Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Scenario

photo courtesy of iCinema

Scenario

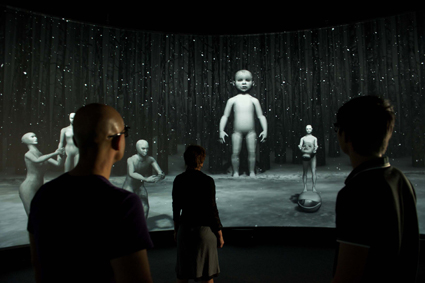

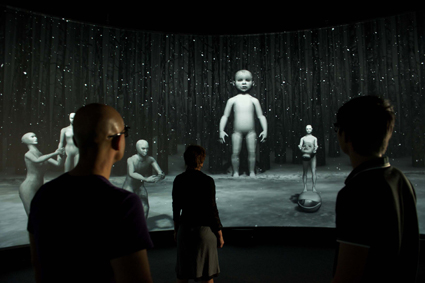

SCENARIO, DIRECTED BY THE ARTIST DENNIS DEL FAVERO, IS A 360-DEGREE, 3D INTERACTIVE CINEMATIC STORY, THE RESULT OF AN EXTENSIVE COLLABORATIVE PROJECT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES. IT PREMIERED AT THE 2011 SYDNEY FILM FESTIVAL ATTRACTING MEDIA ATTENTION BOTH FOR ITS CINEMATIC INNOVATION AND EERIE ATMOSPHERICS.

Edward Scheer, who teaches at the Faculty of English, Media and Performing Arts at UNSW, has followed the evolution of the project and written a companion study. I spoke with Scheer, who believes that Scenario marks a new level of interdisciplinary research in innovative technology. Its more profound value, however, is as a poetic text that taps into archetypal human experience.

an eye as avatar

Scenario opens with a shadowy underworld that beckons the audience to enter and engage with its humanoid inhabitants. In Scheer’s words: “You walk into a 360-degree environment and you see some eyes staring at you. A voice tells you to choose an eye and the eye becomes your avatar. Then a humanoid figure jumps on top of the eye and leads you through a series of underground spaces—spaces of abandonment, one suspects of criminality. You are told that you have to find the body parts of a humanoid child and that these parts have to be returned to the child. One is therefore introduced to a scene of horror but in a gentle way. You are also implicated in the restitution of this violent act.”

The fact that the spectator is not just a voyeur immediately suggests an unusual cinematic experience. Scheer observes that in conventional cinema one is passive in a “cinematic machine that grinds on regardless of your subjective investment.” In contrast, this work opens an interesting ethical space. Scenario has a tracking device which picks up the spectator’s motion. Ultimately, if the body parts are successfully returned to the child, the child is free to walk away. However, if the parts are not returned, an apocalypse descends, ash falls from the sky and there’s a blackout. There are two endings then, each contingent on the active spectator’s participation.

Scheer believes that the unique way Scenario brings together interactive narrative, aesthetics and the use of 3D makes it a world first, one situated within the broader achievements of iCinema itself: an ARC-funded project to look at new software, screening environments, narrative possibilities and spectatorship experiences. The research centre has created the 360-degree Advanced Visualisation and Interaction Environment (AVIE), unique in itself. Over the last ten years some quite remarkable works of new media interactive art, such as Eavesdrop (2004) and There is still time…Brother (2007), have been produced there pushing the boundaries of disciplines and separations between art practices.

Scenario

photo courtesy of iCinema

Scenario

performative media

The question of whether Scenario’s immersive environment fits comfortably within a film festival program leads Scheer to ponder if cinema is actually the right model for such an experimental and interdisciplinary approach. “The cinema-goer is not going to have the same kind of experience that they will be used to. Theatre-goers might be more familiar with the kinds of calling forth of one’s own subjective experience to respond to the material.”

Where then should Scenario be positioned? Scheer calls it “performative media” as it is setting up a mediated space. The humanoid behaviours are modelled on live actors—achieved through the use of motion capture to establish a library of behaviours. There is also the way the spectators have been animated through their involvement in the media. This genealogy resembles media art and crossover performance art. While such a genre reminds cinema of its own performative roots, it remains uncertain if it will have commercial possibilities in the cinema. It has in other fields—the iCinema project has been taken up, for example, by Chinese mining industries.

collaboration as research trajectory

Scheer became involved in the Scenario project several years ago when Dennis Del Favero talked about it in the context of their mutual admiration of the work of Samuel Beckett. “When Dennis told me that Scenario was based on Beckett’s Quadrat, I started turning up to the early iterations of the work.” After giving some feedback, Scheer was formally invited to be the official scribe. It has been a two-year project working with the team with an eye to reporting on compositional and dramaturgical processes, examining its precursors and providing a reading of the work as Scheer sees it.

Scheer describes the collaboration as “a kind of open source dramaturgical project.” The computer scientists rendered the images with Dennis Del Favero. The playwright and screenwriter Stephen Sewell provided the text which changed as the project evolved. Visual designers gave cues to the visual world as it was being formed. These people were sharing their ideas with the computer scientists. “It was a fascinating set of exchanges with Dennis directing but doing so with tremendous generosity. The depth and complexity evolved through these discussions, properly interdisciplinary.”

If the scale of this interdisciplinary collaborative process suggests a new trajectory in the creative research process in the arts, Scheer would point to new media art as a leader simply because of the increasing scope of digital systems requiring a multiplicity of skills to create a meaningful experience for audiences. However, he suspects that a similar modality of collaboration is influencing the way academics engage with artists who traditionally have worked very much alone with their own imagination. Scheer cites his own research on Mike Parr, with whom he has long been in conversation in order to make the artist’s output available to a wider audience. Perhaps it is not just that artworks are changing but the way the academy is engaging with artists. Instead of sitting back and making critical judgements about the value of an art work, academics are now talking with artists, trying the develop a conversation around the work and from that process the reading emerges.

the limits of representation

In his attraction to Scenario Scheer was mindful of the work of Antonin Artaud on whom he wrote his PhD and still someone he considers a massively inspirational force in contemporary aesthetics. “Artaud worked in all of the media of his time and was acutely aware of the confluence of creative forms across different media and the performative, transformative power latent within them.” He believes that Del Favero is clearly engaged in a similar aesthetic, trying to break through to very essential experiences such as trauma, which cannot be encoded within representational media. That which eludes representation was the concern of the “theatre of cruelty.” “What other forms are available that can pursue experiences otherwise fundamentally lost?”

a folktale

Underlying the experience of trauma is something perhaps even more elemental, namely the experience of confinement. I ask Scheer if Scenario stands as a 21st century folktale about the urge to find freedom from one’s received confines. He believes so as it picks up on those universal experiences of loss and abandonment as well as the sense of containment and release. Scenario’s intertext is the Josef Fritzl case, which provides an elusive subtext to some of the work’s narrative. “This was an experience of depravity but also one of containment —seven children confined for 24 years in a cellar beneath the house in Amstetten in Austria. Imagine waiting for 24 years to be released.” Scenario not only tracks the endless experience of confinement but in a form that takes the shape of a folktale.

Scheer considers the tale an ur-story by which he means that the drama is not something happening for the first time; rather, we have seen it all before. He is not alone in thinking this way. Elfriede Jelinek, Austria’s Nobel Prize winning writer sees the Fritzl case as a typical performance of Austria, something that requires no rehearsal because male violence against women is an everyday performance. Scenario taps into that story, “not as something to fetishise but as an archetypal experience that leaks out of the four walls of the basement in Amstetten to be picked up here, perhaps ultimately as an atmosphere of threat, menace, loss and possible recuperation.”

Scenario

photo courtesy of iCinema

Scenario

containment & release

Such an atmosphere is played out as a spatial dialectic, akin to Gaston Bachelard’s “poetics of space.” The spectator experiences the phenomenology of restriction and containment: corridors, tunnels, basements, cracks in the ceiling through which you see the rain coming down, an inner city alleyway. The final scene reveals a frozen lake in a forest and there is a more expansive sense of space. In one version this space closes down. In the ‘happy ending’ version, it opens out and the gigantic figure of the child rediscovers its motility, moving out of the space of confinement towards the space of the forest. “The phenomenology of this for the spectator is very evident in that we experience expansiveness as opposed to restriction, freedom not isolation. Seeing this giant figure moving gives us a sense of hope.” This is important to a reading of so dark a work. At least in one version, the work is ultimately quite hopeful in tracking the relations between self and other.

