Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Avantwhatever 002-005

avantwhatever 002-005

www.avantwhatever.com

Avantwhatever is the organisation established by Ben Byrne to promote and publish his own works and those of his peers through concerts and also limited edition CDs. Matt Chaumont’s Linea started the collection in 2010 (reviewed here) with offerings by Arek Gulbenkoglu and Dale Gorfinkel, Alex White, Ivan Lysiak and Byrne himself coming out in reasonably rapid succession. While each of these artists has a distinctive approach, there is a shared sense of austerity—a serious, focussed and unadorned investigation into the essence of their materials—giving Avantwhatever a ‘house style,’ also reflected in the almost identical covers made from basic brown recycled paper.

002 gulbenkoglu gorfinkel, vibraphone/snare

Vibraphone/Snare, a single track running for just over 21-minutes, is an improvisational pursuit of vibration. Gorfinkel on prepared vibraphone and Gulbenkoglu on snare, are united in their love of small motors that they apply to their instruments (Gorfinkel also utilising the inbuilt motor of the vibraphone) and it is often impossible to tell who is generating which sound. The hum of insect-like motors underpins nearly everything, however the detail is in the changing pitches of the drives and the range of rattles, flaps and rumbles elicited from various applications. The materials dictate the structure, as new tones and hums, semi-regular rhythms and unforseen eruptions guide the players into the next moment. The recording (Rosalind Hall) is also unfussy, with a central focus, and not so much sense of the room in which it is performed. Small details play out on the edges of the stereo field, but never distract from the core of sounds in the middle. There’s no adornment here, only actions and sonic consequences blurring to create a kind of ascetic music.

003 ben byrne, disposition

Byrne’s contribution on laptop, mixer and electronics is the shortest of the selection running at 18-minutes. There is a clear sense of structure, both within the pieces themselves and the composition as a whole, divided across five distinct sections. “Part I” introduces Byrne’s sounds, dense with digital bleeps, spurts, glitches and fricatives always kept on the edge of chaos. “Part II” introduces a brief and elusive calm in the form of high, pinging, tinnitus-like tones. This is rudely swept away by “Part III”—the longest track and offered as a centrepiece of abrupt eructations, all angles and sudden shifts, with big fat squelchy sounds coarsely ground. “Part IV” maintains tension, and while never approaching figuration, seems darker and more urgent, with insistent longer tones and a clearer feeling of phrasing. Finally “Part V” seems to combine approaches from all the previous sections, somehow offering a simultaneous sense of fragmentation and sustain. While it’s a short set, the focus on structure makes Disposition satisfyingly intense.

004 alex white, genuine instability

The loudest and nastiest sounding of the collection, White’s CD Genuine Instability, made using Reaktor software, offers the most emotionally engaging listening experience perhaps because it’s the first of the series to use figurative track names. The title track, “Genuine Instability,” offers just that with signals pushed until they disintegrate; wide, dirty tones stretching and breaking across the stereo field; coarse granules disappearing into split second silences. “Customer Service Experience” is full of insistent, insect buzzes and heavy electromagnetic sounding hum. Phrasing is strong as sections shift in and out of focus, agilely scanning through the frequency spectrum and petering out to high impotent pings. “Event Loop” also delivers on its promise with a densely textured phrase that loops for over 15-minutes, but which invites an almost psychotic attention to detail as you start to hear minuscule shifts in the static. Best at volume, White’s work becomes visceral, curiously embodied despite its utterly digital origins.

005 ivan lysiak, southwest line

For this release, Ivan Lysiak works purely with feedback generated from guitar, amps and pedals. Each of the three tracks, named after train stations on Sydney’s south- west rail line, runs to just over 10-minutes with each exploring a different feedback pursuit. “Leumeah” works with a mid-range pure tone that develops octave harmonics devolving in to lower hums. Silence is allowed as signals falter and break, only to be built up again. Most surprising is a kind of trumpet-like repeated note that finally devolves into a flat nasal whine. “Ingleburn” works with a higher tone, over- and under-tones hovering on edges that eventually invade and morph into low flutters. The final track “Macarthur” surprises again with faster transitions between notes and a growing, crackly electrical interference that Lysiak shreds into ever-smaller units. South West Line is sparse, yet never static, with a constant sense of sound waves in motion, evolution and entropy.

Avantwhatever recordings are quintessentially and unapologetically difficult listening. Having heard all these artists play live, there is definitely something more satisfying in experiencing their works live and in the moment, no matter how much or how little gestural performativity is needed to make them. A large sound system and the collective listening experience better allows for the level of concentration required to really appreciate the impact of these sounds. However it’s important that these practices are documented, and Avantwhatever is creating a vital collection of some of the most interesting and challenging music currently being made.

Gail Priest

RealTime issue #105 Oct-Nov 2011 pg. web

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Melancholia, Lars von Trier

cinema exotica from home and abroad

For its 20th manifestation, the Brisbane International Film Festival is offering a range of exciting cinema experiences including Australian and world premieres. In terms of big draw cards there’s David Cronenberg’s A Dangerous Method, exploring the relationship between Freud, Jung and patient and pupil Sabina Spielrein. Provocateur Lars von Trier’s Melancholia starring Kirsten Dunst, which supposedly left the audience gasping in Cannes, will also be screening. Direct from Venice and Toronto Film Festivals comes an adaptation of John Le Carre’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy by Swedish director Tomas Alfredson (Let The Right One In, 2008) with Gary Oldman as George Smiley and described by one reviewer as “at its best as a study in minimalist aesthetics and cool, sombre, low-tech interiors.” The festival will conclude with Pedro Almodóvar’s much acclaimed, The Skin I Live In, about an obsessive plastic surgeon (Antonio Bandera) who imprisons the object of his experiments (Elena Anaya).

There’s also a strong horror and sci-fi flavour to this year’s festival. Starting on November 12 and finishing in the wee hours of the 13th is the Horror Marathon including Guilty of Romance (see RT’s review from SUFF) and Mannborg by Canadian Z-grade director Steven John Kostanski, about a half-man, half-cyborg who fights Nazi vampires. From Argentina comes Nicolás Goldbart’s Phase 7 described as “slacker comedy meets bio-apocalypse” (website). Also from Argentina is Penumbra, directed by “horror cinema’s answer to the Coen Brothers” Adrián and Ramiro García Bogliano.

Codependent Lesbian Space Alien Seeks Same, Madeleine Olnek

The Drive-In program includes the impossible to resist Codependent Lesbian Space Alien Seeks Same directed by Madeleine Olnek as well as Trailerpalooza, a whirlwind tour of sci-fi and horror trailers from the last 50-years presented by Mark Hartley playing in a double-bill with 50 Best Kills (which needs no descriptor). Australian films include the premiere of Crawl, a feature debut by Paul and Benjamin China which channels “the tension of Hitchcock and the measured violence of the Coen Borthers’ No Country for Old Men” (website); and Kriv Stender’s Red Dog, where you are encouraged in fact to BYOD—finally the canine verdict on this runaway success!

Outback Fight Club, Paul Scott

Also featured are a range of Queensland films and documentaries including two by Hungarian-born, Brisbane-based Peter Hegedus, My America and The Trouble with St Mary’s; Janine Hosking’s portrait of Chad Morgan (The Sheik of Scrubby Creek), I’m Not Dead Yet; Paul Scott’s Outback Fight Club, documenting the final days of the only touring boxing tent left in the world; Daniel Marsden’s journey into the art of the Torres Strait Islands, So The Clouds Have Stories; and Tony Krawitz’ The Tall Man, a reconstruction of the events surrounding the death of Cameron Doomadgee on Palm Island (see RT review of Adelaide Film Festival). Brisbane International Film Festival, various venues, Brisbane, Nov 3-13; www.biff.com.au/

arts fertiliser

Emerging artists and arts workers in South Australia looking for tips on how to sustain a life in the arts should check out How Does Your Arts Career Grow?, a free panel discussion organised by the Adelaide Festival Centre and Carclew Youth Arts. The forum will bring together leaders in arts and culture in South Australia with young and emerging artist to share thoughts and advice on how to develop and manage a career and how young people can shape the future of the arts. Key industry professionals involved are Christie Anthoney (Creative Director, Adelaide College of the Arts) who will facilitate the panel, Annette Tripodi (Operations and Program Manager, WOMADelaide), Brigid Noone (independent artist/curator), Edwin Kemp Attrill (Artistic Director, University of Adelaide Theatre Guild) and Ianto Ware (Project Manager, Renew Adelaide). Space Theatre, Adelaide Festival Centre; Oct 31, free; www.adelaidefestivalcentre.com.au/greenroom/how-does-your-arts-career-grow-2/

