Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

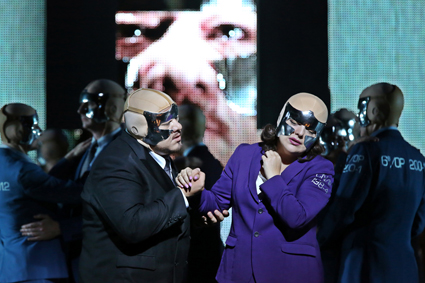

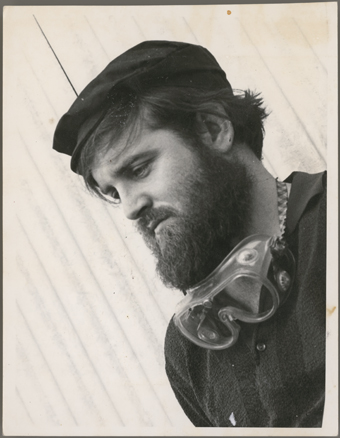

Ash Flanders, Little Mercy

photo Mark Rogers

Ash Flanders, Little Mercy

IN HER ESSENTIAL STUDY OF THE SEXUAL POLITICS OF HOLLYWOOD HORROR, MEN, WOMEN AND CHAINSAWS (1992), THEORIST CAROL J CLOVER ARGUES THAT THE ‘EVIL CHILD’ SUBGENRE—THINK THE EXORCIST, THE OMEN, ROSEMARY’S BABY—IS DRIVEN BY A KIND OF DIALECTIC OF GENDER.

On one side we have the monstrous feminine, hysterical and uncontainable, and on the other a masculinity whose coldness and rigidity is just as problematic. Resolution can only occur when some synthesis of the two is achieved—the patriarch who learns to ‘open up’ and find in himself two sexes symbolically merged into one.

It’s a complex thesis that clearly lends itself to Little Mercy by Melbourne’s Sisters Grimm, soon to open at Sydney Theatre Company’s Wharf 2. The horror-comedy queers the evil child narrative in all directions—here the diabolical eight-year-old is played by a woman in her 70s, her terrified mother by a man, and the genre’s own tropes are stretched to breaking point.

But Clover overlooks an important pleasure that distinguishes the figure of the evil child in horror cinema: “it’s one of those rare occasions where the audience actually wants the bad thing to win,” says Ash Flanders, one half of the Sisters. “Isn’t it just like the id? Wouldn’t we all be killing people for their shoes if there wasn’t a law against it? In a perfect world where you could do what you wanted, I don’t know how happy that world would be. Maybe it would be really sick.”

“Children are pure id,” says his collaborator Declan Greene. “They really do represent this pre-socialised hunger. Watching evil child films is just watching a version of that which is untameable. There’s something perverse and wonderful about that.”

Little Mercy takes those sublimated desires and amplifies them—both horror and comedy are modes of excess, which allows the production to stay true to its generic referents while also seeing how far they can be pushed.

“One of the biggest tropes of the genre is that only the mother sees what’s going wrong and no one believes her,” says Flanders. “So this idea that this child is clearly an older woman but no one believes that there could ever be anything wrong with her, it’s that classic thing where you put a grenade in like this and it changes everything. At the same time you’ve got two men playing women. It’s clear that this is a world that’s not trying to make logical sense. It’s playing with form, exploiting these stories.”

The pair talk about the ‘cracks’ that such devices reveal in their own narrative, and how the company’s goal has long been one of finding such points of rupture within generic moulds. But the source of such a method is itself now a problem.

“A very important thing that has defined our practice has been poverty,” says Greene. “What we do is try to write narratives that we subject to pressure, and that pressure comes from the inadequate resources that we’ve managed to marshall to execute a much grander vision. The problem with trying to do a theatre show with a company like STC is that all of a sudden your resources are a lot better. You can’t just pretend you don’t have money when you’re at the STC.”

Sisters Grimm have long been Melbourne theatre’s own evil children. “We had our early shows where we’d make ourselves vomit on stage or perform sex acts, and you have to do it when you’re a bit younger,” says Greene, “when you have to ‘find your voice’ by spewing on each other.” But, says Flanders, “Doing a show in a car park with a bunch of cool theatre friends also feels safe in a way, too. It has a touch of preaching to the choir.”

In addition to Little Mercy at STC, a new Sisters work will premiere at the Melbourne Theatre Company this year. But the pair aren’t interested in playing the outrageous kids trying to shock the big theatre crowds with their edgy material. “It’s important that we’re breaking our own rules, not theirs, says Greene, “that we’re creating a world with very clear and distinct rules and then upending those.”

“It is about breaking your own rules, rather than trying to get some rise out of the audience,” says Flanders. “That almost feels falser to me. That feels too controlled. I’d rather set up a world and have that crumble in front of you.”

Sydney Theatre Company, Little Mercy by Sisters Grimm, creators Ash Flanders, Declan Greene, Wharf 2, March 7-24, www.sydneytheatre.com.au

RealTime issue #113 Feb-March 2013 pg. 32

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

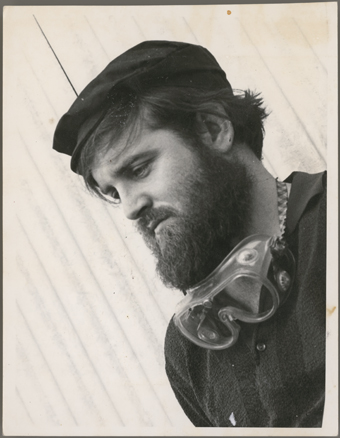

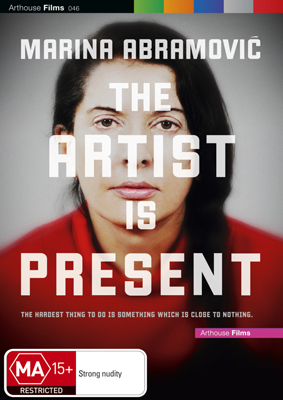

Relation in Time, Ulay/Abramovic, 1977; Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present, images courtesy of Madman, © 2012 Show of Force LLC and Mudpuppy Films Inc. All Rights Reserved

I FIRST ENCOUNTERED THE WORK OF MARINA ABRAMOVIC IN THE EARLY 1980S WHEN I BOUGHT A COPY OF RELATION WORK AND DETOUR, AN ACCOUNT OF ABRAMOVIC’S WORK WITH HER PERFORMANCE AND THEN LIFE PARTNER ULAY. AT THE TIME, KEITH GALLASCH AND I WERE BEGINNING TO CREATE A SERIES OF PERFORMANCES FOR OPEN CITY BASED ON OUR OWN RELATIONSHIP THOUGH WE HAD NO AMBITIONS TO MATCH THE INTENSITY OF APPROACH OF THESE TWO.

relation in time (1977)

We are sitting back to back, tied together by our hair without any movement. (16 hours) Then the audience come in. (17 hours)

In the documentary The Artist is Present by Matthew Akers and Jeff Dupré we accompany Abramovic in the preparations for her retrospective at MoMA in the winter of 2010. She separated from Ulay in 1988 and it appears they haven’t met for some time. The film moves between arrangements for the exhibition and Abramovic’s live performance, which will be part of it. Each day of the show’s three-month duration, Abramovic, seated on a wooden chair, will face individual members of the public. “The hardest thing to do is something close to nothing. It demands all of you,” she says.

Documentation of performance art works is necessarily problematic—how to represent the ephemeral, recast the uniquely personal, preserve the live moment?

imponderabilia (1977)

We are standing naked in the main entrance of the Museum, facing each other. The public entering the Museum have to pass sideways through the small space. Each person passing has to choose which one of us to face. (90 minutes).

We see Marina nervously awaiting the arrival of the 30 young artists who have been chosen to ‘re-perform’ some of the seminal Abramovic/Ulay works. They will be at Marina’s home in Hudson Valley for three days—fasting, living in silence, no phones—all to help them empty themselves, to slow down. They have three months to perform and will have to create their own ‘charismatic space’—to be ‘present.’

Later, watching these young bodies in the gallery standing in for the weathered frames of the artists who had conceived these actions, lived the difficult lives that they reflected, it’s hard to see them as anything other than representations in another time. Naked bodies in the museum, however, have a way of attracting attention—though not necessarily the sort you might seek. Fox News’ “America Live” alerts its audience to the audacious Abramovic as “some Yugoslavian-born provocateur.”

For an artist who creates such intense works, Abramovic projects a cool bemusement in her everyday dealings with people. She cheekily admonishes the catalogue essayist with: “But you haven’t asked me ‘Why is this art?’” She’s justifiably annoyed at her status, “still alternative” after 40 years of work. “It takes such a long time to be taken seriously!” Then again, a retrospective at MoMA is not to be sneezed at and in Givenchy’s Spring campaign last year was that Marina’s visage up there next to Kate Moss?

art and life with ulay

Intercut with preparations for the retrospective and for her performance are filmed sequences and still photographs of Abramovic’s solo works and those she performed with Ulay.

These, together with the reunion with Ulay for the show, provide some of the film’s most powerful and poignant moments. When he’s told what she’s planning for her live performance, Ulay says “Wow! I have nothing more to say. Respect.” He recalls Marina’s stamina. In one incarnation of their work Nightsea Crossing (1981) they sat inactive, fasting and silent. He exited after 16 days when he’d lost 24lbs in weight and was near collapse. Marina remained at the table.

We gain some insight into the source of this strength in Abramovic’s recall of a childhood in which her parents, national heroes from Tito’s time, trained her to be a little soldier. The only love in her life came from her grandmother who also provided spiritual guidance. She declares, “The artist must be a warrior, a shaman, must conquer the self and its weaknesses.”

