Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

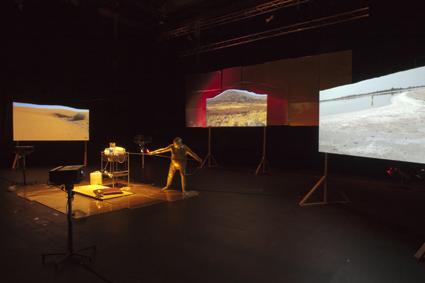

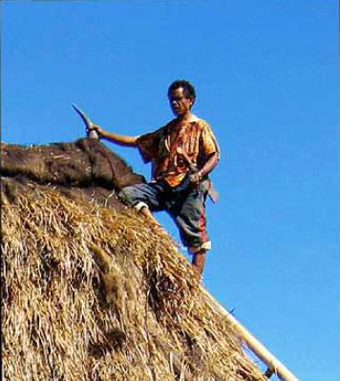

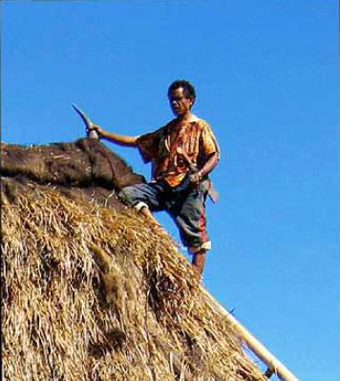

Philip Samartzis and Gabriel Nodea, field recording near Warmun

photo courtesy the artist

Philip Samartzis and Gabriel Nodea, field recording near Warmun

AFTER THE EPIC SCALE OF WARMUN’S DISASTROUS FLOODING EARLIER THIS YEAR, PHILIP SAMARTZIS’ SITE-DETERMINED SOUND WORK, DESERT, OFFERED AN OPTIMISTIC ACCOUNT OF A COMMUNITY RE-BUILDING. SAMARTZIS AND HIS ASSISTANT MADELYNNE CORNISH’S SUPERB FIELD RECORDINGS RETAINED AN IMMEDIACY THAT DERIVED FROM THE RAPID SEQUENCE OF THEIR SOURCING, MIXING AND PRESENTATION WHILE ON LOCATION IN THE EAST KIMBERLY.

Despite the richness of metal and diesel in the work’s composition, reflecting the extensive reconstruction that is underway, it was more suggestive of the gentler comforts afforded by the particularities of daily life. Weightier and more ephemeral elements were juxtaposed in a piece that arose out of human apprehension of the recent calamities rather than from any cosmological vantage point. The work’s relatively even tempo, warm tone and its indexical rather than metaphorical relationship to its context adeptly drew attention to the sonic pleasures of unremarkable things.

Samartzis’ residency was part of Tura New Music’s ongoing Remote Artist in Residence Program and was hosted by the renowned Warmun Art Centre. The five-week residency concluded with an evening outdoor presentation attended by not only the senior Gija painters who advised Samartzis and Cornish but also roadhouse staff, police officers, fellow arts workers from Kununurra and local families. The presentation of the work was followed by a barbecue and a ceremonial dance (joomba) led by elder Patrick Mung Mung in a sung and spoken commentary.

Unlike its presentation in Perth as a work for eight spatialised loudspeakers, the work was not presented in Warmun in an immersive way. Rather it was conveyed through a single speaker and accompanied by Cornish’s photographs taken during the residency at the request of Art Coordinator Maggie Fletcher who was concerned about providing support for the reception of the work. Samartzis did not hesitate to follow her advice and so this first version was mixed with the images in mind while ensuring that image and sound were not synchronised. At the performance, the audience was attentive and there were many moments of animated recognition with even the dogs responding to the canine sounds in the work. In subsequent days, the painters continued to check with Samartzis and Cornish that they had not forgotten to capture particular sounds before their departure.

Samartzis has undertaken residencies all over the world. Like most Australian artists, he has sought to prove himself in institutions, generally located in the Northern Hemisphere, that have an international reputation for their artform before travelling as a more mature artist to destinations such as Antarctica where the production and presentation of art is less prescribed. Despite his experience, however, Samartzis confessed to some anxiety about going to Warmun. He questioned the timing of the residency knowing that his presence would place demands on a traumatised community. Community members have spent most of the year in an evacuation camp in Kununurra and are now back in construction camp lodgings in Warmun awaiting the completion of housing.

Samartzis also felt the weight of the artistic traditions of the region, of which painting has the highest profile. Warmun is home to artists such as Mung Mung, Mabel Juli and Lena Nyadbi who command the attention of curators and collectors across Australia and beyond. Although Samartzis and Cornish connected with the Warmun school and general community as ‘art professionals,’ a feature of this residency was that they enjoyed a relationship with artists of a stature greater than their own.

As these factors were shaping his thinking about the project, Samartzis and Tos Mahoney, Tura’s Artistic Director, conceptualised the residency as creating alternative spaces for the discipline of sound. By framing the residency in this manner, Samartzis imagined himself working alongside artists who are primarily painters while also envisaging that the artists could potentially make sound works in the future. This transactional approach was underpinned by the intention from the outset of the residency that Samartzis’ work would enter the Warmun Art Centre Collection once its extensively damaged paintings have undergone conservation and been restored to the community.

Samartzis also generated his work during a time when there has been a revival of interest in carving and other three-dimensional processes at the Centre. During my visit to Warmun, artists told me of this development and their recent success at the Darwin Art Fair. Accordingly, it is appropriate to consider how Philip Samartzis’ presence might have played a part in the re-emergence of the Centre after the floods or even contributed to these artists’ approaches to innovation. Once Samartzis’ work was presented, the senior artists perceived it as not only confirmatory of their community but of shared artistic concerns. They identified with the representation of their country in the work but also with the sense of place inherent to Philip Samartzis’ methodology. Together with Samartzis and Cornish, they quietly acknowledged the sustaining nature of the artistic processes associated with both rendering sound and expressing Ngarranggarni (Dreaming) images and stories and how from the Warmun perspective they have always intersected.

See also Gail Priest’s review of Samartzis’ surround sound concert in Perth presented as part of Tura’s Totally Huge New Music Festival

Philip Samartzis’ residency was assisted by Tos Mahoney, Artistic Director,Tura New Music, Gabriel Nodea, Warmun Art Centre Chair and Centre Staff, Gary and Maggie Fletcher, Rosie Holmes and Alana Hunt.

RealTime issue #106 Dec-Jan 2011 pg. 40

© Jasmin Stephens; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

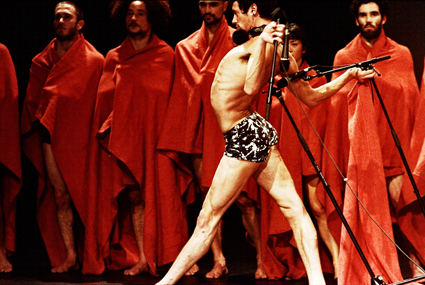

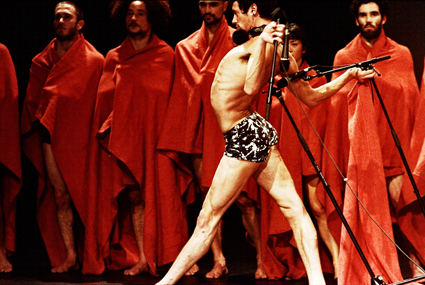

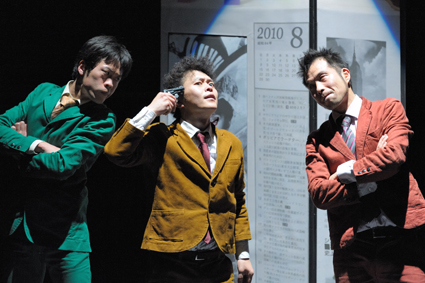

Alfredo Lagos, Israel Galván

photo Felix Vazquez

Alfredo Lagos, Israel Galván

ISRAEL GALVÁN, WHO APPEARED IN SYDNEY’S SPRING DANCE THIS YEAR, IS ONE OF A NEW BREED OF FLAMENCO ARTISTS IN SPAIN WHO ARE ‘RENOVATING’ THE FORM. A PRODUCT OF THE 19TH CENTURY, FLAMENCO IS A DANCE STYLE THAT IS BEING REINTRODUCED TO ITS MODERNITY BY GALVÁN.

The son of flamenco dancers Jose Galván and Eugenia de Los Reyes, Galván created his first work in 1998 and is currently touring a strong repertoire to major festivals. I spoke to him during his time in Sydney which followed my encounter with Galván’s work in France at Montepellier Danse (RT105). There, his 2005 piece Le Edad de Oro (The Golden Age) was an antidote to some dance work that seemed lost in an internally focused discourse, perhaps supporting the charge that contemporary dance is ‘eating itself.’ Translator Gina Marie Shrubsall describes Galván’s manner of talking as haiku-like, suggesting an empathy between his thinking and dancing. As described in RealTime 105 the latter has a refined simplicity of line, form and rhythm that is no less radical in its nature, .

