Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Vernon Ah Kee, Ideas of Barak 2011 Brisbane, Queensland charcoal on canvas, video installation, Felton Bequest 2011

THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF VICTORIA MARKED ITS 150TH BIRTHDAY IN MAY. IN ADDITION TO THE OCCASION’S DOMINANT NARRATIVE CELEBRATING AUSTRALIA’S OLDEST PUBLIC ART GALLERY, THE NGV ALSO USED ITS MILESTONE TO ENGAGE WITH AND FACILITATE BROADER REMEMBRANCE OF ONE OF VICTORIA’S MOST IMPORTANT ARTISTIC AND HISTORICAL FIGURES—WILLIAM BARAK. THROUGH A SERIES OF COMMISSIONS AT NGV’S IAN POTTER CENTRE, THE LIFE AND LEGACY OF THE WURUNDJERI LEADER HAS BEEN PROMINENTLY RE-PRESENTED AND RE-IMAGINED.

Barak’s life (c1824-1903) encompassed a period of intense change and trauma for his people. As a boy he was present at the signing of the 1835 Treaty between members of the Kulin people and John Batman, and as ngurungaeta (clan leader), Barak was a skilled diplomat and politician. He would famously walk from Coranderrk (near Healesville) to Melbourne to negotiate and fight for the rights and living conditions of his people—devastated and immeasurably changed after Batman’s treaty (see Bruce Pascoe, How It Starts, First Australians, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2008). His legacy as an artist is also vitally important; towards the end of his life Barak produced a number of intricate works on paper that documented the traditions of the Wurundjeri people, ensuring that knowledge of this culture would be preserved and continued for future generations.

Despite the influence and impressive reputation of this Aboriginal leader, the cultural memory of Barak amongst Melbournians and Victorians remains limited. I first learnt about him at the NGV seeing his paintings on display in the Indigenous Galleries. Three new commissions on display by contemporary artists Vernon Ah Kee, Brook Andrew and Jonathan Jones represent an important opportunity to further ingrain the name and story of Barak into the national consciousness and cultural memory.

Brook Andrew, born Australia 1970, Marks and Witness: A Lined Crossing in Tribute to William Barak, 2011 Melbourne, Victoria

vinyl wall drawing, neon

Felton Bequest 2011

image courtesy of the artist and NGV Australia

Brook Andrew, born Australia 1970, Marks and Witness: A Lined Crossing in Tribute to William Barak, 2011 Melbourne, Victoria

vinyl wall drawing, neon

Felton Bequest 2011

brook andrew

Brook Andrew’s commission Marks and Witness: A Lined Crossing in Tribute to William Barak is a site-specific work installed in the Ian Potter Centre’s atrium. The recurrent Wiradjuri designs and neon stretch up multiple levels, offering an overwhelming and dizzying entrance to a space which is already monumental in its architecture. Like previous works such as Jumping Castle War Memorial (2010), there is an ironic tension in Andrew’s commission. Contrasting the connotations of formality and permanence in the memorialising process with an ironic and playful interpretation, it eschews the representational mode, offering instead an immersive and experiential form of memorial. It also possesses a sense of the ephemeral, a spectacle that may not be on display indefinitely, thus drawing attention to the relative lack of formal and prominent sites of remembrance dedicated to Indigenous histories and heroes.

Jonathan Jones, Untitled (muyan)

2011 Sydney, New South Wales

light emitting diodes (LEDs), glass, aluminum

Felton Bequest 2011

jonathan jones

While some historical narratives emphasise the individualistic nature of heroism, Barak’s legacy as leader and artist is fundamentally entwined with the culture of his community. Joy Murphy Wandin, a senior Wurundjeri woman and descendent of Barak, explains the role of the ngurungaeta as those who “take on the responsibility for the entire community” (cited in Pascoe). Thus Barak’s paintings of Wurundjeri ceremonies are not just works by an individual artist, they also reveal the communal practices and celebrations of his people and Jonathan Jones’ commission Untitled (muyan) is inspired by and suggestive of this tradition.

Jones’ piece is composed of five LED illuminated glass light-boxes installed in a large stairwell of the gallery. Arranged into two groupings, it symbolises the two fires seen in Barak’s paintings, one for the Wurundjeri and another for visitors and guests. The white LED lights of the installation will annually turn yellow in August, signifying the blooming of the muyan (wattle), the time of year that Barak had predicted for his own death. Imbuing his piece with this temporality, Jones evokes a subtle sense of ritual and offers a visual cue to viewers, a possible catalyst for further visits and commemoration.

vernon ah kee

When presenting and documenting history, modes of representation and sources of information—history books, museum exhibits, documentary films—are generally positioned through the lens of authority and expertise. Vernon Ah Kee’s work Ideas of Barak is perhaps the most dense of the three commissions in terms of the level of historical information and context provided, however it resists didacticism by acknowledging the complexities and contradictions inherent in historical representation.

The piece consists of three components: a charcoal portrait of William Barak; a single channel video of the artist exploring and discussing Barak’s life and country; and a five channel video featuring a variety of individuals speaking about their personal ideas of Barak. Rather than offering a singular narrative, Ideas of Barak is constructed around fragments, impressions, imaginings, contradictions, musings, opinions and convergences. Some of the individuals acknowledge not knowing a great deal about Barak’s life—they are neither historians nor experts—yet each makes a personal and present-day connection with this figure. The artwork acknowledges that individuals do not need an encyclopaedic knowledge of history in order to be moved by its narratives and figures, and to play a role in their remembrance. While history might attempt to create linear narratives, memory often encompasses the fragments, fantasies and imaginations of individuals and cultures.

beyond the gallery

Last year, property developers Grocon announced plans to build an apartment building featuring a 32-storey portrait of Barak on its façade (see the plans and an article from The Age), meaning that Melbourne may well find itself with a prominent and permanent public memorial to this Aboriginal hero. However, we must not assume that any single act of remembrance, no matter how visible, marks an end to the memory-work. Cultural memory is an ever shifting and evolving realm, and the NGV’s commissions will hopefully be but one level of an ongoing, multi-layered dialogue that continues to foreground the legacy of William Barak in the consciousness of the Australian public.

The Barak Commissions: Brook Andrew, Marks and Witness: A Lined Crossing in Tribute to William Barak; Jonathan Jones, Untitled (muyan); Vernon Ah Kee, Ideas of Barak; The Ian Potter Centre, NGV Australia, www.ngv.vic.gov.au

This article first appeared in the June 28 e-dition.

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. web

© Kate Warren; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Mish Grigor, Zoe Coombs Marr, Eden Falk, Who’s the Best?

photo Heidrun Lohr

Mish Grigor, Zoe Coombs Marr, Eden Falk, Who’s the Best?

who’s the best?—post is

You’ve only got until July 2 to be seduced and wowed by Post’s infectiously delirious Who’s the Best?, commissioned by Sydney Theatre Company’s Wharf 2 Next Stages program. Once again Post raise daggy amateurism to a sublime artform—and with more professional verve than ever (see the review of Everything I Know About the Global Financial Crisis in One Hour in RT101). This experiment to determine which of the three collaborators and friends is the best performer employs a range of tests from psychological profiling to assessing who’s the ‘hottest.’ These are constantly complicated or sidetracked by hilariously mind bending battles of the Abbot and Costello “Who’s on first” variety over the semantics of category labels and terminology. They’re adroitly woven through the script, recurring as running gags and providing an immersive pulse to the work. The performers’ casual delivery (always played directly to the audience while they freely insult each other) yields intimacy and immediacy on a stage which wickedly threatens to subvert the show as curtains and lighting go about their own business regardless. Trio member and co-devisor Natalie Rose, who has recently had a child, is replaced for the premiere season by a wigged Eden Falk who slips easily into the Post mode while bringing his own wide-eyed comic innocence to Who’s the Best? alongside Mish Grigor and Zoe Coombs Marr. Post, Who’s the Best?, Wharf 2, Sydney Theatre Company, Next stage 2011, June 17-July 2, www.sydneytheatre.com.au

Elma Kris, Waangenga Blanco, Daniel Riley McKinley, Belong

photo Jason Capobianco

Elma Kris, Waangenga Blanco, Daniel Riley McKinley, Belong

new works in naidoc week

Next week is NAIDOC week and there are two exciting premieres to look forward to. In Sydney, the PACT Centre for Emerging Artists is presenting Bully Beef Stew, its first ever fully professional commission. Coming out of its Incubate initiative, a performance laboratory for emerging Indigenous artists, Bully Beef Stew features three young Aboriginal men—Sonny Dallas Law, Colin Kinchela and Bjorn Stewart—working with director Andrea James (former artistic director of Melbourne Workers Theatre) and choreographer Kirk Page. Billed as a “fearless theatrical exploration of Aboriginal manhood,” the piece draws on the personal experiences of the performers as well as their fathers and other men in their lives, past and present (press release).

