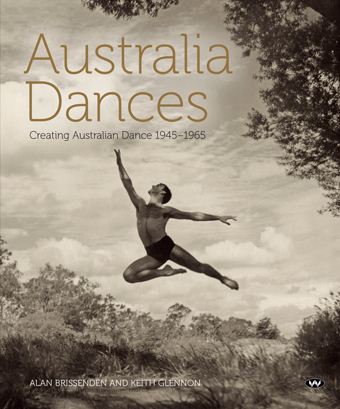

Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

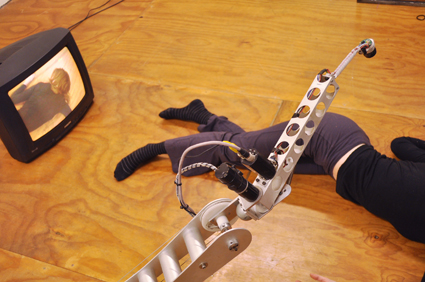

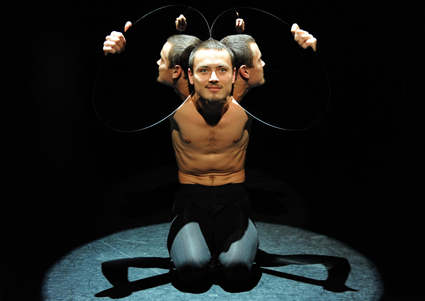

Carter & Zierle, Pearls of Sustenance

photo Carl Newland

Carter & Zierle, Pearls of Sustenance

PAUL HURLEY IS UP TO SOMETHING IN THE LIGHT STUDIO, WEARING A ZINC BUCKET ON HIS HEAD, FEELING HIS WAY WITH A SIX-FOOT STAFF, TEETERING ALONG THE BOUNDARIES OF THE ROOM IN A SAVAGE PAIR OF DANGEROUSLY HIGH GOLD STILETTOS, BLOWING THROUGH A REEDY METAL WHISTLE ON EACH EXHALE. SLOWLY. HE’S WEARING A WHITE VEST AND Y-FRONTS. I DIDN’T THINK YOUNG PEOPLE WORE THEM ANYMORE. THE FIRST FEW TURNS ROUND THE ROOM HE HAS TO PUT OUT A BLIND HAND TO GUIDE HIMSELF AS HE GETS NEAR THE WALLS.

paul hurley: untitled actuation

Near a pillar by the door there are five packets of Sainsbury’s jam doughnuts, sealed, two boxes of eggs, a packet of glitter, a newspaper, another bucket. By the second pillar are three pomegranates, a ball of string, scissors, a bottle of water, a chair with a note on it, a sack of peat. By the next pillar, another galvanized bucket, the skeleton of a parasol, a cycling helmet, a pair of red trainers, a towel, a bottle of red liquid and a packet of something I can’t see properly (it was a survival blanket). And by the last pillar, a Polaroid camera and film, four bunches of flowers in cellophane, a pair of wellies and some little bells. We must take off our shoes before entering the room and I assume this is for health & safety reasons. We shall see.

When I go in the second time Hurley’s kneeling on a sheet of newspaper cracking eggs on his head. He sprinkles glitter on himself. Looking at the dripping gold mess he’s blinking through, I think: pretty.

Sometimes it’s difficult to see all you want to of a durational piece. From the Reading Room I’d heard a tinkling of bells but was delayed. When I did get back in there were no more bells. Hurley had red paint all over his head and neck and was wearing a space blanket over his pants. Some peat had been spread on the floor in the centre. There was an imprint in it and from the dust on his vest, once he’d put it back on, you could see he’d spread out the peat and laid back in it. Smiling, he met my eyes and offered me a doughnut. And it was delicious, and JUST WHAT I WANTED—I’d had the craving since I first went in there. What had he done with the flowers, the water, the towel, the fan? Hints remained, traces on the floor and on his body.

Hurley took off the space blanket and put his vest back on and slipped back into the clumpy golden stilettos, forcing his toes right into the front of them, leaving a gap between his heels and the back of his shoes—the most uncomfortable way to wear high heels that there is. He put the bucket back on his head, started his whistling and resumed a wobbly circuit round the room, this time counter-clockwise. They do say sartorial choices imply interior states: thus, in Buffy, you have the black leather trousers of evil and the red leather trousers of moral ambiguity. Well, I guess Hurley was making his rounds on the dangerous golden stilts of altered states and inspiration: blind and extraordinarily vulnerable in his underwear.

Hearsay: he had attached the bunches of bells to his red trainers, walking round the room like an urban Morris Dancer. Hearsay: he’d held the flowers in front of the fan. Or had he planted them in the peat? Either way, he’d sought shelter under the skeletal parasol. I wonder what it was he did with the feathers? They were all over the floor in front of the fan.

What it was it with the staging posts, I wondered, the four pillars in the room—each furnished with a cache of supplies for a different stage of the journey? And was he going or coming back?

Someone who had been there at the end said Hurley had looked at him intently while tying a pomegranate to the string, attaching it to a pillar and setting it swinging. He had met Hurley’s eyes and they had looked at each other. It was a moment of extraordinary connection. He, the spectator, had gone to sit down by the wall, still observing the pomegranate. Hurley sat down beside him. They were side by side, companiable.

Someone else who had been there had had a feeling that the end of the performance was tied to the moment the fruit should stop swinging. That person watched Hurley and another spectator sit side by side observing the pendulum wind down. It was a moment of extraordinary contact.

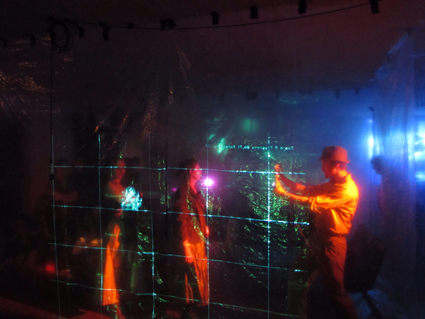

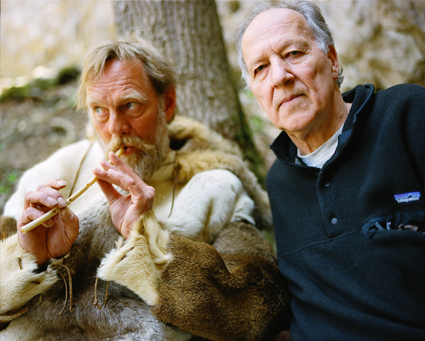

carter & zierle: pearls of sustenance

On the Saturday of Inbetween Time you might have gone up the stairs and noticed someone lurking anxiously, holding on to a pillar on the first floor. A slender person wearing a severe grey suit—not expensive, but with a very sharp look and a self-coloured stripe. After you had noticed the tension in her posture you would have seen that on this woman’s head was a castle-like structure composed of overlapping slices of white bread, like a big summer pudding, held in place with fishing twine and invisible adhesive.

Walking on a little way you might have noticed another person in grey lurking behind the lift. Again, the anxiety in him was palpable. His posture was suffused with hesitation, with longing, with a sense of reaching out and being held back by invisible obstructions, intangible barriers; his own weakness perhaps, or a sense of fear. He also wore a bread helmet. Physically he was very like the woman. They were a matching pair, both angular and hyper-sensitive, both with a restrained, conventional look about them. Even the bread-heads added to this sense: both characters, as it were, being muffled and baffled and under wraps.

The man began to edge round the corner past the lifts. Now it was possible for spectators to view both figures at once. She seemed stuck to her pillar as though it were an anchor, the only tangible thing in her grasp apart from the sense of her partner approaching. As though she couldn’t let go of it without falling into some sort of void. He, drawn by invisible strings, moved towards her hesitantly, inch by inch, once or twice sinking to the ground under all that stress.

Both of them shed crumbs: there was a Hansel-and-Gretel trail along his route towards her, while the trace of her own presence drifted sparsely to the floor of the foyer below. The tension between them was so extreme that people kept getting drawn into it; gradually the stairwell and corridor filled with people who couldn’t look away.

At one point she held onto the rail round the pillar with the hand that was behind her back, holding her other hand to her face as though she were studying her fingernails. Under the bread helmet she looked as if she were longing to let go of the pillar, desperately shy and lost. He moved towards her hanging onto the landing rail for dear life.

The last few feet of his journey were electrifying. She yearned towards him, he drew towards her, as though in their fearful state nothing was real but their sense of the other. They touched. She finally let go of the pillar. They stood together tenderly, slowly and blindly, exploring the other. They felt each other thoroughly, hands, arms, shoulders. They stood chest to chest with their hands trapped tightly between them. They explored the bread on each other’s heads. She began to crumble the edges of his helmet, and he to reciprocate.

Very slowly each began the destruction of the other’s mask. She rolled tiny little bread pills and dropped them to the landing below, stretching her arms wide. She uncovered his mouth. He uncovered her face. She began to feed him some of the pellets her enquiring hands had fashioned. By the time I left both of them had lost enough bread to be able to see the other’s face. They stood there in their bubble of mutuality at the top of the stairs: the attrition continued.

Helen Cole, Collecting Fireworks

photo Oliver Rudkin

Helen Cole, Collecting Fireworks

YOU’VE BEEN PUTTING YOURSELF ABOUT, HAVEN’T YOU? DON’T DENY IT. I’VE SEEN YOU. YOU’RE PUBLICLY AVAILABLE. YOU’RE FREE TO ANYONE WHO’LL HAVE A SLICE OF YOU.

Because it’s so easy to be everywhere. Everyone and their dog has a pocket-sized camera now. You can’t throw a rock without hitting a wireless hotspot. Most folks’ photo albums are visible to anyone who cares to do a half-arsed Google search. And maybe you don’t know it, but there you are: foreground or background, most often when you least expect it. A Flickr account of the back of your head at that gig you were at. School photographs on Friends Reunited. That really, really awful am-dram pantomime you were in? 3,647 views on YouTube, mate.

You’ll be online long after you’re dead. Cloned, copied, downloaded: it’s almost impossible to erase yourself from this ever-morphing tangle of digital connections. You can’t even make an unguarded comment at an Embassy dinner any longer without finding yourself on some sort of permanent bloody database. So there’s good and bad aspects to this whole thing. On the one hand: privacy is a myth. On the other: you will live forever. Swings and roundabouts.

