Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

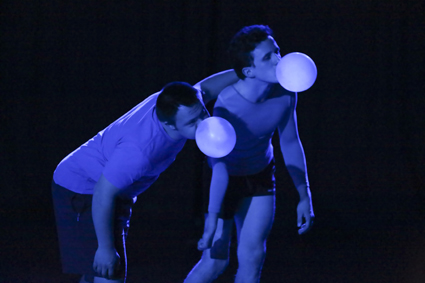

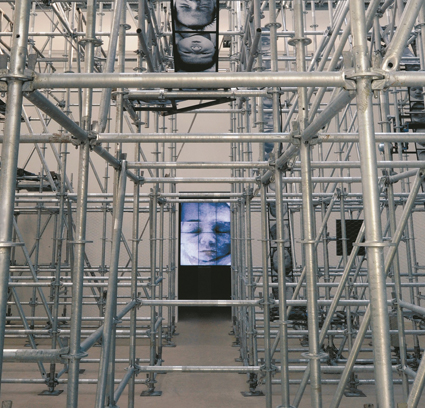

Felicity Tchorlian, Ragnarök /or how it ended/, Shopfront

photo Howard Matthew

Felicity Tchorlian, Ragnarök /or how it ended/, Shopfront

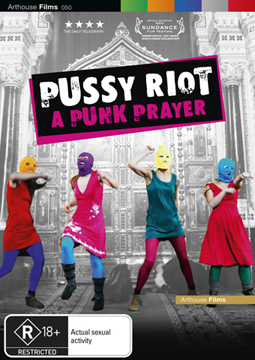

It’s a busy time for performance and live art, but the curatorial prospect of Civic Life is straightforward: give over the sprawling, boxy property that contains Shopfront Theatre to artists who’ve been hanging out, making work and maybe just thinking in the space for the last six months. It’s a residency program that seems to balance open-ended time and space to work with a specific exhibition outcome, and the results are as uneven and energetic as you’d expect from a bunch of mentored artists and writers under 25, riddling their way through the early stages of their creative careers.

This instalment of Civic Life, A Walk in the Dark, encompassed works-in-progress that were not complete packages but first steps towards something else. The most interesting part of Sarah Aghazarmian’s The Dark Net was not its subject matter—the internet’s illicit shadow economy—nor its form (one assumes it will be a traditionally-staged theatrical work), but the fact that audiences got the opportunity to see a read-through of an unfinished script. Perhaps the best way to discuss process is not to make works about it but to take an open and un-precious approach and let audiences look in on different stages of a work’s development.

From this traditional theatrical beginning, the rest of Shopfront’s residency program crossed from visual arts to performance fluidly and without regard for barriers. Into Orbit, by duo N&V (Nicola Frew & Verity Mackey), read more like an art gallery show, comprising six (not 13) rooms containing live bodily sculptures, video and installation invoking and obsessing over sensorial experience—like the massive sub-woofers that produced sound at low vibrations to be felt rather than heard. Chris Dunstan’s Erase related to what could be the other art world theme of the day, the subjective and malleable nature of memory, with the emphasis on performance, repetition and duration. Three performers, including the artist, practised the act of memorising, which is also the act of forgetting—as evidenced by a pianist’s inevitably failed effort to learn by heart a new piece of music in just 25 minutes. As with Into Orbit, these were rigorous, exploratory exercises that are pleasing to engage with cerebrally but perhaps less so experientially.

It was the pieces with a more orthodox audience-performer relationship that offered the most to delve into. Diverging from theory-informed interventions, Carly Young’s reworking of the classic French tale The Little Prince presented an honest story that maximised the different spaces inside Shopfront. Starting in the theatre, the catwalk and lighting rig were simply transformed into our narrator the Pilot’s aircraft, slowly whooshing just above us and just below the ceiling. The Pilot then told us, “Follow the Little Prince,” and we did—through the theatre, onto the street and all around. The production was in turns sweet, funny, childlike and everything you want from a well-loved text with such a fierce, humane intelligence. Yes, it was a spare and small-scale production, and traipsing around a rabbit warren might seem strange to some, but I felt we were being taken care of—we were with the Little Prince on his journey. Young showed that traditional stage plays can use space innovatively—taking us outside the black box.

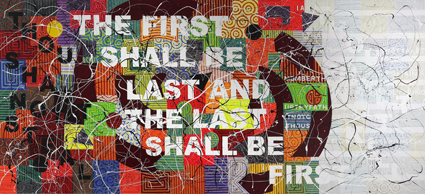

Emma McManus usually makes work with the self-described “small but likeable” theatre group Applespiel. Her Ragnarök /or how it ended/, is an exciting stab at highly visual performance that places less emphasis on story and dialogue and more on a meaningful collection of striking images and moods. This kind of non-narrative communication is tough, and the piece is not fully complete, but mostly, Ragnarök hung together. The title refers to a godly doomsday story in Norse mythology; in McManus’s piece it inspires contemporary reflection on unspecified collective panic about life, the universe and everything. We seemed to be witnessing a real-time video clip about our age’s apocalyptic leanings. A lone, wailing electric guitar, looming shadows, lashings of gold glitter, tealight candles and white flour poured and projected through the air via a fan all contributed to a luxe yet sparse aesthetic that really did summon an end-of-days feeling. Without overdosing on dark-night-of-the-soul melodrama, Ragnarök could be something you feel before a heart attack, and I eagerly await the finished piece. It had the spirit of lo-fi celebration that exemplifies the best of Civic Life, of rough-and-ready artist-led experimentation.

Shopfront Theatre, Civic Life—A Walk in the Dark, Carlton, Sydney, 6-10 Nov

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 40

© Lauren Carroll Harris; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Despite burgeoning interdisciplinarity and crossovers, the line between art and the creative industries over recent decades remains firmly etched in the cultural psyche. In our Art, Wellness & Death feature in RealTime 117, we profiled artists Efterpi Soropos and George Poonkhin Khut who are developing commercial applications of their creations to aid the dying and those in pain, without surrendering their sense of being artists. I have friends who would be labelled ‘creatives’ in the commercial world whose inventiveness surpasses that of many an artist but who bemoan their lack of artistic freedom given the narrow ambit of commercial design and other practices in Australia.

George Hedon, an art director for a Melbourne advertising agency, co-founded Pause Fest with Filip Nakic four years ago with a passion to “create a collective digital community,” bringing together creatives who might normally not mingle, let alone collaborate, from a wide range of industries engaged with digital technologies: “advertising, digital design, animation, production and post-production, as well as incubators and start-up communities.” I recently spoke with Hedon about the festival and its ambitions.

Hedon, who had no experience of running a festival, has grown the event by encouraging the generosity of speakers, pro bono support, in-kind donors and volunteers (some 30-60 per festival), such is the enthusiasm for the event. The response from the field has been strong, the scale of the festival grows and the City of Melbourne has proved financial support for the 2014 Pause Fest.

Pause Fest takes creatives outside their usual parameters, offering pause: time-out to meet, think and potentially collaborate. This year’s festival theme is “connections,” between individuals and industries. Hedon believes that the event has generated “a collective digital community” via “a non-profit event in which any income is put into the festival’s future.”

In our discussion there’s occasional telling slippage in terminology. When I ask Hedon how important it is for creatives to escape the boundaries of their professions, he answers, “It’s the most important thing: to be able to express yourself, in your artform, to explore your ideas and then apply yourself to a commercial world.” Do all the outcomes have to be commercial? “Everything ends up being commercial,” he replies. But it’s individual creativity and identity that counts: “You have to have your own signature before you go into the commercial.” Which is where Pause Fest offers succour. However, Hedon admits, “we’re sitting on a fence of what is commercial and what is art. We’re really pushing [the] art and technology [connection].”

It’s not surprising then that Hedon is particularly pleased with the festival’s interactive installations program. Ten works were short-listed and two chosen for realisation.

Three of the works are Australian, one is Polish. The brief was to create installations that would “engage a wide audience: adults, kids, families, the elderly.”

A key part of the Pause Fest program from inception is animation: the first encouraged collaborations between animators and sound designers around the world. Overseas makers, who mostly work in post-production and other areas of commercial production, are grateful for access to Pause Fest’s animation program, although Australians, says Hedon, are less eager, but are catching up. A very broad theme is set for the animators to apply to an otherwise “blank canvas.” Last year the theme was “the future,” which resulted in “some very dark work. It’s a happy theme this year.” The works will be screened at ACMI, on Federation Square’s big screen and online.