Ulay, having swapped the rigours of performance for academe says, “I look like a worker but I do much less work than Marina.” Their famous walk (The Lovers, 1988) from opposite ends of the Great Wall of China marked the end of the relationship. “We were burning up,” says Ulay. “The better the performances the worse the relationship became.”

After the split, Marina headed in a new direction, which Ulay defines as more “theatrical and formalist.” After all those years of deprivation, she developed a taste for high fashion and fame, creating a work in which she said goodbye to extremes, ending with “Bye Bye, Ulay.”

the performance

Marina Abramovic at MoMA, 2010, Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present, images courtesy of Madman, © 2012 Show of Force LLC and Mudpuppy Films Inc. All Rights Reserved

Back in the present, preparations for the performance urgently proceed. There’s a brief flirtation with the idea of collaborating with an illusionist who munches a wine glass as part of his pitch (rejected), and scenes of an ailing Marina tucked up in a bed of red sheets calling on the healing properties of blood oranges.

And finally we witness the performance itself as one at a time, thousands of people queue, then enter the charmed space to sit before The Artist. Some return Abramovic’s unaffected gaze while others appear desperate to convey something deeper. Many smile, some weep. “So many people have so much pain,” says Marina. Those who get short shrift are the ones who try to turn the moment into their own artwork—one tries to demonstrate her ‘vulnerability’ by removing her clothes. Another reveals a hidden mirror behind an elaborate mask. “I’m the mirror of their own self,” says Marina.

The camera is fascinated with faces including Abramovic’s, which occasionally admits a smile and some tears (for Ulay). The waiting throng watches silently from the perimeter. The guards are on red alert for unheralded interventions. Museum announcements occasionally pierce the silence. The encounter appears meaningful to the participants—more mysterious for the film viewer. Sometimes it takes on the appearance of religious ritual. Abramovic appears nun-like in one of three heavy woollen dresses (one red, one white, one blue). At other times, it feels just a bit indulgent, as if the provocateur, tired of waiting, has designed her own form of devotion. I guess, as they say, you had to be there.

At the end of each session, however, the ‘work’ of this art is powerfully manifest in the toll it takes on the body of the performer. The pain of an immobilised body must be massaged, bathed and exercised away each day to prepare for the next. Abramovic is 63 when the film is made and finally admits, “There’s a limit, even for me.” But when it’s suggested that she cut short the performance, she will not hear of it. She may be marking the 736 hours off on the wall but the show must go on.

As the film and the retrospective draw to a close there’s a lot of summing up, a lot of it about time and how we are caught in it and how Marina Abramovic aims to slow everything down, to bring the performer and the audience into the same state of consciousness of the here and now.

In 106 minutes Akers and Dupré expose for the viewer something of the emotional, physical and intellectual demands inherent in mounting an exhibition and performance that deal in the power of the present. In the process they also offer insight into the life’s work of a remarkable artist.

Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present (2012), co-directors Matthew Akers, Jeff Dupré, cinematography Matthew Akers, editors Jim Hession, E. Donna Shepherd, original music Nathan Halpern. Distributed in Australia by Madman Entertainment.

RealTime issue #113 Feb-March 2013 pg. 18

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

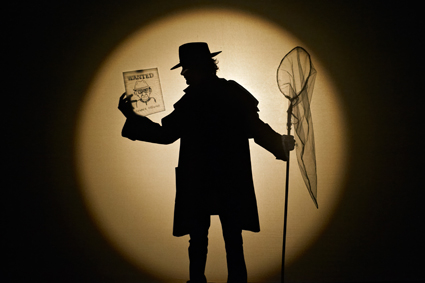

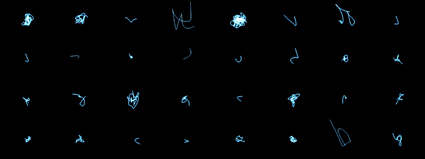

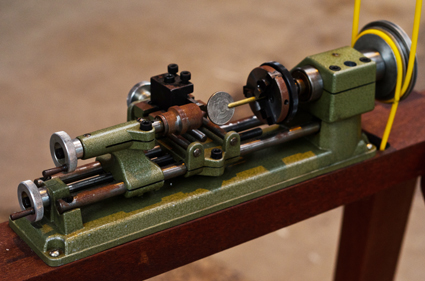

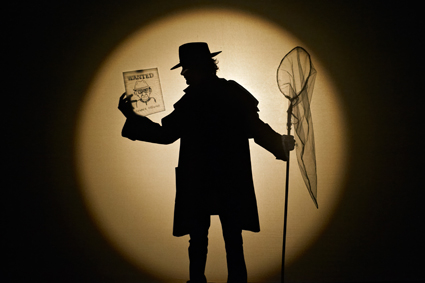

Peter Burr, Special Effect, courtesy the artist

NEW YORK-BASED ARTIST PETER BURR IS FAMED FOR HIS WILDLY CARNIVAL-ESQUE PERFORMANCES AS HALF OF POPULAR ‘TRICK-OR-TREAT-TRANCE’ DIGITAL MUSIC/ANIMATION DUO HOOLIGANSHIP AND FOR CO-FOUNDING THE UNDERGROUND ANIMATION COLLECTIVE CARTUNE XPREZ.

Burr’s new work, Special Effect sees him branch out into solo audiovisual performance in the form of a live experimental television program, in which Burr presides over a succession of increasingly bizarre digital images, replete with the interruptive agenda of commercial breaks. Drawing on a surprising wellspring for its inspiration, Special Effect features Burr’s typically highly physical performance bent to more experimental ends, collaged into the action via green screen, as the master of a strange ceremony.

Tell me about the genesis for Special Effect—where did it come from?

I have a habit of incessantly drawing, somewhat aimlessly, in between large-scale projects. It calms me down. I’ve been in this rhythm for years. Last spring, after finishing my project Green | Red, I had just rewatched Stalker (Andrei Tarkovsky’s legendary 1979 sci-fi film) and found myself making drawings based on paused frames of the film. The specifics of the movie weren’t in those images, but some of the mood contours were—the figures, choreography and architecture. Something about this really gelled…and so I decided to explore them in four dimensions. Also, around this time, I was talking with a bunch of other video artists and animators and noticed there was a thread here that these artists were also inspired by—there’s been a serious Stalker wavelength growing fresh over the last few years. I found lots of personal resonances with this film…and so did others. So that’s really where the project comes from, how it was birthed.

The next stage was shooting in some abandoned sites?

Yes, I met up with a group of friends who were keen on exploring ruined/abandoned sites around New York. I started tagging along with them, borrowing friends’ cameras and shooting landscape footage—this eventually was integrated into the animated segments of Special Effect, in various forms. It turned into this self-propelling journey into the armpits of America, delving into our zones of exclusion to find my own story somewhere in the Stalker script.

Do you remember the first time you saw Stalker?

I first heard about the film as a resident artist at the Macdowell colony, the oldest artist colony in the States, in New Hampshire. I used to take pathless walks through the winter woods there and once a friend accompanied me and he was like, “This is just like being in Stalker.” At the time I hadn’t seen it but he meant the stillness and the thin trees and how you could hear your footsteps in the thick carpet of leaves left on the ground. His description of the film mesmerised me, but I never got around to watching it until about a year later when I was touring around Europe. I had a copy of it on my laptop and during an overnight trip from London to Antwerp I thought, “Let’s fire it up!” I remember getting into the station and having time to kill before I could find my host there and feeling grateful there were so many hours left in the film. It felt like this dreamy, endless drift through parallel worlds, perfect for my transient, half-awake state. Only my world was a bit drier—compared to the endless puddles and rain and splashing that is like a running joke through Stalker.

Peter Burr, Special Effect, courtesy the artist

The audience for Special Effect can see how you’ve responded to those bleak Tarkovskyan pans—but yours are really heavily effected. What are you trying to do with the motion graphics in this work?

I think a lot about transforming the thumbprint of images. How can this be done to icons of pop culture that, untransformed, propel us into nostalgic mental loops? How can I strip off the marks of specific software that read as emblems of their design? The signature ‘look’ of software is something I think about a lot. Each program wants to announce itself. But there are a million different paths in there to smear or shift the markings, to carve out something unique with the same tools that everyone’s using. I’m not into speaking with the voice of a generation or being the voice of a particular piece of software. I think I really work adversely to that.

With this whole project, there was an element of dealing with iconography, of Stalker. Dealing with tradition. But at the end of the day it’s not replicating. I’m trying to invent something new from it. Something that actually feels like its own thing. I wanted to work with some of the elements I admired from the film, like the Tarkovskyan pans, but let them be transformed. I was aiming to create a new feeling that’s rooted in my own feeling of the world just as much as it is rooted in this source. I guess…in creating a project that’s about ripping off the greatest film ever, I feel like it’s also important for me to push away from it.

Like you push away from demo-ing ‘high’ technology with the software thumbprint?

Yeah, I’m not interested in a display of the newest technology. Special Effect shares the load around—it’s a pretty tangled knot of high-end and low-end software. To me it’s important to obscure those distinctions in the work. It’s not about the newest, coolest thing. I like using crappy free technology too. Or if I’m using familiar software then it’s about misusing it and using it in weird combinations and configurations, ways that aren’t emblematic when you think about the software.

Is that why you’re interested in incorporating the live performance element?

It adds an angle of chaos. With this kind of motion graphics work it is so easy to get stuck in the structure of the computer process. I write a script, draw a storyboard, then execute the blueprints. But straightforward in this way, it lacks something. Adding layers of liveness to it all makes it feel more honest. There’s the effect of real bodies, this risk of everything falling apart, the lasers threatening to blind you…! It makes you watch it all very differently than you’d watch The Hobbit (3D or no-3D).

