September 2014

Making art is more than a job and it’s more than a life-style choice—for many, it’s an all-encompassing way of being. This can make living with an artist a difficult feat, unless both are of like constitution. So it’s not surprising that in the art world there are many couples who share both their lives and their art.

RealTime is run by such a couple, Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter, who, before their foray into publishing, also produced a large number of contemporary performances as Open City, often drawing on personal experiences and their relationship or, as Apartners, working as consultants for other artists.

Of course it’s not all smooth sailing—one’s partner is often one’s harshest critic, but perhaps this is a key to the conceptual rigor often illustrated in the creative manifestations of couples. To get to the bottom of this, over the next two Profilers, we are asking a number of art couples about their collaborative practices. We thank them for their generosity and their honesty.

Gail Priest, Online Producer

PS. The natural extension of this is the art family, and if you haven’t already, the RealTime team strongly suggests you read The Family Fang by American novelist Kevin Wilson about two siblings struggling to accommodate their performance artist parents’ radical interventions. Nicole Kidman’s production company has produced the film of the book, directed by Jason Bateman.

Alexandra Clapham & Penelope Benton | Clocked Out (Erik Griswold & Vanessa Tomlinson) | Claire Healy & Sean Cordeiro | Andrew Morrish & Rosalind Crisp | Sally Rees & Matt Warren |The Ronalds (Shannon & Patrick) | Starrs & Cmielewski (Josephine & Leon)

Penelope Benton, Alexandra Clapham

courtesy the artists

Penelope Benton, Alexandra Clapham

Alexandra Clapham & Penelope Benton

We are currently working on an ongoing series of performance installations investigating our relationship as both partners and collaborative artists. This has come about really as a response to interest that emerged from interviews and discussions about our roles as Co-Artistic Directors of Art Month Sydney 2013, and the works we produced after that time. We were pushed throughout that period to talk about the benefits and challenges of working together as romantic partners, and so it’s been a natural progression that those conversations and reflections have become the focus of our current work.

The experience of producing our first collaborative work in late 2010/early 2011 made us aware of the different skill sets we each have and how they can and do complement each other so well. We also found the scale of work we could produce together was much greater than either of us had attempted or contemplated in our individual practices at that stage.

Beyond that initial realisation, of course we also discovered the tension and difficulties of working as collaborative artists with different schedules, priorities and approaches to making. We find ways to negotiate that, sometimes we can work through it and produce something incredible, other times, for whatever reason, we can’t or don’t want to, and there’s a silence. This process has inspired our recent series of works.

Alexandra Clapham, Penelope Benton: 1) Great Expectations, Day for Night, Performance Space; 2) Self-Portrait in a Room, SafARI 2014

courtesy the artists

Alexandra Clapham, Penelope Benton: 1) Great Expectations, Day for Night, Performance Space; 2) Self-Portrait in a Room, SafARI 2014

Great Expectations for Performance Space’s Day for Night at Carriageworks earlier this year was presented as a tableau vivant in sittings varying 90-150 minutes. This piece encapsulated both our working relationship and romantic partnership, a rhythm one could say was synonymous with many couples. The days, the nights, the stillness, the nothing, the expectations, the boredom, the waiting, the brewing, the growth of ideas, the clashes, the tension, the conflict, the noise, the intensity, the passion, the moments, the magic.

At Wellington St Projects for SafARI this year, we built two sets within one room in an adaptation of Floor 7½ in Charlie Kaufman’s film Being John Malkovich—the half floor which has a portal to Malkovich’s mind. Each set contained a hyperreal version of ourselves presented as living self-portraits, this time in sittings of 180-240 minutes. Again the tableau is used as an allegory to examine our public and private selves, both as individuals and as partners.

Our new work currently being developed, experiments with these living portraits in video format.

http://penelopealexandra.com/

Related article

Enduringly queer

Fiona McGregor: Day for Night, Performance Space

RealTime issue #120 April-May 2014 p26

Clocked Out Duo in the studio

courtesy the artists

Clocked Out Duo in the studio

Clocked Out (Erik Griswold & Vanessa Tomlinson)

When “partner art” is good, it’s really good. But when it’s bad, it’s really bad! To be able to take a new idea, the excitement and creative energy, and share it with someone you love is a beautiful thing. That enthusiasm can spill into your everyday life and become infectious. Meetings happen at any time, inspiration arises while hiking, watching TV, gardening or waiting for the kids’ cricket game to finish. And on the good days, when this does happen, you have your collaborator right next to you and the idea progresses to actuality in an instant. The energy of two people can lift something out of the imagination effortlessly. But if you pick the moment badly, the same idea can also get squashed and left behind. If there is any negativity, conflict or stress, there is no escape. It doesn’t stay in the office, but follows you home 24/7.

