Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Vinyl 7”, Independent Press, IP02

www.iebrisbane.com.au

Sky Needle, Time Hammer

Fortuitously, Sky Needle’s 7″ vinyl disc Time Hammer arrived on my doorstep just after I was given a turntable (having been bereft of one for the last decade). While the group Sky Needle was not known to me (named after the Brisbane architectural folly built for Expo 88 and then purchased by millionaire hairdresser Stefan), two of its three members, Joel Stern and Ross Manning, are Brisbane experimental music stalwarts and they have found a kindred spirit in visual/sound artist Alex Cuffe.

Each plays a curious home made instrument—Stern on “latex pump horn,” Manning on “elastic dust shovel,” and Cuffe on “speaker box.” The result is a joyous, wonky kind of sound, curiously reminiscent of 80s post-punk, crafted into two reasonably tight tracks that are not so much funky as kind of…thunky.

This is a music in which the raw materials of the instruments (including elastic bands, a kitchen dust pan, old speaker housing and lengths of garden hose) are allowed to shine, introducing alternate harmonics and tasty timbres. The plunky twang of Manning’s dust shovel wraps around the chewy rubberiness of Cuffe’s speaker box, punctuated by the nasal honks of Stern’s footpump operated horns (a much more pleasing tonality than a stadium full of vuvuzelas).

Side A offers “Sweet 16 Snorks” which starts with driving buzzy bass notes that play in and around the higher string line, offset by staccato horn hoots and clanging pulses. This weighty intro quickly shifts into a higher, looser and lyrical interplay of strings and horn swoops, only to shift again into a third section of more agitated rhythms, handclaps and jangles. There is a real agility to the structural shifts in this piece, evincing the experience of the artists.

Side B gives us “The Stain” which offers a looser approach with minimalist rhythm figures, occasionally hinting at dissolution, which unevenly accumulate until an abrupt halt. I wish Time Hammer had been a 10-inch single so I could really see where “The Stain” might go.

Almost danceable and strangely cute, Sky Needle’s Time Hammer makes a fine start to my contemporary vinyl collection.

Gail Priest

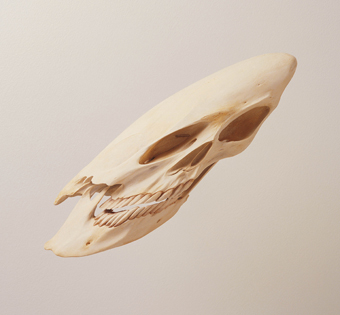

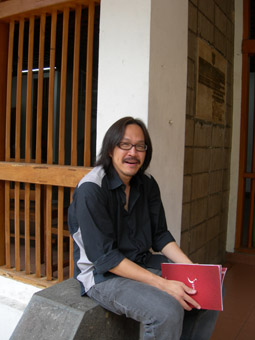

Roger Dean

photo Philippa Horn

Roger Dean

late night sonics

In the first of two collaborations with the vocal ensemble Halcyon, austraLYSIS presents Late Night Sonic Space in Sydney, July 31. Formed in 1970 and working with interactive and network technology since 1995, austraLYSIS has developed a number of innovative methods for controlling rhythmic, timbral and harmonic interaction. The program includes two purely electroacoustic works, one of them by Canadian composer Robert Normandeau; the premiere of Toy Language 1, composed by Roger Dean for mezzo soprano and Halcyon co-founder Jenny Duck-Chong, with live electronics; and a sound and text work called Clay Conversations 2, by Hazel Smith and Joanna Still (UK). There will also be the opportunity to converse with the creators themselves about their work after the concert. The program is presented by the New Music Network with the support of ABC Classic FM and takes place at the ABC Centre, Ultimo. austraLYSIS and halcyon, Late Night Sonic Space, Studio 227, ABC Centre, Ultimo, Sydney, July 31 10.30pm; www.newmusicnetwork.com.au

brodsky quartet, eddie perfect & topology

For some reason the Brodsky Quartet (UK) has surprisingly chosen to escape the northern summer for our winter. The quartet is playing a variety of concerts, though one of the most intriguing is the Songs from the Middle series of performances with Eddie Perfect and musicians from the Australian National Academy of Music (ANAM). Apparently it involves Eddie returning to his roots, and more specifically to the Melbourne suburb of Mentone, where entertainment includes the beach, the bowling club and, more recently, Bunnings. This bout of nostalgia has apparently been brought on by the arrival of a baby girl so perhaps the show will be a new father’s postmodern paean to working families moving forward. You can also see the Brodsky Quartet in concert with contemproary classical ensemble Topology, as part of the Brisbane Powerhouse’s OMG (Other Musical Genres) series. Topology have previously been described by Keith Gallasch as “a live working band with a casually theatrical and jazzy spontaneity.” (You can hear a sample of their work in RealTime’s first sound capsule here.) The Brodsky Quartet, Australian tour, July 22-Aug 8; The Brodsky Quartet, Eddie Perfect, and ANAM musicians, ANAM, Melbourne, July 25-26, Sydney Opera House, Aug 1, Brisbane Powerhouse Aug 6; The Brodsky Quartet and Topology, Brisbane Powerhouse, Aug 8.

sizzling new music at the bowling club

More music news…Ensemble Offspring first conceived of Sizzle as an alternative musical event for Sydney in winter, and better yet as a way of getting contemporary classical music out of the concert hall and into people’s Sunday afternoons. So each Ensemble Offspring member, Bree van Reyk, Veronique Serret and Jason Noble, is curating a musical event at his or her local bowling club (maybe Eddie could come). Noble started proceedings last month in Waverley, and van Reyk continued things this month in Petersham. For the final instalment next month Veronique Serret has invited The Noise improv string quartet, spoken word artist Eleanor Knox, CODA, visual artists and, of course, Ensemble Offspring, to play at the Camperdown Bowling Club. Ensemble Offspring and others, Camperdown Bowling Club, Mallett Street, Camperdown, Sydney, August 1

everyday crisis management

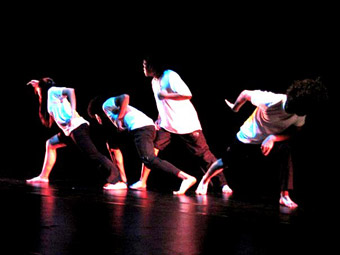

The phrase ‘human interest story’ brings to mind images of personal stories at the end of news broadcasts: babies, animals and, if you’re really lucky, baby animals—in short, everything you’re supposed to avoid in show business. That said, it’s also a catchy title, especially for a show that promises to investigate the relationship between the medium, the message and the mobilisation of empathy. Lucy Guerin’s latest show, commissioned by Malthouse Theatre and the Perth International Arts Festival, “explores our shared consumption of media news” and the “personal impact of the global crises delivered daily to our doorsteps” (press release). Like much of Guerin’s work, surveyed in RealTime’s Archive Highlights here, Human Interest Story combines imagery, gesture and sound to almost surreal effect. Created by an outstanding ensemble of dancers and collaborators and featuring design by Gideon Obarzanek (Mortal Engine), lighting by Paul Jackson and a very special newscast by Anton Enus (SBS), Human Interest Story premieres in Melbourne before touring to Perth. Lucy Guerin Inc, Human Interest Story, Malthouse Theatre, July 23-August 1; www.malthousetheatre.com.au; Perth International Arts Festival Feb 11-March 7 2011

Jenny Kemp, Madeleine

photo courtesy of Malthouse

Jenny Kemp, Madeleine

contemplating madness

One issue that has often made the news over the past year is mental health, first when Professor Pat McGorry was appointed as Australian of the Year and then when Professor John Mendoza resigned from the National Advisory Council on Mental Health in frustration at the government’s efforts or lack thereof. Of course, themes of mental health and illness have a long history in art and theatre. One example is Jenny Kemp’s exploration of loss, longing and mania in her 2008 work Kitten. This month, this adventurous writer-director of dream like performance works mounts the companion piece, Madeleine, at Arts House, Melbourne. Madeleine is turning 19 and starting to show signs of schizophrenia. As she disintegrates mentally so too does her family, and together they are thrust onto the path to tragedy. Madeleine “brings the uncertain world of mental illness into presence, for contemplation. It provides a space within which these concerns can become a reality—a poetic reality of beauty, humour and horror” (press release). Jenny Kemp and Black Sequin Productions, Madeleine, Arts House, North Melbourne August 3-8 https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/ArtsHouse/

computer gaming on in launceston

If you missed Game On, the exhibition devoted to the history of video games curated by the Barbican and hosted in Australia by ACMI in 2008 (RT84, p.29), then you might want to catch Game On 2.0. This new exhibition is having its world premiere at the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery in Launceston. While the new version includes several new pinball machines and arcade games from the past, it also shows off the Virtusphere, which is apparently “the best locomotion interface for virtual entertainment.” Game On 2.0, Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston, July 3-Oct 3, http://www.qvmag.tas.gov.au/gameon/

live-in performance art

Anastasia Klose has been sitting in bed since July 9 and will continue to do so until August 8. If you want to see her, she is at the Australian Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide. But she’s not just sitting, she’s also writing, typing her thoughts onto her laptop. These musings, which shift from the banal to beautiful and back again (“Staring…Checking phone,” “you must never admit to your mistakes, you must instead claim them, as if you intended them,” “The anxiety of a white screen. Here is my new performance. Sit for 5 minutes without typing. Starting now. 3.04”) are then projected onto the white wall behind her that also serves as a bed head. The performance, titled i thought i was wrong but it turns out I was wrong, is accompanied by an essay called In bed with Anastasia: intimate strangers, written by Larissa Hjorth. Anastasia Klose, i thought i was wrong but it turns out I was wrong , Australian Experimental Art Foundation, July 9-Aug 8 http://aeaf.org.au/exhibitions/10_klose.html

