Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

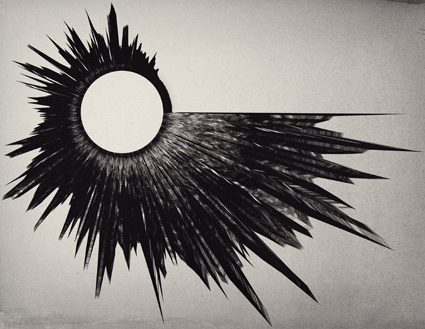

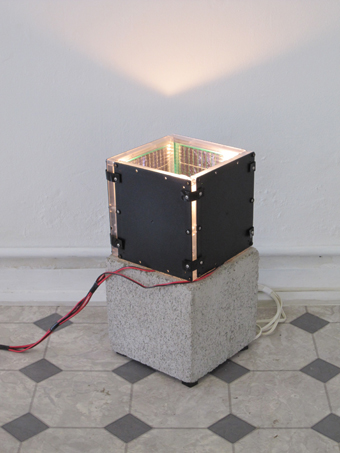

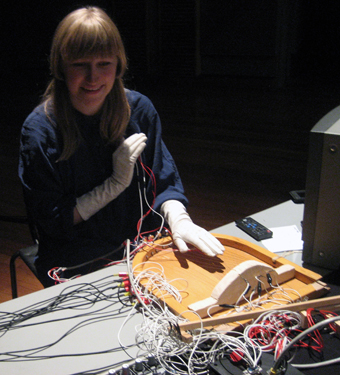

Case Study

photos Justin Harvey

Case Study

WHEN UNDERBELLY FESTIVAL DIRECTOR IMOGEN SEMMLER CASUALLY QUIPPED IN RT103, “PEOPLE LIKE GOING OUT TO COCKATOO ISLAND,” I’M NOT SURE SHE REALISED JUST HOW MUCH: AUDIENCES FOR THE FINAL FESTIVAL DAY—THE CULMINATION OF A 16-DAY DEVELOPMENT LAB—FAR EXCEEDED EXPECTATIONS, REACHING 2,200 PEOPLE.

Extra ferries had to be scheduled as the normal service became taxed, people were turned away at the entrance at times as the festival reached capacity and queues grew to Depression era proportions. Throngs of people across a broad demographic seem to be interested in the alternative arts, as long as they’re in a fascinating location.

Of course the downside was that many of the performance works were designed for a limited audience (some one or four at a time) and even the centerpiece, OJO by Strings Attached with a capacity of 500, was fully booked by the time I arrived at 4pm, so I have to admit, I failed the Underbelly challenge. However I tracked down some esteemed colleagues, Teik-Kim Pok and Sarah Miller, who had much better time management skills, to comment on some of these works. For my part, I spent my time queuing (to no avail) and taking in the installation works that inhabited the nooks and crannies of Cockatoo Island.

Case Study

photo Justin Harvey

Case Study

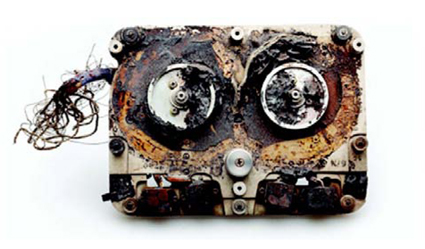

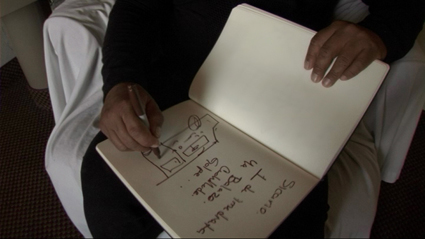

case study, [xuan] spring, pattern machine

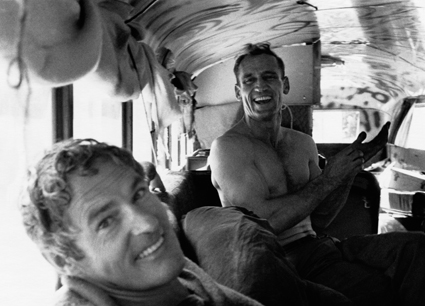

The most impressive installation, and perhaps the most intensive process in Underbelly was Case Study in which six artists—Perran Costi, Jesse Cox, Emily McDaniel, Adam Parsons, Damian Martin and Justin Harvey—moved to the island for the 16-day lab, taking with them only a suitcase. If there were any Survivor-style power plays during the development the final installation was a picture of harmonious communal living. A series of makeshift huts and lean-tos were scattered around an old workshop, each with bedding, curtains, found objects and text curios. Some hummed with quiet sound installations and most glowed hauntingly with projected stills and videos. Plant and moss specimens from around the island adorned surfaces like miniature gardens and small assemblages were to be found in nearly every crevice. Exploring issues of inhabitation, colonisation and migration, Case Study offered a wabi-sabi micro-environment of wonderful intricacy.

![[Xuan] Spring, Ngoc Nguyen](https://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/48/4854_priest_spring.gif)

[Xuan] Spring, Ngoc Nguyen

courtesy the artist

[Xuan] Spring, Ngoc Nguyen

Ngoc Nguyen also worked with ideas of domesticity in her installation, [Xuan] Spring. During the Lab she photographed the interiors of several of the abandoned houses on the island adorned with objects and elements associated with the Vietnamese Spring Festival. For the final installation the photographs were displayed in a small office/workshop, accompanied by rows of spring plants and flowers. The beautiful simplicity and intimacy of the work was reinforced by the presence of family members serving sweets and tea to visitors. Nguyen’s Spring was impressive for its subtle, yet no less integrated, use of the site

Pattern Machine was an intriguing audiovisual environment and performance by James Nichols, Dan MacKinlay, Jean Poole and Sarah Harvie. A giant inflatable wormlike object occupied one end of a vast workshop while video projections adorned the far end, glancing across a magnificent piece of old machinery. As was the case with most things in Underbelly, I didn’t catch the whole performance (I had to run to catch the ferry home), but the 20 minutes I experienced offered a rich soundscape of field recordings—flocking seagulls, machine rumbles—underpinned by sweet synthesiser tones delivered quadrophonically, with some great use of video masking to create projections that worked specifically with the architectural features.

Gail Priest

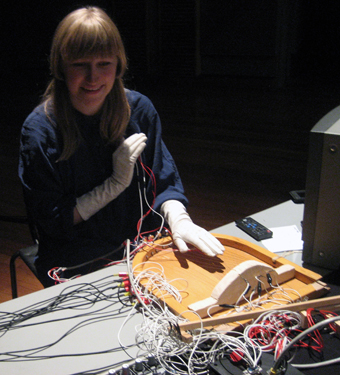

Fetish Frequency, Inflection

photos Dylan Tonkin

Fetish Frequency, Inflection

inflection, all you can stand buffet, awful literature is still literature I guess

The island’s colourful past evokes treasure hunt sensibilities and attempting to live up to this promise of adventure, some of the artists responded with works exploring audience interaction. Inflection, an “interactive theatre game,” asks us to imagine an alternate version of Cockatoo Island. Stumbling into the middle of the story, I meet a troupe of ‘facilitators’ in a low-ceilinged room in the Naval Store, black stockings masking their faces. In the centre is a mannequin torso sitting upright amongst black garbage material surrounded by photos of various sites on the island laid out in an ominous looking ring. Above this is a clue played on video loop, prompting us to carry out one of five major rituals. A few audience members hesitantly step forward to fulfill one of these tasks: “build a lover from these objects.” Unfortunately, given the nature of the event, I have to move on and fail to witness the conclusion of this action, but Fetish Frequency’s haunting mix of audience-driven storytelling and installation building/intervening is something I hope to experience in their next outing.

Next door our Underbelly experience was becoming more rumble-belly as we anticipated a feast of sorts in Butterfries’ All You Can Stand Buffet. Billed as ‘’the disfigured love child of Dante’s Inferno and Sizzler,” we are ushered in by a performer who lays out the ground rules (replete with end-of-days metaphors) for moving through the rooms—each a different buffet ‘course’—the changes signaled by the loud clanging of a steel salad bowl.

Beginning our first course we are surrounded by mounds of strewn rubbish and encouraged to sift through black garbage bags for barely edible items, among them heads of iceberg lettuce left in various states of defoliation by previous audiences. Accompanying this is a diatribe on Third World famine and an exhortation to overcome our privileged First World disgust. This prompted some in my audience, already familiar with the practice of dumpster-diving and the earnest activist tenor of the work, to respond in one-upmanship from then on, to which the Butterfries team struggled to respond. Subsequent courses included being force-fed bread rolls, served minestrone soup out of a cling-wrap lined toilet, a makeshift abattoir with a row of raw chickens impaled on a wall overlooking a blood-soaked floor and a dinner party where two performers’ strained exchange invited my restless audience group to weigh in, escalating the action into a food fight. While Butterfries’ audience-wrangling strategies need bolstering, their efforts to visually reference the aesthetic of disgust is a worthwhile achievement for their first collaborative effort.

I choose to decompress from the gastronomic challenge by visiting the Festival Bar for some mulled wine while taking in one of the more relaxed offerings, Applespiel’s Awful Literature is Still Literature I Guess. At this point, surrounded by towers of books, they regale us with a series of abject confessionals which segue into an ironic promotion of books considered obscure and questionable in literary merit completing the bar’s role as a sensory pit-stop for the traumatised, exhilarated and perplexed among us island-hopping conceptual treasure hunters.