Pause Fest has an extensive program of talks and forums to which has been added for the first time an intriguingly titled event, PanicRoom. Hedon explains it’s the creation of PostPanic, a post-production company in Amsterdam founded by its Creative Director Mischa Rozema, a keynote speaker at this year’s festival. PanicRoom gatherings, explains Hedon, “are not about making speeches or talking about the work. They are interested in everything else: what creative people like, what their influences are, their experiences, their favourite music—who they are and what makes them tick.” PanicRoom will feature Australian creatives, revealing dimensions that feed their creativity in a four-day Pause Fest that will buy them some liberating time-out.

2014 Pause Fest, ACMI and Federation Square, Melbourne, 13-16 Feb, www.pausefest.com.au

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 26

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Joanne Mott, Grounded, 2013, native grasses, sedges and rushes, Palimpsest

photo John Power

Joanne Mott, Grounded, 2013, native grasses, sedges and rushes, Palimpsest

“Palimpsest means a parchment that has been partly erased and re-inscribed. It evokes the marks made by human settlement on the land, the passage of time, presence and absence and the web of inter-dependence uniting the natural and the cultural, the material and the immaterial.”

www.artsmildura.com.au/Palimpsest

The “Biennale of the Bush,” as Palimpsest is sometimes known, is huge, both in terms of the number of artists participating and the sheer geographic scale of the event. Since its inception in 1998, the environment has been a recurring theme in Palimpsest. Outdoor works featured prominently this year, some hearkening back to the Mildura Sculpture Triennials of the 1970s—among the first events in Australia to move out of the gallery and situate artworks in the natural environment. This link was particularly notable in Joanne Mott’s living installation, Grounded, located in the very same park (a reclaimed rubbish dump) that housed the outdoor artworks of the Sculpture Triennials.

Mott’s creation has sustainability at its core. It uses living, Australian native, anti-erosion grasses planted to spell out GROUNDED, reflecting various interpretations of the word, including the very soil in which the grasses are planted and the concept of being psychologically earthed. This work is a continuation of Mott’s practice of planting and her conceptual interest in what she describes as the “heterogeneity of ‘nature’ and ‘culture’,” which are united in her artworks (www.joannemott.com). In Grounded, the health of river systems is reflected in the proximity of the artwork to the river and her use of soil erosion grasses that prevent riverbanks from being washed away. Clearly hand-planted, Grounded emphasises human presence, encouraging consideration of the efforts people make to repairing the environment.

Danielle Hobbs, 7000 eucalypts, 2013, mixed media installation, Palimpsest

photos Kristian Häggblom

Danielle Hobbs, 7000 eucalypts, 2013, mixed media installation, Palimpsest

Danielle Hobbs’ 7,000 Eucalypts comprised a gallery-based sculpture and a large site-specific artwork, drawing on the symbolism of a famous work by German artist Joseph Beuys: 7,000 Oaks. Completed by Beuys and the townsfolk of Kassel for Documenta 8 in 1987, it bore a message that related to both environmental remediation and urban renewal. This resonated with Hobbs, who reworked Beuys’ idea into an artwork that also had personal resonances for her. On a property managed by her father, the artist reframes a forest of hundreds of Australian gums from plantation trees into both an artwork and an environmental statement. Each tree was spray-painted with a pink dot, like those that councils use to indicate a tree destined for removal. The trees in 7,000 Eucalypts reflect new thinking about sustainable logging, but are also, says Hobbs, a reminder of the thousands of old-growth forests being cut down every day (Artist Talk, 5 October).

Hobbs has maintained a sense of environmental responsibility since her youth and admits to being a vocal critic on the subject, even within her own family. Thus, her father’s movement into sustainable logging makes the work personal. From the perspective of an observer kept behind safety fences, I found the number of trees marked for felling moving—representing a metaphorical and very real barrier between humans and the environment given the ongoing demand for wood-based products. The number of forests that are logged is alarming though there was some relief in knowing that these trees were not old growth.

Hobbs’ gallery-based work was featured in the ADFA building, recently refurbished as an art gallery, having formally housed the Australian Dried Fruits Association and fallen into disrepair. Hobbs describes her work as “art as an ecological intervention,” drawing on environmentalist themes and presenting them as art. The sculpture in ADFA draws on the same imagery as in the plantation, but we are instead presented with sawn logs. Stretching between plantation and gallery, 7000 Eucalypts offered passive yet powerful imagery, linking iconic Australian trees, and therefore the greater Australian environment, with the global one by referencing Beuys’ 7,000 Oaks. A sense of the presence and absence in trees growing and logged, was consistent with the Palimpsest theme.

Also using the outdoors and gallery space to engage with the environment, David Burrows drew on the landscape of Mildura’s Lake Ranfurly, an artificial stormwater basin covering almost 200 hectares. My first impression of the ‘lake’ was of a large open span of sand, devoid of water, invoking concerns about water security in Australia. In this ‘lake,’ Burrows presented Mirage Project ….[salt], a reinterpretation of his Mirage Project ….[iceberg] presented in 2012 in Melbourne’s Federation Square. This project utilises stereoscopic 3D photographs of icebergs taken by Burrows in Antarctica and seen, on the lake, through mounted binocular slide viewers. These works were carefully positioned so that the viewer could see the icebergs from the same positions that the original photographs were taken. These images of beautiful, naturally formed ice sculptures contrasted sharply with the arid lake. As you see the three-dimensional detail of the icebergs, your body feels the dry heat and baked sand, generating a sense of the very real potential of global warming to transform one landscape into the other. Burrows’ companion work, Crepuscule was featured at Mildura’s Wallflower Photomedia Gallery presenting beautiful photographs of the slowly changing effects of light on Lake Ranfurly.

Juan Ford’s Lord of the Canopy at the Mildura Arts Centre, embodied the nocturnal ambience of nature in a darkened gallery lit with spotlights casting ominous shadows on the walls. A large tree on the gallery floor comprised several segments, visibly bolted together into what Ford describes as a ‘frankentree’ (Artist Talk, 6 October). A highly polished possum ring (sheet-metal designed to prevent animals from climbing trees) was positioned on the trunk to reflect a large, circular painting of the warped image of a possum on the gallery wall, establishing a dialogue between the natural denizens of the Australian night and the human hand on the environment. Walking through Lord of the Canopy, I felt the need for quiet and slow movement as one might when encountering a possum at night in your backyard. Yet that feeling of wonder was overshadowed by the ‘wrongness’ of this bolted-together, artificial tree and the denial of the possums’ natural home represented by the ring.

These works, just a few of the many created by the 49 artists in this year’s Palimpsest, demonstrated not only a developing subgenre of Australian art concerned with the environment, but also a wider consciousness of the natural environment and a gradual inscription and re-inscription of the environment. While I’ve focused on works with direct environmental concerns, other artists created works with subtler tones of environmentalism and a diverse array of other themes including surveillance, mental health, blended cultures and the changing face of Mildura. Palimpsest is a powerful event reflecting many current concerns through the lens of contemporary art.

Arts Mildura, Mildura Palimpsest Biennale #9, curator Helen Vivian, assistants Geoffrey Brown, Rachel Kendrigan, Rohan Morris, various venues in and around Mildura, 4-7 Oct, www.artsmildura.com.au/palimpsest/

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 28

© Jane Wildy; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

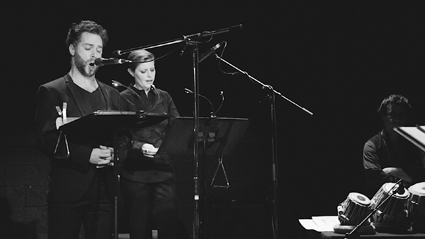

Alana Everett, Lauren Langlois, Rennie McDougall, Lily Paskas, Lee Serle, A Small Prometheus

photo Jodie Hutchinson

Alana Everett, Lauren Langlois, Rennie McDougall, Lily Paskas, Lee Serle, A Small Prometheus

The beginnings of a dance work, or any project for that matter, may be happenstance. A match is struck: the spark of an idea flashes, catches, gently glimmers and grows. Eighteen months later, five dark figures cluster around three metal sculptures, methodically lighting a circle of candles. The heat created by their combined candlepower causes a circular propeller to spin, gently pinging and sounding as it revolves. This is an altar to the power and beauty of fire, a ritualistic beginning, which transforms heat into movement.