Further north, Stephen and David Page will be premiering ID as part of Bangarra Dance Theatre’s double bill Belong. (Check out the Stephen Page archive in RealTimeDance.) This new work “draws upon Page’s personal experiences of observing contemporary Indigenous people tracing their bloodlines, reconnecting with their traditional heritage and living modern lives in a challenging urban society” (press release). The second new work of the evening, About, comes from emerging choreographer Elma Kris. The rise of Kris, Daniel Riley McKinley (RT98) and Vicki Van Hout (RT104) makes this an exciting time for contemporary Indigenous dance. The double bill will tour nationally. Bully Beef Stew, PACT Centre for Emerging Artists, June 29-July 9; www.pact.net.au; Bangarra Dance Theatre, Belong—ID and About, QPAC, July 1-9, then touring to Sydney, July 20-Aug 20, Perth, Aug 25-28, Canberra, Sept 2-3, Wollongong, Sept 8-10, Melbourne, Sept 15-24; www.qpac.com.au, www.bangarra.com.au

The Lost Thing

image courtesy of the artist

The Lost Thing

the lost thing found at the powerhouse

Still in Queensland, and just in time for the school holidays, the Brisbane Powerhouse presents Shaun Tan: The Art of the Story, a free exhibition showcasing the art of the Academy Award winner and children’s illustrator. On display will be limited edition prints of illustrations from his books The Rabbits, The Red Tree, The Lost Thing, Tales from Outer Suburbia and The Arrival (we reviewed Red Leap theatre’s adaptation of The Arrival in RT94). The exhibition also features the film version of The Lost Thing, which won this year’s Oscar for Best Short Animation as well as last year’s Yoram Gross Animation Award at the Sydney Film Festival (RT98). Shaun Tan: The Art of Story; June 28-July 10; www.brisbanepowerhouse.org

underbelly

In the wake of Imperial Panda (reviewed in our last e-dition) and Tiny Stadiums (reviewed in this one), comes another Sydney-based arts festival—Underbelly (see the interview with director Imogen Semmler in RT103). Previously staged at CarriageWorks (RT80) and Queen St Studios and surrounds in Chippendale, this year the festival heads to Cockatoo Island in Sydney Harbour. The festival proper is on for only one day, on Saturday July 16, but a 10-day preliminary program, The Lab, allows audiences to visit during the development period so they can watch the art unfold that’s been developing for several weeks. If you’re feeling particularly participatory, you can attend an Open Project session and contribute to the development of an anthropological experiment Case Study, Butterfries’ haunted-house inspired The All You Can Stand Buffet and Dan Koop’s The Stream/The Boat/The Shore/The Bridge, a human-scale board game in which the audience are the players. Underbelly Arts Festival, July 3-12, www.underbellyarts.com.au

Dave Brown (aka candlesnuffer), Liquid Architecture

photo courtesy of the artist

Dave Brown (aka candlesnuffer), Liquid Architecture

sound flows

For more than a decade, the Liquid Architecture: National Festival of Sound Art has showcased the best of the world of sound art (see our Archive Highlight).This year’s program includes artists Marc Behrens (Germany) who is bringing with him sounds from China and the Amazon rainforest, Pascal Battus (France) who shapes his instruments to match his body gestures and insists on offering the occasional “sound massage” and Lukas Simonis (Netherlands), who in collaboration with Melbourne’s Dave Brown, will display his mastery of guitar improvisation. They are joined by Australians Pia van Gelder, with her own electrical inventions, plus Jon Rose and his ‘Team Music’ live interactive netball game. The festival has already kicked off in Melbourne where it continues until July 2 with concerts running simultaneously in Perth (June 27-28), Bendigo (June 29) and Brisbane (July 1). Arriving in Sydney on July 2, Liquid Archtecture will feature two free concerts at the Eugene Goossens Hall in the ABC’s Ultimo Centre, Sydney (no booking required) and Battus’ Sound Massages on July 3. If you can’t be there in person, you can hear the performance broadcast that night on ABC Classic FM’s New Music Up Late. Liquid Architecture: National Festival of Sound Art, June 27-July 3; www.liquidarchitecture.org.au; www.abc.net.au/classic/newmusic

Show and Tell

scenes from the arab spring

Since last year’s Arab Film Festival, there have been revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, a civil war in Libya, uprisings in Bahrain, Syria and Yemen, major protests in Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Morocco and Oman and minor protests in Kuwait, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia. In other words, it’s a time of incredible change. Now in its 10th year (see our reviews from 2007 and 2010), this year’s Arab Film Festival presents 22 “front-line stories” from around the region, many of which have been presented at recent festivals in Cannes, Dubai, Berlin and Sundance. Highlights include Sarkhat Namla (The Cry of an Ant), the first feature film to address the Egyptian Revolution this year; Stray Bullet, which features Lebanese actress Nadine Labaki in her first role since the internationally acclaimed Caramel; and Into the Belly of the Whale, where we follow a man trapped in the supply tunnels under the border zone between Israel and Egypt. Local films include Mary, a story of neighbourly espionage in Western Sydney, and Show and Tell which examines the link between object and memory of recently arrived refugees in Sydney. There’s also a forum on July 1 titled Revolution, Romance, Realities, which will address “how new media has facilitated a critical mass movement, amplifying everyday voices, transmitting images globally” (press release). Speakers include Dr Paula Abood, Randa Abdel Fattah, Farid Farid and Sameh Abdel Aziz. The festival will then tour to state capitals. 2011 Arab Film Festival, Sydney June 30-July 3, Melbourne July 8-10, Canberra July 14-17, Adelaide July 23-24, Brisbane July 30-31; www.arabfilmfestival.com.au

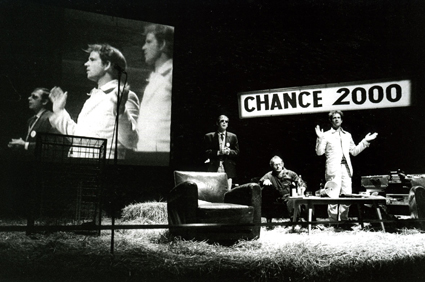

life after death in venice

In our most recent print edition, we interviewed Anna Teresa Scheer about the work of Christoph Schlingensief (RT103). Schlingensief died of cancer in August 2010 at the age of 49, but a few months prior curator Susanne Gaensheimer had approached him to design the German Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011. Instead of abandoning the project completely, or attempting to realise it exactly as the artist had imagined, Gaensheimer chose a middle path, presenting Schlingensief’s plans in book form ahead of the event and then using the event itself to show a selection of his works, without attempting a retrospective. She was rewarded for her efforts on June 4, when the German Pavilion was presented with the Golden Lion for Best National Participation. You can see the announcement on the Biennale’s YouTube channel, read an interview with Gaesheimer in Deutsche Welle and an interview with Schlingensief’s widow Aino Laberenz in Der Spigel. For footage of the pavilion itself, see Vernissage, the official website Deutscher Pavilion and Schlingensief’s own personal website.

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Applespiel, Executive Stress/Corporate Retreat

photo Michael Myers

Applespiel, Executive Stress/Corporate Retreat

HOT ON THE HEELS OF IMPERIAL PANDA COMES TINY STADIUMS—ANOTHER SYDNEY-BASED, SELF-PRODUCED FESTIVAL THROUGH WHICH EMERGING ARTISTS GAIN BOTH EXPERIENCE AND EXPOSURE. THE TWO FESTIVALS SHARE MORE THAN A DIY SENSIBILITY AND A FONDNESS FOR QUIRKY NAMES, THEY ALSO SHARE SOME CURATORIAL TALENT—MISH GRIGOR CURRENTLY SERVES ON BOTH ORGANISING COMMITTEES AND ZOE COOMBS MARR AND EDDIE SHARP HAVE DONE SO PREVIOUSLY. SO IT’S NOT SURPRISING THAT, LIKE IMPERIAL PANDA, TINY STADIUMS PROVIDES A DIVERSE PROGRAM THAT COMBINES LIVE ART IN A VARIETY OF LOCATIONS AS WELL AS SOME MORE THEATRICAL OFFERINGS, INCLUDING A GOOD OLD FASHIONED DOUBLE BILL AT PACT THEATRE.