Teik-Kim Pok

Whale Chorus, Rhapsody, Paul Blenheim, James Brown, Janie Gibson

photos Josh Morris

Whale Chorus, Rhapsody, Paul Blenheim, James Brown, Janie Gibson

rhapsody, ojo, v

Whale Chorus took the idea of the musical and broke it right across their collective hootenanny kneecaps in Rhapsody. Even at this early stage of development, this short work-in-progress was performed with panache by Matt Prest, Janie Gibson and Paul Blenheim. It was silly, smart, kitsch and funny.

Referencing everything yet nothing I could quite put my finger on, Rhapsody evoked moments of Oklahoma but also Deliverance, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers and Psycho, not to mention various high school musicals, segueing from popular culture to irreligious cult. The costuming for Paul Blenheim and Matt Prest—red checked shirts and tight black pants—was inspired while Janie Gibson’s deadpan Doris Day provided a great counterpoint to boyish petulance, blokey bravado and dang-crazy angst.

Whale Chorus “aims to borrow techniques used for creating music to create theatre” and the effect of translating musical concepts such as polyphony and dissonance into theatrical manoeuvres leads them into some hilariously unlikely places. Matt Prest’s delivery of the Beatles’ “Taxman,” and Janie Gibson’s attempts to get two reluctant lads to sing the Judy Garland standard “Good Morning” reminded me of classic comedy—think Marx Brothers or Laurel and Hardy without the pratfalls. Kazoo, celery, song, story and hypnotism were brought together in an absurd narrative to create something utterly idiosyncratic and funny.

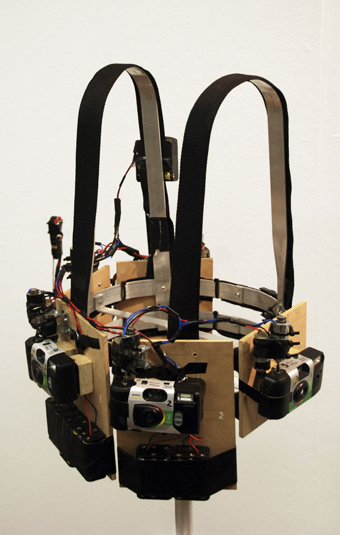

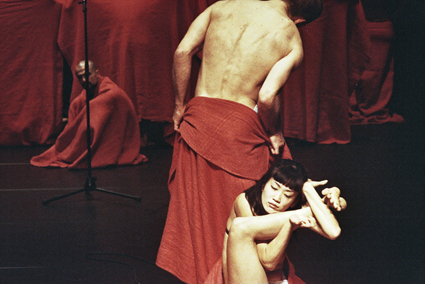

OJO, Strings Attached & Younes Bachir, Underbelly

photo Catherine McElhone

OJO, Strings Attached & Younes Bachir, Underbelly

At the other end of the emotional spectrum was OJO created by Strings Attached and Younes Bachir, previously a collaborator with La Fura dels Baus. Brought to Australia by Deborah Leiser-Moore, Artistic Director of Tashmadada (Melbourne), Bachir worked with a large group of highly skilled physical theatre performers as well as emerging practitioners.

Performed at one end of the cavernous Turbine Hall, the work begins before the audience enters the space, with a single performer hoisted high in the air, flailing and spitting words at the gods. On the other side of a large curtain, the audience stumbles across bodies sprawled or curled foetus-like on muddy, wet concrete floors amidst the wreckage and detritus of modern industrial society. The imagery is apocalyptic, the performers intense, edgy and focused. I’m reminded of Nietzche’s dark “primordial unity” that seeks to awaken our Dionysian nature through an evocation of the primal, ritual, extreme physicality and chaos as a means of bringing us to harmony.

Anyone old enough to experience the 1989 production of La Fura dels Baus’ Suz/o/Suz at the Hordern Pavilion will remember the massive spectacle and ritualistic nature of the work: blinding lights, cacophonous noise, water and mud, sex, birth, festival, sacrifice and death, combined with a fantastic physicality and extraordinary aerial work. Audience members ran for their lives as huge machines and implacable performers bore down on them.

OJO worked with similar materials and themes, albeit stripped back, and without elaborate or expensive sets, but the experience was no less intense. One of the most thrilling moments occurred when the performers manually dragged the huge machinery high in the ceiling of the Turbine Hall from one end of the performance area to the other. The horrifying yet compelling momentum of the industrial machine—Blake’s “dark satanic mills”—and its devastating impact on the natural world was powerfully evoked.

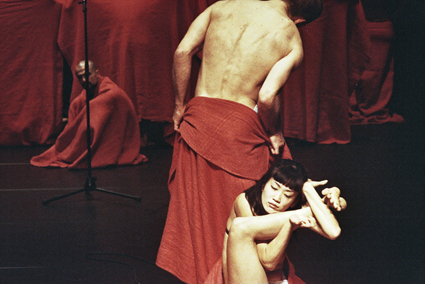

Justin Shoulder, V

video stills Sam James

Justin Shoulder, V

From darkness into light, the strangely weird and fantastical creature that is V emerges from an old, sandstone house in the convict courtyard, one of the oldest sites on the island. White gridlines shimmer and pulsate like visible electricity as this urban demon appears swaying from side to side, carrying a large book with the word V on its cover. An apparition, alien or the ancient ancestor-spirit of Cockatoo island—I have no idea—but that doesn’t stand in the way of my enjoyment of this work. An audiovisual spectacle, this is a huge collaborative effort devised and performed by Justin Shoulder, directed and produced by Jeff Stein in collaboration with composer Nick Wales, a founding member of Coda, video and lighting designer Toby Knyvett working with Sydney Bouhaniche, Cheryle Moore of Frumpus fame and that wizard of theatre spectacle, design and contraption-making, Joey Ruigrok. It was a great end to my Underbelly day.

Sarah Miller

lab work

With the culmination of activities in one big bonanza there is a danger of losing perspective on the developmental status of many of the works in Underbelly, some of which began a mere 16 days before. However audiences could visit the island in the weeks prior to watch the artists right in the midst of the thorny business of artmaking. I regret that I didn’t take up this opportunity, as I may have been able to make a one-on-one appointment with J Dark in Joan of Arc is Alive and Well and Living on Cockatoo Island by Triage Live Art Collective or have the drive-in experience of Julie Vulcan, Ashley Scott and Friends with Deficits’ Spotlight Bunny.

After a smaller-scale festival in the streets of Chippendale last year, the 2011 Underbelly, thanks to its site and more rigorous programming, reached a whole new scale and level of engagement with audiences and artists. If the event continues on Cockatoo Island, it feels as though it would be best to expand to a two-day final event in order to satisfy its eager audience. GP

Underbelly Arts 2011; Case Study, Perran Costi, artists Jesse Cox, Emily McDaniel, Adam Parsons, Damian Martin, Justin Harvey; (Xuan) Spring, artist Ngoc Nguyen; Pattern Machine, artists James Nichols, Dan MacKinlay, Jean Poole, Sarah Harvie; Fetish Frequency, Inflection, artists Jimmy Dalton, Lucy Parakhina, James Peter Brown, Skye Kunstelj, Aimee Horne and Amelia Evans; Butterfries, All You Can Stand Buffet, artists Damien Dunstan, Jennifer Medway, Kirby Medway, Tessa Musskett; Applespiel, Awful Literature is Still Literature I Guess, artists Simon Binns, Nathan Harrison, Nikki Kennedy, Emma McManus, Joseph Parro, Troy Reid, Rachel Roberts, Mark Rogers; Whale Chorus, Rhapsody, artists Matt Prest, Janie Gibson, Paul Blenheim, James Brown; Strings Attached & Younes Bachir, OJO, Younnes Bachir, artists Alejandro Rolandi, LeeAnne Litton, Dean Cross, Kathryn Puie, Angela Goh, Matt Cornell, Mark Hill, Kate Sherman, Carolyn Eccles, Gideon PG, Robbie Ho, Matt Rochford, Elisa Bryant, Charlie Shelly, Julia Landery, Victoria Waghorn, Cameron Lam, Craig Hull, Leanne Kelly; V, artists Justin Shoulder, Jeff Stein, Toby Knyvett, Sydney Bouhaniche, Nick Wales, Cheryle Moore, Joey Ruigrok; Underbelly artistic director Imogen Semmler, executive director Clare Holland; Cockatoo Island, Sydney; Lab July 3-12, Festival July 16; http://underbellyarts.com.au/

This article first appeared in RT e-dition august 23.