Kinaesthetically, much the same happens. Bodies roll, push, pull, crawl, arch and twist into sitting and standing. Five dancers line up along a diagonal; runners at the starting line. There is a kind of pause, an in-breath before the dancing begins. The work is poised before its own future. We know that A Small Prometheus is about fire but, given this is not a narrative, how does the idea of fire meld into movement? Stephanie Lake’s treatment of her topic merges with the musical input of her collaborative partner, Robin Fox. Billed as a joint creative venture, we find the music playing an equal, sometimes dominant, role in the work. Mostly this enhances the quality of the dancing but sometimes eclipses it. While all dance to music needs to determine its relation to the music, the nature of this collaboration raised the status of the sound. If the music takes the lead, the challenge is to take up its stimulus without surrendering to it, to make the sum greater than its parts.

A Small Prometheus consists of a series of responses to its theme. It offers a kinaesthetic poetics of fire played out in the body. For example, impulses work their way through the dancers’ bodies which jerk at speed. Each body has its own way of enacting these qualities. Lily Paskas rips through space without pause for thought. Sometimes the dancers are dancers, forming duets, circles, lines, hoisting bodies, lifting legs. Other times, their bodies are a staging ground for actions that reflect ideas of fire, heat, light or convection.

As this dance is performed, bushfires rage in the Blue Mountains, destroying hearth and home with a fearsome intensity. The dancers stage a form of collapse in their bodies. There is less sense of danger here however, for the group hovers, ready to catch them. Rennie McDougal performs an interesting solo with elements of collapse and support within his own body rather than in partnership with the group.

Returning to ritual, four dancers sit in front of large ashtrays, striking matches in time to the sound. These simple relations between light and sound are mesmerising to watch, an aesthetic form of child’s play.

At some point well into the piece, the choreography really took off, in terms of flow, intensity and energy. It would have been wonderful to see the entire piece operate at this level. This is probably a question of time and resources, to be able to dwell with the choreography, edit, rework and polish. Another iteration of this piece-—a phoenix perhaps—might consider the coherence of its parts, the relation between its sections, and to the theme as a whole, moving beyond an episodic feel to some other sense of structure or interrelationship between the various thematic moments.

A Small Prometheus, creators Stephanie Lake and Robin Fox, choreographer Stephanie Lake, composer, sculpture designer Robin Fox, performers Alana Everett, Lauren Langlois, Rennie McDougall, Lily Paskas, Lee Serle; Arts House, Melbourne, 15-20 October

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 31

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Teenage Riot, Ontroerend Goed

photo Sarah Walker

Teenage Riot, Ontroerend Goed

Cinema theory has a wonderful term that doesn’t quite have an equivalent in the discourse around theatre: exploitation. In both industry and critical parlance, the exploitation film has long been that which panders to a particular (often prurient) interest, ‘exploiting’ an exotic or vaguely taboo subject and equally ‘exploiting’ a niche audience attracted to such fare. These are the B-movies of suburban drive-ins, grindhouses and midnight marathons. Perhaps it says something of the overwhelming gentrification of theatre in the 20th century that equivalent alternative avenues have mostly failed to find popular appeal.

Ontroerend Goed, Teenage Riot

While viewing Ontroerend Goed’s Teenage Riot my mind kept returning to the subgenre of teensploitation. It’s a rich vein in film, canvasing everything from the saccharine beach party movies of the 60s to the sensational slashers of the 80s and the more respectable output of director John Hughes during the same period. Originally intended with no more noble goal than to rake in the pocket money of high schoolers, the teen film over time became a way for its typical consumer to develop a sophisticated and critical engagement, assessing the truth and artifice of the depictions on screen and defining an identity both through and against them.

Teenage Riot could be understood as a live comment on all of this. It’s the second part of Ontroerend Goed’s trilogy of works performed entirely by teens, and it explicitly concerns itself with the spectatorship: for much of its running time the large staff of players are hidden inside a wooden box, manipulating handheld video cameras to reveal projected fragments of what’s going on inside. That the audience is therefore cast in the position of voyeur (another nod to film theory) isn’t just implicit. Performers offer teasing glimpses of bared flesh before laughing defiantly down the camera lens, make out with one another and offer instructional sermons on fingering, bully and brutalise and shrug it all off with irony or indifference.

The work could be a challenging, even confronting gesture of inter-generational defiance, and a knowing rebuke to elders who assume teens are incapable of reflecting upon their lot with any critical distance. But here’s why I really began pondering teensploitation: the work is billed as written and directed not by its performers but by Ontroerend Goed artistic director Alexander Devriendt and dramaturg Joeri Smet, neither of whom is close to his teens. I have no idea of the process of development the work underwent, but when a pair of adults append their names as the primary creators of a work concerned with teenage excess and libidinal overflow, which furthermore positions its audience as leering creeps—well, where are Devriendt and Smet in that equation? Teenage Riot leaves everyone looking a little bit dirty, except its notably absent makers.

Anna Jakoba Ryckewaert, All That is Wrong, Ontroerend Goed

photo Elies Van Renterghem

Anna Jakoba Ryckewaert, All That is Wrong, Ontroerend Goed

Ontroerend Goed, All That is Wrong

The third in Ontroerend Goed’s teen trilogy, All That Is Wrong, is a refreshing curative. Performer Anna Jakoba Ryckewaert is also the work’s writer, in more than one sense: the piece consists of Ryckewaert scrawling countless words in chalk on an expanse of blackboard filling the floor of the playing space. The 18-year-old is joined by another youth, Zach Hatch, who films the text as it is written (and which is then projected against a backdrop) as well as operating sound cues. Occasionally the two will speak, but are silent for most of the work’s duration.

Ryckewaert writes the word ‘I’ and begins to add modifiers – ‘18’, ‘Belgian’, ‘introvert’ – which quickly spiral out to encompass a less certain and more connected cross-hatching of identity: corners of the space become crowded with personal fears or global horrors, while earlier sections are revisited and revised. The overall effect is cumulative: we are left with the unmistakeable sense of someone who both thinks and cares a great deal about the world into which she is graduating, and of a work that trusts its maker enough to let her do the talking. Or, at least, writing.

In Spite of Myself, Nicola Gunn

photo Sarah Walker

In Spite of Myself, Nicola Gunn

Nicola Gunn, In Spite of Myself

Melbourne performance maker Nicola Gunn has for some years exploited the most interesting of subjects: herself. Or, at least, an amorphous figure known as ‘Nicola Gunn,’ though one could keep adding more and more quote marks around the name as the meta-theatrical frames around her investigation have continued to multiply. In Spite of Myself is her most accomplished (not to mention hilarious) experiment yet. It’s ostensibly a retrospective exhibition of works by Nicola Gunn entitled Exercises in Hopelessness—Nicola Gunn (1979-present), with a bonus lecture by Susan Becker, international curator at Arts Centre Melbourne. Becker is, of course, Gunn, but Gunn is not entirely Becker, just as ‘Gunn’ is not Gunn, and the way the performer flips between different masks rapidly begins to resemble the cups and ball trickery of a fleet-fingered street magician.

Where Gunn’s ongoing project is most interesting is in the way it amplifies the utter artificiality of theatre, and an extreme form of self-reflexivity that is consistently ahead of its audience, while remaining deeply autobiographical and resoundingly true. Gunn makes art about making art, but rather than descending into navel-gazing she dredges up the very intimate pains and absurdities of that experience. She exploits a trio of older women by giving them the task of fashioning hundreds of tiny clay figurines, which she promptly stomps all over. She rails against the recycling practices of the Arts Centre that is presenting her work, even though that work itself will end up as a very real pile of garbage by the show’s end.

And underlying the futile artistic acts in which Gunn indulges is the worry that all art is quite useless, that she is yelling into a void. Where many peers stall at precisely that point, Gunn (or ‘Gunn’) somehow forces her audience to join hands and yell with her, creating a shared experience she describes as a heterotopia, though naming it seems just one more futile gesture. In Spite of Myself is, indeed, an argument against its own premise, an effacement of Nicola Gunn that produces a sort of ur-identity among her viewers. It’s bloody funny, too.

Emily Milledge, Room of Regret, The Rabble

photo David Paterson

Emily Milledge, Room of Regret, The Rabble

The Rabble, Room of Regret

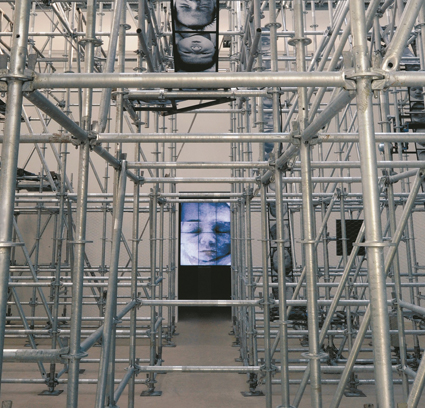

That “all art is quite useless” is the contradictory provocation that prefaces Wilde’s The Portrait of Dorian Gray, the latest text to be mercilessly ravaged by Melbourne outfit The Rabble. As with all of the company’s work, a familiarity with its source(s) offers no magic key to unlocking its secrets, and Room of Regret is in some respects its most inward, mysterious production so far.

