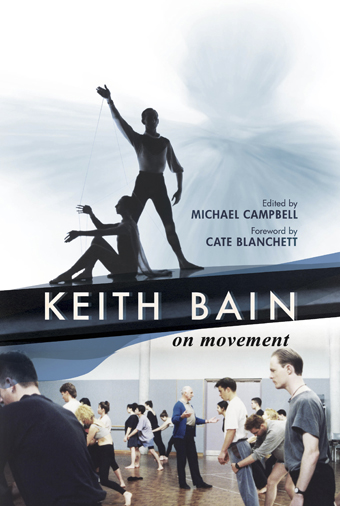

Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Read reviews of works in Dance Massive from the RealTime archive.

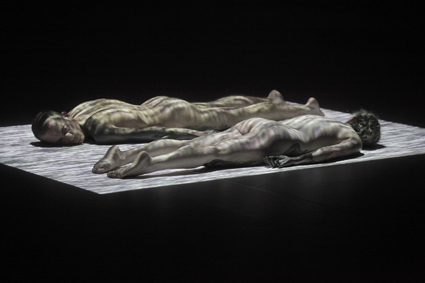

the unbearable lightness of unconsciousness

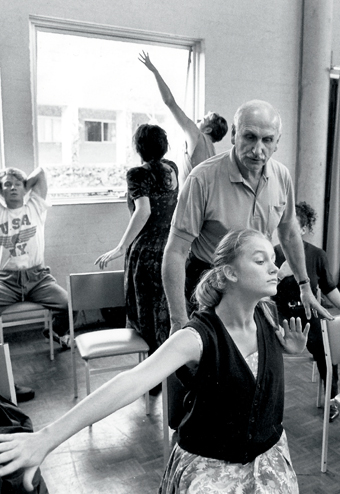

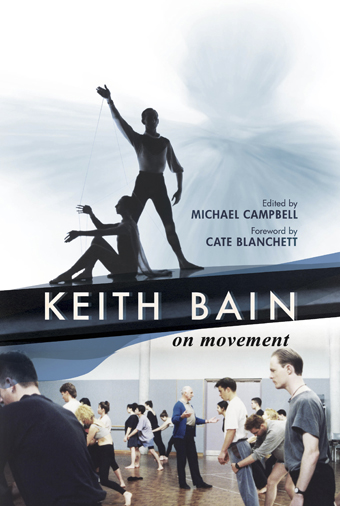

keith gallasch: force majeure, not in a million years

reflections on self and body

pauline manley: narelle benjamin, in glass, chunky move, faker, spring dance 2010

work world upside down

pauline manley: branch nebula, sweat

responsive objects

philipa rothfield, shaun mcleod, the weight of the thing left its mark

measuring up & mining the moment

philipa rothfield: luke george, now, now, now

amplification, philip adams

philippa rothfield

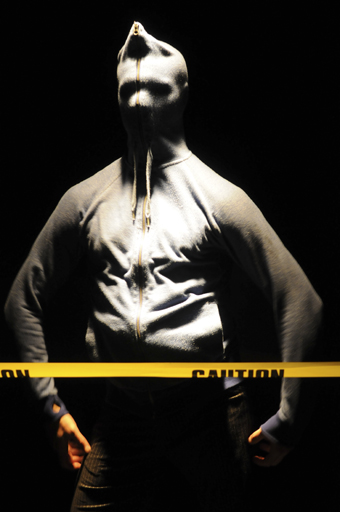

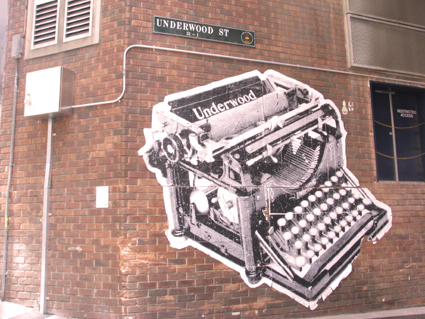

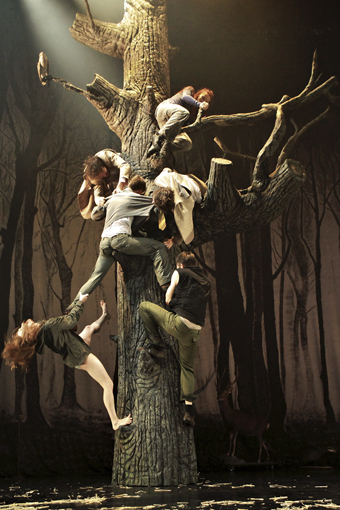

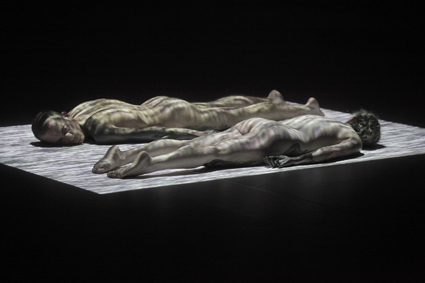

Ahil Ratnamohan, Sweat, Branch Nebula

photo Heidrun Löhr

Ahil Ratnamohan, Sweat, Branch Nebula

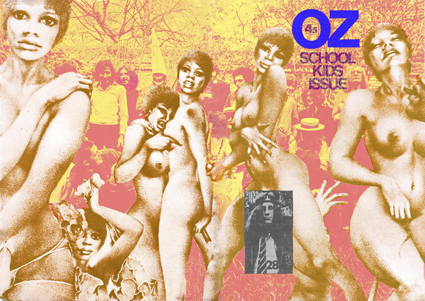

DANCE MASSIVE IS AVOIDING THE F-WORD. ACROSS ITS PRINT AND PUBLICITY, THE BIENNIAL PRESENTATION OF A CONCENTRATION OF CONTEMPORARY DANCE IN MELBOURNE IS CALLING ITSELF A “COLLECTION.” A “PROGRAM,” AN “INITIATIVE.”

To discuss “the Massive” I met with Steven Richardson, Director of Arts House in Melbourne. Richardson was instrumental in founding Dance Massive, urging the Australia Council following his time on the Dance Board to consider a concentration of dance programming both to attract international attention to new work and to provide a place for the sector to meet and share experiences at a national level. Arts House, a complex of venues run by City of Melbourne, plays a central coordinating role for the Dance Massive program, although Richardson admits that, “surrendering half of our six month program to make this work is not ideal.”

Without an artistic director for Dance Massive, Richardson tells me, there is no festival infrastructure and all programming is supported by existing State and Federal resources allocated to the three Melbourne venues where the work is presented. “There hasn’t been the funding to create a central framework. When the idea first came up, we considered trying to create a national program by coordinating venues around the country. It quickly became apparent that this was going to be impossible. It would take 15 years for us to find the same two weeks across every dance venue nationally. So we decided to start in our own backyard.”

The coincidence of Malthouse Director Michael Kantor and producer Stephen Armstrong investing in contemporary dance and physical theatre programming and the energy of David Tyndall as the new(ish) Director of Dancehouse created sufficient momentum in Melbourne for the project to take off in 2009. “It’s hard to apologise for the focus on Melbourne,” Richardson says, “There is arguably the healthiest ecology for dance here, with a concentration of institutions, companies like Chunky Move and lots of independent artists and audiences.”

In its first edition Dance Massive programmed 14 works from across Australia across the three venues. The program was well attended and received positive feedback and critical acclaim. Dance Massive was also pronounced a success for the way in which it raised the profile of dance in the media and created a meeting point for artists and companies to see each others’ work and network during a concentrated period. The same venues have joined to create Dance Massive 2011, and several of those artists included in the original program are making a return appearance. “We each have our own curatorial framework, our own audiences and remits regarding programming,” says Richardson. “but there has been some very interesting cross-fertilisation between the venues since the first Massive,” he adds. “There has been surprisingly little tripping over each other too; we are all interested in contemporary work, but our curatorial approaches are slightly different and we have worked hard to ensure that the work falls where it needs to fall.”

Richardson is referring to the fact that the program is broad, both in terms of its definition of dance (including a physical theatre company such as Branch Nebula), its inclusion of generations of makers, (from Trevor Patrick to Luke George) and its accessibility (from the popular dance theatre work of Force Majeure and Shaun Parker to the relatively obscure independent work of Deanne Butterworth and Matthew Day).

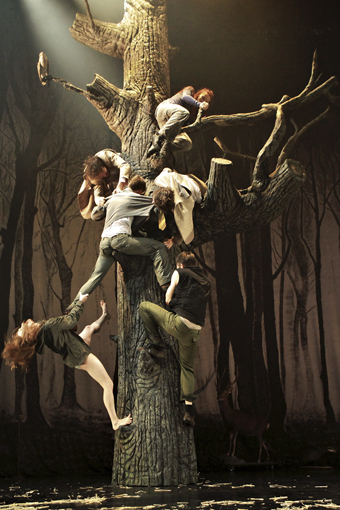

Dance Marathon, bluemouth inc

photo Gordon Hawkins

Dance Marathon, bluemouth inc

Whilst the first Massive included only Australians, there are artists from the UK and Canada in the 2011 program. “The international work is directly linked to Australian artists,” Richardson explains. “The bluemouth piece from Canada, Dance Marathon, is populated by local artists because it is built upon local participation. It was an important agenda item for Arts House to include a participatory element this year and the Dance Marathon project has been receiving incredible reviews wherever it plays around the world.” On the other hand, Billy Cowie, from the UK, has made his piece around an extraordinary Australian performer.