RealTime issue #105 Oct-Nov 2011 pg. 5

© Gail Priest & Teik-Kim Pok & Sarah Miller; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Samantha Scott, Man Made Hybrid

courtesy the artist

Samantha Scott, Man Made Hybrid

we are what we eat

In Samantha Scott’s Man Made Hybrid, potatoes have eyes, actual eyes, and, uhhh… fins. Scott’s delicate and sometimes whimsical assemblages offer wry speculations on the possible ramifications of genetically modifying biology, exploring “the natural imperative of genetic information; the instructions that control how living things grow, develop and carry out life processes and survive (press release).” Scott’s exhibition is part of Craft Victoria’s Craft Cubed Festival 2011 themed HYBRID, offering a month long series of activities including exhibitions, professional development workshops, open studios, a market and an online portal. While you might have missed Adele Varcoe’s iFOLD technique in which she shapes human skin (still attached) into temporary garments, there’s still time to appreciate Tessa Blazey and Alexi Freeman’s Interstellar Gown made from 600 metres of gold plated chain. Man Made Hybrid, Samantha Scott, Aug 23-Sept 3, Heronswood, 105 Latrobe Parade, Dromana, Melbourne; http://craftvic.org.au/craft-cubed/satellite-events/exhibitions/man-made-hybrid; Craft Cubed Festival 2011, various venues across Melbourne, Aug 4-Sept 3; http://craftvic.org.au/craft-cubed

action fashion

public fitting, Mark Titmarsh, Todd Robinson. See Vimeo for full credits

Keeping up the fashion theme is Public Fitting at MOP Projects in Sydney, a collaboration between painter and video artist Mark Titmarsh and former fashion designer now artist Todd Robinson. In a live performance on the opening night, fashion and painting will literally collide in an action painting fashion catwalk free-for-all. The results will be exhibited as garments, videos and paintings exploring the intersection of the artists’ practices. Public Fitting, Mark Titmarsh, Todd Robinson, MOP Projects, Aug 18-Sept Chippendale, Sydney; www.mop.org.au/

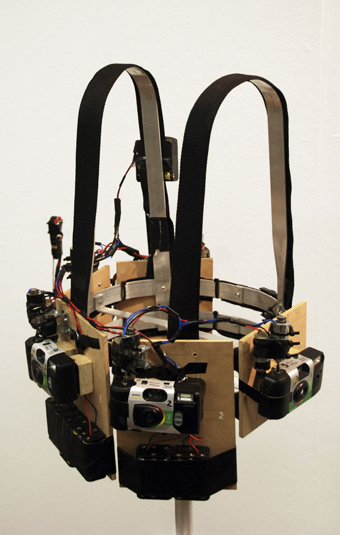

Phoography, Max Lyandvert, George Poonkhin Khut & NIDA Production Students

courtesy the artist

Phoography, Max Lyandvert, George Poonkhin Khut & NIDA Production Students

brainwaves, soundwaves

Max Lyandvert, well known for his dark and haunting soundscapes for theatre, is currently artist-in-residence at NIDA courtesy of the Seaborn, Broughton & Walford Foundation. Collaborating with second year Properties, Costume and Production students Lyandvert has dreamt up the sound installation Phonography, which will inhabit the evocative environment of the Paddington Reservoirs with a “forest of hanging, waterlogged garments fed by currents that turn the clothes into speakers (press release).” The sounds of adjoining Oxford Street will also be fed into the caverns to “make it seem as though the audience is hearing the street sounds above from underwater.” The installation will also feature the work of George Poonkhin Khut further developing his investigations into biofeedback audio installations as he captures people’s brainwaves to create a score for musicians to play. (Read about Khut’s Cardiomorphologies here and here) Phonography, August 24-25, 5-7pm, Paddington Reservoir Gardens, Paddington, Sydney

a room of one’s own

In response to the thriving independent theatre scene in Sydney, The New Theatre has instigated The Spare Room initiative presenting the work of four new-ish local companies. The season kicked off earlier in the year with Dirtyland, a new Australian play by Elise Hearst, and the Australian premiere of UK writer Philip Ridley’s Piranha Heights. The final two shows are coming up starting with Katie Pollock’s A Quiet Night in Rangoon, presented by subtlenuance, telling the story of an Australian journalist in Burma in 2007 during the Saffron Revolution. The final work is Lucky, a physical theatre piece poetically exploring the issue of human trafficking, by Dutch writer Ferenc Alexander Zavaros and presented by IPAN International Performing Arts Network. The New Theatre is currently calling for submissions for its 2012 The Spare Room program with a deadline of September 30. The Spare Room: A Quiet Night in Rangoon, subtlenuance, Aug 18-Sept 10; Lucky, IPAN International Performing Arts Network, Oct 6-22; The New Theatre, Newtown, Sydney; www.newtheatre.org.au

The Hamlet Apocalypse, The Danger Ensemble (Melbourne production)

photo Morgan Roberts

The Hamlet Apocalypse, The Danger Ensemble (Melbourne production)

the end of the world as we know it

La Boite has also been showcasing the Brisbane independent theatre scene through its Indie Series. The final installment is by The Danger Ensemble presenting The Hamlet Apocalypse (to be reviewed in RT105): a group of six actors performing Shakespeare’s Hamlet on the eve of the end of the world. The Danger Ensemble is made up of artists from diverse performance backgrounds including Butoh, physical theatre and experimental cabaret. Director Steven Mitchell Wright writes: “We have gone down the path that leaves the work the most open, where time is broken and glimpses of truth and experience can be accessed by the audience in a non-literal and anti-theatrical way (director’s notes).” While Mitchell believes the work “will polarise audiences,” the production was very well received at the Melbourne Fringe Festival in 2010. La Boite Indie, The Hamlet Apocalypse, The Danger Ensemble, Aug 26-Sept 11, La Boite Theatre, Brisbane; www.laboite.com.au; www.dangerensemble.com

Quiet Time workshop with Reckless Sleepers

courtesy the company

Quiet Time workshop with Reckless Sleepers

a bit of shush

CIA Studios in Perth is calling for participants for Quiet Time, a workshop with Mole Wetherell from the UK/Belgium group Reckless Sleepers. Quiet Time will bring together 10 artists from a range of artform areas to explore the “the city as a basis for research and stimulus(media release).” Reckless Sleepers formed in 1988 and often work with a research and residency model to create cross-disciplinary, site-specific works that are “installed rather than presented (company website).” The workshop will take place in December, with applications closing August 29. Participant stipends and interstate travel allowances are available to assist artists to attend the Lab. For more information or to be sent an application form email kate@pvicollective.com; www.ciastudios.com.au/

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Emily Morandini, filet électronique

photo Kusum Normoyle

Emily Morandini, filet électronique

ON THE LEAFY FRINGE OF CAMPERDOWN PARK, I.C.A.N.’S (INSTITUTE OF CONTEMPORARY ART NEWTOWN) NEWEST SHOW ADDS A LAYER OF ANACHRONISM TO THEIR TRADEMARK INCONGRUITY. FILET ÉLECTRONIQUE/ISLAND IS A GENTEEL COLLECTION OF POST-SUBURBAN ARTEFACTS IN THE VERY URBAN FRINGE. A CONTEMPORARY SALON APOCALYPTICISM, OR SOME FUTURE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECONSTRUCTION UNSTUCK IN TIME—WHATEVER… THIS SHOPFRONT STANDS OUT FROM THE BROWN AND IMPERTURBABLE LINE-UP OF DECENT LIFE LIKE MAD MAX IN CRINOLINE.

Emily Morandini’s piece is the filet électronique and has the virtue of a completely self-descriptive name. Round filet lace nets are threaded with copper needlework, punctuated at the ends by batteries and speakers, emitting a treble whine. Yep, networks, right angles, minute interconnected fibres—craft had ’em before mass electronics. Check, check and check. You remember the Hyperbolic Crochet Reef (created by Christine and Margaret Wertheim, http://crochetcoralreef.org) where dainty handicraft recalls raw nature? This is the yang to that yin, a stitched homage to circuitry over coral, courtly handicraft for the post-technological parlour.

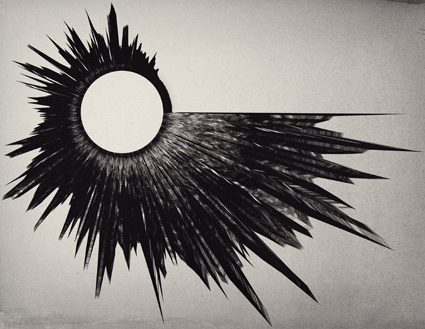

Peter Blamey, Island

photo Kusum Normoyle

Peter Blamey, Island

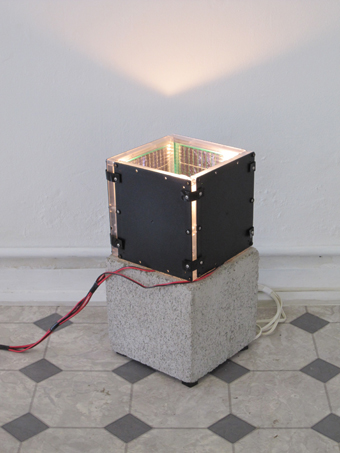

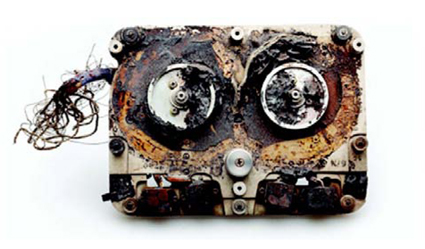

Two octaves below, Peter Blamey’s Island also hums, and occasionally squeals. This originates in a different future, long after the Anthropocene. It’s not needlepoint, or anything else from CRAFT magazine. Blamey liberates himself from the conventions of traditional handicraft by participating in the plastic, evolving genre of repurposing illegally dumped crap off the street.

A bouquet of found circuit boards opens leaf-wise, with machine-drilled pores and copper-etched capillaries. This is one part robotic Ikebana to two spontaneously generated silicon organisms. The surface is dusted with a faint fuzz of copper floss, moving in the air currents, and it squeals as you brush it, like an electric touch-me-not.

