January 2011

Brendan Cowell and Charlie Fraser, Bee Sting

we like short shorts

It may be the season for wearing shorts, but it’s also the season for watching them. More specifically, it’s time for the International Short Film Festival Flickerfest, which has just finished screening in Bondi and is now set to tour the country. This year Flickerfest will travel to more than 30 locations, including regional centres such as Alice Springs, Katherine, Noosa, Narrabri, Cygnet and Wyalkatchem. The program varies from venue to venue, so while some will focus on the Best of International Shorts, others will feature Flicker Kids and the Best of Comedy. However, most venues will be screening the Best of Australian Shorts program, which includes the animation The Lost Thing (winner of the AFI Award for Best Short Animation 2010), directed by Andrew Ruheman and Shaun Tan, as well as Bee Sting (starring Brendan Cowell and Matilda Brown) and The Telegram Man (starring Jack Thompson as “the man who must deliver the worst kind of news during the long years of World War II”). For more information see the Flickerfest website. Flickerfest Tour, various venues, Jan 21-March 27; www.flickerfest.com.au

movement at the station

Sydney’s CarriageWorks has just announced Lisa Havilah as its new CEO, commencing February 2011. Havilah is currently the Director of Campbelltown Arts Centre, where she has pioneered a program of inclusive and experimental contemporary art, much of which has been reviewed in RealTime. To get a sense of her breadth of vision see our reviews of Chiara Guidi, the River Project, What I Think About When I Think About Dancing and News from Islands. Havilah says, “I am proud of what we have achieved and the people I have worked with at Campbelltown Arts Centre, and excited to join CarriageWorks at such an important time in the organisation’s development. CarriageWorks holds a vital place in the cultural fabric of Sydney, and is home to an extraordinary group of resident companies. I look forward to building on the many achievements that CarriageWorks has already delivered” (press release).

In the meantime, one of CarriageWorks’ resident companies, Performance Space, has announced that Jeff Khan as its new Associate Director with responsibility for dance and performance. Khan is a “curator and writer with a particular interest in interdisciplinary projects and site-specific and socially-engaged practices” (press release; see also our interview RT96). From 2006 to 2010 he was the Artistic Director of Next Wave (RT98). He is currently a member of the Australia Council’s Dance Board and has held previous positions and guest curatorships at the MCA, Gertrude Contemporary and PICA. Exciting times in Redfern!

cold edge, hot summer

Writer and spoken word performer (and contributor to RealTime) Urszula Dawkins brings tales of sub-zero Svalbard to Midsumma Melbourne and cia studios in Perth, following her 2010 participation in The Arctic Circle creative residency—an ocean voyage around the high-Arctic, a few hundred miles from the North Pole (see RT100). She writes: “The romantic landscape gives way to the treachery of a nature that needs neither art nor art-makers, and the quest for ‘place’ is blasted away in horizontal snow-drifts, leaving only desire and the return to home…Polar bears, northern lights, glittering glaciers and an ice-class sailing ship sit side by side with the end of the sublime.” The program also features film and video pieces by Arctic Circle participants Katja Aglert (Sweden), Janet Biggs (US), Rebeca Mendéz (US/Mexico) and Laurie Palmer (US). Cold Edge: The Arctic Circle, Hares & Hyenas Bookshop & Café, Jan 25; www.midsumma.org.au; cia studios, Feb 3 www.ciastudios.com.au (please RSVP kate@pvicollective.com)

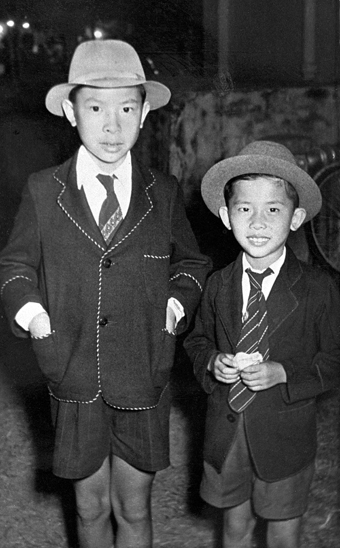

Alan and William Yang

photo courtesy of the artist

Alan and William Yang

australian-asian art connections

The Chinese Year of the Rabbit begins on February 3 and to celebrate the 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art is mounting Cinema Alley. For one night only, an open-air cinema at the heart of Chinatown will screen five short video works by contemporary Chinese artists Chen Chieh-Jen, Jun Yang, Ou Ning and Cao Fei (reviewed in RT96), Wang Qingsong (RT100) and Yuan Goang-ming. Their work explores “perceptions of cities, their transformation, experiences of alienation and the effects that history and tradition place on the individual” (website).