Two advantages of working with a creative partner over a long span of time (about 20 years now!): the depth of possibilities that come from experience; and trust. We know that at the end of the day, our partner will come through. On the other, hand there is the challenge of how to keep things fresh. For us it’s been essential to have a balance of solo, duo and collaborative projects which have consistently helped to reinvigorate our artistic practice.

Clocked Out Duo with The Australian Voices.

courtesy the artists

Clocked Out Duo with The Australian Voices.

Our project The Wide Alley, based in Sichuan Province in China, evolved with us both experiencing a new culture together. It integrates the very survival of the situation, the amazement of newness, the adventure of discovery and the extraordinary music to be found there. We began this in 1999, at the beginning of Clocked Out, and in a way this adventure into another world shows us working at our best. We really need each other here, to communicate, push and understand just how difficult an artistic process really can be. We are heading back there soon to make Water Pushes Sand for the Australian Art Orchestra, to see now familiar things and to experience the new—with kids in tow. We are building new experiences, supporting each other and trying to make sure that support includes critiquing, asking questions. Hopefully by now we know how and when to push each other, when to step up and cover the other’s insecurities, when to allow the other to shine. We wouldn’t have it any other way.

http://www.clockedout.org

For more on Clocked Out see our Archive Highlight featuring all articles about the duo since 2001

Claire Healy & Sean Cordeiro, Dounreay, 2014, Gallery Wendi Norris

photo Johnna Arnold

Claire Healy & Sean Cordeiro, Dounreay, 2014, Gallery Wendi Norris

Claire Healy & Sean Cordeiro

Right now we are working towards our solo exhibition at Gallery Wendi Norris in San Francisco. The exhibition is titled Architects of Destruction. The body of work consists of Lego, cross-stitching and whiteboards. The works all depict fantastic scenarios that inevitably lead to destruction. They are based on historic catastrophic events or allude to future scenarios that may lead down a similar path. The works meditate upon the saying ‘the road to hell is paved with good intentions.’

There are many levels to the execution of a body of work like this. Initially one of us would have been struck with the idea. This would then have been conveyed to the other, and probably not met with the same enthusiasm, so the idea was probably shelved in a sense by writing or drawing it into our shared diary. Although an initial concept may not be considered so great, we record the idea anyway. Over time, ideas percolate or other opportunities arise, an old idea is revisited and given a different spin. We have found that our minds work very differently, so using this method seems most effective. We often forget who came up with the initial concept, or an idea has morphed so much from incarnation to execution that it really becomes a true collaboration.

We have found that working collaboratively can mean having to verbalise everything we consider. Sometimes this can stifle the subconscious or naive level of art making. We did try reading an identical library once so that we did not have to speak to each other and eventually have our minds synched. This did not work! Our reading habits and speed, did not match. Perhaps subconsciousness is lost when a work is conveyed from two entities.

Claire Healy & Sean Cordeiro, Downstairs Dining Room – Octopus, 2014, part of Habitat, Rimbun Dahan, Kuala Lumpur

courtesy the artists

Claire Healy & Sean Cordeiro, Downstairs Dining Room – Octopus, 2014, part of Habitat, Rimbun Dahan, Kuala Lumpur

Executing work and seeing it to its end seems to be more effective when collaborating. When so much time, labour and effort goes into the creation of a work, it will not suddenly be dropped because you have lost interest. There is a level of mutual respect that somehow is great for completion. We both have different skills that complement each other. We don’t have scheduled meetings but find that being stuck in a car together for a long time forces us to talk about work.

Architects of Destruction, Wendy Norris Gallery, San Fransciso, 4 Sept-1 Nov http://www.gallerywendinorris.com; http://www.claireandsean.com

