Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Stephen Carleton

courtesy the writer

Stephen Carleton

Bio

I began writing (and reviewing) for the theatre during student days at La Trobe University, Melbourne and was part of a queer political theatre collective called Gudrun’s Stockings that did work at La Mama, Midsumma and elsewhere. I formed Knock-em-Down Theatre in Darwin in 1997 with Gail Evans (we have since been joined by Mary Anne Butler) and have been writing professionally for the stage in Queensland, the NT and indeed nationally ever since. Career highlights include winning the Patrick White Playwrights’ Award in 2005 for my play Constance Drinkwater and the Final Days of Somerset and the New York New Dramatists Fellowship in 2006. These days I am based in Brisbane where I am currently head of Drama at UQ and teach across our broad historical program. Areas of research in my writing for the stage, my critical reviewing and my scholarly work include cultural geography, Australian theatre studies, Gothic theatre studies and postcolonial theatre.

Exposé

I’m describing myself first and foremost as a cultural geographer these days. This is a result, perhaps, of growing up in regional Australia (Far North Queensland and Darwin), where there was absolutely no literature, theatre, visual art, film or TV on the school curriculum that depicted the part of the country that I grew up in. Ray Lawler’s cane fields and Nicolas Roeg’s screen outback were the closest I ever got to a recognisable Australia during my early education. I resolved at a relatively early age—as a teenager, I reckon—to be part of the solution and to dedicate myself to ‘mapping’ my North Australia through critical and creative praxis.

It’s a genuine passion and lifelong commitment for me to see North Australian creative and cultural content build and take its place in the national conversation, whether my role in that process be as playwright, theatre critic, academic researcher or dramaturg of other writers’ practice. I am deeply interested in writers and performance makers who interrogate the geographical and political context in which they are generating work. This connectivity with audiences, location and the polity at large seems so much more vital to me than solipsistic and esoteric self-reflection or the communication of nothing to no one. That potentially sounds like a mundane statement of the self-evident, but I guess what I’m saying is that my passion is for live performance that seeks out an audience for an intelligent, adult conversation about the world from which it has been germinated. I’m also happy for comedy, satire and wit to be part of that interrogation.

Recent articles

Mercenary or hero?

Stephen Carleton: QTC, Mother Courage and Her Children

RealTime issue #116 Aug-Sept 2013 p44

Embracing the world

Stephen Carleton: Brisbane Powerhouse, World Theatre Festival

RealTime issue #114 April-May 2013 p45

Staging the really virtual

Stephen Carleton: A Hoax, La Boite; Making The Green One Red, QUT

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 p30

Reviews of Stephen Carleton’s Constance Drinkwater and the Final Days of Somerset

Regenerative inversions

Douglas Leonard

RealTime issue #75 Oct-Nov 2006 p8

NT’s festive season

Suzanne Spunner, 2007 Darwin Festival

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 p6

Six artists, each in a room in the Grong Grong Motor Inn in the Riverina for a week in August, created works you can sample in a video about the project.

Video produced, edited and shot by Darrin Baker

You can also see more detail about works by

Scott Howie

Sarah McEwan

Darrin Baker

Waterwheel

Waterwheel Symposium Call for Participation

Waterwheel is an online platform for interdisciplinary discussions, performance and interaction around the subject of water (see our interview with founder Suzon Fuks). Waterwheel is currently calling for proposals from artists, scientists and thinkers to present artworks, performances and papers at the next symposium in March 2014 focusing on the theme “Water Views—Caring and Daring.” Proposals are also invited from young people (under 18 years) to take part in their Voice of the Future Youth Day.

Proposals for Symposium due 22 Nov; proposals for Voice of the Future Youth Day, 31 Dec; http://water-wheel.net/

Editor, Un Magazine

Un Projects, producer of the very neat and informative Melbourne-based art magazine, is seeking an editor for their two issues in 2014. Editions are published June & Nov and there is a fee of $3000 per edition.

Applications due 25 November 2013; http://unprojects.org.au/magazine/contribute/

Courthouse Arts Visual Arts Program

Courthouse Arts in Geelong is seeking expressions of interest from individuals or artist collectives aged 12-26 who are interested in curating the venue’s 2014 visual arts program.

EOIs due 15 Nov; http://courthouse.org.au/on-now/searching-for-a-young-curator-for-2014/

CCP Salon 2013

Now in its 21st year the CCP Salon (presented by Leica and Ilford ) is Austalia’s largest open-entry, photo-media exhibition and competition. There’s $20,000 in prize money up for grabs across 23 categories and the entry deadline has been extended.

Deadline 8 Nov; http://www.ccp.org.au/salon_2013.php

Still in the loop

AEAF—emerging + experimental curators

Applications due 8 Nov

www.eaf.org

Renew Sydney: Leichhardt

Proposals due 8 Nov

http://www.renewaustralia.org/2013/10/renew-australia-comes-to-sydney-with-renew-leichhardt/

First Draft Directors 2014-2015

Deadline 8 Nov

http://firstdraftgallery.com/get_involved/firstdraftwantsyou

Selected Australia Council Grant Deadlines

(for full list go to http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants

Music: Presentation and Promotion – 18 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/music-presentation-and-promotion-18-november

Music: New Work – Writing and Recording – 18 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/music-new-work-writing-and-recording-18-november

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander: Skills and Arts Development –

19 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-arts-skills-and-arts-development-19-november

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander: Presentation and Promotion-

19 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-arts-presentation-and-promotion-1-april

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander: The Dreaming Award –

19 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/dreaming-award

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander: Fellowships –

19 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-arts-fellowships

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander: The Red Ochre Award –

19 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/red-ochre-award

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander: New Work –

19 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-arts-new-work-19-november

Visual Arts Travel Fund – 25 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/Visual-Arts-Travel-Fund

Contemporary Music Touring Program – 25 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/contemporary-music-touring-program-25-november

RealTime issue #117 Oct-Nov 2013 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

![1) 7bit Hero; 2) Sha Sarwari, Asylum Seeker; Vidhi Shah and Jeniffer Heng, Flow[er]; 2high Festival](https://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/70/7091_2high.gif)

1) 7bit Hero; 2) Sha Sarwari, Asylum Seeker; Vidhi Shah and Jeniffer Heng, Flow[er]; 2high Festival

courtesy the artists

1) 7bit Hero; 2) Sha Sarwari, Asylum Seeker; Vidhi Shah and Jeniffer Heng, Flow[er]; 2high Festival

2high Festival, Brisbane Powerhouse

Curated by young and emerging producers under the watchful eye of Backbone Arts the 2high Festival is a one-day explosion of music, visual arts and performance that will take over the Brisbane Powerhouse complex. Highlights look to be the part pop concert, part video game experience of 7bit Hero (http://7bithero.com/) where the audience can use their phones as joysticks to participate in the game that plays behind the live band. Afghani refugee Sha Sarwari will exhibit his three-metre boat made entirely from newspapers and Vidhi Shah and Jeniffer Heng have created a flower from recycled electrical materials which blossoms in your presence. There are also back-to-back dance and theatre performances from emerging makers such as Matt O’Neill, Robert Millet, Dead Owl Factory, Courtney Scheu & Mariana Paraizo.

Backbone Arts: 2high Festival, Brisbane Powerhouse, 2 Nov, http://2highfestival.com.au/

Carnival of the Bold, Changemakers Festival

The Changemakers Festival is an umbrella structure (run by Social Innovation Xchange) linking a plethora of activities around Australia seeking social change and the building of better communities. One of these events, Carnival of the Bold at the New Theatre, Newtown, brings together “artists and other leaders who drive important issues of our time—to create deeper engagement around social causes” (website). The event will feature talks and performances by political satirist Simon Hunt aka Pauline Pantsdown, Indigenous artist and activist Adam Hill aka Blak Douglas, social change photographer Mikey Leung and children’s book author Melanie Lee in an evening hosted by that cultural chameleon Paul Capsis.

Changemakers Festival, national 1-10 Nov; http://changemakersfestival.org/; Carnival of the Bold, New Theatre, Newtown, 9 Nov; http://changemakersfestival.org/event/carnival-of-the-bold/

My Avant-Garde Is Bigger Than Yours, Kings ARI

courtesy the gallery

My Avant-Garde Is Bigger Than Yours, Kings ARI

My Avant-Garde Is Bigger Than Yours, Kings ARI

At the now decade-old Kings ARI, My Avant-Garde Is Bigger Than Yours, curated by Nik Papas, investigates humour, sarcasm, irony and parody using as a starting point Sigmund Freud’s Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious (1905). Delivering a barrel of art laughs will be Boe-Lin Bastian, Damiano Bertoli, Jessie Bullivant, Cheryl Conway, DAMP, Sue Dodd, Marco Fusinato, Tamsin Green, Raafat Ishak, Danius Kesminas, Yvette King, Lucas Maddock and Madé Spencer-Castle.