In Brisbane, Backbone Youth Arts is hosting the Future Voices Forum with a focus on “local needs and international trends” (website). Taking place in two parts the first will concentrate on Australia and the ‘Asian Century’ with panelists including Andrew Ross (Artistic Director, Brisbane Powerhouse), Cathy Hunt (Co-Founding Director, Positive Solutions) and Thom Browning (Artistic Development Coordinator, Imaginary Theatre). The second session will be an Open Spaces Dialogue led by Jim Lawson (Executive Director, Young People and the Arts Australia) taking off from provocations raised at the National Youth Theatre Summit at St Martin’s in September [http://www.stmartinsyouth.com.au/national-youth-theatre-summit/]. The Future Voices Forum is part of the 2high festival, a one-day invasion of the Brisbane Powerhouse by young and emerging performance makers and visual artists. 2high Festival, presented by Backbone Youth Arts, Oct 29, Brisbane Powerhouse; www.backbone.org.au/2high-festival/; Future Voices Forum, Visy Theatre, Oct 29, 10am www.backbone.org.au/artist/2953/

evolving fictions

Adam Cruickshank, The Half Asleep Pilgrim, work space

courtesy the artist

Adam Cruickshank, The Half Asleep Pilgrim, work space

Over three weeks, multi-disciplinary artist Adam Cruickshank will reside in West Space writing and designing The Half Asleep Pilgrim. A collage of written and visual material will be drawn from conversations with visitors and from the vast range of books that will also adorn the Back Space, borrowed from libraries and collections of the artists’ friends. At the end of three weeks the book will be finished, determined by the activity of that day rather than a pre-determined narrative. Cruickshank’s residency is one of 14 projects presented by West Space across 2011-2012 under the title Today Your Love which seeks to find ways artists might inhabit their new venue (twice the size of the old gallery) with a focus on process and experimentation over outcomes. Projects yet to come include Then & Now—the office of fixed deferrals (Back in 5) by the ever-intriguing Patrick Pound featuring an archive of photos, before and after shots, postcards of floral clocks showing each hour and other photographic ephemera which form an “index not only of time’s relentless melt, but of chance connections in the shuffle of things” (artist statement). Starting in development in 2011 for presentation in March 2012 will be a networked performance, Stay Home Sakoku: The Hikikomori Project, by Eugenia Lim, Dan West, Yumi Umiumare and David Wolf. Adam Cruickshank, The Half Asleep Pilgrim, West Space, part of Today Your Love; Oct 17-Nov 5; http://westspace.org.au

creative non-fictions

Tashmadada, the organisation which recently brought ex-La Fura Dels Baus performer Younes Bashir (see Underbelly Arts review) to Australia, is run by director-producer Deborah Leiser-Moore. She’s teaming up with US quarterly publication Creative Non-Fiction to create an Australian issue. They’re calling for essays across all forms with the only stipulations being that the stories be true and the articles unpublished. Two prizes are on offer, with the best essay (regardless of country of origin) winning AUS$6500 and an extra prize for the Best Essay by an Australian Writer winning AUS$2500. The edition will be launched as part of the 2012 Melbourne Writers’ Festival. Deadline Jan 31, 2012; each essay requires a $20 reading fee. See Tashmadada for more info: http://www.tashmadada.com; www.creativenonfiction.org

at the end of the journey

Homelands

photos James Brown

Homelands

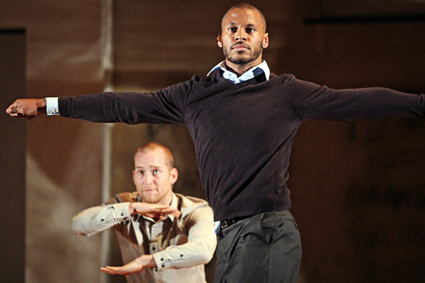

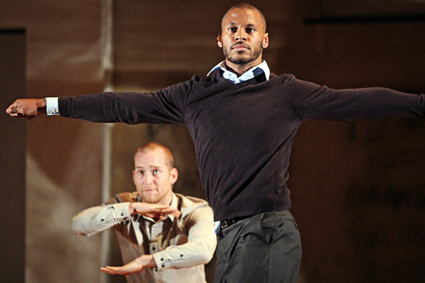

Belgian director Hans Van den Broek (Compagnie SOIT) has returned for the third and final instalment of his collaboration with some of Sydney’s most interesting dancers and performance makers. In Settlement (2007) the group left civilisation to inhabit Track 8 in Performance Space/Carriageworks exploring ideas around utopia, communality and individuality creating a truly invigorating piece of dance-based performance. Nomads (2009), also in Track 8 focused on Diasporas, the group wandering away from one home in search of another. The final instalment, developed during an off-site Performance Space residency will be delivered as a video screening at FraserStudios and depicts the characters “held, floating like driftwood in time. They have found a fictional escape into life, hiding in a fantasy of fragmented theatre” (press release). Featuring Kathy Cogill, Nikki Heywood, Manu Louw, Clara Louw, Tony Osborne, Kirk Page, Anuschka von Oppen, Nalina Wait and Van den Broek with video by James Brown and Sam James. Homeland, video showing, October 27, 5pm, FraserStudios, 10-14 Kensington Street, Chippendale

Also nearing its end is the run of FraserStudios. Since 2008 Sam Chester and James Wynter and their team from Queen Street have done an amazing job managing these artists studios and rehearsal spaces in Chippendale, temporarily made available by the Fraser Property development group. The venture has had an immeasurable impact on the vibrancy of contemporary culture in Sydney (read about the studios in RT91). Running for longer than originally anticipated, it is now time to close the doors, but there will be one last open day on October 30 where you can see the artists at work, along with talks, demonstrations of digital fabrication technology by Assemblage Studio next door, and a barbeque. While it’s the end of an era, the impact of the initiative is tangible, not only as the Queen Street team have now taken on Heffron Hall in Surry Hills, but also as the range of commercial and government spaces now open to cultural activity is on the increase (see below). FraserStudios Open Day, October 30, 1-5pm, 10-14 Kensington Street, Chippendale; www.queenstreetstudio.com/fraserstudios.html

Breaking News: From 9 January-30 June 2012, Queen Street Studio and Frasers Property will offer NSW-based Visual Artists a “bonus round” of six-month open studio residencies. For more details go to www.queenstreetstudio.com/vis-arts-residency.html. Deadline Nov 18, 2011. Details of Performing Arts residencies will be announced shortly.

pop-up oxford street

Rocks Pop-Up Projects, Perran Costi’s Personal Space: a living artwork, interactive exhibition, artists’ studio, bric-a-brac shop, teahouse and native garden

photos courtesy the artist

Rocks Pop-Up Projects, Perran Costi’s Personal Space: a living artwork, interactive exhibition, artists’ studio, bric-a-brac shop, teahouse and native garden

The range of ‘Renew’ ventures started by Marcus Westbury, kicking off in Newcastle and virally spreading to include Townsville, Adelaide and Geelong, has now been amalgamated under the Renew Australia moniker overseen by the Australian Centre for Social Innovation. In Sydney there’s Pop-Up-Parramatta and in the last six months The Rocks Pop-Up project has seen four heritage buildings turned over to artists studios and creative spaces for six months. (See image, Costi’s collaborative work Case Study was reviewed at Underbelly Arts.)

Now the City of Sydney is calling for tenders from artists, creatives and collectives interested in the short-term inhabitation of two retail shops and 14 office suites on Oxford Street—a unique opportunity to infiltrate the heart of the city! Deadline Nov 9, 11am, advertisements EOI 0811 and EOI 0911 can be viewed at http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/Business/TendersEOIQuotes/CurrentListing.asp

RealTime issue #105 Oct-Nov 2011 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Hoa X, Guy, Simon, Lucky, IPAN

photo Robbie Pacheco

Hoa X, Guy, Simon, Lucky, IPAN

OVER THE PAST DECADE, NUMEROUS PERFORMANCES HAVE BEEN MADE BY, WITH AND ABOUT REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS (SEE OUR ARCHIVE HIGHLIGHT). A CURRENT ESTIMATE PUTS THE AUSTRALIAN TOTAL AT APPROXIMATELY 40 PRODUCTIONS AND RISING. MOST RECENTLY, I SAW THE INTERNATIONAL PERFORMING ARTS NETWORK’S LUCKY, PART OF THE NEW THEATRE’S THE SPARE ROOM INITIATIVE FOR INDEPENDENT ARTISTS AND COMPANIES.

The character of the title, Lucky, never actually appears: he apparently set sail some time ago and has not been heard from since. Instead, the play, by Dutch author Ferenc Alexander Zavaros, focuses on his two brothers Dannybird (Hoa X) and Abduma (Guy Simon) whom we meet just as they too decide to flee. These opening scenes, ably directed by Sama Ky Balson, alternate between action and commentary, so that one actor says “I have to leave” and the other adds: “I tell my mother.” This device soon disappears, however, as the brothers board the raft with a third man, Mister John (Drew Wilson), who is their guide and people smuggler. Together the three men cross an unnamed sea towards an unnamed country, with little more than a container of water, a radio and some rope. We never find out if they arrive.