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Out of Key(s), Opovoempé

photo courtesy of Opovoempé

Out of Key(s), Opovoempé

IN REALTIME 95 (“PERFORMANCE IN BRAZIL’S MEGA-METROPOLIS,” P42-43), CARLOS GOMES, A BRAZILIAN DIRECTOR BASED IN SYDNEY AND WORKING WITH THEATRE KANTANKA, REPORTED ON A RECENT VISIT TO SÃO PAULO, SURVEYING THE WAYS IN WHICH COMPANIES ARE ENGAGING WITH THEIR CITY, THEATRICALLY, POLITICALLY AND IN TERMS OF URBAN GEOGRAPHY. MELBOURNE ACTOR AND THEATRE MAKER JAMES BRENNAN RECENTLY VISITED THE CITY WHILE ON A KEITH AND ELISABETH MURDOCH TRAVELLING FELLOWSHIP. HE REPORTS HERE ON THE WORK OF THREE COMPANIES WHO CREATE WORKS IN WHICH THEY OCCUPY PUBLIC SPACE.

Whatever the country, theatre gives itself the mandate to claim space and to unravel that space in order to establish a relationship with those whom it seeks to make its public. I recently encountered three theatre companies in São Paulo, Brazil. What follows is an account of how each tackled public space, the audiences they found themselves ensconced with and the boundaries that marked their performances.

Compania Livre’s recent work was an adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, performed over three nights in SESC Pompeia, one of many SESC cultural sites found throughout São Paulo state (Serviço Social de Comércio is a non-government cultural network established in 1946 by the industrial sector). The site has a theatre space, but instead director Cibele Forjaz chose a large empty studio, adjacent to the theatre which has changed little since its past life as a steel drum factory. As one of Brazil’s most successful contemporary theatre directors, Forjaz has always had an appetite for unusual spaces. With her reputation she has access to a wide range of theatre venues in São Paulo, but continues to search out unconventional sites in which to house her visions.

In discussing The Idiot she said, “We wanted a space that held scene and public in connection…moreover, we required that as the spectacle developed, action could occur concurrently in several spaces.” This was achieved through a design which supported a number of overlapping performance areas, able to transform quickly, in keeping with, as Forjaz puts it, “the subjectivity of each character.” The success of Compania Livre’s well-integrated performance environment can also be attributed to the actors themselves. Accompanied by a musician and a small technical crew, they ran, sang, hovered, danced, washed and prayed the space into ever-new formations. When the work required the actors to articulate somewhat stylised moments, this was achieved with a sense of ease, as if an extension of their social selves rather than heightened performance personas. Furthermore when invited, the audience participated comfortably, contributing to an atmosphere of permission. In a characteristically Brazilian moment, audience joined actors as they sang a well-loved bossa nova song during the moving climax. Tears rolled on and off stage and in that moment I was a firm believer in “freedom inspires freedom.”

Kastelo, Teatro da Vertigem

photo Angelo Lorenzetti

Kastelo, Teatro da Vertigem

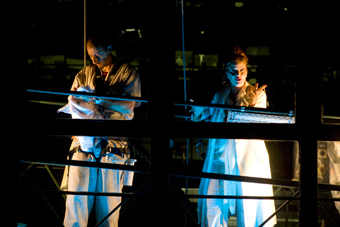

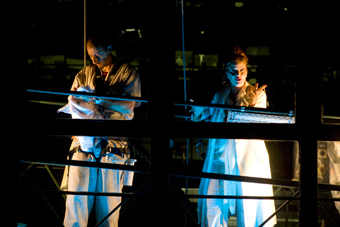

Another company which chose to forego the conventional performance space offered at another SESC site is Teatro da Vertigem (RT95, p42). This time, the design and overall effect served to distance audience and performer. Given that the work was an adaptation of Kafka’s The Castle, Kastelo, this did not seem inappropriate, since the work is marked by an inherent sense of distance. Kastelo was exactly the sort of work I was hoping to see in São Paulo—risky site-specific.

Performed on the outside of the SESC building by actors on moving window-cleaning platforms, the work was viewed by an audience seated on swivel chairs scattered throughout a disused office space on the fourth level of the building. The obvious risks of performing while suspended on cables were further emphasised by the actors, who, with an uncanny absence of apprehension, would jump off their platforms and hang from their harnesses. As the work developed, there was an increasing amount of head banging against the glass, sometimes done by swinging from a distance, which resulted in one of the actors dangling, upside down and bloody for long periods. Eliciting moments of empathy, ultimately Teatro da Vertigem was unable to bridge the gap between audience and actors. Like the protagonist, we also struggled to achieve meaningful contact.

Hand in hand with its commitment to exploring alternative arenas in which to perform, Teatro da Vertigem’s work has a strong social aspect. The company’s director, Antonio Araujo, listed projects which have engaged with locations in cities and rural areas and inside and outside various institutions. Recently the company commenced work on a project in Cracolandia (“Crack Land”), an area avoided by many São Paulo residents due to the high crime rate and drug use. As a consequence the work has the potential to offer new perspectives on an area with a strong negative ambience, inbuilt and palpable. As with many of São Paulo’ contemporary theatre works, the project will involve a significant period of research in Cracolandia itself.

Out of Key(s), Opovoempé

photo Ana Carmen Foschini

Out of Key(s), Opovoempé

Opovoempé is a São Paulo theatre company whose agenda is focused directly on public space. Since its birth in 2005, the company has made a series of public interventions in locations including not just streets, fairs and squares, but also supermarkets, train stations and shop windows. Their works range from the overtly theatrical to the invisible, and draw on the legacy of cultural activism championed by the late Brazilian theatre maker, Augusto Boal. The company’s title (literally “people on their feet”) reflects its aims and “gives the idea of people moving, rather then riding or sitting. People in active existence or operation.”

The company states that their projects “aim to promote new relations between people and the space of the city, and are based in the exploration of the frontiers of the dramatic act.” With this premise they act to infiltrate chosen social settings to “subvert operating systems and alter the perception of participants.” Forty years ago such a statement may have made them a target for the Brazilian dictatorship, however these days their work resonates more as poetic provocation than political motivation and has received the support of the State Secretariat of Culture.

By offering new perspectives of shared space and interactions, Opovoempé illuminates the public lives of São Paulo residents and beyond. In doing so the company calls for vivid interaction with the spectator, to be “stimulated to perceive, see, imagine, interfere, create, act.” Such an active blurring of boundaries between art and life certainly fuels a fibrous artistic discourse and brings to mind the layered impact of Deborah Kelly and Jane McKernan?s powerful evocation of the Tiananmen Square protest, Tank Man Tango (RT93, p2-3).

With ever expanding public liability laws defining acceptable public activity, companies such as these three play an important role in questioning how we inhabit our environments and provide valuable stimulus for new perspectives.

I have always been intuitively committed to heightening the collision between theatre and life. Interacting with these companies in Brazil confirmed my belief in the critical need to deliberately exchange the space between the real world and theatre, in such a way as to confuse expectation. This may not only awaken the sleeper, but can also transform our cities and towns into places of social communion. By magnifying and directing performer ability to manipulate space, time and meaning, each of these companies illustrates the power of the individual to transform space and thought well beyond the walls of the theatre.

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. web

The Fitter’s Workshop

photo Peter Hislop

The Fitter’s Workshop

WALTER BURLEY GRIFFIN, THE ARCHITECT OF CANBERRA, ONCE WROTE THAT “A CITY IS FROZEN MUSIC.” ACCORDINGLY CHRIS LATHAM, THE DIRECTOR OF THE RECENT CANBERRA INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL OF CHAMBER MUSIC, REFLECTED THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MUSIC, ARCHITECTURE AND THE STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF THE HUMAN BODY IN A FESTIVAL EXPLORING DIFFERENT SPACES FOR PERFORMANCE AND DIFFERENT WAYS BODIES RECEIVE AND UNDERSTAND SOUND.

From Domenico de Clario’s all night piano vigil to a full performance of the Monteverdi Vespers, Latham placed concerts in venues ranging from the soaring atrium of the High Court to the angular, postmodernist foyer of the National Museum, to the low, sleek, domestic interior of the Swiss Embassy, a 1970s New Brutalist reverie in concrete and glass.

In this last venue, Swiss oboist Thomas Indermuhle illustrated the contiguity of these ideas on an intimate scale, showing how tonguing, rasping, buzzing, tapping and singing into the bore of the instrument can create a performance alchemy that makes wood sound like metal and the performance “feel quite vocal” to the performer.

Cordiality between performer and audience occurred even in the most vast of spaces, belying the fact that the majority of the 10 days of concerts were of unashamedly ‘high’ ambition and tone. The festival opened with the New Purple Forbidden City Orchestra—”China’s finest ensemble of traditional instruments”—with music “from the great dynasties of Chinese history” and poetry from the I Ching. These ancient ritual traditions unashamedly revere music as go-between of cosmic and material worlds. The nearly 30 concerts which followed honoured these aspirations in a series of prayers, praises and laments, trances, motets and incantations, the composer list—from Josquin, Aquinas, Bingen and Gesualdo to Beethoven, Bach, Mozart, Mahler, Messiaen and Takemitsu—reading like a who’s who of classical and pre-classical ‘greats’.

