengaging. There is a paradox within Ringside: it purports to bring forth an aspect of Turkish culture, but the distanciation intrinsic to the method condemns it as facile. The experience is ultimately of witnessing a whining 12-year-old, loudly airing his discontent at being dragged to a family event.

Helen Cole’s Collecting Fireworks, on the other hand, a performance archive and an archive-performance, is as simple as it is brilliant. A genuine one-on-one performance (a dark room, a single armchair, recorded voices describing their favourite performance works, followed by recording one’s own contribution), it exemplifies the opening possibilities of this new form: no stage, no performers, but a deeply meaningful experience. I suspect the end result will be a genuinely valuable archive of performance projects, as we are encouraged to remember not only the details of these works, but also the effect they had on us.

The reasons the two local circus performances were on the whole much more successful are complex: Australia’s long tradition of contemporary circus and Melbourne’s close acquaintance with both the form and the artists are not the least important. If with relational performance, imported from an emerging artistic ecology overseas, we occasionally felt both short-changed and ignorant, with circus we could comfortably feel at the world’s cutting edge.

Propaganda, acrobat

photo Ponch Hawkes

Propaganda, acrobat

Acrobat’s long-awaited new work, Propaganda, points to the long tradition of circus used as Soviet agitprop, educational art dreamt up by Lenin in 1919 as “the true art of the people.” The company’s take is both ironic and deeply earnest, and it takes weeks of confusion before concluding that, yes, their open endorsement of cycling, eating veggies and gardening nude was serious. The tongue is in cheek, yes, when spouses Jo Lancaster and Simon Yates heroically kiss in the grand finale, centrally framed to the tune of Advance Australia Fair like the ideal Man and Woman in social-realist art. But it is a very slight joke indeed.

The specificity of circus could be defined as the pendular motion between crude and dangerous reality and the illusion of spectacle: relying on physical strength more than on representational techniques (it is impossible to just ‘act’ a trapeze trick), it can never completely remove the real from the stage. Acrobat’s previous (and better) work—titled smaller, poorer, cheaper—created tension by opening up the spectacle to reveal the hidden extent of the real: social stereotypes and obligations, physical strain, illness. Propaganda foregrounds circus as this family’s life: from the two children pottering around to the unmistakable tenderness between Lancaster and Yates and the heart-on-sleeve honesty of the beliefs they propagate. The dramaturgical incongruence between the ironic self-consciousness of the Soviet theme, with its inevitably negative undercurrent, and the performers’ trademark lack of pretence, remained the least fortunate aspect of the work. From the message to the magnificent skills on display, everything else was flawless.

Scattered Tacks, by Skye and Aelx Gellman and Terri Cat Silvertree (see article), stripped away spectacle to reveal the essence of circus: awe. Circus is a naturally postdramatic form: its narrative arc fragmented, aware of its own performativity (what Muller called “the potentially dying body onstage”) and constantly anxious about the irruption of reality on stage. Scattered Tacks is raw circus, naked: at times it felt like an austere essay in thrill. It revealed that the rhythm of audience suspense and relief hinges less on the grand drama of leaps and tricks and more on visceral awareness of the subtle dangers and pain involved. Eating an onion, climbing barefoot on rough-edged metal cylinders, overworking an already fatigued body—these were the acts that left the audience breathless. Yet they also achieve poignant beauty. The Gellmans and Silvertree bring Australian circus, traditionally rough and bawdy, closer to its conceptual and elegant French sibling, but in a way that is absolutely authentic.

Australia offers a good vantage point from which to observe the human being. Visiting Europe recently, it struck me how dense the semantics of the European theatre are in comparison. Performing bodies there are acculturated and heavy under the many layers of interpretation, history, meaning. The body here, on the other hand, easily overpowers the thin semiotics of Australian culture, emerging strong, bold and without adjectives, without intermediary. Body as phenomenon, not as signifier. It will be interesting to observe how the emerging interest in theatre as presence, rather than representation of meaning, unravels—and how much this country will participate in this trend. In this season it’s circus, one of the oldest forms of performance, that emerges as the more successful. The relational performance works only rarely overcame the trap of referentiality.