Hoa X, Lucky, IPAN

photo Robbie Pacheco

Hoa X, Lucky, IPAN

During this journey, the brothers reminisce about their mother whom they have left behind, and their brother who has left them. In language that sounds like a libretto they wonder where Lucky is, what he is doing and why he hasn’t written. Eventually it becomes clear that the other “birdboy,” as Mister John calls him, has probably perished at sea raising the possibility that one of the brothers may in fact be a ghost. Indeed sometimes their speech is strangely haunting while at other times it is repetitive; occasionally both—“my little brother forgets all that he has forgotten.” The people smuggler speaks in an elliptical, nonsensical English. Initially the device works to suggest the language gap, in a manner similar to a masterful scene in Brian Friel’s 1980 play Translations, but eventually it starts to grate.

Hoa X, Guy Simon, Lucky, IPAN

photo Robbie Pacheco

Hoa X, Guy Simon, Lucky, IPAN

In fact the best parts of the production happen when speech falls away completely and movement (co-directed by Kirk Page) comes to the fore. Two of the performers (Simon and Wilson) do some beautiful rope work, hanging from the ceiling and bouncing off the vertical wooden frames that surround the white raft resembling a ship’s rig (designed by Sama Ky Balson). In one scene, there is a strikingly choreographed struggle and in another the performers seem to be spinning in the sea. Unfortunately this scene is hampered by low ceilings preventing them from attaining any real height or speed. Nor does the music help: while it is ambitious and the melodies pleasant, the vocals are too loud and the lyrics too literal: “I’m following the water/ Internally displaced people/ Generalised violence.” Similarly literal are shadows made by a fourth performer and singer (Conrad Le Bron): the characters see a bird and his hands flap behind the cream-coloured sails that hang upstage. In such moments the performance becomes less than the sum of its parts, with the music, text and movement working against, rather than with, each other.

While Lucky includes some poignant moments, it is also slow and often sentimental. A lack of specificity, rather than implying universality, reads as a vague and generalised attempt to tell “the” story of “the” refugee when no such thing exists—refugees, as a group, are as diverse and contradictory as any other. I try to encounter each performance on its own terms, but I can’t help comparing Lucky to Khoa Do’s Mother Fish—a magical, universal and yet deeply personal representation also of a boat journey. Both the theatrical and cinematic versions of Mother Fish were masterful. Alongside them and others in the genre, Lucky seems an apprentice work with a way to go before it can refresh the form.

International Performing Arts Network, Lucky, writer Ferenc Alexander Zavaros, director, set designer Sama Ky Balson, collaborative moment director Kirk Page, lighting Ross Graham, costumes Azure Chapman, musical director Karina Bes, sound designer, composer Joseph Nezeti, performers Guy Simon, Hoa X, Drew Wilson, Conrad Le Bron, New Theatre, Newtown, Oct 6-22; http://newtheatre.org.au

RealTime issue #105 Oct-Nov 2011 pg. web

© Caroline Wake; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

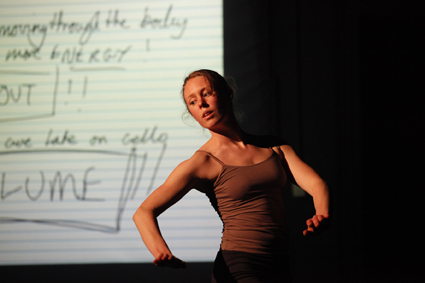

Chris Williams’ Il Pleut, Fresh Meat, 2011

photo Melody Eötvös

Chris Williams’ Il Pleut, Fresh Meat, 2011

THERE WAS A PALPABLE BUZZ OF EXCITEMENT AS ORGANISERS GLUED THEMSELVES TO MOBILE PHONES, ENSEMBLES REHEARSED LATE INTO THE NIGHT AND COMPOSERS FROM AROUND AUSTRALIA BOARDED BUDGET FLIGHTS IN THE LEAD UP TO FRESH MEAT 2011. PRESENTED BY MELBOURNE RECITAL CENTRE IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE NEW MUSIC NETWORK, THE EVENT SHOWCASED THE STRIKING DIVERSITY OF STYLES CURRENTLY BEING DEVELOPED BY EMERGING COMPOSERS. SIGNALLING A REFLECTIVE MUSIC SCENE, COMPOSERS COULD BE HEARD BALANCING TECHNICAL EXPERIMENTATION, METAPHYSICAL ANALOGY AND PROGRAMMATIC DEPICTION TO STARTLING AND THOUGHT-PROVOKING EFFECT.

the finite, the infinite & the infinitesimal

Melody Eötvös’ string quartet and Annie Hui-Hsinn Hsieh’s quartet for clarinet, violin, viola and piano were united by a Bartokian minor-mode lyricism and a rather sad metaphysics. In Olber’s Dance in the Dark based on Olber’s paradox—that the universe could not be infinite as then the night sky would be bright with an infinity of stars—Eötvös’ strident chords of increasing density gradually confirmed the universe’s finitude. A deflating proposition, until the increasing wonder of the chords’ harmonic invention leads one to contemplate the possibilities that are opened up by restriction, in this case the universe of tonal constellations.

Hui-Hsinn Hsieh’s Towards the Beginning

Hui-Hsinn Hsieh’s Towards the Beginning conjures a Taoist, cyclic universe. However, the interest of this piece is not in the ABA form that arises from its subtext, but in the composer’s use of timbre. Multiphonics—combining a fundamental tone and a higher, harmonic tone—on the clarinet and strings produce an ethereal atmosphere from which a fragmented, modal dirge emerges. The coalescing snatches of melody are shattered by a chord from the piano, leaving the original shimmering surface in its wake.

Chris Williams’ percussion piece Il Pleut (based on Apollinaire’s poem) builds textures from infinitesimal points of sound. Through a sort of instrumental granular synthesis, washes of attacks build into blocks of sound that shift as the percussionists explore different instrumentation. As an examination of “the tension between the musical finite and infinite,” the piece was most interesting at the threshold between a sound and its parts, when staggered attacks were on train to coalesce or break apart.

sound encounters

Three works on the program looked at the way different instruments altered the same musical material. This idea is very, very old. At least until the advent of electroacoustic music the main way to discuss timbre was with reference to instrumentation. As such, musical ideas have always been subject to instrumental comment, even—I would argue—when instrumentation was not indicated in scores, at which times convention would have dictated the distribution of instrumental resources. It is therefore up to performers or a program to keep such naked exploration interesting.

Timothy Tate’s Departures focuses on sonic analogues between the clarinet, viola and piano. Viola pizzicati are interpreted as clarinet tongue slaps and plucked piano strings while glissandi become runs and arpeggios. With rapid question and answer phrases, the composition reminded me of a slapstick Loony Toons score, though this comic air was not to be found in the performance.

Alex Pozniak’s From the Formless, on the other hand, was hilarious. Favouring superimposition over juxtaposition, From the Formless has a crowded and chaotic texture. Simon Charles, Peter Dumsday and Jonathan Heilbron played up the comical energy of this pandemonium as the instruments, or rather the instrumentalists, simultaneously tried to make the scratchiest, burbliest, quackiest noises possible.

Such compositional devices do not always have to be humorous. Luke Paulding’s quartet for flute, clarinet, double bass and percussion combined juxtaposition and superimposition of timbres in graceful sound poetry. Titled In Her sparkling flesh in saecular ecstasy, the point of the work was not to find sonic analogues, but neighbouring sounds that lead the ear along the curves of a sonic sculpture: to be precise, the sonic sculpture that Paulding draws from Richard Wilbur’s poem “A Baroque Wall Fountain in the Villa Sciarra.” The largely impressionist sonic palette flows and splashes like Wilbur’s fountain: cymbal crashes and an arcing ejaculation from the clarinet release the cascade that rushes through rattling skewers and strikes of the double bass bow on the strings (“flatteries of spray”), shimmering woodwinds (“a clambering mesh of water-lights”) and a truly incontinent “ragged, loose collapse of water” played by all. The work concludes much as it begins, with the somehow obscene burbling of a clarinet mouthpiece in a glass of water.

percussive programming

Amy Bastow’s Never OdD or Even, Fresh Meat, 2011

photo Melody Eötvös

Amy Bastow’s Never OdD or Even, Fresh Meat, 2011

Amy Bastow’s Never OdD or Even is a musical take on Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Having suffered from OCD and Tourette’s Syndrome as a child I did feel a little uncomfortable when the ensemble entered the salon twitching and counting their steps. “Is this funny?” I asked myself. I suppose so, even if I couldn’t shake a certain sadness that stole over me during the performance. OCD is a living nightmare. The compulsion itself is less like a desire to be fulfilled than a pursuer in those dreams where you can’t run properly. Bastow brilliantly captures the persistent, exhausting nature of OCD. Right when it seems the driving rhythms, mockingly major-mode additive phrases and frenzied tempi have ceased they are back, louder and faster than ever. I particularly like Bastow’s wearied lyrical passages that express something of the beleaguered exhaustion proper to a day of obsessive counting, retraced steps and compulsive twitching. With a similar demonic force, Anthony Moles took the idea of small machines within larger machines to produce a driving solo piano piece, just as manically as mechanically performed by Peter Dumsday.