Working with Pedro G Romero who provides dramaturgical support and commentary, Galván’s ‘revolution’ is perhaps best understood not as ‘moving with the times’ but as ‘updating the new aspects’ of the dance form. As Romero puts it, “my idea is that flamenco and the avant-gardes have the same route; they’re equally modern.” The idea that Galván is refocusing on the innovative within a tradition is supported by the way he describes his relationship to the historic avant-garde. “I haven’t worked much with the concepts of the avant-garde and not to the point where I have a nuanced interpretation of these forms. Although, at times, my choreography is influenced by the visual forms of Cubism and Modernism—this can be seen in the line of my dance. I do very much like the idea of being a ‘juggler of forms’.”

References to Walter Benjamin and Gilles Deleuze are peppered through Romero’s texts on Galván’s website, alongside impressive historical detail regarding the form, connections to modern artists working in other forms (Picasso, Lorca, Edgar Varèse, Orson Welles) and also references to some of the icons of modernity: steel, railways and machines. Galván’s art is understandable through this network of people, things and ideas, and his ability to both assimilate and share through choreography is noted by Romero in details like the passing of gestures across piano, voice and dance in Tabula Rasa (2004), and a humility in performance that decentres the star so that other elements can take centrestage; as Romero poetically puts it, “the floor designs itself under the shoe.”

This ability to assimilate and incorporate elements from a broad range of phenomena that sit beneath, or just make it to the surface of, movements and gestures, along with Galván’s ability to share the performance space with other outstanding artists (guitarist Alfredo Lagos, singers Fernando Terremoto and Inés Bacán) and attention-grabbing designs and direction (Pepa Gamboa and Belén Candil), hinges on a stage presence that is a very different from the many other flamenco dancers I have seen who present as ‘stars.’ Asked about this aspect of his performance, Galván describes a productive division between himself and the dancing. “I don’t bring the audience to my terrain, rather ‘I go to’ different personalities. You have to activate your personality during the dance… the steps and the dance will change your personality. It is not something concrete: personality changes and I like to be different things within the dance.”

Ultimately, his influences come either from within flamenco or beyond dance. “I am not directly influenced by particular genres of dance or particular dancers outside of flamenco. I’ve always liked to dance with a sense of freedom, to be influenced by all of the layers of life around us. Sometimes I will take a gesture from an anonymous dancer or draw on the movement of an animal. I’m also influenced by the choreography of the body in film and painting—for example, by Fellini or Rubens. You can see very choreographed intentions in the work of Rubens.” I asked if this could be described as a kind of sampling. He replied, “Because your body is the medium you are not sampling in a concrete way. Your body will change everything and perhaps you can’t even say it is an influence in a conscious way—what you arrive at is more of a ‘feeling’ or ‘air’ of the original sample.”

While cross-artform collaboration can still be seen as novel in contemporary dance, flamenco has always been a form where guitar, song and dance work closely together. This was reinforced in Le Edad de Oro when Galván and brothers Alfredo (guitarist) and David Lagos (singer) swapped roles. I asked Galván why the connection between the three artists seemed so intense in this work. “Musically I like to work in a particular way that is more open to changing the structure of flamenco dance. There is a well-established script that outlines the musical structure of flamenco dance. There is song and guitar made just for dance and then there is flamenco song and guitar which is constructed and performed without dance. I like to change the musical structure and use flamenco music which is not necessarily made for dance. I also search for a more open sonority and a guitar that sounds more classical.”

This playing around with the elements of the form continues right down to the detail of the choreographic language. Romero isolates the proportions, geometry, timing, forms, tonalities and gestures of flamenco as aspects that Galván manipulates, and what is remarkable in performance is the dancer’s ability to combine extreme transitions in several of these in one move. A familiar flamenco shape can be stylised through an attention to angles and perspective, while changing tone from epic to playful, risking balance and referencing a gesture just beyond apprehension. The moments of stillness are welcome amongst all this. “To be quiet in stillness—this is where you recharge the body in preparation for explosive movement and this is characteristic of flamenco.” Considering how far he has come in the last 10 years, we can be sure Israel Galván won’t be staying still long.

Interview translation by Gina Marie Shrubsall

RealTime issue #106 Dec-Jan 2011 pg. 27

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

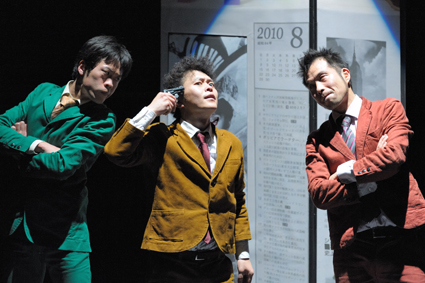

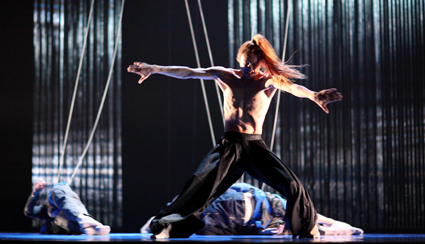

Anna Healey, Sean Marcs, Last Place to Go, 4Tell, youMove Company

photo Philippe Penel

Anna Healey, Sean Marcs, Last Place to Go, 4Tell, youMove Company

SEVEN BODIES FORM A CIRCLE ON THE FLOOR, CURLED UP, KNEES TO CHESTS, WHITE FLESH VISIBLE IN THE DARK. THEY BEGIN TO WRITHE: CRUNCH THEIR TORSOS TO PUSH HEADS UP TOWARDS THE CEILING. I HEAR THE BEGINNINGS OF AN AMBIENT WORLD MUSIC-SOUNDING TRACK. THE DANCERS ROLL AND SLIDE, PUSH THEMSELVES ACROSS THE TARKETT WITH THEIR ARMS. LEGS WORK HARD BENEATH UPPER BODIES. HEADS LICK AT THE CEILING. THIS DANCE IS FAST, ITS DANCERS AGILE.

Boundaries is the first work in 4Tell, a series of short pieces devised mainly by guest choreographers and performed by Kay Armstrong’s youMove Company. In the lead-up to the performance the company members have been encouraged to share their ideas and reflections with each other by contributing regularly to a blog. Throughout the show they each perform a short solo developed from one of their blog posts.

So, hot on the heels of Boundaries, company member Anna Healey performs a solo that breaks down the process of creating a blog post. Letters punched into a keyboard. Scrolls and clicks. Save draft. Preview. A post about the daily hopes and routines of an aspirational dancer.

Sandwiched between the dance works, the solos present 4Tell as the culmination of a mentoring process. They add an educational dimension to the evening. Most of them display an interest in process and are charged with a sense of self-revelation—this is us meeting the dancers on their own terms.

As the night progresses I begin to notice a consistent tone across the performances. Perhaps it’s because the same eight dancers perform in all of the pieces. I get to know them over the course of the evening, and by the final work, Multiplicity, I find I am looking out for familiar faces. But a certain quality is also recognisable across the group. There is control. There is muscle tone. And there is clear forward-thinking: these dancers always seem prepared for what is coming next.

In the second work, By Looking, a group of three moves in a tight spiral formation downstage. On their feet, the dancers sway in and out from one another, releasing tension and breath so far on the outward swing that I hold my own breath. But no one topples over. Later the dancers work in two pairs. There is body contact, the giving and taking of weight. Initially each exchange feels like a risk, but I soon stop expecting the dancers to fall. They may throw themselves around, but they know how to keep it together.

Angela French, 3rd Time Over

photo Philippe Penel

Angela French, 3rd Time Over

The only work choreographed by a youMove company member is a solo developed by Angela French with mentorship from Kay Armstrong and Force Majeure’s Kate Champion. French appears on stage in a navy blue dress, hair parted fiercely down the centre. The dress is tailored. A shimmer in the embroidery. There is music: a recorded string orchestra that plays a fast but steady course.

French’s hand floats about as though suspended on a string. Then it soars up over her head. Quickly her other hand flies up and pulls the first one down. The first hand continues with its exploration. I get the feeling that this dancer does not know what is coming next.

She traverses the stage. Halfway across, her legs give way beneath her. Again, it’s like she didn’t know it was coming, as if she actually lost all the strength in her lower body. On the floor she crawls, slaps a hand to the fleshy part of her arm and then to her thigh, pulling herself about. Up she gets, continues to travel—but her legs give way again. My stomach turns. Her hand floats up and she pulls it down; and again, and again. The pulling down starts to feel more like a slap on the wrist—like a self-correction.

