Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

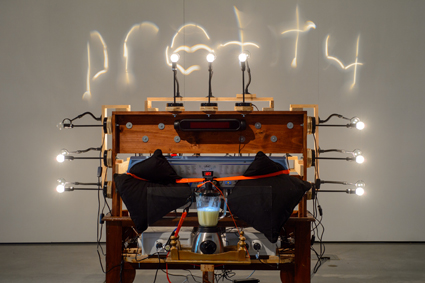

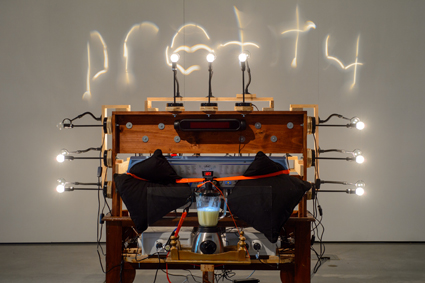

James Nightingale, Voyage Through Radiant Stars, Aurora New Music Festival

courtesy Aurora New Music Festival

James Nightingale, Voyage Through Radiant Stars, Aurora New Music Festival

The first half of the opening night of the 2014 Aurora New Music Festival in Sydney’s west sparkled with variety and invention while the second half introduced us to a major new work, Brian Howard’s Voyage Through Radiant Stars, which shone obsessively with cosmic aspirations.

The immediately engaging concert opener was Marcus Lindberg’s Ablauf (1983/88; Finland) featuring clarinettist Jason Noble in rapid vertiginous flights from raw depths to lucid heights while positioned between the emphatically slow-paced boom of two bass drums (Claire Edwardes, James Townsend). In the end, after a moment of silence there emerged sibilants, sharp consonants, soft drum beats, like distant thunder, final flourishes and a single full-breathed exhalation from Noble.

Ekrem MuLayim’s Sonolith (2014, Australia) is an aural and visual response to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights for piano (Roland Peelman) and projections (MuLayim, Mic Gruchy): “certain pitches are ascribed to certain letters, certain chords to certain words and certain melodic phrases to key words or word groups” (composer’s program note). On three long screens, the words appear in various patternings almost simultaneously with the notes, as if the pianist is typing them (an impression reinforced by recurrent dings, piano slaps and cries). The outcome is a flexible minimalism now and then powered by a fluent, assertive stride (from 20s American jazz pianism) or disintegrating into near discordancies.

The inclination of composer and pianist (who is given room to freely interpret) is not seemingly programmatic although Clause 5 on Torture is stressfully fast and high pitched, Clause 7 on Discrimination threatens to break up, 11’s Presumption of Innocence strides proudly and in 14, on Asylum, the loud pedal is held firm on deep notes beneath those rushing on above, as if hope is disintegrating. Associations are fleeting but inevitable in an ambitious and audio-visually potent work (convincingly played by Peelman) although the composer’s commitment to illuminating all the clauses of the charter with a limited sound palette and a lot of reading proved a tad taxing in the long run.

Claire Edwardes, Aurora New Music Festival

photo courtesy Aurora

Claire Edwardes, Aurora New Music Festival

Iannis Xenakis’ Rebonds A/B (1987-89, France) is a work for percussion in two resonating movements. The first, A, has a dance-like compulsiveness, its deep beat soon overlaid with a multitude of improvisation-like, increasingly rapid-fire flourishes until it finally slows to a hesitant if emphatic halt. B feels less complex with its open pattern on drums and then on woodblocks; then it’s back to the drums at a steady pace but with some fast counterpointing. Pause. The woodblocks chirrup and are joined by the drums in a race to the finish. Both movements are finely articulated, played as ever with Edwardes’ capacity for finesse and passion—Xenakis’ music might be conceived in part algorithmically but she makes its beauty self-evident.

Sydney composer Alex Pozniak paired virtuosic dijeridu players Mark Atkins and Gumaroy Newman in his new work Blow by Blow, focusing on the drone potency of the rich sonic textures offered by these traditional instruments. Alongside the anticipated sounds of animal and bird cries, cars and aeroplanes, soft sssh-ings and Atkins’ vocals we hear strikingly high, long sustained horn-like notes, pulsating deep beats and surprising (and recurrent) glissandi. Each player handles three instruments, swapping from one to another, introducing new layers of sound at once familiar and strange—as if not coming from dijeridus at all. At the end the players slip into improvisation, merging with the distant offstage strings of two members of the Noise Quartet.

Brian Howard’s Voyage Through Radiant Stars (2013, an Aurora Festival commission) with its constant ascending flights felt more often cyclical than linear, each star (one per movement within its “radiant constellation”) evoked as if like any other—save in degrees of luminous intensity or aural mood, including passion or awe as brass and percussion repeatedly and thunderously grounded the work with an emphatic motif often at the beginning of movements and then later in each. Against this deep tremulousness, as if in flight from it (or like lines of radiating light), is the saxophone (James Nightingale), variously solo, placed within the 18-strong ensemble or before it as in a concerto—which the overall work is not, at least not conventionally.

The compositional motifs in the sax solos and ‘concerto’ movements evoke the traveller more than they do the stars. There’s a greater freedom than felt in the gravitational pull of the brass. Indeed there are movements when the saxophone seems to draw the ensemble up with it—the drumming accelerates, oboe, clarinet and brass scale upward, the strings echoing the saxophone’s ascending dance.

Howard and Nightingale exploit much of the saxophone’s range—pure, whistling, staccato-voiced, jazzy, guttural and striving and soaring to ever increasing heights before commencing its flight yet again, but with little suggestion of fall or defeat despite the ensemble rumblings beneath. It is the characterful saxophone, in a work of some 60 minutes, that keeps Voyage Through Radiant Stars luminous, in a journey in which the saxophone is itself a star or, elsewhere, part of one or even absent, just listening, when one star is solely represented by a sinuous string quartet. This is an epic work, needing firmer acquaintance and perhaps greater concision, but on first hearing superbly realised by James Nightingale, conductor Daryl Pratt and the Sydney Conservatorium Modern Music Ensemble.

The Aurora New Music Festival’s opening night proved to be memorable, programmed with fascinating new Australian works that innovated with text and piano, the dijeridu and the relationship between saxophone and ensemble. The long first half of the concert did put Voyage Through Radiant Stars at risk; my attention certainly wavered, partly because the work’s patterning became hypnotic however varied it was in the detail. If deserving a stand-alone outing, its premiere performance was nonetheless welcome and highly significant. Thank you, Aurora.

Aurora New Music Festival 2014, Opening Night, Aurora Artistic Director James Eccles, Riverside Theatre, Parramatta, 30 April

RealTime issue #121 June-July 2014 pg. 46

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Winds of Woerr, Ghenoa Gela

photo Gregory Lorenzutti

Winds of Woerr, Ghenoa Gela

Next Wave is an ambitious festival—a major, well-funded biennial curatorial project which commissions and develops innovative work by young artists (notably through its Kickstart program). The final works, unveiled only at the festival, are often variable in their execution. This, I have come to realise, is legitimate. The level of risk involved in working with very inexperienced artists on extremely ambitious projects is extremely high, and it is part and parcel of the project that the whole experience can feel very hit-and-miss. As the statement of intent for 2014 said: “We support what is attempted over what is achieved.”

2014 Next Wave, however, was the most even I have yet experienced. Not only was the quality of the work high overall, but the program was presented in a very cohesive manner, thanks in no small measure to Emily Sexton’s strong curatorial steering. This was Sexton’s second Next Wave, and her customary attention to detail was visible at every step: in day tickets tailored to various audience profiles, a well-considered talk program and two excellent publications. The heart of the festival was BLAK WAVE, a festival within a festival, incorporating seven works by Aboriginal artists that in various ways questioned the place of Aboriginal art, a series of talks and its own book.

BLAK WAVE

Perhaps the most notable thing about BLAK WAVE is that it happened in the first place. Sexton’s foregrounding of Aboriginal art and artists in the context of new, emerging, urban and experimental art made a very strong statement about the place Aboriginal artists should occupy in Australian culture. Through talks and the book, BLAK WAVE also created its own critical and analytical commentary, forging a nuanced, discursive context not likely to manifest in mainstream media. The entire project was simply extraordinary in its scope, both educational and emancipatory.

The inclusion of so many Aboriginal events radically changed the feel of the festival, and, in a certain sense, our expectations of contemporary art and performance. In Melbourne, a southern city, Aboriginality is not very visible. Yet at Next Wave we were introduced to an alternative reality, in which every evening we were welcomed to country—did you know how varied is the traditional ownership of inner-city Melbourne?—with elders praising young artists and speaking about the importance of contemporary art—when is the last time you have seen an elderly Australian of stature, a non-artist, speak from the heart about the importance of contemporary art for our culture? Here a performance was first and foremost a social event, a gathering, where we were welcomed as guests, not simply as paying customers. For a little while, BLAK WAVE created an alternative Australia, an Australia that could have been, and may still come to be, in which hatred, ignorance and fear were bridged over by gestures of generosity; in which silent gaps in our history were filled with stories; and in which our own history of art expanded to connect ancient traditions and the cutting edge of the present. It offered an immense gesture of healing.