Of the living composers (for example, Ross Edwards, Sofia Gubaidulina, Rautavaara, Gorecki, Tavener, Sculthorpe), most aspire to a tone of epic reverence, with some (Sculthorpe and Edwards of course) also paying homage to landscape and western and indigenous histories. The sole minimalist on the program, Terry Riley, builds his work based on pitches and rhythms from ancient Indian traditions. His peers treat his work and the man himself as an inspiration and kind of saint.

If I have any lingering doubts about the festival, it would be the way its offerings resisted dark spaces. Even that Australian master of the macabre and the Grand Guignol, Larry Sitsky, was represented in more moderate incarnations, whilst Elena Kats-Chernin, her Motet wedged between several powerful, trance-inducing choral works by Arvo Part, played lightly on the edge of satire.

The festival’s ‘Gold’ theme reflects Latham’s focus on things precious, from water to gemstones to unguents such as frankincense and myrrh. Various rituals were at least referred to, if not performed: journeys towards marriage, to the underworld, to allaying death, or of the Magi. Some epic feats were achieved: from Mahler to Strauss and Wagner to Tavener within two days, under the baton of Roland Peelman, for the most part to very good effect and sometimes stunningly. Perhaps by focusing on ritual and beauty the festival asked its audience to focus its ears in very particular ways.

It was a canny move to program the Australian Baroque Brass to play and repeat its offerings in different spaces so that the audience could pay attention to variations in acoustics. A contemporary audience, already a little distanced from familiarity with the sounds of sackbut (literally “push-pull”—a predecessor to the contemporary trombone) and cornet brought curious ears to the short performances which, like a progressive dinner, moved from one type and size of building to another. We were treated to a kind of attunement, not just to what, but also to how we hear and give shape to interpretation.

Jouissance, Kassia

photo courtesy of CIMF

Jouissance, Kassia

The Melbourne group Jouissance is exemplary in this aspect. The group creates dialogue between ancient chant and contemporary culture. Here their focus was the medieval Kassia, considered the first female composer whose scores are both extant and able to be interpreted by modern scholars and musicians. The group interacts with, rather than replicates, early work. Artistic director Nick Tsiavos says that studying postmodern theory in the 1980s made him think hard about contexts—what era we live in, what our own ears and experiences bring to any interpretation. The result is a performance philosophy that sees historical interpretation transformed by contemporary zeitgeist.

Tsiavos’s double bass sometimes breaks with jazz-influenced riffs; Peter Neville’s playing of contemporary, conical ‘Ausbells’ and simple, hung pieces of sheet metal carry medieval resonance but allow a sassy exploration of contemporary mood. Anne Norman brings her generous, elastically expressive shakuhachi into the fold (this is Byzantium via Japan), whilst Jerzy Kozlowski’s canonical bass resonates to our more secular sorrows. Deborah Kayser’s soprano breaks and dives and flutters in an extraordinary free-form exploration of, and improvisation around, the emotions of the mystic Kassia’s text. At certain moments, I am quite sure Kayser’s body has become a shakuhachi, mimicking its tonalities and technique (tonguing, fluttering, and shaking). This body and voice become the temple of Kassia’s prayers.

Significantly, Jouissance’s primary modality is improvisation, which was not a key element in this festival. Because this group is so practised in the art, it achieved alchemical transformations, which I would not say was always the case in the themed concerts such as “In Praise of Water.” It moved from composed mantras interspersed with improvised reveries, to one of Copland’s aching prairie-calls, to a very moving, but traditional rendition of Waltzing Matilda in a curious sequence that almost came off. By his third improvised interlude, Bill Risby developed some very interesting reflections on the preceding musical themes, yet I sat within an experience that felt thematically controlled, not musically released.

The standout in this very concert, however, by the festival’s resident composer, tells a different story. Ross Edwards’ The Lost Man (words by Judith Wright) is a delicate and demanding piece that sets up layers of listening in slow waves that build and recede and build again throughout. Edwards manages to gesture to the qualities and motions of water without pretending to make it. The piece harvested the piano; I heard it fill like a precious lake. Edwards writes about his compositional process as “an interplay of (materials) assimilated and interfused with sound patterns subconsciously gleaned from the natural world.” This suggests that for all his ideas, research and technique the composer allows something else to take over, relinquishing control.

It was good fortune the festival secured the Fitter’s Workshop, part of the 1920s Powerhouse Precinct in Kingston on the Lake foreshores of South Canberra—an enormous but welcoming, clear and fresh space of bright acoustic which many Canberrans hope to co-opt as a permanent performance venue. It was also exceptionally canny of Chris Latham to weave together the combined forces of amateur, professional and student choirs and orchestras—including the T’ang and New Zealand String Quartets, the Song Company, the Canberra Camerata, the forces of the School of Music, ANU—and other local professionals and composers, to weave a strong sense of support and community. The festival’s resources were bolstered by each concert having a personal sponsor from within the local community.

Much of the success of these concerts was due to the extraordinary abilities of Roland Peelman who could elicit both subtle and impassioned musical nuances from the professional and amateur instrumentalists, soloists and choirs, and somehow blend the voices. The grand finale of the Vespers, written in 1610, called for precise coordination between melismatic vocal lines and ostinato (provided by lute, contrabass and cello] and fine judgment in moving between different, complex groupings of voices, especially when in canon. The great unison “Amen” charged the room, as if the Age of Doubt, which began three centuries after its composition, never really happened.

In some concerts, but not most, one could feel the strain of attempting too much. Yet at their best, the combined forces achieved a translucent dignity—perhaps too the goal stated in Hexagram 16 of the I Ching: “harmony between Man, Earth and Heaven…a dance of Man with the Stars”.

Canberra International Festival of Chamber Music, May 14-23; www.cimf.org.au

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. web

© Zsuzsanna Soboslay; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Caretaker

THE SCREENING OF THE 2009 FILMS COMPRISING THE 11TH SERIES OF THE LESTER BOSTOCK INDIGENOUS MENTORSHIPS (NOW PART OF METRO SCREEN'S FIRST BREAK GRANTS SCHEME AS INDIGENOUS BREAKTHROUGH) WAS LAUNCHED BY THE MAN HIMSELF—A KEY PROGENITOR IN THE FOUNDING AND NURTURING OF AUSTRALIAN INDIGENOUS FILMMAKING IN THE 1980S AND 90S AT AFTRS AND METRO SCREEN. SINCE THE BOSTOCK MENTORSHIP'S INCEPTION IN THE 1990S 44 FILMS HAVE BEEN MADE AS PART OF THE PROGRAM.

Bostock, whose focus these days is on dealing with the challenges of disability in Aboriginal society (through the National Indigenous Disability Network), noted a long-term shift in Indigenous filmmaking from largely issue-based content to increasingly personal stories. However, he argued that “the only really political films” continued to be made by Aboriginals and with a distinctive filmmaking style.

Fault, directed by Martin Adams (mentored by Jason De Santolo), is immediately and cruelly suspenseful. An anxious, depleted man sits in a bleak room with a gun and the clack of a flip clock. 2:59. Cut to a laneway where we see him with a male friend. Cut to room. 3:11. The man looks suicidal. Cut to the man shooting his friend, accidentally, or so we think. There's a sharp knock on the door. We hear a gun shot. Cut to the man walking away with his friend, but time is out of whack—the man is now his younger self. At the moment of death he re-lives his lost friendship, even love perhaps. Fault is raw filmmaking, if spare and deftly edited. Its brevity and the focus on generating tension allow little room for character detail but its gritty mood (amplified by a grinding sound score between silences) and sense of loss is palpable.

Quarantine (director Tyrone Sheather, mentor Simon Portus) reveals a young couple in love, lolling on the grass beneath the looming stars, “together forever.” Their reverie is interrupted by a massive crash. The young man pushes through the bush to find a smouldering comet. As the couple approach it the world of nature evaporates into an enveloping whiteness out of which men in protective outfits with guns and hypodermic needles emerge. The couple flee, but shot and bleeding, they fall. One of the men announces the need to quarantine the area as soon as possible: the couple have been infected by an alien virus and duly eliminated to prevent its spread. Some of the effects are striking, other moments are awkward, the dialogue is stilted and the story lacks the touch of complexity that could have lifted Quarantine out of the morass of the sci-fi paranoia genre.

Stylishly shot in widescreen, Alanna Rose's The Caretaker (mentor Margot Nash) is an accomplished film which immerses the viewer in the world of the ageing Willie “The Kid.” Willie, critically not identified as such until the end of the film when he turns to reveal the lettering on his jacket, sits centre screen in a boxing ring in a darkened space, the spare, sharp light dancing with dust. Looking at old photographs which “come to life,” takes him back to his childhood. He and his brother, poor kids without a father, sneak into a boxing gym where they win the support of a trainer. Years later they crawl under a canvas into the world of tent boxing (a beautifully executed piece of editing in which we, with the boys, are confronted with a massive, gloriously red, beating drum).

Now grown up, the brothers are part of Australia's tent boxing world before it disappeared in 1971. Rain beats down as old Willie peers into his past. So far, we imagine The Caretaker to be in the tradition of the “could have been a contender” or “the down and out” school of boxing films. But the story here is even darker, one brother killing another with a calculated KO out of jealousy and ambition. Apparent nostalgia disturbingly mutates into real guilt. More than this, Willie, no longer a champion, has made himself look at his past.