Edward Scheer Scenario (2011), UNSW/ZKM Press, www.unswpress.com.au; Scenario, director Dennis Del Favero, writer Stephen Sewell; other credits at: www.icinema.unsw.edu.au

This article originally appeared in our July 26 e-dition.

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. web

© James Paull; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jae Hoon Lee, Ha Jo Doe, 2010, digitally collaged photography

courtesy of the artist and Starkwhite, Auckland

Jae Hoon Lee, Ha Jo Doe, 2010, digitally collaged photography

PUTTING ON MY GLASSES, THE LARGE-SCALE DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY OF JAE HOON LEE COMES INTO FOCUS AND I NEED TO STRIDE BACKWARDS IN ORDER TO TAKE IT ALL IN. REMINISCENT OF A GATEWAY TO AN ANCIENT TEMPLE, THE OVERSIZED IMAGES TITLED HA JO DAE 2 AND TREKKING 2 MARK THE ENTRANCE TO UNGUIDED TOURS: THE 2011 ANNE LANDA AWARD FOR VIDEO AND NEW MEDIA ARTS EXHIBITION AT THE ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES.

jae hoon lee, ha joe dae 2, trekking 2 and levitation

To the left appears a landscape of ocean and rocky outcrops. Looking as if they have been constructed chunk-by-chunk, these formations rise from the sea; patterns of indistinguishable similarity emerge, then deviate. To the right, Trekking 2 features a path repeatedly zigzagging, cutting into the sheer, barren mountainside. Someone passing by comments: “God, you wouldn’t want to run off that road.” Spectators stop, pondering where in the world this incredible hillside track might be; until they twig. Or perhaps some of them don’t. Uncannily similar furrows of snow appearing in the crevices are in fact identical. By means of a digital cut-n-paste remix, Trekking 2 takes what is already an awe-inspiring landscape one step further.

Fittingly, Jae Hoon Lee’s Levitation sits between these two digital image giants. The constant ding of a small, tinny yet reverberant bell heralds the exhibition’s entry point. The resonant Buddhist’s bell sound accompanies beautiful textures (in deep ambers, rich chocolates and jade greens) of moss-adorned bricks on screen, slowly rising upwards. Having passed over the threshold, I begin my journey through New Zealander Justin Paton’s curation of award contenders, titled Unguided tours.

Charlie Sofo, 2010-11, mixed materials digital videos

courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of NSW

Charlie Sofo, 2010-11, mixed materials digital videos

charlie sofo, fields 2010-2011

In contrast to Lee’s meditative landscapes, Charlie Sofo’s Fields 2010-2011 is a solid reality check; familiar to all who have ever ventured into the Australian suburbs. Over the past year or so, Sofo has enlivened his potentially boring everyday journeys by gathering like objects. An array of videos, slideshows, as well as the items themselves are clinically displayed: small pebbles collected by way of getting stuck in the grooves of the artist’s shoes, chips of coloured paint, a Google map indicating where condoms and/or condom wrappers have been discarded around Melbourne’s suburbs of Brunswick and Northcote and a box of pastel-coloured cards, each announcing yet another venue (presumably somewhere the artist frequented) has closed down. The premise of Fields 2010-2011 is to attempt to assist the audience in “looking anew at what’s already there.” For one audience member, a small component of Sofo’s work becomes incredibly significant: a video of various neighbourhood cats contains a fleeting image of what she thinks might have been her own cat, who recently passed away. In asking his audience to view tiny scraps of the everyday in a new light, Sofo offers us a way to invest meaning in our banal daily treks.

Arlo Mountford, The lament, 2010-2011, two channel digital animation with 5.1 surround sound

courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of NSW

Arlo Mountford, The lament, 2010-2011, two channel digital animation with 5.1 surround sound

arlo mountford, the lament

Stepping away from the doldrums of familiar life, we are back in the surreal once again. Arlo Mountford’s The Lament is another large-scale digital work—a painting virtually brought to life. This is a fairytale remix of sorts. Taking the two versions of Watteau’s L’embarquement pour Cythere (Embarkation for Cythera) stitched together, the creator then bestows upon this work the breath of life. Taking the time to sit and observe as a peaceful scene unfolds, what becomes noticeable is actually the large degree of activity taking place. Lovers kiss, birds twitter away, a dog rushes around (the spatialised audio space) barking excitedly, waves lap at the shores, couples—flanked by chubby flying cupids—either embark or disembark from the wooden boat, which then encircles the island, partially cloaked by drifting digital mists. For me, this work provides brief solace before returning to hectic city life.

rachel khedoori, untitled

From one natural setting to another, Rachel Khedoori’s Untitled presents a panorama unfolding from the middle, an old technique used in moving imagery, yet Khedoori’s work does not concentrate on this trick. Instead, the symmetry and smoothness of movement help to draw focus towards the endlessness of a lush bush-scape, peeling outwards forever. A group of kids gather to watch, emitting a collective “whoa…”

David Haines and Joyce Hinterding, The Outlands 2011, projected real time 3D environment utilising the Unreal Engine; additional sound Rosy Parlane, Michael Morley and Danny Butt

courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of NSW

David Haines and Joyce Hinterding, The Outlands 2011, projected real time 3D environment utilising the Unreal Engine; additional sound Rosy Parlane, Michael Morley and Danny Butt

david haines and joyce hinterding, the outlands

I follow the kids and their parents into The outlands, David Haines and Joyce Hinterding’s game environment, knowing it’s going to be a while before I get my turn. As I enter the space, The outlands creaks with sounds from the shadowy vegetation, created by New Zealanders Rosy Parlane, Michael Morley and Danny Butt. With only two controller “sticks” (joysticks with large dead twigs attached), diplomatically sharing these between a large group of kids calls for other forms of interaction. Without hesitation, some of them crouch down in front of the floor to ceiling projection, pretending to be prowling animals and then slowly swaying from side to side as if aboard a vessel traversing this imaginary landscape. Hovering above a blue-tinged black swamp, surrounded by low-lying branches and deadwood, we fly towards the towering rock formations. The kids were happy to improvise their own interactivity but I wanted to demand much more from the winner of the $25,000 acquisitive Anne Landa Award for 2011. What I desired was a greater degree of immersion (in both this work and also in the overall scope of the exhibition), with fewer works presented as if they were paintings or photographs, merely shifted into the video realm.

Ian Burns, 15 hours v4, 2010, found object, kinetic sculpture, live video and audio

courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of NSW

Ian Burns, 15 hours v4, 2010, found object, kinetic sculpture, live video and audio

ian burns, various

While at first glance it didn’t look like much—just a random bunch of old junk cable-tied and taped together—the pièce de résistance of Unguided tours was the work of Ian Burns though I’ll admit it did take me some time to comprehend what was actually going on. Commencing with Well Read, homage to the road trip and car culture, your eye wanders these sculptures of second-hand odds and ends, eventually settling on two analogue TV screens strapped to the front. Switching between different camera angles, a car drives along open roads, blue sky above. The driver, a peroxide blonde Ken doll, bobs along as the wheels of the car spin…on what turns out to be a seven-inch of Time Bandits’ “Endless Road.” These unremarkable objects are cleverly pieced together to create an illusion found regularly on our screens.

With each of his works in the exhibition (including From orbit displayed in the gallery’s entrance), Burns takes the lid off various movie-like scenes of travel we believe in and commit to so wholeheartedly, exposing the underbelly of smoke and mirrors. Standing in the passageway between Makin’ tracks and 15 hours v4 (an endless view from an aeroplane window over the plane’s wing), I overhear a 20-something comment as he passes by that “it’s just shit really, I don’t get it.” The combination of this remark and Burns’ works illuminates the real crux of Unguided tours. While there may be a general preconception that the digital realm is all about instant gratification, these works require a time commitment. Their messages are not immediate.

From familiar digital suburban-scapes through to pristine pixel wilderness, while none of these works demands attention, you are only granted insight if you take the time to contemplate. This is the same headspace one enters when travelling solo through unfamiliar countries and cultures: precisely what each of these artists must have done at some point, in order to produce these offerings. But while the “touring” aspect of the exhibition works, I am less convinced by the “unguided” framing since, regardless of whether or not a conventional narrative is present, many of the works still portray a semi-predictable journey, one that is predetermined by the digital tools they employ. Nevertheless, this concern is of far less importance than the feeling that I depart with—I have been reinvigorated, as if returning from a holiday, and I haven’t even left town.

