Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

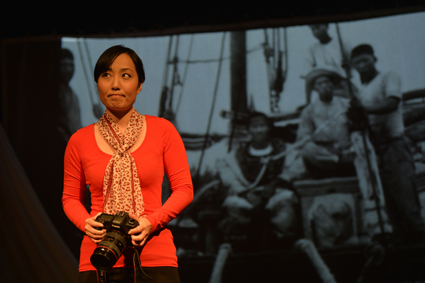

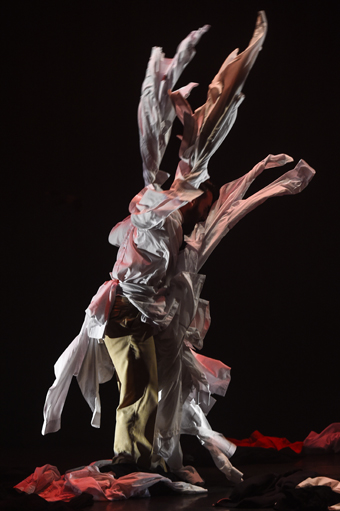

Eine Brise, Maurice Kagel

photo Jason Tavener

Eine Brise, Maurice Kagel

The second Bendigo International Festival of Exploratory Music (BIFEM) took place over a gloriously sunny weekend in the gold mining town of Bendigo. For those who have not visited Bendigo before (it was my first time), it is one of the best-preserved gold-rush towns in Australia with grandiose public buildings and sprawling parks. The Victorian public works somehow perfectly suited Australia’s most intense contemporary music festival.

It is not easy to ‘dip into’ BIFEM, as one is swept along a schedule of back-to-back concerts, panels, workshops and community events over three short days. The effect is ultimately challenging and stimulating, offering new perspectives on music to audiences, performers and composers alike.

Beyond the guest artists, the festival’s main attraction is its program of new and classic works of the 20th century curated by the festival’s Director David Chisholm. Geneva’s Vortex Ensemble brought an important theatrical inflection to the festival. Their first concert was a symbiotic dance of electronics and flesh as they performed naked in front of infra-red cameras in the Bendigo Art Gallery. The ensemble only performs new work, and usually that of ensemble members, so the next day we were treated to a concert of playful pieces by Swiss-based composers. In a valuable contribution to contemporary music theatre in Australia, Vortex staged Salvadorean composer Arturo Corrales’ piece Bug on Saturday night.

The festival was an opportunity to celebrate the dreamy lucidity of Melbourne’s Golden Fur, before they all rush off to California. Cellist Judith Hamann performed a solo recital combining installation art, lighting design and straight-up cello performance. Samuel Dunscombe teamed up with pianist Peter Dumsday to reboot the first ever piece for the Max program, Pluton. The pianist and composer James Rushford had several pieces performed in the festival, as well as performing a solo recital on the organ of the Sacred Heart Cathedral. Together, the group performed a surprisingly diverse and light-hearted program including works by David Chisholm, Anthony Pateras, Ivan Wyschnegradsky and others.

The festival’s house band, the Argonaut Ensemble, tried to inject some string culture and provided audiences with a rare opportunity to hear Grisey’s epic work Vortex Temporum under the baton of the award-winning conductor Maxime Pascal. Pascal’s energy was infectious, especially in Zipangu by the festival’s audience favourite, Claude Vivier.

Elsewhere the French composer Clara Maïda brought her charged electroacoustic atmospheres to the Bendigo Bank Theatre, piano virtuoso Zubin Kanga played a recital to infants and performance workshops were given by international superstar-flautist Eric Lamb and the Perth-based new music virtuoso clarinettist Ashley Smith. For musicology nerds like myself, the presence of Stockhausen’s teaching assistant and wide-ranging musicologist Richard Toop was a thrill. An all-star cast was imported (and retrieved, having flown the Australian coop) for the performance of Stockhausen’s music theatre piece Sirius, namely Nicholas Isherwood, Tristram Williams, Tiffany Du Mouchelle, Richard Haynes, with sound projection by Myles Mumford. Detailed reviews of these concerts can be read on my contemporary music blog Partial Durations.

This year the organisers decided to expand the discursive aspect of the festival with a series of lectures and discussion panels. To begin with, I had misgivings about the old-fashioned themes for the panels. “Duration and Durability” grew out of the performance of Morton Feldman’s six-hour String Quartet no.2 last year. “Wired” was to be yet another exploration of the place of electronics in contemporary music. Both were enormous successes, with the panellists and audience (both were convened more as open discussions than panels) quickly finding the contemporary resonance of the given topics.

After dancing around some different philosophical and musical definitions of duration (including some musing on the “adagio decade” of the 1970s by Toop) it became clear that the panel wasn’t very interested in the experience of extreme duration works, but wanted to know how and why one would compose with duration as a key consideration. David Chisholm saw one-idea pieces as fundamentally didactic, as sensitising the listener to a particular technique. Brett Dean raised the issue that a long piece exploring one idea was less risky because one had longer to find something that worked for any given listener. So much for the why, but how? Thomas Reiner brought up competing notions of “outside-in” and “inside-out” compositional strategies and James Rushford countered that either can fail and that what mattered was the intended effect. I would like to know whether composers have extended parts of scores because the ensuing moment didn’t ‘work’ without a longer preparation, much as certain effects in theatre don’t work before an hour or so has passed. The discussion foregrounded duration effects throughout the festival, making me ask what was being explored, what the intended pay-off was and whether the effect was interesting within the context of the piece.

The “Wired” panel quickly recognised the standardisation of music programming languages and technology today. This has led to a more fluid divide between engineers and composers, even though Clara Maïda pointed out that there are still many pieces with new technology and old art (as we were reminded when we heard Pluton). The panel used notions of technique and technology fairly interchangeably, but it is evident that there is often a lag or plain divide between compositional strategy and available music technology. The contemporaneity of technology and technique became a useful frame for evaluating the electronic contributions to some of the later concerts. The final question for the panel, “What do you want in the future?” dashed any hope of a greater integration of the two, with such technology-fetishist answers as “flying speakers” and “morphing nanotech mallet heads” (though both of those would be cool). At 90 minutes the discussions were just beginning to get interesting and I can only hope that these sessions are given two hours next year.

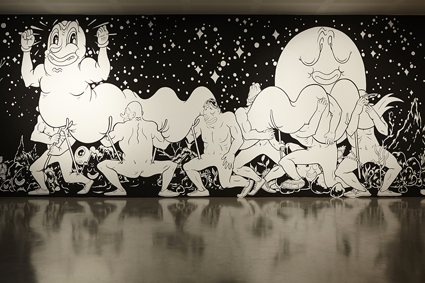

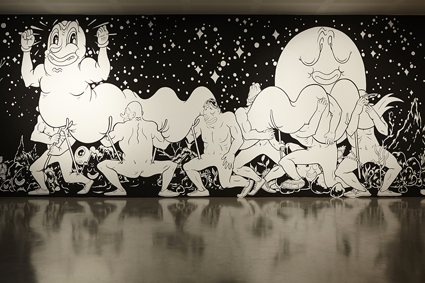

Two wonderful events took the festival outside of the concert halls and into the community. A performance of Mauricio Kagel’s Eine Brise, a “transient action” for 111 bicycles saw a much smaller peloton circle the Tom Flood velodrome whistling, singing and ringing their bells to the cheers of a few dozen supporters. The colourful and ultimately hilarious sonorous sculptures produced during Dale Gorfinkel’s children’s workshop were opened as an installation on Saturday, allowing adults to navigate a maze of interconnected bellows, balloons and bells.

A duration experience in itself, the marathon of BIFEM induces moments of delirious rapture, but also shortens one’s temper enough to provoke important questions such as, “Is this piece really worth my time?” Thankfully David Chisholm’s curatorial nous rarely leaves one with a negative answer.

Bendigo International Festival of Exploratory Music, Bendigo, 5-7 Sept

See Partial Durations for more reviews of BIFEM.

RealTime issue #123 Oct-Nov 2014 pg. 41

© Matthew Lorenzon; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

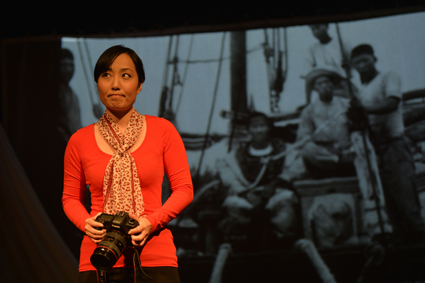

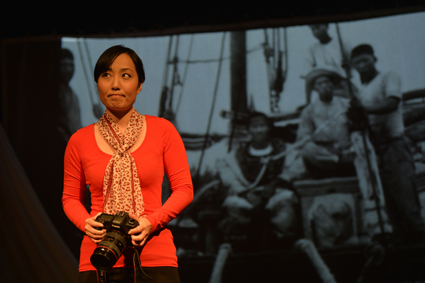

Atlanta Eke, Body of Work

photo Gregory Lorenzutti

Atlanta Eke, Body of Work

The importance of the Keir Choreographic Award cannot be underestimated in the challenging climate in which independent choreographers work in this country. The prizes not only alert us to emerging talents and reward them with heightened visibility and cash (the Judge’s award, $30,000; the People’s Choice Award, $10,000) but perhaps the Award also signals where contemporary dance is headed. The latter, moreso than the winners, was the subject muttered about in the Carriageworks foyer after the awards announcement, as it was during Performance Space’s SCORE season (see pp19-23).