I know you watched a lot of cartoons as a child and that drew you into the world of animation; that sensibility permeates Cartune Xprez but is pared back, thinned out in Special Effect. What’s the relationship with TV in this work? Why structure it as a TV program?

With television, my references are all very different today than they were a decade ago. I don’t think I’m alone with this. I haven’t watched ‘television’ in years—the internet and my own art practice replaced that for me. This definitely creates space for me to play with the idea of television. It’s almost an imaginary object for me now. We’ve had this shift away from the fascist architecture of media—TV programming—into user-controlled, user-generated media. There’s no tolerance of boredom now and that really interests me. There’s certainly a confrontation with boredom in the show—it deals with Stalker, after all! I guess I’m trying to reconcile the slow, quiet, maybe confusing drifts with really short-attention-sapan-overload segments.

Of course, I grew up watching over eight hours of TV a day until I went off to college, so there’s also a very real imprint of its effects on my imagination. I don’t know exactly why, but it just feels intuitive to make fractured, commercial-interrupted, channel-surfed work. My attention span is all out of whack.

I guess that’s informed my way of approaching things now. Special Effect isn’t ‘about TV’—I don’t even know what TV is any more. Like I said, it’s an imaginary system for me. Because I don’t watch TV but remember it—and especially commercial breaks—I’m like, “I haven’t seen one in a while, so let’s have one, and let’s make it fun!.” So it’s kind of like a late 70s vision of a dystopian future, looked back on through the lens of 80s and 90s TV, from the position of early 2013. If that makes sense.

Peter Burr, Special Effect, Brisbane, Melbourne, Meredith Music Festival, Adelaide, Dec 5-10, 2012; http://otherfilm.org/peter-burr-cartune-xprez/; Museum of Moving Image, NY, 18 Jan 18, 2013; www.peterburr.org

RealTime issue #113 Feb-March 2013 pg. 20

© Danni Zuvela; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

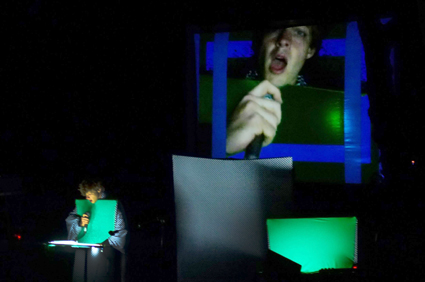

Documentary Of AKB48 Show Must Go On

© 2012 Aks Inc. / Toho Co., Ltd. / Akimoto Yasushi, Inc. / North River Inc. / Nhk Enterprises, Inc.

Documentary Of AKB48 Show Must Go On

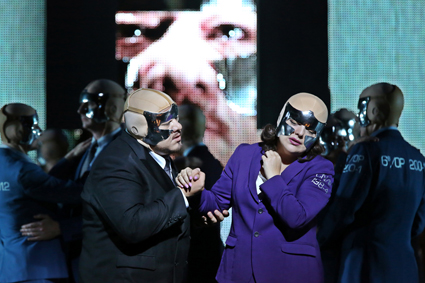

BEFORE DISCUSSING DOCUMENTARY OF AKB48: SHOW MUST GO ON (2011) WHICH SCREENED IN THE 16TH JAPANESE FILM FESTIVAL ACROSS AUSTRALIA, HERE ARE SOME INTRODUCTORY POINTERS ABOUT THE JAPANESE POP GROUP, AKB48. THEY ARE A COLLECTION OF GIRL SINGERS COMPRISING THREE PRIMARY TEAMS OF 16, BASED AT A LIVE THEATRE FOR FANS IN AKIHABARA, FORMED IN 2006 BY EX-AIDORU (IDOL MUSIC C1980s) LYRICIST AND MANAGER YASUSHI AKIMOTO.

Their music is mostly a softened yet pneumatic Euro-disco à la Stock-Aitken-Waterman, designed to be uncontrollably memorable. The vocals come from a team’s 16 voices singing in unison, usually without harmony lines, generating a sports-like karaoke of kiddie chants. Between 2011-2012, AKB48 released 10 singles in Japan (population 127.5 million), each selling on average 1.2 million. (Between 2011-2012, Katy Perry released eight singles in Australia, population 22 million, each selling on average 0.14 million.)

But Pop Music in Japan is a different being. The Idol syndrome that first peaked in the 80s was based on idolatry, figurine worship and the rupturing imperfection of human amateurism, which was perceived to define the ‘idol’ as a shimmering deity in human form. (Only 40 years earlier, Japan collectively subscribed to the Emperor’s divinity.) Japanese Idol music employs crass electronic synthesism as an environmental context for highlighting human expression—hence the off-tune, over-emoted, unadorned voices of groups from Pink Lady and Onyanko Club to SMAP and Arashi.

The AKB48 documentary Show Must Go On is an exhausting ride into the maelstrom of Idol culture. On the surface it appears as yet another exposé of the ‘real world’ behind those ensnared by the machinations of show business. But Show Must Go On presents with uncompromising clarity what is within the surface of Japanese Idol culture.

A number of narrative incidents shape the documentary’s trajectory across the year 2011. The major one is the Great Tohoku Earthquake and resulting tsunami (referred to in Japan as 3/11). We see six members from the A-Team travelling by bus into Otsuchi, Iwate in June. They stare in silence into the de-spatialised devastation we can also see through the bus windows. The members on the bus silently try to read what was once a recognisable landscape.

As they descend, the six young women move differently: they now resemble figurines, exuding the subtle power of Japanese women engaged in formal ritual. The stilted slowness of their bodies and their almost indiscernible head-bowing are signs not of obsequiousness, but regality and divinity, here performed through the minutiae of bodily control as if they are no mere mortals.

They straddle the makeshift stage and formally introduce themselves and their “stricken area support tour.” Suddenly they transform, leaping into synchronised callisthenic moves, singing atop the blaring backing track of Heavy Rotation (2010). Dressed not in their usual glitzy uniforms, which seem borrowed from the mystical princess sub-genre of anime like My-HiME (2005-8), they wear white tour T-shirts, gym pants and trainers. The location sound is similarly raw: it accentuates AKB48’s aural presence as frail human vocals enmeshed in a dizzying multiphonic synthesis.

At one point, the camera hand-tracks behind a gaggle of Japan Self Defence Force members corralled as relief workers, dressed in military garb and patiently listening. It’s the first of many moments in the documentary’s audio-vision where AKB48’s music—performed live or played in a public space—seems dislocated from its surroundings.

Yet at that very moment, it also evidences the means by which the music fuses with its surroundings. Because when such ‘inappropriate’ music occupies a social realm—here, tacky disco pop amidst the ruined townships post-3/11—a reality effect seeps back into the music to intone it with opposite sentiments. In this instance, Heavy Rotation begins to sound less sprightly and bouncy and more drained and hollow.

Documentary Of AKB48 Show Must Go On

© 2012 Aks Inc. / Toho Co., Ltd. / Akimoto Yasushi, Inc. / North River Inc. / Nhk Enterprises, Inc.

Documentary Of AKB48 Show Must Go On

Another major narrative incident is the AKB48 22nd Single Election held June 9 at the Budokan in Tokyo. Having spent three months in Tokyo shortly after 3/11, much of what is in Show Must Go On brings back memories for me of the transformation and reconstruction which frenetically hit Japan over that time. The AKB48 Election was accorded an amount of media attention proportionate to the drastic re-shuffling of the Democratic Party of Japan’s cabinet under Naoto Kan during the post-3/11 crisis. Images of besuited old men and uniformed young girls each engaged in popularity polling were everywhere.

The AKB48 Single Elections manifest how ‘popularity’ can govern with chaotic yet ultimate power in Pop Music, as team members who get to actually record each new single are selected by their huge Japanese fan base (they sold out the Budokan). How better to ensure attraction to AKB48 than by having one actively dislike certain members in order to like others. That’s how the Single Elections have unfolded since 2009, and Show Must Go On unflinchingly reveals the emotional exhaustion and terrorising debilitation its members wilfully suffer.

When Yui Yokoyama achieves 19th place in Team B, she appears onstage, hyperventilating from the trauma of succeeding. We quickly cut to a later interview where she’s mildly laughing at it herself, querying what she felt. It’s the first of the documentary’s onslaught of such para-bipolar incidents which are performed with an embedded schizophrenic calm typical of Japanese emoting and self-presentation.

When the dramatic long-winded announcement of the first place is blared over the Budokan PA, we see No.1 contender Atsuko Maeda bobbing in her seat like an epileptic. Here is a star, suffering in public, about to succeed, filmed by multiple cameras, surrounded by her colleagues—but everything and everyone around her treats her as a non-existent entity. Show Must Go On documents such instances of Japanese behavioural customs, proving AKB48 to be a simulacrum of Japanese endeavour: completely fabricated, excessively exploitative, undeniably fictitious, yet absolutely affecting.

Backstage after the announcement, we focus on Yoko Oshima, this time demoted to second place. The onstage male announcer’s barking drowns her, indifferent to her emotional collapse. Then an AKB48 ballad blares through the PA: it’s like sonic salt poured onto her gaping wounds. She stands with her back to us, moored in the bowels of the Budokan’s subterranean infrastructure, facing an air-conditioning duct. In the ugly miasma of lo-light video grain, cables and ducting swirl around her like a deadly forest. It’s a chilling anime icon—the mystical schoolgirl princess ensnared in a cruel environment. The camera zooms in slowly on her shadowy back: a sublime moment in Pop Music audio-vision: a portrait of the dark self away from Pop’s photosynthetic brightness.