Invigorating works that would otherwise lie dormant in computer files, the performers’ commitment deserves special mention. In particular, clarinettist Karen Heath seemed to hold many of the performances together with the gestures and physical intensity proper to performing in small ensembles. The power of the performer was evident not only in the above works, but in the inspired execution of Joseph Twist’s jazzy Le Tombeau de Monk, Mark Wolf’s grotesque Hamarøy Troll, Mark Oliviero’s electro-acoustic memoir Tanox, and Nicole Murphy’s composition for ballet Eve.

Melbourne Recital Centre & New Music Network, Fresh Meat, 2011, composers Amy Bastow, Alex Pozniak, Annie Hui-Hsin Hsieh, Luke Paulding, Timothy Tate, Melody Eötvös, Chris Williams, Nicole Murphy, Anthony Moles, Mark Wolf, Mark Olivero and Joseph Twist; Salon, Melbourne Recital Centre, Aug 25

For more on young composers see review of Breaking Out at Totally Huge New Music 2011

RealTime issue #105 Oct-Nov 2011 pg. web

© Matthew Lorenzon; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Katarzyna Sitarz, 2011 Tanja Liedtke Fellow

photo Flex

Katarzyna Sitarz, 2011 Tanja Liedtke Fellow

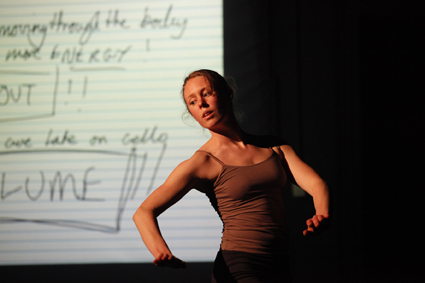

I SPOKE WITH KATARZYNA SITARZ, THE 2011 TANJA LIEDTKE FELLOW, AFTER SHE HAD SPENT TIME ON CREATIVE DEVELOPMENT WITH HER AUSTRALIAN COLLABORATORS IN MELBOURNE AND WORKING IN SYDNEY WITH CHOREOGRAPHER LUCY GUERIN, DIRECTOR SIMON STONE AND ACTORS AND DANCERS ON GUERIN’S COMMISSIONED WORK FOR THE 2012 BELVOIR SEASON. AFTER OUR MEETING SHE WAS ABOUT TO SPEND SEVERAL MONTHS EXPLORING AUSTRALIA. I ASKED HER ABOUT HER BACKGROUND, HER TRAINING, THE EUROPEAN ARTISTS SHE’S WORKED WITH AND WHAT ATTRACTED HER TO AUSTRALIA AFTER WORKING WIDELY IN EUROPE.

Where are you from originally?

From Poland—the northwest. I lived in a town called Szczecin, which is close to the German border, very close to Berlin. After finishing high school, I left to go to university to study Russian Philology, a mixture of linguistics and culture. I spent a year there and then I left for Holland to study dance and choreography.

That’s an interesting shift from Russian Philology.

It’s a bit far away, but at the same time not so far. I’d been dancing since I was really young but it was always just for fun. Basically it was my mum’s solution to make me exhausted at the end of the day because I was this restless, hyper kid. It was never really like a ballet school with a focus on being professional but about having a good time, developing in different ways but more for pleasure. I continued that from age three or four so I’ve been always dancing and always doing different things at the same time—I played a lot of sport; I played piano for eight or 10 years.

I never thought about dancing professionally because at that time the borders were still closed, it wasn’t really an option. Also, I was never in a ballet school so that path was closed for me. Then in 2005 when we entered the European Union, suddenly the borders were open and it was easy to travel. No visas, no green cards, all those crazy immigration procedures. Suddenly there were opportunities to go abroad where I knew there were schools where you could get a higher education in dance, choreography and performing arts. I had worked in the opera in my hometown and later I was dancing part-time in theatre. I realised hey I’m really enjoying it and thought, okay, if I want to do something about it, I have to do it now when I’m 18-19. That was my choice to move to Holland.

The school (Rotterdam Dance Academy which is now called Codarts) was considered at the time one of the best in Europe and I had some friends there so I knew that the school was pretty technical. This was a challenge because I wasn’t really sure I would be accepted. At the same time, I thought what I need is technical support and a professional approach. The Dance Academy is connected with the Music School. The dance school at that time had a dance performing department, choreography department and teaching department. In my second year I made a choice to study choreography. So I was kind of doing the whole program.

Did you keep dancing or did your focus shift to choreography?

Both, which meant that I spent in the school from the early morning till very late—like living there! I love to work for people and with people, to collaborate just to learn how they deal with things. At the same time I love creating myself and I like to have time where I can say, okay that’s my little project and I want to do what I want, to develop, to see what’s possible.

The academy, from a choreographic point of view, was very much based in movement, so our work was “movement-based” which wasn’t necessarily always our interest. But we all had very different projects. We had to create different pieces and in Media Technologies we were creating our own little dance movies. We collaborated with dramaturgs and with set designers and composers. It was a big openness. What I’m saying is there was a focus on working with concepts but not in a highly conceptual way.

What kind of things interested you conceptually?

A concept gives me a certain frame, a frame of mind and a certain interest—a theme that I’m interested in. For example, if I’m creating physicality on stage or even researching physicality, there is a certain approach. So I can establish some kind of physicality, which will be each time different. I’m really interested in movement research—which kind of body do I need as a performer, which kind of physicality, what are the qualities, where do they come from and why. Questioning. I try not to get stuck in one particular comfortable movement or quality that my body naturally has or some people that I work with naturally have—pushing the borders. I’m very interested in basically being uncomfortable. I find it now as I’m in a transition moment where I’m not really established but neither am I just starting out. I’m in this zone where there are lots of options and I’m a little like a sponge absorbing and seeing how does it feel.

You graduated in 2009. So you’re absorbing lots of things but are you also finding you’re developing a conceptual rigour that’s your own, or a stylistic vocabulary, or is this part of the reason you’re here? Can you see something emerging that is “you”?

Yes definitely. Even in absorbing things, there is a certain process of selection I’m making consciously or unconsciously just because I’m interested in some things. But in a way I know I have quite a particular way of moving or approaching things. At this moment I’m also trying to challenge that. So I think I’m escaping being labelled or labelling myself. Each time I get into this zone, I go “not yet.” I don’t know why that is, if I’m scared or…

What about influences? You’ve worked with some interesting people Rosas Ensemble, Rui Horta, La Fura dels Baus. Have these offered you a variety of experience or inspiration?

I’m trying to work with as different people as possible. That way I can get into many different places within myself also. The latest work I did with Rui Horta; I moved to Portugal for that. So apart from the artistic journey and our collaboration it was also my personal journey into that culture and discovering people and a certain mentality and country. Rui Horta is a fantastic artist and person so to work with him was just a great pleasure. He’s very open in his vision and his approach.

He is very appreciative of people and of the effort they make. He’s working on the potential of people. At the beginning I was surprised he was very positive and he just loved what we were doing and he was shaping it, but never from a very negative place. I found this a very beautiful way of working. I’d like to cultivate that kind of approach in my own collaborations.

What different kinds of demands do they place on you as a dancer?

I’m adapting. This is what I like about being a freelance dancer/choreographer/performer, at least at this stage not being with a particular company or choreographer. I empty myself each time I work with somebody new. Of course, I carry history and my background and I cannot escape myself but it’s like each time I would work with someone I try to empty the cup in order to have a place, time and space for things to come, to arrive, to fill in. This is kind of like a process. It’s not always comfortable or always something that I know exactly. It’s always this being lost and not knowing. But I find it a beautiful approach.

In the range of work you’ve done, how much of it is based on steps, or tight knit choreography? Or is it a much more expansive experience?

I’m not really good at remembering steps. Of course, there is choreography that must be learned and this is my job. I enjoy improvisational structures. With Rui Horta, there were huge theatrical aspects. I kept speaking on stage from the very beginning to the end, either to myself or louder to the audience. That work was very theatrical, very physical. Some works are based more on improvisations and constant composition while performing. Some are more musical—with Rosas Ensemble it was collaboration with musicians. We were even not so much dancers as performers. Different projects demand different approaches.

What drew you to come to Australia?