Winds of Woerr

Ghenoa Gela, an accomplished dance performer, devised Winds of Woerr to introduce a traditional Torres Strait Islander story of the four winds, whose influence shapes the climate more than the notional four seasons. It opens with a greeting, a cup of tea and the voice of Gela’s mother Annie correcting her daughter, instructing her on how to properly conduct the performance. The dance theatre piece unfolds with four performers (two Indigenous, two not) each representing a wind with a mask and a prop. They are the four sisters Kuki, Sager, Naigai and Ziai. It is impossible to critique Winds of Woerr through the prism of Anglo-European performance history because it is not yet integrated into that experience, but is here brought to life as pure cultural material, to be shared, spread and saved from extinction. The beauty of the work is primarily in the texture of its culturally specific material: a yarn from Creation Time, narrated through Islander movement, sound and costume.

White Face

Carly Sheppard’s White Face, a predominantly abstract duet between Sheppard and non-Aboriginal dancer Ryl Harris, was easier to read as a dance piece in the conceptual/formalist Anglo-European tradition. It explores the experience of a fair-skinned Aborigine—the cultural dislocation and gaps, the ungrounded sense of identity, the loss, the insecurity. Sheppard covers her face, rubs her skin with white powdered sugar, wrestles with Harris and compares their shades of fair skin side by side in a powerful gesture of uncertainty. At the height of tension, the work breaks out of solemn silence and abstraction. Sheppard becomes ‘Chase,’ and tells us how, “When I discovered I was an Abo I was bloody ropeable…But, like, I thought about it ‘n I realised that it all makes sense coz I’ve always been real spirichulle…After I found out I went straight down to Cenners to claim me cultural heritage…you know like free house, free car, free Abo money.” The extremely harsh caricature is powerfully accusing, reclaiming discursive ground without ever becoming complicit.

Jesse Hunniford, Concerto No. 3. Sarah-Jane Norman

courtesy the artist

Jesse Hunniford, Concerto No. 3. Sarah-Jane Norman

Concerto No. 3

Sarah Jane Norman’s Concerto No. 3 moved away from Aboriginal identity to address failure. Norman, formerly a prodigious pianist, sets an impossible task. Rachmaninoff’s Third Piano Concerto is considered one of the most difficult piano pieces ever written (even the performer for whom the work was originally composed refused to perform it in public). For 12 hours straight, six non-virtuosic performers (former pianists, post-prodigies) attempt to sight-read the concerto, one at a time, in a dark and solemn Melba Hall at the University of Melbourne Conservatorium of Music.

Immediately on arrival, I realised what a mistake it had been to assume I could see other shows around this performance. Next Wave 2014 is for me marked by regret at not having spent 12 hours in Melba Hall. For spectators without classical music training, this was a work of incidental sound art. But for spectators aware of the intense physical training and sports-like culture of classical music, Concerto No. 3 was like watching an extreme sport in which all our anxieties were realised: like seeing a tightrope walker endlessly fall and climb back up, or a high-jumper repeatedly dislodge the bar—and, say, break an arm. The intense focus and effort of pianists struggling through “Rach 3” put this performance on a par with some of the most involved dance improvisation pieces I have seen.

New Grand Narratives

The theme of the 2014 festival was New Grand Narratives, somewhat vaguely described as “potent visions of a new world, and the relationships within it.” Sexton accurately noted the cracking of old institutions and old ideas. However, the artists did not respond with the same political perspicacity. Indeed, the most overtly political works were not very interesting, reflecting the broader problem the new generation of young Australians has with envisaging possibilities for political engagement. The biggest offender, however, was Dutch outfit New Heroes with Club 3.0, a combination TEDx talk and Fight Club.

Club 3.0

There were four parts to Club 3.0. It opened with a list of well-known collaborative, creative, make-world-a-better-place initiatives that sit halfway between urban design and performance: Reclaim the Streets, local currency initiatives, Park(ing) Day and one very entertaining spoof. It launched into a full-blown retelling of Fight Club, culminating in an actual tournament between audience members. Amazingly, even the hipster, late-night Next Wave audience was inspired to fight amongst themselves, roused by the two performers’ passionate call for action and finding meaning. Had it all ended there, it would have been the best work of the festival. Instead, we were then encouraged to renounce literature and philosophy (this did not work well, probably because the weight of culture is lesser in Australia than in Europe) and were finally sent out into the cold, to receive a non-committal phone message about already knowing all there is to know. I have rarely seen a work rise to such powerful rousing of emotion and agency and then fall into such non-committal disappointment. Club 3.0 managed to deploy all the neo-fascism present in Fight Club, with the very neo-liberal, free-market fallacy of choice that it purported to resist.

New feminism

However, a new grand narrative did emerge at Next Wave 2014: new feminist performance. There has been an undeniable renaissance of feminist thought and activism in the last few years globally, but more so in Australia than elsewhere (probably fuelled, in part, by the horrific treatment of Julia Gillard and the murder of Jill Meagher in 2012). Combined with strategies to increase the presence of women in theatre roles, undoubtedly the most interesting work around Melbourne in the past few years has been made by women. Female performance-makers at Next Wave presented work that was not only thematically, formally and politically world-class, but exceptionally innovative, original and deeply imbued with Australian sensibility. In fact, its major innovation is that it transcends the label of ‘feminist performance.’ It is unmistakably made by women and politically progressive, but it is not overtly ‘about’ gender anymore.

Natalie Abbott, Donny Henderson-Smith, MAXIMUM

photo Sarah Walker

Natalie Abbott, Donny Henderson-Smith, MAXIMUM

MAXIMUM

Natalie Abbott’s MAXIMUM exemplifies this shift most thoroughly. It starts off as a unison dance of two bodies: Abbott’s young and dancerly and Donny Henderson-Smith’s that of a bodybuilder. There is running: circular, across corners; the performers are already visibly exhausted by the time they move onto squats, which expand into lunges, push-ups, twerking, and a whole series of other actions not found in classical ballet. MAXIMUM is conceptually extremely simple: an endurance work stretching two dissimilar bodies to their limits. Halfway through the 60 minutes, the audience is already uncomfortable. In the last section Henderson-Smith lifts Abbott, who assumes the dignified, supplicant pose of a Greek statue; yet both of them keep falling. It is almost unbearable to watch. (The person sitting next to me started shaking uncontrollably.) However, the concept is executed so thoroughly that its meaning comes from a formalist contemplation of how the material (body) is reacting to form (physical stress). At the start, it appears to be a confrontation between an artist and a sportsman. As little signs of fatigue add up (millisecond delays, beads of sweat), it becomes increasingly clear that Abbott, while smaller, is the stronger of the two, foregrounding the invisible labour inherent in art-making. However, as both bodies reach their limits, confrontation becomes camaraderie, and the central question not so much which one will win, but can they push through. A ballsy, yet humble work, which will soon be performed at the Avignon Festival in France

OVERWORLD, Sarah Aiken and Rebecca Jensen

photo Gregory Lorenzutti

OVERWORLD, Sarah Aiken and Rebecca Jensen

OVERWORLD

Sarah Aiken and Rebecca Jensen, young choreographers associated with Abbott, presented the other dance highlight: OVERWORLD. It is an extension of their work Deep Soulful Sweats (which I missed): a participatory, audience-centred combination of dance, yoga and ritual. It brings together movement vocabulary, visual and thematic references and performance practices spanning Kundalini yoga, neo-pagan rituals, contemporary witchcraft practices (à la Buffy the Vampire Slayer), elements of the Zodiac, bush doofs, creation myths and unabashed silliness. OVERWORLD has a gleefully sprawling structure like the beginnings of multi-cellular life: the four performers dividing the audience into elemental groups based on the horoscope; dressing-up and tearing each other’s clothes off in a beautiful, intelligent reference to creation myths across the globe; guiding a meditation session; and finally, as traces, disappearing into a screen, singing and dancing in preparation for a night out.

In the central sequence, once the performers have torn each other’s clothes off while shrieking and wielding their smartphones, one of them remains, totally naked. The lights dim, she lies on the floor and the smartphones are put into glass jars. It turns out they were used to record the action, which is now replayed. The girls’ shrieks now sound eerie, resonating with associations of rape and other violence. Amid it all, the naked performer slowly and sexily eats an ice-cream. One does not necessarily have to know that the central moment in most creation myths is the rape of an Earth goddess to fertilise and create life in order to appreciate how masterfully the point is made about the cultural milieu in which we live.

I admired enormously how unafraid OVERWORLD was to claim supposedly trivial, ‘girly’ concerns and aesthetics. The puzzlement with which it was greeted reminded me of the dismissal of Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries (youngest-ever recipient of Man Booker Prize in 2013) because of its low status genre (Victorian thriller) and its structural basis in something as ‘unserious’ as the Zodiac. Like The Luminaries, OVERWORLD heralds a new aesthetic in high art: maximalist, freely mixing high and low references, unapologetically feminine, silly rather than stern, but thoughtful.