The performance occurs within a maze-like installation in which audiences are split up and seated in separate rooms. Performers are often invisible to a good portion of that audience, then, or mediated via screen and projection. The text is similarly splintered, with short portions of Wilde’s words carved from their context and repeated over long durations, usually in a heightened and histrionic manner.

The visual realisation of the work is decadent, lush, almost overpoweringly so, drawing in influences from the Baroque and Victorian to 70s glam and contemporary performance art. The design, too, is both disorienting and appropriate—in separating audiences and their gazes, we are no longer the crowd but become keenly aware of our disconnectedness in a shared experience. Excess and anomie thus shift from themes in a novel to very palpable sensations in this work, and once again where The Rabble exceed most others is in producing this visceral, rather than literal, conjuring of a written text’s essence. It’s uneasy, incomplete, even hard to like, but almost impossible not to admire.

Melbourne International Arts Festival: Ontroerend Goed, Teenage Riot, director Alexander Devriendt, writers Joeri Smet, Alexander Devriendt, Fairfax Studio, 15-18 Oct; Ontroerend Goed, All That Is Wrong, writer Anna Jakoba Ryckewaert, director Alexander Devriendt, Fairfax Studio, 19-20 Oct; Sans Hotel, In Spite of Myself, creators Nicola Gunn, Gwen Holmberg-Gilchrist, Pier Carthew, Michael Fikaris, performers Nicola Gunn, Maureen Hartley, Brenda Palmer, Annabel Warmington, Fairfax Studio, 9-13 Oct; The Rabble, Room of Regret, creators Emma Valente, Kate Davis, director Emma Valente, design Kate Davis, performers Pier Carthew, David Harrison, Alex McQueen, Emily Milledge, Mary Helen Sassman. Theatre Works, St Kilda, Melbourne, 21 Oct-3 Nov

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 33

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Life and Times: Episode 1, Nature Theater of Oklahoma, courtesy MIAF

The 10-hour marathon performance of Nature Theater of Oklahoma’s Life and Times: Episodes 1-4 begins with a casual introduction from co-directors Kelly Copper and Pavol Liska. “We are in the business of manipulating time and space,” Liska states, “We want you all to take responsibility for this going well.” Life and Times sets out to transform the entire life story of one person, company member Kristin Worrall, into theatre.

Over 16 hours of recorded phone conversations, Worrall meanders, in painstaking detail, from her earliest memory to age 34. The performance text is a verbatim transcript of these phone calls, preserving every verbal tic, hesitation and redundancy from the original source, every ‘like,’ ‘um’ and ‘ha ha.’ It’s an absurdly quixotic endeavour that could easily have become a stunningly banal vanity project. However, thanks to tight direction, playfully inventive staging and virtuosic performances from the ensemble (Ilan Bachrach, Asli Bulbul, Elisabeth Conner, Gabel Eiben, Daniel Gower, Anne Gridley, Robert M. Johanson, Matthew Korahais, Julie LaMendola, Kristin Worrall), Life and Times is an exhilarating and joyous experience.

In the absence of conventional dramatic content, co-directors Copper and Liska masterfully manipulate the subtle relationship between space, time and stage action. Every glance, gesture and choreographic sequence supports, underscores or cuts across the minor life incident being narrated. Performers move in odd formations while describing everyday experiences, and the punctuation of the original phone call (loops, pauses, self-interruptions) is ingeniously re-purposed to trigger formation changes, exits and re-entries, drink breaks and interval restarts. The performance text is also endearingly self-reflexive about its absurd immensity. Near the two-hour mark, the narrator exclaims: “God, this must be so boring for you. Sorry.”

Life and Times: Episode 1, Nature Theater of Oklahoma, courtesy MIAF

Episode 1 takes the form of a musical, beginning appropriately with a bright, folksy overture. The performers sing of memories of being bathed in a sink, of attending kindergarten, of making friends and of growing up in a yellow bedroom. When placed in the wrong reading group in early school, Worrall’s mother has to intervene so she can avoid becoming “a really dumb kid.” Social standing is clearly important from even a very young age, with the text charting petty jealousies about the size of other people’s houses, the kinds of clothes her friends wear and the cars various parents drive. Perhaps mirroring this concern with personal status within the social order, the physical grammar of Episode 1 might be best described as an ironic hipster appropriation of Communist-era mass choreography. The performers adopt and hold strange poses, sometimes aided by bright yellow gymnastic rings, but their facial expression seems consistently anxious, as if worried that despite making the correct gestures they still will not fit into the group.

The stage for Episode 2 is dark and shadowy, moodily lit with swirling stage smoke. Dressed in brightly coloured tracksuits, the performers re-enter with rock-star swagger. Our narrator has dark existential thoughts in the third grade, experiments innocently with sexual behaviours, inspired by daytime TV soap operas, and discovers sex through the medium of her father’s Playboy magazine collection. The emotions described in this stream-of-consciousness childhood remembrance are confused, awkward and ungainly. The treatment of the sung text is overblown, with the high-stakes rock chorus playfully at odds with the sheer ordinariness of the events narrated.

Episode 3 takes place on a manor house set, strikingly reminiscent of Agatha Christie’s The Mousetrap. The performers return costumed as characters in this unnamed detective drama, and the voice of the interviewer appears for the first time, embodied as the ‘detective.’ The acting turns melodramatic, the performers exchange arch looks and make dramatic pauses at unexpected moments, creating an hilarious mismatch between stage action and spoken text. This reaches its apotheosis in a ‘murder’ as the narrator describes her first period and being shocked by the blood. The episode ends with performer Anne Gridley crawling offstage after a frenzied self-questioning as to why this excessive storytelling exercise should continue.

Episode 4 is a tableau, with the cast all standing still onstage as if posing for a group photograph. After the high-energy musical theatrics of the past nine hours, time seems to move slowly during Episode 4. The text turns contemplative, discussing religion, doubt and belief, and the stillness lends the episode a soporific quality. Shortly before the end, the lighting turns green and shiny silver aliens inexplicably appear, silently joining the tableau. After this strange visual non sequitur, the lights suddenly fade to black and it’s all over. My 10-hour investment leaves me still hungry for more.

Melbourne International Arts Festival, Nature Theater of Oklahoma, Life and Times: Episodes 1-4, Playhouse, Arts Centre, Melbourne, 22-26 Oct

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 34

© David Williams; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Rebecca Youdell with audience, Bonemap, Nerve Engine

photo Tai Inoue

Rebecca Youdell with audience, Bonemap, Nerve Engine

Queensland is a river of contradiction. In the lead-up to a federal election that brought Brisbane three tiers of simultaneous conservative government for the first time, the Brisbane Festival launched a new hub for independent theatre, the QUT Theatre Republic, programed by La Boite Artistic Director David Berthold. While there was some muttering about the gender diversity of the mainstage program, the Republic was diverse and full-blooded. Elsewhere in the festival, The Danger Ensemble tackled The Wizard of Oz, Genevieve Trace presented a new work, Aurelian, and Canadians Evan Webber & Frank Cox-O’Connell performed Ajax and The Little Iliad.

Bonemap

My festival journey started early with Cairns-based new media dance collective Bonemap. Nerve Engine and Terrestrial Nerve were sister-shows performed in the same rectangular studio space dominated by a long wall with arresting projections of pulsating and osmotic images. To the left were a deconstructed tree house, a DNA-shaped canopy and a nest of tutus; to the right a circle of fans set on the floor before a wall of mirrors.

For Nerve Engine, an iPhone was strapped to my wrist to trigger sound and visuals through the movement of my hand. The experience was more a demonstration of technology than an immersive performance, which was a surprise, as a Bonemap show is usually a sumptuous visual feast. Terrestrial Nerve was more familiar: an eco-poetic chamber piece riffing off evolution, moving from the cellular to full-blooded creatures, teasing the audience with the performers’ marsupial-staccato movements and decomposing costumes. My favourite image: a length of fragile white silk, a materialisation of the nerve imagery in the projections, was blown up by the floor fans into a choreography that echoed the two female performers’ mimetic animal bodies. However, the brevity of the 30-minute piece in contrast to the scale of the space was a tip that the work had not been finished, or fully resolved. Two of the installations in the space were barely used and the transitions felt arbitrary rather than fully interrogated.