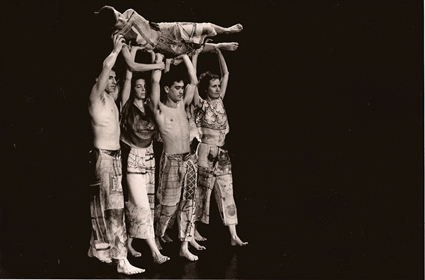

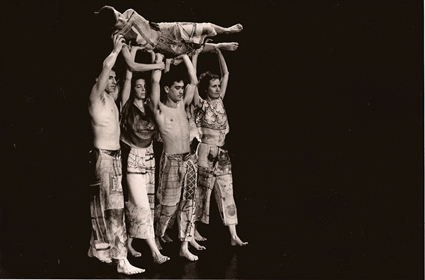

I can’t recall when I’ve heard, post-show, so much uncritical enthusiasm on the one hand and scorn on the other. There were eight semi-finalists: Sarah Aiken (VIC); James Batchelor (VIC); Tim Darbyshire (VIC); Matthew Day (VIC); Atlanta Eke (VIC); Shaun Gladwell (NSW); Jane McKernan (NSW); and Brooke Stamp (VIC); their works were performed at Melbourne’s Dancehouse. The works of the four finalists Aiken, Eke, Day and McKernan were on show at Sydney’s Carriageworks. (Perhaps the next showings should be telecast from one venue to the other.) What triggered debate was form. Award-winner Atlanta Eke’s Body of Work was even less a dance work than Monster Body, her much acclaimed segueing of dance, performance art and installation. Body of Work’s media dimension—the performer’s manipulated view of her ‘actual’ and virtual selves—suggested potential which the Award money might help realise.

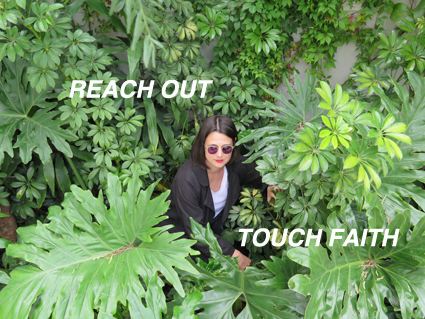

Carli Mellow, Angela Goh, Leeke Griffin, Lizzie Thomson, Mass Movement, Jane McKernan

photo Gregory Lorenzutti

Carli Mellow, Angela Goh, Leeke Griffin, Lizzie Thomson, Mass Movement, Jane McKernan

Matthew Day’s Rites (a take on Nijinsky’s The Rite of Spring) was critically limited by its short duration and an awkward dramatic structure, but the work did spring from his body, as ever not looking like any dance we’ve seen, for which I’m grateful. Sarah Aiken’s Three Short Dances was Bauhaus-lite, more installation than dance, its large geometric shapes moving unrevealingly and the artist’s balancing of long poles on head, hands and shoulders aesthetically inexpressive. Jane McKernan’s Mass Movement was based on an improvisational structure which gave the work cogency, a great sense of nervy fluidity (suspenseful even as we waited for various patterns to resolve into a singularity of purpose) and featured actual dancing. McKernan won the audience vote (if foyer talk was anything to go by, Eke was also highly popular).

If there was a shortage of remarkable dancing in the final of the Keir Choreographic Award, there were ample signs of a young generation’s preoccupation with the body relative to its mediatised self, states of being, game structure and installation, none of them particularly new but certainly warranting renewed and regenerative investigation. Matthew Day (as evident in previous works) is the most idiosyncratic choreographer but his durational approach doesn’t mesh well with a competition requiring 20-minute creations (he came in around 10 minutes). Although conventional notions of dance haven’t figured highly in the finals, there are choreographic sensibilities at work, if not to everyone’s taste.

Expressions of disgruntlement centred on a perceived appropriation of dance by other art forms, not least the electronic arts, hence disappointment at the selection of video artist Shaun Gladwell as a semi-finalist (the award is open to non-dance artists who don’t necessarily even work with dancers) and irritation with Atlanta Eke’s limited movement palette and a po-mo overload of references that don’t add up to dance. Ironically, the movement to centre-stage of other practices in dance has been fostered by a generation of successful Australian choreographers who have fruitfully collaborated with photographic, video, sound, fashion, music and installation artists to yield aesthetically and intellectually ambitious works in which dance is primary but at the same time one part of an array of forces corralled by artists who describe themselves first as directors, then as choreographers.

There are dance artists and followers who feel that dance is being buried alive beneath other artforms—or displaced by notions of what constitutes art. Therefore, Natalie Abbott’s Maximum is not a dance work, it’s ‘just conceptual;’ Antony Hamilton’s Keep Everything is ‘over-blown,’ ‘tricksy dance theatre’ (although the dancers’ virtuosic skills are much admired, as if not choreographed), but Narelle Benjamin’s Hiding in Plain Sight is ‘the real thing’—entirely a dance work, one comfortably rooted in the lyrically fluent modern dance tradition of the last century, if blessed with the choreographer’s idiosyncratic demands on the body’s flexibility. Angst has also been expressed about recent works by Philip Adams and Luke George (page 26) which evoke ritual, the spiritual and the paranormal, their creations more akin to live art than dance. Is dance about to go missing?

Modernism’s challenge to ballet early in the 20th century and the Postmodern upheavals of the 1960s are still being felt in an artform which is at once born of highly disciplined, inherently conservative training, often from childhood, and a sometimes surprising openness to experiment. A desire for purity of expression has been central to these movements, expression freed of theatricality, narrative and psychologising—pure dance, of itself and nothing more. The Trisha Brown: From All Angles (see p15) program in the Melbourne International Arts Festival in October will track the evolution of this artist’s seminal aesthetic from un-dancerly performance art-like events to highly integrated, collaborative stage works—without Brown ever abandoning first principles.

Dance in the early 21st century is hugely diverse, complex and rampantly hybrid; it’s not surprising that there’s a desire to return to something essential (as in certain improvisational practices) or to at least further the abstraction and clarity of line in the dance of the second half of the 20th century with its entwined lineage of ballet, Modernism and Postmodernism.

Is a (mostly) generational battle looming over form and a perceived subordination of dance to other forms, or was it just a Sydney thing—in a state without a major dance school, with small university dance courses under threat and inordinately strong competition for arts funding? Given the unusually passionate, if not loudly expressed, opinions about the Keir Choreographic Awards (predictably there were complaints about the appropriateness of the judging panel, which included Mårten Spångberg, “the acclaimed ‘bad boy’ of [European] contemporary dance” [press release]), it would be healthy for the Sydney dance scene, and beyond, if these views were publicly discussed rather than rumoured. Was there dancing? Will there be dancing?

It is critical, from time to time, to ask what constitutes dance and how it renews and extends and even perhaps limits itself—as in the 90s with the incorporation of a greater range of body regimes and technologies. Interviewed in Bodies of Thought: 12 Australian Choreographers (RealTime-Wakefield Press, 2014), choreographer Helen Herbertson says, “…there’s such an enormous scope for dance to be applied. I almost feel like it’s lost a kind of specificity of being about physicality… So I think we are slightly in danger of dance looking like it’s just a kind of tool to be used. I’m waiting for a kind of re-flowering of really specific, particular detailed language.”

Congratulations to Atlanta Eke and Jane McKernan and to Phillip Keir and his partners, Carriageworks and Dancehouse, for bravely supporting emergent choreography in whatever form it takes. Long may the Awards persist and, like many an art prize, controversially test our collective taste and judgment.

–

Carriageworks, Dancehouse and The Keir Foundation: Keir Choreographic Award, finals, Carriageworks, 17-19 July; Performance Space, SCORE, Carriageworks, Sydney, 1 Aug-7 Sept

RealTime issue #123 Oct-Nov 2014 pg. 29

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

At Carriageworks on September 12, we celebrated 20 uninterrupted years of RealTime—its writers, editors, staff and clients, our Open City Inc Board of Management (publisher of RealTime) and especially our readers, supporters and the artists we treasure.

The evening commenced with the launch of Bodies of Thought: 12 Australian Choreographers, jointly published by RealTime and Wakefield Press. Choreographer Sue Healey, one of the book’s subjects, spoke of its importance for her and Carin Mistry (Dance, Australia Council) launched it. The editorial duo, Erin Brannigan and Virginia Baxter, thanked contributors, reflected on their labours of love and mused over some of the big questions about Australian dance the book confronts.

The birthday celebrations proper commenced with speeches of reflection and congratulation from Open City Chair Tony MacGregor, sponsor Andrew Findlay, Managing Director, Vertical Telecoms (Vertel) and Andrew Donovan, Director, Emerging & Experimental, Australia Council. Managing Editors Virginia Baxter and Keith Gallasch reciprocated with a curated suite of 20 one-minute performances (one for each of our 20 years) gifted to RealTime by Nigel Kellaway, Julie-Anne Long, Edward Scheer, Felicity Clark, Amanda Stewart, Nalina Wait, post [Mish Grigor, Natalie Rose], Miranda Wheen, Caroline Wake. Katia Molino, Ruark Lewis, Clare Britton & Matt Prest, Gail Priest, David Williams, Jason Noble [Ensemble Offspring], Vicki Van Hout, Rosie Dennis, Sam James and Keith and Virginia themselves, to a sound score by Gail Priest.