Elsewhere, Performance 4A is producing the COOLie Asian Australian Performance Event, to be held Downstairs at Belvoir St Theatre for two weeks, February 1-13. The first season, Stories East & West, sold out Belvoir’s Upstairs theatre last May. It featured Asian Australian artists exploring relationships with their ancestors and cultures and examining how these impact on their lives today. The new show features Chinese-Australian photographer, storyteller William Yang (RT96; RT47) and indigenous elder, researcher and historian Noeline Briggs-Smith swapping stories about their lives. The following work, About Fact, is billed as a “contemporary variety show” combining music, dance, comedy, monologue and song and featuring Asian-Australian artists Paul Cordeiro, Lena Cruz, Les Gock, Oliver Phommavanh, Suara Indonesia Dance Group and Jennifer Wong.

Artspace, in association with the Sydney Festival, is hosting Singaporean artist and filmmaker Ho Tzu Nyen in an exhibition featuring three major video works—NEWTON (2009), ZARATHUSTRA: A FILM FOR EVERYONE AND NO-ONE (2009/2010) and the centrepiece 42-minute EARTH (2009/2010), a ‘videographic’ remix in three long takes of 17th and 18th century Italian and French paintings in which the human body is penetrated, fragmented and re-arranged. On January 24 and 25 there is also a Live Sound Score Performance by composer and multi-instrumentalist Oren Ambarchi. Cinema Alley, 4A Contemporary Asian Art, Feb 11; www.4a.com.au; COOLie Asian Australian Performance Event, Belvoir St, Feb 1-13; www.belvoir.com.au; Ho Tzu Nyen, Earth, curator Blair French, Artspace, Jan 20-Feb 20, Live Sound Score Performance Jan 24-25; www.artspace.org.au

colbert and censorship

Here at RealTime we’ve been idly holidaying online, roaming the world wide web and catching up with the wickedly incisive Stephen Colbert who, on December 8 in his Tip of the Hat, Wag of the Finger segment, praised censorious Republican Senator Erik Cantor (the incoming House Majority Leader) with a damning serve of artspeak. Cantor had declared that the Smithsonian National Portrait Museum’s exhibiting of a video installation, Fire in My Belly, in which ants briefly crawl over a crucifix, was an insult to Christians, not least because it was being displayed over the Xmas period. The slight therefore warranted a threat to defund the Smithsonian. Colbert applauded the Jewish politician’s sensitive support for beleaguered Christians. “This defunding threat isn’t some cheap exercise in mindless censorship,” he argued. “It’s an anti-paradigmatic revolutionary work of conceptual art banning…Cantor’s art is about the art that isn’t there, making the inaccessible literally inaccessible.”

On Fox News, Cantor said, “When a museum receives taxpayer money, the taxpayers have a right to expect that the museum will uphold common standards of decency. The museum should pull the exhibit and be prepared for serious questions come budget time.” The Smithsonian subsequently removed the video, the 1987 work Fire in My Belly (David Wojnarowicz, Diamanda Galas) from Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture (Oct 30, 2010-Feb 13, 2011).

You can read more about the video, the conservative advocacy group the Media Research Center, and protests against the withdrawal of the work at Half Wisdom, Half Wit. You can watch Colbert’s Tip of the Hat, Wag of the Finger Art Report and see the rest of this episode of The Colbert Report featuring Steve Martin and some leading artists , including Frank Stella and Andreas Serrano in a droll assessment of the financial evaluation of art. Also available is an extended version.