This is actually a very interesting story. Obviously, I applied for Tanja Liedtke scholarship. But just before applying, somehow, everywhere I went—I’m travelling a lot in Europe; I don’t really have a stable place—I would bump into Australians. And I would get along really well with them. I found some qualities of being and approaching life and co-existing, very special—unique. Some qualities maybe I didn’t have. So I started to question what is this land Australia that produces such a people? That was before I applied. Aside from this the scholarship program was amazing and really appealing.

What have you been doing here?

The application consisted of my CV, my motivation, why I find it interesting for my future development, what I can offer, what I can share. It’s a lot about collaboration and sharing. The Tanja Liedtke scholarship has two parts. One is running your own creative development, which can be anything—it’s a really open field. The second part is working on a creative development with a local choreographer, which in my case was Lucy Guerin. So I had to write my own concept, which was very much based around collaboration to develop a short work—a blind date.

Working with other dancers or other artists in general?

Other artists. My concept for that project is something new and it started from before coming Australia. It’s basically a concept of home. I was questioning it from different angles: what is home; what does it mean; is it a place; is it a mental state? I found actually coming here to Australia really interesting for the project because I would really be away from my zone, my field, my home, all the way to the other side of the globe, standing upside down! The other part of the concept would be collaborating with people I didn’t know—other artists, not necessarily dancers. Actually I didn’t work with dancers. I made a choice of working with a visual/media artist, a dramaturg/actor/writer and a composer. This team also came together step by step. I was open for whatever was available. So it was a ‘blind date’ organised by Shane Carroll from the Tanja Liedtke Foundation who was taking care of everything.

Did you get much time to work with these people?

With Zoe Scoglio the visual/media artist, we had three weeks together. With all of them, we kept emailing before I came. So I shared with them the concept, not necessarily what I wanted to do—I didn’t know what we were going to be doing because I try to keep it open…it’s a collaboration, not me imposing a work on somebody. We started from sitting and talking and getting to know one another. With Matt Cornell whom I met last year in Vienna, we’d spoken before but we had one week together in the studio in the last week. Meantime Josh Tyler is based here in Sydney. He’s an actor/writer and dramaturg. We were emailing a lot and he was also writing some text because I was working with text and some approaches to it…he was in the studio with us for two days. So I had different ways of working with these people.

Do you feel that’s come to a satisfying stage of development?

It was more an experiment to see how we could merge together. We had a presentation at the end of three weeks, which was a compilation of different ideas we were trying out. All the time now that I look at it, it was more about generating ideas, not necessarily developing them further. Because the subject is so philosophical and broad, we could go anywhere—there were still some places we didn’t go.

Can you give me an example of something that came out of it?

Joshua Tyler, Katarzyna Sitarz, Zoe Scoglio, Home creative team

photo courtesy the artist

Joshua Tyler, Katarzyna Sitarz, Zoe Scoglio, Home creative team

We narrowed down everything and divided our work into three major parts, one being Home as a Body. We had two different things between Zoe and me: me being actually physically a ‘home’ for projection. We were projecting little versions of me dancing and using the surface of my body as a landscape. Then we went in a different direction into Intimacy and Absence of the Body. Again we were working with projections on my body. Zoe would be finding different objects or using her own body, her own hands and presence being projected on me. We went into Navigations—directions, searching for home, partly because we were talking a lot about nomadic cultures. Then we were working with walkie-talkies on an idea of Here, Near and Far but still having one point of reference. One walkie-talkie section involved setting one device in a place where we ‘stored’ people—part of the room. We made an architectural plan of a house just using simple white tape. We made a house and we guided people into a little room or a big room, spaces with very abstract borders because home can contain very abstract ideas and agreements between people. I welcomed people and then I left. I continued the journey outside. Mark preferred to create a really interesting soundscape so we were playing this through the walkie-talkie to create different spaces and different journeys.

We also made a short movie about being in a house but being homeless. We decided a slug is a snail with a housing problem. It was more about that mental and emotional state when you are in a place but you’re not really there. So you’re kind of lost. And then we set the physicality where I would just be constantly shaking and being out of any kind of control.

Is this something you might work on in the future or do you see it simply as something that you’re glad you’ve done?

Oh, I definitely see a future for it. There is so much potential. We did so many really interesting things that I feel that I need to digest it because it was quite an intense process—three weeks of brainstorming and making and finding a common aesthetic language. I would love to carry on with it, especially as it’s a subject that’s very present in my life.

What about your experience with Lucy Guerin?

That was a really interesting process. She was working with three dancers and three actors. And I was an ‘extra’ doing whatever I could share or do. I was really very much part of it while the research was going on, trying out different options and tasks and possibilities. Once Lucy started to shape the work a bit more, I stepped out in order to observe it. I was really glad I could participate in the process from the very beginning. So it’s not that I was joining something already underway. And the other thing was that because of the collaboration Lucy is making with Belvoir and the actors, she wasn’t in her comfort zone, in her field where she’s super under control. I could relate to this just because of my own experience. It was interesting to observe how she was dealing with things, approaching the work, because it was also research; how she’s shaping it, timing it, which kinds of tasks she’s setting. Another beautiful thing is just the way she works with people. Just as I was saying about Rui Horta, Lucy Guerin is such an amazing, beautiful woman who appreciates people and their effort and the qualities they have. It was a pleasure to be with all of them. The group was really great.

And all up it’s been a good experience for you?

It was a great experience. I’m not saying it was the easiest one because I had to find myself here, in the Australian mentality, the Australian approach towards things, finding ways to communicate with people, to have a common understanding which wasn’t always an easy thing just because we could look at one thing from very different perspectives. We would be speaking about something and after a few hours there would be a sudden ‘Okay! this is what you mean!’ It sometimes takes time and energy and leads to some frustrations, but…What I enjoyed a lot was coming here and being a little bit like a blank paper. I don’t know the people; I don’t know who’s who. I’m not engaged in any political whatever or social structures. It was a pleasure to see work, to like it or not, with this kind of approach. For a long time I haven’t had this. I felt like a little bit like this innocent child.

It’s good that Dance Massive was on and there was so much for you to see.

That was really great. What I would like to add is how grateful I am for the opportunity and to all the people I met on my path and who supported the project. Shane Carroll was just an angel looking after everything—even making sure I looked in the right direction crossing the road! I found people very open and very supportive. The Arts House team were great for my collaboration. Whatever I asked, there was never a ‘no.’ Almost everything was possible. There was always trying, always options. I’m not used to working like that. Very often I work in surroundings that would be like “no, this is not possible” or “go and deal with it yourself.” So this is something ‘wow’ for me. Big support and very friendly community and very open people.

For information about the Tanja Liedtke Foundation and Fellowship go to http://www.tanja-liedtke-foundation.org.

RealTime issue #105 Oct-Nov 2011 pg. web

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

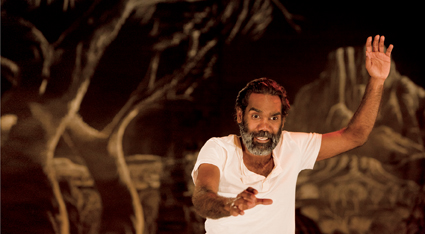

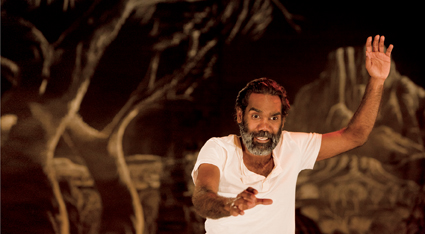

Trevor Jamieson, Namatjira

photo Brett Boardman

Trevor Jamieson, Namatjira

OF ALL THE AXIOMS BY WHICH WE EVALUATE A WORK OF LIVE PERFORMANCE, ITS SUCCESS IN MEETING ITS AUDIENCE SEEMS RELATIVELY IGNORED. I DON’T SIMPLY MEAN THE RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN A WORK AND THE BODIES AND MINDS OF THOSE WHO WITNESS IT—THERE’S NO LACK OF DISCUSSION AROUND THE FOURTH WALL, IMMERSIVE THEATRE AND THE LIKE. BUT WHEN IT COMES TO THINKING THROUGH WHO IS ATTRACTED TO A PARTICULAR WORK AND WHY, IT WOULD SEEM A MATTER OF MARKETING RATHER THAN AESTHETICS. IT’S FOR THIS REASON THAT TOO MANY THEATRE-MAKERS, WHEN ASKED ABOUT THE ASSUMED AUDIENCE OF THEIR EFFORTS, CAN REPLY ‘EVERYONE’. WHICH TOO OFTEN AMOUNTS TO ‘NO-ONE.’