Peter Blamey, Island

photo Kusum Normoyle

Peter Blamey, Island

The piece itself is embedded in the flows of that neo-ecology—mineral waste digesting in the urban metabolism—its body scrap accretions of once-were appliances. This assemblage of motherboards and speakers is powered parodically and circuitously: electricity is derived from a solar panel lampshade which wraps around an incandescent light bulb, a ‘detrivore’ feeding off oil in a travesty of photosynthesis. Conductive cilia wave in the ambient radio fields, recycling electromagnetic waste into mindless warbling.

Where the connectivity in Morandini’s piece is punning, verbal and personal, Blamey’s work is direct, physical and inhuman, the waste fields of a million appliances made audible. The sound from those speakers is the unfiltered interference from the ad hoc antennae of the circuit-boards, performed it seems, for ears other than ours: the secret life of circuits, played out on an Earth after us.

Here are two sardonic takes on the DIY resurgence. Post-consumerist transposed into post-consumer in a world where DIY has been associated as often with fertiliser bombs as with handicraft; where survivalism and tree changing vie for fertile land; where going back to the land may lead you to an open-cut pit, or a strip mall, but you decide to stay there and till it yet.

Emily Morandini & Peter Blamey – filet électronique/island, ICAN, Sydney; July 22-Aug 7; http://interlaps-overlaces.tumblr.com/; http://icanart.wordpress.com/2011/07/19/july-2011-electronique-filet-island/

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. web

© Dan MacKinlay; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

{$slideshow} MARTHA GRAHAM WROTE, VERY BEAUTIFULLY, “TO UNDERSTAND DANCE FOR WHAT IT IS, IT IS NECESSARY WE KNOW FROM WHENCE IT COMES AND WHERE IT GOES” (MARTHA GRAHAM, PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 1966).

Some theorists, such as André Lepecki, make a big deal out of the melancholy of the dance critic, imbuing the experience of writing about movement with a sense of loss (however unintentionally) that I have always found melodramatic. But the question of remembrance is related to culture, to fashion, to fame, to legacy and as such is more interesting to the critic and to the choreographer than to the dancer. To dance is to revel in the now.

Dance improvisation has to be understood as something very different from finished choreography. Choreography is to movement what a play is to stage presence: a set of directions, located outside particular time and space; universal and thus generic. Says William Forsythe: “The purpose of improvisation is to defeat choreography.” All the arguments made in Performance Studies, in favour of presence over representation, apply.

To witness an improvisational dance performance requires the observer to look beyond the movement itself. It cannot be judged as choreography, because it is deeply unrefined, unedited movement: at best serendipitous, often cacophonous. To watch improvisation is to watch a performer shed layers of performance until, if lucky, we are left with a body moving as if for the first time; a raw and vulnerable, unpredictable life; pure presence. As Paul Romano, one of the Little Con organisers, says, “Improvisation is living amplified.” In that sense, improvisation is more thoroughly dance than any other kind.

At The Little Con special, the audience sits in a cross-shaped line of chairs, dividing the performance space into four rectangles, each with a different 'curator.' The one closest to the entrance is animated from the start: Fiona Bryant and Lucy Farmer are engaged in frenzied movement anchored in a recognisable social reality, like over-caffeinated secretaries. At five-minute intervals, other rectangles join in. After an hour, they similarly fade out.

Different quadrants expand on different areas: Bryant and Farmer present a poppy, humorous and very accessible exploration of states under pressure. Tony Yap and his two dancers, on the other hand, explore both ritual movement and voice, using the tools of the Malay shamanistic trance dance tradition: singing on the very border of inarticulation accompanies movement. Peter Fraser, whose background is in Bodyweather, and his three dancers, work strongly as a cohesive team of bodies, splattering across the walls, chairs and floor of their quadrant, but always extraordinarily attuned to each other's presence. In this wealth of movement around me, literally around me, I am only vaguely aware of what is happening in the last rectangle, occupied by Alice Cummins, practitioner of Body-Mind-Centering®, and collaborators.

As they increase, some collisions are very satisfying: Cummins' presence electrifies the interrelations of Fraser's quartet. Some are more disruptive of the precarious balances created. There appear at least glimpses of every pitfall of improvised performance: competition for attention, imitation as a means of achieving a semblance of unity, a certain aloofness as a vehicle for comedy. But interaction is sometimes hilariously consonant: as Tony Yap delivers a long, focused shamanistic gargle of sorts, Fiona Bryant, in a red dress, with scissors and shoulder pads, climbs on a chair and starts screaming in response.

The key to it all is the extraordinarily heightened presence of the performers, and the accordingly sharpened concentration of the audience. Since the movement cannot be predicted, there is no arc to any gesture. Except for the final 15 minutes, the absolute absence of structure creates an experience without horizon. Much of the joy comes from watching audience members respond with great focus to interaction the ending of which they cannot anticipate: two boys slowly leaning to one side of their chairs as Farmer appears to be attempting to walk over them. In another moment, Cummins shifts across the floor, but ends up thoroughly immersed in picking through my frilly skirt.

Only once it is over do we notice that the space has assumed the temperature and humidity of a Turkish bath. It has been an exhausting, exhilarating hour. There is simply no melancholy to this experience, no sense of loss. As Martha Graham elaborates, the dance comes from the depths of man's inner nature, and inhabits the dancer; when it leaves, it lodges itself in our memory. In The Little Con, this trajectory is revealed on stage from slow start to exhausted end. The mystery of the choreography, a finished thing which appears out of nowhere and is gone, is something quite different from movement that rises like a roar from the core of the dancer, levitates suspended and then slowly closes onto itself. These have been some of the most intensely focused minutes I have had as a performance audience, not unlike trance, or meditation. Who would have thought that our concentration span could be so long?

The Little Con is a monthly dance improvisation organized by a dedicated collective since 2005. It is hosted by Cecil Street Studio, the home of Melbourne's improvisation community, but has also appeared at Deakin University and elsewhere. Sometimes it is free form, but throughout the year there are special, curated events, such as this one from curator Paul Romano.

The Little Con, curator Paul Romano, performers Emma Bathgate, Brendan O’Connor, Tony Yap, Lucy Farmer, Fiona Bryant, Peter Fraser, Kathleen Doyle, Alexandra Harrison, Jonathan Sinatra, Gretel Taylor, Alice Cummins; Dancehouse, Melbourne, Aug 6, www.thelittlecon.net.au.

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. web

© Jana Perkovic; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Untitled, 2010, sound generated digital still, Riley Post, ANU graduate

DARREN TOFTS ONCE DESCRIBED THE PREHISTORY OF TECHNOLOGICAL TRANSFORMATIONS OF CULTURE AS “EVERYWHERE FELT BUT NOWHERE SEEN IN THE TELEMATIC LANDSCAPE OF THE LATE 20TH CENTURY.” AS WE MOVE INTO THE SECOND DECADE OF THE 21ST CENTURY, THE AFFECTS THAT TECHNOLOGICAL TRANSFORMATIONS PRIVILEGED IN CULTURE AND ART IN THE LATE TWENTIETH CENTURY—INTERACTIVITY, INTERACTION, IMMERSION—APPEAR NOW TO US AS COMMONPLACE AND THEIR USE IN ART AND MEDIA TAKEN FOR GRANTED. IT IS EASY THEN TO FORGET JUST HOW VIBRANT THE MEDIA ARTS SCENE HAS BEEN IN AUSTRALIA SINCE THE 1980s. MEDIA ARTISTS’ ENGAGEMENT WITH THE TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATIONS OF THAT TIME CAN, LIKE A KIND OF FORGOTTEN PREHISTORY, ALSO BE SAID NOW TO BE EVERYWHERE FELT BUT NOWHERE SEEN (WELL, RARELY).

The restructuring of the Australia Council boards in 2005, which included the replacement of the New Media Arts board with the Inter-Arts Office and the transfer of funding for a significant portion of media arts practice to the Visual Arts Board (VAB) and the Music Board, was meant to reflect the subsumption (or is it sublimation?) of media arts practices to the mainstream. According to the Media Arts Scoping Study produced in 2006, these changes did not reflect a failure by media arts to consolidate itself as a set of stand-alone practices. Rather, it was testament to the success of these artists that what was once a discrete field was now something that arts practitioners from all fields were incorporating into their practices.

Similarly, media arts as an academic discipline seems to be settling back into more established disciplines—Fine Art, Media and Communications, Design, Creative Arts and Science and Technology—no longer a monstrous hybrid struggling to find its place in the gallery or the museum. Again, whether this is indicative of subsumption or sublimation is hard to tell. Certainly, in a post-Bradley Review tertiary education environment, university managements prefer disciplines that are recognisable and established (not to mention attractive to the mainstream).

One sure outcome (for this writer at least) is that it makes the whole question of the Australianness of the media arts curriculum quite difficult to answer. Of the 10 academics that I spoke to, only two, Kathy Cleland (The University of Sydney) and Darren Tofts (Swinburne University), placed a pointed emphasis on Australian media art in their curriculum. Interestingly, both of the subjects that they teach approach media arts from a predominantly theoretical perspective and use Australian media artists as case studies. Tofts’ interest in the historical trajectory of media arts in Australia is evident in his response to the question of the importance of using Australian examples:

“In focusing on Australian artists there is an immediate context for students to ground media art practices; but more importantly it is valuable for students to be aware of the crucial contribution Australian artists have made and continue to make to the international media arts scene. For instance, cyberfeminism as an international formation, movement, arts practice and concept is impossible to think of outside the contributions made by VNS Matrix, as well as the subsequent, individual arts practices of its founding members (Francesca da Rimini, Josephine Starrs); or for that matter the crucial, pro-active curatorial/critical work and advocacy of Julianne Pierce and Virginia Barratt.”