Thanks to all who spoke, performed and attended and to the generous Carriageworks team. This was a wonderfully affectionate and truly communal celebration.

Virginia, Keith, Gail, Katerina & Felicity

Clockwise from top right – Tony MacGregor, Open City Chair; Virginia Baxter and Erin Brannigan; Annemarie Jonson, Alessio Cavallaro, former OnScreen editors, photo Sandy Edwards; writer Edward Scheer, writer and former contributing editor Jacqueline Millner, photo Sandy Edwards; Keith Gallasch & Virginia Baxter

Clockwise from top rightMiranda Wheen, Nalina Wait, Mish Grigor & Natalie Rose, Vicki Van Hout, Jason Noble, Katia Molino

RealTime issue #123 Oct-Nov 2014 pg. 30-31

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

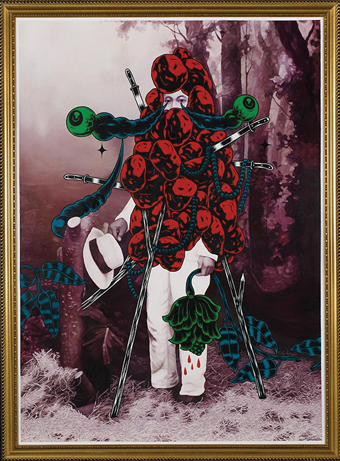

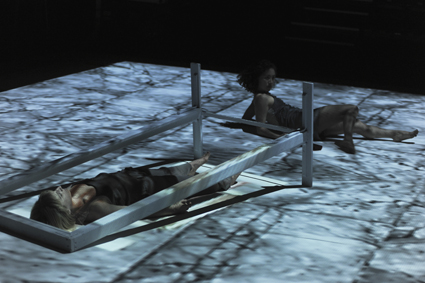

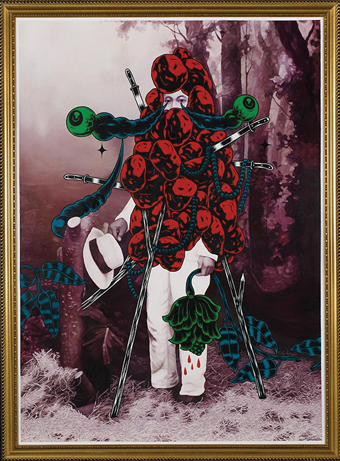

Sacha Cohen, The Three Minute Bacchae and other Extreme Acts, 2008, PACT

photo Heidrun Löhr 2007

Sacha Cohen, The Three Minute Bacchae and other Extreme Acts, 2008, PACT

For 50 years Sydney’s PACT has been a seedbed for artists of all kinds, most recently those engaging with contemporary performance and live art. In the late 60s and early 70s it was a vital hub for folk music, adventurous theatre (a multi-site production of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt) and happenings. In following decades it focused on youth theatre.

Nowadays titled PACT Centre for Emerging Artists, the organisation “supports, produces and presents interdisciplinary and experimental performance work by emerging artists from diverse backgrounds…providing a space (its home theatre in Erskinville in Sydney’s inner West) for artists, where all aspects of experimental performance can converge in a vibrant and holistic community.”

Originally housed on the edge of the Sydney CBD, near Darling Harbour, PACT was founded by a group led by Robert Allnutt, Jack Mannix and Patrick Milligan in response to the Federal Government’s Vincent Committee Report that “highlighted the dire state of Australia’s performing arts, film and television industries.” This was at a time when the arts landscape was thinly populated, largely prior to the emergence of state and independent theatre and dance companies in the late 60s and into the 70s and of an incipient film industry. PACT (Producers, Authors, Composers and Talent, and later Producers, Artists, Curators, Technicians) aimed to develop a range of practitioners who would enrich Australian culture.

Alumni include a kaleidoscope of significant names in Australian arts and entertainment including Peter Weir, Graham Bond, Zoe Carides, Lara Thoms, Matt Prest, Mish Grigor, Natalie Rose and Zoe Coombs Marr (post), Malcolm Whittaker, Alison Richardson, Augusta Supple, Sally Lewry, Ashley Dyer, Nick Atkins, Natalie Randall, Daniel Prypchan, Jane Grimley, Caroline Wake, Amity Yore and Ling Zhao. PACT has yielded directors, performers, writers, curators, choreographers, filmmakers, digital media artists, sound, lighting, set and costume designers, technicians, artistic directors, cultural producers and marketing managers.

As the cultural landscape transformed over 50 years, so too did PACT, focusing in recent decades on young and then specifically emerging artists—ranging from late teens well into their 20s, eager to learn, collaborate and engage directly with the public while on the cusp of their careers.

The PACT IS FIFTY birthday audience will be addressed by Lord Mayor of Sydney, Clover Moore, and entertained by past and present PACT artists and artistic directors (who have included Caitlin Newton Broad, Anna Mesariti, Cat Jones, Julie Vulcan and now Katrina Douglas). There’ll also be screenings of rare archival footage and the launch of PACT’s 2015 program.

In RealTime 124 we’ll report on the celebrations and take a close look at PACT’s distinctive history and the breadth and depth of its sense of community. A visit to the Previous Events pages of PACT’s website offers a glimpse of a decade of engagement with young artists, arts organisations, festivals and communities. An extra 40 years adds up to a remarkable achievement.

PACT IS FIFTY, PACT, 107 Railway Parade, Erskineville, Sydney Saturday 18 Oct 6-9pm

RealTime issue #123 Oct-Nov 2014 pg. 32

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

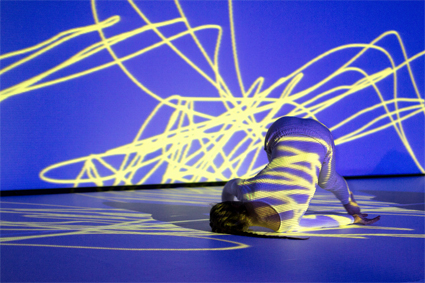

Nerve Engine, Bonemap

photo Tai Inoue

Nerve Engine, Bonemap

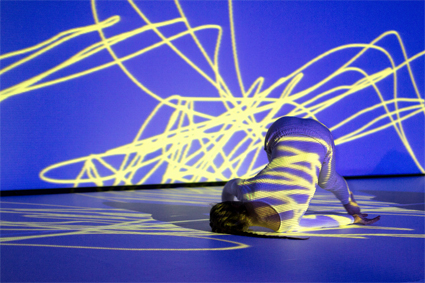

Bonemap invites one audience member every 15 minutes to participate in Nerve Engine. Designed to ensure a very personal experience, this interdisciplinary and immersive one-on-one format has been perfected by this Cairns-based company (new media artist Russell Milledge and performer and co-creator Rebecca Youdell) over the past four years.

The installation is made up of two large round netted and transparent scrims hanging from roof to floor in a darkened room. The participant, with an iPhone attached to the back of their hand, stands inside one scrim while the other, four metres in front, is empty.

I’m immediately submerged in an environment of sound and image. Four double projectors fill the corners of the room with digital imagery, all of which is stitched together by software developed by Milledge. At the same time I’m engulfed by a 4.1 sound system. The work is coordinated by Milledge from a control desk behind me. Along with the programmed light and sound, an extra layer of sound is triggered by the iPhone—influenced by my movements.

As Nerve Engine begins, a spotlight illuminates a dancer, Youdell, in a brilliant red dress dragging a treasure chest. She too has an iPhone attached to her hand and I’m gently enticed into a duet of movement, finding myself imitating her arm movements. Then through a series of gestures she almost becomes my puppet as I guide her into the chest and she disappears.

The experience lasts for approximately 10 minutes and crescendos with loud, all-encompassing drumming while the performer reappears making frenzied movements in a red tutu.

The images projected on the participant’s scrim are elemental—water, air, smoke and flames. At times there is sensory overload—images are layered, the sound is engulfing and attention repeatedly drawn to the performer—theatrically lit and always garbed in red: the red of blood, the life force and nerve engine of the work.

With Youdell suspended in space like a lab specimen in the middle of the second scrim, the work concludes with a projection of the dancer in the stance of Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man, linking Nerve Engine to Bonemap’s ongoing exploration into the relationship between body and universe.

Most impressive is the way image, sound, light and action combine seamlessly, the result of clever use of technology alongside physical performance. As a participant I come away feeling privileged to have been part of a unique experience—a performance orchestrated just for me.

2014 Cairns Festival, Nerve Engine, director, scenographic design, media Russell Milledge, co-director, choreographer, performer Rebecca Youdell, sound design Steven Campbell, programmer Jason Holdsworth; Cairns Entertainment Centre, 26-30 Aug

RealTime issue #123 Oct-Nov 2014 pg. 32

© George Dann; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Billy McPherson, Roslyn Oades, John Shrimpton, I’m Your Man rehearsals

photo Heidrun Löhr

Billy McPherson, Roslyn Oades, John Shrimpton, I’m Your Man rehearsals

There is a certain self-consciousness that comes over a writer when faced with interviewing an artist who conducts, edits and restages interviews for a living. I speak, of course, of Roslyn Oades, a Sydney-born, Melbourne-based artist who has spent more than a decade pioneering the form she calls “headphone verbatim.” [Actors are fed edited audio via headphones which they reproduce with precision. Eds.]