I enjoy the rawness in this piece; the lean towards the irrational. Also, the way in which this dancer manages her body. It’s as if the dance happens to her, catches her off guard. And I enjoy the repetition. Sometimes there is such a range of content in choreography that I start to lose track, but this piece presents just a few things, thoroughly. All of this dawns on me gradually, as the evening progresses; as I take in the procession of shapes and ideas making their way across the stage.

youMove Company, 4Tell, curator, artistic director Kay Armstrong, guest mentor Kate Champion, company dancers Jay Bailey, Imogen Cranna, Angela French, Jayne McCann, Lauren McPhail, Melinda Tyquin, Anna Healey, mentee: Tracey Parker, guest dancer Sean Marcs, lighting Guy Harding, http://youmove.blog.com; www.youmovedance.com.au; Riverside Theatres, Parammatta, Sydney, Oct 27-29

RealTime issue #106 Dec-Jan 2011 pg. 28

© Cleo Mees; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

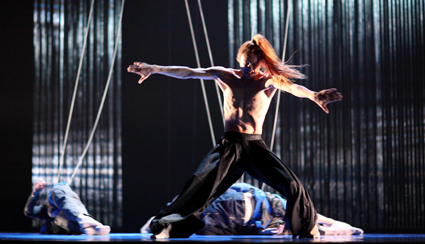

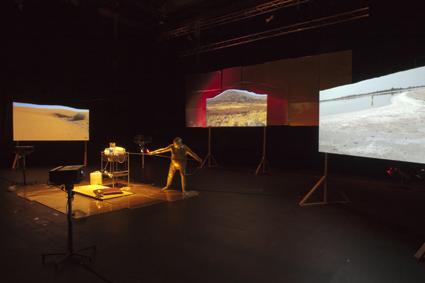

Luke George, Madeleine Krenek, Future Perfect

photo Rohan Young

Luke George, Madeleine Krenek, Future Perfect

“…RHYTHM IS A COMPULSION; IT ENGENDERS AN UNCONQUERABLE DESIRE TO YIELD, TO JOIN IN; NOT ONLY THE STRIDE OF THE FEET BUT ALSO THE SOUL ITSELF GIVES IN TO THE BEAT—PROBABLY ALSO, ONE INFERRED, THE SOULS OF THE GODS!” FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE, THE GAY SCIENCE

Rhythm, according to Nietzsche, can summon the gods, mould the future or elicit emotion. Like art, rhythm fabricates. It creates a temporal pulse or logic. It also compels conformity. We want to fall in with the beat. Rhythm thereby seduces. It exerts the power of inclusion.

Future Perfect begins with a beat, found and repeated by all five performers. They dance as one, producing a jiggling, ‘Brownian’ motion, a suspension of particles, shaken not stirred, as they shift weight from one foot to the other. They are light on their feet as they rebound time and again. A world of repetition is created, a feeling captured and savoured.

Future Perfect trades in feelings. It is not about dance as such. Rather, it shimmers with dreamlike ambition, recalling the ancient world of the Titans, larger than life beings who view humanity from a mythical distance. The dancers are gilded in black and gold costumes, each one a variant upon the other. Phantasmagorical yes, but, like all the Greek gods, these creatures are not that different from mortals. Future Perfect vacillates between these two poles, god-like and human. It gestures towards an atmosphere beyond that which exists, yet visibly depends upon the physical labour of its dancers.

In the midst of the dancing, a series of virtual transformations (by Rhian Hinkley) is projected into the space. The film posits a set of images, each morphing into the next. Identities become blurred as one figure gives way to another. These shifts in imagery in turn have an impact on the watching of the work, changing the perceptible qualities of the dancing towards a more imaginary texture. Who these dancers are becomes less important than their collective enunciation, their patterns, implosions and explosions. They are seen as a whole, a human cluster forming, deforming then reforming. The movement-image (film) pushes the imagery of the movement (dancing) towards a sense of metamorphosis. I let go of my focus and watch the shadows, allowing the bodies to become otherwise.

Ultimately, this imaginary freedom is reined in. The work enters a dystopic phase, a fall from grace. Bodies are less harmonious, in conflict with one another. They fall, not by giving in to gravity, more through a sense of tragedy, as if they would be better off floating. The group is more fractured, individualistic, at odds with itself. Have the immortals gone the way of all humankind? Is death the worst life has to offer?

Future Perfect ends rather abruptly (unless I missed something) which is ironic really, given the work’s title. Perhaps I was lurking in the past while Future Perfect finished. In any case, I have the feeling that narrative development is not where this piece is at. Everything points to the creation of an atmosphere. The space is hung with curvilinear curtains that produce irregular reflections. The shimmering costumes, moving images, the planetary reorientations of the group conjoin to create an ambience. At times I was inside that ambience, suspended in its imaginary ether. At other times, the mood thinned and the magic evaporated.

The strength and power of Future Perfect is found at a distance, in the slow transformations of the group, in the ways in which, together, the group becomes bigger, more than human. That distance in turn enables perception to be freer, able to stray into the neighbourhood of the imaginary. If there is more to be told at the level of human aspiration, then perception needs to find a landing place closer to home. Therein lies the tension, between the god-like and the human, between the pathos of distance and the all too proximate earth.

Future Perfect, choreographer, director Jo Lloyd, performers Luke George, Rebecca Jensen, Madeleine Krenek, Shian Law, Lily Paskas, lighting & set designer Jennifer Hector, music Duane Morrison, costumes Doyle Barrow, projection design Rhian Hinkley, Trades Hall, Melbourne, Sept 14-18

RealTime issue #106 Dec-Jan 2011 pg. 28

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Kriszta Doczy, courtesy Artfilms

KRISZTA DOCZY IS THE FOUNDER OF CONTEMPORARY ARTS MEDIA WHICH PROVIDES, UNDER THE ARTFILMS BANNER, A SUBSTANTIAL CATALOGUE (4,000 FILMS) OF INTERNATIONAL ART ON DVD—DANCE, DESIGN, VISUAL ART, MUSIC, NEW MEDIA, THEATRE AND INDEPENDENT AND AVANT GARDE FILM—WITH A GROWING AND SIGNIFICANT AUSTRALIAN COMPONENT. THESE DVDS ARE INVALUABLE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS OFFERING A SENSE OF ARTWORKS AND PERFORMANCES UNLIKELY TO BE EXPERIENCED FIRST-HAND, OR RARE EXPERIMENTAL FILMS TRANSFERRED EXPERTLY FROM 16MM.

Doczy’s most recent project has been the realisation of Australian Avant Garde, handsomely packed DVD sets of Sydney Underground Movies: Ubu Films, 1965-70 and The Experimental Films of Garry Shead (most made in the 60s and early 70s). You’ll be able to read more about this important act of cultural archiving in RealTime 107.

After years of email contact, Virginia Baxter and I finally met Melbourne-based Kriszta Doczy at the RealTime office in Sydney. Her enthusiasm is infectious, imbued with cheerful determination to bring more innovative Australian art into the international fold of her catalogue, encouraging individuals and companies to make their archival material available, producing and helping them shape the DVDs. We were curious about Doczy’s background and how she came to create Contemporary Arts Media.

At 17, in Communist Hungary, she wanted to be an actor and so joined a mime and dance company: “This was 1969. Everybody was fascinated with Marcel Marceau and the Lecoq style. We trained in contemporary mime but also acrobatics, dance, ballet, you name it, and acting. At the same time Grotowski was in Poland and we took our work to the same festivals. Our company, Domino, disappeared from the face of the Earth—we were banned by the Communist government, we were unemployed, we went underground. But we also toured a lot in Europe. Fifteen years of performing in experimental theatre! We played in cellars and basements, in parks. Then we started to do well so we were on television a lot. The government couldn’t prohibit us after a while. They just tolerated us. But we didn’t get any money. We were ‘starving artists’ but we worked, we had a school and it was buzzing.”

Feeling exhausted and disillusioned by the relentless pressures of theatre-making, Doczy, with her three-year-old first child left art behind her: “At 30 years of age I didn’t have a profession. I didn’t have an education except for high school. I was a single mother in a country where there was no support. So I got jobs in marketing because I spoke English and German. I met my second husband, a blues musician and mathematician, and we left Hungary. By then I was fed up with the entire system. I was 40-years-old when we left. I was pregnant and we spent a year in a refugee camp in Austria, which I could write an entire novel about…We very happily came to Australia. We were accepted on humanitarian grounds. We paid for our tickets and started from zero point absolutely.”

Doczy and family went to live in Perth and then Fremantle. The one thing she laments is never being able to secure a full-time job: “I wanted any sort of job, a normal job. My children were growing up and it was crucial. I wasn’t even thinking about theatre. That was so far away anyway. Conscious Living was a new age magazine, and they employed me in the 1990s using a numerology reading! And I had to sell advertisements. I redesigned the entire magazine. I was fascinated by computers, which came out at the time. We bought a computer and I started to work on it. Ever since I’ve done graphic design. I’m now designing lots of the materials and covers for Artfilms. It’s an endless playground.”

But Doczy was lured back into theatre, running workshops under the aegis of Spare Parts Puppet Theatre and then being offered residencies at Edith Cowan, Murdoch and Curtin Universities. “As bad as it sounds, I had to teach a lot of (traditional) mime. There was nobody teaching things like ‘the invisible wall’ and ‘walking against the wind’.” She decided to take her teaching skills to other cities, to universities in Melbourne, a private class in Sydney, “teaching experimental concepts of movement theatre.” She enjoyed the travel but continued to work in Perth “with performers like George Shevtsov and Stefan Karlsson. I put together a kind of theatre group (Shadow Industries) which did Mrozek’s Tango and an adaptation of Peter Carey’s story “Do You Love Me”—that was probably the best show I did.”

