May 2014

Sanitary Apocalypse

Artist Statement

I had the idea for a narrative about a world spray-and-wiped into apocalypse years ago after reading an article about dirt pills given to children in the United States to boost their bacteria. When I was completing my last album, Gen Y Irony Stole My Heart, I was already thinking about what I could do next to up the ambition ante: I wanted to do a long-form, orchestrated narrative song. After marrying the two ideas, I composed Sanitary Apocalypse over roughly a year, followed by a year of recording, mixing, finalising and publicising the beast.

I wanted it to come as a surprise in the story that, despite the apocalypse, people are generally getting on, doing okay and finding a way rather than regressing to violent competition and eating each other or whatever else they do in apocalyptic fantasies these days. I also worked from the principle of swapping the gender of all characters once they’ve been conjured (where gender politics aren’t integral to the narrative); you seem to get much more interesting stories that way. I ended up with a ‘final girl,’ only she doesn’t suffer quite the humiliation, breakdown and torment most final girls do.

Perhaps the most challenging thing I did was to write a bunch of themes—hopefully independently interesting—that would lock together at the climax. So I wrote those synth arpeggios and keyboard chords at the end to sound continuously ascendant, adding themes from throughout the piece until the whole thing is being played at once.

Wyatt Moss-Wellington

Wyatt Moss-Wellington

photo Stephen Lew

Wyatt Moss-Wellington

Folk phantasmagoria

Wyatt Moss-Wellington’s fiercely ambitious and willfully idiosyncratic Sanitary Apocalypse is something of an anomaly within contemporary Australian music. Described as a single 28-minute song, the work consists of distinct song-like fragments that emerge from a body of through-composed musical tissue, blending elements of folk, jazz, prog-rock, electronica and the 20th century avant-garde. It charts the journey of protagonist Clara through a disturbing post-apocalyptic vision of an Earth cleansed of all complex life.

Sanitary Apocalypse is a far cry from Moss-Wellington’s 2009 debut The Supermarket and the Turncoat, a more conventional collection of songs in the accepted manner of an acoustic guitar-wielding troubadour. Certain tendencies are clear in this earlier incarnation however: whimsically direct lyrics curling around unpredictable melodic twists; a lyrical style both tenderly heart-felt and savagely satiric; the occasional frenetic solo bursting out of unthreatening finger-picked patterns. It’s a style further developed in his more fully produced follow-up, 2011’s Gen Y Irony Stole My Heart.

With Sanitary Apocalypse, Moss-Wellington seems to have taken the limited broader reception of his earlier efforts as a license to push himself into new artistic territory. Although still embedded in the folk tradition, the concept of the folk ‘refrain’ is here refigured as a series of recurring musical idée fixe. The omniscient yarn-spinniner of folksong is re-imagined as a Greek Chorus offering commentary and information in a tone at once firmly solemn and archly ironic, a scene setting line such as “in the end we sprayed and wiped our whole world away” dismissing cataclysm with a raised eyebrow and a shrug.

There are many delights to be found here, Clara’s farewell to her dying husband featuring some beautifully realised vocal writing, perhaps reminiscent of Björk’s Medulla. This section unravels in a cluster of voices chanting over one another, fragments of lyrics thrown to the foreground before being chewed back into the mass, cohering around the words “I love you” in a gloriously illuminated moment of consonance, before collapsing into despair in the form of an unhinged solo from violinist Ian Watson.

Moss-Wellington has assembled a broad range of musicians to realise his artistic vision. One of the pleasures of this recording is hearing performers such as jazz drummer Tim Firth or The Crooked Fiddle Band’s Jess Randall brought together to produce something inclusive, unexpected and complementary, an approach suggestive of Moss-Wellington’s love of Robert Wyatt or the North Sea Radio Orchestra. It is his own vocals that command most attention however, at times relating the saga with cool detachment, at others taking advantage of his startling range for dramatic effect, straining towards his highest possible note at the moment of his heroine’s nadir, pinching the sound to a point of almost unbearable intensity on the single plaintive word “how,” stark piano chords rising into an electronic blizzard of sound before collapsing once more.

There are other moments of almost manic playfulness, a mandolin solo from Moss-Wellington becoming a mashed pastiche of motifs cribbed from violin studies. Elsewhere, the moment of Clara’s rescue is celebrated with an over-the-top bluegrass duel between Dave Carr’s banjo and Randall’s nyckelharpa. The unreality of the narrative moment is underlined by the almost too-cheerful melodic motifs and the breathless delivery of Moss-Wellington’s cartoonish lyrics describing the hyper-futuristic bunker in which Clara finds herself: “the dining room is massive / It’s bustling—full of food, and people, and smiles, water cooler banter.”

Unfolding in a comic phantasmagoria, the work ends with themes from all previous sections swirling together over an inexorably rising bass line, colliding on a single, almost screamed note before voices drop out one by one, leaving Moss-Wellington to close the epic with a single snarled note on the guitar. Self-funded, uncompromising and uncompromised, Sanitary Apocalypse is a unique musical gift.