Madonna Arms

photo Sarah Walker

Madonna Arms

Madonna Arms

The only text-based work among those by women at Next Wave was Madonna Arms by I’m Trying To Kiss You. Critics were extremely confused, calling it unclear, but I thought it was the most exciting staging of new writing I have seen in Melbourne in a long time. Madonna Arms is a postdramatic text. The first half builds a cacophony of overlapping voices, freely blending media messages, small talk, and the subconscious—reminiscent of Elfriede Jelinek’s plays in which language becomes disembodied material with its own, depersonalised force (“Sprachflächen” or “planes of language”). Madonna Arms overlaps the sex-and-violence of popular culture with the vicious sublimated misogyny of ‘female interest’ magazines and celebrity gossip. At one point, we hear the voice of someone fleeing her house to escape danger: “I am running in a/ Bright white nightgown that clings to my/ Firm breasts/ I glow against the burning sky /Flying /A bullet!” The staging goes against the grain of the text, creating its own demented reality: women in bathing suits and boxing robes stand in front of a greenscreen, eschewing character, realistic setting, or dialogue, in favour of an abstracted work of pure theatre.

The second half, however, is a parody of naturalism: an ultra-macho fantasy of world rescue by three bureaucrats all named Martin, performed in drag. Here, again, an initially dark lament against sexism turns into an irreverent, gleeful counter-attack on patriarchal nonsense. It shifts from anger to a very Australian kind of ridicule. Theatrically interesting while clearly text-focused, I thought Madonna Arms signalled a major new force in Australian playwriting, picking up the kinds of inquiry that Black Lung championed in Melbourne a few years ago. Indeed, I am curious as to why Black Lung never met with the misunderstanding that greeted I’m Trying to Kiss you—their aesthetic is very similar.

Smell You Later

One small, humble work deserves a mention. Katie Lenanton’s curated installation Smell You Later became, unexpectedly, one of the great joys of the festival as well as one of the strongest devices binding the whole experience. Grace Gamage and Olivia O’Donnell’s scent sculptures were pure sensuous joy: sweet-smelling, melting mounds shaped like candy, cakes, sea shells or just pastel-coloured lumps made out of oils, soap, scrub, glitter and occasional edible stuff (glace cherries, for example). These were installed near washbasins in bathrooms of participating venues, which meant that a regular Next Wave audience member constantly ran into them when least planning to encounter art. There was something extremely satisfying in being able to freely touch, mould, scrub and scrape, taste, rub on oneself and wash off, and then offer oneself to other people’s noses in the foyer. This repeating solitary game became one of the experiences echoing through the festival, bringing together inner-city galleries, town halls, a suburban substation and other varied venues under the coherent experiential umbrella of Next Wave.

Next Wave 2014, director Emily Sexton, Melbourne, 16 April–11 May

RealTime issue #121 June-July 2014 pg. 34-35

© Jana Perkovic; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Bastard Territory

photo Kerrin Schallmeiner

Bastard Territory

Colonialism, sexual politics, the beginnings of Papua New Guinea’s independence and family and identity are all in the mix in Stephen Carleton’s new play Bastard Territory. It is an engaging three-act drama that moves between three time zones and two countries as it explores the life of Russell who is searching for the truth about his parentage and in so doing reveals the culture and politics of life in PNG in 1967 and Darwin in 1975 and 2001.

The play opens with Russell (Benhur Helwend) addressing the audience directly—introducing and watching his memories come to life—and then becoming part of the action. As narrator, he poses questions to the audience as he tries to find out who his biological father is. Russell is a direct link between audience and storyline, passing wry comments on the action throughout. Helwend’s pleasure and easy engagement as narrator led to some audience members responding verbally on opening night.

The playwright’s dry humour underpins the action across all time zones, exposing political corruption, homophobia and racism while revealing the circumstances and vulnerabilities of their perpetrators, who are never excused. In Darwin in 2001 we see characters repeating some of the mistakes of the older generation and grappling with the same issues but the outcomes are different. Some issues are re-cycled through the generations revealing how little times have changed.

Kris Bird’s set, beautifully lit by Sean Pardy, is a skeletal framework of a typical elevated tropical house offering director Ian Lawson multiple playing spaces. The framework has a door but no walls, giving weight to the idea that ‘truth will out’ and adding to the sense of claustrophobia as members of the colonial community watch each other closely. The unfinished house echoes the notion of PNG in 1967 as a place in transition and the set transforms easily from PNG 1967 to Darwin 1975 until finally in Darwin 2001 it becomes a “hip urban café and art gallery by day, queer cabaret dive by night” (Carleton, program note). Now dressed in a tight-fitting sparkly black frock and dancing to Shirley Bassey, Russell parades on the upper level as the drag queen his father cannot accept.

Bastard Territory

photo Kerrin Schallmeiner

Bastard Territory

Kirsten Faucett’s costumes are a gorgeous celebration of colour and playfulness as she reflects the various eras. Ian Lawson’s direction is tight with smooth transitions between time zones and styles melding narration and action with brief choreographed dance routines. The sound design by Guy Webster is a strong element of this production with the three eras delineated by the popular music of the time.

Audiences have become less used to three-act plays but Bastard Territory holds us with its combination of good writing, comedy, diverse theatrical elements and strong performances from all the cast. Kathryn Marquet as Lois transforms from the young hopeful newlywed to a bored wife desperate for diversion to an embittered woman trapped in her own life. She is powerful in the role and handles well the playing of different ages. I was disappointed to have her story end with a sudden disappearance—I wanted to know more about her departure and subsequent brief return.

Peter Norton gave depth to Neville junior, Russell’s adoptive father, and later transformed into the role of Russell’s boyfriend and unwitting father of a child. Veteran actor Steven Tandy played Neville senior, the elderly father who finally comes clean about past acts committed in PNG and who comes to some form of acceptance of his adoptive son’s sexuality.

Suellen Maunder’s heightened comic character Nanette is played with great craft and obvious relish. The audience were too afraid not to answer her school mistress “Good morning!” Although the role is a deliberate caricature, Maunder brought veracity to it, allowing the audience to connect with Nanette’s vulnerable side. Benhur Helwend played multiple roles—all the Papua New Guineans and, as he pointed out, the three possible fathers as well as the son.

I believe it is difficult and rarely successful when adult actors are required to play children and the heightened style chosen for the young Russell and his friend Aspasia was stereotyped. I was relieved when they grew up and resumed their friendship as adults in Darwin 2001.

Bastard Territory is a well-crafted, intelligent and entertaining new Australian play. As Stephen Carleton says in the program notes it’s not only a play about searching for roots and identity but it also asks larger questions about Northern identity: “are the NT and the former Australian ‘territory’ of Papua New Guinea the illegitimate offspring of the larger host nation? Are we as Northerners the bastard children of a perceived national nuclear family or norm? I hope so.”

Knock-Em-Down, Brown’s Mart Productions and Jute Theatre: Bastard Territory, writer Stephen Carleton, director Ian Lawson, performers Ella Watson-Russell, Suellen Maunder, Benhur Helwend, Kathryn Marquet, Steven Tandy, Peter Norton, designer Kris Bird, lighting Sean Pardy, sound design Guy Webster, choreography David McMicken; Browns Mart Theatre, Darwin, 7-18 May; Jute Theatre, Cairns, 6-21 June

RealTime issue #121 June-July 2014 pg. 36

© Nicola Fearn; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Dalara Williams, Wulamanayuwi and the Seven Pamanui

photo Lucy Parakhina

Dalara Williams, Wulamanayuwi and the Seven Pamanui

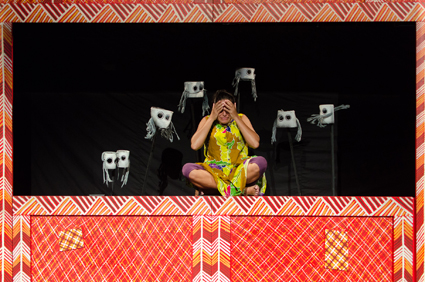

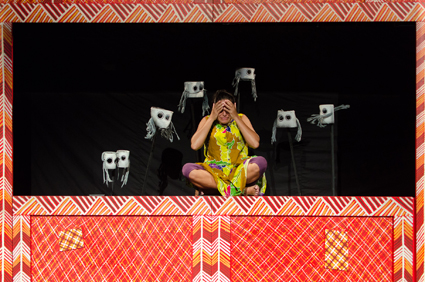

Wulamanayuwi and the Seven Pamanui is a delightfully bonkers theatrical fusion of Tiwi Island Dreamtime stories and characters, pantomime, fairytale, drag, song, puppetry and visual projections.

The narrator, Jarparra the Moon Man (Jason De Santis), introduces us to Wulamanayuwi (Dalara Williams), a young girl and daughter of the Rainbow Serpent totem, who is having trouble at home—her warrior father Jipmarpuwajuwa (Kamahi King) plans to marry her off to a stranger and her evil stepmother, Jirrikalala (performed with gusto and lots of evil cackles by Natasha Wanganeen), is plotting against her.