Four recent productions to grace Melbourne suggested more nuanced and considered answers, playing on audience expectation and knowledge and seeming to understand that a work that will appeal to a universal audience is as unlikely as the existence of a universal human. I’ve never come across an instance of art that hasn’t found its detractors; to acknowledge this is a primary step for artists, and to proceed anyway an act of essential, necessary bravery.

big hart, namatjira

Big hART’s Namatjira takes a bold stance in this regard. The work is an exploration of Australia’s most famous Indigenous painter, Albert Namatjira, whose art was among the first to gain widespread recognition in white Australia from the 1940s onwards. But far more than straightforward biography, Big hART incorporates a mode of direct audience address that denies its viewer the opportunity to experience the work as if through a one-way mirror. From the outset performer Trevor Jamieson speaks to his audience, but not just any audience: Namatjira assumes that its audience is white.

As a work with a heavy touring schedule, I can’t tell how this gambit would travel, but in the inner-city surrounds of the Malthouse it seemed disarmingly appropriate. Jamieson jokes about progressive white Australians who might want to give their children Aboriginal names, and wonders whether a service should be established to advise them on this. He prods at the white nervousness surrounding Indigenous protocols and anxieties about causing offence through sheer ignorance. Most of all, Jamieson subtly circles around the expectations his audience may have towards something we’ve come to call “Indigenous theatre”—what does that mean? Is it a label that liberates or confines? Can it do both?

If it has to be labelled, Namatjira might be thought of as postcolonial Indigenous meta-theatre; it doesn’t merely give voice to the history and experience of Aboriginal Australia but questions how that voice is heard, what conversations it is part of. It’s a rich celebration of a fascinating figure, but also one rife with irony: in recreating the painter’s rise and fall in heroic terms, Jamieson notes that this is “the story whitefellas want to hear… the only story people seem to remember.” Alongside this drama we are given counter-narratives, most obviously incarnated through Jamieson’s co-performer Derik Lynch and the descendants of Albert Namatjira himself who work on a massive chalk mural dominating the back of the stage throughout the piece. They are reminders of the presences which persist beneath any official telling of the past, of the continuities which cannot be captured through biography alone, since a biography must perforce end, while a life’s legacy is more complex.

Timothy Ohl, Fiona Cameron, Look Right Through Me, KAGE

photo Jeff Busby

Timothy Ohl, Fiona Cameron, Look Right Through Me, KAGE

kage, look right through me

Another Malthouse production engages with the legacy of an icon who is still very much at work. KAGE’s Look Right Through Me took as inspiration the cartoons and drawings of Michael Leunig, an artist of whom no Melburnian would be unaware. But how to do justice to an oeuvre that carries with it the weight of many decades, and to an iconography that has very specific significances to the legion of fans Leunig has accrued over this time? To attempt an act of translation, in this sense, opens up the possibility of getting it ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ according to what meanings each individual reads into the artist’s work.

It helps that KAGE’s physical theatre methodology is very much based around images, but director Kate Denborough wisely avoids a literal staging of the Leunig with whom we are familiar. Rather, she has pieced together an independent narrative that seems to riff on the artist’s canon like a jazz take on a standard score; the cartoonist’s themes and characters rise and fall like a refrain, but the work itself doesn’t rely on recognition as its fundamental source of meaning-making. Of course, Denborough knows that in this city at least recognition will have its own potency, but this is a work that would make as much sense to an audience unfamiliar with its source.

On its own terms, Look Right Through Me has strengths and weaknesses. Some of its vignettes, which chart the course of an alienated everyman shadowed by his own childhood, are of unarguable impact: a rope swing dangling from a tree takes on the grim aspect of a noose; a patch of grass becomes both comforting bed and unsettling grave. It may be in the relationships between performers that Denborough’s work really shines here, and her choreography is both deftly athletic and emotionally charged, producing a very visceral realisation of the dynamics that connect and divorce humans from one another. At other times, such as an extended sequence of carnivalesque abandon, both the narrative and its emergent themes become more muddied, and it’s at these times that I found myself turning back to the artist and wondering if there was an element of his work that I was missing and which was vital to interpret the on-stage events. These were rare moments, however.

Mary-Helen Sassman, Liz Jones, Special, The Rabble

photo Marge Horwell

Mary-Helen Sassman, Liz Jones, Special, The Rabble

the rabble, special

The Rabble is a company equally interested in the power of image-based theatre, often producing far more disorienting results. In the case of Special, this isn’t a bad thing. For much of the shortish piece I didn’t really know what was going on, but this didn’t hinder enjoyment of it in the least. Mary Helen Sassman plays a belligerent, heavily pregnant woman harassed by her equally self-obsessed mother; they inhabit a strange space of hyperreal colour dominated by a massive mound of sand. Their interactions are fragmented, not quite nonsensical but obscure in nature, and the whole comes across like Beckett directing a children’s party. As their condition of static animosity plays out, however, a series of bizarre rituals is introduced whose intentions are left deliberately open to the audience, but which clearly possess an internal logic to which we are not privy.

With the slightest of changes Special could be wilfully obscurantist, an exercise in self-indulgence and a frustrating severing of signification and referent. But director Emma Valente somehow pulls it off marvellously, keeping her audience onside even while maintaining a constant distance between performer and viewer. She seems to acknowledge that we understand this mode of playmaking and expect more from absurdity than a basic deferral of meaning. Rather, the strangeness of what we see seems as real as any more rational presentation of plot and character; we may not understand the motivations that compel these figures, but how many of our own drives are unquestioned and equally odd, when put in the spotlight?

Thrashing Without Looking, Aphids

photo Ponch Hawkes

Thrashing Without Looking, Aphids

aphids, thrashing without looking

And into the spotlight is exactly where Aphids’ Thrashing Without Looking thrusts its audiences. Indeed, whether ‘audience’ is an applicable term here is moot. The work makes its participants both spectator and spectacle, simultaneously, as half the crowd is equipped with ingenious headsets that channel the footage being shot by a range of video cameras moving around the room. The other half direct the course of events, which are established according to the kitsch conventions of karaoke music videos—a romantic dinner for two, a turn at a pumping nightclub, a slow dance that ends in heartbreak. Those given the active roles are watching themselves at a distance while playing out each scene, and it’s a profoundly giddy experience. If the pleasures of classical cinema are of the voyeuristic kind, giving the passive viewer a sense of power over what is depicted on screen, this dynamic is up-ended when the gaze is directed back on itself.

Thrashing Without Looking was a short, sharp shock that managed to provoke questions about the place of the audience in a way quite rare these days. Hopefully it will go on to enjoy an expanded life in some form, as these are questions that deserved to be asked, and in this case at least, were a joy to be part of. (See also Jana Perkovic’s review)

Malthouse Theatre and Big hArt, Namatjira, writer, director Scott Rankin, performers Trevor Jamieson, Robert Hannaford, Derik Lynch, Kevin Namatjira, Lenie Namatjira, Michael Peck, Elton Wirri, Hilary Wirri, Kevin Wirri, designer Genevieve Dugard, composer Genevieve Lacey, costumes Tess Schofield, lighting Nigel Levings, sound design Tim Atkins, Malthouse. August 10-28; Malthouse Theatre and KAGE, Look Right Through Me, concept, direction Kate Denborough, creative collaborator Michael Leunig, co-devisers, performers Craig Bary, Fiona Cameron, Timothy Ohl, Cain Thompson, Gerard Van Dyck, composer Jethro Woodward, designer Julie Renton, lighting Rachael Burke, Malthouse. September 7-18; The Rabble, Special, director, Emma Valente, concept Emma Valente, Mary Helen Sassman, devisor-performers Liz Jones, Mary Helen Sassman, lighting, sound, composition Emma Valente; La Mama Courthouse, August 4-21; Arts House and Aphids, Thrashing Without Looking, creators Martyn Coutts, Elizabeth Dunn, Tristan Meecham, Lara Thoms, Willoh S Weiland, producer Thea Baumann, sound designe Alan Nguyen; Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall. 3-7 August

RealTime issue #105 Oct-Nov 2011 pg. 29

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

John Tonkin, Metacognition

courtesy the artist

John Tonkin, Metacognition

STEPPING OUT OF THE LIFT INTO THE NEW BREENSPACE GALLERY ON LEVEL THREE OF A CONVERTED WAREHOUSE BUILDING, IMMEDIATELY BRINGS YOU INTO THE PENUMBRA OF THE GALLERY SPACE. RANGED AROUND THE WALLS ARE FRAMED IMAGES LOOKING CONTEMPORARY AND COLLECTABLE, FLICKERING WITH MOVEMENT, RATHER THAN MADE STATIC WITH PAINT. JOHN TONKIN IS A SEASONED MEDIA ARTIST WHO LIKE OTHERS, IS PROBING THE TASTES, DESIRES AND WALLETS OF THE COLLECTORS.

Can ‘progress’ be made in this endeavour, or is interactive moving image work the genuine ephemeral article claimed (but rarely delivered) by earlier movements of art makers?