Wyatt Moss-Wellington, Sanitary Apocalypse; http://wyattmosswellington.com/music/sanitary-apocalypse

RealTime issue #120 April-May 2014 pg. web

Chris Bennie, Fern Studio Floor: a cosmology

courtesy the artist

Chris Bennie, Fern Studio Floor: a cosmology

Artist Statement

In December 2013 I spent three weeks at the Bundanon Trust Artist Residency on the former estate of the artist Arthur Boyd, 40 minutes west of Nowra, NSW. While I was there I spent a lot of the time with my head down. I was working through some personal issues that were troubling me, but what really caught my eye was the residue of previous residents. Bundanon can accommodate artists of all disciplines—dancers, musicians, writers—but Fern Studio was clearly used by painters.

It’s not uncommon for art studios to be covered in paint, but what makes Fern Studio interesting is its history. Each swatch of colour, drip and splatter represents the work of an artist who has participated in the residency prior to my arrival—each of us, I presume, motivated by Boyd’s legacy and the prospect of creating something meaningful.

Armed with a camera and a wide stance I commenced documenting the floor, searching for dramatic compositions. It seemed that everywhere I looked there was a new constellation of colour and form.

Like all my work, in which overlooked things are transformed and allegorised, Fern Studio’s floor is rendered fantastical through its treatment as an animation of slow moving photographs. This process has been informed by the potential for each image to appear not only as a paint-covered floor, but something else. Exhibited at The Walls, Fern Studio Floor is projected upwards, onto a floating screen hanging from the ceiling. Visitors are encouraged to lie down and be seduced by this well trodden floor and its transformation into art.

Chris Bennie

http://www.chrisbennie.com

Chris Bennie, Fern Studio Floor: a cosmology

courtesy the artist

Chris Bennie, Fern Studio Floor: a cosmology

Mediating legacies

Over 30 years ago, in my first years at university in Canberra, we were taken on a day trip excursion to the Arthur Boyd property at Bundanon on the Shoalhaven. The artist had recently returned to Europe but had left his newly completed, timber-lined studio electric with his recent presence. As a student of art history whose experience of painting was largely confined to the finished product on the walls of a gallery or reproduced in large tomes and labored over in libraries, to see such a working studio was a revelation. This was the kind of place from which Boyd’s almost terrifying canvas depicting the painter gripped with doubt and false greed had come (Paintings in the studio: Figure supporting back legs; interior with black rabbit, 1973-74). We had all just seen this work hanging, as I recall, in the cavernous downstairs spaces of the newly opened National Gallery of Australia, one of the few Australian paintings to make it into that hallowed territory where its near neighbours were de Kooning and Pollock.

Ten years on from that work and in the shadow of the escarpment on his bend in the river, Boyd was now producing more meditative images, but it wasn’t so much the paintings on the easel that I remember from that visit, but most indelibly the latest and smartest Bang and Olufsen CD sound system mounted on the wall, its pristine lines abruptly and irreverently disrupted by a brilliant multi-coloured finger mark of paint on the play button.

Fast-forward to the hot early summer of late 2013 and Chris Bennie is artist-in-residence at the Fern Studio, one of a number of artist studios now provided for and managed by the Bundanon Trust. After a busy and successful year of art prizes, grants, exhibiting and lecturing, Queensland based New Zealand born, Bennie was looking forward to a fresh break and the rare opportunity that such a residency offers to be absorbed and focused on a new environment.

Encountering the studio, Bennie reflected on the many artists who had been there before him, all generating new ideas and producing work under the legacy of the Boyds and their regard for the importance of making culture. In an artist talk at the Walls Contemporary Art Space Bennie said that, like Boyd, he reflected on the nature of a studio as a private space of chance, ambition, doubt and mistake, as well as a place from which considered and successful creative output emerges.

Chris Bennie, Fern Studio Floor: a cosmology

courtesy the artist

Chris Bennie, Fern Studio Floor: a cosmology

He found the past presence of all these artists most manifest in the colourful residue of paint: dripped, spilled, dropped and splattered over the timber floor, reading it like a layered contemporary archeology of place. However, unlike the sensation of a patina which fuses the past life of the object into a single texture on the surface, Bennie has read these layers as a three dimensional view and, through hundreds of photographs documenting the minutiae of this floor, has literally inverted and elevated it to become a new and unlikely cosmology.

The formal language of video practice is in relative infancy and often constrained by technological limitations, but Bennie has been consistently interested in physically framing the way that the viewer encounters his work using projection within and onto banal or overlooked architectural spaces. These have included most recently a repurposed caravan retrieved from the devastating floods in Bundaberg. The installation for this work, on a screen suspended from the ceiling, invited the viewers to lie down on their backs on a large raised platform covered in soft carpet and to look upward as a slowly moving constellation of vivid colours passed above. The images of the Fern Studio floor were set within a second frame of a darker blurred image and this highlighted their potency.

The shared experience of lying quietly side-by-side on the platform encouraged strangers to be briefly united by Bennie’s seemingly physically replication for us of his own feeling of absorption, of being in that studio for three weeks. Looking up and allowing ourselves to relax and be taken into this work was a rare and satisfying experience and, of course, if we doubt the importance of artworks that consider the intimacy of our relationships with the built environment, there is the sweet irony that the work depicts a floor on the ceiling in a gallery called The Walls.

Chris Bennie, Fern Studio Floor: a cosmology, 2014, The Walls Contemporary Art Space; 15 March-5 April, 2014; http://thewalls.com.au/about.html.