Selected articles

The artist as citizen

Ella Mudie: The Right To The City

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 p47

Shifting and shucking

Performance Space’s first Carriageworks Program

RealTime issue #77 Feb-March 2007 p13

Artists invade history

Daniel Palmer inspects the renovations at Elizabeth Bay House

RealTime issue #75 Oct-Nov 2006 p52

SCAN 2003: Sean Cordeiro & Claire Healy

Keith Gallasch

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 p8

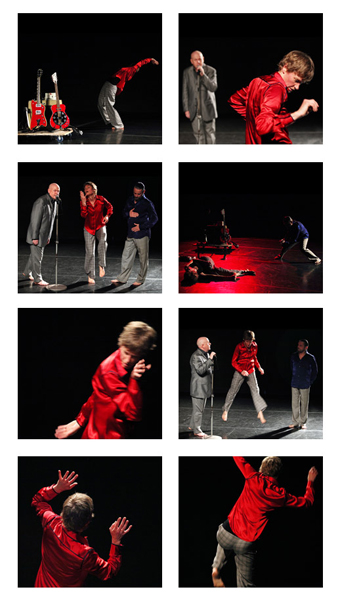

Rosalind Crisp, Andrew Morrish, Hansueli Tischhauser, No one will tell us…

photos Patrick Berger, courtesy the artists

Rosalind Crisp, Andrew Morrish, Hansueli Tischhauser, No one will tell us…

Andrew Morrish & Rosalind Crisp

I am a Partner Art Phobic. I am terrified of seeing ‘too much information’ disguised as intimacy. Ready to gag on presentation of the ‘reality of our relationship.’ I had been traumatised at an early age by one of a couple reading, in a performance, a description of her pleasure in cupping the balls of her partner, when I had had dinner with them the night before.

When Rosalind Crisp (dancer and choreographer) and I (Andrew Morrish, improviser and teacher) began our personal relationship in 1999, we were both established artists with our own practices. The romance of the moment did not sway us into thinking we would make work together. From my perspective this decision was driven by my prejudices and my feminist beliefs. From Rosalind’s perspective it came from the fact she was already too busy to include me.

Our first appearance together on stage was for two minutes in a piece by Emma Saunders at Omeo Dance Studio in which she invited 30 people to dance to the same two minute song in 2001. Nikki Heywood said we “had legs,” but I was not convinced.

Our separate practices meant we were both busy with our own work, but we were also partners so it was clear that we began to influence and support each other. I was able to help with keeping the Omeo Dance mailing list up to date, even made a letterhead for Rosalind’s company. Rosalind’s Sydney and international network became available to me as I began to expand my teaching practice away from Melbourne.

In a relationship, for me, the fundamental verb is ‘support’ and we both began to offer this to each other while we continued to develop as individual artists. We saw each other’s work a lot and of course became experts in it, and confidantes. These are very precious commodities. I always felt that it was important for Rosalind to be able to come home after a day in the studio and be able to complain to me about her collaborators and that this would not be possible, or be more difficult, if I was one of them.

When we shifted our base of practice to Europe in 2003, our support roles for each other became even more important in our new isolation. I was often involved in the production side of Rosalind’s presentations. I was not particularly skilled in that area, but I was cheap, available and understood her intention. It was also clear that at certain times, in certain French theatres, other production staff were confused by my role as Artistic Conseil/Husband.

On one occasion, when producing danse (4) in Paris, one of the dancers hurt her knee and was unable to perform. The structure of the piece could be rearranged to accommodate this, but the “4” in danse (4) refers to the number of dancers, so I became the fourth dancer. My role before that had been to organise the seating for the audience and to iron the costumes for the dancers.

I had already been a performer in duck talk (2005—a collaboration between Rosalind, David Corbet and The Fondue Set) and was later to become a performer in No one will tell us…(2010) In all this, and still today, it is clear to me that in these pieces I was working in Rosalind’s work. I maintain my own solo practice and this I consider to be my work. We have no work that is ‘our’ work. I support her work in anyway I can, through encouragement, criticism, technical and artistic participation, filling gaps when required. And she in turn does the same for me.

http://www.omeodance.com/VideoEn_NoOne.html

Selected articles

Dance like never before

Keith Gallasch: Rosalind Crisp, No One Will Tell Us…; Dance Massive

RealTime issue #102 April-May 2011 p12

realtime video interview: rosalind crisp

No one will tell us…

Dance Massive 2011 Online Feature

Oh how they danced!

Virginia Baxter: Oh I Wanna Dance With Somebody

RealTime issue #112 Dec-Jan 2012 p2-3

Testing the tightrope

Keith Gallasch on Andrew Morrish and improvisation

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 web

Rosalind Crisp is one of the 12 Australia choreographers featured in Bodies of Thought, published by RealTime and Wakefield Press (2014). Supporting material is available at realtimedance

Sally Rees, Matt Warren, Burnie residency

courtesy the artists

Sally Rees, Matt Warren, Burnie residency

Sally Rees & Matt Warren

Having a partner who is a practicing artist and collaborator can be an exercise in dealing with objectivity and subjectivity simultaneously. Critiquing the other’s work from the mindset of a partner begs care as to how your response may be interpreted, bearing in mind the intimate knowledge of the creator’s thoughts and biases as well as one’s own. However, one must also be mindful to remain an objective, critical onlooker.