The four works presented, like Tonkin’s earlier work, break ground in an amusing and convincingly stable way; while interactive multimedia installations can be plagued by inadequate technology or buggy preparation, not so here. He begins by renaming the phenomena “responsive video,” thus avoiding troubled histories and focusing on the predominant contemporary art form, video. Approaching one of the floating frames causes the flickering image to animate, to run forwards or backwards, or to in some way change its appearance, or cut to another shot.

The pieces are developments from Closer: eleven experiments on proximity seen at Performance Space, last year (RT100). Those interactive encounters were more casual than the current show, tucked away in various corners of CarriageWorks; prosaic images of a rolling drink can caught at the top of an escalator, or a boiling kettle, all controlled by our movement into confined stall-like spaces. Emphasis is on the ordinariness of that physical activity and its effect on the perceived image.

This is a novel and profound ability, to influence the quality of motion in the image; it is an extension of Deleuze’s ideas of the time-image and its perception: “A flickering brain, which re-links or creates loops – this is cinema.” No longer is the motion picture confined to analogue and linear sequencing; in the digital domain, as many of us have been pursuing, sequence is determined frame to frame by the participant selecting, knowingly or not, from a database of moving image files. The artist determines the rules and the materials applying to the collection that the participant will explore.

John Tonkin, Metacognition

courtesy the artist

John Tonkin, Metacognition

A biology of cognition, the title of one of the pieces in the exhibition, is key in providing the only shock in the show—approaching the screen causes a large face to suddenly appear from the murk to stonily eyeball the viewer while intoning briefly, mumbled and indistinct, phrases related to the title (referencing the 40-year-old seminal essay by Chilean biologist, Humberto Maturana). Attempts are made by the participant to devise various choreographic strategies and clarify the utterances. Is there a narrative, a sequence meaningful to what is not present here? A conclusion, if there is one, cannot be drawn, other than bringing to mind the considerable research developed since the essay’s appearance. Andy Clark, among others, more recently described the external environment, actively structured by us, as a source of cognition-enhancing ‘wideware’ containing external items such as devices, media, notations etc, that scaffold and complement without replicating biological modes of computation and processing.

Tonkin floats these ideas, leaving meaning beyond the immediate experience of the work in abeyance: avoidance for some, completion for others.

Closing the loop of fractions of time caught in memory cycles—suddenly recalled as thresholds are crossed, as proximity is shortened—is simulated as we approach the image of a window frame in Selective Attention. Focus changes to the plane of the glass and then to the rain falling beyond, then on retreating, returning to the ‘warmth’ of the interior. Subjectivity comes to the fore and the window through which we stare is the mirror of past events. Perhaps these feelings are the reinforcement sought by collectors, who are prepared to forgo the tenuous material basis and investment potential of their artefact?

As an artist who is also a programmer, John Tonkin’s long term engagement with novel interfaces for visual databases goes back beyond the 1990s and currently explores the recent addition of the Kinect sensing device to the tools available. Titles of the works, however, emphasise the theoretical underpinning of the ongoing investigations: Direct realism is like a still image of light refracted through glass and vegetation that begins to twinkle in movement as you draw near. On approaching the image of a seated person gazing at the screen before him in Metacognition, a street scene on the screen expands to be replaced by an image of feet walking in the bush, or a garden. It becomes possible (if the game is played) to enter different spaces within the work, to keep up with the walker; the framing of these adventures becoming the description of cognitive function being applied, from moment to moment.

John Tonkin, A Biology of Cognition, Breenspace, Sydney, July 1-30; www.breenspace.com

RealTime issue #105 Oct-Nov 2011 pg. 28

© Mike Leggett; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Noni Cowan, Gestures, Theatre & Performance Studies Honours Project Performance, UNSW

photo Heidrun Löhr

Noni Cowan, Gestures, Theatre & Performance Studies Honours Project Performance, UNSW

IN PART 1 OF THIS SURVEY OF AUSTRALIAN CONTENT IN THE CURRICULA AND SYLLABUSES OF COURSES IN AUSTRALIAN THEATRE AND CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE IN TERTIARY EDUCATION, IT WAS CLEAR THAT THERE WERE SOME VALUABLE RESOURCES AVAILABLE IN PRINT AND ONLINE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS, BUT ALSO MUCH THAT WAS MISSING.

I concluded that “there was a strongly felt need to be able to understand and teach Australian performance on its own terms but within the framework of national and international perspectives that this country has struggled so long to attain.” Here are further responses to my query to academics about how and where Australian content fits in their courses.

university of melbourne

Peter Eckersall, Associate Professor of Theatre Studies in the School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne, wrote to me that his subject, “‘Live Art Beyond Theatre,’ addresses many contemporary Australian artists and practices (and the RealTimeDance portal is a remarkable and helpful teaching resource). Our teaching tends not to be based on ideas of national arts practices, however, and Australian artists are discussed alongside, in comparison to, and in collaboration with developments, events and trends internationally. We also have Master of Arts and PhD students who are working on contemporary Australian performance. Some of these projects are focused on historical practices from the 1960s-1990s. Others are focused on contemporary performance works. A number of these projects have been/are being undertaken with creative components.” Eckersall identifies “a tendency to think about arts practices more regionally, locally and conversely more globally. Australian artists and practices have become so diverse that we often discuss them with a focus on more specific, or more diverse, analysis and critique. I would say that it is not the arts practices that are elided, but the notion of an ‘Australian artist’ and what this means is more complex and sometimes less meaningful.”

Eckersall also believes that “there is a need for more publishing on contemporary performance. There are many more research articles and documents than books …There are some good resources such as Ausstage and RealTime but there is a need for more perspectives and more ways to disseminate findings.”

murdoch university

Helena Grehan, Senior Lecturer in the English and Creative Arts program at Murdoch University in Western Australia, writes that the work of Australian artists is important “as the work reflects (often) issues and themes that are of interest to our students and the work is also often inspiring in terms of identifying what can be done in a constrained environment (fiscally).”

Grehan’s own teaching focus is “primarily on current practitioners (or at least from the last 20 or so years).” As for written resources she “directs students to available books but also RealTime (I use it all the time with my students), Australasian Drama Studies, Performance Paradigm (www.performanceparadigm.net) and About Performance (Department of Performance Studies, University of Sydney), which are all very useful, as are blogs. There could always be more but l’d like to focus on quality rather than quantity. Alison Croggon’s Theatrenotes is, for example, outstanding.

university of sydney

Laura Ginters, lecturer in the Department of Performance Studies at the University of Sydney writes, “Contemporary artists and their practices are central to what we teach and research in Performance Studies at the University of Sydney. While we don’t create work with our students, and nor do we train artists, the Rex Cramphorn Studio is filled, year round, with our artist-in-residence program and the work of these artists feeds directly into our teaching and research. For example, the 3rd Year Honours entry courses, Rehearsal Studies and Rehearsal to Performance, are based around a project where students observe, document and analyse two weeks of a rehearsal or creative development process taking place in the Rex. In 2011 the students observed My Darling Patricia at work on a new piece; last year it was Version 1.0, developing Table of Knowledge.

“In researching the company whose work they will observe, RealTime is often a valuable resource for students. Our Honours students also sometimes undertake their professional placement—they observe and analyse a full-length rehearsal process, then write up a casebook on the experience. This can be with one of the artists or groups of artists working in the Rex—or they will undertake such a placement with a company or artist outside the department: this could be anything from Tess de Quincey Co to Opera Australia. We also offer an Honours level course in Contemporary Performance (which is heavily focused on Australian artists), and this will sometimes include a practical workshop component for the students with a practising artist like Barbara Campbell.”

In second year, students commence performance analysis, seeing live performances and writing about them. Other courses—Embodied Histories, Theories of Acting, the Playwright in the Theatre, Playing Politics, Cross-Cultural Performance and Gender and Performance—”use the work of contemporary practitioners in dance, contemporary performance, performance art, and theatre and other genres. In my own Dramaturgy course in third year my students have had the opportunity to observe a director, actors, writer and dramaturg developing a new work for performance. And while we’re not training practitioners we’ve got a long history of practitioners coming to us for postgrad study—enjoying the chance to reflect on their own practice or a related topic.”

Study in this department is advantaged by having a large archive in print and video of performance documentation. Ginters is appreciative of RealTime, Currency House’s Platform Papers “and (a very few) good bloggers—like Alison Croggon and James Waites for “delivering interesting commentary and reviews of work I can’t see myself and/or won’t see reviewed elsewhere. Our own journal, About Performance, also often includes analyses of the work of contemporary practitioners: recent editions have included essays on ‘refugee theatre,’ the work of Back to Back Theatre, Marrugeku, Pork Chop Productions, Australian Dance Theatre and the Gathering Ground project in Redfern’s The Block, to name just a few.”