When Jipmarpuwajuwa goes away he leaves Wulamanayuwi as ‘boss.’ She sets off hunting but instead of arriving at her usual lush hunting grounds she is surprised to find a black and burnt land. Luckily a white cockatoo guides her to bush apples and she returns from the hunt laden with food. Jirrikalala, jealous of the clever daughter, decides to kill Wulamanayuwi and her seven brothers (embodied by seven Tiwi designed puppets) and so seeks counsel from an Evil Spirit of the Water (played with drag queen theatrics by Jason De Santis). The two come up with outrageous and murderous plans. Most don’t work out but one hot day, when the brothers go swimming with their sister, the Water Spirit drowns them. Wulamanayuwi is blamed for their deaths and is exiled from her family and country. Bereft, she journeys to a magical land where she meets the Seven Pamanui spirits (not unlike her drowned little brothers), beings out to seek revenge. Later, she eats food from an old woman (Jirrikalala in disguise) and seemingly dies. Her promised husband Awarrajimi (Jaxon De Santis) turns up, tries to revive her, but can’t. The white cockatoo, however, materialises in time to save Wulamanayuwi.

By the end of the play order is restored to the family and the land. Deftly written by Jason De Santis, ebulliently directed by Eamon Flack, quirkily designed by Bryan Woltjen, with AV by Sam Routledge (who was also the puppetry director), Wulamanayuwi and the Seven Pamanui was performed with zest, a whole lot of cheek and a gleeful sense of anything goes. This is a creative team unafraid of mixing Tiwi Island traditional story with European fairytale convention and pop culture tropes. Tiwi language is mingled with English, colloquial speech with rhyme, ballad singing with traditional Indigenous songs, Mozart and Beethoven. The production is staged around a set of portable proscenium arch frames decorated with crosshatched Tiwi designs. Set painter, Raelene Kerinauia, and painters of the brother puppets, Pedro Wonaeamirri, John Peter Pilakui and Linus Warlapinni, all artists from the Jilmara Arts and Crafts Association in Milikapiti on Melville Island, worked with Bryan Woltjen to realise the design.

The production was commissioned by the Darwin Festival and premiered at Adelaide’s COME OUT Festival in March 2011. It continues to tour Australia. The performance I saw was opened with a welcome to country by local elder Richard Davis and the audience ranged from the very young to the very old. This was a noisy, happy, slightly lunatic theatrical event, an enchanting and cheeky tale—testament to the potential for levity in storytelling and the importance of laughter and song in negotiating life.

Wulamanayuwi and the Seven Pamanui, a Darwin Festival commission, toured by Performing Lines, IPAC, Wollongong, 19-22 March; Cairns 19-20 June, Mackay 24 June, Brisbane 26-29 June

RealTime issue #121 June-July 2014 pg. 36

© Catherine McKinnon; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Julie Vulcan, Drift

photo Michael Myers

Julie Vulcan, Drift

The animal inside us, the wild and the civil, and the sea-shifting currents of journey were each explored by three new performance works in Brisbane: Circa’s Beyond, which premiered in Berlin before landing at the Brisbane Powerhouse; Sally Lewry’s powerful physical theatre work Cimmarón; and Julie Vulcan’s new live art work, Drift, the two latter works commissioned by Metro Arts.

I have to admit that I am a shameless fangirl of Julie Vulcan’s work. I say this as a caveat for those readers who are perhaps less engaged with the fragile experience of live art, or who are not as attracted as I am to the indubitably feminine aesthetic explored in Vulcan’s arresting body of work. Drift is a follow-up to I Stand In, an intimate piece where spectators witnessed Vulcan massaging volunteers, a private act in a warm, communal space (RT116). She brings that same quality of shamanic intensity to Drift, where the audience can watch or participate. You are invited to lie on a lime-green, inflatable lilo with a nest of shredded paper atop, which looks inviting but has a disconcerting texture and an unpredictable waterbed motion. Vulcan attends to each of the lilo-layers with precise dignity, providing a face-mask and an ear-bud for the sound-scape. She then massages your hand with a firm and sensual stroke until you relax. Your interaction ends with her photographing you, wrapping you in a metallic blanket and then folding the massaged hand around a delicate, palm-sized origami boat. Participants stay for as long as they want within the confines of the two hourly sessions.

The work’s gentle thematic is a commentary on passage and the precarious nature of boats as refuges, which has such a charged history for Australian immigration, not just in the latest brutal incarnation of White Australia in our refugee policies, but for the waves of immigrants who have come to our shores in vessels of all shapes and sizes. I could see many a traditional theatre patron at Metro struggle with an anxiety about time: when should I leave the lilo? This is partly the thematic of the work, but also a clue that some aspect of the timing isn’t quite fully formed. Perhaps this is a result of programming two short sessions daily that re-set, rather than a longer durational work that accretes over days. Paradoxically, in her artist’s talk Vulcan noted she had attracted a number of repeat, city-commuter walk-in spectators, who were coming back in their lunch hours. I think this is testament to how Vulcan as a performer and artist can hold a space, elevating and deepening it into a profound experience: sensorially, politically and, dare I say, spiritually.

In contrast to the delicacy of Vulcan’s live art practice was the earthy and engulfing experience of Sally Lewry’s new work Cimmarón. Lewry is a familiar face to Melbourne audiences but this was her debut in Brisbane. The intense, almost wordless piece played out on dirt, lit by the delicate shadow-play of lighting designer Paula Van Beek.

Sally Lewry, Tamara Natt, Cimmarón

photo Miklos Janek

Sally Lewry, Tamara Natt, Cimmarón

The trajectory of the work follows two bodies. The first is Lewry, dirt-strewn in a shapeless hessian sack: a grunting, pawing, howling wild beast but in no way aggressive or out of control, simply wild, tender and vulnerable, like a brumby or a new-born bird. She encounters Tamara Natt, a statuesque dominator, hair pulled back tightly into a plait at the top of her head, clad in dark, narrow clothes, with echoes of the military and dressage. The moment of first contact includes a full range of emotion: curiosity, distrust, potential seduction, but in what seems like an inevitability given the history of these binaries of centre and margin, dominant and abject, the wild is brutalised in what was for me the most powerful sequence in the whole show, bleeding in and out of Patti Smith’s “Wild Horses,” as Lewry’s figure was whipped and broken, made to dance in circles, to learn to obey and be remade in the image of her dominator.

The work reads beautifully across a range of political, feminist and historical contexts as well as conjuring a detailed immersive world. My only hesitation was around the journey of the dominator. This wasn’t about the quality of Natt’s performance, but a sense that the trajectory had been less interrogated and was less specific in movement vocabulary, in design choices, even in the objects allowed her in the space which were clichéd (whips/red carpets/sunglasses) compared to the genuinely surprising and satisfying nature of Lewry’s initial hessian attire, her naked torso revealed under pressure and her wild ram skull. When Lewry unburies this in the final third of the show it pulls the whole thematic of the piece together: the wild that is now dead, fossilised and curated and what was once pulsing and irresistible is lost but still encodes for us an involuntary and simultaneous attraction and repulsion.

Bridie Hooper, Circa, Beyond

photo Andy Phillipson Photography

Bridie Hooper, Circa, Beyond

Ironically, the piece with the most dialogue and literary pedigree was CIRCA’s new show Beyond. This Brisbane company is an absolute international juggernaut, perpetually on-tour and cycling through stages of formal experimentation—from digital technology to text-based collaboration. Beyond signals a back-to-basics circus form with a simple stage, traditional skills and a delightful, show-stopping premise: the animal inside us all. Drawing from a range of cultural references as varied as Alice in Wonderland, Donnie Darko and Cats the show is a smile-a-minute experience. You could take your most belligerently anti-theatre friend to see Beyond and they would thank you. That isn’t to say that the work is lightweight, quite the contrary, its magic lies in the way the death-defying skills of the tightly bonded ensemble skim across sophisticated cultural references to a charming soundtrack of Broadway standards and classic songs. The image of the supple bodies of the circus performers under their enlarged fluffy bunny heads says it all: the surreal and secret pleasures to be found in releasing our inner beasts.

Drift, concept, performance Julie Vulcan, sound design Ashley Scott, The Basement, Metro Arts, 1-5 April; Cimmarón, creator, director, performer Sally Lewry, co-devisor Xanthe Beesley, performer Tamara Natt, Sue Benner Theatre, Metro Arts, 4-22 March; CIRCA, Beyond, director Yaron Lifschitz, Brisbane Powerhouse, 30 April-11 May

RealTime issue #121 June-July 2014 pg. 37

© Kathryn Kelly; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

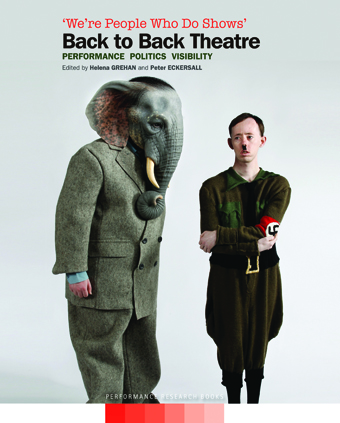

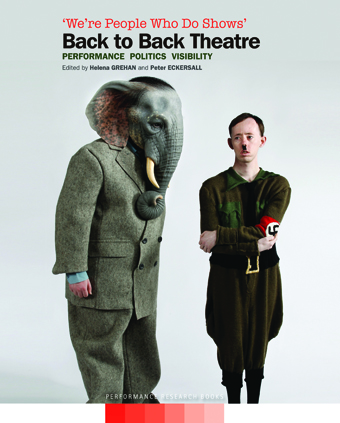

Here is a true rarity, an Australian book celebrating the long life and distinctive vision of a theatre company—Geelong’s internationally successful Back to Back Theatre ensemble. Rather than its works being playwright-driven, the company is an exemplar of contemporary performance, teaming an intensely collaborative director, designers and composers with performer-devisors with perceived intellectual disabilities to collaborate over very long periods on creations that unsettle our sense of time, space, identity and, not least, ability.