While a couple of scenes are unnecessarily expository and the emotion is trowelled on at the end (an overlay of thunder and a good song with a strong hook), The Caretaker constitutes promising filmmaking from Rose and a strong cast and seriously expert crew. The film is dedicated to the memory of artist and filmmaker Michael Riley whose documentaries included Tent Boxers (1997). Alanna Rose has been awarded the 2010 Indigenous Breakthrough grant for $22,000 towards a film of up to 20 minutes and a range of support from Metro Screen.

Fault, writer, director Martin Adams, cinematography Fabio Cavadini, sound design, composition Grant Leigh Saunders, editor Peter Cramer, producer Jason De Santolo, actors Ken Canning, Scott Canning, Gio De Santolo, 4:50mins; Quarantine, director, writer Tyrone Sheather, cinematography Jack Anderson, sound Jason Dean, editor Peter Ward, producer Jack Anderson, actors Kay Cast, Dylan Underwood, 4:00mins; The Caretaker, writer, director Alanna Rose, cinematography Brandon Jones, production designer Brett Wilbe, editor Craig Savage & Oana Voicu, producer Jade Rose, actors Mick Mundine, DJ Mundine, Paul Sinclair, Kobi Hookey, Derek Walker, Tony Barry, Tony Ryan, Warwick Moss, 15:35mins; Lester Bostock Indigenous Mentorship screening, Chauvel Cinema, Sydney, April 20; www.metroscreen.org.au

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. web

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Merah

photo Phalla San

Merah

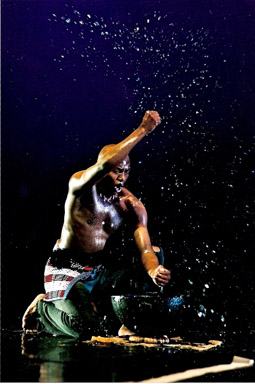

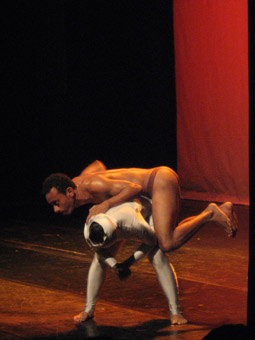

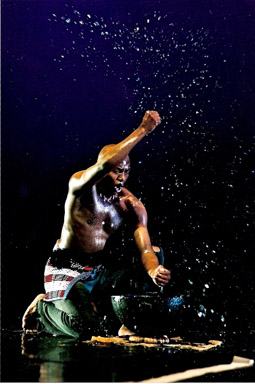

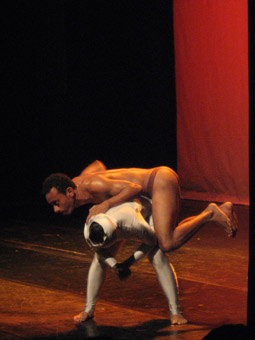

AT THE BEGINNING OF ASRI MERY SIDOWATI’S MERAH (RED), THE STAGE IS IN TOTAL DARKNESS UNTIL SEVERAL DIM LIGHTS ALLOW A GLIMPSE OF TWO FIGURES. WE SEE AN ALMOST NAKED MAN IN A LOIN CLOTH AND WOMAN WEARING A TIGHT DARK OUTFIT WRAPPED AROUND HER BODY FROM TOP TO ALMOST TOE, THE DESIGN MAKING IT IMPOSSIBLE TO SEE HER FACE.

In the background there’s a sound like a cricket, adding to a heightened sense of quiet. It’s as if we are being drawn into a jungle, but serenity brings with it a terrorizing kind of solitude. The stage is dark again. Gradually the sound changes to a kind of a heavy mumbling while scattered rays are slowly projected on the backdrop, like sunlight peeking through forest trees, but again suggesting stillness.

Originally a 2006 graduation piece, Merah was made during the hype of Al Gore’s documentary, An Inconvenient Truth. It tries to take us into the vortex of global warming, rain forest destruction and other environmental crises, although the elaboration of the work’s theme is not quite clear.

The almost naked man bends at the knees and crosses his hands in front of his chest, mimicking the flapping wings of a bird and symbolising hope or, perhaps, the birth of life itself. At first this ‘bird’ flies slowly and then faster and higher, so high that the man must let it go.

In another scene the stage becomes almost red, as if something bad is taking its course. The man squats as if great pressure is being imposed upon him, his hands pulled back, his face in grinning as if in pain. He bends lower and lower, moving slowly, meticulously transforming his pose, making the working of his muscles visible—a movement tradition rooted in the dance of Topeng Panji (Panji Mask) of West Java.

Towards the ending of Merah, the man wraps his body around the woman like a belt or a snake which she accepts with strength and without complaint. She bends as a vest descends, partially covered with broken mirrors. The man climbs onto her back and slips into the garment, scattering light through the theatre.

For the choreographer perhaps the male figure represents the human species while the woman is nature, bowing to man and subject to destruction. All aspects of the performance—its stillness, the low lighting and slow movement—conveyed haunting imagery if not making the work’s meaning finally clear.

Merah

photo Phalla San

Merah

WHEN THE LIGHTS BLACK OUT IN INSTITUT KESENIAN JAKARTA’S TEATER LUWES ON THE SECOND NIGHT OF THE INDONESIAN DANCE FESTIVAL, AN ENVELOPING DARKNESS BLANKETS THE ENTIRE SPACE. IT’S EVEN MORE SUFFOCATING AS WE AWAIT MERAH, THE SECOND WORK ON THE PROGRAM. SOUNDS THAT YOU WOULD NORMALLY HEAR IN A FOREST OR JUNGLE IN THE DEAD OF NIGHT PIERCE THE DARKNESS. BUT WE SEE NOTHING, EVEN AS THE FAINTEST SLIVERS OF LIGHT GLOW ON THE STAGE.

The dancers are only very slightly illuminated by a smattering of light on the cyclorama that simulates moonlight shining through thick leafy branches. Because we had been in the darkness so long, I was not even sure if the second dancer, situated in an upstage corner, was indeed actually there; he seemed to blend into the cyclorama so much that my still-adjusting eyes were convinced that he was merely an image projected on the screen.

The other dancer, whom we later discover is Merah’s choreographer, Asri Mery Sidowati, stands at the opposite corner, nearer the audience. She is covered head to ankle in a shiny, metallic body suit. In contrast, the dancer upstage, who is not a hologram after all, is stripped down to the briefest of briefs. As he jaggedly moves to the sound of crickets and birds rustling through the night, it becomes obvious that he is meant to be of the earth—a primal version of man—while the figure wrapped in metallic cloth, who very slowly yet continuously moves her cradling arms in patterns around her body, might very possibly be otherworldly, a spirit but also possibly an alien. Given the costuming and my lack of knowledge of Indonesian mythology, it is difficult to determine which.

The male dancer has the more interesting movements: flexing and undulating, posturing sporadically in between, darting, flicking his fingers, shoulders and head almost as if in reaction to the sudden chirp of a cricket. After an eternity of this minimal movement from both figures, they edge towards one another, until they stand side by side with their feet wide apart. Together, they pull their heads back into a circular sweep, the man with his back to the audience, shoulders rippling with muscles as he does. Shortly after, they enter a common sphere, the man reaching for the wrapped figure and slowly wrapping himself around her midsection so they become one—an image sustained a little too long but allowing time for speculation. The man is not afraid of this otherworldly being, who, in return, readily accommodates him. After the performance, I overhear that she represents Mother Earth, but this didn’t occur to me at all since she moved into his space, merely visiting the world that he inhabited.

I see her instead as an external entity, and the male figure’s act of attaching himself to her as an exercise in empowerment, a kind of calling upon divine forces for strength. He climbs up on her back and is immediately garbed in a mirrored vest—a triumphant acquisition of power, exhilarating and uplifting, the glass shards flashing light over stage and audience. This invocation of a deity ends in triumph and frees man from the overwhelming, suffocating darkness with which the work began.

Later, however, I read the program notes and am entirely confused. It seems that Asri choreographed Merah as a commentary on Global Warming; the correct reading of the work would then be that grasping Mother Earth and stepping on her would be some form of abuse that she endures and even allows. The mirrored vest can then be read as an explosion of sorts—if we step on Mother Earth, we must be ready for the consequences. However, the work did not translate this threat clearly and, as I’ve pointed out, the tone of the ending was more inspiring than ominous.

Audiences may take whatever they wish from a particular work, and whether Asri likes it or not, her message will not always come across as intended. I applaud Merah’s journey from darkness to light, from gloom to triumph, and the slow, measured, unremitting pace that it took to get there.

![S]h]elf](https://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/36/3671_giang_shelf.jpg)

S]h]elf

photo Phalla San

S]h]elf

IN THE MILD BLUE LIGHT OF THE DIM STAGE, TWO YOUNG WOMEN IN WHAT LOOK LIKE SWIM SUITS CRUISE ON WHAT APPEAR TO BE SHORTENED SURF BOARDS FRINGED WITH BLUE LIGHTS. SPINNING, GLIDING SOUNDLESSLY ON THE FLOOR, IT LOOKS LIKE AJENG AND ANGGIE ARE FLOATING IN A SWIMMING POOL, ENJOYING THEMSELVES ON A STARRY NIGHT.