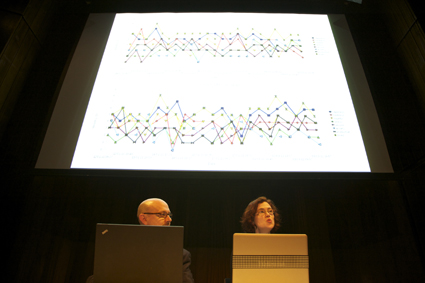

First on the program is Applespiel’s Executive Stress/Corporate Retreat, which, as you might suspect from its title, is a satirical take on every self-improving, team-building, life-affirming exercise you’ve ever had the misfortune to endure. The show starts with an invitation from a young man in a snappy suit to enrol in the elite club. Several audience members head to the desk while I hang back, until I remember that I am reviewing the piece so I’d better participate. Unfortunately the elite club closes just as I reach the desk—hesitation then rejection, that’s a double fail. Having been photographed and name-tagged, the elite club members now circulate with “ice breaker” exercises, asking the non-elite about our allergies, holidays and siblings. Ice broken, we then do another survey, where the performer poses a question and we stand on one side of the foyer or the other, depending on whether we like tennis, have a father with a drinking problem etc. Finally, we enter the theatre and as we take our seats—elite club at the front, mere mortals at the back—we see several performers in black suits sprinting back and forth across the stage.

The rest of the show basically consists of Applespiel running a corporate workshop, demonstrating an exercise and then directing the elite team to do it on stage. These efforts are then scored and the results displayed in a sort of league table, which is projected onto a large screen upstage. The exercises include mock job interviews, in which participants are asked not only about their strengths and weaknesses but also about which food they most resemble. “An egg” is the recommended answer, for its ability to work solo and in combination with a variety of other ingredients, its balance of protein and fat, not to mention its facility for segueing from one cuisine to another. Do not say “banana” as they are “the first to go missing in a crisis.” Participants are also taught an obscene rhyme in order to remember how to tie the perfect Windsor Knot and led through a strange series of actions to find their totem animal. Last but not least, they close their eyes and vote on each other’s performance.

There are some amusing moments and the premise has real potential, but it isn’t completely fulfilled here. On the night I attend, the elite club members are oddly acquiescent, to the point where I was dying for someone to throw a spanner in the works. But the closest anyone got was when one participant refused to grade the others’ performances, instead giving them all a thumbs up. While this may be due to the nature of this particular ‘team,’ I suspect the problem is structural for the rules of workplace and audience participation are basically the same: as audience members we’re aware that we have entered into a contract, that the performers are depending on us and we don’t want to let them down. These are of course exactly the thoughts of hapless employees as they are conned into doing just one more hour of overtime. Thus, even as Applespiel seek to mock the mindless supplicants of the corporate world, they implicitly rely on their audience to behave similarly. There is much more to be mined here and I was reminded of Jon McKenzie’s book Perform or Else! (Routledge, 2001), an elegant exploration of how corporate, technical and theatrical notions of performance intersect. With this in mind, I look forward to undertaking another “performance review” of Applespiel soon.

Nat Randall, Cheer Up Kid

photo Michael Myers

Nat Randall, Cheer Up Kid

While Executive Stress employs a cast of thousands, Cheer Up Kid is the work of just one writer and performer—Natalie Randall. She runs on stage wearing a white t-shirt, black pants and the broad grin of a child who has finally coerced the family into sitting down for a living room show. She briefly outlines the structure of the show, noting however that she is “completely unreliable, with no sense of consistency or consequence.” These words are repeated at the beginning of each section, so that we hear the same phrase recited by different characters, in different accents. In the second section, Randall plays a weird and bad-tempered child, who is prone to swallowing whole bottles of Vitamin C tablets, exaggerating her achievements at the school swimming carnival (winning that little known race, the 300 metres), getting swooped by magpies and secretly eyeing off the twice-cooked pork belly while being made to order the chicken schnitzel. In the third section, Randall plays an American agony aunt who slugs back a bottle of Passion Pop while dispensing advice on air, and in the fourth she plays a lonely Englishman scared his parents might die before he does.

Randall has a warm and generous stage presence, and I really enjoyed her performance in Some Film Museums I Have Known, but here she is let down by the writing, which is somewhat underdone. The characters are interesting as individuals but the connection between them, beyond their origin and juxtaposition, is not necessarily clear. Nevertheless the show, and with it the night, comes to a satisfying end when Randall slices up a “pool cake” (a classic from the Women’s Weekly cookbook) and passes it around—a gesture of generosity and hospitality that seems to encapsulate the theatrical act itself.

Tiny Stadiums Festival: Applespiel, Executive Stress/Corporate Retreat, devisor-performers Simon Binns, Nathan Harrison, Nicole Kennedy, Emma McManus, Joseph Parro, Troy Reid, Rachel Roberts, Mark Rogers; Cheer Up Kid, devisor-performer Nat Randall; PACT, Sydney, May 2-15

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. web

© Caroline Wake; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Simon Corfield and Sarah Enright, Trapture

photo courtesy of the artists

Simon Corfield and Sarah Enright, Trapture

ALL PLEASANT BREAK-UPS ARE ALIKE; EACH UNPLEASANT BREAK-UP IS UNPLEASANT IN ITS OWN WAY. WHICH IS WHY THE ONE AT THE HEART OF SARAH ENRIGHT AND SIMON CORFIELD’S TRAPTURE IS SUCH A CURIOUS THING: BY ATTEMPTING TO COVER THE UNPLEASANT BREAK-UP FROM EVERY CONCEIVABLE ANGLE—TO GIVE US, IN A SENSE, THE UR-BREAK-UP—THE PRODUCTION DOESN’T GET TO THE ESSENCE OF THE MESSY SEPARATION SO MUCH AS MERELY PRESENT US WITH A GENERALISED SURVEY OF ITS MOST COMMON AND PREDICTABLE FORMS. THE RESULT IS A PAGEANT OF MILLS & BOON METAPHORS LITERALISED AS STAGE GROTESQUERIES: AN AT TIMES HILARIOUS, BUT ALWAYS SUPERFICIAL, BREAKDOWN OF THE BREAK-UP.

The evening begins with an embrace. Enright, her mouth taped up and her wide, slightly unhinged-looking eyes meeting yours, takes your ticket, asks with a silent gesture if you would like a hug, and then takes you in her arms. The Old Fitzroy’s little theatre has been done up to resemble one of those plastic-draped rooms in otherwise empty warehouses where psychopaths wine and dine their victims before hacking them to pieces. This, as we will soon learn, is appropriate: of all the things to which Enright and Corfield compare the break-up, the most notable are disembowelment and related acts of torture. The central conceit of the piece is to realise emotional violence as physical violence.

This is, of course, something we do every day when we equate the two in language. A pleasant break-up is what you get when both parties choose to “end the relationship.” An unpleasant one is what you get when the metaphors start creeping in: when the man “emotionally raped me” or the woman “tore my heart out.” Men become “pigs” and women “bitches.” One party claims the other can “eat my shit.” For Pat Benatar love is a “battlefield.” Kramer Vs Kramer and The War of the Roses—Danny De Vito’s, not William Shakespeare’s—incorporate this idea of conflict into their titles. And Trapture seeks to give each of the above its time in literalism’s spotlight.

The show begins with Enright and Corfield dressed for a fancy date, making their way to a couch at the far side of the stage. She blindfolds him—he thinks it’s foreplay—before taking out a suitcase, throwing a few things into it and leaving him sitting there. When he finally realises what has happened, things really begin to fall apart: Enright re-emerges, dressed in surgical garb and gives her former partner a sex-change operation. Sporting a Koskian prosthetic and killer heels, Corfield waves his new vagina around in the faces of those in the front row. The performers climb into the audience, invading personal space. Masks emerge. Corfield becomes a pig and Enright a dog, the former forcing the latter to eat his shit and smearing it across her mouth. They throw bedpans of urine at one another.

Sarah Enright and Simon Corfield

photo courtesy of the artists

Sarah Enright and Simon Corfield

In the production’s most graphic and unsettling scene, Corfield dons a clown mask and rapes Enright. She gets her revenge by sticking her hand into his chest and tearing out a cow’s heart. It’s an image straight out of The Simpsons episode “New Kid on the Block” and it is difficult for anyone familiar with that episode to take its recreation here very seriously. Indeed, I found myself marvelling less at the literalisation of the metaphor—which, as The Simpsons’ writers understood only too well, is not so much profound as hilarious—than at the fact that the actor had been wearing a bloody bovine organ strapped to his chest for the duration of the performance. Enright cooks the heart on a portable hotplate and feeds it to him. She eats a slice, too. An unholy communion.

All of this is rendered in a visual style reminiscent of visual artist and filmmaker Matthew Barney. Indeed, if Barney were to direct Artaud’s Jet of Blood, he might come up with something like Trapture. Only he wouldn’t. Barney’s use of metaphor is elaborate where Trapture’s is simplistic, providing his work with its deep, architectonic structures which are almost impenetrable. In contrast, Trapture’s structure is not even really that of a break-up, but rather a shopping list. And it’s a shopping list that, in the end, doesn’t really amount to much: referring back to a non-specific idea of a break-up—to the words we use to describe them—even the impact of the rape is lessened.