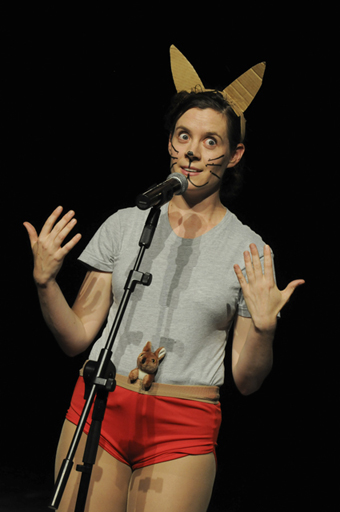

Now, Now, Now, Luke George

photo Jeff Busby

Now, Now, Now, Luke George

Richardson acknowledges that certain States and Territories are not represented in the final program but is adamant that Dance Massive is curated through the call for applications combined with the practical resources of the venues involved. “We would need a lot more money to support more companies to travel from interstate.” Richardson is aware of the absence of Indigenous work in the program. “It is not missing through any lack of trying,” he states,” The call is a rather brutal process, which can only consider the work that is out there and ready to go at the right time. Although we did get over sixty applications from the call this year, we also went out to our networks as presenters in order to find the best possible work.”

Richardson goes on to talk about the National Dance Forum associated with Dance Massive as a place where conversations around Indigenous and regional work can take place. “We have been able to include more spaces-in-between this year,” he says and cites the two international residencies and the dance on film program as initiatives that seek to address the aspiration of all three venues to create a place where dance artists and enthusiasts can meet. The National Dance Forum, led by Ausdance and the Australia Council and taking place over a long weekend during Dance Massive, will involve international choreographers such as Pichet Klunchen from Thailand with national dance artists in a series of forums, conversations and provocations designed to inspire art form development, in a similar fashion to that achieved during the National Theatre Forum in 2010.

Arts House will host the 2011 Tanja Liedtke Foundation Fellow, Katarzyna Sitarz, during Dance Massive. Sitarz will direct a residency at Arts House that will involve local independent artists and will take part in a new collaborative project directed by Lucy Guerin. Also during Dance Massive, the Australia Council’s IETM program, directed by David Pledger in Brussels, will send Norwegian choreographer Heine Avdal of deepblue company to undertake a residency and build relationships with Australian dance artists.

The venues and companies worked together to create a hit list of international presenters to invite to Dance Massive. Around a dozen high profile programmers from Europe, Asia and the US will attend. Dancehouse will also target a handful of French presenters in a special initiative. “It is important for the work to be shown in full, in the best possible theatrical conditions,’ Richardson says. “We also try to attract national and regional presenters,” he continues, “Although that is never easy. Last time we had half a dozen regional presenters attend and this year we hope for more.”

Richardson is optimistic about the impact of the 2011 program and is particularly looking forward to the two new productions by Chunky Move as well as the site-specific presentation, Drift, by Anthony Hamilton and the sound installation by composers Madeleine Flynn and Tim Humphrey. “I am hoping some of these projects will turn a few heads about what the nature of dance engagement can be,” he says.

Despite his enthusiasm, Steven Richardson is sanguine about the future of Dance Massive with no illusions about the third edition planned for 2013 being a shoo-in. “Once we get through March, we will start thinking about what we want Dance Massive to be,” he says. “Perhaps there is another model out there; something more nimble or more relevant to current practice.” Dance Massive is not a festival, or a showcase, that much is clear, but what it is and what it could be, seems to be tantalisingly up for grabs.

Throughout Dance Massive, RealTime reviews and interviews will appear online at www.realtimearts.net.

The considerable Dance Massive program includes works by Chunky Move, The Shaun Parker Project, Narelle Benjamin, Michelle Heaven, Helen Herbertson, Balletlab, Deanne Butterworth, Matthew Day, Antony Hamilton, Force Majeure, Trevor Patrick, Luke George, Branch Nebula, overseas guests Billy Cowie, John Jasperse Company and bluemouth inc, and the welcome return to Australia from France of Rosalind Crisp and Andrew Morrish.

–

Dance Massive: partners Arts House, Malthouse Theatre, Dancehouse; Melbourne, March 15-27; download the program at www.dancemassive.com.au

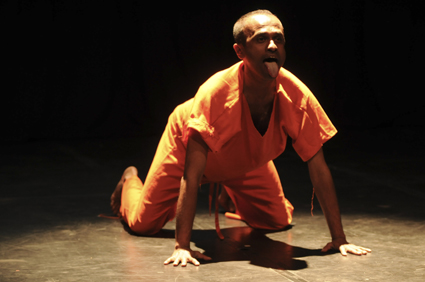

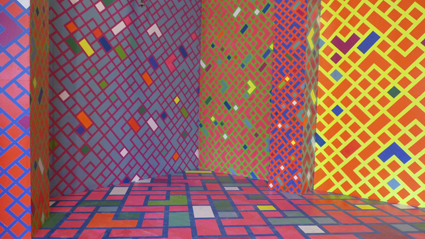

Carlee Mellow, Expectation

photo Rachel Roberts

Carlee Mellow, Expectation

WOMAN TEETERS IN THE DISTANCE, A GIANT PUMPKIN FOR A HEAD. SHE CUTS A SURREAL FIGURE. SHE IS IN HEELS, SKITTERING ACROSS A SMALL PROSCENIUM ARCH STAGE. VEERING FROM SIDE TO SIDE, SEEKING EQUILIBRIUM, THE WOMAN-VEGETABLE FAILS TO SETTLE, FAILS TO ACHIEVE STASIS. SHE ABANDONS THE TASK, SQUIRRELING ALONG TOWARDS THE DISTANT AUDIENCE. THE PROSCENIUM ARCH OFFERS A TALE, OF WOMAN AS OBJECT, AS HYBRID, BUFFETED BY ELEMENTS BEYOND HER CONTROL.

She is so far away that we watch almost dispassionately. The frame in a distance flattens. When she leaves, she becomes more real, a body rather than an image. No longer part vegetable, she comes towards us, moving to a melange of rhythms. She draws upon a history of dance training, pulling out moves and stringing them along a line. Inexorably, she approaches. As she nears, her body becomes round, flesh, soft. She dances nearer and nearer until her face becomes a player. Emotions, affects and intensities flicker then pass. Not exactly real but not quite surreal either, like switching stations on the radio.

Facing the audience, she emits a string of sounds. We are close now. The music is part of all this somehow. It matches the shifts, the proximities, the intensities, the progress. It seems we are at a peak. Clothes come off. Her naked body speaks, of dancing; muscular, buff. Even nudity tells a story. When the performers in the musical Hair stripped off, their nudity made a statement. Mellow’s nakedness emerges after a slew of expletives, like a full stop.

From a linear point of view, thus far the gaze of the audience has been increasingly enhanced by the tactile approach of a body. The volume of its flesh has been continuously increasing. Beginning as a distant figure, a subject-object, she is now more assertive, an intensity making decisions rather than a thing that responds.

The next phase is more twisted. She finds clothes and pursues a duet with a rope, melding and folding in movement. She traces a retreat to the rear of the theatre space, threading her way towards an ultimate inversion. She hangs upside down, like the Hanged Man of the Tarot pack. Technically and traditionally, the Hanged Man represents submission. Not submission as annihilation but giving up something to achieve something else. A creation through reversal, perhaps.

While Expectation follows a linear pathway of increasing revelation, it also reverts into a twisted transformation. Perhaps nothing is revealed. Is something expressed? Mmm. What I perceive is a powerful commitment, an intensity of feeling, a modulation of theatrical effect and an episodic movement through phases. The cavernous Arts House space has been treated to good effect, creating frames and scenarios that make this piece feel like more than a solo work. The shifting occupation of its massive depth—far, near, high, low and diagonally—cuts back from any linear sense of progress. We are rather treated to a series of differences that vary in intensity. Mellow exudes a performative strength that seems to heighten as she comes nearer. Perhaps her own energy becomes more directed toward the observer when she vocalises and strips or perhaps the observer reciprocates something in response.

Expectation follows Carlee Mellow’s performance in Deborah Hay’s solo project, In the Dark (RT98, p22). It resonates with Hay’s attitude towards performative attention. Its theatrical tenor also suggests Margaret Cameron’s dramaturgical influence—whimsical, surreal, with a strong performative focus. Since Hay’s work is about performance quality rather than any physical look, the movement belongs to Mellow. There is a trace of Ros Warby too. Mellow’s weird soundings reminded me of Warby’s vocalisations when performing Hay’s work, as if both women were abducted by the same aliens.

My enduring impression of Expectation is a sense of delight at Carlee Mellow’s courage and commitment. There is a freshness in this work; a degree of structure but also an aliveness that left me alert. Perhaps this piece is not alone in its concern to achieve something in the moment, to connect with its audience, but it does so in its own way.

Arts House, Future Tense: Expectation, choreographer, performer Carlee Mellow, composer Kelly Ryall, design Bluebottle, dramaturgical consultant Margaret Cameron, Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall, Nov 9-14, 2010

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 41

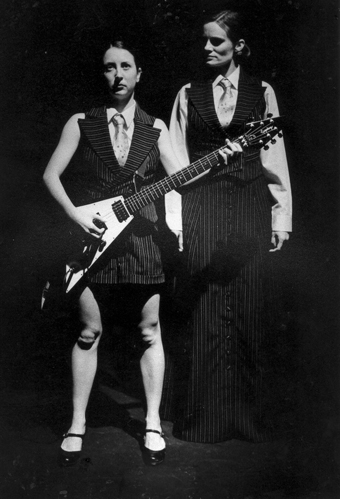

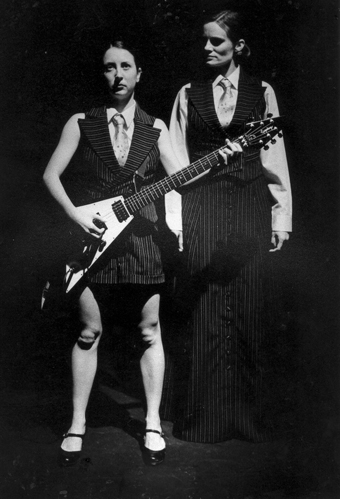

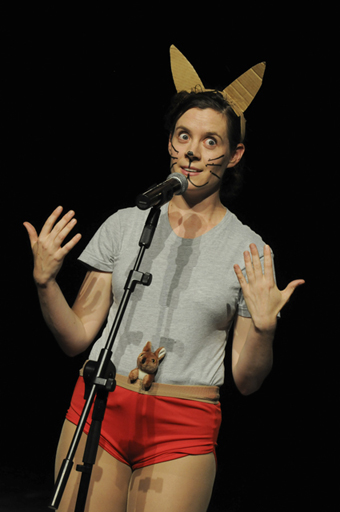

Leisa Shelton, Irony is Not Enough: Essay on My Life as Catherine Deneuve, Fragment31

photo Ponch Hawkes

Leisa Shelton, Irony is Not Enough: Essay on My Life as Catherine Deneuve, Fragment31

THE LAST TWO PERFORMANCES IN THE ARTS HOUSE FUTURE TENSE SEASON, BY MELBOURNE’S FRAGMENT31 AND THE GERMAN-ISRAELI TEAM JOCHEN ROLLER AND SAAR MAGAL, SHARE DOUBLE FOCI: IRONY AND TRAUMA.