–

RealTime issue #113 Feb-March 2013 pg. 21

© Philip Brophy; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

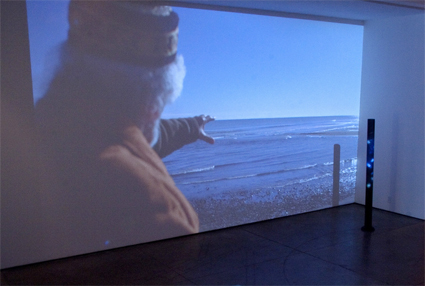

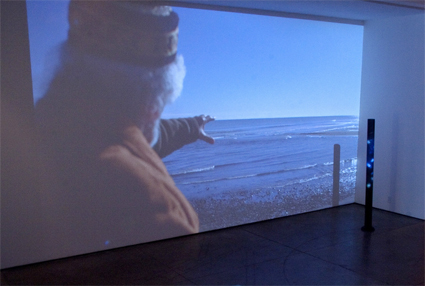

Thornton in front of Mother Courage

source ACMI & Mark Gambino, courtesy of the artist and Scarlett Pictures

Thornton in front of Mother Courage

“IN THE LAST 30 YEARS INDIGENOUS CINEMA, ART, EVERYTHING, HAS BEEN MIND-BOGGLINGLY EXPLODING IN ALL DIFFERENT DIRECTIONS AND DIFFERENT WAYS. IT’S A VERY EXCITING TIME—WE’RE CREATING A NEW WORLD.” WARWICK THORNTON’S ENTHUSIASM IS INFECTIOUS, AND DOESN’T SEEM DAMPENED BY HOURS SPENT SETTING UP HIS NEW INSTALLATION, MOTHER COURAGE, IN THE BOWELS OF THE AUSTRALIAN CENTRE FOR THE MOVING IMAGE.

Not content with having written and directed one of the greatest Australian features of recent decades—Samson and Delilah (2009)—the Alice Springs filmmaker is pushing into new artistic territory. “I wanted to create stuff where I could go off and do it myself, where I don’t need 100 crew and $3 million,” Thornton explains when asked about his push into the visual arts. “I shoot work for other people in between writing and getting my own films up, but it still wasn’t enough to vent creativity, to vent ideas. You have 10 ideas a day and five years down the track one of them might arise as a film. So it grew out of that—a frustration with having lots of wonderful ideas and not enough outlets.”

Mother Courage is Thornton’s second installation—his first foray into gallery-based 3D video work was Stranded (RT102) for the Adelaide Film Festival in 2011. That piece saw Thornton tied to a neon cross, suspended over the Western Desert. Mother Courage retains the setting, but focuses on an elderly Indigenous painter (played by real life artist Grace Rubuntja) reminiscent of Delilah’s exploited Nana in Thornton’s debut feature.

The first thing we see upon entering the darkened gallery space is a battered van, softly spotlit in the middle of the room. Red dust coats the bumper and tyres, bespeaking long drives across Australia’s centre, while paintings hang from the van’s sides. A newspaper wedged against the dirty windscreen features a headline about troubled Top End Aboriginal communities, while a red handprint on the van’s front speaks of Indigenous ownership. Then, suddenly, we perceive movement in the back of the van and realise there is an elderly woman inside, painting.

Closer inspection reveals the action is playing out on a life-sized video screen inside the van, but the clarity of the footage conveys a disconcerting impression of real presence. This is only reinforced when we walk around the back of the van to find the image’s reverse playing inside the open rear door. From here the elderly painter faces us, as she carefully applies brush strokes to her work, while a young boy (Elijah Button) sits beside her playing air guitar to the sounds of the Green Bush country music show blaring from a radio.

Thornton’s films have always spoken to each other through recurring characters and overlapping concerns, and Mother Courage continues this intertextual dialogue. “You can learn more about Mother Courage, and the reason she’s in Melbourne and not on her homelands painting, by watching Green Bush,” says Thornton, referring to his classic 2005 short about a late-night radio DJ in a remote desert community. “That film talks about the violence and the vicious cycles of community life. I can’t explain everything, but if you create those small connections with what you’ve done before or what you might be doing next, it becomes a more immersive journey.”

Thornton’s work also deliberately evokes wider connections with contemporary Indigenous politics and culture—an explosion of activism and creativity that has barely registered with many non-indigenous Australians. Green Bush, for example, prominently features Gary Foley’s speech on Indigenous rights from a Sydney stage during a Clash concert in 1982. Samson and Delilah tips a hat to Bart Willoughby and the soundtrack to Wrong Side of the Road (1981) when a homeless man sings the anthemic “We Have Survived” beneath a highway overpass. “They are key things for most Indigenous people and they’re unique. And a lot of non-indigenous people haven’t heard that song or that speech, and then it’s like, ‘Wow, Gary Foley spoke at a Clash concert?’ It’s great.”

Thornton himself was similarly led to Bertolt Brecht via the circuitous route of John Walter’s documentary Theatre of War (2008), about the staging of a production of the playwright’s classic Mother Courage and Her Children in New York. Inspired by the film, Thornton sought out the original play and was immediately struck by parallels between Mother Courage’s travails as an itinerant trader during Europe’s Thirty Years’ War and the plight of Indigenous communities in the Western Desert. “There are some amazing correlations between this lady and what’s happening in the desert at the moment with Indigenous people, having to move off their country to follow certain elements to be able to survive,” Thornton observes ruefully. “I’m using Brecht’s back story in a sense, so anybody with any knowledge of what happened to his Mother Courage can align it with this character.”

Warwick Thornton, Mother Courage (detail), 2012

source ACMI & Mark Gambino, courtesy of the artist and Scarlett Pictures

Warwick Thornton, Mother Courage (detail), 2012

Thornton’s Mother Courage occasionally pauses to hold up her painting to viewers, as if plying for passing trade. Other paintings are hung on the sides of her van, making the vehicle a portable one-woman commercial gallery. The installation was first unveiled at last year’s dOCUMENTA in Kassel, Germany, where the vehicle was often parked beside crowds queuing for various exhibitions, making the painter’s position vis-à-vis the international art market clear. “It’s like in Samson and Delilah—the artist gets 100 bucks, and the art is then sold on for $10,000,” says Thornton of the rampant exploitation of Indigenous painters.

As in Brecht’s Mother Courage, however, Thornton has left his character’s situation and actions open to multiple readings. “In a lot of the stuff I make, I try to not dictate a right or wrong, a yes or no. Some people will walk in there and feel really passionate and sad about this woman—she’s confined in this van, and doesn’t really do anything but paint. And the kid seems really bored. Another person will be really empowered by the idea that this woman has created a form of self determination and gotten out of this vicious cycle of some communities—this sister’s doing it for herself, you know, and she’s gone straight to the source of what she knows, which is art.”

However we respond to the character’s situation, there is a painful sadness and sense of dispossession underlying the scene evoked by Thornton. While traditional dot paintings hang on one side of the van, on the other is an almost childlike image showing giant black blocks labelled “grog” sitting atop the desert sands as numerous black stick figures fall about around them. “You’re a captive audience,” we hear DJ Kenny say over the radio to his prison listeners, and the bitterness in his voice is only slightly mollified by wry humour. Yet there is also hope in Mother Courage’s calm, persistent process of creation—a hope that resides in the ongoing resilience of a culture that has survived, despite everything.

For all his social concerns, it is Warwick Thornton’s ability to sympathetically capture the hopes, possibilities and foibles of his characters that makes his work so affecting. “You always draw upon key emotions, you know?” Thornton explains, stripping his approach down to its essence. “It all boils down to good storytelling—that’s what I’ve found.” When asked whether he intends to continue with installation work, he replies, “I love all forms, so I just flow with it. It’s about the idea. You hear an amazing, real story and you think should this be a doco, a feature, a video installation or a collection of photographs? The story will tell you how it should be made.” With another feature and television series on the way, Thornton’s flow of stories—in all different directions and different ways—shows no sign of abating.

Mother Courage, installation, writer-director Warwick Thornton, actors Grace Rubuntja, Elijah Button, commissioned by ACMI and dOCUMENTA (13); Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne, Feb 5-June 23

RealTime issue #113 Feb-March 2013 pg. 22

© Dan Edwards; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

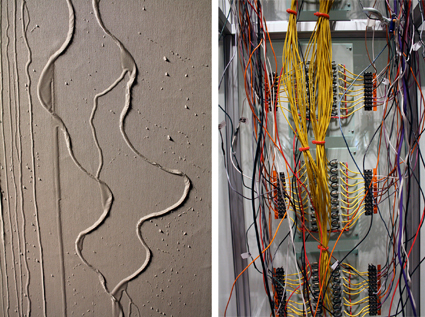

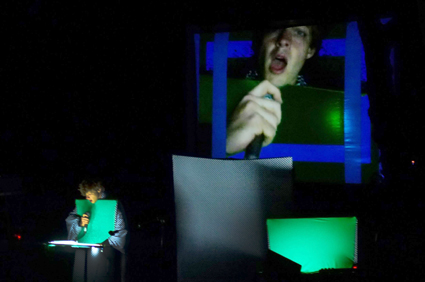

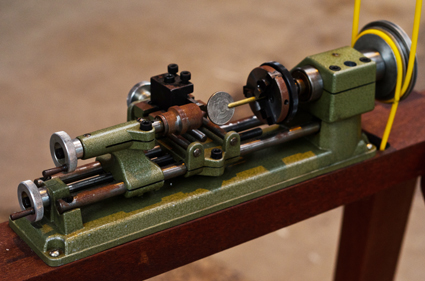

Colleen Ludwig, details of installation Cutaneous Habitat: Shiver, ISEA 2012

images courtesy of the artist

Colleen Ludwig, details of installation Cutaneous Habitat: Shiver, ISEA 2012

ISEA 2012 ARTISTIC DIRECTOR ANDREA POLLI’S CURATORIAL CONCEPT FOR MACHINE WILDERNESS: RE-ENVISIONING ART, TECHNOLOGY AND NATURE TOOK A STRONG ECO-POLITICAL APPROACH TO DIGITAL INTERACTIONS WITH THE ENVIRONMENT. ISEA 2012 IN ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO MEDIATED BETWEEN THESE INTERSECTING WORLDS FROM CREATIVE RESIDENCIES AT THE LOS ALAMOS NATIONAL LAB AND SETI (SEARCH FOR EXTRA TERRESTRIAL INTELLIGENCE) TO EVENTS AT THE INSTITUTE OF AMERICAN INDIAN ARTS IN SANTA FE AND THE NATIONAL HISPANIC CULTURAL CENTRE IN ALBUQUERQUE.