Brogan Bunt and Lucas Ihlein (University of Wollongong) pointed out that their main engagement with local context is through regular guest lectures. “We have recently had artists like Wade Marynowsky, Deborah Kelly, Louise Curham, Lucas Abela, Mike Leggett and Lynette Wallworth give lectures to our students. We try to incorporate at least two guest lectures by local practitioners in each Media Arts studio subject each session. We also have strong commitment to contributing to local Media Arts culture. Apart from dialogue with local Wollongong artist run spaces (Project Contemporary Art Space, 5 Crown Lane, and so on), we have also been building links to relevant festivals/events/groups in the Sydney metropolitan area.”

Other practitioner academics such as Ross Harley (COFA, UNSW), Martine Corompt (RMIT), Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr (SymbioticA) and Troy Innocent (Monash University) all commented that while they would use Australian examples where appropriate and available, the necessary resources were not always available to make that possible. As Zurr noted: “…our programme focuses on art and science and furthermore, predominantly on art and the life sciences. Therefore, our teaching is focused on artists (Australian or non-Australian) who engage in working with life, living materials and biotechnology (rather than generally media art or art and technology). There is a growing number of artists within Australia who are working within this field but publication wise—the majority of books (scholarly or not) magazines, journals etc are produced overseas without emphasis on the ‘Australian’ aspects.”

The question of access to resources certainly recurred in many of the responses. The accessibility of the artworks themselves and the scarcity of critical responses to the art, as well as the lack of documentation and poor archiving of media artworks have presented challenges to academics working in the field.

Kathy Cleland noted that as a result of her experience as a curator over the last 10 years, she has a lot of documentation of Australian media art works which she uses in her course. She also pointed out, however, that there are not that many books specifically focusing on Australian new media art (Darren Tofts’ Interzone: Media Arts in Australia is one of the exceptions) and that “books published internationally don’t tend to mention many Australian artists with the exception of Stelarc who is in everything!”

Darren Tofts pointed to John Conomos’ Mutant Media which examines the convergence of media arts, film and video art as a key text. “Stephen Jones’ recent Synthetics is also an important contribution to the field, evidencing the robust longevity of Australia’s contribution to the international scene.” Both Cleland and Tofts pointed to RealTime as “invaluable” with Tofts’ noting that “the Australian media arts scene is unthinkable beyond the support and stewardship of Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter.” All of the respondents agreed that more online magazine/journal resources focused on media arts would be welcome.

Norie Neumark, in her role as Director of the new Centre for Creative Arts at La Trobe University argued that “it would be useful to have more and varied material and critical analysis of Australian media arts, including online resources, DVDs and CDs. However it is also vital to see Australian media artists included in broader publications, both about contemporary Australian art and about international media and contemporary art. In my own recent publication, my co-editors and I were particularly keen to include Australian media artists in a routine way in an international publication.” (Norie Neumark, Ross Gibson, and Theo van Leeuwen eds,Voice: vocal aesthetics in digital arts and media. MIT Press 2010; reviewed in RT103)

As Martine Corompt noted, the difficulty of accessing artworks continues to plague media arts: “I used to have a great collection of early interactive works, on CD and floppy disk, but of course they are all unplayable now due to changes in operating systems. Even some of my own old work also can’t be played.” The platform-specific nature of many media artworks is compounded by the difficulties they present to collections managers and archivists. This is not, of course, specific to Australian media artworks. However, more needs to be done to preserve what is left if the impact of Australian artists is to continue to influence the local curriculum. Paul Thomas (COFA and Curtin University) has been instrumental in drawing attention to this pressing issue through his involvement in the Media Arts Scoping Study (MASS) and the National Organisation of Media Arts Database (NOMAD). Similarly, the ARC funded research project, Reconsidering Australian Media Art History in an International Context, led by Ross Harley, Anna Munster, Sean Cubitt, Michele Barker, Paul Thomas, Darren Tofts and Oliver Grau aims to create a foundational online resource which will “provide future artists and curators with a cohesive overview of Australian media arts’ recent milestones and developments, crucial to making significantly innovative new work.” (See http://bit.ly/pu9f6z)

As a discrete discipline, the sound arts continue to have only a tenuous hold in academia. Their public profile, in contrast, is maintained by a robust (and youthful) underground of practitioners (see Julian Knowles, “Sound art and the extended university,” RT80). As Knowles points out, “it is clear that, despite its fragility, the contemporary sound and experimental music performance scene is significantly intertwined with the small network of university departments who embrace this area of practice and that the best students have developed into exceptional practitioners through this informal collaborative network.” It is in this context that he argues for the importance of the practitioner/teacher in universities: “Staff who work at these institutions, though now small in numbers, are often highly active as practitioners in the field with substantial profiles. They are also active as organisers of events and festivals that provide both a modest infrastructure for established and emerging practitioners and an opportunity for students to immerse themselves in the exceptionally rich and diverse sound culture in Australia.”

This probably explains why all of those whom I tried to interview for this article were unavailable. But the point is well made and supported by Norie Neumark: “The role of the Australian artist who is also an educator is crucial. In the current climate, where creative practice as research has been recognised through ERA [the Excellence in Research for Australia initiative], artist educators are particularly well placed to contribute both to the research environment and to provide direct inspiration and models to students. And working with students, from undergraduate to postgraduate, is energising and stimulating for the artist educators themselves. I see artist educators as vital in bringing theory and practice together in a vibrant way, both in their own teaching and in collaboration with others.”

Australian media arts may not be as discretely visible inside and outside the academy as they seemed to be during the 1990s but there is room for cautious optimism about its future. The new centre at La Trobe is particularly promising and the work being done to preserve a history of Australian media arts is invaluable. But vigilance is required to ensure that the sublimation of media arts practices to the mainstream does not result in their subjugation.

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. 36

© Lisa Gye; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

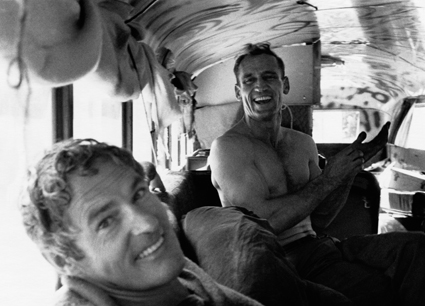

RUMOUR HAS IT THAT AVANT-GARDE CINEMA CONTINUES TO THRIVE AROUND THE WORLD, BUT LOCALLY ONE MIGHT SUPPOSE THAT THE MEDIUM WAS AS DEAD AS VAUDEVILLE. SO THE AUSTRALIAN INTERNATIONAL EXPERIMENTAL FILM FESTIVAL HAS THE APPEAL OF A CONSPIRACY AGAINST THE PRESENT—CONDUCTED, FOR THE SECOND YEAR IN A ROW, AT THE BACK DOOR WAREHOUSE IN DEEPEST PRESTON, OUT ON THE FABLED 86 TRAM LINE FAR BEYOND THE BOHO HANGOUTS OF HIGH STREET, NEAR THE DECAYING INDUSTRIAL PRECINCT WHERE PHILIP BROPHY SHOT HIS DYSTOPIAN NORTHERN VOID (2007; RT 78, P27).

Best to be honest: here in Australia—at least, for those of us who aren’t regularly able to scoot off to specialist events overseas—it is hard to get more than the faintest first-hand impression of the state of play in the experimental film arena. That’s one reason AIEFF deserves celebration, even if this year’s eclectic program felt more assembled than curated and even if 90% of the “films” were screened, in accordance with their makers’ wishes, on video.

While for the individual viewer this matters or doesn’t, from a strict artisanal perspective the two media remain as distinct as pottery and robotics: one lesson to be taken from the AIEFF program is that film, at this budgetary level, is still easily the superior format for artists concerned with what are imprecisely termed the “material” qualities of light and colour. This could be observed even in works as fragile and ephemeral as Irene Proebsting’s Super-8 Harmonic Ghosts—where faintly Gothic images brush against each other like dry, blown leaves—or as unabashedly decorative and “girly” as Jodie Mack’s 16mm Posthaste Perennial Pattern. It was good to see Tony Woods, the most persistent Super-8 filmmaker in Melbourne, return with Colour, Glass and Chrome, which, as ever, seeks out redemptive beauty in fragments of the mundane: in this case, the play of light on shards of glass found in a rubbish skip.

Film transmutes, it’s still tempting to suppose, whereas video only records. In fact, festival entries in both media showed alternate impulses to demystify and remystify the image, a dialectic also evident in the two prevailing approaches to sound design: on the one hand, the crunches and rustles of ‘raw’ or deliberately distorted sound, the aural equivalent to queasy, handheld camerawork; on the other, gloopy electronica akin to passing through a New Age carwash, intended to put you in a receptive trance.

Overlapping with this was the old battle between the representational and the abstract—between the moving image as a document and the screen as an open field where unforeseen forms can emerge. On the ‘abstract’ side were fireworks displays such as Simon Payne’s Vice Versa Et Cetera and Paul O’Donoghue’s Phasing Waves—both on video, the latter oddly culturally specific in its nostalgic deployment of clunky 1980s technology. At the other end of the spectrum, Erica Scourti’s Woman Nature Alone is a performance piece not a million miles removed from the hijinks of a ‘twee’ comedian like Josie Long, with Scourti herself enacting a half-hearted charade of communing with the environment: romping across parkland, hugging trees and eventually dropping off to sleep.