Perhaps most importantly for the collaborative process, in addition, to the genuine enjoyment in working together, we have a deep respect for each other’s practice. It is the differences in approach, process and conceptualisation, not the similarities, that are the most important elements, colliding to produce something that neither one of us could achieve alone.

It is vital to both of us to keep objectivity at the forefront and maintain a professional attitude when we collaborate, perhaps as a result of having seen collaborations between other couples break down as the needs of the relationship become greater than the project. Often at the end of a collaborative day we may give each other a peck on the cheek and jokingly declare the act “purely professional.”

Having a child has made collaboration difficult as we’re rarely available at the same time—one is always parenting—but a recent opportunity changed that. A residency in Burnie (our birthplace and a once notoriously polluted city), where family generously took over child-care, meant that we were able to work side-by-side—our first one-to-one collaboration for some time. Suddenly two artists turn and face each other, reintroduced, after following each other’s practices in parallel. What a wonderful thing to do.

We acquainted one another with sites of personal history, allowing ourselves to indulge in memory to discover both shared experience and singularities and then seeing it all reflected in the eyes of our son. It was an inspirational and emotional experience.

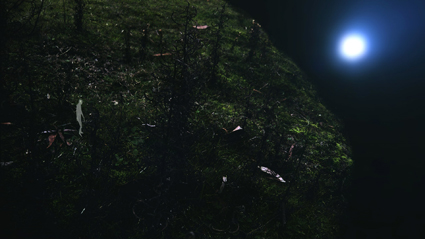

Sally Rees, Matt Warren, The Snowman

courtesy the artists

Sally Rees, Matt Warren, The Snowman

The creation of The Snowman evolved from shared memories of the local titanium processing plant that evoked mythic images of white men emerging and a stand of white trees by the roadside. An interview with an ex-employee gave further fodder to this idea and we used his voice to soundtrack an animation of a white figure moving through a landscape we created from weeds at the factory site. An invented, memorial cryptozoology.

Burnie residency blog: http://roomfiftyeight.wordpress.com/; http://www.mattwarren.com.au; http://sallyhasblog.wordpress.com

Selected articles

In Profile: Matt Warren, mumble(speak), III – real and imagined scenarios

Gail Priest

RT Profiler #6, 17 Sept, 2014

Attentively, on the edge of hearing

Andrew Harper, In A Silent Way, CAST Gallery

RealTime issue #112 Dec-Jan 2012 p43

SCAN 2003: Matt Warren & Sally Rees

Sue Moss

RealTime issue #57 Oct-Nov 2003 p31

Laboratory discoveries

Sue Moss

RealTime issue #53 Feb-March 2003 p46

The Ronalds: 1) Shannon Ronald with an example of one of a 3D Photo-Sculpture; 2) Patrick on location at the Barmedman Mineral Pool for the In Common project

courtesy the artists

The Ronalds: 1) Shannon Ronald with an example of one of a 3D Photo-Sculpture; 2) Patrick on location at the Barmedman Mineral Pool for the In Common project

The Ronalds (Shannon & Patrick)

Patrick and I have been collaborating exclusively on projects for very close to 10 years now. We started out working as Ronald+McDonell and since getting married in 2010 we have officially become The Ronalds, even though this is not quite as amusing as our old title.

We both trained as photographers, but over the years have morphed into installation artists who work in many forms, including photo-sculpture and interactive gamification. This progression into three dimensions and the virtual world is due solely to working as a partnership, pushing and testing both our diverse skills sets and interests.

Together we challenge each other to come up with more ambitious projects and to take on commissions that we might not be brave enough to attempt as solo artists. Our work is made stronger by our differing skills and opinions, as we both need to be convinced that our decisions are the best ones for our project, and it is during our constant discussions and problem solving that our best ideas are formed.

I have always explained our working relationship as me being the editor—Patrick comes up with the most fantastically ambitious projects, and I find ways to produce the same outcome in a more achievable way without compromising the original vision.

For our current project, In Common—Public Places of the Murrumbidgee/ Riverina, we have been commissioned to create work for the Wagga Wagga Art Gallery’s 40th anniversary next year. For this work we are creating hundreds of 3D photo-sculptures, small replicas of buildings throughout the region and turning the gallery into an immersive interactive environment that aims to reconstruct a region ranging 60,000 square kilometres from the Snowy Mountains to the vast plains of the Long Paddock. Our work roles in this project are defined naturally: we never need to decide who will do what, we just know. For this project Patrick has taken photographs of objects throughout the Riverina and will construct physical large-scale components and assemble any electronic parts for the final exhibition. I have created the online platform for the community input and will reconstruct Patrick’s photographs into 3D paper models and design the interactivity.