RealTime issue #100 Dec-Jan 2010 pg. web

Sarah Jayne Howard, Not in a Million Years, Force Majeure

photo Lisa Tomasetti

Sarah Jayne Howard, Not in a Million Years, Force Majeure

A MAN STANDS HIGH UP IN THE DISTANCE, SPOTLIT, ABOUT TO JUMP, HIS VOICEOVER SPELLING OUT THE TENSION GENERATED BETWEEN THE IMPULSES OF HIS REPTILIAN BRAIN AND THE RATIONALITY OF ITS EVOLVED FORM, ALTERNATING BETWEEN SHEER TERROR AND THE ATTRACTIONS OF RISK. ONE, TWO, THREE, HE LEANS…BLACKOUT. WE DON’T KNOW IF HE ACTUALLY JUMPS, BUT ONE THING’S CLEAR, HE WANTS TO AND HE HAS KNOWLEDGE AND CHOICE. BUT FORCE MAJEURE’S NOT IN A MILLION YEARS BUILDS ITS PERVASIVE SENSE OF PHYSICAL AND EMOTIONAL CRISIS NOT FROM THESE EVOLUTIONARY ADVANTAGES BUT FROM INCIDENTS OF POWERLESSNESS AND UNCONSCIOUSNESS, WHERE CIRCUMSTANCES HAVE SUCKED AWAY THE PHYSICAL CAPACITY OR WILL TO ACT.

Some of the figures in Not In A Million Years—an airline attendant, a paraglider and a pair of miners—engage in jobs or activities that are inherently risky. The miners endure the collapse of a mine while the airline attendant suffers something unique: she is the lone survivor—found on the ground—of an aircraft that exploded at 33,000 feet. The paraglider is sucked up “higher than Everest” into the upper atmosphere, unconscious throughout and almost frozen, but miraculously survives (perhaps ‘preserved’ by the cold). Other figures haven’t taken the risks of employment or sport but the will to act is likewise denied them: a man in a comatose state for 10 years suddenly wakes to a world with which he is unable to engage. A woman wins a huge lottery prize but is rendered incapable of using it, fearing public attention and the risk her son might be kidnapped. Another character is a sporting champion (inspired by the story of an astonishing long-jumper), abused and shamed by her coach into mindlessly and dangerously excelling.

Elizabeth Ryan and Vincent Crowley, Not in a Million Years, Force Majeure

photo Heidrun Löhr

Elizabeth Ryan and Vincent Crowley, Not in a Million Years, Force Majeure

The horrors of these conditions are made palpable, played out on shifting clouds, fields and dunes of soft, snow-like sparkling crystals through which people wade fitfully—or, like the athlete, forcefully, as if battling sand or heavy surf—or in which they are buried. A man unearths the airline attendant in the first of a series of duets, cradling, lifting, helping her stand before an inevitable, sad collapse. The challenge of helping is further writ large in the frustrations of the wife of the comatose man as she struggles to clothe him while begging for his affection, trying to make him jealous, or in the mutual assistance enacted between the trapped miners, from time-filling chat to shared songs to the slightest of physical shifts to ease pain. Later the wife will drag her comatose husband through the ‘snow,’ unable to make him stand unassisted, amplifying the sense of helplessness experienced by carers as much as the victims of fate.

Max Lyandvert’s emphatic score moodily underlines the action—melancholy piano for the airline attendant, electronic pinging and pulsing for the athlete, ominous rumblings for the miners. Spatial transformations are also effected with the ‘snowscape’ swept away, replaced by mobile walls that frame the entrapment of the wife of the comatose man and the reclusive lottery winner, while the paraglider flies in the distance, often seemingly helpless, an almost constant reminder of the beauty and risk of human flight.

The instability of these aural and visual shifts resonates with emotional complexities as the interwoven tales unfold, some more detailed than others. Survivors like the airline attendant and the formerly comatose man cannot comprehend why they are treated like heroes. The man is bitter over the loss of time and love: “Where’s the miracle?” He cannot relate to his son or understand why his wife just didn’t give up on him—”Why did she keep me…like a piece of nostalgia?” Only a mate’s ironic “Guess what, stupid, you stopped smoking” cheers him.

These ‘accidents’ variously yield humour and fortitude, or reveal the strengths and weaknesses of relationships or result in uncomprehending despair and infinite frustration—the athlete is literally driven up the wall, repeatedly rushing at and bounding up CarriageWorks’ craggy stonework. Amidst such indeterminacy it’s odd that the figure who opened the performance, pondering a leap, returns to muse over a famous tightrope walk between skyscrapers in New York, picking over its meanings—sublime or absurd, inspirational? “Could I ever risk that? Am I ever that alive?” The victims of strange and not so strange accidents in Not In A Million Years have not taken undue risks (you might not like to paraglide, but many thousands do) and in several cases they certainly feel less than alive after their ‘accidents,’ and certainly neither adventurous nor heroic—their will-power had been suspended.