My Avant-Garde Is Bigger Than Yours, Kings ARI, 1-23 Nov 2013; http://www.kingsartistrun.com.au/

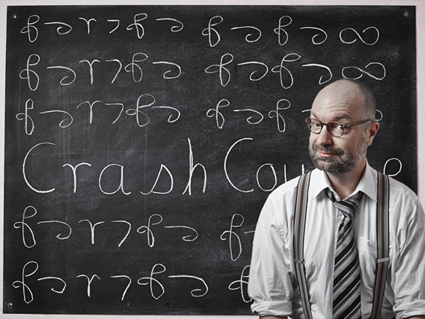

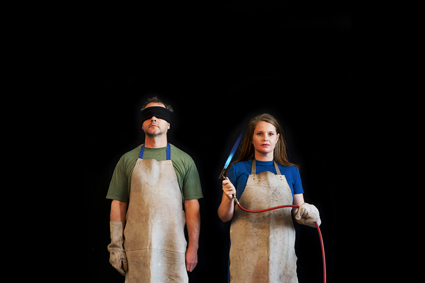

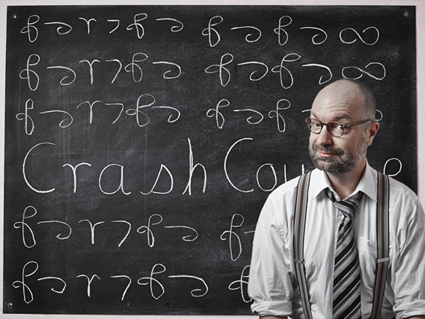

James Berlyn, Crash Course

Crash Course, James Berlyn

Following the success of last week’s Proximity Festival which he co-founded, James Berlyn is about to present his own intimate, participatory theatre piece (see the forthcoming review in RT118). Based on his experience as an English teacher and utilising his own fictional language, Winfein, Berlyn’s Crash Course takes 24 audience members on a performative language learning expedition.

Crash Course, creator/performer James Berlyn, director Nikki Heywood, producer Performing Lines WA, PICA, 14-30 Nov; http://www.pica.org.au/view/Crash+Course/1745/

![Asiga, [CTRL][P] Objects on Demand](https://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/70/7096_loop_object.jpg)

Asiga, [CTRL][P] Objects on Demand

courtesy of the Artist (COTA)

Asiga, [CTRL][P] Objects on Demand

[CTRL][P] Objects on Demand, Object Gallery

Once a near-future speculation, 3D printing is rapidly become part of our now. While we don’t yet all have our own personal 3D fabricator, it probably won’t be long. While you’re waiting for them to appear in Officeworks, you can pop into Object Gallery which, with the help of Courtesy the Artist (COTA), has been transformed into a 3D printing hub. Designers-in-residence Cinnamon Lee, Angus Deveson, Mitchell Bailey and Cesar Cueva will be creating objects, manufactured on demand, to be exhibited and sold in a pop-up shop. There will also be workshops where professional designers and the general public can try out the technology.

[CTRL][P] Objects on Demand, Object Gallery 15 Oct 2013 – 25 Jan 2014; http://www.object.com.au/exhibitions-events/entry/ctrl_p_objects_on_demand/; http://ctrlp.com.au/

Lorraine Heller-Nicholas, Love Story

Lorraine Heller-Nicholas, Love Story, Videobrasil

Melbourne-based animator Lorraine Heller-Nicholas is one of two Australian artists invited to exhibit as part of Videobrasil’s Southern Panoramas program (the other is Paris-based Bridget Walker). Heller-Nicholas’ 13-minute animation using ink drawing, with sound by Alice Hui-Sheng Chang, explores the cycle of love and heartbreak with a poignancy that comes from simplicity and repetition. You can view it and more of the artist’s work here.

Southern Panoramas, 6 Nov-2 Feb; http://site.videobrasil.org.br/festival/arquivo/festival/programa/1589140

Daniele Puppi, CINEMA RIANIMATO N.3, 2012, audio-visual installation, images from The Shout–a film by Jerzy Skolimowski

courtesy the artist and Magazzino Gallery, Rome

Daniele Puppi, CINEMA RIANIMATO N.3, 2012, audio-visual installation, images from The Shout–a film by Jerzy Skolimowski

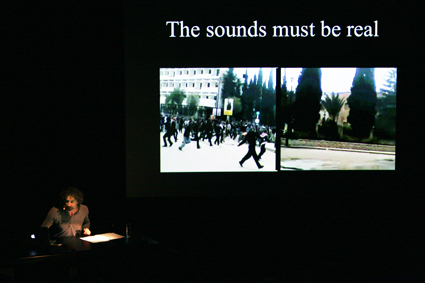

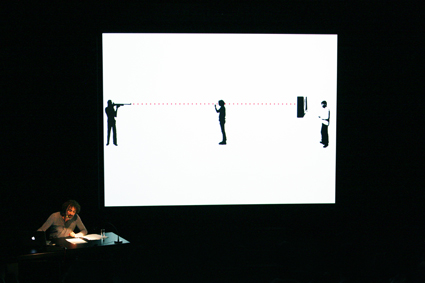

Daniele Puppi 432 Hertz, Cinema Rianimato e Dintorni, AEAF

Rome-based artist Daniele Puppi is currently in residence at Adelaide’s AEAF presenting his first major solo show in Australia. His large-scale audiovisual installations “envelop the viewer with their physicality and stage mundane, everyday actions as profound” (website). Information is hard to find on this elusive artist so we suggest attending his artist talk, Nov 1.

Daniele Puppi 432 Hertz, AEAF, 1 Nov-7 Dec; http://www.aeaf.org.au/exhibitions/danielepuppi.html

1) Voice, Maja Solveig Kjelstrup Ratkje, photo HC Gilje; 2) Yannis Kyriakides, The Buffer Zone, photo Peter Kiers; 3) Michaela Davies, Compositions for Involuntary Strings, courtesy the artist; Sonica 2013

Sonica, Glasgow

For those in the UK, the second installment of Sonica looks very impressive. Produced by Cryptic, the festival presents a weekend of “sonic art for the visually minded” (press release) including the UK premier of the audio-visual duet by Maja Solveig Kjelstrup Ratkje and light designer HC Gilje (Norway) and a multimedia opera by Yannis Kyriakides, The Buffer Zone, using field recordings from Cyprus of UN soldiers, nature and military technology combined with piano and cello. French artists Robin Meir and Ali Momeni will harness the mating behaviour of live mosquitoes in their interactive installation Truce: Strategies for Post-Apocalyptic Computation. Sonica also features an artist-in-residence and the curators seem to like Australians. Last year it was Robin Fox and this year it’s Michaela Davies who will be presenting her Compositions for Involuntary Orchestra. See our recent In Profile article for more.

Cryptic: Sonica, curators Cathie Boyd, Graham McKenzie and Patrick Dickie; 31 Oct-3 Nov; http://www.sonic-a.co.uk/

Still in the loop

Simple Forces, Joyce Hinterding

BreenSpace

25 Oct-23 Nov

http://www.breenspace.com/

Reinventing the Wheel: the Readymade Century

MUMA

3 Oct-14 Dec

http://www.monash.edu.au/muma/exhibitions/upcoming/readymade.html

The Double World, tranSTURM

Newington Armory, Sydney Olympic Park

19 Oct-10 Nov

http://www.sydneyolympicpark.com.au/whats_on/arts_and_culture_events/exhibition_the_double_world_spr13

http://cargocollective.com/transturm/the-double-world

Bogong ELECTRIC

Bogong Village, North East Victoria

1 Nov-1 Dec

http://bogongsound.com.au/

RealTime issue #117 Oct-Nov 2013 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Caroline Lee, A Kind of Fabulous Hatred

photo Daisy Noyes

Caroline Lee, A Kind of Fabulous Hatred

In staging Barry Dickins’ fantastical script about Sylvia Plath’s suicide, director Laurence Strangio, contracts the expansive 45 Downstairs warehouse space into an intimate pocket; one situated before a foreboding barred window. Imaginatively transposed to London, England, February 11, 1963, the audience is further seduced by an attention to detail that often characterises Strangio’s directorial efforts.

Mattea Davies’ design is a microcosm of Sylvia Plath’s mental duress: punitive order set amongst emotional chaos, and accentuated by a Shakespearean storm that, apparently, was the worst ever recorded at that time in England. Thankfully, centre-stage is not consistently occupied by a self-gratifying human presence; instead there is a gas oven inside which a luminous pilot light reminds the audience that this appliance is both heater and exterminator. Plath was arguably of Jewish descent and, as in history, her grasp on life is as tenuous as the arbitrary decision that underpinned the Holocaust. Sylvia Plath will die tonight: this will be the celebrated poet’s last night on earth.

But before Plath dies she targets with vituperative animosity those, and those things, that she believes have contributed to, if not caused, her incandescent unhappiness. Here, Dickins’ florid script enters remarkable territory. But not before Caroline Lee as Sylvia Plath hurls bolts of disdain at writing and poetry, poets and writers, the banality of motherhood, publishers, miserable London winters, her miserable self and, by extension, British poet laureate, academic and adulterous husband, Ted Hughes. Dickins’ phantasmagoria of Plath’s demise proffers a Jungian framework for understanding her predicament. Alone in her London flat while Hughes is apparently out porking one of his literature students, Plath’s absent husband becomes the dominant subject of a diatribe against her inability to reconcile a very personal hatred of her own masculine persona. Hughes is simply the transparent figure in the mirror, behind which lurks Sylvia Plath’s divided and irreconcilable self.