Though we have talked previously, about everything from the merits of supra- versus circum-aural headphones to the ethics of sharing other people’s stories in performance, when I get the brief for this article it occurs to me that we have never really discussed gender. What follows derives from a telephone conversation we had on the evening of September 4, four days before Oades went into rehearsal for her latest project, Hello, Goodbye & Happy Birthday, which will premiere at the Melbourne Festival on October 9.

Art, theatre, voice, installation

Oades identifies four paths or practices that have led her to this moment, starting with her formal training at the College of Fine Arts at the University of New South Wales in the early 1990s. COFA had only recently merged with UNSW and Oades was among the first students who could take art classes at Paddington as well as humanities subjects at the main campus in Kensington. She speaks fondly and proudly of training in photomedia with Anne Zahalka and in theatre with John McCallum, among others. This would be more than enough for most students, but Oades also wanted to explore acting, leading to the second strand of her practice. While still at university, Oades won a guest role on A Country Practice, where she huffed and puffed her way through a teen pregnancy and labour.

Once she had graduated, Oades continued to work in television, doing small guest roles on shows such as Police Rescue (“Leah Purcell and I were rookie cops together”) before landing a larger role on Home and Away. From 1996 to 1998, she appeared in 25 episodes as Kylie Burton before being arrested at the altar and then dying of a drug overdose in prison. Such plotlines did not so much plant the seeds of doubt, as water them; Oades was still living in Bankstown, trying to reconcile its diversity with the very white world of Summer Bay, and wondering how she might go about making her own work. So she called the Bankstown Community Arts Officer, Tim Carroll, and asked him about what he did and how he got his job. Working with Carroll at the Bankstown Youth Development Service allowed Oades to start Westside (a publication for emerging writers from the western suburbs), investigate installation art (“we filled an empty bank with gravel”) and also introduced her to Alicia Talbot and Urban Theatre Projects, which would in turn lead to her first full-length theatrical production.

In the meantime, she had also started cultivating the fourth strand of her artistic practice—voice work. In 2000, her interest in voice took her to the United Kingdom, where she recorded every accent she could while also training and working with Mark Wing-Davey and his Non-Fiction Theatre company. She came home the following year to voice the character of Tracey McBean in the children’s program of the same name. More acting work followed, but when she appeared on All Saints for a second time, eight years after the first and playing yet another infanticidal mother (“I think I’ve killed six babies and a mother during my career”), she decided she’d had enough.

Headphone verbatim theatre

Oades’ first work, Fast Cars & Tractor Engines (2005), started life as the Bankstown Oral History Project. In 2000, she helped three young artists from the area perform some excerpts for the project’s launch. Two years later, she directed a 15-minute version for Urban Theatre Projects’ Short and Sharp season; three years after that, a full-length production premiered at the Bankstown RSL, to immediate and effusive praise (see David Williams in RT70). Since then Oades has made four more headphone verbatim works, including Stories of Love & Hate (2008; RT89) and I’m Your Man (2013; RealTime 117, Darwin Festival Feature).

While Oades calls these three plays her Acts of Courage trilogy, and Currency Press is about to publish them in a volume with that very title, I sometimes think they could just as easily be called the Australian Masculinities trilogy. It is fascinating to hear men from Bankstown, Cronulla and beyond trying to impress each other as well as their female interviewer while talking about love, violence and sacrifice. In I’m Your Man in particular one is often struck by the fact that Oades must have been the only woman in the room, moments before the big fight, trying to capture what she calls “adrenaline on tape.” Of course masculinity becomes all the more intriguing in performance when an actor like Katia Molino conjures it with a mere shift of the leg and tilt of the head. This “gap,” as Oades often calls it, between an actor and their character’s gender, race, ethnicity and age, is absolutely key to headphone verbatim if it is to be anything more than a “style.” For Oades, headphone verbatim is more than a theatrical “texture or technique;” it is a “dramatic device that enables us to think about who’s allowed to say what in Australia.”

The mention of masculinity brings us to gender more broadly and how it has shaped her career. Oades tells me how “at the start of every show, I have to be talked into making it; I feel as if I have an idea but I’m not sure if it’s any good.” Happily she has always been persuaded, but having sat in on artist pitching sessions since, she thinks that this is not a personal but rather a structural issue: male artists seem “better at stepping forward” whereas women often present themselves as “team players” and thus come across as less confident. On the contrary, when a woman is confident, and does pursue her artistic vision with the same focus as one of the many feted young men, she can be perceived as “difficult” or “demanding.” These insights have arrived in part thanks to Oades’ time as Malthouse Theatre’s Female Director in Residence in 2013. Like Anne-Louise Sarks (RT116), who was in residence at Malthouse in 2011, Oades is acutely aware of being in the “right place at the right time:” next door to Urban Theatre Projects when it moved to Bankstown; ready to take a production from the margins to the mainstream when Belvoir came knocking; and in Melbourne when Malthouse initiated its scheme. Indeed, it was there that she started work on her current project.

Hello, Goodbye & Happy Birthday, a Melbourne Festival Malthouse premiere headphone verbatim work drawing on responses from 18- and 80-year-olds, is not the first piece she has done outside the Acts of Courage trilogy—that was a Vitalstatistix commission, Cutaway: A Portrait (2012). It is, however, her first project without Katia Molino and Oades admits to feeling slightly lost without her. Perhaps this is why she thinks that this might also be her last headphone verbatim piece, at least for a while. She says she is interested in continuing audio work but without actors. One possibility involves the audience listening to recordings or re-enactments of conversations say, between a father in prison and the son who is allowed to speak with him for 12 minutes each week.

She’s also interested in creating an immersive piece, bringing her full circle back to those Bankstown installations all those years ago. When I ask Oades about what binds the many aspects of her practice, she says simply “storytelling,” to which I would add “listening”—a vital skill for every woman in a world of “mansplaining” (see Rebecca Solnit’s essay “Men Explain Things to Me” if you haven’t already (www.tomdispatch.com).

But do not confuse listening with passivity. Roslyn Oades says she loves nothing more than “disappearing in a room, when everyone else is speaking and I’m listening. I can look quite mousey and inconsequential, but really I have a microphone. I’m recording and that’s a very powerful thing.”

Melbourne Festival & Malthouse, Roslyn Oades, Hello, Goodbye & Happy Birthday, Malthouse, Melbourne, 9-26 Oct

RealTime issue #123 Oct-Nov 2014 pg. 33

© Caroline Wake; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Eurydice, Red Stitch

photo Jodie Hutchinson

Eurydice, Red Stitch

When a performance purports to speak to a reality outside of itself, it’s fascinating how often we put absolute faith in that claim.

I’m not referring to the more profound ontological questions raised by philosophers and undergrad theatre alike, but the simple way in which we accept the honesty of an artist who apparently draws on experience, or presents something based on research, or includes found material, quotation or documentary. This is a good thing—think how much would be lost if we approached all art with paranoid suspicion—but it’s also just one of the many, many clauses in the unwritten contract we tend to agree upon in the creative sphere.

Red Stitch, Eurydice

US playwright Sarah Ruhl’s Eurydice maintains a very clear connection with a reality external to its fictional world. It retells the myth of Orpheus from the perspective of his wife, but in doing so also warps the story through an autobiographical lens. It’s a compelling proposition—merging a form of writing in which fabrication is almost unforgivable with a mythology that works on symbolic, allegorical and fantastic levels. When Eurydice arrives in the Underworld she finds her dead father there, but while her memory of him has been washed away by the river Styx, his own recollections have been imperfectly removed and he is able to reawaken their relationship.

Ruhl’s own father died of cancer in 1994 and the more effective elements of Eurydice deal with a similar loss. Nowhere in the play is explicit reference to the playwright’s own life made clear, but it is difficult not to read as honest her focus on retrieving something of one’s parent from the afterlife. This untenable quest is made possible by language, poetry, drama, imagination and, in the final telling, does not end well. Orpheus himself is mostly a supporting player in this retelling, and so it comes as no surprise that the reason Eurydice does not return with him to the waking world is here a result of her own actions. This is no soothing balm, of course, and to Ruhl’s credit she ensures that the tale remains a tragedy.

Red Stitch’s production brought out much of the work’s nuance and was commendably performed, with Ngaire Dawn Fair and Alex Menglet offering especially fine turns as Eurydice and her father, respectively. But the show’s strengths also highlighted its shortcomings, and were a reminder that this is a relatively early work in the playwright’s career. A trio of stones acts as Chorus in a manner not much beyond what you’d find in a high school exercise, and Hades’ earthly form as a “Nasty Interesting Man” suggests the way that rich and resonant mythology is made saccharine and twee here.

This is a recurrent characteristic of Ruhl’s writing: the invocation of grand themes such as love or death before a retreat into cliché or convention. It’s perhaps also why her works are so popular on mainstages around the world. They’re not particularly challenging, and seem construed not to elicit soul-shaking emotion from audiences but to simply meet the criteria desired by this play’s lord of the underworld—that of being “interesting…”

Lara Thoms, Liz Dunn, The Last Tuesday Society

photo Theresa Harrison

Lara Thoms, Liz Dunn, The Last Tuesday Society

The YouTube Comment Orchestra

By some coincidence, the first ever comment made on YouTube was just that: the word “interesting….” (followed by that infuriating four-dotted ellipsis). That’s if we’re to take as truth the delicious monologue that opens The Last Tuesday Society’s The YouTube Comment Orchestra. MC Richard Higgins walks us through the unexpectedly tortuous mystery of that first comment and its later disappearance, and the hilarious soliloquy is the perfect justification for a full 90 minutes dedicated to the truly bizarre phenomenon of online commentary.