Here is a true rarity, an Australian book celebrating the long life and distinctive vision of a theatre company—Geelong’s internationally successful Back to Back Theatre ensemble. Rather than its works being playwright-driven, the company is an exemplar of contemporary performance, teaming an intensely collaborative director, designers and composers with performer-devisors with perceived intellectual disabilities to collaborate over very long periods on creations that unsettle our sense of time, space, identity and, not least, ability.

Published in the UK by the Centre for Performance Research in Wales, ‘We’re People Who Do Shows,’ Back to Back Theatre, has been ingeniously edited by Helena Grehan (writer, lecturer, School of Social Sciences and Humanities, Murdoch University) and Peter Eckersall (writer, dramaturg, Associate Professor, School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne). It’s a one-stop shop for scripts, interviews, artist statements, personal recollections, documentary history and complex academic analyses, an excellent collection of images, many by the great Melbourne photographer Jeff Busby, and admirably spacious design (Lin Tobias of La Bella Design, Melbourne) along with some fun touches like two brief flicker picture book series. I was surprised that ensemble performers are not always identified in photo credits, although the reader can sometimes make guesses based on discussions about roles in the essays.

The editors’ aim was to “create an archive” that is “multilayered and sensory or what Walter Benjamin calls ‘the mosaic’: ‘an immersion in the most minute details of the material content.’” They also saw the book as “dramaturgical,” “presenting a range of speaking positions juxtaposing image and text, creative and critical modes of response as well as….insights into the production process.” Further, the works would be “analysed through the lens of new media dramaturgy because it explores theatre’s compositional elements in relation to mediatisation and visuality.” These are frameworks within which Back to Back’s performances are so powerfully realised, conjuring associations with performance makers Romeo Castelluci, Robert Wilson, Hotel Pro Forma and light artist James Turrell, a key influence in recent works says Back to Back artistic director Bruce Gladwin in a long, wide-ranging interview with Performance Research director Richard Gough.

The editors certainly fulfil their ambitions in a book that views the company from numerous angles, inside and out. There is no literal account of the company’s history from 1987 save for a handy list of productions, each with an image and credits for the creative team, but in “In conversation,” previous directors meet with Gladwin and talk through Back to Back’s emergence and struggles for recognition. They recount how some support for the work came from a period of “normalisation,” which aimed to get people with disabilities out of institutions (“and save money”); a time when performers were allowed to move on stage but not speak; the discovery that one of the performers, Rita Halabarec, was a gifted writer (her piece Assembly is reproduced a few pages later); and the push to move from being “a sort of disability organisation” to getting support from the Theatre Board of the Australia Council as a company in its own right, which it became in 1997. The company developed as it engaged with Deakin University’s Woolly Jumpers Theatre-in-Education company, Handspan, Arena Theatre and Circus Oz, always developing skills, maintaining continuity and, as Gladwin puts it, “finding those mechanisms to get the best from people…the best framework to support them on stage and in the process of creating something.” The emphasis on democratic processes is emphatic: Gladwin talks about the importance of “hanging out,” sitting, chatting and “then we’d get up and try something.” Barry Kay recalls learning to focus on the “level playing field” of play. Ian Pidd remembers “always trying to push [performers] beyond their comfort zone,” a goal that Gladwin iterates elsewhere in the book.

The academic essays in the book engage passionately with the works that have emerged from Bruce Gladwin’s artistic directorship—these are the focus of the book. ‘Passionately’ because it is evident that they are moved by these works, disturbed by their capacity to deal directly with big issues and with a deeply unsettling ambiguity. Lalita McHenry, writing about SOFT (2002), approaches the work in terms of empathy, specifically Emmanuel Levinas’ notion of “Substitution—putting oneself in place of another.” At the end of SOFT we are left “face to face with the last man with Down Syndrome”—the rest of his kind have been eliminated in a massive eugenics campaign—but in the work’s first half a couple with Down Syndrome baulk at having a child despite the fact that the doctor they meet has the condition too. We are being tested, even more so, says McHenry, by the design, a vast bubble in which we sit each with headphones: “We see and hear from the inside out, as if we, the audience, are not yet formed, not yet human…[in] a womb-like sculpture.” It’s a striking observation that explains the sheer strangeness of experiencing SOFT.

Eddie Paterson’s “Script after script: Back to Back and dramaturgy of becoming” observes that “in recent works the process of writing for performance comes increasingly to the fore…highlighting the connection with performance art and the collapsing distinctions between author, director, maker, performer and spectator.” Citing scholar John Freeman, Paterson sees this as “a textual playground, where nothing is sacrosanct.” More than that, he writes, the works resonate with Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of ‘becoming,’ in which “minoritorian subjects strategically rupture dominant notions of language and power.” He focuses on the banality of the dialogue in small metal objects (2005), noting reviewer Alison Croggon’s initial feeling that the show needed a strong writer but later realising that “the script they have serves their purpose adequately.” Equally the notion of sole authorship is dispensed with by Back to Back, reflecting the collaborative creation of the work. Besides, the dialogue “becomes poetic” with the punctuating rhythms of the sound score. In Food Court (2009) the spare, brutal deployment of language (spoken, projected, “unstable”) makes radical demands on the audience. In a step further, if with transparent dialogue (and in various languages), Ganesh Versus the Third Reich (2011) becomes a “meta-theatrical commentary” on the work’s creation and issues of ability, casting, power (political, directorial), race and exploitation. Paterson’s account very aptly describes Back to Back in terms of its own dramaturgical becoming.

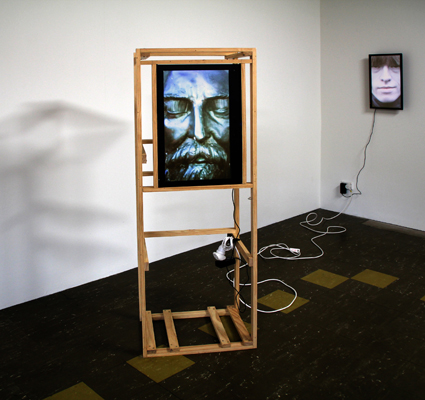

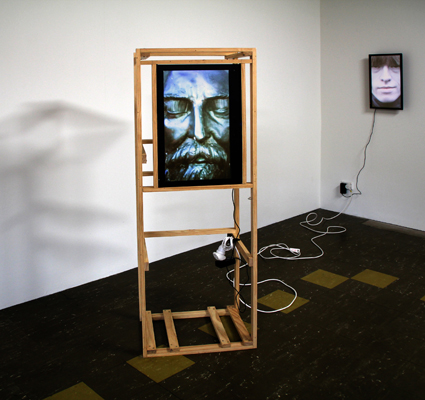

Food Court, Back to Back Theatre

photo Jeff Busby

Food Court, Back to Back Theatre

Helena Grehan in “Responding to the unspoken in Food Court” like McHenry leads from Levinas: “we have no option but to respond to the call of the other” without any expectation of reciprocity. She writes, “While [the performers’] bodies and voices act as markers reminding spectators that they are disabled, the content and searing or (awful) power of their exchange compels us to think and feel beyond a focus (solely) on questions of dis/ability.” She adds, “this is not the other after all, this is a group of performers performing the ‘majority.’” She finds this “shattering,” “it disallows any bystanding,” and there is no “panacea for spectators.” Agreed, but the performance is surely also, in the dialectical manner so true to Back to Back, about people with disabilities maltreating others with disabilities—there is no escaping that. In the same essay, Grehan quotes Gladwin as saying he feels ‘“an incredible responsibility to present [artists with disabilities] in a positive light’ but that for this work the decision was ‘to let it be as dark as it was.’”

Caroline Wake and Bryoni Trezise, in their essay, the one most acutely focused on form, “Disabling Spectacle: Curiosity, contempt and collapse in performance theatre,” also attend to Food Court, in which, as in all of Back to Back’s work, “perception is all.” Spectators are asked “to consider perceptions of disability through performances of disability,” the resulting tension “startl[ing] them into a moment of self-conscious insight.” The work achieves this, they argue, because it is “a hybrid form of ‘performance theatre’” [presumably contemporary performance + theatre, in a work calculatedly staged in a theatre ] “unsettl[ing] the historical alignment between spectacle and spectatorship…keep[ing] spectators in a zone of deferred perception such that a fixed vision of either self or performer can never fully arrive.”