Virginia Rigney is Senior Curator at Gold Coast City Gallery.

RealTime issue #120 April-May 2014 pg. web

Installation view 2014 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Dark Heart featuring Ian Strange, 2014, Art Gallery of South Australia

A life-sized suburban house, painted black and embedded in the footpath, greets Art Gallery of South Australia visitors and passing Adelaide commuters. Ian Strange’s Landed is provocatively unavoidable in Adelaide’s North Terrace, confronting the CBD with the darker characteristics of suburbia. Welcome to the 2014 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Dark Heart.

Mounted by the AGSA since 1990, the Adelaide Biennial is unlike its internationally-oriented Sydney counterpart in being exclusively a high-level survey of Australian contemporary art. Typically, the AGSA invites external curators for its Biennial, but the 2014 Biennial is curated by the AGSA Director, Nick Mitzevich. This is the first time the director has been appointed to this position.

Explaining the reasoning behind this decision, Mitzevich said, “The Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art is our most important and ongoing artistic undertaking. At this stage in my directorship I feel that it is important to harness every element of the institution to advance the Biennial. The best way that I can do this is to lead from the front. This is also the most direct way of communicating the Biennial’s message. It is important to have a strong curatorial perspective—this is part of my philosophy and my day to day life as a director.”

Installation view Melrose Wing of European Art,

Art Gallery of South Australia, 2013, featuring Berlinde De Bruyckere, We are all flesh

photo Sam Noonan

Installation view Melrose Wing of European Art,

Art Gallery of South Australia, 2013, featuring Berlinde De Bruyckere, We are all flesh

The gallery

In his four years at AGSA, Mitzevich has made major changes, rehanging the galleries, broadening and increasing the audience (27% in that time, now with 685,000 visitors annually in a city of 1.3m) and extending educational outreach. When I spoke to him, he made clear his intention that AGSA should not mimic other Australian galleries but develop a distinctive character.

AGSA’s eastern wing is hung chronologically with predominantly South Australian and Australian art, providing a comprehensive survey of state and national art history through which visitors gain an appreciation of its social history. Aboriginal art of corresponding periods is interspersed with colonial and post-colonial Australian art, telling a parallel story and creating a dialogue. The material includes prints, drawings, decorative arts and photographs as well as paintings, placing all forms on an equal footing. Mitzevich’s intention is to allow the work to tell the story. The display itself is not a revisionist history nor a critical examination of forms and genres (though it encourages critical examination), but shows how history can be represented through art.

But the Gallery’s western wing is hung very differently. The successive rooms each has a theme, for example “Seduction” and “Classical,” where the works presented are from different eras, genres and forms but characterise the theme. The juxtaposition of works that contrast both eras and styles might appear jarring but engages audiences more deeply in the work. AGSA gallery guides invite visitors to choose which path to take through the Gallery—chronological or thematic—and they predominantly go for the themed rooms. The work is densely hung and Mitzevich says that the interior and hanging are intended to convey the feel of a 19th century mansion. The two parallel streams demonstrate alternative ways of thinking about art, art history and visual culture, a lesson visitors take with them.

Mitzevich says, “Audiences are engaging, they want to think and feel and to nurture emotional experiences. They want to be able to leave the gallery with a strong memory of the experience.” The reconfiguration of the Gallery’s exhibits initially came under intense public scrutiny. “South Australian audiences felt part of the transition that this rehang involved, and 6,000 people attended the opening weekend.”

The AGSA has one of the largest collections of the capital city galleries—Mitzevich considers that “the gallery’s strength is in its collection, being asset rich but cash poor”—and so the effective presentation of the collection is crucial. But it is also acquiring new work and its most recent major acquisition, Camille Pissarro’s Prairie à Éragny (1886), fills a gap in AGSA’s European story and will resonate with the gallery’s other landscape works, including a definitive body of Hans Heysen works and its Heidelberg pieces, to address the idea of landscape.

Installation view 2014 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Dark Heart featuring Warwick Thornton, 2014, Art Gallery of South Australia

The Biennial

The 2014 Adelaide Biennial: Dark Heart, comprises the work of 28 artists and collectives around a broad theme concerned with the darker undercurrents in Australian culture. The temporary exhibition space is divided into separate rooms “like cells or chapters of a book.” Mitzevich has worked with many of the artists before and wanted to allow them to develop new work—70% of the Biennial works were made in response to the invitation to participate. Some artists made their most significant work for it, for example Ben Quilty’s The Island, which addresses Tasmania’s colonial past, is his largest painting and one of his most profound, using a Rorschach-like design to suggest a psychological reading of colonisation. Within the Biennial’s broad theme, there emerges an emphasis on Australia’s colonial past and the situation of Indigenous people. Mitzevich’s Biennial thus not only catalyses significant new developments in Australian art, it raises awareness of these important issues.

Installation view 2014 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Dark Heart featuring eX de Medici, 2014, Art Gallery of South Australia

The Biennial art is demanding and audiences now expect to be challenged. Mitzevich states that “art should push the envelope in a considered way.” Film director Warwick Thornton’s Rebirth references Albert Namatjira’s work, exemplifying the reconsideration of iconic Indigenous art and culture through contemporary eyes and highlighting the still unresolved impact of Westernisation and colonisation. Some artists engage directly with existing works in the AGSA collection, creating a dialogue between the Biennial and the AGSA itself. eX de Medici’s installation The Law, a consideration of Iranian politics and culture, incorporates historical Iranian items from the Gallery’s collection.