Fleur Kilpatrick

Another piece with gorgeous screen work but with under-utilised performance was Adelaide Fringe favourite, Insomnia Cat Came to Stay by Fleur Kilpatrick, a one-woman show where the performer, Joanne Sutton, is trapped by her bedsheets and spends her hour with us in a stream-of-consciousness recounting of her sleeplessness. The effect was dreamlike and a little dissatisfying, akin to watching video-clips all night when you know you should go to sleep.

Genevieve Trace

A similar trance-like quality was evoked by local performance-maker Genevieve Trace’s new work, Aurelian (presented by Metro Arts and Brisbane Festival), a bass-thrumming solo show built around the mesmerisingly repetitive performer Erica Field, who is trying to come to terms with her grief. “I must work these things in order,” she says. We watch a screen that skates across a regional small town landscape, over burning cane-fields. We listen to her recount stories of grief that come from that place. We learn, eventually, that our female narrator is hiding from us and from her diminishing memories of her dead sister. Like Insomnia Cat, there is much to enjoy in the surrender to the compelling screen-led world, shaped by soundscape and a metaphoric and uncompromising design of entrapment. But there is also something fundamentally not yet discovered, additional layers and potentialities sitting beneath the surface.

Danger Ensemble

Ditto for The Danger Ensemble’s collaboration with playwright Maxine Mellor for La Boite and the Festival, The Wizard of Oz. This was the most anticipated local work and one that ought to have brought the house down with the talent of the cast, creatives and crew, but instead felt like a dry run for the real show, a sketch of something extraordinary. The compelling design seemed to lock the performers into their corners and wouldn’t let them go as they gallantly battled the cultural juggernaught of Oz and Judy Garland and Wicked with their own inimitable brand of pop culture impresario spectacle.

MKA

But the joy of the festival is always in getting a look at key interstate shows and this year we got both the Melbourne and Sydney indie darlings of new writing: MKA Theatre of New Writing and Arthur. MKA’s The Unspoken Word is ‘Joe’ by Zoey Dawson is a meta-theatrical satire of the ‘staged reading,’ a sort of inner-city hipster Pirandello tale, as our hapless but malevolent heroine, the playwright, tries to bully, blackmail, seduce and cajole her way through a disastrous reading of her new work, climaxing with her destruction of her own no-budget set and being cradled by the vacuous mid-career director she had dragooned into hosting her ill-fated masterwork. Sort of Lally Katz with a plot, the piece self-consciously linked itself to Tony Kushner’s Angels in America in a way I still don’t quite understand, but have very much enjoyed trying to work out.

Catherine Davies, Julia Billington, Cut Snake, Arthur

photo John Feely

Catherine Davies, Julia Billington, Cut Snake, Arthur

Arthur

However, it was the show by Arthur (Amelia Evans, Dan Giovannoni, Paige Rattray), Cut Snake, that seduced me utterly. Cut Snake is a magic realist story of three childhood friends, one of whom dies, setting the other two on unexpected life trajectories. I have so often experienced the pull in Australian performance between body and word and between plot and experience. What I thought was splendid about Cut Snake was the way they had clearly engaged in a writing process but committed to a form that was driven by physicality. This was made possible by the calibre of the performers, who could move effortlessly between the dense and lively dialogue, narration and the physical tricks and spectacle. It was also a tribute to the direction by Paige Rattray. She used pace and a classic youth theatre compressed staging to keep the show’s relentlessly charming steam engine chugging to the sentimental but highly pleasurable climax. The audience completely bought into the Back to the Future time travel plot twist and happy ending that changed the fate of the two remaining friends.

New writing: directions

Much of the new writing I’ve seen, like that of MKA and Arthur, celebrates language and is making language-driven performance but eschewing naturalism for a plethora of dynamic forms and physicalties, gobbling up genre fiction and speculative writing tropes and blending them with classic theatrical mise en scène. Most importantly, there is a sense with the best of these shows that they aren’t half finished or half-baked, the theatrical worlds have been thoroughly investigated and the writing is taut, surprising and full of bite and adventure.

As I waded through Theatre Republic’s river of contradictions to the final show, the beautifully downbeat, personal, balanced and ever-so-Canadian interpolation of the classic Sophocles text Ajax and the proto-Homeric fragment known as the Little Iliad (7th century BCE), I was struck once again by the portents of the future and how much political theatre might get made in the coming years. “Arts for all Queenslanders,” said the State Government advertisement in the Brisbane Festival brochure—except maybe for our bikies who probably won’t even mind not being able to congregate in the public spaces of next year’s Theatre Republic.

Brisbane Festival: QUT Theatre Republic, QUT Creative Industries Precinct, 7-28 Sept; Aurelian, Metro Arts, 7-15 Sept, Ajax and Little Iliad, Metro Arts, Sept 24-28

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 35

© Kathryn Kelly; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jordan Cowan, The Dark Room

photo Shane Reid

Jordan Cowan, The Dark Room

In The Dark Room, a horror story within a horror story, Angela Betzien reaches deeply into the heart of regional Australia to produce a savage, gothic thesis on socioeconomic disadvantage engendered by decades of institutional neglect and misapprehension. The overt racism of Edmund Barton’s White Australia Policy having given way to the quietly virulent injustices of Aboriginal deaths in custody and the Intervention, Betzien positions both white and black Australians as victims of a broken but mostly unregarded system, children as its most grievous casualties.

The child at the centre of Betzien’s story, which is set entirely in a squalid Northern Territory motel room, is Grace (Jordan Cowan), a damaged and dangerous teenager. In a chilling symbol of her invisibility, she enters the room for the first time, accompanied by her guardian Anni (Tamara Lee), wearing a dark cloth bag on her head. Only her eyes are visible, peering shrunkenly and often glisteningly through badly cut holes. They are eyes that have seen something of which Grace cannot yet speak, and the details of which Betzien only gradually leaks through short, fraught scenes of increasing claustrophobia and nightmarish fragmentation.

The room, designed with striking attention to detail by Kathryn Sproul, becomes a physical and temporal crossover point between Grace’s story and those of previous and future occupants, all of whom are connected to a second individual tragedy, that of Indigenous boy Joseph (Taro Miller-Koncz). Joseph’s presence in the play is mostly incorporeal, appearing fleetingly and frighteningly in technically superb reveals within the motel room’s mirrors (lighting Mark Pennington). Initially difficult to read on account of the play’s shifts in time—a memory, a foreshadowing, a product of Grace’s discontinuous psychic space?—these unsettling apparitions build to a broader significance, a darkly playful rendering of the idea of a haunting, of the immediacy of the past and its still uncorrected wrongs. (From Betzien’s program notes: “Justice will only come when we as a society acknowledge what the dead have suffered…”)

Director David Mealor arguably makes too much of the script’s oblique horror movie appropriations (the sound design, too, by Quentin Grant, goes a bit too far down the same road with its clichéd forays into reversed playback) but the strength of Betzien’s message remains undiluted by this production’s occasional stylistic excesses. Cowan gives a memorable performance as Grace, genuinely disturbing in its intensity and impressive in its proximity to the truthfulness of the lives of our young who have been given too little, and who have seen too much.

By the end of The Dark Room, we too may feel we have borne witness to too much. There is, both within the play’s uncertain dénouement and the disorienting blackouts which periodically descend throughout the 90 minutes, a gut-wrenching sense of the unendingness of cycles of destitution and disempowerment that are the silent shame of this country. The great strength of Mealor’s direction is that Betzien’s motel room feels as inescapable to us as it surely must do to Grace. In reality, those of us fortunate enough to be able to can—and do—escape it every day, willingly protecting ourselves from the horrors within even as successive parliaments fail to protect those for whom the door remains firmly shut.

Flying Penguin Productions with State Theatre Company of South Australia & Holden Street Theatres, The Dark Room, writer Angela Betzien, director David Mealor, Holden Street Theatres, Adelaide, September 14-28

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 36

© Ben Brooker; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jane Phegan, Olivia Stambouliah, The Vehicle Failed to Stop, Version 1.0

photo Heidrun Löhr

Jane Phegan, Olivia Stambouliah, The Vehicle Failed to Stop, Version 1.0

The legacy of the Iraq War lives on in endless killing generated by an invasion predicated on lies and characterised by mismanagement—including dissolving the police force and army—and the realisation of an opportunistic Western fantasy of the country as a free market totally open to its invaders. Version 1.0’s Deeply Offensive and Utterly Untrue (2007) devastatingly revealed the bribery and cover-ups rooted in the still unfolding Australian Wheat Board “Oil for Wheat Scandal.”