Inbetween Time certainly isn’t helping you stay mortal. Because it seems this year, more than ever before, it’s focusing on YOU: your memories, instincts, personality, habitat. A plethora of works in the program contain no performance from the artist at all—instead they collect and compile. Photographer Manuel Vason is your co-conspirator in making a performance artist of yourself, creating your very own remarkable image. Blast Theory will phone you up at random, in the middle of dinner maybe, and ask you personal questions, recording your responses—which are then spliced with those of other volunteers and played back, in another city far away, to an audience of strangers. Helen Cole tends your performance memories with craftsman-like care, keeping them alive and thriving, as if each one was a rarely-blooming plant in a glasshouse.

Helen Cole, Collecting Fireworks

photo Oliver Rudkin

Helen Cole, Collecting Fireworks

helen cole: collecting fireworks

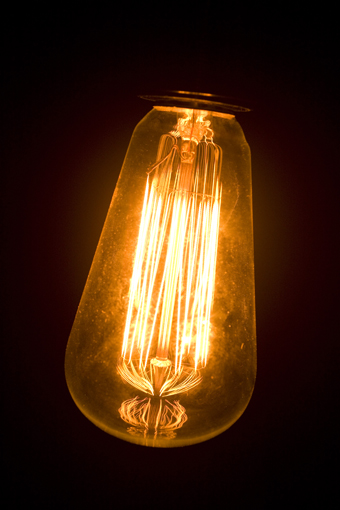

Cole’s Collecting Fireworks is a long-term project that makes audio recordings of people recalling performances long gone. As an installation it’s had many different incarnations (Inbetween Time finds it at the Cube Microplex, a rickety little venue with moth-eaten curtains and creaky stage), but wherever sited it has always been a game of two halves. First of all you sit alone in a very comfy chair, the lights fade and from the dark come voices recounting tales of performances, one by one. Alongside each voice the glow of a different lightbulb breaks the gloom, some close-up, some distant, some faltering and candle-like. Once this little constellation of stories has faded you’re led to a microphone and asked if you’d like to contribute your own memory.

Collecting Fireworks isn’t an academic compilation, it’s not a taxonomy of performance—the artworks themselves are rarely named, the contributors never, and amongst the theatre and live art some of the stories concern everyday urban incidents or moments that became theatrical in retrospect. In fact, being ‘tucked in,’ nestled alongside other peoples’ stories, means that the subsequent act of making your own contribution feels natural, unforced, community-minded. There’s a strong emotional undercurrent to the recollections you hear: themes of love and death predominate, and the contributors’ anonymity suggests the confessional or the support group. Faced with the microphone, I find myself speaking in the same quiet, clear, careful tones as those I’ve just finished listening to. In such unexpected ways Collecting Fireworks grows as an artwork as well as a document, its outcomes beautifully nebulous.

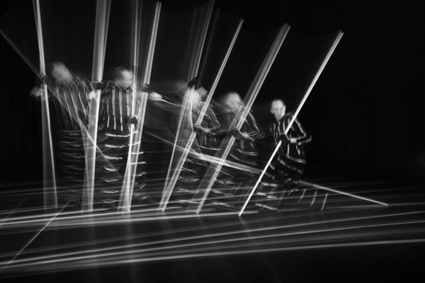

Manuel Vason, Still Moving Image

photo Manuel Vason

Manuel Vason, Still Moving Image

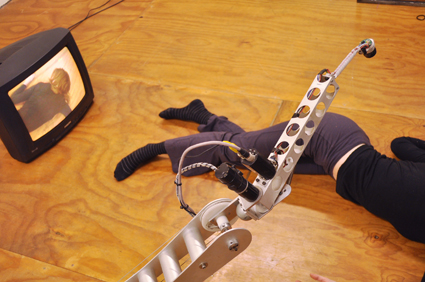

manuel vason: still image moving

Two other projects at IBT seem to celebrate capture, and both prove joyously life-affirming records of time and place, free-for-alls in which the inhabitants of Bristol make flesh of their thoughts: freakish, anodyne, political, fleeting or otherwise. In Still Image Moving, photographer Manuel Vason’s studio is a shipping container full of equipment that travels around the city, a sort of deluxe photo booth open to all—but the results are far from passport photographs. From the urban landscape spring tiny intimate moments and big, silly tableaux: the silhouette of a proud pregnant woman demarcated in vivid blue lights, the city in deep focus beyond; the pall of smoke from a recently lit cigarette making a lace shroud around a man’s face; figures half-buried in building sites, faces and bodies dressed in flowers and dirt, temporary monuments. Given the outlandishness of the poses most of them appear imbued with a tangible honesty, refreshingly happy. Each seems like a little song of liberation (even if, in the case of one suited gentleman blinded by his own tie and surrounded by a halo of mobile phones, they might also be a cry for help…).

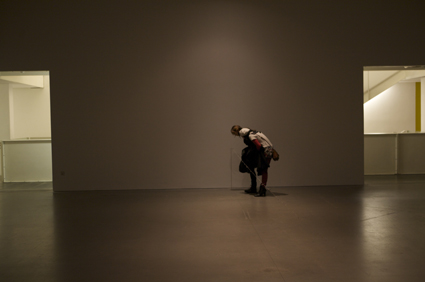

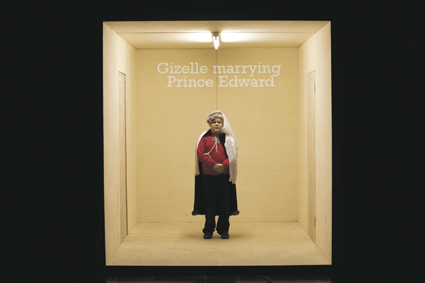

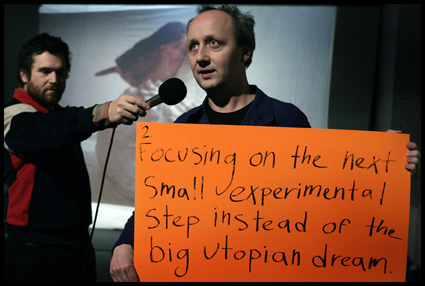

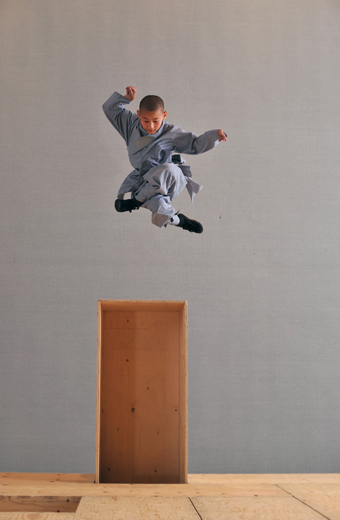

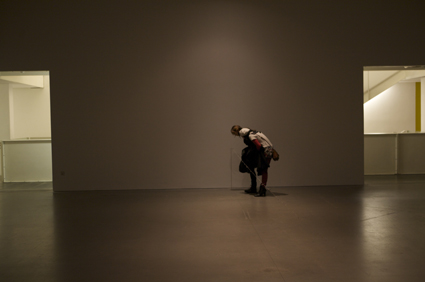

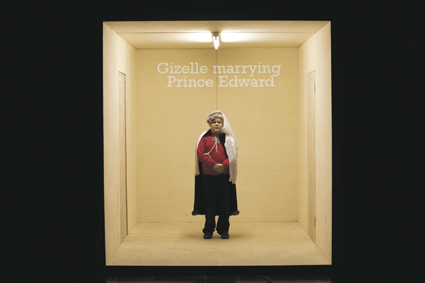

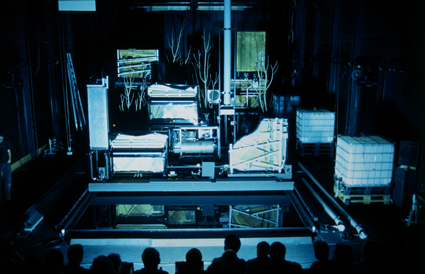

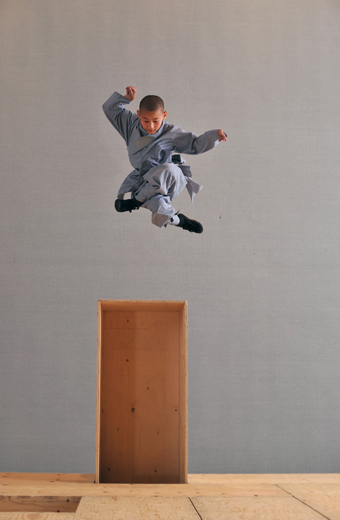

back to back theatre: the democratic set

The same qualities infuse The Democratic Set by Australia’s Back To Back Theatre, a film in which anyone can appear, for 15 seconds at a time, as a camera passes from right to left in front of a room-sized wooden box. (See previous iterations of the show above and here.) The results are edited to resemble a single tracking shot along a series of different rooms inhabited by individual or group performances. Balls of wool trundle through doorways, people tumble from frame to frame, some sing at us, others gaze mournfully as we pass by. Occasionally it’s like a dream sequence in a David Lynch film, disturbing, unstoppable. Sometimes it reeks of loneliness, people going about their business in some seriously fucked-up economy hotel. But mostly it’s full of laughter and hope, a feeling very much helped by the wide demographic of its contributors. Watching it at Arnolfini with an audience principally made up of the film’s participants is particularly rewarding, hearing their whoops of recognition, because more than anything else this film isn’t a monument to the producer or director—it’s really about the lives of this strange hotel’s inhabitants and the unique document they’ve created together. It’s a living trace of them.

duncan speakman & sarah anderson: our broken voice (a subtlemob)

Another participatory artwork occurs on a chilly Saturday afternoon in Cabot Circus, Bristol’s newest shopping mall (so sparkling and clean that, for the UK, it feels vaguely dystopian). Over the last few years Duncan Speakman has been experimenting with a variation on flashmobbing, where random mass actions in public places are instigated online and by text message. Speakman’s far less self-aggrandising Subtlemob uses the same means of dissemination but adds elements of subterfuge, so that unless you’re taking part there’s a good chance you’ll be unaware of any performance—unless you notice 100 people suddenly walking in slow motion or staring up at the empty sky in unison. The downloadable MP3 of instructions is an artwork in itself: created with the musician Sarah Anderson it contains a narrative text entwined with subtle instructions to the participant, and a glacial accumulative music score that would, alone, change the entire way you look at the Brownian motion of shoppers around you.