To this end Back to Back’s work has “avoided the framework of disability theatre,” a form in which the nature and sociology of disability is delineated. Instead the company has realised, write Wake and Trezise, “disability performance in which performance is called upon to denaturalise the naturalisation of disability as performed spectacle” in which actors “perform only their [disabled] selves.” The writers add depth to Paterson’s approach to language, focusing on the unexpected, reversals and inversions, the creating and undoing of perceptions. They detect in the production’s impressionistic scenology “the same liminal Zone that Bill Henson’s images occupy, what has been called in the context of Romeo Castellucci’s work the human/dis-human.” Here they argue that the “visuality of spectacle” is “forestalled” by projected text “both explaining and obscuring the action,” along with extreme contrasts in lighting, at turns distancing and immersive. They point to the power of the final bare image of a human body after Food Court has “hurl[ed] every possible theatrical tradition onto the stage” as if “the medium of performance theatre [has seemed] to turn against itself.” In a relentlessly shifting dialectic “the audience perceives performance theatre as simultaneously staging the spectacle of disability and,” as the writers pointedly if drolly express it, “the disabling of spectacle.”

Ganesh Versus the Third Reich, Back to Back Theatre

photo Zan Wimnberley

Ganesh Versus the Third Reich, Back to Back Theatre

Adding breadth to the editors’ appreciation of Back to Back’s collaborative approach is “Lighting Design: Between theatre and architecture, An interview with Andrew Livingston and Paul Jackson.” Helena Grehan couples an interview with Bruce Gladwin and an essay about the participatory video work The Democratic Set (2009), applauding it “as some small space of resistance to the troubled and bleak mainstream” critiqued by Henry Giroux. She captures well the sense of inclusiveness, shared responsibility and the “space of wonder” that the Democratic Set represents and the question it poses to all who make or watch it, “What is art?” Barry Laing reports on the “arrests” he suffered teaching a Back to Back Summer School, having to “change gear, slow down and somehow accommodate this voice: a voice that emerged as witty and irreverent and rich in imagination. This changed the way I was working.” As well, in their introductory essay, the editors condemn the unjust pressure (and lack of support from some key arts organisations) applied to Back to Back by a US-based fundamentalist Hindu organisation over the representation of Ganesh in the Melbourne Festival premiere of Ganesh Versus the Third Reich. Such crude opposition stood in the way of appreciating the work’s much needed insights.

Grehan in “Irony, Parody and Satire in Ganesh Versus the Third Reich” addresses audience complicity in a postmodern work which “positions its audiences in such a space of undecidability that it is difficult to know what ‘good’ spectatorship (in ethical terms) may entail. Fear of laughing at the wrong moment, wondering if the performers are behaving as they actually did in rehearsal or is this work parody, concern about your motives for seeing “a bit of freak porn” (as one of the ensemble, Scott Price, puts it), “feel[ing] empathy, at times a sense of embarrassment,” or sensing that “Scott’s frustration” with the dictatorial director is “very real” (despite the fictional frame)—are cumulatively unsettling. “We don’t want to be bad spectators; instead we want some idea of what it is we should be doing. There is no resolution.” Grehan sees Ganesh Versus the Third Reich as placing us ethically in a position of profoundly questioning the act of spectatorship, just as Wake and Trezise do in respect of perception and the play with forms.

In “Scott’s Aired a Couple of Things: Back to Back rehearse Ganesh Versus the Third Reich, ” Yoni Prior documents her experience of observing the development and rehearsal of the production, focusing on “the ways in which the company positions members of the ensemble as entirely legitimate professional artists, whilst claiming the authority of outsider artists to challenge the perceptions and representations of disability.” She details “an improvisation in which a serendipitous misinterpretation opened up unmarked territory between ‘what is fiction and what is not.’’’ And she adds another layer to the list of ambiguities perceptual and moral addressed in previous essays, writing “[to] borrow Richard Schechner’s distinction, Scott [in what is to become the scene mentioned above] is acting and not-not-acting in this moment as he performs a version of himself.”

In her conclusion, “Playing the reality line,” Prior writes, “The fact that the actors bear the unmistakable marks of disability generates both anxiety and excitement. They appear vulnerable and we who watch them are not always sure if they are safe [onstage]. We are not sure if they are in control, if they know what they are doing…we may be watching authentic distress rather than ‘good acting.’” However, “Ganesh Versus the Third Reich plays masterfully with ambiguities of ethics, meaning, control, intention and authenticity by confronting the audience with multiple challenges to their own ability to identify ‘the reality line.’” This means our stare is turned on us, she says: “the work glares back, remorselessly demanding an apologia from its audience, asking, ‘What are you looking at.’” Or, as in Grehan’s essay on Food Court, the question is presumably “Who are you?”

Tessa Scheer’s “The Impossible Fairytale, or Resistance to the Real” directly addresses the bodies of the performers in Ganesh Versus the Third Reich specifically in terms of their challenge to “the hegemony of the well-trained, socially approved ‘body beautiful’’’ and in the context of a well-established ‘Hollywood’ desire for the disabled to become the “honorary disable-bodied,” more ‘normal’ than different. Disturbed by audience members who preferred the work’s non-meta-theatrical scenes with their visible disabilities, Scheer thought she detected a desire to “favour the fairytale.”

Ensemble members, former and current (Rita Halabarec, Sonia Teuben, Nicki Holland, Simon Laherty, Brian Tilley, Sarah Mainwaring, Scott Price and Mark Deans) figure strongly in the book—in photographs, in essays and interviews where the power of their performances and their willingness to meet challenges are acknowledged— and in their ensemble statements—“We’re people who do shows/ We’re all quite short/ a little bit taller than the one before/ We’re agile and we work/ professionally in a theatre company” and “We’re not afraid to step into the cold, dark side./ At first we’re scared, but/ afterwards we feel good. We are witty, We are emotional. We go deep into the work./ We go to places you can’t go/ in real life.” Of course, many of the words in the scripts are theirs too, borne of exchanges or improvisation, or found, as they were for Food Court.

In New York, at the Under the Radar Festival in 2013, Scott Price and other ensemble members wrote and presented From Where I Stand which included the lines: “I can see the end of ultra-conservatism/ We will stand up in defiance, even though standing is difficult/ for some of us…And I can also see a post-disability world where there is an/ important place for everyone to occupy…”

‘We’re People Who Do Shows,’ Back to Back Theatre is a book for many people, at once accessible and erudite, intimate and esoteric, illuminatingly edited, illustrated and designed—a tribute to a great and enduring company, whose presence onstage we welcome again and again, greeting their difference as part of our lives, admiring their performances as we would any professional ensemble of high calibre and acknowledging the genius of Bruce Gladwin who shares his creative life with his talented ensemble, “providing the best framework to support them on stage and in the process of creating…” I thank Back to Back for taking me, as they write, “to places you can’t go / in real life.”

‘We’re People Who Do Shows,’ Back to Back Theatre, Performance, Politics, Visibility, editors Helena Grehan, Peter Eckersall, Performance Research Books, UK, 2013

RealTime issue #121 June-July 2014 pg. 38-39

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Tim Walter, Andrea Demetriades, Glenn Hazeldine, Rebecca Massey, Perplex, Sydney Theatre Company

photo Lisa Tomasetti

Tim Walter, Andrea Demetriades, Glenn Hazeldine, Rebecca Massey, Perplex, Sydney Theatre Company

Step back from the comedy of German playwright Marius von Mayenburg’s Perplex and you see it for what it is: a nightmare of the age of identity theft. But it’s one where you don’t have to have your cards stolen or your phone or computer hacked. It just happens. And you have another identity foisted on you.

STC, Perplex

In Perplex you come home from a holiday to the friends who have been looking after your apartment, they treat you like intruders and force you out. There are subsequent displacements, increasingly bizarre: unwelcome new roles assumed, sins inherited, sudden adulteries and big ideas (in the shower a man comes up with the Theory of Evolution, only to be disabused of his too late discovery by his erstwhile wife). There’s a child who grows quickly into a Nazi; man-on-man sex (to the surprise of both parties) at a wild Viking dress-up party with a woman who has turned into a volcano.

And so it goes until the work’s larger mutation into a meta-theatrical and metaphysical confection when one character demands to know, “Who cast me?” The subsequent postmodern game playing (the director has abandoned the show and the set is pulled down around the actors) is a tad too familiar (“Are you doing a monologue? We said we wouldn’t do any more monologues”), although it has its moments, including the sudden appearance of a nutty (God is dead) Nietzsche at the window. He is inadvertently shoved and falls: “We have killed him!” one of the characters cries and the knowing audience laughs as the certainties—social, sexual, political, metaphysical and theatrical—of middle class life fall away.

Perplex is fun if not metaphysically particularly convincing or consistently funny. On opening night the performance was initially strained, over-emphatic instead of convincing us of the realism that would soon be ruptured. However, once underway performers Andrea Demetriades, Glenn Hazeldine, Rebecca Massey and Tim Walter excelled in their comic dexterity in Sarah Giles’ brisk, quick-witted production. Perplex doesn’t match the depth and reach of Marius von Mayenburg’s Fireface, Moving Target, The Ugly One and Eldorado, although the number of productions of Perplex across Europe suggest he’s hit a nerve with a work that evokes the instability of dreams and the terrors of erased and imposed identities. It’s good to have seen it here.