Brook Andrew’s powerful Australia I-VI considers past representations of Indigenous culture by creating what he describes as large-scale history paintings based on Gustav Mutzul’s 1860s etchings depicting Aboriginal lifestyle and ceremonies that he encountered in the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge. Andrew shows how Indigenous culture was first recorded and reconsiders history painting and its role in visual culture, an artistic strategy well suited to Mitzevich’s approach. Many Biennial works appear to extend the Gallery’s historical and artistic considerations and many Biennial artists reconsider art itself, referring overtly to other art and its place in our cultural history. As the AGSA becomes a co-producer, it enlarges its role beyond the traditional museum role as repository and exhibition space. The Biennial’s interaction with the AGSA collection shows how Australian contemporary art forms a continuum with Australian art history and simultaneously reflects the contemporary world.

In his essay on Tony Garifalakis’ Mob Rule, Mark Feary suggests that art can never provide more than a superficial and thus inadequate analysis of a political situation; similarly, there is no “correct” fully analysed history. Nick Mitzevich considers that showing art of political commentary in an institutional setting doesn’t neutralise the commentary but rather brings it to the public’s attention. While it might not offer an exhaustive or dispassionate analysis, this Biennial urges consideration of major issues.

Nick Mitzevitch

courtesy of the Art Gallery of South Australia

Nick Mitzevitch

The aesthetics

In his catalogue essay for the Biennial, Ross Woodrow suggests that the Biennial is concerned with aesthetic appreciation and that the AGSA hang also encourages a return to aesthetics. I asked Nick Mitzevich whether this idea was consciously developed in curating the Biennial and whether it is also an intention in the AGSA hang generally, or whether the hang is rather concerned with the historicisation of aesthetics. He replies, “Woodrow suggests that the Biennial is part of a zeitgeist return to aesthetics—a broader impulse that he has observed the world over. The idea of Australian artists and even curators as aesthetic sailors was not a conscious conceit but I am drawn to the figurative and to the narrative, and to the matter of making and memory, and these things can be seen as players in what Woodrow calls the aesthetic moment, which in his words is ‘triggered when objects reveal their psychic capacity’…This concern for affect is a conscious player in the AGSA hang generally and with a transhistorical and multimedia approach an aesthetic experience is inevitable (following Woodrow’s argument).”

The aesthetic atmosphere is palpable. For example, Alex Seton’s Someone died trying to have a life like mine is a series of lifejackets carved from marble (the material of classical sculpture) which doesn’t float, scattered on the floor around Quilty’s The Island as if washed up on its shore, referencing drowned asylum seekers.

Mitzevich indicates that he will not curate the Adelaide Biennial beyond 2014. It will be interesting to see how the 2016 Biennial develops under another curator and whether the aesthetic turn continues.

The 2014 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Dark Heart, Art Gallery of South Australia, 1 March-11 May 2014; http://www.artgallery.sa.gov.au/agsa/home; http://adelaidebiennial.com.au

RealTime issue #120 April-May 2014 pg. web

A creative individual’s desire for ideas is unquenchable. Inspiration is drawn not just from other works of art in their chosen field but from the abundance of concepts, narratives and atmospheres found in films, books and music. For Profiler #3 we’ve asked artists to tell us about the words, pictures and sounds that have influenced their practice overall and what’s currently keeping them tipsy.

Phillip Adams | Martyn Coutts | Alex Davies | Lucy Guerin | Samuel James |

nova Milne | Soda_Jerk | Sam Songailo | Lindsay Vickery | Julie Vulcan

Phillip Adams

Phillip Adams, stills from Thumb

courtesy the artist

Phillip Adams, stills from Thumb

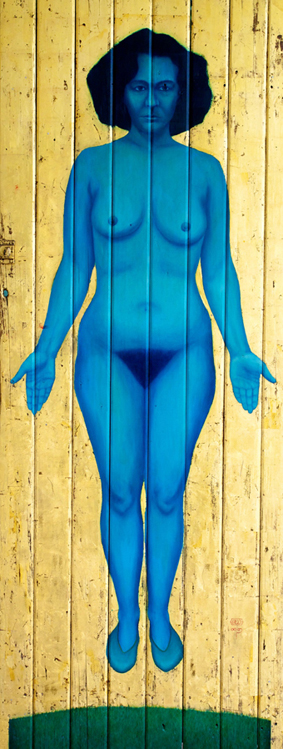

I am about making an experiential form that is new, a place where unorthodox behaviours and research sit at the edge of physical and cross disciplinary offerings. At my most comfortable place of experimentation I take great pleasure in engaging audiences in the live experience of performance and art. For example in Tomorrow, I ask for totally nude participation of the entire audience to build an architectural installation that activates a sexualised, ritual cleansing and group transference and transportation of energies. Tomorrow grew from my own esoteric research into alien abduction and a revelatory experience at The Integratron in the Mojave Desert, USA.