Shocking stage images, it seems to me, are becoming increasingly less shocking. I would argue that Sydney hasn’t seen a genuinely cutting one since Kosky put Robyn Nevin in Abu Ghraib for The Women of Troy (2008). As with Simon Stone’s Baal at the Sydney Theatre Company, which seems pitched to offend only a certain strata of the audience (namely the aging subscriber base), Trapture seems to suffer from putting too much stock in the inherent force of its images. That force is lessened the more it’s relied upon. It becomes increasingly difficult to care about, to invest in such images, which have less and less to do with the emotional content of an idea and more and more to do with their capacity to inspire walk-outs. Pass the heart.

Sands Through the Hourglass in association with Tamarama Rock Surfers, Trapture, director Shannon Murphy, conceived & performed by Sarah Enright and Simon Corfield, live sound design Basil Hogios; Old Fitzroy Theatre, Sydney, April 21-May 14. Trapture by Sands Through the House Glass won Best Show Sydney Fringe 2010.

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. web

© Matthew Clayfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ghenoa Gela, Briwyant

photo Marian Abboud

Ghenoa Gela, Briwyant

VICKI VAN HOUT’S CHOREOGRAPHY IS SOME OF THE MOST IDIOSYNCRATIC AND INVENTIVE SEEN IN AUSTRALIAN DANCE FOR A LONG TIME AND HER TEAM OF DEXTROUS DANCERS EXECUTE IT WITH HIGH PRECISION, UNBELIEVABLE ENERGY, HUMOUR AND ATTITUDE. VAN HOUT HAS BEEN A BUSY DANCER, CHOREOGRAPHER AND RESEARCHER TRAVELLING EXTENSIVELY TO INVESTIGATE INDIGENOUS DANCE. SHE HAS A COUPLE OF SUBSTANTIAL WORKS BEHIND HER, HOWEVER IT’S A NEW CREATION, BRIWYANT (FOR ‘BRILLIANT’), THAT COULD BRING HER THE ATTENTION SHE WARRANTS THANKS IN PART TO A SHORT BUT SIGNIFICANT PERFORMANCE SPACE SEASON.

In 2009 I was impressed by Pack (RT94), a sizeable piece in a Dirty Feet program of short works. I wrote: “In an intense work, four dancers, moving with bird-like alertness and the deep stepping of certain Aboriginal dance forms, map out their space territorially (with tape) and on each other’s bodies (with clothes pegs). Moments of intense, swiftly danced collectivity contrast with power plays and grooming displays—pegs removed gently from pinched flesh. This fascinating work, in which the tipping point seems to be whenever ‘enough is enough’ and the dividing tape is ripped up, fuses contemporary dance with Indigenous inflections to suggest that when it comes to territory we humans are pretty much just another animal.”

In Briwyant, Van Hout pays similar if much richer and more elaborate attention to the integration of dance with design. Scarves, for example, are transformatively shaped to suggest digging, cradling and the binding of one person to another. Hundreds of playing cards are arranged across the performing space evoking a riverscape. These are deployed, quite laterally, like the dots of the Indigenous paintings that fascinate the choreographer with their shimmering brilliance. On the Performance Space website, Van Hout writes, “Cards/ As the repetition of a dot/ Layed down as a river/ As a deck to share the wealth/ Made from?Dots on a canvas/ When sung/?Signify ancient power/ To transport us to the dreaming/?The everywhen.” She explains, “Briwyant is inspired by bir’yun: brilliance, shimmer and shine. In Yolngu traditional painting, bir’yun is the effect of intricate crosshatched patterns creating a sensation of shimmering movement over the painting’s surface, a manifestation of ancestral forces.” Briwyant conveys an engrossingly similar phenomenon when a dark upstage rectangle disappears the dancers but then bathes them in sparkling light.

The choreographer’s sources are many, drawing on and effectively melding diverse Indigenous and other forms within a dance theatre framework that ranges from droll rhyming verse (delivered by the charismatic Van Hout herself) to a lucid dreamtime tale transformed into dance, to witty social encounters and sometimes mysterious but never less than intriguing images pertaining to Indigenous art and culture.

Soundtrack, media and lighting are occasionally burdened with superfluities, but the best of Marian Abboud and Imogen Cranna’s digital media effects, Elias Constantopedos’ score and Guy Harding’s lighting fuse seamlessly with Van Hout’s organic exploration of the relationship between bodies and the lines, dots and the hatched ‘shimmer’ of Indigenous art. Danced organically across Van Hout’s playing card landscape design, this makes for a powerful experience, at once magically elusive and cohesive. Dancers Henrietta Baird, Ian RT Colless, Ghenoa Gela, Raghav Handa and Melinda Tyquin are superb.

See also an interview with Vicki Van Hout.

–

Briwyant, Performance Space, choreographer, designer, performer Vicki Van Hout, dancers Henrietta Baird, Ian RT Colless, Ghenoa Gela, Raghav Handa, Melinda Tyquin, digital media effects Marian Abboud, Imogen Cranna, composer Elias Constantopedos, dramaturg Kay Armstrong, lighting Guy Harding; Performance Space, CarriageWorks, Sydney, april 13-16

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. 32

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Vicki van Hout working on the installation/set of Briwyant

photo Marian Abboud

Vicki van Hout working on the installation/set of Briwyant

IT IS TWO DAYS AFTER THE OPENING NIGHT OF VICKI VAN HOUT’S NEW DANCE WORK BRIWYANT (FOR ‘BRILLIANT’). WE ARE IN BAY 20 AT CARRIAGEWORKS, THE SPACE WHERE THE PIECE IS PRESENTED. IF VAN HOUT FEELS AT ALL PLEASED WITH THE POSITIVE FEEDBACK HER LATEST WORK HAS RECEIVED FROM AUDIENCES, PEERS AND CRITICS ALIKE (P32), SHE CERTAINLY DOESN’T LET ON. “THE WORK ISN’T DONE YET,” SHE SAYS MATTER-OF-FACTLY.

And it’s easy to see what she means: The cavernous theatre space is split into two by an enormous river-like installation made up of several thousand playing cards. After every performance, each card needs to be reglued to the ground edgewise—a complicated procedure that takes up to seven hours. An activity expected from an installation artist maybe, but from a choreographer?

“You gotta give it a go,” Van Hout quips. “I’m a perennial student. I’m interested in other artforms. At first I thought this piece should be in an art gallery. Sometimes I feel dance is not enough anymore. I like integrating other forms of art into my work. In some ways it’s an excuse to find out about things I don’t know much about.” After a pause, she shrugs: “Who knows? Maybe at some stage there will be no dance at all anymore. My interest in the arts didn’t start with dance so maybe it won’t end there.” And as for those cards? “I’m lucky,” laughs Van Hout. “My 60-plus year old mum has taken time off work to help me and the stage manager.”

A Wiradjuri descendant growing up in Dapto in regional New South Wales, Van Hout didn’t start to train in dance until her late teens. All through high school she had taken drama lessons, wanting to become an actor. She recalls, “Around the time I was living in a squat, The Gunnery at Wooloomooloo, and this guy suggested I should go to NAISDA instead. I remember asking him: ‘What’s that?’ He said, ‘A place where you learn about your own people.’ I liked that.”

After four years at NAISDA, the National Aboriginal Islander Dance College, Van Hout received an overseas study award from ATSIC (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission) to train at the Martha Graham School of Contemporary Dance in New York. Far away from the usual preconceptions and prejudices regarding her aboriginality, Van Hout relished the opportunity to immerse herself in a culture not her own. “As I’m quite fair-skinned, not a lot of people recognized I was indigenous and hardly anyone asked any questions. I hung out with a lot of musicians from the alternative music scene and punk culture. Our haunt was Manic Panic, the now legendary punk store. Their tagline was ‘Live Fast and Dye Your Hair’.” And yet, Van Hout took her dance training very seriously. After graduating from the Graham School, she stayed in New York to train and work with various modern and postmodern dance artists. “My concern was that I wouldn’t have anything to show for my time there,” Van Hout says. “I didn’t want to come back without skills.”

All up Van Hout spent almost seven years in New York, eventually returning to Australia in 1996 to perform with Bangarra Dance Theatre on an Asian tour of their seminal dance work Ochres. She later joined Marilyn Miller’s Fresh Dancers collective created to focus on the corporate and commercial market. After initially working mainly as a dancer, she soon helped to choreograph many of the works presented at indigenous events and functions. She then gradually moved into creating her own work. “It was actually [fellow indigenous choreographer] Jason Pitt who encouraged me to take that leap,” remembers Van Hout. “One day he looked at me and said, ‘What have you got to lose? Just go for it, sister.”