Fragment31’s Irony is Not Enough: Essay on My Life as Catherine Deneuve performance is a theatrical rendition of Anne Carson’s poem of the same title, which turns the poet into a third-person Deneuve, and narrates her infatuation with a female student through the doubly ironic prism of cinema and classical references. What would Socrates say, she wonders, her words laced with mature, weary detachment. Deneuve, the cinematic Barbie doll, effortlessly blank, is inserted in the place of a complex self. (In The Guardian, December 30, 2006, Germaine Greer remarked that so devoid of personality have Deneuve’s roles been, that she cannot recall a single line any of her characters ever uttered.)

Fragment31 play with the representation of the fractured desiring self by simulating film. Shelton/Carson/Deneuve walks to the Metro; receives a phone call in her office; waits in a hotel room. Each scene is sculpted in filmic detail, each physically and narratively disconnected from the other, each floating as an island of naturalistic imagery in the mangle of props and wires of the Meat Market stage space. Sound, light, set, actors and musician, and designers, onstage too, come together in fitful fragments—the coalescing of the desiring, decentred self into one sharpened and fuelled by love. Even the narrator, Carson/Deneuve, is played by two actors: Leisa Shelton for body, Luke Mullins for voice. It is an attempt to discipline desire with a muffle of irony, dissimulation. But irony is not enough to stop infatuation; self-knowledge does not mandate control. Desire shows through. The poem crackles; the stage version, murkier and not as focused, less so.

Jochen Roller, Saar Magal, Basically I Don’t But Actually I Do

photo Friedemann Simon

Jochen Roller, Saar Magal, Basically I Don’t But Actually I Do

If in the first work irony is employed as the girdle of trauma, to keep the fractured self in one piece, in the next work irony is a safe, fenced pathway to the exploration of trauma. Basically I Don’t But Actually I Do is Israeli choreographer Saar Magal’s answer to a question: whether to make a work about the Holocaust with friend German Jochen Roller or, rather, not about the Holocaust at all, but third generation Israelis and Germans.

It opens with a discussion over the order of epithets—which layer of identity comes first? They agree: German Jew, black Jewish German, even gay German black Jew; but, says Magal, “we’re not going to talk about Palestine.” Magal and Roller change clothes, from the yellow of the Star of David to the brown of the SS uniform, and back. They play Holocaust testimonies on tape. They enact a series of iconic WWII photos: Magal collapsing into Roller’s arms, Roller shooting Magal, vice versa. Magal says, “This man stole a book from a Tel Aviv bookshop!” And Roller recites, “I don’t remember. Everyone was doing it. I was simply there.”

We are asked to take our shoes off, walk, sit and, later, to get up. We don’t understand. “Aufstehen!” shouts Roller. Some of us are randomly marked out, and one person pulled out of the crowd, to dance briefly with Magal, and then sent back. The show creates small moments of terror: we are dislodged from our audience complacency, but nothing bad ever happens, because it’s not that kind of show.

Basically I Don’t But Actually I Do is a catalogue of images enacted, repeated, but only as traces. It assumes a traumatised audience, for which every hint will be a trigger of memory. But, remarkably, it is a work that refuses to create false memories. It tests recognition; it has exactly as much content as the audience brings to it. It is up to each person to see genocide in the stage imagery, hear the Nuremberg Trials in the dialogue. The piece gently probes. How much do we still remember? What does it mean to us? What does it do to us?

In Australia (as opposed to Germany or Israel), the answer is not much. There were some walk-outs, which I cannot imagine happening at a Holocaust tear-jerker (for reasons of decorum). But for those to whom it meant something, Magal and Roller created a tasteful, careful little memorial space, in which a past event was reconnected to the present, and the relationship between the two weighed up.

One could say that the risks in Basically…never felt sufficiently dangerous, the stakes never high enough to justify the pussyfooting (one German critic called it “politically correct”). The love woes of Deneuve/Carson are saturated with much greater danger, despite the ironic title. However, Basically…uses irony differently, as a way of coming closer to something unspeakable, rather than pulling away from it. If traumatic desire is a sore one still wants to pick, the Holocaust is a trauma of a completely other kind, one to tiptoe around carefully, holding hands.

Fragment31, Irony is Not Enough: Essay on My Life as Catherine Deneuve, creators, performers Luke Mullins, Leisa Shelton, music Jethro Woodward, set Anna Cordingly, lighting Jen Hector; Nov 16-20; Basically I Don’t But Actually I Do, creators, performers Jochen Roller, Saar Magal, lighting Marek Lamprecht, soundtrack Paul Ratzel; Arts House, Meat Market, Melbourne, Nov 24-27, 2010

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 38

© Jana Perkovic; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

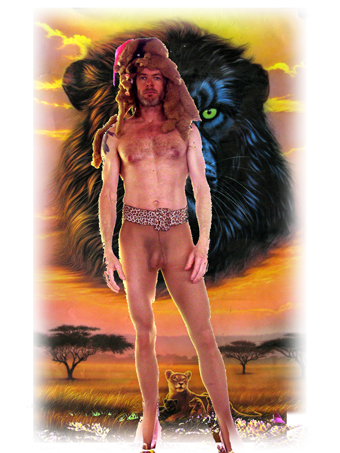

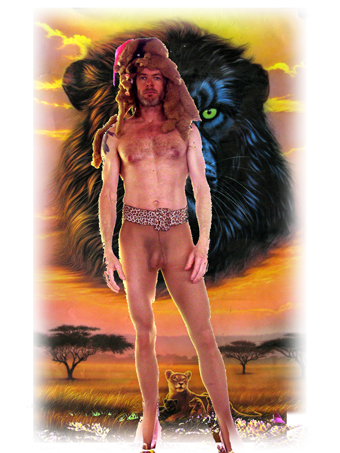

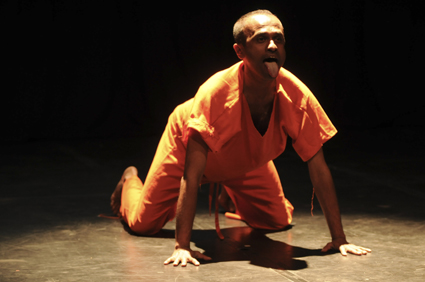

Africa, My Darling Patricia

photo Jeff Busby

Africa, My Darling Patricia

THE LAUNCH OF NEXT STAGE 2011 WAS HOT. THE TEMPERATURE WAS UP, THE WHARF 2 FOYER CRAMMED WITH ENTHUSIASTIC 20 SOMETHINGS AND ARTISTS THRILLED TO BE IN THE PROGRAM WHICH STC ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR TOM WRIGHT AND LITERARY MANAGER POLLY ROWE OUTLINED IN A NEAT DOUBLE ACT FOLLOWED BY A FEW WORDS EACH FROM DIRECTORS AND PERFORMERS.

Next Stage is focused on development, emerging artists, providing alternatives to the STC’s main program, attracting a different audience, “not trying to please everyone all the time” and “not setting expectations too high” for new works. Tickets are $25 and there’s a free beer per ticket offer.

First up in Next Stage 2011 is German playwright Roland Schimmelpfennig’s Before/After, directed by Cristabel Sved, who spoke mid-rehearsal of “the luxury of all working together and with all the languages of the stage being used.” A nice change from the challenges of resource-scarce independent theatre. With its 51 short scenes the play should provide a fascinating companion piece to the STC mainstage production of German writer Botho Strauss’ epic Big and Little Scenes.

Sam Routledge a collaborator with contemporary performance group My Darling Patricia expressed the group’s pleasure at being in Next Stage with Africa, originally a Malthouse commission, and outlined the origins of the work in the true story of German children caught running away to Africa. Told with puppets and broken toys, Africa presents a magical Australian perspective on childhood pain and fantasy.

Another innovative Sydney-based performance group, Post, in typical form stacked on a stand-up turn anticipating the themes and fun antagonism of their new work Who’s The Best? which was developed with Next Stage’s support in 2010.

Also developed in 2010, Money Shots will feature 15-minute plays about money by Tahli Corin, Duncan Graham, Angus Cerini, Rita Kalnejais, Zoe Pepper and The Suitcase Royale, directed by Richard Wherrett Fellow Sarah Giles and designed by Alice Babidge. As well the program continues the Rough Drafts series, week-long creative developments followed by free showings that allow audiences to track the growth of a play.

The heat’s on: Next Stage 2011 promises intense diversity of form as well as the means for hot-housing new work from a fascinating range of theatre and contemporary performance artists.