As if to underline a swing to a more optimistic view of the effects of extreme happenstance, the athlete, seemingly freed of her coach, spins and sweeps through the expanse in the first palpably choreographed movements. She draws the other performers with her into a collective dance in silence, cutting neatly through the ‘snow,’ hands pushing back over heads, fingers pointing, legs weakening at the knees (reminiscent of those characters who earlier collapsed into the ‘snow’) but rising up, looking up, suppliant even, asking not “Could I ever risk that?” but “How could I endure those states of being, of suspended will and self, with their all too existential consequences?”

I’m not certain that Not In A Million Years is conceptually consistent or that it fully exploits the potential of its ‘snowscape’ design—visually or sonically—while the deployment of the ungainly mobile walls functionally detracts from the overall eeriness and the soundscore occasionally verges on the melodramatic. But it’s a thoughtful and often disturbing creation that conveys the unbearable lightness of unconsciousness. For a dance theatre work, curiously it’s the naturalism of the affecting performances from Elizabeth Ryan and Joshua Tyler (not least as the wife and erstwhile comatose husband) that provide Not In A Million Years with its emotional centre of gravity, as their world and others around them spin out of control. I’m looking forward, anxiously, to experiencing Not In A Million Years again at Dance Massive in Melbourne in March.

Force Majeure, Not in a Million Years, director Kate Champion, assistant director Roz Hervey, designer Geoff Cobham, performers Vincent Crowley, Sarah Jayne Howard, Elizabeth Ryan, Joshua Tyler, original music, sound designer Max Lyandvert; CarriageWorks, Sydney, Nov 18-27, 2010; www.forcemajeure.com.au

This article was first published online Jan 17, 2010.

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 37, web

b.c., janvier, 1545, fontainbleu, l’association fragile

photo Marc Domage

b.c., janvier, 1545, fontainbleu, l’association fragile

IN CHRISTIAN RIZZO’S B.C., JANVIER, 1545, FONTAINBLEU, BLACK CURTAINS PART TO REVEAL A WHITE BOX STAGE LIT BY DOZENS OF TEA CANDLES SCATTERED ACROSS THE FLOOR. SCULPTURAL CLUSTERS OF BLACK FABRIC ARE SUSPENDED LIKE FLOATING INKBLOTS AT VARIOUS HEIGHTS. UPSTAGE CENTRE, DANCER JULIE GUIBERT, IN BLACK SKULLCAP-CUM-WIG, BLACK SHIRT AND PANTS AND SILVER STILETTO HEELS LIES ON A NARROW WHITE TABLETOP WITH HER BACK TO US. IN THE FOREGROUND STANDS CHOREOGRAPHER RIZZO, WEARING AN ANTIQUE-LOOKING RABBIT MASK, T-SHIRT, BAGGY JEANS AND HIGH-TOPS—AN ENSEMBLE THAT MAKES HIM LOOK LIKE A ROMANTIC-ERA PORCELAIN FIGURINE DRESSED AS A RAPPER. THE STAGE COMPOSITION IS EXQUISITE (A LITTLE CHEER GOES UP INSIDE ME).

Guibert gets off the table and performs a short, gestural score that has her bisecting space in flat planes, changing levels and implying geometrical shapes. The execution is meticulous. She will repeat this sequence for the duration, adjusting the details slightly, changing her spatial orientation and imperceptibly increasing the tempo. Superbly controlled, Guibert is all precision and grace, even on four-inch silver spikes. Rabbit-faced Rizzo takes his time moving the candles from the floor to the table, just a few at a time. Each part of this slow-moving image is thoughtfully placed. I can feel the surety of an expert artist’s hand. I let the picture seep into my nervous system like an opiate.