The aim might be to satirise outworn romantic postures, including a need to occupy the spotlight—but Scourti, like Long, does not escape the perils of studied cuteness. By contrast, Charles Fairbanks pointedly erases himself from Wrestling With My Father, a conceptual one-shot that really works. Fairbanks Snr is filmed head-on as he (apparently) watches his son fight it out in the ring; a burly fellow in a cap, he sits with his legs wide apart, drums his fingers during lulls, and shifts back and forth on the bench to follow every detail of the unseen action. Fairbanks’ equally successful The Men is a close-up essay on a related subject, with a mini-camera attached to a wrestler as he grapples with a bearded opponent; the fragmentary images are redolent of eroticism as much as combat.

Implicitly, such ventures put quotation marks around the notion of the personal, an unavoidable problem for artists without the alibi of commercial cynicism: how far are captured images to be understood as mirrors of consciousness, as opposed to raw material manipulated from a more-or-less ironic distance? AIEFF had its share of ‘diary’ works reliant on the idea of the camera operator as a semi-domesticated flaneur—gazing out an apartment window at dawn or wandering idly round the city, offering spiritual sympathy to beggars, watching trains go by. Taking a couple of steps back, an alternate option is to dedicate yourself to re-processing old home movies, with the passage of time as part of the point, as Mike Leggett does in his beautiful Bosun’s Chair. Or you can simply borrow from the communal archive: the ultimate example of this tactic, Bob Cotton’s ZeitEYE flashes across the history of modern graphics from Futurism to the Wii, with fleeting captions suggesting a media arts version of “We Didn’t Start the Fire.”

Speaking to many of these issues, Steven Ball’s Personal Electronics is a study in paranoia composed of deranged clips lifted from video-sharing sites: the sources are mainly American, though the wry bemusement implied by these juxtapositions is British to the core. A figure slumped on a couch twitches violently, like an extra from Paranormal Activity (2008); a woman lectures us in voiceover on the esoteric import of a purple shaft of light which seems to emanate from a parked car. Acknowledging that some will perceive this “directed energy weapons ray” as visual noise, she instantly rejects the possibility: “These are very clearly lasers…Lens flares are not so concentrated, for one thing, they’re more diffuse.” In context, it’s a parody of hermeneutics: the artist striving to impose significance on ‘found’ material, the viewer labouring to decode that intention from the other side. Madness awaits us all, as we struggle to make meaning from what we see.

2011 Australian International Experimental Film Festival, The BAck doOR, Melbourne, April 29-May 1

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. 35

© Jake Wilson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Starrs & Cmielewski, Incompatible Elements at Moving Image Centre, MIC Toi Rerehiko, Auckland

AS GOVERNMENTS RELUCTANTLY ADMIT TO THE EXISTENCE OF A CLIMATE CRISIS BUT DO LITTLE ABOUT IT, MANY MEDIA ARTISTS ARE RESPONDING TO THE EVIDENCE OF THE ECOLOGICAL DISASTER THAT IS CLEARLY ALREADY HAPPENING. JOSEPHINE STARRS AND LEON CMIELEWSKI’S PROJECT INCOMPATIBLE ELEMENTS (2010-2011) PRESENTS THE INTENSE VISUALITY OF REGIONS OF THE ASIA-PACIFIC THAT HAVE BEEN HIT BY EXTREME WEATHER. WHILE HUMAN ACTIVITY IS ABSENT IN THE DIGITAL SATELLITE-SCAPES, THE HUMAN MIGRATION FORCED BY WEATHER EVENTS IS IMPLIED IN THE POETRY, LYRICS AND ORATORY THAT INSCRIBE THE VIDEO WORKS.

The work’s fusion of text and topographical landscape presents a challenge to the separated or incompatible categories of ‘nature,’ ‘environment’ and ‘culture.’ Incompatible Elements was first exhibited at Performance Space in Sydney in 2010 followed by MIC Toi Rerehiko in Auckland in March 2011.

An ‘incompatible element’ is a term in geochemisty used to describe mineral properties in rare earth and in the oil industry. ‘The elements’ also refers to weather forces producing effects that are becoming more and more incompatible with human life. Starrs and Cmielewski tell stories on behalf of future “climate refugees” as part of their ongoing concern with migration stories. They used data maps in earlier work such as the interactive screen-based work Seeker (2008) to reveal the politics of forced migration due to conflict over resources such as diamonds, titanium and oil. Incompatible Elements also recognises the largely unquantified human migration resulting from climate change—of people often seen as incompatible with national immigration policies. As philosopher Bruno Latour urges, the artists recognise that ecological issues include the social, political and cultural as opposed to perpetuating the Modernist ‘human/nature’ divide.

The four video landscapes presented at MIC are composited satellite images of the flooded planes of the Ganges, the former dust bowl of Australia’s Murray-Darling basin, the dry banks of the Coorong in South Australia and the erosion of Mount Taranaki in New Zealand. Accompanying light boxes provide the micrographic complement to the remote satellite pictures as detailed photographs of the dry earth. The artists present the polar extremes of drought and deluge: the predicted and increasingly manifesting extremes of weather-induced disaster in regions of Australasia. By encouraging us to examine their finely stitched topographical images closely in the defamiliarised context, even the normally detached gaze of the Google-Earth browser is politicised.

In Incompatible Elements, the leisurely paced pan of the fly-over satellite map is incrementally modified by lines of text that grow out of features of the landscape itself. After a while, streams or fields become words that slowly creep into the frame, inviting comparison to the relentless anthropogenic expansion across the Earth. The sources of the animated words include the environmentalist poetry of Australian Judith Wright, her line “And the River was Dust” curls out of the Murray-Darling basin’s tributary streams while the lyric “days like these” from the John Lennon song “Nobody told me” emerges from the watery arteries of the Ganges. A phrase in the Ngarringjerri language, “A Living Body,” creeps out of the dusty banks of the Coorong and “Puwai Rangi-Papa,” the words of a Maori elder encircle Mount Taranaki.

Starrs and Cmielewski direct attention to Maori and Aboriginal people and the fate of migrants through their use of their language. The perspective of the satellite drifting through space is often described as an omniscient view of a detached observer, but this perspective is also a familiar way of charting territory in traditional aboriginal cultures. Theorist Lisa Parks notes that Aboriginal people have incorporated “satellite dreaming” into their symbolic narratives of cultural identity in artwork and in independent television programming. Both indigenous citizens and migrants occupy a border zone where they are particularly vulnerable to extreme weather events. Maori are traditionally ‘people of the land’, often living in coastal regions, while migrants living in temporary structures are prone to weather-borne disaster.

For the MIC version of Incompatible Elements Starrs and Cmielewski added a video element to the suite of works called Puwai Rangi-Papa. This phrase was translated for the artists as “waters of the radiant sun and earth mother” by Taranaki kaumatua (elder) Dr Te Huirangi e Waikerepuru. Te Huirangi introduced this term to the artists on their SCANZ digital art residency that began at the Owae marae (meeting house) on the West coast of New Zealand in January 2011. Taranaki locals themselves suggested to the artists that they make a work around the erosion of the dramatic peak of Mount Taranaki. The ‘Fuji’ shaped mountain dominates the geography and weather system of New Zealand’s North Island. Rock fall and erosion have increased since violent storms have intensified on the west coast to the extent that local inhabitants are now threatened with the loss of their homes. Analysing aerial photographs of water and soil shifts on Taranaki and its waterways, scientists estimate that more than 14 million cubic metres of the mountain have collapsed since the late 1990s. Huge rock falls and debris have caused blockages in waterways, along with floods that send more boulders down the river, widening the banks. The soundtrack of Puwai Rangi-Papa includes the tumbling of stones that keeps residents who live on the edge of Taranaki awake at night. In Maori terms the ‘mauri’ (life-force) of the mountain is being eroded by the changing climate along with its iconic physical form.

The video images for Puwai Rangi-Papa are created from four Land Information New Zealand satellite images that are seamlessly brought together. The viewing position tracks around the uncannily perfect circle of the satellite map of the mountain and after several minutes the words “Puwai Rangi-Papa” emerge from the fields around Taranaki’s perimeter. According to the artists, this is nature and culture “collapsing into each other.” Using the ubiquitous format of Google Earth and GPS applications on iPhones and cars that has changed our relationship to maps in only a few years, Starrs and Cmielewski are trying to slow down the way we view this satellite imagery to give pause for reflection on the implications of a landscape transfigured by weather.

Many pakeha (white) artists in Aotearoa-New Zealand avoid the use of Maori concepts as the conceptual underpinnings of their work because of the sensitivity around the appropriateness for citizens who are not tangata whenua (people of the land). However when permission is granted by an elder of the region for a story to be told and te reo (Maori language) to be used, the artists are provided with a place from which to transmit important messages across cultures. If settler cultures can shift from conceiving landscape or weatherscape as inert matter ‘to-be-looked-at’ to living bodies encompassed in Maori terms such as ‘mauri’ then we come closer to ecological reconciliation. Puwai Rangi-Papa could signal an important shift in articulating a reconfigured political ecology where Western environmentalism and indigenous cosmologies might join in restoration and care of the land.