Over the years we have honed our individual skills and strengths to make working together on our projects a seamless process, and I can safely say that working as part of The Ronalds is the only reason that I am still making art. (Shannon Ronald)

www.incommon.com.au, www.theronalds.com.au

Selected articles

Regional Profiles: The Ronalds

Gail Priest

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 p27

Place: confirmed and displaced

Ella Mudie: You Are Here, Performance Space

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 p44

Starrs & Cmielewski

courtesy the artists

Starrs & Cmielewski

Starrs & Cmielewski

Our current project, Augmented Terrain, is an immersive audiovisual installation that re-imagines the relationship between nature and culture. We present highly detailed aerial views of Australian landscapes and waterways that we dynamically manipulate in ways that reveal their underlying fragility. Through collaboration with Slovenian artist Marco Peljhan, co-founder of C-Astral, we are using their fixed wing drone system to photograph these zones in crisis. Our vision is to configure the land as active and to imagine it being able to speak and make comment about human impacts upon it. This Creative Australia funded research project culminated in a two-week residency at the Io Myers Studio, University of NSW in partnership with Performance Space where we exhibited the first iteration of the work, documented here. The full-scale installation will be shown in 2015/16

Starrs & Cmielski 1 & 2) AugmentedTerrain 3) Drone launch, Augmented Terrain in development

courtesy the artists

Starrs & Cmielski 1 & 2) AugmentedTerrain 3) Drone launch, Augmented Terrain in development

A comment from Lionel Bawden, artist and friend.

“It is funny observing an artist couple, with the intimacy of friendship, as it is easy to take aspects of the collaborative relationship’s success for granted. I would say with Starrs and Cmielewski, it’s the things that make the relationship a success that similarly bond the collaboration. Their differences create strengths and they have a deep admiration for and acceptance of one another’s thinking. They can argue with the best of them, with very passionate, distinct voices, so conflict resolution really means they discuss decisions in detail. Leon and Josephine are very playful in their thinking, so they take risks together, taking the audience in interesting directions.

It is like going to their place for dinner—they usually prepare different parts of the meal separately whilst conjuring the banquet together, often using recipes they have been perfecting for a long time, which one may have originally introduced to the other. They confer and consult constantly and one will defend their decision to cook something another five minutes or throw in a little more of something, to a supportive “Okay, good, I was just checking.” There is always a new piece of technology brought in to spice up the dish, like a space age barbeque on the balcony. Their dinners are amazing and over time their collaboration has become simultaneously more inventive and more relaxed.”

Selected articles

Critical flows: climates & peoples

Janine Randerson: Starrs And Cmielewski, Incompatible Elements

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 p39

Making it internationally in media arts

Julianne Pierce: Australian media artists overseas

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 p32

Part 2 of Partner Art will appear in RT Profiler #7, 12 November 2014

RealTime issue #122 Aug-Sept 2014 pg. web

Cat Jones, Anatomy’s Confection

courtesy the artist

Cat Jones, Anatomy’s Confection

Multidisciplinary artist Cat Jones is in Adelaide this month as an ANAT Synapse artist-in-residence at the University of South Australia’s Sansom Institute for Health Research. She is attached to the Body in Mind research group who investigate the role of the brain and mind in chronic pain. Here she will be continuing one of her current investigations which looks at the idea of body illusions and their application in treating chronic pain.

Vocationally and geographically, Jones is hard to pin down: her CV spans over 20 years and an impressively diverse range of live art presentations, research engagements and curatorial and advisory roles. Either side of her time in Adelaide will take in a residency in Perth (with the University of Western Australia’s School of Medicine and Pharmacology) and a performance in Fremantle (at October’s Proximity Festival for one-on-one intimate performance). Next year Jones will travel to the Institute for Art and Olfaction in Los Angeles where she will explore the creation of “bespoke and conceptual scents” for potential use in a performance context.

Jones’ current work is situated at the crossroads between art and science, and performance. I was fortunate enough to be one of only 15 people to experience her Somatic Drifts v1.0 at this year’s national artist hothouse Adhocracy [see RT122]. I was not alone in finding the sensory, one-on-one work which investigates interspecies empathy, to be a memorably affecting experience. Jones is still receiving feedback from audience members: “I’ve seen about five of the participants and each one has wanted to talk about the work again or say something about their experience and their memory of it. So I’ve had positive feedback in that way which is more ‘I really love that work’ or ‘thinking about it I can still feel it in my body.’ Someone I saw recently said they wanted to do it every week. They wanted to book into that experience.”