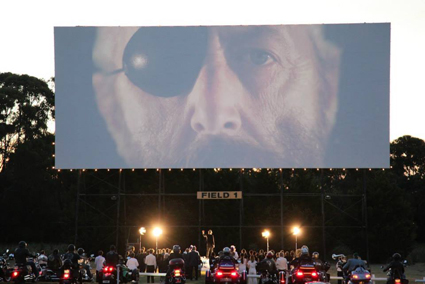

On the other side of the fence I’ve taken to literally hypnotising the audience. Thumb is my first solo work: a cross-disciplinary performance, part installation, part film. It explores the psychology of scale in terms of the gigantic and the miniature, inspired by size changing themes from 1950s and 60s cinema including The Incredible Shrinking Man, Fantastic Voyage and cult Scandinavian film, Troll Hunters.

During the research phases I took a course in hypnotherapy. The bigger question I am asking here is to what degree can the experience of hypnosis affect and effect an art marking practice to create an authentic scale-shifting perception inside the performance. After a 30-minute hypnosis session participants awaken to a world of multiple polystyrene building blocks that suggest any number of backdrops such as Norwegian mountains, caves and snow capped peaks. They also encounter a strange silver alien and a gigantic wall collapsing over them. Midway through they are dressed in green puffer jumpsuits with fur hoods and introduced to an off-the-wall Scandinavian film director and his actors on a movie set. The scale of the work continues to shrink as they watch a film on a 1960s home movie screen of footage shot in the Banff mountain ranges (Canada) and studio developments recreating scenes from The Incredible Shrinking Man.

In addition to Thumb, future projects include a commission from the National Gallery of Victoria that is a response to the Italian Masterpieces from Spain’s Royal Court Museo Del Prado (1 June, 3pm) and LIVE WITH IT we all have HIV (17-27 July, Arts House Meat Market), supported by the Victorian AIDS Council and their regional networks.

http://www.balletlab.com

Related articles

The eyes have it

Carl Nilsson-Polias, Balletlab, And All Things Return To Nature Tomorrow

RealTime issue #114 April-May 2013 p35

For all RT articles on Phillip Adams see realtimedance archive

Martyn Coutts

Sam Routledge, Martyn Coutts (right), I Think I Can presented by Intimate Spectacle and Performance Space at the Art and About Festival 2013, Sydney Central Train Station

courtesy the artists

Sam Routledge, Martyn Coutts (right), I Think I Can presented by Intimate Spectacle and Performance Space at the Art and About Festival 2013, Sydney Central Train Station

Coming of age in the 1990s had a profound affect on the way I view the world. While the mainstream was filled with Stock, Aitken and Waterman pop classics, the underground saw the rise of rave and electronic music. I learnt a lot about repetition, about the structure of a piece of work and about total immersion in a space from raves and clubs. In this respect it is hard to go past “Blue Monday” by New Order, the biggest selling 12-inch single ever, completely unplayable on radio due to its length.

Around the same time that rave became popular, Japanese Anime and Manga broke in the west. The first wave of movies that were dubbed into English were Akira (1988), Ninja Scroll (1993) and Ghost in the Shell (1995). All three borrowed strongly from Japanese history, yet all carried an apocalyptic vision of a post-nuclear future. You could feel the still present fear that the atomic bombs of 1945 had on the makers of these stories. What I took from these films was a questioning of who we are as humans/cyborgs/post-humans. The meshing of the body and technology has always been a key theme of my work. Akira was always my favourite of these films due to its wrapping together of science and spirituality.

More recently I have been undertaking research into Sydney’s Parramatta River for an interactive app called Against The Tide. I have always had an uneasy relationship with Sydney. As part of the reading for the project I started with Delia Falconer’s Sydney (2010) which is such a beautiful evocation of her home city that I almost believed that it is as romantic as she suggests. However, after reading John Birmingham’s Leviathan (1999) I understood where my unease comes from: the terror of the settlement on convicts and Aboriginal people, the corruption stemming from the mixing of government and business and the brutality of the police (among other concerns). I now believe that somewhere between the viewpoints of these two books lies the true Sydney.

http://www.martyncoutts.com

Related articles

It’s all about you

Gail Priest: FOLA, Arts House

RealTime issue #120 April-May 2014 p15

A ghostly bonding

Jessica Sabatini: Luke George & collaborators, Not About Face

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 p30

A game with the works

Gail Priest lives vicariously through Wayfarer

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 p35

Alex Davies

Alex Davies, portrait photo Tommy Oshima; The Very Near Future, photos courtesy the artist

My recent project, The Very Near Future, was undoubtedly influenced by the following works to some degree. The installation combines spatial cinematic storytelling with complex electronically mediated illusions.

Believing Is Seeing: Observations on the Mysteries of Photography, Errol Morris, (2011)

Morris, who is mostly known for his documentary film works has written an intriguing book on photography. Morris examines photography with a healthy skepticism (and in almost forensic detail) with regard to the meaning and authenticity of images. This exploration sheds light on how we can readily jump to conclusions when interpreting photographic images. Although the discussion is centred around photography, the ideas are relevant to all mediated experiences, and many of these concerns inform the ways in which I think about and create electronically mediated illusions in The Very Near Future.