Sydney Theatre Company, Next Stage 2011; for season dates see

www.nextstage2011.com.au/

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 41

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Toy Cart, Stalker, 1991

photo Geert Kliphuis

Toy Cart, Stalker, 1991

STALKER IS ONE OF AUSTRALIA’S MOST IDIOSYNCRATIC PERFORMANCE COMPANIES, EVOLVING OVER TWO DECADES FROM STILT-WALKING SHOWS—WITH VERVE AND INTELLIGENCE—INTO INCREASINGLY SOPHISTICATED, RICHLY THEMED LARGE-SCALE WORKS, ALL PERFORMED OUTDOORS, AND THEN DIVERSIFYING INTO TWO COMPANIES, STALKER AND MARRUGEKU. BOTH HAVE RESHAPED NOTIONS OF PHYSICAL THEATRE, INCORPORATING OTHER ARTFORMS AND EMBRACING SOCIAL, POLITICAL AND METAPHYSICAL ISSUES AND THEMES WHILE ACHIEVING INTERNATIONAL RECOGNITION.

Sydney-based Stalker is co-directed by David Clarkson and Rachael Swain, each contributing discrete shows to the company repertoire, while Marrugeku is co-directed by Swain and Broome-based choreographer Dalisa Pigram. I spoke with Clarkson and Swain after Stalker celebrated its 21st year at the end of 2010. Such longevity for a continually innovative company is quite an achievement, not least in a country of short-lived artistic ventures.

starting out on stilts

Clarkson tells me that an early version of the company had played in New Zealand for three years, but reformed in Sydney where it was joined by Swain in 1989 and given “$10,000 cold cash by the Sydney Festival after I showed them some of our New Zealand work and they said, ‘It looks great!’” Swain and Clarkson point out that their starting out was timely—the Expo in Brisbane and the Bicentennial had programmed a substantial number of outdoor works, as did the Perth Festival and the Spoleto Festival in Melbourne directed by John Truscott. Clarkson recalls that “within a year we were touring Australia-wide and within 18 months we were in Europe.”

I asked how the pair would describe their early work. “It was street theatre. Very high energy,” says Swain. “When we first got to Europe we made quite a big splash. David and I both grew up in New Zealand and I think there was a sense of the rhythms and energy of the Pacific in the work. It was quite pumping.” Adds Clarkson, “Our work was stilt-based and we took stilts somewhere that no-one else had. Dive rolls, backbend get-ups, carrying each other, throwing each other to the ground, picking each other up. Very bruising. ‘Hell for leather,’ that’s what it was. Stilt acrobatics.”

Swain mentions that Stalker was working with choreographers as early as their second show, Toy Cart (1990): “Nigel Kellaway directed and Rosalind Crisp choreographed and it premiered at Spoleto in 1990. It was high energy but it was also quite visually driven work and quite lyrical—a strong aesthetic that exists to this day.” Clarkson recalls that Swain “was never in love with Fast Ground (1989), our first piece, but looking back at it and at Grotowski’s movement work I can see connections—muscle and bone work, always distinctive from circus even though stilts are a circus thing. It was always for me about embodiment: ‘a state of being’ expressed through the body and what visual imagery we might use to support that embodiment.”

Swain and Clark acknowledge significant differences between their bodies of work, their aesthetics and Marrugeku’s artistic direction. Marrugeku started in 1995, commissioned into existence by Perth Festival. Stalker produces Marrugeku, but the company has its own life, based first in Central Arnhem Land for seven years and subsequently in Broome for eight, and with its own steering committee and direction. “But,” says Swain, “there are certain core elements that link all three bodies of work, combining dance theatre processes and aesthetics with circus forms and a fairly poetic, layered dramaturgy prevalent in all the works. David and I worked collectively to make material initially and then slowly brought other people in—Sue-ellen Kohler choreographed the third work we did, Angels ex Machina (1993)—often in very strong collaborative partnerships. Both of our processes are physical—we make material on the floor—like choreographers.”

working europe

Some of the aesthetic influences on Stalkers’ work came from their rapid arrival on the European summer festival street theatre touring circuit in their first year of existence. “We were exposed to a whole raft of European companies from the small street theatre acts through to really large scale: Generik Vapeur, La Furas dels Baus, Les Ballets C de la B, Vis-a-Vis, Dogtroep, all making very ambitious, large scale work.” Clarkson says that the company saw a model they thought they could adapt. “Some of the shows were in the streets, with a full 1,500 seat grandstand and all the production values, like the Dogtroep work. We saw a model used to create an incredible audience base and access to touring circuits, came back here and tried to function between the two markets, Europe and Australia. For about a decade that was both our advantage and, to a degree, our bête noir. We were trying to exist as if we were a European company but there wasn’t the market here for large scale outdoor shows outside the five major festivals.”

Swain regrets that “for me, the only presentation in Australia I’ve had outside a festival has been when the Sydney Opera House commissioned Incognita (2003). We’d spend our year in the European summer and come back for the Australasian summer for 10 to15 years.” Clarkson recalls that “in the early years we were on the road for 10 months of the year.” In the mid-90s, when Justin Macdonnell was the company’s manager, its circuit extended to Latin America, as it did to Japan with Marguerite Pepper and Rosemary Hinde. Clarkson says, “We were really surviving by touring and weren’t really funded early on. For youngish performers it was a tremendous experience and great exposure for us, an exciting way to live, but the ensemble burnt out. You can’t actually live by touring eight or nine months of the year.”

a model for survival

I asked when it was that Swain and Clarkson decided not to work together. Clarkson explains that he took “a big sabbatical in 1999. Blood Vessel was a Stalker show without me performing in it. I was in the States. Throughout the 90s we’d had a very close working relationship but then decided to go our own directions. [Arts consultant] Antony Jeffrey came in to work with us as facilitator to devise a new model. I think we both thought it meant either ending the company or one of us taking over. Personally I think what we got is a really great model for survival in the arts—shared infrastructure and management for two bodies of work that have similar sets of concerns.” Swain says, “it’s become a way of sharing resources and a point of dialogue and support for each other’s work, which I think we possibly wouldn’t have come up with ourselves. And so Antony is to be credited.”

market adjustments

Swain says she “went very strongly into the large scale outdoor theatre model and somehow managed to make that function until the dance theatre element of it became stronger and stronger and the large scale outdoor European summer festivals didn’t know how to program it. It was somehow too ‘arty’ for the summer festival world and the dance festivals that were starting to get interested didn’t know how to present outdoor work. So my work started to fall between the cracks and I think the fact that Shanghai Lady Killer [Swain’s latest creation for Stalker, 2010] became an indoor work has been a part of that process. I just wasn’t finding a way to park the work. Incognita should have had a longer life. It did three of the national Australian festivals, which is about as good as you can get in this country. Then in Europe we couldn’t fit either field any more. We have multi-arts festivals here so we’re used to all kinds of works being in a festival whereas in Europe they’re very artform specific.”

from the body

In 2010 David Clarkson created Mirror/Mirror (2009) for Stalker in collaboration with dancer Dean Walsh (RT94, p36). Before that he’d made Red (2004) and Four Riders (2001) “with an ensemble that I trained, with them taking on my approach to physicality.” Clarkson is currently developing a new work, Encoded, “working with a range of artists, virtual cameras and projection and point cloud generated animation” and wondering, “What is the next phase?” He suspects he’ll direct Encoded but not perform in it—“but it’s my own physicality that still enriches my creative process.” Like Swain’s Shanghai Lady Killer, Clarkson’s Mirror/Mirror also moved indoors.

a choreographic heritage

Rachael Swain appears to be working more and more choreographically, via collaboration with a range of choreographers, as in Incognita (2003) and Shanghai Lady Killer (2010) for Stalker and the Marrugeku creations (MIMI, 1996; Crying Baby, 2001; Burning Daylight, 2006, 2009). The works are large, multi-plane, theatrical, culturally dense. She attributes this in part to the influences of Europe in the 1990s and also of Stalker’s agent since 1991-2, Gie Baguet, as his first international company. Swain says, “Gie’s also the agent for Les Ballets C de la B and he introduced us to their work and other northern European dance theatre companies. The last decade for me has been a big project to bring something of their aesthetics into a dialogue with the kind of raw physicality of Australian dance and Australian new circus techniques. We saw so much work. We were in Amsterdam during the Yulidans international dance festival every year. We saw the evolution of the works of Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker, Wim Vandekeybus, Needcompany, Les Ballets C de la B. And we saw them every year. Australian physical theatre, dance theatre and circus have a really amazing physicality, a lot of which comes from a relationship with the landscape and the physical environment. I wanted to bring this and European aesthetics and processes together. A lot of that work is about a theatrical improvisational process that, as Alain Platel says, “sometimes leads to people dancing.”

That quotation puts me in mind of the work of Pina Bausch. Swain agrees: “Of course that is the lineage. Tim Etchells once said that he thought Forced Entertainment’s work was the end of a line of Chinese whispers that started in Wuppertal [the home of the Pina Bausch company]. And I sometimes think what we’re doing is too. Marrugeku’s Burning Daylight is the result of a very long Chinese whisper that started up in Wuppertal and went to Ghent through the collaboration between me and Koen Augustijnen [of Les Ballets C de la B] for Incognita and Serge Amié Coulibaly [from Burkina Faso; also worked with Les Ballets C de la B] for Burning Daylight and the classes I did over there.

“So I think that’s been the grand project on that front. Yes, I think I conceive and direct work as a choreographer but I really like to partner, most recently with Gavin Webber on Shanghai Lady Killer. Once again, that was about bringing European influenced contemporary dance from Gavin’s time with Wim Vandekeybus, formed through his time with ADT in a kind of loop back into the Australian dance theatre vernacular. I think that’s an ongoing project. And when I’m on the floor I’m working in an improvisational dance theatre process in shaping work.”