An artwork like Incompatible Elements is not propaganda or politics, yet the artists are unwilling to leave socio-political questions to designated experts. The cumulative effect of Incompatible Elements is not alarmist, rather human responsibility is implicated in the large-scale geo-physical changes to our world that the artists represent. The work encourages reflection on the impact of cumulative weather events that are difficult to conceptualise as statistical data or scientific warnings.

Incompatible Elements, MIC I Toi Rerehiko, Auckland, New Zealand, March 4-25

Australian media arts watchers will be interested to know that “MIC Toi Rerehiko promotes a dynamic and growing culture of interdisciplinary media-arts practice in Auckland and New Zealand, supporting an environment of innovation, in which fusion of art and technology is developed and nurtured. Based in the heart of Auckland, MIC Toi Rerehiko has a new art gallery on Karangahape Road, and a live performance/screening venue at Galatos. We exhibit a continuous program of international and New Zealand artists working across contemporary film, video, digital media, installation, music and live performance.” www.mic.org.nz. Eds.

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. 39

© Janine Randerson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

DigitEYEzer, Laval Virtual 2011

photo Jean-Charles

DigitEYEzer, Laval Virtual 2011

THE LAVAL VIRTUAL INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE AND EXHIBITION ON VIRTUAL REALITY AND CONVERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN FRANCE, IS ONE OF EUROPE’S LARGEST GATHERINGS OF VIRTUAL REALITY AND NEW TECHNOLOGY ENTHUSIASTS. THIS YEAR, OF THE 85 EXHIBITS PRESENTED AROUND 30% WERE FROM PLACES OTHER THAN FRANCE, INCLUDING AFRICA, JAPAN AND NORTH AND SOUTH AMERICA. THIS GLOBAL SPREAD DELIVERED AN ECLECTIC MIX OF INTERNATIONAL AND TRANSNATIONAL EXHIBITS.

I had never been to such an extensive industry convention before, especially one with a dedicated stream on virtual art. Not knowing what to expect, I armed myself with a detailed presentation, designed for those who could not speak English (lots of big images) and one that contextualised the Australian media art scene in more detail than I would present at home.

It was with great surprise then I discovered that all conference delegates had to present and were mostly conversant in English (also my second language) and that Australia’s contribution to media arts internationally was well known and understood by many present at the event.

Setting the context for the conference was renowned media arts theorist Erkki Huhtamo, Professor of Media History and Theory at UCLA. In his keynote titled “Hand Screens, Wrist Watches and iPads: an Archaeology of Wearable Media,” Huthamo asked the numerous artists, technologists and engineers at the conference to reflect for a moment on the history of mobile and immersive media.

This reflection illuminated a fascinating history of wearable and portable media devices, with objects such as pocket watches, cameras and hand-held personal fans seen as precursors to modern day hand-helds. In particular, fans were not only used for cooling, but also as symbols of social status and as print mediums for portable artwork and maps.

With evolving genres such as Device Art (think Bitman by Ryota Kuwakubo and Maywa Denki, 1998), this convergence of technology, art and design can be seen as an extension of those historical origins of portable media. By understanding the origins and symbolic meanings of these devices, Huhtamo suggested, contemporary artists and technologists are in a much better position to tap into their cultural legacy, and therefore be more successful in deploying them artistically and commercially.

Commercialisation was certainly the main driver for most exhibitors at Laval. The three projects I look at in this article—IFace 3D, Haption Exoskeleton and Invoked Computing—were all commercial with no particular focus on media arts, but like many of the exhibitors at Laval, were keen to harness the creative energy of users, including artists, for their inventions.

iface 3D— digitizer (france)

DigitEYEzer exhibited their recently released smartphone application iFace 3D, the first 3D face scanner available for mobile phones. With iFace 3D, users create 3D, lifelike models of themselves or their friends or anything close at hand, by shooting moving images on their phones and sending them to a 3D reconstruction server online. After a few minutes the user is then sent back the 3D model, ready for printing or publishing on the net. These 3D representations can be downloaded into virtual games or sculpted into physical 3D models with 3D printers. Staff at the booth displayed an arresting 3D generated, colour sculpture of their Sales and Marketing Manager, Didier Sy-Cholet, something that’s possible for all users to do once they have their own scanned data (and access to a 3D printer).

The interest in photo-realistic self-representation in virtual games and social media is certainly there, so it will be interesting to see how artistic engagement with this application evolves. I wonder for instance, how Australian augmented reality projects such as Warren Armstrong’s (Un)seen Sculptures (2011) or Thea Bauman’s Digital Culture Fund project Metaverse Makeovers (2011) might engage audiences with these new tools in times to come.

Haption, Exoskeleton Demonstration Booth, Laval Virtual 2011

photo Jean-Charles

Haption, Exoskeleton Demonstration Booth, Laval Virtual 2011

haption exoskeleton (france)

Haption’s force-feedback exoskeleton was one of the more intriguing exhibits to play with at Laval. Established in 2001, the company develops high performance haptic [touch-based] instruments and programs involving force-feedback in virtual reality, for both industrial and academic purposes.

Stepping into the exoskeleton at the booth, I felt a bit like Ellen Ripley from Aliens (without the sweat and the attitude), but instead of killing an acid-spitting critter, I had to put a virtual peg in a virtual hole.

The feedback system in the exoskeleton was fantastic, as it provided force-feedback on all six degrees of freedom (translations and rotations), which is essential for a realistic interaction with 3D objects. I was so mesmerised by the actual physical feedback that I never got the peg near the hole.

In terms of haptic feedback systems and Australian arts practice, I could imagine artists such as Keith Armstrong (Intimate Transactions, 2008), Jonathan Duckworth (Embracelet, 2007), Margie Medlin (Personal Space, 2007) or Stelarc (Exoskeleton, 1998) having great fun exploring the force-feedback systems linked to virtual space.

A recent haptic focused ARC Linkage grant supported by the Australia Council, bringing together artist Paul Brown, Dr Ben Horan from Deakin University’s School of Engineering and Saeid Nahavandi, Director of Deakin’s Centre for Intelligent Systems Research, could also be situated in this context. The three-year grant aims to help visually challenged people ‘see’ artworks through haptic vibrations; force-feedback systems such as these could add a dynamic new dimension to future projects.

nvoked Computing, Laval Virtual 2011

photo Jean-Charles

nvoked Computing, Laval Virtual 2011

invoked computing (japan)

One of the most innovative and, to my mind, potentially game-changing projects to emerge at Laval this year was Invoked Computing. Developed by Alexis Zerroug (France/Japan), Alvaro Cassinelli (Uruguay/France/Japan) and Masatoshi Ishikawa (Japan) through the Ishikawa Komuro Laboratory at the University of Tokyo, the project explores a “ubiquitous intelligence” capable of recognising specific human actions and projecting sound and images onto objects linked to these actions.

The example shown at Laval involved taking a banana and bringing it closer to the ear, with the gesture triggering directional microphones and parametric speakers hidden in the room. These devices then made the banana function like a phone. Not only would the banana ring, but you could talk using the banana as a handset. The developers also used a pizza box with projected images that could follow the box around in space.

The potential for these tools in performance and installation based work is mindboggling. Imagine having any object in a space able to project sound or images and interact with those around it. What could PVI Collective (Transumer, 2010) do with this technology if they deployed it in public spaces? Or Back To Back Theatre (Small Metal Objects, 2005) with accidental audiences at train stations?

Not surprisingly Invoked Computing received the Grand Prix du Jury for Laval 2011.

australian developments

In Australia there is huge scope for artists working in virtual reality and converging technologies to continue their internationally recognised practice. Recently, with funding through the Digital Culture Fund, some fantastic live, digital projects were realised with work such as the Roller Derby extravaganza Bloodbath by Bump Projects (2010; RT100) and Adriaan Stellingwerff’s Windy and Winding (2010), a virtual balloon travel application for smartphones.

In September this year at ISEA in Istanbul, the Australian Centre for Virtual Arts is curating a major program of Australian virtual artists, titled Terra Virtualis. In addition, an Australian exhibition on robotics curated by Kathy Cleland and an exhibition titled The World is everything that is the case, curated by Sean Cubitt, Vince Dziekan and Paul Thomas will also be flying the flag.

But the most significant development for experimental art in Australian in 2011 is the recently announced Creative Australia fund, a $10 million initiative from the Federal Government.

This funding is targeted to support individual artists through the creation and presentation of significant new work and fellowships and will be rolled out by the Australia Council over the next five years.

All the Council’s artform boards will be delivering on this initiative, with the knowledge that digital culture and the potential of the national broadband network will no doubt be key considerations of many applications. We are all looking forward to seeing the outcomes of such a significant investment in contemporary Australian arts practice.