Caroline Lee, A Kind of Fabulous Hatred

photo Daisy Noyes

Caroline Lee, A Kind of Fabulous Hatred

Quite possibly, self-loathing kills more people than Jack the Dancer. Dickins understand this, and by concentrating Plath’s hatred for others upon herself, his decision to write an embellished, interior monologue, irrespective of the difficulties associated with performing such, is, in retrospect, both insightful and accurate. Form should reflect content.

But a difficult night in the theatre is one not easily justified. Sometimes, though, an audience should be prepared to sacrifice cosy entertainment for the demands of understanding the pathology of one of the 20th century’s more controversial poets and a prominent literary figure. Dickins, too, has made sacrifices. A Kind of Fabulous Hatred is a serious work from an Australian writer who is sometimes perceived as a nostalgic humourist. I don’t necessarily agree with this view. There is, I believe, more to Dickins’ writing than meets the ‘I.’ The usual Dickins’ idiosyncrasies are few here. A Kind of Fabulous Hatred is a provocative play that grapples with, and illuminates, clinical depression; a mental health condition that, for reasons prejudicial and economic, remains a lingering taboo in the 21st century.

A Kind of Fabulous Hatred, writer Barry Dickins, director Laurence Strangio, performer Caroline Lee, design Mattea Davies, lighting Bronwyn Pringle, sound Anita Hustas, 45 Downstairs, Melbourne, 12-22 Sept; http://www.fortyfivedownstairs.com/

RealTime issue #117 Oct-Nov 2013 pg. web

© Tony Reck; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Abandon, Opera Queensland & Dancenorth

photo Bottlebrush Studios

Abandon, Opera Queensland & Dancenorth

The very title, Abandon, suggests the necessity to forsake any expectation of a cohesive narrative in Opera Queensland and Dancenorth’s recent collaboration in Townsville. The sensual elements of music, song, movement, lighting, costume and set conspired to take the viewer somewhere ancient and otherworldly; to ply them with a sequence of potent, if inexplicable, experiences; to risk whatever response might be incurred by such an open offering. Few were unmoved. My companion was in tears.

Abandon, though it courts an internal, emotional storm in its absence of narrative structure, has a finely honed aesthetic nonetheless. Dancenorth artistic director Raewyn Hill’s trademark richness-by-understatement was further enhanced by the deceptive plainness of the box-walled set, papered floor and restrained lighting—all orderly at the outset. The exquisite Baroque symmetry of the score, comprising arias by George Frideric Händel, provided an ordered aural underpinning to the movement, even as it lifted and dropped the audience’s collective heart rate. Fleeting references to mythical scenes during Abandon were distilled from the characters of the operas Tolomeo, Alcina, Orlando and Hercules and the cantata Acis, Galatea e Polifemo.

Abandon, Opera Queensland & Dancenorth

photo Bottlebrush Studios

Abandon, Opera Queensland & Dancenorth

All of the cast, including the two musicians (classical accordion, cello) wore black and wine-coloured goth-clerical garments by Alistair Trung. Like other elements of this production, the apparent austerity later gave way to some unexpectedly lush transformations. The integration of dancers and singers in the first wall to wall dance movements, disturbing the paper floor and adding a layer of rushing sound, was testament to Hill’s choreographic range, in that the four (previously non-dancing) singers were initially indistinguishable from the five dancers.

The musicians also moved around the set, becoming involved in the action at various points, most notably when accordionist James Crabb faced off, stamping counter rhythms while continuously playing, against Bradley Chatfield’s belligerent pugilist. Chatfield’s angry, feisty boxer, trying to corrall the rest of the cast, provided a comic contrast to Alice Hinde’s earlier heartrending solo; France Herve’s remarkable partnering with her own cascade of hair, as if it were another dancer; Erynne Mulholland’s fearful and imperious ten foot tall harpy; and Andrew Searle forcing the female cast into gaps which appeared in the box walls, as though playing a human Tetrus game.

Abandon, Opera Queensland & Dancenorth

photo Bottlebrush Studios

Abandon, Opera Queensland & Dancenorth

The creators’ own description of Abandon notes that, “Unlike most baroque operas which travel from chaos to order, our trajectory seems to travel in the opposite direction.” Indeed, the emotional extremes were reflected in the gradual disintegration of the physical set, as high apertures and low drains opened up in the walls; the paper was flung, piled in corners, used for burial and dispersed again; and costumes were undone, let out, ballooned, removed and reassumed.

The lighting supported the changing sense of internal and external space perfectly, sometimes replicating the dramatic chiaroscuro of a Flemish painting in rare moments of relative physical and musical repose.

A journey sometimes defies explication, cannot always be recounted sequentially or logically, especially when much of it involves ephemeral sensations rapidly displacing one another, and intense connections made and lost. As if to emphasise this, in the final moments the walls are dismantled and rebuilt downstage to separate cast from audience, and we are abandoned to make of it what we will.

Abandon will be performed at the Brisbane Powerhouse, 21-23 February, 2014

Opera Queensland & Dancenorth, Abandon, co creators James Crabb, Raewyn Hill, Lindy Hume, music director James Crab, design Bruce McKinven, lighting Bosco Shaw, costumes Alistair Trung, School of Arts Theatre, Townsville, 24 July-1 Aug

RealTime issue #117 Oct-Nov 2013 pg. web

© Bernadette Ashley; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Prick up your ears for this in the loop which offers a burst of sonic happenings across the country, plus some dance and theatre to balance the mix.

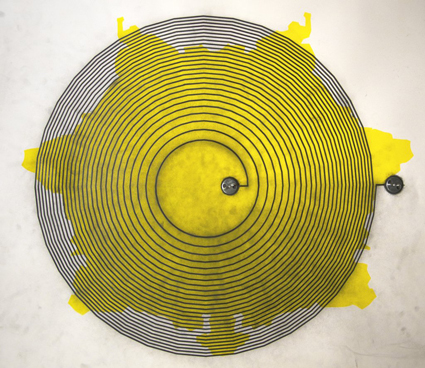

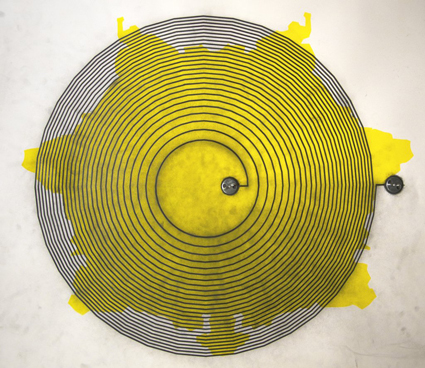

Joyce Hinterding, Fields and loops: series 4, 2010, ink and graphite on paper

courtesy the artist and BreenSpace

Joyce Hinterding, Fields and loops: series 4, 2010, ink and graphite on paper

Simple Forces, Joyce Hinterding, BreenSpace

Marrying “deep science” and elegant aesthetics, Joyce Hinterding’s upcoming solo exhibition at BreenSpace, Simple Forces, seeks to transform “matter into ideas, and ideas into matter” (website). Using forms and symbols drawn from algorithmic structures, the graphite shapes also create circuits which, when amplified, make invisible atmospheric forces audible.

Joyce Hinterding, Simple Forces, BreenSpace, 25 Oct-23 Nov; http://www.breenspace.com/

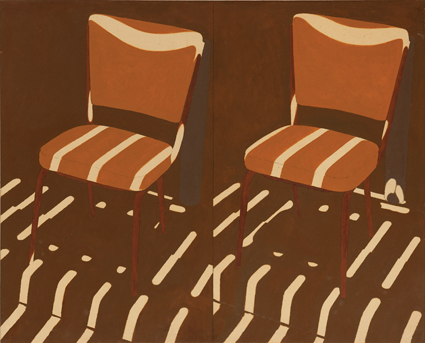

Reinventing the Wheel: The Readymade Century – Julian Dashper, ‘Untitled (The warriors)’ 1998

Reinventing the Wheel: the Readymade Century, MUMA

Now showing at MUMA, Reinventing the Wheel celebrates Marcel Duchamp’s liberating declaration that the any object, in the right context, can become art. It follows the momentum of this idea through the 20th century and into the 21st, featuring the work of over 50 artists ranging from international historic figures, including Carl Andre, Andy Warhol and Gilbert & George, to Australian contemporary artists John Nixon, Ricky Swallow, James Lynch, Agatha Gothe-Snape and others. Accompanying the exhibition, a series of music events, Found Sound, explores John Cage’s celebration of the aural readymade. The final installment (Oct 26) will feature Joyce Hinterding and Lawrence English.