Swain is developing Shanghai Lady Killer after its 2010 Brisbane Festival premiere. “It’s a really big work for Stalker. It’s very complicated, an Australian-Chinese martial arts thriller that combines the wire and stunt work used in martial arts films, trampolines on stage, Chinese pole techniques and Wushu which is a particularly lyrical form of Chinese martial arts, in a kind of plot-driven futuristic thriller narrative. This was my first time working with a writer [filmmaker Tony Ayres] which was a great and challenging experience.”

Shanghai Lady Killer

photo courtesy Stalker

Shanghai Lady Killer

Clarkson says he’s captivated by Shanghai Lady Killer despite early reservations about “the commercial narrative structure which I’ve always had problems with because it’s so bloody dominant.” Swain points out that she and Ayres conceived the show before the Global Financial Crisis when “there was a niche appearing for arthouse commercial theatre,” with some opportunities for radical, culturally diverse content. “But the GFC hit and the support that we had for it internationally went. We’d been aiming for a multi-million dollar version, but had to scale way, way, way back down. We were very lucky to be commissioned by the Brisbane and Melbourne Festivals through the Major Festivals Initiative Fund—enormous support and a big project for the fund. I think there is a big national home for Shanghai Lady Killer.”

intergenerational cultural sustainability

I wonder if Swain craves work on a smaller project. “Absolutely!” she replies. “We premiered Buru [Broome, 2010] straight after Shanghai Lady Killer. It’s a much smaller work although it’s still got a fairly large cast. It was devised and created with 10 young performers from Broome aged between 10 and 21—so it’s a very different feel. We worked for three years together with elders from the Broome community, very much in the wake of Burning Daylight, grasping this model as a way to use theatre as a sustainable form of culture, of carrying stories forward—obviously not the [sacred stories] but the ones they really want to pass on, to be public. The elders started to come into rehearsal and to say this is what I think should be happening now. It was a great moment for the company where there was really direct intergenerational knowledge transmission occurring in the rehearsal process and the young performers were really given the work to take forward. So effectively, we’ve established a youth company for Marrugeku. I don’t know if that means a fourth string to our bow now!”

Clarkson is similarly focused on intergenerational connections: “There’s a piece I’m doing called Elevate out at Penrith with three 19-year-olds, a kind of hip hop street stilt piece which is very much about the next generation. I think it’s only appropriate. Theatre is a gift that’s given to you and you pass it on.”

Swain says that “when I came to writing the speech for Stalker’s 21st birthday celebrations, I momentarily found it quite depressing. What is there after 21 years? What is left behind is ephemeral, in the memories of our audiences in all those different contexts, all over the world. And because that’s been so diverse for us and because what Stalker is in Belgium or what Stalker is in Colombia or what Stalker is in Perth, they’re all different, presented in very different models and to different sectors of the community. Twenty-one years of blood, sweat and tears, quite literally…broken bones and all that.

“But there are company members who have been in our work, learned new skills and gone on and done their own work or gone into other companies and contributed to other processes. I certainly hope in Marrugeku’s case that what comes after us will be the measure of the company’s success—finding a language that reflects the Aboriginal elders’ complexity of knowledge but that is also very contemporary. It is very hard to find the comprehension of that work, especially overseas. People often just don’t know what they’re looking at. I hope that we’re opening doors and that further down the track there’ll be more appreciation.”

Stalker have created a significant legacy over 21 very creative years. If the company had fallen apart a decade ago, that legacy might not have been as rich. Swain thinks that “there were times when I’ve thought had we been sane human beings we would have stopped.” Clarkson agrees, “Either financially or personally…but there have been big rewards, tremendous experiences.” And Swain concurs. Happy 21st, Stalker.

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 43,45

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Nest, Hayloft Project

photo Jeff Busby

The Nest, Hayloft Project

IF NIETZSCHE GOT IT RIGHT, AND HUMANS ARE LESS STATIC BEINGS THAN INCONSTANT BECOMINGS, THEN SURELY THE SAME CAN BE SAID OF THE INSTITUTIONS WE CREATE. CERTAINLY, THE MUCH-DISCUSSED “CHANGING OF THE GUARD” IN AUSTRALIA’S MAJOR ARTS ORGANISATIONS HAS MANY THEATRE PUNDITS PONDERING WHETHER THESE COMPANIES WILL BE PUSHED TO REINVENT THEMSELVES AS A RESULT, OR WHETHER IT’LL BE BUSINESS AS USUAL WITH A NEW BRAND IMAGE. LOOKING AT THE SMALLER GROUPS MAKING WORK IN MELBOURNE TODAY, HOWEVER, WHAT’S MORE EVIDENT IS HOW THE NATURE OF SUCH ARTISTIC ENTITIES IS ALWAYS A NEGOTIATION BETWEEN AN ENDURING IDENTITY AND A FIELD OF POSSIBILITY.

the nest

The Hayloft Project has remained one of the most exciting companies in Australia for several years, but focusing on the through-lines that connect each Hayloft production can distract from the impressive imaginative diversity it has also offered. Its final production for 2010 was The Nest, and while the production furthered the company’s interest in classic (especially Russian) texts adapted for a contemporary world, it was also a significant departure from what’s gone before.

Firstly, it saw Artistic Director Simon Stone hand over the reins. While Hayloft productions are almost always helmed by Stone as director, he has also allowed others to create their own works under the company aegis without overt artistic intrusion from its founder. 2009’s Yuri Wells was a hugely successful experiment in this vein, and that show’s creators also form the creative core of The Nest.

Taking as their source Maxim Gorky’s The Philistines, Benedict Hardie and Anne-Louise Sarks have developed a wonderful script that seems utterly of our time. As with Yuri Wells, Sarks again directs and Hardie performs, with a sizeable and accomplished cast making up a strong ensemble. Performed in the round (or, rather, square), Sarks displays a terrific command of pace, shifting quickly from scenes of crowded chaos to tiny, intimate moments of solitude or suspense. Despite the relatively brief running time—around 90 minutes—the sense of an expansive and credible world is quickly established, and something of the sweeping historical consciousness which often infuses Russian playwriting is maintained here.

But where productions of Gorky (or Chekhov for that matter) walk an uneasy line between historical specificity and more universal relevance, how would you know that The Nest hadn’t been written from scratch yesterday if you hadn’t already been told? The only thing that really reminds us of its origins is that oh-so-Russian habit of having countless characters turn up unannounced. Even this slightly anachronistic theatrical convention is knowingly laughed at after the production concludes and the theme songs from various sit-coms are played (sit-coms, of course, being the only place where it’s still acceptable for a constant stream of acquaintances to invade the house at all hours).

I’ve no doubt that in different hands—Stone’s, for instance—The Nest would have been a very different beast. But its inclusion within the Hayloft’s broader output only expands the company’s creative reach, making it home to a multiplicity of voices rather than a single, unitary directive. It’s all the better for it.

Georgina Naidu, Greg Ulfan Yet to Ascertain the Nature of the Crime, Melbourne Workers Theatre

photo Ponch Hawkes

Georgina Naidu, Greg Ulfan Yet to Ascertain the Nature of the Crime, Melbourne Workers Theatre

yet to ascertain the nature of the crime

Melbourne Workers Theatre, conversely, has had many esteemed directors across the decades, but is now undergoing a radical reinvention. Its last production, Yet to Ascertain the Nature of the Crime, hinted at the plans new director Gorkem Acaroglu has for recreating the company as one solely dedicated to documentary theatre, as well as a more general shift away from creating works based primarily around class concerns towards addressing a wider variety of contemporary social issues.

Yet to Ascertain…spoke to this new brief with outstanding clarity, incorporating questions of class and work but also closely scrutinising the realities of race relations in Australia today. It was developed from a range of verbatim sources including interviews, journalistic articles, official reports and first-person narratives. Three performers re-enacted these exchanges in a variety of theatrical styles, from frankly silly Bollywood dances to skit-comedy routines to sincere and moving monologues. Though patchy in tone, the collective weight of the production was considerable, and a lengthy final sequence in which a taxi driver is attacked by racist passengers before his own cab-driving community comes to his rescue is simply breathtaking theatre.

Though largely played in somewhat exaggerated, consciously theatrical ways, the various narratives produced here were of an intricate and provocative nature. Many circled around the experiences of Indian students and immigrants in Melbourne, including the real incidents of racially-motivated violence which have made international headlines as well as more engendered and institutionalised forms of discrimination. There are layers of irony to many of the word-for-word recountings of victims themselves, including denials that Australia is home to racism, as well as the police statements which are the basis for the show’s title. At the same time, contrary viewpoints which complicate the notion of racism as an ‘us vs them’ binary add to the overall challenge—and lack of easy answers—which the show presents to its audience. It’s a pity Yet to Ascertain…had such a short season, but it’s certainly an inspiring beginning for the company’s next stage of development.

The Blue Show, Circus Oz

photo Robert Blackburn

The Blue Show, Circus Oz

the blue show

Circus Oz’s The Blue Show was billed from the outset as something unusual from the company. Housed in its new Spiegeltent, it promised an adults-only show as part of the midsumma festival, but what eventuated was something quite different. Less ‘adult’ in content than context, it was more an ageless celebration of sheer fleshy joy. Many similar Spiegeltent burlesques end up as shop-worn sequences of fairly tame titillation and nudge-nudge cabaret. Here, rather, was nudity and humour with a lack of inhibition that is often only found in children—it wasn’t that the acts set out to transgress social boundaries, but that they didn’t seem to even admit of their existence. Sure, there’s appeal in a show that allows us to enjoy a drink in intimate surrounds without toddlers scampering underfoot, but very much the same show could have played to all ages at an earlier timeslot without risking much outrage.