S]h]elf, a collection of loosely bound short episodes, opens the second night of the 10th Indonesian Dance Festival. Next, the protagonists are busily quarrelling. Exchanging extra-large t-shirts they are soon entangled. Awkwardly bound they mouth Barbie doll interactions of the “I love you, but I hate you too” and the “Get away, but don’t leave me alone” kind. Welcome, say the program notes, to the world of South Jakartan, affable, middle-class youngsters.

Another scene has Anggie moving slowly from the periphery to centrestage, stopping after each little step, upper body leaning, shaking uncontrollably. Only her feet and fists are held firm, as if she wants to run away but can’t. She grimaces: is she crying or laughing? Is she drugged? It takes her an eternity to reach the front of the stage. Looking straight at the audience, she burps. “Give me a break. To hell with your social conventions,” she seems to say. In another episode, Ajeng turns a roll of toilet paper into a mock camera, ‘shooting’ the dozens of people in the audience whose cameras have produced endless clicking ever since the performance commenced.

Performed by Ajeng Soelaiman (born 1984) and Andara ‘Anggie’ Firman Moeis (born 1986), and choreographed in collaboration with Fitri Setyanigsih (born 1978)—all rising stars of the Indonesian dance scene—the work is fun, unfussy and has an air of ironic coolness. The set consists of two mobile glass revolving doors and metallic cubic frames hanging low from above, suggesting the worlds of entertainment and shopping. The performance is a self-portrait; drawing on their own lives the women play themselves, and they do so convincingly, with touches of self-irony.

What does it mean to be female, young, well-off and sophisticated in a Muslim society? At one point, Ajeng uses lipstick to draw a heart on glass, but her hand slips and the drawing becomes a confused mess of lines. Later, she stands in front of a glass door, facing the audience, in full evening dress. Radiating an amiable elegance, she bends to one side as if is about to dance. The music is a soothing, chill-out waltz. Gracefully, she raises her hand and gives the audience the finger. Or is the glass frame actually a mirror, and is she signalling self-disgust?

Whether rebellion or self-examination, it’s a fleeting gesture. At the end of the work, the two young women stand around a table of wine glasses, as if at a party. While Ajeng plays with two glasses, bored, pouring wine from one to another, Anggie, in a continuous slow motion loop, drains the dark content of each glass in a mouthful, throws the empty over her shoulder and reachs for another. There is no loud smashing of glass, no emotional crisis, no theatrical breakdown, just the embracing comfort of boredom. It’s the end of the party. Too tired for anything wild, the pair choose to stay in air-conditioned comfort, souls numb, surrounded by broken glass and broken hearts.

The Young

IN THE FINAL MOMENT OF THE YOUNG, A BOY AND A GIRL FACE EACH OTHER, BOTH WEARING A SNEAKER ON ONE FOOT, A SNEAKER ON ONE HAND. IN THE SILENCE YOU CAN HEAR THEIR PANTING. STRIPPED OF THEIR GRASPING AND POSTURING, THEY SEEM TO ACTUALLY SEE ONE ANOTHER FOR THE VERY FIRST TIME. THEN, TOO QUICKLY, THE LIGHTS CUT OUT.

To get to this final point of undemanding honesty, the dancers in Muslimin Bagus Pranowo's duet have to scrabble through a thicket of teenage angst. In a scene as bleak and empty as a nightclub after closing time, the two battle for the many pairs of sneakers littering the dim stage. The girl, performed by Maharani, wears the drainpipe jeans so favoured by the young. Hard eyed and hard mouthed, she gives as good as she gets. Being the first to wear one sneaker on her foot puts her in command. Wearing two sneakers, she assumes a tough-guy nonchalance, folding her arms and leaning on the boy as if on a sidewalk lamp-post, he bending in acquiescence.

The fast, aggressive movement, accompanied by a choppy and harsh electronic score, full of loud squawks and scratches, did not allow much leeway for subtle emotional expression. Nevertheless, the boy, performed by Muslimin, comes off as the more indecisive and piteous character, undermined by sexual frustration. Early in the work, he reaches through the girl's legs from behind and grabs her crotch, a gesture of aggressive lechery that she completely ignores. Later he fends the girl off and goes for a shoe, only to suffer sudden performance anxiety. When the girl lies on her back, sneakered feet in the air, he performs a short solo of agony; it is deliberately unclear whether he lusts after the girl or the shoes. When he finally does claim his own pair of sneakers, they fail to make him happy; rather than acquiring a sense of confident adulthood (feigned or not) as the girl did, he continues with the jumping, rolling, charging movement as if nothing has changed.

The sneakers are objects of fetishization, whose overt use—to protect feet—is overshadowed by their symbolic value: the possession of coveted material goods, the construction of an individual identity, maturity or sexual attractiveness. When they first encountered the shoes, both boy and girl were similarly perplexed. They seemed not to know what they were for, wearing them on their hands and pressing them to different parts of their bodies. What should be a display of bad breeding (proximity between shoes and heads in Asian cultures being extremely rude) is rendered instead as a moment of quiet intimacy. With the shoes to separate them, the pair touch each other as they otherwise cannot. Simultaneously, the thumping score descends into radio static, displacing the scene from the pressure of normal life. Suddenly realising what they are doing, the dancers freeze, then break away.

The movement vocabulary of The Young is appropriately transnational, almost unplaceable, but more similar to Western contemporary than any Indonesian cultural dance. Only one moment locates the movement within a distinctly Indonesian idiom. The two dancers crouch, proffering a sneaker with both arms fully extended towards the audience, their heads ducked down between their shoulders. In this stance one might present an offering to a king, especially if one had done something very wrong and was appealing for forgiveness. Oh, figure of authority, the dancers seem to plead, take away these shoes, this source of rancour and unhappiness that tortures us! But it is only a moment quickly washed away in an unrelenting wave of movement.

At 25 years of age, Muslimin already shows an easy ability to manipulate a variety of cultural movement vocabularies. The video projection element in The Young, however, was too diffuse and brief to have much impact, but the performers were confident and skillful, and the work explores a tightly coherent theme with insight and maturity. As part of IDF 2010's opening night, The Young is a strong representation from its namesake cohort as well as an illustration of the festival theme “Powering the Future.”

5,6,7,8

photo Phalla San

5,6,7,8

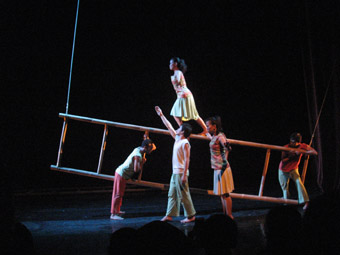

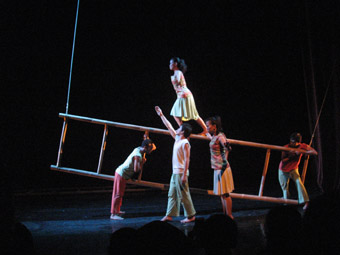

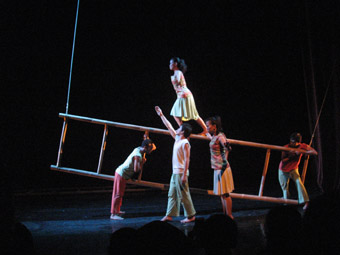

THE 10TH INDONESIAN DANCE FESTIVAL PROGRAM OF WORKS BY FIVE EMERGING INDONESIAN CHOREOGRAPHERS FOCUSED ON PERSONAL ISSUES INTERTWINED WITH THE VALUES AND NORMS OF INDONESIAN SOCIETY. THE CHOREOGRAPHERS COME FROM ART UNIVERSITIES AROUND INDONESIA: THE JAKARTA ARTS INSTITUTE (IKJ), ISI YOGYAKARTA AND UNESA IN SURABAYA.

Nur Sekreningsih Marsan’s 5,6,7,8 elaborates one person’s journey and their relationship with others. With ladders as the principal stage properties, the dancers are often placed in challenging circumstances. One part of the work requires two dancers to walk along the narrow length of the side of a ladder, the delicate balancing reflecting the difficulties faced in relationships.

Cekrek (Click) by Joko Sudibyo opens with a scene where a woman wearing a blue kebaya top and batik cloth sits down in the middle of a group in dim blue light. Her hair is pulled back and rolled into a big bun. It’s a look preferred by most Javanese mothers when posing for a family photo. Four young men wearing long sleeved white shirts stand before her. Slowly and gracefully, the woman stands. Gently moving to the right, she performs the subtle hand gesturing of Javanese dance. But as soon as she leave the stage, the four boys move about dynamically, the mood shifting from tradition to modernity.

This shift and its reverse occurs several times in Cekrek: in the next scene another man appears, bare-chested and wearing a batik sarong. He moves in traditional Javanese fashion with special precision and fluidity while the four boys circle around him. He then performs a duet with the woman in the blue kebaya before exiting. If she is an idealised mother the man appears to be a missing father figure.

Cekrek

photo Phalla San

Cekrek

Next, another woman appears. Wearing a red tank top and batik skirt, she weeps with over the top exaggeration, complaining how hard she works and that the men in the family have done nothing to improve its condition. She represents the real life mother who is often frustrated by the family hardships.

Near the end, the idealized mother reappears, putting an abrupt halt to a chaotic situation. The real mother contains herself. The four boys tuck in their shirts, poke each other as though wanting to show the mother who’s to blame, and solemnly form a line with their mother. The idealized mother slowly sits and pulls out a camera. Without being commanded they all smile comically and wave politiely as their picture is being taken. One big happy family.