Ginters would like more books on contemporary practitioners, “and indeed their forebears: I’m writing a book on drama activities at Sydney University in the late 1950s and early 1960s has made me very aware of how little has been written about the pre-1970 era.” Often, she says, the primary material exists—”the ausstage project is a great example of this; so is the National Library’s Trove search function. Having more of RealTime’s earlier editions also available would be a terrific addition. Personally I’d also be thrilled if I could get access to the Sydney Morning Herald archives online after 1954 without having to visit the State Library in person!”

university of new south wales

Clare Grant, Lecturer in the School of English, Performing Arts and Media at the University of New South Wales, tells me that, “artists of late 20th and early 21st centuries such as The Sydney Front and Jenny Kemp are specifically studied in John McCallum’s survey course, Staging Australia, along with earlier Australian artists. In his Program and Repertoire course, close attention to current performance programming forms part of the curriculum.” The Introduction to Theatre course “refers to several contemporary performance makers such as Deborah Pollard, and from an earlier era, Ken Unsworth.” In Reading Performance and Multi-Media production, artists include Australian drag performance (eg The Kingpins), both live and mediatised, William Yang, Stelarc, Tony Schwensen, Australian dance companies, Mike Parr, version 1.0, Back to Back Theatre, Marrugeku, Guillermo Gomez-Pena’s Museum of Fetishized Identities, as well as local festivals.”

In the practical courses Grant teaches, students also see performance works— including media art, live art, ‘documentary’ performance, site-based work—in Sydney, “many of which involve the students or ex-students themselves…The work of Australian artists is vital to the department of Theatre and Performance Studies, especially as the work of students forms part of the contemporary performance milieu in Sydney. Many of the students work with practising artists through PACT Centre for Emerging Artists and Shopfront Theatre, often undertaken alongside their studies at UNSW.”

For 12 years Grant has produced an annual student devised work for the public. This year, however, she says the process “will shift to a number of smaller group shows created through contemporary performance-making practices. As well, each year a class of up to 35 solo performance makers publicly present their works.”

As for resources recommended to students, there are “extracts from Richard Allen and Karen Pearlman’s Performing the Un-nameable (Currency Press with RealTime, 1999) in various courses; Edward Scheer’s book on Mike Parr (RT102, p47); John McCallum’s Belonging: Australian Playwriting in the 20th Century (Currency Press, 2009); plus Marrugeku’s Burning Daylight in DVD and booklet form. But we always need more; any new documentation is taken up quickly and used; Australian work with the physical and the documentary could use more attention. Streaming options, which Artfilms is working to develop soon, are valuable and probably more economical. Many of us teach the works we happen to have on DVD courtesy of the performance makers themselves.”

The evidence in Parts 1 and 2 of this brief survey provides clear evidence of commitment of teachers to Australian performance content in their courses, not only turning to print and online resources but, in various ways, putting students in touch with artists in residence, encouraging them to see productions, teaching analysis, developing dramaturgical awareness, making works and placing Australian work in the larger contexts of overseas works and the issues of the day. Most teachers would welcome books on contemporary artists (as more commonly happens in the visual arts) as well as stronger, more available video documentation. The emergence of contemporary performance from the 1960s to 80s warrants particular attention.

artfilms

A very special resource is the Melbourne based artfilms (www.artfilms.com.au/) with its growing collection of Australian performance works and documentaries on DVD. Artists and companies include Jenny Kemp, Stelarc, 5 Angry Men, Trevor Jamieson (Nothing Rhymes with Ngapartji, a documentary about Big hArt’s Ngapartji Ngapartji), Melbourne Women’s Circus and others alongside their international peers. In the dance realm, Artfilms has works available from Chunky Move, Lucy Guerin Inc, Chrissie Parrott, Igneous, Bangarra Dance Theatre and Meryl Tankard. The company’s latest project, director Kriszta Doczy tells me, is its Australian Avant-Garde series featuring Nigel Kellaway, Mike Mullins, Ken Unsworth and the experimental films of Gary Shead with work currently progressing on a DVD about the Sydney Front. Artfilm’s director Doczy eagerly encourages Australian artists to make documentation of their performances available to universities, schools and individuals. You can read more about Artfilms in the December-January edition of RealTime.

Another valuable resource is the National Library Oral History Collection’s interviews with leading theatre professionals Peter Oysten, Richard Cottrell, Richard Murphet, Nicholas Lathouris, Alan Seymour and others conducted by James Waites. Waites has been conducting these “whole life” interviews with a variety of people in and outside of the theatre business (http://www.jameswaites.com/) since 1996.

Theatre/Performance education part 1 appeared in RT 104 – see article.

RealTime issue #105 Oct-Nov 2011 pg. 30

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

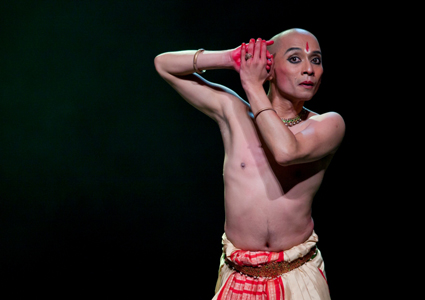

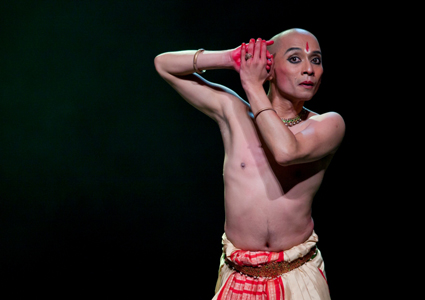

LASALLE acting students learn Kathakali performance skills

photo Crispian Chan

LASALLE acting students learn Kathakali performance skills

PROFESSOR PETER BOOTH, SENIOR DEPUTY VICE-CHANCELLOR AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY SYDNEY WAS RECENTLY REPORTED ON THE FRONT PAGE OF THE SYDNEY MORNING HERALD AS SAYING OF AUSTRALIAN ‘STAY-AT-HOME’ STUDENTS: “WE AS A UNIVERSITY THINK IT’S QUITE SAD AND WE’VE MADE A LOT OF EFFORT. IT WOULD BE BETTER FOR AUSTRALIA TO HAVE MORE POSITIVE PROGRAMS TO ENCOURAGE STUDENTS TO DO SOME OF THEIR STUDY OVERSEAS” (SMH, SEPT 14).

If you have ambitions in the performing arts and a strong interest in intercultural performance Singapore’s LASALLE College of the Arts might be the place for you with its embrace of Asian and Western traditions, excellent facilities and teacher-student ratios, as well as a related media arts faculty and film school.

For many years Australian universities have relied financially on a steady flow of overseas students, mostly from Asia. Although, after USA and Britain, Australia has the third largest take-up of foreign students globally, some 22% of the Australian university population, numbers have dropped by 9.4% in 2010-11. This is for a variety of reasons: fears of racist violence, the high Australian dollar, foreign student management scams outside of the university sector and, given new visa restrictions, decreasing opportunities for students to stay on in Australia after graduating (the Australian Government has recently relaxed somewhat the visa and post-study work restrictions to help universities sustain numbers and income). Another reason is the growing attractiveness of universities and other tertiary education institutions within Asia itself, particularly as the region plays a growing role in the world’s economy and develops its tertiary education sector.

Focusing on fine art, design, media and performing arts in a culturally rich island state LASALLE is located in Singapore’s cultural centre. Equipped with one theatre and two black box spaces, its Faculty of Performing Arts was spearheaded by Aubrey Mellor, a leading Australian theatre director, formerly Director of NIDA. Mellor was the Dean of the Performing Arts 2008-2011 and is now a Senior Fellow at LASALLE. The faculty has long had connections with Australia through a number of teachers working there over many years, for example composer Lindsay Vickery (now returned to Perth), virtuoso saxophonist Timothy O’Dwyer, NIDA alumnae Edith Podesta and a former concert soloist with the West Australian Symphony Orchestra, Bronwyn Gibson.

What LASALLE offers students is a rich cross-cultural, practice-based curriculum in the performing arts with a very attractive and highly competitive (not least for Australian universities) ratio of one teacher per seven students.

Venka Purushothaman, LASALLE’s Vice-President (Academic) and Provost, and Acting Dean of the Faculty of Performing Arts, says, “Singapore is at the ebb and flow between the west and east. LASALLE is therefore able to capitalise on the rich and diverse groups of visiting artists from North America, Europe and the Asia-Pacific. Through its link to UK film producer David Puttnam supporting the development of young filmmakers in Asia, The Puttnam School of Film, part of LASALLE’s Faculty of Media Arts, has also been instrumental in growing the creative talent base for the film and video industry.”

Wolfgang Muench, Dean of the Faculty of Media Arts, writes, “The philosophy within LASALLE is to encourage students to collaborate on interdisciplinary projects in order to learn new skills and sensibilities that will stand them in good stead when they enter the real world. Many of the Media Arts students have collaborated with dance and acting students on performances that showcase the diversity of the range of talents that are developed here.”