While the ISEA symposium began in 1988 in Utrecht and Groningen with a focus on computer-generated art, such as fractal graphics and emergent ‘net art,’ the artworks and presentations now extend into the diverse forms of ‘post-media’ practice; from fusions of performance and animation to sound walks. The focus of this review is neither the physical computing nor the augmented reality and QR codes [matrix barcodes. Eds] that may represent key typologies within ISEA artworks in 2012. Rather, in the sometimes bewildering density of artworks and parallel conference sessions, the presence and absence of water became a connecting thread for this writer.

te urutahi waikerepuru, new zealand

Te Uratahi Waikerepuru, Pou Hihiri

image courtesy the artists

Te Uratahi Waikerepuru, Pou Hihiri

A Maori art project conveying the importance of wai (water) from Aotearoa/New Zealand to ISEA in New Mexico catalysed this interest on my part. As part of ISEA at 516 Arts (a gallery known for its pursuit of radical environmental and social art projects), Maori artist Te Urutahi Waikerepuru installed the work Pou Hihiri, an electrified totem. The work was part of the collaborative exhibit Te Hunga Wai Tapu curated by Ian Clothier. In a well-attended conference workshop, Te Urutahi and her father, kaumatua (elder) Dr Te Huirangi Waikerepuru spoke on the importance of wai in Maori cosmology.

Water is a key element in the set of relations and flows that bind us to the environment. Te Urutahi’s Pou Hihiri represents the ‘becoming of the universe’ and the rise of the matriarchal principle. The work flickers with potentiality, represented by an array of lights within a wooden pole figure. Hihiri describes the power for change in hydro energy, kinetic energy, molecular energy and lightning. Te Urutahi positions Pou Hihiri as the first in a series of forms that will represent “the birth/physical manifestation of the universal elements of natural lore according to Matauranga Maori concepts.” Maori knowledge and science converge in the concept for the artwork.

While ISEA was taking place, a multi-tribal hui (meeting) in New Zealand overwhelmingly backed a resolution calling on the New Zealand government to halt the sale of Mighty River power company shares. At ISEA, the ‘wai’ water workshop, like the contentious hui in Aotearoa, aimed to produce a framework for recognising Maori proprietary rights and interests and spiritual ties with water. Dr Te Huirangi’s disarming question of how one can ever sell air or water to corporate interests, or interrupt the natural ‘flow’ of water as a complex system, resonated with the international audience.

william wilson, usa

Maori campaigns against continuing colonial attempts to undermine their ‘mana’ or sovereignty over water are echoed in the indigenous struggles in South-West America. Navajo artist William Wilson related how Arizona Senator John McCain advocated the construction of municipal water pipelines in exchange for waiving indigenous rights to water. Vehement opposition by Navajo/Hopi campaigners defeated the bill in February 2012, lending hope to the Maori struggle. Like Pou Hihiri, Wilson’s collaborative artwork eyeDazzler 1 (2012) for ISEA connects ancient cultures to contemporary mythologies about technology by weaving a QR code into a traditional textile pattern.

seoungho cho, korea

Water was represented as both a politically fraught site and a meditative force in several works at the Albuquerque museum. Korean artist Seoungho Cho’s multiple video seascape Horizontal Intuition 14 (2012) momentarily alleviated my island-dweller’s anxiety about the distance from the ocean. A rhythmic abstraction was created by the waves of distant seas, scored with the coloured stripes of computer-generated glitches.

colleen ludwig, usa

Deeper into the museum I found a group of women from Albuquerque delighting in actual trickles of water around a highly plumbed, cabled and programmed structure. Colleen Ludwig’s (USA) interactive piece Cutaneous Habitat: Shiver (2012) was comically mechanical as switches clicked and released water in response to human presence. One woman commented, “maybe if we stand here long enough it will start to rain in Albuquerque.” Decreased rainfall as the climate shifts, the smaller than anticipated size of Albuquerque’s subterranean aquifer and their rising population constantly remind the inhabitants of the value of water. (See video footage here.)

marc böhlen, canada

During the lively ISEA Downtown Block Party participants were offered various combinations of mineral waters, mixed by a computer algorithm, from a mobile water station. Canadian artist Marc Böhlen’s WaterBar (2012) filtered water through mineral rocks from politically charged locations. The filtering rocks included quartz-filled granite from Inada in the Fukushima province, site of the 2011 nuclear meltdown; marble from Thassos, Greece “at the beginning and end of democracy;” and limestone from Jerusalem/Hebron, Israel, “source of eternal conflict and shared hopes.” (See video of WaterBar here)

joana moll, spain & heliodoro santos, mexico

The Rio Grande that separates New Mexico from border states is siphoned for irrigation from Colorado to Texas. During a conference break, I found the shallow, murky river amongst the willows and undergrowth behind a conference building at the National Hispanic Cultural Centre. The live-streamed video work The Texas Border (2011) by Joana Moll and Heliodoro Santos reveals the Rio Grande as a politicised body of water in the context of border crossings by illegal migrants from Mexico. A grid of 15 web cameras streaming live CCTV video documents people wading or boating across the river. The video is sourced from BlueServo, a citizen vigilante website designed to police the border through home webcams run by the Texas Border Sheriff’s coalition. The grainy shapes of those valiantly attempting to cross the river become moving points of light in the low resolution images, reinforcing the precarious existence of the cameras’ targets.

crossing water, becoming someone else

The national borders that cut through cultural-linguistic bonds were the focus of a key panel at the National Hispanic Cultural Centre. Veteran Cuban-American performer Coco Fusco and panelist Vicki Gaubeca, from New Mexico’s Regional Centre for border rights, situated the migrant body as the “ultimate frontier of technological colonisation.” Gaubeca outlined how Operation Streamline has doubled the number of US Border Control agents since 2003. Smart technologies such as cameras, sensors, six unmanned drones and 700 miles of fencing are used to police the border. The privatisation of prisons has resulted in the construction of massive centres for the detention of migrants, described by Gaubeca as a moneymaking venture. Fusco suggested that the US laws affecting migrants create new categories of people who are criminalised. Migrant imprisonment tears families apart, often detaining those with no criminal record. Fusco’s new work is concerned with migration via sea crossings from Cuba. She mused, “the moment when you lose connection with the land, the moment when you migrate, is the moment when you become somebody else.”

teri rueb & larry phan, usa

ISEA events extended beyond Albuquerque to exhibition sites around Santa Fe and Taos. Teri Rueb and Larry Phan’s (USA) location-specific sound walk No Places with Name: A Critical Acoustic Archaeology (2012) at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) was a resonant, multi-sensory experience. Fitted with headphones, we meandered in the desert heat along a trail dotted with cacti and wild flowers, listening to moving interviews from indigenous artists, anthropologists and geographers. One speaker related how a lost boy was found, clothes dry, miraculously transported to the other side of a dividing river. Silences in the audio walk signalled information held sacred and kept from outsiders.

laurie anderson, dirt day!

Without sustaining and valuing water resources all living beings are endangered; a stark fact made apparent by many of the digital artists who brought their work to New Mexico. Near the end of the conference, media artist Laurie Anderson performed her new work Dirt Day! at the Kimo Theatre. The performance spanned eco-politics, inter-species communication and Anderson’s continued fascination with the ways we receive and interpret language. With mesmerising rhetorical charm she mused that technological art has now moved beyond the instant gratification of speed to the attuning of our potential as “meaning-making machines.”

Although many artworks at ISEA 2012 still beeped, chirped or shook in response to human presence, the fairground attraction mode of early electronic art was often supplanted by wonder that could transmute into political reflection. An ecological approach to technology emerges in Machine Wilderness as a means to reveal, as philosopher Félix Guattari (1989) once observed, our immersion socially, psychologically and inevitably in the ‘environment.’

18th International Symposium on Electronic Art, ISEA 2012, Machine Wilderness, Albuquerque, USA, Sept 20, 2012-Jan 6, 2013

RealTime issue #113 Feb-March 2013 pg. 23-24

© Janine Randerson & Te Urutahi Waikerepuru; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Tobiah Booth-Remmers, Lisa Griffiths, Lewis Rankin, Skeleton

photo Chris Herzfeld, Camlight Productions

Tobiah Booth-Remmers, Lisa Griffiths, Lewis Rankin, Skeleton

AFTER A STERLING CAREER WITH ADELAIDE’S AUSTRALIAN DANCE THEATRE AS AN ASTONISHINGLY FLEXIBLE AND DYNAMIC DANCER, AS WELL AS ASSISTANT CHOREOGRAPHER, LARISSA MCGOWAN HAS EMERGED IN RECENT YEARS AS A BRIGHT NEW CHOREOGRAPHIC TALENT.