Cekrek very simply suggested the importance of the mother in a family. Her nonchalant presence is crucial, creating harmony while her absence yields chaos—a belief firmly held by most Indonesian families. The successful fusion of traditional and modern movement and its simple imagery made the dance a delight to watch.

Gayaku

photo Phalla San

Gayaku

Shinta Maulita’s GAYaku focused on homosexuality. This piece couldn’t be more appropriate considering the current situation in Indonesia where the gay and lesbian movement is gaining momentum.

GAYaku opens with three men and a woman seated in a circular formation beneath another man sitting on top of a round platform. Squatting cross-legged, he flexes his right arm, making a gestures like those of deities in Hindu temples, while the other dancers circle him.

Live gamelan playing thickens the traditional ambience, with a male singer chanting in Javanese “a woman should be with a man; how it would be when a man decided to pair with a man, and a woman with a woman?”

GAYaku depicts the joyous decision of the men to embrace their sexual identity. Four men gather again in a circle, this time wearing glittering bamboo hats commonly used as rice baskets. They shake their bodies coquettishly, while forming a circle facing each other. One gestures as if applying make-up, his other hand holding an imagined mirror.

The festivities move into over-the-top celebration as the dancers invade the auditorium, shaking their bottoms. This “We’re gay and we’re proud!” mentality reflects life in many big cities in Indonesia where more and more men and women daringly come out, ‘boasting’ their gayness.

The last two works in this program were Retorika Kerinduan by Santi Pratiwi and Bunglon by Serraimere Boogie. The first is about urbanization, and the yearning to return to village life, while the other elaborates on the ability to adapt. Bunglon involved Papuan costume and a merging of Javanese and Papuan movement.

Overall this showcase of works by emerging choreographers demonstrates the effectiveness of dance education in Indonesia. It is also refreshing to see that tradition plays an important part in the work—having strong roots is always a good place to start.

5,6,7,8

photo Phalla San

5,6,7,8

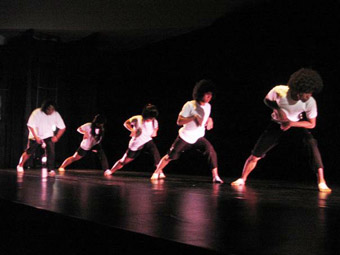

WHAT? WHY? HOW? THE EMPTY STAGE IS A BLANK SLATE WHERE FIVE YOUNG INDONESIAN CHOREOGRAPHERS (FROM ART UNIVERSITIES AROUND INDONESIA: THE JAKARTA ARTS INSTITUTE (IKJ), ISI YOGYAKARTA AND UNESA IN SURABAYA) MAKE THEIR MARK. AMIDST MUSICAL CACOPHONY AND THE BLUR OF LIGHTS, LIKE ANYONE IN THE EARLY STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT THESE EMERGING ARTISTS SEE PATTERNS, QUESTION STEREOTYPES AND TRY TO FORGE IDENTITIES.

5,6,7,8

In the language of the dance world 5,6,7,8 means prepare. And you should, when a cycle of beginnings commences the moment the lights reveal two men bursting into explosive kicks and jumps to the creaking sound of straining wires. A ladder, over which the men move quickly and deftly, lies inertly on the floor beneath their feet.

In Nur Sekreningsih’s 5,6,7,8, sound loops shift from the resonances of traditional instruments to running notes on the piano to concrete sounds and back again. This musical history is mimicked by the dance movements, rotating between traditional, contemporary and folk, a formal construction that underpins the work’s theme: the cycles in relationships.

The dancers cover the space well with energetic leaps, conveying a strong sense of motion and interaction. Set higher and higher—on its side, sloping, suspended above the shoulders—the bamboo ladder allows varying forms of engagement and framing but is also a hindrance. The dancers are entertaining when they jump through the rungs or hang from the ladder’s uprights but, unfortunately, the increasingly precarious ‘tightrope’ act, performed at each level of the ladder’s positioning, misses the mark. The spectacle of the balancing act as the performer teeters on the edge of the ladder detracts from the image of the dancer as forward-looking—she is more tentative than progressive. Nor is it clear how this image of isolation relates to the cyclical nature of relationships.

Cekrek

photo Phalla San

Cekrek

cekrek

Exploring how family dynamics can affect identity, Cekrek is the poignant and humorous highlight of the showcase. Choreographer Joko Sudibyo’s choreography is an expert fusing of styles in which the wide stance, flexed feet and soft arms of Balinese dance combine with a jazzy influence evident in undulating bodies and quick rebounds off the floor. The all male cast confidently perform the steps, exuding a youthful precociousness that makes me smile.

Posing for imaginary portraits, four youths, neatly dressed in short sleeved, white collared shirts and brown trousers—a typical school uniform—freeze each time the lights flash. They are oblivious to the mother figure kneeling directly in front of them, her back to the audience displaying perfectly coiffed hair pulled back in a low bun and the blue lace of a Kebaya (blouse).

This woman rises gently and moves off-stage, the performer’s masculinity barely discernable, so delicate and poised are his movements. The eyes of the boys are glued to her as she exits but her absence releases them into a series of body waves—head, chest, belly, hips, lifted in successive sequences. They horse around, pushing and gesturing, isolated heads moving quickly from side to side, pointing (mostly with the middle finger), jabbing and thrusting, painting the air around them—their movements still suggestive of traditional dance. The boys appear to revel in their independence.

Is the bare-chested dancer who enters next a memory of an absent male authority figure? The four crouch around him as his back and extended arms move in sinuous ripples, as if jolts of electricity run through his veins. The ‘mother’ returns to the stage, and he dances with her in a strange duet, the relationship appearing to be that of human and ghost. He navigates the space around her, never making contact as she, seemingly unaware of his presence, makes her slow progress across the stage to exit. Then he too disappears.

Another female character enters, also a male dancer, this time with long wild hair, a pink tank top—showing off chorded muscles—and a traditional long cotton skirt tightly wrapped around the legs. This woman is a caricature, like a soap-opera mother. Unlike her silent counterpart, she wails melodramatically, stops abruptly turns to the audience, says she’s been “crying for three days” then resumes her squawking, half-dancing, half-sobbing around the stage.

Trying to shame the boys into reaction, this single mother (the program note explains that the woman is the family’s breadwinner) pulls her hair into a mad tangle, tossing and flicking it every which way, shouting in Bahasa that she deplores their ingratitude, for never thinking about her or the family. She yanks their heads back as she scolds and cajoles, but they ignore her, remaining inert, eyes closed. Later they gather behind her as she continues to jabber, pointing and gesticulating; naughty children mimicking a scolding parent.

Somehow order is restored when the genteel Kebaya-clad mother returns: the boys shuffle away, straighten their clothes and line up with the wild-haired mother. Suddenly, the genteel mother whips out a camera. Pasting on cheesy grins, cranky mother and sons pose for a portrait—the illusion of a happy family.

Gayaku

photo Phalla San

Gayaku

gayaku

This night’s program seems to be a re-contextualising of traditional Indonesian dance forms within a modern framework. Nowhere is this theme as clear as in GAYaku which starts quite traditionally—a man sits cross-legged, meditating on a shoulder high table under which people sit like ancient sculptures. From the edge of the stage traditional musicians play a haunting gamelan melody and chant in eerie unison. The dancers move through the strong poses characteristic of males in Javanese dance.

Part-way through, round gold, helmet-like hats with a protrusion on the crown are worn, then playfully cupped against chests, thrown in the air and turned upside down like bowls—Freudian symbolism perhaps of dual sexuality. Exploring the freedom of new gender identity, the male dancers perform traditional Javanese female movements; using soft fingers, vainly admiring imagined reflections, taking tiny, demure steps, they move the work to its campy ending.

To reach this freedom there must first be a moment of crisis. In the program note, female choreographer Shinta Maulita, writes, “I try to love the person I am supposed to love…but I can’t.” This might indicate that GAYaku is about Maulita’s frustrations, but it’s about much more. In a pair of duets, a male dancer partners Maulita. As they face each other, legs wide apart and hands outstretched, this traditional Javanese dance movement becomes the basis of missed kisses as the dancers’ faces bob and weave. The key image is of Maulita cradled, like a bride about to be carried over the threshhold. Lips almost meet but her partner’s eyes shift away, an expression of anguish and regret on his face. A male-male duet ensues, the dancers circling each other, legs moving closer but bodies stretching away in hesitation. In the end they embrace, faces frozen inches away from a kiss. Maulita’s work has brought the audience to the brink of a transition but by not taking the final step she keeps the work in the realm of pretense, and leaves the rest to the imagination.

In GAYaku, traditional movement becomes sexually charged: a basic shoulder roll, usually delivered slowly and with care, becomes a seductive shimmy; the wide legged walk with gentle hip sway turns into a booty shake as the dancers gyrate to the rhythm of the music. Finally, moving among the audience they blatantly flirt and tease, questioning and inviting.

Retorika Kerinduan

photo Phalla San

Retorika Kerinduan

retorika kerinduan

Retorika Kerinduan is Santi Pratiwi’s discourse on increasing urbanization and the inability to assuage a longing for the old village life. A body is lit in the centre of the stage, no head or legs, just a back, naked but for streaks of metallic gold paint, pushing and heaving to ominous grating sounds. It is a man struggling to rise; distorted arms pushing outwards, he appears to be hatching from an egg. From deep in his throat come strangled sounds as he gasps for air. Kneeling in a semi circle, three women slowly bow their heads to the ground and, returning to the upright position, ritualistically repeat the movement. Perhaps the choreographer suggests that the worship of money is suffocating.