And go for it, she did. Working incessantly over the following years, Van Hout has steadily built a reputation as one of our most interesting and prolific independent dance artists. She has developed a growing following for her deftly imagined and thoughtfully crafted works examining urban indigenous realities, especially in NSW.

Briwyant is Van Hout’s third full-length work. Conceived as a cross-cultural, inter-disciplinary dance piece, it examines the ongoing nature of ‘traditional’ Aboriginal practices based on story telling through the act of painting. As in many of her works, van Hout aims to explore the commonality between traditional and urban cultural experiences and how indigenous cultural information is disseminated: “I’m interested in what was, what is and what is similar. I’m always trying to find what is contemporary and relevant.” The work started out as an idea for a solo and evolved into its current form featuring six performers including herself.

“My initial interest,” explains Van Hout, “was in the question: what is it to look white and identify as indigenous? I wanted to peel back layers and find out what’s underneath.” She is outspoken on the issue of claiming her indigenous heritage: “It’s a birthright but not only a birthright. It’s living an obligation defined by what you do. You are what you do.” It is not surprising then that Van Hout is a passionate teacher who has been working at NAISDA for over 10 years. She feels a strong responsibility, she says, to pass on the cultural information and knowledge she has acquired. “I have been taught [Aboriginal traditional] dances, it is my responsibility to pass them on. They are not the sum of me though. I’m also teaching the contemporary indigenous technique that I have been developing through my own work. I want to instil body discipline in students so that they can be adventurous and try something different.”

As important as the engagement with her Aboriginal heritage is to her, at the same time Van Hout is adamant that she doesn’t want to be “put in a box.” She wants to be taken seriously as a choreographer on the basis of her skills, not merely for the fact she is indigenous. Recently interviewed for a case study of artists affiliated with Performance Space, she said: “It’s important to me to participate in the broader dance and performance arena. I want to be critiqued on a par with everyone else .”

This might explain Van Hout’s extensive engagement with dance outside exclusively indigenous contexts. In the last few years she has created numerous works for both tertiary institutions and youth dance companies such as ATYP, youMove, fLING Physical Theatre and DirtyFeet, as well as WAAPA, to name but a few. She also frequently employs non-indigenous dancers for her works. The cast of Briwyant, for example, is decidedly mixed. “We’re an eclectic bunch, no one is the same,” laughs Van Hout. And there is no question that she likes it that way. It confirms her fascination with juxtaposition, a device she frequently employs in her works.

“I like things that sit side by side and can’t be rationalised. I want to give people a glimpse, not lay it out for them.” The seminal experience that triggered her thinking in this respect occurred many years ago: “I was in Maningrida [indigenous community, Northern Territory], it was about 22 years ago, and I observed a young woman washing her child’s hair on a piece of corrugated iron while watching Dallas on a portable TV on the veranda of the nearby house. It was the most bizarre vision. But it had such poignancy and absurdist poetry. That’s what I strive for in my work.”

See review of Vicki van Hout’s Briwyant

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. 31

© Martin del Amo; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

MARTIN DEL AMO IS BEST KNOWN FOR HIS INTRIGUING SOLO WORKS AND FOR SOME OBSERVERS IT MIGHT SEEM THAT HIS MOVEMENT LANGUAGE IS SO INTERLINKED WITH HIS PHYSIOGNOMY THAT IT CANNOT BE PERFORMED BY OTHERS. HOWEVER FOR SEVERAL YEARS NOW DEL AMO HAS UNDERTAKEN A VARIETY OF RESEARCH PROJECTS INVOLVING HIM AS A NON-PERFORMING CHOREOGRAPHER. A RECENT PROJECT AT SYDNEY’S CRITICAL PATH SAW PAUL WHITE PERFORMING AN UNCANNILY ACCURATE YET TRANSFORMED VERSION OF ‘DEL AMO’ MOVEMENT.

Discussing his reasons for the transition from solo performer to director-choreographer, del Amo cites Kate Champion from Force Majeure who was also, at one stage, best known for her solo works. “Kate said you can only mine yourself for material for so long and at some point you get more interested in other people’s backgrounds, stories and ideas. I think this is exactly what happened to me. I’ve always really enjoyed working by myself and having that freedom but sometimes I thought it would be nice to work with other bodies and have another input on that level.”

Del Amo undertook some early research in 2008 with WAAPA’s post-graduate dance company, LINK. The work, Mountains Never Meet, an exploration of the difference between walking and dancing, was made with an all female cast. “I was working with very reduced movement material, but treating it in a complex way choreographically and that was quite difficult for the dancers…it [required] completely adapting or un-learning what they had studied over the years.”

While he found this process valuable del Amo says, “I felt there was something else in that work—the way it could communicate with audiences— that could be captured in a different way.” So for the version that is to take place in August as part of the Western Sydney Dance Action and Parramatta Riverside Dance Bites program, del Amo has chosen to redevelop the work with nine male non-dancers. Having finalised his cast with co-operation from Bankstown Youth Development Service (BYDS) he says, “I’m really happy with the guys that we’ve got now. It’s an eclectic bunch from different cultural backgrounds, different ages [ranging from 15 to mid-20s] and they also have slightly different sporting or physical backgrounds.”

For Mountains Never Meet del Amo has also invited former professional soccer player turned performer Ahil Ratnamohan—most recently seen in his own work, The Football Diaries (RT91, p42) and in Branch Nebula’s SWEAT (RT102, p15)—to take on the role of artistic associate. The working relationship between the two is an ever-evolving one. While del Amo has worked as a mentor on some of the younger artist’s projects, Ratnamohan has taken on the role of trainer and consultant on del Amo’s works such as It’s A Jungle Out There (2009-2010). “I wanted a more urban, non-dance feel and asked him to do soccer training with me to improve my footwork. Out of that—being his mentor and him being mine—we established some kind of training practice.” As well as performing in this project, Ratnamohan will have the roles of collaborator and liaison with the other performers. Del Amo says, “the choreography and direction is with me, but we’re actually sharing how that is being implemented.”

Ratnamohan will also perform in Duel, a duet with Connor Van Vuuren that Martin del Amo is choreographing to accompany Mountains Never Meet. “Duel involves much more intricate movement and is inspired by some memorable sporting battles, but not tied to one particular sport.” Again, the performers have different training backgrounds, Ratnamohan in soccer and van Vuuren in martial arts and gymnastics, so the choreographic relationship is ambiguous—“Is this a battle against each other, with each other or for each other? It’s also an investigation into what constitutes a duet. In some ways it’s set up as two intertwined solos rather than as a proper partnering duet.”

Del Amo is also known for his strong collaborative relationship with composers and in this instance he will continue his collaboration with Cat Hope who scored the original LINK version in Perth. Del Amo says, “The sound world Cat has created relates to the physical concept of the work without mirroring or imitating it. It features whistling, urban sounds such as AM radio and a big percussion section consisting of marching band sounds without the band music. Cat will digitally manipulate pre-recorded elements live which ensures some ‘breathing room’ for the interplay between movement and sound. “

Both Mountains Never Meet and Duel look to be exciting additions to Martin del Amo’s impressive and highly idiosyncratic body of work.

Western Sydney Dance Action & Riverside Theatres 2011 Dance Bites, Mountains Never Meet, choreographer Martin del Amo, artistic associate Ahil Ratnamohan, performers Ahil Ratnamohan, Connor Van Vuuren, Fraink Maino, Benny Ngo, Mahesh Sharma, Sean Stanley, Nikki-Tala Tuiala Talaoloa, Dani Zarodosh; composer Cat Hope; Parramatta Riverside Theatre, Aug 17-20

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. 32

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Sandra Parker, Document

photo Rachel Roberts

Sandra Parker, Document

MELBOURNE CHOREOGRAPHER SANDRA PARKER’S LATEST WORK DOCUMENT, “AN IN-DEPTH EXPLORATION OF THE WAY IN WHICH A ROOM RETAINS THE RESIDUE OF HUMAN OCCUPATION,” WILL PREMIERE IN JULY. THE WORK IS EMERGING FROM A 14-WEEK RESIDENCY AT DANCEHOUSE. PARKER WAS ARTISTIC DIRECTOR OF DANCE WORKS 1998-2006 MAKING DISTINCTIVE CROSS-ARTFORM CREATIONS. HER WORK HAS BEEN SHOWN INTERNATIONALLY, INCLUDING NEW YORK IN 2007 WITH THE VIEW FROM HERE, AND IN CHINA WITH PLAYHOUSE FOR THE GUANDONG MODERN DANCE COMPANY.

Will you physically create a room or use video and movement to do so?

I’m interested in trying to evoke a room, a rehearsal or performance space in image and light; and also through using language to describe the qualities of the space. I’m keen to play with the juxtaposition of the actual performance space with details about the space conjured up by using other media. This may or may not confirm what is actually there in the ‘real’ space, or might have been there at another point in time.