Reinventing the Wheel: the Readymade Century, MUMA, 3 Oct-14 Dec; http://www.monash.edu.au/muma/exhibitions/upcoming/readymade.html

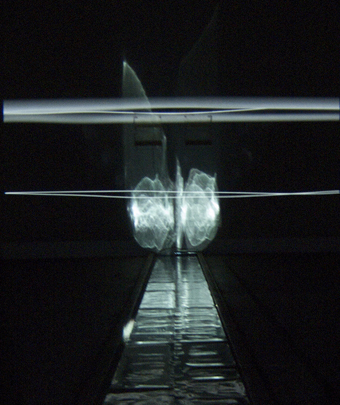

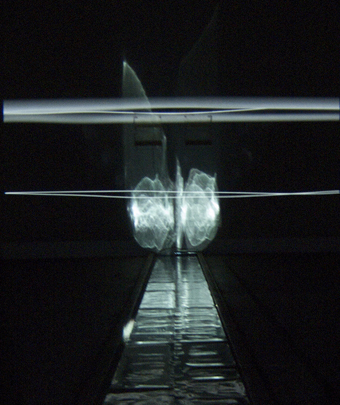

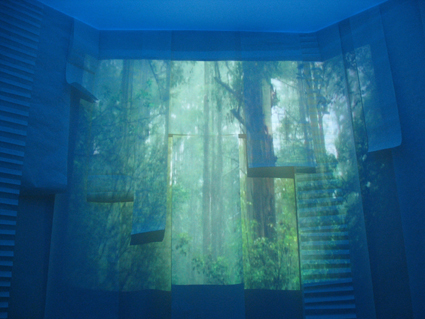

Chamber 1 (Order), Chris Bowman, Michael Day, Rachael Priddel, Colin Black, The Double World, transTURM collective

courtesy the artists

Chamber 1 (Order), Chris Bowman, Michael Day, Rachael Priddel, Colin Black, The Double World, transTURM collective

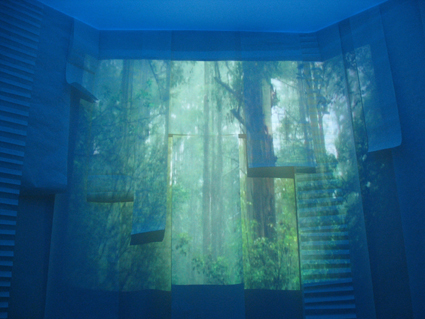

The Double World, tranSTURM, Newington Armory

Taking over one of the cavernous spaces of the Armory at Olympic Park, the UTS-supported tranSTURM collective has created a “double world” of light, sound and animation. Drawing inspiration from Rainer Maria Rilke’s poetic exploration of the Orpheus myth the installation has been created by a collective of Australian and international designers, architects and media artists under the creative directorship of Chris Bowman. The installation also features a soundtrack by Colin Black and choreography (displayed as mapped video) by Meryl Tankard.

The Double World, tranSTURM, Newington Armory, Sydney Olympic Park, 19 Oct-10 Nov; http://www.sydneyolympicpark.com.au/whats_on/arts_and_culture_events/exhibition_the_double_world_spr13; http://cargocollective.com/transturm/the-double-world

Christophe Charles, Bogong ELECTRIC

Bogong ELECTRIC

Following the success of the Bogong AIR festival in 2011 (see review), Philip Samartzis and Madelynne Cornish have been establishing a permanent home for sonic exploration in the village of Bogong in the north-eastern alps of Victoria. Now settled in the restored schoolhouse, the Bogong Centre for Sound Culture (BCSC) will soon present Bogong ELECTRIC, a month of performance and installations using the Kiewa Hydroelectric scheme as the starting point for investigations around natural and built environments. Guest artists include Michael Vorfeld (Germany) using the inherent noises of electric devices like light bulbs and switches to produce audio performances; Christophe Charles (Tokyo) creating an underwater soundscape to be listened to while on the lake; Geoff Robinson (Melbourne) transposing a sonic map from one area to another; and David Burrows (Melbourne) experimenting with stereographic imaging. The BCSC will also be offering a range of educational opportunities and registrations are now open for a masterclass with Samartzis in Feb 2014.

Bogong ELECTRIC, Bogong Village, North East Victoria; 1 Nov-1 Dec; http://bogongsound.com.au/

AAO & Wagilak songmen, Crossing Roper Bar

Crossing Roper Bar, AAO

RT Managing editors Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter were lucky enough to see an early manifestation of Crossing Roper Bar at the Darwin Festival in 2008 (see review). This unique collaboration between the Australian Art Orchestra and the Wagilak songmen from Ngukurr in East Arnhem Land has continued to evolve, now featuring Broome singer/songwriter Stephen Pigram (replacing the late Ruby Hunter). This very special concert has been touring West Australia and there are few shows left to catch in Karatha, Exmouth and Perth.

Tura New Music & Australian Art Orchestra: Crossing Roper Bar, AAOO with the Wagilak songmen and Stephen Pigram; Karratha, 25 Oct, Exmouth, 27 Oct, Perth, 29 Oct: http://crbtour13.tura.com.au

Dance Makers Collective, Carl Sciberras, Anya Mckee, Leeke Griffin, Marnie Palomares, Katina Olsen, Miranda Wheen, Sophia Ndaba, Jenni Large, Rosslyn Wythes, Matt Cornell

photo Anya Mckee & Dance Makers Collective

Dance Makers Collective, Carl Sciberras, Anya Mckee, Leeke Griffin, Marnie Palomares, Katina Olsen, Miranda Wheen, Sophia Ndaba, Jenni Large, Rosslyn Wythes, Matt Cornell

Big Dance in Small Chunks, Form Dance Projects

This premier performance for the Dance Makers Collective brings together 10 emerging dancers and choreographers to collaborate with each other as well as filmmakers, musicians, visual artists and designers (including Erth Visual and Physical Theatre) to present nine ambitious new pieces. We’re particularly curious about the performance described by Miranda Wheen (connecting Eddie Obeid with his pelvis) in her recent RT Profile.

Form Dance Projects: Big Dance in Small Chunks, Dance Makers Collective (Matt Cornell, Jenni Large, Anya Mckee, Sophia Ndaba, Melanie Palomares, Katina Olsen, Marnie Palomares, Carl Sciberras, Miranda Wheen and Rosslyn Wythes); Lennox Theatre, Riverside 23 – 26 Oct; http://form.org.au/2013/01/dance-makers-collective/

Sons & Mothers, No Strings Attached Theatre of Disability

courtesy the company

Sons & Mothers, No Strings Attached Theatre of Disability

Sons and Mothers, No Strings Attached Theatre of Disability

Following its highly successful premier season at the Adelaide Fringe in 2012 No Strings Attached’s production Sons & Mothers is currently enjoying a full season at the Space Theatre. The group-devised work presents the stories of six men with disabilities and their relationship with their mothers. A feature documentary on the process of developing the show has also just screened as part of the Adelaide Film Festival. See the review of both film and stage production in RT118.

Adelaide Festival Centre and Windmill Theatre: Sons and Mothers, No Strings Attached Theatre of Disability, writer, devisor and director Alirio Zavarce, with and for the Men’s Ensemble of No Strings Attached; Space Theatre, Adelaide Festival Centre; 17-26 Oct; http://www.nostringsattached.org.au/sons-and-mothers-2013.html

RealTime issue #117 Oct-Nov 2013 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jim Daly, John Gabriel Borkman

If the road to perdition is paved with treacherous ice then a pathway into director, Peter King's scathing interpretation of Henrik Ibsen's John Gabriel Borkman sometimes glitters with gold.

As if electrified, male performer Cory Corbett as Borkman’s maniacal wife Gunhild rips away a sheet from 'her' body and the play begins. Upstairs, pacing back and forth for the last decade or so, resides the disgraced title character of this play, John Gabriel Borkman: estranged husband of Gunhild, former lover of her twin sister Ella, hated father of his son Erhart and, above all, a man guilty of embezzlement who has not only destroyed his family's reputation but after spending time in jail, has quietly gone mad in response to a self-imposed exile from what he, Borkman, perceives as a cruel and heartless world. Ibsen's script immediately ensnares its audience in a penultimate endgame. It remains to be seen just who will survive this winter's night, one comprising loneliness and deception, alienation and hatred, insanity and mortifying despair.

King's direction utilises expressionist acting techniques rarely seen in Australian theatre. Jim Daly as Borkman and Russell Walsh as his emotionally deformed acolyte, Vilhelm Fodal, extract from King's direction much humour (some cartoon inspired) and a wistful evocation of the emotional wilderness that characterises most, if not all, the characters in this play. As Borkman is persuaded by his sister-in-law and former lover, Ella, to descend the stairwell of his self-imposed cell and challenge his psychotic wife Gunhild for custody of Erhart, the audience becomes witness to a remarkable display of physical endurance, technical concentration and ensemble acting.

During a four act performance without interval, extending across 100 minutes, the actors form themselves into grotesque physical images, spit out Ibsen's caustic familial vision with cobra-like accuracy and ultimately give expression to the playwright's view of a Christian theology that rages against the dying of its own light. Outside, the universe is cold and uninviting. Borkman's eventual death is not an ascent to heaven but instead, a descent into a symbolic mire. He will die in the snow with a “metal hand” wrenching life from his breast and, perhaps for the first time, God is pronounced dead in a theological wilderness suspended above a bottomless fjord, one carved from granite and ice rather than wrought from any supercilious religious force.

Mounting this production has been director Peter King's obsession, perhaps for some time. His directorial strategies are metaphorical and often abstract. But it remains clear that King himself is precise when considering how he interprets Ibsen's confrontation with the divine, and how he wishes to express this interpretation. That said, and within a bubble-wrapped set designed by Peter Corrigan and succinctly lit by Greg Carroll, the protective walls we erect in our delusional lives are no match for the seething hatreds that drive the thanatological personality. Unrestrained, it will drive each of us into that which Thanatos most desires—an abyss void of God and organised religion, one characterised by secular annihilation and the interminable passing of time.