Unguided tours: Anne Landa Award for Video and New Media Arts, 2011, Art Gallery of NSW, May 5-July 10; www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au

This article first appeared in our July 26 e-dition.

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. web

© Somaya Langley; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Within and Without

photo Heidrun Löhr

Within and Without

LAST YEAR’S TINY STADIUMS FESTIVAL FEATURED A SITE-SPECIFIC WORK OF NOTE. APPLESPIEL, A COLLECTIVE OF FORMER UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG STUDENTS, TOOK UP RESIDENCE IN SYDNEY’S ERSKINEVILLE TOWN HALL AND, OVER THE COURSE OF 12 DAYS, TRANSFORMED A COLOURFUL CARDBOARD MINIATURE OF THE SUBURB’S MAIN STREET INTO A STRANGE NEW VERSION OF ITSELF. INVITING AUDIENCE MEMBERS TO PLAY THE ROLE OF HANDS-ON URBAN PLANNERS AND ENGINEERS, THE COLLECTIVE PLANTED MONEY TREES OUTSIDE THE CAFE, BROKE GROUND ON A NEW AQUARIUM AND CUT THE RIBBON ON THE BATCAVE, A BATMAN-THEMED MUSEUM.

I was reminded of Applespiel’s Erskineville recently when I visited Within and Without’s Manila. A collaboration between the Philippines’ Anino Shadowplay Collective and local artists Valerie Berry, Deborah Pollard and Paschal Daantos Berry, Within and Without is a hybrid work of performance and installation art that is laudable for its ambition if not always for its achievement. More than a mere city street, it features a sprawling miniature cityscape constructed not from coloured card but recycled detritus: cardboard boxes, unloved toys, curious knick-knacks and old tangled fairy lights, the lot held together with masking and gaffer tape.

While I have spent a little time in Erskineville, I have never been to Manila. My impressions of the city were formed by Alex Garland’s 1998 novel The Tesseract, which paints it as a sprawling nightmare slum and John Safran’s TV series Race Relations, where the show’s host famously had himself crucified on what were pretty flimsy thematic and narrative grounds. In Within and Without, Manila is presented as a city defined by its own ongoing, contested construction: the US rebuilding of Manila post-WWII, the Ayala family’s construction of the affluent Makati district and Imelda Marcos’ Martial Law-era beautification projects are all mentioned during the show. The most devastated allied city after Warsaw, Manila is here imagined as one that has not only grown out of the debris, but has actually been constructed from it.

Within and Without

photo Heidrun Löhr

Within and Without

For all the aptness of this metaphor, however, there otherwise remains a disconnect in the piece between its form and content. As you are shown around the cardboard city by a performer-cum-guide—you see only parts of the installation during any given performance and would need to attend maybe two or three times in order to experience the whole thing—this disconnect becomes ever more apparent. From the arts-and-crafts construction of the city to the wide-eyed, forced-grin delivery of the tour guides, the form is instantly reminiscent of children’s television programming. The content however covers everything from WWII and the ensuing dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos to tours of the city’s gay and red-light districts—“I am sure we can find you a nice ladyboy here, ma’am-sir!”—and is decidedly more complex than either the cardboard city, or the piecemeal exposure available to it on any one visit, would suggest.

While occasionally charming, this disconnect between form and content doesn’t really seem to reveal anything about either. While providing a more or less arbitrary framework for us to learn about Manila, the cardboard-and-egg carton city does not appear to reflect or reveal anything about the flesh-and-blood one, which itself seems like a strange choice of subject for anyone looking to more fully exhaust the possibilities of this form. It is a poor critic who presumes to tell an artist that they could improve their work by doing something entirely different. But Applespiel’s Erskineville keeps coming to mind. It seems to me that a Playschool-ish approach is perfectly suited to the creation of a wholly imagined city, or an amalgamation or reinvention of an already existing one, and that such miniaturisation is a perfect way to get people thinking about urban planning, spaces for living in or the relationship between geography and community. As a way of getting people to think about what the program notes call “the horrors of history” it seems indirect and ineffective. We are left to ask ourselves one of two questions: “Why Manila?” or “Why in miniature?”

Garland’s The Tesseract provided such a striking representation of the city—I cannot, obviously, speak to its accuracy—because it employed a narrative form that was well-suited to its author’s idea of the place: a temporally dynamic postmodern structure for a spatially dynamic postcolonial city. It is arguable that the aforementioned disconnect between Within and Without’s form and content itself mirrors the manifold divisions inherent in what the artists, in their aforementioned program notes, describe as “the way we collectively see [the city]:” the divisions that exist between East and West, Christianity and Islam, rural and urban, rich and poor. Tellingly, two of the words the artists choose to describe the city are “schizophrenic” and “chaotic.”

Which is why the soundscape that opens the performance, taking place before we have even seen the cardboard city, is more effective than what follows it. Entering a dimly-lit space and asked to don the blindfolds they have been given in the foyer, the audience are treated to a densely layered sound design that includes everything from barking dogs and construction work to loud-mouthed hawkers and a discordant dirge of car horns. The key word here is ‘layered.’ Where the rest of the work is characterised by its own internal divisions, this opening sequence gets somewhat closer to approximating the messy, communal and continuous process that is the construction, not only of a city like Manila, or even an inner-city suburb like Erskineville, but of any space in which we must live. In doing so, it gets somewhat closer to actually approximating what a history is, too. It gives us a palimpsest.

Performance Space and Blacktown Arts Centre: Within and Without, artists Paschal Daantos Berry, Deborah Pollard, Valerie Berry, Anino Shadowplay Collective (Datu Arellano, Andrew Cruz, Don Maralit Salubayba), guest artists David Buckley, Kenneth Moraleda, Melanie Palomares, lighting designer Jack Horton; Blacktown Arts Centre, Sydney, June 23-July 2

This article was first published as part of the July 26 e-dition.

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. web

© Matthew Clayfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ella Mudie

photo courtesy of the author

Ella Mudie

Bio

My father’s a painter so I grew up with art and the smell of oils still takes me back to my childhood. First and foremost though I’ve always been a big reader, which led me to enroll in a BA at the University of Sydney where I majored in English and wrote an honours thesis on the maverick boy poet and hoaxer Thomas Chatterton. I also took some postgraduate studies in journalism and among the climate controlled towers of UTS found my niche in print features and arts writing. Some early gigs such as a catalogue essay for a painter friend snowballed into bigger things, eventually leading to features for The Age and other papers to articles and essays in magazines and journals including Meanjin and the Griffith Review. My interests are broad but the visual arts are a longtime passion and common thread running through much of my work. I find myself mostly drawn to writing about photomedia, installation and conceptually driven practices.

Exposé

My desire to write comes mainly from curiosity, I think. Journalism opened my eyes to the importance of writing within a social context and why giving a voice to real, everyday people matters. When it comes to visual arts writing specifically, I’m most interested in how writing introduces a pause, interrupting the passive consumption of images, objects and ideas and instead feeding a sustained contemplation which, in order to be shaped into a text, requires reflection and interpretation. Art writing can’t be rushed, it gestates over time and represents a subversive gesture in this speedy capitalist culture where time is money. I enjoy how good artworks reveal something new each time I revisit them, leaving the process somewhat open-ended.

Freelance writings assignments can be relatively short in length so I like to counterbalance this by immersing myself in bigger topics over longer periods of time. Sometimes they turn into stories, sometimes they don’t. I’m currently researching the influence of Surrealism on the development of the psychogeographical novel, from André Breton’s Nadja to the elegiac meanderings of WG Sebald. I’m enjoying the indeterminate nature of these stories. In my own work I always strive for clarity yet curiously I often start with a point of confusion—something perplexing which somehow the process of writing works to unravel and resolve.