The company ‘revisits’ Iraq in The Vehicle Failed to Stop, focusing on an incident—the killing of a woman and her friend by outsourced security forces—that embodies what many people in the region must see as further Western terror. The corruption of Halliburton and the violence perpetrated by Blackwater’s mercenaries are well documented, but the Australian connection is less well known, and while not the focus of this production it’s certainly discomfiting to reflect on. Long-range rocket attacks and now drones (their operators literally working at home in the US thousands of miles away) distance Western governments and their populations not simply from the horrors of war but from feelings of responsibility for it, especially if it means fewer of our own troops are involved and harmed. This phenomenon is fast becoming war by other means.

Even more worrying is the revelation that employees in Blackwater and other contractors’ private armies are exempt from prosecution by Iraq’s legal system (much to that government’s consternation), as happened when taxi-driver Marou Awanis and Jeneva Jalal were shot by private security contractors working for the Australian-owned company Unity Resources Group for driving too close to a company vehicle in a secure section in Baghdad. An attempted prosecution in the US failed—outsourcing, it seems, makes the US Government not responsible for the actions of the companies it contracts.

Version 1.0 reveals not only the cruelty and mistruths inherent in contractors operating outside the law but also the suffering of some of their employees—fuel tank drivers forced to venture across unnecessarily dangerous terrain and dying with little or no compensation for their families. The production reveals the contractors’ militias as comprising “thrill-seeking cowboys” or men in a state of “kill or be killed” hyper-anxiety in which they are less than likely to adhere to the rules about how long they must wait before shooting—to the count of 10, with the word ‘thousand’ spoken between each number. This counting rule is chillingly delivered as part of aggressive corporate self-justification.

The Vehicle Failed to Stop opens with a single figure walking towards us from an adjoining workspace, light flaring behind him into the darkened theatre. A suited authority figure (Irving Gregory) of some kind, his repeated muttering is unintelligible until he draws quite near; we hear, “Kill or be killed,” a mantra for survival, or more likely, self-justification for killing in Iraq. The strangeness of his utterance is underlined by electric guitar harmonics and the sharp bell-tones of a struck tin; the musicians, in low, light, are lined along the wall. A car sits facing us on the dark open stage. A large video screen behind shows us the road from the driver’s point of view, in motion. In this very open space the vehicle appears vulnerable, whether occupied by contractors or the female victims—each pair played vigorously by Jane Phegan and Olivia Stambouliah, enacting the tensions felt and alertness needed on the road by both sides in tautly choreographed moves, sometimes seen enlarged on the screen above. When the ugly event we’ve been fearfully anticipating finally takes place, the car shockingly springs apart, doors dangling, boot and bonnet shaken loose. Later it will be re-assembled in seconds to capture a ghostly impression of death by gunfire with blood finger-painted on the bonnet.

These chilling images, counterpointed by low-key delivery of alarming facts and rationalisations (Gregory as various commanders and corporate heads) and vigorous physical enactments provided The Vehicle Failed to Stop with moments of power. But something was missing.

Some critical of the production declared it impersonal. We certainly learn little about the victims even though their family history has a legacy of tragedy not uncommon to the region. But I’ve never felt the ‘personal’ to be the hallmark of version 1.0 productions (even the atypical The Disappearances Project [2011]sees its theme through a kaleidoscope of unidentified personalities). Certainly the female figure at the centre of The Table of Knowledge (2011) warrants some compassion, and there are terribly sad tales told in Beautiful One Day (2012) by members of version 1.0’s collaborator, Ilbijerri Theatre. But the power of CMI, A Certain Maritime Incident (2004), The Wages of Spin (2005), Deeply Offensive and Utterly Untrue (2007) and much of The Table of Knowledge does not spring from the personal. Invariably their strength is drawn from selections from the public record and their ironic reframing: physically, vocally, spatially and technologically, without resorting to satire or mimicry. Version 1.0 has made us listen afresh to what we’ve already heard or seen in the media and re-contextualised it with revealing new information and, above all, a rich variety of inventive performative devices. These are drawn from and build on contemporary performance, performance art, video art and choral and other approaches to voicing, enacting and framing texts.

The Vehicle Failed to Stop displayed limited examples of this inventiveness. The production was neatly, at times tautly, constructed and busy, but an air of detachment emanated from a sameness of delivery, recurrent hyper-physicality (an extended passage with a soldier running repeatedly up and downstage failed to register) and some design superfluity (a row of human-shaped targets seemed merely functional rather than powerfully symbolic). The result was a fragmentary experience: the information made me want to care, but version 1.0’s peculiar capacity to alarm its audiences and at the same time implicate them was not felt. The Unity Resources Group is an Australian company. Version 1.0’s greatest strength has been to home in on Australian institutions and issues of the moment; CMI and Deeply Offensive and Utterly Untrue pointed the finger and targeted blame, as did Table of Knowledge.

The Vehicle Failed to Stop, for all the specificity of the 2003 incident which prompted it, did not feel as focused or as current as its predecessors. Certainly it informed us of the continued expansion of security outsourcing, its neo-liberal economic foundations (Milton Friedman is quoted in the opening), lack of legal redress for victims and ‘occupied’ states either within their borders or in the US and the consistently growing numbers of the dead. But it was as if these were all happening somewhere else, not really connected with Australia, resulting in an ensuing sense of sadness and helplessness, not the anger or bewilderment or outraged laughter triggered by others of the company’s works. That it was ably performed—supported by a strong live musical composition—is not in doubt, but The Vehicle Failed to Stop lacked version 1.0’s usual incisiveness and wit, and not least the ironic framing it has so deftly and effectively employed over many years. The diffuse, if much-praised, Beautiful One Day was similarly problematic.

With its courageous vision, version 1.0 has radically expanded Australian theatre, making us think with productions that directly and unashamedly tackle large, often national, issues with great concision and, amazingly, mostly without us feeling we’ve been hectored or short-changed with generalisations. I hope the company can sustain its vision and further advance its realisation; the light that version1.0 casts on contemporary politics is much needed in these darkening times.

version 1.0, The Vehicle Failed to Stop, devisors Sean Bacon, Irving Gregory, Jane Phegan, Paul Prestipino, Kym Vercoe and Olivia Stambouliah, video Sean Bacon, composer Paul Prestipino, dramaturg Deborah Pollard, lighting Frank Mainoo, Carriageworks, Sydney, 15-26 Oct

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 39

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

James Berlyn, Crash Course

photo Fionn Mulholland, Daxen Photography

James Berlyn, Crash Course

James Berlyn’s Crash Course is a participatory theatre show that takes the form of an immersive language class. Before entering the classroom, the participants are informed by a terse teacher’s assistant they have endured an unspecified trauma and have subsequently lost the faculty of language, and that a teacher, Jakebo, will help to piece it together again.

Simulating the experience of language loss in a performative context, Berlyn has developed Winfein, a fully functioning language which he speaks throughout. In essence, the show explores how people respond when faced with a seemingly impossible challenge.

Berlyn’s imposing and authoritative portrayal of Jakebo, along with the Victorian architecture of the performance space, transports the participants to another time, stirring up familiar sensations of powerlessness in the classroom, exaggerated by the archetypal schoolmaster character, who could be straight out of a Dickens or Bronte novel.

Before long Jakebo shows that he too is anxious and afraid of failure; afraid that he will not help his students adapt, to be able to communicate with him and each other. Changing tack, he softens and begins to converse through song, acting out scenarios to create context for Winfein words and physicalising the Winfein alphabet to form neurological bindings between brain and body. In this way, the class is exposed to a numerical system, an alphabet and six pieces of vocabulary: the Winfein words for ‘adapt,’ ‘help,’ ‘crash,’ ‘yes,’ ‘no’ and ‘good.’ ‘Tsoopun’—Winfein for ‘Help!’—rang through my mind for most of the work. That much I learnt.

I’m not sure if the initial premise of relearning language following a traumatic incident was necessary to the success of this work. The anxiety in the room, the fear of returning to a classroom and not understanding what is being taught, was palpable, bringing out participants’ innate reactions to either adopt the language and conquer their fears, or crash quickly when challenged with something they could not immediately grasp. I even found myself checking my friend’s worksheets to assure myself I had got at least one thing right and, let’s be honest, to cheat when I didn’t know the answer. On the other hand, my friend diligently applied herself to the worksheets long after the class had moved on to another task, determined to assimilate some meaning from a disorienting experience.