Who are the artists you’re working with and how will each contribute to your exploration?

Rhian Hinkley (projection designer; see p29), Jenny Hector and Rose Connors Dance (lighting designers), Steven Heather (composer) and Rebecca Jensen (dancer) will bring responses to the ideas and offer material. Our collaborative approach is to see where the correspondences, counterpoints and parallels lie between forms then try to find combinations that open up and suggest ways of experiencing the ideas at play within the performance. For example, I might make movement that I think feels one way but, when watched with certain sounds, radically alters the perception of the movement. I look for ways to use collaborative material as active in the performance and not just ‘accompaniment’ to the main action. I’ve also asked performers I have worked with before to contribute to the process of making the work.

Precisely how do you generate the material—do you have a particular methodology?

I began the project by asking dancers Deanne Butterworth, Carlee Mellow and Joanna Lloyd— with whom I have worked previously, but who won’t be directly involved as performers in this project—to come into the studio with me and respond to a series of questions through a ‘performed interview’ about work we have created together. In one case, this spanned back some 15 years. I am interested in not only what they remember of the movement and why, but also other things that are remembered about making work. Responses have ranged from things like describing the atmosphere of the space, how they felt about what they did, how they approached performance and personal things that were going on in their lives at the time.

I’ve also been interested in trying to describe movement. The gap between what we think movement is, what we say about it, how it appears and if it can ever be ‘perfectly’ documented in language, video or sound; and also the sometimes vastly different perception of process, choreography and performance that can exist between the choreographer, external to the work and the dancer internal to it.

I’m working with Rebecca Jensen for the first time. We met at VCA and again when I led the Learning Curve residency for recent graduates at Dancehouse in 2010. Earlier this year Rebecca also came and worked on secondment during a creative development for my new project, The Recording. She represents a new generation of young Melbourne-based dancers. I was interested to work with someone with whom I have little history, as opposed to the long-term relationships I have with Deanne, Carlee and Jo. I am interested to see how Rebecca works with material that is passed on to her through these dancers and how it changes. What detail is maintained, or left behind.

Elsewhere you’ve used ‘documents’ to describe what comes out of your process?

By documents, I mean creative material. I usually work by generating a lot of material and collect movement phrases, sound, text, video material, then start layering things. I look for tension between elements: a summation of parts. The collected material will range from drafts of choreographic material to ‘formed’ phrases that we have decided are finished. I want to try to use everything—even if it isn’t necessarily ‘finished’ material.

You’ve expressed “an interest in capturing the physical traces and after-effects of movement once it has passed,” saying, “ Document will chronicle the evidence of events that are seemingly over and complete, yet somehow remain.” Given the preoccupation with “the now” in the work of a number of contemporary practitioners it’s fascinating to see you addressing traces. How did you come to this preoccupation?

I think this interest harks back to some really early works, in absentia (1997) for example, a work with 16mm film that I made with Margie Medlin. The ephemeral nature of dance is so fundamental to working in the form that it poses a central problem that I have always found challenging and opens up many questions about how to approach dance making. I’m interested in the problem of trying to capture movement—actually ‘choreograph’ it, to set it down, if in fact that is ever really possible. The problem of trying to set movement and then return to it and re-perform it, could be seen as a futile exercise in trying to reclaim that which can never be recaptured; but for me it also offers a way to question assumptions about what you think is ‘there’ and to make it anew, to reinvent, to ask what else movement can do.

The fact that movement is ephemeral lets you give it up and move in new directions. So if traces exist in the work they are there as tools to show this difference—not simply as nostalgic recollections, but to say, this is what it might have been, but now this is what it could be.

You’ve written, “the process of creating Document will seek to investigate how choreography can be understood as a record of bodily memory and sensation.” What do you think the ramifications of this are for choreography?

A few years back I watched a documentary on the Ballet Russes that contained footage of company dancers re-enacting choreography. I was struck by how their bodies held very clear sensations of movement, even though they weren’t leaping through the air. I was intrigued by how this represented a dance experience because much of what we normally expect from dance was completely taken away, yet it felt so ‘full.’ I became interested in the ramifications of this for choreography, to move beyond representation or conceptualising movement to the co-presence of phenomena interior to the body as it moves. I’m interested in exploring the possibility of creating a poetic choreographic rendering that envelops and embeds a density of experiential phenomena under the surface of choreography, what French dance writer Laurence Louppe suggests is “the tracing of what the letter does not say, but where another text shows through, another reading of living substance.”

I think this is especially relevant given the current preoccupation in dance with needing to produce ‘product’ that has a sense of solidity about it. Or that appeals directly to particular tastes or markets or can be identifiable in certain terms. I am interested in trying to open up and question what is there before us on stage.

You’ll find reviews of Sandra Parker’s works in our extensive 1994-present

archive, RealTimeDance

Sandra Parker, Document, from Housemate VII Residency, Dancehouse, July 27-31; www.dancehouse.com.au

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. 33

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Spotlight Bunny, Julie Vulcan, Ashley Scott & Friends with Deficits

courtesy the artists

Spotlight Bunny, Julie Vulcan, Ashley Scott & Friends with Deficits

ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT DEVELOPMENTS FOR PERFORMANCE IN RECENT YEARS HAS BEEN THE EMERGENCE OF YOUNG INDEPENDENT PRODUCERS, FESTIVAL DIRECTORS AND CURATORS. MANY ARE WOMEN, OFTEN WORKING IN TEAMS AND PRODUCING EVENTS THAT PRESENT BUT ALSO NURTURE NEW WORK—DRAMATURGICALLY BUT ALSO IN TERMS OF MANAGEMENT, RISK AND TECHNICAL AWARENESS. IMOGEN SEMMLER IS ONE SUCH PRODUCER CREATING UNDERBELLY IN 2007, A FESTIVAL WHICH SUPPORTS INDIVIDUAL ARTISTS AND GROUPS, EMERGING AND ESTABLISHED, WORKING IN A VARIETY OF PRACTICES. THIS YEAR THE THREE-WEEK WORKSHOP AND PERFORMANCE DAY WILL BE STAGED ON SYDNEY’S COCKATOO ISLAND.

Underbelly in 2011 predictably includes a diverse range of projects. Here’s a few examples. The Sexy Tales Comedy Collective will develop a theatre and music work titled 100 Years Of Lizards. Neil Brandhorst’s Horizon will be an installation that “disrupts the sensory information required to make sense of the environment…revealing how previous experiences provide meaning in new situations, and result in the feelings and urges that become our behaviour.” Spotlight Bunny, a work conceived by Sydney performance maker Julie Vulcan working closely with sound maker Ashley Scott and emerging performance collective Friends with Deficits to “explore location, the influence of soundtrack and the slippery nature of context. Influenced by drive-in culture, it blends the past with today’s iPod culture in an intimate performance for four audience members at a time in a stationary car.”

In Inflate My Heart With 1000 Gushes Of Wind, Swanbrero will “insert a piece of Parramatta Road into the natural wonderland of Cockatoo Island. The work will experiment with large-scale interpretive choreography, costume and wind to create melancholic spectacle.” The group (Corey Crushcore Dreamlover and Lara Thoms) describe themselves as “faded, cheap, fraying and bending over so far that their heads are scraping the ground.”

Tell me about starting up Underbelly and why you did it?

I come from an events background, working on different festivals and putting on little events myself—sort of underground. I liked the idea of bringing a lot of artists together in a festival but also starting with the development of their projects. Having artists together you’d see them make great connections, but it was fleeting and then they were off. So I thought it would be good to bring development and presentation together under the one roof.

Secondly, I felt there was a lot of stuff happening in Sydney at the time that was perhaps a bit hard to access, say about five years ago. There were great underground spaces but you had to be in the know. This was pre-emailing list, pre-Facebook, so it was more text messages or word of mouth. I started talking to groups who I’d been working with or knew of and put together a group of local artists with projects.

The first year was very much curated. I came up with the concept and just did it with people I was interested in and staged it at CarriageWorks. The second year we did it there again but it was open to applications—a lot of people said, how can we get involved? So that process has continued, which has been great.

You’re still curating or is it more like a fringe festival model?

We have a curating committee—applications come in and we choose projects. We have certain loose criteria—to support emerging artists and artists experimenting with new forms or more established artists pushing themselves in new directions or wanting to do more research-based work.

Would you or your committee have seen much of the work?

Not necessarily. We focus on new work. Artists have to have a pretty good argument as to why their work should be included because the whole idea of the residency is to present something for the first time. Sometimes it’s a work in progress. Some projects develop just a few scenes or the beginning of an idea.

And audiences watch the development?