Recent articles for RealTime

studio vertigo: fiona mcgregor

RT99 night works: bec dean, nightshifters, performance space

RT98 sino-supernova: the big bang, white rabbit gallery, sydney

RT94 deepening degrees of subjectivity: brad miller, james charlton, simon barney, artspace

studio special effects: sam smith

other writings

between art and garbage, meanjin

dream it, build it, the age

the spectacle of seismicity: making art from earthquakes, leonard journal, mit press

the alpha pre-schoolers, sydney morning herald

building conversations: architectural photography as discourse, afterimage journal of media arts and cultural criticism

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. web

© Ella Mudie; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Chris Reid

photo courtesy of the author

Chris Reid

Bio

As an undergraduate in South Australia, I studied Political Science and History and have made a 30-year career in educational administration — “herding cats”. More recently I completed a masters degree in art history and had a brief taste of teaching in that field. After 5.00pm, I’ve always been an arts addict. I write about both art and music but I’m neither an artist nor a musician. My life is split between three worlds — art, music and education. Every interstate or overseas trip is a cultural (as well as socio-political) excursion.

Exposé

I began writing about art in 1992 for Adelaide-based visual art magazine Broadsheet, published by the Contemporary Art Centre of SA, and regularly wrote exhibition reviews and artists’ profiles for Broadsheet for many years. From the outset, I always tried to write from the position of the engaged viewer, rather than the expert, and to re-present the spectacle to the reader. I also regularly write catalogue essays for artists and in the 1990s contributed to other art magazines such as Art Monthly Australia.

I was first invited to write for Real Time in 1995—a piece on an Adelaide contemporary music ensemble—and, for Real Time, I have written much more about music than art. In covering musical performances or in writing CD reviews, I try to write as an engaged listener.

Since the art and music I cover is typically new and often groundbreaking, I try to convey the concept to readers in a way that allows them to get a feel for the work, form their own view and take from it whatever inspiration they can. I try to leave my tastes and assumptions at home and act as an informative conduit rather than an evaluative judge. In a globalising and rapidly changing art/music world, it’s important to write sympathetically as well as analytically. I immerse myself in the work to find its poetics, its maker’s spirit, and often feel I’m entering a new world of ideas each time. I feel privileged to be able to write about the work that I do, given the effort that artists, curators, composers and musicians put into it and the impact it can have on audiences. The work might only be seen or heard by a few people, so the text that describes it must document it well to ensure that it fulfils its potential and endures.

And writing keeps me sane.

Recent articles for realtime

earbash decibel: disintegration: mutation

earbash toplogy: difference engine

RT101 sa art: present tense: cacsa contemporary 2010: the new new

RT100 intimate warnings: vocal thoughts, cacsa

RT93 music like speech: elision in session, melbourne

RT93 music that needs to be seen: soundstream adelaide new music festival

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. web

© Chris Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

our other indigenous culture

It might be one box on the Census (coming soon, August 9) but Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures are very different from each other, to the point where the latter is sometimes called “Australia’s other Indigenous culture” (press release). Over the next four months, Queensland’s major arts organisations at the Cultural Centre, South Bank in Brisbane, are joining forces to present The Torres Strait Islands: A Celebration, showcasing the diversity and vibrancy of historical and contemporary arts and culture of Torres Strait Islander Australians. The program encompasses an exhibition, Awakening: Stories from the Torres Strait at the Queensland Museum, Strait Home at the State Library and Land, Sea and Sky: Contemporary Art of the Torres Strait Islands, at the Gallery of Modern Art. The last is the largest and possibly most significant exhibition to date of contemporary art by Torres Strait Islander artists anywhere in the world and it includes dance objects, prints, film, video, textiles, ceramics and installations drawn from the Queensland Art Gallery’s extensive collection of works by Torres Strait Islander artists as well as key loans and commissioned works. The artists include Dennis Nona (RT69) and Destiny Deacon (RT66). Land, Sea and Sky: Contemporary Art of the Torres Strait Islands, Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane; http://qag.qld.gov.au

Worldhood

photo Chris Herzfeld

Worldhood

premieres aplenty

Two weeks ago (July 12) we mentioned Lisa Griffiths and Craig Bary’s new work Side to One, which premieres at the Adelaide Festival Centre on July 27. Next month the venue will play host to another world premiere, Worldhood, a collaboration between choreographer Garry Stewart (see his profile in RealTime Dance) and Adelaide artist Thom Buchanan. While dancers from the Australian Dance Theatre and the Adelaide College of the Arts move, Buchanan will create dramatic charcoal drawings live on stage: “his frenetic mark-making, fuelled by hundreds of visual decisions per minute, recalls artists like Frank Auerbach, Alberto Giacometti and Cy Twombly” (RT67). Later in August, the Centre will also present the Australian premiere of Gabrielle Nankivell’s solo performance I Left My Shoes on Warm Concrete and Stood in the Rain. Nankivell has spent the past decade working with some of Europe’s groundbreaking choreographers; on this occasion she is collaborating with composer Luke Smiles and Bluebottle, whose striking designs have been featured in the work of Jenny Kemp (RT99), Balletlab (RT93) and Michelle Heaven (Dance Massive), among many others. The show is part of A Mini Festival of New Performances, copresented with Mobile States and features four shows in five days including Vivaria by Sam James (reviewed in RT97, artist interview in RT91), En Route by One Step At a Time Like This (RT94, back when they were still bettybooke) and The Harry Harlow Project by Insite Arts (RT95). Worldhood, Aug 10-13, I Left My Shoes on Warm Concrete and Stood in the Rain, Aug 24-27, part of A Mini Festival of New Performances, Aug 23-28, Adelaide Festival Centre, www.adelaidefestivalcentre.com.au

Fuse, STRUT Dance

photo Eva Fernandez

Fuse, STRUT Dance

motion and emotion

There’s more dance on offer over in the west, where PICA is presenting STRUT Dance (see all of our previous reviews of STRUT in the RealTime Dance Archive), as part of its performance program. (In May they presented My Darling Patricia’s Africa RT94 and this month they presented Team Mess’s This Is It.) Directed by Jonathan Buckels (RT86), Fuse is a full-length dance work based on the relationship between two people: “through the cycle from strangers, to friends, towards cohorts, through dependents and on to parasites. Love can give you the chance to change almost any facet of yourself in order to fit the needs of the object of your desire. But if your love is reciprocal, shouldn’t they also change for you? Will this create positive perpetual motion, or a destructive vicious circle? Can those within the relationship tell which of these paths they are on?” (website). Buckels and Rhiannon Newtown (RT94) will be dancing the answer. STRUT Dance, Fuse, Aug 26-Sept 3, PICA, www.pica.org.au

Sweet Bird andsoforth

photo Grant Sparkes-Carroll

Sweet Bird andsoforth

sweet bird of youth

The Australian Theatre for Young People will present the world premiere of German playwright Laura Naumann’s play Sweet Bird andsoforth. Translated by Benjamin Winspear (RT62), and directed by Laura Scrivano, the play starts with a farewell party on the edge of town; but while the group is trapped in an isolated suburban wasteland, their Gen Y dreams transcend any location. Billed as an “original, unexpected and blackly comic story of a group of friends caught between adolescence and adulthood,” the play won Naumann the Munich Prize for Young German-Language Drama (press release). Australian Theatre for Young People, Sweet Bird andsoforth, Aug 18-Sept 10; www.atyp.com.au

Thrashing Without Looking

photo Heidrun Löhr

Thrashing Without Looking

performance goggles

If you missed Aphids’ work Thrashing Without Looking at LiveWorks, Performance Space, then you might like to get to Melbourne soonish. Divided into two groups the audience watch, create, perform and control their environment in this experiential work. Video goggles are provided to the first group who watch and interact directly with a series of bold transformative images unfolding live in front of them as the second group help create the imagery. Fiona McGregor wrote: “It provoked all sorts of thoughts about the modes of disembodied communication we engage in now—televisual, internet—how trust and agency are still called upon and how intense and liberating is the sense of touch. There were moments of alienation, boredom, confusion, anticipation, humour and the ending was surprisingly tender. I didn’t want to leave” (RT101). Aphids, Thrashing Without Looking, Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall, Aug 3-7; http://aphids.net

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Eden Falk, Emily Browning and Rachael Blake, Sleeping Beauty

FOR ALL THE HOOPLA THAT HAS GREETED IT, BOTH AT CANNES AND THE RECENT SYDNEY FILM FESTIVAL, NOVELIST JULIA LEIGH’S DIRECTORIAL DEBUT IS A STRANGELY LIFELESS AFFAIR. MARKETED AS AN EROTIC REIMAGINING OF THE CLASSIC FAIRY TALE AND BEARING A STAMP OF APPROVAL FROM LEIGH’S CINEMATIC MENTOR JANE CAMPION, SLEEPING BEAUTY MIGHT HAVE BEEN MESMERISING. UNFORTUNATELY IT PERTURBS MORE THAN IT ENGAGES, ELLIPTICALLY GESTURING TOWARDS A SIGNIFICANCE THAT IT STEADFASTLY REFUSES TO REPRESENT.