‘You’ are an actor in these events, called Alex, or Claire (or some other name I didn’t hear and will never know). ‘You’ gear up to, and perform, a single significant action and then leave the shopping centre, left to guess at the implications. But it’s the moments of unexpected coincidence that really make an impact, the points at which everyday life and Our Broken Voice collide, apt images and happy accidents that you alone are witness to. Wisely, the artists have left plenty of time and space in which these never-to-be-repeated moments can flourish. It makes me think of the dictum used by Brian Eno to define interactive art: “The word should not be ‘interactive’. It should be ‘unfinished’.”

Tim Etchells, Neon Signs

photo Carl Newland

Tim Etchells, Neon Signs

tim etchells: neon signs

Past sunset, the festival over: and the phrase “YOU WILL LIVE FOREVER” is emblazoned in neon lights, occupying a vacant window space at the bottom of the Christmas Steps, a quaint higgledy-piggledy stone stairway in central Bristol. Another similar sign on the lower curve of Park Street, in between newsagents and music shops, reads “PLEASE COME BACK I AM SORRY ABOUT WHAT HAPPENED BEFORE”… and inside the harbourmaster’s lookout on Redcliffe Bridge, if you’re distracted by the blood-red flickering light within, you can peer through the mucky glass to see the legend “FADING GLORY” on the concrete floor, crackling and failing.

I cross the street, standing at a safe distance to catch people’s reactions. Each sign is on a busy pedestrian route out of the city and most people are in far too much of a hurry homeward to see the messages. But every now and then someone peels off from the flow, and at each site I see at least one camera being produced, at least one picture being taken, to end up…where? Explained how? Ever retrieved? Recalled when? Because there’s no explanatory card tacked to these artworks, nothing to declare that they’re from the Neon Signs series by Tim Etchells. Nothing, in fact, to suggest that they’re artworks at all. It’s the simplest of acts, left to human chance: if you see the sign, you decide whether to care. If you care, you decide if, and how, to remember it. Classification and demarcation aren’t allowed to get in the way of the exchange. You just take it home and deal with it. If you choose to capture “YOU WILL LIVE FOREVER and picture-message it to your loved one, subtitled “LOL” or “WTF?” or “Awwwww,” then guess what? You’re the hero. You’re the honeybee. You’re pollinating. Ubiquitous, that’s what you are.

Jo Bannon, Foley

photo Carl Newland

Jo Bannon, Foley

“WHAT NEXT FOR THE BODY?” ASKS INBETWEEN TIME’S CENTRAL CURATORIAL QUESTION. TO WHICH JO BANNON ANSWERS: BONES SNAPPING, VIOLENT DROWNING AND GRISLY DEATH! (PLUS PARTY POPPERS. LOTS OF PARTY POPPERS.)

jo bannon: foley

Bannon’s Foley takes place at a table amplified by microphones and cluttered with vegetables, water bowls, metronomes and raw meat, a toolbox which the artist treats—and mistreats—to produce sound effects. Audience members are prompted to join in, providing footfalls, smatterings of applause and gunshots (hence the firecrackers). This is Bannon’s tribute to the pernickety and vaguely comic world of foley artists, where grown adults pretend to be foraging animals, a corkscrew doubles as a sonic screwdriver (true story, Doctor Who fans) and trudging through custard powder is the only thing that properly sounds like footsteps on snow.

No animals or snowdrifts here, though: Bannon’s audio landscape has an urban film noir vibe, which she narrates in deadpan received pronunciation. It’s a tale of mysterious dames and shady customers lurking in alleyways that recalls the mischievous tone of Godard’s Alphaville, generic elements peppering the storyline simply because they must; people get beaten up because, in a noir, that’s what happens. The femme is fatale because, well…what other kind is there? In Bannon’s world everything is, deliciously, at the service of the sounds. It’s also intriguing that for all of her flailing around—screaming into a bowlful of water, repeatedly slapping a slab of rump steak into the microphone—Bannon maintains a clinical detachment, a procedural poise. The artist appears to be asking us to conclude our own story, to fill in our own gaps, the sound alone is what she provides. These are the components she’s willing to give us…no more, no less.

Alex Bradley, Day For Night

photo Oliver Rudkin

Alex Bradley, Day For Night

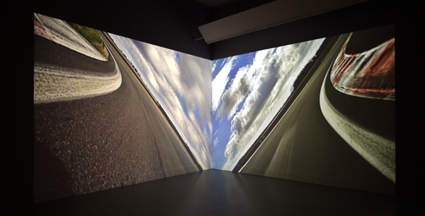

alex bradley: day for night

There are several other works at the festival distinguished by starving one or more senses so as to expand others: sparse experiences where the viewer’s own body is the catalyst, the storyteller, the conduit. In Day For Night by Alex Bradley you sit on a bench in a basement of the Colston Hall, faced with nothing but an opaque half-moon window. A surround-soundtrack of treated guitar noise (barely recognisable as such) comes and goes in long washes of frequencies both within and beyond hearing range. The sub-bass pulses occasionally send geiger counter crackles through the bench and vibrate your backside and spine in a disconcerting way. But the principle requirement is that you must watch, focusing patiently on the window as it shifts, almost imperceptibly, from bright daylight to night-time gloom—complete with projected streetlamps and car headlights peeping through the venetian blinds—and back again. It’s accumulative, a little urban tone poem that condenses the day and speaks of roadworks beyond the bedroom window, wasted hours and cold evenings hidden inside the house, spoilt for me only by the over-effusive explanations of the venue staff: “You sit here. It’s 17 minutes long. It’s a loop. You watch it go from day to night. It’s dark now but it’ll get light later. It’s about bunnies.” (Well, maybe not the last one, but you get my drift…)

Rod Maclachlan, Exchange

photo Carl Newland

Rod Maclachlan, Exchange

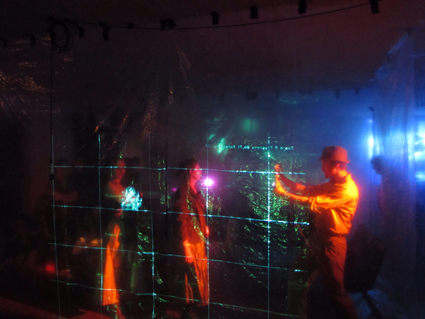

rod maclachlan: exchange

Exchange by Rod Maclachlan is similarly concerned with light and dark. A pair of participants is sent into a large space wearing flexible bands around their ribcages; the rise and fall of their breathing alters the light levels in the room. In this incarnation Exchange features an impressive rig of blazing hot lights (and the angry buzz of resistors is a powerful additional presence) but the full effect suffers by not quite responding with the symbiotic speed or precision you’d hope for. Even so it’s great fun, and the lights I’m linked to project directly out of the windows on Arnolfini’s upper level, adding a pleasingly extrovert edge to the experience, announcing your respiration across Bristol’s Harbourside.

Teresa Margolles, Aire

photo Carl Newland

Teresa Margolles, Aire

teresa margolles: aire

But for me the most affecting of all these engineered, ‘heightened’ spaces is Teresa Margolles’ Aire, a room that, on first sight, looks like an empty gallery where Arnolfini staff have accidentally left two oversized humidifiers hanging around. These devices are, in fact, circulating a very particular type of water vapour around the room—a clue to its provenance lies in the ominous legend printed next to a clear plastic curtain isolating Aire from the rest of the exhibition: “THE AIR IN THIS GALLERY IS SAFE TO BREATHE” which, as a friendly reassurance, ranks right up there with “YES! OUR RESTAURANT IS NO LONGER INFECTED.”

Margolles has, in fact, infused the room with water used to wash corpses prior to autopsy at a morgue in Mexico City. It’s been disinfected, of course…but that simple information, that implication of death, hangs in the air. Now, you can approach this with disgust or reverence, or any number of fleeting feelings, and I spend a lot of time in Aire shifting from emotion to emotion. There’s so much to do in this empty room. What do you feel? You can consider the sheer number of bodies that pass through a Mexico City morgue (largely thanks to drug laws that future generations will point and laugh at, much as we point and laugh at the Elizabethans’ attempted cures for the plague) and the stories that this vapour transmits, the curtailed lives it has touched.

You can picture those bodies, en masse, standing in the room with you, blank-eyed, naked, vaguely perturbed by being asked to participate in an artwork, pissed off at not being allowed to truly rest in peace. You can imagine that you smell the queasy cleanliness of a hospital (which is ridiculous, but smell it I surely do) and recall every time you’ve hung around waiting for a friend or loved one in some green-tinted ward. You can think of the journey that liquid has taken, the unlikeliest hop from a Y-section on a Mexican corpse to the cosy middle class milieu of a Bristolian arts centre. You can fight off superstitious revulsion at the molecules fizzing in your lungs, and where they’ve been. You can breathe in and out, deep and protracted breaths, communing uselessly with the dead, because they are dead and gone, and what good can you do for them now? You can look out of the window at the dark street beyond, perfunctory mechanical traffic on a frosty West Country night, feeling what a morgue worker feels when they emerge outside on a fag break; marvelling at the tiny differences between the living and the dead. For something so simple, Aire is a truly complex thing. It’s a quantum piece of work, gloriously indeterminate—in that depending upon how you look at it, it completely changes its behaviour.

THERE’S A BIT IN BARBARELLA WHERE A SPRAWL OF STONED WOMEN SURROUND A LIQUOR-FILLED GLASS GLOBE THAT HAS A YOUNG MAN SWIMMING AROUND INSIDE OF IT. HE LOOKS A LITTLE BIT HARASSED. THE WOMEN SUCK ON HOOKAHS ISSUING FROM THE GLOBE. “WHAT ARE YOU SMOKING?” BARBARELLA ASKS, INNOCENT AS EVER. “ESSENCE OF MAN,” COMES THE REPLY.