Los Cronocrímenes (Time Crimes), Nacho Vigalondo (2007)

In addition to media illusions, a key theme of The Very Near Future was time travel, or specifically, how one can physically represent a sense of future time travel through media. Los Cronocrímenes is simply a wonderfully inventive film exploring some of the dire implications of time travel. The narrative structure of the film is also quite refreshing and both these elements provided inspiration in terms of potential structural approaches to story telling, and some of the many possible ways time travel can be conceptualized.

http://schizophonia.com/

Related articles

Heck, baby, I shoulda seen it comin…

Urszula Dawkins, The Very Near Future, Alex Davies

ISEA2013 in RealTime, online feature

realtime tv @ ISEA2013: The very near future, Alex Davies

ISEA2013 in RealTime, online feature

For more RT articles on Alex Davies see our mediaartarchive

Lucy Guerin

Lucy Guerin, photo Toby Burrows; (front to back) Stephanie Lake, Alisdair Macindoe, Jesse Oshode, Live Movie Rehearsals, photo Lachlan Woods

At the moment I am working on a project called Live Movie in which I want to screen a full-length feature film (not sure which one yet) and use it as a score for a dance piece. I want to use the edits, camera movements, sounds, characters and narrative as ways to generate movement both improvised and choreographed, responding to the movie in real-time. I aim to show not so much a representation of the film but to use the elements of filmmaking to create a dance work.

I saw David Lynch’s film Blue Velvet (1986) in my mid-twenties, when it first came out. I haven’t seen it since, but I clearly remember the opening scene with its bright, cut out world of the ordinary everyday, and then the zoom in to a bright green lawn drilling down to a close-up of subterranean insects chomping savagely below the surface.

This was the film that made me realise that you could see things differently. That there’s a multitude of perspectives from which to view something; that artistic expression was not just about an idea that you had, but about how you showed it; about how style and genre connected to meaning. It was entertaining and had great music, but also a dark, unfathomable side. These two things sat together.

As a choreographer working mostly in theatres, I have often thought about how we can shift the frame of viewing from the square of the proscenium where everything is life-size, to give a sense of close-up, to draw the eye of the audience in a filmic way. Lighting helps of course, but how, as a dance-maker can I create movement that draws us in to see detail?

Growing up in Adelaide in the 1970s and 80s I wondered how my middle class, unremarkable background could offer up anything unique or interesting as artistic material. Seeing Blue Velvet revealed to me that the ordinary aspects of life can be horrific or beautiful or funny, depending on the way they are presented. That zoom in to the lawn revealed how the simplest things could contain worlds and that looking closely is where I could find poetry. It was in detail, and in what lay below the surface.

http://lucyguerininc.com

Related articles

See realtimedance, 12 choreographers for all archived articles on Lucy Guerin

Samuel James

Where most artists are tangled within postmodernism my work remains in phenomenology—pursuing the connections between perception and material—or literally between video and performer. My concern is how all of our mediums—body, films, sound—are related. I have been reading lots of secret things, things that exist under the veils of reality and things that are the veils of reality: Victoria Nelson’s The Secret Life of Puppets (2001, when I was working with puppeteers) and in the last two years The Secret Life of Plants (Tompkins and Bird, 1973) and also the profound Rinrigaku by Watsuji Tetsuro (1937). In my videos I was compelled to take work beyond the performer and object to the plant universe and the inanimate. This has helped deepen my understanding of body and matter and what we are actually filming.

Merleau Ponty’s intertwining of perceiver and perceived for me still encapsulates indefinable existence, an endless, churning assemblage of things in more or less proximity and awareness to an individual. Being conscious of the actions and processes of video, when I film something, I film whilst knowing I am filming, yet I am also presently in some ways not-filming, drifting into distractions, smells, noises, physical interactions which make the capturing of a performance an unending and complex activity. For me, this aesthetic research reveals how the tools become a mirror reflecting the subconscious. Media is inextricably bound up with perception and fed back into external phenomena. As Deleuze says, the actual comprises nothing more than clusters of virtuals—all by-products of our own presence and life-making. Video art is nothing more than pulling out and isolating some of these events.

Just as important as the video itself, the screen experience is also about the narcotic, cinematic, performative space, where the witnessing makes possible the offering of one’s own dreams into another’s dream. Where every action in an artwork or characters in a film are seen as the same actions you are living through this very day, in this moment. The life in the cinema is transposed into the viewer’s. Video and materialism are bound in a way that produces an event that says nothing but we understand it totally and vividly as our own, it becomes embodied as part of us.

http://www.shimmerpixel.blogspot.com.au

Related articles

Processing paradoxes

Fiona McGregor: Samuel James, Ms & Mr, Artspace

RealTime issue #99 Oct-Nov 2010 p54

Night works

Ella Mudie: Bec Dean, Nightshifters, Performance Space

RealTime issue #99 Oct-Nov 2010 p51

Space-maker

Keith Gallasch: Sam James, theatre & media designer

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 p44

nova Milne

nova Milne, 1) Jete 2) There There Anxious Future, 3) Xerox Missive

courtesy the artists

nova Milne, 1) Jete 2) There There Anxious Future, 3) Xerox Missive

It took an aging French philosopher to reinvest in the existential problem of love. Alain Badiou’s In Praise of Love (2009) emancipates love from the dumb simplicity of inward-looking narcissism. Instead, it can be a radical construction: a project formed no longer from the perspective of one, but through the lens of difference and infinite subjectivities. It emerges as a way of thinking that privileges risk, chance, reinvention and a new way of experiencing time. Badiou’s notion of enduring love is really about locking a chance encounter into the framework of eternity, an event that is returned to, but always displaced and re-declared afresh. We imagine that as the loop passes, it reinvents itself.