STC, Fight Night

ABC TV’s Q&A angers me. I can rarely sit through it. It’s raison d’etre, giving citizens the opportunity to have “your say” is a nonsense. Questions remain partly or not answered at all or are deflected to an inappropriate panellist by a mediator who cannot stop himself from repeating and interpreting the question and editorialising. Rarely is any argument sustained. Outrageously, in subsequent advertising Q&A exploited the recent onstage student protest it failed to respond to. Jones’ retort, before subsiding into bewildered silence on the night, was that old standby: “You’re not doing your cause any good.”

Fight Night (a collaboration between Adelaide’s The Border Project and Belgium’s Ontroerend Goed for the Adelaide Festival and STC) irritates me too, as soon as “your voice,” the audience’s, is invoked by another smug host (at least he’s being ironic, if tiresomely so). Shortly, he has us on the path to choosing a winner from a group of candidates in a protracted, shallow process that barely justifies itself by being thinly satirical and occasionally funny—or very funny for pockets of the audience. The ‘choices’ are all too quickly revealed not to be choices at all—the point being that we vote for mere appearances and with rapidly diminishing information with which to judge. What’s new?

It’s presumed our voting will tell us something about ourselves. We have in our hands iPod-like devices that record our votes, which will determine who leaves the contest, as in reality TV shows. When the show veers into the surreal or the obscene its potential is revealed, but even here choice is a joke—there are only obscenities to choose from. Cynical fun, but not revealing. Predictably the candidates manipulate each other and us, compromise, shift ground, change the rules and in a coup, depose our host, causing a revolt where we are asked to vote as one for a winner to be our leader or to leave the theatre. Some 20 of us do. The process is rigged. The show’s a fiction but we can’t conscionably stay. If the message is that we voted shallowly, well of course we did, the options were far too thin to provoke self-awareness, of any sense of our identity in a democracy.

The actors do a fine job, constantly adjusting to audience whims with a mix of scripted declarations and quick-witted improvisation, and the two vote-counters at computers keep the stats rolling. Certainly in their conservatism the audience on this night remained true to the sad state of our nation. As for the work’s title, the boxing ring set and capes worn by the five performers at the outset, the mike hanging from above and the bow-tied MC give limited life to the boxing match metaphor which was neither adequately sustained nor at all revelatory.

Parramatta Girls

A reunion of former inmates of the Parramatta Girls Home (1887-1973) provides a straightforward formula for recollection, denial, power play and revelation, simple and complex, in a new production at Riverside Theatre of Alana Valentine’s Parramatta Girls (2007). Despite passages of blunt exposition, awkward scene transitions and episodes of laboured dialogue the play delineates the lives of some intriguing individuals, victims of an antiquated and often physically and sexually abusive system of punishment—in some cases simply for being an Aboriginal child.

Long after their incarceration is over, the women are still haunted by its legacy—some ashamedly admit to hitting their own children, others recall nightmarish incidents—and by the ghost of the young Maree who died in custody. She is the link between the reunion and re-lived moments from the past. Other wounds are psychosomatic; Valentine uses the condition to suggest the potential for social and psychological healing. At the beginning of the play, Judi (Anni Byron) hides an elbow wound that hasn’t healed in decades—initially the result of endless floor scrubbing in the Girls Home. At the conclusion, after much denial in the face of accusations, she admits she had sexual relations with the institution’s director and thus enjoyed certain privileges. Now she finds her wound has healed; she can apologise to her fellow inmates and also acknowledge the existence of the ‘Dungeon’ and the institution’s other dark punishments she had refuted.

Other prisoners had first been wounded by their families, by class, race or psychological problems, their suffering cruelly exacerbated by incarceration and their sense of difference making for uncomfortable lives in prison—the middle class Lynette (Vanessa Dowling) sits to the side for much of the first of the two acts, sadly probing a life split-in-half. Valentine’s characters are sharply delineated if to varying degrees, each expressing pain, anger and joy vividly conveyed by Byron, Downing, Anni Finsterer, Sandy Gore, Sharni McDermott, Christine Anu, Tessa Rose and Holly Austin (as the ghost of Maree, who, pregnant to a guard was kicked in the stomach by him; she then suicided).

The horrors visited on these women (based in part on those Valentine met while researching for the play) were many: beatings, the removal from their mothers of babies born in prison and humiliations—Maree forced to wear a bedpan as punishment for bedwetting. More complex was the pain they inflicted on each other and the mutilations of their own bodies. Although the ending of Parramatta Girls is briefly upbeat, some of the women have pride in their subsequent achievements (including helping shut down the Home), some are still recovering, some forgiving, but the play makes it clear that to develop and sustain a sense of identity in such circumstances of constraint, humiliation and enduring self-doubt is a near impossible task: “We didn’t get out with our dignity intact,” says one. (For more on the Parramatta Female Factory Precinct Memory Project see http://www.pffpmemoryproject.org/)

EMD (exposed to moral danger)

Projected onto the stage floor of Parramatta Girls, below designer Tobiyah Stone Feller’s evocation of the semi-ruined Girls Home, are the letters ILWA, standing for “I Love, Worship and Adore.” These affirmations addressed by the inmates to each other can be found carved into the walls and doors in the actual building, 20 minutes walk from the Riverside Theatres.

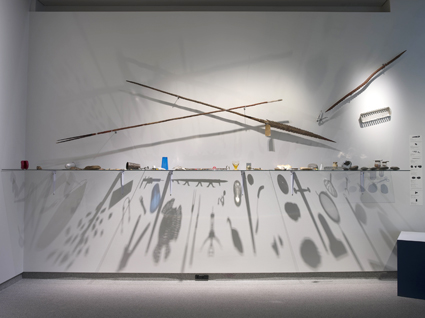

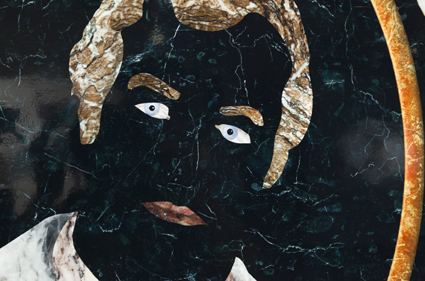

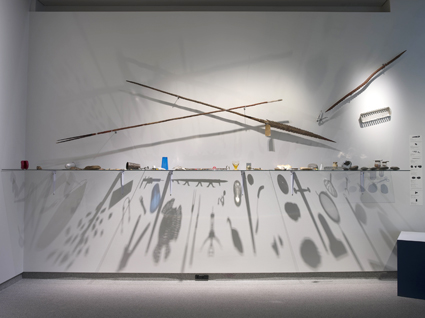

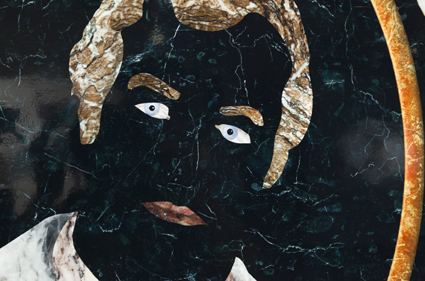

The site exhibition EMD (exposed to moral danger) evokes the lives of the inmates by means documentary and impressionist with video interview (Lily Hibberd speaking with former inmate and writer Christina Green), sound, painting, installation and sculpture throughout the building. Among works by Bonney Djuric the projected eyes of an abusive director of the institution greet you at the top of the stairs; opposite is a decaying room in which long paper dresses sway like ghosts; and further along two perspex screens conjure now disappeared ‘segregation rooms’—or solitary confinement cells. In a small room downstairs, in three Broken Spirit linocuts by Jeannie Gypsie Hayes, small ghosts dance behind bars and nearby Elizabeth Day’s I Love Worship and Adore fills a large room with the letters ILWA. She has worked outside casting ILWA writ large in plaster on hessian and brought the sculpture inside complete with earth and freshly growing grass. The work dramatically turns a small, ambiguous act of defiance into a memorial of growth and hope. Along with archival photographs, these works evoke something of the lives and identities lost to cruel institutionalisation.

Valerie Berry, Phillip Mills, ClubSingularity, Theatre Kantanka

photo Heidrun Löhr

Valerie Berry, Phillip Mills, ClubSingularity, Theatre Kantanka

Theatre Kantanka, ClubSingularity

Members of a social club dedicated to matters cosmological gather for a final meeting in which they keep their distance from each other, bicker over scientific ideas to do with the Big Bang and Singularity theories and execute an agenda of performance routines for their mutual entertainment—or, more likely, egotistic self-expression. Each has a guise—one is a ‘star,’ a Marilyn Monroe imitator (Valerie Berry) who precisely reproduces the scene from The Seven Year Itch (1955) in which the character’s dress is forced up by ventilation from the New York underground rail system. Another would-be star is the club’s dictatorial Chairman (Arky Michael) who is prone to breaking into impassioned song with a bad Italian accent. Another star of a kind is a pretend Astronaut (Phillip Mills), aglow in his bubble helmet, while the fourth member has cast herself as a sexy brunette Alien (Kym Vercoe) and, as such aptly unpredictable, begrudgingly performs dramatically with that staple of sci-fi movie music, a theremin. The final member presents herself as catwalk star—a fashion Model (Katia Molino) with very firm scientific ideas, an array of sparkling outfits and a bouquet of songs. A barman-cum-musician (Paul Prestipino) serves drinks and a soundtrack of quakes, cosmological soundscapes and live electric guitar and other accompaniments.