Cat Jones, Somatic Drifts v1.0; illustration by Cat Jones, remixed under Creative Commons Licence 4. Original images accessed via Wellcome Trust & Stephen Hale Vegetable Staticks, Google Books

courtesy the artist

Cat Jones, Somatic Drifts v1.0; illustration by Cat Jones, remixed under Creative Commons Licence 4. Original images accessed via Wellcome Trust & Stephen Hale Vegetable Staticks, Google Books

So is Somatic Drifts art or therapy? “I’m working on Somatic Drifts as an art experience and it’s informing my further research into neuroscience which in turn is feeding back into the work, but I’m not intending Somatic Drifts to be a therapeutic experience. It might lead to the making of experiences that clinicians could use in a therapeutic context.” Jones tells me that in contrast to performance works such as Somatic Drifts, therapy situations tend to be clinical and non-aesthetic: “They might look at touch and vision but they might not necessarily include sound in that environment or things like that so my question to the clinicians I’ve been talking with is ‘can an artistic approach into these situations enhance and move it forward even further?’”

One-on-one performances have a reputation for being confronting in their intimacy and the fact that participants often go in without an exact knowledge of what will happen or what they may be asked to do or discuss. Jones acknowledges this but emphasises the need for participants in her work to feel, at least initially, relaxed and receptive: “I begin with an element of creating a space for deep humour and they lead to great pleasure. However, they are also kind of uncomfortable situations, not necessarily confronting but certainly challenging. In Empathic Limb Clinic [the precursor to Somatic Drifts see RT121 and RT118], participants come into a very enclosed space with one other person and it’s a challenge to know that the performer is going to touch you. It’s uncomfortable for some people and I observe that process through performing—the fear in some people’s eyes—and being able to subtly manipulate that to the point where they barely notice the transition from us not touching to touching. The subversion of expectations as well is a key part of those things and that’s always part of the humour that has usually been my starting point for creating a work—humorous, offbeat, sometimes a little dark.”

At this year’s Proximity Festival Jones will be presenting Anatomy’s Confection, a new work about the anatomy of the clitoris as well as the censorial history of the clitoris’ representation in anatomy textbooks and medical curricula. Participants will create sculptural assemblages during the ten-minute performance. “It’s a topic that is rarely spoken about,” says Jones, “and I guess the language around the clitoris is rarely allowed so I wanted to create an experience that makes that open and also gives the participants a physical experience of that. Making something is a tactile way of taking the idea we are working with into someone’s own body. By making something you also create a sense of ownership over that and with that comes care and responsibility. So it’s going to be fun!”

–

Anatomy’s Confection by Cat Jones, Proximity Festival, Freemantle Arts Centre, 22 Oct-02 Nov 2014. http://proximityfestival.com/proximity-2014/program/; http://catjones.net

RealTime issue #122 Aug-Sept 2014 pg. web

David Rosetzky, Gaps, ACMI

courtesy David Rosetzky and Sutton Gallery Melbourne

David Rosetzky, Gaps, ACMI

Watching David Rosetzky’s new video work, Gaps, is not a passive occupation. One spends the whole time questioning: how much is this ‘performance’ and how much is it ‘real’? On a wall-sized screen, four dancers/performers and their words and gestures permutate and loop within two sparse rehearsal spaces; one white and daylit, the other lined by dark curtains. The viewer is drawn in close, ‘people-watching’ at intimate range, yet distanced by the seductive formality of every element in the frame.

Gaps is ‘people’ writ large: the camera, shooting in high definition, manufactures closeness, even in the wide shots, revealing the creases of lips, the knit of a t-shirt, strands of hair, fingernails. Performers share personal thoughts related to identity: about how they think the world sees them; or how they avoid conflict; or on living through a revolution. Over 35 minutes, then looping seamlessly back to the start, the same texts—based on interviews with the performers—are spoken by different bodies, disabling any hope of pinpointing who first said what.

Discussing Gaps, David Rosetzky says that the process of separating the text from its origin functions in a number of ways: “It allows it to be used in quite an experimental way rather than being tied to any particular truth…The transposition of a text from one subject to another, or being shared amongst a group of performers, is used in part to provoke questioning and potentially destabilise assumptions that the audience may have about any particular set of characteristics of the on-screen subjects.” Also destabilised is the logical opposition of spontaneous vs artificial, highlighting the blurs between how we speak and how we ‘perform’ ourselves.

Stephanie Lake’s choreography for Gaps gives physical form to what hangs in the air between the four performers. Fingers tremble or limbs fold, like unspoken sentences or manifestations of inner conflict. Rosetzky describes Lake’s approach as “beautiful, precise and intuitive…able to bring a range of different emotive tonalities, speeds and textures.” Rosetzky chose David Franzke as sound designer/composer for Gaps, for his “sense of connection with the performers…emphasising the various tonal shifts within the work.”