Director Nikki Heywood crafts a taut structure so that Jakebo pulls back just at the right time when the participants need some breathing space. Her acute sense of space and movement allows Berlyn’s physical work to shine; fluid, sweeping yet contained, he creates a surprising contrast with the initially uptight, no-nonsense presence of Jakebo at the beginning.

James Berlyn has an excellent capacity for creating work which can be packed into a suitcase and pulled out anywhere. His creation of the Winfein language and our subsequent immersion in it takes this idea to a new level. The potential to perform this piece anywhere, no matter what the first language of the participants, suggests enormous potential for the work across the international festival market.

James Berlyn, PICA, Performing Lines WA: Crash Course, creator, performer James Berlyn, director Nikki Heywood, lighting Jenny Vila, sound design Geoff Baker, graphic design Shaun Salmon, costume Anne Marie Terese, teacher’s assistant Sarah Nelson, PICA, Perth, 14-30 Nov 2013

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 40

© Astrid Francis; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Deborah Mailman, Marcia Langton, The Darkside

photo Tony Mott

Deborah Mailman, Marcia Langton, The Darkside

Drawing upon primal fears of darkness and the mysteries of death, the ghost story is perhaps the most relatable of tales. With this feature-length addition to a venerable ghost anthology tradition which encompasses collections of stories from different cultures, eras and individual writers, Samson and Delilah (2009) writer-director Warwick Thornton seeks to explore an Indigenous experience of the ‘other side.’

After calling via traditional and social media channels for first-hand accounts of ghostly encounters, Thornton and producer Kath Shelper narrowed an initial 150-odd submissions down to a dozen. Using Thornton’s interviews with these 12 storytellers as core material for the screenplay, the resulting film is part-genre, part-oral history project. It is full of a promise that doesn’t quite materialise.

Except in a couple of cases where the storyteller doesn’t appear onscreen, each story is presented essentially in monologue by an Australian actor, with Bryan Brown, Deborah Mailman, Claudia Karvan, Aaron Pedersen, Jack Charles and Sacha Horler among the prominent names featured. Thornton’s preferred approach is to maintain a largely static shot of the teller in his/her environment—an environment that sometimes reflects the narrative (river and coastal stories are told by Brown and Horler near water; Shari Sebbens’ account of a family vigil for a dying infant is told in a hospital). In some instances, however, more lateral or abstract images are superimposed over the teller’s voice, most notably during Sharon Cole’s eerie roadside tale, accompanied by artist Ben Quilty working close-up on one of his characteristic impasto landscapes. Ultimately, the painting resolves at a distance into an image which resonates with the story’s conclusion. It’s a texturally interesting approach, though the footage tends to compete with the words.

It’s no coincidence that the more concise stories, as well as those whose visuals accentuate rather than nullify the verbal content, are among the more engaging in the collection. Filmmaker Romaine Moreton speaks of a troubled residency at the National Film and Sound Archive, formerly the Australian Institute of Anatomy, over a pastiche of foreboding interiors, historical ethnographic footage and the piercing light of a film projector—images which lend a clinically cruel edge to her account of the unsettled dead. Some narrators command more attention than others, with skilled raconteur Jack Charles at the fore here.

The Darkside’s main problem is verbosity. Thornton’s commitment to exactly replicating these interviews, intrinsically interesting as they are, is at odds with the overwhelmingly visual nature of cinema. As tales meander and fall into repetition, the viewer’s attention wanders. The director’s recent forays into video installation with Stranded, 2011 (commissioned by the Adelaide Film Festival; RT102) and Mother Courage, 2012 (commissioned for Documenta13; RT113) seem to have influenced The Darkside’s deliberate pace and use of imperceptibly changing imagery. It’s an approach that’s more suited to the fluid dynamic of a gallery than the captive situation of the movie theatre, where attention needs to be seized and maintained. Thornton might have been trying to avoid horror movie clichés, but attention to the way the best genre cinema manages to grip its audience viscerally would have given these stories a far greater chance to shine.

The Darkside, director, cinematographer Warwick Thornton, editor Roland Gallois, sound designer Liam Egan, producer Kath Shelper; Australian distributor Transmission Films

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 26

© Katerina Sakkas; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Cat Jones, The Plantarum: Empathic Limb Clinic, Proximity Festival

photo Fionn Mulholland

Cat Jones, The Plantarum: Empathic Limb Clinic, Proximity Festival

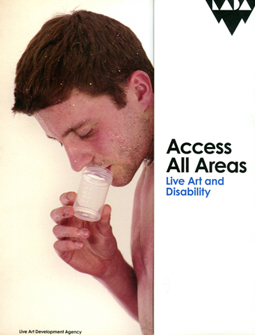

Partaking in Perth’s Proximity Festival makes one feel a little like Alice in Wonderland, inducing an expansive tumbling sensation of descending into a deeper, hidden consciousness. Held throughout the late Victorian home of the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA), the festival sees one artist and one audience member come together in spaces for intimate, personalised 15-minute performances.

Each audience member encounters a series of these micro-works throughout the evening. They can select a program of four works lasting 80 minutes, or a marathon of all 12 performances lasting four hours. I attended two programs over two nights. Here is a selection of what I found when I slipped down the rabbit hole.

The Plantarum: Empathic Limb Clinic

A mobile field laboratory set up in PICA’s main gallery space, The Plantarum explores the synaptic relationship between humans and flora through a blend of neuroscience, mirror therapy and the horticultural technique of grafting.

Drawing upon the niceties of Victorian etiquette, artist Cat Jones invites you, the subject, inside her laboratory, a stimulating environment where Victorian botanics, modern science and technology are enmeshed. Jones then undertakes to generate an empathic connection between human and vegetation, lodging a neural graft via mirror therapy to ‘attach’ a botanical growth to the subject’s hand. No Frankensteinian horrors occur, just a gentle brushing of a soft leaf upon the hands. At the same time the subject watches a screen which shows the hands as they receive this treatment, interspersed with images of the leaf seemingly grafted to and growing from the subject’s fingers.

It is recommended that the subject contemplate the scion daily, absorbing it into the consciousness to lead to a greater connection with botanical species. While I am yet to tune into any messages conveyed by my garden’s subsystem, this piece was a complex, immersive and inventive experience in which to contemplate the possibility of forming a deeper bond with the greater vegetative kingdom.

Loren Kronemeyer , Remains Management Services, Proximity Festival

photo Fionn Mulholland

Loren Kronemeyer , Remains Management Services, Proximity Festival

Remains Management Services

Loren Kronemeyer wants to ensure you make an educated decision when it comes to choosing how you want your physical remains handled after death. She provides you, her client, with multiple options for managing your remains, ranging from traditional means such as burial or cremation, to environmentally friendly choices including biodegradable casks and crematorium carbon offsets, as well as more elaborate plans such as being sent into outer space.

Kronemeyer offers to document your “remains plan” to serve as a true testament of your wishes that may hold some legal weight if any contention arises. This element adds tension and a twist to the work, where the participant is faced with the potential of generating a binding document within a performance environment. While the idea of my remains being turned into a diamond or having a burial cairn built in my backyard sounded enticing during the performance, pledging to such a commitment or even a more traditional option was something I couldn’t commit to in the moment, which certainly raises the stakes in terms of the participant’s investment in the performance.

Sarah Elson, Incendia Lascivio, Proximity Festival

photo Fionn Mulholland

Sarah Elson, Incendia Lascivio, Proximity Festival

Incendia Lascivio

Sarah Elson invites you to deconstruct her large art piece comprising manifold miniature metal castings: invites you to melt it, in fact, and then re-cast the metal to create a new work. Elson nimbly guides you through the concerted effort of managing fire and crucible to produce a small sculpture of West Australian flora. I was captivated by this process. A flower is set in plaster and fired by a kiln, which completely disintegrates the bloom but leaves an intricate fossilised imprint of the flower in the plaster. By melting the sculpture taken from the artist’s initial work and then re-casting it in this plaster mold, a new and distinctive bloom of coppered elemental splendour springs forth, which Elson humbly presents to you as the custodian of this particular piece of her reworked art project.

Gallery of Impermanent Things

Stillness is often difficult to achieve, particularly during a festival where you may have just come from a performance where you were a sniper who had to hunt or be hunted or blindfolded in a room with a Minotaur. Stillness and calm is, however, achieved in Daniel Nevin’s portraiture exhibition which leaves only a temporary trace of his subject and work.