The somnambulist of the title is Lucy (Emily Browning), a 20-something university student. Juggling various casual jobs as a waitress, photocopy clerk and participant in medical experiments, she breaks up her brittle routine by picking up businessmen in bars or visiting her bookish friend Birdmann (Ewen Leslie), an alcoholic misfit with whom she shares some measure of platonic intimacy, the pair united in mocking a comfortable middle class existence from which they seem excluded.

Behind in the rent in her shared house, Lucy answers an advertisement for a position requiring “mutual trust and discretion” from Clara, an imperiously coiffed madam (Rachael Blake). Initially, wearing little but her knickers, she is required to provide silver service to three extremely wealthy old men (Peter Carroll, Chris Haywood and Hugh Keays-Byrne), but is soon offered a ‘promotion’: to lie naked in a drugged sleep while each man does what he will with her. Lucy glibly accepts, blithely asserting that “my vagina is not a temple” to Clara’s oddly prudish assurances that no sex will ensue.

Leigh has said that she strove to create a “tip of the iceberg” feel to the film and indeed, at times it seems to consist entirely of immaculately gleaming surface. Shot in Sydney, the film is bereft of any clear indicators of place, what action there is unfolding within anonymous public spaces or bland, depersonalised private ones. Although many scenes are inflected with unmistakably local touches, for all intents and purposes it could be set anywhere in the western world, Leigh striving to hit an allegorical note unmoored from historical reality.

The script draws heavily from literary touchstones, the tender but impotent nostalgia of the first old man self-consciously echoing Gabriel Garcia Marquez’ Memories of My Melancholy Whores and Yasunari Kawabata’s House of the Sleeping Beauties, both cited by Leigh as important influences. However, her heroine’s determined complicity also recalls Angela Carter’s supernatural version of the tale “The Lady of the House of Love.” Like Carter’s vampiric protagonist, Lucy is wilfully passive, “indifferent to her own weird authority, as if she were dreaming.” In this sense she might be considered what Carter referred to as a “Sadeian Woman,” Leigh using her character’s self-destructiveness as a means of tracing the logic of sexual and economic exploitation. It’s hardly accidental that once she obtains her first payment Lucy burns the money.

Rachael Blake, Emily Browning and Peter Carroll, Sleeping Beauty

Sleeping Beauty is a visually sumptuous and technically assured film. Julia Leigh has benefited from the strong support of an experienced team, including production direction by Annie Beauchamp (Disgrace, Praise), editing by Nick Meyers (Balibo, The Bank) and exquisite cinematography by Geoffrey Simpson (Romulus, My Father, Shine). Their talents combine to lend the film, particularly the scenes in the lavish mansion in which Lucy’s slumberous encounters occur, a plush but austere beauty.

Leigh’s penchant for immaculately composed shots, held well beyond the requirements of narrative, conjures a mood of brooding watchfulness reminiscent of Michael Haneke’s brilliant Hidden (RT75). In that film the director meticulously crafted an air of patient stillness, the implacable, unseen camera reversing the historical power dynamic of French colonialism with eventually devastating results. Sleeping Beauty is similarly deliberate, the camera being as unwavering on the withered bodies of the men as on Browning’s naked form. Although it may be at times uncomfortable to watch, Leigh seems willing to only go so far—her depiction of the sole instance of outright physical abuse (a cigarette burn) is constructed to obscure what it simultaneously depicts, an approach characteristic of the rest.

It may be because of this that Sleeping Beauty frustrates. The enigmatic aura that Julia Leigh carefully nurtures is both painfully affected and needlessly obscure, squandering an intriguing scenario by lapsing into cryptic torpor. Worse, at the screening I attended, a number of moments weighted with an otherwise overbearing seriousness elicited, presumably unintended, laughter. Although not without its pleasures—the performances, particularly that of Browning, are excellent—it is difficult to be seduced by Sleeping Beauty, the film aiming to make a much greater impact than it seems capable of delivering.

Sleeping Beauty, writer-director Julia Leigh, actors Emily Browning, Rachael Blake, Ewen Leslie, Peter Carroll, Chris Haywood, Hugh Keays-Byrne, cinematographer Geoffrey Simpson, editor Nick Meyers, production design Annie Beauchamp, sound design Sam Petty, composer Ben Frost; Magic Films, 2011; www.sleepingbeautyfilm.com/

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. web

© Oliver Downes; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Belinda Raisin, Dead Cargo

photo Leesa Connelly

Belinda Raisin, Dead Cargo

METRO ARTS HAS ALWAYS BEEN A HOME FOR INDEPENDENT PRODUCTIONS IN BRISBANE, BUT SINCE LIZ BURCHAM’S APPOINTMENT AS CEO IN 2006, THIS POSITION HAS BEEN BOTH CEMENTED AND STRENGTHENED. BY PROVIDING FUNDING SUPPORT AND PAYING ACTORS DURING REHEARSALS (AFTER WHICH IT’S INTO COOPERATIVE SHARING ARRANGEMENTS), BURCHAM HAS TRANSFORMED METRO INDEPENDENTS INTO A VITAL AND COHESIVE PART OF THE CITY’S PERFORMANCE SCENE. BUT WHY KEEP THE FAITH?

In an interview with Katherine Lyall-Watson, Brisbane icon Eugene Gilfedder lays out a manifesto: “Independent theatre chooses YOU. It says, come to me, do as I say, work many long hours without wages, get wound up with nerves—you’ll love it. Independent theatre is the HEART and I’ve been honoured to have had so many wonderful people who have been likewise CHOSEN.”

dead cargo

But as an audience you don’t necessarily have to love it. In fact, the first production for the year, Dead Cargo by Tim Dashwood and Nigel Poulton, aroused emotions in me ranging from boredom, disappointment, utter confusion, outrage, repulsion and homicidal feelings towards the protagonists that they also apparently harboured for each other, accompanied by a savage glee that I was experiencing all these emotions. This had the taste of the real thing. It also proved an extraordinary introduction to Meyerhold’s Biomechanics, which he developed in mid-20th century Russia, and which Nigel Poulton now teaches in 21st century Brisbane.

There was one simple action. Three clowns performed riffs on that good old standard prop, the suitcase, fighting for possession until the most recently arrived (and most innocent?) spontaneously gives it away because someone “needs it more,” and then gets himself killed into the bargain for breaking the rules of this closed society. The most absurdly inspired piece of clowning took place at this point as Deb Sampson put one foot in a bucket of water in order to avoid leaving her watery domain to commit the murder. Otherwise, time (itself something of an obsession) was spent in non-stop demonstrations of an infinite capacity to talk past each other.

In my opinion, this aspect of the work was an unintentional red herring. Dashwood and Poulton might have been better off learning from the new existential comedy of British playwright Will Eno rather than flagging the Absurdist theatre of the mid-20th century. In any event, promoting Dead Cargo as contemporary absurd theatre was a bit of a misnomer. Surely—and on the evidence of this production—Meyerhold was closer in time to Expressionism and to the concepts of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty. Certainly I was most moved by the stylised recounting by each of the performers at different times of a refugee’s flashback childhood memory involving soldiers “with angry eyes,” a seeming massacre, and their subsequent lonely fall into an abyss of cultural displacement. This was passionately conveyed by the actors and coupled with Jason Glenwright’s lighting and Phil Slade’s sound design, Dead Cargo revealed itself in the end to be a very thoughtful and powerful production.