What follows is a series of performances by a range of artists taking the notion of the online comment as a provocation. Last Tuesday co-creator Bron Batten herself enters into an online argument about a booty-shaking Nicki Minaj music video, interviews young people on the subject and finally presents an hilarious animal-suited dance routine. Post’s Mish Grigor delivers an art therapy experience that turns weirdly erotic and gently uncovers the role of power in the commenter’s relationship with her subject. Lara Thoms and Liz Dunn recreate notorious performance art videos and compare the responses of professional critics with those of confused or bemused online commenters.

These and other sequences don’t add up to any coherent thesis; the Society’s regular mission has always been to seek out polyphonic responses to a theme, rather than curating some kind of harmonic ensemble. There is a subversive overall effect to this otherwise light laughfest, however. Though we all know that a comments section is where good thoughts go to die, the comments themselves oddly emerge as the heroes of this work. For all the humour and odd-thinking these artists bring to the stage, many of the biggest laughs come from anonymous internet users mocking art in ways that are themselves wonderfully wry.

Michelle Ryan, Vincent Crowley, Intimacy, Torque Show

photo Rachel Roberts

Michelle Ryan, Vincent Crowley, Intimacy, Torque Show

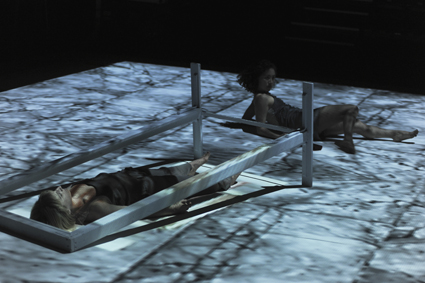

Torque Show, Intimacy

Torque Show’s Intimacy is another work that draws much of its power from a real-world circumstance given creative treatment. Dancer Michelle Ryan was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis at age 30, and this work makes viscerally apparent the effects of the condition on the dancer’s own body. In solos and duets with Vincent Crowley, the exertion and focus Ryan requires in order to simply cross the traverse playing space is both painful to watch and impossible not to grasp. As with so many contemporary works that feature a performer with some kind of disability, this work is not ‘about’ that disability but also not able to exist without it.

Ryan relates humorous or dark dreams she may or may not have had; Emma Bathgate belts out sensational jazz numbers; duo Lavender vs Rose provide occasional accompaniment. The work, again, doesn’t necessarily add up to a coherent whole, but Ryan’s engaging presence and, especially, a number of stirring moments of what appears to be genuine intimacy are more than enough to keep this experience alive in the mind for some time to come.

Red Stitch Actors Theatre, Eurydice, writer Sarah Ruhl, director Luke Kerridge, performers Ngaire Dawn Fair, Olga Makeeva, Dion Mills, Johnathan Peck, Alexandra Aldrich, Sam Duncan, Alex Menglet, 3 Sept-4 Oct; Last Tuesday Society, The YouTube Comment Orchestra, co-curators, performers Richard Higgins, Bron Batten, performers Zoey Dawson, Nicola Gunn, Mish Grigor, Grit Theatre, The List Operators, Telia Nevile, Lara Thoms, Malthouse 17-27 Sept; Torque Show, Intimacy, by Michelle Ryan, Lavender v Rose, director, choreographer Ingrid Weisfelt with Ross Ganf, performers Michelle Ryan, Vincent Crowley, Emma Bathgate, Malthouse Theatre, Melbourne, 13-23 Aug

RealTime issue #123 Oct-Nov 2014 pg. 34

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Casus, Finding the Silence, photo Sean Young, SYC Studios

The perilous follow-up to a smash hit is the subject of David Burton and Claire Christian’s new play Hedonism’s Second Album for La Boite Indie and the reality for Brisbane circus collective Casus (Emma Serjeant, Jesse Scott, Lachlan McAulay & Vincent Van Berkel). Finding the Silence is the latter’s follow-up to their internationally acclaimed Knee Deep and there was a palpable sense of anticipation at the Judith Wright Centre premiere.

Director and ensemble member Jesse Scott described the show as being about “that moment of inner silence before every trick…In that moment of solitude you are truly alive and aware, defying danger, fear, gravity.” Program notes can sometimes be abstruse or pretentious but in typical Casus understatement, these words sum up beautifully the experience of watching the show and its aesthetic of austere and vulnerable contemplation. Unlike the warm earth and honey tones of Knee Deep, Finding the Silence has clearly been infected by the white lights of hotel corridors, the low horizons of European winters and the craving for stillness in a ‘whirlwind’ of touring.

The work begins with a stripped-back stage, covered by a long rectangular training mat and a bank of lights to the right. Dan Carberry’s subtle score works underneath the action of the bodies, almost imperceptibly, resisting dramatic peaks and at key moments in the show almost falling away, like sound sometimes does when you close your eyes. You watch, engrossed as the flow of bodies passes before you, solo and duo mostly, with two or three climactic group routines that mark the half-way and then the endpoint of the show.

While founding Casus member Natano Fa’anana is sadly missed due to injury, newbie ensemble member Vincent Van Berkel maintains the intense, almost loving complicity that exists between each member of Casus. You feel like you are watching private moments as the tricks build from sequences on the mat to a bench and a gobsmacking aerial routine. There are blindfolds, cartwheels and spinning bodies. Yet somehow each extraordinary sequence, while it showcases a gently implacable strength from each of the performers, eschews the razzle-dazzle of ostentatious circus ‘stand and deliver’ tricks. The show felt to me like circus for circus-makers: complex, self-referential and tautly disciplined.

This is such a brave choice for that critical follow-up work. Casus has not sought to repeat a formula for success, to regurgitate Knee Deep in any discernible way. The sequences felt fresh and distinctive and this is the hallmark of true artistic risk-taking. While I suspect that Finding the Silence may not have the same popular appeal as Knee Deep it cements Casus’ place in Australian circus as a powerhouse of innovation, risk-taking and integrity.

Hedonism’s Second Album, La Boite Indie

Another new powerhouse on the local Brisbane scene is the playwriting team of David Burton and Claire Christian. Hedonism’s Second Album follows Sumo, Chimney, Michael and Gareth and their rapacious band manager Charlie as she pushes them to pump out their second album in the space of a week to placate their furious record company after a recording of the band trashing the studio appears on the internet.

The show belts along at rapid-fire pace. Band members harangue, comfort, confess to and manipulate one another. The unreconstructed Australian male drummer, Sumo, steals the show with all the best lines and a surprising tenderness for his closeted band-mate, Michael, who is unable to break away from a violent relationship. Yet the other men, ostensibly less damaged, seem to evade deeper investigation. I think this is because the plot is driven largely by band clichés, aka the lead songwriter wants to go solo, the drummer isn’t good enough and the girl breaks up the band (almost). What lifts the work into something arresting is both the superb directorial work of Margi Brown Ash and the quality of the writing. Ash makes the bodies on stage seem one beast, moving, snarling, bouncing, holding each other with fierce intensity. This is matched by a vernacular that sounds like flat naturalism but is rich with a kind of generational cadence—an attack that exploits the vernacular of band grunge and pushes it into a dark poetry of masculinity in crisis. Both Finding the Silence and Hedonism’s Second Album were full-blooded works that confirmed the talent of their creative teams and their promising futures.

Casus, Finding the Silence, performer-creators Emma Serjeant, Jesse Scott, Lachlan McAuley, Vincent Van Berkel, director Jesse Scott, sound design Dan Carberry, lighting Rob Scott, Judith Wright Centre for Contemporary Arts, 15-23 Aug; La Boite Indie, Hedonism’s Second Album, writers David Burton, Claire Christian, director Margi Brown Ash, performers Patrick Dwyer, Gavin Edwards, Nicholas Gell, Thomas Hutchins, Ngoc Phan, designer Josh McIntosh, lighting Ben Hunt, La Boite, Brisbane, 13-30 Aug

RealTime issue #123 Oct-Nov 2014 pg. 35

© Kathryn Kelly; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

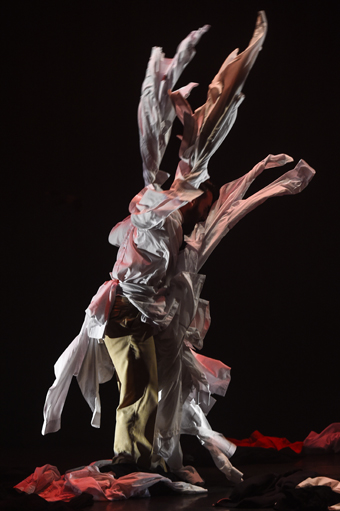

Jade Dewi Tyas Tunggal, Mantle, My Darling Patricia

photo Heidrun Löhr

Jade Dewi Tyas Tunggal, Mantle, My Darling Patricia

“What am I for?” asks the voice that has been speaking since we were first planted into a sustained, unsparing darkness. This voice has transported us from suburban mayhem—a few too many sherries in the car before forgotten veggies bake to burning, a glimmer of someone sick and dying, eyebrows plucked to vanishing—to the edges of an ominous hole in the road and down into its abyss.