Next came a stint in New York where Doczy’s by then partner “was the Chair at City University of New York which employed me as an adjunct assistant professor teaching experimental theatre. That was a highlight. I was teaching and directing an adaptation of Kafka’s The Trial, a huge production. Big theatre. Big show. Big audience. Beautiful review. 10/10. We were invited to Korea as well: all 13 students, 20 people altogether. At that time I was at the peak of everything. I had a concept about what I wanted to teach—connect (to the body), control and communicate. I started to apply for full-time jobs in America and I was shortlisted a couple of times. And I almost got a job. Almost. But at the end I didn’t. Meanwhile, my children were in Australia and I had limited time. I came back and that was the time I looked into the mirror and I said ‘no more.’ I need a salary.”

So in 2000, Doczy made “three little films on how to teach mime, mask and mask making. My uncle and aunt did some of the work with me. I thought let’s see if I can develop this into a salary. I printed a brochure, secured new films on Commedia and some other teaching films within theatre studies and I sent it out. I had this little distribution company. In about half a year I had an annual salary.”

I wondered how Doczy sourced the films for her very global catalogue. She tells me, “I connected with the artists I knew. I found an international master in Commedia who was starving and I convinced him to make a film. This is my best-selling film ever. Then I met Peter Oyston (founding Dean of Drama at VCA) who became a good friend who helped with the Stanislavski stuff. Because I was teaching drama and also because I was teaching at the academy, I knew what I needed, what I had to show students so they knew what I was talking about—Grotowski, Kantor. With Kantor I found an institute that had the films and I started to correspond with them. At that stage I did nothing about the curriculum in Australia because every state has a different one. So I just thought I’d represent an international curriculum. So that was my approach. Who do I think important to teach? Getting the European material, nobody was doing it at the time. As soon as I started to put out these catalogues, there was a big response—“Oh god, how did you get this?” So that was very welcoming from the beginning. People loved the idea that they could get this material. Nowadays we do a lot of Australian work and I’m just so happy with that.”

Doczy finds most artists she deals with are “very open and very generous. I have their trust and we are so fussy about rights and agreements and all of that. Most have become friends during these years. Sometimes I’m sitting in my pyjamas in Melbourne talking to New York because we’ve set up an appointment with someone like (dance documentarian) Elliot Caplan and he’s in a New York café and he wants to switch on Skype! Obviously the internet is a big thing for us.”

Ironically, as Doczy was building Contemporary Arts Media, she found she still wanted to teach and approached the Head of Music Theatre at WAAPA in 2000. “I’d been teaching for one-and-a-half-years in New York with freelancing actors on the Lower East Side and at the university, [I said] I would really like to teach one unit one evening.” This teaching evolved from 20 students once a week to an entire class of first year acting students and in 2005 she was, at last, offered a full semester teaching job. “I had to say, I can’t. Ten years back I would have died for this job but now I’m running a company. It’s a beautiful company. I can’t wish for more than that. Too late!”

Nowadays, Doczy is based in Melbourne where Simon Rashleigh is Director of Marketing for Contemporary Arts Media, Doczy is Director of Acquisition and Product Development, while Josh Wickham does customer service and graphic designer Effie Shuie works from Taiwan. Doczy says, “We have Eszter in Budapest helping out with product development. And we have Alix Jackson as Production Manager and Editor doing lots of remastering. We have a web developer, filmmakers and others working for us. I’m working for a UK sister company that I’m establishing in London. It’s registered as Artfilms UK. It’s just started. We have a fairly good UK market.”

We return to the subject of the internet: “Our company is developing along with the internet,” says Doczy. “Five years ago there was no way that it would have been possible—multilevel price shopping trolleys for instance. If you go online from the UK, you see every price in pounds. We’re enabling certain discounts for certain countries. If you log in from Ethiopia, you immediately receive 70% discount. It’s a very sophisticated system. Protecting rights for instance: there are films that are available everywhere to us except Germany, France and Japan. Now we’re into an educational streaming system. Universities buy an educational subscription per module, like the Experimental Theatre module or Australian Cinema—different modules for x amount of films and everybody from that campus, the academics or the students, can access them.”

As with much else about the evolution of Contemporary Arts Media, the development of the company’s internet capacity grew from the ground up: “I wouldn’t have been able to establish this company at the time in 2000 if I hadn’t had a teenage son who learned the computer from me as he sat in my lap from age three. Then he was the IT, the website designer, database manager. He set up everything, the network and the system when he was 12 years old. He’s now outgrown us. He’s in London and working as a multimedia designer. My older son, with whom I ran away from theatre when he was three, received a PhD from the London School of Economics and is occasionally an advisor on business matters.”

I’m curious about the markets for Doczy’s catalogue; which is the biggest? “Half is Australia and the other half is between US and UK, mostly US. When we look at who is watching our website, 90% is from the US. The other interesting thing is that although we never really cared about private sales because that is like selling bread and butter—we couldn’t actually exist on it—an increasing number of individuals are buying from us with sales doubling each year. On YouTube we have a channel with one and a half million people watching the film clips. It’s a big playground but as you know from your own experience, it’s a lot of work.”

Kriszta Doczy reflects on her experience of Australia and the creation of Contemporary Media Arts: “My heart is totally Australian but these refugees who are coming from Africa and elsewhere are having a very hard time. We got a lot of help from the government when we came—a lot of help. Big baskets of food. A caseworker. My husband went immediately to a postgraduate course because he was a mathematician. Later I went to university and finished a psychology degree when I was 50-years-old. Australia is a wonderful country but there’s a certain limit. I didn’t get a job. But then I created a job and created work for lots of people—and I got lots of support for that.”

Contemporary Arts Media – Australia; www.artfilms.com.au; Artfilms Limited – United Kingdom, www.artfilms.co.uk

RealTime issue #106 Dec-Jan 2011 pg. 29

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Peer Gynt, 2010, Four Larks Theatre

photo Zoe Spawton & Stephanie Butterworth

Peer Gynt, 2010, Four Larks Theatre

THE FIRST TIME YOU WITNESS A PRODUCTION BY FOUR LARKS THEATRE IS A LITTLE LIKE STUMBLING UPON A BRIGADOON-LIKE VILLAGE; ONE THAT HAS SOMEHOW EXISTED IN ISOLATION FROM THE MAINSTREAM YET HAS DEVELOPED A COMPLETE SET OF TRADITIONS, RITUALS AND AESTHETICS ON ITS OWN.

This ‘lost tribe’ atmosphere is a blessing and a curse—free from the anxiety of influence, the company has created works truly distinct from its peers, which can also suffer from infuriating flaws that could easily be remedied through broader collaboration. That’s why Four Larks’ recently announced residency at Malthouse Theatre is such an exciting prospect. In the past they’ve made striking theatre on the proverbial smell of an oily rag—with the input and resources Malthouse can provide, we may see the cross-fertilisation required for the next stage of this company’s growth.

The trio at the company’s core are Mat Diafos Sweeney, Jesse Rasmussen and Sebastian Peters-Lazaro. They met in California—Sweeney and Peters-Lazaro still hold US passports, while Rasmussen had travelled from Melbourne to study theatre at Berkeley. “We hung out in the Bay Area a little bit after school,” says Sweeney. “I met Jesse and started making some music together, then we fell in love and she sort of whisked me back to Melbourne. Then Bas came over a few months later to do our first show. We really started our theatre project in Melbourne.”

Each of the three takes on specific roles in the creation of their work. Sweeney and Rasmussen collaborate as writers and directors. Sweeney focuses on “the structural, dramaturgical and visual concepts” as well as “sequencing and scoring out the performance.” Rasmussen “is primarily responsible for the language itself, including lyrics both sung and spoken, and also works intimately with the actors on their individual trajectories.” Peters-Lazaro takes charge of all design components and “generating and realising moments of choreography.”

But in the early stages of each work’s development—the “dreaming period,” as Rasmussen puts it—these roles bleed into one another. “We develop all of the elements at the same time,” says Sweeney. “It’s not like we’ve ever had a script where we could show someone what it looks like just on paper. It’s about a visual concept in relation to a musical idea and really specific performers and location. None of the elements stand on their own, so they’re all being developed together.”

This extended period of preparation allows them to arrive at the rehearsal room as a united front, says Rasmussen. If asked, any one of the three could answer a question relating to a piece’s score, its costume concepts, the meaning of a line of text or the intention behind a moment of choreography. It helps that the trio live together and can hash out artistic arguments over the kitchen table rather than the heads of their performers.

This Cerberus-like creative partnership holds its own challenges for newcomers, says Peters-Lazaro: “at the start of a process it is confusing, especially for people who haven’t worked with us before, that there are three people who’re all shaping the work. But then by the end, just because of the scale we work in, we need all six of our arms.”

The scale of a Four Larks work is often its most astonishing aspect. Most feature dozens of actors and musicians; the design itself is consistently on a level of complexity unmatched by some of the country’s best-funded companies. In recent years the trio have begun describing their productions as “junkyard opera,” and the term is entirely apt. These are fully-fledged operas growing from the detritus of contemporary culture.