For me, the company’s regular higher profile family outings have long been hampered by “kid-friendly” clowning that doesn’t evince the same sophistication as some of the more intricate routines; the performers are all top-notch, but their talents can come across as dumbed-down when they don’t need to be. The Blue Show treats its audience as adults, as capable of viewing on a range of levels, but it also seems to me that many kids are just as able to handle this kind of subtle complexity. It’s encouraging to see the company branch off in this direction, and one can only hope that some of the acuity and focus displayed here will develop in the company’s more popular ventures in the future.

The Hayloft Project, The Nest, writers Benedict Hardie, Anne-Louise Sarks, after Maxim Gorky’s The Philistines, director Anne-Louise Sarks, performers Sarah Armanious, Stuart Bowden, Stefan Bramble, Alexander England, Brigid Gallacher, Julia Grace, Benedict Hardie, Carl Nilsson-Polias, Meredith Penman, James Wardlaw, set Claude Marcos, costumes Mel Page, lighting Lisa Mibus, music & sound design Russell Goldsmith, Northcote Town Hall, December 4–19, 2010; Melbourne Workers Theatre, Yet to Ascertain the Nature of the Crime, writer Roanna Gonsalves with Raimondo Cortese, Damien Miller, director Gorkem Acaroglu, performers Georgina Naidu, Greg Ulfan, Andreas Littras, performance consultant John Bolton, sound design by Mik La Vage, lighting Jason Lehane; Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall, Nov 24-28, 2010; Circus Oz, The Blue Show, director Anni Davey, Circus Oz Melba Spiegeltent, Jan 13-Feb 6, 2011

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 44

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Natalie Rose, Zoe Coombs Marr, Mish Grigor, Everything I Know About the Global Financial Crisis in One Hour, Post

photo Heidrun Löhr

Natalie Rose, Zoe Coombs Marr, Mish Grigor, Everything I Know About the Global Financial Crisis in One Hour, Post

IN A DELIRIUM OF RIGHTEOUS FREE MARKET FUNDAMENTALISM, WESTERN CAPITALISM, ONSELLING UNSUPPORTABLE LOANS THE WORLD OVER, WENT MAD. SOME OBSERVERS RECOGNISED THE SIGNS OF INSANITY AND FORESAW IMMINENT COLLAPSE, THE REST OF US SUFFERED THE DELIRIUM OF THE AFTERSHOCKS AS STATE ECONOMIES, JOBS AND HOUSING MARKETS WERE SUCKED INTO A HELLISH BLACK HOLE.

Even if you didn’t feel the impact of the Global Financial Collapse in the pocket (a welcome $900 cheque from Prime Minister Rudd aside) you doubtless spent time anxiously wondering what had actually happened and would it recur in the shape of a much anticipated vicious double dip recession.

Nervous times yielded countless articles, broadcasts and books providing analyses simple and complex of the Global Finance Collapse. Some have been reassuring—providing a clear chain of cause and effect running from bad economic theory to market deregulation to failed governance and downright corruption. Others have revealed more worrying networks of disturbance, from unrelated one-off criminal acts (Bernie Madoff, a handy villain) to globalisation’s maximisation of the GFC’s impact, from American Republican and Australian Liberal politicians arguing for brutal economic clean-slating instead of stimulus packages to Detroit’s motor industry tsars driving cars to Washington’s Senate Enquiry and all of us having to grasp the reality that the USA was in substantial debt to China. The world had truly turned upside-down.

How can art assist in a time of paranoia and breathtaking absolutism? Belvoir’s B Sharp, in one of its last acts, brought relief and enlightenment in the form of A Distressing Scenario, a double bill from Sydney performance companies Post and version 1.0.

Of the two performances, Post’s Everything I Know About the Global Financial Crisis in One Hour, more effectively conveyed the aforementioned sense of delirium with a virtuosic stringing together of unlikely causes and effects, the semi-lecture format reinforced with bizarre chalkboarding (the board itself revealing ever new extensions) and interrupted with manic dancing, the waving of sparklers and the positioning of champagne bottles in readiness for the ultimate release.

The experience was like having the GFC explained to us by the ill-read, the ill-informed and the plain ill—the bandaged performers presented variously as victims of car accident, tonsilitis, cocaine addiction and pregnancy, all impediments to putting their show together. Undaunted, the Post trio launched into an elaborate and diffuse explanation of the GFC replete with muddled and inaccurate historical grabs and bizarre connections altogether reminiscent of paranoid popular media. An exhausting whirligig of associations dated GFC origins back to Rockefeller, the corn market, popcorn and the decline of the cinema, the 1988 Australian Bicentennial and Bette Midler tours as positive market indicators. These were accompanied by wild speculations about the value of training monkeys in universities and why there are no jaws of death for newsagents. The sheer, manic drive of the performance, its bracing informality, the self-belief, its mad poetry and smatterings of GFC-reality sucked an initially wary audience into a vortex of nigh impossibly suspended disbelief.

Everything I Know…was durational in every sense, for the courageous performers, sometimes perilously over-taxed, and for an audience riding the wild waves of free association, coursing the looping illogic and withstanding the recurrent, battering dance passages and the final champagne spray. With wicked ease, but little to celebrate as bankers and brokers clawed back their bonuses, Post left us nonetheless wiser about the way the human brain miscalculates and rationalises its way into disasters of the order of the GFC.

After the brief respite of intermission and anticipating further assault, we were bemused to find ourselves removed from Post’s compulsive cosmos and relocated to the parallel universe of version 1.0’s The Market is Not Functioning Properly. Same Big Bang—the GFC; same problems—how to comprehend and survive economic disaster; similar symptoms—faltering rationality and increasing delirium. The Market’s performers also, like Post, reveal themselves to be performers (“I’m an artist: no finances to speak of,” declares one).

But the Post and version 1.0 universes travel in opposite directions. Instead of the desperate, gutsy vigour of Everything I Know, The Market is neat, tautly framed, carefully paced. Two genteel women (Jane Phegan, Kim Vercoe) in pearls and satin gowns appear to parody themselves and then, more archly, middle-class womanhood as they grapple with the GFC and their domestic budgets (laid out on laminated cards that threaten to slip from their grasp). If Post are wildly mock educational, version 1.0 are calculatedly didactic. The women puzzle and bicker informatively beneath three screens inhabited by unreassuring world leaders, all men, alternating with three Australians, also men, with very little to say about the GFC.

As finances and life become less manageable (cut back on wine, on Belvoir tickets), the women strike poses of fright before the images of these men (the powerful and the ‘ordinary’ at times superimposed), dance awkwardly, swing together in violent circles, teeter on the edge of the raised stage and, finally, spew champagne into buckets hanging immediately before us. But they might as well have gone to pieces on another planet from our own. We could recognise the symptoms of their GFC-induced malaise but where was the rich, cranky substance of appalling cause and effect that we have come to associate with version 1.0? The Market was a surprisingly tame affair for a company whose major works have surreally and satirically brought to light the frightening deployment of power in politics, media and gender relations—revealing that the irrationalities and manipulation involved don’t have to be exaggerated, but reframed in order to be seen. Version 1.0 have set their benchmark very high and we expect a lot, not least the means with which to do battle with the insidious GFC.

–

B Sharp, A Distressing Scenario: Post, Everything I Know About the Global Financial Crisis in One Hour, deviser-performers Zoe Coombs Marr, Mish Grigor, Natalie Rose; version 1.0, The Market is Not Functioning Properly, deviser-performers Jane Phegan, Kym Vercoe, director David Williams, video artist Sean Bacon, sound Paul Prestipino, lighting Frank Mainoo; Belvoir St Theatre, Sydney, Nov 25-Dec 19

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 45

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ralph Myers

photo Patrick Boland

Ralph Myers

IN REALTIME 100, I GREETED THE 2011 BELVOIR PROGRAM WITH ENTHUSIASM. NEW ARTISTIC DIRECTOR RALPH MYERS’ LARGELY YOUNG TEAM OF DIRECTORS (INCLUDING SEVERAL WOMEN), A MIX OF RARELY SEEN CLASSICS (INCLUDING RAY LAWLER’S SUMMER OF THE SEVENTEENTH DOLL TO BE DIRECTED BY OUTGOING ARTISTIC DIRECTOR NEIL ARMFIELD), NEW PLAYS, A DANCE PIECE AND TWO ABORIGINAL WORKS COMPRISE A SERIOUSLY INVITING PROGRAM. IN ADDITION, THE INCORPORATION OF THE DOWNSTAIRS THEATRE INTO THE OVERALL PROGRAM SEEMS A SIGNIFICANT OPPORTUNITY TO PHILOSOPHICALLY AND PRACTICALLY EXPAND BELVOIR’S PROGRAM AND REACH.

MYERS, IN OUR FIRST MEETING, CONFIRMS HIS REPUTATION AS AMIABLE, FUNNY AND SHARP. HE’S AN ACCLAIMED THEATRE DESIGNER, NOT A STAGE DIRECTOR [AS YET], SO I THOUGHT IT MIGHT BE INTERESTING TO USE THAT AS THE PIVOT FOR OUR CONVERSATION.

You trained in visual arts, specifically in silversmithing, but then you went to NIDA.

I’m a bit impatient and hasty to see a quick result which is why I thought I might not make a good jeweller. And there’s something great about theatre design and indeed the process of making theatre in general. It’s something that happens quite quickly, you get a big result quite quickly and it’s all kind of slightly junky, which I think appeals to my kind of sensibility.

The materials, the disposability?

It’s ephemeral—you only need to make it last for a season while achieving the impression and the sensation that you’re trying to generate in the mind of an audience. Jewellery making—and I’m touching my wedding ring as I say this—is about the integrity of the material. How many carats is the gold, how well is it constructed, how many hundreds of years is it going to last? What I like about theatre is the exact opposite of that.

In theatre, it’s the durability of memory, isn’t it?