The voice that we hear while we do not see paints us into a stock Australian domesticity. The ‘she’ who speaks in both third and first person is at once inside and outside of her own scene-making. She sounds dry and a bit ocker, as if she is, in part, the voice of nostalgia or even gendered myth itself.

Since the early 1990s when Jenny Kemp first dressed the Australian stage in what has since been called an externalised dynamics of the female psyche, the national theatre has wrestled with the knottedness of female experiences and narratives, myths about them and the limits and possibilities of an increasingly experimental non-narrative stage. In Kemp’s works, it was writing for and at the edge of performance that seemed to land a form that was both implicitly national and explicitly ‘female,’ offering a transformative spatial rendering of those post-structural fractured subjectivities whose ghosts we now know a little too well.

In Mantle, My Darling Patricia reveal a debt to this lineage but also aim to cast their own poetics into the readily twinned spaces of psyche and theatre. We never learn the name of our narrator, but her figure arrives in the shape-shifting movement episodes that visualise the plight of a woman who has been plunged to the centre of the Earth (Jade Dewi Tyas Tunggal). On the edge of visibility, her body writhes and twists, twitches gently, throbs and curves to varyingly thudding, sensuous and pulsating sound. In less effective scenes she is clambering against the scrim, acting out entrapment. In others, she seems seductively caught in the sort of ecstasy that might just come with freefalling grief.

If the figure’s movements shift undecidedly between the literal and the abstract, the speaking voice also jumps too neatly between a fictive elsewhere and the metaphor that renders it. Her story, we come to learn, is less about being enclosed in earth than it is about the kind of descent that occurs when the self is cut to its core by despair. As she appears and disappears, the stage invisibly moves around her—its objects also somewhat undecided, hovering ambiguously between symbol and substance. A large fluorescent ice beam appears out of nowhere, and then vanishes. A large black sphere casts a tall shadow of a hole, and then is gone. A cone enshrouds the woman’s body which by then is reaching tremulously towards a surface.

The components, individually, are interesting imaginings: text (Halcyon Macleod) is rhythmic; design (Clare Britton) is stark and vibrant. Both are often outdone by sound (Jack Prest) that radiates in and out of recognisability with moments of lonely jazz, a distorted car horn, a penetratingly dirty electric guitar. And yet, in moving us between the twin realms of this story—inside and out, fictive dream and fictive real—the artists contain us in a kind of pretense that, despite experiments in visual form, feels somewhat narratively closed. Jenny Kemp opened out the stage by playing with non-linear text and its relationship to an abstract and painterly mise-en-scéne. Twenty years later, Mantle doesn’t quite find a meta-theatrical language to sequel Kemp: the kind that could make those of us sitting in the dark alive to our own psychic imaginings, seeing and feeling the theatres in our minds.

My Darling Patricia, Mantle, co-creator, writer, narrator Halcyon Macleod, co-creator and images Clare Britton, lighting Matt Marshall, composition, sound design Jack Prest, performer, choreographer Jade Dewi Tyas Tunggal, dramaturg, script editor Janice Muller; Campbelltown Arts Centre, 11-13 Sept

RealTime issue #123 Oct-Nov 2014 pg. 36

© Bryoni Trezise; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Escape Room Melbourne.

courtesy the artists

Escape Room Melbourne.

You’re in a bungalow at the back of a garden in suburban Melbourne. The game runner, who met you at the door and explained the experience you were about to have, locks the door behind you and the room is dim. You have torches and an hour to work out how to get out.

Escape Rooms are a new form of interactive entertainment in which participants are locked inside a room and must complete a series of puzzles and challenges in order to escape. Inspired by the digital Escape the Room games designed in 2005 by Toshimitsu Takagi, such as Crimson Room, real life versions of the game began to appear around 2007 including Takao Kato’s room in Japan and Kazuya Iwata’s room in the USA.

Escape Room Melbourne, run by Dr Ali Cheetham and Dr Owen Spear, was the first to open in Australia and since then new rooms have opened in Sydney, Perth and a second in Melbourne. Cheetham and Spear first encountered Escape Rooms in Budapest, where the form is so popular that over a hundred rooms have opened. Spear recalls, “Some of the rooms had an interesting, old nostalgic feel; others would be a little bit creepy and run down. It felt to me like being a kid again, exploring a room, trying to find a hidden object.”

Each Escape Room tends to be unique, expressing itself through the aesthetic choices of the designer, the kinds of challenges and the depth of narrative. The active puzzle-solving and teamwork elements can lend themselves to less nuanced purposing of the experience, of course, and there are many versions that lean heavily on genre—there’s no shortage of zombies and safe crackers in these rooms, be assured. The experience can also be lyrical, suspenseful and magical.

Escape Room Melbourne, for two-four people in a 70-minute session in a medium size room, has a quality of haunted suburban mystery to it. There is a sense that something urgent once occurred in this room. A letter gives the room its fictional context, laying out just enough exposition to give a narrative explanation for your presence in the room. Each puzzle and challenge has antiquity: the furniture, the objects, the clues, all come from a Melbourne long past. It’s a little like discovering that your grandparents were Cold War spies.

In this way the environment is made to perform around you. The sense of significance gradually focuses the longer you play. As you work out how the puzzles have been constructed around you, a grid of narrative meaning is layered over your physical experience. At the end it’s possible to trace your own experience through the room by following the path of solved puzzles.

Spear describes the participant experience of their Escape Room, saying “most people start off a little uneasy, and then really get into it once they’re in. There’s huge variety in the way people interact with the room. No team seems the same, and they range from speaking very little, and acting quite seriously, to screaming and laughing.”

A crucial aspect of Escape Room is the feedback mechanism that helps players move through the tasks. This varies from live in-character performances to no feedback at all. In the case of Escape Room Melbourne it’s a simple voice over. The Game Runner who let you into the room is also monitoring your progress as you play. If you need a clue you can ask for one. If the runner sees that you are very off-track or running out of time they will sometimes offer advice. Spear says, “I think they interrupt it slightly, but it’s sort of a necessity, otherwise the puzzles would have to be made too easy. We’re thinking of having a note system set up in the next one, where hints are sitting round the room in envelopes.”

Players are able to listen to the prompts in an ‘out of game’ framework which keeps the mechanics of the game very apparent without impacting on the immersive nature of the experience and lends it a sense of security. Other escape rooms are much more immersive, designing all their interactions as ‘In Game,’ which heightens the potential for immersion but demands more commitment to performing over playing.

Escape Rooms are part of the growing trend towards immersive and participatory experiences that includes work as diverse as that of Blast Theory, Punchdrunk, Slingshot and Coney (see my articles in RT115, and RT117). As Frank Lantz, director of the NYU Games Center, told CNBC, “Games used to be a form of experience. The thing that got left out of that equation was human bodies and face-to-face interaction. I think we’re seeing a return to those qualities.”

Escape Room Melbourne, book online: www.escaperoom.com.au

RealTime issue #123 Oct-Nov 2014 pg. 36

© Robert Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Use Your Illusion, Bron Batten

photo Bryony Jackson

Use Your Illusion, Bron Batten

Co-Curator of Melbourne’s eclectic Last Tuesday Society, Bron Batten, invited audiences into the dingily appropriate Collingwood Masonic Lodge in late August for her esoteric exploration of the art of hypnosis, Use Your Illusion. Supplied with voyeuristic pleasures, audience participation, cheese cubes and sliced kabana, spectators were drawn into a world of swinging pendulums and optical illusions; and equally, seduced by the mesmeric art of performance itself.

The venue’s somewhat clandestine side entry promises its own mysteries; entering the dimly-lit hall, three raised stages are apparent, the audience placed between them. We’re seated at large round tables dotted with tea-light candles and provisioned with the aforementioned snacks. A portrait of the young Queen Elizabeth II, muted to sepia over decades and too high for dusting, presides watchfully from the Lodge’s rear wall. On a side stage, Batten appears in a chicken suit, bathed in the light of a swirling, hypnotic spiral.

In a perhaps trance-inducing tone over spooky, meditative music, Batten gently, firmly and repeatedly issues her instructions: “You are going to enjoy the show immensely;” “Breathe deeply…let it all go;” “You will love me, you will love my show.” Her work done, the chicken exits. Next, there’s projected video of Batten on a couch, sobbing inconsolably, with a male (therapist’s?) voice crooning, “Take your time, Bron. We can wait till you’re ready.” But before we can become confused, it’s show time: pumping music, smoke and dancing laser-light draw us to the main stage where a now lamé-clad Batten reappears to introduce us to our ‘host’: professional hypnotist Charles Mercier.

Use Your Illusion, Charles Mercier

photo Bryony Jackson

Use Your Illusion, Charles Mercier

The ensuing lengthy (and very funny) demonstration of auto-suggestive techniques—which Mercier tells us are really just permission to release one’s inhibitions—uncovers rich territories of voyeurism and vulnerability, blurring the real and unreal. Mercier delivers his explanations like a serious professional while gesturing like a cheesy showman. After bringing 10 audience volunteers onstage alongside Batten, he hypnotises his subjects, inducing them to perform simple scenarios. They respond in varying degrees to requests to ‘walk down stairs,’ ‘be in a tropical resort,’ ‘walk the catwalk’ and so on. In watching, we, of course, are mesmerised too, enslaved to a fascination that’s tinged with the discomfort of our own laughter, as we watch people just like us doing slightly embarrassing things for our amusement.