There’s another term that seems to encapsulate something of what Four Larks are about: folk. Not in the sense of the twee or naïve, though there may be some of that at times too. Rather, in a more thorough sense, the company’s various interests all seem driven by an obsession with communal narratives—folk music, folk tales, the very community they build by inviting so many artists to collaborate on each work. So far most of the company’s works have been adaptations of familiar stories (Orpheus, Peer Gynt, the myth of Undine) but, rather than attempting to locate the definitive version of each, it has been the overlapping of differing accounts that have fed the creative process.

Ben Pfeiffer, Luke Jacka, Undine, Four Larks Theatre

photo Zoe Spawton & Stephanie Butterworth

Ben Pfeiffer, Luke Jacka, Undine, Four Larks Theatre

“The myths that reoccur,” says Peters-Lazaro. “In Undine, the idea that there’s some human creature-ish thing that comes from the water is something that comes up in multiple cultures throughout the world, so it’s interesting for us to look at something like that and explore why that is important. Even if it’s just by starting at a base with which everyone is familiar, we can talk about it in a more in-depth way without having to explain everything.” “We’re interested in talking about the why rather than the what or how,” says Sweeney. “We’re not necessarily interested in creating our own narrative, but in examining others and pulling them apart.”

This reappropriation is also what marks out every aspect of Four Larks’ design. Each set is meticulously constructed from discarded objects: “aesthetically, visually, it’s tied into the same conceptual element,” says Peters-Lazaro. “It’s using objects that have a history. It’s always an act of reappropriation. We’re interested in pretending and playing but no faking. The experience of the performance should be that everyone is hyper-aware that they’re playing at something.”

“It’s sort of an obsession with old things that have a resonance,” says Sweeney. “The set is not being built to look like something, it’s being built from things that are something being used for something else. Which is the same thing we’re trying to achieve with the performers as well, that they’re playing at something.”

In the Tower of the Malthouse next year the company will be tackling its latest object of folklore: The Plague Dances will address the many historical outbreaks of hysterical dancing which have struck communities from the medieval era onwards. “It’s not an adaptation but it’s definitely in the camp of material we’ve worked with before,” says Sweeney. “It’s an event that then gets immediately mythologised and co-opted by different groups, whether it’s the church or politically. It’s potentially a piece about this act of performance.” The residency will offer the company “a place to work in all the areas we’re excited to work, aesthetically and musically and conceptually, working with objects and building this elaborate, fake medieval kingdom.” With what Rasmussen calls their “little plague village up in the Tower” it seems as if the lost tribe is setting up camp in the heart of the capital.

Four Larks Theatre, The Plague Dances, writer Marcel Dorney, Tower Theatre, Malthouse, April 14-29, 2012. For the Malthouse 2012 Season go to www.malthousetheatre.com.au.

RealTime issue #106 Dec-Jan 2011 pg. 30

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Cate Blanchett, Gross und Klein (Big and Small), Sydney Theatre Company

photo Lisa Tomasetti

Cate Blanchett, Gross und Klein (Big and Small), Sydney Theatre Company

TWO SIGNIFICANT WORKS FROM SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY, BLOODLAND, A COLLABORATIVE PERFORMANCE CREATED BY AUSTRALIAN INDIGENOUS ARTISTS, AND BOTHO STRAUSS’ 1978 PLAY GROSS UND KLEIN (BIG AND SMALL) CONFIRMED THE COMPANY’S COMMITMENT TO ADVENTUROUS THEATRE-MAKING. BOTH WORKS CAST THE AUDIENCE IN THE ROLE OF OUTSIDER WHILE SIMULTANEOUSLY DEALING WITH THE OUTSIDER’S PLIGHT.

Neither work provides easy access—Bloodland is delivered largely in the Yolgnu tongue of Eastern Arnhem Land (without subtitles) in a discursive often movement-based narrative, while Gross und Klein elliptically tracks the emotional state of a woman whose life is falling apart in increasingly surreal episodes. Yet both works, once entered, reward us with insight into the outsider’s pain.

gross und klein (big and small)

In the opening scene of Gross und Klein, Cate Blanchett delivers the first volley of a tour de force performance, establishing Lotte as the outsider she is, the expansive dimensions of her personality and the potential for the trouble that will come—she is amiably garrulous (we are her confidantes), curious (she listens to two men talking “like total philosophers,” taken by their “throbbing” voices), betrayed (deserted by husband Paul), alone (with a tour group in Morocco who have turned on each other) and visionary (in an outburst about the fate of the Earth that takes her by surprise and anticipates later delirium).

With great vocal and physical ease, Blanchett sustains a remarkable sense of spontaneity and increasing unpredictability so that when Lotte trips into surreal scenarios, dances crazily or argues with God, we can go with her. We accept Lotte’s desire to learn languages, to think, to help, even though we know that the loss of love will repeatedly thwart any ambitions and that, perhaps, we are witnessing a descent into madness—although the world she encounters is possibly madder. Blanchett’s lucid delivery is underpinned by Botho Strauss’ austere writing, fortunately rendered not too idiomatically into English by Martin Crimp who refers to “the blue sky thing,” “nanotechnology” and their like to give the play a more contemporary feel. Crimp retains the play’s sense of foreignness, apt for Lotte’s condition and Strauss’ critique of a disintegrating society where this woman cannot secure a foothold. Blanchett captures perfectly Lotte’s desire to reach out—to an old friend and to perfect strangers (she talks through a window, advising a woman on how to dress; she takes a drunken Turkish man for a walk to sober him up; she visits her brother’s neurotic family; she takes on an office job)—but also to regress (returning to her and Paul’s apartment; attempting hopeless reconciliation; calling their old telephone number from a phone box in the middle of nowhere—an otherwise eerily naked stage).

What makes this production of Gross und Klein particularly disturbing is how painfully funny it is, giving the play’s consistent strangeness a through-line without ever straining to be comic, underlining the sheer happenstance of Lotte’s journey and allowing her to assume the mantle of a divine-ish fool. Having declared of humanity, “we’re not falling, we’re flying apart,” Lotte discards her dress to reveal a glittering showgirl outfit and confronts God: “Don’t come any closer! … I’m not your cup…I can’t take you on as well!” Bleeding and writhing on the floor, she wonders if he (God or Paul?) “wants to make me small.” We know Lotte is bigger than that. And the remaining scenes (a riotously hilarious office job with Blanchett reminding me of the physical bravery of Gena Rowlands in John Cassavettes’ film Love Streams (1984); an encounter with a chess-playing loner at a bus stop that might have become an unlikely relationship; and an apparently purposeless visit to a doctor’s waiting room) all suggest a return to some kind of stability if not normality alongside Lotte’s own asessment: “There’s nothing wrong with me.”

Benedict Andrews (who took over the production from French director Luc Bondy) has directed contemporary German plays here and in Berlin and is the perfect match for Botho Strauss (he has also directed three plays by Martin Crimp for STC). He has elicited consistently strong performances from his cast and worked inventively with Johannes Schultz’s set—a simply framed rectangle within which rooms can unfold or float apart or a strange apartment block glide into view, a highway appear with the laying down of white lines—a world if not “flying apart,” certainly aptly unstable. Gross und Klein is a must see—a great play, equally demanding and rewarding, and an immaculate production with an astonishing central performance that demands we step back and take a look at our lives through a new frame—to see just how sane or not are we and the society that tolerates us.

bloodland

Bloodland, Sydney Theatre Company

photo Danielle Lyone

Bloodland, Sydney Theatre Company

Bloodland posits its non-indigenous audience as outsiders, witness to Indigenous language, ceremony and social tensions largely foreign to us. We have to work hard to find our way into the performance—much of the dialogue is delivered in Yolgnu, the language of the peoples of East Arnhem Land, especially in the early scenes where we’re heavily reliant on non-verbal cues. Later, Aboriginal English and a greater orientation to movement make meaning more transparent. But that initial sense of being an outsider is important, not that it ever leaves us—we are, as usual in the theatre, pretend voyeurs, but here moreso than usual. However, we are not the only outsiders—the clan society we observe has its own.

Cherish (Ursula Yovich), an eccentric loner who collects or most likely steals mobile phones she doesn’t use, mutters ritualistically over her cache the names of their owners. Billy (Kelton Pell) is city-educated, but denied involvement in ceremonies by clan elder Djurrpun (Banula Marika). Nonetheless Billy’s betrothal to young Gapu (Noeline Marika) stands, but it drives the boy who loves her, Runu (Hunter Page Lochard), into tragic isolation. Individual plights are amplified by tension between clans, by arguments between the women—as they make bread—over the obligations of sharing and exacerbated by the gap between learning ceremony and the appeal of hip hop and MP3 players for the teenagers. Added to which is collective despair over control of Indigenous land rights and language by a distant white government. Billy’s making and distribution of the hallucinogenic kava is another complication—its effects realised as a slow-motion tottering as opposed to the vitality and grace of the boys performing a kangaroo dance.

The set for Bloodland amplifies this prevailing sense of darkness and disconnection: a damaged wire fence spans the stage, cage-like, behind which, dimly discerned at first, is nature—evoked abstractly as grasses and spindly trees amidst which members of a clan stand and ominously watch or a dog (David Page) growls ferociously or a clan elder sings while carefully butchering a kangaroo. Near centre-stage, a power pole, sparking dangerously at its peak, leans perilously over land scarred by mining and a people caught between past and present. By the end, we have come to see both the Indigenous individual and their society as outsiders.