David Rosetzky, Gaps, ACMI

courtesy David Rosetzky and Sutton Gallery Melbourne

David Rosetzky, Gaps, ACMI

Gaps is technically accomplished—both slickly produced and intensely human; distancing yet intimate; cool but seductive. Its formal precision is unsettling, the performers smoothly ‘screened off’ from the viewer. And yet they are so near: presences that almost breathe, but without the work ever approaching the uncanny or immersive. Video lends itself to these qualities, says Rosetzky, in ways that live dance performance may not: “I think the moving image as a medium provides exciting opportunities to position the perspective of the viewer in quite dynamic ways. One can create a great sense of intimacy and connection to the performance through the use of different camera shots and movement. The shift between proximity and distance is something that I find very interesting to work with. The ability to create different speeds, rhythms and intensities is also something that appeals to me about working with the moving image.”

David Rosetzky, Gaps, ACMI

courtesy David Rosetzky and Sutton Gallery Melbourne

David Rosetzky, Gaps, ACMI

Removing the possibility of matching words to specific bodies also allows the questioning of “authentic subjectivity;” the opportunity to present “the idea of the self and identity as shifting and relative” and the creation of “a more fractured and unstable subject that is perhaps more difficult to identify.” says Rosetzky (ACMI program notes). In an interview he elaborates: “In Gaps I was interested in exploring identity as something that could be played out and explored by the cast in relation to each other and the camera. Rather than establishing characters as such, I wanted to present a range of subject positions that were never completely formed or held on to, but rather, operating more like possibilities—in flux and shifting between the different performers.”

The careful casting of two dancers (Lee Serle and Jessie Oshodi) alongside two actors (Rani Pramesti and Dimitri Baveas), has allowed Rosetzky to further shift and juxtapose personae and to explore sameness and difference in their representations on the screen, as they perform both alone and together. He says, “The work required that the actors had a facility for movement and similarly the dancers had to have experience in working with text. Other than this, I was keen for them to be clearly distinct from one another—both in terms of their appearance and also their particular qualities of performance…I am very interested in our desire to connect with one another and the way we attempt to negotiate the space between our selves and others.”

David Rosetzky, Gaps, Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI), 5 Aug 2014-8 Feb 2015; jointly commissioned by ACMI and Carriageworks; http://www.acmi.net.au/exhibitions/current/david-rosetzky-gaps/

RealTime issue #122 Aug-Sept 2014 pg. web

mumble(speak) live at FELTspace, Adelaide (2010)

courtesy FELTspace ARI, Adelaide.

mumble(speak) live at FELTspace, Adelaide (2010)

Hobart-based artist Matt Warren is a man of many guises. His website reveals 14 different “band names” (past and present) for his various musical projects and collaborations which range in style from shoegaze rock, doom metal, beats and dub to improv and field recording. His most recent album, III – real and imagined scenarios, is released under the pseudonym for his solo drone project, mumble(speak).

III – real and imagined scenarios offers 11 haunting meditations that are rich and multi-layered while maintaining a sense of ever expanding space; the depthless chasm of the unconscious perhaps. There is a timelessness to these pieces with little sense of urgent progression, yet they never succumb to stasis. The palette of sounds across the album melds recognisable midi and acoustic instruments with field recording and otherworldly sounds from unidentifiable sources. This is the first time Warren has used instrumental and sample contributions from other artists—Laura Altman, Carolyn Gannell, Felix Ratcliff, Mark Spybey and Sara Pensalfini—which he has interwoven subtly and effectively, particularly on the track “Loud as Ghosts.” “Entropic Flush” and “Departure” feature arpeggiated guitar which lends the album a folktronic flavour. Spoken text occasionally appears, sometimes as texture, sometimes as fragments of narrative and is generally well pitched and evocative with the exception of “silence” uttered at the end of “Entropic Flush,” which feels overstated. But as a whole, real and imagined scenarios presents a wonderfully dark and complex sonic world, offering equal parts pleasure and perturbation.

Gothic landscapes

The sonic other/underworld described by III – real and imagined scenarios could be seen to be indicative of Tasmania’s particular brand of gothic. I asked Warren (via email) to what extent he feels his work is influenced by the place where he resides.