Eugene Gilfedder and Finn Gilfedder-Cooney, Empire Burning

photo Stephen Henry

Eugene Gilfedder and Finn Gilfedder-Cooney, Empire Burning

empire burning

Eugene Gilfedder’s The Fiveways was the bright gem in the 2009 Brisbane Festival (RT87). His latest offering, Empire Burning, has even more profound scope as political allegory with multiple overtones conveyed in the heightened language of a blank verse that was marvellously contemporary and played seamlessly to its audience. I periodically found myself closing my eyes just to relish the words. This was also a tribute to a cast consisting of some of Brisbane’s finest actors who took on the text as their own. This was a theatre of ideas that was as visceral as it was cerebral, requiring us to mentally jump with the alacrity of Gilfedder’s own agile facility to gather worlds.

The piece originated in 2005 when Gilfedder was reading about the influence of the Roman playwright Seneca on the age of Shakespeare (think the graphic violence of Timon of Athens) and at the same time brooding about the so-called war on terror abroad (think Abu Ghraib) as well as attacks on democracy and civil liberties at home. Seneca was also a renowned philosopher and tutor to the young Nero who was named emperor in 54AD and, as legend has it, fiddled while Rome burned. This all became enmeshed in an intense poetic fantasy about an ur-empire in decline rather than keeping to strict historical parallels. This is clear when “we none of us know / What people these are that come through the flames.” The captured terrorist (Dan Crestani) is inarticulate, cannot speak the language…there is nothing to designate him as other than Other. These self-immolating strangers hint at a mysterious interpenetration of the human and supernatural worlds, a mood further enhanced by Geoff Squires’ lighting and Freddy Komp’s projections. Gilfedder recreates something of the feel of classical tragedy with these mysterious epiphanies and symbolic revelations of the divine, however strongly parodic their final delivery in this piece.

There was much to praise in the performances: Gilfedder portraying Seneca as a warm and decent man (especially evident in early scenes with his son), a humanist and democrat increasingly baffled and ultimately overwhelmed by the madness of his times; the cold choice of madness itself a valid response to the times embraced with beautifully modulated nonchalance and fierce humour by Finn Gilfedder-Cooney as Nero; the saturnine ease and contemporary chutzpah of all the conspiring senators; and the power-hungry, domineering Agrippina, mother of Nero, played with flamboyant abandon by Nikki-J Price. This was a work of gripping energy and relevance that has the legs for a lot more miles.

Dead Cargo, director Nigel Poulton, writers Tim Dashwood, Nigel Poulton, performers Nigel Poulton, Tim Dashwood, Belinda Raisin, Deb Sampson, sound design Phil Slade, lighting Jason Glenwright, Metro Arts, Brisbane March 9-26; Empire Burning, writer, director Eugene Gilfedder, performers Finn Gilfedder-Cooney, Eugene Gilfedder, Nikki-J Price, Dan Crestani, Damien Cassidy, Steven Tandy, Sasha Janowicz, Michael Futcher, sound design John Rodgers, Ken Eadie, lighting Geoff Squires, costumes Jess Staunton, visuals/projections Freddy Kemp; Metro Arts, Brisbane May 13

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. web

© Douglas Leonard; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

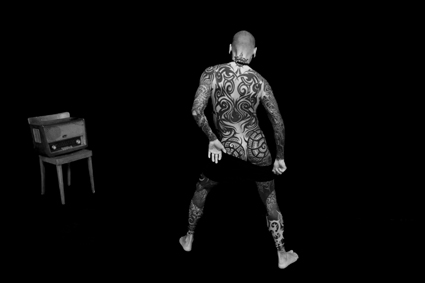

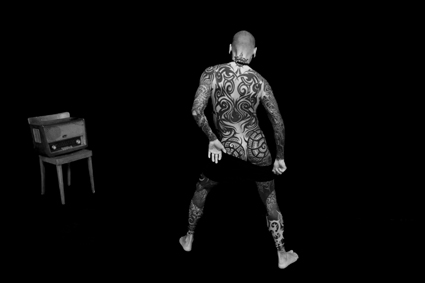

Didi Bruckmayr, The Black Box Sessions

photo Alex Davies

Didi Bruckmayr, The Black Box Sessions

YOU ENTER A DARK CORRIDOR ALONE. IT’S AN ALL ENVELOPING DARKNESS THAT SEEMS TO SUCK THE BREATH FROM YOU, BUT BY SLIDING YOUR HAND ALONG THE WALL YOU CAN NAVIGATE TOWARDS THE SMALL LIGHT THAT EVENTUALLY APPEARS IN THE DISTANCE—A PEEPHOLE. PEERING IN YOU SEE A SMALL SCREEN DISPLAYING INFRARED CCTV FOOTAGE OF A ROOM. SOMEONE IS ALREADY IN THE ROOM OVER IN THE CORNER WITH THEIR BACK TO YOU. YOU WONDER, “WHO IS THAT LOOKING INTO THAT PEEPHOLE?”

Some people recognise themselves faster than others and this moment of realisation is almost enough in itself. Looking at yourself looking at yourself—seeing one ‘you’ who is thinking about how it is seeing this other ‘you’—creates a phenomenological mirror of infinity that leaves you gasping. But there is more to Alex Davies’ The Black Box Sessions. You are here to see a show that will be performed in this room, just for you.

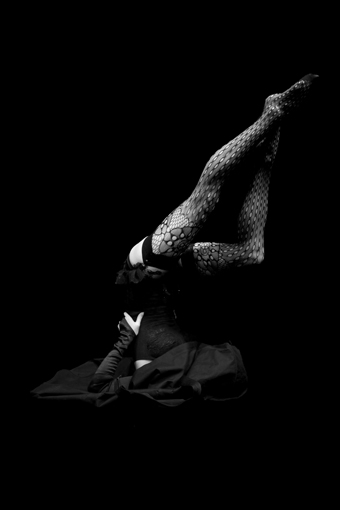

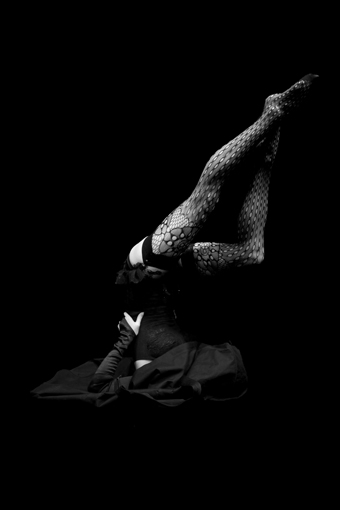

Annabel Lines, The Black Box Sessions

photo Alex Davies

Annabel Lines, The Black Box Sessions

I peeped at three acts randomly selected from the 30 performances by Australian and international performers. The lovely, leggy Annabel Lines escaped gracefully from a sack to hula-hoop for me; Didi Bruckmayr revealed his fully tattooed corpus in a rough striptease; and Patrick Huber tried to tell me, in his rambling way, about what a great actor he is. The performances are not always astounding and some are looser and more haphazard than others. The most successful moments occur when actions reinforce the sense of the darkened space and the performance is directed specifically to you. But even when the illusion is faltering, the sense that the action is taking place just behind you is hard to shake, heightened by the well-spatialised audio. The compulsion to look behind is strong, but when faced with the void you turn back to the screen for the mediated comfort of yourself and your performer.

The Black Box sessions continues Davies’ explorations into mixed reality environments first successfully realised in his installation Dislocation (2005, see RT70 and RT88). In this earlier work the room is visible in both the virtual/screen and real worlds, and the apparitions don’t tend to do much that is out of the ordinary. They are looking at the work as you are with the occasional anomaly of a barking guard dog or an argument. This mundanity creates a kind of ruptured reality. In The Black Box Sessions, the disorientation created by the utter darkness—the inability to match the screen view with the physical space—and the overlaid construction of the peep show creates a much stronger sense of entering a consensual fantasy. This is reinforced by Davies’ extension of the peepshow premise out in the foyer where a monitor placed on the gallery attendant’s desk shows CCTV footage of the waiting room (with you in it) and the adjoining dressing room with the performers undertaking their pre-show preparations. It’s a nice touch though easy to miss if you don’t have to wait too long to enter the corridor.

Like all Davies’ works, The Black Box Sessions is impressive from a technical perspective as the real-time video interaction is seamless and its complex machinations completely invisible. Davies’ playful attention to detail really invites you into this fantasy world. However this finessing reinforces the central wonder—first established in Dislocation and iterated here—of the perceptual and conceptual mind-bending that occurs as you try to reconcile your position in this world, being simultaneously inside and outside yourself. You will never look at yourself in the same way again.