Bloodland is a significant if flawed creation, its theatre-cum-dance hybridity feeling at times unresolved, our sense of the key characters too impressionistic, its multiplicity of important issues spread thin in a short work. The crudely satirical scene of a teacher, Miss White, executing her students for declaring themselves Yolgnu ruptured a sense of Bloodland’s tonal consistency. Otherwise, the oscillation between easy-going naturalism and movement based ceremony worked well, although the protracted funeral at the end, for all its sense of ritual and powerful grieving, seemed disproportionate to what had gone before. But, I write as an outsider, witnessing Indigenous Australians made outsiders in their own land, enacting their plight in their own language and powerfully performing it.

Gross und Klein is programmed for the London 2012 Festival; Bloodland is in the programs of the 2012 Adelaide and Perth Festivals. You can see footage of Bloodland at www.sbs.com.au/news/video/2166576735/Bloodland

–

Gross und Klein (Big and Small), writer Botho Strauss, English text by Martin Crimp, director Benedict Andrews, performers Cate Blanchett, Lynette Curran, Anita Hegh, Belinda McClory, Josh McConville, Robert Menzies, Katrina Milosevoic, Yalin Ozucelik, Richard Piper, Richard Pyros, Sophie Ross, Chris Ryan, Christopher Stollery, Martin Vaughan, set designer Johannes Schultz, costumes Alice Babidge, lighting Nick Schlieper, composer, sound designer Max Lyandvert, Sydney Theatre, Nov 19-Dec 23; Sydney Theatre Company & Adelaide Festival: Bloodland, concept, direction Stephen Page, story Kathy Balangayngu Marika, Wayne Blair, writer Wayne Blair, performers Elaine Crombie, Rarriwuy Hick, Rimi Johnson page, Kathy Balangayngu Marika, Noelene Marika, Banula Marika, David Page, Hunter Page Lochard, Kelton Pell, Tessa Rose, Meyne Wyatt, Ursula Yovich, set Peter England, costumes Jennifer Irwin, lighting Damien Cooper, composer Steve Francis; Wharf 1, STC, Oct 7-Nov 13

RealTime issue #106 Dec-Jan 2011 pg. 32

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

PS122, New York

DURING THE SPRING IN NEW YORK I WORKED IN THE PROGRAMMING OFFICE AT PERFORMANCE SPACE 122 (PS122). IT WAS A SIGNIFICANT AND HISTORICAL TIME FOR THE DOWNTOWN PERFORMANCE INSTITUTION AS IT WAS CELEBRATING ITS 30-YEAR HISTORY AND PREPARING TO CLOSE ITS CURRENT HOME FOR RENOVATIONS TO GO OFF SITE FOR THREE YEARS, FOLLOWING A MAJOR INFRASTRUCTURE GRANT FROM THE CITY OF NEW YORK.

PS122’s venue was once an old primary school in Manhattan’s East village. In the late 70s a community of artists started to inhabit the building and through the next three decades it quickly developed into the hub of the avant-garde downtown arts scene.

To say goodbye to the old building PS122’s artistic director, the Australian Vallejo Gantner, presented The RetroFutureSpective Festival, a two-week farewell party to celebrate the building’s considerable history, the community that shaped it and to introduce the radical shift into a new future for the performance art institution.

The RetroFutureSpective Festival was an exhaustive two week event. It included an All Day Dance Class—informal workshops with influential choreographers—followed by a night-time screening of the Alan Parker movie Fame which was shot on location at PS122 in the 80s. ECHO: 30 Years of PS122 was a three-channel video installation of archival footage by Charles Dennis; Avant-Garde-Arama Wrecking Ball, a two-night showcase of queer performance; while the culmination of the festival was The Old School 122 Benefit, a four-night mini-festival within the festival. The luminaries of the downtown performance scene from past and present were invited to perform back to back in this four-night marathon of short works—artists such as Penny Arcade, John Zorn, The Wooster Group, Eric Bogosian, Sonic Youth front man Thurston Moore, The Elevator Repair Service, all coming to pay their respects to the space that helped form their early careers.

The building was wrapped in nostalgia; the downstairs theatre was converted into a lounge hosted by Lori E Seid, a respected production manager. In one of our encounters she told me she was “the Dyke” in Penny Arcade’s seminal work, Bitch, Dyke, Fag Hag, Whore, which premiered at PS122 in 1990 (and toured to Australia). During the festival, artists such as Amanda Palmer popped in to sing some pre-show tunes at Lori’s Lounge.

A highlight of the festival was Charles Dennis’ ECHO. The artist edited 30 years of PS122 archival footage into a one hour 20-minute, three-channel video installation. Sitting through over an hour of performance footage from three decades of live works might sound like a serious chore for some, particularly when live works rarely translate well into film. However, Dennis’ ECHO is a remarkable installation that transforms the potential of the performance archive, creating a stand-alone work that was mesmerising to experience. This was partly due to the overwhelming collection of artists represented, but mostly to Dennis’ virtuosic editing and composition with each of the large screens simultaneously showing different footage. On one screen, an excerpt of experimental musician John Zorn improvising on violin becomes a soundscape for Spalding Gray’s monologue on the centre screen, while on the third, choreographer Sarah Michelson’s dancers appear to be moving to the erratic soundscapes created by Zorn and Gray. In another moment, retro footage of The Blue Man Group emerges, while images of Gray dissolve into the raps and melodic raves of Reggie Watts. ECHO holds these artists and their histories in the same time and space, in a wonderful evocation of the vision underpinning Gantner’s festival.

The art collective Praxis (Delia and Brainard Carey) presented a work from their conceptual museum MONA, The Museum of Non-visible Art. Praxis states that the museum “reminds us that we live in two worlds: the physical world of sight and the non-visible world of thought composed entirely of ideas; the Non-Visible Museum redefines the concept of what is real.” Each work sold from the museum has this disclaimer, “You are not buying a visible piece of art; you are buying the title and description card for the imagined artwork.”

At MONA artists are invited to collaborate and create conceptual works that exist in the imagination alone. Most famously NYC’s uber-man James Franco’s MONA contribution was recently purchased for $10,000 on the funding platform Kickstarter. For this festival, Praxis created a ghost tour, presented in a disused back room. Five audience members at a time would be guided through the imagined museum while Praxis described the imagined and real ghosts of PS122—such as Ethyl Eichelberger, Andy Warhol, Jack Smith, Spalding Gray and Charles Ludlum. Audience members could also purchase the works or ‘ghosts.’ The concept of MONA at this point is still developing: during the Ghost Tours Praxis struggled to bring their concept into the realm of live performance, falling short of engaging the audience in their imagined histories. However Praxis are only at the beginning of developing the infinite concept of MONA and I look forward to the future construction of their Museum of Non-visible Art.

Pullman WA, Young Jean Lee Company

photo Dona Ann McAdams

Pullman WA, Young Jean Lee Company

Young Jean Lee Theatre Company is a stand out presence on the NYC performance scene. The artistic director of the company, Korean-born Young Jean Lee, was recently named by American Theatre magazine as one of the 25 artists who will shape American theatre over the next 25 years. As part of Retro, Lee presented an excerpt from her work Pullman, WA that premiered at PS122 in 2005. The title of the work refers to the town where Lee grew up, but instead of watching a linear presentation of personal anecdotes we experience a non-linear series of provocations about the confusions of day-to-day living. On a bare stage a man stands facing the audience, the house lights are up. He tells us that “he knows how to live” and proceeds with a subversive and provocative monologue that challenges our sense of self. The starkness and explicitly truthful nature of the text and presentation was completely original to me, and Pullman, WA provided me with one of those rare moments in the theatre where I felt somehow changed.

The final night became a four-hour epic, the house packed beyond capacity. The Wooster Group provided the last official work on the program, presenting the infamous Hula performed by a near naked Kate Valk. But the real finale was reserved for Phillip Glass who played a rendition of his work Closing.

The PS122 building is a space that many artists call home (I could not help but reflect on the old Performance Space venue on Cleveland Street in Sydney).The RetroFutureSpective Festival was overwhelming, heavily weighted with 20th century nostalgia that focused on honoring the incredible community and works that developed throughout the heyday of the formation of New York City’s avant garde.

As PS122 vacates, Gantner will be maintaining a balancing act over the next three to five years creating a program that exists across sites and venues throughout the city, with a vision of creating an engaged online social environment for PS122. The new development parallels the urban and social transformation of Manhattan, with the renovations being a positive and necessary step for the much loved but well-worn performance establishment. The next three years will be a challenge, an opportunity for Gantner and his strong team to create the future history of performance across New York City.