Yes. We’ve had shows that have gone on to become fully formed and feature at fringe festivals or Next Wave. It’s good to get projects at an early stage—they need the lab time.

So you’re providing a service for people to innovate. Do you charge artists for that?

No. This year we’ve developed a project fund. It’s not a huge amount of money but we want to resource projects. We don’t want artists to be out of pocket. If they come with an existing grant or other support, that’s great but we do try as best we can to facilitate their project; that includes technical support, publicity, marketing, the venue…And we provide a lot of mentoring. For a lot of the artists, this might be the first time they’ve been involved in a festival. We help them with producing, budgeting, maybe the technical side of producing and we ask them all to do risk assessments. They might not have done that before so we’re happy to hold their hands and take them through the process. But we’re not doing it for them—we make sure they learn. There’s a lot of contact. We have a producer who works directly with the artists. I did this in the first few years but now we’re expanding.

How many of you are there?

At the moment there’s Clare Holland, our executive director, and myself. In two weeks we’ll have our event producer Jenn Blake and then we’ll have a production manager, a technical co-ordinator and a marketing co-ordinator, a publicist and an artist co-ordinator, like a program co-ordinator who manages all the artists. So it’s a big team!

Corey Crushcore Dreamlover, Inflate My Heart With 1000 Gushes Of Wind, Swanbrero

courtesy the artists

Corey Crushcore Dreamlover, Inflate My Heart With 1000 Gushes Of Wind, Swanbrero

Does the income from box office keep the event afloat?

Box office is a very small part of our income, mainly because the lab is running for three weeks prior to the festival which is a one-day event—and we try to make the tickets quite cheap, around $15 to $20. It’s a bit like a music festival where you choose shows and wander round installations. You get to see the whole gamut of what’s on offer. We started out with very little money, but CarriageWorks was a great venue partner—they gave us a lot of in-kind support.

We set up as a not-for-profit organisation and grew gradually. We started getting support from the City of Sydney, set up more formally in 2009, and had a year off because I realised it wasn’t going to be sustainable if we just kept doing it on a shoestring.

We get Arts NSW funding and we’ve recently received first time Australia Council funding for this event through the ARI [Artist Run Initiative] fund. We’ve also found really interesting partnerships with foundations whose interests are aligned with ours, and we have an amazing board.

How do audiences engage with Underbelly?

During the lab, we run tours. We invite the audience to come and watch the projects in development. One of us will take you round and you’ll meet the artists. And what’s happening more and more, because of the audience component at the lab, is that artists are applying with projects that need the audience for development—maybe content generation or particular feedback or testing things or interactivity or even making or building things. So that allows the lab experience to be really fun for the audience and it’s also giving artists unique access to the public through a residency. So it’s not just a work in progress showing. It might be the I Can Draw You a Picture team—they made a printed publication last year with the audience generating the content during the lab.

We call this the Public Lab. People can come pretty much every day for 10 days of the three weeks. You can come out to the island and do a tour. Projects that really require audience participation might want two hours a day. So we’ll pop that in the lab calendar that from, say 1-3pm, head out to the island and you can take part in this project. There’ll be social experiments where the audience become active participants. A quarter of our projects would have that component but it’s often those that then go on to other festivals. There’s a real live art push and I think that term is constantly evolving where once it was performance art or contemporary performance. In this area huge boundaries are being blurred between audience and artists and participants.

What characterises the works that appear in Underbelly?

We have a lot of installation, works by visual artists and filmmakers. We’ve had a couple of dance films over the years—the dance pieces are created on site, filmed, edited and shown. A filmmaker last year made a 3D video where you looked through a little box. He did it with really cheap technology because he’d been working in really high-end production for big companies but he wanted to show people how you could do it really cheaply and easily using a few mirrors and an old monitor. We also have a lot of dance and theatre. We’ve had the classics—Pig Island and Eddie Sharp. Whale Chorus are back this year with a project. There a lot of emerging and experimental theatre people, a lot of hybrid stuff, a lot of blending and theatre work like Eddie Sharp’s Some Film Museums I Have Known (shown at the Old Fitzroy recently).

The word that was associated with Underbelly for a while was “underground.” Is that still a viable term?

I think it’s really moved on, particularly in Sydney. The “underground” as it was five years ago has really blossomed through different changes such as to the licensing laws, the support of FBi Radio, the inner west venues—different elements that have brought that culture out into the open. For years you heard that there wasn’t much going on in the arts unless you were in the know. Now people are saying, “oh wow there’s heaps of stuff happening.” You see it in events like Tiny Stadiums, Imperial Panda, new venues, Performance Space’s LiveWorks and their Clubhouse. A lot of it is because groups have come out of what was the underground five or 10 years ago.

Is Underbelly becoming more of a full-time job?

It’s becoming more full-time, which is great. Bringing Clare Holland our executive director in has been a huge part of that—the ability to work year-round and find the funding to do it. It’s not full-time but it’s definitely part-time most of the year. I do other independent producing work. I did the Statues Project for City of Sydney’s Art and About last year and I produce some theatre for other people. I do research for documentaries in my other life. It’s about juggling. I think making Underbelly sustainable has been a really big focus. .

You usually get a good turnout on the big day. How many are you anticipating this year?

We’ll expect maybe 1200-1500 if it’s a nice day. If it’s raining, it’s about who wants to get on the ferry. The thing is, people like going out to Cockatoo Island. Even though it’s winter. I think the Biennale has shown that everyone’s still pretty happy to go out there and its all under cover. You don’t have to worry about getting wet—you just don’t take your jacket off.

Underbelly Arts, Underbelly: Public Lab, July 3-12; Festival, Cockatoo Island, Sydney, July 16 , http://underbellyarts.com.au

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. 34

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Baal, Malthouse & STC

photo Jeff Busby

Baal, Malthouse & STC

SIMON STONE CREATES HAUNTED THEATRE. NOT HAUNTING THEATRE (THOUGH IT CAN BE THAT). AND NOT THEATRE THAT HAS MUCH TRUCK WITH THE SUPERNATURAL, THOUGH I WOULDN’T GO SO FAR AS TO SAY THAT HIS IS A WHOLLY SECULAR OR MATERIALIST AESTHETIC, EITHER. BUT LIKE MANY OF HIS CONTEMPORARIES, HIS THEATRE IS SHADOWED BY RESTLESS SPIRITS AND THIS IS NOWHERE MORE EVIDENT THAN IN THE DIVIDED RESPONSES TO HIS RECENT PRODUCTION OF BERTOLT BRECHT’S FIRST FULL-LENGTH PLAY, BAAL.

The reactions to this production have canvassed the spectrum from rave to rubbish; on Alison Croggon’s Theatre Notes blog, the play produced one of the longest series of comments to date, with much passion displayed by respondents. It often came down to its writer: was there enough Brecht in here, or too much? And which Brecht? If this is the least ‘Brechtian’ of his writings, what can we do with it? Can we tackle Brecht from a post-Brechtian position, or is he inextricably embedded in the firmament of Western theatre?

It was Derrida who coined the term ‘hauntology’ and, while only a minor part of his critical theory, it’s a concept that has been picked up and developed in other areas, most notably musicology. For Derrida it was a notion used to explain the lingering presence of Marx in the post-Marxist era—an age which has seen the death of the Communist project, but which is still haunted by its echoes. The spectre of Marx is neither living nor dead; or, we may be done with the past, but the past isn’t done with us.

Brecht is dead. Long live Brecht. A canon-related demise, perhaps. If, as Nietzche argued, a being is only defined at the point of death, when the possibility of becoming something else is reduced to zero, then poor Bertolt is as stiff as a plank. It’s hard to think of anything new that the writer could become. We’ve picked at, held up and turned over every scrap of his corpus. At best, a new production can aspire to the level of autopsy.

The point here is that Stone should be able to do whatever he pleases with the body of Baal, but his liberal reworking of the original is troubled by the elusive spectre of its progenitor. It’s a problem that unsettles so many adaptations of modern classics—we know what this text has to mean, so why is the voice of its author just a faint distraction at the edge of hearing? You can do what you want with your source—it’s the postmodern age, after all—but make sure the “spirit” of the original is firmly contained. It’s a criticism that’s been levelled at Kantor, Andrews, Lutton: they’re dressing phantoms in fancy robes, only serving to remind us of the death of the authentic, original voice.

And so this Baal is haunted by what it’s not. Stone reimagines the barbarous, adulated poet at its centre as a misanthropic rock god celebrated by the very society against which he pits himself. In this vision his descent into squalid self-gratification becomes a retreat into narcissistic solipsism; everyone in his world becomes a fractured mirror on his own psyche. Theatrically, it’s a potent interpretation: Stone establishes a recognisable onstage world before flipping a switch and taking us into an utterly different mode of being, in which ‘character’ (already a loosely applied concept here) is not just destabilised but liquidated.