Arts House: Rotozaza, Etiquette, Wondermart, co-directors Silvia Mercuriali and Ant Hampton, Arts House and around Melbourne; Mar 16–April 3; Mem Morrison Company, Ringside, writer, director, concept, performance Mem Morrison, sound & music composition Andy Pink, design Stefi Orazi, North Melbourne Town Hall, March 17-21; Helen Cole, Collecting Fireworks, director Helen Cole, technical consultant Alex Bradley, North Melbourne Town Hall, March 17-19; Acrobat, Propaganda, conceived and performed by Simon Yates and Jo Lancaster, also featuring Grover or Fidel Lancaster-Cole, Meat Market, March 27-April 3; Silvertree and Gellman, Scattered Tacks, created and performed by Terri Cat Silvertree, Alex Gellmann, Skye Gellmann, Arts House, Meat Market, Melbourne, March 16-21

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. 33

© Jana Perkovic; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Silvertree & Gellman, Scattered Tacks

photo Alicia Ardern

Silvertree & Gellman, Scattered Tacks

The creators of Scattered Tacks, Skye Gellmann, Terri Cat Silvertree and Aelx Gellmann are fast building a reputation as physical theatre innovators with a performance language all of their own. In this edition Jana Perkovic reviews the recent Art House showing of Scattered Tacks.

The trio variously trained in circus and physical theatre as children working with Cirkidz, Kneehigh Puppeteers and then Urban Myth Theatre of Youth in Adelaide and in later years in corporeal mime and traditional and contemporary Japanese theatre forms.

Aelx Gellman describes himself as “a creative masochist, unusualist and escape artist, specialising in random feats of dexterity and prestidigitation.” To this we might add the human spelling error! The Gellmanns studied at NICA and all were involved in co-founding companies (Rambutan, Shuttlecock) along the way. The three went on to gather a string of Best Emerging and Most Promising awards including for Skye Gellman in 2007 Most Promising Male Actor at Melbourne’s Short and Sweet festival.

In 2008 their signature work, Scattered Tacks won the Melbourne Fringe Award for Most Outstanding Production and in 2009 was programmed by Yaron Lifschitz at CIRCA for their showcase of new works at Brisbane Powerhouse. This is where our reviewer Douglas Leonard was taken by the work: “No extraneous effects. Fragments of a life obscurely shared were dimly recreated. The light distorted, flattened and sculpted identifiable shapes into pure, foreboding forms.” (See full review.) Lifschitz described Scattered Tacks as “one of the most challenging and significant pieces of New Circus to emerge in years.” In the same year, the work toured to Noorderzon Performing Arts Festival in the Netherlands.

Skye Gellmann is currently developing a solo performance for the 2010 Sydney Fringe Festival called Eyes Fight, Projector Light, “a minimalist circus experiment involving an acrobatic body and the cutting light of a slide projector.” It will be is directed by Terri Cat Silvertree who is also developing her own solo performance. RT

www.scatteredtacks.skyebalance.com

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. 34

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Socratis Otto, Leeanna Walsman, Stockholm, Sydney Theatre Company

photo Brett Boardman

Socratis Otto, Leeanna Walsman, Stockholm, Sydney Theatre Company

UK PHYSICAL THEATRE GROUP FRANTIC ASSEMBLY EXPLAIN IN THE PROGRAM NOTES TO THEIR AUSTRALIAN RECONSTRUCTION OF STOCKHOLM, THAT ‘STOCKHOLM SYNDROME’ OCCURS WHEN A “HOSTAGE SHOWS SIGNS OF LOYALTY TO THE HOSTAGE-TAKER.” A TEXT-BASED WORK WITH DANCE AND MOVEMENT INTERJECTIONS, STOCKHOLM HAS BEEN REMOUNTED BY DIRECTOR-CHOREOGRAPHERS SCOTT GRAHAM AND STEVEN HOGGETT WITH AN AUSTRALIAN CAST TO FIT A PRE-EXISTING CHOREOGRAPHIC SCORE. THE PRETEXT FOR THE PLAY IS “DIFFICULT AND DESTRUCTIVE” LOVE.

Playwright Bryony Lavery was commissioned by the company to interweave words with movement around themes of control, desire and manipulation. Employed as a recurring motif, the word “Stockholm” comes to work as an awkwardly literal reference to the demise of a sparring couple’s relationship. It is both the actual ‘elsewhere’ of a holiday in the making and the figural ‘reality’ of a relationship-in-crisis.

The main misuse of the term is in its application to the the young couple, Kali and Todd (Leeanna Walsman and Socratis Otto), Lavery envisaging their world in terms of “retro-jealousies” over past lovers, overblown romantic ideals and sickly sweet histories. On the celebration of Todd’s birthday, they dance around their SMEG/smug kitchen meting out reminiscences and arguments over a recipe for dinner. Stockholm, the literal city, sits in the distance as the promise of holiday escape from a relationship that appears more like something from a real estate advertisement than anything real. Stockholm Syndrome—the metaphorical premise of passive submission to a controlling power—never materialises as we slowly realise that Kali’s manipulations (taunts, violence, spying on Todd’s text messages) are the product of something infinitely more despairing than dynamics of master and slave. It seems that Kali is deeply psychologically unwell—a thematic with which Stockholm unfortunately never risks engaging.