“The gothic sense to Tasmania is not something I always notice; I mean living here you may just take much of it for granted and it’s probably harder to be objective about it than it would be for a ‘mainlander.’ But there would have to be something unconscious [here]. There is a dark beauty definitely, some pretty harsh landscapes, some bleak history. Much of my work deals with transcendental states, creating aural and visual environments that sit liminally between faith and rationality. The hauntological element is quite personal in a way, insomuch as it deals with my own history, but it’s a shared history, cultural mainly and likely generational. I utilise those elements, sound, music, images and so on in an abstracted way that allows others to get an empathetic sense of it without it being blatant [or] overtly personal. It becomes a kind of dreamscape. Perhaps Tasmania contributes to that.”

The Lull, light and sound installation detail (2010)

photo Matt Warren

The Lull, light and sound installation detail (2010)

Dream mediums

Warren began his artistic life as a painter and moved into sound and music. He describes his interest in sound as a medium: “I think I enjoy how it abstractly hits you, emotionally, cerebrally; how it can alter or enhance your mood and how it exists in the world—how it’s great in a gallery or a performance space, but does not need that framework to reach someone. I’m [passionate about] music in particular and sound in general.”

Warren also works frequently with video (most recently on the installation The Snowman with Sally Rees—see Partnering Art) and I asked him how he sees sound and moving image relating in his practice. “I think the projects define their own mediums. The relation between video and sound is often quite cinematic, insomuch as, regardless of how abstract the video is, the sound should have some kind of logic [in relation] to the image. In my formative years of art making, I often felt the sound kind of ‘finished off’ the video, but I don’t feel that way as much today and just as often I consider video will work just as well silent. Interestingly, I’ve been thinking that I would like to create sound works that could be accompanied by still images, photographs in a space or in a book. But often sound can be so immersive that it can create visual imaginings in the listener. Performance is another element insomuch as the nature of a physical being in the room brings with it a whole other presence and interactivity with the sound.”

Gathering dust and silence

In the last few years Matt Warren has also turned his ear and eye to curation. His motivation he admits is “as simple as wanting to see or experience something I haven’t yet seen.” In 2012 he undertook an emerging curatorial mentorship at Contemporary Art Tasmania (formerly CAST) resulting in the exhibition In A Silent Way that involved eight sound artists with all the sound works playing in the gallery simultaneously. Warren says he was thinking “about the issues of group media shows, how works can co-exist and still have their own space. I was also thinking about how noisy the world is and, as a kind of antidote to that, invited artists to make or contribute works designed to be played quietly, co-existing, quietly merging with each other and with the sound of the outside world.”

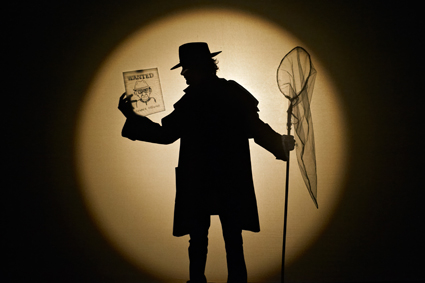

Last year Warren curated Ghost Hunters at the Plimsoll Galleries which at the time had been defunded and was not being used. He says, “I thought about [the] artists as kind of paranormal investigators, basically using sound and video of the empty, silent space to create works, trying to reveal something about the space, the residue of all that had come before.” The curatorial premise built on a methodology that Warren employed in his own work for his PhD that involved recording empty buildings, the duration dependent on the age of the building, then boosting the recordings by 200% to hear the sonic residue of the past.

Isolation and objectivity

While Warren has undertaken a number of travel fellowships over the years, including an Anne & Gordon Samstag Fellowship to do a Masters degree in Vancouver in 1999, he has never felt the need to leave Tasmania permanently to develop his practice. “I feel the local sound and contemporary art scenes are quite lively and have a sense of rigour. They are often nicely intermingled and probably due to the size [of the scene] are quite supportive of each other. And as far as I can tell, it’s always been that way. Obviously Tasmania has had a greater national and international art/music focus of late, but there has been a small but vibrant scene here for a long time. In the scheme of things, perhaps staying here has affected my career trajectory. Of course lots of show offers or exhibitions would always be nice, however I’m happy to follow my own path. I once wanted to move to a bigger city to live and work, but [now] I feel that cons would probably outweigh the pros. I don’t feel isolated here and there’s a nice degree of objectivity about the rest of the art/sound world that can come with just being a little removed from it.”

mumble(speak), III – real and imagined scenarios; http://mumblespeak.bandcamp.com/; http://roomofsilencerecords.bandcamp.com/; http://www.mattwarren.com.au

See also Matt Warren & Sally Rees in Partner Art and our review of Motel Dreaming by the Unconscious Collective of which Matt Warren is part.

RealTime issue #122 Aug-Sept 2014 pg. web