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. 41

© Ricardo Peach; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Suzon Fuks

photo Liz Scrimgeour

Suzon Fuks

SUZON FUKS IS A BRISBANE-BASED MEDIA ARTIST, CHOREOGRAPHER AND DIRECTOR WHO EXPLORES THE INTEGRATION AND INTERACTION OF DANCE AND MOVING IMAGE THROUGH PERFORMANCE, SCREEN, INSTALLATION AND ONLINE WORK. SHE IS CURRENTLY AN AUSTRALIA COUNCIL FOR THE ARTS FELLOWSHIP RECIPIENT. FUKS DESCRIBES HER NEW WORK, WATERWHEEL, AS “AN ONLINE SPACE WHERE YOU CAN INTERACT, SHARE, PERFORM AND DEBATE ABOUT WATER AS A TOPIC AND METAPHOR, WITH PEOPLE AROUND THE WORLD OR RIGHT NEXT DOOR! IT IS COST-FREE, ACCESSIBLE WITH JUST A CLICK, AND OPEN TO EVERYONE OF ALL AGES. IT FOSTERS CREATIVITY, COLLABORATION AND INTER-CULTURAL-GENERATIONAL EXCHANGE.” I ASKED FUKS ABOUT HER MOTIVATION AND AMBITIONS FOR THE WORK.

What is it about water that drove you to create Waterwheel?

I come from a country in Europe where it rains a lot and I wasn’t aware of water scarcity at all. Living in India for three years changed my perception about access to water. I had to wake up on time to fill my vessels from a tap in the street that ran only twice a day for half an hour. I had to boil it and keep it in a specific place in the house. So I built my life and time around this access to water.

When I moved to Brisbane it was a beautiful ‘garden city.’ During the drought of 2005 I worked most of the year overseas and coming back, I could see from the plane window everything was brown. Sad! It looked like a dying body. At that time I went for a walk at Wivenhoe Dam. A very striking image remains in my mind. A dried out fish caught in a small bush on the edge of the reservoir. The water level had gone down so much that the fish had been caught there, died and dried out.

I became more interested in the politics of water. I started questioning how in developed countries we have access to things and information and take so much for granted. Water is becoming a commodity. I observed that most water infrastructures are made by men, but in developing countries the collection and handling of water is usually a matter for women.

In 2008 I helped organise a networked performance with five cities around the world. We were talking about the drought in Brisbane and a group of artists in Curitiba were saying that in Brazil governments are fighting over the Guarani, one of the world’s biggest and most abundant aquifers, to own part of it for the future. It was interesting for me to see that, through the internet, people can share different perspectives on water.I’d like to share this growing awareness, and find ways to deal with water issues.

In what ways do you see water as a tangible element of your art?

Artistically, I’m interested in the contrasts and extremes of water: transparency, opacity, stillness, turbulence, the violence of water and its patterns. To me, the patterns in water hold secrets. Things are entangled there: the fluidity, stripes and rhythms make links between graphic, choreographic, musical and cinematic forms. If we could decode the patterns, we could find a writing somehow and an understanding between these disciplines.

I’m constantly collecting water samples in video and audio. With Igneous I have done two shows with actual water: Liquid Skin and Mirage (both in 2006). And before that, in 2004, Thanatonauts and Body In Question, used water in their video-scenography. I know that artists have been using water for a long time and the interest is increasing. It seems to me like a requiem for water. Before it dies.

In my memory, public water had a different presence in cities than it does now. Fountains were places of social gathering and where to get fresh water when walking from place to place. Now they are being covered. All that is left are signs saying: there once was a spring. So I thought it would be interesting to have a repository, not only of artistic works but about water in general, in order to keep a trace of our stories, cosmogonies and lifestyles, because water, cultures and cities are changing.

Did Queensland’s recent flooding influence the work?

The flood felt like a state of war. There was nothing that could be done to stop it, and it was violent. Water is not always transparent, reflecting the blue sky, but can be really dirty, smelly and sticky. The mainstream media were really making people scared, repeatedly showing the most dramatic images and playing the most dramatic commentary. Meanwhile, on social media people were infiltrating like water, in a constructive way, giving helpful tips. The water issue made discussions deeper.

Waterwheel interface

Are you a ‘water person’?

Definitely. I’m not an excellent swimmer, but I go swimming every day if I can. It’s my way of keeping fit. I find baths and water spaces relaxing and rejuvenating. When visiting a new country, I’m interested to know about water rituals and customs, and which places they have for them. It’s a way for me to better understand the place and meet people.

What can we expect when we enter the Waterwheel site?

The main thing on the Waterwheel homepage is a wheel made up of concentric rings that represents the latest 40 uploads. Anyone can log-in and upload, access and comment on that media, and message other users. From there they can go to the “Fountains” map and the “Tap.”

Users, individually or with a “Crew,” can use the Tap for a performance or presentation with webcams, media from Waterwheel, drawing tools and text chat, all on one web page. What’s very new is that any media item placed on the Tap can be moved, resized, flipped and layered over other media. Audience can engage with each other and the Crew by simply clicking on a link without having to install anything. Years of research in networked performance allowed me to see the pros and cons of, and determine the best tools, from those I found in various online platforms I used.

There are many levels on which to engage with the site and the project. Whether you’re initiating a project individually or collaborating with others or contributing to an existing one or simply spectating. A curator could get in contact with an artist, or scientists and activists in contact with their colleagues. It’s a new mode for expression, exhibition or festival.

Who are you working with on Waterwheel?

In the first year of my Australia Council fellowship I presented the Waterwheel concept in various circumstances, conferences and in sharing sessions with peers and colleagues onsite and online. I got lots of feedback, which helped to evolve the concept and I received grants from Arts Queensland and Brisbane City Council to extend the project and the team.

Waterwheel is a really collaborative project. My main partner in building up the site is Inkahoots, a Brisbane-based studio of graphic designers, programmers and a copywriter. Artists around the world are helping with the testing of the Tap. In terms of getting feedback in order to advance the project, I asked a forum of peers to come at certain times to give oral as well as written responses.

My co-artistic director of Igneous, James Cunningham, is an external eye for the experimentation on the Tap and its integration into an on-site installation performance that will happen during residencies in October and December at the Judith Wright Centre. For that event there is an entire team: dramaturg (Doug Leonard), performer (Sofia Woods), set designer (Rozina Suliman), interactive system designer (Nathen Street), production manager/lighting designer (Felicity Organ-Moore), IT technician (Will Davis), PR person and someone taking on a new role linking ‘crew’ members online and onsite.

I’ve been networking for a long time and via the internet with fellow performers in Canada, USA, Brazil, Europe, Lebanon, Indonesia, India, New Zealand and South America. For the launch of Waterwheel on August 22, I hope that this network will present a short program of performances and presentations.

You have written that water will also be metaphorical in the work: In what way?

I tried to make the whole Waterwheel project using water vocabulary because of the theme and the parallel between this vocabulary and the Internet. The words waterwheel, fountain, tap, crew, dock also give an idea to people, to the audience, of how to use the site. Users can also take a metaphorical interpretation of water for the content of the media they upload—like a dance inspired by water’s qualities or a video of sand rippling down dunes like liquid.

Above all what do you hope to achieve with Waterwheel?

I hope to raise awareness about water issues and works, that people will generate new avenues, new works and new ways of presenting and performing, finding their own style within the venue and the tools that Waterwheel offers. I’d like the project to foster sharing and creativity, cross-cultural conversation, intergenerational exchange and debate and help people who have controversial projects, ideas, or are in conflict, to make issues more public and facilitate decision-making and practical action.

How do you feel about living so intensively with a work about water?

Every day I see the relation and relevance with the work and what is happening in the world. Like the transformative aspect of water I am trying to be open and flexible and adjusting to what is happening. It’s intense because it has lots of different aspects, it’s beautiful and sometimes it’s really terrible. The tsunami in Japan and the aftermath of the Fukushima nuclear meltdown has affected my way of apprehending the world. Knowing that we are not reaching the tipping-point but are totally in it is terrifying, but at the same time, interesting to see how we can react to that in a human and positive way.

Waterwheel: http://water-wheel.net/, launching August 22. Deadline for proposals for launch August 12

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. 42

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Percussion students, Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University

SENIOR LECTURER AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE LINDA KOUVARAS REMEMBERS “A RATHER LEAN COUPLE OF DECADES” WHERE BOOKS ON CONTEMPORARY MUSIC IN AUSTRALIA WERE THIN ON THE GROUND. A RESURGENCE OF INTEREST HAS RECENTLY GRACED LIBRARY SHELVES WITH BOOKS BY DAVID BENNETT (SOUNDING POSTMODERNISM, AUSTRALIAN MUSIC CENTRE, 2008), GORDON KERRY (NEW CLASSICAL MUSIC, UNSW, 2009), GAIL PRIEST (EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC, UNSW PRESS, 2009) AND SALLY MACARTHUR (TOWARDS A TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY FEMINIST POLITICS OF MUSIC, ASHGATE, 2010), WITH WORKS BY OTHER AUTHORS PROJECTED FOR THE NEAR FUTURE.

Though many of those interviewed for this RealTime arts education edition identified a now healthier music book publishing industry, the same was not said of critical writing in journals, magazines and newspapers. The perceived critical vacuum in Australian musical life is seen to negatively impact on the teaching of Australian music in tertiary courses, the vibrancy of Australian musical cultures and students’ preparedness for their careers.

a critical deficit

Executive Director of Performing Arts at Monash University Peter Tregear explains how critical writing feeds into teaching: “As a teacher you don’t just want to show that music exists, you want to show how it exists in context. You want to show students a score, a recording and responses to the music.”

It is not just in the classroom that this scarcity of music writing is felt, but in the lives of practising musicians and sound artists. “Art-making thrives on verbal reflection and magazines/journals provide an essential forum for this,” Kouvaras asserts. Griffith University Lecturer Vanessa Tomlinson believes the value of critical reflection extends from local scenes to the wider musical world, warning of global negligence in the state of Australian music writing.