John Gabriel Borkman, writer Henrik Ibsen, translation Peter Archer, director Peter King, performers Jim Daly, Cory Corbett, Ezuk Doruk, Will Freeman, Russell Walsh, designer Peter Corrigan, lighting Greg Carroll, La Mama, Melbourne, 18-29 Sept

See also Jana Perkovic's account of a 12hour version of John Gabriel Borkman at Theatretreffen, Berlin, 2012

RealTime issue #117 Oct-Nov 2013 pg. web

© Tony Reck; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Benjamin Ducroz, cumulo, installation

photos Eugenia Lim

Benjamin Ducroz, cumulo, installation

For an ‘inaugural’ artist-led festival based around a relatively young art form, the Channels video art festival was weighty: a packed four-day program including close to 100 artists, curators and speakers; a level of curatorial and critical engagement that significantly amplified the impact of the work itself; and not least, a substantial printed catalogue that ably focused ideas, themes and relationships across the program.

Encompassing gallery-based installation, projections, online broadcast, a voluminous screening program and public talks, Channels’ central question was, say co-directors Rachel Feery, Eugenia Lim and Jessie Scott, “What is video art now?” Sounds simple, even simplistic—but one of the many impressive things about Channels was its genuine consideration of the question: its showcasing of contemporary video work with reference to the history of the form and a conscious engagement with the ubiquitous ‘now’ of mass-media video immersion.

Ms&Mr, Amputee of the Neurotic Future 1988/2012, installation

photo Eugenia Lim

Ms&Mr, Amputee of the Neurotic Future 1988/2012, installation

Installed

Transformer, at Screen Space, was the exhibition for Channels, featuring works commissioned from Ms&Mr (aka Australian-Canadian duo Stephanie and Richard nova Milne) and Melbourne-based Benjamin Ducroz. In Ducroz’ cumulo, piles of roiling Pilbara storm clouds dissolve into the incremental movements of a hand-cranked, helical kinetic sculpture. Both phenomena are filmed in stop motion, in the landscape; but while the sped-up movement of the clouds is familiar thanks to its TV-doco ubiquity, the brightly coloured sculpture, stark in the middle of the desert, is surreal, seeming almost to be superimposed. Shifting between romanticism and deconstructivism, cumulo is projected onto a tall, trapezoidal screen at the gallery entrance accompanied by a soundtrack of ambient, insecty, subtle, sometimes ominous tones. The sublime vision of clouds—creamy, silver-lined or darkly grey—prefigured the misty pines and crumbling glaciers of some of the more meditative works in Channels’ Video Visions screening program. At the same time, the stepped structure and block colours of the moving model insist on time’s breakdown into increments, dancing with the origins of time-based photography. If it weren’t for Ducroz’ process work in the nearby foyer, where the sculpture is seen ‘on set’ in the desert, the quasi-scientific, twirling helix could easily be read as a 3D animation. In a sense, romantic ‘truth’ meets disbelief in cumulo.

A warping, monotonal drone is the backdrop for Ms&Mr’s three-channel work, Amputee of the Neurotic Future 1988/2012, part of their ongoing Videodromes for the Alone series. A distressed and silently howling prepubescent boy is protagonist in a fractured world of film and 3D animation, surrounded by symbolic props—a crashed and sinking car, a hospital gown apparently animated from within, a CAD-drawn checkered floor, an uncannily defocused bunch of flowers. With references to both J G Ballard and David Cronenberg, the mood is dystopian, painful and alienated, but washed out by blood-red monochrome into a kind of emotionless absence: an escape from horrifying realities that itself becomes horrifying.

Screened

The main screening program, Video Visions, provided an astonishingly broad survey of current video art from Australian and international artists over two intensive sessions on one night. Loosely themed into four sections—Sensory Drive, Media Mash-Ups, Constructed Worlds and Bodies Collide—Video Visions included dozens of short works; the choice to include an interval in each session created just the right breathing space.

There’s not enough room here to describe the breadth of works in the Video Visions program but some overall themes were evidenced, both in the overarching session titles and more subtly. The Media Mash-Ups and Bodies Collide sessions were the most tightly focused and, interestingly, the most reliant on humour, as though both the onslaught of mass culture and our visceral, physical reality can only be confronted with a grimace or an outright laugh. Sensory Drive crossed from virtuosic, psychedelic experiments with CGI ‘super-natures’ to formalistic explorations of colour, line or natural phenomena. Narrative seemed to emerge most strongly in Constructed Worlds, as though a ‘world’—even a fictitious or abstract one most requires a story. Noticeably weaving throughout the program were frequent evocations of mysticism and suggestions of what seemed like ‘earth-nostalgia:’ conflations of human/nature; eerie, hollow and ominous soundtracks; and the sense of worlds lost.

Emile Zile, Random Name Generator Memorial Roll Call, Memory Screens

photo Danielle Hakim

Emile Zile, Random Name Generator Memorial Roll Call, Memory Screens

Performed

The intersection between video and performance art, past and present, was the inspired starting point for the Memory Screens program in which artists Salote Tawale, Hannah Raisin and Emile Zile each presented newly commissioned works paying homage to selected iconic works by video and performance “elders.” As well as live performances of the three new works, excerpts were screened both from the artists’ previous output and from the chosen ‘source’ works.

Emile Zile, whose work to date humorously interrogates and replays conventions and tropes of cinema, television and the web, chose as inspiration Ant Farm’s 1975 Media Burn in which a Cadillac smashes through a pile of burning TV sets. In the most oblique response of the three artists, his new performance (via Skype), Random Name Generator Memorial Roll Call, comprised a tongue-in-cheek, funerary video roll call of randomly generated, unborn internet users, accompanied by vases of white lilies.

Hannah Raisin, Dear Carolee, Love Cindy, Love Hannah, Memory Screens

photo Danielle Hakim

Hannah Raisin, Dear Carolee, Love Cindy, Love Hannah, Memory Screens

Hannah Raisin, responding to Carolee Schneeman’s Interior Scroll, chose Cyndi Lauper’s “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun” as soundtrack to her absurd and confronting consumption of raw eggs injected with coloured dyes. Echoing Schneeman, whose 1975 performance consisted of extracting a long scroll from her vagina, in Dear Carolee, Love Cindy, Love Hannah, Raisin provided the music via an audio cable drawn from her vagina (presumably attached to an inserted MP3 player) and plugged into a stage monitor. The effect blurred feminist statement and monstrous-feminine, hinted at porn and vigorously challenged the gaze.

Salote Tawale, Dressing Up, Memory Screens

photo Danielle Hakim

Salote Tawale, Dressing Up, Memory Screens

Most directly referential was Salote Tawale’s response to Susan Mogul’s 1973 video, Dressing Up. As she slowly gets dressed, Mogul delivers a monologue on the clothes her mother made her wear as a child while periodically stuffing her mouth with snack food. Tawale recreated Dressing Up, delivering her own story of childhood female oppression, inextricably woven with the threads of her Pacific Islander heritage. It was a powerful end to a session that exemplified the strengths of Channels overall: its engagement across a broad thematic range, critical depth through discussion, and the commissioning of new work; and the imaginative contextualising of contemporary practice through the lens of history.

Channels: The Australian Video Art Festival, various venues, Melbourne, 18–21 Sept; http://www.channelsfestival.net.au/

This article first appeared in RT’s online e-dition 23 Oct, 2013

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. web

© Urszula Dawkins; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

B l o o m—S p a c e, (Installation view) 2013.

Background Roy Ananda; middle ground Carla Liesch; foreground Will French; curated by Adelé Sliuzas

photo Alex Lofting

B l o o m—S p a c e, (Installation view) 2013.

Background Roy Ananda; middle ground Carla Liesch; foreground Will French; curated by Adelé Sliuzas

AEAF—emerging + experimental curators

The Adelaide-based Australian Experimental Art Foundation is calling for proposals from emerging curators to present exhibitions in the second half of 2014. (Read our review of emerging curator Adelé Sliuzas’ bloom, a highly successful exhibition as part of the 2013 series.)

Applications due 8 Nov; www.eaf.org

Renew Sydney: Leichhardt

Colluding with Leichhardt Council in Sydney’s inner west, The Renew Australia team are happy to announce the launch of the first Sydney Renew program. This will see a number of unoccupied retail properties become available for creative commercial and artistic enterprises. They are currently seeking people interested in setting up small creative retail spaces.

Proposals due 8 Nov; http://www.renewaustralia.org/2013/10/renew-australia-comes-to-sydney-with-renew-leichhardt/

107 Projects Applications for 2014

You’ve just enough time to put in an application for the 2014 gallery program at the pumping artist-run space 107 Projects in Redfern. Exhibitions can range from one week to three with just about all artforms welcome.

Applications due 25 Oct; http://www.107projects.org/

First Draft Directors 2014-2015

One of Australia’s oldest artist-run initiatives, First Draft in Sydney is looking for people passionate about the emerging arts and with skills in collaborative arts management to join the team of directors for the next two years.