It should be effective stuff. But there’s that spectre that won’t be laid to rest: what about Brecht? Why should it matter? I don’t think the playwright’s original text is all that much chop (neither did he, in the end). So why should it matter where he exists in all of this? It’s a question that hovers around Beckett too, and Chekhov, and Ionesco. I don’t think it should, but I don’t know what to do about it. Call in an exorcist.

Real TV’s recent production of British playwright Debbie Tucker Green’s Random was anything but haunted—it’s as fresh a piece of theatre as I’ve seen in years performed with a vitality that exceeds containment, with an immediacy that’s bracing. It’s difficult to believe that the script wasn’t written specifically for sole performer Zahra Newman, at times seeming almost as if it’s being written at the moment of utterance. It might be the unfamiliarity of the material, which traces a tragic day in the life of a British-Jamaican family of four; it’s a corner of London life that I can’t recall having been represented on Australian stages. But credit should really go to Newman’s performance, which I found jaw-droppingly acute. Her command of four distinct voices seems measured down to the micro-tonal level; even the simplest of gestures here conjures both character and the world in which they exist. Director Leticia Caceres has honed the piece to a fine point: there are no slack moments or unnecessary embellishments.

Random was presented at Brisbane’s WTF (World Theatre Festival) this year before a season with Melbourne Theatre Company. I was intrigued to see the Melbourne season located within the MTC’s education program. Certainly, it’s a piece that will easily resonate with teens and, quite likely, inspire many to delve deeper into theatre. But it’s also a piece that deserves to be seen by a broader audience. I hope it’s allowed to live on.

Somewhere between these two productions is Laurence Strangio’s version of Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author. It should be a dead play—it’s been worked over by so many student productions and university syllabi that it’s taken on the air of a museum piece. But Strangio’s production was an unexpected delight, both carefully judged and imbued with its own irreverent spirit.

This Six Characters… was an event. For all its self-referential meta-theatricality, Pirandello’s original is still a play. Strangio adds further layers which both problematise and extend the work’s conceit: here we are witnessing two actors and a director prepare for a reading of Six Characters in Search of an Author, before they are interrupted by six actors playing the six characters. The production widens the frame of its ur-text to encompass the site of its staging (quite literally, as it seems every nook of La Mama holds a secret in this work). The performers themselves are integral to the production’s meaning—it’s hilarious to watch Natasha Jacobs complain that Caroline Lee is too old to play her, while casting playwright Adam Cass as the director eventually takes on extra significance when that role shifts towards the ‘author’ of the play’s title.

It’s the integration of the audience that probably invigorates this piece, however. There’s no limp ‘audience participation’—rather, there’s no erection of a fourth wall to begin with. On the night I attended audience members were happily talking to actors throughout, anticipating events, making in-jokes, praising bits of direction. There was still a play occurring somewhere in there, but by acknowledging the essential artifice of the whole shebang we were invited to investigate it from the inside, rather than dissect it as a preserved fossil of another era. Pirandello is dead, for sure, but for two hours here I quite simply forgot that he’d ever been alive.

Baal, writer Bertolt Brecht, translators Simon Stone, Tom Wright, director Simon Stone, performers Brigid Gallacher, Geraldine Hakewill, Luisa Hastings Edge, Shelly Lauman, Oscar Redding, Chris Ryan, Lotte St Clair, Katherine Tonkin, Thomas M Wright, set & lighting design Nick Schlieper, costumes Mel Page, composer & sound designer Stefan Gregory, presented by Malthouse Theatre and Sydney Theatre Company; Merlyn Theatre, CUB Malthouse, April 2 – 23; Random, writer Debbie Tucker Green, director Leticia Caceres, performer Zahra Newman, designer Tanja Beer, composer & sound designer Pete Goodwin, presented by Real TV, Melbourne Theatre Company; Lawler Studio, MTC, May 3 – 13; Six Characters In Search of an Author, based on the play by Luigi Pirandello, concept, direction, adaptation Laurence Strangio, performers Adam Cass, Dean Cartmel, Caroline Lee, Alicia Benn-Lawler, Clare Callow, David Pidd, Natasha Jacobs, Karen Berger, Gabriel Partington, Carmelina Di Guglielmo, Josie Eberhard, lighting design Bec Etchell, design consultant Dayna Morrissey, puppets by Johannes Scherpenhuizen; La Mama Theatre, May 11 – 29

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. 35

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Yana Taylor, Irving Gregory, The Disappearances Project, version1.0

photo Heidrun Löhr

Yana Taylor, Irving Gregory, The Disappearances Project, version1.0

VERSION 1.0 HAS BEEN CREATING AMBITIOUS PERFORMANCE WORKS IN AUSTRALIA SINCE THE 1990S. THEIR LATEST, THE DISAPPEARANCES PROJECT, UNFURLS SLOWLY AND CAREFULLY AS IT INTERROGATES THE LOSS THAT REVERBERATES ACROSS SPACE AND TIME WHEN SOMEONE YOU LOVE DISAPPEARS. PERFORMERS IRVING GREGORY AND YANA TAYLOR TAKE THE AUDIENCE WITH THEM INTO THE TENSE AND SOMETIMES SHATTERING STATE OF MOURNING FOR THOSE WHO REMAIN UNCERTAINLY LOST.

In the company’s characteristic verbatim style, the performance includes excerpts from interviews conducted by version 1.0 with people who had experienced the loss of a loved one through disappearance. The performers share excerpts from stories they gleaned from these interviews, telling them as if they were their own. The authenticity of these narrative fragments in The Disappearances Project is both fascinating and painful to witness.

The first light of Yana Taylor and Sean Bacon’s video projection flickers across a large screen to Paul Prestipino’s emerging soundscape, laden with falling raindrops and trembling cascades of sound. The video, shot through the window of an endlessly, slow-moving vehicle, creates the sense of an exhaustive and inexorable search. Streetlights leak into a dawning cityscape to the incessant sound of dripping water. Rural and suburban streetscapes flitter onto the screen—their familiarity directly implicating viewers in the stories they will hear.

Yana Taylor and Irving Gregory’s miked voices emerge, disembodied—as if suspended in space—until their bodies are gradually illuminated by side lighting. For most of The Disappearances Project, the performers remain seated—upright, alert and tense on wooden chairs either side of the stage. Their near frozen stillness and the nervy soundscape charge the space with a sense of impending danger, tracing a plateau of quiet intensity which creeps to its peak when Taylor’s numbness begins to crack towards the end of the piece. The heaviness of the stories they tell visibly wears away at her, while Gregory maintains a veneer of relative calm.

The syncopated rhythm of the utterances is strung tightly across this ineffable space of mourning. Throughout, the performers’ alternating bursts of monologue bleed into each other’s stories, fragmenting them. Sometimes these stories enunciate glimmers of optimism, but always back-gridded by confusion and slowly building to existential explosions like, “It got to the point where I wanted to go missing, too.”

Taylor and Gregory do not perform fixed characters, but multiple embodiments from a range of experiences of loss. These float across the surfaces of the skin and the resonant timbres of their voices, a performative choice that neatly destabilises the potential for a linear performance structure and without leaning into didacticism. Sustained, disciplined stillness allows for this, as does the weaving of multiple stories into the performative fabric, without the performers embodying any singular identity. Perhaps Taylor and Irving explore a type of traumatised dis-embodiment, where they are rendered motionless due to the incomprehensible size and weight of such loss—a loss that always remains open, without closure.

The terrifying ambiguity of not-knowing displaces the missing persons’ loved ones. This nightmarish loss is always repeating itself in The Disappearances Project by perpetually asking, ‘What if?’ Taylor and Gregory articulate the varying registers of hope, denial, despair and anger that fill this non-place, for the most part with sensitivity and command.

The audience is encouraged to maintain a critical distance for the majority of the performance. At certain points, I wanted to be invited to ‘feel-with’ these stories of loss, rather than hover over them. This is the challenge of verbatim theatre that version 1.0 repeatedly faces with gusto: how can performance move an audience affectively, whilst also moving them to think critically about important social issues? The company managed this particularly well in The Bougainville Photoplay Project (2009-11).

Despite the successes of The Disappearances Project, I’m uncertain as to whether it met that challenge this time.

What The Disappearances Project highlights is a bureaucratic system predicated upon bodies that are fixed, stable and identifiable. The disappeared haunt the loved ones left behind who are punished further by bureaucracy’s inability to cope with the intricacies of human feeling. Where do loved ones of those who have disappeared go for help? Can our system accommodate and support complex human experiences? Whether or not verbatim theatre is an adequate mode for responding to such questions, at the heart of The Disappearances Project is an important plea to rethink the inadequacies of apparent democracy that fails when we need it most.