It’s all rather silly—some of the volunteers themselves slip out of ‘trance’ to giggle as Mercier ups the ante with increasingly awkward requests. Gradually the ‘least receptive’ volunteers are culled, and those remaining ‘perform’ each new action in a state that may or may not be actual, but is riveting to watch because it is so free. Mercier uses his showman’s commentary to implant deeper ideas: at one point he describes these uninhibited behaviours in terms of the power and love that we all have in our bodies. I forget myself completely in the pleasure of watching a middle-aged ‘hypnotee’ dance for us, radiant and projecting joy like a woman in love. It’s magical, and a privilege to watch, regardless of what has unlocked her freedom.

Finally, only Batten is left on the stage. Mercier presents a final challenge, inducing her to perform a particularly physically uncomfortable task. Watching, the audience becomes complicit in a vulnerability that none of us moves to prevent, exposing the flipside of the ‘hypnosis’ created by the stage/audience divide.

The rest of Use Your Illusion leaps from the heartfelt to the wacky to the arcane to the self-helpy, without ever allowing the audience the safety of knowing what’s truth and what’s playful deception. There are self-critical confessions and positive affirmations, another chicken in a suit and a further scene of hypnosis that leaves far behind the showman’s piercing eyes and flashy tux.

Throughout the show, and around the long, central ‘demonstration,’ Bron Batten manages to juggle disparate scenes and styles, held together by our collective attention. Cohesion seems secondary to exploration: the ‘devised’ nature of the work is writ large, and ideas float free with all the plurality and contradiction of the things in life that are just a bit mysterious. One minute the feeling is ‘Be who you are!’ and the next, I know we’ve been duped. And in the next, I find myself reflecting on performing and watching: on who we are, who we think we are, how we ‘perform ourselves’ and who we might be if we really just relaxed.

And then I also think: what if that chicken at the start actually DID hypnotise us into loving the show? How would we know?

Bron Batten, Use Your Illusion, performers/devisers Bron Batten, Charles Purcell, Ben Liston, Beth Sometimes, composer Edward Gould; Collingwood Masonic Lodge, Melbourne, 21–24 Aug

RealTime issue #123 Oct-Nov 2014 pg. 37

© Urszula Dawkins; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Cowra no Honcho Kaigi/Honchos Meeting in Cowra

photo Michihiro Furumoto

Cowra no Honcho Kaigi/Honchos Meeting in Cowra

Written and directed by prominent Japanese playwright Yoji Sakate, Honchos Meeting in Cowra sits within a post-WWII ‘small theatre’ tradition influenced by Chekhov and Ibsen as much as by Japanese Noh and Kyogen. The subject of this play is the Cowra breakout of August 1944 when 1,104 Japanese POWs escaped, 231 of whom were killed in the subsequent recapture, along with four Australians. The play’s focus is the redemption of identity and ‘face’ (or omote) by Japanese soldiers shamed by being captured. Hoping to be shot, the escapees possibly sought the means to die honourably by fighting or effectively committing suicide.

The play also looks to the contemporary context where the public in Japan remain misinformed of the effects of the recent Fukushima accident, unable to face the realities of that disaster.

The set represents a hut in the Cowra camp, replicating flimsy, fibro-thin walls (a pitched pine frame, joists exposed) with props such as tatami mats, toothbrushes, cups and forks and the bucket in which illicit sake is brewing. The details are significant, as we come to learn that this is actually a film set, part of an exercise where two contemporary, young Australian film students and their mentors from Australian and Japanese film schools are undertaking an ‘exercise’ to test their hypotheses as to why the POWS took the actions they did.

There are significant cross-cultural tensions, questions of honour and identity, the collective versus the individual, under investigation here. It is not just the POWs who suffer the effects of capture but also their relatives in Japan, who’d be subjected to extreme humiliation if it were known the men were captive. In many ways, this play is an attempt to understand, subvert and overwhelm that imperative. The final scene sees the young Australians urge the POWs to choose a different path from heading into suicide.

In this version of the story, the filmmakers being Australian smacks of Western imperialism, the superior, individualist, outsider view. The Tokyo original had these roles played by 15 young Japanese, which instead makes the questioning an inter-generational provocation. But within both conventions, the capacity to call ‘cut’ and have the final scene achieve a different outcome highlights the human capacity to create and remake different worlds.

Cowra no Honcho Kaigi/Honchos Meeting in Cowra

photo Michihiro Furumoto

Cowra no Honcho Kaigi/Honchos Meeting in Cowra

The strongest part of the play, however—in both imaginings—is surely when the POWs indulge the students’ wishful thinking but suddenly enact their own ‘cut’ and return to ‘what really happened.’ The men’s sense of shame cannot realistically be changed. So the play’s form is both linear and spiral, winding into the vortex, out into a world of different possibilities and then back in again.

The play passes from rather clunky didactic scenes, which serve to fill in historical detail, to disciplined comedic routines which borrow from their condensed, sharply-realised characterisations rooted in Kyogen (the lads in the barn, passing time), and then to intensely moving final scenes which combine both the refined stillness of Noh drama with the psychological depth of character and soul-searching we associate more with Western theatre, such as when the former group leader Murata, converses with the film producer, thinking she is his ghost. He is unsure who he has become, being incarcerated for so long. The part is beautifully played by Takahiro Onishi, his conscience stirred like turbulence deep within a lake.

Similarly, the ballot scene, where each POW is clearly expected to cast the vote to die rather than choose to live, is finely realised, each approaching the ballot box with an enormous sense of dignity and conscience. One man casts a vote to live. The one who seemed weakest in resolve but votes to die shows the full weight of a society unable to reveal what it feels resting on his shoulders. He is horrified. There is, perhaps, no one to blame. His fabric—the fabric of them all—has been frayed.

The set is lofty rather than claustrophobic, and the lighting its weakest element, too stark to be the dream it seems for re-thinking an historical event. Then again, its sharpness keeps the play from becoming an enactment of ‘forgiving the past, which I think it is not. The physicalisation of the Australian actors (building on a previous exchange between Sakate and NIDA in 2004) emulates the discipline of the Japanese actors but is odd in comparison: not that the Australian cast is weaker, rather their presence does not emerge out of a centuries old, deep-rooted practice where words and hieratic movement have evolved together. The slapstick in earlier scenes is particularly odd, not quite matching the sense of chiselled caricature of the POWs (although Matthew Crosby comes close in his various characterisations).

The intoning of both Japanese and English texts is almost identical from one performance to another, as in a musical score. Perhaps the characters are indeed dreaming each other. In Cowra—perhaps too in Japan—nothing in fact remains of these men apart from their headstones marked with false names. Members of the public—several from Cowra, whom I met both in the Canberra and Sydney showings—seemed deeply touched by a production that reveals hidden worlds in both sides of the experience.

Cowra no Honcho Kaigi/Honchos Meeting in Cowra, writer, director Yoji Sakatem, design Jiro Shima, lighting Isao Takebayashi, sound Takeshi Shima, costume Nobumo Miyamoto, choreography Mikuni Yanaihara; Cowra Civic Centre, Street Theatre, Canberra, NIDA Parade Theatres, Sydney, 1-10 Aug

RealTime issue #123 Oct-Nov 2014 pg. 38

© Zsuzsanna Soboslay; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Hamish Michael, Justine Clarke, Jacqueline Mackenzie, Toby Truslove, Chris Ryan, Children of the Sun, Sydney Theatre Company

photo Brett Boardman

Hamish Michael, Justine Clarke, Jacqueline Mackenzie, Toby Truslove, Chris Ryan, Children of the Sun, Sydney Theatre Company

In a short period, Sydney Chamber Opera has presented Mayakovsky (p42) and Sydney Theatre Company Maxim Gorky’s Children of the Sun (1905). A generation older than the poet Mayakovsky, Gorky was at various times harassed and gaoled (he wrote Children of the Sun in prison) for fomenting revolution with his plays. Both poet and playwright became key cultural figures in the Russian Revolution and both were dispirited by Stalinism. Mayakovsky suicided in 1929, Gorky died in 1935 of natural causes at the time Stalin’s Terror was escalating.

Gorky’s playwriting is commonly considered structurally ungainly but rich in social observation and deft characterisations. Belvoir’s 2011 production The Business (RT104, p 18), an updated adaptation by Jonathan Gavin of Gorky’s grimly comic Vassa Zheleznova (1911)—a favourite of Stalin who saw it many times, presumably enjoying the agonies of a bourgeois family in their act of self-destruction (and the enforced changes to the play in 1935 to suit his tastes)—retained the playwright’s essential virtues, not least his strong focus on women. Coming into his stage career in the wake of his friend Anton Chekhov was certainly not an advantage and he was lambasted by left and right for lacking subtlety or political solutions. Subsequently the blend of humour and high drama in his best plays has been recognised indeed as Chekhovian but with political intent and a voice all its own.