Deadline 8 Nov; http://firstdraftgallery.com/get_involved/firstdraftwantsyou

Selected Australia Council Grant Deadlines

(for full list go to http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants

Music: Presentation and Promotion – 18 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/music-presentation-and-promotion-18-november

Music: New Work – Writing and Recording – 18 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/music-new-work-writing-and-recording-18-november

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander: Skills and Arts Development –

19 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-arts-skills-and-arts-development-19-november

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander: Presentation and Promotion-

19 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-arts-presentation-and-promotion-1-april

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander: The Dreaming Award –

19 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/dreaming-award

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander: Fellowships –

19 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-arts-fellowships

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander: The Red Ochre Award –

19 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/red-ochre-award

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander: New Work –

19 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-arts-new-work-19-november

Visual Arts Travel Fund – 25 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/Visual-Arts-Travel-Fund

Contemporary Music Touring Program – 25 November 2013

http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/grants/2013/contemporary-music-touring-program-25-november

RealTime issue #117 Oct-Nov 2013 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Video footage: Sam James, Editing: Gail Priest

* * *

Coleambally is just over 600kms south west of Sydney in the Riverina region. It’s a very young town, founded in 1968 and currently has a population of just over 600 residents. One third of them attended A Night of Wonder, at the Coleambally SunRice Mill.

Vic McEwan from the Cad Factory in Narrandera brokered a unique partnership with the SunRice corporation to have access to their mill site in Coleambally and their workers (on company time) in order to develop an evening of site specific performance and installation. Only just re-opened after drought closure in 2007, the vast factory complex incorporates facilities managed by Australian Grain Storage. Following the path that rice processing takes, A Night of Wonder led its audience to 10 sites in the mill and storage facilities,

Site 9 – Opera, A Night of Wonder, Coleambally SunRice Mill, The Cad Factory

photo Mayu Kanamori

Site 9 – Opera, A Night of Wonder, Coleambally SunRice Mill, The Cad Factory

McEwan invited artists Mayu Kanamori (Sydney) and Shigeaki Iwai (Tokyo) to collaborate with each other and the Coleambally community. McEwan and Kanamori undertook a one-week residency early in the year, at the beginning of harvest time. Subsequently they were joined by Iwai for a three week residency in Spring: planting time. The Japanese artists brought with them a very different relationship to rice from our own. Theirs is an ancient connection associated with tradition and ritual, while, as McEwan suggest in the realtime tv documentary on A Night of Wonder, in Australia rice is just rice. Of course for the community of Coleambally rice has become much more than that.

The main performance in the cavernous storage barn saw several community members—a local Aboriginal elder, a farmer, a farmer’s wife, a miller, the factory manager—have a conversation with ‘rice,’ each speaking at a microphone to a circular projection of falling rice grains. For Stan Grant, the Wiradjuri elder, it’s a conflicted relationship: rice is not native to the area, but now it helps support his people. To the farmer it’s a co-dependent relationship; to a farmer’s wife it’s one of sharing her husband with the crop he loves. The final performer is Kanamori, speaking as a bird (complete with avian headdress) about how rice fits into birds lives. (Coleambally is an Aboriginal word describing a swift in flight.) As the projected image mutates into rice fields being burnt back for a new planting, a curtain of actual rice showers down, the metaphors of fire and water and earth co-mingling. McEwan, accompanying the performance with sound produced on laptop, also plays clarinet and miked-up fixtures of the building. Placed in the centre of the journey, the performance allowed the roving audience to settle and contemplate, though the ritualistic and reverent tone felt, at times, a little too ponderous.

Site 3 – Ceremony for Planting, A Night of Wonder, Coleambally SunRice Mill, The Cad Factory

photo Mayu Kanamori

Site 3 – Ceremony for Planting, A Night of Wonder, Coleambally SunRice Mill, The Cad Factory

Ritual had been introduced with a lighter touch earlier on in the evening at the third site—a large stack of semi-circular airing baskets. Audience members were invited to ignite tea-light candles, place them in the baskets and make wishes for the new planting season. The resulting installation of hundreds of delicate flickering lights amid worn metal machinery was simply magical.

Site 5 – Of Rice & Men, A Night of Wonder, Coleambally SunRice Mill, The Cad Factory

photo Mayu Kanamori

Site 5 – Of Rice & Men, A Night of Wonder, Coleambally SunRice Mill, The Cad Factory

Shigeaki Iwai declared he was liberated by the absence of deep cultural significance in Australia around rice, his main artwork embracing instead a sense of play. In site five, an alleyway between two large warehouses, he installed a series of knee-high figures—people and animals made entirely of molded rice. These were placed in relation to old pieces of machinery illuminated with ultraviolet light. Not only did this provide a spectral glow to the figures, casting the audience’s hi-viz orange vests in terrifying contrast, but it also drew attention to the role of ultraviolet light in the rice growing process and, perhaps, the detrimental effect of too much of it given the potential for a greater hole in the ozone layer.

Mayu Kanamori got to the heart of the matter creating an installation about love. When they first arrived in Coleambally the artists held a dinner party, treating a number of community members to a 10-course rice banquet. After some sake tasting, Kanamori convinced the diners to write short poems about rice and love. These stories formed the basis of an installation featuring Kanamori’s photographs, audio recordings and small handwritten texts displayed amidst piles of golden rice husks, forming both a visual, sonic and tactile environment.

Site 4 – Rice Bran Facial, A Night of Wonder, Coleambally SunRice Mill, The Cad Factory

photo Mayu Kanamori

Site 4 – Rice Bran Facial, A Night of Wonder, Coleambally SunRice Mill, The Cad Factory

Industrial sites just beg for large-scale projections and A Night of Wonder did not disappoint. Onto three large grain storage silos a projected video showed several hardened millworkers in close-up being given facials made from rice bran, a traditional Japanese beauty therapy. Their faces loomed two storeys tall while we listened to recordings of their wives discussing how beautiful the refreshed skin felt, and how it had really made the men gentler and more relaxed. The workers themselves admitted that it was not too bad an activity, and as one wife says, she feels it has made her husband just that little bit more metrosexual.

The event culminated with a mini opera performed by a Narrandera local Fiona Caldarevic. Composed by McEwan, the lyrics were taken directly from interviews with workers in the mill about their daily routines. Caldarevic appeared as a diminutive figure on a landing protruding from the vast façade of the building onto which were projected scenes of pounding machinery (and wobbling jelly, the significance of which escaped me). Reminiscent of 70s British workers’ theatre it provided a suitably dramatic ending.

Interspersed among the art activities were several refreshment stations serving very tasty sushi rolls and hearty rice soup and everyone received a show bag of SunRice products. It was clear that the overall warm vibe at the conclusion of the evening came from much more than this generosity. A Night of Wonder managed to strike a perfect balance of engagement with its community. The ways in which the audience participated—being weighed in as if they were a rice crop, lighting candles, shuffling through rice husks—were subtle, non-confrontational, but meaningful. Perhaps more importantly, the ways in which community members were engaged were well pitched to be satisfying for them but also also fed into artistic outcomes. For a project juggling creative, community and, of course, business expectations, it really was wondrous.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, STC

photo Heidrun Löhr

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, STC

The slipperiness of identity, whether a matter of clinging to or searching for it is a commonplace in fiction and theatre, let alone in real life where it keeps many a being from a sense of wholeness. Three productions in Sydney have addressed this: the STC’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead in which the duo’s quest for being in a world that refuses to properly identify them is dressed with a scarily surreal aura; Back to Back Theatre’s Super Discount which puts to the test a ‘disabled’ man’s identification with a super hero and its ramifications for his friends; and Moogahlin Performing Arts’ This Fella My Memory, in which three women struggle to re-achieve their sense of connection with family and country.

STC, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead

With Escher-like perceptual playfulness, Gabriela Tylesova’s design (with enabling lighting by Nick Schlieper) for the STC’s production of Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (1967) could have come straight out of a Polish theatre production of the 60s. Stark cloister arches on the sides of the stage angle in without meeting, yielding an ominous upstage void. The spaces immediately behind the arches at first appear to have depth but are later blackly forbidding, constituting a symbolic barrier for the play’s trapped protagonists, already confused and ineffectual victims of pure, or let’s say theatrical, contingency. If that weren’t enough, a large inverted, abstracted tree hangs above the pair, like a cipher from Beckett’s Waiting for Godot rendered by a Polish modernist.

Of course, the play is a riff on Waiting for Godot in which, instead of a landscape empty save for a tree, we have the world of Shakespeare’s Hamlet experienced as if from the sidelines by two of its doomed minor characters. The air of calculated Mittel European surrealism in the design is amplified by the pair’s naïve and increasingly desperate philosophising as well as in the costumes and grotesque demeanour of the hyperbolic figures they encounter—the actors on their cart like a circus crew from a Bergman film and Gertrude (an unrecognisable Heather Mitchell) an explosively exasperated wordless take on Elizabeth I.

Although perpetually panicked, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern themselves appear relatively normal: a couple of tolerably well-dressed gentlemen. Toby Schmitz’s intellectually posturing Guildenstern prances about, underlining thought bubbles with idiosyncratic gestures. Tim Minchin’s Rosencrantz, less alert than Guildenstern, but capable of his own flashes of illogical brilliance, hesitates and darts, stays close to the ground as the pair fill the waiting with ridiculous but sometimes alarmingly meaningful speculation. This tightly teamed, flawless duo is superb, as is Ewen Leslie’s ebullient leader of the actors.