Near the middle of the work an image of human devolution appears. Almost as a footnote to a series of martial arts inspired, middling lunges and quick jabs, three dancers enter at varying heights, ranging from upright Homo Erectus to crouching monkey. The final image is of a silver robed figure with a cardboard box—shaped to represent a sky-scraper—on his head, a woman at his feet. Behind him the trio of women move as if in a funeral procession, dropping brittle brown leaves, mourning encroaching urbanisation.

bunglon

The final work, Bunglon (Chameleon), is an oblique criticism of the hypocrisy and Machiavellian attitudes of opportunists in politics and entertainment expressed through a mashing of cultures. The dancers are adorned with feathery headpieces and similar arm-bands. In a nod to hip-hop couture they hike up one pant leg and near the end of the work add a sneaker, while painted flames—vibrant tribal-like tattoos—lick up the sides of their exposed calves. Serraimere Boogie Yasson Koirewoa’s choreography is a reflection of this blending—hip-hop grooved traditional dance gestures. The images are not particularly symbolic but the permutations of movement formations suggest the easy adaptability of a reptilian species.

The movement language of the works in this program may not have been particularly original and I’m bemused by the overabundance of images and occasional mixed metaphors. Most of the pieces rambled in their search for cultural and individual identity, but this is a forgivable short-fall in the work of young choreographers. They were well served by a high level of physicality and commitment from all the dancers. These choreographers are off to a good start in defining their styles. Perhaps I was impatient only because youthful confusion is catching.

Darkness Poomba

photo Phalla San

Darkness Poomba

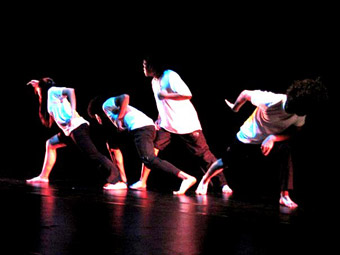

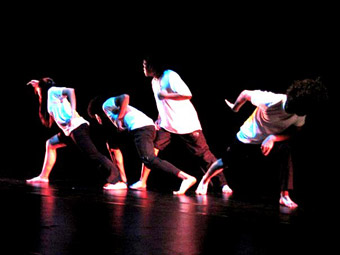

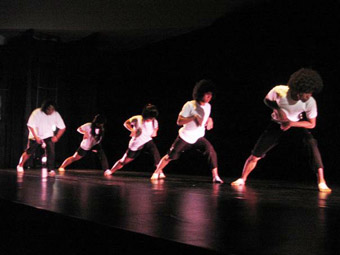

DARKNESS POOMBA BEGINS WITH TWO MEN STANDING STILL IN LOW LIGHT. ONE PLACES HIS HAND ON THE OTHER’S FACE; HIS COUNTERPART RESPONDS WITH THE SAME GESTURE. THE INCREASINGLY FAST ACTION BETWEEN THE TWO IS ACCOMPANIED BY THE STRONG VOICE OF A SINGER OCCUPYING THE SAME SPACE AS THE AUDIENCE. HE PERFORMS A TRADITIONAL WORDLESS SONG USED FOR FESTIVE OCCASIONS AND ALSO BEGGING. SUDDENLY, STRONG LIGHT REVEALS DANCERS RESPONDING WITH LIVELY MOVEMENT TO POWERFUL RECORDED MELODIES AND THE LIVE SINGING. BRIGHT LIGHT ALTERNATES WITH SOFT AND THE DANCERS MOVE SLOWLY TO THE FORCEFUL RHYTHMS OF THE SINGER. AT THE END LIVE ELECTRIC GUITAR, BASS AND DRUMS COMBINE WITH THE POWERFUL DANCING TO GENERATE A GREAT SENSE OF EXCITEMENT.

This is Darkness Poomba the last of four contemporary dance works performed to celebrate the opening of “Powering the Future”: the 10th Jakarta International Performing Arts Festival (IDF). The audience cheered, clapped and rocked to the 11 young dancers, musicians and vocalists from South Korea directed by choreographer and composer Kim Jae Duk who also performed as dancer, musician and singer. The combination of elements was dynamic and vigorous—while my hands were busy taking notes, my head and torso unconsciously swayed.

Beneath bright lights, the dancers committed body and limb to fast moves, shaking and leaping in a combination of modern dance, breakdance and acrobatics alternating with slower movement. From the moment the dancers were joined by the guitar players and drummer the work became larger and more dramatic. While the stage was filled with dynamic dancing, the choreographer joined the singer in one aisle of the theatre, singing and playing a mouth organ, while the two men who opened the show repeated their slaps and grabs at speed in the other aisle. The audience clapped and swayed, screaming their satisfaction.

The perfectly synchronized dance movement in Darkness Poomba and the beautiful and powerful live music made for an attractively dramatic and dynamic work. Although titled Darkness Poomba, the strong lighting not only distinguished between scenes but also suggested a brighter spirit.

Darkness Poomba

photo Phalla San

Darkness Poomba

AN EERIE, LOUD NOISE WAS HEARD DURING THE INTERMISSION FOR THE OPENING DAY’S MAIN PERFORMANCES AT THE 10TH INDONESIAN DANCE FESTIVAL (IDF). PERHAPS IT NOT ONLY SIGNALED THE AUDIENCE TO RETURN TO THEIR SEATS, BUT ALSO HINTED THAT KIM JAE DUK PROJECT’S DARKNESS POOMBA FROM KOREA WOULD LOOK AND SOUND VERY DIFFERENT FROM THE INDONESIAN CONTEMPORARY DANCE WORKS IN THE FIRST PART OF THE EVENING.

As the house lights dimmed and the curtains parted, we saw an electric guitar and bass on either side of the front of the stage, and upstage centre a drum set—to the delight of many dance audiences who prefer live to canned music. No musicians though. As two dancers moved downstage centre, we became aware of a singer behind a microphone in the house right aisle. The lyrics were in Korean, we thought, and that’s when some of us couldn’t help ignoring them, despite the singer’s vivacious hand gestures. And so music might suddenly become noise. Later on, the musicians took their places and, for a brief moment, the dancers stopped moving, giving the focus to the music.

Most of the time, though, the performance was multi-focus, attempting as it did to involve the audience—one dancer came down from the stage and up the house right aisle to sing and play instruments, while another two used the left aisle as their main stage. We were encouraged by the performers to clap along, and many of us did, and that’s perhaps when we felt we might have forgotten some dance-going etiquette. Then again, such restraint was established by Western classical ballet companies, and this is Korean contemporary dance.

Darkness Poomba is an example of how a unique intra-cultural experiment has led to engaging contemporary performance. This is thanks, in major part, to the fact that the choreographer and composer Kim Jae Duk has found, and emphasized, links between contemporary dance and an ancient singing tradition, Poomba—in which rhythm plays a stronger role than lyrics which, as a Korean tourism website explains, don’t mean anything. Although the performance was explained in the festival’s printed program as “composed of 70% of dance and 30% of music”, the union of the two was such that it became “100% of contemporary performance” which reminded us of the relationship between dance and music, and how artists have been trained concurrently in many disciplines thoughout the history of many performing arts traditions.

It’s perhaps also another reminder that although many Asian contemporary choreographers look to European and American counterparts, sometimes they can just look back to, and ‘re-search,’ their past. It may also be confirmation that although ‘modern’ equates with Western in many Asian countries, ‘contemporary’ is totally different.

Presented at an international festival, Darkness Poomba may also trigger our curiosity about the Poomba tradition. As the tourism website suggests, we can visit the National Pumba Festival every year in the town of Eumseong, to see and hear how the actual traditional street performance with funny make-up and costumes, or Lightness Poomba if you will, lifted up Korean spirits in poverty-stricken times.

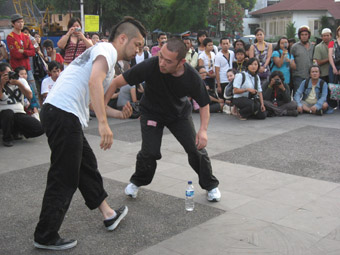

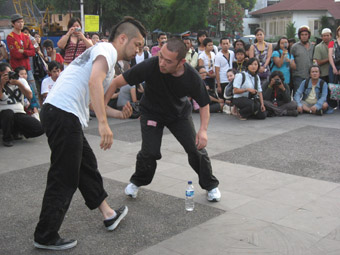

Contact Gonzo and Sayaka Himeno, public space

photo Phalla San

Contact Gonzo and Sayaka Himeno, public space

A few hours earlier, it was a young Japanese group contact Gonzo’s street dance performance that served as the soft opening—and a fitting one indeed—for the four-day festival. As about 100 people gathered around Plaza TIM, at the entrance to the host institution, noise from a bustling Jakarta street provided ambience that thematically fit the highly physical performance that was reminiscent of the street fights that takes place daily in many cities around the world. This was complemented by exuberant drumming, on a drum kit, by a female musician who, interestingly, rarely glanced at the four male dancers chasing and attacking—without actually hurting—one another. And occasionally we heard water bottles dropped and rolled around the cement floor. And unlike in Poomba, this soundscape didn’t set the rhythm of the dance, but rather added to the street ambience and the meaning of the piece.