Zoran Todorovic, Warmth

photo Carl Newland

Zoran Todorovic, Warmth

zoran todorovic: warmth

I walked into the room and made a beeline for the rectangular piles of felt that looked like folded blankets. Heaped on pallets they extended upwards to just the right height for me to finger them, and to get my nose down in there. They smelt clean. Matted fibres, mostly bear-colour. Some lighter strands, some white.

I’ve noticed elsewhere that European hair-colour averages out to brown, even in Scandanavia. So the blankets default to a brindled dark mass. Mounted on the gallery wall, monochrome videos on fast-forward sum up the process of making at length. The hair is cut at the barber’s, mostly into a far-from-pretty no-frills back-and-sides. So seldom does the camera peer over the subjects’ shoulder to spy at a face in the mirror that when it happens, it comes as a shock. The backs of so many heads presenting! It’s like forming an impression of personality from the look of a person’s arse. Not that that can’t be done.

Blunt, defended scrubby heads. Utilitarian, no-nonsense settings. A couple of women are fleetingly glimpsed amongst those who do the barbering. For the rest it’s all men. In the video the shorn hair is gathered up, emptied on to tables and sorted by hand. Tissues and other detritus are picked out of it. The clumps of hair are teased and dried out in heaps on the floor and then shredded (a little) and carded in big industrial rollers, washed and felted in the steel machines. Blokes in heavy boots and overalls deployed in utilitarian structures of concrete and steel wield brooms and black bin liners under a fluorescent flicker. All the dander and the smell, the shed organic dirt that the hair must have collected is sifted out, washed off, got rid of. The blankets have been passed through an industrial process, they have been standardised and homogenised and, to a degree, purified, all obtrusively particular matter has been removed. Yet the gallery is somehow humming with essence of Bloke: hardy, gruff, obtuse, stoic.

There is no smell beyond the suggestion of a smidgeon of grease—I daresay human grease smells awful to other mammals but not to us. Just as well—I’m asthmatic, me, and have to be careful with fibres. These fibres are contained. Then I catch myself wondering what kind of garment one could make from this material, that one could bear to wear. A heavy skirt perhaps. I can picture being wrapped in this dense prickly insulating shield. For an hour or two perhaps it would not be insufferable. Perhaps.

I know that there is an ideology that determines the course of this work. I know there is a brooding, a nationalism and an exclusivity. But the de-naturing of this material, this organic remnant, renders it general. What remains is the implicit presence of hundreds and hundreds of men, their tangible residue rendered down and processed, ranked and arrayed, stacked on its pallet, ordered by the machine. The installation simulates a stack of commodities ready for some Spartan, barrack-like environment: a trading post, a quartermaster’s store.

The artist further makes use of the context of the gallery to hammer home his point about commodification: the blankets are for sale in the Arnolfini shop. Paradoxically the narrative and ideology of the work is pervaded by a seductive tenderness, the ‘warmth’ of the blankets, and by a sense of brotherhood, of community. The iconographic referencing of the major European trauma of the 20th Century, the Holocaust, I needed to have pointed out to me before I saw it, and it still jars.

Sarah Jane Norman, Take This, For It Is My Body

photo Carl Newland

Sarah Jane Norman, Take This, For It Is My Body

sarah jane norman: take this, for it is my body

“THIS WORK DEALS WITH THE GENERATIONS OF ‘HALF-BLOOD’ ABORIGINAL CHILDREN, INCLUDING THE ARTIST’S OWN MOTHER, WHO WERE AFFECTED BY THE GOVERNMENT’S REGIME OF ‘ASSIMILATION’.” INBETWEEN TIME FESTIVAL PROGRAM.

There’s a woman in an old satin slip welcoming me into the Dark Studio. It’s the sort of thing you wear when you’re slopping about the house getting on with something that’s needed to be done for a while. A garment that used to be glamorous and is now comfortable—that you feel self-indulgent in however shabby it gets. She has bare feet. There is a wonderful smell of bread baking.

Before I came in here I had to sign a disclaimer: “Please be advised that the ingredients include the blood of the artist. Please understand that you are not obliged to eat or accept this offering. If you choose to do so this will be entirely at your own risk.”

It’s like a dare, isn’t it?

She greets me. We are on either side of a long table. There’s a small industrial oven behind us in the corner. There’s another table parallel to this one, a couple of floury baking trays on it, three or so loaves proving under a cloth. To the side against the wall is a table set for one with fine linen, plain crockery, a pat of butter and a butter knife and a napkin-covered basket. There’s an area on the floor with towels, a jug and a bucket of water, and there are black bags of supplies against another wall. It’s like a cottage production line, some kind of back-country industry the farmer’s wife fits in with her other duties. Stylistically there’s something about the combination of the efficient and the genteel that reminds me of the 50s.

Sarah Jane Norman, Take This, For It Is My Body

photo Carl Newland

Sarah Jane Norman, Take This, For It Is My Body

There’s a large mixing bowl on the table, a sieve, small bowls of ingredients and a plate covered by another napkin, all different shades of white. The woman sieves the flour into the bowl and adds two dessert-spoons of sugar. In answer to my question she names the ingredients: “this is baking soda,” “this is buttermilk.” She lifts the napkin to reveal another dessert spoon. It contains blood, scarlet, with a darker line of clotting sunk to the bottom. So, the colours, glowing under the lights, are: white and cream ingredients, solid old-fashioned silverware, white crockery, white melamine tabletop, white linen, the woman creamy human in her creamy slip, one splash of red in the matt black surroundings of the Dark Studio.

Sarah Jane Norman pours the blood into the buttermilk and stirs. That turns it a dense pink, like Angel Delight. She pours this into the flour and mixes. The pink persists as the mixture starts clumping, darker material from the clot streaking through the dough. Amazing that such a small amount of blood has such a strong effect. She turns out the dough, kneading it, shaping it, slashing a cross into the top. She takes it to the next table to sit and prove with the other loaves (which show that definite tinge of pink as if they were special party bread). She goes to wash her hands in the bucket over by the towels.

The oven pings—the loaf that was put there before I entered the room is ready. Norman places it to cool by the proving loaves.

She invites me to sit at the place laid for one. Lifting the napkin from the basket she uncovers a rough, warm loaf, no longer pink. She cuts me a good slice, making eye contact all the time. It’s crusty, slightly bitter—that could be the baking soda—a bit heavy. I help myself to butter. If I’d tried to eat a whole slice we’d have been there for ages.

Succinct, earthy, confrontational, full of confidence, giving. Personal, not industrial, locating the political in the heart of family and domestic life, where it can do the most damage. About survival, not victimhood. Two very contrasting approaches to discourse about ethnicity and the threat of genocide.

Inbetween Time Festival of Live Art and Intrigue, Zoran Todorovic, Warmth, Arnolfini, Dec 1-Feb 6; Sarah Jane Norman, Take This, For It Is My Body, Arnolifini Dark Studio, Dec 4; Dec 1-5, Bristol UK

Our coverage of the 2010 Inbetween Time Festival is a joint venture between RealTime and Inbetween Time Productions

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 24, web

© Osunwunmi ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Hancok and Kelly Live, Iconographia

photo Oliver Rudkin

Hancok and Kelly Live, Iconographia

THE CIRCOMEDIA BUILDING USED TO BE A GEORGIAN CHURCH, NOW RE-PURPOSED FOR AN ARTFORM IN WHICH TRANSCENDENCE OF THE PHYSICALLY MUNDANE IS A DOMINANT THEME. THE CIRCUS SCHOOL HANGS THE TRAPEZE HIGH UP IN THE CEILING ARCHES, WHICH HAVE PLENTY OF ROOM BELOW THEM FOR THE SAFETY NET. ALONG WITH THE ARCHES THEY HAVE KEPT SOME OF THE PEWS, A GALLERY AND A FEATURE STAINED GLASS WINDOW. THE SPARE BATH STONE INTERIOR IS SOFTENED BY A SPRUNG WOODEN FLOOR IN THE MAIN PERFORMANCE AREA.

hancock & kelly live: iconographia

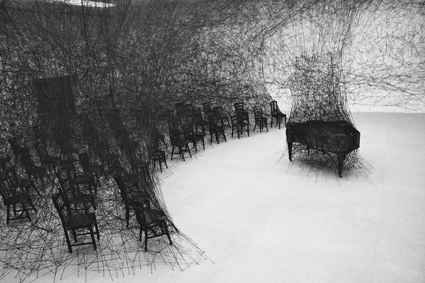

It was here that Richard Hancock lay on a plinth, at the height of a kitchen worktop, spooning a dead pig. The pig was already in rigor with his legs stretched out, a slight twist cocking his body askew. The man and the pig were the same colour.

Traci Kelly stalked round him purposefully. She was dressed in a black ball gown, a black pillbox hat with a small veil over her eyes, black gloves. Her tools were a block of gold leaf, a folded card to tweezer up each leaf, and a large soft brush, like a make-up brush, to fix and burnish. She would pick up a square of gold leaf delicately, angling it in the breeze of its own movement to minimise creasing and doubling, lay it on one of the bodies and smooth it down with the brush.

By the time I got there, one hour in, the feet and hindquarters of both bodies were covered, and Kelly was moving to the front of the hybrid to pay attention to hips and ribs. Music played: Dido’s Lament from Purcell’s Dido & Aeneas. Shreds of gold leaf escaped from the block, from under the brush, from the bodies, fluttering to the floor round the plinth or sticking to the black gloves and having to be scraped off. Where gold leaf sealed the gap between bodies it kept breaking down and having to be replaced. I kept wanting the process of gilding to be perfect. It stubbornly continued to be messy, very far from perfect.

Hancock held the pig tenderly, one hand resting on its chest between its front trotters. Its legs lay between his and he rested one knee insecurely on its narrow hip. It was a young pig, and thus about one third the man’s size. At all times the combination of genuine gold and glitter, of bourgeois formality (the hat, the gloves, the heels), of the representation of high culture, Purcell, to guarantee the seriousness of the occasion, threatened to topple over into vulgarity. Which is indeed the case at all our most solemn social rituals, weddings and funerals, where the popular, the profane and the high-minded collide.