An aura of pathos forms as the play ends, two likeable innocents, despite all their naïve attempts at understanding their condition, surrender to the ultimate blackness threatened throughout by the stage design of the provisional world they inhabit and the inadequacies of language—“words, they’re all we have to go on.”

Mark Deans, Simon Laherty and Brian Tilley, Super Discount, Back to Back Theatre

photo Jeff Busby

Mark Deans, Simon Laherty and Brian Tilley, Super Discount, Back to Back Theatre

Back to Back Theatre, Super Discount

Like Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, Back to Back Theatre’s Super Discount (for Sydney Theatre Company and Malthouse) is another gripping account of existential angst within a theatrical framework. This time a group of performers with intellectual disabilities in a rehearsal room decide to perform a work about the superheroes beloved by one of their number, Mark Deans. However, believing that he’s not capable of playing a super hero, they instead audition each other and a cocky ‘able’ actor (David Woods), squabble (some very funny, quick-witted exchanges between Brian Tilley and the others), tear into patronising audiences and slip into superhero costumes. But then they falter as the inauthenticity of the process dawns on the director, Simon Laherty. He suspects Mark should be playing the superhero. The outcome is funny, spectacular (lighting Andrew Livingston) and telling—that sometimes simple solutions are best.

The ambiguities constellating around persons with disabilities being represented as superheroes, save it seems for top-ranking sports people, are many. Back to Back avoids any easy affirmation of the underrated capacities of the ‘disabled.’ Instead they face the complexities—degrees of ability, prejudices among the ‘disabled’ themselves and the theatrical demands of casting—that have made the creation of a work, initially as a tribute to Mark, so troublesome.

Another complicating factor is the presence of the ‘able’ actor, disgruntled because disadvantaged in not having a disability—he’s never praised by audiences. Not surprisingly, he is cast by his fellows as the bad superhero. His angst is best displayed by Woods in dialogue, less well when it becomes a monologue leaving the other performers inert and the momentum of an otherwise brisk production stilled.

The audition routines, debates, role playing (Laherty in a wig as a super hero’s girlfriend), super hero dancing (Woods and Tilley choreographed by Antony Hamilton), Scott Price’s obstreperous interventions, nice touches like Sarah Mainwaring’s battle to mount a microphone on a stand, witty scripting and a strong focus on trust—will the group do the right thing by Mark?—all add up, delivering a satisfyingly complex and richly entertaining experience.

Moogahlin Performing Arts, This Fella My Memory

A large cloth screen, timber walkways and an open space to the front of the stage facilitate the presentation of various encounters and locations, urban and rural, and a very active spirit world in This Fella My Memory. The writing, the plot and characterisations are straightforward, but the actors deliver nuanced performances that suggest more complex personalities. Vast projections of night skies, rippling water and glittering traffic flows in a distant city amplify a sense of people in narrow circumstances looking for bigger lives.

Dolly (Lily Shearer)—a middle-aged Indigenous alcoholic who is hit by a car and loses her place in a hostel for homeless women—fears she is dying and yearns to visit her country. A grumpy cousin, Toots (Elaine Crombie), begrudgingly agrees to take her, but has to be coerced to also deal with Colleen (Linden Wilkinson), a white woman friend in the hostel who doubtless gave Dolly the grog that got her into trouble. While tension on the road between Colleen and an unforgiving Toots (who meanwhile indulges in a fantasy of returning to a singing career she ruined) doesn’t let up, Dolly begins to improve, if haunted by the ghosts of two girls from her country’s past.

From here on the plot grows more complicated as the unwelcome trio encounter Toots and Dolly’s relatives, enabling the play to take in issues of juvenile crime, rape and murder (hence the presence of the two ghost girls), return to ceremony and a young middle class woman’s discovery that she is Aboriginal. As well, Colleen reveals her past and its Indigenous connection and Toots finally acknowledges that she has no singing contract. It’s almost too much, veering into soap opera territory as crises mount and are too easily resolved, but director Frederick Copperwaite’s careful pacing and the intensity of the playing compensate somewhat for misgivings. Certainly the collectively composed writing, which oscillates between sharply observed and pedestrian, could be improved should the play have another life.

As “the first Aboriginal theatre production created, developed and produced by an Aboriginal company in Redfern in almost 40 years” (press release), This Fella My Memory is a welcome indication of the potential of Moogahlin Performing Arts to bring new perspectives on Australian life to the stage, in this case with a focus on the challenges for disadvantaged middle-aged women to recover their sense of agency and identity.

Sydney Theatre Company, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, writer Tom Stoppard, director Simon Phillips, Sydney Theatre, 28 Aug-14 Sept; STC, Malthouse, Back to Back Theatre, Super Discount, director, devisor with the performers Bruce Gladwin, Wharf 1, 20 Sept-19 Oct; Moogahlin Performing Arts, This Fella My Memory, director Frederick Copperwaite, created & devised by Moogahlin Performing Arts & Linden Wilkinson, Carriageworks, Sydney, 4-7 Sept

RealTime issue #117 Oct-Nov 2013 pg. 34

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Brian Fuata, Privilege (House), Temporary Democracies

photo Heidrun Löhr

Brian Fuata, Privilege (House), Temporary Democracies

Can a neighbourhood sausage sizzle qualify as art? What about a table tennis competition in a local clubhouse? When it comes to socially engaged community art projects, it can often be near impossible to demarcate the boundary between ‘art’ and ‘life’. This is certainly true of the works that make up Temporary Democracies, a series of site-specific art and performance installations located in the South Western Sydney suburb of Airds.

Currently home to thousands of individuals and families who rely on public housing, 70% of Airds will be redeveloped over the next 15 to 20 years with a large proportion of its population to be relocated elsewhere. Demolition is already underway, leaving vacant a number of houses and empty blocks of land. For Temporary Democracies, an initiative of Campbelltown Arts Centre supported by the NSW Land and Housing Corporation, curator Paul Gazzola has invited 13 artists to develop projects over the next two years that engage with the urban conditions of the area and reflect on the changes affecting this community. The first instalment this year saw a handful of Australian artists consulting and interacting with local residents as they developed works onsite over five days in August, using vacant homes and empty land as inspiration for their installations.

The scene I encounter on a bright Saturday afternoon initially feels more like a friendly neighbourhood street party than a contemporary art project. A small crowd is milling around a food trailer, chatting casually, hotdogs in hand. This is artist Robert Guth’s Mobile Cooking Hearth, a van that has been constructed by Guth together with members of the Airds/Bradbury Men’s Shed group using the remains of kitchens from demolished houses.

Cooking as art has been done before—most famously by Rirkrit Tiravanija who offered gallery visitors homemade curry and pad thai meals at his New York shows during the 1990s. But Guth has taken the extra step of moving out of a gallery setting and placing his work directly onto the street by creating a mobile cooking facility that will remain a permanent part of the Airds community. If sharing food is the ultimate communal act, Guth’s project shifts the meaning of art from aesthetic to social. It may appear decidedly lo-tech and anti-aesthetic, but as the afternoon wears on and my new friends and I pass around the tray of freshly baked lemon cookies that the artist has produced from the trailer’s oven, I experience firsthand the potential of this project to foster human relationships.

Tanya Schultz, Dreamers who seek treasure, Temporary Democracies

photo Heidrun Löhr

Tanya Schultz, Dreamers who seek treasure, Temporary Democracies

Across the street, Elizabeth Woods has transformed the interior of a newly vacated house into a table tennis drop-in centre which she has called The Academy—What’s Your Game? It’s decorated with trophies and memorabilia, including photographic portraits of smiling Airds residents, and Woods is on hand to keep score for children playing enthusiastically. Meanwhile, the property next door has had its walls covered floor to ceiling by Tanya Schultz’s Dreamers who seek treasure, a multicolour wallpaper collage created using photographs of items that have been donated, lent and constructed by residents. Schultz tells me she set up an art and craft table in the Airds village shopping centre and that her wallpaper features images of the objects made by children who stopped by, as well as photographs of neighbourhood pets including Phil’s budgie and Pumpkin the dog who lives next door. It is unashamedly kitsch and playful, and the burst of colour it brings is eerily juxtaposed with the stillness of the empty house that we know will soon be torn down.

Brian Fuata’s Privilege (House) is the most artistically ambitious project of the bunch. The artist sits outside on a rectangular concrete slab that has been laid on a vacant block of land. His program notes state that he aims to “sonically reconstruct a recently demolished house.” His voice is projected from four speakers that face out towards the benches on which we are invited to sit around him. At one point he recites strings of seemingly random letters, before reading definitions of words that appear to be related to themes of place and location. His lone presence and echoing voice create a compelling visual and sonic image that feels somewhat like a poetic rendering of a Rachel Whiteread work: whereas the UK artist’s concrete casts make physically present the interiors of negative spaces we do not usually see, Fuata evokes a now-absent physical structure through abstract and ephemeral sounds.

Complementing these installations is Rebecca Conroy’s artist blog which can be accessed at www.temporarydemocracies.com. As more material is added online in the months ahead, it looks to be a useful resource in framing the onsite events within a wider social, political and artistic context. By creating collaborative art with a community in transition, the legacy of Temporary Democracies may well persist far into the future.