Alex Davies, The Black Box Sessions, performers Celia Curtis, Annabel Lines, Chas Glover, Las Venus, Patrick Huber, Didi Bruckmayr, Roland Penzinger, Justin Shoulder, Matthew Stegh, Scott Sinclare; UTS Gallery, Sydney, May 31-July 15

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. web

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

from organisation to institution

Like the Performance Space in Sydney several years ago, Performance Space 122 in New York is experiencing growing pains. But whereas its namesake chose relocation, PS122 chose renovation. In the meantime, however, it will be a bit like a government in exile, presenting performances in London as well as co-presenting work with Crossing the Line, an innovative interdisciplinary festival in New York. The new building comes not long after PS122’s 30th anniversary, adding to the sense of a shift from being a mere venue or organisation to something of an institution. Indeed, the list of participants at the anniversary party reads like a roll-call for the avant-garde: The Wooster Group, Split Britches, Mabou Mines, Philip Glass, Big Dance Theater, Elevator Repair Service etc. It will be interesting to see how artistic director Vallejo Gantner balances this inheritance with the need for innovation and experimentation. For more information, see Claudia La Rocco’s article in the New York Times. PS122, www.ps122.org

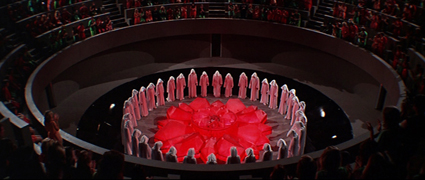

The Carousel, Soda_Jerk

video still courtesy the artists

The Carousel, Soda_Jerk

remix: the remake

You’ve seen the sequel (RT83), now see the director’s cut! The Sydney-bred, Berlin-based sisters of Soda_Jerk (Dominique and Dan Angeloro) will be premiering Pixel Pirate 2: The Director’s Cut (2011) at the Revelation Perth International Film Festival on July 22. Billed as a work that “reimagines the role of cinema, the function of entertainment and lays down the gauntlet for all who want to uphold traditional notions of image and sound” (website), it will appear alongside four short films by Tony Lawrence, including Goldtop Mountain, Girl on Fire, Monsignor Blood and From Water. Both Soda_Jerk and Lawrence will be in attendance for a Q&A afterwards. Soda_Jerk will also appear at the Fremantle Arts Centre where they will be debuting The Carousel, a “dark and compelling presentation that is part lecture, part video performance…Navigating their way through an elaborate matrix of film samples, the artists will unearth a hidden history of cinema that traces the capacity for recorded media to seemingly reanimate the dead” (website). Soda_Jerk, The Carousel, Fremantle Arts Centre, July 21, www.fac.org.au; Soda_Jerk vs Tony Lawrence, Revelation Perth International Film Festival, July 22, www.revelationfilmfest.org

Ian de Gruchy, Gertrude Hotel

photo Bernie Phelan

Ian de Gruchy, Gertrude Hotel

the real fitzroyalty

There will be a similar combination of the live and the mediatised at this year’s Gertrude Street Projection Festival, on from July 22 to 31 (keep an eye out for Kate Warren’s review in our September 5 e-dition). On the evening of July 27, you can go to the Atherton Gardens Estate to hear Stories Around the Fire: The Hidden History of Aboriginal Fitzroy, which features “the memories, cultural knowledge and stories of our real Fitzroyalty: the Traditional Owners, Elders and respected Aboriginal community members of Fitzroy” (website). Later in the week, there is a walking tour of the site, where you can learn more about the locations and the artists, including Olaf Meyer (RT76, RT86, RT86), Ian de Gruchy (RT64), Kit Webster (whose projections were seen at Dance Massive), Arika Waulu, Yandell Walton (RT85), Nick Azidis, Lindsay Cox, Salote Tawale, Rowena Martinich and Greg Giannis. On the final Friday there is Sensory Overload, a night of music and projected art at the Workers Club. Gertrude Projection Festival 2011, July 22-31; www.thegertrudeassociation.com

I Wish I Knew

full of film

Still in Melbourne, and still on screens, it’s time for the Melbourne International Film Festival. The opening night features The Fairy, a Belgium-French-Canadian-Australia collaboration which “pays homage to Chaplin, Keaton and Jacques Tati [with] a few added contemporary socio-political twists” (press release). Other highlights include the world premiere of Fred Schepisi’s (RT87) The Eye of the Storm, which is based on the Patrick White novel and features Geoffrey Rush, Judy Davis and Charlotte Rampling. Other Australian films include David Bradbury’s (RT71) documentary about Paul Cox (RT48, RT50, RT51) On Borrowed Time, Michael Rymer’s Face to Face and Jon Hewitt’s X. International films worth investigating include Alexei Balabanov’s (RT92) A Stoker and Jia Zhang-ke’s I Wish I Knew (see Dan Edwards’ appraisal of his work in our Contemporary Chinese Cinema archive highlight) as well as Dreileben, a triple-bill of 90-minute movies made by German writer-directors Christian Petzold (RT79), Dominik Graf and Christoph Hochhäusler. Dreileben is part of a new program called Prime Time, which focuses on works made for television by directors best know for their cinema—an interesting and important idea in an era when Martin Scorsese is directing episodes of Boardwalk Empire for HBO. Primetime will also premiere the first two episodes of the ABC TV series The Slap, based on Christos Tsiolkas’ novel. Melbourne International Film Festival, July 21-August 7; www.miff.com.au

Side to One

photo Chris Herzfeld

Side to One

side to one

Last seen in Tanja Liedtke’s construct (RT83), Lisa Griffiths (RT49) is about to debut her own work Side to One. Choreographed in collaboration with ADT regular Craig Bary (who also danced for Liedtke, see RT61), the piece “follows two individuals destined to connect, attracted like magnets they are never static but constantly evolving” (website). Side to One will premiere in Adelaide, at the Festival Centre, before travelling north to Parramatta Riverside, where it will form part of a season of dance, alongside Martin Del Amo and Ahil Ratnamohan’s Mountains Never Meet (read Gail Priest’s interview with Del Amo in RT103). Side to One, Adelaide Festival Centre, July 27-30, www.adelaidefestivalcentre.com.au; Parramatta Riverside, Aug 10-13, www.riversideparramatta.com.au

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

John Leary, Samantha Young, Jody Kennedy, Thomas Henning, The Business

photo Heidrun Löhr

John Leary, Samantha Young, Jody Kennedy, Thomas Henning, The Business

NEOLIBERALISM’S NEO-DARWINIST RALLYING CALL, GORDON GECKO’S “GREED IS GOOD” (WALL STREET, 1987), REMAINS LARGELY UNDISCREDITED DESPITE THE LESSONS OF THE GFC, SO EMBEDDED IS THE ETHOS OF SELFISHNESS IN EVERYTHING FROM TV ADVERTISEMENTS WHERE PEOPLE PINCH FOOD, BOYFRIENDS AND CARS FROM FAMILY OR FRIENDS, TO REALITY TV’S CRUDE AND CRUEL ELEVATION OF SOLE SURVIVAL OVER COOPERATION, TO THE PERSONAL PRONOUN-ISM OF SELFHOOD INITIATED BY MYSPACE AND CONFIRMED BY MYBUS, MYSCHOOL, IPHONE AND THEIR SUNDRY IMITATORS.

The corresponding failure of public empathy over issues like asylum-seeking (save at the safe distance offered by donating to charities subsequent to natural disasters) and the reinvigoration of 19th century-style philanthropy (as the gap between wealth and poverty again radically widens) provides the depressing context for Belvoir’s production of Jonathan Gavin’s bitterly funny The Business. It’s set in the 1980s, the very period in which the ‘greed is good’ ethos was getting into its public stride—and we still march to its insistent step in 2011. The world of The Business feels quite like home.

Grossly self-obsessed behaviour is central to Gavin’s bitter-black comedy of bad manners and inheritance snatching, with director Cristabel Sved and costume designer Stephen Curtis wickedly ramping up the rude behaviour and appalling dress sense of the characters to the edge of grotesquerie, but somehow without losing the sense of these people as real, thwarted and, at times, oddly innocent and certainly pathetic—such is their tunnel-vision of the world.