It is and that’s a strangely fugitive thing as well. Memories twist and transform. Neil’s wonderful production of Diary of a Madman makes quite an interesting comparison between what theatre was like 20 years ago in Sydney and now. He’s pretty faithfully reproduced that 1989 production with Geoffrey Rush and the original team, the original designers. It’s marvellous that even though it’s not that old, it’s stylistically from another era.

There are times when you have to live with your designs a lot longer than a Sydney season. A Streetcar Named Desire going to the US must have posed interesting challenges.

It’s a slightly horrible thing to say, but the ones that have the longest lives are not always the ones you want to. The curious thing about being a set designer is that ultimately you need to serve the vision of the director. So sometimes you have to make a decision to put your taste and your sensibilities—and your fears—aside and allow the director to ultimately make the decision.

You were serving Liv Ullman’s vision.

Absolutely. And she is an extraordinary figure, an important artist of the 20th century. Who am I to tell her what to do? I’m working on Ibsen’s The Wild Duck at the moment both as set designer and as artistic director of the company. We’re finding a way for that to work. And it does work because Simon Stone the director is very clear about his ideas and vision. So it’s not muddy.

There are a number of strong directors around who could be labelled auteurs, who arrive not just with a play but also a design concept for the designer to realise rather than invent.

You get directors who know exactly what they want and the task is making that work within the space and the parameters. And there are always an infinite number of details to resolve. I don’t mind that. I’ve been in situations for instance with Benedict [Andrews] where he’s led the process very much—I’ve realised an idea that’s come to me from him very much fully formed. On the other hand there have been other situations where the idea has been largely mine and it’s evolved in conversation. Barrie Kosky is another example. He has very strong ideas about what he wants. To be honest I find that the better directors know precisely what they want or latch onto an idea and allow it to be followed through to its logical conclusion. When I was working with Neil Armfield on Benjamin Britten’s opera Peter Grimes for Opera Australia, I’m fairly sure Neil came up with the idea of setting it in a church hall. I built a model of it and very quickly we realised that it would work. Then he allowed me to realise that very much on my own. So there’s quite an element of trust and understanding.

Your father was an architect, your mother a visual arts teacher; I’m very interested in the architectural quality of your work. It seems to me that some designers have a better architectural and spatial sense than others (whose work might resonate, say, with contemporary visual arts or technology or interior design). In certain of the shows you’ve designed the architectural quality is pronounced—those huge floating rooms in The Lost Echo (STC) or the room that revolves in Measure for Measure (Company B), that modernist superstructure hanging over a very ordinary, aged apartment in Streetcar Named Desire (STC), the grim in-the-round basement world for Blackbird (STC), the hall in Peter Grimes. They all struck me as very three-dimensional, very substantial. For all that ephemerality, they felt eerily solid.

I’m interested in solid things. My mother was an architect before I was born. I’ve always been around architects. I suppose if you come from a family of tailors, you look at what people wear. I am interested in people and space. I’m flattered that you think my work seems solid. The thing you’re fighting in theatre is that nothing is solid really. It’s all made out of bits of cardboard.

How do you feel about The Wild Duck? Do you engage with the actors and the director about the way the space is being used and inhabited?

I try to attend rehearsals as much as I can. I really like being in rehearsals. And of course the more you’re there the better the design serves the purposes of the play. I’d like to be there all the time but you can’t always be. In all good rehearsal rooms, there’s a certain amount of cross-fertilisation. Actors will suggest something about the set and you can suggest something about how they do their performance (LAUGHS). In the end it all comes out in the wash.

One of the tricks of being a good designer is to maintain as much flexibility as you can within the structures of how companies like this will work. All theatre and opera companies and certainly production departments will try to lock down the physical elements of production as early as they can because it makes it very much easier for them to do their job. One of the difficult things to say after the second preview might be: “Actually, it should all be pink” or “I think this is completely wrong. Let’s get rid of the set and do it on an empty stage” or “I think she should be wearing a wedding dress.” These things throw a spanner in the works, blow the budget and make it very difficult. But ultimately that’s what you might need to do: use the time at your disposal to make the production as good as you possibly can. Sometimes you can’t have the best idea three months in advance of the production or, in the case of opera, 18 months.

One of the things I’m conscious of as artistic director of this company is allowing it to remain pretty responsive, which it always has been. As a set designer this was the one place where you really could change your mind quite late which is a really fabulous thing. I think this probably comes from Neil’s chronic inability to make artistic decisions (LAUGHS). He’s left a great legacy for the rest of us.

For Measure for Measure you were working with projections and onstage cameras. You’ve made it clear elsewhere that you see theatre as a very different realm from film and new media—that’s not to say you’d exclude them. But that work provided a fascinating experience in terms of design, accommodating the revolving room that keeps transforming and the screens that frame it.

I’m often extremely sceptical about the use of audio-visual material in theatre productions because I think it can be a substitute for something that could be shown in real time or ‘real life.’ The figure on the screen is often much more interesting to watch than the onstage figure, because of scale. So your eye tends to be drawn there which starts to beg the question well why is there a figure there at all onstage? As you know, Benedict’s extremely interested in working in that way. As the designer for Measure for Measure of course I went along with it, made it work as best I could within the space, worked with Sean Bacon and in the end I think it was extraordinary. You gain something, of course, by the use of the camera to show a kind of detail that otherwise couldn’t be seen. That’s much more interesting than showing what you can already see. So Benedict’s focus on Mariana’s wedding—you know touching her engagement ring at the top of Act 3—or zooming in as he did in The Season at Sarsaparilla on a detail or moment that would otherwise be lost to the audience, is extremely interesting. It’s an interesting extension of that idea.

I suppose there’s not much you can reveal about your design for The Wild Duck at this stage. What would you say is the creative impulse for you in the production?

It’s extremely exciting. I don’t want to jinx it by saying it’s going to be good but Simon has a very sharp brain and a very good sense of what’s at his disposal in terms of the actors and the resources that are available to him after coming from a background in independent theatre where everything is slightly difficult to get hold of. Here things are more possible. That said, it’s quite a restrained production, not over the top in any way. He’s essentially taken the core story of The Wild Duck, those six central characters, the inevitable playing out of an action over a short period of time that happens in Ibsen plays, and stripped it of all the stuff around it, rewritten it and placed it in a very spare environment.

It all happens in one space?

It’s even more abstract than that somehow. It’s really no space at all. The adaptation has a kind of charm that’s often missing from the adaptation of classics—a kind of lightness, playfulness and charm that’s very easy to lose when you’re trying to faithfully adapt something. It’s a bit like—while being nothing like—Noel Coward or Oscar Wilde in that the way that people interact with each other doesn’t always reflect the great drama and import of the things that are being discussed. I don’t know how Simon manages to create that. He’s got a very playful rehearsal room. There’s a great deal of light. But it’s a horrific play. A 14-year-old girl in the end shoots herself.

Obviously like many before you, you’re enamoured of the Belvoir St Theatre space, and you’ve worked it before. Will you occasionally lease yourself out to bigger stages?

I’m working on a production for Opera Australia in 2012. That’s the only thing I’m doing outside at the moment. I’m designing for Benedict’s production of Chekhov’s The Seagull for our 2011 program.

What have been the pleasures of putting this program together for you?

It’s an enormous pleasure listening to a whole lot of people speak very passionately and enthusiastically about the things they want to do. The difficulty, of course, is choosing which ones to take up. A company like this should be as open as it can be, as able to hear as many ideas from as broad a range of places as possible. One of the challenges for a company is that you can become insular or that you only turn to people you know or who you’ve worked with before, which I think is extremely dangerous. The other side of that is that you have to listen to a whole lot of bad ideas from a whole lot of people too. But that’s okay. So that’s a great pleasure. And then you make a salad out of it. And there are a lot of reasons why some things end up in the mix and others don’t but really nothing ends up in there that I don’t think is going to be good or interesting or hopefully both. I very much started the process with the ambition to not include anything simply for pragmatic reasons.

Like making big box office?

Yes and you never can anyway. From a few years of working at the Sydney Theatre Company and from many years around the traps working as a designer in lots of theatre companies, you see that there are things that a company does for legitimate and artistic reasons and there are other things they do to satisfy what they imagine the audience wants or what’s going to make money, all sorts of reasons. My one ambition is to not have one of those productions. We’re lucky we can do that here. We don’t have quite the pressures of the big state companies. It’s an enviable position. The trade-off for winding up the B Sharp program was that we were going to be able to do fully staged productions down there. The disadvantage was that we wouldn’t be able to do so many of them. My ambition is to build that up over time so that it has the same volume and energy that B Sharp had but where everybody is being paid. My big ambition is to employ more artists in general. It’s surprising how few people think that’s a good idea [LAUGHS]. But I think it’s critical for a city of this size, a city as fabulous as Sydney to have a lush and thriving artistic community. And I think you have to do that by directing money towards people to do it. We’re the third or fourth biggest theatre company in the country. I think we need to face that reality.

Henrik Ibsen’s The Wild Duck, directed by Simon Stone, featuring performers John Gaden, Anita Hegh, Ewen Leslie, Eloise Mignon, Anthony Phelan, Toby Schmitz and designer Ralph Myers is playing at Belvoir Street Theatre, Feb 12-March 27; Belvoir, artistic director Ralph Myers, Sydney; www.belvoir.com.au

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 46-47

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

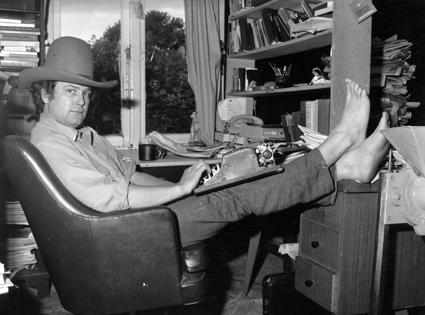

Frank Moorhouse (archival)

photo courtesy of ABC Document Archives

Frank Moorhouse (archival)

HERE’S AN INSPIRED IDEA: NOT ONLY PLAY A SERIES OF EIGHT CLASSIC AUSTRALIAN STAGE AND RADIO PLAYS PRODUCED BY THE ABC OVER THE DECADES BUT ALSO INTRODUCE EACH WITH CAREFULLY AND INVENTIVELY CRAFTED 30-MINUTE INTRODUCTIONS FROM WRITERS (WHERE AVAILABLE), PRODUCERS, ACTORS AND SPECIALIST COMMENTATORS FLESHING OUT THE SOCIAL, POLITICAL AND AESTHETIC WORLDS AND CREATIVE IMPULSES FROM WHICH THE WORKS EMERGED. PLAYING THE 20TH CENTURY REALISES THE VISION WITH VERVE.