We’ve been collaborating informally since 1998, including with the generic conjunctive title Ms&Mr since 2003. Through a range of forms such as large-scale video assemblages and installations, we create moments of connection or disruption that often take the form of an abstract encounter across the breach of time. Orlando, the novel by Virginia Woolf (1928), its title character and Sally Potter’s film adaption (1992), have been in our heads since we were teenagers. It’s a strange love letter that seems inspired by the theory of relativity.

Philip K Dick’s Ubik (1969) represents time spatially (and comically psychedelic) in an imagined future of 1992. One character, Glen Runciter, repeatedly visits his dead wife (suspended in cold-pac) as she continues to offer corporate advice through telepathic communication. In our XEROX MISSIVE we had Dick’s living fifth ex-wife commune with the deceased author from the future (as he predicted) by visiting his 1977 self in documented footage form.

In the original COSMOS series (1980), Carl Sagan stands like a monk by the sea, elucidating in his dulcet, melancholic tone. In episode 8’s thought experiment on Time Dilation, a kid leaves his friends on a park bench, taking a short ride on a bike that travels near the speed of light. From his perspective, a few minutes pass, but he returns to find that, for his friends left behind, time flowed at its usual rate and they have since grown up and died. His brother remains waiting, now an old man, and their gaze meets across the bridge of time that now separates them.

http://www.novamilne.net/

Related articles

Remembering future lives

Gail Priest: Ms&Mr, Xerox Missive 1977/2011, AGNSW

RealTime issue #107 Feb-March 2012 p46

Video art now through the lens of then

Urszula Dawkins, Channels Video Art Festival

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 web

Processing paradoxes

Fiona McGregor: Samuel James, Ms & Mr, Artspace

RealTime issue #99 Oct-Nov 2010 p54

Soda_Jerk

1) Soda_Jerk; 2) Hito Steyerl, Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File, 3) Parliament – Funkentelechy Vs. The Placebo Syndrome, 4) Microsoft Windows 95 Video Guide

Whether we’re working with video, lecture performances or cut-up texts, a kind of errant pedagogy is fundamental to our practice. The sources we’ve selected here also share an educational impulse that’s gone wayward.

Hito Steyerl – How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File (2013)

How Not to be Seen… takes the form of an instructional video on how to remain invisible in an age of image proliferation. Equal parts Harun Farocki, Monty Python and post-internet art, this work manages to occupy the treacherous territory between the absurd and awesomely astute. So digital politics. Much entertainment value. Very respect.

Parliament – Funkentelechy Vs. The Placebo Syndrome (1977)

The third instalment in Parliament’s epic concept album trilogy, this LP sees the Starchild educating listeners on how the forces of uncut funk can be deployed in a fight for freedom. At stake in this intergalactic P-Funk mythology is a sharp critique of the socio-economic conditions of the late 1970s. Along with Sun Ra these guys delivered us our first schooling in the secret powers of combining social politics with speculative fiction.

Microsoft Windows 95 Video Guide

Sometimes the most ingeniously bent educational formats are deadly earnest in their intent. Research for our new lecture performance Netsploits has us deep in VHS tapes of 1990s operating system manuals and internet instructional videos. Special mention must go to Microsoft Windows 95 Video Guide which bills itself as “the world’s first cyber sitcom” and stars the best friends we never had: Jennifer Aniston and Matthew Perry.

We will be going errant educational in our upcoming AGNSW Contemporary Project 3 Live Video Essays. Over consecutive Saturdays in November we will perform three video lecture performances including The Carousel (2011), Netsploits (2014) and Terror Nullius (2014).

http://www.sodajerk.com.au

Related articles

Studio: The Carousel

RealTime Studio, online August 23, 2011

Upgrading and evolving

Sarah Pirrie, Videodromo 1.5 At 24hr Art

RealTime issue #78 April-May 2007 pg. 27

Cyber-conceived/cyber-birthed

Christy Dena on making & distribution at Destfest

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 p22

Sam Songailo

Sam Songailo, Digital Wasteland, CACSA

photos Emily Taylor

Sam Songailo, Digital Wasteland, CACSA

I’ve always loved the background art in sci-fi, particularly in Anime. The Anime series: Space Adventure Cobra (1982) contains in my opinion some of the best. The world seems to be made of metal interspersed with colourful lights, patterning and oversized computers performing some mystery function. The background art continually threatens to steal the show. I like to think of my installation work as the background art for something else that has or will take place. When I started painting I was trying to recreate these backgrounds. What I ended up producing was nothing like it. That initial trigger created a series of paintings leading up to where I am at today. Now it feels like my practice has a life of its own.

Through the look of the work I am seeking to reproduce a certain fictional atmosphere, which I would best describe as the emptiness of being inside a computer game. The first game machine my brother and I owned was a Commodore 64. The tape drive was unreliable and often we would spend hours trying and failing to load games. Eventually we would get one to work and it was kind of magical when it happened. Sometimes a ‘crack intro‘ (see 64 legendary examples) by the team that pirated the software would load before the game. Typically they consisted of colourful graphics, bouncing letters and an accompanying SID tune (SID was the name of the sound chip). The graphics on the 64 were low resolution and really forced game makers to be creative. I remember these crack intros having some of the best graphics at the time.