The man was breathing, the pig was stiff. Both were sinewy and heavily greased with Vaseline. The gold around their nether regions caught the light in a more sparkly, less dense way than did their glowing naked orange-tan-pink skins. The pig had a bruise on its forward ham. The man did not. The man trembled with the cold, or the strain of holding the pose, or because all warmth was being leached out of him into the block of dead meat he cradled.

I had been told the pig still had the grass of its previous happy existence between its toes; I walked round to scrutinise. The long cut that had gutted it formed a tightly sewn, corded seam up the length of its body. Its tongue protruded between its teeth, curving up towards its snout. Smears of blood had been mostly wiped away, leaving only traces under the layer of Vaseline. It was clean. Its eyes were half open—it seemed to be looking up. Hancock lay with his own face directed towards it. He would meet its eyes if he opened his own. Then he did so: they were blue, the same colour as the pig’s. There the two were, in affinity.

At this point I surprised myself—for I don’t have that culturally specific Western sympathy for livestock—by feeling sorry for the pig. Then I felt the ways in which Hancock stood for the pig, and the pig for him, and both of them for all of us, tied to a hunk of dead meat and an inevitable end. The realisation was awful. I had to retreat. I went and sat up in the gallery where all that could reach me was the spectacle. I felt like howling.

Hancock and Kelly Live, Iconographia

photo Oliver Rudkin

Hancock and Kelly Live, Iconographia

Although I can recall it to memory it was not a repeatable moment, since it was triggered by physical presence. Occasionally I went down to stand in the same place and feel the same thing, drawn by the intensity of it—we don’t face such raw perception very often. Kelly inexorably and gently covered the intertwined bodies, stroking and burnishing as she obliterated them with splendour. Hancock breathed, and trembled under her touch. The music broke down and destabilised with every repetition, imperceptibly; yet by the end it seemed a distorted, reverberating howling played on a disintegrating instrument. The tension as Kelly moved the gold leaf closer and closer to the two faces was painful, yet when it happened, the end was not so dramatic. She smoothed the last gold square over the diamond-shaped fragment of face that remained of Hancock. Then she took care to remove pieces of golden film from within his nostrils. Pig and man now were covered, grafted together, shiny and perfectly inert. Kelly left the area.

More people had come into the church and become slowly rapt, standing closer to the plinth, drawn towards it, fascinated. The golden object, the glittering remnant, was to remain displayed for another half-hour. But I left, not caring to watch Richard Hancock shiver for that length of time. While Kelly was there, she was responsible for the work. But once she had left, audience complicity came into play to give us all control of the spectacle.

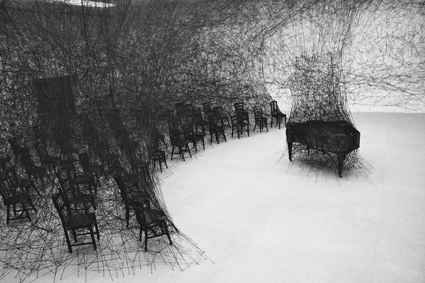

Teresa Margolles, 37 Cuerpos

photo Carl Newland

Teresa Margolles, 37 Cuerpos

teresa margolles: 37 cuerpos

It seems logical to me to compare Iconographia to Teresa Margolles’ work, not least because the spectacular aesthetic in which Iconographia wallows is so at odds with the minimalist aesthetic of Margolles.

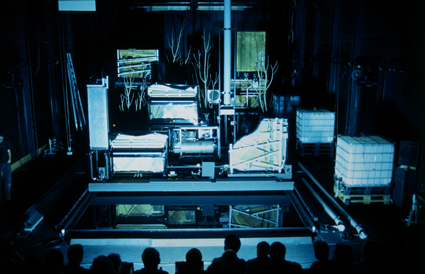

In 37 Cuerpos a gallery space is bisected by a thread running from wall to wall. It is a little below waist height. The room has four entrances/exits, a pair on each side of the cord, at right angles to it, and an adjacent pair in one of the walls to which the cord is fixed, opening into a corridor. The lighting is subdued and the gallery’s plainness underlines the clinical air of the installation.

Closer inspection of the thread reveals details. It is composed of many lengths of a waxy, cat gut-like material knotted together. The sections vary in the degree of blemish they have picked up: rust-coloured, grimy-looking stains. The knots are angular, giving the thing a look of organic barbed wire. The program notes explain each length was used to sew up a body after autopsy. A couple of lengths are heavily stained indeed: that person’s end must have been grisly.

Nobody who ventures into this room steps over the thread to get to the adjoining gallery, although it would be easy to do so. Instead they walk down the line to where the two doors open into the corridor; exit from one, take two paces and re-enter from the other. Then they walk up the line again.

Teresa Margolles, Aire

photo Carl Newland

Teresa Margolles, Aire

teresa margolles: aire

In Aire, Margolles’ work in the adjoining gallery, disinfected water collected from the washing of bodies humidifies a room. Those who walk there breathe it in and feel it cooling on their skin. I got to the entrance, hung with a heavy plastic strip door, where I caught a hint of pleasant coolness, as enticing for someone from the tropics as the smell of fresh bread baking. I noticed the industrial humidifier on the floor. I did not go in.

It is the spectators’ responsibility to pay attention, to leave themselves open to engage with the work. That may be all that is required, or they may be challenged by the artist to be complicit in what takes place; or they may be placed in a compromising position without their consent. However, in offering attention, the spectator also claims the freedom to refuse to take part. Once the artist asks for engagement they must also be ready for and accept refusal. Otherwise the quality of the encounter they have arranged is in question (what is real and what is not is always an issue in live work): their request is a sham, an underhand attempt to force a result using the contextual authority of the gallery.

Something more interesting is going on with Margolles, who uses not only the authority of the gallery but the entire machinery of prestige and commodification driving international high culture to draw attention to real lives and deaths in Mexico. As a conscientious spectator I could accept complicity, but I don’t: I am not part of that high culture machinery and I don’t think InBetween Time is either. Nothing could compromise me more in this situation than pretending to be so sophisticated that the idea of touching the paraphernalia of death doesn’t horrify me. A value system is being critiqued here, among other things: my naive reaction acknowledges horror at the base of it.

Inbetween Time Festival of Live Art and Intrigue, Hancock & Kelly Live, Iconographia, Circomedia, Dec 5; Teresa Margolles, 37 Cuerpos and Aire, Arnolfini, Dec 1-Feb 6; Dec 1-5, Bristol UK

Our coverage of the 2010 Inbetween Time Festival is a joint venture between RealTime and Inbetween Time Productions

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 24, web

© Osunwunmi ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Pete Barrett, The Surety, The Surety (The Inner Surety)

photo Oliver Rudkin

Pete Barrett, The Surety, The Surety (The Inner Surety)

“THE REASON OF THE UNREASON WITH WHICH MY REASON IS AFFLICTED SO WEAKENS MY REASON THAT WITH REASON I MURMUR AT YOUR BEAUTY.” CERVANTES, DON QUIXOTE

I’ve often thought of Live Art as having properly Quixotic aspects to it: foolhardy, sometimes nonsensical quests, undertaken in the face of scorn; easily mocked; often more moving and possessed of less selfish egotism, than might first appear. In Arnolfini’s foyer, an impeccably attired Pete Barrett decorates a wooden chair with tiny florets of cake icing, a beautiful, sedate action with strange, wordless inner logic. Many onlookers scowl with incredulity, some shrug…but it’s the kids who understand him best. They toddle up close to stand quiet and respectful at Barrett’s shoulder, as he lays concentric triangles of sugary paste across the dark wood.

Cupola Bobber, Wave Machine #2

photo Oliver Rudkin

Cupola Bobber, Wave Machine #2

For Wave Machine #2, US duo Cupola Bobber spend the cold afternoon in the shadow of Bristol Cathedral, attempting to replicate the swell of an ocean wave using pulleys and white/blue tarpaulins, repeatedly, back and forth, no-nonsense—because that’s what they do. For Black Box Ni, Paul Granjon has built an independently functioning robot that is able to control its maker via an interactive costume, compelling the artist to perform random repetitive tasks and—in one hilarious sequence—firing high-velocity paintballs at Granjon whilst he tries to construct a jam sandwich.

Kim Noble

kim noble: kim noble will die

But there’s a darker side to Quixotic desire that even some of Inbetween Time’s audience might have problems with. Because generally, we prefer the safer madness, don’t we? The zany madness, the village idiot madness. Madness with boundaries and recognised borders. One 2009 review of Kim Noble Will Die protested, “Even for a show about going too far, he goes too far,” and that’s because Noble’s masterpiece is an uncomplacent, confrontational, no holds barred, side-splittingly funny and unbearably upsetting portrait of a mental condition, the bipolar monster that has been cruelly toying with him, on and off, for much of his life.

Noble has censored so little of himself (and been equally indiscriminate with the lives of his family, ex-girlfriends, and neighbours) that you leave the show feeling beaten up, elated, angry and honoured, all at once. You wonder what percentage of it was ‘true,’ and then you question how much (if at all) that knowledge would matter. Because even if Noble is fucking with our minds (he didn’t really ejaculate into that bottle of Vagisil and leave it on the supermarket shelf, did he?) the image would hold fast, the portrait of the artist would remain the same. Even if this were embellished rather than pure autobiography, the journey would feature the same remarkable peaks and troughs, in relating Noble’s struggle to find meaning in a world that, to him, looks increasingly barren.

The show is a high speed stream-of-consciousness audiovisual presentation cramming 10 hours of material into 60 minutes. Karaoke rock is sung to repeated close-ups of Noble’s ejaculating penis. Horrendously intimate phone calls bleed from the speakers. Members of the audience are banished from the room at random. Some poor ticket-holder sits with a bucket on his head for the full hour. There’s a genuine cameo by a world-famous Hollywood star. There’s product tampering, unhinged email exchanges, cash handouts and graphic, profoundly disturbing self-harm. It mugs you. Past audiences have actually reported this show to the police. It is, no doubt whatsoever, exploitative of artist, audience and innocents alike (but in its awful honesty, what else could it be?) and—it must be noted—it is very, very male.