–

Read “Live art from demolition,” an interview with Paul Gazzola and CAC director Michael Dagostino about Temporary Democracies in RT116.

Campbelltown Arts Centre, Temporary Democracies, curator Paul Gazzola, Heathfield Place, Airds, 13-17 Aug; www.temporarydemocracies.com

RealTime issue #117 Oct-Nov 2013 pg. 32

© Ilana Cohn; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

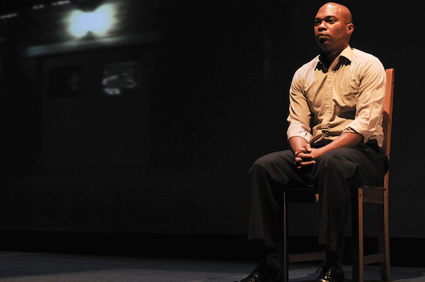

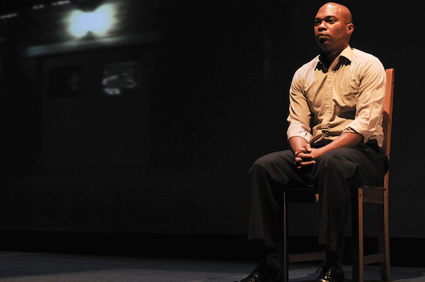

Irving Gregory, The Disappearances Project

photo Heidrun Löhr

Irving Gregory, The Disappearances Project

After several years of ‘emergence,’ version 1.0 erupted into prominence at Performance Space in 2001 with The second Last Supper featuring a mix of the not-so ‘old guard’ from the contemporary performance community and the new, along with nightly consumption throughout the season of an enormous volume of red wine in an outrageously surreal, promiscuously wide-ranging taboo-busting epic.

Moving resolutely on to tackle political issues still largely unaddressed by Australian theatre, version 1.0 has rarely lost that sense of fun, even when tackling the darkest of subjects. Material taken from public and parliamentary records about the Children Overboard saga (CMI, A Certain Maritime Incident, 2004), Government media manipulation about the Iraq War (The Wages of Spin, 2005), Australian Wheat Board corruption in Iraq (Deeply Offensive and Utterly Untrue, 2007) and local government corruption (The Table of Knowledge, 2011-12) has been ironically reframed, physically, vocally, spatially and technologically, without resorting to satire or mimicry.

These works are still enormously relevant. Version 1.0 has also tackled masculine violence, the suffering of people whose relatives have disappeared—in The Disappearances Project—and “place, tourism and atrocity” in Kym Vercoe’s seven kilometres north-east (which has become a film, Jasmila Zbanic’s For Those Who Can Tell No Tales, featured in the 2013 Toronto Film Festival), and a history of the maltreatment of the people of Palm Island, Beautiful One Day, produced as a collaboration with Ilbijerri Theatre. For Canberra 100 the company recently created the much praised The Major Minor Party, about the ACT-based Australian Sex Party and its impact on Australian political culture.

Hot on the heels of The Major Minor Party comes The Vehicle Failed to Stop. In 2007, a 49-year-old taxi-driver Marou Awanis and her friend Jeneva Jalal were shot by private security contractors working for the Australian-owned company Unity Resources Group, “an integrated risk mitigation solutions provider for clients in complex, challenging and fragile environments, globally headquartered in Dubai.” Apparently the car got too close to a security vehicle albeit in a safe part of Baghdad. Coming after similar deaths, the killings resulted in widespread protest. The Iraqi Government attempted to ban the American security firm Blackwater from the country. A legal team working on behalf of the women’s families filed a suit in Washington. However, the American Government claimed to bear no responsibility for overseeing outsourced security operations, therefore the families have had to sue URG. RT spoke with Irving Gregory, a current member of version 1.0, about himself as a performer and the issues focused on in The Vehicle Failed to Stop.

Tell us a little bit about your background as a performer.

Basically I came out of New York University’s Experimental Theatre Wing in the Tisch School of the Arts undergraduate drama program. Very lucky there to have worked with people like Anne Bogart among other people in the mid-80s before she came up with her Viewpoints concept. I worked the downtown dance and performance scene in New York in the 80s. Then I travelled to Germany, worked in the free scene in Munich and other cities. Travelled around there. Came back to the States in the 90s, tried to do movies for a while and got back into theatre in the late 90s when I joined the Collective Unconscious in New York.

While at the Collective Unconscious—which we ran as a collective and put shows on there to pay the rent basically—we developed a performance called Charlie Victor Romeo which won two Drama Desk Awards, travelled all over the US, was co-produced in Japan, came here to the Perth International Arts Festival, was filmed by the Air Force for training, picked up by the medical community…It had a long and storied history and was made into a film last year, which premiered at Sundance Film Festival this year.

The text is the transcripts of six actual airline emergencies—black box transcripts which we dramatised, live onstage with an award-winning sound design. In 2004 Time magazine named it as one of the best plays of the year. I’m in the film and also credited as one of the screenwriters as I’m one of the creators of the play.

What drew you to Australia?

Well, I got married. I met my wife in Perth when I was here in 2002. We stayed in touch and got married in 2008. I then talked to people at version 1.0. They got back to me in 2011 for The Disappearances Project. That’s when I joined the company.

What’s the attraction of working with version 1.0?

Well it’s always the people and the work. From Charlie Victor Romeo, I had an interest in this type of theatre—theatre documentary style and/or verbatim style. I’d done elements of that kind of work since the late 80s actually. I did a piece with [performer, dancer, painter] Fred Holland, basically as a sound operator. He had an interview in the piece, which was about the fight career of Jack Johnson, the great boxer, and the interview with him was about when he had to surrender the title—because the Feds were going to prosecute him under the Mann Act [a law against ‘white slavery’ but used to criminalise consensual sexual behaviour between blacks and whites. EDs]. I worked with this piece to re-integrate it a bit more and discovered the power of an interview—real words—and how that can work dramatically. I worked subsequently in Germany with an interview-based piece called Packing and Shipping. Learning version 1.0 did that kind of work I became interested in them. The Disappearances Project was the first work I did with the company and The Major Minor Party, which we premiered in June, is the second.

The Vehicle Failed to Stop, is predicated on a terrible incident in Iraq, when two women were killed by security contractors.

The initial development at the Sydney Theatre Company in 2012 was by David Williams, Kym Vercoe and Jane Phegan. I worked on the development of the idea in March of this year. In working with verbatim and/or interview and/or transcriptional sources there’s a lot of editing that has to be done, a lot of focus on what is important and what needs to be conveyed. What we brought out in this latest development was not only the fact that extra-judicial killing had occurred in an environment where a lot of this kind of thing had taken place through the use of contractors, but a focus on the whole nature of privatisation. And this extended to the entire administration of Iraq during and after the invasion. Paul Bremer [Administrator of the Coalition Provisional Authority of Iraq after the 2003 invasion], through one of his notorious orders, basically opened up the country to exploitation by any and all private industry because that was a part of the strategy.

Based on the neo-liberal assumption that this would solve everything.

Exactly, but then you have it taken to the extreme, being imposed upon an entire country at one time. It’s about the broadest sort of utilisation of that economic theory possible. You invade a country, you knock out the government, you fire everyone and you just say, ‘well, it’s open season for any and all entrepreneurial ideas to come in here internationally with no accountability to anyone.’ What are the consequences of this? One we found directly related to the incident with the two women is that you have a lot of security people on the roads operating beyond anyone’s law with the only consequence of their actions that they may be fired and sent out of the country. There’s no jurisdiction.

What kind of verbatim material are you using?

Documents derived from books and articles about Erik Prince, the head of Blackwater Security Consulting, and about the case itself as it was attempted to be adjudicated in the US and abroad. Then there are the pronouncements of and articles about the Bremer administration and also transcribed documentary footage about other elements of the privatisation and the experience of private contractors in Iraq. Another thing is that these companies—Halliburton, Kellogg Brown & Root, Blackwater, which reaped billions of dollars in profits, out of this wide-open, almost Wild West, boomtown environment—were not necessarily protective of their employees. They just send them to a country that has been supposedly ‘secured’ and what happens is people who aren’t security contractors, but truck drivers, are killed. Because the companies want to maximise profits, because they have a bottom line to meet, these men find themselves being shot at in gasoline trucks. What is that?

One of the companies involved is the ex-military Australian-owned URG.

Yes, they were the contractors involved in the incident with the two women being killed. In Afghanistan right now there are more contractors than troops. People may not know that. Of course, when the troops leave next year there’ll be opportunities for private contractors to continue security and other sorts of missions there. So this is a new element of international relations—how governments deal with international crisis points. Because when you don’t have to use your national army, when you can use private companies, then you’re not really accountable to anyone.

It goes nicely in tandem with the roboticisation of war in the form of drones and so on.

Well, it’s the 21st century we’re looking at. This is the way things are going, the way that war is now being prosecuted, or small wars—that’s all we have any more, isn’t it?—a changing environment in modern conflict, an environment without accountability or responsibility.

Carriageworks, version 1.0, The Vehicle Failed to Stop, Carriageworks, Sydney, 15-26 Oct

RealTime issue #117 Oct-Nov 2013 pg. 35

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

(lr) Danielle Baynes, Nicole Dimitriadis, Kate Englefield, Tough Beauty

photo Claudia Chidiac