McGowans’ first full-length work, Skeleton, will premiere at the 2013 Adelaide Festival and then play at Dance Massive in Melbourne. Meanwhile, the short work Fanatic, which premiered in Sydney’s Spring Dance festival last year will feature as one of three works in Sydney Dance Company’s De Novo, opening in March.

Born and dance-trained in Brisbane, McGowan subsequently graduated from the VCA, joined ADT in 2000, toured internationally with the company and became assistant choreographer to ADT Artistic Director Garry Stewart in 2008. She’s won Helpmann, Green Room and Australian dance awards; created Zero-sum for WOMADelaide in 2009; was a guest choreographer for two seasons of So You Think You Can Dance; greatly impressed with Slack, performed by ADT in the 2009 Spring Dance season (RT94, p38) and toured to France and Holland by Link Dance Company; created Transducer for a Tasdance double bill; and premiered Fanatic in Spring Dance 2012 for Sydney Dance Company’s Contemporary Women program.

fanatic

Fanatic is as physically precise and dextrously realised as you would expect from McGowan. Three dancers lipsynch the YouTube voices of besotted fans of the Alien and Predator films, but more than that they become the creatures, at once funny and frightening. McGowan tells me that her collaborator on Skeleton is theatre director Sam Haren: “We did a piece many years ago, a solo work made on myself, called Theatrical Trailer to Alien 5. Fanatic, for Spring Dance last year, was an extension of that. The process with Sam was just so interesting because I was working with somebody from a theatre background. So we thought, why don’t we use this process to make a full-length work?” That work is Skeleton.

I spoke by phone with McGowan about Skeleton, a work that conjures up aspects of the artist’s childhood memories centred around certain beloved objects and cultural artefacts. But more than that, it’s about the body’s dangerous engagement with those objects, be they bikes or bats (see our cover image). Fundamental to that, of course, is damage to the skeleton. This has led McGowan not only to reflect on growing up and physical trauma, but also the nature of the skeleton, including the ways that artists regard it and the prostheses like high-heeled shoes and instruments with which we extend it.

How would you describe the structure of Skeleton?

A puzzle. Pieces of life you see being formed and re-formed onstage, conjuring questions about who the person was, what they looked like, what kind of life they lived and how they died. It’s been a really great way to structure a work choreographically, exploring in a kind of archaeological way, putting things together. For me it’s really about the material reality of the skeleton, that final trace of a human being, and about traumas and their effect on our psyche in a collage of images.

When you say a collage, what sort do you have in mind?

The five dancers in this work are very different, unique-looking movers. They’re oddities in their own way, fused together. And the objects we’re looking at in Skeleton have pretty much come from 80s, 90s popular culture. They’re things that remind me of my youth, and movies at the time.

What kind of things?

Skateboards and BMXs and bats—all the things that can cause trauma just through playing. The people I researched in order to make this work were looking at the same era of objects. For instance, Ricky Swallow is a phenomenal Australian artist who makes objects—his skulls resonate with a dark kind of feeling. I like that playful, ironic look—the skull in a hoodie—that brings up things from my past that I think are dark, but humorous in some way.

We have five objects and five dancers. There’s a bike, a skateboard, a baseball bat. There’s a T-shirt because at the time people were wearing slogans. There’s also the heel of a shoe. Some of these objects came from looking at the work of UK artist Nick Veasey who does amazing X-ray image stuff where you actually see the ‘skeleton’ of an object. It’s really quite beautiful. There’s a bone-like stability [in the shoes in Veasey’s picture] that looks like an extension of the bone of a woman’s leg through the heel to the ground. I find it interesting that things that we use and wear really can become a part of our own body structure. [See http://twistedsifter.com/2010/05/x-ray-photography-nick-veasey/]

Is there a design element in Skeleton beyond bodies and objects?

There are screens that move across the space in order to suggest the feeling of things being removed and put back in place, but you don’t actually see a dancer or object actually enter. Design has become a huge part of this piece.

Lisa Griffiths, Larissa McGowan, Skeleton

photo Chris Herzfeld, Camlight Productions

Lisa Griffiths, Larissa McGowan, Skeleton

And who has designed it?

Jonathon Oxlade. He’s quite amazing. I wanted something very simple and very clear in its design in order to enhance what’s going on in the movement onstage. And it’s really done its job. It’s great.

And what about sonically? In what I’ve seen of your work there’s a very precise connection between sound and movement.

I think it drives the movement that I do. I love to hear layers. That’s one of the things that’s amazing about the human body when we’re trying to make movement—just the number of layers and systems within our bodies that can work so cohesively. The composer is Jethro Woodward whom I’ve worked with quite regularly. He can work with any type of instrument. It’s a recorded score but it’s going to be tricky because, as usual for me because I enjoy it, it will work very, very tightly with the movement, [but not all the time] because the work needs layers and it needs texture.

Would you like the audience to go away sensing the body as a bit more complex and strange?

Well, that would be lovely if it were possible. But I really wanted to make a piece—my first full-length work—that actually is about dance. It’s not about the technology that I’m seeing in dance everywhere. I really want to go back and remind myself, and hopefully others, that dance is an amazing artform due to the fact that it’s all coming from inside the human body.

I’m excited to create movement that is still virtuosic without it being the trademark stuff that I’ve done in the past. I’d like to tap into a younger audience that might not know exactly what contemporary movement can be—making it accessible for everyone.

You are performing in Skeleton?

Yes. I really appreciate choreographers who have come from a dance background and who continue to persevere as dancers while making work. I think that being in both worlds really assists in your own practice in both areas. That’s what I strive for.

Are you already fantasising the work that will come after this or is this enough for the moment?

Hopefully Skeleton will give me a platform to start producing new work. I’ve definitely got lots of people I’ve been talking to about future projects. But I feel like I just need to make sure that this one is heading in the right direction first before I jump into the deep end.

–

Adelaide Festival, Skeleton, directors Larissa McGowan, Sam Haren, AC Arts Main Theatre, March 2-9; Dance Massive, Beckett Theatre, Malthouse, Melbourne, March 15-23; Sydney Dance Company, De Novo, works by Rafael Bonachela, Alexander Ekman, Larissa McGowan, Sydney Theatre, March 1-23

See Philippa Rothfield’s preview of Dance Massive 2013

RealTime issue #113 Feb-March 2013 pg. 26

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Matthew Day, Rennie McDougall, Deanne Butterworth, And All Things Return to Nature Tomorrow, Luxembourg residency, Trois C-L, 2012, choreographer Brooke Stamp

photo Phillip Adams

Matthew Day, Rennie McDougall, Deanne Butterworth, And All Things Return to Nature Tomorrow, Luxembourg residency, Trois C-L, 2012, choreographer Brooke Stamp

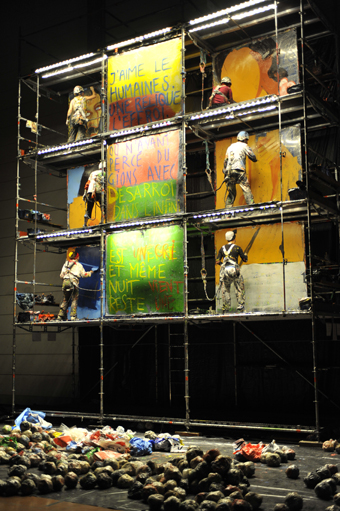

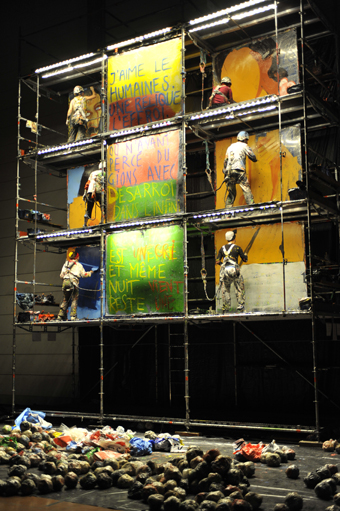

CONCRETE MIXERS DESCEND FROM THE CEILING. DECORATED WITH LIGHTS, THEIR BARRELS SPIN HYPNOTICALLY OVER THE NAKED PERFORMERS. THE SPACE IS INVADED. TOMORROW—THE SECOND PART OF BALLETLAB’S NEW DOUBLE BILL, AND ALL THINGS RETURN TO NATURE TOMORROW—ENDS WITH A UFO ENCOUNTER.

BalletLab’s Artistic Director and choreographer, Phillip Adams is unapologetic about his Spielbergian ‘Hollywood ending’ impulses. “It’s pseudo sci-fi meets kiddie pop,” he says, half-seriously. He is not afraid “to take the bullet” for being on the frontline of dance. “Failing is how you succeed. Somehow we land in our next stage of history,” he says. BalletLab, he explains is on the periphery of Australian dance while being squarely in the middle of it.

Responding to the end of postmodern irony and a return to the utopian impulse to build, BalletLab’s new work has been two years in the making and has covered some serious air miles. There were Adams’ experiences with rednecks and hippies in the Mars-like landscape of the Mojave Desert, and the company’s dance residency in Luxembourg. Underpinning the new work by long-term associates Adams and Brooke Stamp are concepts of utopia. Adams draws on utopian architecture including Frank Lloyd Wright and Paolo Soleri’s Acrosanti [an experimental town in the desert embodying the fusion of architecture and ecology]. Stamp takes a more temporal view. It has been 14 years since they came together, and while the pieces in the double bill are as thematically and tonally distinct as could be imagined, a “common energy and interest in the space” unites the experience, says Adams.