Combining elements of traditional photography and digital imaging, Nevin requires his subject to reach a point of perfect stillness while a long exposure in a darkened room captures his/her image. Simultaneously, the exposure is projected onto a surface covered with phosphorescent paint, whereby the projected light activates the paint to capture a portrait reminiscent of 19th century Daguerreotypes: ghostly, self-consciously reposed and lacking in the benign and beaming poses that we enact for the camera today. The phosphorescent image eventually fades, returning the gallery to darkness once more. The work is fleeting like performance, like memory. Nevin explores our obsession with trying to capture and preserve ourselves, asking us to delight in the unique exchange of a small moment and reminding us that nothing—particularly the image of the self—is permanent.

Proximity Festival, curators James Berlyn, Sarah Rowbottam, producer Sarah Rowbottam, program A artists Elise Reitze, Cat Jones, Humphrey Bower, Loren Kronemeyer; program C artists: Sarah Elson, Moya Thomas, Janet Carter, PICA, Perth, 23 Oct-2 Nov

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 41

© Astrid Francis; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Klare Lanson & Kathrin Ward, #wanderingcloud – Campbells Creek

photo Kathryn Baulch

Klare Lanson & Kathrin Ward, #wanderingcloud – Campbells Creek

You walk into the Theatre Royal, Castlemaine’s versatile theatre-gig-cinema-performance-space, into a partitioned-off candle-lit bar where projections of pastures, eucalypts and dissolving clouds loop onto large hanging canvas, mingling with the sound of feedback and frogs. You sense the performers on the other side of the curtain, silhouetted as the music begins.

It’s a performance in layered sections, of trickle-down effects: Klare Lanson, remembering the flooding of her house at the bottom of a huge hill, stands on tables as the water swirls around. She speaks to locals about the rush, swimming from one storey to another, as they share their “recipe for the natural disaster”—the dangerous clouds, the tale of a pig who doesn’t get along with sheep (but is forced to shelter with them), the raining down of “millions of trembling spiders”—and their voices stream from the laptop Lanson guards and commands like a digital composer, wearing a clear raincoat and a t-shirt saying “heaven sent,” or “the flood line here” marked near the bottom of her skirt. She scatters her churning text and sound to the winds while she geo-tags the collective memories of communities in trauma.

Musician and writer Neil Boyack takes off, guitar-strapped and thumping in a Western shirt, while the Octaphonic Frogs are decked out in military gear and hats. Soprano Andree Cozens barks and croons, drawing calm in a muddy landscape visually mixed by Jacques Soddell. Kathrin Ward, heavily pregnant with twins, is draped in a bubble-wrap wedding gown and as she walks she clicks the seductive plastic, unravelling herself, inviting you to join in, until the wall of crackle sounds like a bonfire, warming your wet skin.

On the floor, like detritus left on the riverbank, instruments are scattered about, tripped over. The Clocked Out duo take the audience on a percussive ride, improvising with objects they’ve found strewn around local properties: a falling-apart piano (played with elbows by Erik Griswold); a long chain that rattles like thunder; cables mashed and whispering along the wooden floor like river gum roots. Along the way Lanson laughs, dances with you in the summer rain, soundscaping and reverbing— “my fingers are triggered by the hidden voice in your stories”—her voice wavering from lullaby to panic, and others join hers as tributaries then channels then canals, as the real storm hits.

Newstead. Campbell’s Creek. Guildford. Carisbrook. A swinging bag is pushed like a pendulum. In the soft spotlight, Vanessa Tomlinson turns it, emptying grain in a rush onto the floor, the various timbres and tones playing out like rain on a tin roof, stopping and starting, subtle and delicate, the transfixing sound of childhood, all too rare in a Castlemaine drought.

But that’s what the weather’s like here. It swings from one extreme to another. Flood to drought. And back. Drought to flood. And back. Then every summer your phone beeps with fires nearby. The threat of flames. The one track out. The smell of smoke that sends your senses racing. But the phone beeps so often. That soon you no longer hear it.

#wanderingcloud, Klare Lanson, a collaborative performance featuring Klare Lanson, Clocked Out Duo, Andree Cozens, Jacques Soddell, Theatre Royal, Castlemaine, 5 Sept

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 41

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Slow Dancing, David Michalek, Trafalgar Square, London, 2010, courtesy the artist

WOMADelaide has long celebrated dance in its programs with, for example, performances by the Australian Dance Theatre and Leigh Warren & Dancers. For the 2014 festival, there’s something different: a trio of three-storey-high screens on which dancers, many internationally famous, appear against the night sky dancing in extreme slow motion. This is the work, seen in the US, UK and Europe (including the Venice Biennale), of American artist David Michalek.

Slow motion filming has long revealed the complexities of human, animal and plant movement (conversely, ‘speeded up’ film can tell us much about cloud and crowd motion and the patternings created by choreography). Michalek’s special high-definition camera runs at 1,000 frames a second, turning each dancer’s “five-second gesture [into] 10 minutes of screen time” (press release). Michalek thus takes slow motion to the extreme, such that audiences, at first thinking they’re seeing still images, are gradually entranced by the supple dynamics and forces at work in dancers’ bodies.

Michalek’s 43 subjects range from young to mature, embracing a variety of dance and movement forms: “from Japanese court dance to Afro-Brazilian capoeira, from flamenco to hip-hop, from classical ballet to hoop dancing.” Accomplished lesser known artists dance alongside the likes of dancer-choreographers William Forsythe, Marie Chouinard, Bill T Jones, Karole Armitage and Angelin Prelocaj. Bill T Jones wrote of the experience: “I was trying to do something with undulations and directional changes that would give some insight into the way I move—the upper body doing one thing, the legs doing another. But four seconds is not very much time to do anything. That was a revelation. We are so naked when we move. It was kind of a gruesome thing to subject a performer’s ego to, but ultimately I think that’s what’s very beautiful about it. It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. If one element fell through, everything was erased. It was a bit of a Zen test”

(www.slowdancingfilms.com).

Michalek professes not only a love of dance and the impulse to make portraits, producing a fascinating hybrid that embraces both stillness and movement at once, but also a spiritual inclination. He writes:

“Susan Sontag once pointed out that ‘no art lends itself so aptly as dance does to metaphors borrowed from the spiritual life (grace, elevation)…’ But I also believe that certain harder and rougher metaphors borrowed from the life here below (gravity, striving, failing, falling) are equally important to what dance is and who dancers are. To paraphrase Simone Weil, grace is also the law of the descending movement—some people fall to the heights” (www.slowdancingfilms.com).

Amid WOMADedaide’s wealth of vibrant music performances, Slow Dancing will offer time and space for contemplation of, and even meditation on, the magical intricacies and fluency of movement of which the human animal is capable. RT

WOMADelaide 2014, Slow Dancing, artist David Michalek, Botanic Park, Adelaide, 7-10 March

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 42

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Anneli Bjorasen, Turbulence

photo David Young

Anneli Bjorasen, Turbulence

Despite being the closest any of us will come to experiencing a miracle, air travel is marked by boredom and sustained physical discomfort. With its staging of the explosive relationship between a mother and daughter in an apartment only wide enough for five seats and an airline trolley, Chamber Made Opera’s latest Living Room Opera, Turbulence, explores this banal sort of magic that frames and controls our lives.

Composed by Juliana Hodkinson and featuring the versatile voices of Deborah Kayser and Anneli Bjorasen (in her first Chamber Made Opera role), Turbulence is a ‘first’; several times over for the company in its 25th year.

A row of fans along one wall generates a drafty hum that is amplified into an ambient drone by Jethro Woodward’s ever-understated sound design. The audience take their seats, the front row facing a white wall. I wondered where the performance would take place until Bjorasen began to hum, “pshh” and “khh” like the pneumatics of an aircraft beside me. This opening is the first durational piece I have experienced in a Living Room Opera, providing a welcome contrast to the enchanting kaleidoscopism of previous works. It is also the best environment in which to hear Woodward’s minute control of transparent textures, even in a sound world as saturated as a series of amplified fans. Kayser and Bjorasen’s stereophonic sound effects are a delight, making the central seats the best in the house.

Other sounds endemic to airplanes begin to fill the cabin—a baby crying (live and recorded), 1950s cabin announcements and Bjorasen struggling with a packet of nuts. Bjorasen leans as the plane banks to the right, leaving me in an awkward position for several minutes.