PS122, The RetroFutureSpective Festival, New York, June 11-25

See an excerpt of Charles Dennis 79 minute video work revisiting 30 years of archival performance footage from PS122

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=daQAcuaOIFI

RealTime issue #106 Dec-Jan 2011 pg. 34

© Karen Therese; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Katia Molino, Mohammed Ahmad, I’m Your Man, Roslyn Oades, Belvoir

photo Bill Reda, courtesy Sydney Festival

Katia Molino, Mohammed Ahmad, I’m Your Man, Roslyn Oades, Belvoir

The major theatre companies have launched their programs for 2012. Year by year these become more and more fascinating indicators of the expanding parameters of theatricality in mainstage programs (dance, contemporary performance, puppetry, opera, physical theatre, Indigenous performance) and the collaborative interplay between companies, not merely cost sharing but exploratory, nor a closed circuit as large companies take on board the likes of Hayloft, version 1.0, My Darling Patricia, Urban Theatre Projects, Circa, Ilbijerri, Four Larks Theatre, The Black Lung Theatre, Post and others. While plays are still central to theatre company programs they have become part of the broader ambit of performance involving an expanded range of authorship. The following overview of 2012 programs will give you some idea of the extended range of performance and the interconnectedness that has come with a new generation of artistic directors.

belvoir

With the Sydney Festival Belvoir premieres Urban Theatre Projects’ Buried City, written by Raimondo Cortese. It’s about immigration, development and who controls the future and made in consultation with the Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU) and their Retired Members Association, African Women Australia Inc and Gadigal Information Service Aboriginal Corporation. Also for the festival, Belvoir with CarriageWorks presents a version of Seneca’s Thyestes (a deposed king who unknowingly eats his sons) originally commissioned from Melbourne’s The Hayloft Project by Malthouse Theatre and directed by Belvoir’s Simon Stone. Another festival work is I’m Your Man, created and directed by Roslyn Oades (Stories of Love and Hate) which recreates verbatim the journey of an ambitious young Bankstown boxer on his way to a world title fight.

Also in the 2012 program there’s a version of Euripides’ Medea told, a la Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, from the point of view of the minor characters. Director Anne-Louise Sarks is the artistic director of Hayloft; co-writer is Kate Mulvany. Belvoir, version 1.0 and Ilbijerri Theatre Company unite for Beautiful One Day, created by Paul Dwyer, Eamon Flack, Rachael Maza and David Williams. This “theatrical documentary” focuses on troubled Palm Island, exploring similar territory to Chloe Hooper’s book and Tony Krawitz’s documentary, both titled The Tall Man, but with a very different approach. Leah Purcell will direct Don’t Take Your Love to Town, created with Belvoir’s Eamon Flack and based on the late Ruby Langford Ginibi’s book of the same name.

Simon Stone with actress Emily Barclay tackles a true rarity, Eugene O’Neill’s Strange Interlude; actor Matthew Whittet’s play Old Man, about fathers and sons and Newtown, is premiered; Colin Friels and Genevieve Lemon star in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, directed by Stone. Belvoir’s Artistic Director Ralph Myers makes his directorial debut with Noel Coward’s Private Lives—that most sleek of 20th century comedies—with Eloise Mignon and Toby Schmitz in the lead roles. As John Lahr wrote in Coward the Playwright (1982): “Minimal as an art deco curve, Private Lives’ form matched its content; a plotless play for purposeless people”—and no less enjoyable for it.

With three actors and three dancers, choreographer and director Lucy Guerin has been commissioned by Belvoir to create Conversation Piece with Alison Bell, Megan Holloway, Alisdair Macindoe, Rennie McDougall, Harriet Ritchie and Matthew Whittet: “A group of actors and dancers meet on stage and begin the show with a short conversation about…Well, we don’t know yet. Each night it will be a different conversation” and this will “form the basis” of the performance. Actress Rita Kalnejais has written Babyteeth to be directed by Eamon Flack; another actor turned writer, Steve Rodgers, will have his play, Food, about a pair of feuding sisters, directed by Force Majeure’s Kate Champion. Benedict Andrews will direct his own play, Every Breath, about a threatened family who hire a security guard they are each attracted to (a hint of Pasolini’s Teorama?).

sydney theatre company

For the Sydney and Adelaide Festivals, STC presents Force Majeure’s dance theatre creation Never Did Me Any Harm, directed by Kate Champion, inspired by, although not based on, Christos Tsolkias’ The Slap and featuring a strong cast of actors and dancers that includes Heather Mitchell, Marta Dusseldorp, Kristina Chan and Kirstie McCracken.

Griffin’s Sam Strong will direct Hugo Weaving and Pamela Rabe in Christopher Hampton’s fine version of Choderlos de Laclos’ 1782 novel Les Liaisons Dangereuses, a complex tale of sexual intrigue. Co-artistic director Andrew Upton will direct Dylan Thomas’ intensely poetic, nostalgic and bittersweet Under Milk Wood with a cast that includes Jack Thompson and Sandy Gore. Upton and Belvoir’s Simon Stone have boldly adapted Ingmar Bergman’s journey into despair, Face to Face, for the stage with Stone directing the always impressive Kerry Fox, Wendy Hughes and John Gaden.

The Splinter, by Hilary Bell and directed by Sarah Goodes is described as “an emotional thriller.” An abducted child is returned to her parents (Erik Thomson and Helen Thomson), but is she theirs? The intriguing thing about The Splinter is that the child will be represented by a puppet. Alice Osborne is the puppetry and movement director. Bell is apparently “inspired by the Henry James novel The Turn of the Screw, the Hans Christian Andersen tale The Snow Queen and real life stories of abducted children.”

Melbourne’s Daniel Schlusser will direct Thomas Bernhard’s The Histrionic featuring Bille Brown (see Malthouse below) and Peter Evans will take on George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion with Kym Gyngell and Andrea Demetriades.

Perth’s Black Swan and STC will stage novelist-turned-playwright Tim Winton’s second play, Signs of Life: a lone woman on a farm, “contemplating her solitude”, is visited by strangers—an Aboriginal man and woman. Kate Cherry directs. Also in the 2012 STC program is Jonathan Biggins’ Australia Day, a timely satire given the increasing cultural complexity of our nation.

malthouse

Belvoir’s impressive adaptation by Simon Stone and Chris Ryan of Ibsen’s The Wild Duck (RT102) kicks off Malthouse’s 2012 program. In a co-production with Sydney Theatre Company, Daniel Schlusser will direct Tom Wright’s translation of Thomas Bernhard’s The Histrionic (Der Theatermacher), described as a “rampage of satire on art, celebrity and the cult of personality” featuring Bille Brown as the egotist under scrutiny. Artistic director Marion Potts will take on Lorca’s Blood Wedding with music by Tim Rogers. With Perth Theatre Company, Malthouse will present On the Misconception of Oedipus, forensic theatre devised by Zoe Atkinson, Matthew Lutton (also directing) and Tom Wright that imagines the back story of the tragedy of Oedipus.

Resident company, Four LarksTheatre (see article), will create The Plague Dances, about massive, manic outbreaks of dancing across the centuries. From Brisbane, via the world, comes the physical theatre company Circa with their stripped back, highly intelligent circus. It’s good to see Indigenous choreographer Vicki Van Hout’s Briwyant in the program; as I wrote in RT103: “Vicki Van Hout’s choreography is some of the most idiosyncratic and inventive choreography seen in Australian dance for a long time and her team of dextrous dancers execute it with high precision, unbelievable energy, humour and attitude.”

Malthouse’s Opera XS features Chamber Made Opera partnering Rawcus in an improvisation based on the music of Henry Purcell; Short Black Opera Company’s Redfern; and Victoria Opera’s Victoria Shorts. Paul Capsis performs his autobiographical Angela’s Kitchen (see Griffin Theatre Company below); Jane Montgomery Griffiths, directed by Marion Potts performs the late Dorothy Porter’s verse novel Wild Surmise; Matthew Lutton directs Declan Greene’s apocalyptic take on LA culture; and Rosemary Myers directs Julianne O’Brien’s contemporary update of Pinocchio “as witty, gothic, rocking music theatre,” in a co-production with Windmill and the State Theatre Company of South Australia.

griffin theatre company

For the Sydney Festival, Griffin begins its year with Gordon Graham’s 1991 deeply disturbing classic about family, masculinity and murder, The Boys (later adapted by Stephen Sewell for Rowan Woods’ 1998 film), celebrating the play’s successful premiere at The Stables Theatre 21 years ago. Griffin’s artistic director Sam Strong will direct The Boys which will also play in the 2012 Merrigong Theatre season in Wollongong. The Story of Mary MacLane by Herself is adapted by Bojana Novakovic, from a century-old confessional work from a 19-year-old that scandalised American readers and sold copiously: “I should like a new man to come. A perfect villain to come and fascinate me. And I should ask him quite humbly to lead me to my ruin.” Novakovic and director Tanya Goldberg (Ride On Theatre) will stage MacLane’s provocative writing as a “monologue for two” with music by Tim Rogers. The production is presented in association with Malthouse Theatre, Merrigong Theatre Company and Performing Lines.

Paul Capsis’ Angela’s Kitchen, directed by Julian Meyrick and with Hilary Bell as associate writer, is singer Capsis’ autobiographical celebration of his mother, taking him back to Malta which she left in 1948 with five children to live in Sydney’s Surry Hills. This return season of a hit for Griffin in 2010 is a prelude to a tour to Canberra, Albury, Wollongong, Parramatta, Melbourne and Brisbane.