This last factor seems to feature heavily in people’s responses to Noble’s work. Audiences keen on Live Art’s capacity to navigate uncharted territory sometimes baulk at being asked to care about problems of white middle class blokes with Macbooks. Maleness is often seen as conservative, the predominant power structure, the mainstream; as a result a full exploration of masculine motifs and issues is a relatively rare thing to see on this circuit, and to witness Noble taking it to extremes (sometimes horrible, misogynistic extremes) will go not only beyond empathy for some, beyond risk, but also beyond acceptability. I wasn’t sure what to think. I’m still, after several days, not sure. All I know is that, on and off, I’ll be thinking about this show until my tiny light sputters.

Kim Noble, You Are Not Alone

photo Oliver Rudkin

Kim Noble, You Are Not Alone

kim noble: you are not alone

In Kim Noble Will Die the artist is a pot-bellied silverback gorilla of a man, a dominant presence pacing back and forth who, you suspect, it’s best not to look in the eye for fear of reprisal. He’s grim and glowering, not smiling once. He’s similarly unsmiling throughout You Are Not Alone, his second show of the festival, until a fleeting moment late in proceedings. During a film of him presenting a ‘Kim Noble Award’ to his favourite takeaway restaurant, while shaking the bemused owner’s hand, a genuine sliver of a smile creeps onto his face. And it’s heartbreaking, a release—especially if you’ve sat through both shows. It feels like a tiny reward.

Kim Noble Will Die is riven with humiliation, failure and madness. You Are Not Alone is at the other Quixotic extreme, with its comic levels of altruism, its cranky hope, its unstoppable quest. The ‘ghost’ of Noble’s ex-girlfriend haunts the stage, a printed photograph on A4 paper projected via a glitchy webcam rigged to Noble’s head. The story begins as she departs in a taxi, their relationship ended at that very moment, and Noble decides to make sense of events by making his loneliness a weapon of empathy. Neighbours on the London street where he lives form a venn diagram of opportunities, and addressing their problems without complaint—often covertly and without reward—becomes a way of making the world better.

As you’d expect, this Knight Of The Woeful Countenance has particularly idiosyncratic solutions for stolen plant pots or a takeaway restaurant’s lack of business, his neighbour’s depleted sex life or the isolation of modern urban existence. He offers to deliver onion bhajis to anywhere in the UK, if only we’ll order them (phone numbers are provided). He ropes his audience into making appreciative phone calls about taxi journeys that never happened. He randomly twins his street with one in Eastern Europe (and journeys there to announce it, to friendly bemusement). One night he cleans every car parked on the road, dressed as a cartoon bear.

It’s still shot through with the usual Kim Noble queasiness—especially as determining his neighbour’s ‘problems’ requires him to engage in almost obsessive electronic surveillance. But he’s a different character tonight: barely speaking, letting a computerised voice narrate the quest, a man at the service of something beyond himself. Taken together the ultimate effect of these two amazing shows is, for me, the same as in Cervantes. You desperately hope that Kim Noble will one day conquer his afflictions. But at the same time the ludicrous, surreal beauty of his battle both repels and enchants you.

Inbetween Time Festival of Live Art and Intrigue, Pete Barrett, The Surety, The Surety (The Inner Surety), Arnolfini, Dec 5; Cupola Bobber, Wave Machine #2, various locations, Dec 2-5; Paul Granjon, Black Box Ni, Wickham Theatre, Dec 5; Kim Noble, Kim Noble Will Die, Arnolfini, Dec 4; Kim Noble, You Are Not Alone, Circomedia, Dec 5; Bristol, UK, Dec 1-5

Our coverage of the 2010 Inbetween Time Festival is a joint venture between RealTime and Inbetween Time Productions

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 23, web

© Timothy X Atack; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jones and Llyr, A Mouthful of Feathers

photo Carl Newland

Jones and Llyr, A Mouthful of Feathers

AMONG THE THRONG OF WINE-GLASS CLUTCHING AFICIONADOS AT INBETWEEN TIME’S LAUNCH PARTY, TWO SLIGHT YOUNG MEN SIT OPPOSITE EACH OTHER AT A TABLE, DRESSED AS PLAYTIME RED INDIANS: WHITE VESTS, SHORTS, AND CROWNS OF PRIMARY COLOURED FEATHERS. A GLASS JAR OF PEANUT M&MS (COLOURS CORRESPONDING WITH THEIR FEATHERS) SITS BETWEEN JONES AND LLYR, AND IN TURNS THEY SUCK, CHEW AND SPIT OUT THE SWEETS, FACING EACH OTHER DIRECTLY, THEIR GAZE SOMETIMES A CHALLENGE, SOMETIMES AN INVITATION, BUT ALWAYS A JOINT ENTERPRISE.

They drool residue onto the white table, making a gloopy multi-coloured patina. Occasionally they attempt to spit confectionery from one mouth to another; failed launches are met with wry smiles. This silent flirting with revulsions and bodily etiquette is youthful and funny—but at the same time suggests a strange entropy, dissipation and doubt. As the evening grows older, discarded chocolates scatter across the Arnolfini floor, as if the performance has a radiation, a half-life, particles falling away like petals from a flower.

The push-me-pull-you of partnerships is explored by several other performing duos at Inbetween Time, in forms that vary from fragile, stately propositions to noisy creative-destructive acts to sheer animal glee.

search party: somehow growing old with you

The fragile and stately first: Search Party are real-life couple Jodie Hawkes and Pete Phillips who we learn met in their 20s. Their show is a love letter to each other, but…wait, no, come back! Somehow Growing Old With You manages to circumnavigate the cloying neediness of a bad wedding ode. It doesn’t feel like a renewal of vows, though that’s essentially what it is: a ceremony, a statement of intent, occasionally demanding the patience you’d give such a thing. But its glacial pace and quiet repetition proves meditative, its moments of emotional beauty dotted about an arid landscape of salt and smoke.

Phillips and Hawkes slow-dance across a carpet of salt that crunches beneath their feet like glass. They walk forward, Hawkes having some sort of unspoken problem with reaching a certain distance, Phillips carrying her to the threshold in a variety of ways, each time failing to convince her to stay. They hold private conversations in inaudible whispers, discussing what to do next, checking their progress with each other in gazes, glances, frowns and smiles. Eventually, they each record a message to camcorder for the future, telling the story of how they met, of how their daughter was born. This is the start of a process wherein Search Party will record such messages every 10 years, for as long as they’re together, or until they’re no longer able to. The inevitability of human decay hangs heavy in the room, announced and committed to tape…but Search Party are carrying that knowledge, that destiny, together. I once heard the artist Franko B wonder at how audiences rarely have a problem with the sharing of pain, but no sooner does an artwork express overt sentimentality than its integrity is doubted. True love is sometimes a dirty secret in live art. This show, unashamedly, reeks of it.

Action Hero, Frontman

photo Carl Newland

Action Hero, Frontman

action hero: frontman

Smoke is also filling the room at Circomedia, but this time it’s rock gig smoke, drifting over a raised stage and guitar amplifiers, shot through by spotlights. Action Hero are premiering Frontman, their lament for the egos of petulant musicians throughout the ages. Previously Gemma Paintin and James Stenhouse have appropriated and assimilated texts from westerns and daredevil spectaculars with a style that sees them rope the audience into the proceedings—shooting down the hero in a hail of imaginary bullets, cheering the motorcycle jump or going silent when the stranger walks into the room. Tonight is slightly different; no less urgent, but another kind of energy, because it centres upon what happens when the contract between audience and performer falters or fails. Paintin holds court in spangled hot pants, making her way through various on-stage crises: hubristic, chaotic, physically destructive, confrontational. It’s a catalogue of ineloquence made either comic or distressing by its amplification. Then, when she finally gives up the ghost and crumples, hands over her ears, the soundtrack takes over, eliminating her, a wall of intense electronic scree with frequencies so violent we reach for the earplugs we’ve been handed before the show begins.

Stenhouse is also on stage throughout, a gangly roadie in rabbit ears, operating technical equipment, untangling cables in a hilariously slow and straight-faced manner. He’s heckled by Paintin and they physically fight on stage. She hides in the shadows and accuses him of ruining everything. It’s exhausting, and you feel for the performers, Paintin especially. Action Hero themselves are a company in the spotlight, their shows the subject of great acclaim. You wonder how much this show is actually about the artists, about their mercurial creative processes, their negotiations, cul-de-sacs and unpredictable life force.

Pieter Ampe and Guilherme Garrido/CAMPO

photo Oliver Rudkin

Pieter Ampe and Guilherme Garrido/CAMPO

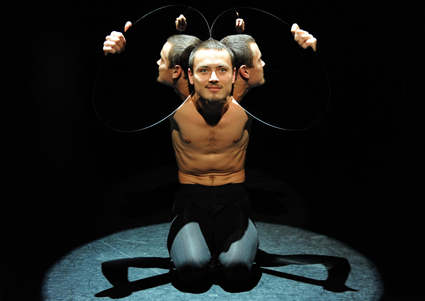

pieter ampe and guilherme garrido/campo: still standing you

And speaking of untameable life forces: the audience for Still Standing You is assembling. It’s 11am. Guilherme Garrido is on stage, precariously seated on an impromptu stool made of his colleague Pieter Ampe’s legs. Ampe’s back is flat on the ground. He seems stoic about the situation. “We’re just waiting for a few more people to come in,” says Garrido, “Then we can begin this breakfast buffet of contemporary European dance.” And my god, I haven’t been this excited by a dance work in years.