I have recently completed a couple of exhibitions. The first at Alaska Projects as part of the SafARI festival and then the exhibition Digital Wasteland at the Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia. Both large scale painting installations. Currently I am finishing off a mural in West Footscray and working on an exhibition opening in July at Hugo Michell gallery (http://www.hugomichellgallery.com/). Finally I am working on a commission for a university which will be completed late this year.

http://www.songailo.net

Sam Songailo’s Digital Wasteland will be reviewed in RT121.

Lindsay Vickery

1) Lindsay Vickery, 2) Silent Revolution, detail (2013), 3) Nature Forms I, detail, (2014)

courtesy the artist

1) Lindsay Vickery, 2) Silent Revolution, detail (2013), 3) Nature Forms I, detail, (2014)

Chris Hedges and Joe Sacco’s book Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt (2013) has been hovering over a lot of what I’ve been making lately. It’s a confronting look at where society is heading (and already is for some): the final pages are as heart- and gut-wrenching as anything I’ve read. The combination text/“graphic reportage” they use was a big influence on the visual style of my recent works Silent Revolution and Sacrificial Zones.

I think the creative response and energy around the Occupy movement, artists like Molly Crabapple et al (http://mollycrabapple.com), has started a kind of community of intention that hasn’t been around for some time. I’ve also been following the work of this New York composer Bil Smith, an enigmatic Luther Blissett kind of character, who has been publishing these amazingly unrestrained scores incorporating notation, graphics, photographs, data visualization and so on.

In particular this year, I’m looking closely at the boundary between representation of sound and image, partly through some experiments with eye-tracking technology, but also with some new works involving sonfication and visualisation (and re-sonification of visualisations and vice versa). My interest in this is an outgrowth of the ‘screenscore’ works we’ve been doing with Decibel, but also some other things: Peter Ablinger’s Quadraturen series that explores the distortions that occur as a result of translation from one medium to another, and Manuella Blackburn’s compositional approach using visualised sound shapes. For example, in my recent works Nature Forms I, three performers and a computer sonify images derived from trees, rocks etc, with differing degrees of fidelity/freedom; and in Lyrebird, software I’ve made for Vanessa Tomlinson’s 8 Hits program, field recordings are transcribed in real time into a ‘score’ that she can play or improvise with. This has led to some interesting questions about innate associations between colour and shape, some of which have been answered by the interesting work at Stephen Palmer’s Visual Perception Lab in Berkeley 9 into “weak synaesthesia,” the sort of cross-modal correspondences that naturally make us group light, high and bright together.

www.lindsayvickery.com; http://lindsayvickery.bandcamp.com

Related articles

Man-machine music

Sam Gillies: The Mechanical Piano, Waapa

RealTime issue #107 Feb-March 2012 p40

Soundcapsule #2

Hope & Vickery, Ughetti, Gorfinkel

Online exclusive March 6, 2012

Earbash: Decibel

Disintegration: Mutation

Online exclusive, May 24, 2011

Julie Vulcan

1) Julie Vulcan, 2) Drift, 3) Wishing Dark

photos Michael Myers

1) Julie Vulcan, 2) Drift, 3) Wishing Dark

The current series of work I am developing is Wishing Dark and this has led me to revisit some cult classics from the 1970s and 90s: Neal Stephenson’s sci-fi novel Snow Crash (1992), Wim Wender’s epic film Until the End of the World (1991), Alex Proyas neo noir thriller Dark City (1998) and Andrei Tarkovsky’s enthralling Solaris (1972).

I have been exploring themes of sensory deprivation, what makes us resilient and the thin line between what is real and what we perceive to be real. All these have echoes in the book and films above. Reading and watching these classics again affirms how close some of the ideas are to current neuroscientific research which influences some of my investigations, especially around visual perception, hallucination and how our brains fill in the gaps.

Some of the themes might seem dark and a bit gloomy: existential crisis on a space station; amnesia, murder and time/memory manipulation; dream addiction; language as virus. Well they are dark, both literally and figuratively and that is my interest. Dark = Manifestation. It’s not particularly a new idea but I am interested in this idea of self-implosion as survival—a path to mind expansion.

I am also a bit enamoured of the 1960s/70s futurism aesthetic—it was so hopeful…and silver. This filtered into my new work Drift at the recent Festival of Live Art (Melbourne) and Metro Arts (Brisbane). The predominance of silver and lime green in the installation was my homage to that era. The work on one hand seemed to present a nurturing haven offering some time out, but on the other it was highlighting how we hold onto small gestures in the face of uncertainty. What courage does it take to step into our space pod and warp our view to survive?

http://www.julievulcan.net

Related articles

Do you want me to touch you?

Madeleine Hodge, SPILL Festival of Performance

RealTime issue #115 June-July 2013 p12

Celebrating the body: plasticity & mutation

Kathryn Kelly: exist-ence 5, festival of live art, performance art and action art

RealTime issue #116 Aug-Sept 2013 p40

RealTime issue #120 April-May 2014 pg. web