Once the initial hit has done its work, I want the piece to change. It does, but at a glacial pace. Guibert goes through her iterations. The sculptures are removed. The candles are extinguished. The quality of light goes from candle-flicker warm to walk-in-cooler frigid. I think this progression is supposed to feel like a graduated revelation but, beautiful as the final state is, the development is too slow for surprise. A high volume industrial sound score by Gerome Nox makes its presence felt part way through. The grinding drone tends to flatten out the nuance of the Guibert’s articulations. The lighting design, on the other hand, is a masterpiece of sensitivity. Designer Caty Olive’s interest lies in the instability and ambiguity of her medium. From the outset she gives us a restless light, almost constantly in flicker, that refuses to settle on a base colour. Within the highly reflective surfaces of the white box, Olive manages to create a depth of field in which Guibert, Rizzo and the sculptural objects come in and out of focus. Unlike the crush of the sound score, the active lighting design contributes a deft dynamism, responsive to the spatial adjustments at work and partnering well with Guibert.

b.c., janvier, 1545, fontainbleu, l’association fragile

photo Marc Domage

b.c., janvier, 1545, fontainbleu, l’association fragile

It’s a little hard on the eyes and ears at times. The unstable light, combined with Nox’s acoustic drone and the measured pace of the piece, makes me a bit sleepy. Maybe that’s the point: as I drift into semi-consciousness b.c., janvier, 1545, fontainbleu cuts a deep groove in my dream track. It stays with me in a way that most shows don’t. In the days and weeks since the show ended, the restlessness and dissatisfaction I felt at curtain has given way to a feeling of dream-saturated appreciation. When I think of the show now, I’m left with the fullness and clarity of the image.

The image, however, isn’t Rizzo’s first concern. He begins by building the choreography a step at time. His idea of choreography includes light, sound and sculpture as active partners. The ‘image’ is a natural result of such ‘partnering.’ In the 1990s, Rizzo and other choreographers were labeled in France as makers of non-danse, a designation that in retrospect only makes sense if you think of the dancer as somehow separate from the performance setting, moving in a featureless, empty space that doesn’t interfere with the purity of movement. Non-danse attempted to recontextualise the dancer—sometimes by placing them in a setting that was more ‘theatrical’ (for example, a living room), sometimes by putting the dance in a specific location and often by focusing on the bare materiality of the dancer rather than on the dancer’s technique.

These considerations, as well as others, forced a re-examination of dance and choreography. Previously, speaking, playing guitar, cooking, lecturing etc, were expressions of the body that didn’t fall into the category of dance. Things like set pieces, sculpture, props, lights and sound were usually treated as add-ons, always peripheral to the primacy of the human body. Non-danse puts the dancer-body in dialogue not just with other dancers, but also with all the other elements mentioned above. In a Rizzo show this requires a shift in the kind of attention a spectator brings to the performance. What is the interplay between dancer and light? Between sculpture, space, and sound? Like the lights, my attention flickered between all of these. Then the front part of my brain relaxed, I got sleepy, my consciousness widened and b.c., janvier, 1545, fontainbleu continued its iterations in my memory log.

For information about Christian Rizzo, visit the On the Boards blog, see “Christian Rizzo discusses b.c., janvier, 1545, fontainbleu” and read Rizzo’s dialogue with John Jasperse. For a sample of Rizzo’s work, see Mon Amour and Avant Un Mois on YouTube.

b.c., janvier, 1545, fontainbleu l’association fragile, choreographer Christian Rizzo, On the Boards, Seattle, Oct 10, 2010

This article was first published online Jan 17, 2010

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 39, web

Ryan Kwanten, Griff the Invisible

JAN CHAPMAN HAS A KNACK FOR FINDING RISING TALENT WHEN IT COMES TO AUSTRALIAN SCREENWRITERS AND DIRECTORS. IF HER NAME IS STAMPED ON A FILM (AS PRODUCER OR EXECUTIVE PRODUCER) IT MEANS THE FILM WILL LIKELY HAVE A UNIQUE VOICE WITH GREAT CHARACTERISATION AND WONDERFULLY STRANGE TOUCHES — LOVE SERENADE (SHIRLEY BARRETT), JANE CAMPION FILMS INCLUDING THE PIANO AND BRIGHT STAR, LANTANA (RAY LAWRENCE), SOMERSAULT (CATE SHORTLAND), SUBURBAN MAYHEM (ALICE BELL; PAUL GOLDMAN)—AND NOW HERE COMES GRIFF THE INVISIBLE FROM WRITER-DIRECTOR AND NOVELIST LEON FORD.

Recently selected for the Toronto and Berlin Film Festivals, Griff the Invisible features an Australian superhero not quite able to leap tall buildings in a single bound and who, by day, suffers bullying in the workplace while exacting revenge at night by fighting injustice in his neighbourhood.