The design, like the members’ performances, is calculatedly ‘amateur,’ capturing the DIY naivety of the club—paper lanterns hang like planets about a high wall of golden glowing fairy lights—but hints at something more profound.

The Chairman speaks of his fascination with the heavens as a child, “I grabbed a star—it tasted so sweet.” Moments of whimsy and spacey dreaminess alternate with jokiness and home grown spectacle. As the astronaut gently swings a lamp, like a planet, around the head of an increasingly panicky Monroe (“160 heart beats per minute”), the Model’s gentle lyrics about loneliness reflect on “thinking of your private parts.” These are lonely people, the Chair longs for “another world to find love in,” the Astronaut seeks someone to “boost my rocket.” These desires escalate into a near orgasmic eruption of explosions and all-encompassing vibrations. Little micro-dramas play out as well. The Alien pops on an ET-type mask and dances erotically before the Astronaut but attraction-repulsion forces play out—drawing him repeatedly to and from Monroe; the Alien tears off her mask and weeps. Her ‘routine’ has not succeeded. The Model explains that Dark Matter is holding the cosmos together but that “repulsion is everywhere.”

The meeting progresses: a competition offers the winner an Armageddon survival suit or a bottle of tequila, the Model sings that “the Earth is round but the universe is flat” and hosts a quiz. The Alien gets all the answers wrong but defiantly defends String Theory and the right to speculate. She withdraws, weaving cats’ cradles before erupting into an immolating rant wreathed in smoke.

A huge quake preludes the meeting’s “last dance”—not that they take to the floor. Instead they lean into their little bar tables, hands circling the tops, then reaching up and out and vibrating into a near lift-off into space. In the following calm, comforting words are spoken about our lives as “sharing a common ancestor [carbon],” as “just a spark or an incident,” or “a prelude to a new adventure.” Slowly, the club members exit through the wall of light: “We have loved the stars too much to be afraid of them.”

We now know why this meeting has been announced as the club’s last. But this death wish provokes as many questions as it answers. Is their final act, like their other performances, just a routine, or simply metaphorical—they would if they could defeat their loneliness by merging with the stars. Not recommended for serious sci-fi fans but for those who enjoy contemplating the big questions at a safely whimsical distance it’s fun. If these humans can’t identify with each other they at least can with the stars. ClubSingularity is diverting, if not hilarious, structurally somewhat flat, if lifted by moments of enjoyably tacky spectacle and cartoony characterisations performed with verve by the cast. ClubSingularity is a reminder of how in everyday life—and not just in poetry and drama—we employ metaphor and analogy to help explain our lives, reducing big ideas to fit simple emotional needs, accruing a sense of identity—of oneness with oneself, possibly others and, yes please, the cosmos,

Sydney Theatre Company, Perplex, writer Marius von Mayenburg, director Sarah Giles, Wharf 1, STC, 20 March-13 April; STC, The Border Project and Ontroerend Goed, Fight Night, Wharf 2, 22 March-13 April; Riverside Productions, Parramatta Girls, writer Alana Valentine, director Tanya Goldberg, Parramatta Riverside, 3-17 May; Parramatta Female Factory Precinct Memory Project, EMD, curators Alana Valentine, Lily Hibberd, Michael K Chin, 12-18 May; Theatre Kantanka, ClubSingularity, director Carlos Gomes, lighting Mirabelle Wouters, presenters Performance Space, National Art School; Cell Block Theatre, Sydney, 21-24 May

RealTime issue #121 June-July 2014 pg. 40-41

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Kate Hunter, Memorandum

photo Leo Dale

Kate Hunter, Memorandum

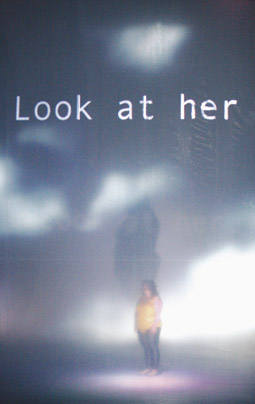

Some themes are so universal that they approach redundancy. When the author of a work states that its intended subject is identity or the body or place or consciousness there’s a very real risk of tautology, because there are so few works that don’t address every one of those broad notions in some sense. Navigating your way to the bathroom in the middle of the night does too. Doing something interesting with such grand notions is obviously a grand challenge itself, but sometimes the most effective method of painting big pictures is with a very fine brush.

Kate Hunter, Memorandum

Kate Hunter’s Memorandum concerns itself with one of the hoariest of topics, at least since mid-90s academia wrung every last drop from its cadaver. ‘Memory’ is the face that launched a thousand theses, perhaps second only to ‘desire’ in the empty signifier stakes, and there have been oceans of ink sacrificed by students justifying how (insert favourite text) is an exploration of memory’s vicissitudes. Proust did that, but someone has probably made a decent argument that Seinfeld did as well.

Hunter’s own performance history is one rich with promise. She’s a regular with physical theatre ensemble Born in a Taxi, has trained with Anne Bogart and Tadashi Suzuki’s SITI and her solo outings over various Melbourne Fringes have been engaging and well-received. She has a keen sense of the theatre as an embodied space and there’s a liveness to each of her performances that is likely a result of her work in improvised contexts.

But there’s a distinction between a work about memory and a work about a bunch of stuff that the artist remembers. Where once there was frequent lament over cultural amnesia, it now seems as if most lives are worthy of a memoir and any gaps in historical consciousness can simply be spackled over with the grey paste of a few childhood recollections.

Hunter’s narrative doesn’t rise above the memoir mode, but does trouble it in a way that ultimately bears fruit. Amid billowing clouds of smoke or overlaid with projected mirror images of her own form, or bouncing between layers of live and pre-recorded audio, she begins to lay out a narrative that commences in her own childhood but quickly dissolves into false memory, blatant fiction, recollection rendered in the second person, dream, speculation and commentary.

She names names, too: those of the youthful classmate who flashed his penis or the kid whose obvious poverty was made a laughing point, or the one who was chased down the street by a father brandishing a woodsplitter and threatening murder. Her adult self abruptly rounds a corner to face a man administering euthanasia with an axe head to a cow that has tumbled from a cliff. She has that awkward nocturnal encounter you have with a parent you’ve already buried in the ground and who is now asking for an explanation as to what the hell that was all about.

Perhaps the reason artists so often return to memory as a subject is that it is a thing of such stupid artifice. How dare we think that time can be arrested! The ego of it, the unfettered individualism, to think that those things we’ve lived through can be removed from the passage of natural decay and preserved by some private magic. From the inside, the memory of one person is close to all that there is of this world. Viewed from space, or even from the vantage point of a theatre seat in comfortable darkness—same thing, really— the same memory is as inconsequential as a breath.

But there’s not much life without breath. Hunter’s performance might not reveal a great deal about ‘memory’ and there’s an irony in the way that works about memory are themselves rarely memorable. But her words have that trained liveness, complemented by Richard Vabre’s sterling and deeply responsive lighting design, to allow each recollection a moment’s return. Hunter’s memories aren’t our own, and often may not even be hers, but rather than validating ‘memory’ there’s the possibility here that she’s paying respect to the dull and tiny inevitable death of everyone. Hunter doesn’t attempt to glorify her own recalled moments but treats them as subjects of curiosity, humour and sport.

Death at Intervals

photo Anna Malin

Death at Intervals

Colleen Burke, Death at Intervals

Death: that’s another one of those big and tiny subjects. Colleen Burke’s Death at Intervals balances its major and minor chords in unexpected ways. Liberally adapted from Jose Saramago’s As Intermitências da Morte, this puppetry work’s narrative delivers an unnamed nation in which death has inexplicably ceased—murders, accidents and even plane crashes leave their mutilated results still counted among the living, though not without resultant agony.

A lot depends on death, it turns out. Puncture the cycle and religion, politics, the economy and much more will suffer. Death at Intervals is less about the metaphysical implications of its premise and more about the socio-economic. At first we have only the moaning of funeral directors to put up with, but in time the wheezing almost-dead build up enough presence to force any audience member to wonder what would happen should cessation really cease. The zombie narrative is omnipresent today, but cauterise it of its violence and things actually get far more unsettling.

Burke’s adaptation bears obvious resonance with today’s Australia; the rising tide of the not-dead is used by a Prime Minister to justify a cruel and demanding new budget, while the fact that the bizarre situation is restricted to one nation establishes a xenophobic obsession with borders that is all too familiar.