I’d love to be able to describe Ampe and Garrido’s performance in intricate technical detail but I’m afraid I watched much of it through gasps, stifled giggles and tears of happy laughter. There’s no music, no set, nothing on the well-lit stage bar our odd couple: Garrido a swarthy Portuguese chatterer; Ampe a wiry, wordless, ginger-haired mega-bearded Belgian. The show is about them working out what they ‘mean’ to each other, and what this means for us is an extraordinary celebration of all the stupid, joyful, hilarious, loud and unlikely things that two human bodies can do to, at, for and with each other in one hour. Ampe and Garrido hurl one another around wrestler-style, make human climbing frames of themselves, play dangerous games of physical one-upmanship, snarling throughout in ridiculous thrash metal vocalisations, gurning, spitting and croaking. Then they finally rip each other’s clothes off, flapping nude about the stage like distressed fish, yanking at each other’s penises as if they were plasticine and locking around and upon one another to make half-men forms, strange animals with human skin, a being made entirely of legs, Siamese dancers, noisy molluscs.

Easily my favourite experience at Inbetween Time, it’s almost easier to describe what Still Standing You wasn’t than what it was. For a show with explicit nudity it wasn’t remotely sexual—despite, for instance, a moment where Ampe opened up Garrido’s foreskin and screamed into it from the top of his lungs. Yep. Read that again. That’s right. It didn’t feel like a masculine initiation rite, because it was so personal to the two individuals before us, rather than existing in a specific cultural place and time. And it wasn’t random and unfocused, because the dance proceeded from one crazy move to the next with a logic that carried the audience with it, making us laugh or wince in anticipation. What it was, at heart, is best expressed by paraphrasing the late great Pina Bausch: not interested in how these two people move, but in what makes them move.

Inbetween Time Festival of Live Art and Intrigue: Jones and Llyr, A Mouthful Of Feathers, Arnolfini, Dec 1; Search Party, Growing Old With You, Wickham Theatre, Dec 2; Action Hero, Frontman, Circomedia, Dec 4; Pieter Ampe and Guilherme Garrido/CAMPO, Still Standing You, Arnolfini, Dec 2; Bristol UK, Dec 1-5

Our coverage of the 2010 Inbetween Time Festival is a joint venture between RealTime and Inbetween Time Productions

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 22, web

© Timothy X Atack; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

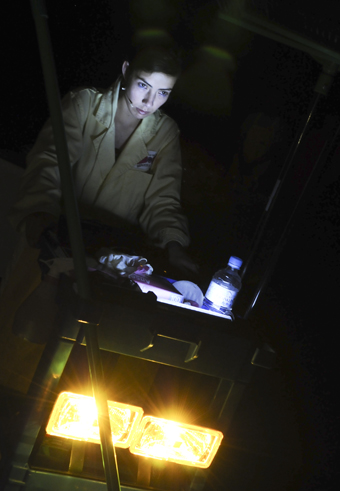

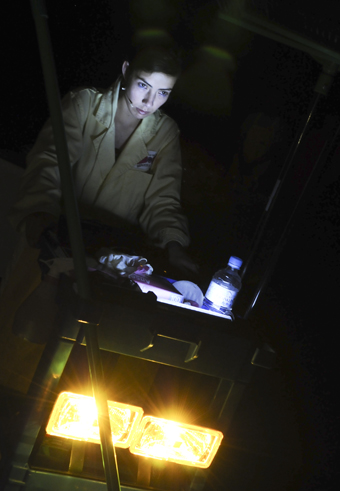

Helen Cole

photo Jamie Woodley

Helen Cole

“A FESTIVAL IS AS PRECARIOUS AS ANY ARTWORK,” HELEN COLE, PRODUCER AND CURATOR OF THE UK’S BIENNIAL INBETWEEN TIME FESTIVAL OF LIVE ART AND INTRIGUE IS TELLING ME. “YOU NEVER KNOW WHAT IS GOING TO HAPPEN TILL YOU ADD THE AUDIENCE. YOU’VE WORKED HARD TO CREATE THE OVERALL SHAPE AND THE JOURNEY THROUGH THE WORKS, BUT YOU HAVE TO BE MET HALF-WAY BY YOUR AUDIENCE, YOUR CO-WORKERS, THE ARTISTS IN YOUR COMMUNITY.”

Cole’s concern for chemistry characterises Inbetween Time (IBT), a festival where the parties and pauses for conversation and exchange are as carefully configured as the performances. I attended the festival in its early days and was captivated by the sense of community generated by Cole around an esoteric and little known new festival in the small city of Bristol. Artists I had never heard of were mingling cheerfully with their better-known peers and international presenters in the Arnolfini gallery’s cosy bar. The work was carefully contextualised to accommodate emerging and established practice and make the five-day event feel like a singular, intense immersion into a range of practices anchored in the body.

Since 2001, the festival has grown in scale and profile and several of those emerging artists have similarly acquired international repute. Cole acknowledges that the 2010 festival is her most ambitious to date, with new venues added to the central Arnolfini gallery and performance spaces as well as an extensive sited program in public spaces. Now independently produced, IBT is a partnership with Arnolfini, where Cole was the Producer of Live Art and Dance for 12 years. With the majority of its funding for three years coming from the Paul Hamlyn Foundation, IBT is in a relatively robust position amidst the devastation wrought by diminished arts funding in the UK.

“It was hard to celebrate this year,” says Cole, “knowing about the challenges facing the arts sector. Not to mention the snow!” Images from the festival, of which there are many on the websites documenting IBT, show panels of rugged-up presenters, artists and audiences engaged in joyful defiance of the weather. “There was a true spirit of the Blitz,” says Cole, “we were all in it together. The usual eccentric moments were magnified.”

highlights & new parameters

Cole cites several highlights in the 75 productions in her program, speaking with great enthusiasm of Frontman by Action Hero, the local group who have been garnering significant attention nationally and were facing that difficult hurdle of recreating the impact of their breakthrough work. In a new partnership with Circomedia, the Bristol based circus development organisation, IBT programmed Action Hero’s new work in a large church, creating an incongruous gig-like feel with dry ice and pumping sound. Cole rates the success of this satisfying production as highly as she does the extremely uncomfortable two works presented by British comedian, Kim Noble. “Kim pushed all the edges,” says Cole, “crossing from the intensely private into the public and making everyone cringe.” There was another cringing highlight for Cole in the Belgian production, Still Standing You by Pieter Ampe and Guilherme Garrido from CAMPO. Presented as part of the Lecturama mid-morning program, this confrontingly visceral grappling dance between two big blokes had everyone wincing over their coffees.

The CAMPO production is testimony to the longevity of the relationships Cole holds with peer producers in Europe. Kristof Blom, CAMPO’s producer, joined Nayse Lopes of Panorama Festival in Rio de Janeiro and Fiona Winning from Australia on an International Curators’ Panel about the modus operandi he shares with Cole: his recommendation gave her the confidence to program Still Standing You from video alone.

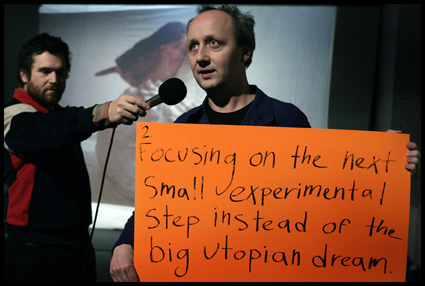

This unlikely dance work demonstrates that IBT is about more than live art. The festival’s brochure explicitly states that its D:Stable strand comprises “new artist commissions, premières and international co-productions that thoroughly reject theatre convention.” New experimental works by such celebrated names as Blast Theory, Ivana Muller, Quarantine and Tim Etchells stand alongside home grown premieres from Timothy X Atack and Tanuja Amarasuriya, Alex Bradley or Cole’s own production, Collecting Fireworks.

There is a through line of exploration that unites the broad diversity of the program and creates that sense of communal adventure that resonates throughout the experience of attending IBT. Cole says, “I am curating conceptually and choosing work that makes sense in a program. I want audiences to consider not just these works, but a body of work and a conversation with an artist that is as much about where they are as where they are going next.”

Sarah Jane Norman, Take This, For It Is My Body

photo Carl Newland

Sarah Jane Norman, Take This, For It Is My Body

the australian connection

Three Australian works in IBT10 reflected Cole’s lengthy engagement with Australian contemporary performance. She first visited Performance Space in Sydney in 2000, striking up a relationship with then director Fiona Winning that resulted in a number of Australian artists appearing at IBT 2006. In 2010 Winning herself and Victoria Hunt appeared in Dancing the Dead in the program strand connected to the Arnolfini exhibition, What Next for the Body.

“This work surprised me with how well it was received,“ says Cole, “given how little we know of that culture [Hunt’s Maori heritage is explored in conversation and dance]. Fiona and Victoria found a way of talking about the making of new work in front of people who do not know either of them, or the themes of the work, and held it all together. This sort of exploratory conversation really works in IBT.”

Another Performance Space connection led to the programming of Take This, For It Is My Body by Sarah Jane Norman, also in Arnolfini. “This one-on-one work was very simple,” says Cole. “I am not sure how much the audience could access the references to Australian Aboriginal culture, but they clearly understood the conceptual significance of Sarah Jane’s mixing of her blood into the bread and were challenged by her offer to consume it.” Cole saw Norman at Sydney’s PACT around 2004 and followed her trajectory through the creation of her independent work in Australia and then internationally. “We have been in conversation for several years,” she says.

Back to Back, The Democratic Set

A more recent conversation, and one that seems at first glance to be less likely, is Cole’s commission for Geelong-based Back to Back Theatre. “Despite our very different aesthetic tastes, we share the same commitment to building community around our work,” Cole says. “I learned an awful lot from having them make The Democratic Set with us over 10 days in Bristol. It is very politically current to work with diverse communities and make participatory work, but this is something different. They have such a light touch and such clear curatorial thinking. The relationships they built so quickly with our community were staggering. They worked with over 100 people without blinking. The project is so simple, so elegant and so heart-warming. There was a frenzy of about 400 people trying to get into the gala premiere screening. I am sure this is just the beginning for us. Back to Back have a community in Bristol now; people who have given something of themselves to the company and have started a relationship with them. Bruce [Gladwin, Back to Back’s director], an artist from the other side of the world, spoke at our opening event and it just felt right. Sometimes you find yourself on the other side of the world and you are at home.”

The number and diversity of artists who find themselves at home in Bristol is increasing year by year as Cole continues to pitch her close knit community of local artists further and deeper into the international context.