Recent Australian film has tended to emphasise rural nostalgia (The Tree, Summer Coda, Lou, The Boys Are Back), gritty realism (Animal Kingdom) and mainstream comedy/romance (Bran Nue Dae, I Love You Too), so it’s great to see a director who’s not afraid of an experimental touch or play with genre. Leon Ford is well-known as an actor (Beneath Hill 60, Changi) while his short films Katoomba and The Mechanicals have shown a real talent for writing in particular, winning awards at the Sydney and St Kilda Film Festivals. He joins a spate of actors (Rachel Ward, Serhat Caradee, Anthony Hayes, Nash Edgerton, Matthew Newton) turning their hand to directing, with accomplished results for their first features. These directors also have a good feel for casting: Griff the Invisible goes against type with Ryan Kwanten (who does awkward as well as he does tough-guy in Red Hill and True Blood), Maeve Dermody (Beautiful Kate) as the fragile but potent Melody, and Toby Schmitz (The Pacific, Three Blind Mice and, onstage, Ruben Guthrie for Belvoir) charismatic as the arrogant bully Tony.

The film opens with a quotation from Oscar Wilde—“Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth”—as we enter the frame of a large telescope, eyeing the cityscape, before panning around a room full of surveillance equipment on red alert for action in the streets. A woman walks, pursued by a man in a strange top hat. This is a nice parody of the big-budget blockbusters, like Superman Returns, filmed on our shores, before we’re introduced to our truly B-grade superhero in a cheap black rubber suit with a large gold G on the chest, for Griff, not Gotham.

Griff the Invisible has no superpowers that we can see but carries a blade that he swipes cartoon-style through the necks of his assailants. Kwanten has the physical ability to transform easily, moving beautifully between his alter egos. He practises his lines in front of the mirror at home—“It’s okay, you’re safe”—and searches for the right descriptor—Griff the Protector? Griff the Hidden?—as much for himself as the victims he defends.

Toby Schmitz, Griff the Invisible

By day, he is stalked by terrors even worse: the open plan office. Nervous and reluctant to engage, Griff spends his days on the phone answering client enquiries, trying not to talk to anyone at close range. Office bully Tony—a show-off in front of the ladies, a man with a strong sense of entitlement, used to getting exactly what he wants—is all too aware of Griff’s weaknesses and regularly harasses him. Ford (aided by Schmitz’s talents) cleverly chooses to portray Tony as an attractive and vivacious character (rather than the fat loser bullies often seen in US sitcoms), sexy and louche, with that right blend of menace and charm.

Maeve Dermody and Ryan Kwanten, Griff the Invisible

Griff brings his surveillance skills into the office, spying on colleagues with a series of ingeniously simple gadgets (he’s no Batman) designed to help him communicate without words. But the enigmatic narrative means that we’re never quite sure of the nature of Griff’s inner/outer world. Is it a fantasy playing in his head? Does he really hit the streets? Is he battling a mental illness in which he’s completely delusional? His girlfriend-to-be, Melody, a science student transfixed by the space between atoms, certainly believes all he says but, then again, she is the only character who can’t see him when he’s ‘invisible’ (a brilliant running gag). Getting that right balance between pathos, humour and occasional farce is extremely difficult and Ford manages it well; the film hums along with its strange dialogue, a visually inventive palette, the melancholic lead romance and real empathy for the loneliness of the central characters.

The entire plot fixes on the fight/flight response and which way Griff will turn at any moment. His life is about boundaries: who can cross them, when and where, and the possibilities of transformation. Melody, instead, wants to transcend her limitations right here right now, even attempting to walk through walls to reach Griff. With his central couple, Ford has almost effortlessly created (where films like I Love You Too and Summer Coda haven’t quite succeeded) an alluring and enduring romantic comedy, with characters complex and intertwined. It’s a strange and whimsical world for the viewer to inhabit but a terrific and courageous debut.

Griff the Invisible, writer, director Leon Ford, producer Nicole O’Donohue, executive producers Jan Chapman, Scott Meek, cinematography Simon Chapman, editor Karen Johnson, sound designer Sam Petty, production designer Sophie Nash, original music Kids At Risk; www.grifftheinvisible.com

This article was fist published online, Jan 17, 2010

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. web