Playwright Rick Viede enjoyed success at Griffin with his first play, Whore, which won the 2008 Griffin Award and the 2010 Queensland Premier’s Literary Award. His new play, a co-production with Brisbane’s La Boite, is A Hoax, “a vicious satire on the politics of identity, modern celebrity and the peddling of abuse culture.” Ian Meadows’ Between Two Waves is one of a small number of plays that addresses environmental issues, focused here on prediction and responsibility: how can we live and procreate when it’s likely that coming generations will suffer from our neglect. Between Two Waves is the first play to be produced out of the Griffin Studio.

queensland theatre company

Wesley Enoch’s first season as artistic director of the QTC includes Belvoir’s acclaimed Neil Armfield production of The Summer of the Seventeenth Doll; Jennifer Flowers directing Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet; Brisbane playwright Matthew Ryan’s Kelly, an account of Ned in his cell visited by brother Dan who is unexpectedly still alive; and the Sydney Theatre Company’s Bloodland (see article).

Enoch is directing four productions: Joanna Murray-Smith’s Bombshells, starring Christen O’Leary; Dario Fo’s Elizabeth, Almost by Chance a Woman, with Carol Burns; Sydney writer Alana Valentine’s Head Full of Love (Darwin Festival commission 2010) about the encounter between a Sydney runaway (Collette Mann) and an Alice Springs local, Napuljari (Roxanne McDonald), in the context of the Annual Alice Springs Beanie Festival; and David Williamson’s Managing Carmen about a cross-dressing footballer at the peak of his career who risks being outed.

zoe coombes marr wins award

Congratulations to writer-performer Zoe Coombs Marr (one of the talented trio comprising Post) who has won the 2011 Philip Parsons Young Playwrights’ Award for her one-woman show, And That Was the Summer That Changed My Life which premiered at Next Wave Festival in 2010. The Award is given annually to a NSW-based writer under the age of 35 for an outstanding work which has been performed. The award comes in the form of a writer’s commission supported by Belvoir to develop a new work.

RealTime issue #106 Dec-Jan 2011 pg. 35

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Alain Platel

photo Chris Van der Burght

Alain Platel

FOR SOMEONE WHO IS RECOGNISED AS ONE OF THE GREAT EUROPEAN THEATRE PROVOCATEURS OF THE LAST 20 YEARS, HAILED FOR PRODUCTIONS THAT SHOW EVERYDAY LIFE IN ALL ITS IMPERFECTION AND FRAGILITY, BELGIAN CHOREOGRAPHER ALAIN PLATEL APPEARS SURPRISINGLY MILD-MANNERED AND SERENE IN CONVERSATION. SOFT-SPOKEN YET ARMED WITH THE MISCHIEVOUS SMILE OF A TEENAGER, HE EXUDES THE AIR OF A MAN WHO, AT 55, HAS NEVER STOPPED ASKING QUESTIONS, NOT LEAST ABOUT HIS ROLE IN THE SCHEME OF THINGS.

In Australia to present his Les Ballets C de la B work, Out of Context—for Pina at Sydney Opera House’s Spring Dance and Brisbane Festival, Platel is pleased to discover that at the former the piece is accompanied by a series of films and talks celebrating the life and work of legendary choreographer Pina Bausch—a fitting context for his work. The idea for Out of Context came to Platel when returning to Belgium after a commemorative service for Bausch in Wuppertal. He wanted to give her a “present.” Platel says: “Ever since I met Pina at the end of the 90s, she no longer was only this famous choreographer but also became an extremely important human being in my life, somebody I was very inspired by.” Citing her work Café Müller (1978) as one of the dance pieces that changed his life, Platel credits Bausch with influencing the way he watches theatre: “I think what she did for me was to intensify my looking at things…to enjoy looking at people.”

It is interesting to note that like Bausch, Platel did not set out to explore an existing performance language but developed a style of his own by pursuing a line of inquiry that originated in asking questions he was personally interested in. Originally, he trained as a remedial educationalist working with children with motor and multiple disabilities. Founding the Ghent-based theatre collective les ballets C de la B in 1984, Platel describes himself as an autodidact director and a reluctant one at that. It took him five years, he admits, before changing jobs and starting to call himself a professional theatre maker: “In the first few years, we didn’t have the ambition to become big stars or tour the world. We were just having fun. Our first performances, you know, we performed only four or five times in front of about 400 people. And that was a lot for us at the time.”

However, Platel’s exuberant productions, with their eclectic casts of professional and non-professional performers from culturally and socially diverse backgrounds, wildly mixing high and lowbrow cultural references, soon captured the imagination of audiences throughout Belgium. The international breakthrough followed in the mid-90s and resulted in extensive, worldwide touring of shows such as La Tristeza Complice (1995) and Iets Op Bach (1998). Platel insists that the driving force behind those large-scale, multi-cast works was his interest in finding out how to communicate politically and philosophically complex themes on stage. This motivation has sometimes been misunderstood, much to Platel’s disappointment: “It makes me sad when I get asked, ‘do you really want to shock people?’ Because I don’t think I have ever had any intention to shock or provoke. To confront audiences with difficult images to look at, yes, but when I show images that are difficult to cope with it’s because I don’t know how to cope with them myself. And I want to share that. I think the theatre is the place where you can do this. Much more than in any other place.”

Out of Context-For Pina, Les Ballets C de la B

photo Chris Van der Burght

Out of Context-For Pina, Les Ballets C de la B

After several years of international success, Platel found the pressure to live up to the reputation and hype surrounding Les Ballets C de la B increasingly difficult. His announcement in 1999 that he would stop making work sent shockwaves through the European theatre scene. He reflects, “I must say I was surprised that people took it so dramatically seriously.” Laughing, he adds, “I shouldn’t have told anybody. But I was really thinking at the time, can I do something else besides making theatre? Should I continue to do this for the rest of my life? I just couldn’t cope any longer with the pressure that was around me in terms of making each year a new success.’’

In the end, his break from theatre-making only lasted a little more than two years before returning to the fold. For Platel, however, it was a significant period, from which he emerged with new-found clarity. “It helped me redefine my position and reflect on how to continue. I now cope better with the whole ‘business.’ I think I take it a little bit less seriously. The pressure is still there but in another way. I am not taken by it. I don’t feel the need to make new work all the time any more. That is a nice thing to realise.” His time away from the theatre also spawned a new approach to choosing the next project, Platel explains: “Now when I decide to do things, it’s a gut feeling, like I have to do it. I want to make it a life experience, not just something along the lines of ‘let’s do a project together’.”

So, with Les Ballets C de la B celebrating its 25th anniversary this year, how has Platel’s view of the role of theatre in society changed over the years? He concedes, “Maybe there was a moment once where I thought we were going to conquer the world and make a difference but I very quickly realised that this was too big a mission.” He laughs. “I read in the paper one day that only 1% of the Belgian population goes to see theatre. So I think it’s pretty difficult to change the world by making performances.” Fair enough. But still, when talking to Platel one can’t shake the feeling he hasn’t given up on the transformative power of theatre altogether: “I have feedback from many people who have witnessed our performances and you feel that a performance can continue to live in someone’s life for a very long time. That is quite surprising. And sometimes, so people tell me, it has an effect on how they live their lives. That is really something.”

Platel admits to often being touched by audience reactions and drawing inspiration from them: “We showed Out of Context in Taipei this year and we performed in this huge theatre, 1500 seats. On the day of the first performance I was walking around the city and thinking, who on earth in this city would think about coming to the theatre tonight to see a performance by Alain Platel. Who the hell is Alain Platel? There are so many things in this city that one can do in the evening. But then the theatre was completely full, on both nights. And not only that but the people really liked the show and were very expressive about it. I had never been there in my life. And this is something that makes me very emotional.” Considering that Alain Platel is so often associated with shocking audiences, his next remark is not without irony: “Thinking back to how we started out and how I didn’t know anything about making theatre, a story like this is really shocking to me. Absolutely shocking.”

Les Ballets C de la B’s Out of Context—for Pina appeared in Spring Dance 2011, Sydney Opera House where he also spoke and conducted a masterclass. See reviews in RT105 and RT98.

RealTime issue #106 Dec-Jan 2011 pg. 26

© Martin del Amo; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

EIGHTEEN SINGERS SIT ON THEIR KNEES IN FOUR CIRCLES, HEADS TOUCHING THE GROUND. THE GROUPS ARE COLOUR-CODED BLUE, RED, YELLOW AND GREEN, COMPLETE WITH TOUCHES OF FACE PAINT. AT THE BACK OF THE STAGE A MARIMBA PLAYER DRESSED IN BLACK BEGINS AN ARPEGGIATED CHORD PROGRESSION. A VIBRAPHONE PLAYER JOINS IN WITH A LILTING MELODY. THE SINGERS BEGIN A SIGHING HARMONY, MUFFLED BY THE FLOOR.

As the vocal intrusion grows louder the singers lift their heads, increasing the clarity of the sparkling, close chords. The song fills the room as the choristers break away from their groupings. Words are heard: “Now we are alone when we are together.”