Inbetween Time Festival of Live Art & Intrigue, Bristol, UK, Dec 1-5, www.inbetweentime.co.uk

Our coverage of the 2010 Inbetween Time Festival is a joint venture between RealTime and Inbetween Time Productions

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 21, web

© Sophie Travers; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

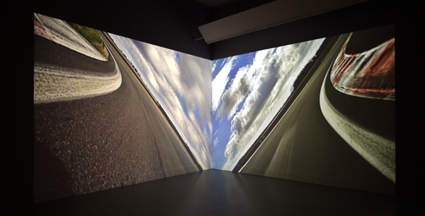

Temporary Distortion, Americana Kamikaze

photo courtesy the artists and Brisbane Powerhouse

Temporary Distortion, Americana Kamikaze

THE DISCRETE CHARM OF ANDREW ROSS, DIRECTOR OF THE BRISBANE POWERHOUSE, LIES IN HIS WARM DEMEANOUR COUPLED WITH AN INNATE SENSE OF PUNCTILIO; HE IS NOT GIVEN TO HYPERBOLE. NEVERTHELESS, HIS BLUE EYES TAKE ON A FIERCE QUALITY WHEN HE ENUNCIATES UNFASHIONABLE IDEAS LIKE “PASSION,” “INSPIRATION,” “COURAGE” AND “TRUE GRIT” AS HIS CRITERIA FOR CHOOSING WORKS FOR THE EXPANDED WORLD THEATRE FESTIVAL (WTF) AT THE BRISBANE POWERHOUSE IN 2011—ITS CHEEKY BYLINE IS: “WTF ARE YOU DOING IN FEBRUARY?”

These are all works that, in Ross’s view, were not formulated to subscribe to market-driven values, but spoke in the first place to the concerns of their audiences in different contexts, works that if they are ‘real’ or ‘any good,’ speak to an audience anywhere. Ross resists the notion that such works necessarily reflect contemporary performance practice, believing this terminology to be misleading and exclusory, preferring the more pluralistic term “current practices” to apply to multiple works that have been independently produced and have, so to speak, their own faces, “investing in different priorities to commercial theatre.”

Ross built his reputation in Perth as a promulgator, devisor and director of new works. These included Jack Davis’ The Dreamers followed by No Sugar and Jimmy Chi’s Bran Nue Dae. He went on to found Black Swan Theatre Company which gained a formidable reputation nationally and internationally for new work, and launched the careers of many Indigenous performers such as Ernie Dingo and Leah Purcell and writers Jack Davis, Jimmy Chi and Sally Morgan. Ross specifically attributes his work with Indigenous theatre as helping to sharpen his eye for performances that interact with an audience hungry, desperate for the experience, just as he had been as a young man at the Pram Factory in Melbourne. It also alerted him, as did his travels in India and Indonesia, to the roots of theatre emanating from the ritual, even religious nature of a festival.

Ross’s concern for socially transformative experiences in the theatre causes him likewise to reinvent the ritual of theatre that goes well beyond the physical act of attending a performance by creating an exciting environment that “destabilises the formalised presentation of culture, creating a space to hang out…stimulating conversation, opinion, engagement, connection and personal interaction between artists and audiences” (Press Release). WTF has the boldly stated aim of reviving within three years the “ritual of gathering for live performance for collective contemplation and conversation about life…a distinctly social act.”

Ross points out that Brisbane has the lowest national theatre attendance per capita. By changing the way theatre and performance is delivered, WTF challenges prevailing perceptions of live performance. It aspires, in Ross’s words, “to bring audiences, local artists and leading national and international artists to Brisbane to form a critical mass for performance culture.” WTF’s accessibility has been assured in a commitment to affordability with the provision of cheap food stalls and a low cost ticketing strategy and initiatives to subsidise industry workers from interstate.

The pilot scheme earlier this year in the first WTF genuinely lived up to expectations. Audiences revelled in it, and it completely won me. The marvel was that the most interesting work came from Queensland, and was commissioned by the Brisbane Powerhouse: Brian Lucas’s amazing one-man show, Performance Anxiety (RT96, p30). It more than stood on its own alongside forceful products from overseas. In 2011 the solo work similarly being premiered under the auspices of WTF by Melbourne-based Real TV is the gritty, poeticised drama, Random, written by UK playwright Debbie Tucker Green and performed by Zahra Newman who both share a Jamaican heritage. Its theme—the death of a young black man and its effects on family—is, sadly, all too relevant in Australia. Otherwise the program divides even-handedly between mainstage productions and Scratchworks, new Australian works in development.

The international section of the program has been scheduled mainly from Europe and America (in subsequent years works will be chosen from the demographics Africa/Asia and Eastern Europe/South America). From the UK comes Super Night Shot by Gob Squad (see p4). Filming commences one hour before the audience arrives with four video cameras wielded by four performers who have set out on a semi-scripted, semi-improvised scenario of adventures and encounters in the vicinity of the Powerhouse. The performers return, meet their audience and the tapes are played back unedited on a four-way split screen, imploding the parameters of live performance. Kassys from the Netherlands brings Good Cop Bad Cop to the program using this company’s signature juxtaposition of film and theatre to build upon texts and editing techniques from reality television. I saw their production of Kommer (Sadness) at the Powerhouse in 2008, and regard it (along with Performance Anxiety) as one of the most memorable shows of the decade. It’s difficult to describe how their quirky brand of physical comedy conveys worlds of feeling and absolutely nails the absurdity of everyday lives. Also bridging the gap between cinema, performance and visual art, from the USA comes Americana Kamikaze in an Australian exclusive, an uptake on Japanese ghost stories by Temporary Distortion (New York/Japan). This promises to be the most visually rich, trance-inducing and disturbing contribution to WTF where actors perform minimally in boxes in front of a large screen to add another layer (in a dual sense) of projection. As Matthew Clayfield wrote from New York, “While some of the horror elements of the production were indeed quite frightening, it was as much [a] Möbius strip-like quality, the sense of having the formal and generic rugs pulled out from under you, that made the production most unsettling” (RT95).

The Waiting Room, Born in a Taxi

photo courtesy the artists and Brisbane Powerhouse

The Waiting Room, Born in a Taxi

From New Zealand, Hackman’s Apollo 13: Mission Control takes over half the Powerhouse Theatre in yet another extension of the theatre experience as we join flight director Gene Kranz and become responsible for helping guide the famous space shuttle home. It’s been lauded by critics and loved by audiences for its innovation and imaginative design. Well-received at both Edinburgh and Dublin Festivals, Diciembre is an intense, highly charged and passionate piece from Chile’s Teatro en el Blanco in which personal and autobiographical events impinge on the drama, including experiences of racism, protectionism and patriotism. Sydney-based performance-maker, writer, teacher and curator Rosie Dennis was last seen at the Powerhouse with her production Fraudulent Behaviour earlier this year. Her current work, Downtown, an exploration of belonging and connection, will be created day by day in Brisbane across the festival for a final day/night showing featuring Brisbane’s Gay and Lesbian Choir. Finally there is the mainstage appearance of the winner of the Melbourne Fringe Festival Brisbane Powerhouse 2010 Performance Award, The Waiting Room by Melbourne’s Born in a Taxi & The Public Floor Project. This highly physical, non-verbal work involves a live, real-time sound score which makes each performance an unrepeatable event.

There are seven brand new Australian shows in the making in the 2011 Scratch Series. WTF finds spaces for artists to take wild flights in front of an audience, and an informal atmosphere in which to discuss and absorb feedback from the audience. Personally, I find this arena for nascent works fascinating, often discovering that the process of polishing loses much as the rough beast is tamed. Gorgeous national and international performers like Christine Johnston and Lisa O’Neill are on hand, creating musical/performance vignettes with Peter Nelson in order to develop their RRAMP band sound and aesthetic; well known Polytoxic scrambles a new, high flying work; Daniel Santangeli’s Room 328 will drive you to drink (no, I loved their commitment and dark carnivalesque in its first incarnation, and look forward to seeing it again; see review); Black Queen Black King by Steven Oliver explores the lives of four Indigenous gay men culminating in a celebration of strength, pride, sexual and cultural identity; and Elephant Gun by The Escapists looks like being an intriguing site-specific work for a small audience.

These six specifically Queensland works are complemented by the Drawing Project (Open Studio), a multi-arts project by Fleur Elise Noble from Adelaide and featuring Erica Field as the performer. There is also a Masterclass and Forum Series running throughout the festival. The keynote speaker is Jude Kelly (Southbank, UK), her talk centres on community engagement with creative spaces and how cities are identifiable in the art they’re producing. This series is open to tertiary students, local artists and industry. What to do in February? Come to WTF!

World Theatre Festival 2011; Brisbane Powerhouse, Feb 9-20, 2011; brisbanepowerhouse.org

RealTime issue #100 Dec-Jan 2010 pg. 29

© Douglas Leonard; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Paul White, In Glass

photo Ian Bird, courtesy Sydney Opera House

Paul White, In Glass

IN ITS SECOND YEAR, THE SPRING DANCE PROGRAM AT THE SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE HAS BEEN A FEAST FOLLOWING THE CITY’S 2010 CONTEMPORARY DANCE FAMINE. AN ALMOST OVERWHELMING FOUR-WEEK PROGRAM PRESENTED DANCE FILM, LIVE PERFORMANCES AND AN ONLINE CHOREOGRAPHIC COMPETITION. TWO OF THE AUSTRALIAN PREMIERES WERE BY ESTABLISHED DANCE ARTISTS NARELLE BENJAMIN AND GIDEON OBARZANEK.

in glass

Narelle Benjamin’s creamily athletic choreography folds, flicks, rolls, curves and dips in an admixture of textured rhythms and flowing ‘through-ness.’ The body of the choreographer is deeply inscribed everywhere on the bodies of its two magnificent dancers, Kristina Chan and Paul White—in the deep, deep flexion of the joints, in the rolling through and across positions, in the display of extreme flexibility and balanced strength born of yogic alignment, in the often triangulated and turned out legs and in the choreographic obsession with folding and opening. While Chan and White dance with their avatars created by five onstage mirrors, the dominant avatar is the absent/present choreographer whose powerful embodiment determines and inhabits In Glass.