The series is a collaboration between ABC Radio National’s Hindsight and Airplay programs aiming to “chart a century of Australian theatre” from Louis Esson’s The Time Is Not Yet Ripe (1912) to Katherine Thompson’s Diving for Pearls (which won the Louis Esson Prize for Drama in 1991!). The other plays are Betty Roland’s The Touch of Silk, Douglas Stewart’s radio verse play Fire on the Snow, Ray Lawler’s Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, Alex Buzo’s Norm and Ahmed, David Williamson’s The Removalists and Frank Moorhouse’s experimental radio drama Loss of a Friend by Cablegram.

Of the three introductions I’ve listened to so far, it was the world conjured by the reflections of Moorhouse, McLennan and actor Arthur Dignam on Loss of a Friend by Cablegram that I found the most engrossing. The commentaries on The Time Is Not Yet Ripe from academics John McCallum and PJ Matthews were richly informative but the voice given Esson (from his letters) was not engaging and the documentary’s structure is the least inventive of the three. The introduction to Diving for Pearls however is full of the sounds of its Port Kembla steelworks and coastal setting and there is clever segueing from playwright Thompson’s voice into those of her characters along with astute observations from the play’s first stage director Ros Horin and Di Kelly from the University of Wollongong on the political context.

The appeal of the introduction to Loss of a Friend by Cablegram for me lies in its embodiment of a period of transition in radio drama production in the early 1980s from the imitation of the live theatre experience on air to more intimate approaches, from single take recordings on tape (often subsequently destroyed) to intensively edited productions, from crude FX to field recordings (the right acoustic) and from predictable structures to experiments in form. McLennan, who produced the play, details these transitions with amusement against the sounds of tapes running and creaky old FX. Again there’s a brisk alternation between the documentary voices and the original recording which was made with Dignam and Robyn Nevin in a room in the Sebel Town House in Kings Cross with verite intimacy and a lovely depth of field. Typical of the period of transition the sense of experiment that comes with Moorhouse’s writing is undercut by stilted, hyper-articulated stage delivery. Even so there’s much to amuse and even disturb in the production as a man and his estranged wife deal with his bisexuality, not least when she asks, “Did you think you were a woman when you lived with me, when we were married?”

There’s much to enjoy from Moorhouse about writing, about notebooks (which provide the play’s structure), about bisexuality, and from Dignam about working in radio (“When I started to learn how to drink”—as the actors headed off to a Push pub after recording for, as Moorhouse puts it, “critical drinking”) and the pleasant experience of being involved in a new way of working. Even so McLennan is surprised that most of Loss of a Friend by Cablegram was largely recorded in real time, in the traditional manner, even Dignam’s character’s inner thoughts—achieved by the actor simply turning to another microphone. Producer Catherine Gough-Brady’s introduction to the play offers insights about the writer, the work and an era of transition—sexual and aesthetic—telling us much about radio as well as the Australian play.

ABC Radio National, Airplay and Hindsight, Playing the 20th Century, producers Catherine Gough-Brady, Regina Botros, presenter Andrew McLennan, broadcast Dec 19, 2010-Feb 6, 2011; the series can be heard at www.abc.net.au/rn/playingthe20thcentury/

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 47

Mike McEvoy, Ida Duelund Hansen, Another Lament

photo Paul Dunn

Mike McEvoy, Ida Duelund Hansen, Another Lament

TARGET, THE ITCH AND ANOTHER LAMENT ARE THE WILD PROGENY OF CHAMBER MADE OPERA’S 2010 LIVING ROOM OPERA SERIES, AN INNOVATIVE APPROACH TO FUNDING NEW WORKS ENCOMPASSING PRIVATE PATRONAGE, GOVERNMENT SUBSIDY AND CROWDFUNDING. A HOST PROVIDES THEIR LIVING ROOM AS THE PERFORMANCE SPACE, WHILE BOOKING ONE OF THE LIMITED SEATS (IF YOU’RE LUCKY YOU’LL ACTUALLY GET THE SOFA) COMES WITH RECOGNITION AS A CO-COMMISSIONER, FOOD, WINE AND THE OPPORTUNITY TO DISCUSS THE WORK WITH THE COMPOSER AND FELLOW AUDIENCE-PATRONS.

While the Living Room Opera series has precedents in salon performance traditions, its particular combination of funding and social strategies gives hosts, audiences, composers and performers a unique sense of ownership, opening up the possibilities for original and inspired creations.

Luke Paulding’s Target re-imagines the Ancient Greek myth of Ganymede, the most beautiful of mortals abducted by Zeus to serve as cup bearer to the gods; Alex Garsden’s The Itch musically embellishes an article from The New Yorker in 2008 about a woman who awoke one morning with an chronic itch on her head (RT100, p40); and Another Lament (a collaboration between double bassist and singer Ida Duelund Hansen, from the mixed-ability performance ensemble Rawcus, and sound designer Jethro Woodward) explores the death of the English baroque composer Henry Purcell. The young composers’ musical styles are as varied as their subjects, from the bleeding edge of extended string techniques to jazz-inflected baroque arias.

“I did not especially set out to work with young composers,” claims Artistic Director David Young, “the works speak for themselves.” As many composers struggle to find funding once they grow out of the youth bracket of government grants, the Living Room Opera series provides a valuable lesson in alternative sources of funding for its participants.

target

Performed in “Melbourne’s living room,” La Mama, the work in progress Target showcases Paulding’s distinctive timbral vocabulary in exploration of the dynamics of sexual desire and fear in ancient and contemporary worlds. Through saccades between episodes of delicate wind, percussion and vocal extended techniques, Target’s enchantingly transparent sonic palette evokes a world of short attention span pleasure as Zeus (baritone Matthew Thomas) towers over Ganymede (boy soprano Jordan Janssen) in the cramped La Mama theatre. Flute and tuba breath tones flicker at the periphery of hearing until the terrifying and terrified power of Zeus’ voice is brought down upon Ganymede at the moment of his abduction. Ganymede interrupts the peripheral hum not with screams but with silence, the boy’s twittering interrupted by the glottal stops of trauma.

The audience was intimately close to the ensemble in La Mama’s black box, ensuring that none of the subtlety of Paulding’s composition was lost. After the performance, the audience had the opportunity to ask questions of the composer and hear key sections of the opera again. As David Young explains, the Living Room Opera concept takes its cue from the 19th century tradition of salon performances, where virtuosi would bash out the latest works by Liszt and gentlemen would show off their fine baritone in an intimate, semi-private setting. Beyond a small-scale format for the development of new grand works, Young sees the salon format as serving a pedagogical purpose. Warning that “this is not just a nostalgic experiment,” Young wants audiences to “learn more by having a close experience and speaking with the artists after the show.”

The didactic ending to Target evoked not only salon performances but also Schoenberg’s Society for Private Musical Performances of 1918–21. Formed for the development of musical understanding, the well-rehearsed works were repeated as many as six times during a single program. Unlike at the strictly pedagogical performances of Schoenberg’s Society, there was no shortage of applause at the conclusion of Target, which is set to become a fully-fledged Living Room Opera later this year.

the itch

With Alex Garsden’s The Itch, the Living Room Opera series moved in to full swing. Fiona Sweet and Paul Newcombe’s open plan living space filled with interested patrons quaffing wine while the performers loitered outside a set of french doors. Although Garsden’s masterful representation of skin irritation on string instruments was hard on even the most seasoned ears and despite the occasional twitch, cough or scratch of discomfort, the audience sat in rapt attention to Garsden’s score and soprano Carolyn Connors’ pained vocalisations. This was not an audience looking for a pleasant night’s entertainment, but one intent on supporting new music.

Offering the perks of being recognised as co-commissioner of the work, speaking with composer and performers, and sharing the performance in an intimate setting with like-minded aficionados, events like The Itch resemble Kickstarter and Fundbreak crowdfunding campaigns, where fans sponsor small-scale cultural projects. They are rewarded, depending on the size of their donation, with things like back catalogue CDs and visits to the recording studio of the supported artist. (Since Kickstarter campaigns rarely gather donations from outside the campaigner’s circle of friends of friends, it might be more correct to say that crowdfunding campaigns resemble an intimate living room gathering of a network of interested persons more than the decentralised and anonymous peer group that the “crowdfunding” appellage suggests.)

another lament

Another Lament takes as its inspiration the death of English baroque composer Henry Purcell. So the colourful version of the story goes, Purcell succumbed to pneumonia after his wife locked him out in the snow when he returned from a long night of carousing at the local theatre. Hosts Deidre and Naham Warhaft’s hallway and twin living spaces, separated by screen doors, provide a double proscenium arch for Rawcus director Kate Sulan’s immaculately choreographed tableaux vivants. Sulan uses the house’s depth and wings to conceal the Rawcus ensemble and lighting by Richard Vabre, haunting the tripartite stage with apparitions so carefully placed as to seem to have always inhabited the space. Even in moments of frenzied activity, when plates are broken and Purcell begs at the front door, the audience seems to be haunting a haunting quite indifferent to their presence.