In Stamp’s first choreographic outing for the company, utopia is represented by creating spaces where dance is collectively improvised. Her ethereal work, And all things return to nature, draws on systems of improvisation that she has developed for “responding to sound or text, including philosophical texts.” For this piece, Indigenous Australian cosmology played a pivotal role. The Dreamtime is a description of cosmogenesis with Stamp elaborating on both mythology and science to investigate kinetically charged sound.

The work incorporates recordings by Garth Paine which act in a way to “sound the planets into being.” The Big Bang is said to have been a bass hum rather than an explosion. Physicist and author Frank Wilczek attempts to explain this “never-ending hum of the universal sounding board that permeates the universe” as the “relic of the primordial big bang” in his 1988 book Longing for Harmonies. Curiously, scientists who investigate physics and chemistry find a strong resonance with the ordered nature of music.

Deanne Butterworth, Rennie McDougall, Matthew Day (rear), Tomorrow, development at Abbotsford Convent, 2012, choreographer Phillip Adams

photo Jeff Busby

Deanne Butterworth, Rennie McDougall, Matthew Day (rear), Tomorrow, development at Abbotsford Convent, 2012, choreographer Phillip Adams

Eight channel speakers will bathe the audience in this energy, “activating” them. Stamp tunes into the vibrational hum of the universe to describe the nature of ‘being.’ Her fascination with these themes is most personally expressed when she says that when all else fails, the movement of the universe is one thing she has to fall back on. Asked about both choreographing and performing in her own piece, Stamp explains that it was a way she could embody herself in the same discourse, experiments, language and “field of connectivity through concepts of frequency and vibration.” It was also a way of removing the hierarchy between choreographer and performer. Adams proudly heralds the emerging choreographer’s work as “out on the regions of the galactical/experiential space,” which radically complements his own work.

A preoccupation with sound is also evident in Adams’ piece, manifest in terms of Paine’s experimental music and the choreographer’s inspirational visit to George Van Tassel’s “acoustically perfect tabernacle” and alien altar, the Integratron. Van Tassel was an aeronautical engineer and test pilot alongside Howard Hughes. He began building the structure in 1954 as a place for rejuvenation and meditation (after being spurred on by several encounters with aliens). Wires and strings underneath the building suspend and hold it together—“it’s an acoustic machine that traps energy,” Adams explains. A recording session at the space took advantage of the acoustics; blankets were moved around the room and these sounds feature in the piece.

Standing in the Mojave Desert the domed structure had an immediate effect on Adams as a work of art. Sound baths, healing crystals and “crunchy granola [hippy] types” also offered the right creative fodder for Adams who has previously looked at Australian suburban noir in Axeman Lullaby (2008) and radical 60s and 70s religious groups in Miracle (2011). Adams’ Tomorrow is a reconstruction of his experiences in the desert, including an installation created in situ by architect Matthew Bird and an encounter with gun-toting but friendly ‘white trash’ whose timely arrival coincided with Adams’ responding to the landscape by lying naked near the site of a UFO landing.

Adams has an eagerness to relay his findings, to bare himself and ask the audience to participate in an experience. Seating has been reconfigured around the performers in a circle. What Adams and Stamp both ask is for audience surrender—to sound or to rapturous abduction. Adams is also recognised as a creator of immersive performances, aided by collaboration. “My architect, sound designer and my lighting designer are choreographers”—while Adams takes on their roles. “It gets that deep and I think that has been BalletLab’s defining motif.”

Stamp is both a disciple of and an inspiration to Adams and has followed suit in embracing collaborative processes. Working with MATERIALBYPRODUCT designer Susan Dimasi on sublime hand-painted costumes earned the new show a spot on the Melbourne Fashion Festival calendar. In Dimasi Stamp found someone who worked on her level “where [we’d] have a dialogue about language and sound” or watch the dancers instead of prescribing what the costumes should look like. Dimasi is interested in the constant evolution of the garment through a dancer’s movement and the tears and sweat that alter them.

Adams’ Tomorrow lacks clothing, instead featuring a futuristic woven blanket—created by Dimasi after seeing Matthew Bird’s installation in the desert—which becomes a costume. The naked performers are “designed in the space” by the blanket. It looks painstakingly constructed, the strands of coloured fabric both tribal and un-earthly. Similarly, painstaking research and inquiry has gone into the details of this show. Stamp agrees “the depth of research is extreme. It’s where all the ephemeral properties of performance making exist and are never revealed.”

BalletLab, And all things return to nature tomorrow, choreographers Phillip Adams, Brooke Stamp, The Lawlet, Southbank Theatre, Melbourne, March 15-23

RealTime issue #113 Feb-March 2013 pg. 27

© Varia Karipoff; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Diaphanous, Ochre Contemporary Dance Company

photo Simon Cowling

Diaphanous, Ochre Contemporary Dance Company

CONSIDERING THE FRAUGHT HISTORY OF CONTEMPORARY DANCE IN WA, THE EMERGENCE OF OCHRE SHOULD HAVE BEEN, AS SUGGESTED BY THE PRODUCTION’S TITLE, A CAUSE FOR ‘SEEING THROUGH AND BEYOND.’ WHILE AFTER-IMAGES GLIMMERED IN CREATION STORIES ABOUT THE FIRMAMENT’S CONSTELLATIONS, THE MILKY WAY AND ORION, AND CULTURAL DIALOGUES JUMPED WITH ÉLAN DOWN TO EARTH IN THE CONCLUDING YARNING. IN ITS FIRST OUTING THE FLEDGLING COMPANY AND ITS DIAPHANOUS DREAMS FAILED TO REVEAL ALTERNATIVE DANCE WORLDS.

The filigreed fall of the set’s twine across the performance cosmos resonated with mythological inclusiveness, sharing human life trials and weaving spiritual mysteries into the land. That woven loom, however, presents a daunting panorama where knots are bound to surface, particularly in drawing a Wongi Seven Sisters’ legend in counterpoint with a Greek myth—that of Orion whom Zeus transformed into the constellation of that name.

The performance began in hushed anticipation with Tammi Gisell’s Thoogoorba, as the first sister materialised, softly appearing in star trails with her coolum worn as a crown. As if seeking the materiality of her new identity, she stoked the ground, symbolically laying the coolum’s cradle of birth and sustenance there on the land. Her fluid swaying, the peculiar rhythmic lilt of her gestures bore the strength of Indigenous women who carry and see beyond. Tracking that metaphor further was difficult in the ensuing tension of guardianship of the coolums between the females (the Dreamtime sisters) and males (the fallible creatures of Earth) except that the seduction and final intimacy of man and first sister conveyed the ancient theme of sacrifice in order to issue mortal birth.

Projecting a more violent world, the entanglements in Jacob Lehrer’s Orion’s Belt were forewarned by storyteller Maitland Schneer’s incisive questioning of the audience’s willingness to inflict violence in order to achieve their desires. Have rape and domination replaced the subtle shifts of sexual attraction and/or do the altered power relations between humans and gods reflect a taste for greed and exploitation? The Greeks, young by Indigenous Australian standards, discovered the power of metals and, by extension in contemporary terms, mining’s mixed blessings. Mythologically, the personal rages into high politics: intimacy twists into estrangement as stratified communities commit societal oppression. In dance terms, discrepant power relations emerged in virtuosic displays and harsh duos, raising questions of what this embryonic company aims to achieve. Is the vision a coalition of different perspectives or a device to launch a new company with an awkward amalgamation of Indigenous and non-indigenous artists?

I glimpsed these pressures markedly in the final Yarnin section where a tangled mesh of humour and satire edged towards cultural revisioning of what is told and, more importantly, of what can be told. Choreographers Tammi Gissell and Jacob Lehrer introduced movement ‘joking’ but the gags lost momentum and the storyteller, who might have picked up the threads, was nowhere in sight. The ‘yarnin’ snagged between a racy fireside informality and expectations of a slick Western performance identity. I was left wondering how a company called Ochre might blend cultural distinctions to create a new presence on the Australian stage.

Ochre Contemporary Dance Company, Diaphanous—seeing through and beyond, artistic project director Simon Stewart, choreographers Tammi Gissell, Jacob Lehrer, sound design Josh Hogan, costume, set design Matthew McVeigh, lighting Joseph Mercurio, story consultants Josie Wowolla Boyle, Brownyn Goss, dancers Benjamin Chapman, Joshua Pether, Floeur Alder, Perun Bonser, Nicola Sabatino, Anne-Janette Phillips, Justina Truscott, Matthew Tupper, storyteller Maitland Schnaars, State Theatre Centre, Perth, Nov 22-24

RealTime issue #113 Feb-March 2013 pg. 30

© Maggi Phillips; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lee-Anne Litton, Rick Everett, Encoded, Stalker

photo Matthew Syres

Lee-Anne Litton, Rick Everett, Encoded, Stalker

IN LATE 2012 SYDNEY’S STALKER THEATRE EMBRACED NEW TECHNOLOGY AND DANCE TO SPECULATE ON OUR DIGITISED PRESENT AND FUTURE IN ENCODED. IN BEAUTIFUL ONE DAY, SYDNEY’S VERSION 1.0, BELVOIR AND MELBOURNE’S ILBIJERRI THEATRE COMPANY COLLABORATED TO REFLECT ON AND RE-ENACT PALM ISLAND’S DARK HISTORY AND ITS CONSEQUENCES FOR THOSE WHO CONTINUE TO LIVE THERE.