Gavin and Sved took their cue for The Business from Russian writer Maxim Gorky’s grim, sometimes comic play, Vassa Zheleznova, which premiered in 1911 and was later a favourite of Stalin who saw it many times, presumably enjoying the agonies of a bourgeois family in their act of self-destruction (and enforcing changes to the play in 1935 to suit his tastes). Gavin’s play is based on Gorky’s; it is not an adaptation. But in both there is a shared, strong focus on the female characters.

In Gorky’s original, Vassa, wife to a shipping agent, Zheleznova, is relieved when her husband dies—at the end on Act 1 as opposed to the wrenching, protracted and off-stage decline in Gavin’s play which ups the suspense and complications of the mother and her disaffected daughter’s machinations to secure the inheritance the household patriarch would have denied them. Zheleznova’s death is also a relief because the charge of raping a 12-year-old servant girl will now not go to court. Vassa battles on alone, corralling daughters and servants, bribing dockworkers and police and bickering with her estranged socialist daughter (torn between motherhood and the life of a revolutionary) over possession of the latter’s child. The pressure is such that Vassa dies at the play’s end, an exhausted manipulator. Gorky’s empathy for her is limited, but he makes it clear that as well as being a nasty bourgeois she is to varying degrees a victim, though never without fight.

Kate Box in reflection and Thomas Henning, The Business

photo Heidrun Löhr

Kate Box in reflection and Thomas Henning, The Business

The Business’ 1980s family is immigrant in origin (no coffee, just a steady flow of tea), wealthy, the adult Australian-raised offspring and their spouses child-like and spoilt. The runaway daughter Anna (Kate Box) returns home, apparently more principled than the rest but, like her mother, Van (Sarah Pierse) embittered by her father’s mistreatment and ready to conspire with Van to seize the inheritance from the ne’er-do-well siblings who would promptly sell-off the family business. As with Belvoir’s Wild Duck (RT102), the social and political context inherent in the original play has no substantial contemporary equivalent in The Business, which seems a pity given the rich complexity and contradictions of 1980s Australian politics. Although this is frustrating it certainly amplifies the sheer vacuity of an emerging materialist life-style culture—save for its business (unlike Vassa’s, only vaguely indicated) this family lives in a closed circuit of vituperation, envy and a refusal to forgive.

The plays by Gorky and Gavin share the same spirited assault on the bourgeoisie—but what at first seems grimly frantic and comic slips into dispirited horror. Gorky’s Vassa demands that her husband suicide (he dies without resort to that but there is no grieving); Gavin’s Ronald (Van’s crippled second son; Thomas Henning) kills his wife’s lover Gary (Russell Kiefel) and the family dutifully manages the cover-up. Not least because the principal mother-daughter relationship is more nuanced and the two women win out, The Business comes off as more complex than Gorky’s Vassa Zheleznova (incidentally The Business appears to borrow some of its plot from the even grimmer Egor Bulychev where a wealthy father is dying, initiating a struggle for his property).

The Business might represent a victory for women but not necessarily for integrity or compassion, as if to say the legacy of the 80s is a greedy, self-serving, culture, whose children live in luxury and surly disaffection, emasculated by their parents who completely control the business. In this world Van must live on, the legacy doubtless intended for a daughter who will become like her mother, or already has.

If The Business is not strong on 80s politics and culture, the specificities of time and place are largely left to design (Victoria Lamb)—an aptly tackily furnished, expensive modernist home with Californian bungalow open stone walls, a lounge room replete with board games for children who will never grow up, and a sunny porch that becomes a site for unexpected violence. Costumes (Stephen Curtis) and hairstyling are comically acute, viciously accentuating character traits and some of the fashion follies of the period. Van’s power-dressed shoulders and daughter Anna’s great height pushed up by heels and hairstyle immediately suggest competing forces. The casual wear and pronounced body shapes of the other brattish siblings, Simon (John Leary) and Natalie (Samantha Young), amplify their laziness while the arch-backed, lank-haired, bare-chested wild-child Ronald (Henning) lurches about like a purposeless Iggy Popp. A persistent soundtrack of 80s pop ranging from the execrable to the arty further compounds the period sense. The family lives inside this bubble. The business is not loved—it’s simply what it means in terms of survival or sustained leisure.

The one aspect of the family business that is focused on is a legal suit against it for the death of a worker who refused to wear a protective mask (“What is OH&S anyway?”). Van simply doesn’t want the company to accept responsibility—the victim was, after all, a chronic smoker. This is the world of The Business—a selfish society that doesn’t care enough for itself let alone others. Simon puts it in context, his: “I started buying art works from the coons across the river. I give then 10 bucks for a dot painting then I can sell it for two hundred. Hello. People buy that shit. And the guys I buy from are not gonna sue me for negligence or cry to Four Corners because the ventilators in the workshop stop running.”

Sarah Peirse, The Business

photo Heidrun Löhr

Sarah Peirse, The Business

Inevitably, a limited range of concerns and character traits generates grotesques, utterly without empathy for the dying father (who clearly showed none to them) and locked in a bitter fight for an inheritance that Van has worked so hard for but that others simply feel they deserve. Emotions run to extremes but in Van we can see the fluctuating degrees of frustration, anger, near defeat and the need for reconciliation with Anna, even if it entails compromise. Van shows some compassion for the adulterous daughter-in-law Jennifer (Jody Kennedy)—even, as in Gorky’s original, working with her in the garden. The rest is misunderstanding, confusion, blindness and occasional insights that can’t be explored—Jennifer: “We’re all unhappy; none of us know how to love anything.” The best she can sadly come up with is: “I’m a human mix tape.” Van herself can barely live up to what she expects of her children: “These young people. ‘Duty,’ ‘consideration’—foreign concepts. I keep hoping one day they’ll grow up.” Her relationship with her husband is just as muddy: “So what? Maybe he was violent and drunk and yes he cheated on me, but it’s men like this who made this country what it is.”

What makes The Business potent is its emotional cruelty presented in the guise of comedy, sometimes bordering on farce, rich in gags (the business over a dead parrot, the nouveau riche ‘luxury’ of croissants stuffed with Fruit Loops), in explosive tensions and, not least, suspense (who will get the inheritance?)—and then shock. Director Cristabel Sved and her cast are endlessly inventive, keeping these monsters believable. If you were hoping for empathy and compassion and felt short changed then The Business was not for you—like Gorky’s original, this is tough social satire, even if Gavin is a tad more forgiving. And sometimes tougher: a communal sing-along in the Gorky is replaced with the dissolute Simon and Natalie’s faithful rendering of a ‘Tab cola’ jingle, followed by Simon’s “Want a root?” It’s that kind of play, that kind of world. In the current political climate we’re hardly in a position to deny it.

Performances in The Business were uniformly excellent, underpinned by a strong sense of ensemble. Sarah Pierse’s Van rarely allows her bitterness to defeat her purpose or her anger to overrule the requisite moments of compassion or opportunity. Pierse plays out Van’s considerable contradictions without doubt. Kate Box as the returning prodigal with a purpose is all elegance and bottled restraint almost ready to act but when she does so it is with reason as well as anger. Jody Kennedy as Jennifer is slatternly but engagingly sensitive; Grant Dodwell as the company manager is gentle and fair—if an ignored moral compass; Russell Kiefel is strong as Gary the apparently easy-going but embittered brother of Van’s dying husband; John Leary and Samantha Young are an horrendous couple, the ultimate uncaring brats, bravely played with physical and vocal verve; and Thomas Henning is the crippled Ronald who believes himself unloved—and he is, the best his mother can do to cover the murder of Gary is to have the boy committed to a psychiatric clinic. Henning’s Ronald is physically confined to his staggering gait but, when not pathetically self-aware, always on the edge of exceeding his emotional borders. In working from Gorky’s Vassa Zheleznova, Jonathan Gavin has created a play that is his own, one finely realised by his collaborators and, sadly, a play for and of our times.

–

Belvoir: The Business, writer Jonathan Gavin, based on Maxim Gorky’s Vassa Zheleznova, director Cristabel Sved, performers Kate Box, Grant Dodwell, Thomas Henning, Jody Kennedy, Russell Kiefel, John Leary, Sarah Pierse, Samantha Young, set design Victoria Lamb, costumes Stephen Curtis, lighting Verity Hampson, composer/sound Max Lyandvert; Belvoir St Theatre, Sydney, April 27-May 29; www.belvoir.com.au

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 pg. web

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net