Of course, many of us are still delighted to see contemporary dance works set to European classical music played to a live audience on CD, but, as a connotation of the term ‘contemporary’ suggests, there are also many other possibilities. After all, unlike theatre which is usually associated with, and powered by, spoken word that limits overseas exposure, contemporary dance speaks with body movements and music, or, as in these two cases, noise.

Darkness Poomba

photo Phalla San

Darkness Poomba

TWO MALE DANCERS IGNITE KIM JAE DUK’S DARKNESS POOMBA WITH A DUET PERFORMED BENEATH SEVERE TOP-LIGHTING. IT’S A FAST AND FURIOUS EXCHANGE OF ANGULARLY CHOREOGRAPHED MOVEMENT, HANDS MECHANICALLY GRASPING FOR EACH OTHER’S FACES AND BODIES REGIMENTED IN A FORWARD FACING STANCE. CREATING AN ILLUSION OF A ROBOTIC PAIR OF SIAMESE TWINS, THE TWO STYLISH YOUNG MEN ARE JOINED BY FIVE DANCERS CLAD IN CHIC BLACK SHARPLY ENTERING TO JOIN THIS MACHINE, EXPANDING ON THE GOTHIC ENERGY THAT HAS BEEN GENERATED.

A spot picks out a man standing with a microphone in one of the aisles. Ears and eyes are immediately drawn to this powerful presence and we are captivated as the space swells with his chanting of the traditional Korean Poomba (a wordless street song associated with both begging and festivities), evocative of desperation and yearning. Manipulated reverberation suggests that we are all inside a cold and mysterious vault of some sort, suspended between hallucination and reality. The performer displays extraordinary command of his instrument, and his sensitive commitment to the dancers on stage helps them to devote themselves to the dark abrasiveness of the space.

Later in the work, a dance with metallic dinner trays between the two male dancers who opened the piece brings an oddly domestic sensibility to the abstract world that has been established. The trays become percussive instruments as well as hats and items of clothing. The chorus of dancers behind them acts as a strata of strange shadows that morph from one contained image to the next. The dance is realised with crisp articulation and un-wavering performance energy as if the dancers are teasing out the dark underbelly of this work with a quiet ferociousness.

The darkness of this rich work is both deeply set in the bones of the performance and ironically woven into its surface. Even when the whole audience claps and sings in delight when the work turns into a rock concert, the haunting atmosphere never lets up. In fact it is in these ‘light’ moments that the gothic undertone is somehow heightened, demonstrating a sophisticated approach to the creation of atmosphere. Funereal organs and regular smoke machine emissions are both parodic and unsettling.

When choreographer and dancer Kim Jae Duk joins the vocalist in the auditorium and two electric guitarists play at either end of the stage, the traditional lilt of the Poomba becomes the wailing power of a rock concert, the guitars providing the metallic grit for the transition. The audience too has been transformed, from theatre spectators into a rock stadium crowd.

In a return to the opening duet, the two dancers perform a gradually accelerating version of the robotic Siamese twin dance down the aisle towards the stage. This phrase cleverly functions as the peak of the work, causing a kind of ‘Mexican wave’ effect on the crowd, evident in a vocal eruption. After the excitement has subsided, a gentle, virtuosic harmonica solo is performed by Kim Jae Duk, cleverly returning us to the work’s opening eeriness. As the creator lays his final delicate mark, the piece closes.

Not one sense is privileged over another in this haunting re-contextualization of the traditional South Korean melody of Poomba. In a truly interdisciplinary and multi-layered work, audience members are taken on a strange and unexpected voyage through the realms of contemporary dance, traditional song, stadium rock and festive reggae. Perhaps seeming schizophrenic and disjunctive in nature, this collage of performance genres is in fact executed seamlessly. Darkness Poomba is a work that manages to constantly transform our environment before we have even noticed, each new world functioning as a critique of the one that has come before.

contact Gonzo, Public Space

photo Phalla San

contact Gonzo, Public Space

FIGHTING ERUPTS ON A CONCRETE PLATFORM ON THE EDGE OF A BUSY JAKARTA STREET, FOUR MEN GRAPPLING WITH EACH OTHER, PILING BODIES INTO PRECARIOUSLY PERCHED PYRAMIDS, CONSTANTLY INVADING EACH OTHER’S SPACE, SLAPPING AND PUNCHING. THIS IS NO ORDINARY STREET BRAWL BUT A PERFORMANCE BY JAPANESE COMPANY CONTACT GONZO THAT PUSHES THE PERFORMANCE BOUNDARIES BOTH PHYSICALLY AND LITERALLY. AT ANY MOMENT THE PERFORMERS COULD SPILL INTO THE WATCHING CROWD, AN IMMINENT DANGER THAT FORCES THE AUDIENCE TO PHYSICALLY ENGAGE IN THE WORK AS THEY DODGE AND RECOIL IN ANTICIPATION.

This work was one of the two international offerings that contributed to the youthful exuberance of the 10th Indonesian Dance Festival. The other was Korean Kim Jae Duk’s Darkness Poomba, bombarding the senses with a fusillade of fast movement combined with loudly belted lyrics and a beat that had the audience swaying and clapping.

Equally engaging, the two performances could not have been more different in execution and philosophy. Contact Gonzo doesn’t employ many theatrical tricks for its street performance, just the performers, an unamplified drum kit and simple props—water bottles, caps and disposable cameras. Although part of a dance festival, the physical language used cannot be comfortably labeled; it more closely resembles sport than dance in its raw action and response. In contrast, Darkness Poomba employed a full range of theatrical devices; strong lighting states to highlight the action, sleek costuming to show off the dancers’ physiques, sound amplification and a self-conscious breaking of the spectator-audience divide.

Kim’s youthful energy as performer, composer and choreographer, drives the piece, particularly when he commandeers the microphone showing off his strong voice or plays soulfully on his harmonica. Self-described as 70% choreography and 30% music Darkness Poomba is both rock concert and contemporary dance performance, crafted to get the blood pumping and body bouncing. This is a “re-mix” of Korean Poomba music, a throw-back to when the country was impoverished and street singers roamed around to entertain in exchange for food and money, singing the meaningless but rhythmic word “Poomba.”

Darkness Poomba

photo Phalla San

Darkness Poomba

The work opens with two dancers lying limp in the centre of the stage. Suddenly they spring up, two young men, hair flopping over their eyes, dressed like dancerly beggars in earth-tones, they survey the audience then launch into a series of complex gestures, covering and uncovering their faces, then each other’s, hands threading through one another, then twining to catch hold and push their heads down. Imprisoned within the dark confines of the stage and the low groaning of the music, this depressed tone is short-lived because when the same sequence repeats some time later, it maintains the needlepoint accuracy yet, forced on by the driving beat and hyped up rock concert atmosphere it builds into a lightning speed that has the audience cheering.

Towards the end of the work the initial male pair re-appear moving metal dinner trays and bowls around with quick, concise movements and playing them as percussive accompaniment. Then like savage dogs they tear into imagined food, their beggarly appearance and hunger a reference to the history of Poombas.

The evocative, gestural movement vocabulary of the two sets them apart from the rest of the company, as Kim’s choreography for the black-clad dancers is a cross of liquid, contemporary movement and the aggressive energy of hip hop, that demonstrates strong ballet training without using a balletic vocabulary. The dancers are all long legs with broken torso lines and body distorting gestures that sharply accent the music and punctuate the strong beat.

Their figures perfectly synchronised, the dancers move as precisely as a well oiled machine. Bombarding the audience with speed of movement that denied emotional engagement, the physical prowess of the performers was admittedly inspiring. One male jumped high, smashing his leg into the air and completing a full revolution before landing, but did this stunt serve any other purpose than to wow the audience? The choreography was kinesthetically pleasing but not emotionally engaging.

It was the music that carried emotional resonance, particularly in the hoarse cries that emanated from the singer. This took on a life of its own as it travelled around the theatre, originating in one corner of the stage then moving to another, blaring and retreating like an auditory game of hide and seek. Later in the the work, a drummer sat centrestage, two guitarists flanked the stage and three dancers ran into the auditorium. They appeared to be escaping audience scrutiny but actually carried it with them, enlarging the performance space, if taking focus off the dancers remaining on stage.

One particularly powerful moment involving the pair of floppy-haired Poombas highlighted the challenge to the confines of the space. They threw themselves to sprawl flat against a side wall and then slowly peeled off. This was an undeveloped, token exploration of the space, part of an apparent mish-mash of images and ideas. However, in the spirit of entertainment that comes with Poomba, every moment was crafted to please, as when all action came to a stand-still and the drummer had his moment in the spotlight with a vibrant solo.

Contact Gonzo takes similar advantage of the power of energetic rhythm. From the first clang of the cymbals, the drummer is a dynamo of energy, going to war with the drum set. Echoing this aggression the dancers actually trade slaps, the smacking sound they create making the audience wince.

Aptly named after a style of journalism that is part fiction, part fact, in their performed battles Contact Gonzo negotiate a fine line between play and reality. Looking like young lion cubs in a mock hunt, they balance between careful control and risky stunts. With little formal dance training to share between them there is no polished technique, but a primal language of expression emerging from their improvised performances, making the action raw and naked. The construction of the movement revolves around the vigilance of the performers, highlighting the image of the hunt as they circle each other or attack with a sudden lunge or a slap only to be countered with paw-like swipes.