Encoded delights in the thrills provided by immersive new technologies while angsting over their dehumanising potential. Beautiful One Day conveys the emotional struggle to accept what was once a prison as now home if still oppressive, with the white viewer inevitably feeling complicit in that oppression.

stalker, encoded

In near dark someone, possibly winged, slowly turns toward us, small red-light eyes, a skirt hooping out slightly from the body. Nearby stands another ‘alien,’ skirtless, presumably male. They appear to have aerials. Their bodies are illuminated with Rorschach patterns, perhaps evoking organs, but green. The couple shimmer, beautiful, insect-like, but hi-tech; cyborgs?

A universe opens behind them, stars flowing across a vast Carriageworks wall but, less than cosmic, they soon prove to be part of the grid of a huge abstracted building which will expand, contract and slide vertiginously up and down like a monstrous elevator. Again, something manufactured, eerie. The creatures exit.

Human figures, male and female swirl, leap at the massive projection, conjuring tumbling flight, but then fall into pretty conventional contemporary dance before magically melting into a mass of stars.

The early promise of Encoded soon drifts away into alternations between aerial and dance sequences, with the former providing some fascination moment by moment but without cumulative weight. Bodies hang upside down or mutate into Y-shapes, fly out from the wall towards us, pair off and execute exacting ‘wall dances,’ or form threesome totems, almost alien, but still certainly human. In the end, we are alone with one of the creatures that initially confronted us with its worrying sense of difference—save the oddly insistent gender distinction.

Encoded addresses contemporary anxieties about the prospect of losing “the human in the midst of the pixels” (program note). To do this it celebrates the human capacity to defy gravity by dancing and swinging on rope while exploiting digital technologies to suggest even greater capacities. The result is at times spectacularly cinematic, reinforced by over-emphatic music, but Encoded lacks the cohesion and escalating dynamism witnessed in Stalker’s previous work MirrorMirror (RT94,p36), part of director David Clarkson’s continuing exploration of identity across time and space. The initial tensions and sense of excitement are soon lost. It’s disappointing too that the beautifully enigmatic creatures from the future remain merely emblematic—there is no interaction with the humans, quite unlike that seen between robots and dancers in say, Garry Stewart’s Devolution (ADT, 2006, RT71, p2). In that work hybridised humans sprouted horrifying robotic prostheses. Encoded is, with its almost motionless aliens, a relatively contemplative work in which humans and new creatures neither interact nor morph. Its characters appear to be less than agents in their universe and more the tools of technology, director and choreographer. The digital art team working on the production, however, have made something visually special of Encoded.

beautiful one day

Rachael Maza, Erykah Kyle (screen), Beautiful One Day, Belvoir, version 1.0 & Ilbijerri Theatre Company

photo Heidrun Löhr

Rachael Maza, Erykah Kyle (screen), Beautiful One Day, Belvoir, version 1.0 & Ilbijerri Theatre Company

I’ve read the news and the book (Chloe Hooper, The Tall Man: Death and Life on Palm Island, 2009), seen the documentary (The Tall Man, director Tony Krawitz, 2011) and the four-channel video installation (Tall Man, Vernon Ah Kee, 2011) and now the stage play, Beautiful One Day. The tale of Palm Island exile, discrimination, murder, riot and justice denied is a scar on Queensland’s integrity, but sadly emblematic of national injustices. Each encounter with the story adds more disturbing details and discomfiting perspectives. This account by version 1.0 and Ilbijerri digs into the island’s history and adds a heightened Indigenous perspective side by side with verbatim recreations of pivotal moments in the unfolding tragedy.

The telling of the earlier history of Palm Island casually conjures key personalities, recites cruel, petty rules (courting only 4-5pm, “no laughing,” no bikes…) in what was essentially a slave colony. It recalls public punishments like head shaving, protests and a strike for wages, meat and freedom of speech, and its brutal consequences. 1960 documentary footage (projected in fragments on the semicircular screen that frames the stage) depicts then famous Australian musician Shirley Abicair declaring the island “the site of a bold experiment” to lift up its people while the sound score thumps ominously and whistling mocks this nonsense. The years roll on. In 1986 the inhabitants are given Deeds of Grant to the island, but infrastructure is removed. Then it’s 2004, and Cameron Doomadgee falls victim to Senior Constable Christopher Hurley. Rachael Maza delineates Hurley’s good cop, bad cop virtues and failings and six versions of Doomadgee’s ‘fall’ are mechanically, and chillingly, re-enacted across crime scene floor markings and architectural projections. This sequence and the ensuing court room encounters provide some of the strongest scenes in Beautiful One Day.

Subsequently the production loses focus and momentum, ambling to a conclusion that nonetheless brings home the painful contradictions the inhabitants of Palm Island must live out: the island is not their country, but it has been home for generations; they love it, but it is fundamentally oppressive. We see their faces, projected before us, hear their words, their frustration that a ‘vision plan’ for the island remains unrealised and that, worse, the Act that has governed their lives for so long is implicitly still there. The mix of despair and optimism, however, does not read like contradiction, rather as well-worn stoicism.

Version 1.0 and Ilbijerri have taken on a big subject (a consistent mark of both companies), as theatre must, engaged with it directly and inventively with strong performances on designer Ruby Langton-Batty’s mobile, grassy floating floor before a screen aptly evocative of museum dioramas. One surprising misstep came in the form of the reproduction of the exchange between the embattled police on the ground in Palm Island during the riot and those off-shore coming in with reinforcements. Two performers sit before music stands and deliver the lines deadpan from the verbatim script. The effect is unfortunately comic, but if you’ve seen the news, the book, the film, the installation you’ll know that the police, however you may regard their role in events, were profoundly afraid. The production sidesteps this and the intensity of the riot with ironic cool. Beautiful One Day has been fulsomely praised by reviewers, and some of that praise is warranted, but it is a work that is neither as focused, integrated nor as taut as anticipated.

Carriageworks & Stalker Theatre, Encoded, conception, direction David Clarkson, performers Lee-Anne Litton, Miranda Ween, Rick Everett, Timothy Ohl, digital artist interactive systems, Andrew Johnston, virtual costumes Alejandro Rolandi, architectural mapping design Sam Clarkson, choreographer Paul Selwyn Norton, composer Peter Kennard, multimedia dramaturg and consultant Kate Richard, lighting Mike Smith, costumes Annemaree Dalziel, Carriageworks, Sydney, Nov 28-Dec 1; Belvoir, version 1.0 & Ilbijerri Theatre Company, Beautiful One Day, devisors: AV designer Sean Bacon, performer, cultural, consultant Magdalena Blackley, performers Kylie Doomadgee, Paul Dwyer, Rachael Maza, Jane Phegan, Harry Reuben; other devisors Eamon Flack, David Williams; set & costume designer Ruby Langton-Batty, lighting Frank Mainoo, composer, sound design Paul Prestipino; Belvoir Upstairs, Nov 21-Dec 23, 2012

RealTime issue #113 Feb-March 2013 pg. 29

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Julie-Anne Long and Martin del Amo, Benched, Micro Parks 2013, presented by Performance Space in Association with Sydney Festival 2013

photo Lucy Parakhina

Julie-Anne Long and Martin del Amo, Benched, Micro Parks 2013, presented by Performance Space in Association with Sydney Festival 2013

BEGINNING AT CARRIAGEWORKS, WE PICKED UP A MAP AND STARTED THE SELF-GUIDED TREK THROUGH NEWTOWN AND ERSKINEVILLE TO MINIATURE PARKS IN BLANK LOTS AND TRIANGULAR CORNER BLOCKS FOR MICRO PARKS, A COLLECTION OF FOUR FREE PERFORMANCE WORKS PRESENTED BY PERFORMANCE SPACE AND SYDNEY FESTIVAL.

Benched, Julie-Anne Long and Martin Del Amo’s dance piece, was performed in a wee plot wedged between two houses. The space was charmingly long and skinny with one graffitied wall, one lone central tree, one sunny park bench beyond the reach of the tree’s shade, a partially vine-covered chicken wire back fence and a whole lot of grass. A backdrop of trains pulling into Erskineville Station complemented the dancers’ slow motion entrance and framed the entire performance as serene and other-worldly. Serenity, à la The Castle, played into the performers’ Italian-holiday themed exploration of sitting postures lifted from courtroom drama, sporting matches and talk shows. ‘Marty’ and ‘Julie’ each assumed a sequence of seated stances as solos—individuals cohabiting the bench. Then the two swapped performances, lending new perspectives on the ways certain shapes are gendered and enculturated, changing the stories of these two solitary characters amid an imaginary, crowded grandstand. Props, including a fluoro orange esky filled with colourful drinks melded the performance with the park setting.

Perched on little stools, the audience grew. Kids scrambled in front of us to laze on the grass. Dogs too. Most of us were sitting in full sun on a 35 degree day, so we had great sympathy for the dancers who were glaring back at the sun in a “you won’t break us” stand-off. Long and Del Amo won and the sky opened up late afternoon Sunday, closing the third day of performances two hours early.

Those attendees who would complain about the elements complained about the elements. “First it was too hot, and then it rained.” Unless audiences adopt a Zen-like mindset and accept that impending rain and possible cancellation are part of the art—the fragility that makes an event like this special—disappointment is inevitable. The organisers had tried to provide shade and refreshments, knowing that walking between mini parks would tire some visitors. At Benched an array of fruit, Italian soft drinks and amaretto cookies were silver-plattered around after the half-hour performance.

I am an Island, Jess Olivieri with the Parachutes for Ladies, Micro Parks 2013, presented by Performance Space in Association with Sydney Festival 2013

photo Lucy Parakhina

I am an Island, Jess Olivieri with the Parachutes for Ladies, Micro Parks 2013, presented by Performance Space in Association with Sydney Festival 2013