Andrew Upton’s adaptation (originally for the Royal National Theatre, London production 2013) and Kip Williams’ direction of Children of the Sun realise the comedy-drama dynamic right to the play’s bitter end, our emotions and allegiances tossed about and our sense of the inevitability of revolution—with a self-preoccupied intelligentsia indifferent to a superstitious and violent peasantry—confirmed. While adhering in good part to Gorky’s dialogue, texturing it lightly with contemporary touches and the odd four letter word (these alarmed the British but are deftly integrated), Upton has very cleverly re-shaped the play. A few minor characters are deleted or merged, providing a tighter sense of community and, more significantly, key exchanges (like the estate owner and chemical scientist Protasov’s admonition of the worker Yegor for beating his wife) are held off in order to more effectively delineate character and control plot momentum.

The largest change, and the most effective, comes in the play’s fourth act, partly making the climax sparer but also re-ordering it and adding a final image, quietly inherent in the original but here writ large—the physical and emotional collapse of Protasov, unable to comprehend the fact and extent of his losses, his property burned by rioters who think he has poisoned them to procure business for the local doctors (whom they execute) and of his wife, the spirited Yelena who yearns for an artist’s life and will leave him. The riot is offstage which means we don’t get to see her shoot a peasant (this scene had a frightened audience scrambling for the exits in the volatile climate of 1906) after trying her best to help the locals manage what is in fact a cholera outbreak. Gun in hand, she heads off with everyone else to do battle while Protasov lingers helplessly, curling into himself, the epitome of the landowning class-cum-intelligentsia blind to its failings. It’s a powerful ending, and certainly an improvement.

The production is mounted on a large revolve on which the house is segmented, so that when rotated we see large rooms and small private spaces but also the construction behind, adding an appropriate sense of fragility as well as an excellent depth of field for witnessing comings and goings and frequent wanted and unwanted encounters. As in Chekhov, entrances and exits in the production are very telling, and here often funny.

Humour is everywhere from the very beginning, with a buzzing, argumentative household, bossy servants, Protasov and Yelena uselessly insisting on quiet. Protasov’s admirer, the wealthy widow Melaniya, courts him disastrously—climaxing in a humiliating egg-throwing scene and a subsequent confession to Yelena. The pompous artist Vageen (who hilariously wields the act of portrait drawing like a weapon) courts Yelena who is in turn grateful for the friendship while he assumes she loves him. Yelena’s frustration deepens, but her dilemma is nowhere as deep as her sister’s. Lisa is a fragile Cassandra. Her gory visions of mob violence, inspired by newspapers and rumour, are more prophetic than paranoid. Everyone cares for her, if not really listening, including the bitterly cynical Boris, the estranged brother of Melaniya who realises to his astonishment that he is in love with her. Lisa’s own like-minded realisation comes too late with tragic consequences. This dark strand is tautly woven with the comic stand-offs, everyday crises (a maid resigns) and revelations (a marriage has run its course).

Kip Williams’ direction is precise, fluent and finely graded, his ensemble performing as one. Toby Truslove’s wonderfully realised Protasov is self-centred, easily distracted and unconsciously funny, his arrogance disguised by his apparent affability and the ease with which he avoids or moves on from clashes—a state of denial which will deal him a pathetic end. Justine Clarke judiciously delineates Yelena’s growing sense of herself, one of the family but moving beyond it. Helen Thomson’s Melaniya is hilariously naïve and subsequently sadly wise, another fine transformation. Jacqueline Mackenzie’s portrayal of Lisa is richly detailed—ailing, analytical but volatile, trapped and tragic, but then resolute. Chris Ryan, Valerie Bader, Hamish Michael, Yuri Govich, Jay Laga’aia and Contessa Treffone all bring subtleties and insights to their roles.

What is truly bracing about Children of the Sun, is that in an era of deracinated adaptations, Gorky’s breadth of vision has been sustained—with all the complexities of class, work, ideas, progress and ignorance and their stressful interplay. The play calls to mind our challenged intelligentsia (as neoliberalism sucks the air out of thought), women still fighting for equality and the widespread validation of ignorance—it’s not peasant ignorance about science that hinders us today, incredibly it’s wealthy, educated climate change denialists and parents refusing their children inoculation thereby putting others as risk. I left Children of the Sun in equal parts exhilarated—by the wit and wisdom of the play and its production—and depressed, mindful of the huge gap opening up between rich and poor in the West to which so many are blind.

Sydney Theatre Company, Children of the Sun, writer Maxim Gorky, adaptation Andrew Upton, director Kip Williams, designer David Fleischer, costumes Renee Mulder, lighting Damien Cooper, composer, sound design Max Lyandvert; Drama Theatre, Sydney Opera House, 12 Sept-25 Oct

RealTime issue #123 Oct-Nov 2014 pg. 40

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Miranda Wheen, Matt Cornell, Between Two & Zero

courtesy FORM Dance Projects

Miranda Wheen, Matt Cornell, Between Two & Zero

Miranda Wheen’s first work in this FORM triple bill, Safe Hands, is a short, cartoonish satirical take on demagoguery in which the initially suited dancer plays male-politician-as-celebrity—mutating from the crowd stirrer to a man-of-the-people mover (with excruciatingly protracted dancing and twitching to ironically selected rock and pop numbers) and, finally, the sportsman, pushing himself towards limits visibly beyond his reach but nonetheless wrapping (actually masking) himself victoriously in Australian icons (to “We don’t need another hero”).

It’s broadbrush commentary, but a reminder of how Tony Abbott (the suit, the blue tie; the hard hat, the safety vest; the army apparel; the bike, the water and any other challenge) has followed in the footsteps of John Howard (whose guises included the ‘RM Williams’ man on the land). The most striking image in this work has Wheen on all-fours convulsively dropping torso and abdomen floorward (to Janis Joplin’s “Cry Baby”), suggesting a masochistic dimension to the narcissistic power figure.

A more impressive work, Between Two and Zero, created in collaboration with co-performer Matt Cornell, is also an exercise in testing limits, this time in an initially delicate but soon assertively physical courtship. Informal party dancing is followed by cautious, almost courtly tracking of each other, her sudden, funny headfirst dash into him (desire as violence?) and a repeated series of tightly intimate face-to-face lifts which appear tortuously close to separating head from neck. This obsessive ritual is hauntingly realised in the dancers’ acuity of movement, physical strength and the dreamlike lighting transitions (Guy Harding) that increasingly close in the space around the pair. Wheen and Cornell reveal substantial choreographic potential, transforming an everyday universal into a very specific vision of the tangle that is coupling.

Sketch, Carl Sciberras (video still)

Carl Sciberras’ Sketch is an adventurous meeting of dance and digital artistry, bringing together a trio of dancers, composer Mitchell Mollison and visual artist Todd Fuller (both onstage), in which the latter alternately leads the dancers with his overhead-projected live sketches of body shapes into which they step, or accompanies them with richly coloured iPad finger swipes of increasing density, daring and complexity. The music is likewise responsive, crisply realised, nicely textured and more than a little evocative of the electronic music I grew up with in the 1960s—hard edged, metallic, static washes, shifting wavelengths and, finally in Sketch, great oceanic waves of sound.

There are several problems with Sketch. First, it is hugely overwrought: the not very interesting matching of sketched bodies and dancers and the much more fascinating digital brush-stroking of screen and the colouring-in of dancers are both far too long. Many good ideas are simply wasted. Second, the choreography, although adroitly and confidently realised, never breaks free of its formality, resulting in an unresolved dialectic between the dancing on the one hand and the freedom of expression of the sound and image collaborators on the other, especially the visual artist whose display of inventiveness appears limitless, eventually upstaging any attempt at dialogue or break-through synthesis. I treasured the few moments when the dancers appeared to take control of the imagery. Sketch is the potential from which a more succinctly powerful work might evolve.

FORM, Dance Bites 2014: Dance Makers’ Collective, Triple Bill: Safe Hands, choreographer, performer Miranda Wheen; Between Two & Zero, choreographers, performers Matt Cornell, Miranda Wheen; Sketch, choreographer Carl Sciberras, visual artist Todd Fuller, live composition Mitchell Mollison, performers Katina Olsen, Carl Sciberras, Rosslyn Wythes; Lennox Theatre, Riverside Parramatta, 11-13 Sept; http://form.org.au

RealTime issue #123 Oct-Nov 2014 pg. 28

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Early Warning System, Give us this Day—Five Sonic Adventures

photo Greg Harm

Early Warning System, Give us this Day—Five Sonic Adventures

Increased exposure to Indian, African and Asian music has made the last 100 years or so pretty good for Euro-Western percussion lovers. Enter Early Warning System with a beautifully programmed selection of recent works—by Erik Griswold, Vanessa Tomlinson, Kate Neal, Anthony Pateras and Michael Askill—that reflect the influence of that exposure on the Western classical tradition.

First up is the premiere of Erik Griswold’s Give us this day. The piece begins stately and processional (more Java than Bali) then moves through sections of quite different sonorities as is common with Griswold’s work. Not all percussive, at one stage Griswold’s much loved melodicas are introduced along with bowed cymbals to develop a beautiful tonespace of slowly overlapping chords. With the percussion the playing is sometimes soft and gentle, allowing the sound of touching skins with hand or beater to dominate the resonant boom of the drum, giving a percussion that is as much about touching and manipulating a surface as it is about dividing time into predictable chunks. Give us this day is very much a work that refines earlier concerns and demonstrates the continuing maturation of Griswold’s distinctive voice.